The Bubishi is both a creator and a product of history. In this section, I will examine the historical origins of this work and show its impact on history. Perhaps we might better understand what the Bubishi represents by breaking down the components of the word itself. The ideogram pronounced bu means “military.” The ideogram bi means “to provide or prepare.” The ideogram shi means “record.” Together, they mean “a manual of military preparation.” In the context of karate, the Bubishi represents the patriarchal source of knowledge, a fountain from which flows strength and wisdom for those brave enough to embrace its spirit. Providing disciples with the ancient masters’ secrets, the Bubishi has for generations preserved the original precepts upon which the civil fighting traditions rest; teachings now overshadowed by more base pursuits.

Disclosing the original means and methods of orthodox Chinese gongfu (also known as quanfa or “fist way,” which the Japanese call kempo), the Bubishi conclusively imparts both the utilitarian and nonutilitarian values of the civil fighting traditions. In so doing, it reveals the magnitude of karate-do, and identifies that which lies beyond the immediate results of physical training. With one’s attention turned inward in this way, karate-do becomes a conduit through which a deeper understanding of the self brings one that much closer to realizing one’s position in life in general, and the world in which one dwells.

The Impact of the Bubishi on Modern Karate-do

Although the Bubishi is a document peculiar to Monk Fist and White Crane gongfu, it achieves an impact of more encompassing proportions. While its exact date of publication and author remain a mystery, it is nevertheless a valuable source of historical information that offers deep insights into karate-do, its history, philosophy, and application. A number of the most recognizable figures in modern karate-do have used it as a reference or plagiarized from it.

Mabuni Kenwa (1889–1952), was a karate genius and kobu-jutsu expert who was responsible for bringing together karate-jutsu’s two main streams when he created his Shito-ryu tradition more than half a century ago. In 1934 in the book Kobo Jizai Karate Kempo Seipai no Kenkyu, he wrote, “Making a copy of a Chinese book on kempo that my venerated master, Itosu Anko, had himself duplicated, I have used the Bubishi in my research and secretly treasured it.” In that same year, Mabuni Sensei was the first to make the Bubishi public. By making the Bubishi available to the public, Mabuni Kenwa introduced a legacy so profound that, even to this day, the depth of its magnitude has yet to be fully measured or completely understood.

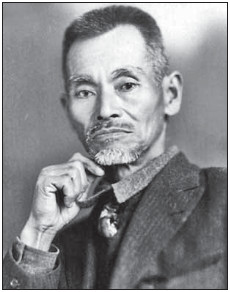

Yamaguchi Bubishi.

A significant portion of Karate-do Kyohan by Funakoshi Gichin (1868–1957) is taken directly from the Bubishi.1 Higashionna Kanryo (1853–1915) revered it; and his principal disciple, Miyagi Chojun (1888–1953), selected the name Goju-ryu from this text (see Article 13, no. 3, p. 261) to represent his unique tradition and considered it “the bible” of the civil fighting arts. The Bubishi was also used by Shimabukuro Tatsuo (1908–75) when he was establishing his Isshinryu karate tradition. The Bubishi had such a profound affect upon Yamaguchi “the Cat” Gogen (1909–89) that he publicly referred to it as his “most treasured text.”

Yamaguchi Gogen’s Bubishi.

Yamaguchi Gogen’s Bubishi.

The profound teachings of this document were no doubt gathered over a period of many hundreds of years. So to begin I think it is important to discuss the theories surrounding the origin of this work.

Possible Origins of the Bubishi in China

The Bubishi bears no author’s name, date, or place of publication.

Therefore, accurate details surrounding its origin are unavailable. It is presumed that the Bubishi was brought from Fuzhou to Okinawa sometime during the mid-to late-nineteenth century, but by whom remains unknown. There are several hypotheses surrounding the advent of the Bubishi in Okinawa. Unfortunately, none can be corroborated. On the other hand, there is testimony describing the experiences of some well-known Uchinanchu (Okinawans) who traveled to the Middle Kingdom for the sole purpose of studying the fighting traditions.

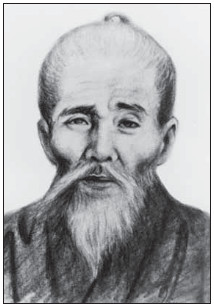

Mabuni Kenwa

Some insist that the Bubishi appeared in Okinawa by way of their teacher’s teacher. Another theory suggests that the Bubishi surfaced independently from within the Chinese settlement in the Kuninda district of Naha. Yet another hypothesis maintains that the Bubishi is a collection of knowledge compiled over many years by Uchinanchu who studied in China and belonged to a secret fraternity. All of these assumptions seem perfectly plausible. However, when subjected to critical evaluation and given the lack of data presently available, these theories remain simply speculation.

It is possible that the exact reason for the Bubishi surfacing in Okinawa may be lost to antiquity forever. However, rather than support or oppose conjecture, it might be more fitting to simply appreciate the efforts of those adventurous stalwarts who sailed the turbulent waters between the two cultures to cultivate and perpetuate these ancient traditions. The ancient Chinese combative traditions cultivated by these Uchinanchu were the base on which modern karate-do and kobu-jutsu were established.

The Two Bubishi

Actually, there are two Bubishi, both of Chinese origin and from Fuzhou. One is a colossal treatise on the art of war, published in the Ming dynasty (1366–1644); the other, believed to have been produced during the Qing dynasty (1644–1911), is that which surfaced in Okinawa. In its native Mandarin Chinese, the ideograms for Bubishi are read “Wu Bei Zhi,” but for the sake of simplicity I shall refer to the text using its Japanese pronunciation instead.

MAO YUANYI’S BUBISHI

This authoritative text on the art of war, not to be confused with Sun Zi’s treatise, was published in 1621. The author, Mao Yuanyi, was a man of considerable influence, well versed in military affairs, and was greatly influenced by his grandfather Mao Kun, who was vice-envoy to the Fujian provincial court. Concerned about his government’s deteriorating military condition, Mao felt impelled to remedy the situation. Spending more than fifteen years and researching over 2,000 books, he compiled this prodigious document, which consists of 240 chapters in five parts and 91 volumes; today a copy is stored safely within the venerable walls of the Harvard University Library.

Dealing with all military-related subjects, Mao’s Bubishi covers everything from strategic warfare, to naval maneuvers and troop deployment, to close-quarter armed and unarmed combat, and includes maps, charts, illustrations, and diagrams. Chapters 1 through 18 concern military decision-making; Chapters 19 through 51 concern tactics; Chapters 52 through 92 concern military training systems; Chapters 93 through 147 concern logistics; and Chapters 148 through 240 deal with military occupations.

In one section there are various illustrations portraying hand-to-hand combat with and without weapons. This part is believed to have been taken from the 18 chapter document Jixiao Xinshu (Kiko Shins ho in Japanese), published in 1561 by the great Chinese general, Qi Jiguan (1522–87). There are some similarities between Qi’s 32 empty-handed self-defense illustrations and those that appear in the Okinawan Bubishi.

A classified document, it was available only to authorized military personnel, government bureaucrats, and others on a need-to-know basis. During the Qing dynasty, authorities banned it for fear of it falling into rebel hands and being used for anti-government activity.

OKINAWA’S BUBISHI

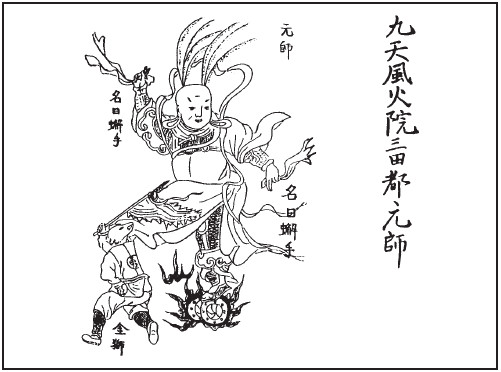

Okinawa’s Bubishi is an anthology of Chinese gongfu, its history, philosophy, and application. Focusing on the White Crane style from Yongchun village, Fujian Province, this compilation also addresses Shaolin Monk Fist gongfu and reveals its relationship to Okinawa’s civil fighting legacy of karate-do.

The contents of this anthology’s 32 articles include White Crane gongfu history, moral philosophy, advice on etiquette, comparisons of styles, defensive applications, herbal medicines, training mechanics, and Monk Fist Boxing. This may suggest that the Okinawan Bubishi was composed of several smaller books or portions of larger books. While some of this anthology is relatively easy to understand, much of it is not. Written in Classical Chinese, much of the Bubishi is, even at the best of times, perplexing. Many of the terms for the methods date back to a time all but forgotten. Other obstacles include Chinese ideograms that have been either modified since its initial writing or are no longer in use.

In addition, in order to maintain the ironclad ritual of secrecy within the martial art schools of old China, techniques were often described using names that disguised their actual meaning. As such, only those advocates actively pursuing the style were aware of the true meanings and applications of the techniques. A practice once widespread in China, this tradition, for the most part, was not handed down in Okinawa. Hence, these creative names (e.g., Guardian Closes the Gate) made technical explanations difficult to accurately decipher without knowing exactly what physical technique it represented. Contrary to popular belief, the Bubishi is not a manuscript easily understood by most Chinese or Japanese simply because they are able to read the ideograms. For the same reasons mentioned in the preceding paragraphs, most Chinese people, whether directly connected to the native fighting arts or not, would have little or no idea what such abstract descriptions mean. As for the Japanese, and Uchinanchu too, without the corresponding furigana (phonetic characters) to help clarify the meanings and usage of the Chinese ideograms, the essence of the Bubishi, like its origins, remains unclear.

There is also a surprisingly large portion of the text on the use of Chinese herbs and other medicinal remedies, which provides provocative insights into an aspect of training no longer fashionable in our day and age. Exceedingly brief and hampered by grammatical errors (resulting from being hand-copied down through the ages), Articles 10, 11, 12, 19, 22, 30, and 31 prescribe various concoctions in a way that supposes the reader already understands the principles of herbal medicine. This has proven to be the most difficult section to translate, however, after years of arduous research I am now able to present the first unabridged direct translation of these entries in any language. I should note that another writer attempted to translate this section but in his haste gave up and rewrote it, inserting modern remedies not related to what was in the actual Bubishi.

The Bubishi also includes a rather ambiguous explanation surrounding an even more obscure technique called the “poison-hand” or the “delayed death touch” (dian xue in Mandarin, dim mak in Cantonese). A science understood by very few, mastering dian xue requires remarkable dedication and may very well be the reason the Bubishi has remained such an obscure document for so long, in spite of efforts to publicize it. These articles in the Bubishi do not describe how to render a potentially violent attacker unconscious with carefully pinpointed blows, nor do these articles explain what to do if attacked. Rather, they systematically describe how to extinguish human life in very specific terms, by seizing, pressing, squeezing, or traumatizing specific vital points. These articles are presented here in their entirety.

At first I had some reservations about presenting this information, as I was concerned that it could be misused. However, today, there are a number of books and video tapes on the market that describe the theories and applications of this science. Thus anyone interested in the principles of cavity strikes, artery attacks, blood flow theory, and the death touch, can study the material that is presently available. I trust that this knowledge will not be misused and that those individuals who undertake the time-consuming process of learning this art will be scrupulous and not experiment on unsuspecting victims or use it in anything other than a life-and-death struggle.

Although the exact details surrounding the origin of the Bubishi remain unclear, it is nevertheless a valuable historic treasure. Remaining unanswered, the questions surrounding its advent in Okinawa are not altogether beyond our reach. It is entirely possible to calculate, with some degree of certainty, that which we do not know by more closely analyzing that which we do know.

For example, if, in addition to the historical details previously presented, we were to more closely examine the surviving testimony surrounding karate’s early pioneers, we might discover who were most responsible for cultivating China’s civil fighting traditions in Okinawa. Even if we are unable to accurately determine the actual source from which the Bubishi materialized, we are at least able to identify the main characters associated with Okinawa’s civil fighting traditions. In so doing, we will have isolated the range of analysis through which future study may bring even more profound and enlightening discoveries.

However, those historical discoveries will not come easily. It is the opinion of this writer that much of what was originally brought to Okinawa from the Middle Kingdom either no longer exists, or, like so much of the gongfu in China, has been radically changed. In addition to the many major styles of southern gongfu that have affected Okinawa’s fighting traditions, who is to say how many minor schools have come and gone without a trace? It is virtually impossible to trace the evolution of these styles and schools. On behalf of the Fuzhou Wushu Association’s many eminent members, Li Yiduan maintains that an incalculable number of schools and styles (sometimes practiced by as few as a single family or even one person) have either vanished, been exported to a neighboring province, or have been consumed by other styles over the generations. With that in mind, I would now like to conclude my preliminary analysis by exploring the plausible sources from which the Bubishi may have surfaced in Okinawa.

Transmission of the Bubishi

In the following section, I will discuss the various theories explaining how the Bubishi arrived in Okinawa, the personal histories of the masters who may have brought it, and the impact each had on the development of Okinawan karate-do.

In his 1983 book Hakutsuru Mon: Shokutsuru Ken (White Crane Gate: Feeding Crane Style), Master Liu Yinshan wrote that the Shaolin Temple was a sanctuary for resistance fighters during the early Qing dynasty. Seeking to eradicate any pocket of anti-Qing activity, government soldiers burned the monastery down in 1674. Among the monks who fled the monastery in Henan Province was Fang Zhonggong (also known as Fang Huishi), a master of Eighteen Monk Fist Boxing.

There are several accounts of Fang Zhonggong’s subsequent travels and activities after his arrival later in Fujian. Notwithstanding, most reports describe him as the father of Fang Qiniang, the girl who grew up in Yongchun village, Fujian, and developed White Crane Boxing. If this history is reliable, then the development of Yongchun White Crane gongfu would seem to be somewhere around the early eighteenth century. As we will soon see, a short life history of both Fang and his daughter appear in the Article 1 of the Bubishi (see p. 157). As with Five Ancestors gongfu, Monk, Dragon, and Tiger Fist Boxing, Fang’s eclectic method has obviously had a profound affect upon the growth and direction of other native boxing styles in and around Fuzhou. Incidentally, many of these gongfu styles are believed to have been later introduced to and cultivated in Okinawa. Miyagi Chojun, a direct disciple of Higashionna Kanryo (1853–1917), told us in his 1934 Outline of Karate-do that “a style” of gongfu was brought from Fuzhou to Okinawa in 1828 and served as the source for Goju-ryu karate kempo. After reading Liu Songshan’s copy of the Shaolin Bronze Man Book2 and interviewing Xie Wenliang, the great-grandson of Ryuru Ko,3 the famous gongfu master, I believe that this theory is worthy of further exploration. This, then, would seem to indicate that the Bubishi is a book handed down by either Fang’s daughter, or disciples of her tradition.4

Liu Songshan

Patrick McCarthy with Liu Songshan

The second theory surrounds Okinawa’s oldest surviving testimony regarding the philosophy of the civil fighting traditions. It refers to karate using the Okinawan term di (however, for the sake of simplicity I will use the more commonly used Japanese term te in the text). Teijunsoku Uekata (1663–1734), a scholar/statesman from Okinawa’s Nago district, wrote, “No matter how you may excel in the art of te and scholastic endeavors, nothing is more important than your behavior and your humanity as observed in daily life.” Whether this statement was influenced by Article 4 of the Bubishi (see p. 163) remains the subject of much speculation. Teijunsoku was a scholar of Chinese classics, and as the previous statement would indicate, a practitioner of the civil fighting traditions. It is possible that he may have possessed a copy of the Bubishi. If so, this would indicate that the Bubishi was extant in Okinawa from at least the eighteenth century onward. By extension this would mean that the book was written either during the lifetime of Fang Qiniang or very soon after her death. It would also indicate a link existed between the practice of te and the Bubishi in the eighteenth century, which is more than one hundred years before any of the other Okinawan masters are believed to have come into possession of it.

Xie Wenliang (wearing a Japanese-style uniform) with the author at Tokashiki Iken’s dojo in Naha.

The third theory concerns the famous karate master Sakugawa Chikudun Pechin and the Chinese gongfu master Kusankun. In 1762, an Okinawan tribute ship en route to Satsuma was blown off course during a fierce typhoon and drifted to Oshima beach in the jurisdiction of Tosahan (present-day Kochi Prefecture) on Shikoku Island. Petitioned to record the testimony of passengers and crew, Confucian scholar Tobe Ryoen compiled a chronicle entitled the Oshima Incident (Oshima Hikki). In a dialogue with the Okinawan officer in charge, one Shiohira (also pronounced Shionja) Pechin, a minister in charge of warehousing the kingdom’s rice supply, reference is made to a Chinese named Kusankun—popularly known among karate historians as Kusanku or Koshankun.

Described as an expert in kempo, or more specifically kumiai-jutsu, it is believed that Kusankun, with “a few” personal disciples, traveled to the Ryukyu Kingdom with the Qing Sapposhi Quan Kui in 1756. Shiohira’s description of Kusankun’s kumiai-jutsu demonstration leaves little to question.

Recounting how impressed he was witnessing a person of smaller stature overcome a larger person, Shiohira Pechin described what he remembered: “With his lapel being seized, Kusanku applied his kumiaijutsu and overcame the attacker by scissoring his legs.” When describing Kusankun’s leg maneuver, Shiohira used the term “sasoku,” which roughly describes the scissor action of a crab’s claw. Although Shiohira’s description of Kusankun is rather nebulous, it remains the most reliable early chronicle regarding the Chinese civil fighting traditions in Okinawa. Though Shiohira’s testimony does not mention the Bubishi, techniques like those described by Shiohira are detailed in the Bubishi.

“Toudi” Sakugawa Chikudun Pechin.

Oral tradition maintains that Kusankun was one of the teachers of the great Okinawan master Sakugawa Chikudun Pechin.5 Born Teruya Kanga in Shuri’s Tori Hori village, Sakugawa rose to prominence due in large part to his heroic exploits on the high seas while in charge of security for a prominent commercial shipping firm. Recognized for his incredible physical prowess and indomitable spirit, folklore says he was elevated to the rank of Chikudun Pechin (a warrior rank somewhat similar to the samurai, see p. 142) and assumed the name Sakugawa. He studied the fighting traditions in Fuzhou, Beijing, and Satsuma (present-day Kagoshima Prefecture) and had a profound impact upon the growth and direction of the self-defense disciplines that were fostered in and around Shuri. As such, he is now commonly referred to as “Toudi” Sakugawa, toudi being the Okinawan reading of the original Chinese characters for karate (Tang or Chinese hand). It is possible that either he or Kusankun brought the Bubishi from China to Okinawa.6

The fourth theory concerns the famous gongfu masters Ryuru Ko and Wai Xinxian, and their “student” Higashionna Kanryo. On page 4 of his 1922 publication Ryukyu Kempo Karate-jutsu, Funakoshi Gichin describes various Chinese masters who came to Okinawa and taught gongfu, presumably during the later part of the nineteenth century. Funakoshi wrote that a Chinese named Ason taught Zhao Ling Liu (Shorei-ryu) to Sakiyama, Gushi, Nagahama, and Tomoyori from Naha; Wai Xinxian taught Zhao Ling Liu to Higashionna Kanyu and Kanryo, Shimabukuro, and Kuwae; Iwah taught Shaolin Boxing to Matsumura of Shuri, Kogusuku (Kojo), and Maesato of Kuninda. Funakoshi also wrote that an unidentified man from Fuzhou drifted to Okinawa from a place called Annan (if not a district of Fuzhou then perhaps the old name for Vietnam), and taught Gusukuma (Shiroma), Kaneshiro, Matsumora, Yamasato, and Nakasato, all from Tomari. Funakoshi uses generic terms like Shorin (Shaolin) and Shorei (Zhao Ling) but did not identify specific schools or traditions. Perhaps the two most talked about figures in the Fuzhou-Okinawan karate connection are Ryuru Ko (1852–1930) and Wai Xinxian. Ryuru Ko (also pronounced Do Ryuko and Ru Ruko in Japanese), and Wai Xinxian are believed to be the principal teachers of the following famous karate masters: Sakiyama Kitoku (1830–1914),7 Kojo Taitei (1837–1917), Maezato Ranpo (1838–1904), Aragaki Seisho (1840–1920), Higashionna Kanryo (1853–1915), Nakaima Norisato (1850–1927), and Matsuda Tokusaburo (1877–1931).

Ryuru Ko has been variously described as the son of a noble family whose fortune was lost during political unrest, a priest, a former military official in exile, a stone-mason, a craftsman, and even a medicine hawker. Perhaps he was all. Until recently little was known about what art Ryuru Ko taught. Some claimed he taught White Crane, others believed it was Five Ancestors Fist, perhaps even Monk Fist Boxing. My research, in accordance with Tokashiki Iken’s, indicates his name was Xie Zhongxiang and he was a shoemaker and the founder of Whooping Crane gongfu.8 Ryuru, which means “to proceed,” was a nickname. Ko is a suffix that means “big brother.” Ryuru Ko was a student of Pan Yuba, who in turn was taught by Lin Shixian, a master of White Crane gongfu.

Xie Zhongxiang.

Similarly, Wai Xinxian’s personal history is shrouded in mystery. He has been described as a contemporary of or senior to Ryuru Ko, a master of Xingyi gongfu, a teacher of Monk Fist Boxing, and a commissioned officer of the Qing dynasty. Another popular theory is that he was an instructor with Iwah at the Kojo dojo in Fuzhou.

Many believe that Higashionna Kanryo is the most likely source from which the Bubishi first appeared in Okinawa. However, while this theory is prevalent, especially among the followers of the Goju tradition, it is still only conjecture.

Higashionna Kanryo was born in Naha’s Nishimura (West Village) on March 10, 1853. He was the fourth son of Higashionna Kanyo, and the tenth-generation descendant of the Higashionna family tree. During his childhood he was called Moshi, and he had a relative named Higashionna Kanyu, who was five years his senior and also enjoyed the fighting traditions. He lived in Naha’s Higashimura (East Village) and became known as Higashionna East, while Kanryo was called Higashionna West. First introduced to the fighting traditions in 1867, when he began to study Monk Fist Boxing (Luohan Quan) from Aragaki Tsuji Pechin Seisho (1840–1918 or 20),9 Aragaki was a fluent speaker of Chinese and worked as an interpreter for the Ryukyu court. Higashionna spent a little over three years under his tutelage until September 1870, when Aragaki was petitioned to go to Beijing to translate for Okinawan officials. At that time, he introduced Kanryo to another expert of the fighting traditions named Kojo Taitei (1837–1917) who also taught him. It was through Kojo Taitei, and a friend of the family named Yoshimura Udun Chomei (1830–1898), that safe passage to China, accommodations (probably in the Kojo dojo in Fuzhou), and instruction for young Kanryo were arranged. Higashionna set sail for Fuzhou in March 1873.

Aragaki Tsuji Pechin Seisho.

Xie Wenliang (b. 1959), the great-grandson of Ryuru Ko, characterized Kanryo as an enthusiastic youth who had come to Fuzhou from Okinawa to further his studies in Chinese gongfu.10 Kanryo did not start studying with Ryuru Ko until 1877.11 Yet oral tradition maintains that he set sail for Fuzhou in 1873! Assuming both dates are accurate, a new question arises: what did Higashionna do for the first four years he was in Fuzhou? I believe he spent the time training at the Kojo dojo. It was during this time that he may have studied with gongfu Master Wai Xinxian, who is said to have taught at that dojo.12 Some speculate that he may have even trained with gongfu Master Iwah there.

It is not surprising to learn that Kanryo did not become a live-in disciple of a prominent master, as was previously believed. After all, Kanryo was a young non-Chinese who could not speak, read, or write Chinese. Chinese gongfu masters rarely, if ever, accepted outsiders as students, let alone foreigners. It was not the way things were done during the Qing dynasty (1644–1911) in China. However, with an introduction from the Kojo family, who were well known in Fuzhou, Kanryo began training with Xie Zhongxiang. The reason why Kanryo studied with Xie remains the subject of much curiosity.

Notwithstanding, Ryuru, who was born a year before Kanryo (in July 1852), was more like a big brother than a teacher to Higashionna. Although just an apprentice shoemaker, evidently his proficiency in gongfu was remarkable.

Yoshimura Udun Chomei.

In 1883, the year after Kanryo returned to Okinawa, Ryuru, at age thirty-one, succeeded in opening his own school of gongfu in Fuzhou. He went on to become one of Fuzhou’s most prominent masters before he died in February 1930 at age seventy-seven. Although the facts surrounding his Uchinanchu students have yet to be fully explored, there can be no question that his teachings have profoundly effected the growth and direction of karate-do.

Although it is not presently known what style was taught at the Kojo dojo, we know that Ryuru taught five quan: Happoren (Baiburen in Mandarin, also known as Paipuren in Japanese), Nepai (Nipaipo in Japanese), Doonquan (also called Chukyo or Jusanporen), Roujin (Jusen), and Qijing (Shichikei), but is said to have known many more. When we examine the various quan that Kanryo Sensei taught after returning from China in 1882, we discover that there are quan from sources other than Whooping Crane. Furthermore, Higashionna never received a teaching license in Ryuru Ko’s art. This would suggest that Kanryo Sensei not only learned the principles of other styles, but also blended them into an eclectic hybrid. Otherwise, the discipline Kanryo Sensei brought back from Fuzhou would have therefore been Second-generation Whooping Crane gongfu or Kojo-ryu. However, such was not the case, and he never used the name Whooping Crane gongfu or Kojo-ryu. In fact, the same can be said of Uechi Kanbun, who studied Tiger Fist gongfu under Zhou Zihe (1874–1926): why did he not call his style Second-generation Tiger Fist gongfu? Cross-checking the Chinese ideograms that represent the quan of various other Fujian gongfu styles, I believe I may have determined some plausible sources from which Higashionna Kanryo learned his other quan if they did not come from the Kojo dojo.

There are four other styles of Crane Boxing, each of which use their own Saam Chien quan (Sanchin kata), and one also uses Sanseiru and Niseishi (Nijushiho). Dragon Boxing uses Seisan, Peichurrin (Suparinpei), Saam Chien, and a quan called Eighteen Scholar Fists (mentioned in the Bubishi), in addition to other quan. Tiger Boxing also uses Saam Chien, Sanseiru, and Peichurrin, among other quan. Dog Boxing, or perhaps better known as Ground Boxing, also uses Saam Chien and Sanseiru, among others. Arhat Boxing, also known as Monk Fist, uses Saam Chien, Seisan, Jutte, Seipai, Ueseishi (Gojushiho), and Peichurrin among others. Lion Boxing uses Saam Chien and Seisan among others.

There can be no question that Higashionna Kanryo had, after living in Fuzhou for nearly a decade, come to learn the central elements of several kinds of Chinese gongfu. Remember that Miyagi Sensei told us, in his 1934 Outline of Karate-do that “the only detail that we can be sure of is that ‘a style’ from Fuzhou was introduced to Okinawa in 1828, and served as the basis from which Goju-ryu karate kempo unfolded.”

Itosu Anko.

If we are to consider what Master Miyagi told us, then it would seem that something other than just Ryuru’s tradition formed the basis from which Goju-ryu developed. Kyoda Juhatsu, the senpai (senior) of Miyagi Chojun while under the tutelage of Kanryo Sensei, said that Master Higashionna only ever referred to his discipline as quanfa (kempo), and also taught several Chinese weapons, which Miyagi Sensei never learned.

The question of whether Higashionna may have obtained a copy of the Bubishi from one of his masters in Fuzhou is the source of much discussion and it remains one of the most popular theories.

The fifth theory claims Itosu Anko (1832–1915) was the source from which the Bubishi appeared in Okinawa. Whereas Higashionna influenced the direction and development of the fighting arts in the Naha area, Itosu was responsible for handing down the other mainstream self-defense tradition, which later became known as Shurite, and possibly the Bubishi as well. His teacher, the legendary “Bushi” Matsumura Chikudun Pechin Sokon (1809–1898), had studied gongfu in both Fuzhou and Beijing and may very well have been the source from which the Bubishi first appeared in Okinawa. Mabuni Kenwa, the founder of Shito-ryu, wrote in his version of the Bubishi that he had made a copy from the copy his teacher (Itosu) had himself made. We assume that as Matsumura was his teacher, Itosu made his copy from Matsumura’s.

A sixth possibility is that the Bubishi was brought to Okinawa by Uechi Kanbun (1877–1948), the founder of Uechi-ryu. The Uechi-ryu karate-do tradition tells us Uechi went to Fuzhou in 1897, where he ultimately studied Guangdong Shaolin Temple Tiger Boxing directly under master Zhou Zihe (Shu Shiwa in Japanese).

One of Uechi Kanbun’s students, Tomoyose (Tomoyori) Ryuyu (1897–1970), an accomplished student of the fighting traditions, dedicated most of his life writing an analysis of kempo, vital point striking, and the application of Chinese herbal medicine. Entitled Kempo Karate-jutsu Hiden (Secrets of Kempo Karate-jutsu), the document, now owned by the Uechi family, addressed a number of articles identical to the Bubishi. Unfortunately Tomoyose died before he was able to complete this analysis. The similarities are too frequent to doubt that the Uechi family once possessed a copy of the Bubishi.

A seventh theory concerns two Chinese tea merchants who moved to Okinawa during the Taisho era (1912–25). Wu Xiangui (1886–1940), who was a White Crane gongfu expert, moved from Fuzhou to Okinawa in 1912. Uechi Kanbun wrote that Wu (Go Kenki in Japanese) taught gongfu in the evenings in Naha. It is claimed that he had a major influence upon Miyagi Chojun, Mabuni Kenwa, Kyoda Juhatsu,13 and Matayoshi Shinho, son of Matayoshi Shinko.14

Wu Xiangui (Gokenki).

The second tea merchant was a friend of Wu’s named Tang Daiji (he was called To Daiki in Okinawa). Tang (1887–1937) moved from China to Naha, Okinawa in 1915. In his home village, Tiger Fist gongfu was very popular and Tang had become well known for his skills. In Okinawa he befriended Miyagi Chojun and other prominent karate enthusiasts, and is said to have had a big impact upon the karate community during that time. It is possible that either of these individuals may have brought copies of the Bubishi that they in turn gave to one or more of these famous Okinawan masters.

The eighth theory concerns Nakaima Chikudun Pechin Norisato, founder of the Ryuei-ryu karate tradition. Son of a wealthy family in Naha’s Kuninda district, he was required to learn the principles of Bunbu Ryodo (the philosophy of the twin paths of brush and sword, symbolizing the importance of balancing physical training with protracted introspection and study) from an early age. He was sent to Fuzhou when he was nineteen years old. Nakaima obtained his formal introduction to Ryuru Ko from a friend of his family, a military attache who had visited the Ryukyu Kingdom in 1866 (from June 22 to November 18) as a subordinate of the Qing Sapposhi Zhao Xin. In 1870, Nakaima became an uchideshi (live-in disciple) of Ryuru Ko. After six years of sacrifice and diligent training he surfaced in 1876 as a proficient expert. Before departing from Ryuru Ko’s, he was required to make copies (by hand) of the many books he had studied. Among the most noted books were: books on etiquette, health, and Chinese medicine, and a book about cultivating a brave spirit through the practice of quanfa. Some believe that the present Okinawan Bubishi is a compilation of these documents. Nakaima spent the next year touring Guangdong Province and Beijing to further his understanding of the fighting traditions, and returned to Okinawa with an impressive collection of weapons.

The ninth theory concerns the Kogusuku or Kojo (pronounced Cai in Mandarin) clan (descendants of Naha’s Kuninda Thirty-six Families), a family long known for its martial arts heritage in Okinawa. Dating back to 1392, the family has long enjoyed ties with Fuzhou and has been connected with experts like Makabe (Udon) Kyoei, Iwah, and Wai Xinxian.15 It is said that Kojo Taitei (1837–1917), who had studied gongfu in Fuzhou, was a good friend of Higashionna Kanryo. Kojo Kaho (1849–1925) even had his own dojo in Fuzhou, where it is alleged that Wai Xinxian instructed several Okinawans and Uechi Kanbun trained for a short time before becoming Zhou Zihe’s disciple.16 Dr. Hayashi Shingo, the most senior disciple of Kojo-ryu Master Kojo Kafu (grandson of Kojo Kaho), said Kojo Taitei brought back a “secret text” on gongfu from Fuzhou upon which much of their style was based.17 It is entirely possible that this text was the Bubishi.

The tenth theory was brought to my attention by Otsuka Tadahiko,18 which I shall refer to as the “museum hypothesis.” During the Ryukyu Kingdom, an official building called the Tenson, which housed objects of historical, cultural, artistic, and scientific interest, was located next to the Sanshikan19 residence in Naha’s Kuninda district. Under this theory, the Bubishi is said to be a compilation of written gongfu precepts taught in Naha’s Chinese community and several other texts from the Tenson. Folklore says that the book later became a treasure guarded by the masters of the civil fighting traditions in Naha when the kingdom was abolished in 1879; hence, the tradition of it being passed down, copied by hand, unfolded. This theory seems unlikely, however, in light of the existence of Liu Songshan’s Shaolin Bronze Man Book—a work not associated with Okinawa, yet identical in content to the Bubishi.

It is possible that any one of these theories, or perhaps even several of them, may be true. It appears that many copies of the Bubishi were in circulation in Okinawa by the early twentieth century and not all may have been brought at the same time or in its current complete form. Nonetheless, these theories are worthy of further study and exploration not only for their relevance to the study of the Bubishi in particular but also of the history of the Okinawan civil fighting arts in general.

The History of Karate-do

The evolution of the Okinawan civil fighting arts was shaped by a number of sociological and historical factors. To comprehend how karate became the art that it is today and why the Bubishi had such a strong impact during the latter stages of its development, a knowledge of Okinawan history and society is necessary.

Through presenting karate-do’s history, I will describe the Ryukyu Kingdom’s connection with China. When exploring this history, China’s penetrating effect upon Okinawa’s tiny island culture becomes readily apparent, thus establishing the context for the advent of Chinese gongfu and arrival of the Bubishi in the Ryukyu Kingdom. This analysis will also illustrate how Chinese gongfu, evolving in a foreign culture, was affected by that culture.

Theories on the Development of Karate before the Twentieth Century

There are four common theories explaining the development of karate-do. The first claims that the unarmed fighting traditions were developed by peasants. The second claims the Okinawan fighting arts were primarily influenced by Chinese arts that were taught by the so-called “Thirty-six Families” of Chinese immigrants who settled in Kume village (also known as Kuninda) in the fourteenth century. The third theory concerns the 1507 weapons ban by King Sho Shin, which led to an increased need by wealthy landowners for an effective means of defending themselves and their property. The fourth theory claims that the arts were developed primarily by domestic security and law enforcement personnel who were not allowed to carry weapons after the 1609 invasion of Okinawa by Satsuma.

Folklore would have us believe that Okinawa’s civil fighting legacy was developed by the subjugated “pre-Meiji peasant class.” Described as tyrannized by their overlords, the peasants, in an effort to break free of the chains of “oppression,” had allegedly conceived an omnipotent fighting tradition. Some people have further hypothesized that combative principles had “somehow” been applied to the implements they used in their daily lives.

It has also been postulated that, under cover of total darkness, for fear of reprisal if caught, the peasants not only established this cultural phenomenon but also succeeded in handing it down for generations, unbeknownst to local authorities. Supported by mere threads of historically inaccurate testimony, one discovers that the “pre-Meiji Peasant Class Supposition” is not worthy of serious consideration. Nonetheless, some researchers have erroneously credited the peasant class with the development of both Okinawa’s armed and empty-handed combative traditions. However, a further study of the Ryukyu Kingdom reveals findings that suggest a more plausible explanation.

In the following sections I will study the remaining three theories as they relate to Okinawan history and will introduce several new theories, notably, the role of Okinawan tyugakusei (exchange students) and sapposhi (Chinese envoys) on the development of the Okinawan fighting arts and the influence of Japanese fighting arts.

Indigenous and Japanese Influences Prior to the Fourteenth Century

In 1816, following his expedition to the west coast of Korea and the “Great Loo-Choo” (Okinawa), Basil Chamberlain Hall, in a discussion with exiled Emperor Napoleon, described Okinawa as a defenseless, weaponless island domain. In fact, the Ryukyu Kingdom had been thoroughly familiar with the ways of war.

From before recorded history, in addition to being versed in the use of the sword, the spear, archery, and horsemanship, Okinawan warriors had a rudimentary form of unarmed hand-to-hand combat, that included striking, kicking, elementary grappling, and escape maneuvers that allowed them to subdue adversaries even when disarmed.

During the rise of the warrior cliques in tenth-century Japan, wide-scale military power struggles compelled apathetic aristocrats to intermittently seek out refuge in more tranquil surroundings. Many solicited the protection of more powerful allies, some relocated to bordering provinces, there were even those who journeyed to neighboring islands, including the Ryukyu archipelago.

Militarily dominated by local chieftain warriors (aji or anji), the Uchinanchu had actively engaged in territorial dissension from the seventh to the fifteenth centuries, and placed much value upon military knowledge. Arriving with contingents of heavily armed security personnel, Japanese aristocrats were venerated and ultimately retained the services of local soldiers. As a result of this the standard Japanese combative methodologies of the Heian Period (794–1185), including grappling, archery, halberd, spear, and swordsmanship, were introduced to the Uchinanchu.

Perhaps the most profound historical event to effect the evolution of Okinawa’s native fighting traditions was the arrival of Tametomo (1139–70). The eighth son of feudal warlord Minamoto Tameyoshi (1096–1156) and a subordinate of Japan’s once-powerful Minamoto clan, Tametomo, while still a teenager, is described in the Tales of the Hogen War (Hogen Monogatari), as a fierce warrior. A remarkably muscular and powerful man, Tametomo is said to have stood over seven feet tall and was a powerful fighter, famous for his remarkable skill in archery.

During a brief military encounter in 1156, the Minamoto clan was defeated by their rivals, the Taira, and several of the leading members of the Minamoto who were not executed were tortured and exiled to Oshima Island near the mountainous Izu Peninsula, in the custody of a minor Taira family, the Hojo. Among the exiled was Minamoto Tame-tomo, who ended up taking control of Izu many years later, and worked his way south to the Ryukyu Archipelago.

Excelling in strategy and the art of striking heavy blows, Tametomo had overrun all of Kyushu within three years. Arriving in Okinawa, at Unten (near Yagajijima Island), he made contact with Ozato Aji, lord of Urazoe Castle, and was revered for his military might. Marrying Ozato’s sister, Tametomo became lord of Urazoe and had a son he named Shunten. In 1186, Shunten defeated Riyu (the last ruler of the Tenson dynasty) and became the island’s most powerful aji. The Shunten dynasty lasted until 1253 and perpetuated the combative traditions introduced by Tametomo and his bushi (warriors).

Notwithstanding, with Okinawa being divided into three tiny kingdoms, territorial dissension continued until one powerful aji, Sho Hashi, unified the three rival principalities and formed a centralized government in 1429. Several dynasties later, in 1507, during the thirtieth year of his administration, Sho Shin-O ended feudalism in the Ryukyu Kingdom by ratifying the “Act of Eleven Distinctions,” which included a prohibition of private ownership and stockpiling of weapons. This is historically significant for researchers because it explains why the Uchinanchu began intensively cultivating an unarmed means of self-defense.

Chinese Influences on the Development of Karate-do

Okinawa’s first recorded contact with the Chinese was during the Sui dynasty in 607 A.D. However, unable to understand the Okinawan dialect (Hogan), the Chinese envoys returned without establishing substantial commerce. It was not until 1372, some four years after the Mongols fell to the powerful forces of the Ming dynasty (1368–1644), that Emperor Hong Wu sent his special representative, Yang Zai, to Chuzan, the most powerful of Okinawa’s three rival kingdoms, to establish a tributary alliance.

Landing at Maki-minato (Port Maki) during the reign of Satto (1350–95), the imperial envoy outlined China’s unification and omnipotence. The Ming representative advised Chuzan to become a tributary colony and make plans to accommodate the Chinese.

Having previously enjoyed limited, but unsanctioned, commerce with Fujian Province, Satto recognized this opportunity and ultimately welcomed the petition. Taiki, the king’s brother and special emissary, took tribute to China, where the liaison was ratified.

THE THIRTY-SIX FAMILIES

By 1393, a Chinese mission was established in Naha’s Kuninda, which is now referred to as the “Thirty-six Families.” This is important because it shows how the Chinese fighting traditions were first systematically transmitted in Okinawa.

Douglas Haring’s translation of the 1896 Takanoya Account provides an illuminating description of this arrangement.

The leading city and capital of Okinawa, Naha has absorbed various nearby villages as well as the one-time royal capital of Shuri. Kume village has played a unique role in Okinawa’s history. It was settled in 1393 by immigrants of China and provided a place where Chinese diplomats resided and where Okinawan nobles could learn the language and manners of China. Formal relations with China dated from 1372 until Japan annexed Ryukyu in the 1870s; the last Okinawan tribute mission was sent to China in 1873. For five centuries Kume served as a center of diffusion of Chinese culture in Ryukyu. Young Okinawans learned to speak and write Chinese in Kume; those who did well were accepted for study at China’s capital and received scholarships from the government of China. The enrichment of Okinawan culture via Kume was incalculable. Here men not only learned how to write Chinese and acquire literary arts, but on occasion technicians also taught ship-building, various crafts and the practicing arts, making of paper and books, lacquer ware, building and architecture, divination and festivals, Confucian morals, and Chinese music.20

The settlement at Kume has been referred to as Okinawa’s “window to Chinese culture.” It is highly likely that along with the aforementioned crafts, the Chinese martial arts were also introduced to Okinawa by the “Thirty-six Families.”

THE RYUGAKUSEI

During Okinawa’s tributary alliance with the Middle Kingdom, contingents of Uchinanchu ryugakusei (exchange students) made extended pilgrimages to various parts of China to receive an education. In many ways, the Uchinanchu ryugakusei were not unlike Japan’s kentoshi. Special envoys of the emperor, the kentoshi sought out cultural knowledge in exchange for special tribute. Between 630 and 894, the kentoshi, along with sizable entourages, made sixteen excursions to China seeking knowledge and technology to enhance their own society. Studying in Beijing, Nanjing, Shanghai, and Fuzhou, the ryugakusei, like the kentoshi, also brought valuable learning back to their homeland. It is likely that these ryugakusei learned the Chinese fighting arts and brought these back to their homeland as well.

THE SAPPOSHI

The most profound cultural influence from China came by way of the sapposhi (also pronounced sappushi or sakuhoshi), who were special envoys of the Chinese emperor. The sapposhi traveled to the outermost reaches of the emperor’s domain carrying important dispatches and returning with situation reports.

Requested by the Okinawan king, the sapposhi were sent to the Ryukyu Kingdom more than twenty times over a 500 year period, approximately once for every new king that came into power from the time of Bunei in 1404. Rarely staying longer than four to six months, the sapposhi were usually accompanied by an entourage of 400–500 people that included occupational specialists, tradesmen, and security experts. These specialists could have introduced their arts while in Okinawa and as I had noted earlier, in Nakaima Chikudun Pechin Norisato’s case (see pages 135–136), assisted Okinawans studying the Chinese fighting arts in China.

Individual preoccupation with the civil fighting traditions gradually escalated, as did domestic power struggles. Ultimately, political reform prompted the adoption of Chinese gongfu for domestic law enforcement. As a result of the official Japanese injunction prohibiting the ownership and stockpiling of weapons, government personnel were also disarmed. After the Japanese invasion, Okinawan Chinese-based civil self-defense methods became shrouded in an ironclad ritual of secrecy but continued to be vigorously cultivated by its pechin-class officials.

The Pechin in Okinawan Society

The Takanoya Account delineates the Ryukyu Kingdom’s class and rank structure.

The people are divided into eleven classes: princes, aji, oyakata, pechin, satunushi-pechin, chikudun pechin, satunushi, saka satunushi, chikudun, chikudun zashiki, and niya. Princes are the king’s brothers and uncles. Aji are (but not always) sons of the king’s uncles and brothers and are generally district chieftains; hence, during the Satsuma period, aji are not included in the shizoku (military, i.e., samurai). The Japanese have compared the aji to daimyo (feudal lords). Oyakata are upper samurai, pechin and satunushi pechin are middle samurai. The other classes were sons and brothers of upper and middle shizoku (keimochi). The niya were commoners.

There are nine ranks of shizoku. Each has its distinctive apparel and accessories. Sometimes, however, lower samurai have been selected for promotion, even to the Three Ministers. Outstanding ministers were awarded full first-rank or semi-first-rank. All other ranks are determined according to circumstances. A commoner who had served as jito (administrator of a fief) for a number of years, or who had served with a consistently good record in the office of a magiri (also written majiri; originally the territory or village controlled by an aji) could be appointed to chikudun status. If exceptionally competent, he might be elevated to chikudun pechin rank, although he could not become a samurai or wear a haori coat or tabi (split-toed socks).21

The pechin served from 1509 to 1879, starting from when Sho Shin imposed a class structure upon the gentry, until the dynasty was abolished. The pechin officials were largely responsible for, but not limited to, civil administration, law enforcement, and related matters. The pechin class was divided into satunushi and chikudun. The satunushi were from gentry while the chikudun were commoners. These two divisions were even further divided into ten subcategories based upon seniority.

Administrative aspects of law and order were governed by senior officials at the okumiza bureau, which incorporated a police department, prosecutors, and a court system. The hirasho (also hirajo), that era’s version of a city hall, which was located within Shuri castle, had two specific functions: maintaining the family register system that kept the records of all births and deaths, and investigating peasant criminal activities. Outlying districts had smaller bureaus, called kogumiza, and often served as territorial or self-governing hirajo.

The Ryukyu Kingdom’s judiciary system engaged the services of bailiffs who served writs and summonses, made arrests, took custody of prisoners, and ensured that court sentences were carried out. These chikusaji pechin, or “street-cops” so to speak, enforced the law while the hiki (garrison guard), provided military defense, guarded the castle, and protected the king. It was these officers who were responsible for cultivating and perpetuating the development of unarmed self-defense disciplines.

In 1507, nearly 100 years before the private ownership and stockpiling of swords and other weapons of war was ever contemplated on Japan’s mainland, Sho Shin, in the thirtieth year of his reign, enacted such a decree in the Ryukyu Kingdom. One hundred and fifty years before Tokugawa Ieyasu (the first shogun of the Edo bakufu) ever compelled his own daimyo to come to Edo (Tokyo), Sho Shin commanded his aji to withdraw from their fortresses and reside at his side in the castle district of Shuri, hence strengthening his control over them. Nearly a century before the Edo keisatsu (policemen of the Tokugawa period, 1603–1868) ever established the civil restraint techniques using the rokushaku bo and the jutte (iron truncheon), the Ryukyu pechin-class officials had already cultivated a self-defense method based upon the principles of Chinese gongfu.

The Satsuma Invasion

Having supported Toyotomi Hideyoshi’s failed campaigns on the Korean peninsula and then later being defeated at Sekigahara by Tokugawa Ieyasu’s forces, Shimazu Yoshihisa (the sixteenth-generation leader of the Kyushu-based Satsuma clan) had drawn heavily upon his subordinates, but without reward. With financial resources unstable and his warriors’ morale sinking, invading the prosperous Ryukyu Kingdom began to look like a sure way for Shimazu to resolve his financial difficulties and appease the Tokugawa Shogun.

In February 1609, the Satsuma clan began its campaign against the Ryukyu Kingdom. In May, Shuri castle was captured and King Sho Nei surrendered. Satsuma control lasted nearly three centuries until 1879, when King Sho Tai abdicated and the island officially became part of the Japanese empire.

“Bushi” Matsumura Chikudun Pechin Sokon.

During Okinawa’s 270-year military occupation, eclectic fighting traditions haphazardly evolved, some of which applied the principles of self-defense to a myriad of domestic implements. It was largely because of this phenomenon that kobudo evolved. During the occupation, there were some pechin who traveled up to Satsuma. Evidently while there, some of these stalwarts were schooled in Jigenryu ken-jutsu (the combative methodology of the Satsuma samurai), and, in so doing, affected the evolution of Okinawa’s “indigenous” fighting methods upon returning to their homeland.

In Okinawa, this theory is rarely addressed, and yet, kobudo tradition maintains that the rokushaku bo-jutsu (the art of using a six-foot staff) of “Toudi” Sakugawa Chikudun Pechin Kanga and Tsuken Chikudun Pechin Koura (1776–1882) did not surface until after they returned to Okinawa from studying in Satsuma. To corroborate this important historical hypothesis, I would like to draw the reader’s attention to two other independent sources.

Among the many pechin to make the journey from the Ryukyu Kingdom to Satsuma during the later part of the nineteenth century was Matsumura Chikudun Pechin Sokon. Perhaps better known as “Bushi” Matsumura, he came to be known as the Miyamoto Musashi of the Ryukyu Kingdom. In many ways, Matsumura is considered the “great-grandfather” of the karate movement that surfaced in and around Shuri. Matsumura first learned the native Okinawan fighting traditions under the watchful eye of “Toudi” Sakugawa and later, while serving as a security agent for three consecutive Ryukyuan kings, studied in both Fujian and Satsuma. Also as I noted earlier (see p. 130), he studied under the gongfu Master Iwah.

Receiving his menkyo (teaching certificate) in Jigen-ryu ken-jutsu from Ijuin Yashichiro, Matsumura was responsible for synthesizing the unique teaching principles of Jigen-ryu to the Chinese and native Okinawan fighting traditions he had also studied. By doing so, Matsumura established the cornerstone upon which an eclectic self-defense tradition surfaced in and around the castle district, which in 1927 became known as Shuri-te (Shuri hand).

After retiring from public service, Matsumura was one of the very first to begin teaching his self-defense principles in Shuri’s Sakiyama village. His principal disciples included Azato Anko (1827–1906), Itosu Anko (1832–1915), “Bushi” Ishimine (1835–89), Kiyuna Pechin (1845–1920), Sakihara Pechin (1833–1918), Matsumura Nabe (1850–1930), Tawada Pechin (1851–1907), Kuwae Ryosei (1858–1939), Yabu Kentsu (1866–1937), Funakoshi Gichin, Hanashiro Chomo (186–1945), and Kyan Chotoku (1870–1945).

In Volume Eight of the Japanese encyclopedia Nihon Budo Taikei there is a provocative passage on page 51 that provides an interesting explanation of the origins of the Ryukyu Kingdom’s fighting traditions. The passage notes that Lord Shimizu instructed second-generation Jigen-ryu headmaster Togo Bizen no Kami Shigekata (1602–59) to teach self-defense tactics to farmers and peasants in Satsuma. This was done so that in case of an invasion, these farmers could act as a clandestine line of defense for their homeland. This non-warrior tradition was disguised in a folk dance called the Jigen-ryu Bo Odori, and incorporated the jo (three-foot staff) against the sword; the rokushaku bo against the spear; and separate disciplines employing an eiku (boat oar), the kama (sickles), shakuhachi (flute), and other implements.

This phenomenon clearly illustrates how the principles of combat were ingeniously applied to occupationally related implements and then unfolded into a folk tradition, not unlike that of Okinawa’s civil combative heritage nearly a century before. When I asked the eleventh-generation Jigen-ryu headmaster Togo Shigemasa about this potential link, he said, “There can be no question that Jigenryu is connected to Okinawa’s domestic fighting traditions; however, the question remains, which influenced which!”22

The Satsuma period was one of great growth and development for both Okinawan karate-do and kobudo. However, the fundamental character and form of these fighting traditions were to undergo an even more radical change after Okinawa became a part of Japan and its proud warrior heritage.

History of Karate-do from the Meiji Era

After the abolition of the Tokugawa Shogunate in 1868, the Meiji Restoration delivered Japan from feudalism into “democracy.” Hence, the class structure and the samurai practice of wearing of swords, samurai yearly stipends, and the chonmage (top-knot hair-style), faded into the annals of history, as did many of the other social phenomena that symbolized feudalism’s authoritarian forces. However, unable to abruptly escape the powerful strain of machismo under which Japan had evolved and fearful of losing its homogeneous identity in the wake of foreign influence, many of modern Japan’s fundamental elements still reflected its feudal-based ideologies. Perpetuating old traditions while encouraging the development of many new social pastimes and cultural recreations, bugei (martial arts) became an instrumental force in shaping modern Japanese history.

Based upon ancient customs, inflexible ideologies, and profound spiritual convictions, Japan’s modern budo (martial ways) phenomenon was more than just a cultural recreation. In its new sociocultural setting, budo served, in many ways, as yet another channel through which the ruling elite could funnel kokutai (national polity), introduce the precepts of shushin (morality), and perpetuate Nihonjinron (Japaneseness). Based upon sport and recreation, the modern budo phenomena fostered a deep respect for those virtues, values, and principles revered in feudal bushido (the way of the warrior), which fostered the willingness to fight to the death or even to kill oneself if necessary. Both kendo and judo encouraged shugyo (austerity) and won widespread popularity during this age of escalating militarism.

Supported by the Monbusho (Ministry of Education), modern budo flourished in Japan’s prewar school system. Embraced by an aggressive campaign of militarism, modern budo was often glamorized as the way in which “common men built uncommon bravery.” Be that as it may, judo, kendo, and other forms of modern Japanese budo during the post-Edo, pre-World War II interval, served well to produce strong, able bodies and dauntless fighting spirits for Japan’s growing war machine.

Ryukyu Kempo Karate-jutsu

With the draft invoked and Okinawa an official Japanese prefecture, the military vigorously campaigned for local recruits there. In 1891, during their army enlistment medical examination, Hanashiro Chomo (1869–1945) and Yabu Kentsu (1866–1937) were two of the first young experts recognized for their exemplary physical conditioning due to training in Ryukyu kempo toudi-jutsu (karate-jutsu).

Yabu Kentsu.

Hence, the mere possibility that this little-known plebeian Okinawan fighting art might further enhance Japanese military effectiveness, as kendo and judo had, a closer study into the potential value of Ryukyu kempo karate-jutsu was initiated. However, the military ultimately abandoned this idea due to a lack of organization, impractical training methods, and the great length of time it took to gain proficiency. Although there is little testimony to support (or deny) allegations that it was developed to better prepare draftees for military service, karate-jutsu was introduced into Okinawa’s school system (around the turn of the twentieth century) under the pretense that young men with a healthy body and moral character were more productive in Japanese society.

Around the turn of the twentieth century, a small group of local Okinawan karate enthusiasts led by Itosu Anko established a campaign to introduce the discipline into the island’s school system as a form of physical exercise. Itosu’s crusade to modernize karate-jutsu led to a radical revision of its practice.

Removing much of what was then considered too dangerous for school children, the emphasis shifted from self-defense to physical fitness through group kata practice, but neglected its bunkai (application). By not teaching the hidden self-defense moves, the actual intentions of the kata (e.g., to disable, maim, and or even kill by traumatizing anatomically vulnerable areas if necessary) became so obscured that a new tradition developed.

This radical period of transition represented the termination of a secret self-defense art that embraced spiritualism and the birth of a unique recreational phenomenon. This creation was introduced to mainland Japan, where it ultimately conformed to the forces of Japanese society and evolved in a completely new direction.

Japanization of Karate

Konishi Yasuhiro (1893–1983), a ju-jutsu expert and prominent kendo teacher, had studied Ryukyu kempo karate-jutsu before it was formerly introduced to mainland Japan. Later, he studied directly under Funakoshi Gichin, Motobu Choki (1871–1944), Mabuni Kenwa, and Miyagi Chojun. When comparing it to judo and kendo, Konishi described karate-jutsu as an incomplete discipline. With Otsuka Hironori (1892–1982), the founder of Wado-ryu ju-jutsu kempo karate-do, Konishi was largely responsible for initiating the modernization movement that revolutionized Ryukyu kempo karate-jutsu on Japan’s mainland.

Konishi quite frankly said that modern karate was forged in the exact image of kendo and judo. The ancient samurai warrior’s combative ethos, which was based on the various schools of ken-jutsu (swordsman-ship) and ju-jutsu (grappling), provided the very infrastructure upon which the modern budo phenomenon evolved. Using the fundamental concepts of ken-jutsu’s most eminent schools, kendo was established; jujutsu’s central principles served as the basis upon which judo unfolded.

The Japanese proverb deru kugi wa utareru (a protruding nail gets hammered down) aptly describes how things or people that are “different” (i.e., not in balance with the wa23 or harmony principle) ultimately conform or are methodically thwarted in Japanese society. As a result karate was not able to escape Japan’s omnipotent cultural forces. In contrast to kendo and judo, the karate-jutsu movement lacked a formal practice uniform and had no competitive format. Its teaching curricula varied greatly from teacher to teacher and there was no organized standard for accurately evaluating the varying grades of proficiency. When compared to kendo and judo, the humble discipline of Ryukyu kempo karate-jutsu remained, by Japanese standards, uncultivated and without suitable organization or “oneness.” In short, it was not Japanese. Ryukyu kempo karate-jutsu was thus subject to the criticism of rival and xenophobic opposition during that early and unsettled time of transition when it was being introduced to the Japanese mainland during the 1920s and 1930s.

The period of transition was not immediate nor was it without opposition. It included a justification phase, a time when animosities were vented and the winds of dissension carried the seeds of reorganization. It was a time in which foreign customs were methodically rooted out (Uchinanchu were openly discriminated against and anti-Chinese sentiment was rampant) and more homogeneous concepts introduced.

The Dai Nippon Butokukai

Representing centuries of illustrious cultural heritage, the Butokukai’s (Japan’s national governing body for the combative traditions) ultra-traditional bugei and budo cliques were deeply concerned about the hostilities being openly vented between rival karate leaders. This, coupled with the disorganized teaching curricula, lack of social decorum, and absence of formal practice apparel, compelled the Butokukai to regard the escalating situation as detrimental to karate-jutsu’s growth and direction on the mainland and set forth to resolve it.

The principal concern focused not only upon ensuring that karate teachers were fully qualified to teach, but also that the teachers actually understood what they were teaching. For karate-jutsu to be accepted in mainland Japan, the Butokukai called for the development and implementation of a unified teaching curriculum, the adoption of a standard practice uniform, a consistent standard for accurately evaluating the various grades of proficiency, the implementation of Kano Jigoro’s dankyu system, and the development of a safe competitive format through which participants could test their skills and spirits. Just as 12 inches always equals one foot, the plan was to establish a universal set of standards, as judo and kendo had done.

The Kara of Karate-do

No less demanding were the powerful forces of nationalism combined with anti-Chinese sentiment. Together, they propelled the karate-jutsu movement to reconsider a more appropriate ideogram to represent their discipline rather than the one that symbolized China. In making the transition, the Ryukyu kempo karate-jutsu movement would also abandon the “-jutsu” suffix and replace it with the modern term “do,” as in judo and kendo.

The original ideograms for karate meant “China Hand.” The initial ideogram, which can be pronounced either “tou” or “kara,” stood for China’s Tang dynasty (618–907), and later came to represent China itself. The second ideogram, meaning “hand,” can be pronounced either “te” or “di.” Master Kinjo Hiroshi24 assured us that, until World War II, the Uchinan karate masters generally referred to karate as “toudi.”

Kinjo’s teacher, Hanashiro Chomo, a direct disciple of “Bushi” Matsumura, made the first recorded use of an ideogram to replace the “China” ideogram in his 1905 publication Karate Kumite. This unique ideogram characterized a self-defense art using only one’s “empty” hands to subjugate an adversary. The new character for kara meant “empty” and can also be pronounced “ku” (void) and “sora” (sky). As such, kara not only represented the physical but also embraced the metaphysical; the deeper plane of an ancient Mahayana Buddhist doctrine surrounding detachment, spiritual emancipation, and the world within (inner void). During the pursuit of inner discovery, kara represents the transcending of worldly desire, delusion, and attachment.

The suffix “-do,” which is found in kendo, judo, and budo, means “way,” “path,” or “road.” The same character is also pronounced “dao” in Mandarin and is most notably used for the Daoist philosophy of Lao Zi, the reputed author of the Dao De Jing. In the philosophical context adopted by the self-defense traditions, the do became a “way” of life, a “path” one travels while pursuing karate’s goal of perfection. The ideogram “jutsu” in karate-jutsu meant “art” or “science.”

As such, the new ideograms proclaimed that Okinawa’s plebeian discipline of karate-jutsu had transcended the physical boundaries of combat and had become a modern budo after embracing that which was Japanese. Like other Japanese cultural disciplines, karate-do became another vehicle through which the Japanese principle of wa (harmony) was funneled. Thus, the innovative term “karate-do” (the way of karate) succeeded the terms toudi-jutsu and karate-jutsu.

While the new term “karate-do,” using the two new ideograms (kara and do), was not officially recognized in Okinawa until 1936, it was ratified by the Dai Nippon Butokukai in December 1933, finally signaling karate-do’s recognition as a modern Japanese budo.

Today, most historians conclude that Ryukyu kempo karate-jutsu, as introduced to the mainland in those early days, was at best an effective but unorganized plebeian self-defense method. The Butokukai concluded that the improvements it called for would bring about a single coalition under their auspices, like that of judo and kendo. However, karate-do development was overshadowed by the destruction of World War II, so much so that a universal set of standards failed to materialize.

Many believe that when the Butokukai and other organizations considered contributors to the roots of militarism were dissolved in 1945 after Japan unconditionally surrendered to the Allied forces, karate-do development as a unified discipline was abandoned. However, like judo and kendo, karate-do did come to enjoy an untold popularity through the sport format that was born in the school system.

In spite of karate-do’s popularity, differences of opinion, personal animosities, and fierce rivalries clearly showed that karate-do was destined to maintain its divided individuality. While a myriad of eclectic interpretations unfolded—many of which shared similarities—karate-do styles were never really brought together to form a single tradition. This is a phenomenon that, for better or worse, continues to this day.

Okinawan Dynasties

Island folklore maintains that the Tensonshi (lit. “the grandchildren from heaven”) governed the Ryukyu archipelago for twenty-five generations before Shunten.

Tametomo (1139–70), the eighth son of Tameyoshi and a subordinate of Japan’s once powerful Minamoto clan, was exiled to Oshima Island but escaped and ultimately made his way to the Ryukyu Islands. There he married and had a son, Shunten. Shunten defeated Riyu (the last ruler of the Tenson) and became the island’s first king in 1186.

The Shunten dynasty (1186–1253) Shunten (1186–1237) Shumma-junki (1238–48) Gihon (1249–59) Eiso dynasty (1260–1349) Eiso (1260–99) Taisei (1300–8) Eiji (1309–13) Tamagusuku (1314–36) Seiji (1337–49) Satto dynasty (1349–1407) Satto (1350–95) Bunei (1396–1405) First Sho dynasty (1407–69) Sho Shiso (1406–21) Sho Hashi (1422–39) Sho Chu (1440–44) Sho Shitatsu (1445–49) Sho Kinfuku (1450–53) ShoTaikyu (1454–60) ShoToku (1461–68) The Second Sho dynasty (1470–1879) Sho En (1470–76) Sho Seni (1477) Sho Shin (1477–1526) Sho Sei(1527–55) Sho Gen (1556–72) Sho Ei (1573–88) Sho Nei (1589–1620) Sho Ho (1621–40) Sho Ken (1641–47) Sho Shitsu (1648–68) Sho Tei (1669–1709) Sho Eki (1710–12) Sho Kei (1713–51) Sho Boku (1752–94) Sho On (1795–1802) Sho Sei (1803) ShoKo (1804–34) Sho Iku (1835–47) Sho Tai (1848–79)

NOTES:

1. In the English translation, Funakoshi’s Chapter Six “Vital Points of the Human Anatomy” is quite clearly based on the data presented in the Bubishi. The “Eight Important Phases of Karate” and the five sentences that follow them are taken word-for-word from the Bubishi’s “Eight Precepts of Quanfa” (Article 13) and “Maxims of Sun Zi” (Article 15). Similarly the mislabeled “Chinese kambum” that appear on the next page (which were left untranslated) are none other than “The Principles of the Ancient Law” (Article 14) and “Grappling and Escapes” (Article 16), as they appear in Chinese in the Bubishi.

2. Having met Liu Yinshan’s brother, Liu Songshan, in Fuzhou, I came to learn of a “secret book” on gongfu that had been in the Liu family for the last seven decades. After meeting him in Fuzhou, hosting him at my home in Japan, and visiting him in Taiwan, I have become familiar with that book, entitled the Secret Shaolin Bronze Man Book, and can testify that it is, in almost every way, identical to the Bubishi. Master Liu’s Bubishi is divided into seventeen articles in three sections, whereas the Okinawan Bubishi contains 32 articles; however, the same data is covered in both works though it is categorized differently.

3. In an interview at Tokashiki Iken’s dojo in Naha in August 1994.

4. British karate historian Harry Cook noted that Robert W. Smith, in his book Chinese Boxing: Masters and Methods (Kodansha International, Tokyo, 1974), refers to a “secret book” that was made and given to the twenty-eight students of Zheng Lishu. Zheng (also spelt Chen) is described as the servant and disciple of Fang Qiniang by Robert W. Smith, but is described as a third-generation master in Liu Yinshan’s book, after Zeng Cishu. Notwithstanding, I was able to confirm that a disciple of Zheng’s named P’eng passed on a copy of the book to Zhang Argo who along with three other White Crane gongfu experts—Lin Yigao, Ah Fungshiu, and Lin Deshun—immigrated to Taiwan in 1922. While Zhang Argo’s copy was passed on to his son Zhang Yide (spelled Chang I-Te in R.W. Smith’s book), Master Lin Deshun, one of the four original Fujian gongfu experts, passed his copy of that secret book down to his disciple Liu Gou, the father of Liu Songshan. It has remained a treasure of the Liu family for the seven decades that have passed since then.

5. Another theory suggests that Sakugawa did not study directly with Kusankun but rather learned the principles of that system from Yara Guwa (AKA Chatan Yara). There are three birth and death dates for Sakugawa: 1733–1815, 1762–1843, and 1774–1838. The first date is used in most texts as it makes possible the pervading theory of Sakugawa’s direct study with Kusankun. The second date was suggested by Nakamoto Masahiro, a student of Choshin Chibana and Taira Shinken, and founder of the Bunbukan Shuri-te School. The third date was given by Sakugawa Tomoaki (Sakugawa’s seventh-generation descendant) in the Nihon Budo Taikei, Volume Eight. One other fact supporting this theory concerns the kata Kusanku. “Bushi” Matsumura Chikudun Pechin Sokon taught only one Kusanku kata, Yara Kusanku. This title would seem to indicate a link with Yara Guwa.

6. As we know, from Mabuni Kenwa’s testimony, that Itosu Anko possessed a copy of the Bubishi, we can only speculate whether it was his teacher “Bushi” Matsumura Chikudun Pechin Sokon, or his teacher’s teacher, “Toudi” Sakugawa, who introduced this text to the Shuri-te lineage.

7. The Nakaima family tells an interesting story about Ryuru Ko’s visit to Okinawa in 1914. Apparently on the day he arrived, one of his former students, Sakiyama Kitoku from Naha’s Wakuta village (a man renowned for his remarkable leg maneuvers, who had traveled to Fuzhou and trained under Ryuru with Norisato), was on his deathbed. Upon being informed of Kitoku’s grave condition, Ryuru demanded to be taken to his home immediately. Arriving too late, Ryuru said, “If he had had a pulse remaining, I would have been able to save him.”

8. In an article in the 1993 special commemorative publication for the tenth anniversary festival for the Fuzhou Wushu Association, I discovered a biography of the White Crane Master Xie Zhongxiang (1852–1930). I had come across Xie’s name during my earlier interviews with Master Liu Songshan and Master Kanzaki Shigekazu (second-generation master of To-on-ryu and a respected karate historian). Upon more closely examining the biography of Xie Zhongxiang (provided by Wu Bin, the director of the Wushu Institute of China), I discovered that Xie was a shoemaker from Fuzhou’s Changle district, and the founder of the Whooping Crane style of gongfu. In examining the five quan (kata) of Whooping Crane gongfu, I discovered that two of them were among the six quan described in the Bubishi; Happoren and Nepai. I also discovered, in a newsletter from Tokashiki Iken, that Xie’s nickname was Ryuru, a fact corroborated by Master Kanzaki.

9. A student of Aragaki Seisho (from Kuninda) named Tomura Pechin demonstrated Pechurrin (Suparinpei), on March 24, 1867 during a celebration commemorating the March 1866 visit of the Sapposhi Xhao Xin at Ochayagoten, which is Shuri Castle’s east garden. We know that Suparinpei, Seisan, and Sanchin kata had been handed down in Kuninda long before Higashionna went to China. As the Seisan and Peichurrin are not practiced in the system Ryuru Ko taught, it would seem that Higashionna learned them from Aragaki Seisho. Other kata not taught in Ryuru Ko’s system include Sanseiryu, Saifua, Kururunfa, and Sepai, which he may have learned from one of the Kojos, Wai Xinxian, or even Iwah.

10. In an interview at Tokashiki Iken’s dojo in Naha in August 1994.

11. Not all researchers are of the opinion that Xie Zhongxiang is the man who taught Higashionna Kanryo. Okinawan karate historian Kinjo Akio and Li Yiduan believe that a different man with the same nickname was Higashionna’s teacher. They claim that Xie and Kanryo were too close in age; that Higashionna referred to Ryuru Ko as an “old man.” Based on Higashionna’s statement that Ryuru Ko was a bamboo craftsman who lived in a two-story house, they said that Xie, a shoemaker, must be a different person.

I disagree with these points for several reasons. In light of existing evidence, the age gap argument does not hold water. There is no evidence to show that Higashionna ever said that Ryuru Ko was an old man. Though Xie Zhongxiang was a shoemaker, his father was a bamboo craftsman who lived in a two-story house. I think the facts became confused over the years but remain convinced that Xie Zhongxiang taught Higashionna Kanryo.

12. The fact that Iwah definitely taught Matsumura and Higashionna’s teacher Kojo, indicated a link between the traditions that evolved in Naha and Shuri. If Higashionna also studied with Iwah, then the link would be that much closer.

13. An interesting point brought to my attention by Master Kanzaki Shigekazu. He said that the Nepai quan (see Article 7, p. 260) descended directly from Fang Qiniang, and was taught to his teacher, Master Kyoda Juhatsu, by Go Kenki. Given the time frames surrounding the advent of the Bubishi in Okinawa we must not overlook Go Kenki as a plausible source from which the secret text may have appeared.