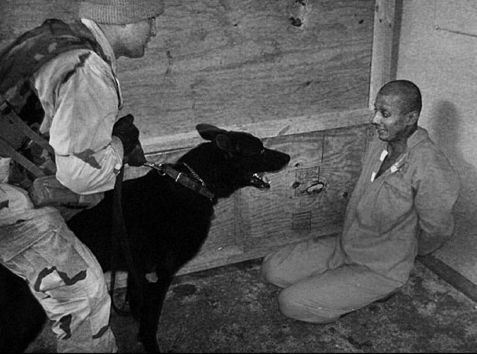

On March 21, 2006, a U.S. Army dog handler was convicted of charges brought against him in conjunction with the abuse of prisoners at Abu Ghraib in Iraq. Sergeant Michael J. Smith, age twenty-four, was found guilty of six out of thirteen indictments. Smith expressed remorse for only one of those convictions, his conviction for indecency. That conviction stemmed from Smith’s “directing his dog to lick peanut butter off the genitals of a male [American] soldier and the breasts of a female [American] soldier.” Smith said: “It was foolish, stupid and juvenile. There is nothing I could do to take it back. If I could, I would.”1 Smith expressed remorse for having his dog engage in sexual acts with his fellow soldiers. What made this one charge among the many for which he was convicted legible to Smith as an offense? Smith apologized for the one act that involved other Americans and for an offense that situates his case within a practice that is foundational to the social order itself—the practice of constructing subjectivity by dividing human beings from animals. His reference to his acts as “juvenile” marks them as a rite of passage into adult maturity; his apology itself performs a learning process by which he came to recognize subjects (those fellow beings who have legal standing in the courts and interpersonal recognition from acts such as apologies) by distinguishing them from animals (those nonsubjects that lack legal and discursive representation). There was no mention of the Iraqi detainees or of the dog.

My pointing out that second absence will seem ludicrous in and of itself, and my linking the dog with the detainees might come across as offensive: of course Smith did not apologize to the dog. After all, we reserve rights and apologies exclusively for human beings because only they count as subjects in our system of language-based political representation. Representational subjectivity sets human beings apart from all other living creatures—it lies at the core of our secular notion that human beings are special, that there is such a thing as human exceptionalism. I borrow the term human exceptionalism from Kay Anderson, who uses it to describe the belief that each human being is fundamentally different from all animals.2 That belief has its strategic purposes in allowing us to conceptualize human rights as a category of legal, ethical, and symbolic representation that extends subjectivity beyond state boundaries. But I worry that human exceptionalism actually enables the abuses it critiques because it sets up a dichotomy between human beings who have representational subjectivity and animals who lack it.3 Smith’s apology exemplifies this problem. He defined representational subjectivity ontologically and tautologically: one has rights by virtue of being human, and one is human by virtue of having rights. By that definition, animals lack rights because they are animals, but those who lack rights, such as the abused detainees, are all too easily animalized. Human and animal are categories that lay claim to utter ontological fixity, but are highly fungible. Any creature who is not deemed human becomes subject to abuse without recourse to standards that would mark such an injury as wrong: Smith never apologized to the detainees he brutalized; like the dog, they remained nonsubjects to him, beyond recognition. Human exceptionalism ultimately does not protect human beings from abjection but enables abuse by creating a position of animality that is structurally opposed to humanity.

What complicates the matter is the fact that animality and humanity are neither dichotomous nor separable, but deeply inscribed in one another. Animality is not simply outside of the social order and its mechanisms of subjectification; it is foundational to it. In current critical discourse, the meaning of animality is still being worked out, but Dominick LaCapra provides a useful working definition when he describes animality as two things: the structural opposite of humanity and a quality that animals and humans share.4 What interests me is the question how these positions get worked out in the uneven terrain between the figurative and the literal—that is, in the terrain that I am trying to conceptualize as “animal representations.” In the example with which I began and that I develop more fully toward the end of this chapter, the positions of humanity and animality multiply because we are not dealing simply with binaries (human/animal), but with a triangulated relationship between the soldier, the guard dog, and the detainee or fellow soldier. That triangulation places the categories of humanity and animality, of “the” human and “the” animal, in shifting relation to one another, where those shifts are a mechanism of biopower but also generate possibilities for disrupting its operation.

By reexamining Michel Foucault’s notion of biopower as a key mechanism of sovereignty in the state of exception, Giorgio Agamben has made a similar argument—which I draw on for its ability to explain the violence and structure of biopower but which I also critique for its limited understanding of biopower as merely violent and structural. Agamben has argued that an abject position of “bare life” stands outside religious and social law and functions as the disavowed counterpart to the equally unlawful position of the sovereign.5 He identifies “bare life” with the figure of the homo sacer, the “sacred man” who “may be killed and yet not sacrificed” under Roman law, and likens that figure to the “wolf-man” of Germanic law.6 He identifies that wolf-man as “the man who has been banned from the city” but who remains “in the collective unconscious as a hybrid of human and animal, divided between the forest and the city.”7 Although Agamben avails himself of psychoanalytic vocabulary when he refers to the “unconscious” and is gender specific in his accounts of “man,” his discussion by and large remains devoid of any analysis that would explain the role this wolf-man’s sexual presence plays for the formation of gendered subjectivity. Agamben produces a version of Aristotle that replicates some of the latter’s exclusions of women from the polis without reflecting on the complexities that exclusion raises for an account of the sovereign’s other(s). He does, however, reflect on the wolf-man’s relation to discourse formation, specifically the challenge the wolf-man poses for imagining alternative forms of representation: he argues that the wolf-man “is not a piece of animal nature without any relation to law and the city. It is, rather, a threshold of indistinction and of passage between animal and man, physis and nomos, exclusion and inclusion.”8 For Agamben, this threshold marks the zone in which the sovereign can exercise power. But the same can be said for domesticated animals (especially pets and particularly dogs)—that they inhabit a “threshold of indistinction” in which they function as both animal and man (not just in the form of man’s best friend, but via the association of sodomy with bestiality that I discuss later) and where we see the emergent and collapsed distinction between physis and nomos. A dog’s ability to inhabit the role of the wolf-man maps the drama of sovereignty onto the mundane territory of pet keeping, where affect determines subject positions. Because domesticated animals such as dogs can take on the function of the wolf-man, there is a doubling of the hybridized figure that impacts the “collective unconscious” in that it produces an effect of uncanny recognition between human beings and animals. Agamben’s analysis ultimately privileges the human side of that hybridity in insisting on the human origins of the wolf-man and in reading (to quote the title of one of his other books) “the open,” the space of indeterminacy between human beings and animals, as a (if not “the”) human condition, thereby negating animal subjectivity. He sees the wolf-man as the result of a particular political relationship and relegates animals to a separate category, that of an “animal nature without any relation to law and the city.”9 This claim is problematic in that it runs the risk of reproducing the category it aims to critique—namely, the category of zoē. However, I suggest that it also opens the possibility for alternative subject and discourse formations in that it posits an elsewhere, an outside to the totalizing aspirations of biopower. In this chapter, I attempt to understand the double function of the wolf-man—the animalized human and the humanized animal (terms I develop later)—as creating a position of animality that underwrites and unsettles the modern formation of representational subjectivity.10 What becomes clear in the process is, in Derrida’s key intervention into biopolitical theory, “not that political man is still animal but that the animal is already political.”11

To develop this analysis, I begin with an originary moment for the development of modern biopower and the mechanisms of differentiation: the criminalization of bestiality.12 In the commentary on Abu Ghraib, virtually all critics have ignored this dimension of the abuse. One case in point is Jasbir Puar’s work, which provides a complex and provocative reading of the gender politics displayed in the abuse but glosses over the role of animals and animality. Writing that the abuse “vividly reveals that sexuality constitutes a central and crucial component of the machinic assemblage that is American patriotism,” Puar outlines how “the use of sexuality—in this case, to physically punish and humiliate—is not tangential, unusual, or reflective of an extreme case, especially given continuities between representational, legislative, and consumerist practices.” Recognizing the role that depicting detainees as animalistic plays for the abuse, Puar quotes testimony by one of the prisoner guards at Abu Ghraib:

“I saw two naked detainees, one masturbating to another kneeling with its mouth open…. I saw [Staff Sergeant] Frederick walking towards me, and he said, ‘Look what these animals do when you leave them alone for two seconds.’ I heard PFC England shout out, ‘He’s getting hard.’” Note how the mouth of the Iraqi prisoner, the one in fact kneeling in the submissible position, is referred to not as “his” or “hers,” but “its.” The use of the word “animals” signals both the cause of the torture and its effect. Identity is performatively constituted by the very evidence—here, getting a hard-on—that is said to be its results. (Because you are an animal you got a hard-on; because you got a hard-on you are an animal).13

Important as these insights are, Puar separates her reading of sexed animality from the actual animals that were present and instrumentalized as part of the abuse, surprisingly writing that “not all the torture was labeled or understood as sexual, and thus the odd acts—threatening dogs, for example—need to retain their idiosyncrasy.” Outlining how “state of exception discourses doubly foster claims to exceptionalism,” Puar explains that these practices cast “the violence of the United States” as “an exceptional event, antithetical to Americanness.” By extension, she argues, “U.S. subjects emerge as morally, culturally, and politically exceptional through the production of the victims as repressed, barbaric, closed, uncouth, even homophobic, grounding claims of sexual exceptionalism that hinge on the normativization of certain US. feminist and homosexual subjects.”14 Compelling as this account is for recognizing some of the regulatory mechanisms in place and for demonstrating the centrality of sexuality for the formation of subjectivities, it is complicit with human exceptionalism in that it takes animals out of the picture. My point here is not simply that animals are being overlooked, but that overlooking animals leaves us with an incomplete understanding of the way biopower operates in constructing subjectivity.

I take seriously the charges brought against Smith for involving his dog in sexual acts. The criminalization of bestiality provides an instance in which the homo sacer and the sovereign directly encounter one another via the figure of the pet. In that encounter, we see suspended the differentiation between subjects and nonsubjects that underlies the symbolic order and its concomitant forms of representation. The regulation of sexual relations between species marks a moment where symbolic representation is disrupted and emergent, where the metaphoric and the metamorphic conjoin and become differentiated, where the categories of the human subject and the animal object come into play. To flesh out that claim requires rethinking representation itself. In this chapter, I begin my book’s larger enterprise of developing the concept of animal representation, by which I mean a nexus between the symbolic depiction, physical presence, and political significance that one model of modernity wants to spread out over different species, but that merges and emerges in human–animal relations.

Alfonso Lingis and Midas Dekkers have argued for the pervasiveness of bestiality by insisting that it underlies all acts of love: in making love even to a fellow human, we are always encountering an animal or animalized other.15 Useful as their arguments may be for allowing us to reflect on the alterity of love, they do not help us to see the power differential at play in acts of bestiality, nor do they enable us to understand fully the complex literal and symbolic meanings of bestiality.16 Bestiality and its criminalization offer a model for the emergence of subjectivity in the biopolitical state. According to Richard Bulliet, the encounter with animals is a hallmark of “domestic” society from which our “postdomestic” society has become removed. He differentiates the two terms on the basis of people’s encounter with animals: whereas human beings used to come in contact with domestic animals on a daily basis, they now have no relationship to animals other than as pets and never encounter the animals who produce their food and clothing as well as their medicine and cosmetics. Paying particular attention to children’s development, he argues that in domestic society children were exposed regularly to animal sex in the sense of witnessing animals having sex with each other and of witnessing acts of bestiality. Although “domestic societies around the world have generally had a scornful attitude toward engaging in sexual intercourse with animals,” he quotes Havelock Ellis to justify his claim that these societies “have also recognized that it happens—and not all that infrequently.” Bulliet points out that these acts of bestiality primarily involve men and that they are in that sense gendered. In postdomestic societies, the actual intercourse between men and animals “appears to be rare,” but with the decline in literal acts of bestiality comes a shift “to luridly fantasizing about it.” In fact, Bulliet argues, an intensification takes place: “By hiding the animal sex that in the domestic era was an inescapable component of life, and thereby keeping children ‘innocent’ until their first adolescent encounters with pornographic images, postdomesticity encourages expressions of sexuality that put fantasy in the place of carnal reality.”17 The criminalization of bestiality functions as a transitional moment from domestic to postdomestic society and its concomitant literal and figurative relationships to animal sex: it inaugurates the regulation of the affective relationship with animals.18 Whereas that regulation initially occurs via the law, the law ultimately functions as a mode of textuality that conjoins with other forms of representation to play out the production of biopolitical subjectivity via punitive and affective means that straddle the relationship between the body and discourse.

Scholars have long recognized the connection between the body and discourse. Focusing on the early American period to which I turn in a moment, Janet Moore Lindman and Michele Lise Tarter, for instance, write:

Bodies are maps for reading the past through lived experience, metaphorical expression, and precepts of representation. They tell us about … formations of subjectivity and identity. Yet, as living, breathing, ingesting, performing entities, bodies afford a specificity of lived experience that has been devalued and all but erased in western philosophical traditions…. Cultural reevaluation of the human frame reveals the historical importance of sentience and materiality in early American societies, and consequently leads us to a more complete story of the past. Bodies … are never unmediated; they are related but not reducible to cultural concepts of differentiation, identity, status and power…. Encompassing both the physical and the symbolic, it [the body] is, therefore, fully enmeshed in the social relations of power.19

Useful as this formulation is for thinking about the recalcitrant meanings of materiality, it is also symptomatic of the way in which scholars theorize “bodies” as synonymous with “the human frame.” That association is in many ways perplexing: If the critical force of turning to the body has stemmed from, in Judith Butler’s formulation, the fact that “thinking the body as constructed demands a rethinking of the meaning of construction itself,” why does some version of “the human” underwrite that enterprise, even when that enterprise is—in a formulation that aligns Butler with Agamben—attentive to “a domain of unthinkable, abject, unlivable bodies”?20 If we shift our attention to bodies, and especially if we consider the body as producing a “movement of boundaries, a movement of boundary itself,” and a “resistance to fixing the subject,”21 why maintain this implicit focus on “the human”? What happens when we include animal bodies in our considerations? What would it mean to examine “a radical rearticulation of the symbolic horizon in which bodies come to matter at all”22 if we allow for those bodies to be other than human?

In this chapter, I inquire into the biopolitical function of animal representations in two seemingly disparate historical and geographical moments: the criminalization of bestiality at Plymouth Plantation and the bestialization of prisoners at Abu Ghraib.23 Taking seriously the commentators who have related the abuses at Abu Ghraib to a larger register of American racial (Patricia Williams) and gendered (Susan Sontag) iconography,24 I argue that we must understand the crucial role that animal representations play for the production and negation of biopolitical subjectivity as and at the founding of a legal order premised on colonial violence. I understand bestiality through its historical definition as a synonym for sodomy and as the performance of human–animal sexual relations. As these uses imply, the term bestiality refers to a sexual act in which one party of the encounter is an animal or is portrayed as an animal (that is, the way sex between men is characterized as sodomy in ways that are undifferentiated from bestiality). This blurring of the literal and the figurative in the conjoint discourse around sodomy and bestiality interests me in that it opens the question how we are to understand the relationship between bodies and subjectivity to begin with. In the historic documents I discuss, bestiality refers to a specific sex act, but also to a supposedly innate quality that the parties involved in that act share—that is, the term beastly functions as a synonym for the current critical term animality in that both describe a quality that humans and animals share and where there is a concerted discussion of what that means for understanding subjectivity. Although I retain the use of the term bestiality for sex acts that cross species lines, I adopt the term animality to discuss the structural and representational position that bestiality produces. Recent scholarship has tried to differentiate between “animal” and “animality” by charting a distinction between nonhuman animals and a quality they share with human beings.25 In my use of the term, animality collapses the distinctions between humans and animals but also calls into question how we distinguish between species as an ontological or epistemological—and performative—category. Animality is a floating signifier, and one of my chief interests in this chapter lies in charting its mobility, the way in which it moves between, as LaCapra explains, functioning as the structural opposite of humanity and serving as a quality that animals and humans share.26 Animality refers to the structural position that is the opposite of humanity. Because a human being can also inhabit this structural position, animality is not limited to literal animals. Although the opposition between human and animal is meant literally, it functions figuratively: in using the term animality, I refer to the fact that a human being can occupy “the animal’s” structural position. The fact that animals or animalized human beings can inhabit the position of animality unsettles the distinction it is meant to establish and collapses the differentiation between the literal and the figurative.

This “collapse” is immanent to the historical materials I discuss. Anne Kibbey argues that “the threats and acts of physical harm, the symbolism of physical identity, and the rationale of iconoclastic violence against people as images—all these aspects of prejudice were informed by a concept of figuration that was qualitatively different from what we usually take ‘figurative’ to mean in literary thought.” She explains that

Puritanism relied on the classical concept of figura, an idea that initially had nothing to do with language. In its earliest usage figura meant a dynamic material shape, and often a living corporeal shape such as the figure of a face or a human body. This ancient concept of figuration has a modern equivalent in our sense of the human bodily form or appearance as a “figure.” For the Puritans, the concept of figura was a means of interpreting the human shape, whether as artistic image or as living form, and it comprehended both nonviolent and violent interpretations of human beings. Among its most important qualities, the classic concept of figura as it meant material shape defied the conventional metaphoric opposition between “figurative” and “literal.” The configuration or shape was simply there, and its defining property was the dynamic materiality of its form.27

This association between the figurative and the literal might also explain why not only physical acts of but also jokes about—that is, figurative acts of—bestiality were punishable in the past.28 Bestiality is more than a peculiar historic remnant in the operations of American biopower; it is the origin of modern biopolitical subject formation, and, as such, it confounds our understandings of that modernity. As Jens Rydström has argued, “Bestiality was never incorporated into modernity.”29 I want to read that statement so as to suggest that bestiality operates as a paradigmatic instance of animal representation—that is, as a practice where the separation of representation as a political or cultural enterprise breaks down. A contemporary theorization that ties the notion of the figura to a way of rethinking modernity emerges in Richard Nash’s “notion of a ‘material/semiotic actor,’” which he borrows “from those contributions to science studies (notably those of Donna Haraway and Bruno Latour) that seek a productive analysis of nature/culture that does not originate with an a priori separation of the human and the world.”30 Not only does the figurative intrude on the literal, but the literal also intrudes on the figurative in that biopower instrumentalizes animals to differentiate between the structural positions of humanity and animality. Animals such as guard dogs can inhabit the position of animality, but they can also take on a mediating function between the structural position of humanity and the position of animality. I locate the birth of the biopolitical subject in that mediation.

“Man with Beasts and Other Creatures”: Bestiality and the Birth of American Biopolitics

A peculiar epidemic swept through the New England colonies in the 1640s.31 Several young men were brought to court and convicted on charges of bestiality, leading Governors John Winthrop and William Bradford as well as a number of other prominent men to fear that a larger pattern was emerging in the young colonies.32 Given the historical record, this concern seems to have been exaggerated: Roger Thompson has argued that cases of bestiality were “statistically insignificant” in local courts.33 Why, then, did these isolated cases give rise to such concern, and why did the crime “not to be named” generate such sustained discussion? The small number of cases brought to trial belies the frequency with which acts of bestiality occurred. Bestiality seems “to have been wide-spread,” but the broader population regarded the practice as “commonplace” and resisted its criminalization.34 The discrepancy between the frequency with which bestiality occurred and with which it was brought to trial points to an “underlying disjunction between official ideology and popular responses”35 and suggests that the contact between human beings and animals was contested ground for biopower’s operation. Because early Americans understood bestiality as a specific sex act and as the reflection of innate qualities, its criminalization was part of a mechanism to distinguish natural from civic order and served to legislate that distinction. The distinction hinged on a specific understanding of ethnic subjectivity that depicted racial differences as species distinctions. At stake in the criminalization of bestiality was the production of gendered subjectivity and ethnic citizenship.

In analyses of sexed and gendered subjectivity, bestiality has remained absent as a meaningful concept in its own right and has garnered attention mainly because of its association with sodomy—that is, with same-sex acts. The association between bestiality and sodomy emerged in the European Middle Ages and produced an intensification of the punishments for such transgression. Tracing the “history of bestiality” from prehistory to the present, Hani Miletski argues that a change occurred in the European Middle Ages, whereby “equating homosexuality with bestiality not only increased the penalty, but it communicated a change in the way people looked at animals. Instead of being an irrelevant object, the animal became a participant as in the equivalent of a homosexual encounter, and it became important to kill the animal, in order to erase any memory of the act.”36

Jonathan Ned Katz and Jonathan Goldberg have argued that the colonial persecution of bestiality was a founding moment for the oppression of gays, that it established a precedent for subsequent laws denying the right to practice sodomy and that it revealed “the tacit limits to the American version of liberalism.”37 They point out that in the historic record the terms bestiality and sodomy often function as synonyms for one another. The authors themselves do not differentiate between the terms in the sense that they do not reflect on human–animal sex but read references to bestiality as animalizing gay men and dehumanizing same-sex encounters.

Work has recently emerged that tries to understand not only the links that the historic record established between bestiality and sodomy, but also the way they became differentiated from one another. In his comprehensive historical survey of the Swedish regulation of sexual practices, Jens Rydström provides a profound reassessment of the history of sexuality as one that must include bestiality.38 Charting the development “from sinner to citizen, namely, the transition from the sodomitic to the homosexual paradigm,” Rydström argues that “in Sweden, as elsewhere in the Christian world, same-sex sexuality and sexual intercourse with animals were conceptually connected as two aspects of the sodomitic sin, or the crime against nature.” Although the archival record is particularly rich (bestiality was explicitly outlawed “in all Swedish law books, from the thirteenth century until 1944”), scholarly discussion on the topic has been remarkably absent: “not many authors have discussed the phenomenon of bestiality, fewer still [the exceptions Rydström names are John Murrin and William Monter] have compared it to same-sex sexuality, and no one has discussed it in a twentieth-century context.” He argues that “in order to fully understand what lies behind some of the peculiarities of modern discourse on homosexuality, it is necessary to analyze its connection to bestiality and the factors that lay behind the disappearance of this connection from the collective mind in the middle of the twentieth century. Also, the disappearance of bestiality, as compared to the rise of homosexuality, provides a challenging example of the contingency of sexual categories.” Rydström’s focus ultimately points to the “normative mechanisms that increasingly establish heterosexuality as a dominant structure and punish … sexual behavior outside heterosexuality.” Yet there is a surprising blind spot in Rydström’s study. Although he carefully charts the way in which “the discourses concerning male same-sex sexuality have since antiquity been structured around difference” such as age and class, he on the one hand reads bestiality as undifferentiated when he points to “the conceptual conflation of sex with animals and same-sex sexuality which was made by the historical actors under study” but on the other hand says that “the analysis of bestiality does not concentrate on the difference between the sexual partners. The difference between man and animal can be considered as given. (The similarity would perhaps be more interesting to think about).” That parenthetical caveat seems important to consider: What would it mean to think of the difference between man and animal as not simply a given and how might we make this difference a subject of analysis? The persistence and focus of Swedish law on bestiality would certainly warrant these questions: “Of the ‘three sodomitic sins,’ only bestiality had been continuously and explicitly outlawed since the medieval laws,” giving bestiality a special status among the prohibited sexual acts with which it is associated. Swedish laws “did not outlaw same-sex sexuality for many hundreds of years, but only bestiality,” thus giving this practice particular status among the “crimes against society”—that is, a “crime against property and a crime against morality.”39

Defined by penetration, bestiality was closely tied to masculinity, but because that masculinity was not associated exclusively with human beings, bestiality has particularly interesting meanings in relation to women and lesbianism. Katz documents a legal case brought in Georgia in 1939 that tested whether women could be convicted of sodomy for same-sex acts. The judge ruled on the “question whether the crime of sodomy, as defined by our law, can be accomplished between two women,” finding that “by Code … sodomy is defined as ‘the carnal knowledge and connection against the order of nature, by man with man, or in the same unnatural manner with woman.’ Wharton, in his Criminal Law … lays down the rule that ‘the crime of sodomy proper can not be accomplished between two women, though the crime of bestiality may be.’ We have no reason to believe that our law-makers in defining the crime of sodomy intended to give it any different meaning.”40 As Katz documents, sodomy was a male phenomenon in that it required an act of penetration, but bestiality could include women:

A strict penetrative concept did, curiously, allow colonial lawmakers to imagine intercourse between women and animals (male animals were apparently inferred). It is ironic that colonial legislators, who hardly ever prohibited carnal relations between women (and never explicitly) did often explicitly penalize copulation of women with beasts. That the intercourse of women and (male) animals received much explicit statutory recognition indicates the social dominance of a strict penetrative concept. When illicit intercourse was defined primarily by reference to a male organ it was of only secondary import whether that virile member was attached to man or beast. The colonists’ concern about the interpenetration of humans and beasts was no doubt linked to their belief that interspecies intercourse could result in the birth of part-human, part-bestial creature. And their concern about human–animal contacts was also no doubt linked to the temptations and probable prevalence of bestiality in an agricultural economy commonly utilizing animals for many other services.41

The persecution of women for bestiality often took the form of witch trials. The relationship between witches and animals was threefold: (1) witches were said to attack the livestock of others; (2) they were seen as transforming themselves into animals; and (3) they had animals as familiars. Their relationship to animals thus placed the animals on a scale from pure object (livestock that they attacked) to an impermissible subjectivity. The boundary between the human and the animal was blurred, as John Putnam Demos points out: “There is, in sum, a kind of paradox here. Prevailing belief ascribed to witches a particular animus against infants and small children. Moreover, a parallel belief declared that witches might directly intervene in the nursing process—for example, by causing acute soreness in the breasts … or by inhibiting lactation itself…. Yet witches, too, had small creatures under their personal care. They, too, undertook to nurture and protect such creatures, and even to ‘give them suck.’ The witch with her imp was a figure—albeit a distorted one—for human motherhood.”42 As I discuss at greater length in subsequent chapters, the relationship between human beings and animals thus involves issues of gendering that revolve precisely around the ambiguous status of animals as children and in turn of children as animals, which the focus on lactation demonstrates.

Rydström’s study includes many theorizations that make his work useful beyond Sweden’s historic archive. In Of Plymouth Plantation 1620–1647, one of the American urtexts (which is also a key nineteenth-century text by virtue of the full manuscript’s recovery in 1856), William Bradford describes the trial of sixteen-year-old Thomas Granger. Accused of a “horrible case of bestiality,” Granger was convicted of having had sexual intercourse with a mare, a cow, two goats, five sheep, two calves, and a turkey.43

For a transgression to count as bestiality, a specific definition of sex—namely, intercourse—had to be met.44 Moreover, that intercourse had to be established discursively: although the birth of deformed animals with features resembling the defendant sometimes gave rise to suspicions of bestiality, to meet the standards of proof the judicial system required either a confession or the testimony of two independent witnesses.45 This requirement interestingly expanded the practice of bestiality from the specific act of penetration to a larger social context. In mapping different kinds of bestiality, Gieri Bolliger and Antoine F. Goetschel distinguish between five “sexual acts between human beings and animals”: “genital acts, oral–genital acts, masturbation, ‘frotteruism’ (rubbing of genitalia or the entire body on the animal), and voyeurism (observation by third parties during sexual interactions with animals).”46 The requirements for legal trial proliferated acts of bestiality in that they relied not only on the physical act of penetration but also on voyeurism. Giving equal weight to verbal testimony (the confession) and eyewitnesses, the criminalization of bestiality inscribed a public quality in the act. In Granger’s case, such standards of public testimony were evidently met: following the punishment for such offences dictated by Leviticus 20.15, the animals were put to death in front of Granger before he himself was executed.47 Considering the animal carcasses to be unclean, the settlers destroyed them and did not use the meat or skins they could have yielded.48

Elaborating on the reasons for such harsh punishment in relation to another case, Samuel Danforth explained a few years later in The Cry of Sodom Enquired Into (1674): “Bestiality, or Buggery, [occurs] when any prostitute themselves to a Beast. This is an accursed thing … it turneth a man into a bruit Beast. He that joyneth himself to a Beast, is one flesh with a Beast…. This horrid wickedness pollutes the very Beast, and makes it more unclean and beastly than it was, and unworthy to live amongst Beasts, and therefore the Lord to show his detestation of such Vilany, hath appointed the Beast it self to be slain.”49 This passage suggests that the line between human beings and animals is absolute, but that it is possible for individuals to move from one category to the other: bestiality “turneth a man into a bruit Beast.”50 Sex determines an individual’s standing and functions as a source of transformation, but bestiality does not simply produce a conversion from one state of being to another: it creates a joint corporeality by which man becomes “one flesh with a Beast,” a hybridity we might associate with the wolf-man. This hybridity affects not only man, but also the beast, which it “pollutes” and makes “more unclean and beastly” than it was. The beast goes from merely being an animal to having a highly charged quality of animality—beastliness in historical parlance—that the sexual relationship with a human being generates. The language escalates into the hysterical—the beast verbally proliferates, and its degree of beastliness increases. This notion that beastliness is not an absolute but has varying degrees reflects a deep uneasiness about the distinction between human beings and animals. By criminalizing a crossing of the species barrier, the law tries to establish and naturalize ontological categories that it simultaneously reveals to be highly unstable.

The law does not simply apply to a subject that exists a priori; it constructs the humanity of that subject (or his lack thereof).51 As Susan Stabile has demonstrated, “In the eighteenth century, biological sex was understood as a fluid category indivisible into the binaries of male and female. ‘To be a man or a woman was to hold a social rank, a place in society, to assume a cultural role,’ argues historian Thomas Lacleur, ‘not to be organically one or the other of two incommensurable sexes.’ The discourse of evangelical religion thus configured sex as a sociological rather than ontological category.”52 The law also configured species as a social category: by demanding that human beings ought not to engage in sexual acts with animals, it regulated the boundary between human beings and animals. This act of prohibition defined the difference between human beings and animals as simultaneously absolute and fungible.53 Although it maintained that human beings and animals are absolutely different from one another and therefore ought not copulate, it acknowledged that such copulation occurs. As John Canup has argued, “There can be no more vivid testimony to the contemporary belief in the possibility of dissolving the boundaries between humans and animals through sexual communication.”54 In the colonial case, sex itself took on the power to be ontologically transformative: it removed Granger’s humanity and attributed to him an animality that he shared with his victims. That transformation occurred via Granger’s relationship to the law. By engaging in a sexual encounter with an animal, he forfeited his rights and the law’s protections; he inhabited the same relation to the law as the animals with whom he was sexually involved and suffered the same death as they. Excluded from legal subjectivity, animals are nevertheless subject to the law’s punitive reach. That punitive reach defines those condemned to death by law as animals: animals function as a category of legal death from which the law temporarily and conditionally exempts human beings. Granger witnessed the death of the animals with whom he had had intercourse as a metonymic act in which his own execution was inscribed. In losing his legal subjectivity, his right to life and liberty, Granger became subject to the law, victim to its punitive powers, and inhabited the position of animality from which the law temporarily exempted those to whom it granted legal subjectivity.

Far from being a peripheral legal matter, these cases of bestiality point us to the pivotal role that animal sex plays as the primal scene of biopolitics, through which individual subjectivity and collective social structures develop.55 What these legal cases reveal about gender-discourse formation has recently sparked a debate among scholars of early American literature. Richard Godbeer has documented that three categories were crucial for Puritan distinctions between different sexual transgressions: marital status, sex, and species. Sexual transgression figured into an attempt to understand and produce the category of “the natural” itself, an endeavor that was complicated by the understanding that since the fall from grace, the natural had become a morally compromised category.56 Godbeer argues that sexual sin was a “manifestation of human depravity” and emphasizes the spiritual dimension by claiming that “the basic issue was moral rather than sexual orientation.” He documents that Puritan theology integrated acts of sexual transgression “into a larger moral drama” by reading them as the result of the “innate corruption of fallen humanity.”57

Whereas Godbeer reads sexuality as standing in service to a discourse of morality, David Halperin insists that we see the emergence of sexual identities in these documents. Rereading Foucault’s famous distinction between the sodomite and the homosexual, Halperin argues that “the current doctrine that holds that sexual acts were unconnected to sexual identities in European discourses before the nineteenth century is mistaken in at least two different respects. First, sexual acts could be interpreted as representative components of an individual’s sexual morphology. Second, sexual acts could be interpreted as representative expressions of an individual’s sexual subjectivity.”58 Bestiality participated in the gendering of subjectivity.59 Because penetration had to occur, bestiality was tied to masculinity, though that masculinity did not have to be human.60 Bestiality was thus a key concern when it came to the production of sex and gender.

Mapping the production of gender onto the formation of social structures, Sigmund Freud explores the link between bestiality and masculinity in Totem and Taboo. Collapsing the Puritan distinction between natural and unnatural sexual transgressions, he links bestiality and incest to explain the disavowed foundations of heteronormative patriarchy. On the surface, the prohibition against bestiality and the prohibition against incest may seem to follow diametrically opposed logics—the first being a prohibition against straying too far from the range of sexually acceptable partners, the second being a warning against not straying far enough. Certainly, critical discourse dating back to Aquinas has argued for and upheld such distinctions and mapped the two into differential relationship with one another.61 However, Freud departs from this line of interpretation. Arguing that a totem is “as a rule an animal” that “is the common ancestor of the clan,” he points to an act of cross-species miscegenation that inaugurates human social formation. He asks: “How … did they [“primitive” men] come to make the fact of their being descended from one animal or another the basis of their social obligations and, as we shall see presently, of their sexual restrictions?” Observing that “almost every place where we find totems we also find a law against persons of the same totem having sexual relations with one another and consequently against their marrying,” Freud speculates that “the most ancient and important taboo prohibitions are the two basic laws of totemism: not to kill the totem animal and to avoid sexual intercourse with members of the totem clan of the opposite sex. These, then, must be the oldest and most powerful of human desires.” Freud further explores this conjunction between the desire to kill the totem animal and to have intercourse with members of the totem clan: seemingly digressing into a discussion of children’s animal phobias (a topic that also preoccupied him elsewhere—for instance, in the case of the “Wolf-Man” that he documented in History of Infantile Neurosis), he concludes that children “displace some of their feelings [of fear] from their father on to an animal.” The payoff of this analysis for Freud lies in his comparison between children and “primitive” men, which enables him to suggest that “the totem animal is in reality a substitute for the father,” that is, a kind of wolf-man.62 Freud explains early social formation as contingent on the figure of the animal and its ability to regulate heteronormative social relations; the totem animal both predates and originates the formation of the social and symbolic order.63 As Kalpana Shesadri-Crooks has concluded, “We must read the murder of the father as the moment not only of the institution of the prohibitions against murder and incest, but of the very notion of the human, of the separation between human and animal, and of their interrelation.”64

The subjectivity that was being negotiated in colonial trials of bestiality is then directly tied to what Judith Butler has called the “heterosexual matrix,” which she also refers to as the “matrix of gender” and the “matrix of power.”65 Butler argues that compulsory heterosexuality defines who counts as a subject. At stake is not just the “strategic aim of maintaining gender within its binary frame,” but the fact that this aim itself serves to “found and consolidate the subject.”66 As concerned as she is about the effects that these mechanisms of power have on subject formation, she ultimately shares with the order she critiques an assumption that subjectivity is always already human. Taking Butler’s argument a step further by challenging that assumption, we can recognize that the subject produced by compulsory heterosexuality under the rules of patriarchy is doubly man and mankind—there is a dual operation here of androcentrism and anthropocentrism: when it comes to bestiality, the discourse of species and the construction of gender conjoin to create a notion of subjectivity that mandates physical behavior for the construction of the human. Butler has described physical behavior not just in terms of normative heterosexuality, but also in terms of gender performance—that is, as the daily acts through which we conform to social expectations of how our bodies ought to signify.67 Useful as her argument is for deontologizing gender, it runs the risk of reontologizing species in that it is implicitly humans and humans only who perform gender and participate in this social construct. The exclusion of animals from the matrix of gender relegates them to a realm of nonperformative embodiment that is hypersexualized precisely because it is denied gendered status and figured as nonrepresentational physicality.

In the context of early American literature, the stakes of charting the precise location of bestiality on a map of moral and criminal standards lay in determining the relation between subjectivity and governmentality. Michael Warner has documented that “the Puritan rhetoric of Sodom had begun as a language about polity and discipline” and that it was “linked primarily to the topic of national judgment.”68 Puritan theologians explicitly linked the discourse of species to the discourse of liberty. John Winthrop warned in 1645 against forms of “liberty” that made men “grow more evil, and in time to be worse than brute beasts.” He argued that there

is a twofold liberty, natural (I mean as our nature is now corrupt) and civil or federal. The first is common to man with beasts and other creatures. By this, man, as he stands in relation to man simply, hath liberty to do what he lists; it is a liberty to evil as well as to good. This liberty is incompatible and inconsistent with authority, and cannot endure the least restraint of the most just authority. The exercise and maintaining of this liberty makes men grow evil, and in time to be worse than brute beasts; omnes sumus licentia deteriores. This is that great enemy of truth and peace, that wild beast, which all the ordinances of God are bent against, to restrain and subdue it. The other kind of liberty I call civil or federal, it may also be termed moral, in reference to the covenant between God and man, in the moral law, and the politic covenants and constitutions, amongst men themselves. This liberty is the proper end and object of authority, and cannot subsist without it; and it is a liberty to that only which is good, just, and honest. This liberty you are to stand for, with the hazard (not only of your goods, but) of your lives, if need be. Whatsoever crosseth this, is not authority, but a distemper thereof. This liberty is maintained and exercised in a way of subjection to authority; it is of the same kind of liberty wherewith Christ hath made us free.69

In Agamben’s interpretation of biopower, it operates by distinguishing “natural” (zoē) from “civil” (bios) liberty. Animals participate in the natural form of liberty, but Winthrop banishes them from the civil form; that is, he creates a distinction between animals’ bare physiological life (zoē) and human beings’ political life (bios). That bios is fragile and contingent and has life itself for its object and its means: those included in civil liberty need to “hazard” their “lives” to uphold the social order that they participate in. The liberty they achieve is that of “subjection to authority,” which the reference to Christ makes both spiritual and bodily. Although this distinction seems to invoke the Great Chain of Being, in which differences are mapped hierarchically, Winthrop concerns himself with the mobility rather than the fixity of these different positions. The exercise of natural liberty does not merely liken men to beasts but makes them “worse than brute beasts.”70 For Winthrop, that excess is both external and internal to men. The improper exercise of liberty exposes the “wild beast”—that is, an internal quality brought out by the improper exercise of liberty. According to this naturalizing discourse, beastliness is an internal quality that man shares with animals and other creatures; beastliness is also a relation to the law. It is only in relation to the proper kind of liberty—namely, the subjection to authority—that this beastlike quality is restrained and that a full humanization occurs. The subjection to a specific kind of authority produces both liberty and the human subject.

Yet the binary division Winthrop establishes between man and animal turns out to be gradated: not only does he differentiate between men and beasts, but he also creates an enigmatic category of “other creatures.” For Winthrop, this category is both external and internal. He produces a complicated doubling by which the beast figures as a way of demarcating racial distinction but also represents a quality of the self. He establishes a racial hierarchy by which he differentiates the white settlers from the animals and indigenous peoples they encounter.71 His distinction is based on species as well as ethnicity; his strange specification invokes Native Americans, as an earlier passage makes clear.72 He reflects on members leaving the colony and thereby “depriving themselves of … those civil liberties which they enjoyed there” by going “into a wilderness, where are nothing but wild beasts and beastlike men.”73 The distinction between “beasts” and “beastlike men” functions similarly to the distinction between “beasts” and “other creatures.” For Winthrop, Native Americans inhabit a middle ground between men and beasts—that is, a category of similitude in which they are “beastlike” despite being “men.” They function as wolf-men who mark the threshold of subjectivity in its relation to the biopolitical state. As “beastlike men,” they take on the role of the homo sacer or wolf-man in relation to the colony. The prohibitions against bestiality thus also regulate sexual intercourse with “beastlike” Native Americans.74

But Winthrop also includes the settlers themselves in his reference to “other creatures”: their exercise of natural liberty makes them “worse than brute beasts” and creates an animality in excess of the natural liberty that nonhuman animals and racial others exercise. Although “other creatures” are removed from the social order, they are also an immanent other that calls forth technologies of self-discipline.

That was certainly Cotton Mather’s view when he wrote: “We are all of us compounded of those two things, the Man and the Beast.”75 For Mather, the wolf-man is the biopolitical subject per se. Beasts take on the function of the other than human—that is, as the binary opposite of the human. They mark an ultimate alterity and evoke fears of miscegenation.76 Mather’s and Winthrop’s accounts double the role of the wolf-man. The wolf-man takes on a specific ethnic and racial dimension in that Native Americans function as these figures of hybridity. They stand outside the exercise of civil power but are also the objects that civil power tries to control: the wolf-man also marks an internal condition in that the colonists do not just regulate the hybridity of others but are themselves hybrid.

In Cotton Mather’s description of Thomas Hooker, the relationship to animals in general and dogs in particular becomes a complex image not only of self-discipline, but also of discipline more generally. Mather describes Hooker as “a Man of a Cholerick Disposition … yet he had ordinarily as much Government of his Choler as a Man has of a Mastiff dog in a chain; he could let out his Dog, and pull in his Dog, as he pleased.”77 Punning on the terms collar and choler, Mather describes Hooker’s “choler” as something that he himself exercised “government” over. That kind of “government” is a technology both of self-mastery and of mastering alterity. Mather creates a simile that likens the “government of his choler” to the control “a Man has of a Mastiff dog in a chain.”78 But the simile breaks down in his use of the pun. The “choler” functions as a “collar,” a disciplining mechanism that collapses the distinction between man and mastiff, master and servant; the binaries the simile sets up break down via the pun and are modulated not by their binary opposition to each other but by the practice of controlling pleasure—of exercising liberty (“let out”) and restraint (“pull in”) precisely “as he pleased.” This passage then conjoins and confounds government and pleasure around the establishment and collapse of binary oppositions between the human and the animal, where the animal serves as an intermediary that modulates the binaries it deconstructs.

This double articulation of animality relocates the drama of sovereignty on the terrain of human–animal relationships. As Canup argues, just as bestiality “blurred the inner boundary between man and beast, so it also weakened the comfortable external dichotomy of civilization and wilderness. The occurrence of bestiality within the area of English culture suggested that while the colonists might conquer the wilderness as a physical presence, its moral influences were less easy to combat. And if the curse of wilderness had taken root in the colonists and their culture, no scapegoat could possibly draw off all the corruption they would generate.”79

That inability to externalize the beast fully and remove it from man meant that bestiality presented a particular challenge to the biopolitical order. If in fact it is not possible to dichotomize and excise alterity, then the thanatological drift of biopolitics is disrupted in that the very practice that nominally produces bare life is also tied to the subject’s internal structures, especially because those structures are sexed and gendered. That opens up the possibility for an “affirmative biopolitics” by which animals and animality are not only a mechanism of biopolitical control, but also the locus for alternative subject and discourse formations. As Timothy Campbell explains, Roberto Esposito argues that we can only reverse the thanatopolitical dimensions of biopolitics by “developing another semantics in which no fundamental norm exists from which the others can be derived.”80 Such new semantics hinge on rereading subjectivity. Abandoning our notion of the individual, argues Timothy Campbell in his explication of Esposito’s work, will shift our attention “to producing a multiplicity of norms within the sphere of law.” The result will be that “norms for individuals will give way to individualizing norms that respect the fact that the human body ‘lives in an infinite series of relations with the bodies of others,’” in which “the radical toleration of life-forms that epitomizes Esposito’s reading of contemporary biopolitics is therefore based on the conviction that every life is inscribed in bios.”81 But the questions become how those life forms violently removed from bios are or remain legible as bios and what kinds of relationship one can enter into with them when confronted with the violence of sovereign power.

From Rights to Rites: Reading Outside the Law

The engagement with animals is a particularly fecund site for thinking through these issues because reading zoē as bios forms the locus of animal studies’ resistance against thanatopolitics. In the 1798 work Introduction to the Principles of Morals and Legislation, the text that has retrospectively become foundational to the branch of animal studies that emerged out of the engagement with questions of legality and rights, Jeremy Bentham worries that

the day has been, I grieve to say in many places it is not yet past, in which the greater part of the species, under the denomination of slaves, have been treated by the law exactly upon the same footing, as, in England for example, the inferior races of animals are still. The day may come, when the rest of the animal creation may acquire those rights which never could have been withholden from them but by the hand of tyranny. The French have already discovered that the blackness of the skin is no reason why a human being should be abandoned without redress to the caprice of a tormentor. It may come one day to be recognized, that the number of legs, the villosity of the skin, or the termination of the os sacrum, are reasons equally insufficient for abandoning a sensitive being to the same fate. What else is it that should trace the insuperable line? Is it the faculty of reason, or, perhaps, the faculty of discourse? But a full-grown horse or dog, is beyond comparison a more rational, as well as a more conversible animal, than an infant of a day, or a week, or even a month, old. But suppose the case were otherwise, what would it avail? The question is not, Can they reason? Nor, Can they talk? But, Can they suffer?82

Taking issue with the law’s limitations, Bentham calls for nothing short of a political and semantic revolution. Through his references to the recent French overthrow of “tyranny,” he envisions a utopian state in which the wrongful withholding of rights from animals and animalized beings will be redressed. He challenges Christian theologians’ belief in a Great Chain of Being that justifies the submission of “animal creation” to abusive practices of dominion on the basis of a hierarchical distinction between “inferior races” and superior species. He also rejects rationalist philosophers’ notion that human beings and animals are fundamentally different from one another and that an absolute “faculty of reason” and “faculty of discourse” separate all human beings from all animals. He points out that some animals are “more rational” and “more conversible” than some human beings. Recognizing that such comparative terms still place animals and those likened to them at a disadvantage, he redefines the very grounds of rights bearing when he argues that subjectivity can be located in feeling—that is, in the physical capacity to suffer.83 Pitting participation in the symbolic order (the capacity to talk) against an embodied experience (the ability to suffer), Bentham calls attention to the power that figuration has to create a nonfigurative category of abjection into which the physically “other” can be lumped.84 Like Esposito, he calls for another semantics when he insists that the body itself has a legibility and meaning in excess of the symbolic order.

This semantics of suffering, however, risks reproducing the essentialism it sets out to critique. Peter Singer self-consciously modeled his call for “animal liberation” on Bentham’s claims.85 Grounding his appeal for animal liberation in the belief that subjectivity and responsibility emerge where there is actual or possible suffering, he argues that the interests of human beings do not necessarily outweigh those of animals and that both need to be measured against the greater good. By using suffering as a measure for legal and ethical subjectivity, he locates ethics in naturalism: as Cary Wolfe has pointed out, Singer anchors “the contingency of the social contract” on “noncontingent natural ground.” To avoid such essentialism, Wolfe insists that we shift our attention from animal rights to what he calls “animal rites.” Taking humanism as a starting point for the development of what Esposito characterizes as a multiplicity of norms, Wolfe argues that we need to expand our categories for subjectivity and rights bearing across species boundaries when certain criteria are met: “When our generally agreed-on markers for ethical consideration are observed in species other than Homo Sapiens [sic], we are obliged to take them into account equally and to respect them accordingly.”86 This approach hopes to deconstruct the humanism from which it departs without resorting to essentialist categories.87 But, as always, the devil is in the details.

Rejecting ontological claims, Donna Haraway argues in her most recent publications that we need to understand subjectivity as a relational category that emerges in the interaction between human beings and companion animals such as dogs. Eroding the very ground for human exceptionalism, she states that “dogs are about the inescapable, contradictory story of relationships—co-constitutive relationships in which none of the partners pre-exist the relating, and the relating is never done once and for all.”88

Gilles Deleuze and Félix Guattari have taken issue with the sentimental investment that people have in “individuated animals,” especially pets, claiming that they take on an “Oedipal” status and are the subject of “narcissistic contemplation.”89 Haraway tries to redress these problems by insisting that love is about alterity. Like Esposito, she shifts our attention from notions of individual subjectivity as an a priori given to an understanding of subjectivity as a relational category that emerges in the encounter between different beings. Trying to replace the violent abuses of bestiality with mutually affirming “acts of love,” Haraway imagines a subjectivity that emerges from and generates an ever-widening social fabric, a global politics based on affect: she argues that “acts of love like training … breed acts of love like caring about and for other concatenated, emergent worlds.”90 Conceived in that way, love for an animal can become the prototype for loving others as others. Loving others calls into question one’s own subjectivity precisely because we are never sure if that love will be reciprocated. Loving an animal is the ultimate kind of such other-love because it opens us up to the alterity of the other and the possibility that the reciprocity we hope for will not follow. Such love is not the expression of a self-replicating or self-sustaining emotion, but, quite the contrary, it makes emotion the very hallmark of subjectivity. It is in the loving encounter with animals that the possibility emerges for a subjectivity that is deeply relational and nonviolent.

Compelling as I find Haraway’s argument, I worry about three things. First, her notion of “love” already seems to depend on an idealization of affection as the antidote to violence. Second, her identification of companion species relies on a literalism by which a dog is always a dog. Yet from its inception in Bentham’s writing, animal studies has recognized the fact that animality (just like humanity) is first and foremost a figurative relation to the symbolic order. Third, I worry about the pastoral strain that runs through Haraway’s manifesto and about the positions of exclusion that the companion-species relationship creates. Focusing on the relationship between shepherds and sheep dogs, we can indeed see the symbiosis between companion species at work as it finds expression in emotional and discursive registers. But what about the similarly symbiotic relationship between a soldier and a guard dog? As I demonstrate by revisiting the case of Abu Ghraib with which I began this chapter, the bond or symbiotic relationship between the dog and the soldier becomes the very grounds of aggression against abjected others, creating a third position, that of the detainee who is relegated to a position of animality that is excluded from legal rights, but whose exclusion we can critique via the discourse of animal rites.

The Dog in the Picture: Animal Representation at Abu Ghraib

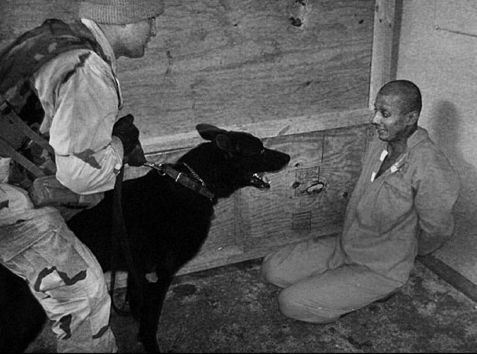

At Abu Ghraib prison, guards acted out the drama of sovereignty as a drama of animal representation. One principal mode for disciplining prisoners was treating and depicting them as animals.91 To that purpose, the guards availed themselves of a host of devices, including dog leashes, guard dogs, real and imaginary sex acts. These sex acts drew on bestiality as part of their “postdomestic” visual repertoire.92 The guards not only used photography to document the abuse but turned representation into its own form of abuse: guards deliberately made prisoners aware that photos were being taken and threatened to release the photos in order to shame prisoners into cooperation.93 But photographic representation was not just a means of abuse; it also served to affirm the guards’ own subjectivity: the initial audience for these photos were the perpetrators of the violence, who understood themselves to be acting on behalf of and for the good of the larger national community.94 It is striking that they photographed not only their victims, but also themselves in the act of victimizing others. By inscribing themselves in the photographic representations of their actions, they tried to generate solidarity between themselves and their fellow American viewers, who were “meant to identify with the proud torturers in the context of the defense of a political and cultural hierarchy.”95 When the photos were leaked to a larger audience, however, the spectatorship shifted from people who participated in the abuse and the brutal assertion of sovereignty to an audience that critiqued those practices and whose members were formed, via that critique, as liberal subjects. Instead of identifying with the torturers, this audience condemned their actions and reacted with sympathy to the victims of the abuse and to their suffering.

According to Anne McClintock, this shift in identification came about because the photographs conjoined the two formerly separate functions of the camera that Susan Sontag and John Berger identified: its capacity to function “as an instrument of state surveillance” and its capacity to function “as a means of private pleasure and spectacle for the masses.” The collision of these two representational discourses, McClintock argues, “threatened to rupture the function of state surveillance and plunge the administration into crisis.”96 But the leak of the photographs did not fundamentally disrupt the biopolitical order; on the contrary, because the legal fallout impacted only the Americans involved in these acts but not their victims, the law corroborated the division between humanity and animality that the guards had enacted: the detainees continued to be excluded from legal representation.

In their response to the photos of prisoner abuse at Abu Ghraib, scholars, journalists, and politicians focused on two issues: the images’ relation to pornography and their relation to lynching. As W. J. T. Mitchell pointed out at the time, “Most of the furor over the photographs of torture … has centered on the pornographic pictures.”97 Right-wing politicians joined forces with Slavoj Žižek in reading the abuse as the result of pornography; they argued, as Frank Rich summed it up in his column’s title, that “it was the porn that made them do it.”98 Pointing to the accounts of sodomy that accompanied the photographs, Dora Apel saw the images as “indulging a covert form of homoerotic gratification through the subjugated bodies of black men.”99 These commentaries cumulatively suggest that the images were shocking because of their familiarity and their construction of “an American family album of racist, pornographic iconography.”100 Summing up the relation of these images to a larger visual repertoire, McClintock argues that they are “continuous with a long imperial archive of colonial and racist cruelty. They belong to a well-established, imperial regime of discipline and punishment in which colonized people were for centuries depicted by the West as historically ‘primitive,’ as animalized, as sexually deviant: the men feminized, homosexualized, or hypersexualized; … [This] long-standing and tenacious imperial narrative of racial ‘degeneration’ [was] at the very moment of its redeployment … once more elided in the storm of moral agitation about pornography.”101

Although that elision might be true for the larger popular discussion of the images, scholars have insistently drawn attention to the racial dimension, especially by focusing on the similarity between the modes of representation employed in these images and those employed in lynching photos.102 What has been missing, however, is an understanding of the role that species violence plays not just as another dimension of abuse, but also as the underlying mechanism by which violence becomes racialized and gendered. As Carrie Rohman has pointed out, “The coherence of the imperialist subject, like that of the Freudian subject, often rests upon the abjection of animality.”103

Images of bestiality and practices of bestialization lie at the crux of colonial violence and legal formation; they reveal the underlying “pornography of the law” and inscribe animality at its founding.104 Resurgent in the abuse at Abu Ghraib and the response to it was the implicit association of sodomy with bestiality—that is, the link between being “animalized,” “sexually deviant, and “homosexualized.”105 The popular press repeatedly associated sexual violence with a crossing of the species line—for instance, in headlines such as “Abu Ghraib: Inmates Raped, Ridden Like Animals, and Forced to Eat Pork.”106 In the many assessments that have by now been published on this abuse, the commentators usually reference the use of animal imagery in the abuse but fail to provide an account of its functions as an aspect of torture. For that matter, many of the writers themselves take over this imagery in a strange move that not only fails to perform an analytic function but also recycles this imagery. One of the few commentators to address this animalization directly is Judith Butler. Arguing that “there is something more in this degradation [at Abu Ghraib] that calls to be read,” she identifies that excess as “a reduction of these human beings to animal status, where the animal is figured as out of control, in need of total restraint”—like Mather’s “choler” in need of a collar. For Butler, “the bestialization of the human in this way has little, if anything, to do with actual animals, since it is a figure of the animal against which the human is defined.”107 Useful as these observations are, Butler’s conclusion is too hasty in that it overlooks the importance of animals and animal representations for unsettling “an established ontology” and producing what she describes as “an insurrection at the level of ontology, a critical opening up of the questions, What is real? Whose lives are real? How might reality be remade? Those who are unreal have, in a sense, already suffered the violence of derealization. What, then, is the relation between violence and those lives considered as ‘unreal’? Does violence effect that unreality? Does violence take place on the condition of that unreality?”108

In the encounter with animals, we see suspended the differentiation between subjects and nonsubjects that underlies the symbolic order and its concomitant forms of representation. As Deborah Morse and Martin Danahay have argued, bestiality suggests “acts that take people out of the realm of the ‘human’ but that also bring animals within the matrix of human desire, sin and transgression.”109

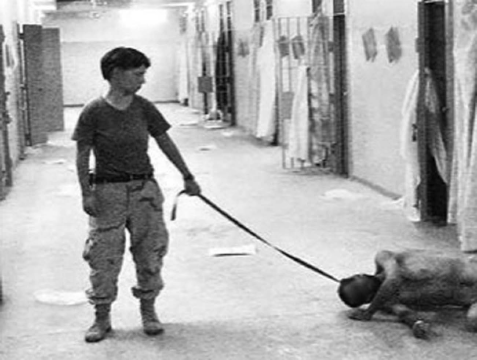

The images out of Abu Ghraib become legible in a new way when we think about them in relation to bestiality and bestialization, on which they trope incessantly.110 In figure 1.1, we see Lynndie England in U.S. Army fatigues holding an Iraqi prisoner on a dog leash. England had been well prepared for the military’s use of animal imagery in the service of violence. In her civilian life, she had worked at the aptly named Pilgrim’s Pride chicken-processing plant in Moorefield, West Virginia. When People for the Ethical Treatment of Animals conducted an undercover investigation at that plant, it caught on video workers “stomping on chickens, kicking them, and violently slamming them against floors and walls. Workers also ripped the animals’ beaks off, twisted their heads off, spat tobacco into their eyes and mouths, spray-painted their faces, and squeezed their bodies so hard that the birds expelled feces—all while the chickens were still alive.”111

Compared to this description and other photos from Abu Ghraib, the extreme physical violence seems muted in the photo of England and the leashed detainee, but the picture nevertheless indicates the range of representational devices that supplement physical violence. The photo establishes a visual hierarchy: the soldier stands looking down on the detainee, whose face is on the level of her combat boots. Stripped naked, he is relegated to a hypersexualized position of sheer physicality. The dog leash establishes his animalized position and functions as an instrument of control wielded by England within a disciplinary regime that exercises (il)legality via punishments and abjection.112 But England’s position in this image is downright illegible: she is ambiguously gendered; she seems to be actively giving and passively following orders; she is using as an instrument of torture a device that also serves to connect people with pets; she occupies the position of the sovereign issuing the ban by creating a wolf-man while apparently participating in the bourgeois rite of dog walking; she is asserting her subjectivity by enacting a ritual of bestialization that will make her subject to the law from which she temporarily removes herself; and she seems to be revealing the underlying order of the law—namely, the differentiation between human beings and animals—by violating the law by treating a human being as an animal.

The difficulties of reading this image stem from the stakes of this encounter: the image is working out the differentiations between subjects and nonsubjects that underlie the symbolic order and its concomitant forms of representation. Bestialization marks a moment where representation is both inoperative and emergent, where the metaphoric and the literal conjoin and become differentiated. In that sense, this picture is both illegible and overdetermined: we can read this image as a simile (the detainee is being treated like a dog) or as a metaphor (England has leashed a dog), and thus our reading practice already establishes our complicity with or our critique of the abuse. The image can stand in for the definition of metaphor that the Concise Oxford Dictionary of Literary Terms provides: “The most important and widespread figure of speech, in which one thing, idea, or action is referred to by a word or expression normally denoting another thing, idea, or action, so as to suggest some common quality shared by the two. In metaphor, this resemblance is assumed as an imaginary identity rather than directly stated as a comparison: referring to a man as that pig, or saying he is a pig is metaphorical, whereas he is like a pig is a simile.”113 Using the visual iconography of the leash to suggest a common quality between the detainee and a dog, this stated resemblance inaugurates an “imaginary identity” between the objects of comparison. Although this association serves denigrating purposes, we know that metaphor also doubles back on itself via a process Henry Louis Gates has identified as “signifyin’.”114 We perform such an act of reversal by reading the image as an act of “brutality”—that is, by judging the soldier and not her victim as a “brute.” Troping on tropes reassigns metaphors but ultimately perpetuates their denigrating violence: reversing who counts as a brute does not critique the category of brutality as such. Instead of focusing on the reversibility of metaphor, I want to puzzle over the slippages of animal similes that lay claim to being metaphors; in other words, I want to examine how our reading of “the animal” itself establishes and unsettles the distinction between the physical and the symbolic, the body and its representations, the metaphoric and the metamorphic.