The Chinese language is based on ideographs. Each one has a single-syllable sound, but words may be combined for complex subjects. For example, the word for computer is the compound: “electric-brain-machine.” Thus, a term that may seem to be multisyllabic is always a combination of single words. The name Laozi, for example, is a combination of the words “old” and “master.” Naturally, language has evolved over thousands of years, many meanings have been added, and translation is complex.

Since the Chinese language is not alphabetic, different systems to approximate its sounds in English were established. The task was not easy. First, there are sounds in Chinese that no English sounds can duplicate. Secondly, and confusingly, there can be five different tones to any given Chinese sound, with each tone signaling a completely unrelated meaning. While there are about four thousand syllables in English, there are only about forty in Chinese, so each basic sound must have its five different tones (flat, rising, falling, falling-rising, and neutral) to gain a large enough number of words. A sound like ma, for example, can mean “mother,” “hemp,” “horse,” “scold,” or it can be a question-particle—all depending on the tone.

One prominent method of transliteration, established about 1867, was the Wade-Giles system, and that is where Tao spelled with a “T” originates. In 1958, the People’s Republic of China adopted a new method of romanization, known as pinyin, that became the prevailing system throughout the world. Pinyin utilizes diacritics to indicate tones for language learning and pronunciation, although these diacritics are seldom employed in publications and scholarly works. The majority of the Chinese words in this book are romanized according to pinyin.

Exceptions to Pinyin Romanization There are some exceptions to pinyin in this book when a word has entered the English language under an earlier spelling. Tao, Taoist, and Taoism are the major examples. In pinyin, Tao is properly spelled Dao (which is a better indication of its pronunciation—a hard “D” sound rather than a hard “T” sound). However, especially in search engines and popular references, “Tao” has far more recognition than “Dao.” Examples of other words left in non-pinyin spelling are I Ching (Yijing), Confucius (Kong Fuzi), and Buddha (Budai).

How to Read Chinese Names Chinese names are written with the family name first. For example, Zhang Lang is from the Zhang family and his personal name is Lang. When someone has a two-word personal name, the personal name is made into a two-syllable word. For example, Zhao Gongming comes from the Zhao family and his personal name is Gong combined with Ming. A few people have compound family names, such as Sima Qian and Zhuge Liang.

Many of the gods mentioned in this book have descriptive titles. Taishan Laojun means the Great Supreme Old Lord. In these cases, the translation of the title is used with the pinyin in parentheses.

Many sources have been utilized in writing this book, but most of the references come from the core texts of Taoism, Confucianism, and Buddhism. Their titles and alternate names can be confusing, so a brief overview of naming conventions and the names of the key texts will be helpful. All translations are original.

Naming Conventions

In order to standardize the translations of book titles, the designation jing is translated as “classic.” For example, the Shijing is translated as Classic of History. The word jing means a classic, a sacred book, scripture, or canon. Any book that has the appellation jing is highly revered.

A ji is a record. Examples are the Record of Rites (Liji) and the Records of the Grand Historian (Shiji).

Some books are named after their author; one might refer to an author’s name and then refer to the book title by the same name in the same paragraph. For example, Zhuangzi is both the name of the author as well as the title of the Zhuangzi.

In most cases, the title is given in its English equivalent, but there are three notable exceptions. The Daodejing and the I Ching are given by their Chinese titles, since they are widely known by those names. The Zhuangzi is also left as it is, in part because it is familiar by that name, and in part because it means no more than “Master Zhuang” and there would be nothing illuminating about referring to it in English.

Daodejing and Zhuangzi

The majority of Taoist quotations are drawn from the Daodejing and the Zhuangzi.

Daodejing The Daodejing (The Classic of the Way and Virtue; also spelled Tao Te Ching) is Taoism’s premier holy book. The authorship of the book is constantly debated in scholarly circles, but tradition holds that an ancient sage named Laozi wrote this book in the sixth century BCE.

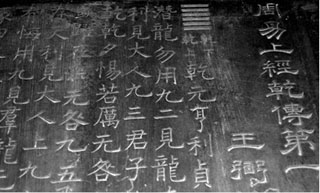

The Daodejing inscribed on a wall on Zhongnanshan.

© Photo by Peter Pynchon

The text is central to philosophical Taoism and it has strongly influenced other schools such as Legalism and Neo-Confucianism. Religious Taoists chant the text as a devotional act and they worship Laozi as the Great Supreme Old Lord. Chinese Buddhism has also utilized the book, taking its terms to translate Buddhist texts brought from India. In addition, many commentators have asserted that Chan Buddhism, which is known as Zen in Japan and the West, represents a melding of Buddhism and Taoism.

The traditional text consists of eighty-one short and poetic chapters in language so variable in meaning that many simultaneous understandings are both possible and valid. The Daodejing is one of the most frequently translated of Chinese spiritual books.

Zhuangzi The book, dated to the fourth century BCE, has also been known as the Nanhua Zhenjing (The True Classic of Nanhua), because it’s believed that Zhuangzi came from southern China (nan means south). As is the case with the Daodejing, scholars dispute the idea that a single person wrote the entire book. The academic view is that Zhuangzi wrote the first seven chapters, called the Inner Chapters, and that others wrote the Outer Chapters. In traditional contexts, however, all parts of the Zhuangzi are considered important.

Where the Daodejing is terse, brief, and poetic, the Zhuangzi is largely prose, utilizing essays and fables to make its points. Zhuangzi satirizes the arguments of other philosophers with exaggerated logic that leads to absurd conclusions, and imagines dialogues between Laozi and Confucius, or between Confucius and his students. Sometimes he uses Confucius as an exemplar of wisdom, and at other times, he shows Confucius rebuked by others. He also makes use of dreams, dialogues with skulls or trees, and shows the native wisdom of fishermen or butchers to be superior to sages. Zhuangzi is the skeptical, absurdist, argumentative, and humorous counterpoint to Laozi’s mysticism.

Confucian Texts

Analects (Lunyu) A compilation of speeches and record of discussions between Confucius and his disciples. Most of the text was written by Confucius’s students thirty to fifty years after his death. The date of publication is estimated around 500 BCE.

Mengzi (Mencius) A collection of conversations between Mencius and the kings of feudal states regarding the proper philosophy of ruling.

Additional material is drawn from the canonical texts of Confucianism known as the Five Classics (Wujing). All were supposed to have been in some way compiled, edited, or commented on by Confucius himself.

Classic of Poetry (Shijing) A collection of 305 poems consisting of 160 folk songs, 105 court ceremonial songs, and 40 hymns or eulogies used in sacrifices to gods or the royal family’s ancestral spirits. The poems date from the tenth to seventh centuries BCE.

Classic of History (Shujing) Also known as the Classic of Documents (Shangshu), the book is a compilation of documents and speeches written by the rulers and officials of the Zhou dynasty. The majority of the texts are thought to have originated in the sixth century BCE.

Record of Rites (Liji) Rites are a central component of Confucianism. They are rules governing rituals; court ceremonies; and social conduct around filial piety, ancestor worship, and funerals. The original work was reputedly edited by Confucius, but the present version is probably from about the third century BCE.

I Ching (Classic of Changes) The proper transliteration of this book’s title is Yijing, but the book is better known under this older spelling. It is a book that can be used on many different levels. Based on sixty-four hexagrams—graphs consisting of six lines—the I Ching is a deep study of change. The core texts go back to at least the twelfth century BCE, and it has been studied as a book of divination, strategy, and philosophy ever since. Its core thesis is that all is constant change propelled from within by yin and yang.

Spring and Autumn Annals (Chunqiu) Also known as the Linjing, the book is a historical record of the state of Lu, Confucius’s native feudal state. Diplomatic relations, alliances, military actions, the affairs of the ruling family, as well as natural disasters from 772–481 BCE are chronicled for both their historical and moral significance.

These are the first lines of the I Ching, incised into one of the Kaicheng Stone Classics (Kaicheng Shi Jing). The 114 massive rock slabs preserved at the Forest of Stone Steles Museum in Xi’an contain twelve Confucian classics including the Classic of History, the Classic of Poetry, and the Analects. The monumental “books” were carved by order of the Tang Emperor Wenzong (809–840) in 833–837 as an indisputable reference work for scholars.

Poetry

The primary source for most of the poems quoted in this book is Three Hundred Tang Poems (Tangshi Sanbai Shou), an anthology of poems from the Tang dynasty (618–907), first compiled around 1763 by Sun Zhu (1722–1778). There are actually over three hundred poems, perhaps emulating the 305 poems in the Classic of Poetry. Many people consider the Tang dynasty the time of China’s greatest poets, with Li Bai, Du Fu, Wang Wei, Li Shangyin, Bai Juyi, Han Yu, and Meng Haoran among the most notable.

Records of the Grand Historian

The Records of the Grand Historian (Shiji) was written by Sima Qian (c. 145–90 BCE,), who is considered China’s foremost ancient historian. His history covers some two thousand years from 2600–91 BCE. While modern historians may debate some of the details of the text, Sima Qian had the advantage of being closer in time to the events he was writing about.

Chan Buddhist Texts

A number of Chan (Zen) Buddhist koans (gong’an) are referenced in this book. All of them are drawn from two sources, the Wumenguan and the Blue Cliff Records.

Wumenguan (The Gateless Gate) As is the case with the Zhuangzi, the book is named after its writer, the Chan Buddhist master Wumen Huikai (1183–1260). Each koan recounts a dialogue or situation that reveals an understanding of Chan Buddhism. Wumen wrote a commentary and verse to each one of forty-eight cases. The name Wumenguan itself is ambiguous and lends itself to multiple interpretations. It can be translated as the Gateless Gate, the Checkpoint With No Entrance, the Pass With No Door, and many other possibilities.

Blue Cliff Records (Biyan Lu) A collection of Chan Buddhist koans first compiled in 1125 by the Chan master Yuanwu Keqin (1063–1135), which he later revised and expanded.

The Twenty-Four Solar Terms

The woodcut illustrations and basic text of the exercises to the Twenty-Four Solar Terms are taken from The Beverages of the Chinese, by John Dudgeon, The Tientsin Press, 1895. Dudgeon (1837–1901) spent nearly forty years in China as a doctor, surgeon, translator, and medical missionary. According to editor William R. Berk, the exercises were taken from Zunshen Ba Jian, written by Gaolian Shenfu in 1591. Other sources name the exercises’ creator as Chen Tuan, also known as Chen Xiyi (871–989), a legendary Taoist sage associated with the western sacred mountain, Huashan.

These movements are a subsection of qigong classified as daoyin—movements to lead energy. The instructions are modified according to contemporary training.

What is the most basic knowledge we have about Laozi and Zhuangzi, the two most influential writers in Taoism? We have two books, the Daodejing and the Zhuangzi, and we know that both are highly regarded works of spirituality and singular wisdom. In the case of Laozi, he was deified, revered by every sect of Taoism, and given attributes that reflect the concerns of the worshippers: the religious consider him one of Taoism’s highest gods, the alchemists portray him as a maker of the elixir of immortality, and the philosophical consider him the source of Taoism’s naturalistic and visionary philosophy. In contrast, Zhuangzi was not deified, and any mythologizing of his personality came from his own stories. Depicting Zhuangzi asleep and in the act of the Butterfly Dream has become a motif in itself, and phrases from the Zhuangzi have entered the culture in the form of proverbs, idioms, fiction, opera, and comic books.

It is impossible to say with certainty who Laozi and Zhuangzi really were and the dates we have for them are educated guesses. However, we can understand the stories around them, keep a working knowledge about their lives, and absorb the intent of the beliefs about them.

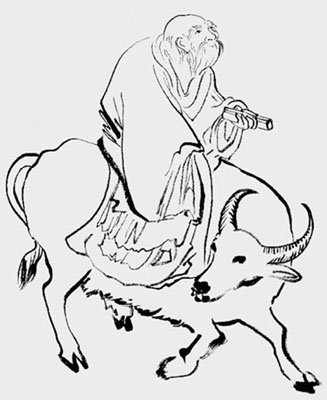

Laozi

Laozi literally means, “The Old Master.” According to the Records of the Grand Historian, he was a native of Chu, which places him in southern China. There is no clear knowledge of his exact dates, but he is often placed about the sixth century BCE. His surname was Li, his given name was Er, and he was also called Lao Dan. Laozi served as the keeper of the royal archives for the court of Zhou until he saw the decline of the dynasty and resolved to leave it, mounting a water buffalo to ride beyond the western border. When he reached the pass in Zhongnanshan, an official named Yin Xi asked him to put his teachings into writing. The result was a book of some five thousand characters—the Daodejing.

The Records of the Grand Historian recounts a meeting between Laozi and Confucius (551–479 BCE), where Confucius asks Laozi to give instructions about the rites. Similarly, the Record of Rites portrays Confucius quoting Lao Dan on proper funeral rites. The Zhuangzi also contains stories of encounters between Laozi and Confucius, but it’s impossible to tell whether these are historical or allegorical episodes.

Over the centuries, Laozi was venerated for many reasons, and the sum of all these efforts elevated him in Taoism and Chinese culture in general. The first organized Taoist religion in the second century, called the Way of the Celestial Masters (Tianshidao), made Laozi the personification of Tao itself. During the Tang dynasty (618–907), the imperial Li family traced its ancestry back to Laozi as Li Er. In the third–sixth century, the intellectual movement known as the Mysterious Learning (Xuanxue), also called Neo-Taoism, made Laozi the center of their thought. As a result, Laozi’s philosophy influenced literature, calligraphy, painting, and music. In 731, the Tang Emperor Xuanzong (685–762) decreed that all officials should have a copy of the Daodejing, and he placed the book on the list of texts to be used for the civil service examinations.

The speaking platform on Zhongnanshan, marking the place where Laozi gave his first discourse on the Daaodejing.

© Photo by Peter Pynchon

The religious Taoists made Laozi one of the gods of the highest trinity, the Three Pure Ones, with the title Great Supreme Old Lord.

The Daodejing was translated into Sanskrit in the seventh century. By the eighteenth century, a Latin translation was brought to England. There are some 250 translations of Laozi, with more than one hundred in English, and more being added each year.

Whether there was an actual person named Laozi is academic at this point. The figure of Laozi has become the nexus for concerns from the philosophical to the political to the religious. Merely to reduce him to normal biographical parameters is to miss much of his importance. On the other hand, the lack of solid evidence about him makes him as mysterious as his own writing—and in the end, we are left with what we started with: one of the world’s greatest books of wisdom. Regardless of who Laozi may have been, it is his gift to us that truly matters.

Zhuangzi

The name Zhuangzi means “Master Zhuang.” His personal name was Zhuang Zhou. Much like Laozi, we cannot be certain of his dates, but he is usually placed in the fourth century BCE during the Warring States Period (475–221 BCE). He is believed to have come from Meng City (Meng Cheng) in what is now Anhui. Scholars dispute whether he is an actual person or whether the Zhuangzi is a text constructed by a group of writers. Perhaps he’s fiction. Perhaps he’s simply a person following Taoist philosophy of self-effacement and modesty. Certainly, there are peudo-autobiographical references in the Zhuangzi itself. The picture of a witty philosopher emerges.

People today ask, “What is it like to live as a Taoist?” Zhuangzi’s sketches of himself help answer that question. Here are just a few of them:

Huizi (380–305 BCE; a philosopher and representative of the School of Names famous for ten paradoxes of the relativity of time and space) told Zhuangzi that he had been given seeds and had grown a large gourd. But then he didn’t know what to do with it. When filled with water, he could not lift it. He cut it in half to make drinking vessels, but the pieces were too big and unstable. He threw the gourd away. Zhuangzi reproached him: why didn’t he use the gourd to float over the rivers and lakes?

Huizi compares Zhuangzi’s words to a big tree that is large, but so knotted and crooked that no carpenter can use it for straight timber. Zhuangzi retorts: “If so, why don’t you plant this tree in the barren wilds? Then you could saunter idly by it or sleep under it. No axe would shorten the tree’s existence. Why should uselessness cause you distress?”

Huizi asks: “Can a person be without desire?” Zhuangzi replies that this is possible. “Tao gives a person appearance and ability. Heaven gives bodily form. You subject yourself to toil. Heaven gave you the form of a person but you babble about what is strong and white.”

Zhuangzi was fishing in a river when the king of Chu sent two emissaries to say: “I wish you to rule all within my territories.” Zhuangzi continued fishing and without looking around said, “I have heard that in Chu there is the shell of a divine tortoise who lived three thousand years ago. The king keeps it in his ancestral temple, covered with a cloth. Tell me, was it better for the tortoise to die but be so honored? Or would it have been better for it to live, dragging its tail in the mud?”

“We suppose that it would be better for it to be dragging its tail in the mud,” replied the officials.

“Go away, then,” said Zhuangzi. “Let me drag my tail in the mud.”

When Zhuangzi’s wife died, Huizi went to express his condolences. He found Zhuangzi squatting on the ground singing, and pounding a basin like a drum. “When a wife lives with her husband, brings up his children, and dies in old age, to wail for her is not even enough expression of grief. Instead, you drum on a basin and sing. Isn’t that improper and strange?”

Zhuangzi replied that he was indeed affected by the death, but then, reflected, “Before she was born, she had no life, no bodily form, and no breath. In the intermingling of the waste and dark chaos came a change. Then there was breath; another change, and then came a body; another change, and thus came birth and life.

“There is now a change again, and she is dead. The relation between phases is like the sequence of the four seasons from spring to autumn, from winter to summer. She lies with her face up, sleeping in the great chamber. If I were to fall sobbing and wailing for her, it would mean that I didn’t understand what is meant for us all.”

Zhuangzi dreamed that he was a butterfly, flying about, enjoying itself. He did not know he was Zhuangzi. When he awoke, he found that he was Zhuangzi. He did not know whether he had been Zhuangzi dreaming that he was a butterfly, or if he was a butterfly dreaming that he was Zhuangzi.