Chancing Upon Old Friends at a Village Inn

It’s autumn, and the moon is full again.

A thousand-layered night covers the towns.

We meet together south of the river.

I turn—it’s like a dream to meet by chance!

The wind startles the magpies from their roosts,

insects tremble in the dew-covered grass.

We travelers linger and get deeply drunk—

each one tarries, fearing the morning bell!

—Dai Shulun (732–789)

The two solar terms within this moon:

WHITE DEW

AUTUMN EQUINOX

the twenty-four solar terms

The days grow dry. The sky is clear and the temperatures mild, but it grows cold enough that dew forms.

This is the beginning of the harvest season. The fields are golden, and farmers gather to reap grain, soybeans, and sorghum. Cotton is full.

Winter wheat is planted as well, so this is a busy time on the farms.

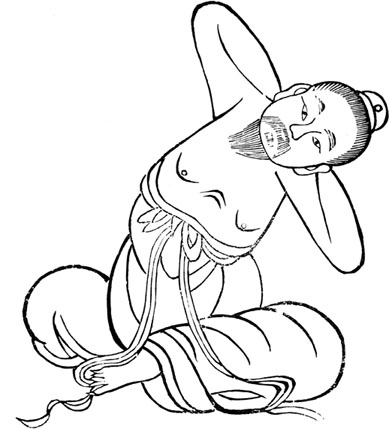

This exercise is best practiced during the period of 1:00–5:00 A.M.

1. Sit cross-legged and press your palms over your knees.

2. Slowly turn your head side to side as if you’re trying to look behind you. Inhale when you turn your head to the side; exhale gently when you return to the center. Repeat fifteen times on each side.

3. Facing forward, click your teeth together thirty-six times. Roll your tongue between your teeth nine times in each direction. Form saliva in your mouth by pushing your cheeks in and out. When your mouth is filled with saliva, divide the liquid into three portions.

4. Inhale; then exhale, imagining your breath traveling to the dantian and then swallow one-third of the saliva, imagining that it travels to the dantian.

5. Repeat two more times until you’ve swallowed all three portions.

6. Sit comfortably as long as you like.

Through this exercise, ancient Taoists sought to prevent or treat rheumatism in the back and thighs; nosebleeds; dark coloring appearing in the lips and face; swelling in the neck; vomiting; and mental illness.

Let all war end today.

Let peace bloom in our hearts.

The white dew in the morning can remind us powerfully that winter follows autumn. The weather will be cooling in time, the nights will grow longer, and winter will approach steadily.

White dew can look like tears, and it’s a reminder that the world is still at war. Du Fu, writing more than 1,250 years ago, lamented how war was still raging in autumn when families should have been coming together to celebrate their bond and the bounty of the harvest. Today, we are still at war somewhere in the world. Families are still torn apart and scattered. Mad and selfish warlords still order gun and cannon fire and devastating explosions as expressions of their fiery ambitions. In a thousand more years, autumns will still come, but will humanity have given up war?

We should all eschew weapons, those ominous instruments. We should all take a bodhisattva vow to put all other beings ahead of ourselves. We should each do what we can to bring peace to everyone we meet. And yet, violence, oppression, and demonic cruelty continue as despots throw millions of bodies to the monsters of war. How do you change that?

If you say you will change it by sitting on a meditation cushion, you sound hopelessly naive. If you say you will change it by legislation, you are doomed to political struggle. If you say you will change it by social action, you are a swimmer fighting against the tides. In thousands of years, you say, the human condition has not changed. That is to be accepted. But good people have always been here too. Holy people have never stopped in their effort to bring peace. The only real question is, will you be good or evil? Choose good. That’s the true test.

Let peace bloom in our hearts and strike the bell: ringing is instant.

Steve Evans

• Fasting day

Autumn and the Tragedy of War

Du Fu wrote this poem in 759 during the An Lushan Rebellion (755–763). Estimates of the death toll are as high as thirty-six million.

The goose is a symbol of autumn as well as letters from afar.

Army drums cut off human travel.

Along the autumn borders, a lone goose calls.

Today is the start of White Dew;

how bright the moon seemed in my home village.

My brothers are scattered.

No one’s home to ask if they are alive or dead.

The letters we send never reach them,

and still the war does not stop.

Weapons Are Ominous Instruments

In one part of Chapter 31 of the Daodejing, Laozi writes:

As for weapons: they are ominous instruments.

All creatures hate them.

Hence, those who have the Tao do not handle them. . . .

Weapons are ominous instruments.

They are not the instrument of the noble person.

They are used only when there is no choice.

Quiet and calm are superior; victory is not beautiful.

Those who consider it beautiful exult in killing people.

Those who exult in killing people never find fulfillment under heaven.

Strike the bell: ringing is instant.

Open your heart: the Way is there.

The tower outside this metropolitan temple shelters a bronze bell beneath a peaked tile roof. A smoothed log hangs horizontally from a rope, aligned perfectly with the center of the bell.

The bell was cast by an old master far away. Esoteric symbols adorn every inch of it. Even a bell that was cast relatively recently wears the symbols from thousands of years ago on a shape so classic as to be timeless, so timeless that it appears as primordial as the mountains that rise in huge grooved crags far outside the city.

Pull on the rope. Let the striker slide back, then release it. The weight of the log is perfectly calibrated to strike the bell with just the amount of force to maximize its deep, sonorous reverberation. The bell sounds, and those hearing it cannot stop themselves from looking up.

They’ve been summoned. They notice that their hearts are still shaking from the sound, even though the bell hangs hundreds of feet away.

There is a saying, “The harder you strike the bell, the bigger the sound.” How you strike the bell stimulates your enlightenment—and as soon as you strike the bell, the sound is instantaneous.

Open your heart: the Way is there. Then killing is good, if you kill all your faults.

Song of Returning at Night to Deer Gate Mountain

Meng Haoran (689–740), anthologized in Three Hundred Tang Poems, was only partially successful as a civil servant—passing the examination at the age of thirty-nine and resigning his first and last appointment after less than a year. He wrote primarily about landscape, history, and legends. He was a close friend of Wang Wei. Lumenshan—Deer Gate Mountain—is south of Xiangfan in Hubei.

The mountain temple bell signals the coming of dusk.

Noisy fisherman bustle onto the ferry,

while others follow the sandy banks to riverside villages.

I board a boat back to Deer Gate Mountain.

The moon on Deer Gate shines on misty trees.

Suddenly, I arrive at an ancient hermitage.

Rustic door and pine, long in quiet:

just a hermit returning alone.

Noclue119

Killing is good! If you kill all your faults.

Kneeling is good! If I kneel and find good.

The meditator said: “Let me take this as my daily meditation:

“I will pull all faults, regrets, inabilities, and shame out of myself. Each one is like a black basalt rock. I will stack these rocks day by day into a wall, so that they are outside of myself, mute, unmoving, having no place but to be dead in a wall. Then I will go to a golden temple heaped with fragrance; I will kneel before the altar, open and without any doubt, and I will pray to be as pure as a god.

© andelieya

“I will pull all faults, regrets, inabilities, and shame out of myself. Each one is like a brick. I will fill a box with those bricks and send it off to some unknown destination, never to return and never to be opened. Then I will go to a golden temple heaped with fragrance; I will kneel before the altar, open and without any doubt, and I will pray to be as pure as a god.

“I will pull all faults, regrets, inabilities, and shame out of myself. Each one is a writhing demon. I will go to a place that is taboo and barren of all living things, and I will slay each one with the sword of mercy. I will go to a sacred pool and wash myself. Then I will go to a golden temple heaped with fragrance; I will kneel before the altar, open and without any doubt, and I will pray to be as pure as a god.

“Each day, I will resolve to eliminate my shortcomings and pray to be good, pray to be flooded with the divine. I will fear nothing. I will hurt no one. I will give myself over completely to the light of the divine.

“I meditate on this each day. I meditate to remove all impediments to Tao. I meditate to help every sentient being. I meditate for purity.”

Kneeling is good! If I kneel and find good, I am at the center of the universe.

• Birthday of the Kitchen God

The Kitchen God

Today is the birthday of the Kitchen God. He watches all that a family does, and reports every detail to the Jade Emperor at the end of the year. Offerings of food, wine, tea, and incense help celebrate his birth.

The Temple of Accumulating Fragrance

The Temple of Accumulating Fragrance (Xiangji Si) is south of the city of Xi’an. It was built during the seventh century in honor of the Buddhist monk Shandao (613–681), a major figure in Pure Land Buddhism, by his disciple Huai Yun. The name is a tribute to the master, suggesting his great holiness. Wang Wei visited there and wrote this poem, “Toward the Temple of Heaped Fragrance.”

I did not know Heaped Fragrance Temple

was so many miles away in cloudy peaks

and old forests few people cross.

It’s the bell that guides me through the deep mountains,

where spring water gushes out a high cliff

from bright sun into cool green pines.

At twilight, by the bend of that deep pool,

peaceful meditation tames the poison dragon.

When Wang Wei uses the word “meditation,” it is the same as the name of Chan Buddhism.

© BirDiGoL/Shutterstock

I am at the center of the universe.

All depends on me, I depend on all.

The realized one said: “I sit here, radiant with light. The universe had no meaning until darkness parted. The stars, the sun, the very medium that gives us knowledge—all is light. I am light. I am alive.

“A circle of light surrounds me. The diameter of that circle is at once measured by the length of my arms and legs, and by the very edge of the universe, with an infinite diameter and an infinite circumference. However wide that circle of light is, it must have a center. I am its center.

“Let me breathe in, and all things come into me as the tide rushes to the shore. Let me breathe out, and all things sail away from me, like a thousand birds borne aloft on the trade winds. Let me think but one thing, and it exists. Let me forget one thing, and it is gone.

“When I move, it is the same force that turns the sun and the moon. When I am still, it is the same force that has existed since before the universe began.

“I am heaven. Every single cell of my infinite body contains myriad worlds, each one with myriad gods. My body is composed of gods. My body is divine.

“I sit here, radiant with light. I am all inside. There is no outside. There is nothing but the holy. There is nothing but the pure. There is nothing else.”

All depends on me, I depend on all. Why ask where the road goes?

“Brilliance” from the I Ching

Hexagram 30 is “Brilliance.” The hexagram doubles the trigram for Fire.

Brightness doubled: brilliance.

The great person spreads brilliance

to illuminate the four directions.

Why ask where the road goes?

Where are we rushing to?

Here are the ruins of an old fortress. Nothing is left but the foundations, and they are nearly lost in the overgrowth. A distant country once wanted to colonize this place, but it was too far from home, and the soldiers abandoned it hundreds of years ago.

Here are the ponds and fallen walls of the old imperial gardens. The gaily dressed women and proud aristocrats are now mere ghosts blown about in the breezes.

Here is a tumbled temple where devout people came to pray daily, now broken open to the rains, with vines hanging from the rafters.

We build things, and as soon as we stop maintaining them, they disintegrate. As skillful as we are as engineers, as solid as our materials are, nothing lasts. The monuments and palaces of olden times are now barely lines scratched into the dirt beside the highway. People speed by without stopping to match their footprints with those of long-gone kings.

Down the road is a cemetery. The older stones are worn, rounded. Some of the inscriptions are worn. Maybe the sharply etched memories are getting just as dim. The flowers are fresh, so we know people come to pay their respects.

Whether ruins or cemetery, people rush by and ignore them. Only the visits of the living make a place alive.

Where are we rushing to? A wheelbarrow works because of legs and hands.

Lake Namtso, Tibet.

Peter Vigier

“Song to Cherish Ancient Traces”

This poem is the first of a series of five written by Du Fu. Yu Xin (513–581), the subject of the poem, died 131 years before Du’s birth.

In 554, Yu was a poet and a diplomat sent as an ambassador from the Liang dynasty to the Western Wei in Chang’an. But the Liang fell in 557; Yu was imprisoned in Chang’an for the rest of his life, and three of his children were executed. Nevertheless, Yu is well known in literature for his accomplishments in the rhyme-prose form (fu; also called the prose poem).

Pulled from east to north in wind and dust,

cast adrift from south to west between heaven and earth,

he traveled where the Three Gorges’ towers and terraces block sun and moon,

and where the five streams join to dress the cloudy mountains.

When the barbarian serving our ruler rebelled in the end,

our exiled poet grieving for the times did not return.

Yu Xin’s whole life was bleak,

yet the poems and rhyme-prose of his twilight years moved rivers.

A wheelbarrow works because of legs and hands:

someone still needs to grip it and push it.

The wheelbarrow sits there, ready. One wheel, two legs. It’s stable. Once someone lifts it, though, there’s a certain balance that’s necessary, and learning to use a wheelbarrow takes a little practice—like learning to ride a bicycle. Why not use a cart with two, or even four wheels? It’s because the mobility and simplicity of the wheelbarrow are better.

The handles are right where one can hold them with arms nearly straight and without stooping over. One can therefore move a great deal of weight: the wheelbarrow is not a rolling cart, but two levers and a wheel. It’s a combination of two fundamental inventions. It’s rough, improvisational, rocky, but efficient. The wheelbarrow is powered by a person’s legs, body, and arms, but it greatly increases what that one person is able to do.

The wheelbarrow is the symbol of work. It’s also the symbol of migration—so many times in old China, people would load their belongings, or perhaps a child or elderly person, into a wheelbarrow to flee from famine or invaders. One piles on as much as one can. We could say it has one personpower.

Today, we are smug, saying that we can do much more work than one person can. Our engines are measured in hundreds of horsepower, our computers hold entire libraries on our desks, and children hold mobile devices more sophisticated than once-gigantic mainframes. But we’re still measuring work by one person, aren’t we? Whether wheelbarrow or personal computer, it’s the person doing the work, not the tool, that matters.

Someone still needs to grip it and push it, just as light cannot be seen without shade.

The Wheelbarrow in Ancient China

The earliest wheelbarrows in ancient China that we know of are from a mural found in a second-century Han dynasty tomb. Wheelbarrows are also depicted in a carved stone relief in a Sichuan tomb.

A filial son named Dong Yuan is remembered because he moved his father from place to place in a wheelbarrow. The official Zhao Xi saved his wife from danger during the Red Eyebrow Rebellion (Chimei; c. 20) by disguising himself and telling the rebels that he was carrying his terribly ill wife in a wheelbarrow.

The Records of the Three Kingdoms (Sanguozhi), compiled by the historian Chen Shou (233–297), credited Zhuge Liang with the invention of the wheelbarrow to help move military supplies.

There were two main types of wheelbarrows: those with a front wheel, and those with a large, centrally mounted wheel. This latter type could be sized to transport as many as six people. Some wheelbarrows were drawn by horses or mules, and there were even wheelbarrows with sails.

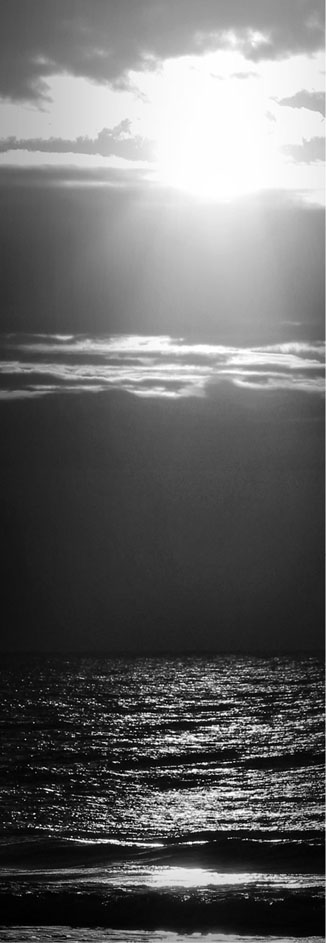

Light cannot be seen without shade.

Shade cannot be seen without light.

By moonlight, we see in black and white. We cannot see colors. There is something fascinating and valuable about seeing the world that way. We see only what is essential. We see form emerging from a sea of blackness. We can appreciate shape and depth without the distraction of color or even meaning. We can look at the world so familiar by daylight and see it anew in the black and white of moonlight.

You see yin and yang.

If the door is not open, it’s closed. If having it closed is what you want, then that’s perfect. The closed door not only keeps two rooms separated, but may itself be something to look at as a handsome piece of handiwork.

You see yin and yang.

A good faucet in the bathroom is useful. You can have all hot water, all cold water, or a mixture of the two.

You see yin and yang.

The plug in the electric socket. The hinge pins holding the door. The top of a cabinet versus its drawers. What’s on one side of a window and what’s on the other side. Beyond our walls, the sun shining until it sets.

You see yin and yang.

Left and right. Up and down. The day warms, the night cools. The sun moves over a hill, changing the face from brightness to shadow. Stand in the middle of a bamboo forest and watch all the shadows and sunlight shift second by second.

You see yin and yang.

Shade cannot be seen without light; even when old, Du Fu could still wield his golden halberd.

Yin and Yang

This is one of the most popular and well known symbols of Taoism. It is a modern derivation of the Taiji Diagram (Taiji Tu) shown in the Compendium of Diagrams (Tushubian) by Zhang Huang (1527–1608). Some scholars have found similar diagrams from as early as the Tang dynasty. Earlier, yin and yang were represented by the tiger (yin) and dragon (yang).

The diagram’s meaning is that yin and yang interlock and cannot be separated: one cannot perceive one without the other. The dot of the opposite color within each area means that even in the most extreme cases of yin or yang, there is never totality—the beginnings of the opposite are generated even in the midst of seemingly complete yin or yang. The I Ching teaches us that when anything reaches its greatest point it inevitably begins changing toward its opposite.

The words “yin” and “yang” themselves are another way to understand this concept. Pictorially, the ideogram for “yin” depicts the shady side of a hill.

“Yang” is a picture of the sunny side of a hill. If one watches a hill all day, the sun and shadows will move. The sunny side cannot be seen without the shade, the shade cannot be seen without the sun.

Tan Wei Liang Byorn

Du Fu could still wield his golden halberd.

It was his horse, and not he, who stumbled.

If you’re middle-aged or older, you can’t help but notice the effects of aging. You might not be as strong, or as flexible, or as quick-witted as you once were, and you might find yourself troubled by pain and weakness that your doctor dismisses as “minor.”

Everywhere people describe aging in disparaging terms. We fear growing old, fear being discarded, fear being ineffective. There aren’t many good roles given to older people in today’s fast-moving and youth-obessesed world. We admire the home run, the jumping splits, the multi-octave singing, the new speed record, the wild new idea from a college student that sparks a billion-dollar company. We don’t admire a gray-haired person sitting quietly and sharing wisdom.

Even Taoism might be accused of fearing aging. After all, longevity and the search for immortality are central to so many Taoist beliefs. From the Queen Mother of the West’s peaches of immortality to the God of Longevity, the Taoist could be accused of being as preoccupied with avoiding aging as anybody else is. Du Fu soberly reminds us that Xi Kang, for all his wisdom, creativity, flair, and Taoist alchemy, was still executed.

We need a new attitude on aging. Look at the words “growing old”: growing is certainly positive, and there are so many things that get better with age—wine, antiques, redwoods. As we age, we have to recognize how we are still growing. We have to recognize that each stage of our lives is unique and valuable.

Bluntly put, we’re all going to die, and we’ll experience infirmity at the end as our bodies shut down. Accept that. Having accepted that, though, means that we embrace the unique features of each moment of our lives, accept that we are changing, find the growth in whatever stage we find ourselves in, take advantage of the insights that come to us, and use our wisdom to live healthy lives for our own benefit and the benefit of others.

Let us speak of aging not as a process of deterioration, but as a process of growing old.

It was his horse, and not he, who stumbled. Don’t be hemmed in by destiny or place.

• Fasting day

Why Hurry to Ask About Me?

Du Fu’s poem “Many People Bring Wine to See Me After I Fall Off My Horse Drunk” was written about 766. Xi Kang was one of the Seven Sages of the Bamboo Grove.

I, Du Fu, the duke’s old guest,

finish my wine, sing drunkenly, and brandish my golden halberd.

Astride my horse, I am suddenly young again.

Hooves scatter stones tumbling down Qutang Gorge.

Out of White King City’s gates above the water and clouds,

I lean forward and charge straight down eight thousand feet.

Whitewashed walls pass, I turn like lightning, my purple reins loose.

To the east, I reach a plateau, outlined against the sky,

gallop past rivers, villages, fields, halls.

I drop the whip, slacken my purple bridle,

and ride on, startling ten thousand people with my hoary head.

Confident, rosy-faced, I can still shoot arrows while riding.

It was hard to know, hard to judge by its winded steps

and its red sweat, that this black trace horse snorting jade

would suddenly stumble and fall injured.

In human life, quick thoughts lead to many humiliations.

Now I lie forlorn with quilt and pillow.

It’s now late at dusk and I’ve added to your troubles and bother.

When I learned you were coming, I wanted to hide my face.

Using a pigwood cane, I get up and lean on a servant.

When we finish our talk, we laugh loudly

and, hand in hand, sweep by the bends of the clear stream.

Wine and meat stacked like mountains,

our feast begins with sounds of sad strings coupled with brave bamboo.

Together, we point to the western sun—there is no stopping it.

We exclaim and sigh and tip cups of strained wine.

You needn’t have ridden your horse to ask after me;

don’t you know that Xi Kang nourished life and was still killed?

Don’t be hemmed in by destiny or place.

Leap right through the air onto your new land.

Whether there was really a Fusang that Hui Shen found is not as important as the fact that Fusang fired the imaginations of people for over 1,500 years. We each need to have a Fusang in our lives. If we only thought of our world as where we travel each day, our world would be small indeed. We would remain like Zhuangzi’s frog in a well.

So we travel. We go on long treks. We move across the country or even across the world. We are curious about everything. We read. We go to movies. We explore on the Internet. In every way, we challenge our boundaries every day. We might even take it farther: we could not survive if we did not think beyond our boundaries. We could not even stay sane.

When we think of gods, we are thinking of a world even farther away than Fusang was from China. When we meditate and open up the infinite world within us, we are pushing against the very shell of our normal references. We pass our mental borders and enter the world of meditation, which need not have any limits.

There is a passport that one can receive if one applies for it in person. Those issued by government agencies are automatically invalid. Merely saying that one has such a passport is as much folly as Napoleon crowning himself, and is worthless.

Every child began with a passport. Many are destroyed by parents and teachers. Others are lost. Some are put away in drawers and forgotten for years, while others sit in the trembling hands of those too afraid to use them. Most of us have to be reawakened and apply for a new one.

Those who use their passports find them stamped only when they cross a border.

Leap right through the air onto your new land. Otherwise, why climb the mountain? Just because it’s there?

Fusang

Fusang was first described by the Buddhist Hui Shen in 499 as a country some 20,000 li east of the Great Han (one li is 415.8 meters; 20,000 li translates to about 5,167 miles, or 8,316 km). It is thought that Hui Shen traveled from China to Japan to Korea and then from the Kamchatka Peninsula to Fusang. The stipulated distance would mean he may have visited a place somewhere in British Columbia. There is no single agreement on where Fusang might actually be, only that it is a legendary place far to the east of China.

The Frog in the Well

This is a line found in the Zhuangzi: “One cannot speak to a frog in a well about the ocean.” It has become an idiomatic phrase.

Why climb the mountain? Just because it’s there?

We climb to make offerings to heaven.

In the past, being with nature was an integral part of Chinese culture. Emperors regularly visited Hengshan to make offerings and sacrifices so that the human world would stay in harmony with the heavenly one. There was a sense that people had to acknowledge heaven, that we were subordinate to heaven, and that only a sacred attitude toward heaven and our existence was right. What better place to go, then, than a high mountain where the vistas and beauty made the sense of a higher order obvious?

We still need sacredness today. There are still churches and temples. We still receive the bodies of soldiers killed in war with solemnity. We put up impromptu shrines for those killed on the street. We know to give thanks when we escape a bad accident. We are grateful when we manage a rare accomplishment. That all shows that we still need sacredness, and if we look further, we can find sacredness beyond our everyday means. We have to climb the mountain ourselves. Hengshan means the Permanent Mountain. The high mountain that is the ideal altar for worship will always be there. The path of the mountain will always be there. Heaven waits for us beyond the peak.

We climb to make offerings to heaven, for sunset is not death but serenity.

Priestess on Hengshan.

© Saskia Dab

• Birthday of the Great God of the Northern Peak

The Great God of the Northern Peak

The Great God of the Northern Peak (Beiyue Dadi) is the god of one of the Five Sacred Mountains, Hengshan (Permanent Mountain), in Shanxi. (Note that the southern mountain of the Five Sacred Mountains is also written as Hengshan, but this is a different Chinese word, and that mountain is located in Hunan.) Hengshan has been a place of pilgrimage and offering since the Zhou dynasty (1046–256 BCE), and the temple to the Great God of the Northern Peak dates to the Han dynasty (206 BCE–220). Li Bai’s calligraphy of praise is still there—two characters, zhuang guan—”spectacular.”

One of the Lesser Grotto Heavens, Hengshan has a long association with Taoism. One of the Eight Immortals, Zhang Guolao, cultivated immortality there.

The Great God of the Northern Peak receives offerings; grants good fortune; presides over rivers, streams, all four-legged animals (especially tigers and leopards), reptiles, and worms; and guards one of the entrances to hell.

One of the most famous Chan Buddhist masters, Mazu Daoyi, studied with his master Nanyue Huairang (677–744) on Hengshan. The Hanging Temple, a series of temples built onto the sheer side of the mountain, supported by narrow posts set into the rock, is one of Hengshan’s most famous features.

© andelieya

Sunset is not death but serenity:

In this dark world at peace with love and hate.

The sun sets at the ocean’s edge and people flock to watch it. Some light bonfires on the beach, as if they cannot bear to watch the sun go down, or as if they need to create their own fire to remember the sun. No, no—it’s even more primitive than that. We are driven into a state without words, where we only know to go toward flaming light, and once we are there—unblinking, mesmerized, silent—we feel a fulfillment impossible to reach any other way.

The sun sets at the ocean’s edge and we watch it, perched on a seawall, strolling hand in hand with a lover, romping with our children and dogs, or falling into a reverie that can only happen at twilight. In that slight space between day and night is a dream world that we dimly recall from childhood, a world where gods walk out of the oceans, spirits cavort in the trees and breezes, and our memories unfold before us in fables no storyteller can recount.

Are our memories only the record of what we ourselves did at one time in our lives? Or can we have memories that are not our personal history, but the history of a people? After all, we are not just ourselves, not just tiny people with fragile stories; we are part of a long line of people that were once here and a long line of people that will be here, and we, in the middle, can remember all that those before us and all that those after us can know.

We know all that at sunset, when the world pauses around a flaming orb plunging into the waters, setting the sky in a pattern that our minds don’t comprehend but our hearts read. We sing those lyrics long into the night.

In this dark world at peace with love and hate, remain unblinded by today’s needle.

“North in Qingluo”

This poem is by Li Shangyin.

The sun sets in the west behind the mountain.

I call on the thatched hut of a solitary monk:

only fallen leaves—the man is gone.

Cold clouds cover the road in several layers,

A stone gong signals the start of night.

I pause and lean on my rattan staff.

This world is small as a grain of dust:

I’m at peace with love and hate.

Remain unblinded by today’s needle.

See that all people are the same as you.

In China’s past, the populace was called “the black-haired people” because everyone had black hair. Today, though we live in a global community where hair color varies, the idea of complete commonality among all humanity is still relevant. We might need a new term that transcends race or outer features. Maybe we need a term like “the breathing people” or “the heart people.”

It’s harder to see the similarities between ourselves and others in this multicultural world. After all, systematic dehumanization of another group is behind racism, sexism, and oppression. For centuries, people have refused to see their commonality with others. Nations have justified invasion, enslavement, and genocide by claiming that it was their right and that the others were less human. Even today, labels like “other tribes,” “other countries,” and “other skin colors” divide us. But as we move to a more enlightened world, we can make the leap to seeing what is really there: commonality with all other people. If you look deeply at people, they all look like you.

If you look at others deeply, how can you miss having compassion and consideration for them? The man who collects your garbage, the mechanic who fixes your car, the waitress who takes your order—all these people serve you. And all these people look like you.

You’re going to keep moving through your world, accepting the services of others. If you remember, however, that they are just like you, there will be more compassion in the world, and the payments, gratitude, and recognition you accord to others will be paid back to you.

See that all people are the same as you: crossing to the other side is the task.

Examples of the “Black-Haired People” from Ancient Texts

Mencius refers to a good country where “persons of seventy wear silk and have meat to eat, and the black-haired people suffer neither from hunger nor cold.”

In the Classic of History, the Great Yu says of the sovereign who knows how to rule wisely: “When he appoints the right officials, brings peace to the people, and confers kindness, then the black-haired people cherish him in their hearts.”

In a lament from the Classic of Poetry, a poem about a terrible drought has the line, “Of the black-haired people of Zhou, few will be left behind.”

Black Heads and Millet People

There are two sets of words translated as “black-haired people.”

Qianshou means “black heads.” Notice how the second word, “shou,” is part of the word “Tao”.

The words for “black-haired people” are limin, and their meaning is instructive. “Li” combines words that mean “millet” with the symbol for a knife, an old coin, or measure. The modern meaning of the word is “numerous,” “many,” or “black.” The second word, “min,” means “people,” “subjects,” “citizens.” It was once a symbol of an eye being pricked by an awl—meaning a slave—but the modern meaning is positive and is a part of terms such as “public,” “popular,” “citizen,” “democracy,” and “nationality.” (It’s possible that this word originated thousands of years ago when people were regularly captured during wars and made into slaves. The needle in the eye may have been a threat or a direct method of enslavement.)

Crossing to the other side is the task.

Even if the bridge sways, we have to cross.

Here is a footbridge that is barely wide enough for one person. It’s suspended over a ravine, green water running far below it.

The bridge sways from side to side. It bobs up and down. The planks flex and pull at the ropes from which they’re suspended. Each step is fearful, and the person’s mind starts wondering whether retreating or sprinting would be possible if the tenuous span were to snap. Five feet in, it’s already obvious that there is only crossing—or plunging fatally into the river below if the bridge were to break.

The bridge does not break. It moves with a rhythm so frightening and unpredictable that gracefulness is impossible. Instead, a drunken stumbling emerges, the feet pushing against sinking floorboards or struggling against abrupt heaving. Only by staggering, pitching, and rolling is it possible to reach the other side.

This bridge is made of wood, iron, and rope. People cross it every day, and those who cross it all the time no longer notice the swaying; they don’t even break their conversation as they stroll across.

We don’t remember the names of those who first pinned the ropes. We don’t know the names of those who cut and planed the timbers. But their service makes it possible for generations of people to carry on their lives.

Be the sage that is the footbridge.

Even if the bridge sways, we have to cross—why care if you drunkenly spill your wine?

The Couple’s Bridge

HiveHarbingerCOM

There have been many suspension bridges in Chinese history, but one of the most famous is the Anlan Bridge in the Dujiangyan Irrigation System near Chengdu.

The Anlan Bridge was constructed in 1803, during the reign of Qing Emperor Jiaqing (1760–1820), replacing two earlier bridges. The construction was led by He Xiande and his wife. However, local officials misappropriated the funds earmarked for the bridge’s construction, and when He Xiande reported this, he was killed. People rose up and asked He’s wife to direct the construction of the bridge. When it was finished, the bridge was named Anlan, meaning “couple.” The bridge was replaced in 1975 by a steel and concrete structure, but the Couple’s Bridge stood in its earlier form for 172 years.

Anlan Bridge.

Prince Roy

Why care if you drunkenly spill your wine?

“What’s poured on the table drenches the world!”

That’s an old drinker’s expression. You might say it’s merely a means of consolation, but within it is the assumption that what goes on in us also moves the world.

Most of the time, we say that human beings must learn to sublimate themselves to nature and to heaven. We speak philosophically of how we must follow Tao.

However, Tao also follows us. It’s a difficult and subtle point. After all, we are part of Tao too. If we say we are not, it’s a huge philosophical mistake. Speaking as though we are outside of Tao would be to separate ourselves from it, and if there’s any definite mistake, it’s alienation. So we are part of Tao. Therefore, what we do and think is also Tao.

There is a line in Li Bai’s poem “Singing on the River” that captures this attitude. “Inspired! Intoxicated, my moving brush shakes the Five Sacred Mountains.” The emperors believed that the world would fall apart without devotion; Li Bai declares that his will could move mountains.

Perhaps that’s why these poets loved wine so much: they sought to release themselves from the constraints of conventions, and with their power so unleashed, they could accomplish great things. So if alienation is the primary sin, here’s the second one: to be squeezed by conformity and convention. Taoism is the antithesis of Confucianism, and wine is the symbol for Taoism’s wilder side. We are Tao and we want to remove all that interferes with that.

We must remember that wine in itself is not the real means any more than there’s an elixir of immortality. Any mature person knows that there is no single secret ingredient to spirituality. In fact, before you know it, anything you believe or practice can become a trap. That’s why the masters of old challenged their students with seemingly irrational behavior, with shouts and contradictory pronouncements: they knew that every means of liberation could also backfire.

It’s funny, isn’t it? Drunkenness helps us transcend our limitations, but the ultimate drunkenness is to be drunk without wine.

What’s poured on the table drenches the world: that’s how we might celebrate all under the sun.

• Fasting day

The Wine Immortal

Li Bai (701–762) is often named as China’s best poet. He’s admired for his unconventional stance and the deep emotions that his poetry conveys. He is also known as Li Taibai, “Great White,” in reference to the planet Venus, in addition to various extravagant titles: Householder of the Green Lotus, Poetry Immortal, Wine Immortal, Exiled Immortal (meaning exiled from heaven), and Poet-Knight Errant. Li Bai confirms this last title: “When I was fifteen, I was fond of swordplay, and challenged many great men with my skill.”

Li Bai never sat for the imperial examinations, but his brilliance was admired by Emperor Xuanzong (685–762), and he was named to the Hanlin Academy. He leaves behind about one thousand poems. According to legend, he drowned trying to embrace the moon’s reflection in a river.

One of his most famous poems is “Drinking Alone Under the Moon.”

A pot of wine among the flowers;

drinking alone without companions.

I raise my cup to invite the bright moon:

we two and my shadow make three.

While the moon cannot drink

and my shadow only follows my body,

we are quick friends—the moon, shadow, and me.

On with joy all the way to spring!

I sing as the moon lingers.

I dance with my shadow, staggering.

While sober, we share our joys.

Thoroughly drunk, we each wander off,

never again to be lonely in our travels—

next time we’ll invite the distant clouds and stars.

The Moon Festival is also known as the Mid-Autumn Festival (Zhongqiu Jie) or is simply named by its date, “Eighth-Moon-Fifteenth.” This day is the autumn equinox, and this is the month in which the moon looks the largest in the night sky. It’s one of the most popular festivals and has a history dating back to the Shang dynasty, three thousand years ago.

The moon’s round shape symbolizes completion and wholeness, and for most Chinese people, this means a family reunion. Family members gather to enjoy the full moon, which is the symbol of abundance, harmony, and luck. After nightfall, families will go for a walk or enjoy picnics to view the moon. If some family members are away, it’s natural to think of those who may be far from home. The Mid-Autumn Festival is also a romantic night for lovers, who sit holding hands on riverbanks and park benches beneath the brightest moon of the year. Su Shi wrote this poem in 1076 while drunk and missing his brother, Ziyou. It expresses the feelings of those missing loved ones during the Mid-Autumn Festival.

When will the bright moon appear?

Holding a wine cup, I question the blue sky.

I don’t know what time of year it is tonight

in the palace towers of heaven.

I would ride the wind and go there,

but fear those elegant buildings and jade eaves,

and that I couldn’t last in the height and cold.

I rise to dance with my pale shadow—

better to stay in the human world.

The moon around the cinnabar pavilions

comes low through silk-draped doors

to shine on the sleepless.

There should be no regrets for anyone,

so why are we separated for so long?

People have sorrow and joy, parting and reunion.

Like the moon waxing or waning or going from full to crescent,

since ancient times nothing has ever been perfect.

Nevertheless, I wish you long life,

so we’ll share a thousand kinds of grace and beauty!

The last five lines have entered the culture as idiomatic phrases. “People have sorrow and joy . . . nothing has ever been perfect” expresses an acceptance of the human condition. The last two lines have become an expression of good wishes to others.

The Moon Goddess I

We retell the story of Hou Yi and Chang’e every year during the Moon Festival. They lived on earth during the time of the legendary Emperor Yao around 2200 BCE.

Hou Yi was an archer in heaven. Chang’e was a young attendant to the Queen Mother of the West. They fell in love and were married. However, the other gods were jealous of Hou Yi, and they slandered him before the Jade Emperor. The emperor banished Hou Yi and Chang’e to earth. Hou Yi used his skill to hunt for food and eventually became famous for his archery.

At that time, there were ten suns. Each one was a three-legged bird, and they roosted in a mulberry tree across the sea. Each day, one of the birds sat in a carriage driven by Xihe, the mother of the suns. One day, however, all ten birds rushed out together, drying up the lakes and burning the earth. Emperor Yao commanded Hou Yi to shoot down all but one of the suns, which is why we only have one sun today.

As a reward, Hou Yi was granted a pill of immortality that might restore him to heaven. Emperor Yao advised Hou Yi to prepare himself by meditating and fasting for a year before taking it. Hou Yi hid the pill in the rafters of his house.

Later, Hou Yi was again summoned by Emperor Yao. While he was gone, Chang’e noticed beams of light coming from the rafters and found the pill. She swallowed it and floated into the air. Startled and ashamed when she heard her husband come home, Chang’e flew across the sky. Hou Yi followed her, but strong winds blew him back. Chang’e landed on the moon and coughed up half of the pill. She asked the rabbit who lived on the moon to help make more elixir for her husband. People can still see the shadow of the Jade Rabbit in the moon as he pounds herbs.

In the meantime, Hou Yi lives in the sun far from his wife. Only once a year, on the fifteenth day of the eighth moon, is Hou Yi allowed to see his wife, which is why the moon is at its fullest and most beautiful on the night of the festival.

Li Shangyin wrote this poem entitled “Chang’e.”

The candle casts deep shadows on a mica screen.

The endless river of stars falls, the morning star sets.

Chang’e must regret stealing the divine elixir:

in an azure sky over the green sea—she ponders night after night.

The Moon Goddess II

There are many versions of this story, but this one is significantly different in adding a villain and a bitter ending.

In this version, the gods sent Hou Yi to earth to save it from the errant suns. Chang’e was a beautiful mortal, and when she met the divine archer, the two fell in love immediately. Hou Yi loved her so much that it pained him to think that she could not live with him forever as an immortal.

Accordingly, he traveled to the Queen Mother of the West to ask for the elixir of immortality. Since Hou Yi had saved all of earth, she gave him two doses so that Chang’e could become immortal and Hou Yi could return to heaven. Overjoyed, Hou Yi returned home, and he and Chang’e made plans to take the elixirs on the fifteenth day of the eighth moon.

However, an evil man named Feng Meng had followed Hou Yi and was spying on the couple from outside. He wanted the elixir for himself. When Hou Yi went out hunting, Feng Meng confronted Chang’e and demanded the elixir.

Determined to prevent Feng Meng from gaining the elixir, Chang’e hurriedly swallowed both bottles and immediately rose to heaven. Unable to bear the thought of being separated from her husband, she managed to divert herself to the moon.

In the meantime, Hou Yi returned and learned from a maid what had happened. He fought with Feng Meng and killed him, then tried to find Chang’e. He saw that the shadow in the moon looked exactly like his wife. Running with all his might, he rushed toward the moon, but with every step, the moon seemed to rise farther away.

Finally, Hou Yi built a palace inside the sun, and the couple continues to long for the day when they might be reunited.

The Red Thread

Once a boy walking home at night met an old man in the moonlight. His name was Old Man Under the Moon (Yue Xia Lao). The old man said that he had tied the boy to his destined wife by a red thread and showed the girl to him. Being young and immature, the boy threw a rock at the girl and ran away.

Many years later, when the boy had grown into a young man, his parents arranged for a marriage. On the wedding night, his wife waited in the bedroom with a red veil over her face, as was the tradition. The young man lifted the veil, and was delighted to see that his wife was beautiful—even with the faint scar on her forehead. When he asked about the scar, his wife told him the story of a boy who once threw a rock at her.

This legend persists in a folk practice: if you want to stay together as a couple all your life, tie two juniper branches together with red thread and put them under your bed. You can also go to the Longshan Temple in Taipei, where you can pray to the Old Man Under the Moon.

Wu Kang and the Cassia Tree

The shadows of the moon might also be a magical cassia tree. There was once a woodcutter named Wu Kang who wanted to become immortal. When the Jade Emperor heard of such audacity, he banished Wu Kang to the moon, telling him that he had to chop down the cassia tree before he could become immortal.

However, no matter how much Wu Kang chops day and night, the cassia tree regenerates with each blow. He can still be seen in the full moon, chopping at the tree.

Jade Rabbit

There is a reason why Chang’e found an immortal rabbit on the moon.

In the distant past, three immortal sages traveled the earth disguised as three aged and weak old men. Meeting a fox, a monkey, and a rabbit, they asked for something to eat.

The fox and the monkey had food and gave it to the men to eat. But the sages were still hungry. The rabbit had nothing to give. Offering itself, it jumped into the fire so it could be roasted and provide food for the old men.

Impressed by its selflessness, the immortals restored the rabbit to life and sent him to live in the Moon Palace.

Mooncakes

Mooncakes are central to the Mid-Autumn Festival. These pastries are about three inches in diameter and about one and a half inches thick. Mooncakes are round and golden, like the ideal harvest moon. They have a thin crust and a variety of fillings, such as lotus seed paste; sweet red, black, or green bean paste; egg yolks from salted duck eggs; jujube paste; the Five Kernel (wu ren) combination of walnuts, pumpkin seeds, watermelon seeds, peanuts, and sesame seeds; and many more variations.

A mooncake is dense and rich, so it’s often cut into wedges. Served with tea, it’s eaten while people gather to admire the moon.

There are other kinds of mooncakes, depending on local customs, availability of ingredients, and historical differences. A Beijing-style mooncake has a light and foamy dough; a Cantonese-style mooncake can have rich fillings of ham, chicken, duck, roast pork, and up to four egg yolks; and Yunnan-style mooncakes might combine rice, wheat, and buckwheat flour for the dough. Mooncakes have spread beyond China, with Indonesia, Japan, Vietnam, the Philippines, and Thailand developing their own versions.

Businesses have contributed to the mooncake market as well. Innovative mooncakes have been made with chocolate, taro, coffee, fruit, seaweed, and ice cream. It’s customary for families and businesses to give mooncakes as gifts during this time, and the sales of mooncakes are tracked in Asia as an economic indicator.

A folktale associates mooncakes with the overthrow of the Mongol Yuan dynasty and the establishment of the Ming dynasty in 1368. The Ming revolutionaries used mooncakes to smuggle secret messages to one another. Zhu Yuanzhang, the leader of the Ming (and eventual first emperor), and his advisor, Liu Bowen, began a rumor that a deadly plague was spreading. The disease could only be prevented by eating a special kind of mooncake. This prompted the distribution of more mooncakes—with a message that the revolt would begin on the fifteenth day of the eighth moon.

A more complicated method entailed embossing a message baked into the decorations on top of the mooncakes and packaging the cakes in groups of four. Each mooncake had to be cut into four parts and the resulting sixteen wedges was then reassembled to reveal a secret message. Once the message was decoded and understood, the mooncakes were eaten, thereby destroying the message.

We might celebrate all under the sun,

but also honor all under the moon.

All our great accomplishments are made under the sun (including by artificial light). We celebrate that which is yang: technology, government, warriors, champions, money, and all that is patriarchal. In the meantime, all that is yin— women, mothers, emotion, creativity, intuition, art, love of nature, gentleness, mysticism, and the pure miracle of life itself—we fail to comprehend or honor.

The Moon Festival is a time for women to celebrate. It is the time of poets. It is the time to remember that all that is yin also makes the world function. The Lunar Tao comes down to this: can you comprehend the Way that is dark and yet is as vital and powerful as what we celebrate in the light? This day is close to the autumn equinox: a reminder that yin and yang are equally important.

The Mid-Autumn moon is the harvest moon. At this time, the fields we planted and labored over during the preceding moons show their results. Yes, we must work—yang. Yes, we must make decisions about what to plant and what to grow—yang. Yes, we must go out with tools to weed and then harvest what we grow—yang. What we cannot do is make the plants grow any faster. We cannot do more than give them what they need and then invest the time that it takes for everything to ripen. In that, it is all yin. We can engage in agricultural science, but after a certain point, we can do nothing more than let nature take its course. That is yin.

No plant ever grew upside down. No season but autumn came after summer. No pear trees bear apples. Nature is true, time after time. Follow that path to truth. Give yourself completely to the Lunar Tao.

But also honor all under the moon as we are all journeying to see Buddha.

• Fasting day

• The Moon Festival

The Mid-Autumn Moon

Su Shi wrote the following poem for this day:

Sunset clouds gather in the distance: it is clear and cold.

The Milky Way is silent and has become a jade plate.

The goodness of this life does not last long.

Where will I be next year to see the bright moon?

Taoist Moon Meditation

1. Sit in meditation facing the moon.

2. When you’re calm, imagine that the moon descends until it is over your head.

3. Imagine that it’s inside your head.

4. Gradually let its light fill your entire body, eradicating all illnesses and blockages.

5. Hold that image as long as possible.

Sun- and Moon-Faced Buddha

The Blue Cliff Records tells of Mazu Daoyi, who was indisposed. When the head monk asked how he was, the master replied: “Sun-faced Buddha, moon-faced Buddha.”

the twenty-four solar terms

The night and day come to equal length. From this point on, the nights will grow longer. The weather is colder, and rain comes.

This exercise is best practiced during the period of 1:00–5:00 A.M.

1. Sit cross-legged and press your palms gently over your ears.

2. Slowly bend from side to side as if you’re trying to touch your elbows to your knees. Exhale when you bend; inhale when you return to the center. Repeat fifteen times on each side.

3. Facing forward, click your teeth together thirty-six times. Roll your tongue between your teeth nine times in each direction. Form saliva in your mouth by pushing your cheeks in and out. When your mouth is filled with saliva, divide the liquid into three portions.

4. Inhale; then exhale, imagining your breath traveling to the dantian and then swallow one-third of the saliva, imagining that it travels to the dantian.

5. Repeat two more times until you’ve swallowed all three portions.

6. Sit comfortably as long as you like.

Through this exercise, ancient Taoists sought to prevent or treat rheumatism in the ribs, legs, knees, and ankles; distension in the abdomen; incontinence; thirst; and asthma.

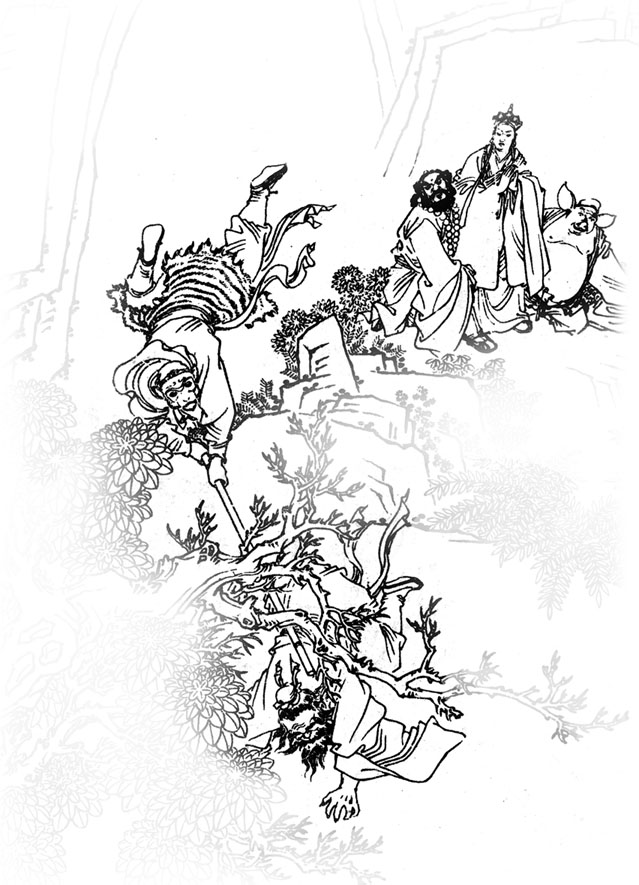

The Monkey King is one of the most popular, beloved, and accessible characters in all of Chinese culture. Known also as Sun Wukong (Realizing Emptiness) and the Great Sage Equal to Heaven (Qitian Dasheng), he is a superhero and the focus of novels,operas, dramas, songs, movies, television series, comic books, and children’s books, and he will undoubtedly be featured in media to come.

We know him best through one of the four great classical novels of Chinese literature, the epic Journey to the West (Xi You Ji). This book was first published anonymously in the 1590s during the Ming dynasty; the author has since been identified as Wu Cheng’en (1505–1580). People love the Monkey King because he is mischievous, gleefully overturns every social convention, triumphantly defies heaven, and in his own way is more wise than nearly everyone except Buddha and Guanyin.

The Actual Journey to the West

Journey to the West was inspired by a Chinese Buddhist monk named Xuanzang (c. 602–664), who journeyed from China to India in the early Tang dynasty to study Buddhism and to bring back as many sutras as possible. His pilgrimage took him seventeen years. He returned in 645 to considerable honor, declined all offers to enter imperial service, and devoted himself to teaching and translation for the remainder of his life. In addition to his religious work, Xuanzang wrote an autobiography and account of his trip, Great Tang Records of the Western Religions (Da Tang Xiyu Ji). Along with a biography by the monk Huili, such factual records of the journey must have inspired Wu Cheng’en to embellish the events into his fantastical tale.

In Journey to the West, Xuanzang makes his famous pilgrimage with the supernatural help of the Monkey King, Pigsy (Zhu Bajie—Pig of the Eight Precepts), Sandy (Sha Wujing—Sand Enlightened to Purity), and Jade Dragon, a dragon prince transformed into a white horse. The group encounters eighty-one trials before they complete their quest and return to China. The Monkey King is clearly the star of the epic.

The Story of the Monkey King

The Monkey King was born from a stone formed by the primal forces of chaos. Finding a band of monkeys, he becomes their king, naming himself the Handsome Monkey King (Mei Houwang). However, he realizes that he is still mortal, so he journeys until he finds the Taoist Patriarch Subodhi. His master names him Sun Wukong, and the Monkey King learns a variety of magic arts, including shape-shifting in the form of the Seventy-Two Transformations, cloud somersaulting that covers more than 33,554 miles (54,000 km) in a single flip, and the ability to transform any of the 84,000 hairs on his body into an object or living being. However, the Monkey King’s boastfulness offends the master. Patriarch Subodhi sends the Monkey King away, telling him never to reveal where he learned his arts.

The Monkey King returns to his monkey clan at Flower and Fruit Mountain, but he grows restless. He wants a weapon truly fitting to him. After more searching, he eventually acquires a marvelous staff from the Dragon King of the Eastern Sea. It weighs more than eight tons and can change from an ordinary staff to an enormous pillar. It was originally used by the Great Yu to measure the ocean’s depth. In the Monkey King’s hands, it is a light and versatile weapon—and he is able to shrink it to the size of a sewing needle and hide it behind his ear when he doesn’t need it. He also wins golden chain mail, a phoenix-feather cap, and cloud-walking boots from the dragons.

When death comes to collect the Monkey King, he goes to hell itself and wipes his name from the Book of Life and Death, thereby removing himself from the cycle of reincarnation. The Dragon Kings and the Kings of Hell complain to the Jade Emperor, who dispatches troops to arrest the Monkey King.

However, after many battles, the Monkey King and his followers defeat all of heaven’s armies. He steals the peaches of the Queen Mother of the West, Laozi’s elixir of immortality, and the Jade Emperor’s wine, and he defeats the great general Erlang. Through combined Taoist and Buddhist forces, the Monkey King is eventually captured and put into Laozi’s Eight Trigram furnace to reclaim the elixir of immortality. After forty-nine days, however, the Monkey King emerges stronger than ever and with the added ability to see evil in any form. The Jade Emperor appeals to Buddha, who imprisons the Monkey King under a mountain for five hundred years.

When Guanyin searches for heroes to protect Xuanzang, the Monkey King eagerly offers to help. In order to control him, Guanyin gives Xuanzang a golden hoop that magically stays on the Monkey King’s head. Whenever he misbehaves, the monk chants and the band constricts, causing much pain. Together with Pigsy, Sandy, and Jade Dragon (the white horse), the Monkey King escorts Xuanzang to India, where they receive an audience with Buddha before they all return safely to China.

Temples to the Monkey King

There are temples to Sun Wukong in Hong Kong, Macau, Taiwan, Singapore, Malaysia, and Indonesia. In the past, monks at a Buddhist temple in the Sai Mau Ping area of Kowloon were possessed by the Monkey King and performed feats that only Sun Wukong could do—walking on fire or climbing ladders of steel blades—as they reenacted the story of the journey to bring back sutras.

We are all journeying to see Buddha,

all while trying to tame the monkey mind.

We each must find Buddha. We are all pilgrims. To reach Buddha is to reach ourselves, the spiritual core that in itself will be a fountainhead of wisdom. Once we reach that Buddha, we need no other deity: we become Buddha, the Enlightened One. To reach Buddha is to be enlightened.

Then comes the long path back. We have to return, bringing the scriptures, spending the rest of our lives processing and sharing. That journey requires the taming of the monkey mind. Notice that the monkey cannot be destroyed. It can only be given the proper role, a true place in our lives, and finally, the honor of having brought us to Buddha and back.

All while trying to tame the monkey mind, we light fire to share warmth.

• Birthday of the Monkey King

Monkey Mind

Monkey mind (xinyuan) means the mind that is unsettled, restless, capricious, whimsical, inconsistent, confused, indecisive, and uncontrollable. This mind is also brilliantly creative, smart, and inventive.

The term was originally Buddhist, dating from as early as the fifth-century phrase “mind like a monkey” in the Chinese translation of the Vimalakirti Sutra. The phrase has been adopted by Taoism, Confucianism, poetry, drama, and literature.

The common phrase we have today, “monkey mind or horse thought” (xinyuan yima), still means a mind that is hyperactive, adventurous, and uncontrollable. The expression is rooted in the Buddhist description of the mind being as restless as a monkey and the will galloping like a horse.

Remember that the word translated as “mind” is the same as the word for “heart”.

We light fire to share warmth

on the cold granite heights.

Fire made civilization possible. Until we had fire to cook and boil water, to light the darkness, to clear land, to melt and forge metal, and to dispel the cold, we were unable to progress. Beginning an estimated 400,000 years ago, human beings were able to use fire to improve their lives.

Wisher of Warmth is surrounded by myth and legend, but he personifies the human need for and use of fire. That’s worth honor and worship. Without fire, we would revert to primitive levels very quickly.

We think nothing of flipping a light switch, turning on the furnace, or lighting the stove. It’s worth pausing and thinking about these things, and being grateful for them. Fire is fundamental to our lives, and it’s important to remain aware of what’s fundamental.

According to legend, Wisher of Warmth had a red face, was highly intelligent—but had a bad temper. Without our internal fire, we would not be human either. Sometimes, anger and ferociousness are necessary. In the same way that we have to control fire to keep it from destroying us, we have to control our tempers if we are to move forward. In English, “temper” also means to moderate and control. The tempering of our emotions makes the difference between Wisher of Warmth and destroyer with fire.

On the cold granite heights, we see that every river flows back in time.

TheNeon

• Festival day of Wisher of Warmth

The Red Emperor

Wisher of Warmth, or Zhu Rong, is also known as the Red Emperor (Chidi), the god of fire and deity ruling over southern China. He wears armor, wields a sword, and rides a tiger.

In the distant past, Zhu Rong battled his own son, Gong Gong, a water demon who was flooding the earth. Gong Gong attempted to seize control of heaven itself, but his father fought with him for days until both fell to earth. Gong Gong was defeated and Zhu Rong returned to heaven.

In another version of his origin, Zhu Rong was named Li and was the son of a tribal chieftain who learned how to make and store fire and taught primitive people how to cook food. The Yellow Emperor invited him to join his court and appointed him Fire Administrator, giving him the title Zhu Rong.

When a tribal chief named Chiyou attacked, the Yellow Emperor named Zhu Rong the head of an army against Chiyou’s eighty-one brothers—all of whom could spew smoke from their mouths. But Zhu Rong armed his men with torches and bombs, and they won the war.

The Yellow Emperor sent Zhu Rong to Hengshan, to oversee the south. People came to offer him tribute each autumn, and they began to call him the Red Emperor.

Zhu Rong lived to be over one hundred years of age and was buried on the tallest peak of Hengshan. A hall in his honor is still there.

Every river flows back in time.

When waves flow upstream, remember.

High on the mountains, the snow melts—first in a trickle, then in a gathering stream, then in rivulets joining as headwaters. Springs deep in rock fissures gush from some mysterious source and add to the flow. The waters run down the slopes and become a river that is young, new, fresh—tumbling, rushing, surging with a power that can overturn rocks, uproot trees, and flood plains. After many miles, it reaches the mouth, having grown old, flowing to the sea to join a far larger body of water, churning sand and earth and mixing with the salt of the sea, stirring the stuff of new land, new cells, new life. Then the waters rise into the air, free of their particulates, as if their work is done and they must go into heaven as a sacred vapor. Eventually, the waters become rain and snow—and then they become the river again.

Is a life like that too? Coming to birth, running with the power of youth, flowing with full maturity, joining in an ending that is not a negating death but a fulfillment, then rising to heaven purified—only to cycle back again? Is that what’s called returning to our source?

If so, does knowing that bring peace? For then, life is no prize and death is no penalty. In fact, there is only life, turning, turning, turning. Thinking only of our “life span” is like identifying only the course of one river as the sole existence of water—when we know that course is only part of a much greater cycle.

The water reaches the sea, the sea rises in the clouds, the clouds rain on the mountain, and the river continues to run. So let us not be worried about what comes after death: we know.

When waves flow upstream, remember that all is possible if you choose the right place and know how to build.

• Fasting day

• Qiantang Tidal Bore

The Tidal Bore

A tidal bore is a wave that travels up a river from the ocean against the river’s current. The water is turbulent and audible, churning sediment and air in a powerful roar. The Qiantang tidal bore is the largest in the world. It can be as high as thirty feet (nine meters) and travel up to twenty-five miles per hour (forty kilometers per hour).

The tidal bore occurs each full moon, but it’s particularly powerful around the spring and autumn equinoxes. Crowds gather to watch it. Occasionally, the surge has been powerful enough to top the embankments. People get too close and perish.

Su Shi, who was vice prefect of nearby Hangzhou from 1071 to 1073 and prefect from 1089 to 1090, would have had many opportunities to see the tidal bore. Here is the third of five quatrains, “Watching the Tidal Bore.” The Qiantang River normally flows east, which gives Su Shi’s last line its resonance.

On the riverbank, I’m a person so much at odds with the world.

I’ve long been as white-headed as the waves.

The creator knows how easily we grow old,

So he teaches the river to flow west.

If you choose the right place and know how to build

nature will come to you in abundance.

There is an enormous barrel on a hill, made by a cooper who died some years ago. The barrel has never leaked or rotted in all this time, and that alone is more than enough to marvel at. How can mere wood and copper, rivets and workmanship, keep a barrel from leaking?

Beyond its mere existence, however, the barrel is impressive for its place in a greater design. The barrel is filled by a spring—how blessed we are to have this land that is abundant with water—and from there, the water runs in a system of pipes to supply all that is needed for house, fountains, and ponds. The excess drains into the river.

There is no pump, and yet if we were to open any valve fully, the force of the water would create a geyser that would shoot up twenty-five feet. We have more than enough. Nature is generous. Gravity never fails. The water, filtered through the mass of an entire mountain, is always cool, fresh, and clear.

Bathe in this water, and wounds seem to heal faster. Drink tea with this water, and the purity of the rains and stone seem to enliven the cup. Listen to the sound of water as it trickles over stone, and heart rates slow and people want to linger forever.

Best yet, kneel down, cup your hands, and drink. Everything you need is right there.

Nature will come to you in abundance, even if autumn winds blow with unexpected frost.

Chenyun

The Thatched Hut on Lushan

Bai Juyi (772–846), a famous poet of the Tang dynasty, was a successful official and a member of the Hanlin Academy—the elite group of scholars founded by the Emperor Xuanzong and charged with secretarial and literary responsibilities (Li Bai and Ouyang Xiu were two other members). Bai was demoted and exiled when he remonstrated with Emperor Xianzong (778–820) over the failure to find the murderer of two high officials. He was later restored to office, serving as the prefect first of Hangzhou, and then of Suzhou.

During his exile, he began traveling to Lushan, a mountain famous for its beauty, in Jiangxi Province. He fell in love with the scenery and resolved to build a thatched hut there. As a devout Buddhist, he also visited the nearby temples to meditate. In his essay, Record of the Thatched Hall on Lushan (Lushan Caotang Ji), Bai Juyi describes the hut as having unpainted beams and rustic plaster walls left without whitewash. Slabs of stone formed the steps, sheets of paper covered the windows, and the bamboo blinds were left natural. The furnishings were simple: four wooden couches; two plain screens; a qin; and Confucian, Taoist, and Buddhist books.

He built a trough of split bamboo from a waterfall east of the hut and made a network of bamboo gutters so that water would splash from the hut’s eaves like a string of pearls. In this way, he could delight in the sound and sight of water.

Autumn winds blow with unexpected frost

To live forever is such useless talk.

Sip clear rice wine and sit in moon-cast shadows beneath the arbor. Dragons soar to the fountains of heaven. Phoenixes lead the hundred birds sunward. We need no palace—just a stone stool near a shrine where red candles lean, blackened. Who can be a wild sage of the mountains? A “banished immortal”? What a big laugh. Ice drops from branches into this wine cup and chills the earth to its very root.

The garden this morning was covered with leaves. It was just swept yesterday. And the day before too! In the trees above, more leaves are yellow. That means that there is even more work to come.

Sweep up all the leaves and put them on the compost pile. The leaves fall. It is inevitable, the way of things. It’s our choice whether we work with that, or whether we try to be graceful about it.

The dead matter. Death is ubiquitous, so constant, so much a part of the Way, that there’s no choice but to accept it. People die all the time, and we must recognize that.

The trees above have some green leaves, some yellow, some brown. One by one, the leaves will fall until the branches stand bare against the chilly skies. Our time to face death will come too. We don’t know where we are in the sequence, just as we can’t tell which leaf will fall next. We only know that it will happen.

What truth can be glimpsed before we wither and fall? Can we be the leaf that knows which branch it’s on? Can we be the leaf that knows where its root is?

To live forever is such useless talk—and the wine that can be drunk is not the true wine.

Red Leaves

The anthology Three Hundred Tang Poems includes this piece written by Xu Hun (fl. 830–850), a man who loved both Buddhism and Taoism before he became an official. Since he never achieved a high position, he gradually became more reclusive. His view on the Taoist life is contained in this couplet:

With elixirs, the body is ever healthy.

Without calculation, one’s mind is naturally tranquil.

As the title indicates, the following poem was “Inscribed in the Inn at Tong Gate during an Autumn Trip to the Capital.”

Red leaves; the dusk is mournful, mournful.

I’m at a roadside pavilion with a wine ladle.

Storm clouds blow toward Great Flower Mountain,

a shower crosses the Middle Ridge.

Forests color the distant hills,

one hears the river flowing to the remote sea,

I will go into the capital tomorrow—

Yet I dream of being a woodsman or fisherman.

Wine that can be drunk is not the true wine.

Bowls that can be smashed are not the true bowls.

This wine bowl is antique porcelain, with remarkably thin walls. The rim was once edged in gold that has mostly worn away. Delicate polychrome symbols decorate the sides: a vase with a peacock feather, coral, a flag with the word “command,” a container with a lotus blossom, another vase with peony flowers, a tray with peaches, two fish made to look like a yin yang symbol, an incense burner. The inside of the bowl is pure white.

The bowl may have been used in a home or in some fine inn during the imperial days. It was meant for delicious meals and lingering enjoyment, but also, as the flag with the word “command” implies, it was made for people in authority.

Although the bowl is over one hundred years old, it is not chipped. It has outlived its maker, its first owner, and whoever tossed it into the uncertainty of overseas trade. People are merely custodians, temporary in this world, who may well die before this bowl shatters.

Some of us grew up in households with addicted parents. Some of us may be struggling with addiction itself. Some of us may be enabling others to continue their addiction. Some of us may be trying to recover. Almost everyone recognizes that addiction is bad, including the addicts themselves. The addiction, the struggle against it, and the effort to establish a positive life without it are triply consuming. It’s one thing to say you’re against addiction. It’s another thing to know what to do instead. This wine bowl is beautiful. But what does someone do who sees the reflection on the wine’s surface and finds him- or herself ugly?

The Tao of wine is not a Tao of addiction. It is a Tao of freedom from limitations and acceptance of who we are. Both the addict and the Taoist are faced with pain, but their responses differ.

One is like this wine bowl: one cannot take the shape of someone one is not. Let people live according to their nature, though, and they will have great and lasting accomplishments.

If you feel polluted, wash out your bowl. Don’t break it.

Bowls that can be smashed are not the true bowls: just be an old person in a courtyard.

Facing My Wine

Here is a poem by Li Bai entitled “Diversions.”

Facing my wine, I did not feel the dusk,

or the falling petals cover my clothes.

Drunk, I stand, step, see the moon in the stream:

birds are distant and people are few.

Just be an old person in a courtyard,

savoring peace in a bustling city.

Close to midnight. The streets are still. The day’s demands are at an end—or at least temporarily at bay. An old man returns to his courtyard. A stonecutter laid out the pattern centuries ago, and the old man admires the workmanship each night. He feels right returning to the center of his universe.

His heart soars free. He notes where the moon is, to mark the journey ahead and to shape memories for years to come—memories that will well up in the quiet of future nights like this one.

Just outside, an old pear tree bursts into beautiful white blossoms at the end of winter. Weeks later, the petals fall to the ground in a fragrant snow. By early autumn, the tree hangs heavy with sweet, full fruit.

The old man sweeps the courtyard, thinking of monks who sweep their courtyards and recite sutras every day. The old man is willing to sweep, and in the sweeping find understanding and peace.

Wild monks of old wandered cloud-battered ridges in their search for enlightenment. Courageous sailors crossed thousands of surging waves to find routes to new lands. Nomad warriors galloped across continents to extend the will of their khans. The old man retreats to this little patch, studying what he sweeps away each week. That is good enough.

In the quiet, he listens to his heartbeat.

Savoring peace in a bustling city, the Great Immortal turned stones into sheep.

An Autumn House

We read “Autumn House on the Ba River Plain” by Tang dynasty poet Ma Dai (799–869) in relation to his disappointment over repeatedly failing the imperial examinations. The Ba River is near Xi’an: Ma is in the countryside, far from the glorious capital, and his alienation and sense of failure are clear. In the third line, he describes the trees with a term that means “foreign,” “nonnative,” or “far-off”—the trees aren’t like the ones in his hometown, emphasizing his estrangement and uncertainty.

After the wind and rain on the Ba River,

I see a flock of geese cross the night;

dead leaves drop from trees not like my homeland’s;

a lone man with a frozen lantern in the night;

an empty garden, white with dripping dew;

the solitary walls of a neighbor—a rustic monk.

Lodging so long in a small house on the outskirts . . .

How will the years send me on?

On Courtyards

A courtyard is a yuan, and the predominant kind is the Four Combinations Courtyard, or siheyuan. The history of these courtyards dates back at least two thousand years. Four buildings surround the courtyard with the gate usually at the southeastern corner with a “spirit wall” to block evil spirits.