This final chapter takes up the conflation of pets with children to examine how biopower infantilizes and commoditizes the liberal subject as it maps the drama of sovereignty onto the mundane territory of pet keeping.1 By examining the genre of animal autobiography, or biographies written from the perspective of an animal, I focus on texts that exemplify the slippage between commodification and subject formation, and I ask what happens to the animal voice when it finds expression in human language. Autobiographies in general produce writers as speakerly subjects and as objects for purchase. The conceit of the speaking and writing animal contributes to this commodification but also generates representational fissures through which a recognition and critique of biopolitical subjectivity become possible. The dog narrative is “a vital sub-genre” whose central premises “are fully evident by 1825,” but it is “in the first two decades of the nineteenth century, that dog-protagonist narratives become a popular sub-genre,”2 one whose popularity connects nineteenth-century explorations of liberal subjectivity with current practices of neoliberal subject formation. Through a case study of President George H. W. Bush’s dog “Millie,” I explore what happens when sovereign power and biopolitical governmentality encounter one another and the scene of bestiality gets rewritten as one of “puppy love.” I return to the connections between bestiality and sodomy here, but in the context of women’s writings to ask what functions of heteronormativity and what possibilities for queering arise in these affective relationships to animals. In bringing to a conclusion my attempt to rethink the “history of sexuality” as a “history of bestiality,” I examine the gender politics of animal autobiography by situating Millie’s Book, as Dictated to Barbara Bush, published in 1990, in relation to a broader genealogy of queer animal autobiography, focusing specifically on works by Katharine Lee Bates (the lesbian founder of American literary studies) and Virginia Woolf (whose biography of Elizabeth Barrett Browning’s dog Flush was a best-seller in America). Demonstrating that animal autobiographies explore structures of objectification that—at times inadvertently—unsettle the biopolitics they are meant to affirm, I conclude that animal representations locate a queerness at the very heart of liberal subject formation.3

“Puppy Love” for Mother’s Day

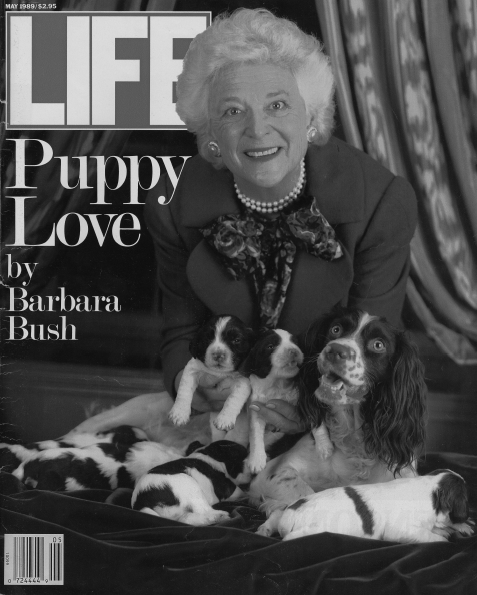

On the cover of its Mother’s Day edition for May 1989, Life magazine featured a photograph of First Lady Barbara Bush with her dog, Millie, who had just given birth to six puppies, five of them female (figure 5.1).4 The cover had beaten out, so publisher Kate Bonniwell informed her readers, two other options. One featured Ralph Lauren, who was profiled in this issue as a rags-to-riches entrepreneur and dedicated family man. Under the caption “America’s Toughest Job: The Working Mother,” the other alternate cover displayed a picture of Pat Menzel, who worked an astonishing 133 hours each week as a hairdresser and mother of two young sons. But the editors decided to go with the issue’s “biggest coup,” the “exclusive photo session at the White House with Barbara Bush, her dog Millie and newborn pups.”5 Winning out over other family themes, “Puppy Love by Barbara Bush” portrayed motherhood for Life magazine’s readers.

The magazine’s use of the first lady invoked and displaced the political aspirations of Mother’s Day. In the United States, Mother’s Day was first invented when Julia Ward Howe proclaimed the holiday in 1870 and wrote the “Mother’s Day Proclamation” as a call for peace and disarmament via women’s political agency.6 In response to the carnage and abject horrors of war, to which her “Battle Hymn of the Republic” had contributed, Howe called for women to

Say firmly: “We will not have great questions decided by irrelevant agencies. Our husbands will not come to us, reeking with carnage, for caresses and applause. Our sons shall not be taken from us to unlearn all that we have been able to teach them of charity, mercy and patience. We, the women of one country, will be too tender of those of another country to allow our sons to be trained to injure theirs.”7

Imagining a solidarity between women that hinged on affect to counterbalance the biopolitics of warfare and carnage, Howe insisted that women could develop relevant “agencies” via a politics of transnational gender solidarity. Her vision replaced the patriarchal family with a queer bond in that it withheld “caresses” from husbands and bestowed “tender[ness]” on other women. Secularizing religious vocabulary, Howe maintained that lessons of “charity, mercy and patience” needed to be reaffirmed by women’s relationship to one another. That relationship had children for its objects and mediators, children who in the process became collectively mothered. The affective bond between women, so Howe hoped, would prevent their sons from “unlearning” what their mothers had aimed “to teach them” and would prevent them from entering an apprenticeship in which they were “trained to injure” others. Far from imagining that women would exercise this pedagogical and affective agency exclusively in the home, Howe called for Mother’s Day as an opportunity for a “general congress of women” to assemble and to work toward a politics of disarmament and peace.8 With such a day given additional urgency by the wars against Native Americans and the Franco–Prussian War, Howe tried to imagine women’s affective agency as an affirmative biopolitics that could counter the thanatopolitics of domestic and international warfare.

Biopolitical Objects

These aspirations seem to have been lost in the commercialization of the holiday, but commoditization itself can tell us something about the exercise of neoliberal biopower and its figurations of subjectivity. Taking up Foucault’s claim that biopower emerged when “political power had assigned itself the task of administering life,”9 Gregory Tomso has pointed out that this administration of life founded liberal subjectivity on a paradox: liberal subjectivity was understood in terms of freedom, yet at the same time that freedom was grounded in a discourse of “natural” rights thought to be inherent in that liberal subject.10 The joint between these seemingly competing ideological strands was capitalism, with its ability, on the one hand, to promise individual freedom and its capacity, on the other hand, to insert objectified bodies into the machinery of production.11

Commenting on the simultaneous historical emergence of biopolitics and consumer capitalism, Eric Santner has recently argued that the “creaturely” comes to occupy the center of “literary and philosophical elaborations of human life under conditions of modernity” because it “names the threshold where life becomes a matter of politics and politics comes to inform the very matter and materiality of life.” Biopower blurs the distinction between subjects and objects; as Santner explains, “one might … speak of the birth of (the subject of) psychoanalysis out of the ‘spirit’ of the commodity.”12 Santner is engaging with arguments advanced by theorists of material culture who puzzle over the way in which the central division between use and exchange value cannot account for the structures of desire and affect that mark the relationship between subjects and objects in commodity culture. But Santner problematically follows the same trajectory as Giorgio Agamben in that he ultimately locates the creaturely within the human. In The Open, Agamben writes that the “decisive political conflict” is that “between the animality and the humanity of man” and analyzes a “central emptiness, the hiatus that—within man—separates man and animal.”13 What would it mean instead to see the relationship between man and animal as one that does not “separate” as much as connect them, and what would it mean to do so without letting go of the bodily and material dimensions of those relations and of the queer affections to which they give rise? Bill Brown has examined the key insight that Marxist and psychoanalytic theory share: that object relations are always-already subject relations. By developing what he calls “thing theory”—that is, an understanding of things’ capacity to exceed the relation to both objects and subjects—he argues that “the story of objects asserting themselves as things … is the story of a changed relation to the human subject and thus the story of how the thing really names less an object than a particular subject–object relation.”14 Pointing to the “object’s capacity to materialize identity,” he argues that “this relation, hardly describable in the context of use or exchange, can be overwhelmingly aesthetic, deeply affective; it involves desire, pleasure, frustration, a kind of pain.”15 In this chapter, I try to understand how we might read the animal as a “thing” in a way that is not associated with—or at least not limited to—the denial of subjectivity but rather is productive of alternative subjectivities. If one of the conditions of biopolitics is not just the control over but also the commercialization of animal life, how might we locate alternative subjectivities at its very core in those processes of objectification?

For Donna Haraway, this alternative is precisely where Marxist paradigms need to be expanded. Asking, “What happens when the undead but always generative commodity becomes the living, breathing, rights-endowed, doggish bit of property sleeping on my bed?” she argues that the Marxist “doublet of exchange value and use value” is insufficient; the dog is where “value becomes flesh again, in spite of all the dematerializations and objectifications inherent in market valuation.” Haraway asserts that we need to supplement the Marxist structure by adding to use and exchange value what she calls “encounter value”—that is, a recognition that “the human–animal companionate family is a key indicator for today’s lively capital practices…. Kin and brand are tied in productive embrace as never before.” She calls that embrace “biocapital” and argues that it emerged as “the crucial new kind of reproductive wealth in the late eighteenth and nineteenth centuries.” For her, the term biocapital not only modifies Marx but also expands Foucault’s understanding of biopower beyond his “own species chauvinism.” That is, through her attention to biocapital, Haraway wants to expand Foucault’s notion of biopower as a practice of regulating state subjects to a biopower that especially impacts creatures whom the state does not recognize as subjects. For her, encounter value stands in tension to the practices of biocapital in that it is the “underanalyzed axis of lively capital” that reveals to us the “face-to-face, body-to-body subject making across species” that forces us to expand our currently limited categories of subjectivity.16 In the first chapter of my book, I mapped that “body-to body” relationship in a reading of bestiality, which I reexamined in chapter 2 via the “face-to-face” encounter that Douglass and Lévinas have with dogs. Taking up in chapter 3 the question of how animal love gets transmuted from criminalized bestiality to Lockean pedagogy, I then explored in chapter 4 how “subject making across species” occurs between the dog Carlo and the child Emily. In this chapter, I want to draw these strands of discussion back into dialogue with each other by reading queer bodies in relation to childhood as a form of social reproduction that resists biocapital by its excessive relation to animals.17

One way to accomplish that reconfiguration is via a renewed inquiry into relational subjectivity in general and object relations in particular. Pointing out that psychoanalysis by and large ignores the significance of objects, Bill Brown has recently wondered “what a theory of object relations could accomplish if … it turned its attention to things.” Such an inquiry necessitates a reevaluation of what we might mean by objects in that, for most psychoanalysis, “the object, be it constituted through projection or introjection, is never not another human subject.”18 Yet the work of D. W. Winnicott on what he calls “transitional objects” forms a notable exception to this understanding of objects. Winnicott introduces the term to designate an “intermediate area of experience, between the thumb and the teddy bear, between the oral erotism and the true object-relationship, between primary creative activity and projection of what has already been introjected, between primary unawareness of indebtedness and the acknowledgment of indebtedness.” He defines transitional objects as ones that “are not part of the infant’s body yet are not fully recognized as belonging to external reality.” He claims that there is “an intermediate area of experiencing, to which inner reality and external reality both contribute. It is an area that is not challenged, because no claim is made on its behalf except that it shall exist as a resting-place for the individual engaged in the perpetual human task of keeping inner and outer reality separate yet interrelated.” Departing from his friend Melanie Klein’s analysis, he argues that “sooner or later in an infant’s development there comes a tendency on the part of the infant to weave other-than-me objects into the personal pattern. To some extent these objects stand for the breast, but it is not especially this point that is under discussion”; he insists that it is not the object’s “symbolic value so much as its actuality” that interests him. Whereas for Klein the concept of the internal object takes on primary importance, for Winnicott the transitional object is neither an internal object nor an external object either; “the transitional object is never under magical control like the internal object, nor is it outside control as the real mother is.” This intermediate area of experiencing, says Winnicott, is precisely where we need to rethink the relationship between the symbolic and the literal: “When symbolism is employed the infant is already clearly distinguishing between fantasy and fact, between inner objects and external objects, between primary creativity and perception. But the term transitional object, according to my suggestion, gives room for the process of becoming able to accept difference and similarity. I think there is use for a term for the root of symbolism in time, a term that describes the infant’s journey from the purely subjective to objectivity; and it seems to me that the transitional object (piece of blanket, etc.) is what we see of this journey of progress towards experiencing.” For Winnicott, this journey is developmental, but it lacks telos in that “this intermediate area of experience … throughout life is retained in the intense experiencing that belongs to the arts and to religion and to imaginative living, and to creative scientific work.”19 Whereas animals take on a teleological function in Locke, by Winnicott’s account, animal representations become the transitional object par excellence in that they form the nexus between the different forms of life and the different forms of representation that modernity—and here again I am invoking Bruno Latour—seeks to separate. The transitional object calls into question the extent to which the child ever fully relinquishes her participation in the real and imaginary upon entering into the symbolic order.20 It undercuts the trajectory of Lockean education and makes it possible to think of children—as Kathryn Bond Stockton has suggested—as growing sideways rather than growing up and thereby developing queer, alternative subjectivities that hinge on animals.21 I want to suggest that animal autobiographies locate us at the nexus between these different ways of thinking about objects—as the “mere” objects of commodity culture or as the recalcitrant transitional objects that function as biopolitics’ vexing and exhilarating surplus.

Biopolitical Commodities

The Life magazine cover featuring Barbara Bush and Millie invokes the political origins of Mother’s Day by depicting the first lady, but it uses sentimental iconography to displace the lived reality and abject labor of the working-class mother. Instead of forging bonds with other human women, Barbara Bush shares the solidarity of motherhood with her dog, Millie. By describing mothers’ affective agency as “puppy love,” the cover situates Mother’s Day in a saccharine commercialism that inscribes Howe’s vision of antipatriarchal family politics within conservative consumerism.22 Making motherhood revolve around the dog and her puppies places Millie in the service of an overdetermined commercial iconography that aims—but ultimately fails—to inscribe the photo in the heterosexual matrix that lies at the core of the modern nation-state.23

Although the Life cover photo is easily legible as a celebrity image, it is more difficult to discern what it and its title “Puppy Love” say about the relationships the photo depicts. The term puppy love is usually used figuratively to describe that first burgeoning of romantic attraction between teenagers. The term carries “contemptuous” overtones, as the Oxford English Dictionary informs us.24 Perhaps the best-known use of the term is Paul Anka’s 1959 hit “Puppy Love,” in which he wistfully reflects on the dismissal with which adults treat teenage affection.

Given these contexts, the use of the term puppy love as the title for Life’s cover in May 1989 strangely codes the relationships depicted as romantic. That raises the question of who exactly is experiencing “puppy love”: Does the term refer to the relationship between Millie and her puppies or to the one between Barbara Bush and the dogs, or is it the viewer who is expected to experience “puppy love” when confronting this image? Subjectivities multiply and become unsettled in affective relationships with pets. A search using the key word puppy love on Google Images renders, in addition to the occasional pornographic picture that explicitly connects “puppy love” to bestiality, images that show two puppies who presumably love one another and whom the viewer is expected to love. The images’ capacity to depict and elicit affection collapses the distinction between identification and objectification; it puts the puppies in the precarious position of anthropomorphized subjects and fetish objects. The puppies share with children that tenuous subjectivity of animated objects.25 Some of these photos replace one puppy with a child, breaking down the divide between the literal puppy and the figurative puppy. Functioning simultaneously as a stand-in for the puppy and for the viewer, this child becomes a mediator for an affection that crosses species barriers but also normalizes that boundary crossing by providing an anthropomorphic center.

Because this image of puppy love describes a sentiment and inscribes the viewer in the affect portrayed, it both infantilizes the viewer as a child and animalizes her as a puppy, all the while placing her in the adult role of lover and mother in relation to the animal. Placing Barbara Bush in the Life cover picture makes visible this lover–mother role: looming over Millie, she represents a dog lover and a surrogate mother in her relationship to Millie and the puppies, whose biological bond is highlighted by the fact that three of the six puppies are nursing. Coding the role of the lover–mother in terms of surrogacy and biology, around the two poles of the postmodern family, adoption, and reproduction, this image sets up a crisis of representation: although the photo participates in the symbolic ordering of family romance, it also disrupts the very process of symbolization that lies at the heart of the family.

Yet the cover tries to make the relationships it depicts conform to heteronormative social structures. The clearest explanation of “Puppy Love” as a descriptor of the photo lies in the song title’s capacity to frame motherhood nostalgically; Life magazine’s caption invokes that most wholesome of wholesome American decades, the 1950s, and places an iconic value on family. Reframing teenage romance as family romance, “puppy love” designates identities that are constructed relationally by sentimental means of depiction. But the reference to puppy love firmly inscribes the relationships depicted here within the structures of the heteronormative family. The article itself enhances the cover’s romantic coding and compulsory heterosexuality: a photo showing Millie getting a “husbandly nuzzle from Tug III at his Kentucky farm” informs us that the “two were bred during inauguration week.”26 Note the use of the passive voice when it comes to the act of reproduction and the description of the dogs’ relationship: the “husbandly nuzzle” indicates that marriage is not reserved for human beings and can occur in other species so long as marriage remains heterosexual. It is indeed hard to imagine how Life’s readers would have reacted to this article if it had drawn on the language of dog breeding to describe Millie as a bitch who was decked.

Yet even without such language, the article is complicit in the crude sexual commodification of Millie. The text wavers between portraying Millie as a subject and describing her as an object—that is, as someone who, on the one hand, could enter into the consensual relationship that is marriage but who, on the other hand, cannot actively exercise her own sexual agency and—the passive voice here is important—was “bred.” The title of the article reads “Millie’s Six-Pack” and puns on the names “Millie” and “Bush” by invoking the Miller Brewing Company and Anheuser-Busch. It commodifies Millie and her offspring by troping on the manliest of manly commodities, beer, and it strangely masculinizes Millie by attributing to her the “six pack” usually associated with body-building men and not postpartum women; it portrays Millie not only as a bitch, but also as a butch. Through its repeated attentions to Millie’s body, the article and Millie’s Book, as Dictated to Barbara Bush try to work out a theory of sexuality via the discourse of species and vice versa.

Following up on the success of the Life article, Millie’s Book appeared in 1990. Written from the dog’s perspective and purportedly composed by Millie herself, Millie’s Book made it to number 1 on the New York Times nonfiction best-seller list and raised nearly $900,000 to promote literacy.27 Those sales figures meant that Millie, as the nonfiction book’s author, earned roughly four times George Bush’s salary as president and outdid by far the royalties he received later for his autobiography Looking Forward (1987).28

If biopolitics has a genre, it must surely be autobiography, which connects life (bio-) to writing (-graphy) and the self (auto-). Within the larger field of autobiography, animal autobiography forms a strange subgenre. Because autobiographies in general are preoccupied, as Sidonie Smith and Julia Watson have pointed out, with the “processes of subject formation,” the legacy of defining animals as objects that cannot speak would seem to categorically exclude animals from participation in this genre.29 And yet since the nineteenth century the conceit of writing animal autobiographies has been consistently popular.30 One explanation for this popularity might lie in attempts to appropriate the voice of the animal by submitting it to language, but I want to suggest instead that the animal voice—however anthropomorphized—remains an alien presence within language and unsettles the subject formations in which it participates.

The popularity of animal autobiographies coincided with and responded to the historical rise of biopolitics. Animal autobiographies connect us with a larger literary genealogy of animal writing that, as Teresa Mangum points out, looks “backward to the late-eighteenth-century sentimental novel, a form which remained popular through the nineteenth century despite being criticized as a debased, emotionally exploitative, feminized form which sought to awaken sensibility and benevolence rather than reason.” But animal autobiographies also “interweave sentimentality with the experiential, flawed view of human nature associated with realism.”31 As a genre, then, animal autobiography is interstitial in that it connects animals to sentimental and realist forms of writing and places them in dialogue with one another around a shared investigation of subjectivity.

Animal autobiographies take on two distinct forms. In the first, they are books written about an animal but from the perspective of a human being who makes the animal an essential reference point and partner in his or her own life story (John Grogan’s Marley and Me is a recent example of this form). The animal in this context is the vehicle for an autobiography of the human subject. But the opposite also holds true—the human is a vehicle for our understanding of the animal subject; because of its emphasis on relationships, animal autobiography constantly confounds the subject–object divide. Animal autobiographies locate us in an intermediary terrain where it becomes possible to rethink who counts as a subject and to critique biopower. In Dog Years: A Memoir, for instance, Mark Doty gives an account of the years he spent with his dogs while nursing his partner as he died of AIDS. Doty’s animal representations become a profound meditation on subjectivity in relation to the social negations of queer masculinity in the 1980s and enable a reflection on how to reaffirm life when confronted with its biological and political annihilation in the AIDS crisis. Animal autobiographies, then, do not simply reaffirm subjectivities but reinvent them via the relationships they represent. In the second form, animal autobiographies are books purportedly written from the animal’s perspective about his or her own life; they usually function as a kind of bildungsroman that playfully engages the conventions of Lockean pedagogy. Again, this second form of animal autobiography productively blurs the boundary between subjects and objects by making literacy available to the animal and allowing him or her to participate in the kinds of authorial and linguistic subject formation we usually reserve for human beings.

Millie’s Book begins with an account of how Millie came to live with the Bushes when their previous dog had died, and they were looking for a replacement. George Bush contacted the family’s friend Will Farish to see if they could have one of the dogs whom “Bar had fallen in love” with on a recent visit. Farish asked “if a girl would be all right” even though the Bushes “had never had a female dog before.” When Millie met the Bushes, “it was love at first sight. Both Bushes kissed me and I sat on Bar’s lap all the way to Maine.”32 In these descriptions, Millie goes from being an object of evaluation and negotiation, whose female gender might hinder her from meeting the criteria requisite for “Bar” falling “in love” with her, to acquiring the status of a love object on whom the Bushes lavish expressions of physical affection. Yet this romantically coded encounter, which the book underscores by including photos of the Bushes kissing Millie, is undercut by Millie making “a confession that is difficult for me to make”: in the evening, she recounts, Barbara Bush whispers to her, “You are so sweet, but you are so ugly. You have a pig’s nose, you are bowlegged, and your eyes are yellow.” Millie’s response to this statement is to see it as a challenge for personal betterment: “I knew immediately that I was going to have to try harder.”33 Because Millie’s agreeable temperament is not a matter of dispute, her attempts presumably are meant to be for physical self-betterment. In reflecting on her physical properties as subject to self-discipline, Millie occupies the central tension and fantasy of liberal subject formation: that biology itself is subject to discipline.

Throughout the book, Millie occupies a double status as pure object and object of affection, with the two roles at times reinforcing and at other times standing in tension with each other. The book’s attempted humor revolves around the dog’s anthropomorphizing herself when the narrative insists that, for all her aspirations, she remains a dog. But that sense, that she remains a dog, then also undercuts the book’s own conceit—its anthropomorphizing depictions of Millie. Even in the act of negating her subjectivity—she is not a dog, she is a human; she is not a human, she is (only) a dog—the narrative inadvertently opens up a space for the alterity it negates.

The book stages a rivalry between Millie and Barbara Bush that revolves around who is the better wife and mother. Millie informs us that “the alarm goes off at 6 a.m. The Prez says that I go off a few minutes earlier by shaking my ears pretty hard in their faces.”34 Here, she is likened to an alarm clock, but an alarm clock that has physical, intimate contact with the Bushes; she is in fact describing herself as the third party in their marriage bed. Millie has an affective relationship with each of the Bushes individually and also serves as a mediator for their relationship to each other. Moreover, she facilitates their relationship to the public: recounting the beginnings of the 1988 presidential campaign, Millie remembers that “posing for Vanity Fur, the stylish fashion magazine, made me feel that I was giving my all for George.”35 Millie’s comment establishes an intimacy between her and the president; she strangely participates in or even usurps the role of the wife. Millie functions as an extension as well as a stand-in for Barbara Bush, and her role as the supportive wife who selflessly gives her “all for George” models 1950s marital iconography.

Millie’s role as spousal object is brought home to the reader when she underscores her own superior ability to fulfill her role as mother in competition with Barbara Bush. Recounting that Barbara Bush was unable to tell the female puppies from the male puppy, Millie scoffs: “To think that Bar thought she was going to help me when she couldn’t tell a boy from a girl!” This insufficiency when confronted with biological needs and necessities again manifests itself when Barbara Bush turns her back while the puppies receive their first shots. Millie comments: “Please note the lady who thought that she could help deliver the pups! Makes me wonder what kind of mother she was.” The culmination of these claims lies in Millie’s own reading of her appearance on the cover of Life: “I could only conclude that I was their selection for 1989 Mother of the Year.” These reflections are juxtaposed by Millie’s own seeming recognition of her and her offspring’s status as objects, not subjects. Reflecting on her special friendship with the Bushes’ granddaughter Marshall, she recounts that “on her third birthday, I gave her a puppy … Ranger, my only son.”36 This passage creates a strange complicity between affect as a site for subject formation and affect as the site of objectification. Because of the “special friendship” that she shares with Marshall, Millie wants to exchange a bond of affection with the child. The gift that she gives is her own child, Ranger. In that exchange, the child Marshall becomes recognized as a subject, whereas Ranger is objectified as a gift.

The book integrates such an astonishing aside seamlessly into a narrative of Millie’s motherhood by incorporating it into an account of family itself as the place where affective agency stands in service to biopolitical discipline. The meaning Millie attaches to family becomes evident when she tells us about her appearance, simultaneously with the Life cover, in the July 1989 issue of The Washingtonian, where she was featured as “Our Pick as the Ugliest Dog: Millie, the White House Mutt.” Although this assessment of her as homely resonates—so Millie points out—with Barbara Bush’s attitudes, Millie lists the many people who came to her defense by writing fan mail and other publicity pieces, such as the one released by the office of Senator Bob Dole, whose own dog Leader extolled Millie, saying that “as first dog, Millie has set a great example for millions of American dogs. She is raising a family, doesn’t stray from the yard, and does her best to keep her master in line. It’s just not right for her to be hounded like this.”37 The letter explicitly ties Millie’s biological reproduction—the fact that she is raising a family—to her role as an “example” for the nation (“millions of American dogs”), for whom she models discipline in her own obedience to rules (“doesn’t stray from the yard”), and her ability in turn to act as a disciplining agent who tries to “keep her master in line.”

The biopolitical discipline Millie exercises hinges on her double performance in the narrative as physical object and linguistic subject. Her own response to The Washingtonian focuses, like Leader’s, on her role as a mother but reads that role as the cause of the article. She argues that the picture included with the article “was taken the very afternoon of my delivery. Show me one woman who could pass that test, lying on her side absolutely ‘booney wild’ (family expression for undressed) on the day she delivered six babies!”38 Tying her appearance to her recent delivery, Millie portrays herself as exemplary for all woman, who would be unable (according to this book’s aesthetic standards) to “pass the test” of looking beautiful after giving birth. The comment suggests that the act of giving birth is a hindrance to the aesthetics of motherhood: the passage brings this point home by coding nakedness through the expression “booney wild”—that is, by emphasizing that the act of giving birth is uncivilized and undisciplined (“wild”) labor that does not participate in the aesthetics of nudity or the discipline of representation. Yet the passage also exercises such aesthetic discipline through the inclusion of the peculiar aside: “‘booney wild’ (family expression for undressed).” Portraying biological motherhood itself as an embarrassment, the invocation of a familial phrase shifts the attention to motherhood as a cultural construct. As a cultural construct, it takes on a privileged role in that it creates its own idiom for the description of biology.

This invocation also creates the illusion that the narrative itself is part of a multilayered translation, from familiar terms into the public idiom, from dog into human terminology, from the lived experience of the real into the terms of the symbolic order. With these references, the book insistently draws attention to Millie’s own role as author and to the central conceit of dog authorship. Millie describes her schooling and her ongoing relationship to textual reception and production. Before being sent to live with the Bushes, Millie’s previous “owner” “sent me to school to brush up on my manners.” Although this comment places Millie in the context of a gender-specific setting, the finishing school, she highlights her relationship to literacy when she mentions what “the papers” reported on any given day and recounts that she received “more than my fair share” of mail once the puppies were born. In response to those letters, the White House mail room sent out a thank-you card, which “the babies and I signed also”: the card had the White House at the top, the thank-you note in the middle, and seven paw prints, one large and six small, framed on either side by the signatures of Barbara Bush and George Bush at the bottom.39 To the extent that a signature establishes authorial subjectivity, Millie repeatedly asserts herself in these contexts as the author of her own text; as its topic, she simultaneously occupies the position of the object under discussion.40

What truly bears underscoring in this context is the book’s classification as nonfiction. The copyright for Millie’s Book was taken out by the Barbara Bush Foundation for Family Literacy. This foundation linked literacy with so-called family values, as the book’s opening mission statement makes clear: “The mission of The Barbara Bush Foundation for Family Literacy is: 1. To support the development of family literacy programs … 2. To break the intergenerational cycle of illiteracy … 3. To establish literacy as a value in every family in America.” The book itself is not sure what to do with this frame or with its conceit of Millie’s authorship. On the one hand, it consistently affords Millie literacy, yet she finds it necessary to reflect at the end: “One last thing I’d better make clear. I know the Bushes love me. They told me so. But they love people more, all people. So I have written this book and the proceeds will go to help people, all people. I hope it will strengthen families and family life in our great America. The Prez used to tease Bar and tell her that if she’d ‘stick with him, he’d show her the world.’ And he did. The Prez told me that if I’d stick with him, he’d show me my name in a THOUSAND POINTS OF LIGHT, and he did.”41 The phrase “thousand points of light” was one that Bush frequently used in speeches and thus firmly links Millie to the president’s politics. It referred to community organizations throughout the United States, such as the Bush Literacy Foundation, which were working toward the improvement of American society. In arguing that Millie’s name would be inscribed in a thousand points of light, the book is making Millie herself into a volunteer for literacy education and affording her a role in the betterment of American society. Her authorship then inscribes her firmly in the project of creating a society that affirms the superiority of the human: in the end, the dog takes on a secondary role to “people, all people.” Millie’s own text affirms the species hierarchy in which the dog underscores the superior status of human beings. That hierarchy emphasizes biology in its hierarchical ranking of species. Yet at the same time, it makes biology an insufficient condition. In writing, “I hope it will strengthen families and family life in our great America,” Millie in fact performs an interesting shift. Up to this point, she has been portraying the way in which she herself strengthens the Bushes’ family life, but she now substitutes her book—“it”—for herself. The dog and the book function as stand-ins for each other in shoring up American family life. This final move undercuts the very distinction that the narrative purports to uphold—between the real (the realm of the dog) and the symbolic (reserved for human beings); it places the dog and the book in interchangeable relation to one another and suggests that, to the extent that liberal subject formation hinges on literacy, it is firmly ensconced in its relationship to the animal other that lies at its core. The narrative’s end undercuts the distinctions and hierarchies it wants to affirm.

Queering Biopolitics

But what are the consequences of that slippage for our understanding of animal autobiography as a site for alternative subject and family formations? Millie’s multiple subject and object positions speak to the insufficiency of mapping her onto a Marxist matrix of use and exchange value. The instability of her positions hinges on the relationships into which she enters, with the other characters in her narrative and with the reader—that is, with the real and virtual others she encounters. For Donna Haraway, these moments of encounter between human beings and other species call for an examination—as I quoted earlier—of the “underanalyzed axis of lively capital” that reveals to us the “face-to-face, body-to-body subject making across species” that force us to expand our currently limited categories of subjectivity. In this section, then, I want to explore how animal autobiographies stage moments in which human beings and animals come face to face with each other and what that encounter tells us about expanded categories of subjectivity. Revisiting the kind of encounter with dogs that Emmanuel Lévinas and Frederick Douglass used to theorize race (chapter 2), I examine the face-to-face encounter with animals from the perspective of gender. What particularly intrigues me in this context is Michel Foucault’s insight that biopolitics not only regulates gender and sexuality but also becomes the domain for the formation of queer subjectivities. I draw on queer-authored case studies to explore how animal autobiographies perform two kinds of affective queering: seeing the animal as a relay between same-sex partners and crossing the species boundary. These works also present a challenge to the current implicit focus on the human that underwrites queer theory and that has recently come under pressure—for instance, in Jeffrey Cohen’s puzzlement that “a critical movement predicated upon the smashing of boundary should limit itself to the small contours of human form.”42

Millie’s relation to Barbara Bush replicates a pervasive and significant trope that developed in eighteenth-century literature: the trope of the lady and the lapdog. As Laura Brown has demonstrated, “The image of the lady and the lapdog arises as a widespread literary trope at the same time as companion animals become widely evident in the bourgeois household.” In these depictions, “inter-species intimacies often substitute for human ones in precisely this way in the representation of pet keeping in the eighteenth century.”43 Teresa Mangum concludes that “the dog narrator’s gender, whatever it is, rarely signifies as important. Thus the dog provides a comforting substitution for the domestic heroine when she perfidiously questions the characteristics of which she is constructed: modesty, affection, submission, and loyalty.” Mangum’s work isolates the figure of the old dog in particular as “the canine voice of authority,”44 but we arrive at a different account when we examine the genre in relationship to children and children’s literature and see the dog as participating in and representing childhood. As Kathryn Bond Stockton has argued, the dog “is the child’s companion in queerness.”45 In the case studies on which I focus, the dog stands in for the “domestic heroine” at times, but also for the heroine’s children; when the dog functions as a substitute for human beings, it often mediates more than one substitutive relation. Because of this ability to facilitate different substitutive relationships and in the process to mediate different forms of intimacy, the animal’s sex and gender matter.

Millie’s authorship inadvertently returns sentimentality to its roots in a politically engaged gender politics in that Millie’s commercial success calls into question the very parameters of the patriarchal symbolic order and challenges our understanding of subject formation. For all the ways in which Millie is disciplined and performs her own disciplining as a heteronormative subject of biopower, what we have on the cover of Life is a queer family romance. In Barbara Bush’s account of “puppy love,” the referent for the affection and for the subjectivity the article constructs is doubled. We find out from Barbara Bush that she named her dog

after a very close friend of mine, Mildred Kerr—that is not c-u-r, but Kerr. [Millie] was trained to be a retriever, but she’s become a lover, not a hunter. We bonded immediately. She never takes her eyes off me. I never had a girl dog before. I had boy dogs all my married life. George loves Millie, but she is attached to me. I spend more time with her. I walk her at six a.m. and feed her—kibble only. She gets White House table scraps when the President slips them to her. He gives her showers—how else do you wash your dog? Every week or two we climb right in the shower with our dog. We use dog shampoo. She has her own dog bed in our bedroom. She doesn’t always choose to use it, but she has one.46

Millie plays the roles of both a child and a woman. In turning from a hunter into a lover, she fulfills the wish that Julia Ward Howe had expressed for children to learn affection instead of aggression. But Millie is not just in the role of a child; she is also the symbolic referent for another woman, Mildred Kerr. She is named for Barbara Bush’s absent friend, whom she figuratively represents and whose “close[ness]” she literalizes via her daily physical proximity and intimate insertion into the Bushes’ married life. Millie seems to occupy the position of a transitional object in that she facilitates relationships that distinguish between subjects and objects but is herself neither the one nor the other. As a real object and a figurative subject, she is in between. From that position, she unsettles established patterns of subject formation and their concomitant gender paradigms. In displacing George, Millie functions as the other woman with whom mothers enter into “tender” relationships by Howe’s account. Much of that tenderness seems to hinge on the dog’s ability to gaze—on the fact that “she never takes her eyes off” Barbara Bush, who in turn feels “bonded” and “attached” to the dog. The encounter with Millie opens up multiple venues for affection and intimacy that exceed the narrative of heteronormative subject formation.

But theorizing the relational subjectivity that arises in the encounter between human beings and animals presents us with a problem: not only are we confronted with the iconic, heterosexual overdetermination of popular culture, but the preeminent theorists of relational subjectivity, such as Jacques Lacan, place animals and forms of subjectivity that do not conform to heterosexist iconography outside of the symbolic order, beyond legibility. Lacan initially excluded animals categorically from the first stage of subject formation: he argued that the “experience” of the mirror stage “is a privileged one for man. Perhaps there is, after all, something of the kind in other animal species. That isn’t a crucial issue for us. Let us not feign any hypotheses.” In his later writings, he grudgingly afforded animals participation in the mirror stage, only to exclude them from the symbolic order. Writing in the seminar on Freud’s ego theory, he argued that “living animal subjects are sensitive to the image of their own kind. This is an absolutely essential point, thanks to which the whole of living creation isn’t an immense orgy. But the human being has a special relation with his own image—a relation of gap, or alienating tension. That is where the possibility of the order of presence and absence, that is of the symbolic order, comes in.”47 This claim already presupposes that animals mirror only animals and that humans mirror only humans; the mirror stage relies on the precondition that the subject already recognizes itself as itself. The mirror stage is tautological in that it presupposes the kind of subject formation it is meant to exemplify—namely, human subject formation.

But what happens if we let go of that tautology? What happens if we allow the animal and the human to mirror each other? What consequences does that carry for the mirror stage and for the symbolic order? Jacques Derrida’s final work before his death, “L’animal autobiographique”—to which my account of “animal autobiography” is a critique as much as an homage—locates the autobiographical animal at the disavowed core of subject formation.48 Promising that he will speak frankly—that is, speak of naked truths in conceptualizing the modern subject—Derrida arrives via a series of puns at a point where he imagines what it would mean to appear naked in front of a cat who “has its point of view regarding me. The point of view of the absolute other; and nothing will have ever done more to make me think through this absolute alterity of the neighbor than these moments when I see myself seen naked under the gaze of a cat.”49 Mapping the cat’s gaze onto the very history of subjectivity that denies the cat a gaze, he inscribes animals within an autobiographical mode of writing that founds and confounds the parameters of representational subjectivity by rewriting the mirror scene as an encounter in which the animal reflects and refracts the human subject.50 In fact, for Derrida, the mirrored gaze of the animal becomes the privileged site at which, according to Lacan, “a relation of gap, or alienating tension” arises.51

However, Donna Haraway reads Derrida as himself becoming complicit with a Lacanian indifference to animals: “Somehow in all his worrying and longing, the cat was never heard from again in the long essay.” Haraway explains this failure by Derrida’s nudity, suggesting that “shame trumped curiosity, and that does not bode well for an autre-mondialisation,” a term by which she means a different way of looking at the world.52 The very attempt to imagine alternative subjectivities seems to fail, then, because the animal other is ultimately subsumed to the structures of human subjectivity. Haraway faults Derrida for promising to produce the animal as the subject of its own autobiography but instead making it the vehicle for his autobiography, which ties her critique back to the topography of animal autobiography that I mapped earlier.

However, I want to propose a different way of reading Derrida in conjunction with a scene from Flush, Virginia Woolf’s 1933 best-selling animal (auto)biography of Elizabeth Barrett Browning’s spaniel.53 Woolf explores the possibilities of creating a gaze that is not objectifying; here is her description of the first encounter between Flush and Elizabeth:

For the first time she looked him in the face. For the first time Flush looked at the lady lying on the sofa. Each was surprised. Heavy curls hung down on either side of Miss Barrett’s face; large bright eyes shone out; a large mouth smiled. Heavy ears hung down on either side of Flush’s face; his eyes, too, were large and bright: his mouth was wide. There was a likeness between them. As they gazed at each other each felt: Here am I—and then each felt: But how different! Hers was the pale, worn face of an invalid, cut off from air, light, freedom. His was the warm ruddy face of a young animal; instinct with health and energy. Broken asunder, yet made in the same mould, could it be that each completed what was dormant in the other? She might have been—all that; and he—But no. Between them lay the widest gulf that can separate one being from another. She spoke. He was dumb. She was woman; he was dog. Thus closely united, thus immensely divided, they gazed at each other. Then with one bound Flush sprang on to the sofa and laid himself where he was to lie for ever after—on the rug at Miss Barrett’s feet.54

Woolf imagines that each of them, the human and the animal, has a gaze and that there is reciprocity in looking: “each was surprised.” Figuring that reciprocity as one of rupture (“surprise”), Woolf nevertheless begins constructing a likeness between the human and the animal: despite being different species, they share certain physical attributes such as their curls, their eyes, and their mouth. These shared attributes amount to “a likeness”: they mirror one another. That mirroring establishes a moment of reciprocity that founds subjectivity; it is in the reciprocal moment when “they gazed at each other” that each comes to articulate a subject position: “here am I.” What is truly remarkable about that “here” is its displacement: it is not clear if the thinking subject is present unto him- or herself—that is, if the thinking subject is a Cartesian subject—or if instead the subject appears only in projective relationship. The end of the scene seems to bear out the first reading of the encounter in establishing a Cartesian subject: positing a “gulf” that separates the speaking human from the “dumb” animal, the scene seems to reaffirm the differences it temporarily unsettled.55 The very attempt to imagine alternative subjectivities thus seems to fail because the animal other is ultimately subsumed to the structures of human subjectivity.

Yet the second reading I proposed, that we see Woolf as creating a subject who appears only in projective relationship with the other, would turn this scene into an encounter that engenders relational subjectivities. Rei Terada has explained that emotion itself—the feeling evoked in this encounter—has an ambiguous status when it comes to subjectivity. Rejecting the notion that emotion serves “as proof of the human subject,” Terada argues that Jacques Derrida and Paul de Man “free a credible concept of emotion from a less credible scheme of subjectivity…. [T]he effect of this exploration is to suggest that we would have no emotions if we were subjects” because “auto-affection, Derrida argues, is necessarily second-order, and its secondariness both obstructs epistemology and enables emotion. Experience is experience at all only because of the self-difference of self-representation. Thus experience and subjectivity are incompatible.”56 The emotion and subjectivity we see exchanged in the gaze between Barrett Browning and her dog constructs their emotion and their subjectivity via and in the place of the other. Although the passage seems to reinscribe difference as the difference of the other, it also points to the difference of the self. If the scene points to the difference of the self, then the difference of the other in fact becomes not so much a marker of separation or of the failure to imagine an “autre-mondialisation” as a marker of resisting the inscription of subjectivity in a narrative of self-sufficiency. By refusing to collapse difference, the relationship between the woman and the dog enables different forms of being to persist. The woman and her dog are in a double relationship to each other, “closely united, thus immensely divided” because each represents the divisions and fractures at the heart of subjectivity itself.

Yet we may wonder how that subjectivity is gendered and, specifically, what role the animal plays in the gendering of that subjectivity, especially given Derrida’s emphasis on his nudity. Alice Kuzniar’s discussion of Flush is useful here for insisting that the gaze between human beings and animals offers an alternative to the male gaze: “The dog is therewith not a convenient substitute for a male partner but quite the opposite—a compassionate antidote to the shame suffered in a male-dominated world.”57 Derrida experiments with that shame in turning the cat’s gaze onto himself. But that reversal raises a further question: Does the sex of the gazing cat matter? Derrida’s cat linguistically has a sex: usually speaking generically of “le chat” in the original French, Derrida also occasionally refers to “la chatte,” especially when talking about other writers’ cats.58 He glosses over the difference between the male and the female cat when he argues that neither “le chat” nor “la chatte” can ever be naked and that nudity is the defining characteristic of “l’homme.” But being naked in front of a cat is not just foundational for an awareness of species; it is foundational for the gendering of subjectivity. Derrida would certainly have been aware that, as Robert Darnton has documented, “the power of cats was concentrated on the most intimate aspect of domestic life: sex. Le chat, la chatte, le minet mean the same thing in French slang as ‘pussy’ does in English, and they have served as obscenities for centuries.”59 Confronted with the cat that has a sex even if it can never be naked, man becomes masculine. Seeing the cat’s gaze, Derrida discovers his naked sex. That naked sex is a social construct in that it emerges in his relationship with the animal. As the foundational site for the construction of sexual identity, the cat’s gaze collapses the distinction between sex and gender and inscribes both in the relationship between human beings and animals.

Jonathan Lamb situates animal autobiography in a broader field of writing that he refers to as the “it-narrative,” in which material objects speak.60 Usefully mapping animals into complex literary genealogies, this association nonetheless fails to capture the key function of the autobiographical animal: to force the “it” into sexual definition. The encounter with the cat is foundational to the very possibilities of sexed and sexual identity. For that matter, it is only via the animal’s presence in the symbolic order that gendering can occur: after all, it is only in the third-person singular that we differentiate between “he,” “she,” and “it”; it becomes possible only in the third person to have binary categories of gender distinction but also the very indistinguishability, the “it,” of a hybridity that straddles gender and species. In order for the “I” to write itself, it needs not only the fracture of the mirror stage, but the profoundly alien “it” of the pet and the animal’s presence.

The hybrid “it” of the animal also opens a new representational space that dissociates subjectivity from the structures of the symbolic order. Asking if there is “in the history of discourse, indeed of the becoming-literature of discourse, an ancient form of autobiography immune from confession, an account of the self free from any sense of confession,” Derrida understands animals as both the limit for and the grounds of subjectivity and writing.61 His invocation of confession achieves two things: it situates autobiography in its own historical development, and it draws attention to the hermeneutic codes of the genre. Derrida summons a strand in the scholarly account of autobiography that sees the genre originating in “the prodigious Confessions of European history … [that] have formed our culture of subjectivity from Augustine to Rousseau.”62 As Linda Peterson has demonstrated, that form of autobiography establishes a close link between the notion of subjectivity and a particular hermeneutics: “The English autobiography derives from a Protestant tradition of religious introspection, one that is insistently hermeneutic. By ‘hermeneutic,’ I mean first that the autobiography from Bunyan to Gosse has placed in the foreground the act of self-interpretation: the autobiographer’s interpretation of himself and his experience. Second, I mean that English autobiographers have traditionally appropriated their patterns and principles of interpretation from biblical hermeneutics (originally from biblical typology) and that they have done so self-consciously. One might even call autobiography a ‘hermeneutic’ genre.”63 Attentive to this hermeneutic aspect, Derrida is invoking confession to talk about two systems of coding: the divine and the human. In calling for an autobiography beyond confessional autobiography, in imagining a third thing, a tertium quid, above and beyond these parameters of selfhood, Derrida questions our assumption that subjectivity is always human and bound to the symbolic order; he opens up the possibility that the animal participates in subjectivity not just as a developmental stage, but as an ongoing presence.64

Women’s autobiographies are particularly receptive to an exploration of animal presence. As Smith and Watson argue, “Crucially, the writing and theorizing of women’s lives has often occurred in texts that place an emphasis on collective processes while questioning the sovereignty and universality of the solitary self.”65 Mary Mason has suggested that “the self-discovery of female identity seems to acknowledge the real presence and recognition of another consciousness, and the disclosure of female self is linked to the identification of some ‘other.’”66 Engaged in a process of making encounter meaningful and casting that encounter as one based on reciprocity instead of domination, women’s autobiographies provide a fertile ground for exploring the encounter value Haraway associates with our relationship to animals.

For an illustration of the way in which we can then reimagine the site between human and divine codes and the effect this reading has on biopolitical discipline, I turn to an animal autobiography published in 1919 by Wellesley literature professor Katharine Lee Bates, who is best known today as a poet for having written the unofficial U.S. anthem, “America the Beautiful.”67 Bates’s book Sigurd Our Golden Collie (1919) recounts the antics of the dog she adopted with her lover, economics professor Katharine Comen, whom she refers to in the book only as “Joy-of-Life.” Pointing out that they did not choose Sigurd for his pedigree—that is, for his biological features—she insists that she selected the dog because “I want a friend. Njal [Sigurd’s original name] has a soul.” Ascribing to the dog the spirituality usually reserved for human beings in Judeo-Christian theology, she includes the dog in an order that is simultaneously human and divine. In describing Sigurd, she creates a deep sense of reciprocity that stands in defiance of order and discipline. Bates describes how, “now that we realized not only that we had adopted Sigurd but that Sigurd had adopted us, we entered into an ever deepening enjoyment of our dog.” This sense of mutual adoption unsettles the relationship between the members of this family: it is no longer clear that Bates and Comen are the surrogate mothers and Sigurd the adopted child when a reversal of disciplinary roles takes place. Bates repeatedly emphasizes her and Comen’s role as educators and the antidiscipline and counterpedagogy Sigurd brings to their lives: “Be it understood that we were teachers, writers, servants of causes, boards, committees, mere professional women, with too little leisure for the home we loved. Had our hurried days given opportunity for the fine art of mothering, we would have cherished a child instead of a collie, but Sigurd throve on neglect and saved us from turning into plaster images by making light of all our serious concerns. No academic dignities impressed his happy irreverence.” Instead of portraying the home as a prime scene of biopolitical discipline, Bates portrays it as one where affection (“the home we loved”) takes other forms. Although the dog inhabits a childlike role, she insists that the dog himself “throve on neglect” and in turn makes light of his caregivers’ “academic dignities.” The disciplining agency is profoundly unsettled by the dog’s presence, and a reciprocity emerges by which the dog has as much of an impact on the women’s lives as they have on his. In fact, discipline itself gives way to a simulation of discipline: “Sigurd loved nothing better than make-believe discipline.” The women become complicit in this staging of fictive discipline: “Apart from our enjoyment of his crimes, it was difficult to punish him, because his sunny spirit turned every fresh experience into fun.”68

That excess becomes a mark of the text itself when Bates reflects on Sigurd’s relationship to literature:

In pursuance of the theory that the immortal nonsense songs [of Mother Goose] were written by Oliver Goldsmith—this is what is known as Literary Research—I had obtained leave from a Boston librarian, … to take home for comparison with an accumulation of other texts a unique copy…. I carried the book home as carefully as if it had been a nest of humming-bird’s eggs. As I used it that evening at my desk, I propped it up at a fair distance from any possible spatter of ink. Then I … turned to a good-night romp with the Volsung [Sigurd]. We tried several new games. He was a failure as Wolf at the Door, … nor did he shine as Mother Hubbard’s dog…. So we practiced in secret for a few minutes on “a poetic recital” of Hickory Dickory Dock and then came forth to electrify the household. Taking a central seat, I repeated those talismanic syllables, at whose sound Sigurd jumped upon me, climbed up till his forepaws rested on the high top of the chair, in graphic illustration of the way the mouse ran up the clock, emitted an explosive bark when, shifting parts at a sudden pinch, he became for an instant the clock striking one, and then scrambled down with alacrity, a motion picture of the retreating mouse. This was no small intellectual exercise for a collie…. His mental energies had revived by morning and apparently he wanted to review his Hickory Dickory Dock, for he was in my study earlier than I and there … he must needs pick out Mother Goose, even that unique copy de luxe. When I came in, there was Sigurd outstretched on his favorite rug, beside my desk, with the book between his forepaws, ecstatically engaged in chewing off one corner…. We were too keenly concerned over the injury done to remember to punish him, but no further punishment than our obvious distress was needed. Never again would Sigurd touch a book or anything resembling a book. He had discovered, once for all, that he had no taste for literature.69

Bates stages her research as a quest for authorship: she is trying to determine a link between a text and an author—that is, between a literary object and its purported biographical, writerly subject. To establish that link, she pours over textual copies and tries to establish a literary comparison. These exercises are focused on the content of the books, but they also have to contend with the book’s presence as a material, literal object. As an object, the book initially seems markedly different from its content: it shares none of the “immortal” qualities of the texts but is instead as fragile as “a nest of humming-bird’s eggs.” With this reference, Bates juxtaposes symbolic content and biophysical existence. But the text does not uphold as much as repeatedly confound their relationship. She goes on to describe how carefully she treats the book as object and how at the end of the day she turns to an enactment of the literary text—an exercise of giving the text biophysical reality. After a “poetic recital,” Sigurd and Bates enact the story of Hickory Dickory Dock. Bates argues that this was a significant “intellectual exercise” for the dog.70 But she resists inscribing Sigurd in the intellectual framework set by humans. Although he performs the text, he then chews up the book without any sense of its value as an object or as a text. For Sigurd, the book marks pure physical pleasure—he “ecstatically” chews on the cover. Sigurd himself emerges in this account as a real, literal animal who cannot be subsumed to symbolic representation. His chewing the book makes his literal, physical presence palpable—and yet it is a physical presence that Bates achieves by means of literary description. Through this portrayal, she creates for Sigurd an in-between position: he is a literal, physical, real dog who exceeds the parameters of literary and a linguistic representation, and he participates in the realm of the literary enterprise that is her own book. He functions as a transitional object in the sense that he makes possible the distinction between objects and subjects, but he himself does not fall exclusively into either realm.

Bates doubles the autobiographical subject: whereas the prose pieces of her work are written in her own first-person voice, she includes a poem written in Sigurd’s voice.

SIGURD’S MEDIATIONS IN THE CHURCH-PORCH

The gaze of a dog is blind

To splendors of summit and sky,

Ocean and isle,

But never a painter shall find

The beautiful more than I

in my lady’s smile.

The thought of a dog is dim.

Not even a wag he deigns

to the wisest book.

Philosophy dwells for him

In loving the law that reigns

In voice, in look.

The heart of a dog is meek.

He places his utter trust

In a mortal grace,

Contented his God to seek

In a creature framed of dust

With a dreaming face.

The human is our divine.

In the porch of the church, I pray

For a rustling dress,

For those dear, swift steps of thine,

Whose path is my perfect way

Speaking from a liminal position, on the “porch” of the church, the dog cannot enter into aesthetic relationships directly—he cannot see the “splendors of summit and sky.” Instead, his gaze is directed toward a different kind of aesthetic, the encounter with the other. His appreciation of the “beautiful” in “my lady’s smile” exceeds the parameters of human artistic appreciation—he finds more beauty in this encounter than “a painter” would. The second stanza compares this aesthetic appreciation to intellectual knowledge. Although the dog’s thought is “dim” and he lacks interest in “the wisest book,” he experiences an affective relationship to the “voice” and “look” of his beloved. That affective relationship takes on its own capacity to discipline: it is in affect, “in loving,” that he experiences “law.” That law is simultaneously secular and religious for him: he seeks a version of God in the beloved human who becomes his “divine.” Through this relationship, the dog undergoes a transformation: the poem’s first stanza begins with the reference to “a dog” but then shifts to allow the dog to voice his subjectivity in the first person, lyrical “I.”

Speaking in the voice and from the perspective of the dog, the writer of the poem, Bates, is able to express a love that can be sanctified only by crossing species barriers and by reimagining the queer family through the heterosexist iconography of confessional autobiography. Yet the confession here shatters the very parameters of sacred confinement and places us closer to Derrida’s fantasized position of a subjectivity that exceeds the symbolic as well as the divine order. The condemnations of dog love found in Leviticus and enacted at Plymouth Plantation have given way to a different form of “puppy love.” Functioning simultaneously as a figure for closeted love and an icon of queer affection, the dog is both the stand-in for the beloved and the object of a shared affection. The dog is the lover and the beloved, the subject and the object of puppy love. Putting herself in the position of the dog who is gazing at her lover, Bates turns puppy love into a representational scheme that exceeds both the heterosexual matrix and the symbolic order. At one point, Bates recalls that she asked Sigurd, “Whose dog are you, Gold of Ophir?” and that “Sigurd, with an impartial flourish of his tail, lay down exactly between us.”72 Bates initially addresses Sigurd as an object in drawing on his name’s legendary link to the “Gold of Ophir.” But Sigurd defies characterization as a possession. In lying down “exactly between” Bates and Comen, he indicates that he is a third partner in their relationship. Inhabiting a double position as an anthropomorphized subject and a fetishized object, Sigurd exceeds both classifications.

The dog facilitates a newly intimate relationship between Bates and Comen, as the book’s dedication demonstrates: the book is “inscribed to the one whom Sigurd loved best.” Read in the context of the passage describing Sigurd’s impartiality to the two women, that means the book is inscribed to both Bates herself and to Comen. The dog’s love is in fact not preferential—there is no one person whom he loves best—but relational: he loves both Bates and Comen and inserts himself into their relationship. These passages indicate that Sigurd inhabits a position where the “encounter value” between the women and the dog is multiple: each has a relationship to the animal; they jointly share a bond with the dog and newly experience their bond to each other through the dog.

As “things” with which we engage affectively, pets suffer from a double animation—as commodities, as creatures—that situates them at the core of modern biopolitics. In fact, they become exemplary “things” in the sense that they realize the central fantasy of commodity culture, the fantasy that things have a life of their own beyond their relationship with the desiring subject. If object relations structure our sense of subjectivity, then the pet—as the ultimate, doubly animated thing—occupies a physical and figurative position beyond and at the very core of our subjectivity; it both exemplifies and unsettles liberal subject formation. Animal autobiographies make visible structures of biopolitical domination, and they enable us to recognize the mutual dependency of constructions of gender on constructions of species. Resisting the demarcation between subjects and objects, they explore alternative forms of being that hinge on relationships—that is, forms that do not exist a priori as stable categories, but that are themselves subject to change and development. Exploring structures of objectification, they are equally invested in examining how and whether representation functions as an exclusively human practice or as a shared site of cross-species encounter. Although we might object that animal autobiographies tell us nothing about “real” animals, they in fact complicate what we might mean by the terms real and animals. By tying the real to the symbolic, they highlight that our desire for “the real” is itself subject to representation. Nevertheless, they also open up a space for the entry of the “real” animal into our representational schemes. They enable us to recognize that our representational relationship to animals is itself always going to impact how we perceive of the real or the symbolic. Replacing the Cartesian subject with forms of agency based on relationships, animal autobiographies create a space for different forms of becoming. That becoming extends to the development of individual subjectivity, which undergoes perpetual change as its affective relationships shift, and to the emergence of new social possibilities, such as the queer family. It teaches us how to read Millie against the grain of her commercial exploitation and to see puppy love as a means of questioning the heteronormative and anthropocentric subject formation it aims to establish. Animal representations not only inhabit the interstitial site on which the biopolitical depends but also allow us to imagine an outside to the totalizing aspirations of biopower.