47

Gastrointestinal disorders

Vomiting

This is the forceful return of gastric contents through the mouth or nose. In contrast to regurgitation or possetting, the effortless return of small quantities of milk, which is very common during the first few months of life.

The significance of the vomiting will depend on:

- infant’s age

- frequency, amount and characteristics of vomiting, e.g. if projectile

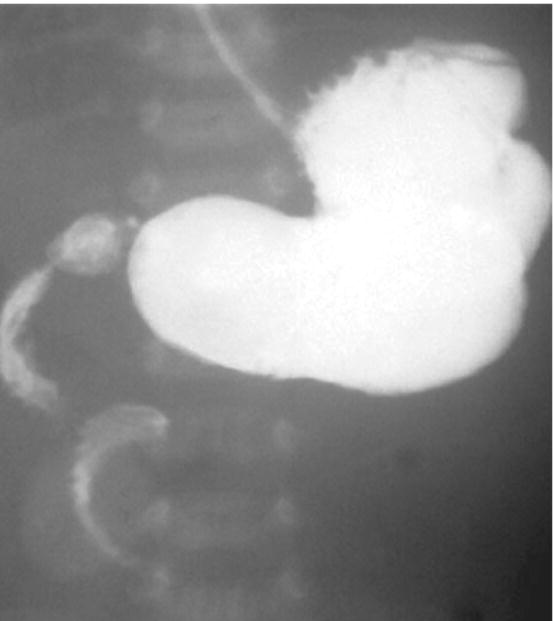

- presence of bile or blood (Fig. 47.1)

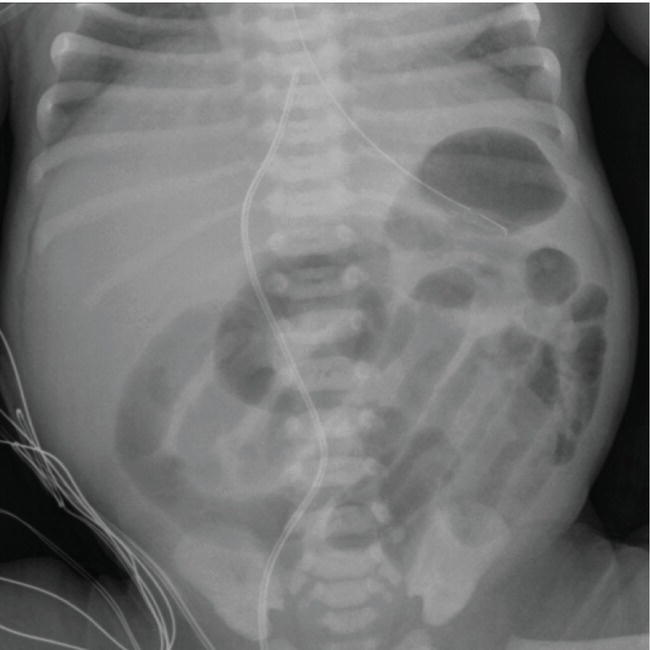

- abdominal distension (Fig. 47.2)

- stool characteristics – delayed passage of meconium or absent transitional stools

- presence of dehydration, weight loss

- evidence of a systemic illness – poor feeding, fever, lethargy.

Fig. 47.1 This infant presented with blood-stained vomiting at 12 hours of age. Water-soluble contrast upper gastrointestinal study demonstrates coiled corkscrew appearance of second and third parts of duodenum due to midgut volvulus from malrotation.

(Courtesy of Dr Annemarie Jeanes.)

Fig. 47.2 Abdominal X-ray showing distended loops of bowel in an infant with persistent vomiting.

Causes

Physiologic:

- Gastroesophageal reflux

- Ingestion of maternal blood

- Overfeeding

- Incorrectly positioned nasogastric tube

Infection:

- Systemic – septicemia, urinary tract infection, meningitis

- Local – gastroenteritis

Mechanical/surgical:

- Intestinal obstruction – see Chapter 48

- Paralytic ileus – sepsis, electrolyte disturbance

- Necrotizing enterocolitis – see Chapter 36

CNS:

- Raised intracranial pressure – cerebral edema, intracranial or subdural bleed, hydrocephalus

- Kernicterus

Drugs:

- Side-effects – caffeine, theophylline, antibiotics

- Withdrawal (abstinence) – heroin, methadone

Cow’s milk protein intolerance

Inborn errors of metabolism (rare)

Endocrine:

- Congenital adrenal hyperplasia (rare)

Diagnostic clues

Bile-stained vomiting (yellow–green)

Causes:

- Intestinal obstruction – distal to ampulla of Vater.

- Necrotizing enterocolitis.

- Incorrectly positioned nasogastric tube.

- Feeding intolerance in extreme preterm infants establishing feeds (common and presence of bile not significant unless there is abdominal distension or features of necrotizing enterocolitis).

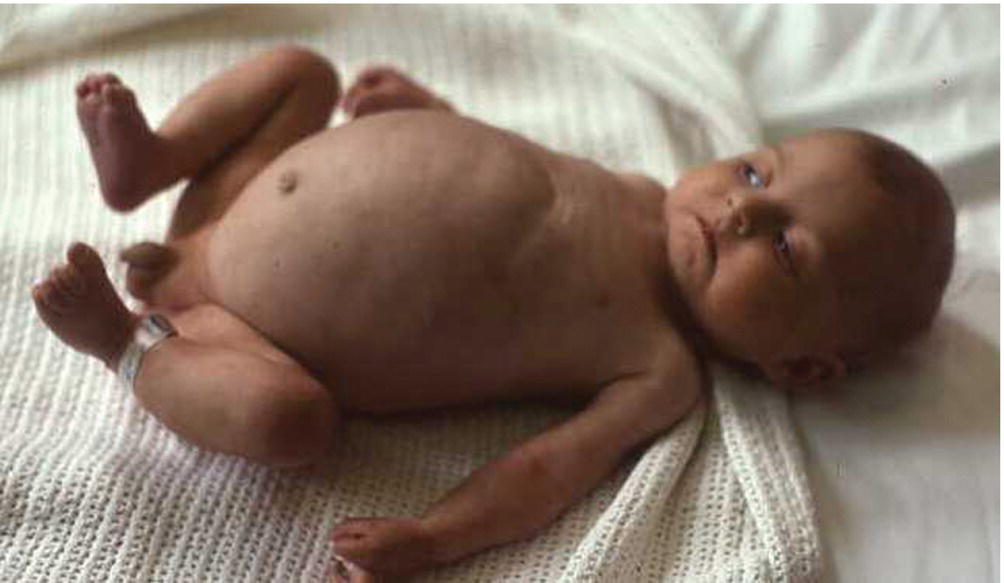

Vomiting with abdominal distension

Causes:

- Intestinal obstruction (Fig. 47.3).

- Paralytic ileus – sepsis, electrolyte disturbance.

- Necrotizing enterocolitis.

Fig. 47.3 Abdominal distension from Hirschsprung disease.

Blood-stained vomiting

Flecks of fresh blood or dark-brown coffee grounds not uncommon in otherwise well infants and usually resolve spontaneously.

Causes:

- Swallowed maternal blood – from delivery or cracked nipple. Can be differentiated from fetal blood with the Apt test (see Table 47.1).

- Trauma – laryngoscopy at resuscitation, passing a nasogastric tube.

- Malrotation – uncommon but important to diagnose early (Fig. 47.2).

- Stress ulcer – hypoxic–ischemic encephalopathy.

- Abnormal coagulation–thrombocytopenia, vitamin K deficient bleeding, liver disease, DIC (disseminated intravascular coagulation), etc.

- Drug-induced – corticosteroids, indomethacin, ibuprofen.

Table 47.1 Vomiting – investigations to consider and their purpose.

| Imaging | Blood tests | Urine and stool tests |

| Plain abdominal X-ray: | Electrolytes and acid-base – for imbalance | Urine – microscopy and culture |

| Sepsis work-up – to exclude infection Creatinine/blood urea nitrogen (urea) – for dehydration and renal function | Stool – for blood Other: |

| Glucose – for hypoglycemia Calcium, magnesium, phosphorus, liver function tests Coagulation screen – if blood in vomit or sepsis Consider:

|

|

Investigations

Most infants will require no or limited investigations. Those to be considered are listed in Table 47.1.

Management

Depends upon severity and cause. Intravenous fluids may be required to correct electrolyte disturbances, acid–base imbalance and dehydration.

Gastroesophageal reflux

Incidence is increased in:

- preterm infants, particularly with bronchopulmonary dysplasia or on caffeine

- following necrotizing enterocolitis and tracheoesophageal fistula repair

- infants with neurodevelopmental delay, e.g. following hypoxic–ischemic encephalopathy or hypotonia.

Associated features

- Failure to thrive.

- Irritability, arching of the back from esophagitis.

- Anemia (iron deficiency).

- Aspiration pneumonia.

- Apnea.

- Acute life-threatening events (ALTE).

Investigations

- Usually clinical diagnosis.

- Esophageal pH study, impedance study may show non-acid reflux, sometimes upper gastrointestinal contrast or endoscopy.

Management

Most do not need treatment. If required, use stepwise approach.

- Reduce interval between feeds, thicken feeds, alginate/antacid (Gaviscon), upright positioning.

- Prokinetic e.g. domperidone, but concerns about arrhythmias.

- H2 receptor antagonist, e.g. ranitidine; proton pump inhibitors, e.g. omeprazole – reduce gastric acidity.

- Surgery – fundoplication with or without gastrostomy. Evidence of efficacy of medication in neonates is limited.

Esophageal atresia

- More than 85% associated with tracheoesophageal fistula (Fig. 47.4).

- 1 in 3500 live births.

- Often associated with other abnormalities, e.g. VACTERL syndrome (vertebral anomalies, anal atresia, cardiac, tracheoesophageal, renal, limb).

Fig. 47.4 Different types of esophageal atresia and tracheoesophageal fistula.

Presentation

- Prenatal – polyhydramnios, absent stomach bubble, associated abnormalities.

- Birth onwards – frothing of oral secretions (Fig. 47.5) with choking and cyanosis.

Fig. 47.5 Frothing of oral secretions after birth from esophageal atresia.

Investigations

- Unable to pass wide-bore orogastric tube; confirmed on chest X-ray, shows tube curled in esophageal pouch. Air in the stomach indicates a distal fistula is present.

Management

- Pass large orogastric tube and aspirate pouch to avoid aspiration pneumonia.

- Intravenous fluids for resuscitation and maintenance. Early PN(parenteral nutrition).

- Surgical correction is required.

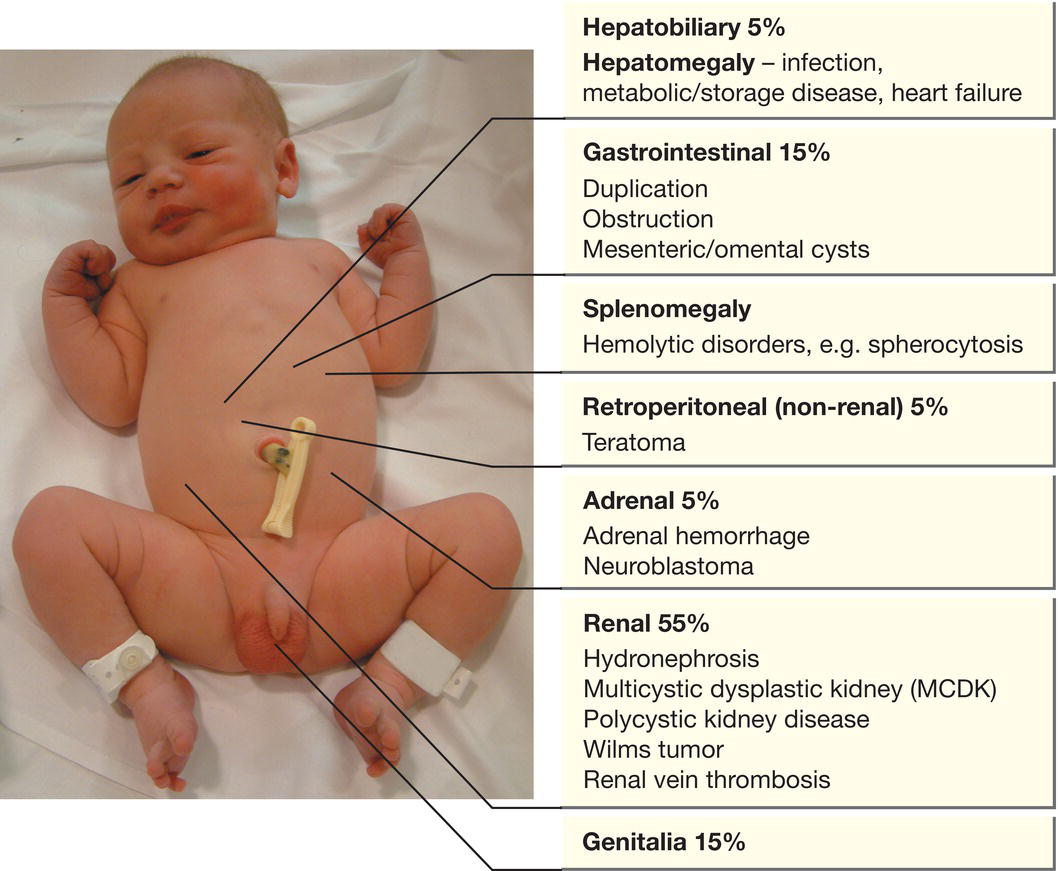

Abdominal masses

Often detected in utero on ultrasound screening. The causes are shown in Fig. 47.6.

Fig. 47.6 Abdominal masses and their causes.

Abdominal wall defects

Omphalocele (Exomphalos)

Defect in umbilicus with herniation of abdominal contents. The bowel is covered by peritoneum and amnion (Fig. 47.7). Vary in size, from small defects where some bowel herniates into the umbilical cord to large defects where there is herniation of both bowel and liver. Occurs in 1 in 5000 fetuses. Most are diagnosed on prenatal ultrasound screening (see Fig. 3.2); 40% are associated with trisomy 13 or 18, Beckwith–Wiedemann (see Chapter 45) or other syndromes.

Fig. 47.7 Omphalocele.

Management (see video: Gastroschisis)

- Pass a large-caliber nasogastric tube at delivery to limit passage of air into the bowel, and nothing by mouth.

- Place infant’s lower body into a sterile plastic wrap (bag) to limit heat and fluid loss and protect the bowel from damage and infection.

- Give intravenous fluids.

- Check for other anomalies, including echocardiography.

- Surgical repair is usually performed on the first day of life. If the defect is large, the viscera may be placed in a silastic silo, and gradually placed in the abdomen over several days.

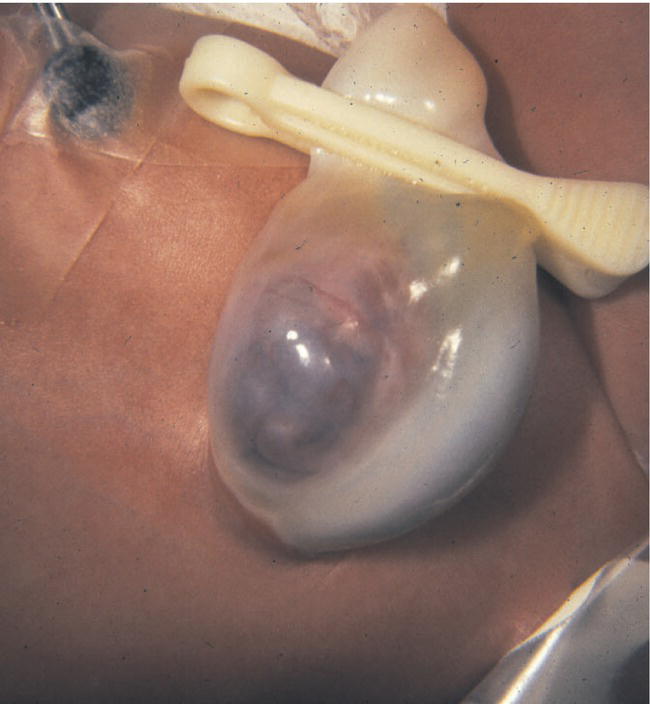

Gastroschisis

Defect in anterior abdominal wall, usually to right of umbilicus, with herniation of the bowel (Fig. 47.8). In contrast to omphalocele, there is no protective covering of the bowel and the incidence of associated anomalies is low, other than intestinal atresia. The condition is usually diagnosed on prenatal ultrasound screening (Fig. 47.9).

Fig. 47.8 Gastroschisis.

Fig. 47.9 Gastroschisis on prenatal ultrasound scan.

(Courtesy of Dr David Lissauer.)

Management

- The infant’s lower body is placed into a sterile plastic wrap (bag or cling film).

- Pass a large-caliber nasogastric tube at delivery to limit passage of air into the bowel.

- Give intravenous fluids; colloid may be required to replace fluid losses from the exposed bowel. Closely monitor electrolytes. Give broad-spectrum antibiotics.

- Surgical repair can be performed directly or the abdominal contents can be gradually reduced after placing into a silo (Fig. 47.10).

- Prolonged parenteral nutrition is usually required to establish feeds. Prognosis is good.

Fig. 47.10 Gastroschisis in silastic silo. There is also a central venous catheter for PN.

Imperforate anus

- Incidence 1 in 5000 births. Associated anomalies of genitourinary and gastrointestinal tract common, and seen in VACTERL association.

- In boys most often with fistula to urethra, in girls to vestibule adjacent to vagina-so may still pass meconium. Some lesions are complex.

- Surgery is with anoplasty or colostomy followed by repair.