To the tune of “Sand-Washing Creek”

Ill, try to rise. Wretched. Both my temples gone gray.

Lie down. Watch the waning moon climb the window screen.

Boil cardamom tips into a strong brew

and take it like tea.

Poetry books on my pillow, their words always good.

The scene before my door: lucky rain approaches.

All day long facing much fragrant comfort—

flowers amid thorns.

—Li Qingzhao (1084–1151)

The two solar terms within this moon:

SLIGHT HEAT

GREAT HEAT

the twenty-four solar terms

Depending on one’s latitude, full summer may already be in progress, and the weather can become quite hot. In southern China high wind and rain are common, threatening some crops. Typhoons are likely, and yet this is still a busy time for farming.

This exercise is best practiced during the period of 1:00–5:00 A.M.

1. Begin from a kneeling position, supporting yourself by pressing your hands on the floor behind yourself. Raise one leg and slowly stretch it in front of yourself until your knee is straight, then bend the leg and pull it back toward your chest.

2. Exhale as you push; inhale as you bend your leg. Breathe normally as you change sides. Extending each leg counts as one round. Repeat for fifteen rounds.

3. Sit cross-legged and face forward. Click your teeth together thirty-six times. Roll your tongue between your teeth nine times in each direction. Form saliva in your mouth by pushing your cheeks in and out. When your mouth is filled with saliva, divide the liquid into three portions.

4. Inhale; then exhale, imagining your breath traveling to the dantian and then swallow one-third of the saliva, imagining that it travels to the dantian.

5. Repeat two more times until you’ve swallowed all three portions.

6. Sit comfortably as long as you like.

Through this exercise, ancient Taoists sought to prevent or treat rheumatism in the legs and knees; excessive phlegm; asthma, cough, violent sneezing, and pain in the sternum; feelings of heaviness; loss of memory; and conflicting feelings of joy and anger.

It’s useless to worship gods.

It’s useful to worship gods.

Let’s be honest. If you look with any objectivity at religion, it just doesn’t seem to make sense. How can the gods be dressed in imperial Chinese robes? How can a particular god have a long black beard, while another one is clean-shaven? How can a god be living in a well, or a tree, or your kitchen, or inside a mountain? What does it mean that one god is a woman and another a man and another of unknown gender? None of it stands up to serious examination.

If you put out a basin of water on the night of the full moon, how does it become blessed? If you burn a bamboo-and-paper model of a car, how does your ancestor receive it? Where are your ancestors anyway? Where are the gods? Where are heaven and hell? How does incense carry prayers? How does a statue of a god stop floods? The fact is that this is all blind belief or superstition at best. Let us declare: the gods are fictitious.

Yet being fictitious does not necessarily equal being untrue. Fictional literature exists in all major cultures, and we value it not only for entertainment but for what it reveals of our lives. We reach universal truths through the channel of fiction, finding that a great work of literature, drama, music, or art can express truths that journalism or science cannot.

Following Tao means taking the seemingly awkward position of respecting and absorbing all that religion has to offer, going so far as to study it, celebrate it, and protect it, and yet knowing that none of it can be taken literally. It all has to be taken as a grand text, a way to read back into the beliefs of our forebears, a way to see what is archetypal about our psyches. It’s a way to acknowledge that we want to be pious and reverent—with the same strength and power with which we want to have friendships and fall in love—and that we find benefit in the act of worship.

It’s useful to worship gods—until you throw everything from your circle.

• Fasting day

If You Meet a Buddha

“If you meet a Buddha, kill that Buddha!” said the Chan master and founder of the Linji (Rinzai) Sect, Linji Yixuan (d. 866).

Followers of the Way: if you want to get an understanding that accords with the dharma, never be misled by others. Whether you’re facing inward or facing outward, whatever you meet up with, just kill it! If you meet a Buddha, kill that Buddha. If you meet a patriarch, kill that patriarch. If you meet an arhat, kill that arhat. If you meet your parents, kill your parents. If you meet your kinfolk, kill your kinfolk. Then for the first time you will be emancipated, you will not be entangled with things, and you will pass freely anywhere you wish to go.

Throw everything from your circle!

Tao remains when else is gone.

Draw a circle around your life. Then throw everything out of it. Your computers and mobile devices, your televisions, radios, books, magazines, and newspapers. Throw out your clothes, your car, your latest beloved gadget.

Throw out your awards, your money, your aspirations—and your demons and devils too. Throw out your gods, throw out your history, throw out your culture, throw out your ethnicity, throw out your ancestry, throw out your parents and your children, throw out your pets, throw out your friendships, throw out your most treasured memories—and throw out the injustices and hurts and hatreds that have been hurled at you and that cling to you like gigantic leeches.

Throw out the pride in your body, throw out that image in the mirror, throw out your need to survive, throw out your hunger—and throw out illness, injury, accident, fear, and death.

Throw out your language, throw out your dance, throw out your science, throw out your groping and your touch—and throw out lies, deceit, mistakes, clumsiness, awkwardness, stupidity, and ignorance.

Draw a circle around yourself and throw everything out. Throw everything out and then throw yourself out of the circle too!

What remains?

If we say “something” remains, we are wrong. How language betrays us! How language wants us to talk about things! What remains is not solid, not subject to time, not confined to location, and yet we sense it in our circle, sense it with a perception that is not one of our senses.

We sense because we are that which we sense, and that which we sense has, without senses, awareness of itself. That self is what the universe is and is not. That self is what there is, and there is nothing else.

The circle is drawn in a place—but both sides of that line are one and the same.

Tao remains when else is gone, so throw everything away.

Nanquan Draws a Circle

Case 69 of the Blue Cliff Records gives this story:

Nanquan, Guizong, and Magu traveled together to pay their respects to National Teacher Zhong.

Stopping halfway through the journey, Nanquan drew a circle in the dirt and said, “If you can say a word, then we will go on.”

Guizong sat in the middle of the circle.

Magu bowed from the waist.

Nanquan said: “Then I will not go!”

Guizong said: “What’s going on in your mind?”

Throw everything away:

Mountains and streams remain.

Stay, if you will, in this state where you have thrown everything out of your circle. What you cannot throw out is whatever was outside your circle. What is outside your circle is Tao.

Stand at the base of a mountain and see how its greatness was thrust up in a mass our cities could never accumulate. Absorb the mountain’s lesson of stillness, of presence, of lasting.

The rivers flow forever from the highest ground to the lowlands by the sea. Poets have written tributes, but the poets are gone. Warriors shed blood fighting over the river, but the water runs clear. Nations set boundaries by the river, but no one remembers those names while standing in the current.

We have perpetuated disappearances: we have polluted the waters and destroyed our fellow creatures. The Baji river dolphin lived only in the Yangtze River. Today, it’s extinct. Rivers all over the world have been polluted by factory wastes and made sluggish by the dregs of our civilization. One can almost see the winter floods as angry attempts at purification.

Let us stop polluting the world and each other with our carelessness. Let us see how nature gives us all that we need, and that the right response is reverence and respect. The lakes brim every year. The surrounding streams run into them. The hillsides sink toward them. The animals all come to drink. The fish swim and spawn. And no matter what, the surface of the lake is always one way: level. The wise person needs no other remembrance.

Throw away everything. Then go outside. The mountains and streams remain.

Mountains and streams remain part of a cycle, like the snake turning to bite its tail.

Rivers and Lakes

The phrase “rivers and lakes” (jianghu) means to travel around the country. It also means a vagrant, a wanderer, or an itinerant professional.

Wuxia

Recently, the phrase has been used in martial arts movies and in the martial-literary genre known as Wuxia (Chivalrous Heroes).

Earlier Appearances of the Term

In the Song dynasty, Fan Zhongyan (989–1052) used the term in his essay commemorating Yueyang Tower in Yueyang, Hunan. (He was also the teacher of Ouyang Xiu) After Fan criticized the chief councilor, he was demoted and his proposed reforms failed.

Fan wrote of the ancients he admired: “When in a high position in court, they were concerned about the people. When living by distant rivers and lakes, their concern was for the emperor.”

The Zhuangzi, which dates to the fourth century BCE, has a parable in which Zhuangzi reproaches a man who did not know what to do with the large gourds he had grown: “Why did you not think of making them into large vessels, so you could have floated over the rivers and lakes?”

The snake turning to bite its tail.

Reject Tao and you will find Tao.

What of that circle you drew? What of that line, which has a presence but has no width, no depth, no solidity? Follow that line around again, follow it and walk it around and around. You’ve found Tao, and yet, when you follow Tao for an entire lifetime, you find that Tao turns back on itself, that the end is the beginning, that the beginning is the end, and that, in actuality, there is neither beginning nor end.

We are on this journey through a lunar year, but the statement that there is a new year and an old year is a mere concept we use to shape our understanding. The moon doesn’t care what phase it’s in. It hasn’t kept tally of the number of times it’s turned since the beginning, and it doesn’t number where it is in relation to the sun and the earth. The moon doesn’t know of the seasons that we experience here on earth. The moon revolves and follows its orbit, and its Tao that is part of the great Tao. It completes its circle, and its circle is constant and eternal.

It’s we who measure and mark and seek repetition. We take comfort in that. Primitive humans stuck poles in the ground and learned to understand when the sun and moon would seemingly return in fixed patterns. Slowly they formulated the ideas of day, month, and year. We discovered cyclical movement, and we learned to depend upon it. If not for the circle, both our minds and our civilization would collapse.

Tao is the greatest circle of all. Try to escape it, and you cannot, for it is the knowable and the unknowable. Study it and you find that Tao is the circle that connects everything. Try as you might to get off the circle, you will only find yourself on it again.

Reject Tao, and you will find Tao when you add things back in.

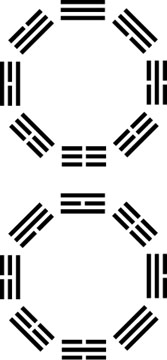

The First Trigram of the I Ching

The I Ching includes eight basic symbols called trigrams. The first of these trigrams consists of three unbroken lines and is called Heaven (Qian). The I Ching explains the qualities associated with it:

Qian is

the sky,

a circle,

a ruler,

a father,

jade,

metal,

cold,

ice,

deep red,

a good horse,

an old horse,

a thin horse,

a piebald horse,

the fruit of trees.

The trigrams are arranged in either of two circular formations:

Thus, heaven, which is circular, takes its place in a greater circle. The overall patterns are called the Eight Trigrams (Bagua).

When you add things back in,

Their meaning will be clear.

Once, an artist said to the admirers visiting his studio that everything should be orderly and not a single extra thing should be in that room. “Take everything out of the room,” he advised, “and then only bring in, one by one, what you absolutely need.” His studio was indeed a model of order infused with the vitality of minimalism.

We should do the same thing with our lives. In fact, we are like that artist’s studio—a sacred space, scrupulously white, bathed in light, at once a shelter and a launching pad, at once a temple and the entire universe, at once defined dimension and endless possibility. For we, like the artist’s studio, are located in this infinite cosmos, and yet we are the cosmos entire.

How the glittering stars fill our night skies with the very image of profusion—and yet how the stars occupy their own set places at vast distances from one another. It would seem that all that is there is meant to be there, as if “given” its own proper place. We can arrange our lives in the same way, and it is up to us to bring back into our sacred space only what we need, only what pleases us, only what makes us whole and strong.

Space itself is pure, clean, the stuff of possibility. As we move things—not necessarily the material but the defined—back in, let them meet the criteria of space itself. Let every thing we put back in our lives be pure, clean, and the stuff of possibility. Then we will never lament that our lives are meaningless, because we will have filled them only with meaning.

Their meaning will be clear, so clean your house, invite the gods in.

Mountains Were Mountains . . .

Chan master Qingyuan Weixin (c. ninth century) said:

Before I studied Chan for thirty years, I saw mountains as mountains, and waters as waters.

When I gained a more intimate knowledge, I reached a point where I saw mountains not as mountains and waters not as waters.

Now that I have gotten to the substance, I have reached a point like before: I see mountains merely as mountains and waters merely as waters.

Clean your house, invite the gods in,

all is at peace, all is now clear.

On this day, monks and temple caretakers put the sutras out to air, preventing mold and must.

Then they take the sacred books back inside.

In the same way, take your cherished books out too. Bring them into the sunlight both literally and figuratively. Air them, for to leave a book on a shelf unopened is a travesty. Review them too, for to slavishly keep books you’ve outgrown is equally wrong—why not pass them on so that others may find the same way you did?

We value books. Yet the author is not there with you. If you accept that point, then can we dare to say that we can have the gods in our lives—even though the gods are no more with you than the authors of your books?

Su Dongpo the poet, Beethoven the composer, Laozi the sage, Homer the bard, Guan Yu the god of martial loyalty, Einstein the physicist, Gautama the Buddha, Shakespeare the playwright, Wang Xizhi the calligrapher—all of these people are dead and nowhere to be found physically, psychically, or mystically in our lives today. Not a trace of their bodily lives is present—yet they affect us nevertheless. What do you call that?

We forget things all the time. As our world changes, we also change and adapt, discarding what is no longer useful. Clearly the ability to forget is of vital importance as we either let go of traumas or distill them into vital strands of wisdom painfully won. Perhaps, in the same way, you no longer believe in the gods you embraced during your youth. You see them now as fairy tales, or mere habits passed down by your parents. The question is, what knowledge and what gods serve you now?

So take our your sacred books and air them today. Take out your gods too, and make sure they still have a place on your altar.

What’s important is what remains.

All is at peace, all is now clear: why reject filial piety?

• The Basking and Bathing Festival

• Heavenly Bestowal Day

• Airing the Sutras Day

Observances of the Sixth Day of the Sixth Moon

There is no single large celebration for this day, but there are several small and local observations.

The Basking and Bathing Festival (Xishai Jie) is a day to air bedding, clothes, and books in the sun.

Heavenly Bestowal Day (Tiankuang Jie) originated with Qin Shi Huang and the tradition he began of making sacrifice on Taishan. During the reign of the Song dynasty Emperor Zhengzong (968–1022), Taoist scriptures appeared that were said to have come from heaven, and the emperor marked the occasion with imperial sacrifices at Taishan. He later decreed the deification of the Jade Emperor as the highest ruler of heaven.

Airing the Sutras Day (Fanjing Jie) is a Buddhist observation. Sutras in the temples are aired to prevent mold. According to legend, when Xuanzang returned from India with Buddhist sutras for translation, some fell into the water, and he rushed to dry them.

Reject filial piety

and you will find your family.

You might think it’s a trick by now. “Sure, throw out everything but then take it back in. It’s just the bait to get us to accept the same old traditions.” But no, the real point is this: we should only keep that which is necessary to our lives. We cannot keep the moribund traditions and exhortations of our elders. We keep what is fresh, alive, and needed.

The lunar calendar is built on agriculture, but it is also built on family. Do we really need family? For many of us, family, like religion, has been dysfunctional.

Every day we hear news about families torn apart by divorce, infidelity, poverty, mental illness, and ignorance. Every day, we also hear stories of noble sacrifice, of a husband who dies shielding his wife against a tornado. Or a mother who works three jobs so her children can go to college. Or a sibling who becomes the parent to orphaned brothers and sisters.

What keeps family together is the power of blood, the power of love, the power of acceptance. That power is mysterious. That power is spiritual. That power connects us to a force and a magic greater than just who we are as individuals. That power sustains and protects us. It is that power that we want to get in touch with.

If you have a good family, value it. If you have a bad one, leave it and build a better one. The duties that Confucius prescribed were merely guidelines, dry form to surging and vital force. Throw out all the lessons of Confucius and yet there is still that living, breathing, pulsing energy that is family. And that spiritual energy is what must be honored.

And you will find your family vital—the more times change, the more we need wisdom.

Zhuangzi on Confucius

Zhuangzi portrayed a fictitious situation where Confucius went to see a person named Dao Zhi, who rebuked him:

The more you talk, the more nonsense you utter. You get your food without plowing and your clothes without weaving. You wag your lips and move your tongue like a drumstick. You arbitrarily decide what is right and wrong, leading the princes throughout the kingdom astray, and distract scholars from their proper business. You recklessly set up filial piety and fraternal duty, and curry favor with the feudal princes, the wealthy, and the noble. Your offense is great; your crime is extremely heavy. Go home at once!

The more times change, the more we need wisdom.

When we need wisdom, we need the spirit.

The contrast between the antique imagery of all the world’s religions and our everyday life of computers, phones, cars, airplanes, televisions, and industry is obvious. The China from which Taoism came was as filled with innovation as our world today. Dozens of inventions came out of ancient China—all while the spirituality that we now study was developing. In fact, we wouldn’t even know about much of Taoism were it not for the inventions of paper and printing with movable type. We are conversing at this very moment via the latest developments in technology and communication; we are conveying ancient ideas and old calligraphy by way of pixels.

So there need not be any contradiction between modern life and spirituality. We dress, eat, work, and raise our families using all our current lives have to offer. Ignoring that is simply to be out of step with the times. We use all we have to support our spirituality too: we have to understand modern nutrition and sanitation, avail ourselves of all that medicine has to offer, use technology to find the ideas that will sustain us. There may be drawbacks to modern life—by definition, there are drawbacks to everything. However, drawbacks are not negations or reasons to refuse progress.

The great innovations of one era become commonplace in the next. No matter how much we innovate and invent, we use our inventions to point back to ourselves. It’s the wisdom and spirit that are paramount. The innovations are mere means.

When we need wisdom, we need the spirit, so grasp a sword to cleave ignorance.

• Fasting day

Chinese Inventions

In ancient China there was constant invention and innovation. The spiritual systems we view as traditional today were also developing and evolving, as they continue to evolve today. Here is a partial list of innovations known in ancient times:

paper; printing with movable type; bookbinding; ink

gunpowder; bombs; chemical warfare; crossbow; flamethrower; land mines; trebuchet catapult; coffin

plowshare; cultivation of rice, soy, millet and other grains; heavy moldboard iron plow; horse collar and harness; wheelbarrow; winnowing fan; stirrups

noodles; tea; tofu; toilet paper; silk; porcelain; lacquer; celadon

calendar; compass; armillary sphere; seismometer

bellows; belt drive; blast furnace; borehole drilling; chain drive; crank handle; finery forge; rotary fans; trip hammer

acupuncture; inoculations

matches; fireworks; flares; rockets

fishing reel; rudder; oar; leeboard

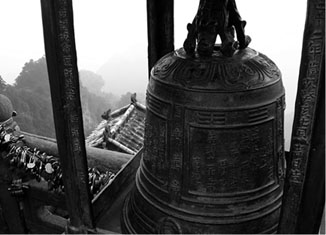

bell; tuned bells

chopsticks; fork

automatic doors; mechanical theaters; mechanical cup-bearers and wine-pourers

cast iron; steel

contour canal; suspension bridges using iron chains

archaeology

kites

Grasp a sword to cleave ignorance.

One thrust—the heart comes to a point.

Not many people are interested in swords these days. Perhaps you’ve seen one in a museum, perhaps you’ve watched movies where fantasy characters wield outlandish blades. Maybe you’ve played a digital game or two with sword fighting. That may be the extent of it. Taking up an actual sword is unlikely. You might even be horrified by the idea of holding a sword, thinking of it only as an instrument of slaughter, a tool of savagery that should be left behind in medieval times.

Yet the sword is a constant theme in spiritual imagery. Lu Dongbin is depicted with a sword. The Door Gods are shown with swords. Statues of guardians with swords adorn many Buddhist temples. Here we are in this modern world, where people don’t engage in personal combat with swords, yet we still use them as symbols.

Using a sword as a spiritual implement is an exercise in mental focus. Think of someone writing calligraphy—in midair, without ink. The swordsperson tracks the path of the sword as a means of contemplation, projecting mental concentration beyond the body and mind into the outside world. The sword makes many movements that together form small paths. Following those small paths leads you to the grand path that is Tao.

A sword is a weapon, and a weapon is for killing. Any implement for killing is inauspicious and should only be used as a last resort. It is said, “A sword is never unsheathed without tasting blood.” Therefore, if you would not kill, your sword should not be unsheathed, and of course, killing is evil and wrong.

Put down the sword of killing. Renounce it completely. But don’t overlook the sword of spiritual practice that we use to discipline ourselves. A sword used in this way is not a weapon. It has been purified into a tool of meditation. Where the killing sword is fed by blood, a spiritual sword is purified by the essence of its user.

One thrust—the heart comes to a point, and we slay ignorance with the sword.

Delight in the Sword Fight

Zhuangzi speaks to a king about three kinds of swords:

The King’s Sword has Yanqi and Shicheng as its point; Qi and Daishan as its edge; Jin and Wei for its back; Zhou and Song for its hilt; Han and Wei for its sheath. The wild tribes protect it; the four seasons encircle it; the Bohai Sea surrounds it; the enduring hills belt it. The Five Phases regulate it. Its principles are punishment and virtue. Its unsheathing shows yin and yang. Grasp it in spring and summer; move it in autumn and winter. Thrust it—nothing stands before it. Raise it—nothing is above it. Lay it down—nothing is below it. Swing it— nothing escapes it. Above, it cleaves floating clouds. Below, it penetrates to the foundation of earth. Use this sword just once and the princes will be reformed and the kingdom will be rectified. . . .

The Feudal Lord’s Sword has wise and brave officers for its point; pure and honest officers for its edge; worthy and good officers for its back; loyal and sage officers for its hilt; valiant and eminent officers for its sheath. Thrust it—nothing stands before it. Raise it—nothing is above it. Lay it down—nothing is below it. Swing it— nothing escapes it. Above, it takes its law from round heaven and obeys the three lights; below, it takes its law from the square earth and accords with the four seasons; inside, it is in harmony with the will of the people, and it brings peace to the four quarters. Use this sword just once and thunder will peal and shock. Within the four borders no one will fail to respectfully submit and obey the commands of the ruler. . . .

The Commoner’s Sword is used by those with tangled hair, bristling whiskers, slouching caps with long and dangling tassels; who wear coats cut short behind; who have glaring eyes and speak hatefully. They clash together before you. Above, they chop at necks; below, scoop at liver and lungs. These are the swords of the commoner. They are no different than fighting cocks. Every dawn brings death. They are of no use in affairs of state.

Now your majesty stands as the Child of Heaven. Approving of the Commoner’s Sword is unworthy of a great king.

160 The Blade Leads the Breath

We slay ignorance with the sword

and face our opponents: us.

The theory of the sword speaks of leading the breath. The breath—qi—follows the movements of the sword. One uses energy to move the sword, and also feels one’s energy following the sword.

We say that we feel energetic. We say we have to eat well in order to have enough energy. We might appreciate the visible energy of an athlete or dancer. But in our common terms, we don’t go much further than that.

The swordspeople and the sages, however, not only speak of energy as a force but believe that force can be increased, channeled, and concentrated to do extraordinary things. Whether it is used for the graceful wielding of a sword or the powering of meditation is a matter of a person’s preferences. The energy is the same.

In practicing with a sword, then, it takes energy to thrust, parry, slash, and cut. But one learns to direct one’s energy precisely into those movements. As with any other skill, the more one practices, the more efficiently one’s energy moves in those patterns.

We don’t use swords as weapons anymore, but working with them is still valuable as a way of practice. What the sword truly teaches is courage, precision, positioning, movement, and grace. Who among us does not need these?

When the sword cuts, it parts yin and yang. Practice that each day and you open the road to profundity.

And face our opponents: us. Our ambition is to act with great force.

Quotations from the Taiji Classics

Taijiquan, the slow-moving exercise frequently seen performed in parks, is a complete system of martial arts and includes not only the exercise but fighting techniques and weapons practice as well.

Here is a selection of quotations from the Taiji Classics:

Be calm and steady and lead the qi with your mind.

When the spirit is fully aroused, there will be no fear of tardiness or clumsiness.

Poise your body like a hawk ready to dive upon a rabbit, make your spirit as alert as a cat ready to spring upon a mouse.

If you don’t move, be as still as a mountain. When you move, be as fluid as a river running down a slope.

The mind is the general’s order. The qi is the signal flag. The waist is the lieutenant that directs the operations.

The qi is the spokes and rims of a wheel; the waist is the axis.

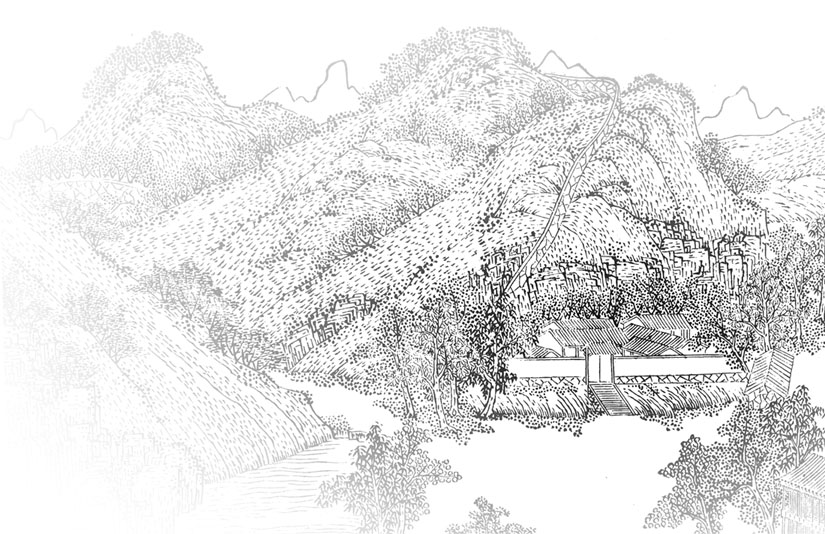

A Taoist practicing the sword on Wudangshan. The words on the temple wall—fu, lu, and shou—mean “happiness,” “prosperity,” and “longevity,” and represent the Three Stars.

© Bernard De Poorter

Our ambition is to act with great force—

when great force is already under us.

Falling can be the simplest act. Perhaps we should make use of it. In good martial arts schools, falling—yes, there are sophisticated techniques for it—is taught before punching and kicking. It makes sense. If you’re going to fight, you’re probably going to meet good opponents, and if you meet them, they’re going to knock you down or throw you. You have to know how to fall.

After that, it’s important to know how to stand. Martial arts places great emphasis on stance—but what is stance but a skilled way of “falling” too? The masters talk about being “rooted” to the ground, but what they’re really talking about is being solid, with a low center of gravity. The most stable thing is what has already fallen and sits there without resistance. The key to a good stance is to be relaxed and low—using gravity instead of resisting it.

Thus, the teachers will constantly urge their students to “sink.” This not only means squatting deep into a stance, but it also means letting all your strength and intention sink down, making yourself heavy and stable and not betraying yourself with fearful tension and flighty apprehension.

But what about kicking, hitting, moving? Why not let gravity help? After all, even the most gigantic man is weaker than gravity. Instead of going our own way with our own puny force, it’s better to avail ourselves of the great forces. We generate force from the floor, using gravity not just for stability but to push against.

If we understand the dynamics of falling, then we can make our opponents fall. If we understand the importance of sinking, then we can remain standing.

When great force is already under us, we hold both the tool and template.

Zhuangzi on the Full Understanding of Life

Zhuangzi tells the story of a drunken man falling from his carriage. He might be hurt, but he will not die. Although his bones and joints are the same as those of other men, his spirit is whole.

The drunk is unaware of getting into the carriage or of falling from it. Thoughts of death or life, alarm or fear, do not occur to him. He meets danger without shrinking from it and emerges unscathed because he is completely relaxed and at ease.

Zhuangzi asks how much better it would be if the man was not drunk but imbued with heaven: the sage who is filled with heaven cannot be injured.

We hold both the tool and template

and we reshape our minds’ pattern.

The earliest woodworking tools were not much different from knives and swords. In fact, one of the first planes was like a spearhead, and knives are used to mark and whittle. Axes were used to fell trees, and they were also used to shape the wood. Eventually, this led to the adze, and perhaps the adze led to the chisel. A plane is nothing more than a thick blade set in a block, and even a saw is arguably a set of tiny chisels set in a line.

At first the role of blades was general and undifferentiated. Specialization came later as needs and ingenuity evolved. We needed spears and swords to hunt and fight. We needed blades to skin animals and cut the meat. We needed ax heads to chop wood and shape the most basic supports for shelter.

Therefore, it is natural that we use tools. And it is natural that as these tools developed, they took on our spiritual intentions as well. The swordmaker used ritual purification and engaged in ceremonies to empower the sword. The blacksmith who made tools did the same. The Classic of Lu Ban mentions charms and spells a carpenter can use to bring either good or bad fortune to the occupants of a house.

There is an interesting contrast in Western and Asian tool use. Western woodworkers push their saws and planes. Asian woodworkers pull theirs. In the end, it’s a matter of the woodworker’s skill. Neither pushing nor pulling in itself provides greater advantage. But doesn’t it show that how we use tools proceeds from our minds?

The sword develops and leads our energy. All the tools we use develop and lead our energy. They express our minds.

And we reshape our minds’ pattern, saying, “I am the Dragon King.”

Carving an Ax Handle

This is a poem often quoted from the Classic of Poetry:

How do you carve an ax handle?

Without an ax it cannot be done.

How do you gain a wife?

Without a matchmaker it cannot be done.

Over the centuries, this poem has taken on a number of interpretations. The most common one is that the pattern for anything we need to do is close at hand. Being unable to carve an ax handle without using an ax means that all the knowledge we need to do our work and live our lives is already at hand.

Another implication is clearly one of process: one uses an ax to make another ax handle. One needs a matchmaker to organize the process of marrying. This refers again to the understanding of fundamental patterning, the need to make something new from that pattern, and a subtle recognition of professional ability.

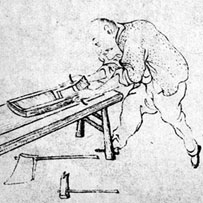

Lu Ban (507–440 BCE) is the God of Carpenters and Artisans. He was also an engineer, philosopher, inventor, strategist, and statesman. His wisdom is collected in the Classic of Lu Ban (Lu Ban Jing).

Lu Ban was a contemporary of Mozi (c. 470–391 BCE).

Mozi was a philosopher who opposed both Confucianism and Taoism. He was also a carpenter and inventor who created mechanical birds and siege ladders with Lu Ban.

The Classic of Lu Ban discusses all forms of carpentry, giving design and construction details for nearly every conceivable carpentry need. Houses, palaces, temples, furniture, small objects, and farm items ranging from sheep pens to foot-operated waterwheels are all detailed. The book integrates the practical knowledge of craft and design with geomancy, talismanic writing, the correct selection of auspicious days for all phases of building, and the ways to curse or bless the occupants of a newly built house. There is advice on how owners can neutralize any sorcery by the builders, how they should move into the house, and how they should consecrate their altar to best invite the gods into their new home.

Lu Ban’s biography gives special mention to his wife, Lady Yun. Her skills are described as “heavenly,” and the objects she made are reputed to have been even more beautiful than Lu Ban’s. “Husband and wife helped each other and thus were able to enjoy great and everlasting fame.”

Lu Ban frequently asked his wife to help hold pieces of wood on his workbench. She showed him how a stake of wood (bench dog) set in the bench could take the place of her hands, and this stake is still called ban qi—“Lu Ban’s wife.” He also asked his mother to help hold the other end of his ink line until she suggested a wooden hook, and today this part of the tool is still called ban mu—“Lu Ban’s mother.”

There are still temples to Lu Ban, such as the Lo Pan Temple in Hong Kong. As one of the two ministers of public works under the administration of the Jade Emperor, Lu Ban continues to be worshipped by carpenters and varnishers today.

The Lu Ban Rulers

Lu Ban stated that roundness was the shape of Heaven and squareness was the shape of Earth. However, the “ten thousand generations all over the world” could not match his understanding. Therefore, he advocated use of the compass, the square, the level, and the ink line to help in the building of palaces, houses, ships, carriages, and other projects.

Two rulers shown in the Classic of Lu Ban are drawn below. The shorter ruler forms one leg of the carpenter’s square (quchi) and is divided into ten units named after colors. The longer one is called Lu Ban’s True Ruler (Lu Ban Zhenchi), measures about forty-three centimeters, and is divided into eight units whose names have good or bad meanings. The rulers were primarily used to measure doors, but they were also used in all other areas.

Carpenters still keep this square and ruler as ritual objects. Taken as symbols, they express the wish for all tangible things to be aligned with spiritual principles.

Feng Shui

The carpenters of the Classic of Lu Ban were thought to have extraordinary powers. When building a house, they had to choose auspicious days for every act, from cutting down trees to beginning the building to raising the ridgepole. The book also gives instructions on how to curse the occupants of a house with hidden charms and talismans, how to bring fortune using other charms, and what rituals to use during construction and when the house is completed.

Furthermore, the very siting, direction, and architecture of the house could be either auspicious or inauspicious, and the book gives a catalog of both types. This was geomancy—feng shui—as design from the ground up.

I am the Dragon King:

human and animal.

The voice of the Dragon King said: “I am every animal combined with the human. You aren’t like me, but you are in awe of me. All animals submit to me because I am all of them combined. All humans are in awe of me because I live in every body of water, I am the veins in mountains, I bring the rain. I am everywhere—acting, creative, fecund, powerful, and eternal.

“I am the Dragon King. At one time, I was worshipped everywhere. Now people think of me as a myth. That’s how a king should be. A king is not common. A king is not seen every day. Laozi says that ‘the greatest ruler is one that people don’t know exists.’ You say you don’t know if I exist. Yet I lead everything. You make effigies of me for your parades and your celebrations. You decorate your buildings, paintings, and clothes with my image. You dub your sports teams after me. You name companies, games, movies, stories, restaurants, and heroes for me. Have I ever ceased to fire your imaginations?

“I am the Dragon King. You, sitting there in your garden, by a pool or a well—I am right there with you. You, on the parched plains yearning for rain—you ask me to come save you. You, trembling as the thunder rolls, cowering in a cellar as the lightning strikes—you fear me. You, standing at the beach, looking at the waves, wondering what is under the surface where your mortal eyes cannot see—you sense my empire.

“I am the Dragon King. I am animal made human. Human made animal. In so many ways, you fantasize about being just like me. It is possible. That’s a secret few know. But I am a king and I can only leave you with this pronouncement, this challenge: can you, woman or man, child or elder, find the day where you can stand against the swirling sky and declare: ‘I am the Dragon King’?”

Human and animal, even if you unify your entire being, what you learn in art can never be used.

• Birthday of Lu Ban

• Commemoration day of the Dragon King (Long Wang)

The Dragon King

The dragons of Chinese belief live in pools, wells, rivers, lakes, and seas. They are considered the kings of animals, and so became emblems for the emperor. Furthermore, dragons bring beneficial rain and are regarded as the embodiment of nature’s fecundity.

A dragon has been described as having the head of a horse or camel, the horns of a deer, the ears of an ox, the eyes of a devil, an abdomen textured like a cockle, the scales of a carp, the tail of a snake, and wings on its sides. It has four legs with feet that combine the claws of an eagle with the soles of a tiger. An imperial dragon has five talons on each foot, while an ordinary one has four.

Since there are dragons everywhere, there is no single dragon king, although there are many stories about and many temples to individual local dragon kings. A dragon king has a human body, robes like an earthly emperor, and a dragon head. He can take full human form or change completely into a dragon.

Dragon kings live in palaces deep underwater, commanding ministers, generals, and soldiers that are human sized aquatic animals like fish, shrimp, and crabs.

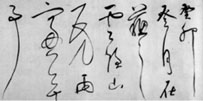

What you learn in art can never be used:

if you give in, it’s called imitation.

It’s maddening to be an artist. Learn mathematics, for example, and you can reliably memorize your multiplication tables, postulates, theorems, formulas, and proofs. Then you can build upon them, never again wondering what the sum of one plus one might be. Music is the same. You learn the scales, the chords, the rhythms, and while there are infinite variations, the notes never alter.

Not so with art. As soon as you get good at it, the teachers immediately mock what you do. “Oh, so you’ve learned to paint like so-and-so. What are you going to paint?” Writing is the same. If you use the same phrases or rhymes as another poet, you’re ridiculed as derivative or clichéd. It was fine for the first person to use a brilliant metaphor, but nobody else attempting to use the same words receives any admiration.

Art is a Tao. It is a way of exploration, creativity, and searching. You have to work at it every day. Write every day. Sing every day. Paint every day. Whatever your art form, you have to do it every day. Most of what you’ll make will be unusable. If you’re really searching and probing, you will have many failures. Making a lot of beautiful things that are like a lot of other beautiful things is manufacturing, not art.

Your mind is a wilderness. You’re an explorer along the frontier. You run into dead ends, box canyons, sheer cliffs. You try mining, and the vein runs out. You drill for water, and sand runs through your fingers. You hack at the weeds, only to find stone. You keep trying, sweating under the sun, woozy, feeling abandoned—bitterly noting that even the vultures aren’t willing to circle you. And yet, you will never abandon the effort.

Art is its own Tao. All that counts is staying on the Way. If you keep going, day after day, sooner or later, you’ll cross that wilderness and find a paradise. And it will be yours alone.

If you give in, it’s called imitation; be creative and use anything, whether it’s old or new.

• Fasting day

Dong Qichang

Dong Qichang (1555–1636) was a painter, calligrapher, connoisseur, critic, and Chan Buddhist. He led a group of scholars and artists that formulated the principles of literati painting, and whose works had a lasting influence on the Chinese and Japanese art that followed. Dong Qichang is considered one of China’s great painters, and his landscape paintings and his calligraphy are justly famous.

Tokyo National Museum

Dong Qichang believed in tradition and in mastering the styles and techniques of the masters. However, he warned against “studying the ancients without being able to change.”

Use anything, whether it’s old or new.

Honor it and pass it on after you.

If you’re both fortunate enough and so inclined, you have antiques in your home, things made by craftspeople long gone. Your mother’s china, perhaps, or a wooden chair; an old piano or old books.

All these things were made by craftspeople who intended that the objects they made outlive them.

Take an antique chair, for example. The wood is probably of a kind that can no longer be found—dense, hard, old growth. The joints were put together to take the weight of a person, even someone rocking on two of its legs, or standing on it to hang a picture. Probably the joints are mortise and tenon—the same kind found in the oldest Egyptian furniture. These joints are archetypal, universal, used the world over. They have no ethnicity, no culture except the culture of the craftspeople who make things that challenge mortality.

If you have such things, use them. Keep them out of the cabinet or warehouse. Let children play with them. Sit on the chair, cradle the silver knife in your fingers, make the piano sing, use the book to go back in time.

If you don’t use these things, then you dishonor the craftspeople who made them.

What if they break? What if they wear out? That’s the challenge that the craftspeople took on. What if they don’t break? Then you have had the honor of being the caretaker of beloved things, and you hope that they outlive you too.

Honor it and pass it on after you; carefree, you’ll plant trees and build your own house.

• Fasting day

The Three Zithers of Ouyang Xiu

Ouyang Xiu (1007–1072) was a noted leader of literary stylists who revived the ideals of ancient writing. He was one of the Eight Masters of Tang and Song Prose.

In this famous essay, he writes about the seven-string zithers (qin) he is fortunate enough to own. Each one shows exquisite craftsmanship and is well constructed. They are old. The lacquer on each of them is reticulated, a pattern he says only develops after a hundred years.

He knows the makers. The zither with gold studs was made by Zhang Yue and has a tone that is “rich and penetrating.” The one with stone studs was made by Lou Ze and has a sound that is “pure and gentle.” The one with jade studs was made by the Lei clan and has a tone that is “harmonious and resonant.” Ouyang Xiu writes: “At present, anyone who owned a single one would treasure it. I now own all three.”

These zithers were fretless, and the studs helped the placement of fingers. “It is hard for an old man with failing eyesight to place his fingers on those studs,” he writes, adding that since the stone studs do not shimmer, “stone-studded zithers are best for old men.”

“One need not learn many zither pieces,” he concludes. “The important thing is to enjoy playing. Likewise, it’s not necessary to own many zithers. But since I have come to own this many, it would be foolish to worry about having too many and to let some go.”

the twenty-four solar terms

These are likely to be the year’s hottest days. Wind may be slight and in some areas the humidity may be high, making the weather stifling.

Those farmers who plant two crops of rice must quickly harvest the early rice and plant the late rice. A delay in planting can mean a smaller yield or a failed crop.

Health problems from the heat are a danger for the young, the weak, and the elderly, so it’s important to keep these populations cool.

This exercise is best practiced during the period of 1:00–5:00 A.M.

1. Sitting cross-legged, close the fists tightly, with the thumb inside the fingers and rest them on the floor before you.

2. Turn the head from side to side, “like a tiger,” for fifteen repetitions on each side.

3. Facing forward with your hands resting on your lap, click your teeth together thirty-six times. Roll your tongue between your teeth nine times in each direction. Form saliva in your mouth by pushing your cheeks in and out. When your mouth is filled with saliva, divide the liquid into three portions.

4. Inhale; then exhale, imagining your breath traveling to the dantian and then swallow one-third of the saliva, imagining that it travels to the dantian.

5. Repeat two more times until you’ve swallowed all three portions.

6. Sit comfortably as long as you like.

Through this exercise, ancient Taoists sought to prevent or treat rheumatism in the head, neck, chest, and back; cough and asthma; thirst; feeling of fullness in the chest; pains in the arms; excessive heat in the palms; pains above the navel or in the shoulder and back; hot and cold perspiration; diarrhea; and depression.

Carefree, you’ll plant trees and build your own house,

water the garden and grow your own food.

Having a garden is a beautiful dream. If you have a garden—even if it’s a few potted plants on a balcony or patio—you know its pleasure and tranquility. If you have a larger garden you can walk in, so much the better. Or perhaps you’re one of the lucky few who has a big garden, and professional gardeners, and who knows the passion of planning and the hard work of planting—and also the grand feeling of sitting in your own retreat, sighing in relief, and letting the hours dribble away without concern.

The Taoist reverence for nature takes on its own form in a garden. Although someone may call him- or herself an owner, a garden may well outlive its owners. In fact, the great gardens are almost never achieved in a single generation. It takes many generations to make a garden—the wealth required is significant—and many of the trees won’t even come to maturity in the lifetime of the first owner. Each owner is merely caretaker of a dream.

The owner ends up being owned by the garden—the plants must be watered and fed, tree limbs must be staked up, ponds must be cleaned, glorious rocks must be searched out and brought in at great labor and expense. The owner almost becomes a worried slave—but a few moments in the garden, perhaps in a vine-covered arbor where the shade is cool, always convinces the gardener that every bit of toil was worth it.

Water the garden and grow your own food, and put aside all contrivances.

The Humble Administrator’s Garden

The Humble Administrator’s Garden (Zhuozheng Yuan) is the largest garden in Suzhou, a city famous for many lovely gardens.

The garden was originally the residence of a Tang dynasty scholar, Lu Guimeng (d. 881). In the Yuan dynasty, it became the monastery garden for the Dahong Temple. In 1513, Wang Xiancheng, a poet and imperial envoy, appropriated the temple and retired there after long persecution by the East Imperial Secret Service.

He began work on the garden in collaboration with the Suzhou artist Wen Zhengming (1470–1559). Wang took Tao Yuanming’s rejection of official life as one of his principles. The garden’s name was inspired by Pan Yue, a writer of the Jin dynasty: “I enjoy a carefree life by planting trees and building my own house . . . I water my garden and grow vegetables to eat . . . such a life suits a retired official like me.”

The garden was completed after sixteen years, in 1526. Unfortunately, Wang lost the garden gambling, and it changed hands many times thereafter.

The painter, poet, and novelist Cao Xueqin lived in the garden as a teenager, and it is believed that the famous novel Dream of the Red Chamber takes its garden settings from the scenery Cao knew so well.

Put aside all contrivances:

open the gate; open your heart.

There’s something especially attractive about a garden gate. It is magical. It hints at the occupants—who cared enough to make a special place. The gate beckons.

A garden is beautiful not just for the loveliness of what’s planted there, but because it represents the mind and spirit of the designer. Each garden is a meaningful response to nature. Each garden reflects care.

Zhuangzi’s gardener rejected the water pulley—the point was not to be more “efficient,” the point was to work in the garden honestly, with a unit of human effort matching a unit of nature.

Entering into a garden, then, is to witness human care in conjunction with nature. It is a circular system: as much as the garden may “benefit” by the attention lavished upon it, the gardener is nourished too, and the garden’s occupants find renewal and revitalization in all that is put into that garden.

Open the gate, open your heart, and let your flag stand as the highest standard.

Zhuangzi’s Gardener

Zhuangzi tells the story of the scholar Zigong, who met an old man tending a section of a vegetable garden.

He had dug his channels, gone to the well, and was bringing water in a jar to pour into the ditches. He toiled and expended a great deal of strength, but accomplished very little.

Zigong said: “You could use equipment and thereby soak a hundred fields in a day. With little effort you could achieve a great result. Would you, master, like to try it?”

The gardener looked up and asked, “How does it work?”

“It is a wooden device, heavy behind, light in front. It draws the water as quickly as water boiling over. It is called a gao [shadoof or water pulley].”

The gardener stood up angrily, then laughed. “I have heard from my teacher that where there are machines, there are sure to be machinations. Where there are machinations, there are sure to be scheming hearts. When pure simplicity is impaired, the living spirit is unsettled and cannot be with Tao. It is not that I do not know what you’re referring to; I would be ashamed to use it.”

Zigong looked down abashed, hung his head, and said no more.

Let your flag stand as the highest standard.

When it waves, it shows the invisible.

How beautiful flags and banners are. They add so much to a house or garden. They display colors that are a joyous statement to the world.

All flags and pennants are symbols. Like words, they communicate. Sunzi’s Art of War states: “When fighting at night, make much use of signal-fires and drums, and when fighting by day, use flags and banners.”

Flags show us the unseen. The wind is normally invisible—if we can see the wind, in the form of tornados or waterspouts, we are in real trouble. A benign wind is a different matter. Like the sage, it is invisible. Flags let us know that the wind is there.

A flag reveals the unseen wind, so it also symbolizes the unseen principle. A master holds up a standard to us. We are meant to behold it and to take heart from it as if it were a flag waving in the wind, and to strive for what that flag means.

A flag is just colored cloth. Yet people live and die for those colors, not because of any literal value, but for what they represent. How amazing that people will unite around such a symbol in every culture even though the material from which the symbol is made has no intrinsic worth. That’s something to remember when we wonder if gods and religion have value.

We fly flags, banners, and pennants over our gardens because the gardens themselves are important to us. Like the flag, the garden is a standard of how we want to live and how we want to live with nature. We cultivate it, nurture it, care for it. Living in a garden is a standard to which we aspire—and the flag is just the start of understanding that.

When it waves, it shows the invisible in the garden: temple and retreat.

• Fasting day

The Sixth Patriarch: Why Does the Temple Flag Wave?

Case 29 of the Wumenguan tells of a debate between two monks:

One said: “The flag moves.”

The other said: “The wind moves.”

They argued repeatedly but could not reach a conclusion.

The Sixth Patriarch said: “It is not the wind that moves. It is not the flag that moves. It is the mind that moves.”

Sunzi and the Art of War

Sunzi (c. 544–496 BCE) was a general, strategist, and philosopher and the author of the Art of War (Sunzi Bingfa), a book of military strategy studied today around the globe and utilized in business.

Sunzi described five important points for strategy:

First is Tao.

Second is Heaven [nature, weather].

Third is Earth [situation, terrain].

Fourth is the General [leader].

Fifth is Art [strategy].

A good general was the one who “had Tao.”

If you know the enemy and you know yourself, one hundred battles will not be dangerous. If you don’t know the enemy but know yourself, even winning once will be burdensome. If you neither know the enemy nor know yourself, then every battle will end in your defeat.

Sunzi discussed the use of flags during battle in this way:

Words can’t be heard, so we use gongs and drums. We can’t depend solely on ordinary sight, so we use banners and flags. We use gongs, drums, banners, and flags so we can see and hear as one. The brave will not advance alone, the cowardly will not retreat alone. This is the art of mobilizing a large army.

The garden: temple and retreat.

In solitude, open your heart.

We retreat, like the sages, to remote caves on windswept and mist-shrouded mountains to contemplate the Way without other human presence. We visit priests, nuns, and monks in gilded temples to learn more about the Way, marveling at the architecture dedicated solely to the otherworldly. We learn of the wandering seekers who traveled the length and breadth of China, who traversed the Silk Road, who climbed the Himalayas, and who visited the civilizations of India, Persia, and Europe in their quest for understanding.

Yet not all of us can have long access to the experiences of immortals, holy people, and spiritual seekers. Not all of us can live on mountaintops or in temples or on the road to enlightenment. But we can all have gardens—and those of us who do not possess our own can have an even grander experience in public gardens.

Just as a bonsai (penzai—”to grow in a basin”) represents a great tree, we are not slaves to scale. The universe can exist in a speck of dust. A speck of dust can be infinite in size. The important thing is that our gardens are retreats from the turmoil of the outside world, allowing us to renew our ties with nature and therefore with ourselves. In that place of retreat, not only can we enjoy the beauty of what surrounds us, we can also enter into a meditative state. We can pick a flower or rock to gaze upon and all of Tao opens to us. We can listen to the trickle of a stream and all of Tao opens to us. We can inhale the breath of the trees and all of Tao opens to us.

Today is the day commemorating Guanyin’s becoming a bodhisattva: that means that spiritual transformation is possible for any of us. Guanyin’s legend is also a simple way of understanding what the essence of spiritual transformation might be: to contemplate, to listen, to understand the suffering of others. When Guanyin returns to earth after nearly turning hell into paradise, she lives in solitude on the island of Putuoshan to listen to the cries of the world.

In the end, we may retreat to the solitude of our gardens, but the goal is neither escape nor selfish withdrawal. The goal is to become more attuned to nature and to ourselves—and there, in that solitude, to become more attuned to the entire world.

In solitude, open your heart: accept how a thicket grows, and “pattern” comes later.

• Commemoration of the day Guanyin became a bodhisattva

When Confucius Went to See Lao Dan

This parable is from the Zhuangzi. Lao Dan is another name for Laozi. The story should be taken as an allegory rather than a description of an actual historical meeting.

Confucius went to see Lao Dan, arriving just as Lao Dan had finished washing his head and was letting his uncombed hair dry. Lao Dan was motionless, as if he were not a person.

Confucius waited quietly. When he was introduced after a short time, he said: “Was I confused? Is it really you? Just now, sir, your body was like dead timber. You seemed as if you had abandoned all things, as if you had left the human world and were standing in solitude.”

Lao Dan replied, “My heart had roamed to the beginning of all things.”

© Kathy Bick

170 Rubble, Stumps, and Thicket

A thicket grows, and “pattern” comes later.

Let us grow simply as nature allows.

Most people can find the beauty of a garden self-evident and breathtaking. How many look at the heap of plucked weeds, the rubble and stumps of the areas being cleared? How many look at the fallow fields, or the storm-wrecked fallen tree? How many look at the dense hedges and thickets that have been left to grow as they will? These areas are no less beautiful than the tenderly cultivated flower bed simply because they are not accomplished in the glory of perfection. Rather, they are perfect in the glory of possibility. In them is a single basic lesson: that earth is constantly fecund; that earth takes back anything, no matter what it is; that earth is the receiving ground for every aspect of nature and human life.

There is a beloved Taoist word, “pu.” We take it today to mean “plain,” “simple,” “honest,” or “rough.” The rubble on the ground is like that. Stumps are like that. A thicket is like that. Nature has its own patterns. Perhaps they are “determined” in advance by the inherent nature of the plant: a bamboo will not grow to look like a pine. And yet, even though we know the seedling of a plant will grow into what it must be, we cannot know in advance how that plant will look, exactly how tall it will be, precisely what branching will occur.

If we look at any leaf, we will know reliably what kind of tree it comes from. And yet, if we look more closely at the leaf, we cannot find that its pattern of veins is like that of any other leaf.

In the same way, each of us may be a human being, each of us may have an inherent genetic and mental character with which we were born, and yet each of us will be unique. We don’t need to “make” ourselves into something! We don’t need to “be” anyone else! We can only be who we are, and accepting ourselves just as we accept what’s in our garden is plain and simple. And if we accept what is plain and simple, then we in turn become who we are, plain and simple.

Let us grow simply as nature allows; we are the whole, just as one rock is a whole mountain range.

Pu and the Daodejing

The word pu appears in the Daodejing. The left side of the ideograph shows that the word is in the category of wood, and the right side means “thicket.” It has been frequently translated as “a block of wood.” Wood in its natural state represents a human being as a plain and simple person.

In Chapter 15, Laozi describes the sage as “sincere, like plain wood.”

One rock is a whole mountain range.

One person is the universe.

The trinity of rock, tree, and moss is one of the most charming features of a garden. The varying combinations of just those three elements form an endless variety of poems—wood, green, and stone “rhyming” with more possibilities than words can offer.

Shadows alone are a fascinating theme. Shadows on tree trunks show roundness, interrupted by the texture of bark—the smoothness of the maple, the roughness of the pine. Shadows on moss are a fine stipple, any highlights on the moss muted to the green of new growth. Their fine stems and branches reach for life, as we all do, but in their own way—with profusion yet modesty. Shadows on rock are jagged, forceful, broken in facets too unpredictable to allow boredom. Gardeners in the past have spoken of finding inspiration in these three elements and seeing wordless instruction in how to be human. Can we weather life like the rock? Can we cling and accept a humble position like the moss? Can we be rooted, yield to storms, and yet prosper like the tree?

One person is the universe: let the sun burn leaf shadows everywhere.

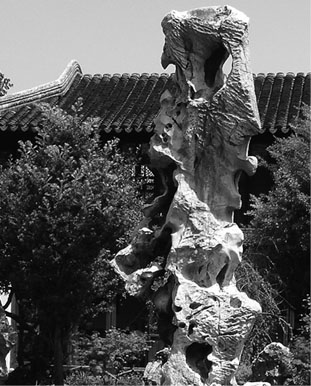

Taihu Rocks

Appreciation and collection of rocks has a long history. Rocks were placed in gardens at least as far back as the Han dynasty (206 BCE–220). Among the types of rocks are small ones that people keep personally, medium-sized rocks that scholars keep as indoor sculptures, and large rocks placed in gardens. The four principal aesthetic qualities of rocks were set down in the Tang dynasty (618–907): thinness (shou), openness (tou), perforations (lou), and wrinkling (zhou).

Among the most famous and prized rocks are the ones from Taihu, a lake near Suzhou. The most valuable are those that were naturally formed—with wave-carved patterns and perforations worn through by the lake. Today, artisans partially sculpt and carve stones to hasten the erosion process before submerging them in the lake. The sculpted rock that is retrieved, sometimes decades later, commands high prices.

Let the sun burn leaf shadows everywhere.

A lantern at night reclaims all vision.

Light is an indispensable part of a garden even beyond the obvious need for the growing power of sunlight. White garden walls are a perfect screen on which to watch the movement of shadows from morning to night. The noon sun shines down in great shafts, punching bright patterns through leafy branches. Sparkles dance across the pond where the orange, black, and white carp come to the surface.

At night, we still want light in our gardens. Perhaps we have a bonfire or fire pit to keep warm on chilly nights. Or perhaps we want the mellow glow of a single candle set in a stone lantern deep in the shadows among the maple and camellias.

A lantern at night doesn’t simply light the way. It beckons. It reminds. It says “Welcome home” to the weary traveler. It says, “I remember,” even when the night is dark. It says, “I love the spirit,” for the spirit is like that: a solitary light burning in the dark.

In lighting lanterns, we remember fire. Every legend of the Fire God goes back to the earliest times because fire is that fundamental to our lives. We may seemingly have tamed it to fine proportions with our glowing monitors, our forced-air heaters, our stainless-steel stoves, and our firefighters. We need fire, and it is always wild, captured for the moment, never truly domesticated.

So even in a garden at night, we light a fire. We don’t take it for granted—that’s why it’s housed in bronze or stone—and we approach it humbly—that’s why we commit only to a wick. It is not the candle that is small. It is we who dare not approach fire in a way that overwhelms us. We cannot look directly at the sun. We cannot approach fire in its full might.

We are single spirits, alone in our gardens. We embed ourselves in the glory of nature. We light candles to remember the centrality of fire and light.

A lantern at night reclaims all vision; we follow the light to ride day and night.

• Day of the Fire God

God of Fire

The Fire God (Zhu Rong) has a number of origin stories. Here are two of them.

The first story centers around the deification of Lo Xuan, who was a minister to the last king of the Shang dynasty, Di Xin. In the legend, Lo was a Taoist priest whose face, hair, and beard were bright red; he had three eyes and wore an ornamented red robe. His horse snorted flames and shot fire from its hooves. While fighting for the dynasty, he changed into a giant with three heads and six arms, each with a magic weapon: a seal reflecting heaven and earth, a wheel of fire dragons, a gourd with ten thousand fire crows, two swords, and a column of smoke containing fire swords. (Zhao Gongming’s story, is from the same time.)

The second story of Zhu Rong’s origin as the Fire God dates from even earlier (2698–2598 BCE). He was a legendary emperor who taught people how to use fire for many things: to drive predatory animals away, to smelt, to forge, to weld. His tomb is on the southern slope of Hengshan.

We follow the light to ride day and night,

riding with the purity of a mare.

Horses have been a part of human development throughout the world. The horse was a means to work, to travel, and to fight. Domesticating wild horses meant learning to communicate with and ride an animal that was many times stronger than any person. Riders are devoted to their horses, and many horses are loyal to their riders.

The Horse King is an extension of that relationship. Worshipping him expresses reverence for that special bond between human and animal. It also acknowledges that we have harnessed another living creature in order to extend our wills.

A farmer had to work together with family and other farmers. A general had to work with soldiers. A rider had to work with horses. There was the need to be aware of other people and animals. Now, we don’t work so intimately with others: our machines only reflect our own visages, and we are the poorer for it.

The horse is mighty, vigorous, and spirited. Don’t we imagine our heroes on horses? That symbol is still potent today. But the image of the mare is also important: the mare represents fecundity, docility, and forbearance. If we could have the power and spirit of a stallion and the gentleness of a mare, we would be complete. Only by honoring how we’ve domesticated animals can we domesticate ourselves.

Riding with the purity of a mare, pure as when the lotus grows from filth.

© mariait

• Fasting day

• Birthday of the Horse King

The Horse King

The Horse King (Ma Wang) is mostly worshipped in the north because the horse was in greater use there and because Mongolian horses were particularly prized. Horses were significant in transportation, travel, commerce, and warfare even into the early twentieth century. The horse remains a symbol of speed, perseverance, and quick-witted youth.

In some images, the Horse King is shown as an ogre with three eyes and four hands holding various weapons. Often shown with the Bull King (Niuhuang), the Horse King was a god for ranchers and all those who raised horses and livestock.

The Mare

In the I Ching, one of the central symbols is Earth, and earth is specifically tied to the image of a mare: “Gain by the purity of a mare.”

The lotus grows from filth,

yet the muck rolls right off.

The lotus is a much-beloved flower. It is the symbol of purity because it grows in bogs and marshes and yet rises pristine and pure. Rain and mud roll off of flowers and leaves. The Confucian scholar Zhou Dunyi (1017–1073) wrote: “I love the lotus because while growing from mud, it is unstained.” No wonder that the lotus has become the symbol of spirituality—to the point where meditators imagine energy centers in the body as opening lotuses.

You can see the entire cycle of life in one lotus pond. The shoots are like the beginnings of life. The flowering is the glory of life. The lotus pod with its many seeds is the reproducing of life. And when the leaves wither and decay into brown lace, we see the seeming decline of life—but with a hidden power in the seeds that means that life will come again.

In the water and mud, the lotus roots are rhizomes running in long sections. If one cuts them open (every part of the lotus is used as a food, tea, or soup), one sees that tuberous roots have hollow channels. The roots have become the symbol of continuity because of their length, and their hollowness represents the open mind to which wise people aspire.

The entire world’s wisdom can be found just by contemplating the lotus.

Yet the muck rolls right off, so live unstained by the dirty world.

• Birthday of the lotus

• Birthday of Guan Yu

• Birthday of the Thunder God

• Fasting day

The Thunder God

The Thunder God (Lei Gong) has the face of a monkey, a long and pointed jaw, feet like eagle talons, and a muscular body. He holds a wedge in his left hand and a hammer in his right, ready to beat any of the five drums around his waist or the drum under his foot. He is a god of justice and often appears to punish—and even execute—the wicked.

“After the Lotus Flowers Have Opened”

This poem was written by Ouyang Xiu.

The lotus flowers on West Lake have opened well.

It’s time to bring the wine!

There’s no need to wave signal flags

when all around us are red curtains and green canopies!

We punt our painted boat where the flowers are thick.

Aroma floats from our golden cups.

Misty rain is light and fine,

with a bit of pipe song I go home drunk!

Live unstained by the dirty world.

Live without care and you live long.

No matter who we are, we should embrace that.

But some of us struggle to embrace ourselves. We find it painful to embrace our flaws and appearance, our age and failures. We find it painful to check back on our goals and see how we’ve fallen short. We find it painful to look at what both Eastern and Western societies say success means and realize that we are never going to be celebrities or world leaders or champions. Today, on the birthday of Lan Caihe, it’s important to look at who this immortal was: he was positively nonconformist, unique, and contrary to everything that was socially acceptable. Note that he was not nonconformist because he hated society. No, he was who he was first—and the labels came afterward.

In a time when every person aspired to success in the examinations, civil service, wealth, power, position—in short, to being as close to the throne as possible—Lan Caihe was contrary in every way. He was indifferent to money; he didn’t care where he lived or how he dressed. Yet he enjoyed singing and dancing in the street—and he possessed the secret to immortality. That trumped power and wealth.

We should be who we are, even if that doesn’t fit society’s categories—including, in Lan’s case, those of sexual identity. Was Lan of ambiguous gender? Was he gay? Was he indifferent to sexuality? Perhaps it’s worth considering that he did not define himself by gender.

Nothing about Lan fit what was conventional, but he became a god. The real secret shown here is not necessarily the secret to immortality, but the secret that being true to oneself is in itself a path. This leads to one’s own personal Way. We are at the beginning of Lan Caihe’s song. We need to sing it as we dance through the streets. Only then can we find the sweet themes that belong to us alone.

Live without care and you live long— if things aren’t right, what are you going to do?

• Birthday of Lan Caihe

Lan Caihe

Lan Caihe, one of the Eight Immortals, is of ambiguous gender and is varyingly portrayed as a youth, an old man, or a girl. One early play depicted Lan as a man, while another showed her as a woman. Chinese names and pronouns are not necessarily gender-specific, and the situation has remained undefined.

Lan carries a flower basket containing various plants associated with longevity: the lingzhi mushroom, sprigs of bamboo and pine, plum flowers, chrysanthemum, and a red-berried plant called “ten thousand years green.” He often goes about with one bare foot, carrying castanets and a string of cash. In summer, Lan wears a padded wool gown. In winter, Lan sleeps in the snow, exhaling breath like steam.

When drunk, Lan likes to sing and dance in the street, not caring whether his string of cash breaks, is given away to the poor—or is used to buy more wine.

If things aren’t right, what are you going to do?

Will you dive with your sword to do battle?

Some Taoists say that we should accept everything as it is. Why do they then busy themselves with so many things? Practicing exercises, chanting scriptures, digging in their gardens, traveling the world, healing the sick. For people who are supposed to simply rely on Tao, they really are quite contrary.

A Taoist does not depend solely on doctrine. All is meant to be revised and changed. As soon as you say what a Taoist is, a thousand exceptions can be found. As soon as you say what a Taoist isn’t, you’ll meet a person who isn’t like any of the classical descriptions and yet demonstrates the insight and character of a Taoist. You’ll never pin a Taoist down. You’ll never define one. And if you are one, you delight in being yourself. Every rule is meant to be broken, and every broken rule only proves the rule in the first place.

Sometimes, Tao is out of balance. Sometimes, things are wrong and people are suffering. Is it Tao to act? Or is it Tao to retreat? Tao is not to fall into the trap of choosing between extremes, but rather to act spontaneously as is right at the moment.

If an evil dragon is hurting the people year after year, and the Taoist has a great sword, then let that Taoist act and save the people. If a person has the ability to save others and does not—then that person is the true evil dragon.

The great flood of life is constantly upon us. If you can, like Li Bing, relieve suffering by diverting the waters, and sustain others by bringing water to them, that’s a superior way of life. People help in the ways that are most suitable to them. For some, the way might be fighting dragons with swords. For others, it is designing practical flood management. Everyone is the sage-king according to his or her particular circumstances.

Will you dive with your sword to do battle? Stop: wine will bring a moment of clarity.

• Birthday of Erlang

Erlang

The name Erlang means “second son.”

Erlang was the son of Li Bing (c. third century BCE) and a disciple of Taoist Li Jue. When he was appointed prefect by Emperor Yangdi (605–617), Erlang learned that a river dragon flooded the land every year. When another flood occurred during the fifth moon, Erlang led ships and soldiers onto the waters and dove into the depths with a sword. After a fierce underwater battle, he returned with the dragon’s head.

Erlang was deified a mighty celestial warrior, with his spiritual third eye opened. Wherever he goes, he is accompanied by a hound named Eagle Dog, and he carries a magical mirror that reveals hidden demons.

People still claim to see him in stormy weather, riding the river waves on a white horse and accompanied by his dog. Erlang is also the god of stage artists and acrobats.

The Dujiangyan Irrigation System

The Dujiangyan Irrigation System was built on the Min River in the state of Qin in 256 BCE. It is still in use today and is considered an outstanding example of good water management, controlling flooding and providing for the irrigation of over 2,000 square miles (5,180 square kilometers).