A basic understanding of weather patterns and meteorology are a must for the climber and mountaineer. Thanks to communication technology, we often have access to up-to-date weather forecasts and warnings, but this is not always the case. Batteries die and service can sometimes be nonexistent. In these cases, a rudimentary knowledge of weather can make the difference between enjoying a warm meal and a cold beer in town and eating the crumbs left in your pack in a cold, cramped improvised bivy. This chapter is a primer in identifying concerning weather patterns and preventing injury caused by changing conditions. Many of these environmentally related maladies are discussed in other chapters, including hypothermia and frostbite (Chapter 12), hyperthermia (Chapter 13), and lightning strike (Chapter 15).

The ability to understand changes in barometric pressure, to identify clouds and the weather patterns they indicate, and to make decisions based upon these and other factors is key to staying safe while in the mountains.

So what is weather? Weather is the condition of the atmosphere on Earth at any given location during a period of time. The sun, through heat, water, atmospheric moisture, and changes to our air, creates the weather as we experience it.

The sun gives rise to all weather patterns that occur on Earth. Its heat causes water to evaporate into the air and causes air to rise. As the air rises to higher altitude, its temperature begins to cool. This cooling causes the moisture trapped within the rising air to consolidate and form droplets. As these droplets condense and grow larger, they become so heavy they can no longer be suspended within the atmosphere. This condensed moisture then falls back to Earth as rain, freezing rain, sleet, hail, or snow.

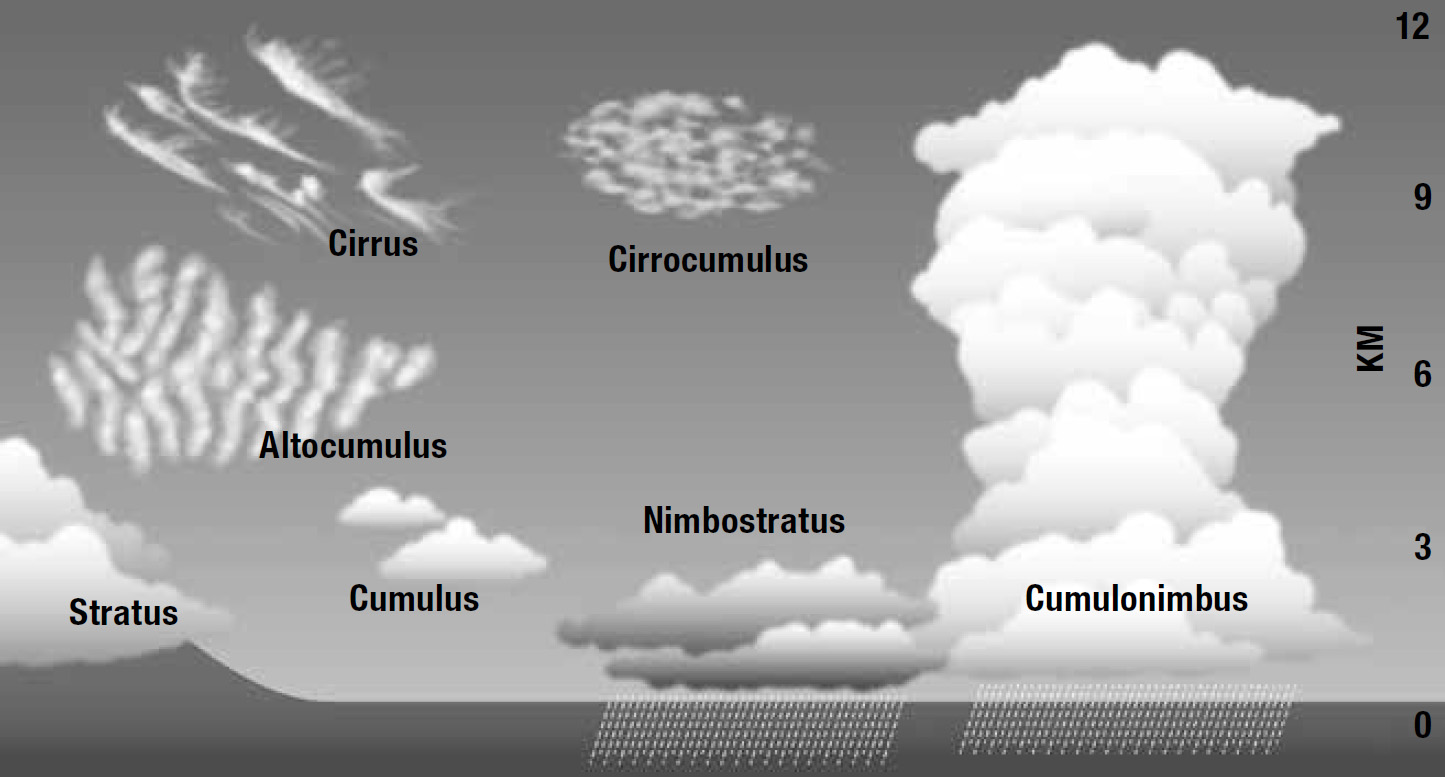

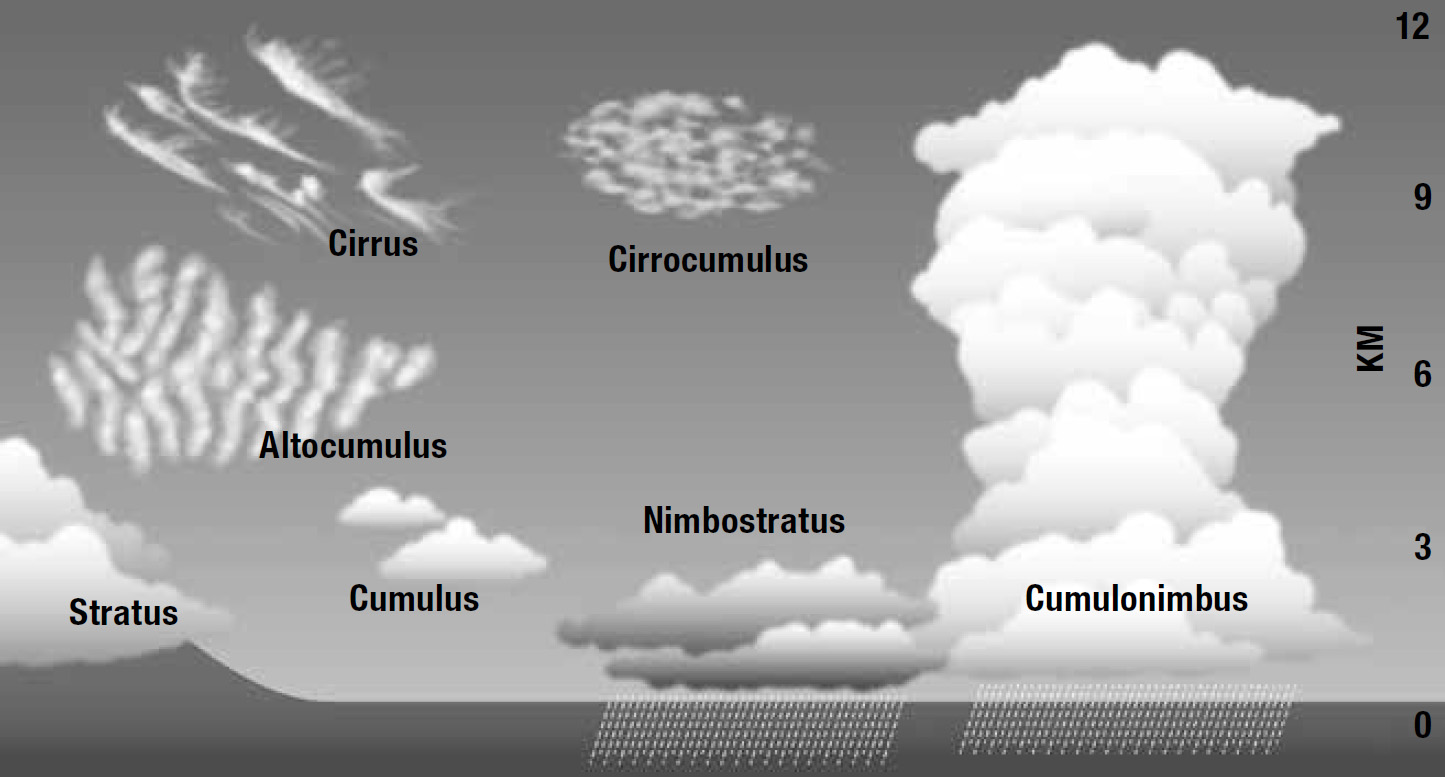

Clouds can be used to detect coming changes in weather. There are two main types of clouds: cumulus and stratus. Cumulus clouds are tall and puffy and are associated with unstable air. Stratus clouds are usually flat and layered, and generally occur when the air is stable. Within these two broad types, clouds are subdivided based upon their location within the atmosphere (low, middle, high, and towering). Each indicates a different type of weather pattern, and thanks to this, an astute mountaineer can be forewarned of approaching bad weather (Figure 16-1).

Low clouds occur at 3,000 meters and below. They include cumulus clouds (white and fluffy) that signal good weather if they are far apart or bad weather if they are large and close together. Stratocumulus clouds are white or gray. Often seen in rolling, lumpy bands, these clouds will produce light precipitation if they are low or thick.

Low stratus clouds are gray, a color that deepens depending upon the thickness of the cloud layer. They often resemble fog and indicate that precipitation—usually in the form of drizzle or light snow—may shortly occur. If this cloud layer lifts quickly in the morning, weather during the day will often be good. Nimbostratus clouds are dark gray in color. These thick clouds, which often prevent sunlight from reaching the earth, are precursors of long and steady precipitation.

FIGURE 16-1. DIFFERENT TYPES OF CLOUD FORMATIONS

Middle clouds occur between 3,000 and 6,000 meters and are divided into two main categories, altocumulus and altostratus, together with a third cloud type distinct to mountainous regions: lenticular. Altocumulus clouds resemble waves or ripples, are white/gray in color, and are thicker than their higher cousins, cirrocumulus. Though considered good weather, they can produce rain over higher mountains. Altostratus clouds usually form a gray blanket across the sky and resemble haze. These clouds have no defined shape and are generally thin in texture. If they begin to thicken, this is a sign of coming precipitation. Lenticular clouds are lentil-shaped clouds that form around the tops of mountains. They suggest high winds of 30 mph or more at high altitude, and are among the most often-photographed weather phenomena in the mountains.

High clouds—those generally above 6,000 meters—are subdivided into three categories: cirrocumulus, cirrostratus, and cirrus. Cirrocumulus clouds indicate coming precipitation (often rain) due to instability and to their increasing moisture. These clouds resemble the rippled look of sand as the tide recedes. Cirrostratus clouds, much like their lower cousins, altostratus and nimbostratus, have no defined shape and often produce a “halo effect” around the sun or moon. These clouds often precede a warm front. Cirrus clouds are wispy and thin and indicate good weather; but if cirrostratus clouds follow closely behind cirrus clouds, expect precipitation, usually within 24 to 48 hours.

The final types of clouds are the multilayered or towering clouds called cumulus and cumulonimbus. Swelling cumulus clouds are white and puffy in nature and are a sign of unstable atmospheric conditions. These often precede cumulonimbus clouds and may form along the leading edge of a cold front. Cumulonimbus clouds are towering with dark bases and sometimes form an “anvil” shape at the top. They often bring precipitation and extreme weather and may be associated with lightning (Chapter 15).

Interpreting cloud formations and approaching weather patterns requires practice and experience. Spending time observing the sky and relating it to professional forecasts will help a climber to develop the ability to predict weather based upon cloud formations.

Thunderstorms and the lightning associated with them are a considerable danger for climbers—so much that the entirety of Chapter 15 is dedicated to lightning injuries. Thunderstorms are caused when large air masses, warmed by the earth, rise quickly within the atmosphere. As this warm air rises, it is cooled by the upper atmosphere and large, towering clouds form. The energy created through this process is released in the form of thunder and lightning. Thunderstorms generally develop in the early to late afternoon, the warmest part of the day. Mountainous areas experience more storms than flat areas. This is due to an increase in the “lift” of warm air when moving against mountain ranges (known as orographic lift), particularly when wind encounters a mountain chain perpendicularly. Hail often accompanies thunderstorms when the storm has strong updrafts and downdrafts, and occurs more frequently in the mountains, since hail often melts before reaching lower and warmer elevations.

Wind is created when air moves from an area of high pressure to an area of low pressure. It is stronger when the pressure difference is greater. This is known as the pressure gradient. Mountain winds can be extremely volatile because of the varied terrain and topography in mountainous regions.

Winds in the higher atmosphere interest mountaineers because they directly influence weather conditions in our chosen terrain. Winds aloft move at a greater speed than those closer to the surface. An improvised method to estimate the speed of winds at altitude (1,500 to 3,000 m) is to double the wind speed forecast for a nearby low-level region.

Lee waves, a noteworthy wind event in the mountains, create the lenticular clouds mentioned above. Wind speeds of at least 30 mph are needed to form these clouds, and if they are jagged or rough, wind speeds are usually much higher. Winds that cause these conditions are generally perpendicular in relation to the mountain chain and create strong gap winds.

Gap winds, also known as channeled winds, can be dangerous. Terrain that restricts or channels wind can increase its speed dramatically. Careful assessment of terrain is important to avoid traveling unaware into an area with gap winds, especially along narrow or knife-edge ridgelines.

Mountainous terrain can also create what are known as converging and diverging winds. Like the confluence of water from two rivers, winds can gain speed when combined with other channeled winds. This usually occurs when two valleys converge to form a larger valley. The wind speed from each smaller valley increases as they meet. The opposite occurs when the wind reverses direction and flows from a main valley into two smaller branches with speeds decreasing.

Climbers should consider the effects of terrain blocking and the day/night wind changes on a mountain. Terrain blocking is the effect on wind by a mountain or land feature that diverts or disrupts its direction and speed. This occurs on the leeward side of the mountain and is like a windbreak that is often utilized by climbers. Day/night wind changes occur twice daily with wind flowing uphill from the valleys during the day and reversing direction and flowing downhill at night. The gathering of colder air in the valleys at night causes a temperature inversion, and the resulting pressure gradient then forces the air to higher altitude. As the warmth of the air increases during the day, the temperature inversion ends.

The final, and probably the most important, fact about wind is simply this: The force of wind increases exponentially as speed increases. Forty mph winds are four times stronger than 20 mph winds, not twice as strong. Consult a wind speed table to gain a better understanding of wind speed effects.

Barometers are the most useful instruments for predicting weather available to climbers except for real-time, quickly updated weather forecasts from professional meteorologists. Barometers are most useful when used in a stationary position (e.g., base camp) without a change in altitude produced by climbing. Barometer readings must be measured over time, with decreasing barometric pressure indicating worsening weather and increasing barometric pressure indicating improvement. If in transit, barometer readings will decrease with elevation gain and increase with elevation loss, and a small fluctuation in barometric pressure will occur even in a stationary position (around 0.04 mmHg). Barometers are most reliable in mid-latitudes. The equator and regions beyond 60° latitude contain areas of low pressure that are fairly constant throughout the year and can alter readings. This is of particular significance for mountaineers in Alaska, Antarctica, the Andes in Ecuador and Peru, and Mt. Kilimanjaro and Mt. Kenya in Africa.

Most altimeters work using barometric pressure readings and must be calibrated to ensure accuracy. Many wristwatches provide rough approximations of altitude as well as barometric readings. These watches often also include a thermometer, but it is frequently inaccurate due to the proximity and radiant heat of the wearer. Small and lightweight thermometers that include a windchill chart on the back are cheap and a convenient piece of equipment for a mountaineer.

A basic understanding of weather patterns and ability to recognize basic features that results in poor weather conditions is a must for all climbers and can prevent many of the environmental based injuries discussed within this book.