Night Mooring at Maple Bridge

The moon sets, birds cry, and frost fills the sky.

River maples, fishing torches—can’t sleep.

From Cold Mountain Temple outside Gusu:

the midnight bell sounds to this traveler’s boat.

—Zhang Ji (d. 780)

Gusu was the ancient name for Suzhou.

The two solar terms within this moon:

SLIGHT COLD

GREAT COLD

the twenty-four solar terms

The year enters its period of greatest cold, and if low-temperature records are set, it’s commonly during this time.

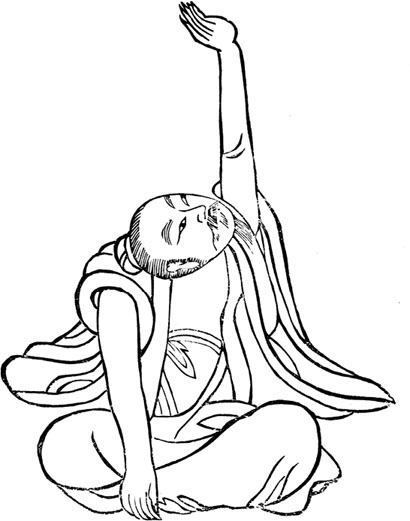

This exercise is best practiced during the period of 11:00 P.M.–3:00 A.M.

1. Sit cross-legged and raise one hand overhead, palm facing upward. Press the other palm on your foot.

2. Alternately change position, pushing upward with the raised hand, but with force, and press downward with the other hand. Inhale when you push; exhale when you change sides. Repeat fifteen times on each side.

3. Facing forward with your hands resting on your lap, click your teeth together thirty-six times. Roll your tongue between your teeth nine times in each direction. Form saliva in your mouth by pushing your cheeks in and out. When your mouth is filled with saliva, divide the liquid into three portions.

4. Inhale; then exhale, imagining your breath traveling to the dantian and then swallow one-third of the saliva, imagining that it travels to the dantian.

5. Repeat two more times until you’ve swallowed all three portions.

6. Sit comfortably as long as you like.

Through this exercise, ancient Taoists sought to prevent or treat blockages in the circulatory system; vomiting; stomach pains and abdominal distension; loss of appetite; sighing; feelings of heaviness; diarrhea; problems in urinating; and grief.

Why do all ships carry lifeboats?

We want to have another chance.

The answer to the lifeboat question seems obvious. However, sometimes the obvious can be overlooked, and sometimes discovering what we overlooked can tell us something important. Even the sailors who pray to Mother Ancestor carry lifeboats. They may worship the Mother, but they are prepared to save themselves. The sinking of a boat in a storm may be terrible, but we no longer ascribe it to devils and monsters. We know accidents happen, and we know accidents happen impersonally.

When a ship begins to sink, we go to the lifeboats. We have prepared, and we understand that there are no guarantees: our lifeboat could still be capsized, or we might not be rescued. But it’s necessary. Without it, we wouldn’t even get another chance. When the rescued sailor reaches land, thanks will be expressed, but being prepared was crucial.

What about each of us in the sea that is this lifetime? Do we have lifeboats? When our flesh-and-blood hull breaks apart for the last time, will there be a lifeboat and will there be a sailor in that boat?

Taoist alchemists wanted to make the Golden Embryo that would carry the human soul away from the body upon death. Other Taoists wanted to cross to the island of Penglai and thereby join other immortals. The Chan Buddhists and the philosophical Taoists would scoff: there is no ship, there is no lifeboat, there is no passenger, and there is no one to rescue and nothing to be rescued from.

What’s your answer? Whether you’re sailing to Penglai or whether you’re just trying to navigate the stormy events of ordinary life, must you have a lifeboat?

We want to have another chance, and we can: the word “Tao” can simply mean “road.”

• Fasting day

• Festival of the Eight Immortals Crossing to Penglai

The Eight Immortals Cross the Sea

This festival commemorates the story of the Eight Immortals as they cross the ocean to Penglai, the legendary island of immortals.

When the Eight Immortals arrive at the shore of the Eastern Sea, they find the waves turbulent. Lu Dongbin proposes that each immortal help cross the sea through his or her special skills. Li Tieguai throws his crutch; Han Zhongli tosses his palm-leaf fan; Zhang Guolao sends his paper donkey, and so on. In this way, all the immortals cross the sea.

This story lives on in a number of ways. First, Penglai City, Shandong, has a scenic area with gates, buildings, and sculptures based on this very legend. Second, a popular idiom, “The Eight Immortals cross the seas,” symbolizes overcoming difficulties or accomplishing marvelous feats using one’s own skills. Finally, the story has inspired a luxurious banquet dish featuring the eight ingredients of shark fin, sea cucumber, abalone, shrimp, fish bone, fish maw, asparagus, and ham. In this version of the story, there is a luohan as well, represented by adding chicken. The dish was often prepared for the families of Confucius, officials, scholars, and the emperor.

© andelieya

The word “Tao” can simply mean “road”—

as plain and yet profound as that.

If you know what the word “Tao” looks like, you might be startled to see it on the street signs in Chinese communities, where it simply means “road.” In that context, the term means nothing more. It’s not religious, it’s not a reference to history, and it’s certainly not meant to be poetic. So you could be walking down a road, carrying books in which “Tao” means the movement of the universe and the natural principle upon which all human law should be based while talking with a friend about a Taoist immortal, and then look up and see that you are on such-and-such a road. You could see the two meanings as strictly separate. In fact, literate people probably see the same word as so completely distinct in its meanings, they might strain to even put the two meanings together.

(Incidentally, this isn’t the only case like this. The first hexagram of the I Ching is named Qian—meaning “heaven” at its most profound. The same written word is pronounced differently—gan—in ordinary life, and so one might be startled to see the word on a package of dry biscuits.)

So to say that Tao is profound, yet ordinary, is wrong—and also right.

—to say that Tao is the movement of the universe is wrong—and also right.

—to say that Tao is the invisible is manifest right here in front of us is wrong—and also right.

—to say that Tao should be followed in our everyday life as unconsciously as we travel on roads is wrong

—and also right.

As plain and yet profound as that, do you laugh at the road up Cold Mountain?

Believable Words Are Not Beautiful

Laozi begins the Daodejing with an immediate play on words. The first three words can be read as “The Tao that can be spoken” because “Tao” has so many meanings: direction; way; road; path; principle; truth; morality; reason; skill; method; Dao (the central term of Taoism); to say; to speak; to talk; measure word for long, thin stretches, rivers, roads; province (of Korea and formerly Japan).

In Chapter 70, Laozi writes:

My words are very easy to understand and very easy to practice.

Yet no one under heaven can understand them or put them into practice.

Words have a lineage; all matters have their ruler.

Since people don’t understand, they don’t know me.

Those who understand me are few, those who follow me are rare.

That’s why the sage wears coarse cloth but holds jade.

Chapter 78 ends with the line: “Straight speech seems contradictory,” and in Chapter 81—the final chapter of the Daodejing—Laozi declares:

Believable words are not beautiful.

Beautiful words are not believable.

Do you laugh at the road up Cold Mountain?

Climb up to laugh over your own reasons.

Morning traffic, car horns honking. Riders shout for the bus to stop. Between parked cars, toes over the curb and shoulder to shoulder, two guys grin. One has a commuter mug in hand, the other holds a canvas bag. With bristle-urchin hair, they could be our modern Hanshan and Shide—drunk, even though it is early morning. Are they the silly ones, or is it the business of the streets that’s silly?

You will never know who they are, but they’ve already done their jobs if they’ve made you think about an alternative to the serious business of society. That’s what we need Hanshan for, to remind us that all our rushing to and fro on our well-planned streets is not the same path as his.

The road up Cold Mountain is not like our everyday thoroughfares. The way is twisted and too narrow for cart or horse. It’s barely a foot trail, passing through linked ravines that are turned back on themselves between cliffs that rise up like shadowy towers. Unlike our crowded streets, it is empty of other people. This is a place no one ever comes; it’s a place of recluses.

Seeking Tao is not for everyone. Perhaps that seems like madness in this world where “best-selling” seems like the only real measure. When people are celebrated for how many contacts they have in their address book, it’s a radical thing to walk a barely trodden path to a mountain where nobody else lives.

Yet in every generation, there will always be people who understand that the path leads to all that they truly want. With each step, everyday involvements grow more distant and the spiritual glows with increasing brightness.

You might laugh to look at the arduous path up Cold Mountain, but are you someone who wants to know why Hanshan grins?

Climb up to laugh over your own reasons—or do you sing a song the world’s heard?

Cold Mountain

Little is known about Hanshan (c. ninth century, whose name means Cold Mountain. He presumably took his name from the Hanyan Cliffs in Zhejiang, where he lived as a hermit. He is especially popular in Chan Buddhism, and is represented in paintings as a wild eccentric dressed in tatters and grinning crazily. However, his poems reveal a recluse who grappled fiercely with the ardors of spiritual life, and they attest to his individualistic response.

The title of this poem, “You Might Laugh at the Road Up Cold Mountain,” can also be read as “Laughable Cold Mountain Road.” Here, Hanshan uses the word “Tao” for “road.”

You might laugh at the road up Cold Mountain,

no track for cart or horse.

Ravines after ravines, it’s hard to remember all the turns.

Cliff upon cliff rises as if weightless.

Dew weeps from a thousand kinds of grass.

Sighing winds always in the pines.

For a time, I’m so confused by such a mysterious maze

that I ask my shadow which way to go.

Do you sing a song the world’s heard?

Or do you sing a song few know?

We admire the singers with best-selling recordings, who play in stadiums to fifty thousand people or more at a time. We want to know who has a hit, how many times the song has been recorded by others, how emotional it makes everyone in a generation. We laud the chart toppers, looking with pity at the “where are they now” programs. We search for the video that has the most hits. We watch television shows where people compete to be the best singers, and we reward the winner with what can be a lifelong career.

Taoism is the inverse of that. There are few people interested, it is hard to fathom and to quote, and no one competes to be a Taoist. It’s practically secret knowledge, not because adherents want to hide it but only because Taoism is fundamentally anti-conformist, individualistic, and oriented toward the patterns of nature over the patterns of society. The song of Taoism is not the song of society.

Will you be that kind of person who does not follow others? Will you sing the song that few people know, a song that cannot be packaged and sold to others?

The song of Tao is the song of the universe. If you are to sing its song, you must hear it first.

If you would hear that song, you must turn away from the crowd. For the song is powerful, but subtle, easily obscured by the raucous shouts of commerce, the siren drone of people trying to seduce one another, the endless prattling of millions offering their self-confessions, the devilish xenophobia of demagogues, and the endless sentences pouring from bad journalists and poor poets alike. If you want to hear the song few know, you must first withdraw into silence. Only when you are deeply familiar with silence can you hear the song of Tao.

Or do you sing a song few know, understanding why serenity will be found in the world?

A Lofty Song with Few Singers

Song Yu of Chu (third century BCE) was a scholar and may have written some of the poems in the Songs of Chu. One day, King Xiangwang (232–202 BCE) summoned him and said, “Your conduct is quite reproachable, and people are whispering about you.”

“That may be,” Song Yu conceded. “But I ask your majesty to hear me out before condemning me. A few days ago, I saw someone singing in the street. He first sang a folk song called ‘Song of the Rustic Poor.’ Several thousand people joined in. Then he sang a more sophisticated song, ‘Song of the Spring Snow.’ Less than a hundred people joined in. Finally, he sang the most unusual and sophisticated of songs, and only a half dozen people could sing with him.

“This shows that the more unusual the song, the fewer people know it. Therefore, how can the average person understand what I do?”

This incident is remembered in an idiom, “A lofty song with few singers.”

Serenity will be found in the world.

It can’t be found by negating the world.

There are plenty of problems in the world. Getting a perspective on them and finding a way to feel Tao requires periods of peace and silence. But it doesn’t follow that we should reject and negate the world.

Even the mountain sage lives in a cave. Even the greatest monastery still has brick walls and is built on the ground. When we hear that worldly entanglements impede us from finding Tao, it’s easy to assume that merely abandoning worldly entanglements will immediately reveal Tao.

Unfortunately, it’s not that easy.

We cannot divorce ourselves from this world. No matter what, we still have to walk on this ground, breathe the air, drink the water, and eat the food harvested from this earth. Denying ourselves air, water, and food and not providing a livelihood for ourselves will not make us holy. True, Buddha went through a time of living in the forest as he sought enlightenment, but as the story of the upcoming Laba Festival shows, even he needed food and drink.

Su Manshu had an odd and unusual life. He certainly tried to make his way as a worldly person, and he obviously struggled with the monastic lifestyle. If he wrote the poem “Staying at White Cloud Hermitage” because he was there, then he had to have traveled to reach it from his home province. Traveling means that one is not above this world. One is literally traveling through the world to arrive at a destination still on this earth.

Once there, though, he sank into meditation. In the same way, we have to take the time to meditate even as we establish and maintain a worldly life. Serenity is essential. But it can never be found by denying the world.

Where in the world can you go that is not still of this world? Thus serenity must be found in this world.

It can’t be found by negating the world, and Tao does not require a special person.

The Bell over the Monastery’s Deep Pool

Su Manshu (1884–1918) was a writer, poet, painter, revolutionist, and translator. He was the son of a Cantonese merchant and a Japanese woman. Born in Yokohama, Japan, he returned to China when he was five years old. As a student, he was a revolutionary opposing the fading imperial government, then went on to become a journalist. Eventually, he abruptly left all worldly activities and became a Buddhist monk. Despite his vows, he feasted often in the company of singing girls, although he reportedly remained celibate. He suffered from illness and poverty until his death.

This poem, “Staying at White Cloud Hermitage,” places him in a Chan Buddhist monastery in Hangzhou. The Thunder Peak Pagoda mentioned is the famous site of the legend of Lady White Snake.

White clouds surround Thunder Peak Pagoda.

A few trees of winter plum girdle the snow with red.

In a screened study, I sink, sink into meditation

as the bell sounds over the monastery’s deep pool.

Tao does not require a special person.

How could that be? Everyone has a soul.

There have been masters in the past who declared that spirituality was only for the qualified. Perhaps you had to have been someone extraordinary in a past life. Perhaps you had to be beautiful, or to have talent, or to be extremely learned. Certainly, if you look at the example of the luohans, each one with his special powers, you might be tempted to think that you have to be someone unusual to be holy. But what kind of doctrine is that?

We already live in a society of hideous discrimination. The beautiful, rich, talented, powerful, and ambitious try to raise themselves over everyone else. Clubs are selective in whom they admit. Corporations only want the best employees. Schools reject any student below lofty admissions standards. Then there are the more subtle kinds of selectivity—when you’re not striking enough, or funny enough, or well connected enough to be of interest to others. In every one of these cases, you’re rejected because you don’t offer something to be exploited. So as painful as it is, understand that your rejection means that you’ve escaped being cannon fodder for other people’s greed.

The pursuit of Tao must be open to everyone. It must not require that you be a special person. Tao must be plain and ordinary, something anyone can gain access to, something that anyone can embrace.

Isn’t that true of all the really valuable things in life? The air, the sky, water, a place to live—these are fundamental and you don’t have to have any special quality to receive them. They are part of your birthright. Tao is just like that—as open to you as the air you breathe. In fact, perhaps that’s why breathing exercises like qigong are one beginning approach to Tao. It’s that plain and ordinary.

Tao is open to everyone because everyone has a soul. If you were able to pull out dozens of souls and line them up, you could not see anything different about them. There are no “pretty” souls and no “rich” souls. There are only souls. Everyone has a soul. Thus, the way to that soul is open to everyone.

How could that be? Everyone has a soul. There is no chosen one, no chosen race.

One’s Spirit Is Pure, Clean, and Simple

Zhuangzi describes the pure, clean, and simple soul of a sage in this way:

The life of a sage moves like heaven. Death is like the transformation that all things undergo. Calm, yin qualities are at one with virtue. In action, one’s yang qualities are like waves. One need not strive to be happy. One need not struggle solely to avoid calamity.

One responds as seems necessary, and moves when force seems to compel it. One need not strive to get what will come later by itself.

Wherever one goes, the cause can be known—one only wishes to conform to heaven’s law. Then there will be no calamity from heaven, no entanglements from other things, no blame from others, and no reproach from ghosts.

One’s life is like floating, death is like resting. There is nothing to think about, no reason to worry, no facile scheming. One is bright, but not flashy, truthful without end, sleeps without dreaming, and awakens without melancholy. One’s spirt is pure, clean, simple, and one’s soul does not tire. Open, tranquil, yet cheerful, one will be united with the virtue of heaven.

There is no chosen one, no chosen race.

Who would do such choosing when all are one?

There is no chosen one, no special person that the gods have raised above all others. How outrageous that would be.

Some have asserted that there is a chosen race—usually meaning that they, their families, and their friends are in the chosen race and that everyone else is not.

Honestly: look at everyone in this world. Can anyone truly say that one person is “better” than the next, or that someone is worth really following as if he or she is divine? There is no such person, and there never will be. There will never be a chosen race, because all humans are of one race. There will never be anyone chosen, because there’s no divine authority to do the choosing. Like it or not, we are all on this earth, equals, with no person having a cosmic advantage over the others. True, we may choose leaders whom we regard as wiser or more skilled, but they are human beings, struggling with the same life as everyone else, aging like everyone else, and heading toward death like everyone else.

Really, this is a cheerful and reassuring thought. Society may have created and sanctioned hierarchies and pecking orders and there may be ranking in Taoism, Buddhism, and Confucianism, but there cannot be any ranking on a spiritual level. Once you strip away the body and the history, there is still the soul, and the soul of one person is no more superior than the soul of the next.

Every culture implicitly believes this, because everyone’s account of the soul is freedom from the bounds and troubles of this world—and that includes rank. Who knows where people are going after they die? But they are not going to some deity who’s going to choose them over others and who is going to sequester them in a divine realm where they can sneer at others for eternity.

Who would do such choosing when all are one? When we offer what we receive?

The Hunchback of Shu

Zhuangzi tells the story of the hunchback of Shu. His chin was in his navel, his shoulders rose over his head, the vertebrae of his neck pointed at the sky, his five viscera were crammed into the upper part of his body, and his thighs seemed to emerge from his ribs.

By sewing and washing clothes he earned just enough to afford porridge. By winnowing and sifting grain, he was able to feed ten other people.

When the government called for soldiers, he came and went without having to hide. When great public works were undertaken, none of the work was assigned to him because he was an invalid. When the government distributed grain to the sick, he received triple portions along with ten bundles of firewood.

If such a poor man with a strange body was able to support himself and complete his natural life, how much easier it should be for others with all their faculties!

Year-End Sacrifice on the Eighth Day, or the Laba Festival (Laba Jie), is a vestige of an old day of offering. La means “the year-end sacrifice” and “the twelfth moon.” Ba means “eight” and is a reference to the eighth day of the twelfth moon. The festival is also known as the Laji Festival, meaning the end-of-the-year festival. It originated more than three thousand years ago as a sacrificial ceremony in which the game captured during great hunts was offered to ancestors and gods.

By the Song dynasty (960–1279), Laba had also become an occasion for farmers to express their gratitude for good crops. Especially when the harvests had been good, the farmers showed their appreciation by making sacrifices to heaven and earth. In time, the Laba Festival’s main culinary symbol became Laba porridge.

Laba porridge consists of glutinous rice simmered with sugar for one hour and a half, with additional ingredients such as red beans, millet, sorghum, peas, dried lotus seeds, dried dates, mung beans, jujubes, peanuts, chestnuts, walnuts, almonds, or lotus seeds. In the north, Laba porridge is a sweet dish, but in the south it is a savory dish with soybeans, peanuts, broad beans, taro, water chestnuts, walnuts, vegetables, and diced meats. People tend to select eight ingredients to add to the rice and sugar, probably as a reference to the eight of Laba, and also because eight is considered a lucky number.

There are two traditional explanations for the origins of Laba porridge.

The first story recounts a poor peasant boy who eventually became the Ming Emperor Zhu Yuanzhang (1328–1398). While he was herding cattle, one of the cows broke its leg. His employers punished Zhu by starving him. Hungry, he found a rat hole, dug out the beans he found there, and boiled them in porridge to create a delicious dish. After he became emperor, he missed the taste of this simple food and asked for it to be prepared for him. He also ordered the porridge cooked with a mixture of several grains and sugar to feed hungry citizens, and the recipe eventually passed from the palace to the populace. Zhu Yuanzhang also features in the story of mooncakes.

The second story recalls Sakyamuni Buddha’s attainment of enlightenment on the eighth day of the twelfth moon. Sakyamuni meditated so deeply and practiced such extreme asceticism that he was close to dying of starvation. A girl named Sujata saved his life by feeding him rice porridge and milk, enabling him to continue meditating and to attain enlightenment on the day of the Laba Festival. Thus, the eating of porridge on this day commemorates Buddha’s breakthrough, and the festival is also known as the Day of Enlightenment.

In ancient China, before the advent of refrigeration and especially in the north, the cold winters meant that much of the food could be stored in coolers without spoilage. Pickled garlic and cabbage were also popular in the north.

With the cold weather, hearty and warming dishes like porridge are great comfort foods. Another popular dish is Laba soup noodles, made with eight different shredded ingredients. Hot rice wine makes the perfect accompaniment to both dishes.

Soaking of Laba garlic is a custom associated with this festival. Garlic is soaked in vinegar for twenty days beginning on the day of the festival. The garlic and vinegar are served alongside the dumplings (jiaozi) for Chinese New Year.

Rice Porridge

Also known as congee (a word adopted from the Tamil kanci) or baizhou (white rice porridge), rice porridge is also served outside of the Laba Festival as a common breakfast dish. Its base is simple to make, with a handful of rice cooked in a pot of water yielding a dish that can feed many. Rice porridge is therefore served frequently in monasteries, where a little has to be stretched among many, and it was also used to help feed the hungry in times of famine.

Bonchan/Shutterstock

Even this simple usage has added to the lore of rice porridge. According to one legend, Emperor Yongzheng (1678–1735) of the Qing dynasty ordered rice porridge distributed to the starving people during a famine. The corrupt officials distributed only a watery gruel, which displeased the emperor. From that day forward, he decreed that rice porridge must be thick enough so that a pair of chopsticks would stay upright when inserted into a bowl of porridge. That should give some idea of the proper consistency of the porridge (it is also the only time that chopsticks can be stuck in a bowl, since this is considered a rude thing to do at the table).

Rice porridge is also a therapeutic dish because it is easy to digest, hydrates the patient, and can be customized with different foods to combat the illness. In the Compendium of Materia Medica (Bencao Gangmu), the Ming dynasty physician Li Shizhen (1518–1593) stated that rice porridge “increases the life force, produces saliva, nourishes the spleen and stomach, and resolves sweating due to a weak constitution.”

We offer what we receive

to be worthy to receive more.

What does it mean to sacrifice today? Without falling into primitive superstition, is there a place for it?

The desire to sacrifice is a real emotion. It is a true and genuine expression. When we feel reverent, when we feel humbled by our experiences, when we feel that we have received more than we deserved, when we feel that the extraordinary has happened to us, when we are grateful for our lives, then we naturally want to make an offering. This has nothing to do with movie images of savages throwing a virgin into a volcano. What we’re referring to begins within, with sacrifice being the only way to express how we feel.

However, ruining something we love or hurting ourselves to appeal to the unseen is unnecessary and akin to guilt and self-destruction. We can move beyond that. We don’t hurt what we have to express ourselves properly. Rather, true sacrifice is an expression of unselfishness.

The earliest participants in the Laba Festival were grateful for their hunt and so wanted to share their success with the gods. It’s as if they were saying, “We are grateful that we were able to catch game to feed our community. You, the gods, made this possible, so we would like to give you some of what we have in return.”

Sacrifice is a real expression. In order to discern it clearly and to keep it from degenerating into superstition or selfish quid pro quo, we need to make sure our sacrifice conforms to these standards: it’s unselfish, it’s an act of sharing, and it’s a gift. As long as sacrifice has these qualities, it’s a positive and perfect way to be devoted and reverent.

Beating drums on this day means that the spring has set in and grass will grow again: of course spring is already approaching. Of course the grass will come again. It’s our attitude that makes all the difference.

To be worthy to receive more, ask: which one do you prefer?

• Fasting day

• The Laba Festival

In the Time of Slight Cold, Spring Is Already on Its Way

Zong Lin (c. sixth century) wrote about festivals in a book entitled Festivals and Seasonal Customs of Jingchu (Jingchu Shuishi Ji): “The eighth day of the twelfth moon is the day of the year-end sacrifice. There is a saying: Beating drums on the day of the year-end sacrifice means that spring has set in and grass will grow again.”

Accordingly, villagers paraded with drums and wore masks as the Buddha or other deities to celebrate and to chase away pestilence, bad luck, and devils.

© Saskia Dab

Which one do you prefer?

Society or Tao?

Taoism might not exist in its present form were it not for the tremendous social pressures Confucianism caused. The Confucian emphasis on the rites was unmitigated, the demand for conformity—reinforced on a daily basis by familial and peer pressure and on a grand level by absolute imperial rule—was unrelenting, and the system of great advancement solely through the examinations and the scholar-official life was unforgiving. There almost needed to be Taoism to relieve the strictness of Confucianism.

Taoism advocated a carefree life, a life of nonconformity, an appeal to nature as the ultimate authority beyond any emperor. It was the life prizing joyous mysticism over solemn duty. Therefore, Taoism was the particular favorite of those who were already inclined to follow impulses beyond society. Artists, poets, musicians, mystics, alchemists, herbalists, recluses, and seekers of all types took refuge in Taoism because it offered a way out of the immense pressures of the sanctioned social life. The conflict between Han Xiangzi and Han Yu symbolizes the tug between two polarities that people experienced in the past. Even today, many face the question of whether to fulfill the expectations of their parents and society or live lives of nonconformity. Thousands of years of Taoists show that there is a life there, with rewards every bit as rich as the gold and the titles that the Confucianists pursued.

Han Xiangzi plays the flute. He is carefree. He communes with nature, as the leopard represents. The gourd by his side can pour wine to fill every cup in a banquet hall, or it can dispense the elixir of immortality. If you listen, you can still hear his fascinating melody. He’s beckoning you down a path, and as you walk it, your steps will fall in time to the clicks of his castanets. If you choose the path of the nephew over that of the uncle, you will find friends, beautiful vistas, and travel in the clouds.

Society or Tao? Whatever you do: know.

• Birthday of Han Xiangzi

• Begin preparation for end of the year

Han Xiangzi

Han Xiangzi was born during the Tang dynasty (618–907). He is one of the Eight Immortals and a student of Lu Dongbin. He is shown holding a flute, a pair of castanets, or sometimes a small crucible as a reminder of his skill as an alchemist. A peach tree in the background of some depictions is a reference to his falling from such a tree, killing his body but beginning his immortal life. He is identified closely with his uncle, the scholar Han Yu.

At a banquet that Han Yu hosted, Han Xiangzi urged his uncle to give up the life of a scholar-official to study Taoism. But Han Yu insisted that Han Xiangzi should dedicate his life to being a Confucian official instead. Han Xiangzi responded by filling every wine cup from a small gourd without it ever running dry. He then sprayed water into a clay bowl filled with soil: a bud sprang up immediately and continued growing until there was a peony tree in full bloom.

Whatever you do, know

when enough is enough.

Enough. It’s really a marvelous concept. Know when enough is enough. As the year comes to an end, it’s a reminder that all things have their endings and their limits. At other times, endings and limits are frustrating. “Enough” means that endings and limits can also be positive. You’ve done enough.

Whether this past year was good or bad—and chances are it was a little of both—it’s coming to an end and you’ve done all that you can. Now it’s time to begin cleaning up, clearing out the excess, and getting ready for a new time. The custom of cleaning up because it clears away “bad luck” is true in this sense: once a time period has passed, it’s best to do away with all the leftovers that will encumber your future. No baggage. No dead weight. Get rid of it so you can move on as freely as you can.

In this sense, wuwei, or “not-doing,” has additional meanings: do just enough. Do no more than necessary. Act without extra ramifications. And when you’re finished, really be finished, with no lingering regrets, no sloppy excess, no reason for matters to come back again uglier and messier. This is why Laozi says that we should know when enough is enough, and that if we do, we will still have sufficiency. There is nothing to fear, because when you know enough is enough, then you also know that you have enough.

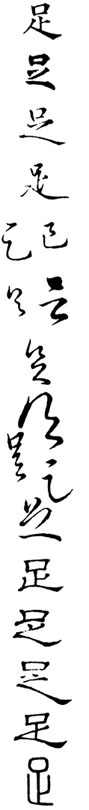

The word “zu,” “enough,” is a picture of a leg and ankle. The illustration shows some of the many ways to write “zu” (showing a different kind of “enough!”).Sit down and rest. Then, when it’s time to walk the road again, you’ll be renewed and hopeful.

When enough is enough, the constant present is so vast.

Enough Is Enough

Chapter 46 of the Daodejing concludes with the declaration: “Therefore know when enough is enough, that will always be sufficient.” Laozi uses zu, which shows a leg and foot—meaning “enough, sufficient, ample.”

Beginning of Housecleaning

From the end of the Laba Festival to the day before New Year’s Eve, people clean their homes thoroughly. This is supposed to dispel ghosts and bad luck, prepare the Kitchen God for his journey back to heaven, and ready the home for the new year. Every part of the house is cleaned and washed, and the couplets and decorations from the old year are taken down. Fresh couplets and decorations for the new year are put up. The altar is cleaned, and new offerings are made.

All necessary provisions are bought and stored. Some businesses will close for the first two weeks of the new lunar year, so people don’t want to be caught short of supplies. The heads of families prepare a number of large meals during the Spring Festival, so it’s important to have plenty on hand. Children get new clothes and receive firecrackers to drive away evil spirits.

Although it’s traditional to begin preparation following the Laba Festival, there are still thirteen days until efforts begin in earnest. The signal for these efforts is the sending off of the Kitchen God on the twenty-third day. A popular saying gives the basic schedule: “Eat sticky candy on the twenty-third; sweep the house clean on the twenty-fourth; fry tofu on the twenty-fifth; stew mutton on the twenty-sixth; kill a rooster on the twenty-seventh; set dough to rise on the twenty-eighth; steam bread (mantou) on the twenty-ninth; stay up all night on New Year’s Eve; pay holiday visits on New Year’s Day.”

The constant present is so vast

that it straddles past and future.

Green Ram Palace (Qingyang Gong) stands in the western portion of Chengdu, Sichuan, and is the oldest and largest Taoist temple in southwest China. Originally built in the early Tang dynasty (618–907), the temple has been restored many times; the current buildings dates from the Qing dynasty (1644–1911).

According to legend, Qingyang Gong marks Laozi’s birthplace and the location of his first discourse on Taoism. This is hard to confirm, since Laozi lived at least 1,200 years earlier. It’s a mystery that can probably never be fully addressed. Laozi would probably be delighted. “The Tao that can be told is not the constant Tao.” We can never arrive at anything completely through words, and this applies to niceties like birthplaces and first sermons.

Laozi is gone. Lu You is also gone. Tang Wang is gone. And the Taoist of Green Ram Palace with whom Lu You spent a pleasant day is also gone. If we go to Green Ram Palace in Chengdu, we can’t really say that we are going back to Lu You’s time, and we certainly can’t say that we can even trace our feelings back to Laozi’s time. We go for ourselves.

There is past, present, and future. What’s important is that we live in all three. Conventional wisdom would have us live in the “here and now,” and we praise someone who can exist in the “eternal present.” This is not a negation of that, but is a different view of what the present means. We can live in a present that activates the past and the future.

We look back at people who have been dead thousands of years because they show us the very roots of human experience, revealing what is archetypal and therefore true on a deeper level than what we might experience today. Taoists are clever not because they depend on fate but because they formulate strategies so thoroughly that the future takes place as if preordained.

If we go to Green Ram Palace, we go in the eternal present to embrace the past and the future. Then we will know the free and easy simple life that Lu You went to find.

That it straddles past and future may be, and yet the mountain pine may be wind-pruned.

The Poet Lu You

Lu You (1125–1209) was a prominent Song dynasty poet. At the time of his birth, northern China had been invaded by the Tartar Jin dynasty, forcing the native Chinese government to continue as the Southern Song. The dynasty fought during Lu’s entire life against the Jin, and Lu is known as one of China’s most patriotic poets.

His love life was tragic. He married his cousin, Tang Wang, when he was twenty. However, his mother did not like his wife and forced them to divorce. Lu You, obligated to obey his mother, reluctantly complied. Eventually, each remarried.

Eight years later, he chanced upon Tang and her husband in Shen’s Garden. She asked her new husband to send wine and food to Lu, and when she offered a cup of wine to him, Lu saw tears in her eyes. Draining the cup, he turned away and wrote his famous poem “Phoenix Hairpin” on a wall with the clear rant, “Wrong! Wrong! Wrong!”

Tang Wang later read the poem, wrote one of her own in response, and died less than a year later. A year before his own death at eighty-five, Lou wrote a poem called “Shen’s Garden,” commemorating his first love. Their tragic story became so famous that it was made into an opera.

This poem, “Sharing a Drink with the Taoist of Qingyang Gong,” speaks of Lu’s attraction to Taoism.

The Taoist of Qingyang lives among bamboo

and plants flowers like those of Xuandu Retreat.

When the light rain clears, he sees the dancing cranes.

Through a small, dim window, he hears the bees hum.

The fire of his alchemy stove glimmers and glows warmly.

Drunkenly, his sleeves flutter in the wind at a slant.

Though old, this official is really free and easy,

and has come to share a simple life.

The mountain pine may be wind-pruned,

but it stays an unaltered pine.

The pine stands on the mountainside. It does not need a grove to survive. It may be assaulted by rain, snow, wind, and harsh sunlight, but it endures. Where rock splits from the baking afternoons of summer or the ice wedges of winter, the pine maintains its heart and living bark.

The maple may shed its leaves in winter, withdrawing into itself. The pine maintains its needles, even under the weight of snow.

However, what old pine retains all its branches for its entire life? When the Classic of Rites says “without altering their branches,” it means that the pine doesn’t do anything to change itself. It is true to its character, and so it has “extreme greatness under heaven.” However, the pine does not escape danger. It is battered by storms and can be burned by lightning and fire.

The ancient pines on barren mountainsides all show the scars of branches sheared away, or trunks and bark roughly split. Yet the pine lives. It finds a way to heal. It continues to stand. It remains evergreen.

But it stays an unaltered pine, even when the arrow strikes the sphere’s center.

The Pine

The pine is the symbol of long life and hardiness. It’s especially admired because it doesn’t drop its leaves in the winter, and because it lives a long time.

Pines and cypresses are planted around graves not only because their evergreen branches are a comfort all year long, but because they are believed to repel the wangxiang, legendary creatures that eat the brains of the dead. Pines and cypresses are also the symbol of friends who stand together through hardship.

The Classic of Rites compares a person’s character to the pine and cypress:

. . . the pine or cypress have hearts. Both have extreme greatness under heaven. They can go through the four seasons without altering their branches or changing their leaves.

This is how noble persons behave with propriety, harmonizing with outsiders and having no conflict with anyone in their inner circles. When there is never a lack of benevolence for all, then even ghosts and spirits acknowledge such virtue.

The arrow strikes the sphere’s center,

but what is pierced remains empty.

There are many orthodox ways to think of being centered. There are many ordinary ways to invoke balance in our lives. Thinking more about the word “zhong” can take us to another level of understanding.

Imagine a brass sphere high on a pole. Warriors on horseback compete to show their skills. Each one draws back an arrow and shoots at the target. The one who pierces the target perfectly through its center wins the highest rank.

Our spiritual practice can be compared to that. In aiming for the truth, we try to get right to the heart of the matter, and success is greatest when our perception is most on target. But the target remains hollow—and is not even the prize itself.

If we hit the center, if we understand ourselves thoroughly, then, like the hollow brass target, we discover that our minds are empty. This is a metaphor for our minds being completely dynamic. In other words, if we are truly centered in our perception, we will discover that our minds are not material—they certainly aren’t just our brains, and they aren’t any sort of static substance. Furthermore, our minds cannot be stilled, they cannot be stopped in a single state. Every person’s mind is movement.

How wonderful then if we can find the center of a constantly shifting infinity. Once we find that center, we can also realize balance. Only knowing the center of a circle can bring a sense of proportion. Only knowing the center allows us to divide the circle into two halves, and only two halves yield balance.

The mind is infinite. Any point and every point in one’s mind is the center. The mind has no shape and no limits to its size, and yet it is also a circle with a circumference that is everywhere. The mind stretches endlessly, and yet it can also be balanced around its center. All this is possible to understand: just look at the word “zhong.”

But what is pierced remains empty, even after you take care to stretch the string neither too loose nor too tight.

Centered

The word zhong has many meanings: within; among; in; middle; center; while (doing something); during; China; Chinese. The ideograph is a picture of a circle on a flagpole. But it has also been interpreted as a spherical target on a pole or tree pierced by an arrow. Perhaps there’s something to that because “zhong” also means to hit the mark; to be hit by; to suffer; or to win (as in a prize or lottery).

“Zhong” has also been interpreted as “balance,” and you can look at the word as two halves balancing on a central axis.

Stretch the string neither too loose nor too tight,

to find the middle way that stretches right.

According to the example of Buddha hearing the lute player, the right way to live is to be neither too loose nor too tight. Should we talk in terms of too loose or too tight? If you’ve ever tuned a string instrument, you know that there is only one tension to sound the perfect note; there is only “just right.”

There aren’t many one-stringed instruments. The erhu has two strings, played with a bow. The average modern grand piano has over 230 strings. We should not be “one-stringed” in our spiritual outlook. Yes, the middle way means to have a string tuned just right, but if you have many well-tuned strings, you can make great harmony—and always be able to vibrate to the tune of whatever comes your way.

Anyone who plays an acoustic instrument will tell you that it varies every day. Changes in temperature and humidity alter the tone immediately. The instrument has to be tuned frequently: before we can have the harmony of music, we have to be in harmony with heaven and earth.

If you recall how much Laozi valued emptiness, it’s worth seeing that every musical instrument requires emptiness. The stringed instruments have sound boxes, the woodwinds and brasses are hollow tubes, and the drums are skin stretched over big cylinders or kettles. Bells and cymbals have hollows, and sticks and triangles need to have the air around them to produce sound. Furthermore, the musical instruments need the emptiness of the chamber or concert hall to sound their best—a lute played in the middle of the desert can hardly be heard well.

Isn’t all of creation stretched across heaven’s expanse? All of existence is ongoing music. Stretch and tune our strings and let heaven play us.

To find the middle way that stretches right, the swan geese fly in autumn and spring.

• Fasting day

Examples of the Middle Way

In Hexagram 11, Prospering, of the I Ching, the reading for line 2 states:

Encompass the wasteland by crossing the river without a boat, but do not advance so far that you abandon comrades to perish. Win honor by a middle course.

“Encompassing the wasteland” and “crossing the river without a boat” are metaphors for attempting ambitious, nearly impossible things. However, no matter how great one’s actions, one wins honor through a middle course.

Another example of the importance of the middle comes from the Analects:

Yao said: “O, you, Shun. Heaven’s order rests with you. It grants you the responsibility of holding the center. All around the four seas are in need. Let heaven’s prosperity be forever established to the end.”

Emperor Yao (2333–2234 BCE) was a legendary Chinese emperor who passed the throne on to Shun (twenty-third to twenty-second century BCE). The word “order” literally means “calendar and numbers.”

Buddha’s Middle Way

Buddha’s understanding of the middle way—avoiding the excesses of sensuality as well as asceticism—is captured in a traditional story. The story has many variations, but here is a representative one:

When Buddha was sitting by the river one day, he heard a lute player tuning his instrument.

Buddha realized that a lute string must be tuned neither too tightly nor too loosely to be in tune, and at that moment, he understood the Middle Way.

The swan geese fly in autumn and spring:

they follow the Tao of season and place.

The southern Sacred Mountain of Hengshan is known for its gods, temples, history, and beauty. It is also known as a place where swan geese stop during their migration. Geese represent yang, because they follow the sun south in the winter: they are honored because they know the seasons. Since they often fly in pairs, they were also recognized as the symbols of fidelity in marriage.

The swan geese are models for us. Could we spend part of the year in one place with the delicacy of a guest, not worrying about leaving when we felt it was time? Could we then have the energy to fly thousands of miles, following our own instincts, navigating by the stars, and the rivers, and the mountaintops? Could we find where we belong, with a memory that was imbued in our very bodies? The ancients thought that the swan geese demonstrated faith, because they were never lost; duty, because they were never deterred from their destinations; and propriety, because they arrayed themselves in a formation for orderly flight.

The swan geese are not afraid. The expanse of heaven is enormous; the risk in migration is ever present. Through some ability that human beings still cannot comprehend, the swan geese are rarely lost. Heaven and earth are vast, the swan geese are tiny, but they are not afraid to fly with single-minded determination to follow their Tao.

The swan geese cross rivers many people never cross during entire lifetimes. They fly over mountains no human has ever climbed. Even the great sacred mountain of Hengshan is but a way station for them. They are unafraid to transcend limits, and yet they know the path that they must follow, and for that, they evince a natural brilliance.

If only we could fly like the swan geese.

They follow the Tao of season and place, and ask, “Have you heard the breath of heaven?”

• Birthday of the Great God of the Southern Peak (Nanyue Dadi)

• Fasting day

The Southern Sacred Mountain

Hengshan in Hunan is the South Great Mountain of the Five Sacred Mountains and is a mountain range of seventy-two peaks. The southernmost peak is Huiyan, meaning Wild Geese Returning, because geese come back to it every year. The highest peak is Zhurong, named after the God of Fire. Du Fu, Han Yu, and Cai Lun were all born in Hengyang, just to the south of Hengshan.

The Grand Temple of the Southern Mountain (Nanyue Dai Miao) has a history that dates to the Tang dynasty. It was rebuilt in 1882 during the Qing dynasty.

Buddhism, Taoism, and Confucianism all coexist at Hengshan in the Eight Temples of Buddhism, the Eight Temples of Taoism, and the Imperial Library Tower.

The Great God of the Southern Peak (Nanyue Dadi) presides over the south, receives the prayers and offerings of the people, and guards an entrance to the underworld. In the past, emperors traveled to make sacrifices to him along with the gods of the other sacred mountains.

the twenty-four solar terms

Extremely cold weather marks this period. Crops and livestock must be protected and people must be cautious—even as they go about their celebration at the year’s end.

This exercise is best practiced during the period of 11:00 P.M.–3:00 A.M.

1. Begin from a kneeling position, supporting yourself by pressing your hands on the floor behind yourself. Raise one leg and kick it forcefully forward. Then switch positions to kick with the other leg.

2. Exhale as you kick; inhale as you change positions. Breathe normally as you change sides. Repeat fifteen times on each side.

3. Sit cross-legged and face forward. Click your teeth together thirty-six times. Roll your tongue between your teeth nine times in each direction. Form saliva in your mouth by pushing your cheeks in and out. When your mouth is filled with saliva, divide the liquid into three portions.

4. Inhale; then exhale, imagining your breath traveling to the dantian and then swallow one-third of the saliva, imagining that it travels to the dantian.

5. Repeat two more times until you’ve swallowed all three portions.

6. Sit comfortably as long as you like.

Through this exercise, ancient Taoists sought to prevent or treat circulation problems; pain or inability to move the tongue or the body; difficulty standing; swelling in the torso or limbs; abdominal distension; diarrhea; and difficulty walking.

Have you heard the breath of heaven?

Is it any different from you?

There is a breath of heaven. Nominally, we call it wind, but it isn’t just wind.

There is a breath of the human. Nominally, we call it inhalation and exhalation, but it isn’t just inhalation and exhalation.

The breath of heaven moves in gales and howling storms—but the subtlest of forces create the more obvious wind.

In just the reverse of that, the coarse breathing of a human being can help us discover a more subtle, invisible force associated with that breathing. Our mind commands our bodies to move. How does it do that? Do you say it’s just nerves and chemicals? If you say that, you are not wrong—but you’re not completely right either. It’s the breath—our own internal energy—that moves in us at the command of the mind to achieve all that we wish to achieve.

So if you stop the coarse outer breath—when, as Ziqi puts it, the hollows are again quiet and empty—why do you continue to live? There has to be a more subtle life force that continues on between breaths. Then, from the outside, we will look like the master—all dry wood and dry ash. But from the inside, we will be able to discern a far more subtle and refined energy.

When the wind stops, nature does not stop. When our breath stops, life does not stop. It is just at that moment that you must go inside, that you must go into the gaps, hollows, and pits. There, in the stillness, is what is to be sought.

Is it any different from you, when you hear how great is the one with faith, courage, and strength?

The Wind Through the Openings

This passage from Zhuangzi compares the stillness of meditation to the stillness of the earth when the winds have calmed down.

Nanguo Ziqi sat leaning on a low table, gazing up at heaven, and breathing gently. He appeared to be in a trance. His disciple, Yan, was standing beside him and exclaimed, “What is this? Can your body become like dry wood and your mind like dry ash? The man leaning on the table is not the one who was here a moment ago.”

“Yan, it’s good that you ask. Just now, I lost myself. Do you understand? You may have heard the music of people, but not the music of earth. You may have heard the music of earth, but not of heaven.”

“Can you tell me more?” asked Yan.

Ziqi replied: “There is a great cosmic breath. We call it wind. Sometimes it’s not active, but when it is, it howls fiercely through ten thousand openings. Have you ever heard a roaring gale?

“In the mountain forest, mighty and awesome, great trees a hundred spans around have gaps and hollows like nostrils, mouths, and ears; like a corral, or mortars, or pits. The sounds burst out like geysers, or an arrow, or like scolding, shouting, wailing, moaning, or gnashing. The first sounds hiss, and then come enormous fusillades. Small breezes make small harmonies, cyclonic winds make great harmonies. When the ferocious gusts have calmed, all the hollows are again quiet and empty. Have you not seen this phenomenon so marvelous?”

The word rendered here as “phenomenon” means both “change” and “tune,” so there’s a double meaning in that Ziqi is simultaneously talking about sound and great transformations. The word translated as “marvelous” means “artful,” “tricky,” or “cunning,” so here the meaning is that these sounds and transformations reveal a greater, “crafty” order.

Great is the one with faith, courage, and strength,

who fulfills duty against ice and death.

Su was caught in a horror not of his own making, and yet he maintained his honor and determination. He tried to kill himself, and having already nearly died once, was unafraid of death. First Wei Lu put a sword to his neck, but Su would not surrender. The chanyu tried to starve him, but Su would not surrender. Then he was exiled for years to a frozen wasteland. The chanyu sent General Li Ling, who had been defeated by the Xiongnu in 99 BCE, to visit Su. Li told Su that both his brothers had been accused of treason and had committed suicide, that his mother had died, and that his wife had remarried—but Su would not surrender. Li was sent again some eight years later, to inform Su of Emperor Wu’s passing—but though Su wept and vomited blood, he would not surrender. He kept his hand on his imperial staff, the emblem of his office: in his years in exile, the hairs of the decorative tufts all fell off, but his grip on his staff never weakened.

When Su returned home, he was given a high-ranking post and lauded for his faith and indomitable loyalty. When we look at ourselves and lament the way that fate seems to test us, do we suffer as much as Su Wu? There is nothing more important than unwavering determination.

Who fulfills duty against ice and death, and who will never stop seeking Tao?

Tending Sheep

Su Wu (140–60 BCE) was a diplomat and statesman during the Han dynasty (206 BCE–220) known for his faithfulness and forbearance.

In 100 BCE, Emperor Wu of Han (156–87 BCE) sent Su Wu, Zhang Sheng, and Chang Hui on a goodwill mission to the Xiongnu, a confederation of tribes to the north of China. They were received by Chanyu Qiedihou, who had just come to power.

However, Zhang Sheng conspired with the Prince of Gou and Yu Chang to kill the chief advisor, Wei Lu, and kidnap the chanyu’s mother while the chanyu was hunting. Chanyu Qiedihou learned of the plot, rushed back, killed the prince, and captured Yu.

Su knew nothing of the plot, but tried to commit suicide with his sword. Impressed, the chanyu and Wei ordered Su’s life saved. Zhang and Chang were captured. After Su recovered, Yu was executed and the Han mission was ordered to surrender. Though still weak, Su refused.

The chanyu tried to starve Su into submission. But Su survived by eating the lining of his coat and drinking snow melting into his dungeon. Su was then exiled to Lake Baikal (in present-day Russia) and ordered to tend a flock of rams, while the Hans were told that Su was dead. However, the Han ambassador told the Xiongnu, falsely, that the Han emperor had shot a goose while hunting—and that a letter from Su had been attached to its leg. Surprised, the Xiongnu released Su. Nineteen years had passed.

Never stop seeking Tao

no matter the hardships.

Even though Jia Dao renounced the life of a Buddhist monk and tried to make a career as a poet and scholar (he failed the examinations several times), he evidently never stopped seeking Tao. This poem tells the story of his seeking a hermit and being unable to find him. The master had gone into the cloud-covered mountains to look for herbs.

This is the way it is. The masters of Tao are never easy to find. If one is fortunate enough to encounter them, then there’s the question of how to communicate with them and understand them. And yet, there’s no other way to learn the philosophy and techniques of Tao except through the words that the teachers leave for us. Both Laozi and Zhuangzi emphasize that words alone cannot lead us to Tao. But they are useful markers to point us in the right direction.

When you are a sage some day, remember that others will seek you. Be kind to them. It’s easy to be lost in the mountains.

No matter the hardships, the older I get, the faster time goes.

• Fasting day

An Official’s Leniency Leads to Friendship

Jia Dao (779–843) was a Buddhist monk who gave up the religious life for poetry. He was deeply intent on his art, which the following anecdote shows.

One day, Jia Dao was composing a poem while riding his donkey. He was thinking about the lines:

Birds return to their nests in the trees by the pond.

A monk knocks on a door at midnight.

He couldn’t decide between the words “knocks” and “pushes.” As he rode along, acting out the movements, he didn’t notice that he was headed for an official entourage, and he did not give way as he should have. He was immediately arrested and brought before the official.

Fortunately, the official was Han Yu. He asked Jia Dao to explain himself, and Jia explained that he was trying to choose between two words. This intrigued Han Yu, who considered for a long time before suggesting “knocks” as the better word. The two became friends from that day on.

This is one of his poems, “Seeking a Hermit and Not Finding Him,” preserved in Three Hundred Tang Poems.

I asked the child under the pine tree.

“My teacher went to gather herbs,” he answered.

“But in the midst of these mountains,

deep in the clouds, I don’t know where.”

The older I get, the faster time goes,

and yet I’ve learned to move fast and not rush.

The old man said: “I’m old now. Actually, I don’t feel much different than before, but others startle me by calling me that. I admit that my hair is white, but inside, I am unbowed.

“I seem to go to funerals and memorials more often. I don’t even bother putting my dark suit away because I know I will have to wear it again soon. Most of the people precious to me are gone—certainly the generation before mine barely has one or two left to light candles at the altars—and I have to support them as they walk, shooing away the children cheerfully offering to help me. I’m sure the day will come when I will be desperate for someone to offer me a hand.

“There is a line of people waiting to die, and I reluctantly accept I’m in that line too. At the moment, I can’t see the end of it. Someday, nobody will be blocking my view. I say that because it’s my duty to tell you of these things. I’m not looking for sympathy, and I’m not complaining.

“The ghosts live with me. I hear them every day. I see them floating in the sky, challenging me: ‘Can you live as we did? Can you die as well as we did?’ Yes, those who went before me were heroes, who lived their lives fully, who proved that integrity could be made real in a vessel of flesh and blood, who demanded that all around them were the best that human beings could be, who never tolerated excuses, who died smiling quietly. I wonder if I can be so strong.

“I am happy to receive these ghosts with their silent demands. I know the time for me to reach for their upraised flags is short. Each moment, I ask myself, ‘Is what I’m about to do worthy of the precious time I have left?’ If the answer is yes, then I go ahead. I am a fool, and I have so little time left to perfect my unique foolishness.

“I don’t waste time as I did in my youth. Doing something completely and correctly the first time is better than fixing mistakes.

“Old age does not slow me down. It is experience and care that make me go slower. True, the older I get, the less time I have.”

And yet I’ve learned to move fast and not rush: that is the greatest good fortune.

Straight Timber Is Cut Down First

Zhuangzi writes of slowness in the story of a bird called the yidai. The name could be interpreted as “idle thought,” or “loose intention.”

In the Eastern Sea there are birds called yidai. They fly low and slowly, almost as if they were incapable of it, and as if they were leading and helping one another. When they roost, they press against each another. No one dares to lead going forward, or to be the last to turn. No one ventures to take the first mouthful in eating, but prefers what is left by others. This is why their movements are blameless, people cannot harm them, and they avoid worry.

Straight timber is chopped down first; a sweet well is exhausted first. Your aim is to embellish your wisdom so as to startle the ignorant, and to cultivate your person to show the ugliness of others. You shine as if you were holding the sun and moon—and that causes all your problems.

In the past, I heard a highly accomplished man say, “Those who boast have no merit. Merit achieved will fade. Fame and success will fail. Who can rid himself of merit and fame and live with the common person?”

The greatest good fortune

is your preparation.

As the new year approaches, we will be wishing each other good fortune, happiness, and long life. But what does good fortune really mean? Are we waiting for something good to come our way? Yes, there is such a thing as good luck, and it’s a valuable gift. It’s something entirely different to stake your life on waiting for such luck.

Good fortune is as simple as finding a place to live that sustains you, surrounding yourself with good friends, making prudent decisions, and cultivating yourself. As a comparison, you can certainly have bad fortune—but if you choose to live in a dangerous place, associate with bad people, are careless with your decisions, and make no effort to discipline or calm yourself, then it’s certainly not “bad luck” that is visiting you. You’re living a toxic life. You maximize your chance of returning to good fortune by choosing to live in good places, choosing good relations, and choosing good work.

We can’t know the future, but we can certainly arrange many things in the future. We make appointments, schedule visits to people and places, begin new ventures with others. If, for example, you buy a farm, then a farm is certainly “destined” to be in your future. This is good fortune that we engineer. The kind of fortune that brings rain or sunshine, or that might spare your farm when others are attacked by disease, is luck.

So we have to be careful about fortune. What we do when we arrange things in advance, follow through on initiatives, and arrange to meet with others is the fortune we create for ourselves. The circumstances that occur during the time that we’re carrying out our plans—those are luck. Likewise, sometimes accident is just that. It’s bad luck, but not the bad luck of divine intervention.

We wish each other good fortune. But really, shouldn’t we simply be wishing each other the wisdom to arrange our lives properly in advance? What will happen in the new year is built on what you’ve done this year.

Is your preparation in knowing which phase of the moon is most important?

Zhuge Liang

Zhuge Liang (181–234) was a chancellor of the state of Shu during the Three Kingdoms period (220–265). He is known as the quintessential Taoist strategist, an inventor—and a scholar of exceeding intelligence. Since he lived in seclusion for a time without its diminishing his fame, he earned the nickname Hidden Dragon (Wolong). He is also known by the style name Kongming. Zhuge Liang is often depicted in flowing robes and holding a fan made of feathers.

Many of Zhuge Liang’s deeds have been mythologized. Here are three:

General Zhou Yu (175–210) was jealous of Zhuge Liang and ordered him to make one hundred thousand arrows or be executed. Zhuge Liang agreed to do so within three days. He made a few arrangements but otherwise waited in his tent, drinking wine. On the dawn of the third day, there was a great fog. Zhuge Liang sent boats with decoy soldiers across the river, ordering loud drumming and shouts to simulate the attack. The frantic enemy fired volley after volley into the fog—where the arrows stuck in hay bales on the boats. The boats returned to camp with more than enough arrows.

An attack by fire was prepared, but Zhou Yu realized he’d need an easterly wind to succeed, and there was no breeze at all. Zhou collapsed and became ill. Zhuge Liang visited him and offered to pray for the wind—but he had already determined that the weather would shift. Days later, the eastern wind came. Zhou Yu thought Zhuge Liang was supernatural and sent men to kill him—but Zhuge Liang had already escaped.

When a city Zhuge Liang was protecting was attacked, he ordered the city gates opened and the soldiers disguised. The enemy would not enter, fearful of an ambush.

Which phase of the moon is most important?

Which shifting takes longer than the others?

No phase of the moon is more important than the others. Each phase is the same length; each transition from one phase to the next takes the same amount of time as all the others. The moon has circled us steadily for millions of years, and it will continue for millions more. Each night, it is the perfect lesson in yin and yang.

We know that the moon’s light is a reflection of the sun’s, but the amount of light that we see simply depends on the moon’s position. If we want to follow the lunar Tao, we simply have to remember to be ourselves—just as the moon never really changes shape—and we simply have to reflect the light of heaven in the orbit that is our life. What could be easier?

Which shifting takes longer than the others? Only one prepared can find a teacher.

The Phases of the Moon

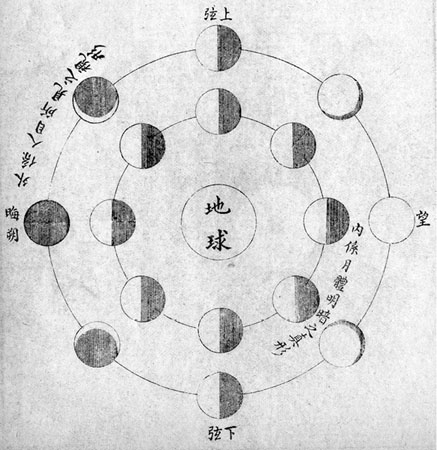

In the illustration below, the sunlight is coming from the left. The earth is at the center. The moon is shown at eight stages during its revolution around the earth. The middle circle is the moon as it’s actually illuminated by the sun; the outer circle is the moon as it appears to us.

Half of the moon is always lit by the sun. We often see both the sunlit portion and the shadowed portions simultaneously, and that creates the various moon phases.

The new moon occurs when the moon is between the earth and the sun, and the illuminated portion of the moon is on the side away from us.

In contrast, during a full moon, the earth, moon, and sun are in approximate alignment, and the moon is on the opposite side of the earth. The sunlit part of the moon faces us and the shadowed portion is hidden.

The first-quarter and third-quarter moons, called half moons, occur when the moon is at a 90° angle in relation to the earth and the sun.

After the new moon, when the sunlit portion is increasing but is less than half, it is waxing crescent. After the first quarter, the sunlit portion is more than half, so it is waxing gibbous. After the full moon, the light continually decreases, and this is the waning gibbous phase. After the third quarter is the waning crescent; the moon wanes until the light is completely gone and a new moon occurs again.

Only one prepared can find a teacher.

Only a teacher makes other teachers.

Unless Wang Chongyang was prepared by being intelligent, familiar with Taoism, and knowing martial arts, how would he even have been worth the notice of Han Zhongli and Lu Dongbin? The immortals are looking for others to join them, but they are looking for candidates who are ready.

According to legend, Wang intended to begin a rebellion against the Jin dynasty (1115–1234), established by the invasion of Jurchen tribes from Manchuria. However, his life shifted when he met the immortals. Was he seeking Tao, or was Tao seeking him?

Once he was initiated into the inner traditions, Wang progressed quickly. He went into seclusion for some time on the same mountain where Laozi passed down the Daodejing. Surrounded by other recluses and the beauty of nature, he practiced sincerely and deeply. According to one account, he built a tomb on Zhongnanshan, calling it the “Tomb of Living Death,” and stayed in it for three years. At the end, in a symbolic rebirth, he emerged, filled the tomb with earth, and built a hut on top of it, naming it the “Complete Perfection Hut.” He burned the hut in 1167.

There is no learning without teachers. There are no teachers if others do not teach them. There are no new teachers if no teachers will teach others. If you would seek Tao further, prepare yourself so that the teachers can recognize you. If you learn well, then teach others.

Only a teacher makes other teachers: when you’re alone, always act like a guest.

• Birthday of Wang Chongyang

Wang Chongyang

Wang Chongyang (1113–1170) was one of the Five Northern Patriarchs of the Quanzhen (Complete Perfection Sect of Taoism). According to traditional beliefs, he met Han Zhongli and Lu Dongbin of the Eight Immortals in 1159, and they initiated him into the inner traditions of Taoism. Already an accomplished martial artist, Wang undoubtedly adapted to the techniques quickly.

Following this, he went to Zhongnanshan near Xi’an to practice and teach others. This was the same mountain where Laozi is believed to have written the Daodejing and that became an important retreat for both Taoist and Buddhist hermits. Chongyang Palace and other buildings on that mountain honor Wang.

Wang had seven disciples, the Seven Disciples of Quanzhen. One of the most best known of this group was Qiu Changchun.

© Peter Pynchon

When you’re alone, always act like a guest—

as if the Kitchen God lived in your heart.

Whether or not you believe in the Kitchen God, you recognize his true function: conscience. If you understand that, you don’t need his altar on your floor. Far better to have a Kitchen God inside you. Far better to have a conscience and to heed it.

Conceiving of a supernatural tattletale is really missing the point. It’s better not to have a conflict with our conscience. In other words, it’s better to act correctly in the first place. Maybe your response is that this is hard to do. It isn’t really. Why not simply act correctly and dispense with the guilt, the conflict, the vacillations, and the stress?

By this analogy, you invite the Kitchen God up from his place on the floor and ask him to speak to you on a daily basis. Make him your advisor. Involve him before you have to do something. Surely after centuries of watching people do good and bad, right and wrong, he has a worthwhile opinion.

When you’re alone, act like a guest. Act like someone is watching you. After all, most misdeeds are done in the dark and away from others. Most misdeeds are kept secret. However, if you’re watching yourself, or if you manage to make your conscience an integral part of your decision making, then you are unafraid for your actions to be known.

If that’s the case, then you’ll put the Kitchen God out of business. That’s a worthy goal. Then he—not you—can just be a guest in your house.

As if the Kitchen God lived in your heart, make the wish: “Will my dear friend return next year?”

• Kitchen God reports to heaven

• Fasting day

The Departure of the Kitchen God

This is the day that the Kitchen God leaves the family and flies to heaven for his audience with the Jade Emperor. Having sat in the kitchen, hub for all activity, for nearly an entire year, he’s had ample opportunity to observe the good and bad deeds of the family. He makes his report to the court so that all of a family’s activities are known to heaven. The Jade Emperor will punish or reward the family based on the Kitchen God’s report.

In order to ensure that the Kitchen God will say only good things—or perhaps to glue his mouth shut if there aren’t many good things to say—the family smears his mouth with honey. Then they burn his picture so that he can be sent to heaven in the smoke. The family will install a new picture of him on the day he returns.

Will my dear friend return next year

and break the silence with music?

The ghost of the poet said: “Dear friend, I’ve walked with you to see you off, and now we’ve ventured deep into the hills. Here, at the edge of the county, we must finally say farewell.”

“Each day spent with you was joyous, and yet each day hastened the moment of parting.”

“Where will you go?”

“I’ll search the village markets for some herbs to strengthen myself. The road is long and icy, and I won’t have a companion like you to depend on. But I feel guilty that I took so much of your time. Go back to your work—your music, your painting, your poetry, your official duties, and your practice with the abbot.”

“But who will read my poetry as you do, or listen to my music as you do, or appreciate my paintings as you do? Make sure you stay busy yourself. Go to the capital. Give my letter of introduction to the prince. He’ll recognize a worthy man like you! Don’t just hide behind the garden gate!”

“Why talk that way? You know I’m a man of ambition. If I can find the right opportunity to work with others, I’m sure I can make a great contribution. You needn’t worry about me—as I hope that I needn’t worry about you! May your door swing constantly with honored guests and patrons!”

“But none of them can take your place in the garden, exchanging couplets with me, or performing duets.”

“Stop frowning! Throw open your doors. Go out and light up the world!”

“Good-bye, dear friend. Will you come in the spring?”

“Only if you promise to be merry in my absence!”

“And only if you promise to go straight to the capital.”

And break the silence with music, though nothing lasts. But long or short, we’re still here.

• Fasting day

Poems of Parting

Poems of parting are virtually their own subgenre of Chinese poetry. Here is one from Wang Wei.

We accompanied each other into the hills until we had to stop.

As day becomes dusk I shut the timber door.

The spring grass will be green next year.

But will my honored friend return or not?

Meng Haoran wrote this poem, “Parting from Wang Wei.” While we don’t know that this is a direct answer to Wang Wei’s poem, it fits well. The sixth line is a reference to the story “High Mountain, Flowing Water”.

When will my loneliness end?

I must go home, where day after day will be empty.

I could seek other worthy people,

but I’m reluctant to part with an old friend,

Who will keep me company on this road?

Few in this world know the same music.

All I can do is keep my solitude,

go back, and close my old garden gate.

Nothing lasts. But long or short, we’re still here.

Good or bad, all things pass—and still return.

Nothing lasts. By now, we don’t need the sages to tell us that. Living long enough, we know. The glorious might of youth stumbles, the highest tower of civilization tumbles, the loveliest piece of carved jade crumbles. Nothing lasts.