Folk medicine maintains that herbs and exercise are man’s only natural protection against illness. Herbs can and do provide energy and promote smooth blood circulation, allowing the human body to eliminate the accumulation of toxins and the congestion that cause disease. In addition, herbs aid digestion, assimilation, and elimination. Moreover, herbs can be used to treat minor aliments as well as acute chronic conditions. Herbs have a remarkable history of healing the human body and maintaining good health when properly used. Unlike modern chemical medicines, natural herbs are much safer and do not leave residue in the body that produces side effects.

Of all countries in the world, China has the longest unbroken tradition of herbal medicine. In China, medicinal herbs have played an inseparable role in the civil fighting traditions for centuries. For masters of traditional gongfu, the principles of herbal medicine, acupuncture, massage, and other related forms of trauma management were an integral part of training; a speedy recovery was always necessary during a period void of social security. However, that knowledge, like the moral precepts upon which the fighting traditions rest, have been overshadowed in the modern era with its myriad of eclectic traditions, commercial exploitation, and the competitive phenomenon.

Articles 10, 11, 12, 19, 30, and 31 appear in the Bubishi with neither detailed explanation nor direction, and, like the other articles in this old text, are plagued by grammatical errors. The absence of any detailed information led this writer to believe that the prescriptions illustrated in the Bubishi were originally recorded by, and for, those who had previous knowledge of their application. However, after being copied by hand for generations, much has been lost because of miscomprehension and mistranslation. Mr. Li Yiduan said that orthodox Chinese herbal medicines, their names, and prescriptions are standardized throughout the country. However, in the case of local folk remedies, the names of prescriptions and ingredients are not standardized and vary from district to district. After consulting several local experts in Fuzhou, Mr. Li also said, “the information that appears in the Bubishi, especially the herbal prescriptions and vital point sections, is filled with numerous grammatical inaccuracies. In some parts of the Bubishi, whole sections have been omitted, while other parts have been recorded incorrectly, leaving the remaining information unintelligible.” Mr. Li concluded by saying that “there can be no question that these problems have occurred during the process of copying the text by hand over the generations.”

I have grouped the aforementioned six articles together, along with some preliminary research, to help explain the history and significance of Chinese herbal therapy or zhong yao, its related practices, and its relationship to the fighting traditions.

According to Chinese folklore, many centuries ago, a farmer found a snake in his garden and tried to beat it to death with a hoe. A few days later he discovered the same snake slithering around in his backyard, and he tried to kill it again. When the seemingly indestructible serpent appeared again a few days later, the farmer gave it another beating, only to see the bleeding viper squirm into a patch of weeds, where it commenced eating them.

Upon observing the reptile the following day, the farmer was astonished to find it invigorated with its badly beaten body rapidly healing. Such was the discovery, as legend has it, of san qi (Panax Notoginseng), a powerful healing herb, now used in a variety of herbal medicines.

Like so many other aspects of Chinese culture, herbal medicine has also had a host of heavenly deities or semi-divine idols representing it. The “Three August Ones,” Fu Xi, Shen Nong, and Yao Wang, once depicted the divine accuracy and propriety of this science. In Chinese history, the legendary emperor and last of the “Three August Ones,” Shen Nong (3494 B.C.) is regarded as the creator of medicine. Yao Wang, the second of the “Three August Ones,” is known as the “King of Medicinal Herbs.” Fu Xi, the first of the “Three August Ones,” reputed to have lived about 4,000 years ago, is generally credited with having invented just about everything else.

The tradition of using Chinese herbs for medicinal applications predates Christianity by more than three millennium. Shrouded in a veil of myth and mysticism, the history of herbal concoctions have been associated with such rituals as Shamanism and the forces of the supernatural. Although used more often to create an appropriate ritualistic atmosphere rather than strictly for their medicinal properties, ancient religious sects customarily used herbal concoctions in ceremonial rites. These shamans paved the way for the Daoist recluses who later chose to leave their communities to live in wild mountainous areas and lengthen their lives by using herbs, training in the civil fighting arts, and doing breathing exercises.

Confucian, Daoist, and Buddhist philosophy have also had a profound effect upon the development of herbal medicine. Confucius (551-479 B.C.) developed a moral and social philosophy based on the premise that the balance of yin and yang creates a correct order and harmony in the universe. He claimed that man must be moral and study and act in accordance with the Five Virtues (e.g., benevolence, justice, propriety, wisdom, and sincerity) in order to bring harmony to the world. In contrast Lao Zi taught that nature was harmonious when left alone and that man could have no positive impact on it. He claimed that one had to learn to stop resisting nature and that it was only through passivity, the following of the path of least resistance, and embracing nature in all its glory that positive results could be attained. Later Daoists invented a path to salvation and a spiritual destination, a mythical “Island in the Eastern Sea” where there was a herb that had the power to bestow immortality.

By the first century B.C., Dong Zhongshu had applied the yin-yang theory to internal medicine and nutrition. During the tumultuous Zhou dynasty (ca. 1000–221 B.C.) many scholars, like their forebearers the mountain recluses, sought out sanctuary deep in the mountains, and became known as the “Immortals of the Mountains.” Continuing the tradition of medical analysis, their research ultimately became the principal force behind the development of herbal medicine.

The first records of Chinese herbal concoctions, after graduating from sorcery to sophistication, are discovered in the classic discourse on internal medicine written by Huang Di (2698–2587 B.C.), the legendary “Yellow Emperor.” However, it was not until the Han dynasty (206 B.C.–A.D. 220) that Zhang Zhongjing (ca. A.D. 160–200) developed the practice of herbal medicine as a science. Considered the great codifier of medicine, Zhang’s unique application of the yin-yang and five-element theories helped establish a basis from which to more accurately diagnose and treat illness with herbal medicines. As such, sicknesses could be associated with specific organ dysfunctions and herbal remedies prescribed accordingly.

Many herbal formulae have been handed down from the Han dynasty. They have been refined, tested, verified, and experimented on by a hundred generations of herbalists, and in each generation their findings have been recorded and preserved.

It was during the Han dynasty that herbal formulae were notated and began to be used as an anesthetic in surgery. The eminent physician Hua Tuo (A.D. 141–208) used herbal soups to anesthetize patients in the surgical treatment of superficial diseases and wounds, and also experimented with hydro-therapy and the use of herbal baths.

Profoundly influenced by the mountain ascetics, Hua Tuo was also an ardent disciple of the fighting traditions. Concluding that balanced exercise and intelligent eating habits were instrumental in the cultivation of “a healthy life,” Hua developed a therapeutic gongfu tradition based upon the movements of five animals: the deer, tiger, monkey, crane, and bear. Through invigorating the vital organs, Hua’s therapeutic practice improved one’s circulation, respiration, digestion, and elimination. It also helped to improve physical strength while eliminating fatigue and depression. As such, the importance and relationship between physical exercise and herbal medicine was established over 1700 years ago.

Meridian Channels in Chinese Medicine

Over the course of centuries, an unending line of devout and observant physicians detected the existence of internal energy passageways and recorded their relationship to a number of physiological functions. Physicians came to observe specific hypersensitive skin areas that corresponded to certain illnesses. This ultimately led to the recognition of a series of recurring points that could be linked to organ dysfunction. By following these fixed paths, the points came to be used to diagnose organ dysfunction. The route linking these series of points to a specific organ became known as a meridian.

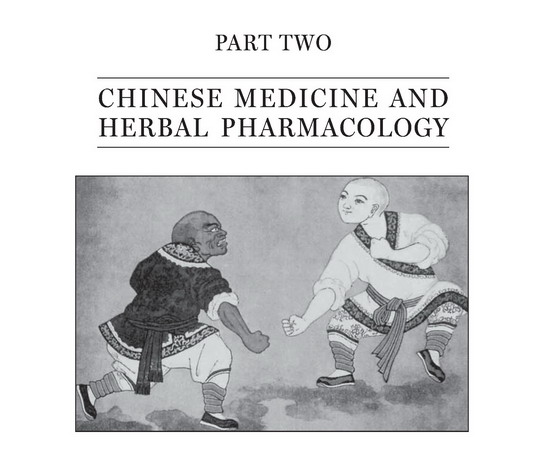

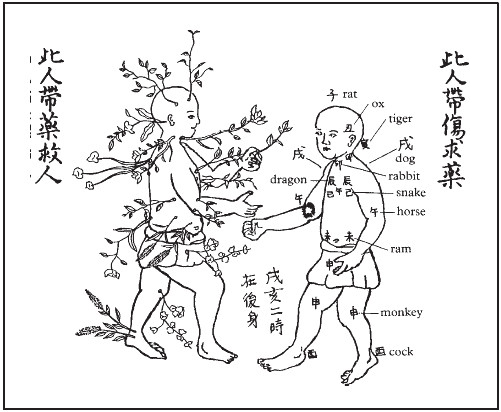

The times for the 12 shichen.

The idea for attacking the 12 bi-hourly vital points surfaced from research surrounding the polarity or “Meridian Flow theory” of acupuncture. By the Song dynasty, Xu Wenbo, an eminent acupuncturist and the official doctor for the Imperial family, developed this theory into a science. Concluding that the breath (respiratory system) and blood (circulatory system) behaved within the body in the same way as the earth rotated in the sky, he discovered how the vital point locations changed with time. He found that the human body’s 12 meridians correspond to the 12 bi-hourly time divisions of the day. There are twelve shichen to a day and each shichen is equivalent to two hours. The shichen are named after the 12 animals of the Chinese zodiac: therefore, the period between 11 p.m. and 1 a.m. is the Time of the Rat, 1 a.m. to 3 a.m. is the Time of the Ox, and so on. It is through this method that a certain vital point could be most fatally traumatized during a corresponding shichen interval. Meticulously recording his research, he documented more than 350 vital points. His analysis identified how the respiratory and circulatory systems correspond to a given meridian or vital point, and which vital point opened and closed at what time.

Responsible for remarkable advances in medical science, Xi Yuan, an eminent thirteenth-century Chinese physician, standardized the methods of how to improve a sick patient’s prognosis by stimulating the points of a corresponding meridian. Xi Yuan was also among those who furthered the research into the influence of solar and lunar cycles on the circulatory system and organs.

Xi Yuan determined precisely at what time of each day the 12 regular meridians exhibited two-hour periods of maximum and minimum energy by comparing his findings to the shichen. To demonstrate his analysis, Xi Yuan drew charts and diagrams illustrating the central principles of this complex theory.

In time, ways of utilizing herbs to cure dysfunctioning organs and correct the flow of energy in the body were developed. Some herbs were used for a specific meridian and would not be mixed, for they could cause disease instead of curing it when combined.

With the advent of Buddhism, a growing intercourse between India and China gradually affected the growth and direction of herbal medicine and the fighting traditions. From the first to the ninth centuries A.D., pilgrims, sages, translators, teachers, trade delegates, ambassadors, etc. crossed and recrossed the mountains between the two cultures. Part of that intercourse was directly concerned with healing.

India has long had a profound tradition of herbal medicine. By the start of the Tang dynasty (618–907 A.D.), all serious Chinese physicians and doctors were familiar with both the Chinese and Buddhist texts of healing. This cross-fertilization of knowledge advanced Chinese medicine considerably.

By the Ming dynasty, the principles of acupuncture and herbal medicine had spread widely and a great number of books had been written on all aspects of them. Every physician in China, from Imperial Court doctor to village medicine man, vigorously employed the principles of herbal medicine and acupuncture to help sick people.

One of the most important documents on herbal medicine of that time was the Ben Cao Gang Mu (General Outline and Division of Herbal Medicine), by Dr. Li Shizhen (1517–93). Considered one of Ming China’s most eminent medical scholars, his classic encyclopedia of herbal medicine listed 1892 different herbal medicines, in 52 volumes (scrolls), and took 27 years to research and compile. Translated into Vietnamese, Japanese, Russian, French, German, Korean, and English, it has even been claimed that Li’s prodigious treatise even influenced the research of Charles Darwin.

Following the Qing dynasty, China’s Imperial Medical College established a national standard for the healing sciences of acupuncture, herbal medicines, qigong, moxibustion, and massage therapy.

However, Western medical standards have, until only quite recently, always considered these ancient natural principles of medicine a kind of “backwoods” tradition. It has only been after lengthy analysis and astonishing results that these concepts have been widely accepted in the Western world and are now often used side by side with modern technology.

In the Shaolin Bronze Man Book, there is an article that describes the important connection between medicine and the civil fighting traditions, “a person who studies quanfa should by all means also understand the principles of medicine. Those who do not understand these principles and practice quanfa must be considered imprudent.”

In his 1926 publication Okinawa Kempo Karate-jutsu Kumite, Motobu Choki (1871-1944), unlike his contemporary Funakoshi Gichin, described revival techniques, the treatment of broken bones, dislocated joints, contusions, and the vomiting of blood caused by internal injury, and explained the value of knowing medical principles. Much like the Bubishi, Motobu refers to various herbal concoctions and how they are able to remedy numerous ailments, be they external or internal. Motobu’s book lists many of the same herbs noted in both the Bubishi and the Shaolin Bronze Man Book (see Article 31, p. 191).

Examples of Herbal Medicine

Chinese herbal medicine employs a myriad of ingredients from the undersea and animal kingdoms, the world of plants, fruits, and vegetables, along with minerals and a select number of exotic elements. While there are virtually hundreds of kinds of products that are extracted from mother nature, the following list represents the principal sources from which most are derived: roots, fungi, shrubs, sap and nectar, grass, wood and bark, floral buds, petals, leaves, moss, plant stems and branches; fruits, nuts, seeds, berries, and various vegetables; various insects, reptiles, pearls, sea life, and ground minerals; deer antlers and the bones of certain animals. Unusual elements include the internal organs of various animals and fish, scorpion tails, wasp or hornet nests, leeches, moles, praying mantis chrysalis, tortoise shell, bat guano, dried toad venom, male sea lion genitalia, urine of prepubescent boys, domestic fowl gastric tissue, the dried white precipitate found in urinary pots, powdered licorice that has been enclosed in a bamboo case and buried in a cesspool for one winter (the case being hung to dry thoroughly and licorice extracted), dried human placenta, and human hair.

Generally speaking, prescriptions are drunken as tea or soups; made into hot and cold compresses, poultices, powders, ointments, liniments, and oils for massaging directly into wounds or sore areas; refined into paste for plasters; or put in pills or gum to be taken orally. Herbs are usually prescribed together to enhance their effectiveness, with the exception of ginseng, which is usually taken by itself. Described as the “master/servant” principle, herbs of similar properties and effects are used together.

Following serious injury or sickness, it is essential to reestablish homeostasis within the glandular, circulatory, and nervous systems to ensure a healthy recovery. Sharing corresponding principles, herbal medicines, acupuncture, moxibustion, and massage have, and continue to be, effective practices in trauma management and the curing of disease.

Nowadays, with the growing concern over the side-effects of prescription drugs, an understanding of ecology, and people’s desire to take greater responsibility for their own health, the use of medicinal herbs is experiencing a remarkable revival.

Effects of Herbal Medicine

The following terms meticulously describe the effects of herbal medicines:

analgesic: eliminates pain while allowing the maintenance of consciousness and other senses

anesthetic: eliminates pain and causes unconsciousness

anthelmintic: kills or removes worms and parasites from the intestines

antidote: counteracts poisons

antiphlogistic: reduces inflammation

antipyretic: reduces fever

antiseptic: kills microorganisms

antispasmodic: reduces or stops spasms

antitussive: suppresses coughing

aphrodisiac: increases sexual desire

astringent, styptic: reduces blood flow by contracting body tissues and blood vessels

carminative: assists in the release of flatulence

cathartic: assists the movement of the bowels

demulcent: soothes infected mucous membranes

diaphoretic: assists perspiration

digestive: assists digestion

diuretic: assists urination

emetic: causes vomiting

emmenagogue: assists menstruation

emollient: softens, soothes

expectorant: assists in expulsion of phlegm

hemostatic: stops blood flow

laxative: assists bowel movements gently

purgative: assists bowel movements strongly

refrigerant: cooling, relieves fever

sedative: reduces anxiety, excitement

stimulant: increases sensitivity and activity

stomachic: tonifies the stomach tonic: restores or repairs tone of tissues

Through meticulous research, unending cross-referencing, and the untiring assistance of the Fujian gongfu masters and herbalists associated with Mr. Li Yiduan, Mr. and Mrs. Okamoto of the Tokiwa Herb Emporium, botanist Suganuma Shin, my friend Mitchell Ninomiya, and my wife Yuriko, I am able to present the translation of the following articles.

For the sake of easy future reference, the botanical lerms of these plants and elements of nature have been transcribed. Over the years, in the various old reproductions of the Bubishi I have come across, rarely did I find precise weight measures or accurate preparations for the herbal prescriptions detailed. Furthermore, in at least one notable case, the prescription had been completely rewritten (no doubt by a modern herbalist). Nonetheless, I did learn that the precise weights and preparations for all the legible prescriptions in the Bubishi could be accurately determined by any Chinese herbalist, especially after diagnosing a sick patient’s condition.

However, the following prescriptions are presented here as informative matter only, and are not intended to be construed by the reader as reliable or in some instances safe treatments for the corresponding maladies. (TR)

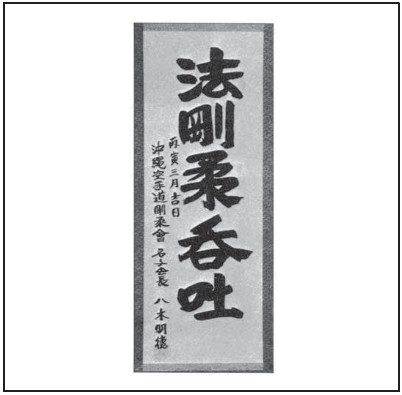

This calligraphy by Grandmaster Yagi Meitoku means “Inhaling represents softness while exhaling characterizes hardness.” This quote was taken from Article 13 (p. 261) of the Bubishi and inspired Grandmaster Miyagi Chojun to name his style Goju-ryu.

Articles on Chinese Medicine and Herbal Pharmacology

Article 10: Prescriptions and Medicinal Poems

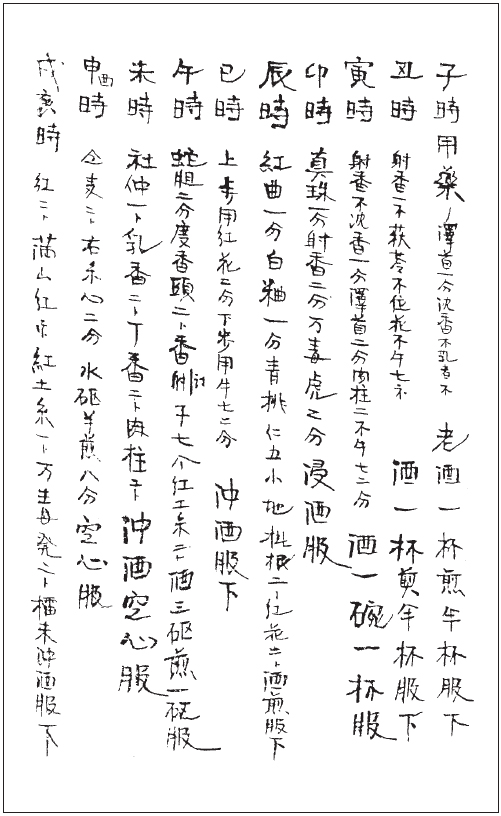

Article 11: Twelve-Hour Theory Recuperative Herbal Prescriptions

MERIDIAN SHICHEN

Gall Bladder Rat (11 p.m.-1 a.m.)

Liver Ox (1-3 a.m.)

Lungs Tiger (3-5 a.m.)

Large Intestine Rabbit (5-7 a.m.)

Stomach Dragon (7-9 a.m.)

Spleen/Pancreas Snake (9-11 a.m.)

Heart Horse (11 a.m.-1 p.m.)

Small Intestine Ram (1-3 p.m.)

Bladder Monkey (3-5 p.m.)

Kidneys Cock (5-7 p.m.)

Pericardium Dog (7-9 p.m.)

Three Heater Boar (9-11 p.m.)

The Bubishi does not say exactly how to utilize these prescriptions (i.e., to drink them or use them externally). (TR)

Article 12: A Physician’s Treatment for Twelve-Hour Injuries

For Complications Arising from an Injury to the Kidneys or Carotid Artery

Treating Muscle Injuries

Treating Burns

Treating Back Injuries

Head Injuries

Loss of Consciousness

To Stop Bleeding

Treating Head Injuries Resulting from Being Traumatized by Iron Objects

Extraction of Internal Injuries

Treating Back Pain

Pain Killer

Soak in one bottle of aged wine and cook slowly over a low flame to prepare prescription.

Remedy for Malaria

Ferment for one day in aged wine and then decoct over a low flame to prepare prescription, which can be used immediately.

Remedy for Lower Back and Hip Pain

Ferment in one bottle of aged wine and cook over a low flame to prepare prescription.

Treating Open Wounds

Take an ant’s nest that was built on a longan tree and roast it on a new tile. Ground the remains into a powder, mix with water, and steam it until it is thick. Apply directly to open wounds.

Article 18: Four Incurable Diseases

People not recovering from serious sword or spear wounds, even after medical treatment is rendered, usually die. Characteristics of the illness causing this are difficulties in breathing and the inability to keep the mouth shut.

If a wound becomes complicated by infection and the patient begins getting cold, with signs of stiffening, fever, and shaking violently, departure from this world is certain.

When the eyeballs are locked in place without moving, a person’s spirit has withdrawn, which means he is no longer in charge of his mental faculties.

Any deep wound that causes an organ to dysfunction, impairing the circulatory system, usually results in death.

In addition to quanfa, a disciple must be patient and endeavor to acquire the medical knowledge to treat and cure the injured and sick. True quanfa disciples never seek to harm anyone, but are virtuous, kind, and responsible human beings.

This knowledge has been compiled and handed down from the Shaolin recluses from long ago. Never deviating, it remains constant.

Article 19: Effective “Twelve-Hour Herbal” Prescriptions to Improve Blood Circulation for Shichen-Related Injuries

Rat Time (11 p.m.-1 a.m.) Medicine

Decoct in one cup of old wine. Strain and drink a half cup.

Ox Time (1-3 a.m.) Medicine

Decoct in one cup of rice wine. Strain and drink a half cup.

Tiger Time (3-5 a.m.) Medicine

Decoct in one bowl of rice wine. Strain and drink one cup.

Rabbit Time (5-7 a.m.) Medicine

Soak them in rice wine, strain and drink.

Dragon Time (7-9 a.m.) Medicine

Decoct in rice wine, strain, and drink.

Snake Time (9-11 a.m.) Medicine

Decoct in rice wine, strain, and drink.

Horse Time (11a.m.-1 p.m.) Medicine

Decoct in three cups of rice wine, strain, and drink one cup.

Ram Time (1-3 p.m.) Medicine

Decoct in rice wine, strain, and drink when your stomach is empty.

Monkey Time (3-5 p.m.) Medicine

Decoct in half a cup of water to prepare 2.48 grams (8 fen). Drink when your stomach is empty.

Cock Time (5-7 p.m.) Medicine

Same as Monkey Time Medicine.

Dog Time (7-9 p.m.) Medicine

Make it into a powder, decoct in rice wine, strain, and drink.

Boar Time (9-11 p.m.) Medicine

Same as Dog Time Medicine.

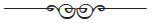

Article 22: Twelve-Hour Green Herbal Remedies

These herbs should be ground into a powder, mixed with rice wine, and drank every three hours to quickly remedy related injuries.

| SHICHEN | CHINESE PRONUNCIATION (MANDARIN) |

CHINESE IDEOGRAM |

|

| 1. | Rat (11 p.m.-1 a.m.) | wan du hu | 萬 毒 虎 |

| 2. | Ox (1-3 a.m.) | ma di xiang | 馬 地 香 |

| 3. | Tiger (3-5 a.m.) | mu guang yin | 暮 光 陰 |

| 4. | Rabbit (5-7 a.m.) | qingyu lian | 青 魚 蓮 |

| 5. | Dragon (7-9 a.m.) | bai gen cao | 白 根 草 |

| 6. | Snake (9-11 a.m.) | wu bu su | 烏 不 宿 |

| 7. | Horse (11 a.m.-1 p.m.) | hui sheng cao | 回 生 草 |

| 8. | Ram (1-3 p.m.) | tu niu qi | 土 牛 七 |

| 9. | Monkey (3-5 p.m.) | bu hun cao | 不 魂 草 |

| 10. | Cock (5-7 p.m.) | da bu si | 打 不 死 |

| 11. | Dog (7-9 p.m.) | yi zhi xiang | 一 枝 香 |

| 12. | Boar (9-11 p.m.) | zui xian cao | 酔 仙 草 |

The herbs above are so obscure that we were not able to identify all the English names for them. As such I will list only their Chinese names. (TR)

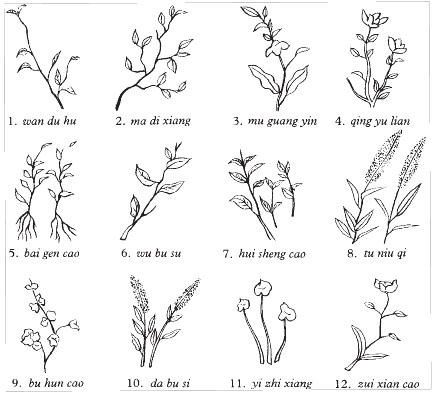

Article 23: Crystal Statue Diagram

| SHICHEN | LOCATION |

| Rat (11 p.m.-1 a.m.) | Top of the Skull |

| Ox (1-3 a.m.) | Temples |

| Tiger (3-5 a.m.) | Ears |

| Rabbit (5-7 a.m.) | Throat and Carotid |

| Dragon (7-9 a.m.) | Chest |

| Snake (9-11 a.m.) | Ribcage |

| Horse (11 a.m.-1 p.m.) | Arms and Solar Plexus |

| Ram (1-3 p.m.) | Stomach |

| Monkey (3-5 p.m.) | Pelvis and Knees |

| Cock (5-7 p.m.) | Ankles |

| Dog (7-9 p.m.) | Upper Back |

| Boar (9-11 p.m.) | Lower Back |

Article 23 refers only to group one and group two herbs; fresh and green plants (sometimes referred to as the master and servant principle). Group one and two herbs are part of four classes of Chinese medicinal herbs used: group one are master herbs, group two are subordinate herbs, group three are enhancing herbs, and group four are function herbs.

Complications arising from injuries to the preceeding locations must be treated with the medicinal herbs listed in Article 22 (see p. 187).

Article 25: Shaolin Herbal Medicine and Injuries Diagram

| LOCATION | SHICHEN |

| The top of the skull | Rat (11 p.m.-1 a.m.) |

| The temples | Ox (1-3 a.m.) |

| The ears | Tiger (3-5 a.m.) |

| The throat and carotid artery | Rabbit (5-7 a.m.) |

| The chest area | Dragon (7-9 a.m.) |

| The rib cage | Snake (9-11 a.m.) |

| Both arms and the solar plexus | Horse (11 a.m.-1 p.m.) |

| The stomach | Ram (1-3 p.m.) |

| The pelvis and knees | Monkey (3-5 p.m.) |

| The ankles | Cock (5-7 p.m.) |

| The upper back | Dog (7-9 p.m.) |

| The lower back | Boar (9-11 p.m.) |

The left figure illustrates a Chinese medicine hawker with the kind of herbs available for injuries or illnesses that correspond to the 12 shichens, illustrated by the right figure. The times and locations of this illustration are the same as in the Crystal Statue and Bronze Man diagrams (see Article 23, p. 188 and Article 24, p. 246). The medicine hawker is giving the injured man the herb wu bu su (Zanthoxylum avicennae Lam. DC. (Rutaceae)) to treat his injured arm. This herb is used to reduce swelling caused by a traumatic injury.

Article 30: Valuable Ointment for Treating Weapon Wounds and Chronic Head Pain

Herbs must be chopped into small rough pieces and soaked in five kilograms of sesame seed oil. Note that the herbs should be soaked for three days during spring weather, six days during summer weather, seven days during autumn weather, and ten days during winter weather. Decoct in rice wine until herbs turn black. Strain through a linen fabric to clean off unnecessary residue. Do not decoct or treat herbs again until you add two kilograms of minium. Stir continuously with the branch of a willow tree while decocting over a strong flame until solution evaporates. Continue stirring over a low flame until the solution turns to a thick paste. To get the maximum potency from medicinal herbs it is important to understand the different times required to properly decoct plants, flowers, leaves, stalks, roots, minerals, etc. The effectiveness of each ingredient depends entirely upon the length of time you have decocted it. For example, an ingredient that is decocted for too long may have a reverse effect upon its user.

Ingredients

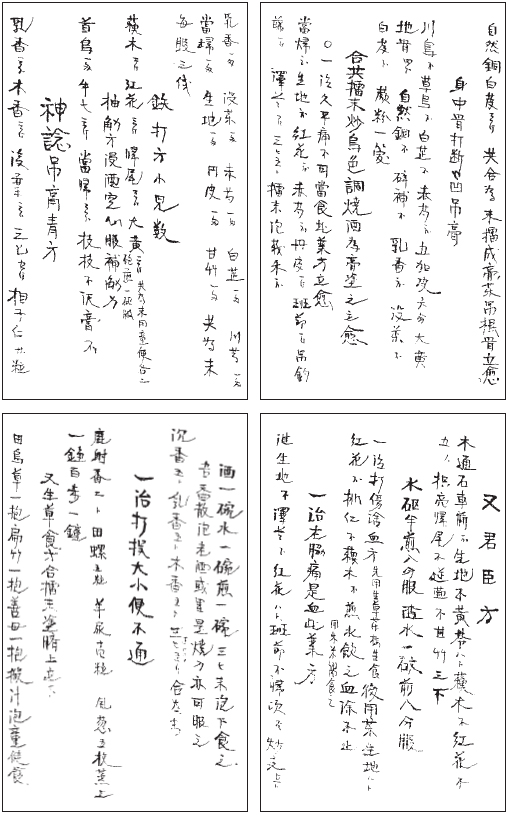

Article 31: Ointments, Medicines, and Pills

Eight Immortals Crossing the Sea Internal Healing Pills

Use about 3.75 grams of each ingredient and grind into a fine powder. Take 3.75 grams and mix with rice wine for one dose to treat internal bleeding, or the medicine can be wrapped in rice paper to make individual pills to be taken later. If pills are made, honey should also be used.

An alternative is to use the following “Herbal Brew” recipe that helps the heart and promotes blood flow. Decoct in a bowl-and-a-half of water until eight-tenths of a bowl remain.

Rooster Crowing Powder Medicine (Ji Ming San)

Grind ingredients into a powder, decoct in rice wine, and drink it when the rooster crows at dawn.

Pain Killer for Treating Weapon Wounds

Grind ingredients into a fine powder, soak in rice wine, and prepare 11.25 gram dosages for each treatment, which is to be taken with rice wine.

Alternative Treatment for Weapon Wounds

Grind ingredients into a fine powder, mix in warm rice wine, and prepare 11.35 gram dosages for each treatment. Drink for 3-4 days until you are fully recovered.

Vein and Blood Vessel Tonic

Used to restore damaged or weak muscle tissue; stimulate vitality; promote kidney and liver function. Also used to contract blood vessels and check the flow of blood.

After soaking in rice wine, roast ingredients dry before grinding into a powder to make 2.5 gram dosages. Take it when your stomach is empty for optimal results.

Effective Herbal Plaster Ointment for Treating Bone Fractures

Crush class one ingredients into a paste (ointment) and apply directly to damaged area.

Herbal Ointment for Treating Bone Bruises

Grind ingredients together, roast until color changes to black, add rice wine, and cook into a paste before applying to bruised area.

Original Herbal Cure for Chronic Suffering

Grind these ingredients into a powder and begin to decoct in one cup of rice wine then add Curcuma zeadoaria Rose. (Zingiberaceae) 6.24 grams, and mix in some fresh Panax pseudo-ginseng Wall. (Araliaceae).

Five Fragrance Herbal Powder (Wu Xiang San)

Used to treat infections resulting from open (stab) wounds.

Mix ingredients together, roast until hard, grind into a powder, and mix with native wine before application.

Promoting the Secretion and Flow of Urine Hampered by Trauma to Testicles

Make an ointment by crushing all ingredients together into a pulp before applying to injured area.

An Alternative Treatment for Promoting Urine Flow

Grind all ingredients together, collect the juice, mix with the urine of a healthy boy under 12 years old, and drink.

The Master and Servant Treatment (Jun Chen Fang)

This refers to the principal herbs being supplemented by secondary herbs to either enhance or decrease the potency of a given prescription. It can also be used for promoting the flow of urine.

Decoct in a bowl-and-a-half of water, until eight-tenths of a bowl remain and apply the sediment directly to the bruised area.

A Cure for Internal Bleeding and Trauma-Related Injuries

Before taking this prescription one should first eat some fresh wu ye mei.

Decoct in water until eight-tenths of a bowl remain. If bleeding does not subside, prepare herbs in ground grain and eat.

Honey should be used with nearly all internal medicines, and all ball-or-pill-form dosages. If honey is not used, there is a strong possibility that the effectiveness of the medicine will be reduced by 50%, if not 100%.

A Cure for Internal Bleeding and Left-Sided Pleurisy

Decoct in a bowl-and-a-half of water until eight-tenths of a bowl remain.

A Cure for Restoring Qi and Right-Sided Pleurisy

Decoct in a cup-and-a-half of water and prepare 2.5 gram dosages

The Light Body Way (Qing Yu Gao) Vitality Elixir

This medicine will make your body strong and lively. It especially promotes blood circulation and invigorates the internal organs; it will even make gray hair black again. Taking this medicine will make people feel so young, light, and vigorous that they will feel as if they can fly. Contained in a valuable book, this prescription has been handed down for generations and describes how we must care for ourselves, so that our fortune is not squandered nor precious lives wasted. These are the precepts handed down from the Daoist ascetics. It is the Way.

Steam the ingredients nine times then sun them nine times. Eat 9-12 grams every morning. This will promote good blood circulation and provide abundant energy.

Five Herb Medicine Powder (Wu Gin San)

Used to prevent infectious diseases. Also called Xiao Yu Wan.

Mix together all ingredients and decoct in water. Blend with powdered rice and cook into a paste to make pills.

Yellow Texture Medicine (Huang Li Tang or Zai Zao Wan)

Used to treat blood loss and anemia.

Crush fresh ingredients together, mix with glutinous rice, and simmer over low flame. Make pills from the paste.

Medicine Worth Ten Thousand Gold Pieces (Wan Jin Dan)

The remedy for Rooster Crowing Powder Medicine appears in Motobu Choki’s 1926 book Okinawan Kempo Karate-jutsu Kumite on p. 73 of Seiyu Oyata’s English translation, or p. 57 of the original Japanese version. The two remedies that follow (i.e, Pain Killer for Treating Weapon Wounds and Alternative Treatment for Weapon Wounds) also appear in that book on the same page. No recipe is given for Medicine Worth Ten Thousand Gold Pieces except “hot water half cup.” (TR)

Early hand-written portion of Article 19.

Early hand-written portions of Article 31