In the context of American literary studies, the theoretical discourse of biopolitics has a particular provenance in the issue of slavery. In his landmark 1982 publication Slavery and Social Death: A Comparative Study, Orlando Patterson establishes a division similar to Giorgio Agamben’s distinction between bios and zoē when he argues that slavery functioned as “a substitute for death” and that the slave became a “social nonperson” who had “no socially recognized existence outside of his master.”1 For Patterson, social death was orchestrated via the slave’s “natal alienation” or removal from family structures that would bestow birthrights on him and embed him in a familial and social genealogy. This alienation crucially rested on the master’s “control of symbolic instruments,” which “may be seen as the cultural counterpart to the physical instruments used to control the slave’s body.” Like Agamben, Patterson reads the relationship between the different forms of life that the master and the slave can lay claim to as paradigmatic of the modern social order. Rejecting the argument that slavery is an aberration to the ideals developed by liberalism, he insists: “Slavery is associated not only with the development of advanced economies, but also with the emergence of several of the most profoundly cherished ideals and beliefs in the Western tradition. The idea of freedom and the concept of property were both intimately bound up with the rise of slavery, their very antithesis.”2

This argument resonates with Michel Foucault’s understanding of biopolitics as emerging from liberalism and also marks a significant departure from Agamben’s appropriation of the term biopolitics. Foucault first developed a sustained analysis of biopolitics in part 5 of History of Sexuality, volume 1, and in a series of lectures before the Collège de France that have only recently become available in English translation.3 He demonstrated that biopower emerges in a society where political power no longer limits itself to regulating death through the power of punishment (as Agamben and Patterson suggest) but expands to administering life itself.4 Whereas Agamben grounds his argument about biopolitics in a reading of the law and its relation to sovereignty, Foucault differentiates between sovereignty and biopower. In the newly translated lectures Foucault gave before the Collège de France, he argues that biopower is “absolutely incompatible with relations of sovereignty” in that “this new mechanism of power applies primarily to bodies and what they do rather than to the land and what it produces.”5 He reflects on the shift from sovereignty to biopower as one marked by a turn from “a symbolics of blood to an analytics of sexuality,” though he acknowledges that the passage from one to the other “did not come about … without overlappings, interactions, and echoes,” so that “the preoccupation with blood and the law has for nearly two centuries haunted the administration of sexuality.”6

According to Foucault, the analytics of sexuality hinged on two distinct readings of the body—one that examined the body as a machine regulated by disciplines and another that focused on the species body administered by a system of governmentality. The nexus between the two was sex, which was a means of “access both to the life of the body and the life of the species” and which mediated between the representational structures of the social and the individual.7 For Foucault, a shift from a model of power based on sovereignty to one based on biopower correlates with the differentiation between homo juridicus and homo oeconomicus. He argues that the shift to biopower came with a new understanding of the subject as defined by interests that exceeded the legal definition of subjectivity. In The Birth of Biopolitics, Foucault links this rise of biopower to the rise of liberal capitalism, which he traces back to Locke (on whom I focus in chapter 4) and Hume:

What English empiricism introduces—let’s say, roughly, with Locke—and doubtless for the first time in Western philosophy, is a subject who is not so much defined by his freedom, or by the opposition of soul and body, or by the presence of a source or core of concupiscence marked to a greater or lesser degree by the Fall or sin, but who appears in the form of a subject of individual choices which are both irreducible and non-transferable. What do I mean by irreducible? I will take Hume’s very simple and frequently cited passage, which says: What type of question is it, and what irreducible element can you arrive at when you analyze an individual’s choices and ask why he did one thing rather than another? Well, he says: “You ask someone, ‘Why do you exercise?’ He will reply, ‘I exercise because I desire health.’; You go on to ask him, ‘Why do you desire health?’ He will reply, ‘Because I prefer health to illness.’ Then you go on to ask him, ‘Why do you prefer health to illness?’ He will reply, ‘Because illness is painful and so I don’t want to fall ill.’ And if you ask him why is illness painful, then at that point he will have the right not to answer, because the question has no meaning.” The painful or non-painful nature of the thing is in itself a reason for the choice beyond which you cannot go. The choice between painful and non-painful is a sort of irreducible that does not refer to any judgment, reasoning, or calculation. It is a sort of regressive end point in the analysis. Second, this type of choice is non-transferable.8

Foucault initially develops his notion of homo oeconomicus by a reading of Hume that makes the desire to avoid pain the irreducible measure of self-interest. This emphasis on pain establishes the individual and collective body as the locus of meaning: although the avoidance of pain marks the individual’s irreducible self-interest, it also functions as the baseline for an interest that all members of society share. In reading pain as “a reason” that does not “refer to … reasoning,” Foucault uses “bare life” as the locus for the emergence of a subjectivity in excess of the law. He distinguishes between homo juridicus and homo oeconomicus and argues that “the subject of right and the subject of interest are not governed by the same logic” because the former “is integrated into the system of other subjects of right by a dialectic of the renunciation of his own rights or their transfer to someone else,” whereas the latter “is integrated into the system of which he is a part, into the economic domain, not by a transfer, subtraction, or dialectic of renunciation, but by a dialectic of spontaneous multiplication.”9 That dialectic of spontaneous multiplication is the key mechanism of biopolitics, which exercises its power through the proliferation of knowledge-discourse formations. For Foucault, that discourse remains tied to and grounded in the body: as he points out, “bio-power was without question an indispensable element in the development of capitalism; the latter would not have been possible without the controlled insertion of bodies into the machinery of production and the adjustment of the phenomena of population to economic processes.”10 And yet this second claim also seems to call into question the link between liberal subject formation and biopolitics in the sense that it remains unclear how and whether the “controlled insertion of bodies into the machinery of production” allows for an economic being to emerge as a subject.

Foucault addresses this question by arguing that subject formation is not this social system’s primary aim, but its by-product. The individual is not the origin but “one of the first effects of power.”11 As Patricia Ticineto Clough explains, he argues that in biopolitics the focus is not on the individual body, but on “a politics of population.”12 For Foucault, that population is the human population. But what happens when we engage with the desire to avoid pain more broadly as a desire shared by human beings and animals? What happens when we include animals in concerns over population and politics? After all, the focus on population makes species central to “the mechanisms of the state.”13 Within this economy of production, an understanding of animals as sentient beings opens up the possibility for a larger systemic critique. It becomes possible to read the structures of commoditization as producing homo oeconomicus in an expanded sense as a self-interested subject whose subjectivity is not tied to species boundaries. Both animal husbandry and slavery are premised on the physical exploitation of unfree bodies and on the harnessing of their reproductive capacities for the generation of biological capital. This statement needs to undergo careful reevaluation so as not to generate an unexamined equivalence. What I want to point out for now is that, as Nicole Shukin has recently argued, “the animal sign, not unlike the racial stereotype theorized by Homi Bhabha, is a site of ‘productive ambivalence’ enabling vacillations between economic and symbolic logics of power.”14 Slaves and animals jointly inhabit an ambiguous position in which the shift from discipline to biopolitics is not linear and in which the vectors of individuality and collectivity are negotiated. To understand the challenges and possibilities of that negotiation, I turn to the way nineteenth-century statesman Frederick Douglass reflects on animals as a means to explain and disrupt the relationship between racial stereotypes and “the animal sign.”

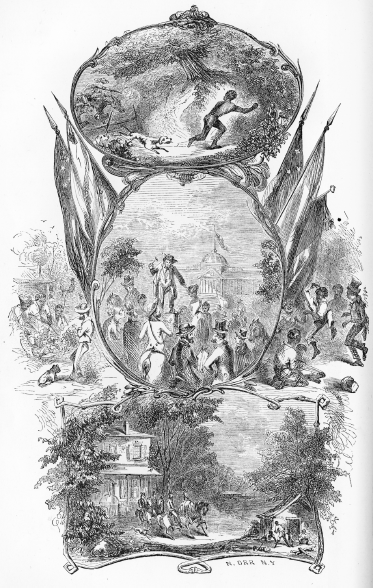

Frederick Douglass’s engagement with animals and animality in relation to American biopolitics is graphically illustrated in his second autobiography, My Bondage and My Freedom, published in 1855. He divides the story of his life into two parts. Each part, “Life as a Slave” and “Life as a Freeman,” is introduced by an elaborate woodcut (figures 2.1 and 2.2) that depicts, as Lisa Brawley points out, “the generic iconography of white nationalism” rather than specific scenes from the book.15 All of the images in the first woodcut portray slavery in relation to animals and animality; the second woodcut defines the freeman’s life by his ability to pursue economic prosperity. The two woodcuts jointly perform a shift from the slave as an object of economic exchange to his participation in the liberal economy. Crucial to that shift is the slave’s relationship to animals and animality. The first woodcut explains slavery as contingent on a complex set of animal metaphors. In “Life as a Slave,” the central vignette’s depiction of an auction puts animals and slaves in an economically analogous position as chattel. The top vignette shows the iconic figure of the runaway slave being hunted by dogs and by men on horses. This vignette hovers above a set of flags to suggest that the runaway slave epitomizes American biopolitics, which uses animals to produce slaves’ animality: working together as “companion species,” men, horses, and dogs turn the runaway slave into prey, an animal barred from affective bonds.

The slave’s animality becomes particularly clear in the one image that, to our modern viewing, does not seem to involve animals—the vignette of slaves dancing, to the right of center. As one of the most sought-after engravers of the time, the woodcut’s creator Nathaniel Orr had made a name for himself by illustrating “many standard, mid-century minstrel productions,”16 and this vignette invokes the minstrel stage. The text makes clear that the image is profoundly engaged with slaves’ animality. Douglass describes how, “freed from all restraint, the slave-boy can be, in his life and conduct, a genuine boy, doing whatever his boyish nature suggests; enacting, by turns, all the strange antics and freaks of horses, dogs, pigs, and barn-door fowls, without in any manner compromising his dignity, or incurring reproach of any sort. He literally runs wild.”17

Experiencing what John Winthrop described as the “natural” liberty of animals, Douglass found himself excluded from “civil or federal” liberty by his animal status.18 But his subtle prose already undercuts Winthrop’s division by creating a verbal resonance between the child who “runs wild” and the runaway who traverses the wild to escape slavery. In describing how the slave child “runs wild,” he links the slave’s “natural liberty” to the runaway slave’s desire for “civil or federal” liberty, thus collapsing the distinctions by redeploying their naturalizing discourse.

Throughout his work, Douglass uses animals and animality not only to reveal the logic of slavery, but to envision alternative forms of subjectivity. In philosophical terms, his work rejects the Aristotelian association of slaves with animals and the Cartesian classification of animals as machines. Instead, he emphasizes animals’ and human beings’ shared sensibility. Put in theoretical terms, Douglass’s writing challenges Agamben’s reading of biopower as an effect of sovereignty by advancing a Foucauldian model that separates the two from each other. By casting the abuse Aunt Hester endures, recounted in Narrative of the Life of Frederick Douglass, as a scene of bestiality, Douglass shows how race and gender are contingent on species and how that contingency reveals them to be social constructs rather than ontological realities. He reads bestiality along the lines I proposed in chapter 1, as the failed attempt to polarize human bios and animal zoē. Instead of establishing the differentiation between the sovereign and the homo sacer, bestiality functions in Douglass’s reading as the site of an emergent liberal subject formation that reveals the animal origins of biopolitics. For Douglass, bestiality is the primal scene of biopower. But the question, then, becomes how or whether it is possible to critique the structures of abjection from the position of animality. Sharing with theorists of affect an understanding of pain as a discursive register, Douglass suggests that bestiality not only founds the juridical subject homo juridicus but produces the interest-bearing subject Foucault calls “homo oeconomicus.”

Hester’s Bondage

To understand how biopower operates, we need to examine how the analogy between slaves and animals functions. The analogy between race and species depends on a specific discourse that revolves around the question how meaning making occurs. In one of the most troubling passages of Democracy in America (1835–1840), Alexis de Tocqueville speculates whether one might not say “that the European is to men of other races what man is to the animals? He makes them serve his convenience, and when he cannot bend them to his will he destroys them. In one blow oppression has deprived the descendants of the Africans of almost all the privileges of humanity.”19 De Tocqueville is summing up some of the most egregiously racist practices and theories of slavery. At the time of his writing, efforts to distinguish blacks from whites culminated in a denial of their shared human origins. Josiah Clark Nott (1804–1873), George Robert Gliddon (1809–1857), Jean Louis Rodolphe Agassiz (1807–1873), and Samuel George Morton (1799–1851) founded the American school of ethnology when they argued that polygenesis, or multiple acts of genesis, had occurred and that blacks were a separate species from white men.20 Although polygenesists generally did not claim outright that blacks were not human, they suggested that blacks had a degree of animality that whites lacked.21

Such racist discourse emerged in response to what Kay Anderson has called a crisis in “human exceptionalism”: because of scientific advances, the category of the human needed to be accounted for in new ways.22 Linguistic capacity had long been considered an exclusive marker of humanity, but new scientific discoveries and philosophical arguments were challenging the notion that language was an absolute dividing line between human beings and animals—it was no longer clear whether language could, as René Descartes had insisted, “be taken as a real specific difference between men and dumb animals.”23 Scientific racists exploited these discoveries by placing slaves in a liminal category that likened them to animals and differentiated both from whites. Arguing that slaves and animals shared the same linguistic capacities, they recoded “human exceptionalism” as white exceptionalism. Dr. Samuel Cartwright (1793–1863) argued that the slave’s anatomical oral structure demonstrated his relationship to animals and his lack of white humanity. Cartwright developed the theory that blacks were “prognathous,” a term he explained to be “derived from pro, before, and gnathos, the jaws, indicating that the muzzle or mouth is anterior to the brain. The lower animals, according to Cuvier, are distinguished from the European and Mongol man by the mouth and face projecting further forward in the profile than the brain.”24 This pre-Darwinian vocabulary motivates a discourse of species to establish categorical yet fungible distinctions that map living beings into hierarchical relation. Granting that blacks and animals shared a limited form of linguistic capacity, Cartwright distinguished the abstract language of slavery’s symbolic order from a physiognomic language produced by and embodied in the “muzzle” of blacks and animals. This association presented African American authors with a special challenge because proving linguistic capacity was insufficient for protesting their condition.

My claim here flies in the face of roughly thirty years of commentary on African American writing that has emphasized the acquisition of language and literacy as a key liberatory tool but that has treated other discursive registers with caution for fear of replicating the reduction of slaves to the conditions of their embodiment. That caution is certainly well advised. The kind of difference posited by Cartwright and others might make one never again want to think of race in conjunction with animals for fear of replicating this denigration and perpetuating what Marjorie Spiegel has referred to as the “dreaded comparison” between human and animal slavery.25 Yet precisely the racist connotations of much animal iconography raise the question why animal imagery recurs with such frequency and urgency in African American writing.

Dwight McBride has recently argued that a “return to the body, to physicality, seems to take us back to a place where one can say something about slave experience that is not just discursive and not just about narration and representational politics.”26 Frederick Douglass recoded the association of slaves with animals that was set up by scientific racism. By engaging with domesticated animals, he critiqued the position of liminal humanity that slaves and animals jointly occupied within the Southern plantocracy’s classificatory blending of Aristotelian ontology and Cartesian epistemology. Abandoning the discourse of rationality and reason that these philosophies had established as the mark of humanity, he drew on a sentimental engagement with pain and sexuality as he redefined the body as the locus of a physical language that exceeded slavery’s symbolic order. Instead of reading the slave as inarticulate zoē, Douglass appropriated the logic of biopower to make sex and affect themselves the sites of liberal subject formation. By depicting instances in which slaves were sexually abused as scenes of bestiality, Douglass revealed slavery to be a discourse constructed in relation to the very thing it negates—the body as a locus of meaning. Douglass raised these questions by invoking a specific practice that tested the relation between bodily narration and engendered subjectivity: bestiality. Although slaves and animals were categorically denied legal standing and gendered subjectivity, bestiality created a nexus between slavery’s symbolic order and the realm of the bodily.

Through the writings of Sigmund Freud and Jacques Lacan, we have come to understand that subjectivity is fractured at the mirror stage and by the entry into the symbolic order. As a consequence, subjectivity is never whole or self-sufficient, but inherently relational: it emerges from the relation between self and other. Underlying their accounts are two fundamental assumptions: (1) that both the self and the other are human; and (2) that humanity is discursive. But what kind of subjectivity emerges where the “other” is an animal or an animalized being, and where discourse is embodied?

Douglass’s first challenge in imagining slave subjectivity consisted in producing gender as a category applicable to slaves. As beings forcefully denied social standing, slaves were hypersexed and ungendered in slavery’s symbolic economy. Treating slaves as hypersexed served slaveholders’ desire to animalize them. In his autobiographies, Douglass describes the analogy slaveholders drew between slave owning and animal husbandry when he points out that Covey bought a slave woman “for a breeder” and when he argues that “the grand aim of slavery, … always and everywhere, is to reduce man to a level with the brute.”27 Emphasizing the reproductive body allowed slave owners to deny slaves’ gendered subjectivity: thinking of slaves as bodies and naturalizing their reproductive role served to remove them from the social construction of gender.

This practice of describing slaves as sexed but not gendered dated back to Aristotle’s justification of slavery, which provided American slavery’s “most enduring” intellectual basis.28 The denial of slaves’ gender established an androcentric and anthropocentric social order. In describing the body politic, Aristotle argues that the male is “superior” to the female and that, in turn, “the female is distinguished by nature from the slave” and the animals.29 He establishes two mutually reinforcing hierarchies: because of the male’s and mankind’s superior status, androcentrism and anthropocentrism go hand in hand. Yet if the male is categorically superior to the female, and the female is categorically superior to the slave, where in this hierarchy would we place male slaves or, for that matter, female slaves?30 Aristotle erases the category of slave gender. By removing masculinity from femininity and from slavery, he implies that the male slave is at best feminized, if he is gendered at all. The ability of anthropocentrism and androcentrism to function in conjunction with each other thus depends on the negation of the slave’s gendered subjectivity.

The negation of slave’s gendered subjectivity makes Hester’s treatment by Colonel Anthony illegible: under slavery’s symbolic order, the scene is not readable as the rape it describes.31 Because rape was defined as “the forcible carnal knowledge of a female against her will and without her consent,” it was inapplicable to slaves, who were denied the very ability to have a will and give consent and hence to exercise “reasonable resistance.”32 Douglass’s answer to this problem shifts the focus from an emphasis on “reasonable resistance” to a reading of pained physicality. As Sabine Sielke has demonstrated, although “the slave system does not recognize the rape of the enslaved,” that rape becomes legible through the “rhetorical analogy between rape and torture.”33

Douglass draws on that analogy with torture in his descriptions of Hester’s abuse at Colonel Anthony’s hands. An act of supposed sexual transgression inaugurates Hester’s punishment: Colonel Anthony whips her for spending time with her boyfriend, Ned Roberts. Colonel Anthony sexualizes and animalizes Hester when he calls her a “d—d b—h.”34 His word choice is crucial: by calling Hester a bitch, he turns her into a female dog and negates her humanity. Yet his reference to Hester as a dog enables Douglass to recode what happens in this scene: unable to portray the violation of a slave woman as a rape under slavery’s symbolic order, Douglass casts this scene in terms that make it legible as another kind of sex crime. By calling Hester a dog, Colonel Anthony shifts from the register of rape to the register of bestiality.35

Bestiality becomes the site from which Douglass can construct slaves’ gender. According to the Oxford English Dictionary, bestiality refers to

1. The nature or qualities of a beast; want of intelligence, irrationality, stupidity, brutality….

2. Indulgence in the instincts of a beast; brutal lust; concr.

a disgusting vice, a beastly practice….

b. Filthy language, obscenity….

3. Unnatural connexion with a beast. Obs. [which the example from the King James Bible associates with “Sodomie”]36

Douglass runs the gamut of these definitions when he describes Hester’s punishment. In accordance with the first definition, Colonel Anthony animalizes her and puts her in the position of a brute. In calling Hester a “d—d b—h,” he engages in “filthy language.” His pleasure in the violence enacted upon Hester marks his own “indulgence in the instincts of a beast,” and his following his “brutal lust” in stripping her and penetrating her flesh with his whip performs an “unnatural connection with a beast.”37 This connection is apparent not only because Hester and Colonel Anthony are associated with animals, but because Douglass thinks of bestiality as a synonym for sodomy: he repeatedly draws attention to the fact that Colonel Anthony attacks Hester’s back, thus invoking the use of his whip as performing an anal penetration.

When Douglass stages the flogging of Aunt Hester, he describes his initiation into the horrors of slavery as a scene of animal abuse. Colonel Anthony treats Hester as mere flesh when he strings her up like a carcass suspended from a meat hook: he “stripped her … leaving her neck, shoulders, and back, entirely naked.”38 The stripping works in two registers here: on the one hand there is the taking away of the clothes, but on the other there is the allusion to his stripping off of her flesh itself through the use of his whip. Devoid of the clothing that physically marks her as human, Hester is reduced to a state of nakedness that is simultaneously animalized and hyperhumanized: because human beings are the only animals that wear clothing, being stripped of clothing is tantamount to being deprived of a marker of humanity; yet, by the same token, because human beings are the only animals that are naked, being stripped also returns Hester to a state of primal humanity.39 Hester inhabits what Louis Marin has called the “clinamen,” a categorical intersection between such seemingly incompatible rubrics as the human and the animal, “verbality and orality, the instinct for self-preservation and the linguistic drive.”40

One way to read this scene is via a logic of shame and victimization to which Hester is subjected, but which Douglass’s reflections on her animalization disrupt in a way that critiques the violence enacted. Two texts are useful in this regard: Alice Kuzniar’s Melancholia’s Dog and Anat Pick’s recent book Creaturely Poetics. Carefully distinguishing between different kinds of shame and in particular pointing out that “empathetic failure can be the result of the denial of shame,” Kuzniar argues that “shame blurs the divide” between human beings and animals “in the very act of constructing it.”41 Douglass’s text carefully maps out a triangulated relationship among Colonel Anthony, Hester, and Douglass himself. Whereas Colonel Anthony represents “empathetic failure,” Douglass demonstrates how a shame that blurs the divide between human beings and animals can be the very basis for, as Kuzniar puts it a kind of “vicarious shame [that] offers the potential for productive social interaction.”42 For Pick, that vicarious shame revolves around a recognition that moves away from an emphasis on victimization—which risks replicating the imbalance inherent in shaming—to an emphasis on shared vulnerability. She argues that such “vulnerability offers a fundamental challenge to liberal humanism, both in terms of the rejection of the notion of rights and in a radical critique of subjectivity.”43 For Pick, the crucial distinction lies in the fact that victimization activates a set of humanitarian sympathies that ultimately support a human-centered understanding of the subject. Vulnerability, in contrast to victimization, produces an intersubjectivity that calls forth attention and enables what Pick describes as an ethical stance toward suffering that does not automatically reinscribe the human as the measure of that suffering. Yet her model of vulnerability departs from Douglass’s concerns in that she imagines attentiveness as something that moves us beyond reading; for Douglass, reading remains central to the enterprise of figuring and critiquing vulnerability.

Douglass explores Hester’s nakedness as a linguistic state. In this animalized yet primal state of humanity, Hester’s words and supplications fail to move her tormentor, and Douglass describes how her voice itself becomes inscribed in her torture: “No words, no tears, no prayers from his gory victim, seemed to move his iron heart from its bloody purpose. The louder she screamed, the harder he whipped, and where the blood ran fastest, there he whipped longest. He would whip her to make her scream, and whip her to make her hush…. It was the most terrible spectacle. I wish I could commit to paper the feelings with which I beheld it.”44 Critics such as John Carlos Rowe have focused on Douglass’s gaze,45 but what interests me is the role that voice and hearing play in his description. Douglass stages his acoustic relation to this scene by pointing out that he has “often been awakened at the dawn of day by the most heart-rending shrieks of an own [that is, biologically related] aunt of mine.”46 His awakening to the horrors of slavery occurs through his relationship to Hester’s voice, and he uses this whipping scene to theorize a slave language that is located in the pained body and that exceeds the symbolic order of slavery.

In this flogging, what Foucault calls the “symbolics of blood and analytics of sexuality” encounter and confound one another, and what emerges, according to Tobias Menely, is a “somatically legible subject.”47 Blood marks both the slave master’s “purpose” and his victim’s actual flesh; it functions as a symbolic as well as a literal marker that refers to the slave master’s ability to control life itself.48 In fact, the tie of the blood to reproduction is further highlighted by Douglass’s use of narrative perspective: he describes himself as a child witnessing this scene and makes himself the offspring of such abuse when he argues that this violation marked his entry into slavery. Having already told us that his father was most likely a slave master, he casts this scene as one that establishes his own figurative as well as literal origins. The scene of bestiality he witnesses functions for him as the primal scene of slavery.49

The excess portrayed here initially seems to mark Hester’s abjection: the more Hester uses her voice, “the louder she screamed,” the more Colonel Anthony controls her physical body, “the harder he whipped.” Through his actions, he tries to control her voice: he whips her “to make her scream” and to “make her hush” and turns her voice into an effect of his own brutal action. He produces her expressions as “prognathous”—that is, as animalistic and lacking in reason.50 Hester’s voice becomes hyperembodied in that it is directly responsive to the pain his whip inflicts. That hyperembodiment serves Colonel Anthony as a justification for his actions: by turning Hester’s language into a bodily effect—an effect of his whipping and her pain—he denies her the disembodied reason and rationality that René Descartes used to distinguish human beings from animals.51 According to Descartes, the “animal … lacks reason.” That lack of reason manifests itself in relation to language: animals “are incapable of arranging various words together and forming an utterance from them in order to make their thoughts understood.”52 Colonel Anthony turns Hester into an instinctive, mechanical animal, responsive to external stimuli but devoid of reason. He negates her individual subjectivity and performs what Foucault refers to as a “controlled insertion of bodies into the machinery of production” that serves “the adjustment of the phenomena of population to economic processes.”53 Colonel Anthony reminds Hester that her physical labor in both the sense of work and the sense of childbirth belongs to him and that he controls her individual body as well as her reproductive and hence biopolitical body.

For Colonel Anthony, Hester’s embodied voice is not a marker of her pained humanity—her very expressions of pain justify his treatment of her in that they mark her as an animal whose suffering is of no account. According to Colonel Anthony but also to our current critical accounts of language, Hester’s pain negates her ability to articulate her humanity. Elaine Scarry has argued that “physical pain does not simply resist language, but actively destroys it” because it is only when “the body is comfortable, when it has ceased to be an obsessive object of perception and concern, that consciousness develops other objects.”54 Scarry’s argument draws on Freud’s and Lacan’s notions that subjectivity depends on a differentiation between subject and object that forms the basis for subjectivity and the entry into the symbolic order of abstract language. In his late work, Jacques Derrida questions the assumption underlying such arguments—that the self and the other are a priori human and linguistically determined. As I discuss more fully in chapter 5, he criticizes Lacan for portraying animals in “the most dogmatically traditional manner, fixed within Cartesian fixity,” and for “refusing the animal language.” Faulting Lacan for depicting the animal “within the imaginary and unable to accede to the symbolic,” he calls into question whether “what calls itself human has the right to rigorously attribute to man, which means therefore to attribute to himself, what he refuses the animal, and whether he can ever possess the pure, rigorous, indivisible concept, as such, of that attribution.”55

Douglass’s answer to this question is a resounding no, especially because the categories of the human and the animal are fungible. Douglass works out his argument by obscuring who inhabits the category of the human and the animal. He depicts Colonel Anthony, in the act of animalizing Hester, in a way that calls into question who the Cartesian animal is in this scene. The colonel is utterly unmoved by Hester’s “words … tears … prayers,” and language itself fails to have an effect on this mechanized being whose actions are guided by his “iron heart” and who is “not a humane slaveholder.”56 By mechanizing Colonel Anthony, Douglass animalizes him: according to Descartes, machines and animals are alike because “the laws of mechanics … are identical with the laws of nature.”57 Rather than indicating that Hester’s utterance is animalistic and incomprehensible, he suggests that the master is animalistic and lacks understanding so that the efficacy of Hester’s expression is lost on him.

Douglass undermines the racism of slavery’s epistemic categorization of animalized humanity by including whites in it. He denies Colonel Anthony the very position of white exceptionalism that his cruelty to Hester is meant to establish. He casts the master in an animalized position and demonstrates Hester’s inherent humanity. His manipulation of Cartesian philosophy points to the fungibility of the human and the animal as ontological categories. Signifyin’, Douglass reverses the racist trope of the “prognathous” slave in his portrayal of Covey: “When he [Covey] spoke, it was from the corner of his mouth, and in a sort of light growl, like a dog, when an attempt is made to take a bone from him.”58 He locates Covey’s animality in the language that is meant to distinguish him from animalized slaves. By drawing on animal similes, he demonstrates that slavery’s symbolic order originates from the animality and physicality that it negates.

However, these strategies run the danger of merely reascribing and not fundamentally critiquing the abjection inherent in the discursive construction of slavery. Instead of focusing on the reversibility of metaphor, Douglass puzzles over recoding the significance of animality as such. To this end, he revisits the body as a site from which to challenge slavery’s symbolic order. When he portrays Hester’s pain and Colonel Anthony’s pleasure, he creates a site of animality by which the body itself matters. By reporting on his own horrified response to the sounds and sights of Hester’s abuse, he develops the possibility of establishing what by the logic of slavery amounts to a “cross-species identification.”59 He accomplishes this goal by shifting the focus from reason to sentiment.

Although we have come to associate this shift with the rise of sentimentality in the nineteenth century, it is already inherent in Aristotle’s discussion of slavery. Although Aristotle dogmatically argues in The Politics that “he is a slave by nature who is capable of belonging to another … and who participates in reason only to the extent of perceiving it, but does not have it,” his writings on the soul undercut the categorical distinctions that he draws here.60 Whereas Descartes justifies his association of animals with machines by separating the soul from the body, Aristotle contends that the soul “cannot be separated from the body.” For Aristotle, plants, animals, and human beings are on a continuum: they all share certain capacities of soul, such as “nutrition, appetency, sensation, locomotion and understanding.” Although Descartes denies animals meaningful sentience, for Aristotle, “it is sensation primarily which constitutes the animal.” Not only is sensation the distinguishing feature of animals, but “where sensation is found, there is pleasure and pain, and that which causes pleasure and pain; and, where these are, there also is desire, desire being appetite for what is pleasurable.”61 Aristotle does not draw the conclusion that human beings and animals are therefore alike, but an emphasis on gradated rather than absolute categories enabled David Hume to conclude that animal actions “proceed from a reasoning, that is not in itself different, nor founded on different principles, from that which appears in human nature.”62 Douglass makes a similar point when he says, “Reason is said to be not the exclusive possession of men. Dogs and elephants are said to possess it.”63 He turns pained animality into the site for a sympathetic identification. He demonstrates in the cruel modulations of Hester’s cries the slave’s animalistic position of—and here I borrow from Emmanuel Lévinas, to whom I turn more fully in a moment—having a voice but of being denied by her tormentor the capacity to have language. Hester’s plight epitomizes the position of slaves and animals as “beings entrapped in their species,” who are, “despite all their vocabulary, beings without language.”64

Douglass describes his own position as a slave author in similar terms. Recounting the division of property that occurred after his master’s death, he says, “I have no language to express the high excitement and deep anxiety which were felt among us poor slaves during this time. Our fate for life was now to be decided. We had no more voice in that decision than the brutes among whom we were ranked. A single word from the white men was enough—against all our wishes, prayers and entreaties.”65 Douglass finds himself without “language” to describe the emotional extremes of his feeling—the “high excitement” and the “deep anxiety.” He likens his state of emotionally intense yet silenced suffering to the experience of “the brutes” among whom slaves were counted. By the logic of slavery, slaves and brutes are qualitatively the same, as Douglass makes clear by setting up a comparison that gives both slaves and brutes equal voice. That voice stands in marked contrast to the language of “white men,” for whom a “single word” suffices to annihilate all verbal expression from slaves.

But Mladen Dolar’s work offers a different reading of what this seeming failure of language means and theorizes voice in a manner that is helpful for understanding the significance of Hester’s screams. Dolar’s reflections on voice are particularly helpful for understanding how Hester’s voice is both embodied and linguistic and how it challenges biopolitics as such. He distinguishes between three different uses of voice: (1) as the vehicle of meaning; (2) as the source of aesthetic appreciation; and (3) as an “object voice” that does not become subservient to either of the other two functions—that is, it does not take second rank to the message or become “an object of fetish relevance.” He argues that “presymbolic uses of the voice,” such as the scream, may seem to be external to structure, but on the contrary epitomize “the signifying gesture precisely by not signifying anything in particular.” That claim enables Dolar to reevaluate the relationship between phoneme and logos and to map it onto and take it beyond the relationship of zoē to bios. Arguing that the “object voice” is “not external to linguistics” and produces a “rupture at the core of self-presence,” he bases these claims on the realization that the voice is “the link which ties the signifier to the body. It indicates that the signifier, however purely logical and differential, must have a point of origin and emission in the body.” Hence, it is the voice that “ties language to the body,” but in a paradoxical way in that the voice belongs to neither—it is not “part of linguistics,” and it is not “part of the body” but instead “floats.” That analysis of the object voice that floats enables Dolar to reread Aristotle’s definition of man as a political animal endowed with speech in distinction from the mere voice of other animals. Dolar argues that “at the bottom of this” distinction between speech and voice, phone and logos, lies “the opposition between two forms of life: zoē and bios.” Rejecting the “partition of voice” that Aristotle thus creates, Dolar argues that voice is “not simply an element external to speech” but “persists” at the core of language, “making it possible and constantly haunting it by the impossibility of symbolizing it.” He clarifies that he does not see this object voice as a precultural state, but as “sustaining and troubling” logos.66

By demonstrating that Hester specifically and slaves in general suffer in spite of or rather because of the inefficacy of their pleas, Douglass creates a means of sentimental identification that tests the limits of discursivity. For Douglass, language—and, in the Narrative, literacy—is not an alternative to embodiment; they go hand in hand and perform the “dialectic of spontaneous multiplication” that Foucault associates with the emergence of biopolitics.67 The body is the locus for a language that precedes and exceeds Lacanian notions of the symbolic order. In Bodies That Matter, Judith Butler makes a similar claim when she points out that “there is an ‘outside’ to what is constructed by discourse, but this is not an absolute ‘outside,’ an ontological thereness that exceeds or counters the boundaries of discourse; as a constitutive ‘outside,’ it is that which can only be thought—when it can—in relation to that discourse, at and as its most tenuous borders.”68

In his treatise Origin of Languages (1771), Johann Gottfried Herder explores those “tenuous borders” when he invokes but departs from Cartesian philosophy’s emphasis on mechanization. He argues that an inquiry into the origin of languages “does not lead to a divine but—quite on the contrary—to an animal origin.” Herder explains that in the sufferer the call for sympathy is not a conscious choice but a natural impulse. It is part of a “mechanics of sentient bodies.” What Herder exactly means by the phrase “mechanics of sentient bodies,” which echoes Descartes, is somewhat enigmatic, but he explains that calling out in pain in search of sympathy is an instinctive, not a reasoned act. The call for sympathy occurs even when no “sympathy from outside” can be expected—it is an act that the sufferer performs regardless of the response he or she will receive. But because such a call “can arouse other beings of equally delicate build”—that is, of an equally sensitized disposition—sympathy also reflects the innate quality of the sympathizer.69

By portraying Hester’s voice as an instinctual response to her pain, Douglass associates her calls with a “mechanics of sentient bodies.” But, for Douglass, these calls demonstrate rather than negate her innate need for sympathy: Hester’s animalism—that is, her instinctive call—forms the linguistic basis on which Douglass and his readers can sympathize with her. Her calls mark her as an interest-bearing subject: as Foucault had suggested in his reading of Hume, homo oeconomicus emerges where an irreducible interest in avoiding pain occurs. That irreducible interest simultaneously marks the individual as a subject yet also makes that subjectivity an effect of power in the sense that it emerges from a commonly held and commonly shared response to suffering. Douglass accomplishes an expansion of that suffering’s significance—no longer merely significant for human beings, such suffering also extends to those beings marked as animals.

For Douglass, sympathizing with those who suffer reveals man’s “best and most interesting side … the side which is better pleased with feeling than reason.”70 By portraying his own horrified reaction, he argues that anyone of “equally delicate build” will differentiate themselves from the unfeeling Colonel Anthony and will respond sympathetically to Hester’s call. In a marked departure from Cartesian rationalism, he motivates the discourse of sentimentality to argue for suffering as the locus (as Foucault would have it)—not the antithesis (as Agamben would insist)—of subjectivity. Douglass describes the effect of Hester’s cries as “heart-rending” and opposes his own affective response to his master’s cruel pleasure in the same scene. For him, the “spectacle” he witnesses is about “the feelings” it awakens in him. He reacts to the scene with a sense of sympathetic identification that validates Hester’s suffering.

By drawing on the body in pain, Douglass establishes a comprehensive understanding of humanity that is deeply relational. As Timothy Morton has pointed out, “‘Humanity’ in the [nineteenth-century] period denotes both the non-sacred (non-Judaeo-Christian) study of culture (for example, classical literature), and sensibility or affection. The play on ‘humane’ is very important in certain contemporary animal rights texts…. Expressions of kindness amongst animals show that ‘humanity’ is a quality possessed equally by all animals, in a sense; but in particular, it links culture (defined as human frailty) to nature. To be humane is to be refined and to accord with nature.”71

Both a natural and a cultivated sympathy, humanity was not what humans had a priori by virtue of being human, but what they acquired through their encounter with animals, as I explain at greater length. Humanity was not a hermetically sealed form of identity, but a form of subjectivity that emerged through an engagement with nonhuman alterity. Deeply relational, humanity marked a relationship that established and exceeded the category of the human; it shifts the focus, in theoretical terms, from biopolitics to zoopolitics, a term I borrow from Nicole Shukin. She has recently taken issue with the idea that “human social life (as the subject of biopolitics) can be abstracted from the lives of nonhuman others (the domain of zoopolitics). Zoopolitics, instead, suggests an inescapable contiguity or bleed between bios and zoē, between a politics of human social life and a politics of animality that extends to other species.”72

This “bleed” between bios and zoē has a particular literary provenance in the beast fable. One of the most popular literary genres of nineteenth-century America, the beast fable “had from its origins functioned as a self-protective mode of communication … by a slave addressing the Master society.”73 Beginning in 1777 with the first American edition of Aesop,74 fables gained popularity in both the Northern and Southern states as didactic texts for children and for language instruction; they were also centrally tied to Locke’s educational philosophy and practices of child rearing and subject formation. Yet Aesop also provided a particularly poignant reference point for African American writers in that he was himself portrayed as being of African descent and enslaved. American editions from 1798 onward often reprinted The Life of Aesop alongside the fables,75 and Aesop (who was a black author—his name was understood to derive from Ethiopia, his place of birth) gained status as a representative man in works such as Samuel Goodrich’s Famous Men of Ancient Times (1843).76

Aesop’s Life begins with an account of his accession to language, specifically to an embodied language that occurs at the “tenuous border” where Butler sees the “ontological thereness” function as a “constitutive outside” to slavery’s symbolic order.77 Originally a deformed slave without linguistic capacity, Aesop finds a means of justifying himself when his master falsely accuses him of stealing figs. By vomiting up the contents of his stomach and occasioning the true perpetrators of the theft to do the same, Aesop manages to produce not “a narrative body, but bodily narration.” That bodily narration forms the origin of the fable in that it creates a “language … [that] will be the supplement of gestures and of the body.”78 This act of bodily narration initiates the fable, which incessantly restages its physical origins and collapses the distinction between the body and discourse. Such bodily narration subverts slavery’s symbolic order. As Louis Marin has argued, the fable operates on the logic of “the production of a body that tells a story, and in so doing, the body inverts the effects of the representational discourse…. [T]his bodily narration deconstructs the verbal story that explicitly claims to be true.”79

This notion that a body can tell a story and that this body need not be human is not limited to the fables of antiquity; it underlies the very notion of literary character that developed in the early modern period, as Bruce Boehrer’s recent work has shown. Arguing that “animal character” is “crucial to the development of notions of literary character in general,” Boehrer suggests that we need to reassess the relevance not only of species, but of species mixing that underwrites “earlier notions of literary personhood.” Explaining that Descartes grants “humanity exclusive access to consciousness via the ability ‘to use words or other signs … to declare our thought to others’” and in the process “creates a new purpose for literary activity—that of drawing and redrawing the species boundary through the elaboration of literary character as defined by the revelation in words of a distinctive personal interiority,” Boehrer points out that earlier writers such as Shakespeare instead had a “pre-Cartesian” understanding of both human–animal relations and literary representation. He sees that alternative understanding “elaborated in the Aristotelian and Theophrastan tradition of nature writing and animal writing that dominated western philosophy from classical times well into the early modern period,”80 a classical tradition that remained central to the curriculum in institutions of American higher education well into the twentieth century and was circulated by Shakespeare’s popularity in the nineteenth-century United States.81 Douglass seems to illustrate Boehrer’s point that “we can understand the notion of character in Aristotle and Theophrastus as a complex of ethical qualities or predispositions … shared by human and nonhuman animals alike to a greater or lesser extent, related to the body in both a causal and an expressive manner, and susceptible to classification just as are the physical qualities that distinguish one class or species of being from another.”82

By engaging with the body—animalized, deprived of language, and in pain—Douglass reminds his readers that writing is itself a physical act when he tells them that his “feet have been so cracked with the frost, that the pen with which I am writing might be laid in the gashes.”83 He insists that the metaphorical body of his slave narrative and his literal body as a slave are inseparable from one another. His language supplements his gestures and his body. Restaging his acoustic relationship to Hester’s cries as a relationship to slave expression more broadly, Douglass draws on this strategy when he writes:

I did not, when a slave, understand the deep meaning of those rude and apparently incoherent songs [of the slave]. I was myself within the circle; so that I neither saw nor heard as those without might see and hear. They told a tale of woe which was then altogether beyond my feeble comprehension; they were tones loud, long, and deep; they breathed the prayer and complaint of souls boiling over with the bitterest anguish. Every tone was a testimony against slavery, and a prayer to God for deliverance from chains. The hearing of those wild notes always depressed my spirit, and filled me with ineffable sadness. I have frequently found myself in tears while hearing them. The mere recurrence of those songs, even now, afflicts me; and while I am writing these lines, an expression of feeling has already found its way down my cheek. To those songs can I trace my first glimmering conception of the dehumanizing character of slavery. I can never get rid of that conception. Those songs still follow me, to deepen my hatred of slavery, and quicken my sympathies for my brethren in bonds…. The songs of the slave represent the sorrows of his heart; and he is relieved by them, only as an aching heart is relieved by its tears.84

Confronted with his inability to “understand” in a reasoned manner what he sees as the “deep meaning” of the slave songs, Douglass develops an alternative, physical mode of expression and comprehension. The songs themselves are “breathed”—that is, they are examples of a physical mode of expression. Their effect on Douglass is physical as well in that the “sadness” they occasion in him expresses itself in the body—in his “tears,” which form an “expression of feeling” where words fail him. By experiencing the limits of abstract language and the power of embodied sentiment, Douglass understands the means by which slavery’s emphasis on rationality and negation of bodily narration operate: because slavery’s symbolic order denies the body’s affective and expressive qualities, it is “dehumanizing.” For Douglass, humanity lies in understanding the physical expression of bodily narration.

Douglass’s Freedom

One of Douglass’s key strategies for achieving the recognition of the relationship between humanity and the body is by rethinking the position of animality in which slavery places him. He understands that animals serve to enact the animalization on which slavery depends, but that animals also disrupt that figuration. In his second autobiography, My Bondage and My Freedom, the engraving representing “life as a slave” (figure 2.1) contains what Michael Chaney has described as a “popular set piece of antislavery iconography, the slavecatcher’s hounds in vicious pursuit of the pitiable runaway.”85 Such pieces typically show a slave about to be attacked by a dog who is charging in advance of a slaveholder on horseback.

Such slave-hunting dogs were apparently commercially profitable, as advertisements for their services attest. Dated January 29, 1856, one such advertisement read: “LOOK OUT. The undersigned would announce to the public generally, that he has a splendid lot of well broke NEGRO DOGS, And will attend at any reasonable distance, to the catching of runaways, at the lowest possible rates. All those having slaves in the woods will do well to address W. D. GILBERT, Franklin, Simpson co. Ky. [N.B. Please post this up in a conspicuous place.]”86 This advertisement reflects the use and the double meaning of animal imagery in the practices and the iconography of slavery. Framed as an announcement to the “public generally,” it defines that public as white and slaveholding. The top portion shows a hand pointing at a sequence of four iconic runaway salves. The layout links the runaway slave depicted in the top portion to the “NEGRO DOGS” of the central text in that the capitalized text functions as a caption for the image of the runaway slave. The advertisement works on two levels. It promotes the hire of dogs for the capture of slaves, but it also labels the runaway slaves as “NEGRO DOGS”: the expression functions as a label for the images, and bestializes the escaped slaves, creating a racial slur that defines them as “NEGRO DOGS.” By the logic of this advertisement, animals are both an instrument for the capture of slaves and an instrument for slaves’ animalization. The advertisement gives the slave a heightened degree of animality in that it portrays him as inhabiting “the woods”—that is, as being wild and removed from civilization. By contrast, the dogs themselves are “well broke”: they have a degree of training that more closely aligns them with the commercial interests of the “public generally” than with the “runaways” whom they will capture for “the lowest possible rates.” Those rates are payable to “the undersigned,” the named person “W. D. Gilbert,” who establishes his subject position by arrogating to himself the means of representation (signing) and economic exchange (payable rates for services rendered). The positions we see enacted here recapitulate the ones Winthrop detailed when he distinguished between “man … beasts and other creatures”: the slave is put in the position of the “other creatures” via his confrontation with the “beasts” and “man.” He is racialized as a “beastlike man,” a wolf-man who is “worse than brute beasts.”

In this advertisement and in the “Life as a Slave” woodcut’s depiction of slave hunting (figure 2.1), the slaveowner dominates the humanized animal (the slave-hunting dog) and the animalized human (the slave). The slave is confronted by both the dog and the rider—by companion species at work. The encounter with companion species places him not only in the position of the animalized human but creates an excess by which he becomes the animalized animal: excluded from human–animal bonds, he figures as the other other of sheer alterity.

This image demonstrates how animals can be instrumentalized to enact state violence and to produce animality. The slave is not only animalized but hyperanimalized in contrast to the dog. A problematic double articulation emerges of what we mean by “animal”: (“the”) animal is the binary opposite of (“the”) human. But the binaries constitutive of the subject break down where “the animal” functions as mediator between the subject and its others. The dog’s presence facilitates the slave’s removal from the symbolic order and from that order’s concomitant forms of legal, social, and verbal subjectivity. It also opens the possibility for a different kind of representational regime to arise. The dog takes on a discursive function in bestializing the slave. But that discursive function collapses the distinctions it is meant to draw between the symbolic, representational, human subject, on the one hand, and the real, nonrepresentational animal, on the other.

How can we theorize the collapse of these distinctions and imagine an alternative biopolitics? Emmanuel Lévinas provides an account that I want to read as imaging an affirmative biopolitics from within the thanatopolitics that Agamben associates with the logic of the camp. In one of the oddest and most complex accounts Lévinas published, “The Name of a Dog, or Natural Rights,” he deconstructs Western attitudes toward animality when he describes his experience in a Nazi detention camp.87 Lévinas and his fellow Jewish detainees found themselves in the position of animalized humans whose treatment at the hands of their captors “stripped us of our human skin” and placed them in a “subhuman” position. Despite the “small inner murmur” that kept affirming their “essence as thinking creatures,” they found themselves “no longer part of the world.”88 Lévinas’s wording here invokes and challenges Martin Heidegger’s argument that “the animal is poor in world” whereas “man is world-forming.”89 Rejecting such ontological difference or, to be more precise, such different relations to ontology, Lévinas indicates that the distinction between human beings and animals is not absolute but relational, that their position in regard to the world is not ontological but situational.90

Describing himself and his fellow detainees as “beings entrapped in their species; despite all their vocabulary, beings without language,” Lévinas explores the implications of that realization by examining the parameters of intelligibility.91 Although David Clark reads Lévinas as ultimately subscribing to the notion that linguistic capacity separates human beings from animals and that only the human subject can bear proper witness,92 the distinction Lévinas draws between vocabulary and language bears further investigation. Mapping Ferdinand de Saussure’s differentiation between parole and langue onto the prisoners and guards, respectively, Lévinas indicates that he and his fellow detainees were capable of individual expression but were barred from having that expression signified in the structural contexts they inhabited. Expanding on this point, he writes that “racism is not a biological concept; anti-Semitism is the archetype of all internment. Social aggression, itself, merely imitates this model. It shuts people away in a class, deprives them of expression and condemns them to being ‘signifiers without a signified’ and from there to violence and fighting.”93

Arguing that racism’s ontology is discursively constructed, Lévinas demonstrates that metaphor (the use of archetypal referents) creates metamorphic positions. Instead of language being an absolute human capacity, Lévinas argues that it is possible for human beings to be deprived “of expression” and relegated to a position of nonsignification. That position of nonsignification places the detainee in the literal position of animality, where he meets with “violence.”

Lévinas does not merely document that violence but also posits an alternative model of communication—something along the lines of what Alice Kuzniar calls “interspecial communication.”94 If Lévinas himself did not have any experience with German guard dogs, surely he was aware by the time of his writing in 1975 that they were used in detention camps. Yet Lévinas invokes the dog in a different capacity, as a creature that does not do the bidding of state interpellation and violence, but one that performs a different kind of subject formation by giving the body itself a discursive register with which to critique the model of abjection practiced by the Nazis. Lévinas describes the detainees’ encounter with a dog whom they named Bobby who visited the camp: “He would appear at morning assembly and was waiting for us as we returned, jumping up and down and barking in delight. For him, there was no doubt that we were men.” Introducing a dog early in his piece as “someone who disrupts society’s games (or Society itself),” Lévinas finds his subjectivity affirmed—or rather newly constructed—in the encounter with Bobby.95 While the prisoners endured forced labor, their relationship to Bobby occurred outside the camp’s structures of domination and beyond the working relationship Haraway associates with companion species. However, this figure also seems to reinscribe some of the central notions of subjectivity: as a free agent, the dog seems to occupy the position of the humanized animal in the species grid, and through his acts of seeming volition to reaffirm the humanity of the animalized human. It is not clear that the animal is able to function here in a role as an animal other.96

Developing as his basic philosophical premise the notion that the face-to-face encounter with the other makes the human human, Lévinas struggles with the question whether animals can be included in his model of relational, ethical subjectivity. In an interview he gave in 1986, he responds directly to the question whether animals have a face. Affirming that “one cannot entirely refuse the face of an animal,” he ambiguously argues that his “entire philosophy” hinges on the idea that for human beings “there is something more important than my life, and that is the life of the other. That is unreasonable. Man is an unreasonable animal.” At the very moment of differentiation, then, Lévinas concludes indecisively: he argues for man’s exceptional ethical capacity yet calls man an “animal.” Rejecting an inscription of human beings in a model of animality, he asserts that they are in the exceptional position of creatures for whom the maxim does not hold that “the aim of being is being itself.”97 But his description of Bobby belies the exceptionalism he claims to endorse: risking his life to seek human companionship (Bobby was eventually “chased … away” by the “sentinels”), Bobby engaged in the unreasonable act that for Lévinas defines ethical subjectivity.

Recognizing such emotional intersubjectivity—and the privileged role that the body plays in it—enables us to expand our understanding of discursive registers. Lévinas talks about the guards being epistemologically and ontologically confused—unlike the dog Bobby, they “doubt[ed] that we were men.” Dogs have a different kind of knowledge that is located in their own bodies: they know by “barking in delight” that the prisoners are men. As a different kind of social knowledge, “barking in delight” becomes Lévinas’s countermodel to the symbolic order: the dog’s recognition of a fellow being undid other human beings’ withholding of that recognition. Lévinas’s encounter with the dog marks his humanity yet at the same time makes humanity subject to recognition by animals. In the relationship with animals, on the liminal ground of humanized animality and animalized humanity, a form of subjectivity emerges that is relational and removed from the violence of the symbolic order. That subjectivity is not human as much as it is humane: it is in his sympathetic engagement with the animal that Lévinas renounces the violence inherent in the symbolic order. It is in the dog’s “barking in delight” that Lévinas sees himself as a man. In the encounter between the detained Lévinas and the dog Bobby, we see suspended the differentiation between subjects and nonsubjects that underlies the symbolic order and its concomitant forms of representation.

Douglass stages a similar encounter, but his use of humor in doing so enables him to avoid the pitfall of instrumentalizing animals that Lévinas falls into. In the relationship between the human being and the animal, Douglass imagines subjectivity to become recognizable and meaningful. He makes the body the basis for a relational subjectivity that he locates in the encounter between human beings and animals. He often sounds as though he were categorically distinguishing human beings from animals. Although he says that animals have language and reason, he insists that only men have the capacity for imagination. For instance, in his address “Pictures,” he argues that “man is the only picture-making animal in the world.” However, his phrasing in making these distinctions is revealing: even though he categorically differentiates “picture-making” human beings from animals, he inscribes both in the category of the “animal.” He describes in “Farewell to the British People” (1847) how slavery’s symbolic order denies him subjectivity, but he also indicates that the relationship to animals makes the recognition of his subjectivity possible:

Why, sir, the Americans do not know that I am a man. They talk of me as a box of goods; they speak of me in connexion with sheep, horses, and cattle. But here, how different! Why, sir, the very dogs of old England know that I am a man! (Cheers) I was in Beckenham for a few days, and while at a meeting there, a dog actually came up to the platform, put his paws on the front of it, and gave me a smile of recognition as a man. (Laughter) The Americans would do well to learn wisdom upon this subject from the very dogs of Old England; for these animals, by instinct, know that I am a man; but the Americans somehow or other do not seem to have attained to the same degree of knowledge.98

Douglass talks about Americans being epistemologically and ontologically confused—unlike the dogs of England, they do not “know” that Douglass is a “man.” Dogs have a different kind of knowledge that is located in their own bodies: they know by “instinct” that Douglass is a man.99 Limited entirely to a gestural register of expression, “with neither ethics nor logos,” says Lévinas, “the dog will attest to the dignity of its person. This is what the friend of man means. There is a transcendence in the animal!”100 The dog’s bodily knowledge enables his recognition of Douglass’s embodied voice as being different from “sheep, horses, and cattle.” Instinct becomes Douglass’s countermodel for social knowledge: he laments that the Americans have not “attained to the same degree of knowledge” as the dog acting on his instinct. Douglass’s encounter with the dog marks his humanity and at the same time makes humanity subject to recognition by the animal. In the relationship with the animal, on the liminal ground of humanized animality and animalized humanity, a form of subjectivity emerges that is relational and removed from the violence of slavery. It is in his sympathetic engagement with the animal that Douglass reverses the violence inherent in slavery’s symbolic order.

As a rewriting of American biopower, this scene is tremendously powerful: understanding how the instrumentalization of animals produces slave’s animality, Douglass envisions an affective relationship that makes the encounter with an animal the site of an affirmative subjectivity. In allowing himself to encounter an animal affectively, he places himself in the position of the liberal subject that emerges from the relationship with animals. In Lévinas, that relationship is coded hierarchically in that the dog is not admitted to the same kind of subjectivity that he enables and produces. However, Douglass’s use of humor allows him to envision at least the possibility of a radically different kind of subjectivity, one that—like his descriptions of Hester—reads animality as producing a subjectivity premised on alterity. In eliciting “laughter” from his audience, he is creating a verbal expression that is nonlinguistic. Producing in his listeners a response that is not symbolic but instead vocal, bodily, aural, he places them in the same position as the dog who, in Lévinas, barks with delight and who, in Douglass, smiles. Turning Covey’s “light growl” and the guard dogs’ interpellation into the happy barking of the smiling dog, Douglass does not abandon the discourse of animality as much as recode it. He places his audience in the dog’s position in that the smile of recognition now becomes reflected and refracted in their laughter. Turning animality into a shared but affirmative biopolitical site, he opens the possibility for producing a subjectivity that collapses the binaries between “the human” and “the animal” and that generates alternative subject-discourse formations.

In this chapter, I have examined what possibilities arise for an alternative discourse when Douglass appropriates the logic of biopower to make sex and affect themselves the sites of subject formation by crossing species lines. Turning to the specifically American context of slavery that makes bestiality a biopolitical site, this chapter has demonstrated how the abuses of bestiality for Douglass function as a way to imagine alternative modes of representation that shift our attention from the subject of rights to the subject of interest. By depicting instances in which slaves are sexually abused as scenes of bestiality, Douglass reveals slavery to be a discourse constructed in relation to the very thing it negates: the body as a locus of meaning. Denied human identity under slavery’s symbolic order, Douglass makes the body the basis for a relational subjectivity that he locates in the encounter between human beings and animals. He suggests that the wrongs of slavery occur outside the realm of reasoned discourse and are visited upon the suffering body. By validating that suffering even when—or, rather, because—it seems to occur beyond reason or language, he treats the pained body as the locus of an embodied language that bespeaks the cruelty endemic to slavery’s symbolic order. By shifting from the homo juridicus to homo oeconomicus, he invests the body with discursive capacity and challenges us to rethink the parameters of subjectivity—a challenge that the next chapter takes up in relation to the work of Edgar Allan Poe. This turn from homo juridicus to homo oeconomicus raises the larger question how affect and commodification impact liberal subject formation. I have begun to address that question in this chapter but also develop it further in chapters 4 and 5, when I examine how the scene of bestiality gets rewritten as one of “puppy love” with the rise of sentimentalism in the nineteenth century and its permutations in the twentieth century.