2

The current psychology of leadership

Issues of context and contingency, transaction and transformation

As we saw in the previous chapter, the “great man” approach to leadership continues to wield considerable influence in the world at large. However, within the confines of the academic world, its heyday is long past. It has long been accepted that leaders do not triumph simply through the strength of their own will and that the key to successful leadership cannot be found by restricting one’s gaze to the heroic leader. As a result, researchers’ analytic gaze has been broadened to incorporate other determinants of leadership. This has occurred in two broad overlapping waves: first through a focus on the importance of situational factors, then through a focus on followers and on their relationship with leaders.

Inevitably, by broadening the range of considerations that affect leadership performance, one dilutes the importance of any single factor. To argue that context and audience play some part in determining who succeeds as a leader is to place constraints on the role of the leader in shaping the world and those within it. Arguably, this process has been taken too far. The figure of the leader as superman may rightly have been usurped, but is it right to replace it with a picture in which the leader is, at worst, a mere cipher, and, at best, little more than a book-keeper? The danger is that we will lose those aspects of leadership that make it so fascinating and so important in the first place: the creativity of leaders, their ability to shape our imaginations and guide us towards new goals, their role in producing social change—and, occasionally, social progress.

In response to this, recent years have seen a rekindling of interest in charisma and in the transformational quality of leadership. This is clearly an important corrective. It is one thing to say that the impact of leaders relates to the situations they find themselves in and to those they seek to lead. It is quite another to say that leaders are prisoners, shackled to context and to followers. But does the new-found emphasis on transformational leadership take us beyond a simple opposition between the power of the leader and constraints in that leader’s world (such that, for instance, the more agency that a leader has, the less agency is accorded to followers and the more agency that these followers have, the less is accorded to the leader), or does it simply rebalance the scales back on the leader’s side?

In this chapter, we outline these various threads that constitute current academic analyses of the psychology of leadership. We suggest that this work provides many building blocks for understanding the phenomena that interest us: the importance of context, the role played by followers, the function of power, the dynamics of transformation. These are blocks that will be crucial to us in subsequent chapters. To use a somewhat different analogy, the work that we will review here alerts us to many of the key ingredients that we require. However, we also suggest that there is still work to be done in determining how they should be combined together in order to constitute the recipe for successful leadership.

The importance of context and contingency

The situational approach

If character does not make the leader, perhaps context does. If leaders are not those who are made of “the right stuff” perhaps they are simply those who are in the right place at the right time. There are stronger and weaker variants of this situational approach. In its most extreme form the idea is that character hasno role to play at all and that just about anybody, when put into the place of a leader, could exercise the leadership function.

This approach was at the peak of its popularity in the 1960s and 1970s. Championed by role theorists like Philip Zimbardo, it was exemplified in the famous Stanford Prison Experiment (SPE; Haney, Banks, & Zimbardo, 1973). In this, college students were assigned by the experimenters to roles as Guards and Prisoners within a simulated prison that had been built in the basement of the Stanford psychology department. As the study progressed, the Guards took on their roles with considerable enthusiasm. Indeed, the study had to be stopped after 6 days, such was the brutality of the Guards and the suffering of the Prisoners. This brutality was epitomized by the actions of a Guard leader who styled himself as “John Wayne” and who seemed to take special pleasure in humiliating the Prisoners. According to the researchers, the reason why he and his fellow Guards took on such roles was that this was a “natural consequence of being in the uniform of a Guard and asserting the power inherent in that role” (Haney et al., 1973, p. 12). This extreme form of situational determinism suggests that it is context that determines both the leader and the way that he or she behaves—and that’s all there is to it.

In practice, few psychologists ever adhered to such an extreme position and even fewer adhere to it today. This is because, conceptually, it effectively writes psychology and human agency out of the picture (see Reicher & Haslam, 2006a). Empirically, though, there are always differences in the way that people respond to even the most extreme environments. This is as true of the SPE as of any other setting. Thus while “John Wayne” may have been a brutal authority figure, other Guards were either firm but fair or else actively sided with the Prisoners (Zimbardo, 2004). Mainly, then, situationism is a rhetorical stance adopted by those scholars (in particular, historians and sociologists) who object to highly psychologized approaches to leadership that seek to understand and explain large-scale social movements and histories solely in terms of the activities (or personalities) of a few key players. Their adherence to situational models is typically framed as a frustrated reaction against historical and other narratives that stubbornly refuse to examine the ground against which the figure of the leader is defined and from which that leader emerges. Their frustration is understandable, but the position they adopt is often as little use to them as the position they reject. For instance, in his 1992 book Ordinary Men, which seeks to understand the actions of the Nazi killing squads that operated with such devastating effect in occupied Poland, the historian Christopher Browning observes considerable variation in the responses of squad members to their hellish situation even as he explicitly cites Zimbardo’s situational account to explain their hellish acts.

It is therefore far more common for researchers to adopt a position in which the situation moderates but does not entirely obliterate the significance of character. Some argue that, although not everyone could be a leader, in any given situation a large number of people would have the requisite skills and therefore would serve equally well. Often referred to as the times theory, such ideas are reflected in the lay belief that “cometh the hour, cometh the man.” Stated more formally, the theory holds that:

At a particular time, a group of people has certain needs and requires the service of an individual to assist it in meeting its needs. Which individual comes to play the role of leader in meeting these needs is essentially determined by chance, that is, a given person happens to be at the critical place at the critical time. The particular needs of the group may, of course, be met best at a given time by an individual who possesses particular qualities. This does not mean that this particular individual’s peculiar qualities would thrust him into a position of leadership in any other situation. It means only that the unique needs of the group are met by the unique needs of the individual.

(Cooper & McGaugh, 1963, p. 247)

From the historian’s perspective, such an approach invites researchers to interpret events not in terms of the activities and psychology of a select few leaders but in terms of the broad social and structural conditions that prevail at a particular point in time. Such a view contends, for example, that it is a mistake to try to understand events of World War II in terms of the psychologies of Hitler, Churchill, Stalin, and Roosevelt in the manner attempted by many popular historical accounts. Instead, it suggests that one has to focus on the conditions in Germany, the British Empire, the Soviet Union, and the United States that brought these respective leaders to the fore. Had it not been Churchill at the helm of a dwindling but resilient empire, it would have been someone else like him, and if it had not been Hitler at the head of a brutal Fascist state, it would have been someone else like him, and so on. What is more, this analysis suggests that, whoever had been leader, history would not have been very different. Indeed, at this macro-social scale, the danger is that the individual is removed entirely from the scene.

From the psychologist’s perspective, however, less attention rests on the fact that individual leaders like Churchill and Hitler may not have been unique and more on the claim that, had they not emerged as leaders, someone like them would. What does this phrase actually mean? What are the common characteristics of those who might have replaced Churchill or Hitler? And what is it about a particular situation that calls forth leaders with particular characteristics? In other words, at a more micro-social scale, the times theory suggests an interaction between leader and context whereby different types of people make good leaders in different types of situation. In the psychological literature, this type of position is known as the contingency approach.

The contingency approach

The idea that leadership is the product of a “perfect match” between the individual and the circumstances of the group he or she leads can be traced back to the work of researchers like Cecil Gibb in the 1950s (e.g., Gibb, 1958). Over the past 50 years it has manifested itself in a multitude of specific theories and is still ascendant today. Accordingly, in an influential review, Fred Fiedler and Robert House (1994) observed that, of the dozen or so theories of leadership with widespread currency, most adopted a contingency framework of this form. But equally, when leaders themselves talk about the roots of their success, they generally produce contingency formulations. For example, when James Sarros and Oleh Butchatsky (1996) asked prominent Australians the age-old question of whether leaders are “born or made,” almost all rejected the opposition in favor of an interaction. This is seen in embryonic form in the response of Don Argus, Managing Director of the National Australia Bank:

I don’t think people are born to be leaders, I think that’s rubbish. I think it’s a developmental thing and a matter of opportunity … you can’t just define it as one thing.

(cited in Sarros & Butchatsky, 1996, p. 214)

It is apparent too in the views of the senior trade unionist, Anna Booth:

I don’t think you necessarily become a productive leader because you’ve got leadership qualities. I think it’s certain circumstances … Some people with the leadership qualities may never be presented with the right circumstance, so I think that life is somewhat a case of luck.

(cited in Sarros & Butchatsky, 1996, p. 212)

Tony Berg, CEO of the construction materials company Boral, fleshes this formulation out a bit, but his analysis is basically the same:

I have to say there’s a lot of circumstance in the way things turn out. There’s actually a theory that it’s all random. I don’t think it’s totally random, but I think there’s a lot of circumstance. You have to be in the right place at the right time, which to a certain extent you manage…. I’ve sought out leadership, so to a certain extent it’s in my make-up. There are others who will shy away from high-profile positions. They’re the analysts, or the thinkers, who don’t particularly want to be leaders and so don’t push themselves, and retire away from that.

(cited in Sarros & Butchatsky, 1996, p. 221)

In all these responses, then, we see a hybrid of situational and personality accounts. These meld an awareness of the role of luck and circumstance with an emphasis on leadership qualities and character. This convergence between academic theory and expert opinion makes for a formidable combination. More accurately, we should refer to academic theories since there is a wide variety of contingency approaches, each of which packages its ideas in a different way (with different theorists arguing stridently for the superiority of one formulation over another). In practice, though, all have a very similar structure. In essence, each has three components: first, some method for uncovering the character of the would-be leader; second, some taxonomy (i.e., a system of classification) that describes the leadership context in terms of theoretically relevant features; and third, some specification of the optimal fit between these two elements.

Although it would be possible to dissect each of these theories in a similar way, in order to explore the precise mechanics of contingency theories it is useful to focus on Fiedler’s (1964, 1978) least preferred co-worker theory, as this is probably the theory that has been exposed to most empirical scrutiny in the past 40 or so years. Like other contingency models, this considers successful leadership to be a product of the fit between the characteristics of leaders and features of the situation they confront.

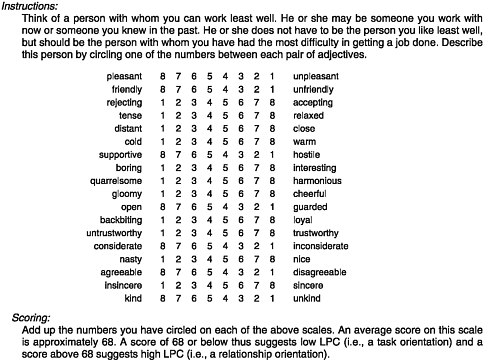

In this case the characteristics of the individual leader are established by asking him or her to use a series of rating scales to describe the person they would least like to work with—their so-called “least preferred co-worker” (LPC). Although Fiedler does not couch his analysis in these terms, those who generally describe this co-worker relatively negatively (low-LPC) can be considered to be more task-oriented (or “hard”), while those who describe this co-worker more positively (high-LPC) can be considered to be more relationship-oriented (or “soft”). A sample LPC inventory is presented in Figure 2.1.

Moving on to the features of the situation, LPC theory focuses on three factors: (1) the quality of relations between the leader and other group members (good or bad); (2) the degree to which the leader has power (high or low); and (3) the extent to which the group task is structured (high or low).

Figure 2.1 A typical LPC inventory (after Fiedler, 1964).

Lastly, the theory proposes that the fit between leaders and situations works in a particular way. On the one hand, low-LPC task-oriented leaders are predicted to be most effective when features of the situation are all favorable (i.e., when relations are good, the task is structured, and the leader has power) or all unfavorable. On the other, high-LPC relationship-oriented leaders are expected to be more effective in situations of intermediate favorableness. These predictions are summarized in Table 2.1.

There are a number of points that one can make that are specific to Fiedler’s LPC version of contingency theory. In the first instance, the LPC scale seems a rather strange way of identifying leadership characteristics and it is far from clear what it is actually measuring (Landy, 1989). It could, for example, be a measure of people’s generosity of spirit, their sensitivity to norms of social desirability, or their breadth of experience. As we have suggested, one possibility is that to be low-LPC means that one is “task-oriented”, while being high-LPC means that one is “relationship-oriented.” However, the constructs here are so rubbery that recent research suggests that these associations may, in fact, be reversed (Hare, Hare, & Blumberg, 1998).

A second problem has to do with the evidence base for the theory. While Fiedler and his colleagues have produced data that are consistent with the model and remain staunch defenders of it, many other researchers have been unable to reproduce Fiedler’s findings (especially in more dynamic contexts)

and are far less enthusiastic. As with the standard personality approaches that we reviewed in Chapter 1, a fair conclusion is that support for the theory is mixed and highly variable. The same could be said of contingency models in general.

This lack of a strong empirical foundation is one of several more fundamental issues that unite Fiedler’s work with other contingency approaches to leadership. Before outlining these, a critical caveat is in order. At one level, such approaches are undoubtedly correct and represent a critical step forward in our understanding of leadership. After all, as Kurt Lewin observed in his seminal field theory (Lewin, 1952; see also Gold, 1999), all behavior is the product of an interaction between the person and his or her environment. Therefore any theory, including leadership theories, must examine both person (leader) and situation. Our concern, then, is not with the notion of contingency in general (which we fully endorse) but rather with the specific sense it is given in the leadership literature. There are two fundamental problems here. The first is that each term in the interaction is conceptualized as a fixed entity that is separate from the other. The second is that only one of these terms, the person, is the subject of a properly psychological analysis. The consequence is that contingency theories of leadership fail properly to grasp the psychological dynamics of interactionism (see also Reynolds et al., 2010).

In the first place, as we suggested in Chapter 1, leaders, like everyone else, do not have a set psychology. The idea that a person will display the same characteristics over time and across a broad range of contexts is implausible, as is the idea that this could ever be a recipe for leadership success. Thus the person who is task-oriented in one context will be relationship-oriented in another, and the attempt to limit considerations of a person’s leadership-relevant qualities to a single one-shot bi-polar dimension seems highly contrived. This point was captured rather more poetically by Shakespeare’s Henry V as he rallied his troops for battle (Grint, 2005)1:

In peace there’s nothing so becomes a man

As modest stillness and humility:

But when the blast of war blows in our ears,

Then imitate the action of the tiger;

Stiffen the sinews, summon up the blood,

Disguise fair nature with hard-favor’d rage.

(Henry V, Act III, Scene i)

Henry’s point (or rather Shakespeare’s) is that, like all leaders (and their followers), he has to tailor his leadership style to the circumstances at hand. Leaders’ self-evident ability to do this undermines the claim that their behavior is the reflection of an immutable personality.

But equally, situations are neither fixed nor beyond the realm of psychology. After all, the major contexts in which leaders operate are social contexts. The general aim of leaders is either to move people or else to move humanly made products (laws, institutions, and so on). And even when their aim is to shift the physical landscape, the means by which they do this is by moving people (to re-invoke Brecht from the previous chapter, people raised the rocks that built Thebes, Rome, and everywhere else). In other words, the context confronting any leader is always partly constituted by followers who are self-evidently subjects for psychological analysis and who, being people, are themselves as variable as leaders. In the case of leadership, then, any interactionism that ignores the psychology of followers is a deficient interactionism.

The importance of followers

Luckily, we are not alone in insisting that to understand leadership one must also understand followership. And where there are multiple theorists it is almost inevitable that there will be multiple theories. In fact there are two broad traditions in the study of followers. One focuses on how leaders are dependent on the perceptions of followers. Another focuses on the importance of interactions—or rather transactions—between leaders and followers. To complicate things further, this second tradition itself has two broad strands. One looks at economic relations between leaders and followers, the other looks at power relations between the two parties. So let us consider these various approaches in turn.

The perceptual approach

An embryonic form of the perceptual approach was spelled out in the work of Max Weber in the 1920s that we discussed in the previous chapter. Weber, you may recall, considered a leader’s effectiveness to be determined in no small part by followers’ perceptions of him or her as an appropriate and effective leader. In order to be a great leader, it is not enough to “do great things”—one’s greatness also has to be appreciated by others and one’s actions have to be recognized by them as constituting leadership. For this reason, we noted that Weber saw charisma—a person’s perceived capacity to inspire devotion and enthusiasm—as something that followers confer on leaders rather than something that leaders possess or exhibit in the abstract.

Much more recently, Robert Lord and his colleagues have built on these insights and gone so far as to define leadership as “the process of being perceived by others as a leader.” This definition is central to their leadership categorization theory, which argues that in order to be successful, leaders need to behave in ways that conform to followers’ fixed, pre-formed leadership stereotypes2 (e.g., Lord, Foti, & Phillips, 1982; Lord & Maher, 1990, 1991). These stereotypes differ in their specificity and can be arranged in a hierarchy in which those at the top are abstract and broad, and those at the bottom are more concrete and prescriptive. They are also believed to provide perceivers with a set of expectations regarding a leader’s appropriate traits and behaviors.

At the highest level of the hierarchy, all leaders, whatever their field, are expected to share a number of common attributes (such as intelligence, fairness, and outgoingness; along the lines of Table 1.1). However, at the bottom of the hierarchy Lord and colleagues identify eleven so-called “basic” categories. For each category a person’s possession of particular attributes predicts successful leadership in a given domain (e.g., sport) and differentiates between successful leadership in different domains (e.g., business and politics). In the researchers’ words:

Leadership is a cognitive knowledge structure held in the memory of perceivers…. Essentially, perceivers use degree of match to this ready-made structure to form leadership perceptions. For example, in a business context someone who is well-dressed, honest, outgoing and intelligent would be seen as a leader. Whereas in politics someone seen as wanting peace, having strong convictions, being charismatic, and a good administrator, would be labelled as a leader.

(Lord & Maher, 1990, p. 132)

Moreover, because these leadership stereotypes are seen to be fixed determinants of leader effectiveness, it is suggested that if two basic categories are characterized by a low level of overlap in their content, then leaders who are effective in one domain (because their behavior is consistent with the stereotype for that domain) will find it difficult to be effective in the other. It is suggested that this accounts for the oft-noted difficulty that popular leaders in one arena (e.g., sport) have in gaining acceptance in another (e.g., politics). This analysis is also used to account for the observed context-specificity of appropriate leadership behavior alluded to by contingency theorists like Fiedler.

Lord’s work has made an important contribution to the leadership literature by re-emphasizing the long-neglected role that followers’ perceptions and expectations play in moderating the effects of leader behavior. As did Weber, it recognizes that leadership is as much “in the eye of the beholder” as it is in the actions of the beheld (see also Nye & Simonetta, 1996). What is more, Lord’s approach recognizes the role that social categories and social categorization play in this process. This is a thread that we will pick up on in the next chapter. For now, though, the important point to note about this line of research is that it shows that leadership is a process in which multiple parties are engaged and that these parties’ perceptions of each other are very important.

Despite these strengths, however, this approach suffers from the basic problem that we have already encountered on several occasions in this chapter— that of inflexibility. Where contingency models locate this inflexibility in the fixed character of the leaders, leadership categorization theory locates inflexibility in the fixed stereotypes of followers. Yet in both cases the clear implication is that, in a given situation (or rather, a given domain of leadership in Lord’s case) a given type of leader will succeed. But this is at odds with on-the-ground realities where, however much one tries to pin things down, variety is always the order of the day. In a domain like politics, for instance, it is certainly true that leaders sometimes succeed because they are seen to be peace-loving and good at administration (in ways suggested by Lord & Maher, 1990), but history provides plenty of examples of followers who responded enthusiastically to belligerent leaders who refused to do things by the book.

This point is illustrated in the response of Steve Biko, one of the founders of South Africa’s Black People’s Convention, when asked in 1977 (shortly before his death in detention) if he was going to lead his followers down a path of conflict or one of non-violence:

It is only, I think when black people are so dedicated and united in their cause that we can effect the greatest results. And whether this is going to be through the form of conflict or not will be dictated by the future. I don’t believe for a moment we are going willingly to drop our belief in the non-violent stance—as of now. But I can’t predict what will happen in the future, inasmuch as I can’t predict what the enemy is going to do in the future.

(Biko, 1978/1988, p. 168)

Biko’s point is that neither the form that his leadership will need to take nor the form that his followers will expect it to take can be pinned down in advance of an unfolding reality. In short, both terms in the leader–follower relationship are flexible and both evolve as a function of developing dynamics between groups (Pittinsky, 2009; Platow, Reicher, & Haslam, 2009).

The transactional approach

In many ways, transactional approaches to leadership would seem a promising way of meeting our concerns about flexibility. Whereas both contingency and perceptual approaches can appear to involve a rather mechanical and formulaic matching process—either of leader to situation or of leader to follower stereotypes—transactionalism is more two-sided. It is not about leaders fitting followers or followers fitting leaders. It is about the quality of relations between the two.

This way of thinking about leadership can be traced to the pioneering work of Edwin Hollander from the City University of New York (e.g., 1964, 1985, 1993, 1995). Hollander was one of the first people in modern psychology to appreciate the importance of followership and to understand that followers, far from being passive consumers of leadership, have to be enjoined to become active participants in leadership projects (see also Bennis, 2000; Riggio, Chaleff, & Lipman-Blumen, 2008). Leaders cannot simply barge into a group and expect its members to embrace them and their plans immediately. Instead, Hollander argued, they must first build up a support base and win the respect of followers.

In his early work, Hollander suggested that effective leadership involved a phased process. First, leaders must be seen to advance the group interest in conventional ways. This encourages followers to anoint the leader. Importantly too, it also builds up a line of psychological credit—what Hollander called idiosyncrasy credit—which then allows the leader to challenge received wisdom and take the group in new directions (e.g., see Hollander & Julian, 1970). The metaphor here is that of the bank: the leader is allowed to use the group credit card to do new things once he or she has put enough into the group account.

More generally, Hollander’s work supports the notion that the leader– follower relationship is a social exchange—a matter of give and take in which each party has to provide something to the other before it can receive anything back. Although there are multiple variants of exchange approaches to leadership, all share the same core body of assumptions. In particular, they suggest that effective leadership flows from a maximization of the mutual benefits that leaders and followers provide each other. In effect, then, leadership is seen as the outcome of cost–benefit analyses in which all parties engage: leaders invest energy in the group and, conversely, followers do their leaders’ bidding because, and to the extent that, both parties perceive their transactions to be satisfactory. In short, this is a case of “you scratch my back and I’ll scratch yours” in which leaders and followers cooperate with each other because they see that there is “something in this for me.”

One of the most influential theories of this form is equity theory. Originally formulated by John Stacey Adams (e.g., 1965), this asserts that when a leadership outcome or process is perceived to be inequitable, this creates a state of psychological tension (a disequilibrium) that those who are party to the process are motivated to reduce (see also Walster, Walster, & Berscheid, 1978). This motivation varies as a function of the size of the perceived inequity, so that the larger it is the more the individual leader or follower is motivated to reduce it. The theory also predicts that motivation will vary in response to inequity that is both positive (over-reward inequity, where rewards outweigh costs) and negative (under-reward inequity, where costs outweigh rewards). This means, for example, that a leader who is overpaid should be motivated to work harder to restore equity, but that a leader who is underpaid should want to work less in order to achieve the same equilibrium.

This way of thinking is intuitively appealing, not least because the language of economic exchange is something with which we are all familiar. Nevertheless, like exchange approaches in general, equity theory has a number of serious limitations.3 A fundamental problem is that the concepts of “cost” and“benefit” that are central to the theory are endlessly elastic. As the Dutch researcher Jan Bruins and his colleagues have observed, this means that, ultimately, any behavior can be explained in terms of cost–benefit analysis (Bruins, Ng, & Platow, 1995). For example, if a person’s behavior appears inconsistent with economic principles because they work harder after being refused a pay rise, it can be argued either that they are trying to restore equity by ensuring that they get a pay rise in the future or that they are masochists for whom being treated badly is a valued reward.

This raises the question of whether leadership can be explained in exchange terms or whether leadership serves to explain the terms of economic exchange. For much of what leaders do is to help define what counts as a cost and what counts as a benefit. In particular, great leaders like Martin Luther King and Nelson Mandela show us what to value—peace, justice, loving one’s neighbor, and even reconciliation with one’s oppressor’s—and not only how to obtain what we valued before—influence, power and resources that had previously been denied.

This is a critical issue to which we will return. First, though, there is another, perhaps more basic, issue to consider. The economic view treats both parties to an exchange as equals, seeing both as have something to give and something to take. But is this really the case in relations between leaders and followers? Don’t leaders have more ability to reward than others—and also more ability to punish? Indeed, isn’t their leadership a function of this ability to reward and punish followers? A focus on such questions is what defines the second transactional strand: the power approach.

The power approach

In simple terms, the power approach asserts that so long as leaders have the power to reward their followers, they can get those followers to do whatever it is that they (the leaders) want. If leaders don’t have power, they can’t mobilize followers, and their leadership aspirations will be “neutralized” (Kerr & Jermier, 1978). A leader without power is thus seen to be incapable of leadership. Under this model, the key to leadership is therefore to get one’s hands on power (by whatever means possible), so that you can be the person calling the shots.4 Such ideas are well captured in the writings of the social anthropologist Frederick Bailey based on his cross-cultural fieldwork in India, Britain, and the United States:

The strong leader commands: the weak leader asks for consent. The strong leader has men at his disposal like instruments: the weak leader has allies…. The strong man has ready access to political resources: the weak leader does not.

(Bailey, 1980, p. 75)

This approach to leadership is typically traced back to the writings of Niccolo Machiavelli, the 15th-century Italian statesman, writer, and political philosopher. In particular, it is associated with his book The Prince (Machiavelli, 1513/1961)—an analysis of “the deeds of great men,” which was presented in the form of an instruction book for would-be leaders (i.e., princes). This contained recommendations of the following form:

It is far better to be feared than loved if you cannot be both. One can make this generalization about men: they are ungrateful, fickle, liars, and deceivers, they shun danger and are greedy for profit; while you treat them well they are yours. They would shed their blood for you, risk their property, their lives, their sons, so long … as danger is remote, but when you are in danger they turn away…. For love is secured by a bond of gratitude which men, wretched creatures that they are, break when it is their advantage to do so; but fear is strengthened by a dread of punishment which is always effective.

(Machiavelli, 1513/1961, p. 71)

Although such views imply that both leadership and followership are pretty vulgar processes, as Sik Hung Ng (1980) has pointed out, Machiavelli was generally keen to represent leadership and the use of power as a skill and art, rather than as a blunt and sinister instrument. In part this was a response to the dangers he foresaw if princes were only followed on the basis of the resources at their disposal—in particular, because followers were being paid for their services. Thus, in a chapter dealing with the hazards of mercenary armies, he observes:

Mercenary and auxiliary troops are useless and dangerous. If a prince bases the defence of his state on mercenaries he will never achieve stability. For mercenaries are disunited, thirsty for power, undisciplined and disloyal; they are brave among their friends and cowards among the enemy … they do not keep faith with their fellow men…. The reason for this is that there is no loyalty or enducement to keep them on the field apart from the little they are paid, and that is not enough to make them want to die for you.

(Machiavelli, 1513/1961, pp. 51–52)

More generally, though, approaches that see leadership as a power process tend to be promoted by researchers whose primary interest is in power and who are keen to encompass leadership within their analytic frameworks. Over the last 50 years, the most influential work in this mould is that of John French and Bertram Raven (1959). These researchers are probably best known for a taxonomy that identifies six ways in which leaders can achieve power over others (summarized in Table 2.2). Each of these is related to leaders’ possession of one of the following types of material or psychological resources: (1) rewards; (2) coercion; (3) expertise; (4) information; (5) legitimacy, and (6) respect.

The ideas here are all reasonably self-explanatory. For example, if we take the case of a team leader who wants her subordinates to participate in a training weekend, we can see that her ability to ensure those subordinates’ participation may be attributable to a variety of factors. In the first instance, the subordinates may participate on the understanding that the leader has the ability to reward them for their effort (e.g., by paying overtime, or recommending them for promotion; reward power). On the other hand, participation may be encouraged for exactly the opposite reasons, with subordinates knowing that unless they attend they will be punished in some way (e.g., by being passed over for promotion, or being given more onerous duties in the future; coercive power). Less instrumentally, they may participate because they recognize the leader’s expertise and her ability to manage both their interests and those of the team (expert power) or because the leader is

able to present a logical and persuasive case for participating—perhaps pointing to the useful knowledge and skills that the subordinates will acquire (informational power). And finally, of course, they may participate because they acknowledge the leader’s right to tell them when to work and what to do (legitimate power) or because they like, respect, and look up to her (referent power).

From this perspective, leadership is considered primarily a question of amassing resources and then using them in the most effective ways. How is this to be done? Most researchers (e.g., Bacharach & Lawler, 1980) respond in contingency terms—suggesting that the answer depends on the personality of the person concerned and structural features of the situation at hand. Specifically, it is suggested that how power is (and should be) used depends on such factors as: (1) a person’s office or structural position; (2) his or her expertise and personal characteristics (especially his or her charisma and leadership potential); and (3) the opportunity to exercise power. So, in order to get staff to attend the training event, our manager might be well advised to rely on legitimate power rather than coercive power if her position carries with it no authority to punish and she is personally opposed to this tactic, and if, at the same time, she has relevant status (e.g., responsibility for organizing public relations activities).

Consistent with such an approach, a large body of research supports the view that how and when leaders (and others) use power in organizations depends on a range of contextual elements. For example, survey research by Robert Kahn and colleagues (1964) found that managers’ perceived ability to use different forms of power depended on the status of the person whose behavior they were attempting to control. As Table 2.2 indicates, people felt that expert and informational power could be used on any co-worker regardless of his or her status, but that other forms of power could only really be used on subordinates. Other studies also suggest that the ability to use different types of power depends, among other things, on the norms of the organization and the personal style and background of the would-be user (e.g., Ashforth, 1994).

Clearly, then, power—so often ignored by psychologists—is another key ingredient that is necessary to understand leadership. Yet power is not simply something that leaders have (or don’t have) as individuals; it is also something that they have by virtue of other people. For leadership involves harnessing the power of others, whether to batter down old regimes and old institutions or else to build up existing institutions, buttress existing laws and regulations, or realize existing policies. In this sense it is important to distinguish, as Turner (2005) does, between power over and power through. As French and Raven suggest, a leader can have power over others by virtue of the resources under his or her control (e.g., the ability to reward and punish); but this needs to be distinguished from the power that accrues to a leader by mobilizing others and inspiring them to follow the path that he or she has laid out. As we indicated at the very start of this book, leadership is much more about the latter process than the former. That is, it is not about coercion and brute force but rather about influence and inspiration.

This takes us back to a point we raised in the previous section—and to which we promised to return. For leadership might involve power (just as it involves exchange), but we need to ask whether the nature of power (like the terms of exchange) is a condition of effective leadership or an outcome of the leadership process. Do good leaders depend on power, or do good leaders produce power? Should we place power only at the start of the leadership process or also at its end?

These questions raise two further concerns that surround transactional approaches (both exchange-based and power-based). The first is that the model of leadership they present is essentially contractual. Thus, at best, they envisage a cold economic relationship between leaders and followers in which each party is thinking in terms of benefits or rewards and asking, “What am I getting out of this?” At worst, they suggest a conflictual relationship in which the parties are working against each other. To quote Frederick Bailey again:

Although it sounds a paradox, the opposition which exists between two rivals also exists in some degree between a leader and his followers. This relationship, too, can be visualized as one of relative access to resources. Insofar as a leader is able to influence and direct his followers’ actions, he does so by expenditure of resources…. Questions about a leader’s control over his team are [thus] questions about the relative size of his political resources as measured against the political resources independently controlled by his followers.

(Bailey, 1980, pp. 36, 75)

In either case, this seems like an unpromising basis for leadership, certainly if one views this as a process of influence whereby the aim is to shape what people want to do rather than induce or force them to do things against their will. In line with this point, there is a large body of research that indicates that people are much less motivated when they do things for extrinsic rather than intrinsic reasons (i.e., doing them because they bring valued rewards— such as money—rather than because they are valued for their own sake). Indeed, there is evidence that the introduction of extrinsic factors can actually have a demotivating impact (e.g., Lepper, Greene, & Nisbett, 1973). In other words, if we are encouraged to do something only because we think we will be rewarded for doing so, rather than because we inherently want to, then ultimately we may not want to do it all—especially once the rewards are removed.

In the same vein, inviting leaders and followers to stop and ask themselves, before they do anything together, “What’s in it for me?” is actually a good recipe for encouraging both to stop doing anything at all (see Tyler & Blader, 2000; Smith, Tyler, & Huo, 2003). Indeed, the evidence suggests that people’s willingness to engage in a whole range of positive citizenship behaviors (e.g., helping out new employees, attending open days, doing unpaid overtime when necessary; Organ, Podsakoff, & MacKenzie, 2006) depends on them not asking this sort of question—partly because, if they did, the answer would often be “Not much.” The task of leadership then, is often precisely to shift people from thinking about “what’s in this for me” to thinking about “what’s in this for us.” To cite a famous speech that we will have reason to return to on several occasions (Kennedy’s inaugural of January 21, 1961) and invoke an idea that will dominate the rest of this book, the task is to encourage people to “ask not what your country can do for you—ask what you can do for your country” (MacArthur, 1996, p. 486).

Such problems are even more acute if the transactions between leaders and followers are seen to be based on leaders’ power. For the best way for leaders to convince others to follow their orders is not to promise rewards for obedience or to threaten punishment for defiance (see Reynolds & Platow, 2003). As Machiavelli observed, mercenaries make bad followers. So do slaves. For this reason, as a host of commentators have remarked, evidence of leaders attempting overtly to manipulate followers by means of either reward or punishment is an indicator not of their leadership’s success but of its failure. The naked use of power is neither a badge nor a secret of a leader’s influence. It is its ruin.

This neglect of influence feeds into the second of our issues. It is a variant of our perennial concern with the static and inflexible nature of current models of leadership—although here the concern is not so much with the conception of leaders or followers but with the analysis of what happens between them. That is, transactional models treat leaders and followers as if they were locked into a closed system. Leaders can exchange a fixed quantity of existing resources with followers in order to negotiate their way or else they can expend their superior resources in order to impose their way. Metaphorically, the choice is between the leader as an accountant weighing up the profit and loss columns or else the leader as an enforcer, imposing discipline with carrots and sticks.

Because there is no place here for using influence as a means of achieving true attitude change (since all one ever requires followers to do is yield to one’s wishes), nothing new can be brought into being. As we have argued, these models leave no place for leaders to create a new sense of value or to create new reserves of power. To borrow Weber’s language, leaders are no longer an alternative to “the routinized economic cosmos”; they no longer promise to deliver us from “a polar night of icy darkness.” Rather they are a fixed part of that cosmos, forever locked into that darkness. And, even without sharing in Weber’s enthusiasm for a Bismarkian savior, there is surely something missing here. One does not need to adhere to the heroic and romantic view of leadership to acknowledge that models of leadership that have no place for creativity, agency, and change are models without a heart. Certainly, to the extent that they lack these things, they will fail to capture what it is that both lay people and professionals mean when they speak of leadership.

The importance of that “special something”

The transformational approach

A problem with many of the approaches that we have considered up to this point is that their mechanical structure seems to reduce leadership to a mundane algorithm in which there is nothing particularly special or uplifting. In many ways, it was this concern that led the biographer and political scientist James MacGregor Burns (1978) to write Leadership, the Pullitzer Prize-winning text in which he expounded the principles of transformational leadership. Along the lines of our analysis above, Burns prefaced his work with a stark assessment of the failings of prevailing approaches—in particular, those that set leaders apart from followers and those that see leadership as being about naked power rather than social influence. True leadership, he contended, arises from working with followers and is about much more than simply satisfying their wants and needs in exchange for support. In particular, he suggested that it arises from an ability to move beyond a social contract whereby people do things because they feel obliged to. Instead, leadership engages with higher-level sensibilities that inspire people to do things because they want to, and because they feel that what they are doing is right. As Burns put it:

Leaders hold enhanced influence at the higher levels of the need and value hierarchies. They can appeal to the more widely and deeply held values, such as justice, liberty and brotherhood. They can expose followers to the broader values that contradict narrower ones or inconsistent behavior. They can redefine aspirations and gratifications to help followers see their stake in new, program-oriented social movements.

(1978, p. 43)

Burns expanded on these ideas by drawing extensively on the influential motivational theorizing of Abraham Maslow (1943) as well as Lawrence Kohlberg’s (1963) work on moral development. A key idea in both approaches is that human development proceeds in hierarchical stages such that people progress from lower-level understandings of themselves and their world through to more sophisticated understandings. At low levels, needs and morals are thought to be dictated by relatively base urges and drives (e.g., for money, food, and safety), but as people develop these are replaced by loftier concerns for things like self-actualization, self-esteem, companionship, and belonging. For Burns, a key feature of successful leadership—what made it transformational—was that it helped people progress up such hierarchies, thereby allowing them to scale greater psychological and moral heights. Thus, on the one hand, great leaders are people who are going on this developmental journey themselves, but on the other hand, their leadership is effective because it helps followers to go on the same journey:

Because leaders themselves are constantly going through self-actualization processes, they are able to rise with their followers, usually one step ahead of them, to respond to their transformed needs and thus to help followers move into self-actualization processes. As the expression of needs becomes more purposeful … leaders help transform followers’ needs into positive hopes and aspirations.

(Burns, 1978, p. 117; original emphasis)

For Burns, though, successful leadership (particularly in politics) is not just about producing individual improvement. It is also about producing success at a collective level. In 2008, this was witnessed in the success of Barack Obama’s clarion call of “Yes we can!” As a large number of commentators have observed, this slogan was appealing partly because it suggested that, individually and as a nation, Americans could regain some of the moral stature that many felt they had lost under the previous administration of George W. Bush.

Burns’ analysis succeeds in capturing important features of the leadership process that, as we have just seen, other theories overlook. In particular, it clarifies the point that leadership has a collective dimension that enables and inspires individuals to rise above, and to go beyond, mercenary concerns of contractual obligation and exchange. Nevertheless, this commitment to the collective dimension, while striking and important, is somewhat ambivalent. In particular, this is because there is a clear tension between Burns’ collectivism and the tenor of the theories on which he drew. Thus, whereas Burns suggests that leadership involves group-based processes of mutual respect and shared perspective, both Maslow and Kohlberg assume that the highest state (of motivation and morality, respectively) is characterized by individual autonomy (see Haslam, 2001). When push comes to shove, the collective dimension of leadership thus tends to recede into the shadows.

This can be seen most clearly when one looks at research that has been informed by the transformational tradition and that has attempted to translate Burns’ ideas into practice. This research can be divided into two streams. On the one hand, those taking a measurement approach examine the extent to which leaders meet predefined transformational criteria. On the other hand, those taking a behavioral approach examine what it is that transformational leaders actually do. Again, we can consider these two approaches in turn.

The measurement approach (revisited)

When it comes to exploring transformational leadership at work today, a common strategy is simply to try to assess the transformational capacity or impact of any individual leader. One of the most popular tools that is used for this purpose is Bass and Avolio’s (1997) Multifactor Leadership Questionnaire (MLQ). This seeks to identify four components of transformational leadership: (1) idealized influence (or charisma); (2) inspirational motivation; (3) intellectual stimulation; and (4) individualized consideration. As well as requiring individual leaders to complete the MLQ themselves, it is also typically completed by a person’s superiors, peers, and subordinates (as well as outsiders—e.g., clients) as part of a process of 360 degree feedback. The idea here is that calibration across these various parties allows for more valid assessment of the extent to which a person possesses each of these characteristics. So, for example, if a leader believes that he is very effective in increasing others’ willingness to try harder, but his peers and subordinates do not share this view, then there are grounds for doubting how truly transformational he really is.

A clear advantage of such procedures over many of the standard personality tests that we have alluded to in previous sections is that they recognize that characteristics such as charisma are conferred by followers as much as they are possessed by leaders themselves. On the downside, though, the approach still treats these characteristics as stable and fixed, rather than as dynamic and negotiable. Moreover, it is largely descriptive. That is, it provides little or no insight into the processes that actually lead to a given leader being seen as influential, inspiring, stimulating, and considerate.

In effect, then, the measurement approach treats transformational leadership as something of a “black box”—a state that every leader aspires to, and that all followers seek in their leaders, but one whose origins remain unknown. Perhaps more insight into these processes might be gleaned by looking at leadership in action and seeing what it is that transformational leaders actually do. This takes us to the behavioral approach.

The behavioral approach

In effect, behavioral research into transformational leadership represents a more forensic approach to the task of divining the secrets of great leaders than that provided by the popular texts that we discussed in Chapter 1 (see Table 1.2). Its roots go back over 50 years to the studies conducted by Edwin Fleishman and a number of his colleagues at Ohio State University during the 1940s and 1950s (Fleishman, 1953; Fleishman & Peters, 1962). In the first phase of this research, nearly 2,000 descriptions of effective leader behavior were collected from people who were working in different spheres (industry, the military, and education). These were then reduced and transformed into 150 questions that became part of a questionnaire (the Leadership Behavior Description Questionnaire; LBDQ) that was then administered to employees in a range of organizational contexts with a view to identifying the behaviors associated with both effective and ineffective leaders.

As one might expect, the LBDQ identified a broad range of potentially relevant leader behaviors. However, two categories of behavior emerged as being particularly important: consideration and initiation of structure. Consideration relates to leaders’ willingness to attend to the welfare of those they lead, to trust and respect them, and to treat them fairly. Initiation of structure relates to the leader’s capacity to define and organize people’s roles with a view to achieving relevant goals.5 Along very similar lines, more recent studies have suggested that these same behaviors might underpin transformational leadership. In particular, in their best-selling book In Search of Excellence: Lessons from America’s Top Companies, two of the characteristics of successful leadership that Tom Peters and Robert Waterman (1982) identified as most important were “A bias for action” and “Productivity through people.” On the basis of their research, the “transforming leader” who possesses these attributes is described by Peters and Waterman as follows:

He is concerned with the tricks of the pedagogue, the mentor, the linguist—the more successfully to become the value shaper, the exemplar, the maker of meanings. His job is much more difficult than the transactional leader, for he is the true artist, the true pathfinder. After all, he is both calling forth and exemplifying the urge for transcendence that unites us all.

(1982, pp. 82–83)

Like many other disciples of transformational leadership, Peters and Waterman provide a powerful description of the capacity for leadership to rise above the mundane and be a source of followers’ enthusiasm and sense of higher purpose (see also Bass & Riggio, 2006; Kouzes & Posner, 2007). But beyond that, they don’t take us very far in understanding what is actually involved in successful forms of “initiation of structure” and “consideration.” To be a transformational leader exactly what sort of structure should you initiate? And to whom should you be considerate? And when will followers respond favorably to such initiatives on the part of their leaders?

A failure to answer such questions has meant that would-be leaders often resort to a literal interpretation of the term “transformational” and seek to demonstrate their leadership credentials by restructuring their organization at the first available opportunity. Indeed, the widespread belief that one cannot be a good leader unless one has subjected an organization to radical transformation represents one of the very negative legacies of the transformational approach. As often as not, such restructuring proves unsuccessful. Rather than carrying followers along it invokes their resentment and opposition. For example, in the case of organizational mergers, Deborah Terry (1993) observes that “contrary to the assumption that [they] are a potentially beneficial business practice, they typically engender negative reactions in employees and more than half of them fail to meet their financial objectives” (p. 223). This has meant that in many organizational contexts, “transformational” is code for “toxic”6 (Carey, 1992). Further telling proof of this point is that, within five years of writing their book, one-third of the “top companies” that Peters and Waterman studied were in severe financial difficulty (Business Week, 2001). One reason for this is that restructuring is often a stimulus not for engagement but for disengagement, a catalyst not for leading but for leaving (Jetten, O’Brien, & Trindall, 2002).

All in all, then, this work makes a strong case for reintroducing the idea of transformation, but it does not take us much further in understanding what it is or when it works. In part, this is because the analytic focus remains firmly on the leader as an individual. That is, while it may be acknowledged that transformational qualities have to be recognized by followers, the research stops with the recognition of these qualities. There is no focus on how transformations are justified to followers, how they are received by followers, when they are supported or opposed by followers: when, that is, the leader’s vision becomes shared rather than his or hers alone. Without addressing these questions, the promises of transformational leadership prove attractive, but ultimately incomplete.

Conclusion: The need for a new psychology of leadership

In many ways we have come full circle. In response to the excesses of the great man theory, its empirical deficiencies, and the shadow of the great dictators, post-war theory has placed a range of conceptual shackles on the ability of leaders to lead. According to different models, leaders are determined by the situation or at least have to be suited to the characteristics of the situation. Alternatively, leaders have to fit with the expectations of their followers, to satisfy their needs, or else possess resources that allow them to control their behavior. More and more the aura of heroism has dimmed as leadership has come to be treated as more and more mundane—as something that virtually anybody could do given the right circumstances or resources. In itself this may not be a bad thing, but it is worth asking whether things have got to the point where one should ask “But what is the point of leaders anyway?” If context determines behavior and leadership is tied to context, then what is the added explanatory (or indeed social) value of including a leader? If human behavior is determined by the exchange of resources, then what does leadership add? Is it time, as Emmanuel Gobillot (2009) contends, to announce “the death of leadership”—if not as an activity, then at least as a topic of any academic relevance?

Given the nihilism that lies behind this suggestion (and some of the research that prompts it), it is perhaps unsurprising to see that the leadership field has recently seen something of a backlash in the form of renewed conviction in the importance of the charismatic, transformational leader. But does this take us back to the future or forward to the past? The answer is probably a bit of both. On the one hand, contemporary transformational theorists move beyond the traditional individualism of leadership research and recognize the importance of collective processes and shared perspectives. Yet, on the other hand, transformational research is still very much about identifying individuals with “the right (transformational) stuff.” As Jay Conger puts it: “the heroic leader ha[s] returned—reminiscent of ‘great man’ theories—[but] with a humanistic twist given the transformational leader’s strong orientation towards the development of others” (1999, p. 149).

So, at the end of the long and winding road that we have traveled in this chapter, are we simply back where we started? No. The models we have explored here are clearly more sophisticated than those in the previous chapter and they have been subjected to far more rigorous testing. Indeed, in many ways, the lack of consistent evidence for the various theories we have considered is a sign of the maturity rather than the weakness of the field. What is more, they have established the necessity for any adequate theory of leadership to include at least four key elements:

1 It must explain why different contexts demand different forms of leadership.

2 It must analyze leadership in terms of a dynamic interaction between leaders and followers.

3 It must address the role of power in the leadership process, not simply as an input but also as an outcome.

4 It must include a transformational element and explain how and when any such transformation occurs.

Context, followers, power, transformation: four elements for a model of leadership. As we put it in the introduction to this chapter, these are ingredients that must be included in any viable model of leadership. But as we also argued, and have now seen, we are still some way from having a model that explains how these elements fit together. As Mats Alvesson (1996) observes, quantitative leadership research is in a “sad state.” Thus:

Rather than calling for five thousand studies—according to the logic of “more of (almost) the same”—the time has come for a radical re-thinking.

(Alvesson, 1996, p. 458)

This conceptual impasse has practical implications. In the world of leadership training (particularly at the elite end of the market) it means that practitioners tend to “talk the talk” of transformational leadership, but then fall back on psychometric tools that attempt to assess the leadership potential of particular individuals in order to pay their bills. Many readers of this book will be familiar with instruments like the Myers-Briggs Type Indicator (the MBTI; Myers & Myers, 1995), the Multifactor Leadership Questionnaire (used as part of 360 degree feedback), or some variant of the Least-Preferred Co-worker scale (after Fiedler, 1964) that assesses whether (among other things) they are task- or relationship-oriented. These tools are routinely branded (and rebranded) as new and revolutionary, but at their intellectual core they are old and tired. It is not surprising, then, that evidence showing that participation in leadership programs translates into improved leadership is elusive (e.g., see Varvell, Adams, Pridie, & Ulloa, 2004). It is not surprising either that any benefits that do accrue from these activities often seem to be incidental to the models on which they are based.

There is, however, one further element of leadership that has appeared intermittently throughout this chapter, which has briefly flickered into view and then flickered out. That element is the group. It was most clearly present in our discussion of transformational models. It also arose in our discussion of transactional models—notably when we observed that leadership is not necessarily an interaction between leaders and followers as individuals but rather between leaders and followers as group members. What leaders need to do, we argued, is to get people to think in terms of the collective interest. By the same token, what they need to do is to be seen to act in the collective interest.

Indeed, when one considers this point further, it becomes self-evident that to invoke followers is to invoke group membership. For leaders are not just leaders in the abstract. They are always leaders of some specific group or collective—of a country, of a political party, of a religious flock, of a sporting team, or whatever. Their followers don’t just come from anywhere. Potentially, at least, they too are members of the same group. To be sure, any given individual may fail to perceive this collective orientation, and respond on a different basis (e.g., the promise of personal reward). But if they did, they would not be participating in a process of leadership, simply one of exchange. And, if this were all there was to leadership, neither this book, nor the multitude of others that have been written on this subject, would have been necessary. The problems of leadership would have been solved. But, alas, they have not. As we see it, the core reason for this is that the essential causal role played by the social group remains conspicuously absent from most (if not all) previous treatments of this topic.

Leaders and followers, then, are bound together precisely by being part of the same group. This relationship is cemented not through their individuality but by their being part of (and being mutually perceived as part of) a common “we.” What this suggests is that the problems of individualism in leadership research, the problems of counterposing the agency of the leader to the agency of followers, the problems of balancing situational constraints and transformational potential, may be addressed by transforming the group itself from a marginal to a central presence in our analyses. That means devoting some time to understanding the psychology of the social group and how it provides the basis for a model of leadership that is contextualized and dynamic at the same time. That is the challenge for our next chapter.