Moving toward a more comprehensive consideration of the antecedents of trust

Michael D. Baer and Jason A. Colquitt

Introduction

Why do people trust? Considering the substantial literature on trust, one might initially expect that a single chapter would be unable to adequately review the answers to this question. On closer inspection, however, the answers provided by the literature comprise a very narrow set of answers. Indeed, narrative and meta-analytic reviews of trust have observed that empirical research has been almost entirely limited to exploring just two broad answers to this question – because people have trusting dispositions and because others are trustworthy (Colquitt, Scott, & LePine, 2007; Dirks & Ferrin, 2002; Möllering, 2006). In other words, the literature has reached a consensus that people trust as a result of their dispositional tendencies to rely on the words and deeds of others, and because others demonstrate, in a variety of ways, that they can be relied upon (Mayer, Davis, & Schoorman, 1995).

This narrow focus in the literature can be at least partially attributed to early conceptual models of trust, most notably the ‘integrative model of trust’ presented by Mayer, Davis, and Schoorman (1995). Mayer and colleagues defined trust as the willingness to be vulnerable to another party based on the expectation that the party will perform a desired action, regardless of the trustor’s ability to monitor that party. Previous scholars had defined trust as an aspect of the trustor’s personality (Rotter, 1967; Webb & Worchel, 1986; Wrightsman, 1964) and as synonymous with the positive expectations arising from the characteristics of a trustee (e.g. Butler & Cantrell, 1984; Sitkin & Roth, 1993). Mayer et al. (1995), however, argued that these constructs were more appropriately modeled as antecedents of trust. In their model, the disposition to trust was labelled trust propensity – a stable individual difference that reflects a generalized tendency to rely on the words and deeds of others (see also Rotter, 1967; Stack, 1978; Wrightsman, 1964). Characteristics of the trustee were labelled trustworthiness – a multidimensional construct reflecting perceptions of the trustee’s task-specific skills (ability), concern for the trustor (benevolence) and values (integrity). Although a broad range of trustee characteristics have been examined within the literature, Mayer and colleagues proposed that ability, benevolence and integrity are a parsimonious yet inclusive set.

Notwithstanding the strides that have been made in understanding these antecedents of trust, several key areas remain unexplored. First, the concept of trust propensity has dominated treatments of disposition-based trust. Yet, is trust propensity the only individual difference that affects trust, or are there other traits that contribute to a disposition to trust? Second, although trustworthiness has been conceptually and empirically divided into the sub-facets of ability, benevolence and integrity (Mayer & Davis, 1999; Mayer et al., 1995), little has been done to determine the boundary conditions for the importance of each facet (Colquitt et al., 2007). For example, does ability matter more than integrity in some jobs? Is this pattern reversed in other jobs? Similarly, despite theoretical suggestions that the impact of trustworthiness on trust may depend on the personality of the trustor (Mayer et al., 1995), these dynamics have not yet been explored.

Although two decades of empirical and conceptual research have provided considerable support for Mayer et al.’s set of antecedents, some scholars have suggested that a comprehensive model of trust should necessarily include an affective component (e.g. Jones & George, 1998; Lewicki & Bunker, 1996; Lewis & Weigert, 1985; McAllister, 1995; Williams, 2001). Trustworthiness and, to a lesser extent, the disposition to trust, form a calculative, cognitive foundation of trust (Lewicki & Bunker, 1996; Lewis & Weigert, 1985). In a departure from this cognitive approach, many scholars have proposed that trust also stems from the emotional bonds between trustor and trustee (Johnson-George & Swap, 1982; Lewicki & Bunker, 1996; Lewis & Weigert, 1985; McAllister, 1995; Rempel, Holmes, & Zanna, 1985). This base of trust has received a number of different labels, including emotional trust (Johnson-George & Swap, 1982; Lewis & Weigert, 1985), affect-based trust (McAllister, 1995), faith (Rempel et al., 1985) and relational trust (Rousseau et al., 1998). There are some differences between these conceptualizations, but they converge on the notion that care and concern are an important base of trust.

Even though these conceptualizations seem to suggest affect is a widely-accepted ‘third’ base of trust, many scholars have noted that Mayer et al.’s concept of benevolence encompasses the care and concern that characterizes conceptual and empirical treatments of affective bases of trust (Colquitt, LePine, Zapata, & Wild, 2011; Colquitt et al., 2007; Dietz & Den Hartog, 2006; McEvily & Tortoriello, 2011). Indeed, Mayer et al. defined benevolence as ‘the extent to which a trustee is believed to want to do good to the trustor … [it] suggests that the trustee has some specific attachment to the trustor’ (1995: 718). Adding to this conceptual and empirical confusion, whereas some scholars have conceptualized affect as a characteristic of the dyadic relationship between trustor and trustee (e.g. McAllister, 1995), others have conceptualized affect in terms of the emotions and sentiments of the trustor (e.g. Dunn & Schweitzer, 2005; Jones & George, 1998). Still other scholars have adopted an approach that includes both conceptualizations (Williams, 2001). In sum, the literature has yet to reach a conceptual or empirical consensus on the role of affect as an antecedent of trust.

Although a model of trust that includes both emotional and rational bases may appear comprehensive, there are phenomena that this model cannot adequately explain. For example, consider the experience of employees who join a new organization. During the initial stage of employment, employees will have had little time to gather ‘data’ on the trustworthiness of their coworkers or supervisors. Likewise, they will not have had the opportunity to form emotional bonds with their new colleagues. Yet, scholars have observed that individuals in new situations still trust – at levels not fully explained by dispositional trust (for a review, see Balliet & Van Lange, 2013). If this trust is not based on disposition, rational reasons, or emotions, what explains why these employees trust? In a departure from the conscious, cognitive approach that has dominated empirical investigations of trust, scholars have begun to suggest that trust is also influenced by less-conscious, heuristic predictors. For example, McKnight and colleagues (1998) proposed that trust in the organization may be influenced by the extent to which the organizational setting seems normal, customary and in the proper order. Although this stream of research is in its nascent stage, we argue that heuristics provide insight into trust dynamics that are unexplained by current models.

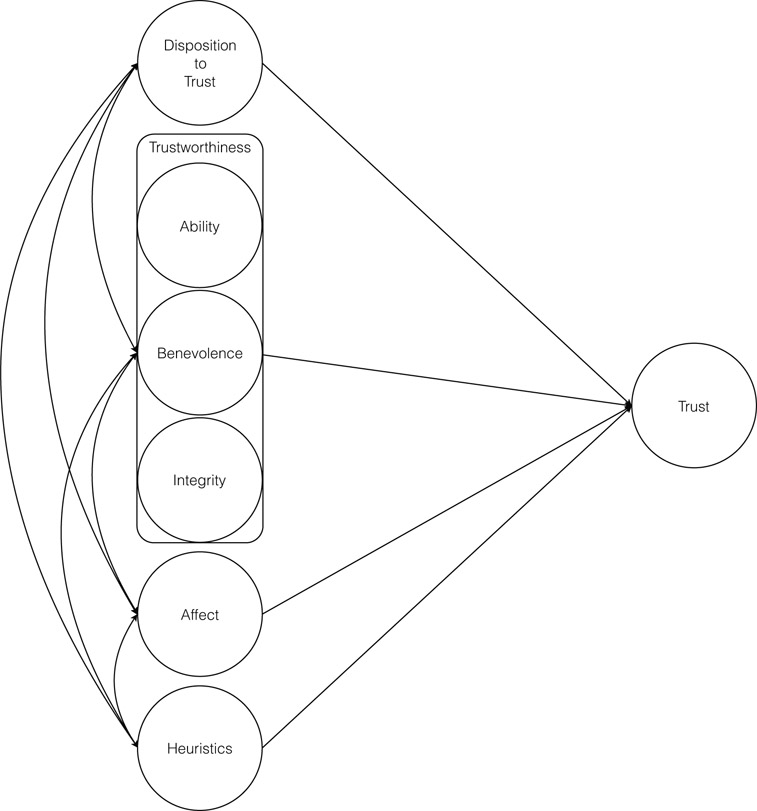

In this chapter, we first review the research addressing the disposition to trust and trustworthiness. Next, we review the conceptual and empirical research on the role of affect as a base of trust. Finally, we propose that heuristics are an important (yet relatively unexplored) antecedent of trust. In each section we highlight areas with unanswered questions and make recommendations for future research. Thus, this chapter reviews the current answers to ‘Why do people trust?’ while also suggesting new answers. Our expanded approach to the antecedents of trust is represented in Figure 9.1. This figure is intended as a broad overview of several categories of antecedents rather than as a graphical representation of specific hypotheses regarding these antecedents. By more closely examining the role of the disposition to trust, trustworthiness and affect, and expanding the focus to additional antecedents of trust, this chapter should aid scholars and organizations in taking a more holistic approach to understanding and increasing trust.

The disposition to trust

Consider the following scenario. Two friends – Chris and Pat – are separately approached in a mall parking lot by a stranger who claims to need a couple of dollars for bus fare so he can pick up his kids from school. Chris gives the man the benefit of the doubt and hands over the two dollars. Pat assumes it is a scam and politely tells the guy to take a hike. This scenario illustrates the idea of a trusting (or distrusting, in Pat’s case) disposition. Some of the earliest research on the disposition to trust was conducted by Rotter (1967, 1971, 1980), who argued that trust was based on an individual’s generalized expectancies of others. He proposed that the characteristics of a trusting personality could be distilled to a single trait, defining interpersonal trust as an individual’s generalized expectancy that others can be relied on. Rotter’s (1967, 1971, 1980) conceptualization of trust as a relatively stable personality characteristic is illustrated by a sample item from his Interpersonal Trust Scale (Rotter, 1967): ‘Most people can be counted on to do what they say they will do.’ This generalized expectancy that others can be relied upon has been referred to by other scholars as dispositional trust (Kramer, 1999), generalized trust (Stack, 1978) and trust propensity (Mayer et al., 1995; McKnight, Cummings, & Chervany, 1998).

Research suggests that the disposition to trust may begin to take shape in children as early as 6 to 18 months of age (Deutsch & Krauss, 1965; Rotter, 1971), with development likely occurring through at least two mechanisms: reinforcement and modelling (Webb & Worchel, 1986). With respect to reinforcement, the extent to which needs are met during this developmental period may provide a baseline for the extent to which others in life can be expected to meet one’s needs (Erikson, 1963; Webb & Worchel, 1986). As needs are met in the infant–parent relationship, the infant may extend positive expectancies to others, both within and outside the family (Sakai, 2010). Although these expectancies are likely not the only determinant of a general willingness to trust others, they may be a ‘necessary precursor’ (Webb & Worchel, 1986: 217).

Scholars have proposed that the general willingness to trust is also influenced by the extent to which a trusting orientation is modelled by the parents (Katz & Rotter, 1969; Stolle & Nishikawa, 2011). Although trust propensity is heavily influenced by primary caregivers, it may also continue to be refined through experiences with peers, teachers and other close sources (Flanagan & Stout, 2010; Katz & Rotter, 1969; Rotter, 1967; Webb & Worchel, 1986; for a review, see Sakai, 2010). In support of this proposal, studies of twins’ trust propensity suggests that non-shared environmental influences in childhood have an even greater impact on trust propensity than shared environmental influences (Hiraishi, Yamagata, Shikishima, & Ando, 2008; Sturgis et al., 2010).

In management research, many of the hypothesized effects of the disposition to trust are grounded in social learning theory (Rotter, 1954; Rotter, Chance, & Phares, 1972). According to social learning theory, expectancies in each situation are determined not only by experiences in that situation but also by experiences in similar situations. The theory also specifies that the influence of generalized expectancies is relative to the amount of experience the person has in that particular situation (Rotter, 1980). For example, a person’s expectations of a used-car dealer are likely influenced by experiences with that particular dealer as well as experiences with previous dealers. If previous dealers were dishonest, the person will likely expect the current dealer to also be dishonest. Through interactions with the current dealer, however, the person gains situation-specific ‘data’, thereby decreasing the impact of generalized expectancies. Research supports these proposals, finding that the impact of trust propensity decreases over time as individuals gather information on trustworthiness (Gill, Boies, Finegan, & McNally, 2005; van der Werff & Buckley, in press).

It follows that the disposition to trust should be particularly relevant in novel situations. When actors are unfamiliar with one another, they have little to no situation-specific data on which to base trust. Accordingly, the generalized expectancy resulting from past experiences likely plays a pivotal role (Bigley & Pearce, 1998). McKnight and colleagues (1998) argued that dispositional trust is becoming increasingly important in the current work environment as increased turnover, corporate restructuring and temporary work teams are resulting in a higher frequency of new work relationships. Despite the proposed importance of dispositional trust, it has received far less empirical attention than trustworthiness (Colquitt et al., 2007; Kramer, 1999). Some of this lack of attention may be due to a general consensus that the relationship between dispositional trust and trust will decrease as familiarity with the trustee increases (Bigley & Pearce, 1998; Mayer et al., 1995; Rotter, 1967). Yet, Mayer et al. (1995) suggested that even in familiar relationships trust propensity is likely to exhibit an effect on trust. Colquitt et al. (2007) tested this proposal in a meta-analysis, finding that trust propensity continued to have a significant relationship with trust when controlling for trustworthiness.

Despite the clear consensus that the disposition to trust is an important antecedent of trust, questions remain. In contrast with Rotter’s view of a trusting disposition as a fixed, enduring trait, Hardin (1992) proposed that the inclination to trust (or distrust) is reinforced by the trustor’s own behaviour. People with low dispositional trust are less likely to engage in cooperative behaviour, making it unlikely that they will encounter information that alters their generalized perceptions of others. Reflecting on this notion, Bigley and Pearce (1998) questioned whether organizational interventions might be able to modify the disposition to trust. At first glance, the proposal to modify a trait seems counter to the nature of traits as fixed and enduring (McCrae & Costa, 1994). Recent research, however, has been moving toward perspectives that acknowledge the stability of personality while also allowing for change and variation across situations and one’s life span (Fleeson & Jolley, 2006; Judge, Simon, Hurst, & Kelley, 2014). Sitkin and colleagues (Sitkin & Pablo, 1992; Sitkin & Weingart, 1995) made similar arguments with respect to risk propensity – a concept that shares considerable overlap with trust propensity (Mayer et al., 1995). They suggested that risk propensity is a stable, cumulative tendency that can nonetheless change over time as a result of experience (Sitkin & Weingart, 1995).

To date, recommendations for increasing trust have focused almost entirely on what the trustee can do to be more trustworthy (e.g. Korsgaard, Brodt, & Whitener, 2002; Whitener, Brodt, Korsgaard, & Werner, 1998; for a review see Fulmer & Gelfand, 2012). This is not surprising, given that the disposition to trust has been treated as a stable trait. If, however, this disposition is malleable, organizations may also be able to foster trust through a trustor-focused approach. Empirical research has not yet addressed the variability of the disposition to trust, but some inferences can be drawn from recent work on the variability of the Big Five person ality traits (Judge et al., 2014). Judge and colleagues found that daily work experiences (i.e. citizenship behaviour, motivation and interpersonal conflict) predicted short-term variations in personality – resulting in what they referred to as ‘personality states’. Similarly, workplace experiences that prime positive emotions and cognitions may have positive effects on the disposition to trust. We suggest that explorations of the state-like nature of dispositional trust adopt the methodological approach followed by Judge et al. (2014), wherein they examined the deviations from baseline tendencies using an experience sampling design and hierarchical linear modeling. This approach allows researchers to account for both between- and within-person variance in traits. From this perspective, participants are asked how trusting or suspicious they are ‘today’, as opposed to in general.

Moving beyond trust propensity, are there other individual differences that can predict unique variance in trust? One potential answer to this question is found in a return to Sitkin and Pablo’s (1992) theorizing about the role of individual differences in risk behaviour (see also Sitkin & Weingart, 1995). Sitkin and colleagues proposed that individuals have a relatively stable risk propensity – the tendency to either take or avoid risks. This pattern of risk taking or risk aversion influences both how risks are evaluated and what risks are deemed acceptable. Although there are some clear similarities between trust propensity and risk propensity, the constructs differ in at least one important way. Unlike trust propensity, risk propensity does not involve an evaluation of the trustee.

The importance of this distinction is illustrated in the following scenario, in which a supervisor has two employees who have similar perceptions of the supervisor’s trustworthiness and levels of trust propensity, but differing levels of risk propensity. Both employees have presented the supervisor with ideas for improving unit performance, and the supervisor has suggested to both employees that she can present their ideas to upper management. It is an inherently risky proposition, as the supervisor may botch the presentation or fail to give the employees credit for their ideas. Both employees may, based on a low general tendency to trust others, be less inclined to entrust this critical task to their supervisor. Yet, while the employee with low risk propensity may determine that the risks do not outweigh the benefits in this particular situation, an employee with high risk propensity may decide to ‘roll the dice’ and trust the supervisor. In this example, risk propensity acts as a trait with independent effects on trust, above and beyond trust propensity.

In sum, there are substantial unanswered questions about the disposition to trust and its effects on trust. We highlighted a couple of these questions: First, is the disposition to trust fixed? Second, are there dispositional predictors of trust that lie outside of trust propensity? In addition to providing theoretical insights, the answers to these questions also have practical utility. In most conceptual and empirical approaches to trust, the disposition to trust is treated as a single exogenous variable – trust propensity. From an organizational perspective, this model suggests that apart from selecting employees with high trust propensity, efforts to build trust should be focused on increasing the trustworthiness of the trustees, such as supervisors and organizations (Korsgaard et al., 2002; Whitener et al., 1998; for a review see Fulmer & Gelfand, 2012). If, however, trust propensity can be shaped by interventions (Bigley & Pearce, 1998), organizations may be able to take both trustor- and trustee-focused approaches to fostering trust. Relatedly, if there are additional traits that contribute to a trusting disposition, organizations may benefit from selecting employees who possess these traits.

Trustworthiness

The disposition to trust has a limited ability to explain trust. Research, experience and common sense suggest that individuals – despite having a relatively stable disposition to trust – do not trust everyone equally in every situation. Similarly, an individual may trust a particular person in one area but not in another area (Barber, 1983; Hardin, 2002). Addressing these points, Lewis and Weigert (1985) argued trust is not simply based on a trusting personality, but also on the characteristics of the trustee. To illustrate, consider a new employee who is just getting acquainted with a coworker. In the first days of employment, the employee’s willingness to be vulnerable to the coworker on critical tasks is likely dependent on the employee’s generalized expectancies. After all, the employee has little ‘hard data’ on which to base the decision. Over time, however, the employee will start to gather data on the coworker’s characteristics, such as task-specific capabilities, goodwill and dependability, thereby decreasing the impact of generalized expectancies. In light of these dynamics, scholars have argued that the characteristics of the trustee – generally referred to as trustworthiness – are the primary determinant of trust (Gabarro, 1978; Lewis & Weigert, 1985; Mayer et al., 1995; Mishra, 1996; Pirson & Malhotra, 2011; Sitkin & Roth, 1993). Although the characteristics that comprise trustworthiness have received a number of different labels in the literature, current treatments generally conform to Mayer et al.’s (1995) proposal that trustworthiness is encapsulated by ability, benevolence and integrity.

Ability

Ability is the knowledge, skills and competencies required to perform effectively in some specific domain (Mayer et al., 1995). This definition highlights the notion that ability, and its relationship with trust, are task specific. For example, a skilled auto mechanic might be trusted to replace a transmission, but not to perform a medical procedure. Ability matters because of the interdependent nature of trust (Kee & Knox, 1970; Sitkin & Roth, 1993). Consider a supervisor who has been given a project from upper management. To efficiently complete the project, the supervisor contemplates delegating an important part of the project to a subordinate. Given that the supervisor is ultimately responsible for the outcome of the project, it is unlikely that the subordinate will be chosen at random. Rather, the supervisor is likely to select and trust a subordinate who has the ability to effectively accomplish the assigned task. In support of this proposal, Sitkin and Roth (1993) theorized ability is the primary indicator of trust within organizations.

Various scholars have used the term competence to refer to a construct that is conceptually similar to ability (e.g. Butler, 1991; Butler & Cantrell, 1984; Gabarro, 1978; Hardin, 2002; Kee & Knox, 1970). Barber (1983: 14) proposed trust is the expectation of ‘technically competent role performance’. Of the nine bases of trust inductively identified by Gabarro (1978), four of them – functional competence, interpersonal competence, general business sense and good judgment – are representative of ability. Sitkin and Roth (1993) referred to a similar concept – an employee’s ability to reliably complete assignments – as task reliability. Likewise, Cook and Wall (1980) focused on the capability and reliability aspects of ability as predictors of trust. Expertness – the degree to which an individual is a source of valid assertions – is another construct that is similar to ability (Hovland, Janis, & Kelley, 1953). Concepts coded as ability in Colquitt et al.’s (2007) meta-analysis of trust included competence, expertise, knowledge and talent.

Benevolence

Benevolence is the extent to which the trustor believes the trustee is concerned about the trustor’s well-being, apart from any self-interested motives (Mayer et al., 1995). Larzelere and Huston (1980) proposed a trustor is likely to question whether a potential partner is genuinely interested in the trustor’s welfare or is motivated by individualistic goals. To the extent that a trustee is seen as benevolent, the trustor is more likely to predict positive outcomes in the relationship. As a consequence, the trustor’s willingness to be vulnerable increases. For example, a supervisor would likely rely on attributions of benevolence when deciding whether or not to share sensitive information with an employee. An employee with low benevolence would be expected to disclose that information if it provided a personal benefit. Conversely, an employee who was concerned about the supervisor’s welfare would be less likely to breach confidence.

Other scholars have discussed concepts that overlap with benevolence. Gabarro (1978) suggested favourable perceptions of a trustee’s motives were a base of trust. Barber (1983) similarly argued that trust was based on an expectation that others would demonstrate a concern for interests above their own. Along these lines, Rempel et al. (1985) noted trust is dependent on a belief that the trustee will be responsive and caring. Other scholars have suggested trust is based on expectancies of altruism (Frost, Stimpson, & Maughan, 1978; Lindskold & Bennett, 1973). Several researchers (Butler, 1991; Butler & Cantrell, 1984; Jennings, 1971) have used the term loyalty – wanting to protect and make the trustor look good – to refer to benevolence. Concepts coded as benevolence in Colquitt et al.’s (2007) meta-analysis included openness, loyalty, concern and perceived support.

Integrity

Integrity is the trustor’s perception that the trustee adheres to a set of values that the trustor finds acceptable (Mayer et al., 1995). To a large extent, perceptions of integrity are based on consistency between the trustee’s words and deeds (Larzelere & Huston, 1980; Rempel et al., 1985; Schlenker, Helm, & Tedeschi, 1973; Simons, 2002). Speaking to this issue, Simons’ (2002) definition and treatment of behavioural integrity focused on word–deed alignment. In contrast, Mayer et al. (1995) argued that adhering to a set of values or having high word–deed consistency is not sufficient for perceptions of integrity. This proposal was based, in part, on theorizing from Sitkin and Roth (1993), who suggested a base of trust was the compatibility of values and beliefs between trustor and trustee. They proposed a lack of value congruence would decrease trust. To illustrate the necessity of integrating the idea of word–deed consistency and values congruence into a definition of integrity, consider an employee who values and single-mindedly pursues personal gain. Although the employee’s actions have high integrity – they are internally consistent, after all – a supervisor is unlikely to perceive the employee as having integrity unless the supervisor shares similar values (Mayer et al., 1995). At first glance, the integration of value congruence and word–deed consistency into a definition of integrity seems a bit inconsistent with the definition proposed by Simons (2002). Further scrutiny reveals, however, that his model of behavioural integrity includes a concept that overlaps with value congruence. He proposed that the more a trustor cares about the issue related to word–deed consistency – i.e. an alignment or misalignment on values held by the trustor – the more the event will affect integrity perceptions.

Other scholars have also addressed the nature of integrity and its importance to trust. Larzelere and Huston (1980) proposed attributions of honesty allow a trustor to take the trustee’s word at face value. Accordingly, the trustor has more positive expectations of the outcome and a greater willingness to be vulnerable in the relationship. The critical nature of integrity perceptions were shown empirically by Butler and Cantrell (1984), who found that integrity was one of the most important bases of trust. In an extension of this research, Butler (1991) examined several antecedents of trust that fit beneath the umbrella of integrity: integrity, promise fulfillment, consistency and fairness. Cook and Wall (1980) proposed trustworthy intentions were a key predictor of trust. Although this construct overlaps with benevolence, some of their scale items are reflective of integrity. Concepts coded as integrity in Colquitt et al.’s (2007) meta-analysis included procedural justice, promise keeping and credibility.

Summarizing the state of the literature, Möllering (2006: 13) proposed that a consensus has been reached: trust is ‘primarily and essentially’ a function of perceived trustworthiness. Supporting this claim, a meta-analysis revealed that all three facets of trustworthiness were strongly correlated with trust, while trust propensity was modestly correlated with trust (Colquitt et al., 2007). Importantly, all three facets exhibited unique relationships with trust in meta-analytic structural equation modeling. Given the strong support for Mayer et al.’s conceptualization of trustworthiness, where should research on this critical antecedent look next? Before providing new directions, we first provide a word of caution. It is tempting to infuse novelty into a study on trust by adding a ‘new’ trustee characteristic that predicts trust. For example, consider a study that shows that a certification (e.g. an MBA or PhD) is associated with trust. On the one hand, that sort of certification could be argued to trigger affect- or heuristic-based forms of trust, of the type reviewed in the following sections. On the other hand, that certification could simply be a proxy for ability. In that sense, the predictor would not be new, merely the operationalization of the predictor would be new. We would therefore caution scholars to control for ability, benevolence and integrity when introducing new predictors of trust so that incremental validity can be examined.

Returning to ability, benevolence and integrity themselves, one question concerns how often they hold a unique relevance to trust. In their theorizing, Mayer et al. (1995: 729) noted that ‘the question “Do you trust them?” must be qualified: “trust them to do what?” ’ To illustrate the importance of this question, consider an employee who may need to rely on a supervisor to handle a critical aspect of a project. In this case the primary consideration may be whether the supervisor has the requisite task-specific skills to effectively contribute. Now contemplate an employee who may be considering whether or not to disclose the commission of a costly error. In this case, the primary consideration may be whether the supervisor is concerned about the employee’s well-being. Both situations involve an element of risk and action depends on the employee’s willingness to be vulnerable, but the most important facet of trustworthiness is likely different in the two cases. Research has not provided much insight into these dynamics. Even though trustworthiness has been examined in a substantial amount of trust research, almost no work has examined moderators of the trustworthiness – trust relationship. In an exception to this trend, Colquitt and colleagues’ (2011) research with a group of firefighters showed that in high-reliability task contexts trust was based on integrity, whereas in typical task contexts trust was also based on benevolence. Accordingly, we suggest that future research strive to unpack the situational dynamics of trustworthiness. Researchers who pursue this path might find it fruitful to examine Sitkin and colleagues’ (Sitkin & Roth, 1993; Sitkin & Weingart, 1995) work on risk propensity, as they address the notion that the role of trustworthiness as an antecedent of trust may be situationally dependent.

Following the question of which facets are important in which situations, we add the question ‘For whom are those facets important?’. Mayer et al.’s (1995) model of trust suggests that trust propensity moderates the effects of trustworthiness on trust. We are unaware of this suggestion receiving attention in management research, but some information systems research on trust in Internet shopping found that trust propensity magnified the effects of integrity yet did not impact the effects of ability (Lee & Turban, 2001). The lack of research on this issue is some what surprising. The assumption in the literature is that trust propensity matters at the initial stages of a relationship, but that its importance wanes over time. If, however, trust propensity continues to impact trust through interactive effects with trustworthiness, researchers may have underestimated its importance. There are likely other personality traits that similarly moderate the relationships between the trustworthiness facets and trust. Consider, for example, the need for affiliation – a personality attribute reflecting individuals’ desire for emotional support and their tendency to react positively to that support (Hill, 1987, 1991). Hill (1991) found that need for affiliation amplified the effects of partner warmth on the desire to interact with that partner. That same dynamic could occur for the relationship between benevolence and trust. Research investigating the moderating influences of these, and other, personality variables on the relationships between the facets of trustworthiness and trust would certainly provide insight into for whom these facets matter.

Affect

In the same year that Mayer et al. (1995) gave scholars a new way of thinking about the cognitive drivers of trust, another paper increased the salience of affect. McAllister (1995: 26) described affect-based trust as growing out of the ‘emotional bonds’ and ‘emotional ties’ between people. Affect-based trust was contrasted with cognition-based trust, or trust rooted in ability and integrity sorts of concepts. In a sample of managers and professionals across industries, McAllister (1995) showed that affect-based trust grew out of instances of citizenship – with helpful behaviours presumably deepening emotional bonds. His results also showed that affect-based trust grew out of repeated interactions – with more time presumably allowing connections to deepen. Importantly, affect-based trust was strongly correlated with cognition-based trust, but not so strongly as to suggest the two were redundant. Did other trust scholars take note of McAllister’s (1995) concepts? Citation counts would certainly suggest they did, with over 5,000 citations in Google Scholar – a level eclipsed only by Mayer et al.’s (1995) own 10,000 for trust articles in that time period.

McAllister’s (1995) theorizing was rooted in earlier treatments of the affective-cognitive duality of trust (Lewis & Wiegert, 1985; Johnson-George & Swap, 1982; Rempel et al., 1985). For example, Johnson-George and Swap (1982) described how trust operates in close personal relation ships. They argued that a sense of emotional safety was important, even aside from a sense of reliability. A similar duality was shown in Rempel et al.’s (1985) examination, with trust in close relationships depending not just on predictability or consistency, but also on emotional comfort. What McAllister (1995: 37) did, in part, was apply such ideas to relationships between employees. In that context, affect-based trust was characterized by strong agreement with beliefs like ‘we have a sharing relationship’, ‘we would both feel a sense of loss if one of us was transferred’ and ‘we have both made considerable emotional investments in our working relationship’.

The content of McAllister’s (1995) affect-based trust scale is similar in many respects to conceptualizations of leader-member exchange – especially those that include affect. For example, Liden and Masyln (1998) argued that the depth and quality of a leader-subordinate dyad could be described by the degree of mutual contribution, mutual loyalty, mutual respect and mutual affect. From this affect-based perspective, deeper, more high quality relationships are marked by both members liking one another and considering themselves friends as much as colleagues. Given that similarity, it is not surprising that affect-based trust itself serves as a valid indicator of the depth and quality of dyadic relationships (Colquitt, Baer, Long, & Halvorsen-Ganepola, 2014).

As noted above, McAllister’s (1995) affect-based trust conceptualization also winds up being quite similar to Mayer et al.’s (1995) benevolence facet of trustworthiness. In their measure of benevolence, Mayer and Davis (1999: 136) asked trustors whether trustees were ‘concerned about my welfare’, would ‘go out of their way to help me’ and look out for ‘what is important to me’. Those sorts of behaviours seem like the building blocks of a ‘sharing relationship’, to use one of McAllister’s (1995) phrases. Put differently, those sorts of behaviours seem like the ‘considerable emotional investments’ that McAllister (1995) describes – the kind that wind up creating a ‘sense of loss’ if one member of the trustor–trustee dyad is taken away. Indeed, affect-based trust can be viewed as a form of ‘mutual benevolence’ – as the consequence of both members of a dyad engaging in caring and concerned behaviour.

The similarities between McAllister’s (1995) affect-based trust conceptualization and Mayer and Davis’s (1999) benevolence conceptualization are helpful, insofar as they allow scholars to picture how results from one model would likely look if examined through the lens of the other model. For example, if affect-based trust was more predictive of some outcome than cognition-based trust in some context, scholars could likely assume that benevolence would be more predictive than either ability or integrity. That said, the fact that McAllister’s (1995) conceptualization incorporates both dyadic behaviours and the feelings that result from those behaviours means that scholars cannot isolate the unique role played by affect. That observation begs the question of what affect-based trust would look like if the ‘affect’ term was taken more literally.

Affect can be described as an umbrella term for the feelings that individuals experience, including in-the-moment states and more cross-situational states (Barsade & Gibson, 2007). One kind of in-the-moment state is mood, a diffuse and low-intensity state that is somewhat unfocused, with no clear cause or target. Moods tend to be classified according to pleasantness (i.e. good or bad) and activation (i.e. high energy or low energy). From this perspective, employees can be in enthusiastic moods (high pleasantness, high activation), relaxed moods (high pleasantness, low activation), depressed moods (low pleasantness, low activation), or nervous moods (low pleasantness, high activation). Another kind of in-the-moment state is emotions, more intense states that have a clear cause and target. Although emotions could be classified in the same way as moods, they tend to be more differentiated, with specific labels, antecedents and conse quences. Those include joy, pride, affection, nostalgia, anger, sadness, fear, resentment and disgust (Barsade & Gibson, 2007; Elfenbein, 2007).

Such feeling states point to an alternative means of conceptualizing affect-based trust, other than mutual benevolence: the covariation of affect and a willingness to be vulnerable. Consider the case of an employee who has been working on an engaging project for most of the day. The employee finds herself in an enthusiastic state – a feeling that could be labelled an emotion if the project was a conscious cause or a mood if the root of the feeling was less salient. Regardless, now presume that some part of the project needs to be delegated to a coworker, creating an opportunity for accepting vulnerability. If that positive mood triggers an intention to delegate, that would be an example of affect-based trust. One could conceive of this affect-based trust occurring directly, with the enthusiasm predicting the willingness to be vulnerable independent of ability, benevolence and integrity. Alternatively, one could conceive of an indirect influence, with enthusiasm shaping perceptions of ability, benevolence and integrity, which would go on to predict the delegation intentions. Of course, negative states could engender affect-based distrust in the same way, with negative moods and emotions reducing intentions to accept vulnerability, either directly or indirectly.

More cross-situational feeling states provide an additional means of conceptualizing affect-based trust. Sentiments are defined as tendencies to respond effectively to a particular person or object (Frijda, 1994; Stets, 2003). If a given person triggers the same emotions again and again, the affect can wind up getting ‘stuck’ to the person, creating a sentiment. Indeed, once created, the sentiment can itself wind up re-triggering the original emotions. Take the example of an employee who winds up working with an old friend from high school. Being around the old friend triggers nostalgia, first at lunch, then at a meeting, then at a sales conference, and so forth. Eventually, the nostalgia transfers from an emotion to a sentiment. If that nostalgia winds up predicting the intention to delegate something to the coworker, it would become one nuanced form of affect-based trust.

Indeed, sentiments could complement another type of trust that has not yet been mentioned in our review: ‘identification-based trust’ (Lewicki & Bunker, 1996; Shapiro, Sheppard, & Cheraskin, 1992). This type of trust occurs when the trustor believes that the trustee shares some common group membership – that he or she is ‘one of us’. As described by Lewicki and Bunker (1996), identification-based trust is even deeper than the trust engendered by ability, benevolence and integrity – a form of trust that they label ‘knowledge-based trust’. Lewicki and Bunker (1996) argued that a sense of shared group membership creates a mutual understanding and an assumption that relevant desires, values and intentions are shared. From an affective perspective, however, it is just as likely that shared group membership engenders pride and affection. Those sentiments may be the ‘active ingredients’ in triggering a willingness to accept vulnerability; not mutual understanding. Alternatively, it may be that the shared group membership removes fear or resentment, preventing the sorts of sentiments that could undermine a willingness to accept vulnerability.

Of course, the value in this more literal conceptualization of affect-based trust rests on this question: can these in-the-moment or more cross-situational feeling states actually predict a willingness to be vulnerable? Fortunately, theories in the affect domain suggest that the answer to that question is ‘yes’. For example, affective events theory suggests that feeling states can shape both evaluative judgments and information processing strategies (Weiss & Cropanzano, 1996). Thus, positive states could make it more likely that trustors will exhibit trusting intentions. Similarly, the affect infusion model argues that affect can ‘fill in the gaps’ for decisions where relevant information is lacking (Forgas, 1995). Thus, if information on a trustee’s ability, benevolence or integrity is missing, a positive feeling state could substitute for that information, thereby engendering a willingness to be vulnerable. Such feeling states could even prime the trustor to more vividly recall positive ability, benevolence or integrity data when weighing whether to trust. Of course, it remains to be seen how powerful such influences would be when controlling for both trust propensity and trustworthiness.

Heuristics

Thus far, our review of the antecedents of trust has reflected the notion that trust has both a cognitive base and an affective base (e.g. Johnson-George & Swap, 1982; Lewicki & Bunker, 1996; Lewis & Weigert, 1985; McAllister, 1995; Rempel et al., 1985). This approach is concisely illustrated by Lewis and Weigert’s (1985) assertion that trust is based on ‘strong positive affect for the object of trust (emotional trust) or on “good rational reasons” why the object of trust merits trust (cognitive trust), or, more usually, some combination of both’ (p. 972). One element that is critical to the creation of both bases is time. In the case of the cog nitive base, the trustor must have had time to gather data on the trustee. In the case of the affective base, the trustor must have had time to develop emotional ties with the trustee. If time is critical to the creation of trust, what explains why people trust in new situations?

It is tempting to rely on the disposition to trust to explain this phenomenon, but recent research indicates that trust propensity is only weakly correlated with organizational newcomers’ initial trust levels (van der Werff & Buckley, in press; see also Berg, Dickhaut, & McCable, 1995; Kramer, 1994). Further, suggesting that trust propensity does not provide an adequate answer to this question, a recent meta-analysis found that the disposition to trust was only weakly to moderately correlated with trusting behaviours in one-shot encounters with strangers (Balliet & Van Lange, 2013). Similarly, people’s participation in trust games has been shown to far exceed their generalized expectations (for a review, see Dunning, Anderson, Schlosser, Ehlebracht, & Fetchenhauer, 2014). In sum, the disposition to trust provides only a partial answer to why people trust in new situations.

A promising answer to this question is provided by a trend in cognitive and social psychology. Scholars in these disciplines have reached a general consensus that reasoning operates through two parallel processes – one that is conscious, deliberate and rational, and one that is less conscious, rapid and heuristic (for a review, see Evans, 2008). Although a number of different terms and theories have been applied to these two processes, they generally fit the labels and characterization provided by Chaiken and colleagues (Chen & Chaiken, 1999: 74; see also Chaiken, 1980; Chaiken, Liberman, & Eagly, 1989): ‘Systematic processing entails a relatively analytic and comprehensive treatment of judgment-relevant information’ whereas ‘heuristic processing, entails the activation and application of judgmental rules or “heuristics” that, like other knowledge structures, are presumed to be learned and stored in memory’ (emphasis in original). To illustrate the two types of processing, consider a professor who is grading an essay. That professor may pore over the essay evaluating the logic and comprehensiveness of the arguments. This analytic evaluation illustrates systematic processing. That professor may also be unknowingly impacted, however, by the length of the essay. Indeed, research indicates that longer arguments activate a ‘length implies strength’ heuristic which has a positive impact on the perceived quality of the arguments (Wood, Kallgren, & Preisler, 1985). This less-conscious evaluation illustrates heuristic processing.

At first glance, the ‘new’ idea of a heuristic base of trust appears to overlap with the not-so-new concept of swift trust (Meyerson, Weick, & Kramer, 1996) and, more recently, the concept of presumptive trust (Kramer & Lewicki, 2010). Both of these concepts bear some similarity to the notion of a heuristic base of trust in that they are formed early in a relationship, before the trustor has had an opportunity to gather specific knowledge about the trustee. Like heuristic-based trust, swift trust – as the label suggests – does not necessarily require much time to form. At this point, however, the concepts diverge. Swift trust is hypothesized to stem from situational cues – e.g. interdependence, fail-safe mechanisms, group membership – that indicate the other group members are unlikely to violate trust. Meyerson et al. (1996) emphasize that this is a calculative, cognitive process. Likewise, Kramer and Lewicki (2010) defined presumptive trust as a positive expectation of an individual stemming from knowledge of that individual’s shared membership in an organization, and what that membership signals. In both cases, these scholars emphasize that rapidly-formed trust stems from a conscious, rule-based, cognitive process – a clear departure from the less-conscious, associative process that characterizes heuristic processing.

Some trust scholars have begun to incorporate the idea of heuristic processing into their research. One of the earliest instances was McKnight et al.’s (1998) theorizing on initial trust formation. Exploring what they referred to as the ‘paradox of high initial trust levels’, McKnight and colleagues proposed that initial trust was based on dispositional trust, structural assurances that trust won’t be violated, and ‘hidden factors’ that signal future endeavours will be successful. With respect to those hidden factors, they introduced the concept of situational normality beliefs – the belief that things are normal, customary and in their proper order. To illustrate the process through which situational normality beliefs should affect trust, they noted that a person who enters a bank expects a setting conducive to safe, professional service. If nothing seems out of the ordinary, the person can rapidly, and with little conscious thought, infer that interactions with that bank will follow established guidelines. It follows that in organizations that exhibit situational normality, the resulting rapid, associative connection between normal and dependable may contribute to the formation of initial trust.

Research on situational normality has been sparse and largely limited to the field of information systems, although the notion of normality acting as a heuristic predictor of trust is supported by empirical research which indicates that ‘normal’ mobile banking technologies and websites increase the likelihood that people will trust (Gefen, Karahanna, & Straub, 2003; Gu, Lee, & Suh, 2009). At the interpersonal level, some additional support comes from recent research that indicates people with typical (i.e. normal) faces are more likely to be trusted (Sofer, Dotsch, Wigboldus, & Todorov, 2015). Scholars have determined that people can form impressions of another’s trustworthiness after as little as 100 milliseconds of exposure to that person’s face, and that additional exposure only serves to increase confidence in those impressions (for a review, see Todorov, Olivola, Dotsch, & Mende-Siedlecki, 2015). When considered through a dual-process lens, these findings provide support for the proposal that trust may also be based on heuristic predictors.

Management researchers have only recently begun to empirically investigate heuristic predictors of trust. One of these investigations was conducted by Rafaeli and colleagues (2008), who found that the presence of an organizational logo increased initial compliance with a request made by a stranger; this relationship was mediated by trust. They argued that this process occurs in an unconscious fashion, with logos activating a heuristic that signals because everything is in proper order, trust is appropriate. Lending support to their argument that initial trust can form without conscious awareness, they found these relationships even when the logo represented a fictitious company. Accordingly, trust could not have been based on prior experience with the company. In related research, Huang and Murnighan (2010) found that subliminally priming participants with the names of trusted people led to greater trust in strangers. Across three experiments, none of the participants recognized the subliminal primes, lending support to the idea that trust can form through automatic, heuristic processing.

We suggest that research into heuristics as a base of trust start by examining the question that is not fully answered by current approaches to trust: Why do employees who are new – either to the group, unit or organization – trust? Research at the interpersonal level clearly shows that physical appearances have a significant impact on people’s initial and lasting impressions of others’ characteristics (for reviews, see Eagly, Ashmore, Makhijani, & Longo, 1991; Langlois, Kalakanis, Rubenstein, Larson, Hallam, & Smoot, 2000; Todorov et al., 2015). Many of these inferred traits are particularly relevant to trust. For example, facial appearance has been found to influence perceptions of warmth and honesty (Berry, 1990), as well as competence (Todorov, Mandisodza, Goren, & Hall, 2005). Much of the research in this vein has explored facial attractiveness, relying on the ‘what is beautiful is good’ heuristic to explain the positive effects (Eagly et al., 1991; Langlois et al., 2000). Other research has investigated the effects of having a baby-faced appearance, with the effects explained by heuristics associated with honesty and naivety (e.g. Zebrowitz & McDonald, 1991). Specifically, baby-faced individuals are seen as more honest yet less competent (Montepare & Zebrowitz, 1998). Other research suggests that men with wider faces cue heuristics associated with aggression, leading to decreased perceptions of trustworthiness and trusting behaviour (Stirrat & Perrett, 2010).

People are largely limited on the extent to which they can alter their appearance to in spire trust. After all, aside from resorting to cosmetic surgery, facial features are relatively fixed. So, when it comes to actionable recommendations for organizations looking to increase em ployee trust in supervisors, does the bottom line become ‘Hire attractive, trustworthy-looking managers?’ Putting aside the ethical implications, this suggestion has dubious practical utility, as the validity of facial inferences has received very little support (Alley, 1988; Cohen, 1973; Hassin & Trope, 2000; Zebrowitz et al., 1996; for exceptions, see Berry, 1990, 1991; Bond, Berry, & Omar, 1994). In other words, selecting trustworthy-looking people doesn’t ensure that trustworthy people have been hired. Accordingly, we suggest that research look to identifying heuristic cues that can be altered rather than selected for, as this approach will provide more actionable recommendations to organizations. One potential direction lies in the ‘power of a smile’. Adding to a robust literature that has demonstrated smiling people are considered more sincere, altruistic and competent (e.g. Brown & Moore, 2002; Reis et al., 1990), scholars have more specifically shown that smiling can increase perceptions of trustworthiness (LaFrance & Hecht, 1995) and trusting behaviour (Krumhuber, Manstead, Cosker, Marshall, Rosin, & Kappas, 2007). In short, there may be considerable benefits to trust for people who ‘turn that frown upside down’.

Other ‘alterable’ heuristic predictors of trust that have received some attention in literatures outside of management include professional dress for physicians (Rehman, Nietert, Cope, & Kilpatrick, 2005), the presence/absence of facial hair in dating relationships (Barber, 2001), and the speed of speech (Miller, Maruyama, Beaber, & Valone, 1976). Whether these and other heuristic predictors predict important systematic variance in trust above and beyond the disposition to trust, trustworthiness and affect is an unanswered question. We suggest that the importance of these heuristic predictors will depend on the research question and stage of trust development. On the one hand, these predictors are more likely to be consequential factors in new relationships. On the other hand, these initial impressions may act as anchors that have lasting effects on trust. Exploration of these issues would contribute to a more complete understanding of the antecedents of trust in individuals.

With respect to individuals’ perceptions of the organization itself, we are unaware of research that has specifically examined trust or trustworthiness as outcomes of appearances. Indeed, despite the growing consensus that the physical environment has a pervasive effect on organizational life (for reviews, see Davis, Leach, & Clegg, 2011; Elsbach & Pratt, 2007; Zhong & House, 2012), organizations often fail to give environmental factors their due attention (Elsbach & Bechky, 2007; Vilnai-Yavetz & Rafaeli, 2006). In contrast with the lack of attention in management research, the field of environmental psychology has long suggested that the physical environment can promote a sense of belonging or ‘place attachment’ (for a review, see Lewicka, 2011a). Recent research indicates that place-attached people tend to place more trust in others in the same environment and to be more benevolent themselves (Lewicka, 2011b). In sum, this research suggests that the physical workplace might have real effects on employee trust. Whether these effects are heuristic or conscious is an unanswered empirical question, although organizational scholars have theorized that they most often occur without conscious awareness (Gagliardi, 2006; Strati, 1999).

In contrast with individuals, organizations seemingly have more – and considerably less invasive – options for altering their appearances in ways that are conducive to trust. After all, it is easier to paint a room and rearrange the office furniture than to alter the width of one’s face. If the environment is supplying heuristic cues that have a meaningful impact on trust, organizations would be wise to give more thoughtful attention to logistical decisions such as where new employees will be trained and located. Yet, what are the specific aspects of the physical environment that might have a heuristic effect on trust? One potential answer is the extent to which the environment is aesthetically pleasing. Although research is silent on this issue, just as attractive people cue a ‘what is beautiful is good’ heuristic (Eagly et al., 1991; Langlois et al., 2000), aesthetically-pleasing workplaces may signal that the organization is ‘good’ and, therefore, worthy of trust. Given the wide range of aesthetic preferences, crafting a universally pleasing and trust-inducing appearance may seem like an impossible venture. Fortunately, research indicates that some design elements are generally widely appreciated, including the presence of windows, a uniform color palette and high ceilings (Gifford, Hine, Muller-Clemm, D’Arcy, & Shaw, 2000).

Conclusion

Despite the many important strides that have been made in identifying and exploring the antecedents of trust, many unanswered questions remain. We have suggested that the more deeply explored antecedents of trust – trust propensity and trustworthiness – still hold questions that bear addressing. Answers to these questions may provide organizations with greater ability to increase trust with the organization through various means, such as selection and training. Although not a ‘new’ conceptual direction for trust research, affect is a relatively unexplored direction for empirical trust research. Attending to the issues raised in this chapter may provide additional avenues for increasing trust. Indeed, the traditionally cognitive approach may have been ignoring a substantial opportunity to improve trust within organizations. Likewise, an inattention to less-conscious, heuristic predictors has left our understanding of initial trust formation in the dark. By exploring the rapid, heuristic judgments that characterize initial impressions, organizations may be able to affect initial trust levels, which in turn may have lasting implications. In sum, a more conscious acknowledgement of all the bases of trust should provide organizations with the ability to take a holistic approach to forming and maintaining trust among employees, coworkers, supervisors and the organization.

References

Alley, T. R.

1988. Physiognomy and social perception. In T. R. Alley (Ed.), Social and applied aspects of perceiving faces: 167–186. Hillsdale, NJ: Erlbaum.

Balliet, D., & Van Lange, P. A. M.

2013. Trust, conflict, and cooperation: A meta-analysis. Psychological Bulletin, 139: 1090–1112.

Barber, B.

1983. The logic and limits of trust. New Brunswick, NJ: Rutgers University Press.

Barber, N.

2001. Mustache fashion covaries with a good marriage market for women. Journal of Nonverbal Behavior, 25: 261–272.

Barsade, S. G., & Gibson, D. E.

2007. Why does affect matter in organizations?

Academy of Management Perspectives, 21: 36–59.

Berg, J., Dickhaut, J., & McCabe, K.

1995. Trust, reciprocity, and social history. Games and Economic Behavior, 10: 122–142.

Berry, D. S.

1990. Taking people at face value: Evidence for the kernel of truth hypothesis. Social Cognition, 8: 343–361.

Berry, D. S.

1991. Accuracy in social perception: Contributions of facial and vocal information. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 61: 298–307.

Bigley, G. A., & Pearce, J. L.

1998. Straining for shared meaning in organization science: Problems of trust and distrust. Academy of Management Review, 23: 405–421.

Bond, C. F., Berry, D. S., & Omar, A.

1994. The kernel of truth in judgments of deceptiveness. Basic and Applied Social Psychology, 15: 523–534.

Brown, W. M., & Moore, C.

2002. Smile asymmetries and reputation as reliable indicators of likelihood to cooperate: An evolutionary analysis. Advances in Psychology Research, 11: 59–78.

Butler, J. K., Jr.

1991. Toward understanding and measuring conditions of trust: Evolution of a conditions of trust inventory. Journal of Management, 17: 643–663.

Butler, J. K., Jr., & Cantrell, R. S.

1984. A behavioral decision theory approach to modeling dyadic trust in superiors and subordinates. Psychological Reports, 55: 19–28.

Chaiken, S.

1980. Heuristic versus systematic information processing and the use of source versus message cues in persuasion. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 39: 752–766.

Chaiken, S., Liberman, A., & Eagly, A. H.

1989. Heuristic and systematic processing within and beyond the persuasion context. In J. S. Uleman & J. A. Bargh (Eds.), Unintended thought: 212–252. New York: Guilford Press.

Chen, S., & Chaiken, S.

1999. The heuristic-systematic model in its broader context. In S. Chaiken & Y. Trope (Eds.), Dual-process theories in social psychology: 73–96. New York: Guilford Press.

Cohen, R.

1973. Patterns of personality judgments. New York: Academic Press.

Colquitt, J. A., Baer, M. D., Long, D. M., & Halvorsen-Ganepola, M. D. K.

2014. Scale indicators of social exchange relationships: A comparison of relative content validity. Journal of Applied Psychology, 99: 599–618.

Colquitt, J. A., LePine, J. A., Zapata, C. P., & Wild, R. E.

2011. Trust in typical and high-reliability contexts: Building and reacting to trust among firefighters. Academy of Management Journal, 54: 999–1015.

Colquitt, J. A., Scott, B. A., & LePine, J. A.

2007. Trust, trustworthiness, and trust propensity: A meta-analytic test of their unique relationships with risk taking and job performance. Journal of Applied Psychology, 92: 902–927.

Cook, J., & Wall, T.

1980. New work attitude measures of trust, organizational commitment and personal need non-fulfillment. Journal of Occupational Psychology, 53: 39–52.

Davis, M. C., Leach, D. J., & Clegg, C. W.

2010. The physical environment of the office: Contemporary and emerging issues. International Review of Industrial and Organizational Psychology, 26: 193–237.

Deutsch, M., & Krauss, R. M.

1965. Theories in social psychology. New York: Basic Books.

Dietz, G., & Den Hartog, D. N.

2006. Measuring trust inside organisations. Personnel Review, 35: 557–588.

Dirks, K. T., & Ferrin, D. L.

2002. Trust in leadership: Meta-analytic findings and implications for research and practice. Journal of Applied Psychology, 87: 611–628.

Dunn, J. R., & Schweitzer, M. E.

2005. Feeling and believing: The influence of emotion on trust. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 88: 736–748.

Dunning, D., Anderson, J. E., Schlösser, T., Ehlebracht, D., & Fetchenhauer, D.

2014. Trust at zero acquaintance: More a matter of respect than expectation of reward. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 107: 122–141.

Eagly, A. H., Ashmore, R. D., Makhijani, M. G., & Longo, L. C.

1991. What is beautiful is good, but …: A meta-analytic review of research on the physical attractiveness stereotype. Psychological Bulletin, 110: 109–128.

Elfenbein, H. A.

2007. Emotion in organizations: A review and theoretical integration. Academy of Management Annals, 1: 371–457.

Elsbach, K. D., & Bechky, B. A.

2007. It’s more than a desk: Working smarter through leveraged office design. California Management Review, 49: 80–101.

Elsbach, K. D., & Pratt, M. G.

2007. The physical environment in organizations. Academy of Management Annals, 4: 181–224.

Erikson, E. H.

1963. Childhood and society. New York: Norton.

Evans, J. S. B. T.

2008. Dual-processing accounts of reasoning, judgment, and social cognition. Annual Review of Psychology, 59: 255–278.

Flanagan, C. A., & Stout, M.

2010. Developmental patterns of social trust between early and late adolescence: Age and school climate effects. Journal of Research on Adolescence, 20: 748–773.

Fleeson, W., & Jolley, S.

2006. A proposed theory of the adult development of intraindividual variability in trait-manifesting behavior. In D. K. Mroczek & T. D. Little (Eds.), Handbook of personality development: 41–59. Mahwah, NJ: Erlbaum.

Forgas, J. P.

1995. Mood and judgment: The affect infusion model (AIM). Psychological Bulletin, 117: 39–66.

Frijda, N. H.

1994. Varieties of affect: Emotions and episodes, moods, and sentiments. In P. Ekman & R. J. Davidson (Eds.), The nature of emotion: 59–67. New York: Oxford University Press.

Frost, T., Stimpson, D. V., & Maughan, M. R. C.

1978. Some correlates of trust. Journal of Psychology, 99: 103–108.

Fulmer, C. A., & Gelfand, M. J.

2012. At what level (and in whom) we trust: Trust across multiple organizational levels. Journal of Management, 38: 1167–1230.

Gabarro, J. J.

1978. The development of trust, influence, and expectations. In A. G. Athos & J. J. Gabarro (Eds.), Interpersonal behaviors: Communication and understanding in relationships: 290–303. Englewood Cliffs, NJ: Prentice Hall.

Gagliardi, P.

2006. Exploring the aesthetic side of organizational life. In S. R. Clegg, C. Hardy, T. B. Lawrence, & W. R. Nord (Eds.), The SAGE handbook of organizations studies: 701–724. London: SAGE.

Gefen, D., Karahanna, E., & Straub, D. W.

2003. Trust and TAM in online shopping: An integrated model. MIS Quarterly, 27: 51–90.

Gifford, R., Hine, D. W., Muller-Clemm, W., D’Arcy, J. R., & Shaw, K. T.

2000. Decoding modern architecture: A lens model approach for understanding the aesthetic differences of architects and laypersons. Environment and Behavior, 32: 163–187.

Gill, H., Boies, K., Finegan, J. E., & McNally, J.

2005. Antecedents of trust: Establishing a boundary condition for the relation between propensity to trust and intention to trust. Journal of Business and Psychology, 19: 287–302.

Gu, J.-C., Lee, S.-C., & Suh, Y.-H.

2009. Determinants of behavioral intention to mobile banking. Expert Systems with Applications, 36: 11605–11616.

Hardin, R.

1992. The street-level epistemology of trust. Analyse & Kritik, 14: 152–176.

Hardin, R.

2002. Trust and trustworthiness. New York: Russell Sage Foundation.

Hassin, R., & Trope, Y.

2000. Facing faces: Studies on the cognitive aspects of physiognomy. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 78: 837–852.

Hill, C. A.

1987. Affiliation motivation: People who need people … but in different ways. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 52: 1008–1018.

Hill, C. A.

1991. Seeking emotional support: The influence of affiliative need and partner warmth. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 60: 112–121.

Hiraishi, K., Yamagata, S., Shikishima, C., & Ando, J.

2008. Maintenance of genetic variation in personality through control of mental mechanisms: A test of trust extraversion, and agreeableness. Evolution and Human Behavior, 29: 79–85.

Hovland, C. I., Janis, I. L., & Kelley, H. H.

1953. Communication and persuasion. New Haven: Yale University Press.

Huang, L., & Murnighan, J. K.

2010. What’s in a name? Subliminally activating trusting behavior. Organizational Behavior and Human Decision Processes, 111: 62–70.

Jennings, E. E.

1971. Routes to the executive suite. New York: McGraw-Hill.

Johnson-George, C., & Swap, W.

1982. Measurement of specific interpersonal trust: Construction and validation of a scale to assess trust in a specific other. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 43: 1306–1317.

Jones, G. R., & George, J. M.

1998. The experience and evolution of trust: Implications for cooperation and teamwork. Academy of Management Review, 23: 531–546.

Judge, T. A., Simon, L. S., Hurst, C., & Kelley, K.

2014. What I experienced yesterday is who I am today: Relationship of work motivations and behaviors to within-individual variation in the Five-Factor model of personality. Journal of Applied Psychology, 99: 199–221.

Katz, H. A., & Rotter, J. B.

1969. Interpersonal trust scores of college students and their parents. Child Development, 40: 657–661.

Kee, H. W., & Knox, R. E.

1970. Conceptual and methodological considerations in the study of trust and suspicion. Journal of Conflict Resolution, 14: 357–366.

Korsgaard, M. A., Brodt, S. E., & Whitener, E. M.

2002. Trust in the face of conflict: The role of managerial trustworthy behavior and organizational context. Journal of Applied Psychology, 87: 312–319.

Kramer, R. M.

1994. The sinister attribution error: Paranoid cognition and collective distrust in organizations. Motivation and Emotion, 18: 199–230.

Kramer, R. M.

1999. Trust and distrust in organizations: Emerging perspectives, enduring questions. Annual Review of Psychology, 50: 569–598.

Kramer, R. M., & Lewicki, R. J.

2010. Repairing and enhancing trust: Approaches to reducing organizational trust deficits. Academy of Management Annals, 4: 245–277.

Krumhuber, E., Manstead, A. S. R., Cosker, D., Marshall, D., Rosin, P. L., & Kappas, A.

2007. Facial dynamics and indicators of trustworthiness and cooperative behavior. Emotion, 7: 730–735.

LaFrance, M., & Hecht, M. A.

1995. Why smiles generate leniency. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, 21: 207–214.

Langlois, J. H., Kalakanis, L., Rubenstein, A. J., Larson, A., Hallam, M., & Smoot, M.

2000. Maxims or myths of beauty? A meta-analytic and theoretical review. Psychological Bulletin, 126: 390–423.

Larzelere, R., & Huston, T.

1980. The dyadic trust scale: Toward understanding interpersonal trust in close relationships. Journal of Marriage and the Family, 42: 595–604.

Lee, M. K. O., & Turban, E.

2001. A trust model for consumer Internet shopping. International Journal of Electronic Commerce, 6: 75–91.

Lewicka, M.

2011a. Place attachment: How far have we come in the last 40 years?

Journal of Environmental Psychology, 31: 207–230.

Lewicka, M.

2011b. On the varieties of people’s relationships with places: Hummon’s typology revisited. Environment and Behavior, 43: 676–709.

Lewicki, R. J., & Bunker, B. B.

1996. Developing and maintaining trust in work relationships. In R. M. Kramer & T. R. Tyler (Eds.), Trust in organizations: Frontiers of theory and research: 114–139. Thousand Oaks, CA: SAGE.

Lewis, J. D., & Weigert, A.

1985. Trust as a social reality. Social Forces, 63: 967–985.

Liden, R. C., & Maslyn, J. M.

1998. Multidimensionality of leader-member exchange: An empirical assessment through scale development. Journal of Management, 24: 43–72.

Lindskold, S., & Bennett, R.

1973. Attributing trust and conciliatory intent from coercive power capability. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 28: 180–186.

Mayer, R. C., & Davis, J. H.

1999. The effect of the performance appraisal system on trust for management: A field quasi-experiment. Journal of Applied Psychology, 84: 123–136.

Mayer, R. C., Davis, J. H., & Schoorman, F. D.

1995. An integrative model of organizational trust. Academy of Management Review, 20: 709–734.

McAllister, D. J.

1995. Affect and cognition-based trust as foundations for interpersonal cooperation in organizations. Academy of Management Journal, 38: 24–59.

McCrae, R. R., & Costa, P. T.

1994. The stability of personality: Observations and evaluations. Current Directions in Psychological Science, 3: 173–175.

McEvily, B., & Tortoriello, M.

2011. Measuring trust in organisational research: Review and recommendations. Journal of Trust Research, 1: 23–63.

McKnight, D. H., Cummings, L. L., & Chervany, N. L.

1998. Initial trust formation in new organizational relationships. Academy of Management Review, 23: 473–490.

Meyerson, D., Weick, K. E., & Kramer, R. M.

1996. Swift trust and temporary groups. In R. M. Kramer & T. R. Tyler (Eds.), Trust in organizations: Frontiers of theory and research: 166–195. Thousand Oaks, CA: SAGE.

Miller, N., Maruyama, G., Beaber, R. J., Valone, K.

1976. Speed of speech and persuasion. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 34: 615–624.

Mishra, A. K.

1996. Organizational responses to crisis: The centrality of trust. In R. M. Kramer & T. R. Tyler (Eds.), Trust in organizations: Frontiers of theory and research: 261–287. Thousand Oaks, CA: SAGE.

Möllering, G.

2006. Trust: Reason, routine, reflexivity. Amsterdam, the Netherlands: Elsevier.

Montepare, J. M., & Zebrowitz, L. A.

1998. Person perception comes of age: The salience and significance of age in social judgments. In M. P. Zanna (Ed.), Advances in experimental social psychology (vol. 30): 93–161. San Diego, CA: Academic Press.

Pirson, M., & Malhotra, D.

2011. Foundations of organizational trust: What matters to different stakeholders?

Organization Science, 22: 1087–1104.

Rafaeli, A., Sagy, Y., & Derfler-Rozin, R.

2008. Logos and initial compliance: A strong case of mindless trust. Organization Science, 19: 845–859.

Rehman, S. U., Nietert, P. J., Cope, D. W., & Kilpatrick, A. O.

2005. What to wear today? Effect of doctor’s attire on the trust and confidence of patients. The American Journal of Medicine, 118: 1279–1286.

Reis, H. T., Wilson, I., Monestere, C., Bernstein, S., Clark, K., Seidl, E., Franco, M., Gioioso, E., Freeman, L., & Radoane, K.

1990. What is smiling is beautiful and good. European Journal of Social Psychology, 20: 259–267.

Rempel, J. K., Holmes, J. G., & Zanna, M. P.

1985. Trust in close relationships. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 49: 95–112.

Rotter, J. B.

1967. A new scale for the measurement of interpersonal trust. Journal of Personality, 35: 651–665.

Rotter, J. B.

1971. Generalized expectancies for interpersonal trust. American Psychologist, 26: 443–452.

Rotter, J. B.

1980. Interpersonal trust, trustworthiness, and gullibility. American Psychologist, 35: 1–7.

Rotter, J. B., Chance, J., & Phares, E. J.

1972. Applications of a social learning theory of personality. New York: Holt, Rinehart, & Winston.

Rousseau, D. M., Sitkin, S. B., Burt, R. S., & Camerer, C.

1998. Not so different after all: A crossdiscipline view of trust. Academy of Management Review, 23: 393–404.

Sakai, A.

2010. Children’s sense of trust in significant others: Genetic versus environmental contributions and buffer to life stressors. In K. J. Rotenberg (Ed.), Interpersonal trust during childhood and adolescence: 56–84. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press.

Schlenker, B. R., Helm, B., & Tedeschi, J. T.

1973. The effects of personality and situational variables on behavioral trust. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 25: 419–427.

Shapiro, D., Sheppard, B. H., & Cheraskin, L.

1992. Business on a handshake. The Negotiation Journal, 8: 365–378.

Simons, T.

2002. Behavioral integrity: The perceived alignment between manager’s words and deeds as a research focus. Organization Science, 13: 18–35.

Sitkin, S. B., & Pablo, A. L.

1992. Reconceptualizing the determinants of risk behavior. Academy of Management Review, 17: 9–38.

Sitkin, S. B., & Roth, N. L.

1993. Explaining the limited effectiveness of legalistic “remedies” for trust/ distrust. Organization Science, 4: 367–392.

Sitkin, S. B., & Weingart, L. R.

1995. Determinants of risky decision-making behavior: A test of the mediating role of risk perceptions and propensity. Academy of Management Journal, 38: 1573–1592.

Sofer, C., Dotsch, R., Wigboldus, D. H. J., & Todorov, A.

2015. What is typical is good: The influence of face typicality on perceived trustworthiness. Psychological Science, 26: 39–47.

Stack, L. C.

1978. Trust. In H. London & J. E. Exner, Jr. (Eds.), Dimensionality of personality: 561–599. New York: Wiley.

Stets, J. E.

2003. Emotions and sentiments. In J. DeLamater (Ed.), Handbook of social psychology: 309–335. New York: Kluwer Academic/Plenum Publishers.

Stirrat, M., & Perrett, D. I.

2010. Valid facial cues to cooperation and trust: Male facial width and trustworthiness. Psychological Science, 21: 349–354.

Stolle, D., & Nishikawa, L.

2011. Trusting others—How parents shape the generalized trust of their children. Comparative Sociology, 10: 281–314.

Strati, A.

1999. Organization and aesthetics. London: SAGE.

Sturgis, P., Read, S., Hatemi, P. K., Zhu, G., Trull, T., Wright, M. J., & Martin, N. G.

2010. A genetic basis for social trust. Political Behavior, 32: 205–230.

Todorov, A., Mandisodza, A. N., Goren, A., & Hall, C. C.

2005. Inferences of competence from faces predict election outcomes. Science, 308: 1623–1626.

Todorov, A., Olivola, C. Y., Dotsch, R., & Mende-Siedlecki, P.

2015. Social attributions from faces: Determinants, consequences, accuracy, and functional significance. Annual Review of Psychology, 66: 519–545.

van der Werff, L., & Buckley, F.

2017. Getting to know you: A longitudinal examination of trust cues and trust development during socialization. Journal of Management, 43: 742–770.

Vilnai-Yavetz, I., & Rafaeli, A.

2006. Managing organizational artifacts to avoid artifact myopia. In A. Rafaeli & M. G. Pratt (Eds.), Artifacts and organizations: Beyond mere symbolism: 9–21. Mahwah, NJ: Erlbaum.

Webb, W. M., & Worchel, P.

1986. Trust and distrust. In S. Worchel & W. G. Austin (Eds.), Psychology of intergroup relations: 213–228. Chicago: Nelson-Hall.

Weiss, H. M., & Cropanzano, R.

1996. Affective events theory: A theoretical discussion of the structure, causes and consequences of affective experiences at work. Research in Organizational Behavior, 18: 1–74.

Whitener, E. M., Brodt, S. E., Korsgaard, M. A., & Werner, J. M.