Strategy and Technique in the Bubishi

The Bubishi is a text primarily on Yongchun White Crane and Monk Fist Boxing, two of the primary forms of Chinese gongfu that served as the foundation upon which modern karate-do was developed. As such this text contains a considerable amount of data on the self-defense techniques, forms, and strategies used in those arts.

Gongfu Quan

The quan (kata in Japanese) of Chinese gongfu is the ritualized method through which the secrets of self-defense have been customarily transmitted for generations. Each quan addresses a myriad of conceivable self-defense scenarios, but is more than just a long combination of techniques. Rather, each quan is a unique tradition unto itself with distinct principles, strategies, and applications. The applications of the forms were intended for use in life-and-death self-defense situations and as such can be used to restrain, hurt, maim, or even kill one’s opponent when necessary.

A second but equally important aspect of the quan is its therapeutic use. The various animal-imitating paradigms and breathing patterns used were added to improve blood circulation and respiratory efficiency, stimulate qi energy, stretch muscles while strengthening them, strengthen bones and tendons, and massage the internal organs. Performing the quan also develops coordination as one vibrates, utilizes torque, and rotates the hips. This in turn will improve one’s biomechanics and allow one to have optimum performance while utilizing limited energy.

Through regulating the breath and synchronizing it with the expansion and contraction of muscular activity, one oxygenates the blood and learns how to build, contain, and release qi energy. Qi can have a significant therapeutic effect on the body both internally and externally.

Master Wu Bin of China’s Gongfu Research Institute describes the quan as vitally important for mobilizing and guiding the internal circulation of oxygen, balancing the production of hormones, and regulating the neural system. When performing the quan correctly one should energize the body and not strain excessively. In rooted postures, the back must be straight, shoulders rounded, chin pushed in, pelvis tilted up, feet firmly planted, and the body kept pliable, so that energy channels can be fully opened and the appropriate alignments cultivated.

Many people impair their internal energy pathways through smoking, substance abuse, poor diet, inactivity, and sexual promiscuity.

The unique group of alignments that are cultivated by orthodox quan open the body’s pathways, allowing energy to flow spontaneously. The qi can then cleanse the neural system and regulate the function of the internal organs.

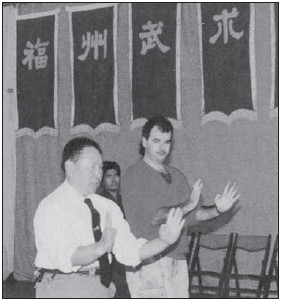

Whooping Crane Grandmaster Jin Jingfu with the author in Fuzhou.

In short, regular practice of the quan will develop a healthy body, fast reflexes, and efficient technique, helping to prepare one to respond more effectively in potentially dangerous situations.

Qin Na

Before the stylistic methods of gongfu were ever codified in China, qin na (meaning to catch or seize and hold or control) served as the very first form of self-defense. Although a compilation of self-defense skills that includes many lethal techniques, qin na is an art that strives to control an adversary without seriously injuring or killing him. Qin na practitioners will hurt rather than be hurt, maim rather than be maimed, and kill rather than be killed.

Qin na brings together techniques of twisting bones, locking joints, and separating tendons from bone; the seizing, manipulation, and striking of nerve plexuses, arteries, and other anatomically vulnerable locations; chokes and strangles; organ-piercing blows; grappling, take-downs, throws, counters, escapes, and combinations thereof. Qin na applications were not developed for use in the sports arena or in many cases against experienced trained warriors. In fact many of the qin na applications were designed for use on attackers unaware of the methods being used on them.

The hallmark of any orthodox gongfu style is the characteristics of their animal quan and the interpretation of its qin na principles. Based on the self-defense experiences of the style’s originator, the application of qin na principles vary from style to style. In gongfu, qin na represents the application for each technique in each quan. In toudi-jutsu these techniques came to be called bunkai.

Modern Japanese karate-do has popularized other terms to describe specific components of bunkai in recent times: torite (tuidi in Okinawan Hogan), to seize with one’s hands; kyusho-jutsu, vital point striking; tegumi, grappling hands; kansetsu waza, joint locks and dislocations; shime waza, chokes and strangulations; and atemi waza, general striking techniques.

Before commencing with the presentation of the articles related to fighting techniques and forms, I thought it appropriate to present a capsulized history and study of the distinctive techniques of six systems practiced in Fujian that are relevant to the Bubishi.

Capsule History of Fujian Gongfu Styles

He Quan or Crane Boxing is the general name for five styles of crane-imitating fighting arts. The five styles are: Jumping Crane, Flying Crane, Whooping Crane, Sleeping Crane, and Feeding Crane, all of which have a history of about three hundred years. However, these five styles were not completely stylized until toward the end of the Qing dynasty (1644–1911). I will also include a brief description of Monk Fist Boxing (Luohan Quan).

Jumping Crane (Zonghe Quan)

During the reign of Emperor Tong Zhi (1861–75) of the Qing dynasty, Fang Shipei, a native of Fujian’s Fuqing county, went to learn gongfu at the Tianzhu Temple on Mount Chashan. Having studied the principles of fighting for ten years, Fang concluded that the quivering movements of birds, fish, and animals were a natural way of generating more energy. Hence, he employed the principles of body vibration when he developed the Jumping Crane style. His principal disciples included Lin Qinnan and the five brave generals of Fujian: Fang Yonghua, Chen Yihe, Xiao Kongepei, Chen Daotian, and Wang Lin.

Jumping Crane gongfu is a perfect example of a style that best utilizes the principles of qin na. Jumping Crane Boxing, like Monk Fist Boxing, also hides its intentions in its quan, and it includes the seizing and dislocating of opponent’s joints, grappling, strangulations, and striking vital points. It is fast and slow, hard and soft, and makes use of the open palm and tips of the fingers. Like Whooping Crane Boxing, it advocates leg maneuvers and body movement to avoid direct assaults, and predetermined responses are aimed at traumatizing specific vulnerable areas of an opponent’s body. Breathing exercises (qigong), and vigorous shaking of the hands and torso, representing the quivering of birds, fish, and animals, are readily apparent in Jumping Crane Boxing.

Whooping Crane (Minghe Quan)

The history of Minghe Quan can be traced back to Yongchun He Quan or Crane Boxing. In the later part of the Qing dynasty, Lin Shixian, a master of White Crane gongfu from Yongchun village, relocated to Fujian’s thriving port city of Fuzhou, where he taught this style. Among his most noted disciples was Pan Yuba, the man responsible for teaching Xie Zhongxiang. It is said that Xie, in addition to mastering the rudiments of Yongchun White Crane gongfu, was also proficient in several other kinds of boxing. Combining the central elements of Yongchun He Quan with his own concepts of fighting, Xie developed a hybrid form of Crane Boxing called Minghe Quan, or Whooping Crane gongfu, also referred to as Singing or Crying Crane gongfu.

Whooping Crane Boxers derive their name from the high-pitched sound that they emit when performing some of their quan. The style also emphasizes forceful palm techniques, the 72 Shaolin seizing techniques, striking the 36 vital points, the use of qi energy, and body movement.

Sleeping Crane (Suhe Quan)

Becoming a recluse, Lin Chuanwu from Fuzhou’s Chengmen district studied Crane Boxing at Shimen Temple in Fujian. After five years of dedicated training under Monk Jue Qing, he went back to Fuzhou and established his own school.

Sleeping Crane Boxing stresses deceiving the opponent by pretending to be half asleep. Its actions are meant to be fast and hidden, its hand techniques forceful, and footwork steady and sound. Sleeping Crane imitates the sharp clawing actions of the crane and uses the strength of the opponent against him.

Feeding Crane (Shihe Quan)

Ye Shaotao of Fuzhou’s Changshan district had studied Feeding Crane gongfu from Fang Suiguan, master boxer of Beiling, at the end of the Qing dynasty and the beginning of the Republic of China (1912–49). Enhancing his overall understanding of how to attack the 36 vital points, Ye also learned from the prominent Tiger Boxer Zhou Zihe before he declared himself the master of the Feeding Crane style.

Feeding Crane Boxers pay special attention to hooking, clawing, and striking with the fingertips and palms. Principally employing the steady three-point and five plum blossom stances, Feeding Crane focuses upon single-handed attacks.

Flying Crane (Feihe Quan)

In the middle of the Qing dynasty, Zheng Ji learned the rudiments of Yongchun White Crane gongfu from third-generation Master Zheng Li. Later Zheng Ji became well known in and around the Fuqing and Qingzhou districts for his skills in gongfu.

Flying Crane Boxers rove around in circles with their bodies and arms relaxed, building power and energy before passing it to their shivering hands, which are held out straight. Imitating the flight of the crane, Flying Crane Boxers also leap about, stand on one leg, and extend their arms like the bird flapping its wings. Flying Crane Boxers use pli-ability to overcome strength; when an opponent is powerful, they employ power to the contrary.

Monk Fist (Luohan Quan)

Because Monk Fist gongfu (sometimes referred to as Arhat Boxing) has had such a profound impact upon the evolution of karate-do I have decided to also include its capsule history. Based on the embryonic Indian exercises introduced by the Buddhist missionary monk Bodhidharma at the Shaolin monastery, Luohan Quan is based upon 24 defensive and offensive techniques contained in 18 combative exercises cultivated and practiced by Shaolin recluses. Monk Fist Boxing emphasizes physical strength, and knuckle and forearm development.

Basic training centers around cultivating qi and strength by training in hourglass (saam chien) and horse stances. In addition to fostering a healthy body and thwarting illness, Monk Fist gongfu has six quan that specialize in striking vital points with the fist, two for striking with the palms, one for using one’s elbows, four quan for foot and leg maneuvers, and five grappling quan. Over the generations nine more exercises evolved from the original 18 quan, forming a total of 27, which were further divided into two parts constituting 54 separate skills. Disciples were required to master the application of these 54 skills on both sides, thus totaling 108.

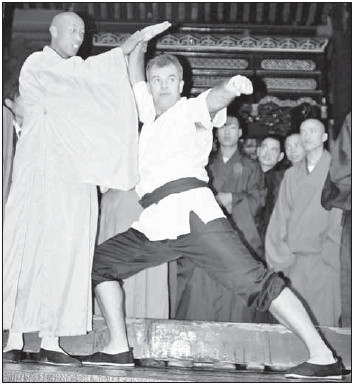

The author at the Henan Shaolin Temple with Abbot Si Yanpu.

Arhat Boxers hide their intentions in their quan, but are proficient in striking vital points, dislocating joints, grappling and strangulations, breathing exercises, and learn other related concepts, including herbal medicine and moral precepts. The nucleus of the system includes 72 seizing and grappling techniques and how to strike the 36 vital points.

The historical information above has been corroborated by Wu Bin, director of the Wushu Research Institute of China, Li Yiduan and Chen Zhinan of the Fuzhou Wushu Association, Tokashiki Iken, director of the Okinawan Goju-Tomari-te Karate-do Association, Otsuka Tadahiko, director of the Gojukensha, and Master Liu Songshan of Feeding Crane gongfu. (TR)

Articles on Fighting Techniques

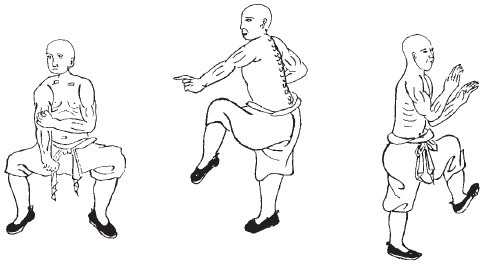

Article 6: Four Quan of Monk Fist Boxing

Techniques of the First Quan

Techniques of the Second Quan

Techniques of the Third Quan

Techniques of the Fourth Quan

If you have a teacher, you should build a training place where you can invite him to discuss his secrets and guide the disciples. Disciples should obey and do their best to provide for the teacher’s needs.

The application of a number of these techniques can be found in Article 29 (see p. 268). (TR)

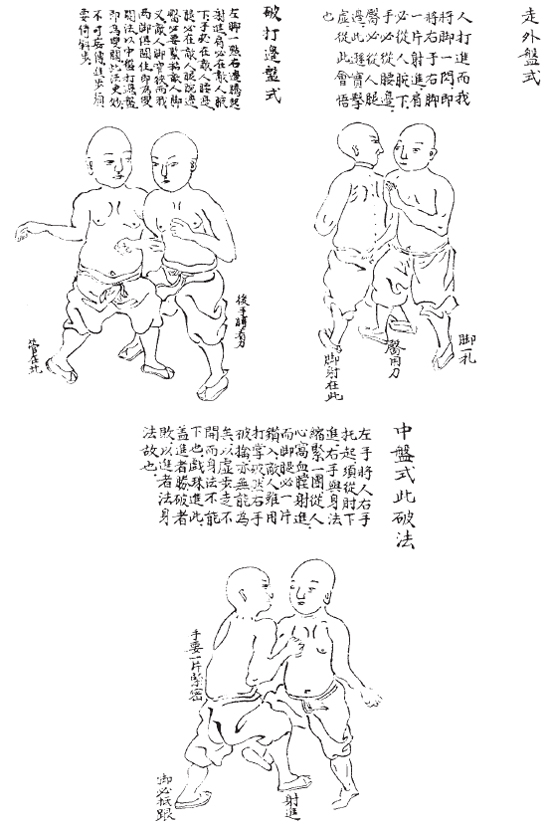

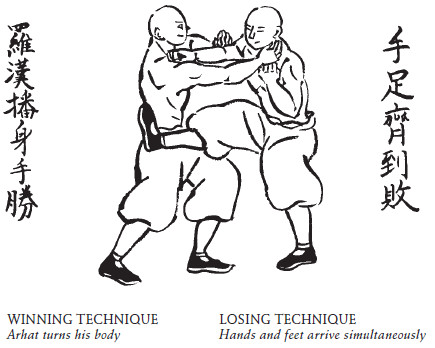

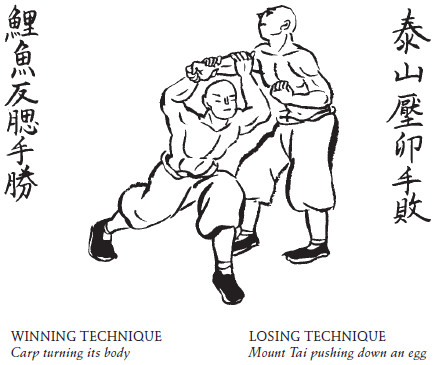

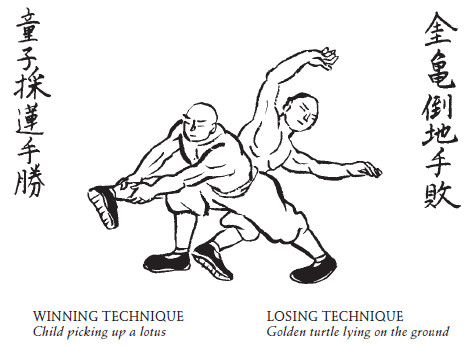

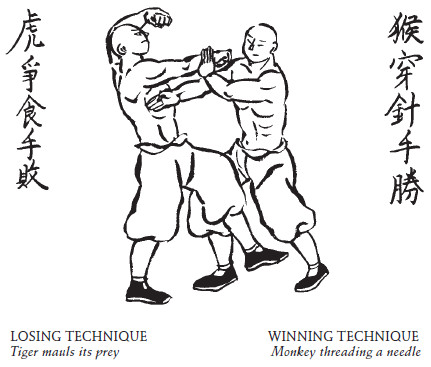

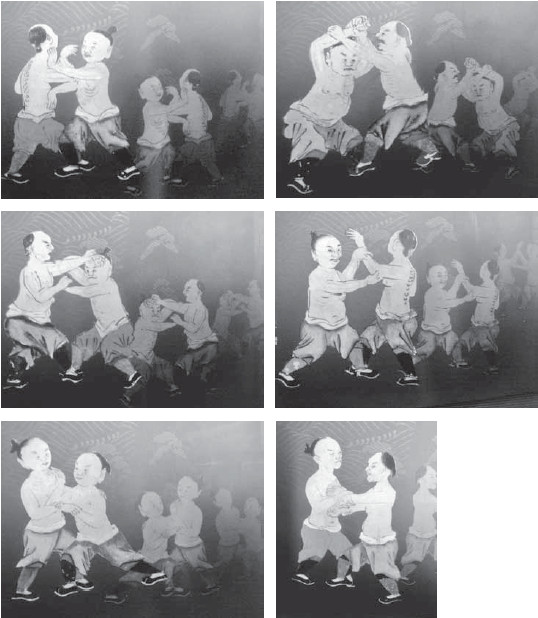

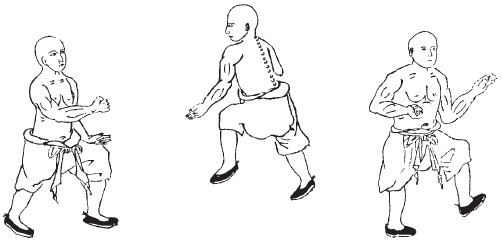

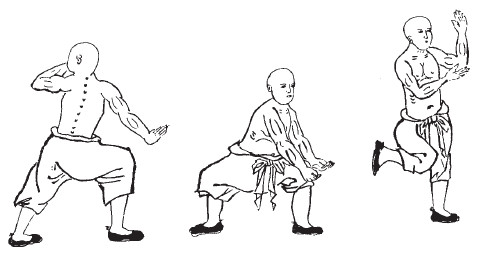

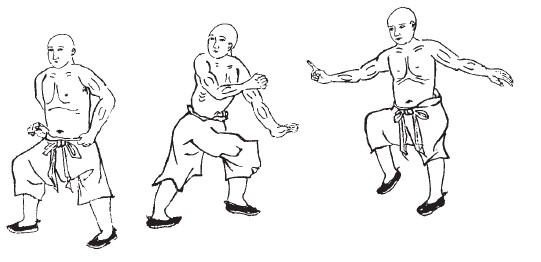

Rakanken two-person practices

A principal quan of Xie Zhongxiang’s Minghe Quan gongfu, Nepai, in Chinese characters, means “Twenty-Eight Strikes.” It emphasizes grappling and the striking of anatomical vulnerable points. Nepai was first introduced to Okinawa by Go Genki when he taught it to Kyoda Juhatsu and Mabuni Kenwa. To-on-ryu was the only Okinawan style that preserved and passed on Nepai. Mabuni’s version of Nepai, considerably different from the To-on-ryu version, is called Nipaipo, and is practiced by some sects of Shito-ryu. Nepai is still practiced by several styles of Fujian White Crane gongfu. The explanation on this page represents the original Whooping Crane version as taught to me by the great-grandson of Ryuru Ko, Xie Wenliang. (TR)

Article 13: The Eight Precepts of Quanfa

This is the only written explanation about the eight precepts in the Bubishi. However, in more current reproductions of the Bubishi, karate teachers in Japan have elaborated on these precepts. (TR)

Article 14: The Principles of Ancient Law

Once again I would like to reemphasize the importance of these ancient principles. By doing so, I hope to clear up any confusion regarding the rules of polarity and meridian flow theory. Because this law influences all people, one should practice early in the morning when the qi is peaceful.

If everyone learned these methods there would be less violence. These methods are intended to foster peace and harmony, not violence. If you know someone with these special skills you should ask them to teach you. The rewards of training are immeasurable for those who remain diligent and follow the correct path. However, this does not apply to those of immoral character.

When forced to fight, theory and technique are one in the same; victory depends upon who is better prepared. When engaging the adversary, respond instinctively. Movement must be fast and materialize without thought. Never underestimate your opponent, and be careful not to waste energy on unnecessary movement. If you recognize or create an opening, waste no time in taking advantage of it. Should he run, give chase but be prepared, expect the unexpected, and do not get distracted. You must evaluate everything when fighting.

Quanfa Strategies

A person may observe your fighting skills and compare them to his own. However, remember each encounter is different so respond in accordance to fluctuating circumstances and opportunity. Utilize lateral and vertical motion in all conceivable gates of attack and defense. Refrain from using an elaborate defense and remember that basic technique and common sense go a long way. I cannot emphasize enough the importance of taking advantage of an opening, and do not forget that the opposite also applies to you; always be aware of openings you present to your opponent.

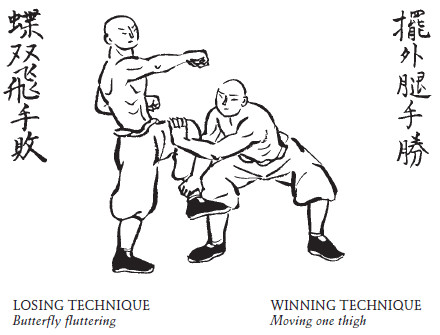

If seized above the waist by an adversary, use your hands to “flutter all over him like a butterfly.” If attacked below the waist, use your hands to hook him up “like a flapping fish in the water.” If confronted by an adversary you must appear as confident and powerful as a wolf or tiger pursuing its prey.

Learn well the principles of “hard” and “soft” and understand their application in both the physical and metaphysical realms. Be pliable when met by force (also be a modest and tolerant person), but use force to overcome the opposite (be diligent in the pursuit of justice).

The more you train (in quanfa), the more you will know yourself. Always use circular motions from north to south and do not forget that there is strength in softness. Never underestimate any opponent, and be sure never to use any more force than is absolutely necessary to assure victory, lest you be defeated yourself. These are the principles of ancient law.

Article 15: Maxims of Sun Zi

Article 16: Grappling and Escapes

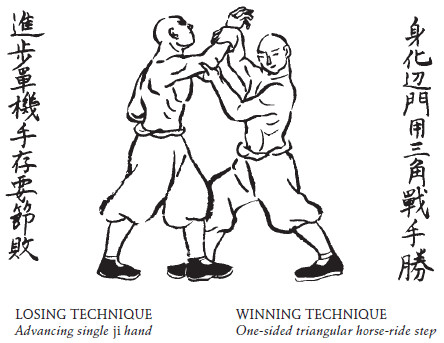

Article 20: Six Ji Hands of the Shaolin Style

Injuries sustained from these special hand techniques must be treated immediately or else the consequences could be fatal.

1. The Iron Bone Hand technique can only be developed through relentless physical training. After thrusting the bare hand into a container filled with hot sand on a daily basis for many weeks, the fingers gradually become conditioned enough to initiate the second stage of training. After thrusting the bare hand into a container filled with gravel on a daily basis for many weeks, the fingers will become even more conditioned so that the final stage of conditioning can be initiated. The final stage of conditioning requires one to thrust the bare hand into a container of even larger stones. This special kind of conditioning will lead to hand deformity and the loss of one’s fingernails. Alternative training methods often include thrusting the bare hand into bundles of wrapped bamboo in an effort to condition the fingers for lethal stabbing and poking. This technique is very effective for striking between the eyes. The Bone Hand technique will most certainly cause internal bleeding, especially if one is struck before mealtime. If one is struck with the Bone Hand after mealtime, the results could be fatal.

2. The Claw Hand is an effective technique and is especially effective for dislocating the jaw. Used in a circular and hooking fashion, it is a multipurpose technique. Medical treatment must be quickly rendered if struck with the Claw Hand. If not, internal hemorrhaging will be followed by three days of vomiting blood, and death within one month.

3. The Iron Sand Palm is developed in much the same way as the Iron Bone Hand. Using a wok filled with hot sand, training involves a slapping-type practice until the desired effect is accomplished. This technique is sometimes called the “Vibrating Palm.” The Iron Sand Palm is an effective weapon used against many vital areas. When used against the back of the skull, it is especially lethal and could kill someone instantly.

4. The Blood Pool Hand is used to twist and pull at the eyes, throat, head, hair, and genitals. Victims of this technique must be treated with a ginger and water solution. After applying cold water to the injured area, the victim must refrain from lying face down.

5. The Sword Hand technique is used to attack bones, tendons, and joints. It is an effective way to traumatize and subjugate an adversary. When struck by the Sword Hand a victim can experience a wide range of effects, including temporary loss of speech, unconsciousness, and seizures.

6. The One Blade of Grass Hand technique is sometimes called the “half-year killing technique,” but is more popularly referred to as the “death touch.” It is generally used to attack the spine and the vital points. Medical attention must be rendered immediately to anyone struck by this special technique.

Six Ji Hands

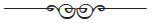

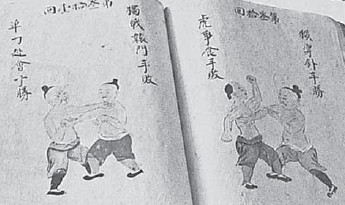

Article 27: Zheng’s Twenty-Four Iron Hand Applications and White Monkey Style

There is no explanation to accompany this illustration. However, it does say “Aunt and Uncle Zheng.” I assume that they are in some way related to Zheng Lishu (see Article 1, p. 157). In the Chinese ranking system, terms like big brother and uncle are used to denote seniority. (TR)

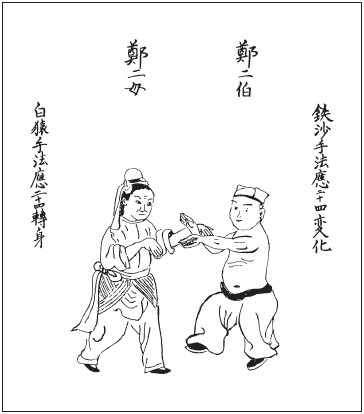

Article 28: Eighteen Scholars White Crane Fist and Black Tiger Style Fifty-Four Step Quan

Like Article 27 (see p. 266), there is no detailed explanation to accompany this illustration. I believe that they are the names of two significant quan. However, they are also labeled “She Ren,” which means that the two people are low-level public officials, and could mean that they were either employed by the Emperor, or an aristocrat’s family. People of wealth and/or position often engaged the services of those who were skilled in medicine and also experts in the fighting arts to be bodyguards, personal self-defense teachers, and in-house doctors.

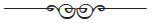

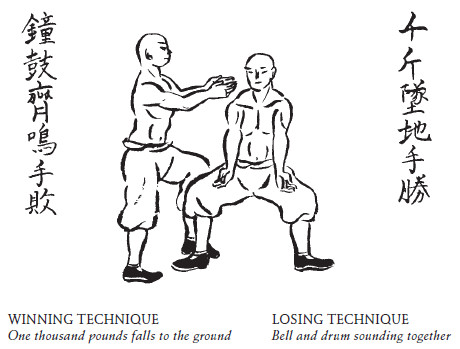

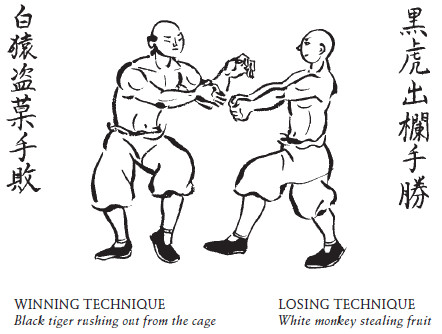

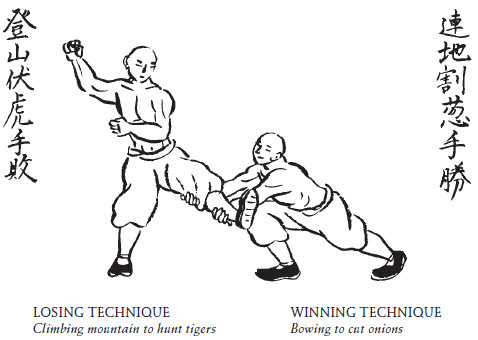

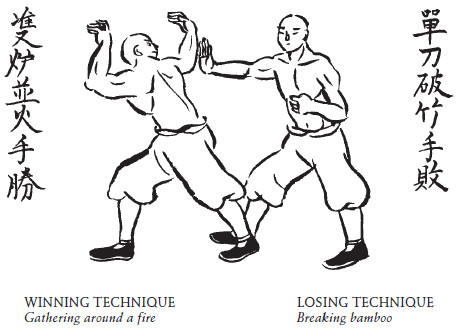

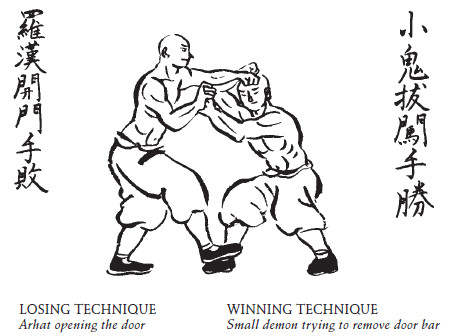

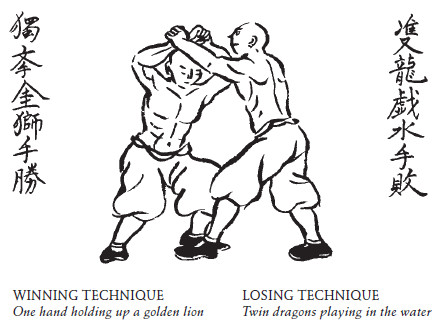

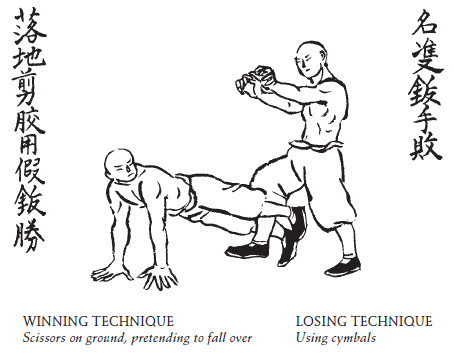

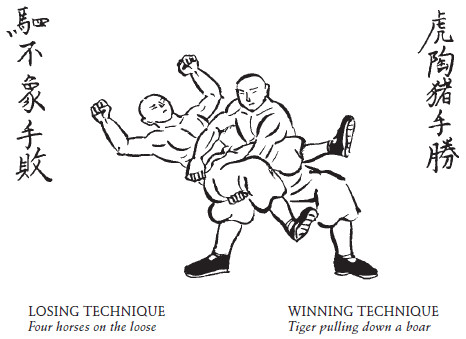

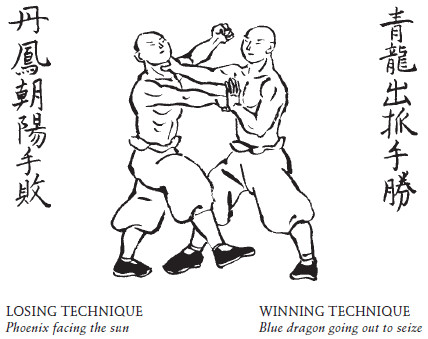

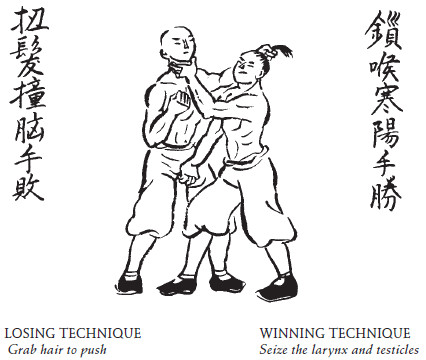

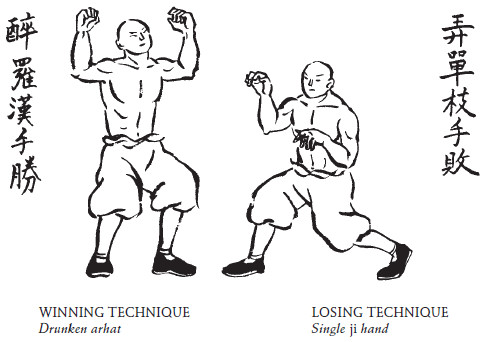

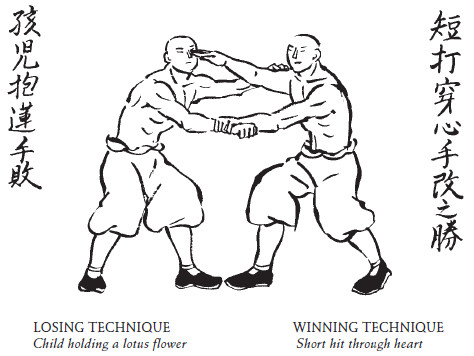

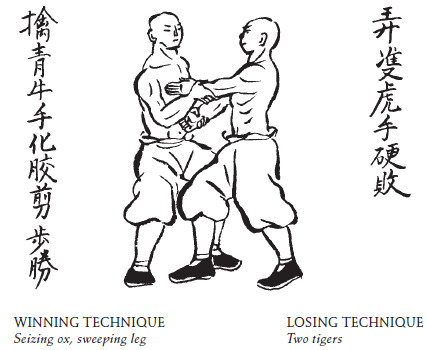

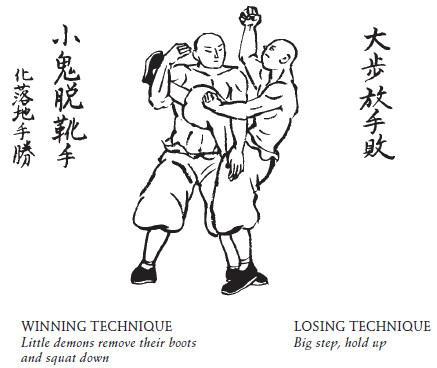

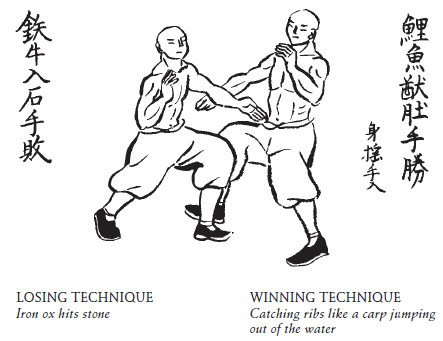

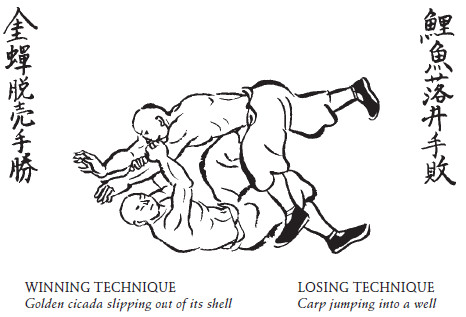

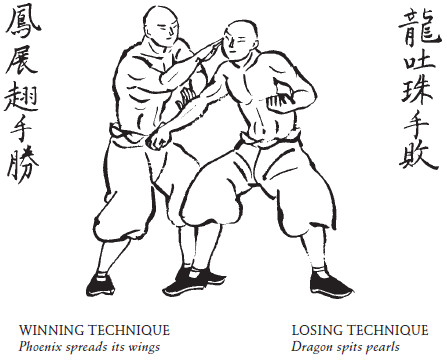

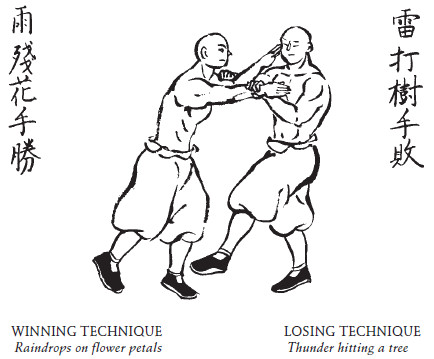

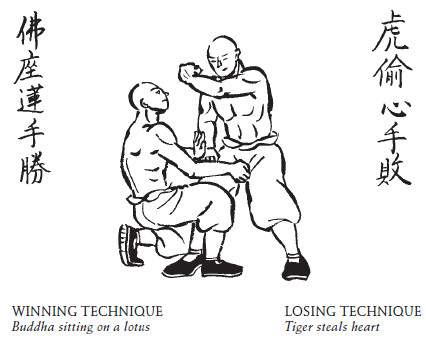

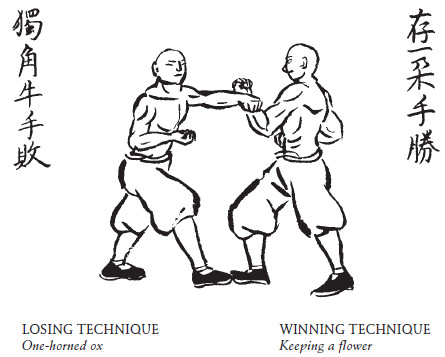

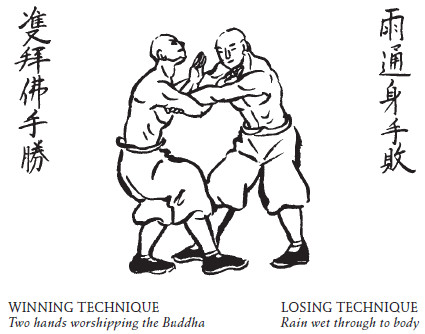

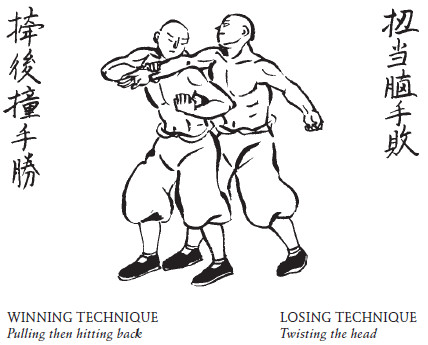

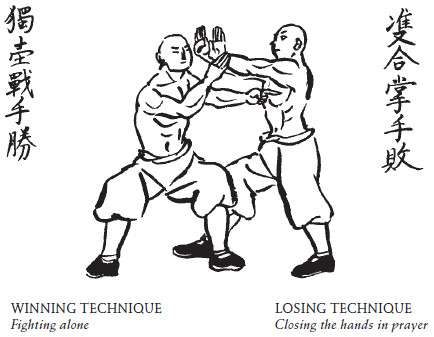

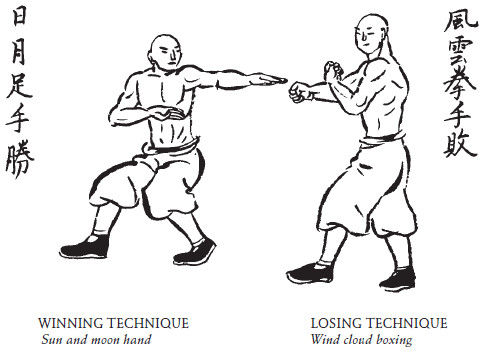

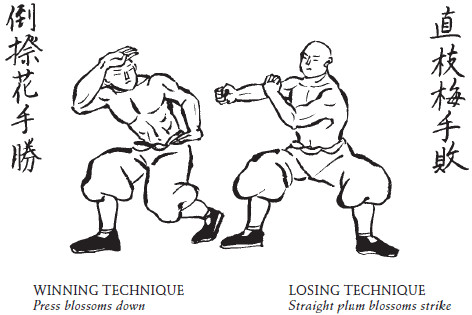

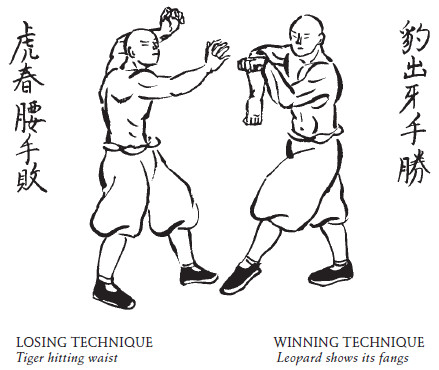

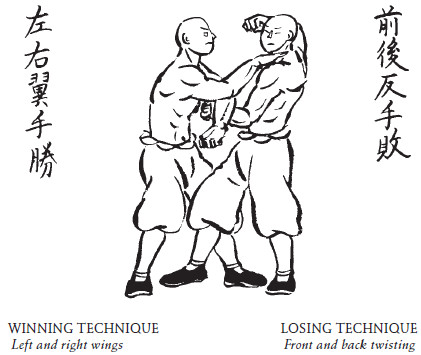

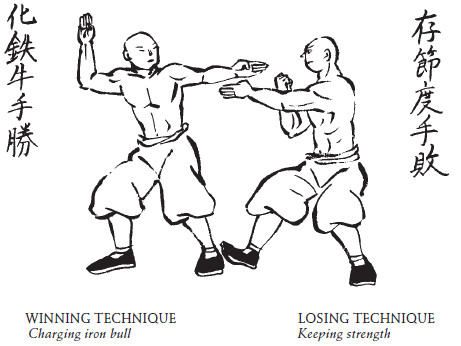

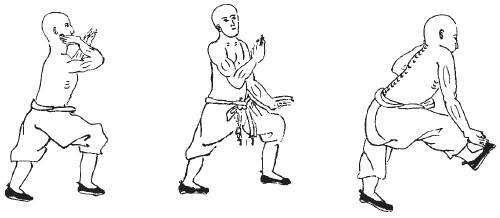

Article 29: The Forty-Eight Self-Defense Diagrams

The 48 self-defense illustrations, unlike other parts of this text, do not describe striking nerve plexus or blood canals, instead focusing on simple practical applications. These 48 self-defense illustrations can be divided into seven categories: defenses against fixed techniques, defenses against straight punches, defenses against various kinds of hand attacks, defenses against kicking techniques, how to react when grabbed, handling special circumstances, and defending against combinations.

After comparative analysis, one is easily able to recognize the remarkable similarity between these old illustrations and the many kata of traditional Okinawan karate-do. When comparing these 48 self-defense illustrations with other old Chinese and Japanese combative documents, I discovered a remarkable likeness with those of the Monk Fist style. I believe that this is an important discovery that brings us that much closer to locating one of the original Chinese sources from which karate-do came. Some of the names describing the applications in this segment correspond directly with the techniques in Article 6 (see pp. 257–258), on the four Monk Fist quan. Matsuda Takatomo Sensei, gongfu expert and author of Rakan Ken (Monk Fist Boxing) described the unidentified “hand and foot postures” of Article 32 as a typical “old-style quan” from his style.

In the following section I will first give the literal translation of the Chinese names for the techniques depicted in the illustrations, then I will describe the actual techniques. (TR)

1. To defend against someone who has you in a bear hug (left),

escape by dropping down in your stance (right).

2. If an attacker attempts to lunge out to strike you (left),

jam the attack, cutting off the assault in its midst (right).

3. If an attacker is vigorously trying to grab you (right),

quickly drop to the ground and scissor his leg (left).

4. Against a smaller attacker who grabs you (left),

counter by grabbing the back of the head (or hair) with one hand while lifting

the chin with the other and twisting the head (right).

5. It is often a good strategy to seize an attacker’s leg (right) if he

follows a hand technique with a high kick that compromises his balance (left).

6. If an attacker telegraphs his intentions by using long swinging motions (right),

make use of your distancing with evasive body movements while blocking with

your hands to position yourself for an effective counter (left).

7. When attacked by a downward overhead strike (left), step in and

counter with a simultaneous block and counterpunch (right) to the midsection.

8. In the midst of a grappling encounter where a person is trying to strike

your head (right), block the attack (left), seize the arm, and apply

a joint lock at the elbow to defeat him.

9. If an attacker tries to grab you with both hands (right),

drop to the ground, capture his leg (left) and take him down.

10. If an attacker tries to take you down by grabbing your leg (left),

counter by striking the temples (right) or slapping the ears.

11. In the heat of grappling, you can win by scooping up

the opponent’s legs (right) and flipping him over.

12. If an attacker assaults you with a vigorous combination of punches (left),

you can defeat him by going low and scooping up either leg and attacking

the inside of the thigh, taking him down (right).

13. If someone fakes a punch with one hand to hit you with the other

(especially an uppercut) (left), you should check the feint, move in,

and trap the second while seizing his larynx (right).

14. If an attacker reaches out to grab, push, or punch you (left),

redirect his energy and apply a joint lock (right).

15. If an attacker grabs you by the hair (left), seize both his larynx and testicles (right).

16. Often it is essential to deceive an attacker to make an opening. Use the

Drunken Fist method to feign intoxication, weakness, or cowardice (left)

and when he lets down his guard, immediately counterattack.

17. In a grappling encounter when an attacker chambers his hand to

strike you (left), reach out and seize his larynx and hair (right)

to manipulate the head and defeat him.

18. Regardless of an attacker’s size or strength, you can take him

down by seizing the leg with one hand and pushing the

inside of the knee or hip joint with the other (right).

19. In a grappling encounter in which you have little room to move,

you must attack the weak areas like the eyes, ears, nose, and larynx (right).

20. By twisting an attacker’s wrists (left),

his balance is weakened,

which permits you to follow up by sweeping his legs out from under him.

21. Another way to defeat an attacker is by seizing one leg (right)

and kicking the other out from under him.

22. By capturing an attacker’s leg, either when he is moving or attempting a

high kick, you can lift it up beyond its limit, causing him to fall on his head.

23. The art of deception is a powerful tool. If you can make an

attacker think that you have mistakenly left a target undefended,

it will be easy to anticipate his attack and counter it.

24. If an attacker reaches out to grab you (top), you can surprise him by

dropping to the ground and throwing him over your body (bottom).

25. If a person pushes, shoves, or tries to poke you in the eyes (left),

you can overpower him by shifting just outside the attack and

simultaneously striking behind the ear and the lower ribs (right).

26. Against someone who throws a one-sided, punch-kick combination (right),

utilize the evasive principles of Monk Fist Boxing by checking the punch and

sliding outside the attack to defeat the attacker (left).

27. Against a rear bear hug (right), take one step forward,

raising an arm to destroy the attacker’s balance, while

seizing his testicles with the other hand (left).

28. If an attacker tries to strike down on your head (right),

counter with an “X-block,” twist his arm (left), and throw him.

29. You can defeat an attacker by scooping up one leg (left)

and flipping him over on his back.

30. By checking a punch or pulling a push and striking a vital point (right),

it is easy to defeat an inexperienced attacker (left).

31. If an attacker reaches out to punch or grab you (right), step to his outside (left),

grab his lead arm, and apply an arm-bar, foot-sweep combination to defeat him.

32. If a person throws a short punch at you (right),

trap the attack and gouge his eyes (left).

33. When a person tries to trip you (left), check his attack, seize his hair, poke his

eyes, grab his groin (right), then pull his hair down to throw him to the ground.

34. If a person tries to smash his hand into your torso (right),

move in and use your arms (palms twisted out) to reduce the impact of

his attack, and then counter with the phoenix fist (left).

35. If a person abruptly seizes you (right),

be pliable, go with the flow, and strike his eyes (left).

36. An overconfident attacker (right) can be defeated by checking an

attack and dropping down to seize the testicles (left).

37. When attacked with a fierce straight punch (left),

move outside and check the attack before countering (right).

38. If a person grabs you in an effort to throw you (right), shift back a little to

offset his balance, chop down on his arms to loosen the grip, and then by coming

outside and then looping up and under his arms, lock his elbow joints (left).

39. By grabbing an attacker’s wrist and pulling him off balance,

you can strike his armpit or throat with your elbow (left)

before locking his arm to throw him down.

40. You can defeat a person who tries to grab you (right)

by sinking down and striking a single vital point (left).

41. If an attacker gets inside your engagement distance and tries to attack your

ribs with both hands (right), be sure to distance yourself precisely before

attempting to counter (left).

42. Lateral body movement (left) will present you with the precise space needed

to defeat an attacker (right) if you can accurately determine his distance.

43. If an attacker remains locked in his posture too long (right),

he will be unable to prevent a powerful hand attack (left).

44. If a person’s offense is hampered because of poor coordination (left),

you can avoid his attack by shifting your body to the side (right) and defeat him.

45. At close range, if a person tries to punch your body

(especially with an uppercut) (right), trap the attack and thrust your

fingers into his throat to defeat him (left).

46. Be quick to seize an opportunity (left) if your attacker

loses his balance after missing his intended target (right).

47. In the case of a person who hesitates during his attack (right),

quickly close the distance and counter with the vertical

downward palm strike to defeat him (left).

48. If a person is trying to inch his way inside your engagement distance and

presents a large target (left), feint an attack with one hand horizontally,

and when he reacts, come down on top of his head with the other hand (right).

This calligraphy by Grandmaster Hokama Tetsuhiro means “auspicious crane”

and was brushed as a congratulatory keepsake for this publication.

Earlier illustrations of some of the 48 postures

Two pages from the original Bubishi

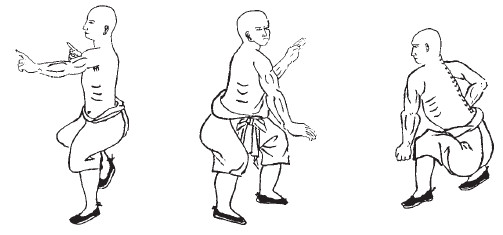

Article 32: Shaolin Hand and Foot, Muscle and Bone Training Postures

There is no descriptive text accompanying the illustrations that follow. The illustrations represent the individual combative postures of an original gongfu quan. The name of each movement and its self-defense application has been lost in the sands of time. Therefore, the exact details surrounding the origins and purposes of this particular quan are not available. However, by analyzing each of the illustrations, one can observe crane stances, crescent kicks, one-fingered thrusts, open-handed techniques, all of which are used in Monk Fist and Crane Boxing. (TR)

The Chinese characters for toudi-jutsu (or karate-jutsu), the first character of which refers to the Tang dynasty, and karate-do, “the way of the empty hand.”