appendix B pest and disease control

The following sections cover a large number of pests and diseases. An individual gardener, however, will encounter few such problems in a lifetime of gardening. Good garden planning, good hygiene, and an awareness of major symptoms will keep problems to a minimum and give you many hours to enjoy your garden and feast on its bounty.

Pest Control

There are some spoilers, though, which sometimes need control. For years controls were presented as a list of critters and diseases, followed by the newest and best chemical to control them. But times have changed, and we now know that chasing the latest chemical to fortify our arsenal is a bit like chasing our tail. That’s because most pesticides, both insecticides and fungicides, kill beneficial insects as well as the pests; therefore, the more we spray, the more we are forced to spray. Nowadays, we’ve learned that successful pest control focuses on prevention, plus beefing up the natural ecosystem so beneficial insects are on pest patrol. How does that translate to pest control for the vegetable garden directly?

1. When possible, seek resistant varieties—for example, in cold, wet weather choose lettuce varieties resistant to downy mildew, and if fungal diseases are a problem in your garden, select disease-resistant varieties of tomatoes.

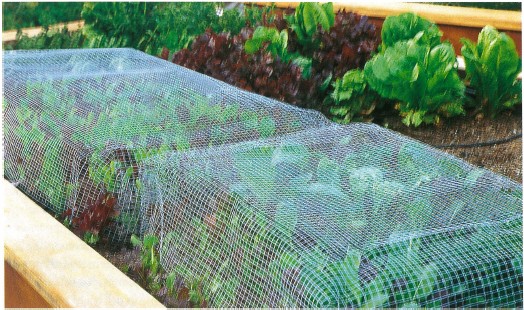

2. Use mechanical means to prevent insect pests from damaging the plants. For example, cover young squash and eggplants with floating row covers to keep away squash borers and flea beetles; sprinkle wood ashes around plants to prevent cabbage root maggot and slug damage; and put cardboard collars around young tomato, pepper, cabbage, and squash seedlings to prevent cutworms from destroying them.

3. Clean up diseased foliage and dispose of it in the garbage to cut down on the cycle of infection.

4. Rotate your crops so that plants from the same family are not planted in the same place for two consecutive seasons.

5. Encourage and provide food for beneficial insects. In the vegetable garden this translates to letting a few selected vegetables go to flower and growing flowering herbs and ornamentals to provide a season-long source of nectar and pollen for beneficial insects.

Beneficial Insects

In a nutshell, few insects are potential problems; most are either neutral or beneficial to the gardener. Given the chance, the beneficials do much of your insect control for you, provided that you don’t use pesticides, as pesticides are apt to kill the beneficial insects as well as the problem insects. Like predatory lions stalking zebra, predatory ladybugs (lady beetles) or lacewing larvae hunt and eat aphids that might be attracted to your lettuce, say. Or a miniwasp parasitoid will lay eggs in the aphids. If you spray those aphids, even with a so-called benign pesticide such as insecticidal soap or pyrethrum, you’ll kill off the ladybugs, lacewings, and that baby parasitoid wasp too. Most insecticides are broad spectrum, which means that they kill insects indiscriminately, not just the pests. In my opinion, organic gardeners who regularly use organic broad-spectrum insecticides have missed this point. While it is true they are using an “organic” pesticide, they may actually be eliminating a truly organic means of control, the beneficial insects.

Unfortunately, many gardeners are not aware of the benefits of the predator-prey relationship and are not able to recognize beneficial insects. The following sections will help you identify both helpful and pest organisms. A more detailed aid for identifying insects is Rodale’s Color Handbook of Garden Insects, by Anna Carr. A hand lens is an invaluable and inexpensive tool that will also help you identify the insects in your garden.

Predators and Parasitoids: Insects that feed on other insects are divided into two types, the predators and the parasitoids. Predators are mobile. They stalk plants looking for such plant feeders as aphids and mites. Parasitoids, on the other hand, are insects that develop in or on the bodies, pupae, or eggs of other host insects. Most parasitoids are minute wasps or flies whose larvae (young stages) eat other insects from within. Some of the wasps are so small, they can develop within an aphid or an insect egg. Or one parasitoid egg can divide into several identical cells, each developing into identical miniwasp larvae, which then can kill an entire caterpillar. Though nearly invisible to most gardeners, parasitoids are the most specific and effective means of insect control.

The predator-prey relationship can be a fairly stable situation; when the natural system is working properly, pest insects inhabiting the garden along with the predators and parasitoids seldom become a problem. Sometimes, though, the system breaks down. For example, a number of imported pests have taken hold in this country. Unfortunately, when such organisms were brought here, their natural predators did not accompany them. Four pesky examples are Japanese beetles, the European brown snail, the white cabbage butterfly, and flea beetles. None of these organisms has natural enemies in this country that provide sufficient controls. Where they occur, it is sometimes necessary to use physical means or selective pesticides that kill only the problem insect. Weather extremes sometime produce imbalances as well. For example, long stretches of hot, dry weather favor grasshoppers that invade vegetable gardens, because the diseases that keep them in check are more prevalent under moist conditions. There are other situations in which the predator-prey relationship gets out of balance because many gardening practices inadvertently work in favor of the pests. For example, when gardeners spray with broad-spectrum pesticides regularly, not all the insects in the garden are killed—and since predators and parasitoids generally reproduce more slowly than do the pests, regular spraying usually tips the balance in favor of the pests. Further, all too often the average yard has few plants that produce nectar for beneficial insects; instead it is filled with grass and shrubs, so that when a few squash plants and a row of lettuces are put in, the new plants attract the aphids but not the beneficials. Being aware of the effect of these practices will help you create a vegetable garden that is relatively free of many pest problems.

Attracting Beneficial Inserts: Besides reducing your use of pesticides, the key to keeping a healthy balance in your garden is providing a diversity of plants, including plenty of nectar- and pollen-producing plants. Nectar is the primary food of the adult stage and some larval stages of many beneficial insects. Interplanting your vegetables with flowers and numerous herbs helps attract them. Ornamentals, like species zinnias, marigolds, alyssum, and yarrow, provide many flowers over a long season and are shallow enough for insects to reach the nectar. Large, dense flowers like tea roses and dahlias are useless as their nectar is out of reach. A number of the herbs are rich nectar sources, including fennel, dill, anise, chervil, oregano, thyme, and parsley. Allowing a few of your vegetables like arugula, broccoli, carrots, and mustards, in particular, to go to flower is helpful because their tiny flowers full of nectar and pollen are just what many of the beneficial insects need.

Following are a few of the predatory and parasitoid insects that are helpful in the garden. Their preservation and protection should be a major goal of your pest-control strategy.

Ground beetles and their larvae are all predators. Most adult ground beetles are fairly large black beetles that scurry out from under plants or containers when you disturb them. Their favorite foods are soft-bodied larvae like Colorado potato beetle larvae and root maggots (root maggots eat cabbage family plants); some ground beetles even eat snails and slugs. If supplied with an undisturbed place to live, like your compost area or groupings of perennial plantings, ground beetles will be long-lived residents of your garden.

Lacewings are one of the most effective insect predators in the home garden. They are small green or brown gossamer-winged insects that in their adult stage eat flower nectar, pollen, aphid honeydew, and sometimes aphids and mealybugs. In the larval stage they look like little tan alligators. Called aphid lions, the larvae are fierce predators of aphids, mites, and white-flies—all occasional pests that suck plant sap. If you are having problems with sucking insects in your garden, consider purchasing lacewing eggs or larvae mail-order to jump-start your lacewing population. Remember to plant lots of nectar plants to keep the population going from year to year.

Lady beetles (ladybugs) are the best known of the beneficial garden insects. Actually, there are about four hundred species of lady beetles in North America alone. They come in a variety of colors and markings in addition to the familiar red with black spots, but they are never green. Lady beetles and their fierce-looking alligator-shaped larvae eat copious amounts of aphids and other small insects.

Spiders are close relatives of insects. There are hundreds of species, and they are some of the most effective predators of a great range of pest insects.

Syrphid flies (also called flowerflies or hover flies) look like small bees hovering over flowers, but they have only two wings. Most have yellow and black stripes on their body. Their larvae are small green maggots that inhabit leaves, eating small sucking insects and mites.

Wasps are a large family of insects with transparent wings. Unfortunately, the few large wasps that sting have given wasps a bad name. In fact, all wasps are either insect predators or parasitoids. The miniwasps are usually parasitoids, and the adult female lays her eggs in such insects as aphids, whitefly larvae, and caterpillars—and the developing wasp larvae devour the host. These miniature wasps are also available for purchase from insectaries and are especially effective when released in greenhouses.

Pests

The following pests are sometimes a problem in the vegetable garden.

Aphids are soft-bodied, small, green, black, pink, or gray insects that produce many generations in one season. They suck plant juices and exude honeydew. Sometimes leaves under the aphids turn black from a secondary mold growing on the nutrient-rich honeydew. Aphids are primarily a problem on cabbages, broccoli, beans, lettuces, peas, tomatoes, and spinach. Aphid populations can build up, especially in the spring before beneficial insects are present in large numbers and when plants are covered by row covers or are growing in cold frames. The presence of aphids sometimes indicates that the plant is under stress—is the cabbage getting enough water, or sunlight, say? Check first to see if stress is a problem and then try to correct it. If there is a large infestation, look for aphid mummies and other natural enemies mentioned above. Mummies are swollen brown or metallic-looking aphids. Inside the mummy a wasp parasitoid is growing. They are valuable, so keep them. To remove aphids generally, wash the foliage with a strong blast of water and cut back the foliage if they persist. Fertilize and water the plant, and check on it in a few days. Repeat with the water spray a few more times. In extreme situations spray with insecticidal soap or a neem product.

A number of beetles are garden pests. They include asparagus beetles, Mexican bean beetles, different species of cucumber beetles, flea beetles, and wireworms (the larvae of click beetles). All are a problem throughout most of North America. Colorado potato beetles and Japanese beetles are primarily a problem in the eastern United States. Asparagus beetles look like elongated red lady beetles with a black-and-cream-colored cross on their back, and they feed on asparagus. Mexican bean beetles look like brown lady beetles with oval black spots; as their name implies, they feed on beans. Cucumber beetles are ladybug-like green or yellow-green beetles with either black stripes or black spots. Their larvae feed on the roots of corn and other vegetables. Adults devour members of the cucumber family, corn tassels, beans, and some salad greens. Flea beetles are minuscule black-and-white-striped beetles hardly big enough to be seen. The grubs feed on the roots and lower leaves of many vegetables, and the adults chew on the leaves of eggplants, tomatoes, potatoes, radishes, and peppers—causing the leaves to look shot full of tiny holes. The adult click beetle is rarely seen, and its young, a brown, 1½-inch-long shiny larva called a wireworm, works underground and damages tubers, seeds, and roots. Colorado potato beetles are larger and rounder than lady beetles and have red-brown heads and black-and-yellow-striped backs. They are primarily a problem in the East, where they skeletonize the leaves of potatoes, tomatoes, peppers, and eggplants. Japanese beetles, a problem east of the Mississippi, are fairly large metallic blue or green beetles with coppery wings. The larval stage (a grub) lives on the roots of grasses, and the adult chews its way through bean and asparagus plants and many ornamentals.

The larger beetles, if not in great numbers, can be controlled by hand picking—in the morning is best, when the beetles are slower. Knock them into a bowl of soapy water. Flea beetles are too small to gather by hand; try a hand-held vacuum instead. Insecticidal soap on the underside of the leaves is also effective on flea beetles. Wireworms can be trapped by putting cut pieces of potatoes (or carrots) every five feet or so in the soil and then digging them up after a few days. Destroy the worms. Colorado potato beetles can be controlled, when young, by applications of Bacillus thuringiensis, var. san diego, a beetle Bt that has also proven effective for flea beetles.

Because most beetle species winter over in the soil, either as eggs or adults, crop rotation and fall cleanup becomes vital. New evidence indicates that beneficial nematodes are effective in controlling most beetles if applied during their soil-dwelling larval stage. Azadirachtin (the active ingredient in some formulations of neem) is also affective against the immature stage of most beetles and can act as a feeding deterrent for adults. Polyester row covers securely fastened to the ground can provide excellent control from most beetles. Obviously, row covers are of no use if the beetles are in a larval stage and ready to emerge from the soil under the row cover or if the adults are already established on the plant. This technique works best in combination with crop rotation. It has limited use on plants (such as cucumbers, squash, and melons) that need bees to pollinate the blooms, since bees also are excluded. Japanese beetle populations can also be reduced by applications of milky-spore, a naturally occurring soil-borne disease that infects the beetle in its grub stage—though the disease is slow to work. The grubs primarily feed in lawns; the application of lime, if your lawn is acidic, has been reported to help control grubs, too.

Caterpillars (sometimes called loopers and “worms”) are the immature stage of moths and butterflies. Most pose no problem in our gardens and we encourage them to visit, but a few are a problem in the vegetable garden. The most notorious are the tomato hornworm, beanloopers, cutworms, and the numerous cabbage worms and loopers that chew ragged holes in leaves. Natural controls include birds, wasps, and disease. Encourage birds by providing a birdbath, shelter, and berry-producing shrubs. Tolerate wasp nests if they’re not a threat, and provide nectar plants for the miniwasps. Hand picking is very effective as well. The disease Bacillus thuringiensis, var. kurstaki is available as a spray in a number of formulations. Brands include Bt kurstaki, Dipel, and Thuricide. It is a bacteria that, if applied when the caterpillar is fairly young, causes it to starve to death. Bt-k Bait contains the disease and lures budworms away from vegetables and to it. I seldom use Bt in any form, as it also kills all butterfly and harmless moth larvae.

Cutworms are the caterpillar stage of various moth species. They are usually found in the soil and curl up into a ball when disturbed. Cutworms are a particular problem on annual vegetables when the seedlings first appear or when young transplants are set out. The cutworm often chews off the stem right at the soil line, killing the plant. Control cutworms by using cardboard collars or bottomless tin cans around the plant stem; be sure to sink these collars 1 inch into the ground. Bacillus thuringiensis gives limited control. Trichogramma miniwasps and black ground beetles are among cutworms natural enemies and are often not present in a new garden.

Leaf miners tunnel through leaves, disfiguring them by causing patches of dead tissue where they feed; they do not burrow into the root. Leaf miners are the larvae of a small fly and can be controlled somewhat by neem or by applying beneficial nematodes.

Mites are among the few arachnids (spiders and their kin) that pose a problem. Mites are so small that a hand lens is usually needed to see them. They become a problem when they reproduce in great numbers. A symptom of serious mite damage is stippling on the leaves in the form of tiny white or yellow spots, sometimes accompanied by tiny webs. The major natural predators of pest mites are predatory mites, mite-eating thrips, and syrphid flies.

Rotting lettuce showing snail damage

Mites are most likely to thrive on dusty leaves and in warm weather. A routine foliage wash and misting of sensitive vegetables helps control mites. Mites are seldom a serious problem unless heavy-duty pesticides that kill off predatory mites have been used or plants are grown in the house. Cut back the plants and if you’re using heavy-duty pesticides, stop the applications, and the balance could return. If all else fails, use the neem derivative Green Light Fruit, Nut, and Vegetable Spray or dispose of the plant.

Nematodes are microscopic round worms that inhabit the soil in most of the United States, particularly in the Southeast. Most nematode species live on decaying matter or are predatory on other nematodes, insects, or bacteria. A few types are parasitic, attaching themselves to the roots of plants. Edible plants particularly susceptible to nematode damage include beans, melons, eggplant, lettuce, okra, pepper, squash, tomatoes, and some perennial herbs. The symptoms of nematode damage are stunted-looking plants and small swellings or lesions on the roots.

Rotate annual vegetables with less-susceptible varieties; plant contaminated beds with a blanket of marigolds for a whole season; keep your soil high in organic matter (to encourage fungi and predatory nematodes, both of which act as biological controls); or if all else fails, grow edibles in containers with sterilized soil.

Snails and slugs are not insects, of course, but mollusks. They are especially fond of greens and seedlings of most vegetables. They feed at night and can go dormant for months in times of stress. In the absence of effective natural enemies (a few snail eggs are consumed by predatory beetles and earwigs), several snail-control strategies can be recommended. Since snails and slugs are most active after rain or irrigation, go out and destroy them on such nights. Only repeated forays provide adequate control. Hardwood ashes dusted around susceptible plants gives some control. A strip of copper applied along the top perimeter boards of planter boxes effectively keeps slugs and snails out; they won’t cross the barrier. A word of warning: any overhanging leaves that can provide a bridge into the bed will defeat the barrier.

Whiteflies are sometimes a problem in mild-winter areas of the country, as well as in greenhouses nationwide, especially on lettuces, tomatoes, and cucumbers. Whiteflies can be a persistent problem if plants are located against a building or fence, where air circulation is limited. In the garden, Encarsia wasps and other parasitoids usually provide adequate whitefly control. Occasionally, especially in cool weather or in greenhouses, whitefly populations may begin to cause serious plant damage (wilting and slowed growth or flowering). Look under the leaves to determine whether the scalelike, immobile larvae, the young crawling stage, or the pupae are present in large numbers. If so, wash them off with water from your hose. Repeat the washing three days in a row. In addition, try vacuuming up the adults with a handheld vacuum early in the day while the weather is still cool and they are less active. Insecticidal soap sprays can be quite effective as well.

Rabbits and mice can cause problems for gardeners. To keep them out, use fine-weave fencing around the vegetable garden. If gophers or moles are a problem, plant large vegetables such as peppers, tomatoes, and squash in chicken wire baskets in the ground. Make the wire stick up a foot from the ground so the critters can’t reach inside. In severe situations you might have to line whole beds with chicken wire. Gophers usually need to be trapped. Trapping for moles is less successful, but repellents like MoleMed sometimes help. Cats help with all rodent problems but seldom provide adequate control. Small, portable electric fences help keep raccoons, squirrels, and woodchucks out of the garden. Small-diameter wire mesh, bent into boxes and anchored with ground staples, protects seedlings from squirrels and chipmunks.

Deer are a serious problem—they love vegetables. I’ve tried myriad repellents, but they gave only short-term control. In some areas deer cause such severe problems that edible plants can’t be grown without tall electric or nine-foot fences and/or an aggressive dog. The exception is herbs; deer don’t feed on most culinary herbs.

Songbirds, starlings, and crows can be major pests of young seedlings, particularly lettuce, corn, strawberries, and peas. Cover the emerging plants with bird netting and firmly anchor it to the ground so birds can’t get under it and feast.

Pest Controls

Insecticidal soap sprays are effective against many pest insects, including caterpillars, aphids, mites, and whiteflies. They can be purchased, or you can make a soap spray at home. As a rule, I recommend purchasing insecticidal soaps, as they have been carefully formulated to give the most effective control and are less apt to burn your vegetables. If you do make your own, use a mild liquid dishwashing soap; not caustic detergents.

Neem-based pesticide and fungicide products, which are derived from the neem tree (Azadirachta indica), have relatively low toxicity to mammals but are effective against a wide range of insects. Neem products are considered “organic” pesticides by some organizations but not by others. Products containing a derivative of neem—azadirachtin—are effective because azadirachtin is an insect growth regulator that affects the ability of immature stages of insects such as leaf miners, cucumber beetles, and aphids to develop to adulthood. BioNeem and Azatin are commercial pesticides containing azadirachtin. Another neem product, Green Light Fruit, Nut, and Vegetable Spray, contains clarified hydrophobic extract of neem oil and is effective against mites, aphids, and some fungus diseases. Neem products are still fairly new in the United States. Although neem was at first thought to be harmless to beneficial insects, some studies now show that some parasitoid beneficial insects that feed on neem-treated pest insects were unable to survive to adulthood.

Pyrethrum, a botanical insecticide, is toxic to a wide range of insects but has relatively low toxicity to most mammals and breaks down quickly. The active ingredients in pyrethrum are pyrethins derived from chrysanthemum flowers. Do not confuse pyrethrum with pyrethoids, which are much more toxic synthetics that do not biodegrade as quickly. Many pyrethrums have a synergist, piperonyl butoxide (PBO), added to increase the effectiveness. As there is evidence that PBO may affect the human nervous system, try to use pyrethrums without PBO added. Wear gloves, goggles, and a respirator when using pyrethrum.

Diseases

Plant diseases are potentially far more damaging to your vegetables than are most insects. There are two types of diseases: those caused by nutrient deficiencies and those caused by pathogens. Diseases caused by pathogens, such as root rots, are difficult to control once they begin. Therefore, most plant disease control strategies feature prevention rather than control.

Bird and squirrel protection

To keep diseases under control it is very important to plant the “right plant in the right place.” For instance, salad greens in poorly drained soil often develop root rot. Tomatoes planted against a wall are prone to whiteflies and fungal diseases. Check the cultural needs of a plant before placing it in your garden. Proper light, air circulation, temperature, fertilization, and moisture are important factors in disease control.

Finally, whenever possible, choose disease-resistant varieties when a particular pathogen is present or when conditions are optimal for the disease. The entries for individual plants in the Italian Garden Encyclopedia (page 21) give specific cultural and variety information. As a final note, plants infected with disease pathogens should always be discarded, not composted.

Nutritional Deficiencies

For more basic information on plant nutrients, see the soil preparation information given in Appendix A (page 88). As with pathogens, the best way to solve nutritional problems is to prevent them. While there are mineral deficiencies that affect vegetables, most often caused by a pH that is below 6 or above 7.5, the most common nutritional deficiency is a lack of nitrogen. Vegetables need fairly high amounts of nitrogen in the soil to keep growing vigorously. Nitrogen deficiency is especially prevalent in sandy soil or soil low in organic matter. (Both clay and organic matter provide little nitrogen; they do hold on to it, however, thereby keeping it available to the plants’ roots and keeping the nitrogen itself from leaching away.)

The main symptom of nitrogen deficiency is a pale and slightly yellow cast to the foliage, especially the lower, older leaves. For quick-growing crops like baby greens and arugula, by the time the symptoms show up, it’s too late to apply a cure. You might as well pull out the plants and salvage what you can. To prevent the problem from recurring, supplement your beds with a good source of organic nitrogen like blood meal, chicken manure, or fish emulsion. For most vegetables, as they are going to be growing for a long season, correct the nitrogen deficiency by applying fish emulsion according to the directions on the container; reapply it in a month or so. (Usually nitrogen does not stay in the soil for more than four to six weeks, as it leaches out into the ground water.)

While I’ve stressed nitrogen deficiency, the real trick is to reach a good nitrogen balance in your soil; although plants must have nitrogen to grow, too much causes leaf edges to die, promotes succulent new growth savored by aphids, and makes plants prone to cold damage.

Diseases Caused by Pathogens

Anthracnose is a fungus that is primarily a problem in the eastern United States on beans, tomatoes, cucumbers, and melons. Affected plants develop spots on the leaves; furthermore, beans develop sunken black spots on the pods and stems, and melons, cucumbers, and tomatoes develop sunken spots on the fruits. The disease spreads readily in wet weather and overwinters in the soil on debris. Crop rotation, good air circulation, and choosing resistant varieties are the best defense. Neem-based Green Light Fruit, Nut and Vegetable Spray gives some control.

Blights and bacterial diseases include a number of diseases caused by fungi and bacteria that affect vegetables, and their names hint at the damage they do—such as blights, wilts, and leaf spots. As a rule, they are more of a problem in rainy and humid areas. Given the right conditions, they can be a problem in most of North America. Early blight strikes tomatoes when plants are in full production or under stress and causes dark brown spots with rings in them on older leaves, which then turn yellow and die. Potato tubers are also prone to early blight and become covered with corky spots. Warm, moist conditions promote the disease. Late blight causes irregular gray spots on the tops of tomato leaves with white mold on the spots on the underside of the leaves. Leaves eventually turn brown and dry-looking. Fruits develop water-soaked spots that eventually turn corky. Potato tubers develop spots that eventually lead to rot. Cool nights with warm days in wet weather are ideal conditions for the disease. Halo and common blight cause spots on leaves and pods of most types of beans and are most active in wet weather. All these blight-causing fungi and bacteria overwinter on infected plant debris. To prevent infections, avoid overhead watering, clean up plant debris in the fall, rotate crops, and purchase only certified disease-free seed potatoes. Bacterial wilt affects cucumbers, melons, and sometimes squash. The disease is spread by cucumber beetles and causes the plants to wilt, then eventually die. To diagnose the disease, cut a wilted stem and look for milky sap that forms a thread when the tip of a stick touches it and is drawn away. The disease overwinters in cucumber beetles; cutting their population and installing floating row covers over young plants are the best defenses.

Damping off is caused by a parasitic fungus that lives near the soil surface and attacks young plants in their early seedling stage. It causes them to wilt and fall over just where they emerge from the soil. This fungus thrives under dark, humid conditions, so it can often be thwarted by keeping the seedlings in a bright, well-ventilated place in fast-draining soil. In addition, when possible, start seedlings in sterilized soil.

Fusarium wilt is a soil-borne fungus most prevalent in the warm parts of the country. It causes an overall wilting of the plant visible as the leaves from the base of the plant upward yellow and die. The plants most susceptible to different strains of the disease are tomatoes, potatoes, peppers, cucumber, squash, melons, asparagus, basil, and peas. While a serious problem in some areas, this disease can be controlled by planting only resistant varieties. Crop rotation is also helpful.

Mildews are fungal diseases that affect some vegetables—particularly peas, spinach, and squash—under certain conditions. There are two types of mildews: powdery and downy. Powdery mildew appears as a white powdery dust on the surface; downy mildew makes velvety or fuzzy white, yellow, or purple patches on leaves, buds, and tender stems. The poorer the air circulation and more humid the weather, the more apt your plants are to have downy mildew.

Make sure the plants have plenty of sun and are not crowded by other vegetation. If you must use overhead watering, do it in the morning. In some cases, powdery mildew can be washed off the plant. Do so early in the day, so that the plant has time to dry before evening. Powdery mildew is almost always present at the end of the season on squash and pea plants but is not a problem since they are usually through producing.

Lightweight “summer” horticultural oil combined with baking soda has proved effective against powdery mildew on some plants in research at Cornell University. Combine 1 tablespoon of baking soda and 27, teaspoons of summer oil with 1 gallon of water. Spray weekly. Test on a small part of the plant first. Don’t use horticultural oil on very hot days or on plants that are moisture-stressed; after applying the oil, wait at least a month before using any sulfur sprays on the same plant.

A “tea” for combating powdery mildew and possibly other disease-causing fungi can be made by wrapping a gallon of well-aged, manure-based compost in burlap and then steeping it in a 5-gallon bucket of water for about three days, in a warm place. Spray every three to four days, in the evening if possible, until symptoms disappear.

Downy mildew is sometimes a problem on lettuces and spinach, especially in late fall, in cold frames, and under row covers. Select resistant varieties when possible, try to keep irrigation water off the leaves, prevent plants from crowding, dispose of any infected leaves and plants, and, if growing greens in a cold frame, make sure the air circulation is optimal.

Root rots and crown rots are caused by a number of different fungi. The classic symptom of root rot is wilting—even when a plant is well watered. Sometimes one side of the plant will wilt, more often the whole plant wilts. Affected plants are often stunted and yellow as well. The diagnosis is complete when the dead plant is pulled up to reveal rotten, black roots. Crown rot is a fungus that kills plants at the crown, and it is primarily a problem in the Northeast. Root and crown rots are most often caused by poor drainage. There is no cure for root and crown rots once they involve the whole plant. Remove and destroy the plant and correct the drainage . problem.

Verticillium wilt is a soil-borne fungus that can be a problem in most of North America, especially the cooler sections. The symptom of this disease is a sudden wilting of one part of or all of the plant. If you continually lose tomatoes or eggplants, this, or one of the other wilts, could be the problem. There is no cure, so plant resistant species or varieties if this disease is in your soil.

Viruses attack a number of plants. Symptoms are stunted growth and deformed or mottled leaves. The mosaic viruses destroy chlorophyll in the leaves, causing them to become yellow and blotched in a mosaic pattern. There is no cure for viral conditions, so the affected plants must be destroyed. Tomatoes, strawberries, cucumbers, and beans are particularly susceptible. Viral diseases can be transmitted by aphids and leaf hoppers, or by seeds, so seed savers should be extra careful to learn the symptoms in individual plant species. When available, use resistant varieties.