A an executive coach, I recently began working with Gail, who is an executive director of a large and complex nonprofit organization. She is thirty-four years old, much younger than the woman who previously held this leadership position. Gail was thrilled, surprised, and nervous to find herself in a role with so much authority and responsibility. As she was describing her work and personal challenges to me, I looked at her and said, “Do you realize that you hold your breath while you are speaking? It is subtle, but I wonder what your experience is?” Tears welled in her eyes. She described how, when speaking, she felt underlying fear and anxiety most of the time. She was aware that she tended to edit her words before she spoke, and she was also aware of a general lack of trust in herself.

Right then, we began to practice breathing together, counting 1, 2, 3, 4, 5 on the out-breath, and 1, 2, 3 on the in-breath. I asked her to explore a feeling of confidence with each exhale, followed by a sense of curiosity on the inhale. Confidently and completely breathing out. Waiting to see what will happen next. Exploring the experience of not knowing and not controlling. Discovering how the inhale happens without any effort. In the moment, Gail’s anxiety lessened noticeably, and I instructed her to continue this practice every day, as well as whenever she noticed she had stopped breathing. The practice I suggested she explore, during the next seven days, was to begin noticing whenever she was holding herself back, to just notice what was happening, with her thinking, with her body, with her breath.

This led to a discussion of the way in which she experienced her work and life as having one foot on the gas and the other foot on the brake. Whenever she would feel confidence (foot on the gas), she would then be filled with anxiety, self-doubt, and the fear of making a mistake or being misunderstood (foot on the brake). She would have good ideas but then hold back. This limited her ability to be completely present and to communicate clearly, and this ultimately limited her effectiveness. I pointed out that this caution, this tightening, limited her chances of failing but also of experiencing success and joy.

What was so touching in our interchange is that she realized that something as simple as breathing more fully as she spoke greatly enhanced her presence; it improved her own sense of power and effectiveness in her work and relationships. We talked about the importance of feeling comfortable and being confident when you don’t know what will happen. In this case, balance and effectiveness don’t mean finding a middle ground. They mean: When you are confident, be fully confident. When you are saying no or feeling cautious, say no or be fully cautious. When it is time to go or to act, don’t put your foot on the brake, and when it’s time to stop, don’t keep pressing the gas pedal.

This insight about balance and effectiveness opened up realms of new possibilities for Gail. She found the courage and the skills she needed to have some difficult conversations with her boss regarding how her boss’s rough and judgmental communication style was negatively impacting the organization’s effectiveness. Her personal life began to shift as she expressed herself more openly and clearly to her partner. And her relationship with her parents, which had always been strained, transformed as she began to be much more confident in herself and more curious and interested in her parents’ perspective and experience. As we worked together over several months, Gail became a much more responsive and effective leader and person.

Not long ago, I was in Berkeley for a coaching meeting with Kaz Tanahashi, one of my clients. I don’t usually mention my clients by name, but at social events, Kaz introduces me as his coach, and he gave me permission to use his name here. Kaz is a world-renowned calligrapher, writer, and translator. He has written or translated more than a dozen books and is currently in the midst of several book projects. At age seventy-nine he travels around the world speaking on environmentalism and peace and teaching calligraphy and Zen. When I mentioned to him that I was in the middle of writing a book focused on effectiveness, he looked at me and asked, “Are you effective?”

For a second I was taken aback, but of course, what a great question! It asks not only whether I am offering a useful, practical definition of effectiveness, but also if I am myself effective in my own life? Will I be an effective teacher of effectiveness.

Like most people, sometimes I feel extremely effective, and yet more often I feel I could or should be even more effective. Sometimes I feel effective in just one or two parts of my life — perhaps my work is progressing nicely — while other parts of my life may feel stale or lacking. In time, inevitably, my sense of my own effectiveness will shift, and what once worked may no longer be successful, and places where I’ve been frustrated or challenged may resolve into wonderful blessings and joy. Each situation, relationship, and day is different.

There is a Zen story from the seventh century in China, part of a collection that has been passed down through the centuries. In the story, a student approaches his old and sick teacher, who is near the end of his days. The student asks, “What is the teaching of an entire lifetime?” Sometimes this question is translated as, “What is the teaching of a thousand lifetimes?”

The teacher answers, “An appropriate response.”

An appropriate response — knowing when to speak or to be silent, to say yes or to say no, to stay or to leave. Knowing when to pick it up and when to put it down, when to move toward a person or situation and when to walk away. Knowing the right thing to do in any given situation — this is the definition, the key, to effectiveness. My former publishing company, Brush Dance, once published a greeting card that said, “Wisdom is knowing what to do next.” Management guru Peter Drucker defined effectiveness in very similar terms: getting the right things done.

How do you respond in a quiet, intimate moment and in the midst of chaos? How do you respond to a child crying in the street and to the cries of the world? How do you show up and act, or react, in each situation? This is the work of a lifetime. An appropriate response means to express yourself in a way that is completely in tune with yourself, with the particular situation, and with life. An appropriate response is not a moral judgment. What we do may include a sense of what’s right and wrong, good and bad, but it is a much wider, deeper, and more inclusive understanding than the quick and partial judgments to which our minds often cling.

In Chinese, the word appropriate contains three characters, which can be translated as “meet,” “each,” and “teach.” This implies that our task is to respond in a way that meets each situation, each person, each of our own emotions. By doing this, there is some teaching, some learning, some wisdom that happens. The Chinese character ichi, translated as “each,” can also mean “oneness.” This points toward a further understanding: sometimes we are learning, sometimes we are teaching, and most of the time we are both learning and teaching. It also implies a level of inclusiveness. Zen sometimes describes this inclusiveness, this oneness, as “not one, not two.”

My friend Pamela Weiss, who named her leadership consulting company An Appropriate Response, tells the story of a time she heard a student ask the Zen teacher Kobun Chino about his work with the dying. A young woman said to Kobun, “I’ve heard you often go to the bedsides of dying people. When you go to visit, how do you help them?” Hearing this question, he closed his eyes, tilted his head, and responded, “Help them? I don’t help them. I meet them.” Then he paused several long minutes, looked at the woman, and said, “I think, really, they help me.”

Then again, there’s the challenge. How do we know what an appropriate action is? Defining effectiveness is much easier than knowing how to be effective in any particular moment. This entire book is devoted to helping you identify and practice right action. However, we can start by heeding the advice of the Zen teacher Dogen, who instructs his students to “take the backward step.”

Backward, as Dogen uses it, means many things, but he uses it first of all as a paradoxical way to wake us up, to shake us out of the habit of blindly pushing forward (or blindly running away) whenever we encounter difficulties. Instead, in order to move forward, step back. Look, see, explore, understand. Notice confusion itself and step back in order to see it better. Step back, even, from all your ideas of who you think you are.

How? As was the case for Gail, this may mean remembering to breathe or regaining your inner composure and awareness. In general, practicing and increasing inner awareness is how we become more fully ourselves, more fully authentic human beings. Stepping backward in this way allows us to embrace and revive our natural wisdom and freedom, our True Nature (as it is often referred to in the Zen tradition).

From this place, we can begin to solve our problems. We can identify the limits of our knowledge and the impacts of our choices. This is where the dualities and oppositions of paradox are helpful, for they provide a useful framework for understanding the full and complex nature of our problems, and thus for finding solutions. Part 2 looks at these paradoxes in detail.

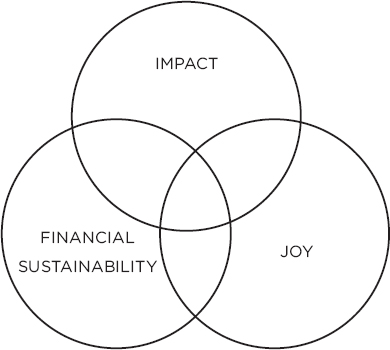

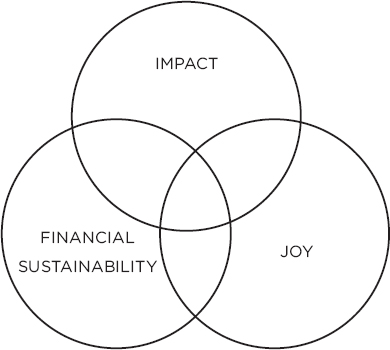

However, another useful tool that I use when it comes to decision making is to envision three circles. This creates a very useful and effective “decision-making matrix” that helps me balance the essential aspects of my life and identify the right actions to take. Using three circles also tends to avoid the either-or dilemmas that dualities often embody. Interestingly, many complex situations condense naturally and logically into three arenas. Perhaps three is a magic number. One that appears throughout this book is embodied by the three bricklayers: that is, self, others or family, and the world or spirituality.

Here is how this works in action. Whenever I am faced with a career question, or when I’m deciding whether or not to pursue or accept a new job, I envision a slightly different set of three circles: impact, joy, and financial sustainability (though you can redefine these areas to fit your situation or dilemma). The three questions I ask and answer are: 1.) Does my work have positive impact? 2.) Does my work bring joy to me and to others? 3.) Does my work provide financial sustainability?

These three categories can be seen as being in opposition to one another — more joy may lead to less impact and less money. A job that earns more money may lead to less joy. Ideally, I want a situation that elicits a positive answer to all three questions. I don’t need each aspect to be literally equal. I’m not expecting perfect balance. At times I’m willing to sacrifice money and joy for impact. Often for me, however, impact is the most important. It’s why I work. And yet, I also need to pay the bills, and without joy, what impact can I have?

First, just applying these criteria shifts my focus away from fear, worry, and survival. Asking these questions shifts my attention from my day-to-day concerns to something larger: How do I want to show up? How do I want to live? Certainly, the answers I get may be vague, unsure. I may have genuine doubts and fears. Life is unstable and changeable, whether we’re considering the economy, our relationships, or even our own feelings and dreams. There may be aspects to our situation that we can’t, for the moment, change. And yet, where do we choose to put our attention? How do we find balance where there is imbalance?

Impact may mean helping one person, a team, a company, a community, or a nation. I remember once being upset when only six people registered for a workshop I was leading. I was hoping for at least ten people. When I mentioned this to my son, his response was, “Dad, even if you can positively impact the life of one person, isn’t that enough?” I appreciated the sentiment, but to be honest, in the moment I wasn’t sure. However, the workshop with six people turned out to be wonderful. A small community formed out of it and went on to meet several additional times over the course of the year.

The question of impact asks us to consider what role we want to play in our community and how our work serves others. By evaluating the type of impact a new job promises, we can try to assess: Is it the impact we want to make? Does it fit our talents and skills? Do we desire more impact than it offers? Will we be frustrated and discontent with this level and type of impact? Then, on balance, is the potential impact enough given our assessment of the other two circles?

Answering these questions prepares us to work effectively in the position we’re taking. Yet this is also a question to pose regarding our current job. Particularly if you feel stuck in a position that, for financial or other reasons, you can’t leave, ask yourself: How am I currently impacting others? How can I increase this impact in more satisfying ways? Sometimes, our current lives possess more potential than we realize. There are many ways, small and large, to positively impact others in our work. Sometimes our impact may not be seen or recognized outside of our company or department, or even outside of a particular relationship, and yet just listening, paying attention to one other person, can make a large difference. Have we become attached to making only one kind of impact? Maybe we want to run a company one day, but in the meantime, are we maximizing our potential as helpful employees, colleagues, mentors, managers, and so on? When considering impact, we should look at those we work with and those we serve, in addition to the good we hope our actions create.

We usually don’t think of joy as being important in our work. Why is that? Most of us spend more time at work than any other place in our lives. Why not look for ways to bring a sense of lightness and enjoyment to what we do as employees or employers?

This criterion of joy also raises the question, What do you really like doing? What is nourishing, challenging, interesting to you? Is what you are currently doing aligned with the answers to these questions? What steps might you take to bring your work more in line with a sense of joy?

Thankfully, joy is the circle that is most within our control. No job, no experience, is perpetually, continually, purely joyful; pain, difficulty, and impermanence will arise whatever our circumstances. Even a dream job will have its nightmare moments. So this question challenges us to find the joy within any and every situation. A certain type of joy exists in any job well done, and that satisfaction in accomplishment is often directly related to our self-confidence. Paying attention to and cultivating self-confidence can also be a way to cultivate more joy.

Money and issues of financial stability are complex and personal. We all need to pay the bills, to earn enough income to meet our basic needs. This is no small matter. Indeed, sometimes this arena trumps all others: to earn what we need, to feed and house ourselves and our families, we have no choice but to take (or stay in) certain jobs. Considerations of joy and impact may seem like unaffordable luxuries in comparison.

As I’ve made clear above, however, the point of this three-circle exercise is to recognize imbalance and to identify actions to correct it. The first question within this criterion is simply, Does this job provide enough to meet my financial needs? If not, then joy and impact will certainly be lessened. However, that doesn’t mean they need be nonexistent. In this case, our task is to create as much joy and impact as possible until we get our financial house in order.

To do this, we can ask another, larger question: What is financial sustainability for me? What is “enough”? If we are living beyond our means, then one answer is to adjust our lifestyle to fit our income. Would this be a better, more satisfying choice than taking a job solely because of its salary? Conversely, people sometimes make income-based work decisions with the belief that earning more money brings more joy and impact. Other times, people seek money as a response to fear or a desire for power. What purposes does money serve for you? Even if we are not in a position to change jobs, this is a question that deserves close examination.

The book is organized so that it follows a clear progression, but ultimately in this work, there is no first, last, or necessarily next step. This book doesn’t describe a linear path to an endpoint. We each begin at whatever point we are at in this moment, and then we create our own unique path by walking it. Don’t fall into the trap of thinking that you must finish one chapter or step before moving on to the next one, or that once you’ve worked through a certain paradox or step you will never need to return to it again. Rather, as with a tightrope walker, progress is measured by how well balanced we become, by how long and through what difficulties we are able to stay on the rope without falling, not in how far we travel.

Thus, this work inevitably entails a certain amount of experimenting and exploration, of trial and error. In my experience, some people are more comfortable with this than others, and nearly everyone learns more quickly and thoroughly when goals, objectives, and practices are stated up front. To help with this, I’ve designed Action Plan boxes that appear near the beginning of each of the five chapters in part 2. These Action Plan boxes list the hands-on practices and actions contained within each chapter, and each can be used like a discrete activity-based program for tackling that chapter’s issues. Put all five of them together, and you have a program for the entire book. They condense the central teachings into what I hope you’ll find to be a pragmatic set of succinct, cross-referenced instructions for helping to build a more fulfilling and meaningful life.

Some people also find visual analogies extremely helpful. You might explore thinking of this process like a circle, with each of the five paradoxes or truths in part 2 as points around the circumference of that circle. Further, each point in the circle is directly connected to all the others (see figure below). To move between and among them, there is no forward or backward, no beginning or end. Each pair of connecting points makes a necessary spoke in the wheel that is your life; in all likelihood, you’ll traverse each spoke eventually. And just as there is no finish line, there is no stasis. In this work, we continually move between these points in whatever order and way is necessary to stay balanced, whole, inspired, and fulfilled.

Those who like order and clear instructions can follow along chapter by chapter as though this were a step-by-step program. Those who chafe at rules and prefer to follow their intuition can pick and choose and jump around at will; the Action Plan boxes also make for handy indexes to quickly find particular practices and teaching stories (which will be described further in chapter 3).

Either way, and however you explore the material, notice what brings you alive and what elicits resistance. Pursue each of these feelings and notice what insights they may lead to. What do you learn? What can you unlearn? Be relaxed, curious, and alert; be confident and question everything; seek your own internal wisdom; and steadily hone the essential skill of knowing yourself and forgetting yourself.