The most remarkable and characteristic problem of aesthetics is that of beauty of form. Where there is a sensuous delight, like that of colour, and the impression of the object is in its elements agreeable, we have to look no farther for an explanation of the charm we feel. Where there is expression, and an object indifferent to the senses is associated with other ideas which are interesting, the problem, although complex and varied, is in principle comparatively plain. But there is an intermediate effect which is more mysterious, and more specifically an effect of beauty. It is found where sensible elements, by themselves indifferent, are so united as to please in combination. There is something unexpected in this phenomenon, so much so that those who cannot conceive its explanation often reassure themselves by denying its existence. To reduce beauty of form, however, to beauty of elements would not be easy, because the creation and variation of effect, by changing the relation of the simplest lines, offers too easy an experiment in reputation. And it would, moreover, follow to the comfort of the vulgar that all marble houses are equally beautiful.

To attribute beauty of form to expression is more plausible. If I take the meaningless short lines in the figure and arrange them in the given ways, intended to represent the human face, there appear at once notably different æsthetic values. Two of the forms are differently grotesque and one approximately beautiful. Now these effects are due to the expression of the lines; not only because they make one think of fair or ugly faces, but because, it may be said, these faces would in reality be fair or ugly, according to their expression, according to the vital and moral associations of the different types.

Nevertheless, beauty of form cannot be reduced to expression without denying the existence of immediate æsthetic values altogether, and reducing them all to suggestions of moral good. For if the object expressed by the form, and from which the form derives its value, had itself beauty of form, we should not advance; we must come somewhere to the point where the expression is of something else than beauty; and this something else would of course be some practical or moral good. Moralists are fond of such an interpretation, and it is a very interesting one. It puts beauty in the same relation to morals in which morals stand to pleasure and pain; both would be intuitions, qualitatively new, but with the same materials; they would be new perspectives of the same object.

But this theory is actually inadmissible. Innumerable æsthetic effects, indeed all specific and unmixed ones, are direct transmutations of pleasures and pains; they express nothing extrinsic to themselves, much less moral excellences. The detached lines of our figure signify nothing, but they are not absolutely uninteresting; the straight line is the simplest and not the least beautiful of forms. To say that it owes its interest to the thought of the economy of travelling over the shortest road, or of other practical advantages, would betray a feeble hold on psychological reality. The impression of a straight line differs in a certain almost emotional way from that of a curve, as those of various curves do from one another. The quality of the sensation is different, like that of various colours or sounds. To attribute the character of these forms to association would be like explaining sea-sickness as the fear of shipwreck. There is a distinct quality and value, often a singular beauty, in these simple lines that is intrinsic in the perception of their form.

It would be pedantic, perhaps, anywhere but in a treatise on aesthetics, to deny to this quality the name of expression; we might commonly say that the circle has one expression and the oval another. But what does the circle express except circularity, or the oval except the nature of the ellipse? Such expression expresses nothing; it is really impression. There may be analogy between it and other impressions; we may admit that odours, colours, and sounds correspond, and may mutually suggest one another; but this analogy is a superadded charm felt by very sensitive natures, and does not constitute the original value of the sensations. The common emotional tinge is rather what enables them to suggest one another, and what makes them comparable. Their expression, such as it is, is therefore due to the accident that both feelings have a kindred quality; and this quality has its effectiveness for sense independently of the perception of its recurrence in a different sphere. We shall accordingly take care to reserve the term “expression” for the suggestion of some other and assignable object, from which the expressive thing borrows an interest; and we shall speak of the intrinsic quality of forms as their emotional tinge or specific value.

The charm of a line evidently consists in the relation of its parts; in order to understand this interest in spatial relations, we must inquire how they are perceived.1 If the eye had its sensitive surface, the retina, exposed directly to the light, we could never have a perception of form any more than in the nose or ear, which also perceive the object through media. When the perception is not through a medium, but direct, as in the case of the skin, we might get a notion of form, because each point of the object would excite a single point in the skin, and as the sensations in different parts of the skin differ in quality, a manifold of sense, in which discrimination of parts would be involved, could be presented to the mind. But when the perception is through a medium, a difficulty arises.

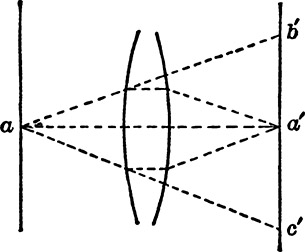

Any point, a, in the object will send a ray to every point, a,’ b,’ c’, of the sensitive surface; every point of the retina will therefore be similarly affected, since each will receive rays from every part of the object. If all the rays from one point of the object, a, are to be concentrated on a corresponding point of the retina, a’, which would then become the exclusive representative of a, we must have one or more refracting surfaces interposed, to gather the rays together. The presence of the lens, with its various coatings, has made representation of point by point possible for the eye. The absence of such an instrument makes the same sort of representation impossible to other senses, such as the nose, which does not smell in one place the effluvia of one part of the environment and in another place the effluvia of another, but smells indiscriminately the combination of all. Eyes without lenses like those possessed by some animals, undoubtedly give only a consciousness of diffused light, without the possibility of boundaries or divisions in the field of view. The abstraction of colour from form is therefore by no means an artificial one, since, by a simplification of the organ of sense, one may be perceived without the other.

But even if the lens enables the eye to receive a distributed image of the object, the manifold which consciousness would perceive would not be necessarily a manifold of parts juxtaposed in space. Each point of the retina might send to the brain a detached impression; these might be comparable, but not necessarily in their spatial position. The ear sends to the brain such a manifold of impressions (since the ear also has an apparatus by which various external differences in rapidity of vibrations are distributed into different parts of the organ). But this discriminated manifold is a manifold of pitches, not of positions. How does it happen that the manifold conveyed by the optic nerve appears in consciousness as spatial, and that the relation between its elements is seen as a relation of position?

An answer to this question has been suggested by various psychologists. The eye, by an instinctive movement, turns so as to bring every impression upon that point of the retina, near its centre, which has the acutest sensibility. A series of muscular sensations therefore always follows upon the conspicuous excitement of any outlying point. The object, as the eye brings it to the centre of vision, excites a series of points upon the retina; and the local sign, or peculiar quality of sensation, proper to each of these spots, is associated with that series of muscular feelings involved in turning the eyes. These feelings henceforth revive together; it is enough that a point in the periphery of the retina should receive a ray, for the mind to feel, together with that impression, the suggestion of a motion, and of the line of points that lies between the excited point and the centre of vision. A network of associations is thus formed, whereby the sensation of each retinal point is connected with all the others in a manner which is that of points in a plane. Every visible point becomes thus a point in a field, and has a felt radiation of lines of possible motion about it. Our notion of visual space has this origin, since the manifold of retinal impressions is distributed in a manner which serves as the type and exemplar of what we mean by a surface.

The reader will perhaps pardon these details and the strain they put on his attention, when he perceives how much they help us to understand the value of forms. The sense, then, of the position of any point consists in the tensions in the eye, that not only tends to bring that point to the cehtre of vision, but feels the suggestion of all the other points which are related to the given one in the web of visual experience. The definition of space as the possibility of motion is therefore an accurate and significant one, since the most direct and native perception of space we can have is the awakening of many tendencies to move our organs.

For example, if a circle is presented, the eye will fall upon its centre, as to the centre of gravity, as it were, of the balanced attractions of all the points; and there will be, in that position, an indifference and sameness of sensation, in whatever direction some accident moves the eye, that accounts very well for the emotional quality of the circle. It is a form which, although beautiful in its purity and simplicity, and wonderful in its continuity, lacks any stimulating quality, and is often ugly in the arts, especially when found in vertical surfaces where it is not always seen in perspective. For horizontal surfaces it is better because it is there always an ellipse to vision, and the ellipse has a less dull and stupefying effect. The eye can move easily, organize and subordinate its parts, and its relations to the environment are not similar in all directions. Small circles, like buttons, are not in the same danger of becoming ugly, because the eye considers them as points, and they diversify and help to divide surfaces, without appearing as surfaces themselves.

The straight line offers a curious object for analysis. It is not for the eye a very easy form to grasp. We bend it or we leave it. Unless it passes through the centre of vision, it is obviously a tangent to the points which have analogous relations to that centre. The local signs or tensions of the points in such a tangent vary in an unseizable progression; there is violence in keeping to it, and the effect is forced. This makes the dry and stiff quality of any long straight line, which the skilful Greeks avoided by the curves of their columns and entablatures, and the less economical barbarians by a profusion of interruptions and ornaments.

The straight line, when made the direct object of attention, is, of course, followed by the eye and not seen by the outlying parts of the retina in one eccentric position. The same explanation is good for this more common case, since the consciousness that the eye travels in a straight line consists in the surviving sense of the previous position, and in the manner in which the tensions of these various positions overlap. If the tensions change from moment to moment entirely, we have a broken, a fragmentary effect, as that of zigzag, where all is dropping and picking up again of associated motions; in the straight line, much prolonged, we have a gradual and inexorable rending of these tendencies to associated movements.

In the curves we call flowing and graceful, we have, on the contrary, a more natural and rhythmical set of movements in the optic muscles; and certain points in the various gyrations make rhymes and assonances, as it were, to the eye that reaches them. We find ourselves at every turn reawakening, with a variation, the sense of the previous position. It is easy to understand by analogy with the superficially observed conditions of pleasure, that such rhythms and harmonies should be delightful. The deeper question of the physical basis of pleasure we have not intended to discuss. Suffice it that measure, in quantity, in intensity, and in time, must involve that physiological process, whatever it may be, the consciousness of which is pleasure.

An important exemplification of these physiological principles is found in the charm of symmetry. When for any reason the eye is to be habitually directed to a single point, as to the opening of a gate or window, to an altar, a throne, a stage, or a fireplace, there will be violence and distraction caused by the tendency to look aside in the recurring necessity of looking forward, if the object is not so arranged that the tensions of eye are balanced, and the centre of gravity of vision lies in the point which one is obliged to keep in sight. In all such objects we therefore require bilateral symmetry. The necessity of vertical symmetry is not felt because the eyes and head do not so readily survey objects from top to bottom as from side to side. The inequality of the upper and lower parts does not generate the same tendency to motion, the same restlessness, as does the inequality of the right and left sides of an object in front of us. The comfort and economy that comes from muscular balance in the eye, is therefore in some cases the source of the value of symmetry.1

In other cases symmetry appeals to us through the charm of recognition and rhythm. When the eye runs over a facade, and finds the objects that attract it at equal intervals, an expectation, like the anticipation of an inevitable note or requisite word, arises in the mind, and its non-satisfaction involves a shock. This shock, if caused by the emphatic emergence of an interesting object, gives the effect of the picturesque; but when it comes with no compensation, it gives us the feeling of ugliness and imperfection—the defect which symmetry avoids. This kind of symmetry is accordingly in itself a negative merit, but often the condition of the greatest of all merits,—the permanent power to please. It contributes to that completeness which delights without stimulating, and to which our jaded senses return gladly, after all sorts of extravagances, as to a kind of domestic peace. The inwardness and solidity of this quiet beauty comes from the intrinsic character of the pleasure which makes it up. It is no adventitious charm; but the eye in its continual passage over the object finds always the same response, the same adequacy; and the very process of perception is made delightful by the object’s fitness to be perceived. The parts, thus coalescing, form a single object, the unity and simplicity of which are based upon the rhythm and correspondence of its elements.

Symmetry is here what metaphysicians call a principle of individuation. By the emphasis which it lays upon the recurring elements, it cuts up the field into determinate units; all that lies between the beats is one interval, one individual. If there were no recurrent impressions, no corresponding points, the field of perception would remain a fluid continuum, without defined and recognizable divisions. The outlines of most things are symmetrical because we choose what symmetrical lines we find to be the boundaries of objects. Their symmetry is the condition of their unity, and their unity of their individuality and separate existence.

Experience, to be sure, can teach us to regard unsymmetrical objects as wholes, because their elements move and change together in nature; but this is a principle of individuation, a posteriori, founded on the association of recognized elements. These elements, to be recognized and seen to go together and form one thing, must first be somehow discriminated; and the symmetry, either of their parts, or of their position as wholes, may enable us to fix their boundaries and to observe their number. The category of unity, which we are so constantly imposing upon nature and its parts, has symmetry, then, for one of its instruments, for one of its bases of application.

If symmetry, then, is a principle of individuation and helps us to distinguish objects, we cannot wonder that it helps us to enjoy the perception. For our intelligence loves to perceive; water is not more grateful to a parched throat than a principle of comprehension to a confused understanding. Symmetry clarifies, and we all know that light is sweet. At the same time, we can see why there are limits to the value of symmetry. In objects, for instance, that are too small cr too diffused for composition, symmetry has no value. In an avenue symmetry is stately and impressive, but in a large park, or in the plan of a city, or the side wall of a gallery it produces monotony in the various views rather than unity in any one of them. Greek temples, never being very large, were symmetrical on all their facades; Gothic churches were generally designed to be symmetrical only in the west front, and in the transepts, while the side elevation as a whole was eccentric. This was probably an accident, due to the demands of the interior arrangement; but it was a fortunate one, as we may see by contrasting its effect with that of our stations, exhibition buildings, and other vast structures, where symmetry is generally introduced even in the most extensive faqades which, being too much prolonged for their height, cannot be treated as units. The eye is not able to take them in at a glance, and does not get the effect of repose from the balance of the extremes, while the mechanical sameness of the sections, surveyed in succession, makes the impression of an unmeaning poverty of resource.

Symmetry thus loses its value when it cannot, on account of the size of the object, contribute to the unity of our perception. The synthesis which it facilitates must be instantaneous. If the comprehension by which we unify our object is discursive, as, for instance, in conceiving the arrangement and numbering of the streets of New York, or the plan of the Escurial, the advantage of symmetry is an intellectual one; we can better imagine the relations of the parts, and draw a map of the whole in the fancy; but there is no advantage to direct perception, and therefore no added beauty. Symmetry is superfluous in those objects. Similarly animal and vegetable forms gain nothing by being symmetrically displayed, if the sense of their life and motion is to be given. When, however, these forms are used for mere decoration, not for the expression of their own vitality, then symmetry is again required to accentuate their unity and organization. This justifies the habit of conventionalizing natural forms, and the tendency of some kinds of hieratic art, like the Byzantine or Egyptian, to affect a rigid symmetry of posture. We can thereby increase the unity and force of the image without suggesting that individual life and mobility, which would interfere with the religious function of the object, as the symbol and embodiment of an impersonal faith.

Symmetry is evidently a kind of unity in variety, where a whole is determined by the rhythmic repetition of similars. We have seen that it has a value where it is an aid to unification. Unity would thus appear to be the virtue of forms; but a moment’s reflection will show us that unity cannot be absolute and be a form; a form is an aggregation, it must have elements, and the manner in which the elements are combined constitutes the character of the form. A perfectly simple perception, in which there was no consciousness of the distinction and relation of parts, would not be a perception of form; it would be a sensation. Physiologically these sensations may be aggregates and their values, as in the case of musical tones, may differ according to the manner in which certain elements, beats, vibrations, nervous processes, or what not, are combined; but for consciousness the result is simple, and the value is the pleasantness of a datum and not of a process. Form, therefore, does not appeal to the unattentive; they get from objects only a vague sensation which may in them awaken extrinsic associations; they do not stop to survey the parts or to appreciate their relation, and consequently are insensible to the various charms of various unifications; they can find in objects only the value of material or of function, not that of form.

Beauty of form, however, is what specifically appeals to an æsthetic nature; it is equally removed from the crudity of formless stimulation and from the emotional looseness of reverie and discursive thought. The indulgence in sentiment and suggestion, of which our time is fond, to the sacrifice of formal beauty, marks an absence of cultivation as real, if not as confessed, as that of the barbarian who revels in gorgeous confusion.

The synthesis, then, which constitutes form is an activity of the mind; the unity arises consciously, and is an insight into the relation of sensible elements separately perceived. It differs from sensation in the consciousness of the synthesis, and from expression in the homogeneity of the elements, and in their common presence to sense.

The variety of forms depends upon the character of the elements and on the variety of possible methods of unification. The elements may be all alike, and their only diversity be numerical. Their unity will then be merely the sense of their uniformity.1 Or they may differ in kind, but so as to compel the mind to no particular order in their unification. Or they may finally be so constituted that they suggest inevitably the scheme of their unity; in this case there is organization in the object, and the synthesis of its parts is one and pre-determinate. We shall discuss these various forms in succession, pointing out the effects proper to each.

The radical and typical case of the first kind of unity in variety is found in the perception of extension itself. This perception, if we look to its origin, may turn out to be primitive; no doubt the feeling of “crude extensity” is an original sensation; every inference, association, and distinction is a thing that looms up suddenly before the mind, and the nature and actuality of which is a datum of what—to indicate its irresistible immediacy and indescribability—we may well call sense. Forms are seen, and if we think of the origin of the perception, we may well call this vision a sensation. The distinction between a sensation of form, however, and one which is formless, regards the content and character, not the genesis of the perception. A distinction and association, or an inference, is a direct experience, a sensible fact; but it is the experience of a process, of a motion between two terms, and a consciousness of their coexistence and distinction; it is a feeling of relation. Now the sense of space is a feeling of this kind; the essence of it is the realization of a variety of directions and of possible motions, by which the relation of point to point is vaguely but inevitably given. The perception of extension is therefore a perception of form, although of the most rudimentary kind. It is merely Auseinandersein, and we might call it the materia prima of form, were it not capable of existing without further determination. For we can have the sense of space without the sense of boundaries; indeed, this intuition is what tempts us to declare space infinite. Space would have to consist of a finite number of juxtaposed blocks, if our experience of extension carried with it essentially the realization of limits.

The æsthetic effect of extensiveness is also entirely different from that of particular shapes. Some things appeal to us by their surfaces, others by the lines that limit those surfaces. And this effect of surface is not necessarily an effect of material or colour; the evenness, monotony, and vastness of a great curtain of colour produce an effect which is that of the extreme of uniformity in the extreme of multiplicity; the eye wanders over a fluid infinity of unrecognizable positions, and the sense of their numberlessness and continuity is precisely the source of the emotion of extent. The emotion is primary and has undoubtedly a physiological ground, while the idea of size is secondary and involves associations and inferences. A small photograph of St. Peter’s gives the idea of size; as does a distant view of the same object. But this is of course dependent on our realization of the distance, or of the scale of the representation. The value of size becomes immediate only when we are at close quarters with the object; then the surfaces really subtend a large angle in the field of vision, and the sense of vastness establishes its standard, which can afterwards be applied to other objects by analogy and contrast. There is also, to be sure, a moral and practical import in the known size of objects, which, by association, determines their dignity; but the pure sense of extension, based upon the attack of the object upon the apperceptive resources of the eye, is the truly æsthetic value which it concerns us to point out here, as the most rudimentary example of form.

Although, the effect of extension is not that of material, the two are best seen in conjunction. Material must appear in some form; but when its beauty is to be made prominent, it is well that this form should attract attention as little as possible to itself. Now, of all forms, absolute uniformity in extension is the simplest and most allied to the material; it gives the latter only just enough form to make it real and perceptible. Very rich and beautiful materials therefore do well to assume this form. You will spoil the beauty you have by superimposing another; as if you make a statue of gold, or flute a jasper column, or bedeck a velvet cloak. The beauty of staffs appears when they are plain. Even stone gives its specific quality best in great unbroken spaces of wall; the simplicity of the form emphasizes the substance. And again, the effect of extensity is never long satisfactory unless it is superinduced upon some material beauty; the dignity of great hangings would suffer if they were not of damask, but of cotton, and the vast smoothness of the sky would grow oppressive if it were not of so tender a blue.

Another beauty of the sky—the stars—offers so striking and fasci nating an illustration of the effect of multiplicity in uniformity, that I am tempted to analyze it at some length. To most people, I fancy, the stars are beautiful; but if you asked why, they would be at a loss to reply, until they remembered what they had heard about astronomy, and the great size and distance and possible habitation of those orbs. The vague and illusive ideas thus aroused fall in so well with the dumb emotion we were already feeling, that we attribute this emotion to those ideas, and persuade ourselves that the power of the starry heavens lies in the suggestion of astronomical facts.

The idea of the insignificance of our earth and of the incomprehensible multiplicity of worlds is indeed immensely impressive; it may even be intensely disagreeable. There is something baffling about infinity; in its presence the sense of finite humility can never wholly banish the rebellious suspicion that we are being deluded. Our mathematical imagination is put on the rack by an attempted conception that has all the anguish of a nightmare and probably, could we but awake, all its laughable absurdity. But the obsession of this dream is an intellectual puzzle, not an æsthetic delight. It is not essential to our admiration. Before the days of Kepler the heavens declared the glory of the Lord; and we needed no calculation of stellar distances, no fancies about a plurality of worlds, no image of infinite spaces, to make the stars sublime.

Had we been taught to believe that the stars governed our fortunes, and were we reminded of fate whenever we looked at them, we should similarly tend to imagine that this belief was the source of their sublimity; and, if the superstition were dispelled, we should think the interest gone from the apparition. But experience would soon undeceive us, and prove to us that the sensuous character of the object was sublime in itself. Indeed, on account of that intrinsic sublimity the sky can be fitly chosen as a symbol for a sublime conception; the common quality in both makes each suggest the other. For that reason, too, the parable of the natal stars governing our lives is such a natural one to express our subjection to circumstances, and can be transformed by the stupidity of disciples into a literal tenet. In the same way, the kinship of the emotion produced by the stars with the emotion proper to certain religious moments makes the stars seem a religious object. They become, like impressive music, a stimulus to worship. But fortunately there are experiences which remain untouched by theory, and which maintain the mutual intelligence of men through the estrangements wrought by intellectual and religious systems. When the superstructures crumble, the common foundation of human sentience and imagination is exposed beneath.

The intellectual suggestion of the infinity of nature can, moreover, be awakened by other experiences which are by no means sublime. A heap of sand will involve infinity as surely as a universe of suns and planets. Any object is infinitely divisible and, when we press the thought, can contain as many worlds with as many winged monsters and ideal republics as can the satellites of Sirius. But the infinitesimal does not move us æsthetically; it can only awaken an amused curiosity. The difference cannot lie in the import of the idea, which, is objectively the same in both cases. It lies in the different immediate effect of the crude images which give us the type and meaning of each; the crude image that underlies the idea of the infinitesimal is the dot, the poorest and most uninteresting of impressions; while the crude image that underlies the idea of infinity is space, multiplicity in uniformity, and this, as we have seen, has a powerful effect on account of the breadth, volume, and omnipresence of the stimulation. Every point in the retina is evenly excited, and the local signs of all are simultaneously felt. This equable tension, this balance and elasticity in the very absence of fixity, give the vague but powerful feeling that we wish to describe. Did not the infinite, by this initial assault upon our senses, awe us and overwhelm us, as solemn music might, the idea of it would be abstract and moral like that of the infinitesimal, and nothing but an amusing curiosity.

Nothing is objectively impressive; things are impressive only when they succeed in touching the sensibility of the observer, by finding the avenues to his brain and heart. The idea that the universe is a multitude of minute spheres circling, like specks of dust, in a dark and boundless void, might leave us cold and indifferent, if not bored and depressed, were it not that we identify this hypothetical scheme with the visible splendour, the poignant intensity, and the baffling number of the stars. So far is the object from giving value to the impression, that it is here, as it must always ultimately be, the impression that gives value to the object. For all worth leads us back to actual feeling somewhere, or else evaporates into nothing—into a word and a superstition.

Now, the starry heavens are very happily designed to intensify the sensations on which their beauties must rest. In the first place, the continuum of space is broken into points, numerous enough to give the utmost idea of multiplicity, and yet so distinct and vivid that it is impossible not to remain aware of their individuality. The variety of local signs, without becoming organized into forms, remains prominent and irreducible. This makes the object infinitely more exciting than a plane surface would be. In the second place, the sensuous contrast of the dark background,—blacker the clearer the night and the more stars we can see,—with the palpitating fire of the stars themselves, could not be exceeded by any possible device. This material beauty adds incalculably, as we have already pointed out, to the inwardness and sublimity of the effect. To realize the great importance of these two elements, we need but to conceive their absence, and observe the change in the dignity of the result.

Fancy a map of the heavens and every star plotted upon it, even those invisible to the naked eye: why would this object, as full of scientific suggestion surely as the reality, leave us so comparatively cold? Quite indifferent it might not leave us, for I have myself watched stellar photographs with almost inexhaustible wonder. The sense of multiplicity is naturally in no way diminished by tlie representation; but the poignancy of the sensation, the life of the light, are gone; and with the dulled impression the keenness of the emotion disappears. Or imagine the stars, undiminished in number, without losing any of their astronomical significance and divine immutability, marshalled in geometrical patterns; say in a Latin cross, with the words In hoc signo vinces in a scroll around them. The beauty of the illumination would be perhaps increased, and its import, practical, religious, and cosmic, would surely be a little plainer; but where would be the sublimity of the spectacle? Irretrievably lost: and lost because the form of the object would no longer tantalize us with its sheer multiplicity, and with the consequent overpowering sense of suspense and awe.

In a word, the infinity which moves us is the sense of multiplicity in uniformity. Accordingly things which have enough multiplicity, as the lights of a city seen across water, have an effect similar to that of the stars, if less intense; whereas a star, if alone, because the multiplicity is lacking, makes a wholly different impression. The single star is tender, beautiful, and mild; we can compare it to the humblest and sweetest of things:

A violet by a mossy stone

Half hidden from the eye,

Fair as a star when only one

Is shining in the sky.

It is, not only in fact but in nature, an attendant on the moon, associated with the moon, if we may be so prosaic here, not only by contiguity but also by similarity.

Fairer than Phoebe’s sapphire-regioned star

Or vesper, amorous glow-worm of the sky.

The same poet can say elsewhere of a passionate lover:

He arose

Ethereal, flushed, and like a throbbing star,

Amid the sapphire heaven’s deep repose.

How opposite is all this from the cold glitter, the cruel and mysterious sublimity of the stars when they are many! With these we have no Sapphic associations; they make us think rather of Kant who could hit on nothing else to compare with his categorical imperative, perhaps because he found in both the same baffling incomprehensibility and the same fierce actuality. Such ultimate feelings are sensations of physical tension.

This long analysis will be a sufficient illustration of the power of multiplicity in uniformity; we may now proceed to point out the limitations inherent in this form. The most obvious one is that of monotony; a file of soldiers or an iron railing is impressive in its way, but cannot long entertain us, nor hold us with that depth of developing interest, with which we might study a crowd or a forest of trees.

The tendency of monotony is double, and in two directions deadens our pleasure. When the repeated impressions are acute, and cannot be forgotten in tlieir endless repetition, their monotony becomes painful. The constant appeal to the same sense, the constant requirement of the same reaction, tires the system, and we long for change as for a relief. If the repeated stimulations are not very acute, we soon become unconscious of them; like the ticking of the clock, they become merely a factor in our bodily tone, a cause, as the case may be, of a diffused pleasure or unrest; but they cease to present a distinguishable object.

The pleasures, therefore, which a kindly but monotonous environment produces, often fail to make it beautiful, for the simple reason that the environment is not perceived. Likewise the hideousness of things to which we are accustomed—the blemishes of the landscape, the ugliness of our clothes or of our walls—do not oppress us, not so much because we do not see the ugliness as because we overlook the things. The beauties or defects of monotonous objects are easily lost, because the objects are themselves intermittent in consciousness. But it is of some practical importance to remark that this indifference of monotonous values is more apparent than real. The particular object ceases to be of consequence; but the congruity of its structure and quality with our faculties of perception remains, and its presence in our environment is still a constant source of vague irritation and friction, or of subtle and pervasive delight. And this value, although not associated with the image of the monotonous object, lies there in our mind, like all the vital and systemic feelings, ready to enhance the beauty of any object that arouses our attention, and meantime adding to the health and freedom of our life—making whatever we do a little easier and pleasanter for us. A grateful environment is a substitute for happiness. It can quicken us from without as a fixed hope and affection, or the consciousness of a right life, can quicken us from within. To humanize our surroundings is, therefore, a task which should interest the physicians both of soul and body.

But the monotony of multiplicity is not merely intrinsic in the form; what is perhaps even of greater consequence in the arts is the fact that its capacity for association is restricted. What is in itself uniform cannot have a great diversity of relations. Hence the dryness, the crisp definiteness and hardness, of those products of art which contain an endless repetition of the same elements. Their affinities are necessarily few; they are not fit for many uses, nor capable of expressing many ideas. The heroic couplet, now too much derided, is a form of this kind. Its compactness and inevitableness make it excellent for an epigram and adequate it for a satire, but its perpetual snap and unvarying rhythm are thin for an epic, and impossible for a song. The Greek colonnade, a form in many ways analogous, has similar limitations. Beautiful with a finished and restrained beauty, which our taste is hardly refined enough to appreciate, it is incapable of development. The experiments of Roman architecture sufficiently show it; the glory of which is their Koman frame rather than their Hellenic ornament.

When the Greeks themselves had to face the problem of larger and more complex buildings, in the service of a supernatural and hierarchical system, they transformed their architecture into what we call Byzantine, and St. Sophia took the place of the Parthenon. Here a vast vault was introduced, the colonnade disappeared, the architrave was rounded into an arch from column to column, the capitals of these were changed from concave to convex, and a thousand other changes in structure and ornament introduced flexibility and variety. Architecture could in this way, precisely because more vague and barbarous, better adapt itself to the conditions of the new epoch. Perfect taste is itself a limitation, not because it intentionally excludes any excellence, but because it impedes the wandering of the arts into those bypaths of caprice and grotesqueness in which, although at the sacrifice of formal beauty, interesting partial effects might still be discovered. And this objection applies with double force to the first crystallizations of taste, when tradition has carried us but a little way in the right direction. The authorized effects are then very simple, and if we allow no others, our art becomes wholly inadequate to the functions ultimately imposed upon it. Primitive arts might furnish examples, but the state of English poetry at the time of Queen Anne is a sufficient illustration of this possibility. The French classicism, of which the English school was an echo, was more vital and human, because it embodied a more native taste and a wider training.

It would be an error to suppose that æsthetic principles apply only to our judgments of works of art or of those natural objects which we attend to chiefly on account of their beauty. Every idea which is formed in the human mind, every activity and emotion, has some relation, direct or indirect, to pain and pleasure. If, as is the case in all the more important instances, these fluid activities and emotions precipitate, as it were, in their evanescence certain psychical solids called ideas of things, then the concomitant pleasures are incorporated more or less in those concrete ideas and the things acquire an æsthetic colouring. And although this æsthetic colouring may be the last quality we notice in objects of practical interest, its influence upon us is none the less real, and often accounts for a great deal in our moral and practical attitude.

In the leading political and moral idea of our time, in the idea of democracy, I think there is a strong æsthetic ingredient, and the power of the idea of democracy over the imagination is an illustration of that effect of multiplicity in uniformity which we have been studying. Of course, nothing could be more absurd than to suggest that the French Revolution, with its immense implications, had an æsthetic preference for its basis 5 it sprang, as we know, from the hatred of oppression, the rivalry of classes, and the aspiration after a freer social and strictly moral organization. But when these moral forces were suggesting and partly realizing the democratic idea, this idea was necessarily vividly present to men’s thoughts; the picture of human life which it presented was becoming familiar, and was being made the sanction and goal of constant endeavour. Nothing so much enhances a good as to make sacrifices for it. The consequence was that democracy, prized at first as a means to happiness and as an instrument of good government, was acquiring an intrinsic value; it was beginning to seem good in itself, in fact, the only intrinsically right and perfect arrangement. A utilitarian scheme was receiving an æsthetic consecration. That which was happening to democracy had happened before to the feudal and royalist systems; they too had come to be prized in themselves, for the pleasure men took in thinking of society organized in such an ancient, and thereby to their fancy, appropriate and beautiful manner. The practical value of the arrangement, on which, of course, it is entirely dependent for its origin and authority, was forgotten, and men were ready to sacrifice their welfare to their sense of propriety; that is, they allowed an æsthetic good to outweigh a practical one. That seems now a superstition, although, indeed, a very natural and even noble one. Equally natural and noble, but no less superstitious, is our own belief in the divine right of democracy. Its essential right is something purely æsthetic.

Such æsthetic love of uniformity, however, is usually disguised under some moral label: we call it the love of justice, perhaps because we have not considered that the value of justice also, in so far as it is not derivative and utilitarian, must be intrinsic, or, what is practically the same thing, æsthetic. But occasionally the beauties of democracy are presented to us undisguised. The writings of Walt Whitman are a notable example. Never, perhaps, has the charm of uniformity in multiplicity been felt so completely and so exclusively. Everywhere it greets us with a passionate preference; not flowers but leaves of grass, not music but drum-taps, not composition but aggregation, not the hero but the average man, not the crisis but the vulgarest moment; and by this resolute marshalling of nullities, by this effort to show us everything as a momentary pulsation of a liquid and structureless whole, he profoundly stirs the imagination. We may wish to dislike this power, but, I think, we must inwardly admire it. For whatever practical dangers we may see in this terrible levelling, our æsthetic faculty can condemn no actual effect; its privilege is to be pleased by opposites, and to be capable of finding chaos sublime without ceasing to make nature beautiful.

It is time we should return to the consideration of abstract forms. Nearest in nature to the example of uniformity in multiplicity, we found those objects, like a reversible pattern, that having some variety of parts invite us to survey them in different orders, and so bring into play in a marked manner the faculty of apperception.

There is in the senses, as we have seen, a certain form of stimulation, a certain measure and rhythm of waves with which the æsthetic value of the sensation is connected. So when, in the perception of the object, a notable contribution is made by memory and mental habit, the value of tlie perception will be due, not only to the pleasantness of the external stimulus, but also to the pleasantness of the apperceptive reaction; and the latter source of value will be more important in proportion as the object perceived is more dependent, for the form and meaning it presents, upon our past experience and imaginative trend, and less on the structure of the external object.

Our apperception of form varies not only with our constitution, age, and health, as does the appreciation of sensuous values, but also with our education and genius. The more indeterminate the object, the greater share must subjective forces have in determining our perception; for, of course, every perception is in itself perfectly specific, and can be called indefinite only in reference to an abstract ideal which it is expected to approach. Every cloud has just the outline it has, although we may call it vague, because we cannot classify its form under any geometrical or animal species; it would be first definitely a whale, and then would become indefinite until we saw our way to calling it a camel. But while in the intermediate stage, the cloud would be a form in the perception of which there would be little apperceptive activity, little reaction from the store of our experience, little sense of form; its value would be in its colour and transparency, and in the suggestion of lightness and of complex but gentle movement.

But the moment we said “Yes, very like a whale,” a new kind of value would appear; the cloud could now be beautiful or ugly, not as a cloud merely, but as a whale. We do not speak now of the associations of the idea, as with the sea, or fishermen’s yarns; that is an extrinsic matter of expression. We speak simply of the intrinsic value of the form of the whale, of its lines, its movement, its proportion. This is a more or less individual set of images which are revived in the act of recognition; this revival constitutes the recognition, and the beauty of the form is the pleasure of that revival. A certain musical phrase, as it were, is played in the brain; the awakening of that echo is the act of apperception and the harmony of the present stimulation with the form of that phrase; the power of this particular object to develope and intensify that generic phrase in the direction of pleasure, is the test of the formal beauty of this example. For these cerebral phrases have a certain rhythm; this rhythm can, by the influence of the stimulus that now reawakens it, be marred or enriched, be made more or less marked and delicate; and as this conflict or reinforcement comes, the object is ugly or beautiful in form.

Such an æsthetic value is thus dependent on two things. The first is the acquired character of the apperceptive form evoked; it may be a cadenza or a trill, a major or a minor chord, a rose or a violet, a goddess or a dairy-maid; and as one or another of these is recognized, an aesthetic dignity and tone is given to the object. But it will be noticed that in such mere recognition very little pleasure is found, or, what is the same thing, different aesthetic types in the abstract have little difference in intrinsic beauty. The great difference lies in their affinities. What will decide us to like or not to like the type of our apperception will be not so much what this type is, as its fitness to the context of our mind. It is like a word in a poem, more effective by its fitness than by its intrinsic beauty, although that is requisite too. We can be shocked at an incongruity of natures more than we can be pleased by the intrinsic beauty of each nature apart, so long, that is, as they remain abstract natures, objects recognized without being studied. The aesthetic dignity of the form, then, tells us the kind of beauty we are to expect, affects us by its welcome or unwelcome promise, but hardly gives us a positive pleasure in the beauty itself.

Now this is the first thing in the value of a form, the value of the type as such; the second and more important element is the relation of the particular impression to the form under which it is apperceived. This determines the value of the object as an example of its class. After our mind is pitched to the key and rhythm of a certain idea, say of a queen, it remains for the impression to fulfil, aggrandize, or enrich this form by a sympathetic embodiment of it. Then we have a queen that is truly royal. But if instead there is disappointment, if this particular queen is an ugly one, although perhaps she might have pleased as a witch, this is because the apperceptive form and the impression give a cerebral discord. The object is unideal, that is, the novel, external element is inharmonious with the revived and internal element by suggesting which the object has been apperceived.

A most important thing, therefore, in the perception of form is the formation of types in our mind, with reference to which examples are to be judged. I say the formation of them, for we can hardly consider the theory that they are eternal as a possible one in psychology. The Platonic doctrine on that point is a striking illustration of an equivocation we mentioned in the beginning;1 namely, that the import of an experience is regarded as a manifestation of its cause—the product of a faculty substituted for the description of its function. Eternal types are the instrument of æsthetic life, not its foundation. Take the æsthetic attitude, and you have for the moment an eternal idea; an idea, I mean, that you treat as an absolute standard, just as when you take the perceptive attitude you have an external object which you treat as an absolute existence. But the æsthetic, like the perceptive faculty, can be made an object of study in turn, and its theory can be sought; and then the eternal idea, like the external object, is seen to be a product of human nature, a symbol of experience, and an instrument of thought.

The question whether there are not, in external nature or in the mind of God, objects and eternal types, is indeed not settled, it is not even touched by this inquiry; but it is indirectly shown to be futile, because such transcendent realities, if they exist, can have nothing to do with our ideas of them. The Platonic idea of a tree may exist; how should I deny it? How should I deny that I might some day find myself outside the sky gazing at it, and feeling that I, with my mental vision, am beholding the plenitude of arboreal beauty, perceived in this world only as a vague essence haunting the multiplicity of finite trees? But what can that have to do with my actual sense of what a tree should be? Shall we take the Platonic myth literally, and say the idea is a memory of the tree I have already seen in heaven? How else establish any relation between that eternal object and the type in my mind? But why, in that case, this infinite variability of ideal trees? Was the Tree Beautiful an oak, or a cedar, an English or an American elm? My actual types are finite and mutually exclusive; that heavenly type must be one and infinite. The problem is hopeless.

Very simple, on the other hand, is the explanation of the existence of that type as a residuum of experience. Our idea of an individual thing is a compound and residuum of our several experiences of it; and in the same manner our idea of a class is a compound and residuum of our ideas of the particulars that compose it. Particular impressions have, by virtue of their intrinsic similarity or of the identity of their relations, a tendency to be merged and identified, so that many individual perceptions leave but a single blurred memory that stands for them all, because it combines their several associations. Similarly, when various objects have many common characteristics, the mind is incapable of keeping them apart. It cannot hold clearly so great a multitude of distinctions and relations as would be involved in naming and conceiving separately each grain of sand, or drop of water, each fly or horse or man that we have ever seen. The mass of our experience has therefore to be classified, if it is to be available at all. Instead of a distinct image to represent each of our original impressions, we have a general resultant—a composite photograph—of those impressions.

This resultant image is the idea of the class. It often has very few, if any, of the sensible properties of the particulars that underlie it, often an artificial symbol—the sound of a word—is the only element, present to all the instances, which the generic image clearly contains. For, of course, the reason why a name can represent a class of objects is that the name is the most conspicuous element of identity in the various experiences of objects in that class. We have seen many horses, but if we are not lovers of the animal, nor particularly keen observers, very likely we retain no clear image of all that mass of impressions except the reverberation of the sound “horse,” which really or mentally has accompanied all those impressions. This sound, therefore, is the content of our general idea, and to it cling all the associations which constitute our sense of what the word means. But a person with a memory predominantly visual would probably add to this remembered sound a more or less detailed image of the animal; some particular horse in some particular attitude might possibly be recalled, but more probably some imaginative construction, some dream image, would accompany the sound. An image which reproduced no particular horse exactly, but which was a spontaneous fiction of the fancy, would serve, by virtue of its felt relations, the same purpose as the sound itself. Such a spontaneous image would be, of course, variable. In fact, no image can, strictly speaking, ever recur. But these percepts, as they are called, springing up in the mind like flowers from the buried seeds of past experience, would inherit all the powers of suggestion which are required by any instrument of classification.

These powers of suggestion have probably a cerebral basis. The new percept—the generic idea—repeats to a great extent, both in nature and localization, the excitement constituting the various original impressions; as the percept reproduces more or less of these it will be a more or less full and impartial representative of them. Not all the suggestions of a word or image are equally ripe. A generic idea or type usually presents to us a very inadequate and biassed view of the field it means to cover. As we reflect and seek to correct this inadequacy, the percept changes on our hands. The very consciousness that other individuals and other qualities fall under our concept, changes this concept, as a psychological presence, and alters its distinctness and extent. When I remember, to use a classical example, that the triangle is not isosceles, nor scalene, nor rectangular, but each and all of those, I reduce my percept to the word and its definition, with perhaps a sense of the general motion of the hand and eye by which we trace a three-cornered figure.

Since the production of a general idea is thus a matter of subjective bias, we cannot expect that a type should be the exact average of the examples from which it is drawn. In a rough way, it is the average; a fact that in itself is the strongest of arguments against the independence or priority of the general idea. The beautiful horse, the beautiful speech, the beautiful face, is always a medium between the extremes which our experience has offered. It is enough that a given characteristic should be generally present in our experience, for it to become an indispensable element of the ideal. There is nothing in itself beautiful or necessary in the shape of the human ear, or in the presence of nails on the fingers and toes; but the ideal of man, which the preposterous conceit of our judgment makes us set up as divine and eternal, requires these precise details; without them the human form would be repulsively ugly.

It often, happens that the accidents of experience make us in this way introduce into the ideal, elements which, if they could be excluded without disgusting us, would make possible satisfactions greater than those we can now enjoy. Thus the taste formed by one school of art may condemn the greater beauties created by another. In morals we have the same phenomenon. A barbarous ideal of life requires tasks and dangers incompatible with happiness; a rude and oppressed conscience is incapable of regarding as good a state which excludes its own acrid satisfactions. So, too, a fanatical imagination cannot regard God as just unless he is represented as infinitely cruel. The purpose of education is, of course, to free us from these prejudices, and to develope our ideals in the direction of the greatest possible good. Evidently the ideal has been formed by the habit of perception; it is, in a rough way, that average form which we expect and most readily apperceive. The propriety and necessity of it is entirely relative to our experience and faculty of apperception. The shock of surprise, the incongruity with the formed percept, is the essence and measure of ugliness.

Nevertheless we do not form æsthetic ideals any more than other general types, entirely without bias. We have already observed that a percept seldom gives an impartial compound of the objects of which it is the generic image. This partiality is due to a variety of circumstances. One is the unequal accuracy of our observation. If some interest directs our attention to a particular quality of objects, that quality will be prominent in our percept; it may even be the only content clearly given in our general idea; and any object, however similar in other respects to those of the given class, will at once be distinguished as belonging to a different species if it lacks that characteristic on which our attention is particularly fixed. Our percepts are thus habitually biassed in the direction of practical interest, if practical interest does not indeed entirely govern their formation. In the same manner, our aesthetic ideals are biassed in the direction of aesthetic interest. Not all parts of an object are equally congruous with our perceptive faculty; not all elements are noted with the same pleasure. Those, therefore, which are agreeable are chiefly dwelt upon by the lover of beauty, and his percept will give an average of things with a great emphasis laid on that part of them which is beautiful. The ideal will thus deviate from the average in the direction of the observer’s pleasure.

For this reason the world is so much more beautiful to a poet or an artist than to an ordinary man. Each object, as his aesthetic sense is developed, is perhaps less beautiful than to the uncritical eye; his taste becomes difficult, and only the very best gives him unalloyed satisfaction. But while each work of nature and art is thus apparently blighted by his greater demands and keener susceptibility, the world itself, and the various natures it contains, are to him unspeakably beautiful. The more blemishes he can see in men, the more excellence he sees in man, and the more bitterly he laments the fate of each particular soul, the more reverence and love he has for the soul in its ideal essence. Criticism and idealization involve each other. The habit of looking for beauty in everything makes us notice the shortcomings of things; our sense, hungry for complete satisfaction, misses the perfection it demands. But this demand for perfection becomes at the same time the nucleus of our observation; from every side a quick affinity draws what is beautiful together and stores it in the mind, giving body there to the blind yearnings of our nature. Many imperfect things crystallize into a single perfection. The mind is thus peopled by general ideas in which beauty is the chief quality; and these ideas are at the same time the types of things. The type is still a natural resultant of particular impressions; but the formation of it has been guided by a deep subjective bias in favour of what has delighted the eye.

This theory can be easily tested by asking whether, in the case where the ideal differs from the average form of objects, this variation is not due to the intrinsic pleasantness or impressiveness of the quality exaggerated. For instance, in the human form, the ideal differs immensely from the average. In many respects the extreme or something near it is the most beautiful. Xenophon describes the women of Armenia as κaλλaì κaì μϵáλal, and we should still speak of one as fair and tall and of another as fair but little. Size is therefore, even where least requisite, a thing in which the ideal exceeds the average. And the reason—apart from associations of strength—is that unusual size makes things conspicuous. The first prerequisite of effect is impression, and size helps that; therefore in the æsthetic ideal the average will be modified by being enlarged, because that is a change in the direction of our pleasure, and size will be an element of beauty.1

Similarly the eyes, in themselves beautiful, will be enlarged also; and generally whatever makes by its sensuous quality, by its abstract form, or by its expression, a particular appeal to our attention and contribution to our delight, will count for more in the ideal type than its frequency would warrant. The generic image has been constructed under the influence of a selective attention, bent upon æsthetic worth.

To praise any object for approaching the ideal of its kind is therefore only a roundabout way of specifying its intrinsic merit and expressing its direct effect on our sensibility. If in referring to the ideal we were not thus analyzing the real, the ideal would be an irrelevant and unmeaning thing. We know what the ideal is because we observe what pleases us in the reality. If we allow the general notion to tyrannize at all over the particular impression and to blind us to new and unclassified beauties which the latter may contain, we are simply substituting words for feelings, and making a verbal classification pass for an æsthetic judgment. Then the sense of beauty is gone to seed. Ideals have their uses, but their authority is wholly representative. They stand for specific satisfactions, or else they stand for nothing at all.

In fact, the whole machinery of our intelligence, our general ideas and laws, fixed and external objects, principles, persons, and gods, are so many symbolic, algebraic expressions. They stand for experience; experience which we are incapable of retaining and surveying in its multitudinous immediacy. We should flounder hopelessly, like the animals, did we not keep ourselves afloat and direct our course by these intellectual devices. Theory helps us to bear our ignorance of fact.

The same thing happens, in a way, in other fields. Our armies are devices necessitated by our weakness; our property an encumbrance required by our need. If our situation were not precarious, these great engines of death and life would not be invented. And our intelligence is such another weapon against fate. We need not lament the fact, since, after all, to build these various structures is, up to a certain point, the natural function of human nature. The trouble is not that the products are always subjective, but that they are sometimes unfit and torment the spirit which they exercise. The pathetic part of our situation appears only when we so attach ourselves to those necessary but imperfect fictions, as to reject the facts from which they spring and of which they seek to be prophetic. We are then guilty of that substitution of means for ends, which is called idolatry in religion, absurdity in logic, and folly in morals. In aesthetics the thing has no name, but is nevertheless very common; for it is found whenever we speak of what ought to please, rather than of what actually pleases.

These principles lead to an intelligible answer to a question which is not uninteresting in itself and crucial in a system of aesthetics. Are all things beautiful? Are all types equally beautiful when we abstract from our practical prejudices? If the reader has given his assent to the foregoing propositions, he will easily see that, in one sense, we must declare that no object is essentially ugly. If impressions are painful, they are objectified with difficulty; the perception of a thing is therefore, under normal circumstances, when the senses are not fatigued, rather agreeable than disagreeable. And when the frequent perception of a class of objects has given rise to an apperceptive norm, and we have an ideal of the species, the recognition and exemplification of that norm will give pleasure, in proportion to the degree of interest and accuracy with which we have made our observations. The naturalist accordingly sees beauties to which the academic artist is blind, and each new environment must open to us, if we allow it to educate our perception, a new wealth of beautiful forms.

But we are not for this reason obliged to assert that all gradations of beauty and dignity are a matter of personal and accidental bias. The mystics who declare that to God there is no distinction in the value of things, and that only our human prejudice makes us prefer a rose to an oyster, or a lion to a monkey, have, of course, a reason for what they say. If we could strip ourselves of our human nature, we should undoubtedly find ourselves incapable of making these distinctions, as well as of thinking, perceiving, or willing in any way which is now possible to us. But how things would appear to us if we were not human is, to a man, a question of no importance. Even the mystic to whom the definite constitution of his own mind is so hateful, can only paralyze without transcending his faculties. A passionate negation, the motive of which, although morbid, is in spite of itself perfectly human, absorbs all his energies, and his ultimate triumph is to attain the absoluteness of indifference.

What is true of mysticism in general, is true also of its manifestation in aesthetics. If we could so transform our taste as to find beauty everywhere, because, perhaps, the ultimate nature of things is as truly exemplified in one thing as in another, we should, in fact, have abolished taste altogether. For the ascending series of æsthetic satisfactions we should have substituted a monotonous judgment of identity. If things are beautiful not by virtue of their differences but by virtue of an identical something which they equally contain, then there could be no discrimination in beauty. Like substance, beauty would be everywhere one and the same, and any tendency to prefer one thing to another would be a proof of finitude and illusion. When we try to make our judgments absolute, what we do is to surrender our natural standards and categories, and slip into another genus, until we lose ourselves in the satisfying vagueness of mere being.

Relativity to our partial nature is therefore essential to all our definite thoughts, judgments, and feelings. And when once the human bias is admitted as a legitimate, because for us a necessary, basis of preference, the whole wealth of nature is at once organized by that standard into a hierarchy of values. Everything is beautiful because everything is capable in some degree of interesting and charming our attention; but things differ immensely in this capacity to please us in the contemplation of them, and therefore they differ immensely in beauty. Could our nature be fixed and determined once for all in every particular, the scale of aesthetic values would become certain. We should not dispute about tastes, no longer because a common principle of preference could not be discovered, but rather because any disagreement would then be impossible.

As a matter of fact, however, human nature is a vague abstraction; that which is common to all men is the least part of their natural endowment. Æsthetic capacity is accordingly very unevenly distributed; and the world of beauty is much vaster and more complex to one man than to another. So long, indeed, as the distinction is merely one of development, so that we recognize in the greatest connoisseur only the refinement of the judgments of the rudest peasant, our aesthetic principle has not changed; we might say that, in so far, we had a common standard more or less widely applied. We might say so, because that standard would be an implication of a common nature more or less fully developed.

But men do not differ only in the degree of their susceptibility, they differ also in its direction. Human nature branches into opposed and incompatible characters. And taste follows this bifurcation. We cannot, except whimsically, say that a taste for music is higher or lower than a taste for sculpture. A man might be a musician and a sculptor by turns; that would only involve a perfectly conceivable enlargement in human genius. But the union thus effected would be an accumulation of gifts in the observer, not a combination of beauties in the object. The excellence of sculpture and that of music would remain entirely independent and heterogeneous. Such divergences are like those of the outer senses to which these arts appeal. Sound and colour have analogies only in their lowest depth, as vibrations and excitement; as they grow specific and objective, they diverge; and although the same consciousness perceives them, it perceives them as unrelated and uncombinable objects.

The ideal enlargement of human capacity, therefore, has no tendency to constitute a single standard of beauty. These standards remain the expression of diverse habits of sense and imagination. The man who combines the greatest range with the greatest endowment in each particular, will, of course, be the critic most generally respected. He will express the feelings of the greater number of men. The advantage of scope in criticism lies not in the improvement of our sense in each particular field; here the artist will detect the amateur’s shortcomings. But no man is a specialist with his whole soul. Some latent capacity he has for other perceptions; and it is for the awakening of these, and their marshalling before him, that the student of each kind of beauty turns to the lover of them all.

The temptation, therefore, to say that all things are really equally beautiful arises from an imperfect analysis, by which the operations of the æsthetic consciousness are only partially disinte-grated. The dependence of the degrees of beauty upon our nature is perceived, while the dependence of its essence upon our nature is still ignored. All things are not equally beautiful because the subjective bias that discriminates between them is the cause of their being beautiful at all. The principle of personal preference is the same as that of human taste; real and objective beauty, in contrast to a vagary of individuals, means only an affinity to a more prevalent and lasting susceptibility, a response to a more general and fundamental demand. And the keener discrimination, by which the distance between beautiful and ugly things is increased, far from being a loss of æsthetic insight, is a development of that faculty by the exercise of which beauty comes into the world.

It is the free exercise of the activity of apperception that gives so peculiar an interest to indeterminate objects, to the vague, the incoherent, the suggestive, the variously interpretable. The more this effect is appealed to, the greater wealth of thought is presumed in the observer, and the less mastery is displayed by the artist. A poor and literal mind cannot enjoy the opportunity for reverie and construction given by the stimulus of indeterminate objects; it lacks the requisite resources. It is nonplussed and annoyed, and turns away to simpler and more transparent things with a feeling of helplessness often turning into contempt. And, on the other hand, the artist who is not artist enough, who has too many irrepressible talents and too little technical skill, is sure to float in the region of the indeterminate. He sketches and never paints; he hints and never expresses; he stimulates and never informs. This is the method of the individuals and of the nations that have more genius than art.

The consciousness that accompanies this characteristic is the sense of profundity, of mighty significance. And this feeling is not necessarily an illusion. The nature of our materials—be they words, colours, or plastic matter—imposes a limit and bias upon our expression. The reality of experience can never be quite rendered through these media. The greatest mastery of technique will therefore come short of perfect adequacy and exhaustiveness; there must always remain a penumbra and fringe of suggestion if the most explicit representation is to communicate a truth. When there is real profundity,—when the living core of things is most firmly grasped,—there will accordingly be a felt inadequacy of expression, and an appeal to the observer to piece out our imperfections with his thoughts. But this should come only after the resources of a patient and well-learned art have been exhausted; else what is felt as depth is really confusion and incompetence. The simplest thing becomes unutterable, if we have forgotten how to speak. And a habitual indulgence in the inarticulate is a sure sign of the philosopher who has not learned to think, the poet who has not learned to write, the painter who has not learned to paint, and the impression that has not learned to express itself—all of which are compatible with an immensity of genius in the inexpressible soul.

Our age is given to this sort of self-indulgence, and on both the grounds mentioned. Our public, without being really trained,—for we appeal to too large a public to require training in it,—is well informed and eagerly responsive to everything; it is ready to work pretty hard, and do its share towards its own profit and entertainment. It becomes a point of pride with it to understand and appreciate everything. And our art, in its turn, does not overlook this opportunity. It becomes disorganized, sporadic, whimsical, and experimental. The crudity we are too distracted to refine, we accept as originality, and the vagueness we are too pretentious to make accurate, we pass off as sublimity. This is the secret of making great works on novel principles, and of writing hard books easily.

An extraordinary taste for landscape compensates us for this ignorance of what is best and most finished in the arts. The natural landscape is an indeterminate object; it almost always contains enough diversity to allow the eye a great liberty in selecting, emphasizing, and grouping its elements, and it is furthermore rich in suggestion and in vague emotional stimulus. A landscape to be seen has to be composed, and to be loved has to be moralized. That is the reason why rude or vulgar people are indifferent to their natural surroundings. It does not occur to them that the work-a-day world is capable of æsthetic contemplation. Only on holidays, when they add to themselves and their belongings some unusual ornament, do they stop to watch the effect. The far more beautiful daily aspects of their environment escape them altogether. When, however, we learn to apperceive; when we grow fond of tracing lines and developing vistas; when, above all, the subtler influences of places on our mental tone are transmuted into an expressiveness in those places, and they are furthermore poetized by our day-dreams, and turned by our instant fancy into so many hints of a fairyland of happy living and vague adventure,—then we feel that the landscape is beautiful. The forest, the fields, all wild or rural scenes, are then full of companionship and entertainment.

This is a beauty dependent on reverie, fancy, and objectified emotion. The promiscuous natural landscape cannot be enjoyed in any other way. It has no real unity, and therefore requires to have some form or other supplied by the fancy; which can be the more readily done, in that the possible forms are many, and the constant changes in the object offer varying suggestions to the eye. In fact, psychologically speaking, there is no such thing as a landscape; what we call such is an infinity of different scraps and glimpses given in succession. Even a painted landscape, although it tends to select and emphasize some parts of the field, is composed by adding together a multitude of views. When this painting is observed in its turn, it is surveyed as a real landscape would be, and apperceived partially and piecemeal; although, of course, it offers much less wealth of material than its living original, and is therefore vastly inferior.