Moonlit Night

Deep in the night, moonlight half-floods my house

The North Star rises above the railing, the South Star falls.

Tonight I feel the warm spring air keenly:

new insect song through the green window screen.

—Liu Fangping (eighth century)

The two solar terms within this moon:

INSECTS AWAKEN

SPRING EQUINOX

the twenty-four solar terms

Insects and animals awaken from hibernation. Thunderstorms occur. Signs of spring are everywhere. As insects increase in activity, so too does the pace of the countryside grow quicker.

This exercise is best practiced during the period of 1:00–5:00 A.M.

1. Sitting cross-legged, close the fists tightly, with the thumb inside the fingers.

2. Turn the head from side to side, moving the elbows up and down like the wings of a bird each time for thirty repetitions.

3. Facing forward with your hands resting on your lap, click your teeth together thirty-six times. Roll your tongue between your teeth nine times in each direction. Form saliva in your mouth by pushing your cheeks in and out. When your mouth is filled with saliva, divide the liquid into three portions.

4. Inhale; then exhale, imagining your breath traveling to the dantian and then swallow one-third of the saliva, imagining that it travels to the dantian.

5. Repeat two more times until you’ve swallowed all three portions.

6. Sit comfortably as long as you like.

Through this exercise, ancient Taoists sought to prevent or treat toxins and relieve back pain; obstructions in the back, lungs, and stomach; dry mouth; yellow eyes; swelling; loss of sense of smell; and darkening of vision.

All things begin and end with the sun:

the sun makes us the sun of our lives.

Even before people understood that our earth revolves around the sun, they understood that the sun was central to our existence. Without the sun, we would have no warmth, no heat, no day, no light, no growth. Life would be impossible, and our planet would be a dark, icy lump, untethered and doomed.

Our calendar is a record of the sun. Even the moon, which defines the phases of the calendar, would not have light and would not have a planet around which to revolve. Taoists understood that there are many things worth our reverence, but the sun held so much reverence that it was given festival days in three different periods of the year. This shows the enormous importance that the ancient people placed on it.

Besides being the maker of life, the sun also symbolizes understanding. So much of our knowledge depends on examination “in the light of day.” We call understanding enlightenment, and since the sun is our primary source of light, we associate it with seeing the truth.

With understanding, we can see that each of us is the center of his or her life, just as the sun is the center of our solar system. We must accept that our worlds revolve around us, not in an egotistical sense, but as an acknowledgment of responsibility. The sun exerts the gravity that holds the earth in the safety of its orbit.

If we are truly enlightened, if we have the light of the sun in our hearts, then we also know that we hold innumerable worlds and lives by the sheer force of our presence.

The sun makes us the sun of our lives in the same way that you are the child of the land where you were born.

• Festival of the Sun God

• Fasting day

The Sun God

The Sun God (Taiyang Xingjun) visits the Jade Emperor on this day to discuss plans for the coming year. The Sun God is honored as the bringer of warm weather, and because the sun shines on good and bad alike, it is the symbol of impartial benevolence.

The Sun God’s actual birthday is on the nineteenth day of the third moon, and he is also honored with a third festival on the nineteenth day of the eleventh moon.

You are the child of the land where you were born.

You belong to the land where you choose to live.

Tudi specifically means the local or native land. Taoists believe that there are gods of the land in every local area, in every district, in every village. This goes along with worship of nature spirits, because there are also gods of trees, rocks, streams, flowers, plants, and every other part of nature. Nature is alive; nature has spirits worth reverence; nature has a consciousness that is responsive, beneficial, and active.

Every person is the child of his or her tudi. It’s your home territory, the place you love, the place that stays connected to you, the place that nourishes you like no other land.

We all understand that inside. Many times, we’ll ask a new acquaintance where he or she was born because it reveals something unique and important. We talk about going back to our roots. The land exerts a powerful pull on us. It is our own personal gravity—our special home.

We could not exist without the land. All our food and water comes from the land. The air we breathe is renewed by the breath of plants. We belong to the land and the land belongs to us, and we must never forget to honor that.

If we take care of the land, the land will take care of us.

You belong to the land where you choose to live, just as words last as if written on the body.

• The Spring Dragon Festival

• Birthday of God of the Local Land

Spring Dragon Festival

The Spring Dragon Festival (Chunlong Jie), or the Second Moon, Second Day (Eryue Er), calls the rain dragon to lift his head and send rain. In olden times, families in northern China drew water before dawn and returned to offer sacrifice in a ceremony called “attracting the dragon in the fields.” Then they ate noodles, symbolizing “lifting the dragon’s head,” and shared fry cakes, which meant “eating the dragon’s gall bladder” (symbolizing courage). Popped corn represented “golden beans” to attract the dragon, encourage rain, and bring plentiful crops.

The God of the Local Land

Every place has its own God of the Local Land (Tudi Gong), and there are thousands of altars by roads and canal banks, and on the floors of homes and businesses. Along with the Kitchen God, he dwells with us on earth. The god is depicted as a kindly old man with a white beard, and his wife, the Goddess of the Local Land (Tudi Po), often appears next to him.

The God of the Local Land aids and protects the residents and helps travelers in need. If there are disasters or other significant events, he reports them to the Jade Emperor.

The God of the Local Land has an unusual story. The Song Emperor Taizu (1368–1399) once arrived at an inn to find all the tables occupied. Seeing the image of the God of the Local Land on an altar table, he ordered it moved to the floor, saying to the god, “Give me your place.” After the emperor departed, the innkeeper was about to restore the God of the Local Land to his rightful place, but the god appeared in a dream and said, “I dare not defy the emperor.” From that day on, the God of the Local Land preferred to remain on the floor with no stand or table.

Words last as if written on the body.

True words must be pure as brightest sunlight.

By contemplating the name Wenchang, we can think of how important literature is. Words should be as meaningful and lasting as something we would choose to tattoo on ourselves. Words should be true enough that they can be uttered openly in the light of the sun.

Being literate is a basic and necessary skill in this world. Unless you can read, write, and express yourself, you won’t get far. Worse, you can easily fall victim to those who manipulate language, the news, contracts, and laws.

The most wonderful aspect of being literate is the ability to read the words of the greatest thinkers yourself. We approach the author as peer, giving the words all the consideration we can—we read them by the light of our own sun. No one needs to filter the truth for us. No one needs to interpret for us. No one can bar us from the instant and searing understanding that comes from the direct impact of great words.

If we are literate, then we can also express ourselves and speak words charged with the power of our own souls. We give testament to our existence, and we convey our truth to others. When we do that, then we truly are expressing literary glory as bright as the sun.

True words must be pure as brightest sunlight; only then can you enjoy each day without rush to grow old.

• Birthday of the King of Literary Glory

Literary Glory

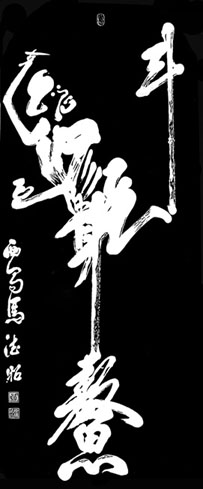

The King of Literary Glory (Wenchang Wang), the God of Literature, appears as a bearded scholar riding a white horse. Two grooms whose names imply discretion stand behind him—Deaf Heaven (Tianlong) and Mute Earth (Diya).

A demon balanced on one foot atop a carp (a homophone for success), Kui Star (Kui Xing), stands in front of the king as his vanguard and as the one who bestows literary degrees. His body and limbs form the word kui, as shown on the right, and he’s standing on the calligraphic ao, the name of a mythological sea turtle. His left foot supports the word “ladle” (dou)—a reference to dispensing degrees to the Big Dipper; Kui is believed to be the four stars of the body of the Big Dipper.

There is a fourth attendant as well: Red Robes (Zhu Yi), who helps those who have a poor chance of passing the examinations.

All the attendants can be depicted holding various symbols of the cultured life: scrolls, books, and three-legged bronze vessels from the Zhou dynasty (ding).

Wenchang

Wen, the word for “literature,” also means “culture.” The ideograph was derived from a picture of a tattooed chest. The second word, chang, or “glory,” also means “to prosper” or “flourish.” The character combines the sign for “sun” above the sign for “word.”

Enjoy each day, without rush to grow old—

make each day the foundation for the next.

There is a pattern to the seasons. There is a pattern to the year. One day passes after the next in perfect and unvarying sequence.

Our lives move in the unvarying sequence of the days and within the larger cycles of the calendar such as the four seasons. It is by such cyclical alternations that our lives ratchet in even measure.

Given that process, we need not rush to grow older. It’s impossible: one day is the same length as the preceding one, and to wish for anything other than that is to divorce ourselves from today. It’s just as foolish to wish that we were younger: who we are today is the result of all the days that have gone before. Not only is it unrealistic to unwind our days, but to even think of that invalidates and dishonors who we are.

Let us be completely aware of who and what we are today. Let us embrace it, make the best of it, celebrate it, and see how this day will lead to tomorrow.

We celebrate birthdays every year, but we should look beyond the counting of years to the counting of days. At the age of eighteen, you’ve been alive 6,570 days. Before the age of twenty-eight, you have exceeded 10,000 days. By fifty, you have reached 18,250 days. Standing on any of those sums is cause for gladness and cause for confidence: your foundation is deep.

Make each day the foundation for the next, and always avoid the greatest sin.

Pattern Leads to Principle

Li, the word for “pattern,” originally indicated veins and grain in jade. It also means “principle” in the most profound philosophical sense.

When people speak of reason and principle, they combine the word Tao (dao) with li: daoli.

In the “Great Appendix” to the I Ching we find these words:

Look up to contemplate the patterns of heaven. Bend down to examine the principles of earth. . . .

and . . .

Knowing that change is easy and simple, one can obtain the principles of all under heaven.

Avoid the greatest sin:

Avoid separation.

Taoists are seldom absolute about anything. It’s understood that all is relative, and that something bad in one context may be perfectly good in another. However, a Taoist will nearly always avoid separation for several reasons.

First, there is Tao itself. A Taoist doesn’t wish to be separated from Tao. It may happen occasionally, perhaps because of illness or some egoistic decision on the part of Taoist, but the immediate goal is to get back in touch.

Second, there is the social context. While Taoists advocate withdrawal into contemplation, something that by necessity is usually done alone, very few people can live in complete solitude and provide for all their needs without anyone else. People need other people, and so a Taoist avoids alienating others or falling into paralyzing isolation.

Third, a Taoist realizes that all is relationship. Some are minor, some are profound, but all are relationships nevertheless. Even conflict requires engagement: when a person attacks another, a relationship occurs, however temporary.

If a Taoist is to deal with conflict, the worst thing is to lose touch with the other person. In a martial arts match, for example, whenever an opponent attacks there must be a lowering of defenses. If an attack is to be met, there can be no separation, for the moment of attack is exactly when a chance for counterattack opens. The Taoist avoidance of separation means always being in touch.

It is by keeping in touch with all around us that we keep in touch with the Way.

Avoid separation and make pilgrimage to your sacred mountains.

Pushing Hands

Taijiquan, a Taoist martial art, takes an unusual approach to fighting. Instead of attacking from a distance with overwhelming force, the Taiji fighter establishes a relationship by touching the opponent lightly throughout the match. The Taiji fighter does not separate from the adversary.

With that contact, the fighter can sense the opponent’s movements and intentions and thereby “arrive before the opponent.” The fighter easily deflects or dodges and can take advantage of any opening. That is why the Classic of Taiji (Taijiquanjing) speaks of “deflecting a thousand pounds of force with only four ounces of strength.”

Students of Taijiquan learn this skill through a controlled sparring exercise called Pushing Hands (Tuishou).

The Unity of a Ruler with the People

The Guanzi, a collection of ancient writings attributed to Guan Zhong (c. 720–645 BCE), has this passage about a ruler’s heart:

Taking the heart of the hundred clans as his own heart is called “one body.” When a state is of one mind, the myriad people have one heart.

Make pilgrimage to your sacred mountains.

Find the vantage closest to your heaven.

Each of the Five Sacred Mountains is a center of history, spirituality, art, and poetry. Pilgrimages to the sacred mountains are highly valued as inspiring, reverent, and beneficial journeys. Pilgrims believe that they can absorb the power of the mountain and the divine power of heaven. The makers of the lunar calendar wanted to encompass the entirety of human existence: by preserving observation days for each sacred mountain, the lunar calendar incorporates both time and place.

What are the sacred mountains in our own spiritual landscape? That can be a literal question—are there mountains near where you live that are special to you? It can be a metaphorical question—what are the peaks of your inner landscape? In either case, they are mountains to be discovered. They are mountains to be climbed.

In the past, people ascended mountains to be closer to heaven and far from the corrupt human world. Such Taoists are called “immortals” or xian—the word combines the character for “person,” on the left side, with the character for “mountain,” on the right side. Retreating from the world for spiritual practice, it was called to “ascend the mountain.”

Some Taoists believed that the Eastern Peak was the actual home to gods—therefore, it was heaven. Others believed souls flew to the Eastern Peak upon death—which places paradise on the mountain. All these examples show mountains as symbols of greatness and as places for spiritual cultivation.

Each of us has Five Sacred Mountains inside us. Ascend them, and you are closer to your heaven. Be a “person on a mountain,” and you are on your way to becoming an immortal.

Find the vantage closest to your heaven to discover that each pilgrimage is a circle.

• Birthday of the Great God of the Eastern Peak

The Five Sacred Mountains

The Five Sacred Mountains (Wuyue) in China are believed to have been formed by the body of Pan Gu. They are:

Taishan (Tranquil Mountain), the East Great Mountain (Dongyue), Shandong. Considered the first of the five mountains.

Huashan (Splendid Mountain), the West Great Mountain (Xiyue), Shaanxi

Hengshan (Balanced Mountain), the South Great Mountain (Nanyue), Hunan

Hengshan (Permanent Mountain), the North Great Mountain (Beiyue), Shanxi

Songshan (Lofty Mountain), the Central Great Mountain (Zhongyue), Henan

In this book, each mountain’s ancient graphic symbol appears on the page describing it.

The Great God of the Eastern Peak

The Great God of the Eastern Peak (Dongyue Dadi) exorcises evil spirits and receives the souls of the dead, which float to Taishan. He determines people’s fortunes, the success of officials, and the length of lives. He also administers the Eighteen Levels of Hell.

Each pilgrimage is a circle

we travel to return transformed.

Pilgrimage is honored the world over. In the ancient world, there were Karnak, Thebes, Delphi, Ephesus, Jerusalem. In Buddhism, there were Lubini, Bodhi Gaya, Sarnath, Kusinara; in India, the caves of Sanchi, Ellora, Ajanta; in Tibet, Lhasa; in Indonesia, Borobudor. In Hinduism, there are dozens, beginning with the four sites of Char Dham: Badrinath, Dwarka, Jagannath Puri, and Rameshwaram. In Islam, there are Mecca and Medina. In Judaism, there is the Wailing Wall. In Christianity, there are the Holy Land and cathedrals and churches throughout the world. And the many sites of Taoism show how the ancients viewed the land as sacred.

We may also go on personal pilgrimage, to places where a poet, musician, or artist once lived; to pay our respects to a historical battlefield; to stand where a famous peace activist once stood; or simply to see what the first explorer must have seen.

The key to pilgrimage is to embark on the trip with a heightened intention. We are not just tourists. We’re going to honor someone or something. By honoring what is sacred to us, we make it more real in our lives. We join with it.

Inevitably, we return from pilgrimage, and this is an essential part of the meaning as well. We’re supposed to return to our normal lives, except that we return transformed, carrying the experience with us forever, having touched the reality of what we love, having walked in the same dust as the thousands who also have the same beloved.

Finding something sacred in our lives, traveling there in devotion and commitment, humbling ourselves, sharing the experiences with others, and coming back transformed—all these are human expressions, human necessities. Pilgrimage is spiritual human migration. A sacred place makes us sacred.

We travel to return transformed, even if we face stress and mutilation each day.

Some Places of Pilgrimage in China

Here is a partial list of pilgrimage sites:

The Three Great Mountains of the Orthodox One Sect (Zhengyi): Longhushan, Maoshan, and Gezaoshan

The Three Great Ancestral Palaces of the Complete Perfection Sect (Quanzhen): Yongle Palace, Chongyang Palace, and Baiyun Guan

The Longevity Palace of the Pure Brightness Sect (Jingming), Xishan

Singing Crane Mountain (Hemingshan), associated with Zhang Daoling (34–156) and the Five Pecks of Rice School (Wudoumidao)

Wudangshan, Hubei, home of Taoist martial arts and the North God (Zhenwu—)

Laoshan, Shandong, the dwelling place of immortals

Many shrines and temples exist in virtually every city of China, other Asian countries, and abroad—including temples in the United States.

The North God, Zhenwu, on Wudangshan. Note how he sits in his own alcove and how he’s draped with an actual cloak.

© Bernard De Poorter

We face stress and mutilation each day.

Since we only die once, what’s right to do?

Sima Qian was deeply committed to righteousness and duty to posterity, but he was shamed for it. His predicament is repeated every day for millions of people at the hands of government, bosses, or family members. For all of us, Sima’s story is important in five ways.

First, Sima Qian spoke out against injustice. General Li Ling commanded five thousand troops against the Shanyu, part of the Xiongnu (from areas that include present-day Siberia, Mongolia, and Manchuria). Vastly outnumbered, the Chinese troops fought to the death. Li Ling was captured, and Emperor Wudi condemned him to death in absentia. When Sima Qian was told to state his opinion, he spoke honestly.

Second, not a single person interceded on his behalf. No one spoke for him or offered the money that could have spared him.

Third, suicide was considered more honorable, and yet Sima Qian wrote that had he committed suicide, people would have assumed that he had had no other alternative. He was determined to finish his father’s work. If not, he wrote, he could never have been able to visit his parents’ graves, and he declared that “a man has only one death.”

Fourth, the castration was physically, mentally, and socially devastating. Sima Qian stated that there was “no greater defilement” and that he would “not be considered a man anywhere,” since eunuchs were universally detested. Sima described himself as a mutilated wretch, fit only for serving in palace women’s apartments, whose only hope for vindication was for his histories to be read after his death.

Fifth, he recovered his sanity after being bound, stripped, beaten, imprisoned, and castrated. He gasped with fear, he wrote, having been overawed and broken by force.

Sima Qian, a great man in world history, reminds us to study the past diligently because the injustices he endured and recorded are constantly repeated in every country around the globe. The powerful humiliate us every day, but our forbearance must be stronger than the oppression that would crush us.

Since we only die once, what’s right to do? What is your Work? What do you leave behind?

• Commemoration day for Sima Qian

• Fasting day

The Grand Historian

Sima Qian (c. 145–90 BCE) is considered China’s foremost ancient historian. His work covers over two thousand years (2696–87 BCE), from the Yellow Emperor to Han Emperor Wudi. He completed his Records of the Grand Historian under considerable tribulation and is remembered for clear writing and great determination.

Beginning at the age of twenty, Sima Qian traveled across China, collecting information and verifying as much historical detail as he could. After he entered the imperial service, he was assigned to reform the calendar and advise the emperor. Sima Qian created the Great First Calendar (Taichuli), which defined a year as 365.250162 days (quite close to the current duration of 365.242199 days).

Sima Qian’s father, Sima Tan (c. 165 –110 BCE), had begun writing an ambitious historical record. He asked Sima to complete the enormous task as he was dying.

However, in 99 BCE, Sima Qian addressed Emperor Wudi (156–87 BCE) in defense of General Li Ling, who was blamed for a disastrous defeat. This enraged the emperor, and he ordered Sima executed. The condemnation could only be commuted by money or castration. Sima Qian had no money. Desperate to complete the responsibility his father had given him, Sima Qian endured the pain and humiliation of castration and imprisonment. Upon his release in 96 BCE, he worked to complete his masterpiece.

His tomb and memorial temple are in Han Cheng, Shaanxi. The story here is taken from Sima Qian’s “Letter to Ren’an.”

What is your Work? What do you leave behind?

Do you choose slashing sword or freeing brush?

What do you live your life for? What do you try to leave behind? How many tourists on the Great Wall ever stop to consider the fate of the general who was ordered to build it? How many people who write with brushes are aware that the same general influenced the form of the brush we still use some 1,800 years later?

When General Meng Tian was ordered to commit suicide, he said that his family had loyally served the dynasty for three generations. As the head of 300,000 troops, he could have ordered a revolt. He did not do so because he could not bear to disgrace his ancestors or forget his debt to the late emperor. He was not trying to avoid death, he said, but to make it a remonstrance so that the emperor would return to the Way. When the envoy demanded that the decree be carried out, Meng Tian asked why he should have to die an innocent death. After a long while, he decided that in building the Great Wall, he had cut the arteries of the earth, and for that, he had to atone. Then he swallowed the poison.

Sima Qian, in recording this, did not agree with Meng Tian. He himself toured the northern border and traveled the roads that the general had built. Yes, he had cut through mountains and valleys, but he had done so by the forced labor of millions of people. Sima Qian concluded that Meng Tian had not remonstrated with the emperor forcefully enough, that he had not relieved the ills of the common person, the elderly, and the orphaned.

What is ambition? What is loyalty? What is accomplishment? What is righteousness? We ask what we should do in this life, and we ask what we should leave behind. Do we choose the path of power at the expense of others’ lives? Or do we choose the path of obscurity, and thereby preserve lives? Meng Tian wielded both the sword and the brush.

He chose the sword.

Do you choose slashing sword or freeing brush? Why not put both aside and, beginning at the bottom, climb a mountain path?

The Fate of a General and the Builder of the Great Wall

General Meng Tian (d. 210 BCE) served Qin Shi Huang (The First Emperor). He was descended from a line of warriors and military architects—his father and grandfather had also been generals—and Meng commanded an army of 300,000 men against the Xiongnu nomads who constantly threatened to invade China. When Qin Shi Huang wanted the Great Wall of China built, he ordered Meng Tian to head the project.

Meng Tian was accomplished in other ways as well. He improved the writing brush, and brush makers of Huzhou trace their tradition to him. Meng was also a road builder, constructing a network of roads to expand both commerce and international exchange.

In fact, Qin Shi Huang died while he was traveling on a road that Meng Tian had built for the emperor’s personal tour of the empire. The eunuch Zhao Gao (d. 207 BCE) and Chancellor Li Si (c. 280–208 BCE) conspired to hide the death, accused both the designated heir and Meng Tian of treason (Li Si feared Meng might replace him as chancellor), and offered them the “honor” of suicide. The prince capitulated quickly, but Meng Tian resisted and was imprisoned.

The new emperor sent an envoy ordering Meng Tian’s suicide. Meng Tian gave a long and eloquent protest preserved in the Records of the Grand Historian. The envoy refused to relay the words to the emperor. Seeing no choice, Meng Tian swallowed the poison.

The line running vertically on the left side of this picture is a portion of the Great Wall of China in a radar image.

Courtesy NASA/JPL-Caltech

Beginning at the bottom, climb a mountain path.

Meet the sage at the peak, and find that it is you.

This depiction of Taoist inner landscape shows the path to enlightenment because, for Taoists, enlightenment requires the transformation of physical energy. Starting at the base of the torso, the practitioner raises raw energy up the spine—shown as a rocky mountain path—to be refined and cultivated at each of the three dantian (fields of cultivation). The agrarian imagery is unmistakable.

Finally, the energy reaches the crown, where one discovers Laozi. The wisdom that one reaches by this spiritual journey is one’s own. The refinement of energy and the activation of important centers power realization.

Some Chinese landscape paintings don’t depict an actual place but, instead, a “mind-journey.” The artist began in one place and painted in a spontaneous and continuous exploration. The painting became a record of meditation, of movement in some inner space. Likewise, the Classic of the Yellow Court reads as one long ecstatic journey through what is at once body and landscape.

Taoists make no separation between the body and the mind. They are one. The body can be used to raise one’s spirituality. The spirit can be used to heal the body. All is continuous.

Meet the sage at the peak, and find that it is you; then descend to wander the rivers and lakes.

The Internal Classic Diagram

This is a rubbing of the Internal Classic Diagram (Neijing Tu). It was made by Liu Chengyun, whose Taoist name was Suyun Daoren—the Plain Cloud Taoist. This carving has an estimated date of the nineteenth century and shows the path of energy from the base of the torso to the crown.

Wander the rivers and lakes.

Chase after the divine breath.

Just as a Taoist tries to raise spiritual energy up the spine to the crown as if climbing a mountain trail, so all of nature is seen ecstatically as a spiritual place. The Five Sacred Mountains are one manifestation, but Taoists believe that there are special places and energy spots everywhere and that there are meridians of power, or places of the divine breath, just as there are acupuncture meridians in a human body. Taoists literally see microcosm and macrocosm as one.

Many Taoists love nothing better than to wander the world to chase after this divine breath. This breath might be found by looking at the contours of the land. For example, the “spine” of a mountain is believed to be a “dragon meridian.” Walking that line will allow a person to feel the energy of the land.

The divine breath moves. A place can become stagnant and uncomfortable. Another place can seem beckoning and stimulating to one’s vitality. There are no set rules for this. One simply has to chase it, dancing spontaneously with nature’s relentless process of change and renewal.

In ancient times, people believed that heaven was rooted in several places on earth. The Ten Greater Grottoes, the Thirty-Six Lesser Grottoes, and the Seventy-Two Lesser Realms were all places where heaven or immortals lived on earth.

Heaven is not separate from earth. Spirit is not separate from the body. A human being is not separate from the earth. Heaven and earth exist within us.

Chase after the divine breath—beyond where the flock of black wings cross the sky.

The Ten Continents and Three Islands

Beginning in the Warring States period (475–221 BCE), Taoists believed that gods and immortals lived in special places on earth. They imagined palaces of gold and silver, and places where the elixir of immortality might be found. Numerous naval expeditions were sent to find islands in the Pacific where immortals dwelt, but none were found. Nonetheless, people continued to believe in the Ten Continents and the Three Islands.

Chief among the mythical islands of immortals was Penglai, and there are many references to it in Taoist literature. This island was thought to be on the eastern side of the Bohai Sea.

Taoists also believed that there were places where mortals could go to become immortal, and that heaven intersected with the earth at certain points. These were called the Ten Greater Grotto Heavens, the Thirty-Six Lesser Grotto Heavens, and the Seventy-Two Lesser Realms. All of these places have actual locations in China. Most have unique and beautiful scenery—inspiring people to believe in ”heaven on earth.”

© andelieya

Flock of black wings cross the sky.

Birds are not afraid of direction.

The sky is infinite. Its blue is unblemished. Beyond our atmosphere, we know that the sky is part of a black space that is endless in all directions and that there is neither up nor down, east nor west in it. The limitlessness of space is far more than we could ever measure by any human scale.

The measurement of a light-year was invented to cope with this overwhelming space. We used the distance it takes for light to travel one year. We took the enormity of our travel around the sun and used it to measure a space billions of times greater. In ancient times, distances were measured by the length of the king’s thumb. We are only a little more sophisticated today in comparison to the enormity of the universe around us.

The birds think nothing of such speculations. They fly to seek food or better weather, or to build a nest. The endless expanse of space is there—perhaps we could even call it their home—and yet they choose their directions and fulfill their lives. They are not undone by infinity. They simply use infinity in all that they do.

Birds are not afraid of direction, and neither must we be, even if we must all sail upon vast floods.

The Universe

The modern Chinese term for “universe” or “cosmos” is yuzhou. Yu has the sign of a rooftop and eaves on top and therefore alludes to the rooms and the structure of a building. Zhou means “time,” including the concept of infinite time. Thus, the word for “universe” alludes to infinite space and infinite time.

The Masters of Huainan (Huainanzi)—a second-century BCE philosophical classic that was the result of discussions between the prince of Huainan, Liu An (177–122 BCE), and scholars in his court—states: “Going back to the past and coming to the present is called ‘zhou’ [time]. The four directions and above and below are called ‘yu’ [space].”

NASA/JPL-Caltech/ESA/CXC/STScI

We must all sail upon vast floods—

with our knowledge, wisdom, and faith.

The literal translation of Hung is “flood.” Although this is simply the sage’s surname, it seems strangely apt that a god who protects against the dangers of the oceans has a name that literally means “Sage of the Flood.”

Just as the sky is infinite, so too are the oceans. They are the greatest of floods, covering much of the earth. One can sail upon them forever without stopping. But to sail on such an expanse is as treacherous as it is exhilarating, and so it makes sense that people turned to divine help.

Those who live on the oceans may have the greatest of skills. Boat people live their entire lives on boats and fishermen have to navigate and find food too. Hung Shing encouraged the use of astronomy, geography, mathematics—all good forms of knowledge for those who would sail the seas. Yet even after all that we do, we sometimes need something extra to face the unknown. Some call it luck. Some call it the protection of the gods. Whatever you call it, it means faith in the end.

We all must navigate vast floods during our lifetimes. We must all find a way to set a course by the stars, even as all that we see around us seems to be wave upon wave. We don’t know what is beneath us—opportunity, like fish to catch, or danger, like dangerous currents or rocks? Yet like the sailors, we must continue on even if the ocean is deadly. We must go on, knowing that divine help will come.

With our knowledge, wisdom, and faith, let us awaken to this dream! Then keep dreaming.

• Festival day of Hung Shing

Sage Hung

Hung Shing (Hongsheng), also known as Grandfather Sage Hung and Tai Wong (Daiwang), was originally Hung Hei (Hong Hei), a government official of the Tang dynasty who served in present-day Guangdong. While in office, he promoted the study and use of astronomy, geography, and mathematics, and established an observatory. After he died at an early age, he was granted the title Sage King Hung Great Benefactor of the South Sea. People believed that Sage Hung continued to guard them against storms and other disasters, and there are many temples to him in Guangdong and around Hong Kong. He is especially revered by fishermen, sailors, sea traders, and boat people.

Awaken to this dream! Then keep dreaming.

Be the dreamer who’s aware of the dream.

This is the time of Insects Awaken, when the insects that have been dormant during the winter return to activity as the weather warms. Living creatures accord with the seasons, entering dormancy when necessary and awakening when the season changes.

The greatest awakening is spiritual awakening, that profound insight into the truth of our existence and the nature of the world. Having such an awakening dispels all doubts.

All of us have had the experience of nightmares, and all of us understand the relief of waking up and sighing, “It was all a dream!” Since so much of meditation and Taoist practice is internal, this makes an interesting question. How do we distinguish the trap of our inner anxieties from the capacity of our minds to awaken to the great truth?

We join with Zhuangzi in his ambiguity.

Be the dreamer who’s aware of the dream, even if you struggle to say: “The Way that . . . the name that . . .”

• Fasting day

The Butterfly Dream

One of Zhuangzi’s most famous parables is this:

I, Zhuangzi, dreamt that I was a butterfly flitting about and enjoying myself. I did not know I was Zhuangzi. Then I woke up and I was Zhuangzi again. But I could not tell if I was Zhuangzi dreaming that he had been a butterfly—or if I was a butterfly dreaming that he was Zhuangzi. However, there must be some difference between Zhuangzi and a butterfly. We call this the transformation of things.

The Way that . . . the name that . . .

Then what does everlasting mean?

Laozi refers to the “Way that can be spoken” and the “name that can be named,” contrasting them with the “constant Way” and the “constant name.”

The word “constant” is the word chang. It also means “always,” “ever,” “often,” “frequently,” “common,” “general,” “rule,” or “principle.” The lower half of the word represents a cloth, as in a banner of a lord held up for all to see.

Tao that can be spoken is provisional and relative. It cannot encompass the constant Tao beyond words. In the same way, our name or classification for things cannot describe the ultimate truth. Our names are limited and finite. Tao is limitless and infinite.

In using the clumsy translation “not,” we can miss what Laozi meant. He avoided several other words meaning “no” or “not” and used a word, fei, that implied opposites. Look at the word, which was originally a picture of two wings. We cannot discard either side of the equation. Both sides are important. We need speaking and words, and we need to perceive the constant Tao that has no description for its eternal character.

The hero Yue Fei gives us a different sense of constancy—constancy of character. He was fixed on being loyal, patriotic, and merciful to the weak. When we read of the constant Way, we may ask how we can be constant in our own lives. Yue Fei’s determination to be brilliant, brave, and steady is one answer. That steadiness cannot be named, it cannot be categorized, but it is real and profound nevertheless.

Statue of General Yue Fei, Hangzhou. His own calligraphy appears above him: “Return my rivers and mountains,” meaning “Give back my nation.”

Go beyond words to see the constant Tao, and then you will learn what it is to be constant yourself.

Then what does everlasting mean if we do not wish for spring?

• Festival day for the Three Pure Ones

• Birthday of Laozi

• Birthday of Yue Fei

• Fasting day

Laozi

The opening lines of Laozi’s Daodejing have even become a proverb:

The Way that can be spoken is not the constant Way.

The name that can be named is not the constant name.

Image of Laozi, Yuanming Palace, Qingchengshan.

© Saskia Dab

Yue Fei

Yue Fei (1103–1142), a general of the Southern Song dynasty, fought against the invading Jurchen. Four words meaning,“Serve the nation with utmost loyalty,” were tattooed on his back.

In 1126, the Jurchen took the Song capital of Kaifeng and captured Emperor Qinzong (1100–1161). After several years’ war, Yue Fei was on the verge of retaking the capital. Fearing the return of Qinzong, Emperor Gaozong (1107–1187) plotted with Chancellor Qin Hui (1090–1155) to recall Yue Fei, who returned because he felt that his duty was to be loyal to whomever was emperor. Qin Hui had Yue Fei imprisoned and executed on false charges.

Yue Fei was a famous martial artist, poet, and calligrapher, and remains a paragon of loyalty. His temple stands in Hangzhou.

the twenty-four solar terms

The spring equinox is one of the two occurrences a year when the days and nights are of equal length. From this point to the summer solstice, the daylight hours increase.

Weather continues to grow warmer and more pleasant. Farmers plant rice paddies, corn, and trees in this period, and life in the countryside becomes more active.

This exercise is best practiced during the period of 1:00–5:00 A.M.

1. Extend your arms, with one palm pressed on the back of the other. Extend one leg.

2. Turn the head to the left and the right twenty-one times. Then switch legs and palms, turning to the left and the right twenty-one times. Inhale on the turn, exhale in the center.

3. Sit cross-legged and face forward. Click your teeth together thirty-six times. Roll your tongue between your teeth nine times in each direction. Form saliva in your mouth by pushing your cheeks in and out. When your mouth is filled with saliva, divide the liquid into three portions.

4. Inhale; then exhale, imagining your breath traveling to the dantian and then swallow one-third of the saliva, imagining that it travels to the dantian.

5. Repeat two more times until you’ve swallowed all three portions.

6. Sit comfortably as long as you like.

Through this exercise, ancient Taoists sought to prevent or treat weakness; poison in the chest, shoulders, and back; tinnitus; feverishness; and pains in the upper torso.

We do not wish for spring.

Spring gives life to wish.

Spring comes back each year—and we welcome it joyously. Even if it is stormy on this day, we know that the storms will pass. Even if it is dark on this day, we know that daylight will grow steadily longer.

There are often references to a second spring in one’s life. Can we reclaim our youth? There are also references to eternal spring. Can we stay forever young? Perhaps these ideas were not wishful thinking. Perhaps they were uttered by those who saw spring return each year, and who thought it was natural that we should have spring return to our bodies each year as well.

And so it does. We find renewal in our lives constantly. Every morning when we wake, we are reborn. Every time we recover from illness, it is like spring following winter. Every time we begin a new venture, start a new friendship, nurture a newborn, or undertake any number of other kinds of new efforts, it is spring again.

Our bodies consist of millions of cells. Some of them die each day, others are born each day. Winter and spring happen within us on an ongoing basis. There are cycles within cycles within cycles, and organization emerges from that. Coherence, identity, and meaning spiral out of the ongoing alternation of birth and death.

But on this day, the power of life asserts itself again. Growth buds, bursts, prepares itself for bloom. Blue skies and the welcome warmth of the sun are on their way, and for that we are both happy and grateful. Life quickens, and we quicken with it.

Spring gives life to wish, and we labor on, even if hidden roots and rocks block our plow.

Spring Song

Spring winds move a spring heart,

Flowing eyes gaze at a mountain forest,

a mountain forest of exquisite splendor.

Bright birds sing clear sounds.

This is a yue fu, a poem written in a folk song style. “Yue fu” literally means “music bureau,” a reference to the imperial agency charged with collecting and recording folk songs. This poem dates from the Northern and Southern dynasty period (420–589).

“Late Spring” by Han Yu

Han Yu (768–824) was a scholar, a teacher, an official, an essayist, and one of the poets anthologized in Three Hundred Tang Poems. He advocated a strong central authority in government and orthodoxy in culture. Noted as one of China’s finest prose writers, he is considered the foremost member of the Eight Great Prose Masters of the Tang and Song.

The grass and trees know spring is not far from returning.

Red and purple blooms, fragrant and lush, vie with each other in a hundred ways.

But poplar flower and elm seeds have no poetic feelings:

they only feel the flying snow fill the sky.

Hidden roots and rocks block our plow.

Sweat. Pull waste now and clear the way.

When a field is cleared, farmers cut down weeds, grass, and brush, and they dig up roots, rocks, branches, or the ruins of long-forgotten homes. All of these must be put aside in large piles until expanses of clean earth are left.

Look at the heaps: tangled stems, withered leaves, gnarled roots stained and pungent with damp earth. The pile is left to dry, and then it’s burned. The ash that’s left goes back into the soil.

The spiritual life is like that too. If we are to have any chance of gaining spiritual freedom, we need to clear our fields. When we do that, we will dig up traumas and injuries deep in our subconscious. All of these must be pulled out and then discarded with the diligence of a farmer clearing the field.

It’s hard work. When we survey the expanse of the field we must clear, the extent may be daunting. As we bend to the task, we may well find that the amount that we accomplish in a day is discouragingly small. But each bad thing dug up will never bother us again.

Dig up and discard the bad things in your past. Pile them up. Let them sit in the sun so that they wither and dry. Burn them, for you will be doubly free afterward. Your field will be clear, and it will be enriched by the very ash of what were once hidden obstacles.

Sweat. Pull waste now and clear the way. Then pause, as a farmer rests when his buffalo stops.

The Classic of Poetry

This portion of one of the works of the Classic of Poetry gives a vivid picture of agrarian life thousands of years ago.

They join to cut the brush and plow the ground,

clear a thousand areas, pulling roots up to the marshes and dykes.

The master, his eldest son, his younger sons, and their children all work.

When they rest, there is the sound of many people feasting; more food must be brought.

The men think lovingly of their wives, the wives stay close to their men.

Methodically, they plow the southern acres

and sow hundreds of seeds with such effort and work. . . .

Pull the Roots

“Cut the grass and pull the roots” is a famous idiom. Its connection to the farming life is obvious, but its implication is to take care of a matter once and for all, so that there can be no recurrence.

A farmer rests when his buffalo stops.

Which end of the reins is really guiding?

There are two classic scenes of the water buffalo on a farm. One is the buffalo pulling a plow. The other is the buffalo at rest, languishing contentedly, half-submerged in water and mud. Domesticated for some five thousand years, the water buffalo can survive on poor food sources, yet is strong and well suited to plowing muddy fields and rice paddies. A single buffalo can weigh as much as two thousand pounds.

As powerful as it is, a water buffalo cannot work all day. The plowman has to rest and feed the animal. Naturally, the farmer can also rest, or turn to other chores, accepting the limit to how much plowing can be done. Now we have machines that run on gas and electricity and that never get tired. We exceed what a single man and animal can do, when we use our engines rated in the hundreds of horsepower; our trucks, trains, and planes that need only a quick refueling; and our computers that we never power down.

Yet in our “advancement” over the single plowman, we have paid a price. We, the operators of our machines, are now driven to keep up a tireless pace. We do not bother to extend the consideration we show for a water buffalo to ourselves. Nuclear fuel, the combustion engine, ubiquitous electricity, computers and mobile devices drive us to work far longer hours than those lowly farmers.

Meanwhile, the water buffalo wallows in the mud.

Which end of the reins is really guiding, after compassion opens us to others?

• Fasting day

The Golden Water Buffalo of West Lake

West Lake (Xi Hu) in Hangzhou is one of the most beautiful places in China and perhaps in the world. The ample history and charms of the area have made it rich in folktales and legends.

During the Han dynasty (206 BCE–220), there was a golden water buffalo who lived at the bottom of the lake. Whenever the lake dried up, the water buffalo spewed water until the lake was full again.

The local officials wanted to present this marvelous animal to the emperor, and they ordered the people to drain the lake with foot-powered waterwheels. When the buffalo appeared, the officials dashed forward, vying with one another to capture it. But the water buffalo bellowed angrily and spewed water so quickly that the officials were drowned as the lake filled rapidly. Since then, West Lake has never run dry.

Guanyin was originally a Buddhist deity who was also adopted by Taoists as an immortal. She represents compassion, and her full name is Guanshiyin—the Hearer of the World’s Cries.

Guanyin is a bodhisattva—an enlightened being who is eligible for nirvana (liberation from suffering) because of exemplary living, great wisdom, and self-cultivation. However, like all bodhisattvas, she delays accepting this lofty status of becoming a Buddha to help all other sentient beings gain nirvana first.

Buddhism originated in India, and Guanyin began as an Indian and male bodhisattva named Avalokitesvara. He made a vow to help all sentient beings in distress. In the Lotus Sutra (Miaofa lianhua jing, or Fahuajing), Avalokitesvara has thirty-three manifestations—including a female one—so that his different forms can be suitable to a range of people. All the manifestations have the same purpose—to listen to the cries of those suffering and to help them.

Knowledge of Avalokitesvara came to China through the travels of Faxian (337–422) and Xuanzang (c. 602–684; featured in the epic novel Journey to the West), two monks who traveled to India on pilgrimage and who returned with Buddhist scriptures.

Miaoshan

Guanyin is widely known today as female, and there has been much scholarly speculation as to how this happened. It is probable that there were local deities similar to Guanyin who were absorbed into the worship of Guanyin. One likely example is the story of Princess Miaoshan.

In this story, the king wants his daughter, Miaoshan, to marry a wealthy man. She replies that she will consent only if the marriage can ease three misfortunes. When asked to explain, she replies, “The first misfortune is the suffering of people as they age. The second misfortune is the suffering of people when they fall ill. The third misfortune is the suffering caused by death. Unless my marriage can alleviate all three sufferings, I would prefer to take religious vows.”

Her father asks if anyone could do such things. Miaoshan replies that a holy person could address all three misfortunes. The king declares that he wants a man of wealth and power for a son-in-law, rather than some poor holy man. As punishment, he forces Mioashan into hard labor and reduces her food and drink. But Miaoshan will not yield and begs every day to become a nun.

Frustrated, her father sends her to a temple—with instructions that she be given the hardest chores to discourage her. She must work day and night, but the animals see that she is a good person and help her do her work. Then her thwarted father orders the temple burned down, but Miaoshan smothers the fire with her bare hands and isn’t hurt. Finally, her father orders her put to death.

Philip Lange/Shutterstock

As she is about to be killed, a tiger appears and carries Miaoshan to the underworld. Upon seeing the suffering of those in hell, she plays music, and blossoms shower down around her. Through her compassion, the suffering souls are liberated, and her presence begins transforming the underworld into a paradise. The king of hell hurriedly sends her back to earth to prevent the collapse of his realm.

Miaoshan returns to earth and lives in solitude on the island of Putuoshan (she is sometimes depicted calming a storm on the seas), where she continues to try to relieve the suffering of all the people on earth.

Guanyin with a Thousand Arms

Guanyin is depicted in many different ways—sometimes seated, sometimes standing in white robes, sometimes with her teacher Amitabha Buddha. But there is one distinct depiction: Guanyin with a Thousand Arms.

As the legend goes, Guanyin vowed to free all sentient beings from the suffering of reincarnation. The effort was strenuous, and after some time, she realized that there were still many more beings yet to be saved.

The struggle to comprehend the needs of all beings in the world was so intense that her head split into eleven pieces. Amitabha Buddha saw her plight and transformed each piece to give her eleven heads.

Now she could better hear the cries of the suffering, but she wanted to reach out to all whose cries she heard. Her two arms shattered into pieces from the strain. Once again, Amitabha came to her aid, transforming her broken arms into a thousand arms.

© Kathy Bick

Compassion opens us to others:

Each self is a gateway to the world.

Compassion is a noble virtue, and it takes on its greatest power when it arises naturally. There’s a level of compassion that is deeper than moral practice, deeper than mere empathy. The greatest compassion comes because we are the world and the world is us.

Perhaps this gives the greatest resonance to the bodhisattva vow—that one will refuse one’s own nirvana (liberation from suffering) until each person is the whole world and the whole world is us. There is no true liberation for any one individual while others are suffering. In reality, we will continue to suffer as long as one sentient being suffers.

The practical will say, “But there will never be an end to suffering.” The wheel of reincarnation will continue to turn. The very nature of existence is predicament.

What do you say? If you abandon all effort, then suffering becomes damnation. If you work to liberate all sentient beings, then the work can seem futile. Perhaps that’s why the masters teach that there’s a third point of view: that we must transcend duality. In the face of overwhelming odds, the enlightened person still chooses compassion. Every day. Every moment.

Each self is a gateway to the world we try to sweep clean, but no matter how soft, the broom wears down.

• Birthday of Guanyin, Goddess of Mercy

Guanyin in Popular Belief

In popular belief today, many people ascribe even more attributes to Guanyin than her compassion for all people. She is regarded as the embodiment of unconditional love and mercy and as the protector of women and children. Women hoping to become pregnant pray to her or visit her temple. She is also seen as the champion of the sick, the disabled, the poor, and the unfortunate. In some coastal areas, she’s regarded as the savior of sailors and fishermen, and some have even modernized her to be the protector of airline travelers. In this role, she is very close to Mother Ancestor, and some blend the two goddesses.

No matter how soft, the broom wears down.

How can you sweep and yet be preserved?

If you use a broom for a while, the ends start to round and wear. Soon, the broom is no longer straight across the end: it’s shaped by the habit of the user. In time, it’s worn to a nub, and then it must be replaced.

One of the main tenets of Taoism is softness. Be soft, it is said, and your body will be preserved and you will live long. But no matter how much the bristles of the broom might flex, they are sacrificed in order to fulfill their purpose. Is the same true of us as well?

All of us must work, but work wears on us. The work may be necessary—certainly the work of the broom is needed—but no one escapes work without being worn out. In theory, monks left the world to avoid the entanglements and problems of an ordinary working life—but they still had to work in the temple.

There is only one way out: work must be devotional. Then the sacrifice is worth it. What we sweep is as important as how we sweep. We sweep to clear away. We sweep because we know that cleanliness is the prelude to the serenity needed for spiritual advancement. In the end, sweeping away the dead leaves and dirt of our bad habits and ignorance makes renewal possible.

With renewal, there is no wearing out.

How can you sweep and yet be preserved, knowing what the body is to the spirit?

Shide Holds a Broom and Talks to Hanshan and Fenggan

Shide (c. 9th century), whose name means “The Foundling,” was a Tang dynasty Buddhist poet who lived on Tiantaishan. He was a lay monk, worked most of his life in the Guoqing Temple, and is frequently depicted in Chinese and Japanese paintings holding a broom.

A number of paintings also show Shide with two older friends and fellow poets, Hanshan and Fenggan.

Hanshan (Cold Mountain) was an eccentric Buddhist hermit who lived on Cold Cliff in the Cold Mountains from which he took his name. The mountains were a day’s travel from Shide’s temple. Hanshan wrote a famous collection of poems, the Cold Mountain Poems, which have been extensively translated, and which show many Taoist influences.

Fenggan (Big Stick) also lived at Guoqing Temple. According to legend, he was a tall monk with an unshaven head (Buddhist monks traditionally shave their heads) who rode a tiger. He was probably the oldest of the trio.

The body is to the spirit—

what the earth is to heaven.

The body is the temple for the spirit, and it makes sense to keep our temple clean and pure. In every culture, we have made holy places so that the divine can enter into our lives.

Think about a temple, though. If you go to a temple and look in one corner or the other, you won’t see the spirit. If you take the building apart beam by beam and post by post, you won’t dismantle the spirit. If you burn down the temple, you won’t destroy the spirit. Those people who dissect the body looking for the spirit won’t ever find it, but it’s still here.

On the other hand, build a fine temple, consecrate it, and the spirit enters it immediately. Those people who say that we don’t need to respect holy places won’t ever find the holy, but it’s still here.

The spirit enters into this world through a body, and the body is the vessel for the spirit. The health and purity of the body have to be preserved, even as we understand that this bag of blood and bones, breath and tears, milk and semen, this body wired with a mind that can be crazed or sublime, this body is the temple for the spirit. Those people who say that the human can never be divine will never find the divine, but it’s still here.

Where is heaven? Is it far away? Out there? Up there? Heaven is here, with us, now. Just as the invisible spirit is rooted in the body, heaven is interwoven into this world. Those people who search for heaven outside of this world will never find it, but it’s still here.

How simple it is to be holy. We are in the temple already.

What the earth is to heaven, the journey is to Tao, and a journey of a thousand miles begins with . . .

Kaiguang

When a person takes a Taoist or Buddhist figure into their home for a personal altar, it has to be consecrated. This is called kaiguang—“opening the brightness.”

A temple priest will hold a ceremony and invite the deity to empower the statue, filling a material proxy with divine presence. The statue is then considered “alive” with the power of the deity. A personal god, once consecrated, is carried like a living person and placed in a position of honor on an altar.

Consecrating a Temple

Consecrating a temple is even more elaborate. The site has to be properly chosen according to geomancy; a qualified priest has to preside over the rituals; statues, scriptures, altars, and all the implements of worship must be installed; and perhaps there will be other holy relics to be venerated. Hours of ceremony are involved, and the rituals must be precisely timed to the cycles of the sun, moon, and seasons. Taoists will then consecrate every statue in the temple. Thereafter, it’s believed that the gods themselves occupy their images.

During the consecration process, various materials to empower the statues are prepared.

The materials are blessed and bundled in red cloth before they are sealed inside the statues.

The Three Pure Ones remain covered with cloth before consecration. Xianling Guan, near Wuhan.

© Photos by Saskia Dab

A journey of a thousand miles begins with . . .

After a thousand miles, we find ourselves in . . .

Tao means the Way. That seems simple enough. Everything in the universe follows a way, and our lives will be smooth if we follow that way too.

A way implies a direction, and a direction implies a goal. There is direction to the universe—the sum of countless complex and constantly changing smaller directions—but the universe isn’t traveling linearly toward some destination. The universe is starting point and destination in one. Nevertheless, within its expanse, there is movement, and hence, there is a way.

Taoism means to follow Tao. Following Tao means that one can find direction but not necessarily a final destination. That would mean an ending; Tao is unending.

We speak of a personal Tao, and it’s tempting to think of our lives as having a goal and direction. This isn’t ultimately helpful either. Is the “goal” of our lives old age and death?

We must look beyond the limitations of our own small lives toward the infinity that surrounds us. The scale of what holds us is difficult to imagine. The life span of a redwood, the expanse of our planet, the age of our sun, the sheer distances to other stars: all these are immense in scale.

Shall we think of ourselves as dwarfed by such magnitude? Should we speak of our life span as the goal and the ending of our way? No, we are of the Way, and the Way is us, and the Way continues unendingly. We too go on forever—if we aren’t stunted by the smallness of our own thinking.

After a thousand miles, we find ourselves in a place of power: great energy makes action possible.

Tao: Dao

The word Tao (dao) is a picture of a person on a path. The “v” shape on the right side represents two tufts of hair, and the rectangle with the two parallel lines inside indicates a face. The zigzag shape on the left that extends into a long stroke at the bottom represents the movement of feet.

The word is used by Taoists, Confucians, and Buddhists, but with slightly different meanings.

• Taoists use Tao to mean the great cosmic way, the movement of the universe as a whole, one’s personal life path, and the way of living that is right for each person.

• Confucians use Tao to mean the law and a proper way of living that is moral, ethical, socially responsible, and cultivated.

• Buddhists use Tao to refer to the principles and law (dharma) of the Buddha.

Great energy makes action possible,

and intention makes action effective.

Taoists have extensively studied human energy, which is called qi. The word “qi” nominally means our breath, but it also means our life force, the basic energy for movement.

Furthermore, Taoists (and martial arts derived from Taoist theories, such as Taijiquan, Baguazhang, and Xingyiquan) teach that our energy follows our intention. On the most exaggerated levels, this leads to colorful tales of superhuman feats by mysterious heroes who spend a lot of time meditating to generate extraordinary energy. The legend is that people with accomplished attention command unusual power.

This sensationalism overshadows a truth we can use in our daily lives: our energy flows towards our focus. The more we focus, the more constantly our energy flows. The more we safeguard and build our energy, the more energy we have at our disposal. And when we put our energy and our intention into synchronization, the more we are capable of great accomplishments. The more we establish patterns of activity, the more our bodies and minds conform to those patterns: we become what we do the most.

Taoists know this. There is no mind-body separation for a Taoist. Mind and body go together, and when they do, then the legendary abilities of a Taoist become ordinary.

Taoists connect the spiritual with the physical. Since jing becomes qi and qi becomes shen, all our different kinds of energy flow into one another and support one another. Mencius connects this three-part process to the will, to morality, and to the universe as a whole. Great intention requires great energy; great energy supports great intention.

And intention makes action effective, even if you fly to the edges of the universe.

• Fasting day

Mencius on Qi

The philosopher Mencius (Mengzi, 372–289 BCE) was a key interpreter of Confucian thought (some accounts state that he was tutored by Confucius’s grandson). Like Confucius, he traveled throughout China in a long and mostly fruitless attempt to advise rulers on better governance.

Mencius asserted that human nature was innately good. Like other Chinese philosophers, he felt that moral character was connected to natural truths and even physical phenomena. Thus, he articulated a view of qi (breath, energy) and its intimate relationship to the will, to morality, and to heaven and earth. Among his points:

• The will is the general of the qi, and the qi is the fullness of the body . . .

• When the will is concentrated, it moves the qi. When the qi is concentrated, it moves the will.

• He said: “I carefully tend my surging qi . . . Like all qi, it is great and firm. It is tended by rectitude and cannot be harmed, yet it fills all within heaven and earth.”

The character for “qi” is taken from vapor rising from rice (the cross at the bottom with the slanted lines in each quadrant represents rice). Qi means gas; air; smell; weather; vital breath; get angry; to be enraged.

Jing, Qi, Shen

Taoists are explicit in connecting the physical to the spiritual. Jing (essence, vitality), the basic strength of the body including all its chemical functioning, is transformed into qi (breath, energy). Qi is transformed into shen (spirit). Thus, for Taoists, there is no spirituality without physical health—and vice versa.

Fly to the edges of the universe

and then you can only fly back.

No matter how far our journey goes, we must turn back home at some point. No matter how magnificent our energy, it will reach a point where it can go no farther. The surface of the earth is infinite anywhere along the two dimensions of its surface, and yet it cannot jump even one millimeter into the sky. The sun is mighty enough to drive all life on our planet, and yet it cannot outshine even the star beside it. All things have their limit, and when limits are reached, there must be return.

We live in a time where people mouth the grotesque exhortation to “go beyond our limits.” Our athletes speak weekly about how they broke a record, achieved a personal best, found a way to wrest triumph from bleak defeat. A season later, the athletes have retired. What was once transcendence has to be accepted as limitation.

Without a doubt, we should not accept our limitations—especially the ones that exist because of ignorance, laziness, and indifference. These attitudes must always be challenged. But in the daily struggle to do better and to learn more, we have to be wise about what we choose to do. A globetrotter circumnavigating this globe can go on endlessly. But if he seeks to leap into the stars, he will not be able to do it. We must consider what’s possible as a prelude to challenging ourselves.

Confront your limitations. Be better today than you were yesterday. Learn something new each day. Discard a fault each day. All these things are good. But understand what you cannot do, too.

It is from this very limitation that the limitlessness of creativity springs.

And then you can only fly back, accepting that this is a life of poverty.

• Fasting day

Wuji, Taiji, and Yin and Yang

Wuji, Taiji, and yin and yang are key cosmological principles in Taoism.

Wuji means to be “without limit.” This means all infinity and comprises all that we know and cannot know.

Taiji means the “ultimate limit.” This means all that is known or knowable and includes all of heaven, earth, and humanity.

Yin and yang are the duality that make up Taiji. All energies and substances can be understood in terms of yin and yang.

The two graphics here are derived from the Diagram of the Supreme Ultimate (Taijitu shuo), written by Zhou Dunyi (1017–1073). The open circle represents Wuji. There are no limits, but because there are none, there is nothing to be distinguished.

Wuji transforms into Taiji—the Supreme Ultimate. Now things are distinguishable, and because there is differentiation, things can be understood through yin and yang. The lower diagram shows that yin and yang—represented by intermixed black and white—are subsets of Taiji.

Zhou’s diagram shows Taiji transforming into the Five Phases.

This is a life of poverty:

You must ask for riches to come.

It’s surprising how many requests are denied in the world. This begins in childhood. Parents must deny a child in order to be protective or to teach, but they must not deny a child simply out of tiredness or impatience. That can too easily progress to wrongful denials: the parent doesn’t know the answer, the parent is projecting his or her own negativity on the child, or the parent simply can’t envision fulfilling the request. No! No! No! A child hears that dozens of times a day.

In school, small-minded teachers and administrators continue this pattern. “There’s no budget.” “If I do this for you I have to do this for everyone else!” “What makes you think you’re so special?” “You just don’t have the grades.” It’s surprising that we aren’t all curled up, catatonic and drooling.

We have to keep getting up every day. We have to keep trying. We have to envision what we want, and we have to work for it. When we have an idea, however, the ghosts of those parents, relatives, and teachers reappear like a flock of filthy birds and chant: “Who do you think you are? What makes you think you’re so special?” We are defeated by these ghosts before we can take a step.

Ask. Open your mouth and ask. Yes! You are special! Yes, you will create something new! Yes! You are spiritual! It may take some time to realize this completely. But every time you ask, you deny those who denied you.

Every single moment of asking silences the noisy flock.

Every single moment of asking opens possibilities.

Every single moment of asking makes the vistas more clear.

You must ask for riches to come—after all, is there destiny, or is there none?

The Foolish Old Man Who Moved a Mountain

This fable originally appeared in Liezi, a Taoist text attributed to Lie Yukou of the fifth century BCE. The story is known in a number of contexts, from its abbreviation into an idiom to its use by Mao Zedong in a 1945 speech.

There was an old man of ninety who lived between the ocean and two seven-thousand-foot mountains. It vexed him that the peaks blocked his view, and that it took days to journey around them. He called his family together and proposed that they move the mountains.

His wife objected. “You are old and weak! Besides, where will you put all the dirt and stones?”

“In the sea.”

Together with his sons and grandsons, the old man began to break the stones, and everyone carried away the dirt and stones in baskets. A neighbor boy even joined them.

Another old man mocked them. “You are too old to even bend a blade of grass. What can you do with stones and dirt?”

The foolish old man said, “Your mind is too set for me to penetrate it. When I die, my sons will survive me. My sons will have sons and grandsons, and those generations will have sons and grandsons. My descendants will go on forever, but the mountains can grow no bigger. What difficulty should there be in removing them?”

The mountain spirits were afraid and reported this to heaven. The heavenly king was impressed and ordered the mountains magically moved away.

Is there destiny, or is there none?

How you answer determines your fate.

Destiny is a term in many classic writings, and it can be a charming attitude. “Oh, I was destined to meet you today.” Certainly many couples in love would like to believe that they were destined for one another. At the same time, plenty of people use predestination to explain their misfortunes, and they reconcile themselves to their lot in life by sighing that “it was just my fate.”

But can you say what will happen tomorrow? Can you say what will happen in ten years? Of all the world’s disasters and calamities in hurricanes, tsunamis, famines, genocides—not one has ever been accurately predicted. If these gigantic events cannot be detected, how can the minute events of one person’s life be preordained? Use your own sense. Why believe someone who wants you to accept a predestination that you can’t confirm?

What will happen on the last day of this year? You can’t answer that. Why? Because tomorrow, and the day after tomorrow, and every other day are created by the events of today. There is no predestination because the future is made by the present.

However, to some degree, we can set down plans that will act as if there is predestination. If you save money today, it is likely that you’ll have money tomorrow. If you invest in your education, it is likely that you’ll live with more awareness and perhaps even comfort and health. There is no predestination, because there is uncertainty. But we can consider probabilities, and we can influence them.

This road we travel is not there until we step on it, and with each step, the road stretches on, just ahead of our walking: it is our walking that makes the Way.

How you answer determines your fate; the riddle is that the universe moves—that is Tao.

Dream of the Red Chamber

Dream of the Red Chamber (Hong Lou Meng) is one of China’s major classical novels. Written by Cao Xueqin (c. 1715–1763), it is also known as the Story of the Stone (Shitou Ji).

The novel opens with a stone that has accidentally received consciousness. One day, a Buddhist monk and a Taoist priest happen upon it, and the stone begs to be sent into the “world of red dust” to enjoy the pleasures of earthly life.

The two holy men try to dissuade the stone, but it is insistent. The Buddhist monk transforms the stone into a piece of jade and takes it to earth.

“You shouldn’t have interfered with the destiny of the stone,” the Taoist says. “What are you going to do with it?”

“Don’t worry,” the monk replies. “The stone is involved in a drama that must be enacted on earth. I am not interfering with its fate—I am facilitating it.”

“So another group of spirits has brought the curse of incarnation upon themselves! Where did this drama originate, and where is it to be enacted?”

The universe moves—that is Tao.

All is change—movement in movement.

All of life is change. Nothing is static. On one side, one thing grows. On the other side, another thing dies, but nothing is ever lost: transformation after transformation marks every moment, and this dynamic process never ceases.

The same is true of us too. We may think, “It’s just the same old me,” even as we are astonished at a new gray hair, wonder about that wrinkle that wasn’t there yesterday, or worry about the needle on the scale trembling beside a higher number.

The more subtle and more challenging view is that every part of us is changing—from the cellular level to our thoughts—that inexorable change surrounds us as ocean currents surround a fish. Nothing is static. Everything is movement. That’s why the essential task of being a Taoist is to understand how all things—including ourselves—are in constant motion. It is possible to be aware of this. It is necessary.

Great freedom follows this understanding. Since nothing is fixed, we are not condemned to being a certain way. We have hope. When we are up against the seemingly intractable realities of our lives, we know change is not only possible, it’s inherent.

All we need to do is reach out to influence and direct that process of change.

All is change—movement in movement—so why do we learn that stillness is meditation?

These passages about change are from the “Great Commentary,” an appendix to the I Ching.

Images are perfected in heaven, forms are perfected on earth. Thus, change and transformation may be seen. . . .

Of change and its implementation, none is greater than the four seasons. . . .

Movement and stillness are constant . . .

Zhuangzi says:

Spring and summer come first and autumn and winter follow. This is the sequence of the four seasons. The ten thousand things are transformed . . . and pass through the stages of growth and decline . . .

We learn that stillness is meditation.

Still, meditation is constant movement.

The central training of Taoist endeavor is the daily practice upon which we build ourselves and our perceptions, binding together our own internal process of change in meditation. However, even while meditating daily for years, one must look beyond the classic teaching.

The classic teaching is this: Still yourself to perceive Tao. In the stillness of meditation, the ordinary chatter of one’s mind becomes calmed, and one can see one’s own inner nature.

And then what? That’s when the masters merrily tell us to try it, adding that to say more is interference.