Let us now substantiate, in the first part of this chapter, the differences in punishment between the two clusters of societies that were signposted in the Introduction. The second part of the chapter then introduces and develops the explanatory framework through which these differences can be understood.

In 2010, Finland had a rate of imprisonment of 60 per 100,000 of population, Norway 71 and Sweden 78. In contrast, the rate of imprisonment in New Zealand was 203 per 100,000 of population, in England 154, and in New South Wales 152 (in Australia as a whole it was 134): rates that, respectively, place them amongst the lowest and highest Western imprisoning societies.1 But can this measurement be used as a legitimate indicator of punitiveness? There are all kinds of methodological issues and concerns in the way in which imprisonment statistics are produced (are remands in custody included or excluded; are psychiatric institutions for the criminally insane counted or not counted; similarly, in relation to ‘young offender’ institutions, and so on) that would seem to raise prima facie doubts about such statistics’ reliability as a research instrument. It might also be thought that these doubts are then magnified when attempting to compare levels of imprisonment between different societies. However, notwithstanding these caveats, imprisonment rates do provide general pointers to penal trends, if not totally accurate counts of prison populations, and it is in this context that they have been used in this research. The consistent pattern of imprisonment, from the late nineteenth to the early twenty-first century, that they reveal within each cluster (leaving aside Finland) thus raises important analytical questions. For these purposes, as Cavadino and Dignan (2006: 5) note, imprisonment rates are ‘often the best [data] available … the one[s] most commonly and easily calculated and promulgated on a comparative basis’. At the same time, the validity of imprisonment rates as an indicator of penal difference is strengthened when a second indicator – prison conditions, in this case – seems to confirm their inferences.

While the two media reports that opened this book may, for obvious reasons, have had their own – and contrasting – measures of hyperbole, the differences in prison conditions between the two clusters were reaffirmed and extended in the fieldwork2 that was undertaken for this research. This involved visits to 40 prisons (some more than once). These ‘tours’ lasted between two and four hours, usually in the company of a senior officer. Features of the prison would be explained as it progressed and then, in most cases, there would be further discussions with the governor/manager. On some occasions, it was also possible to have discussions with other prison officers and prison personnel; on others, with prisoners, both individually and in groups. The prisons were selected to give a good cross-section: maximum and minimum security, men’s and women’s; closed and open, old and new. One of the reasons for conducting the research in this way was that it would be possible to observe recurring patterns relating to officer-inmate interaction, dining and visiting arrangements, and various other accoutrements of the material conditions of life that were common to the prisons and prison systems in each cluster.

The differences that then became apparent can be summarized in the following five ways:

• Prison size

• Officer/inmate relations

• Quality of prison life

• Prison officers

• Work and education programmes.

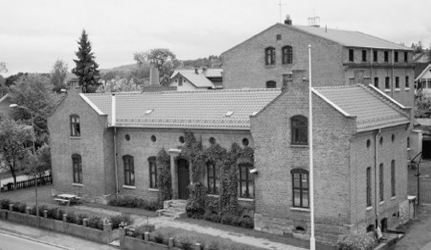

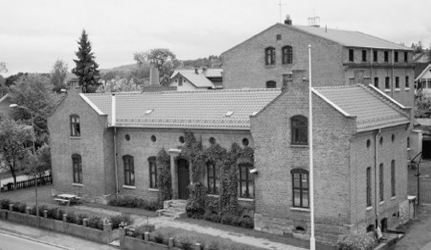

Nordic prisons tend to be much smaller than those in the Anglophone countries. It is quite common to find 50- or 60-bed establishments in this region (see Figure 1.1). The logistical consequences are that, despite their much smaller prison populations, the Nordic countries have many more prisons per head of population (see Table 1.1).

These differences in prison size obviously make housing prisoners near their families much more straightforward in the Nordic countries than in the Anglophone.

Table 1.1 Contrasts in prison size

| Country | Prison population | Number of penal institutions | Average prison size |

| England | 85147 | 140 | 608 |

| New South Wales | 11330 | 35 | 324 |

| New Zealand | 8706 | 19 | 458 |

| Finland | 3231 | 35 | 92 |

| Norway | 3446 | 47 | 73 |

| Sweden | 7286 | 84 | 87 |

Source: WorldPrison Brief (2010).

It is also clear that prison size is likely to affect staff/inmate relations: the larger the institution, the more likely it is that prison staff and inmates will become more anonymous to each other, mitigating against any sense of solidarity and cohesion or the development of trusting relationships. At the same time, the smaller Nordic institutions are likely to pose less of a threat to local property values and security, a frequent complaint whenever locations are sought for new penal institutions in the Anglophone prison world. Indeed, it seems to be the case that the much smaller Nordic penal institutions become valued community resources rather than objects of widespread antagonism and hostility.

Nonetheless, in recent years, the Anglophone countries have been building progressively larger prisons, both because of the increase in the numbers of people being sent to prison and also as a way of rationalizing and reducing prison costs. In England, this reached its apogee with the plans to build three ‘Titan’ prisons, holding 2,500 inmates each, in 2007.3 At the same time, private prisons now constitute some 10 per cent of the total prison stock in England (although there has been no recourse at all to this in the Nordic countries), and are usually justified on the basis that the private sector is not only better able to save money than the public sector but, in addition, the competition it provides is also likely to bring down the costs of public sector prisons.4

There seems to be more routine interaction and less social distance between officers and inmates in the Nordic prisons. Inmates and staff might share the same canteen at mealtimes in some institutions, as well as use first name terms when addressing each other. In Norway, officers knock on the cell door before entering, so that inmates are not disturbed without prior warning. And maximum security conditions can provide the opportunity for more, not less, interaction between officers and inmates. Thus, at Kumla prison in Sweden, the emphasis on security is rationalized as follows: ‘now we are working actively with the prisoners whereas previously we were only monitoring them. Prisoners and staff cook together and we are around when they study or work. We get to know them and how they feel, which also means we can notice early signs of conflict and actively prevent them from escalating by adding more staff or moving prisoners to a different room’ (Dagens Nyheter, 18 November 2009: 1). Obviously, something other than ‘friendship’ is being cultivated through such closeness, since these relations are also likely to enhance surveillance and security tasks. Nonetheless, the obligations on Swedish prison officers to undertake counseling and planning with the small groups of inmates for whom they have responsibility seem likely to further reduce social distance and bring about a relatively relaxed atmosphere (Bruhn, Nylander and Lindberg, 2010).

This is not to say, of course, that no such interaction takes place in the Anglophone prisons. While, in New South Wales, staff/inmate relations seemed the most formal, in New Zealand and England relationships were generally relaxed, with both groups on first name terms with each other (although, in New Zealand, there were also occasions when officers addressed inmates as ‘Prisoner X’, ‘Prisoner Y’, etc). In England, what is known as the ‘decency’ agenda has made a significant contribution in recent years to reducing what had previously been the extensive social distance between prisoners and prison staff in that country. Prisoners at Kirkham open prison told us that ‘the majority of staff genuinely want to help and want to interact with prisoners’. We were also told several times by staff during the English prison visits that they were ‘proud’ or ‘very proud’ of the work they did. However, the position is very different in maximum security areas. Unlike the Swedish example above, personal contact is kept to a minimum; in New Zealand, three officers accompany any movement of an individual prisoner, who must kneel, and face the wall away from them with hands behind his back when they enter the cell. In such prisons in New South Wales, officers are stationed in watchtowers and armed with rifles. There is also an Immediate Action Team that patrols the grounds of these institutions, carrying an array of armaments and dressed in highly militarized fatigues.

Furthermore, whatever the inclinations of the officers themselves in the Anglophone prisons, interaction with inmates is also likely to be greatly restricted by security and budgetary concerns. Broadly speaking, staff/inmate ratios are more favourable in the Nordic countries. For example, in Norway and Sweden there is 1 officer per each 0.8 prisoner; in New South Wales, the ratio is 1:2, and in New Zealand, 1:2.1. One consequence of this is that the great majority of prisoners – virtually all except those in open institutions, and still smaller numbers on ‘self-catering’ arrangements – in the Anglophone societies eat their meals in their cells, with obvious detrimental consequences in terms of socializing and learning how to live in the company of others without conflict. We were told of one New South Wales and one English prison where officers had tried to instigate weekly lunches but the inmates did not wish to participate. Clearly, with the greater social distances between the two groups that had been part of the institutional history of these establishments, sudden attempts to break this down by one side are likely to be met with caution and suspicion by the other. Again, respect for inmates from staff seems to be more of an institutional feature of Nordic prisons, rather than being dependent on individual officers’ discretion. Thus, in most Norwegian prisons, there are weekly meetings between representatives of prisoners and prison officers. There was much less of these arrangements in the Anglophone countries: only in England were these anything like routine.

The general ‘quality of prison life’ – diet, cleanliness, quietness, personal space and visiting arrangements – in both open and closed prisons seems much higher in the Nordic than in the Anglophone prisons. Overcrowding and lack of personal space is much more a feature of the latter. For example, in one New Zealand prison, an institution for ‘vulnerable prisoners’, the cell is 4 x 2 metres and two inmates have to share this. While there is some cell sharing in the Nordic prisons, particularly in low security facilities where doors are seldom locked and there are large communal areas to compensate, this is an exception to the more general pattern of unshared cells, common rooms and lounge facilities, as well as kitchen areas where inmates can routinely cook light meals. Some prison sections may be fully self catering, including maximum security units. Indeed, while their freedom of movement is much more restricted, maximum security prisoners still enjoy most of the privileges of other inmates. They thus have access to ‘conjugal visits’ (absolutely prohibited in these Anglophone prison systems), arranged and facilitated by the authorities, in apartments, ‘visit rooms’ or ‘guesthouses’ (as at Halden) within the prison grounds. These visits, in which inmates and their family can live together, making their own food, and so on, can last from a few hours to a whole weekend. Where there are no such facilities, as in one small open prison near Helsinki, we were told that inmates were simply allowed home at weekends for these purposes.

In contrast, in the Anglophone countries, what quality of life that there is in the prisons has been, or is in serious danger of being, further eroded by budget cuts and overcrowding. This is particularly gross in English local prisons. At the time of the visit to one such institution in the north-west region, there were 757 inmates when the normal accommodation level should have been 441. At the same time, while the practice of ‘slopping out’5 has now largely come to an end in the Anglophone prisons, it still persists in some. In 2010, there were two New Zealand prisons without in-cell sanitation, nor any means to allow prisoners to leave their cells for ablution purposes during the night. Even so, the provision of toilets in cells built for one person but frequently housing two is a mixed blessing. In England, as one senior civil servant explained to us, the reality of these sanitation arrangements in small cells, particularly when these are shared, is that ‘two people are living in a toilet’. The fact that this area may now be curtained, as was seen in a number of the English prisons that were visited, does little to remove the attendant indignities and lack of hygiene. But, again, security, lack of resources, and dilapidated prison buildings prevent prisoners from being able to simply exit their cells for these purposes, as the overwhelming majority of Nordic prisoners are able to do, and where such hygiene issues, and all the indignities raised by them, simply do not exist.

Furthermore, cells and wings in the Nordic prisons are more likely to have furnishings and accoutrements that are of a considerably higher standard than the Anglophone. In Helsinki prison, for example, there are glass tanks containing tropical fish in the library and on some of the wings. The prisoners feed them and clean the tanks. We saw something similar in one English closed prison (the fish tank had been provided by the officers) but we were also told in New Zealand and New South Wales that any such arrangements would be prohibited on the grounds of cost, security (‘What if the tanks were smashed and the glass used as a weapon?’) and fear of ‘public opinion’ if the news media ever got to hear of such ‘treats’. It was also explained that pool tables were prohibited in a low security New South Wales prison for these reasons. These were available in the English prisons but could only be used under the supervision of officers. And, while there are indeed the ‘open spaces’ to which the New Zealand Corrections Minister referred (p. 2), these tend to be prohibited areas in the Anglophone prisons, often outside caged walkways or enclosed concrete exercise yards. Even in new prisons, where lounges and common room areas have been factored into the design in these countries, lockdowns or the increasingly restricted association periods make these facilities largely irrelevant.

Prisoners in the Nordic countries, however, are likely to be out of their cells considerably longer than those in the Anglophone systems. In Norwegian closed prisons, lockdown lasts from 8.00 pm (for some higher security prisoners), or 9.00 pm to 7.00 am. In Finland, from 7.00 pm to 6.30 am in the closed prisons. In Sweden, the Corrections [Kriminalvården] website states that inmates ‘are woken at 7.00 am by a knocking on their door by an officer “to say good morning”, which is a small but important aspect of how one treats each [other]’. It goes on to add that lockdown is at 8.00 pm (10.00 pm in the open prisons), explaining that this ‘might sound harsh, but many inmates look forward to some peace and quiet.… [they] decide when they want to turn off their bedside lamp, and they can contact a staff member if they want to talk for a while in the evening’. In contrast, in New Zealand and New South Wales prisons, the general rule seems to be that there is, in effect, a 16 hour routine lockdown, except for those in lower security classifications. This lasts from 5.00 pm, when inmates take their ‘dinner’, and breakfast packs for the following morning, to their cells, to 8.00 am when unlocking occurs. There is a further lockdown hour at lunchtime, when this meal is also routinely eaten in the cells. And, while closed prisons in England (except those which are high security) are closer to the Nordic standards – with a 7.30 pm to 8.00 am lockdown – we were regularly told that this was in severe danger as a result of budget cuts. Indeed, in that country, the core working week ends at midday Friday. Prisoners are then, for all intents and purposes, locked down until the following Monday morning. In the closed male prisons in these countries, dining in association barely exists, yet this is de rigeur in the Nordic prisons.

| Figure 1.2 | Laukaa open prison, Finland. Photo supplied by Criminal Sanctions Agency, Finland. |

| Figure 1.3 | Åby open prison, Sweden. Photo: Aren Gharibashvily, Swedish Prison and Probation Service. |

Furthermore, a much higher proportion of Nordic prisoners (around 30 per cent) spend their time in open prisons. Here, fences, walls and other barriers are reduced to a minimal level. Sometimes there are none at all (see Figures 1.2 and 1.3).

In some, prisoners are able to lock and unlock their own cell doors. After the prisoners finish work or classes, they are free to walk around the prison grounds and sometimes into the neighbouring communities. As such, many open prisons in this region are more similar to Anglophone ‘halfway houses’, whereby inmates have regular employment outside the institution, and take part in everyday life outside it, as well. Although English open prisons operate in a broadly similar manner, there are only 10 such institutions, housing about six per cent of the total prison population in this country. There are a small number of similar institutions in New South Wales (also known as afforestation camps), while New Zealand has no genuinely open prisons. Although there are small numbers of inmates who live in low security self-care units, these remain within the prison complex, with razor wire and security camera surrounds. At the same time, food servings – one of the most important features of prison life, for inmates – generally seem more varied and generous in the Nordic prisons. The standard Finnish and New Zealand prison menus for 2009, set out in Tables 1.2 and 1.3, provide striking contrasts.

The menu for Finland (the inmates prepare their own food on weekends) seems much less ‘institutionalized’, not to say substantial, than that for New Zealand. In addition, there are no restrictions6 placed on ‘incidentals’ (jam, bread, sauce, etc.). However, the strict measurements of these in the New Zealand menu – ‘toast x 2’ for breakfast, ‘ 15 g of margarine, 35 g of sugar’ – are standard practice across the Anglophone prisons. It also contains the supplementary information that ‘two slices of bread and 15 g of margarine are supplied with the evening meal when the lockdown period between dinner and breakfast is greater than 14 hours’.

One of the most dramatic features of Anglophone prisons is the reception area for remands or those just sentenced. Here, often in the most squalid, overcrowded and intimidating surrounds, a transformation of the self is expected to take place as the world beyond the prison is shut out and each new reception assumes his or her prisoner identity. They usually arrive en masse from the courts, having been chained and shackled in the escort van during the journey. They are then placed in holding cells with groups of others during processing (sometimes lasting for hours). Of these three countries, only in England, it appeared to us, had steps been taken to alleviate this ordeal (as it surely must be, at least for those who have never been in prison before). At Preston, we were told that a night officer introduces himself and gives reassurances to first nighters. Elsewhere, information booklets are given to new receptions. In contrast, the entry to Nordic prisons is likely to be much less dramatic, easing and lessening the transition from free citizen to prisoner. Those sentenced to short prison sentences in Norway and Sweden (although not those on remand, or those sentenced to a prison term for violent or organized crime) are able to avoid such introductions altogether. Instead, they may be given a time within a six-month period when their sentence will start, if they make an application for deferment for various personal reasons. Prospective inmates then make their own way to prison on the appointed day. Ilseng prison in Norway provides instructions for them on its website,7 giving details of train and bus services. It then adds that ‘the [inmates] may choose whether to use private clothes or borrow clothes from the prison. All inmates will be given the necessary toiletries as needed.’ On the day of arrival, the inmate attends a kind of induction class (standard practice in all Norwegian prisons), rather than being left to make sense of their new surrounds as best they can themselves: ‘on that evening there is an information meeting for all the [new] inmates that day and a thorough briefing about the prison is given’.

Table 1.2 Prison menu: Finland (2009)

| Breakfast | Lunch | Dinner | |

| Mon | Oatmeal Porridge | Meat Stew with Dill | Salmon and Vegetable |

| Bread | Potatoes | Soup | |

| Margarine | Salad Side Dish | Pie | |

| Milk | |||

| Tue | Barley Gruel, | Liver-Vegetable | Sausage and Macaroni |

| Bread | Steak | Casserole | |

| Margarine | Onion Gravy | Salad Side Dish | |

| Cheese | Potatoes | ||

| Tea | Mashed Lingonberries | ||

| Sugar | Salad Side Dish | ||

| Wed | Yoghurt | Minced Meat and | Mushroom and |

| Bread | Vegetable Soup, | Vegetable Casserole, | |

| Margarine | Gourmet Porridge/ | Salad Side Dish | |

| Cheese Spread | Date Porridge | ||

| Thu | Rye Porridge | Tuna Stew | Sailors Steak |

| Milk | Spaghetti | Salad Side Dish | |

| Bread | Salad Side Dish | ||

| Margarine | |||

| Cheese Spread | |||

| Fri | Wheat Porridge | Chicken Sauce | House Meal |

| Milk | Rice | ||

| Bread | Salad Side Dish | ||

| Margarine | |||

| Eggs | |||

| Pie | |||

| Sat | Rice Porridge | Pepper Meatloaf | |

| Bread | Potatoes | ||

| Margarine | Gravy | ||

| Vegetable | Salad Side Dish | ||

| Tea | Plum Fool | ||

| Sugar | |||

| Sun | Semolina Pudding | French Meat Stew | |

| Bread | Potatoes | ||

| Margarine | Salad Side Dish | ||

| Milk | Lingonberry Sour Milk | ||

| Fruit | (this is similar to a | ||

| Cold Cuts | smoothie) | ||

| Pastry | |||

| Coffee/Tea | |||

| Sugar |

Table 1.3 Prison menu: New Zealand (2009)

| Breakfast | Lunch | Dinner | |

| Mon | Weetbix (x2) | Filled Roll (x2) | Braised Sausage |

| Milk (300ml) | 2 x ham, tomato | Brown Onion Gravy | |

| Toast (x3) | and coleslaw | Potatoes, Vegetables (x2) | |

| Margarine (15g) | Fruit (1 piece) | Bread (2 slices), | |

| Spread (20g) | Tea | Marg(15g) | |

| Bran(1 dstsp) | Fruit (1 piece) | ||

| Tea, Sugar (35g) | Tea, Milk (300ml) | ||

| Tue | Ricies (x30g) | Sandwich (x3) | Spaghetti Bolognaise |

| Milk (300ml) | 1 x cheese and onion | Spaghetti Noodles | |

| Toast (x3) | 1 x ham and sauce | Vegetables (x2) | |

| Margarine (15g) | 1 x fruit spread | Bread (2 slices), | |

| Spread (20g) | Fruit (1 piece) | Margarine (15g) | |

| Bran(1 dstsp) | Tea | Fruit (1 piece) | |

| Tea, Sugar (35g) | Tea | ||

| Wed | Weetbix (x2) | Filled Roll (x2) | Roast Chicken, Gravy |

| Milk (300ml) | 2 x egg, lettuce and | Potatoes, Vegetables (x2) | |

| Toast (x3) | mayonnaise | Bread (2 slices), | |

| Marg(15g) | Fruit (1 piece) | Margarine (15g) | |

| Spread (20g) | Tea | Fruit (1 piece) | |

| Bran(1 dstsp) | Tea, Milk (300ml) | ||

| Tea, Sugar (35g) | |||

| Thu | Ricies (x30g) | Sandwich (x3) | Mince and Cheese Pie |

| Milk (300ml) | 1 x creamed corn | Tomato Sauce | |

| Toast (x3) | 1 x coleslaw and | Potatoes, Vegetables (x2) | |

| Margarine (15g) | beetroot | Bread (2 slices), | |

| Spread (20g) | 1 x egg and mayonnaise | Margarine (15g) | |

| Bran(1 dstsp) | Fruit (1 piece) | Fruit (1 piece) | |

| Tea, Sugar (35g) | Tea | Tea | |

| Fri | Weetbix (x2) | Filled Roll (x2) | Fish (various preparations) |

| Milk (300ml) | 1 x luncheon, tomato, | Tomato Sauce | |

| Toast (x3) | lettuce and mayonnaise | Potatoes, Vegetables (x2) | |

| Margarine (15g) | 1 x cheese and onion | Bread (2 slices), | |

| Spread (20g) | Fruit (1 piece) | Margarine (15g) | |

| Bran(1 dstsp) | Tea | Fruit (1 piece) | |

| Tea, Sugar (35g) | Tea, Milk (300ml) | ||

| Sat | Ricies (x30g) | Sandwich (x3) | Roast Beef, Gravy |

| Milk (300ml) | 2 x cheese and pineapple | Potatoes, Vegetables (x2) | |

| Toast (x3) | 1 x peanut butter | Bread (2 slices), | |

| Margarine (15g) | Fruit (1 piece) | Margarine (15g) | |

| Spread (20g) | Tea | Fruit (1 piece) | |

| Bran(1 dstsp) | Tea | ||

| Tea, Sugar (35g) | |||

| Sun | Weetbix (x2) | Filled Roll (x2) | Beef & Vegetable Curry, |

| Milk (300ml) | 2 x luncheon, coleslaw | Rice, Vegetables (x2) | |

| Toast (x3) | cheese & beetroot | Bread (2 slices), | |

| Marg(15g) | Fruit (1 piece) | Marg(15g) | |

| Spread (20g) | Tea | Fruit (1 piece) | |

| Bran(1 dstsp) | Tea | ||

| Tea, Sugar (35g) |

There are significant differences in prison officer culture, recruitment and training. There is much less evidence, for example, of the military origins and traditions of the prison service in the Nordic countries, compared to the Anglophone. In Finland, especially, there are virtually no markings on the officers’ uniforms. Indeed, there is evidence of very different expectations of the work and role of prison officers in these societies. This is implicit in the Swedish term for ‘prison officer’, fångvårdare, for which the literal translation is ‘prisoner carer’. In Norway, the equivalent term, fengselbetjent, means, literally, ‘prison servant’. Of course, it could be argued that these mellifluous expressions merely camouflage more sinister intents and purposes. But this then begs the question of why the Swedes and Norwegians should be so sensitive about terminology that is taken for granted in the Anglophone world. Furthermore, the absence of parades, marching, and so on is another clear break from any military ancestry and traditions that, to a degree, are still kept alive in the Anglophone prisons, New South Wales especially. Here, there are likely to be officers’ parades at the start of each morning shift in some of the closed prisons. At the same time, it is obvious that the uniform and insignia still carry great emotional and symbolic importance for large sections of the officer body (although a significant minority now work in polo shirts and ‘chinos’ in New South Wales). More generally, what was also noticeable was the way in which officers in the Anglophone countries would refer to each other as ‘Mr’, ‘Ma’am’ or ‘Miss’ while on duty, as if this formality helped to preserve some sense of hierarchy and structure that public sector reforms and the introduction of flatline career structures have largely stripped away.8 In contrast, Nordic prison officers all seemed to be on first name terms with one another, whatever their respective levels in the prison service.

These differences in culture are likely to be related to the training the officers receive, as well as the structure of their working environment. In New Zealand, basic training of new recruits takes six weeks, the same as in New South Wales private prisons. Training in the public prisons in New South Wales lasts for 11 weeks. In England, basic training is for eight weeks. In Sweden the training lasts 40 weeks. In Finland, it lasts for one year and in Norway two years. In New South Wales, we were told that the training is a mixture of ‘security, case management and special needs’. This includes ‘weapons training – some prison officers carry guns. There is also exposure to gas and riots. There is a strong emphasis on ethics, accountability and practical qualifications. We are very supportive of teamwork and training in the culture we want them to have, although this changes depending on which centre they work in. There are strong guidelines around the use of force and video surveillance of incidents.’ Similarly, Arnold (2005:399) writes of prison officer training in England: ‘the security aspects of the work are emphasized over and above all else as a critical occupational norm. The need to maintain physical and dynamic security (through relationships) appeared to be intrinsically tied to (and led to) the increase in suspicion, mistrust, vigilance and an overriding concern for their own and others’ safety.’ Overall, the impression gained during the course of the visits to the Anglophone prisons was of a high regard for practical skills that officers were expected to possess, and the inculcation of an ethos that would foster group cohesion among the officer body. Life skills, it appeared, were more important than educational qualifications. Although, in England, five passes in secondary school fifth-form exams had been part of the eligibility criteria for joining the service, this has been abandoned. There is no stipulation for academic credentials in New South Wales and New Zealand.

In contrast, in Finland, eight per cent of prison officer recruits in 2008 had a university degree; in Sweden, one third of prisoner officer recruits have completed two years of tertiary education; and in Norway the prison service is increasingly becoming a graduate profession. The minimum criteria for entry to the prison service in the latter includes passing the school leaving exam in three subjects (Norwegian, English and Social Studies) and one year’s experience of ‘working with people’, for example, in hospitals, kindergartens or prisons. Here, then, working in prison was seen as much the same as working in any other institution: the prison was not set apart from the rest of society, requiring an altogether different mindset for working there. Indeed, we were told that 30 or 40 per cent of new recruits in Norway are likely to have had experience of working in prison when they apply to join the service. Many law and behavioural science students, for example, work part-time or in vacations as temporary prison officers, an indicator, surely, of the relative lack of stigma associated with such work in this country. In the 2009 intake to the Norwegian prison officer training college, there were 1,680 applicants for 150 places: and this in a country where the rate of unemployment was only two per cent. In other words, there were likely to have been plenty of other career choices for these applicants, yet they chose the prison service. In the Anglophone countries, however, it is only likely to be when unemployment is high that there will be much interest in this occupation. At such times, we were told, ‘it’s working in Tesco’s [a supermarket chain] or working in prisons’. Thus, in New Zealand, a major expansion of the prison estate after 2000 in a healthy economic climate was met by serious recruitment problems, leading to attempts to recruit from the Pacific Islands, South Africa, England and continental Europe (at considerable expense and with limited success).

In contrast to the Anglophone training objectives, we were told that the main goal of Norwegian training is ‘to educate people with high moral standards. Ethics and professionalism are important subjects. We want reflexive individuals who think for themselves, their role in society and then on other people. They don’t have to know about prisons but they have to be able to reflect on themselves. They study law, criminology, sociology and psychology. Then as their last subject, the officer role. They need to believe that people can change … a good prison officer is someone who sees the inmates where they are. They should be able to help prisoners help themselves, but they have to wait and be patient for changes.’ There is also, of course, an emphasis on physical security in the training, but what is evident in the above comments is the importance given to the capacity of the individual officer to work productively with inmates: their role in the officer group gets nothing like as much attention as in the Anglophone countries. Furthermore, the different gender mixes in the prison staff of the clusters also seem likely to contribute to their differing working cultures and emphases in prison officer training. Broadly speaking, the male/female officer distribution in the Nordic countries is 2:1, while in the Anglophone countries it is 3:1.

Inmates in Nordic prisons are more likely to be occupied in work or education than in the Anglophone countries, notwithstanding recent investments and enrolment increases in these facilities in the latter. It is a goal, in the Nordic prisons, that each inmate should be active during the day in either work or education (failure to be so leads to small reductions in their daily allowance). One striking difference in this aspect of prison life is that education is not seen as a remedial extra, as it has been during the history of the Anglophone prison systems – something that illiterates could, in the main, turn their minds to at the end of the working day, even if there was no work for them during the day itself. Instead, it can be an alternative to work. Indeed, one third of the Nordic prison population is involved in educational studies, where tuition is offered up to and including tertiary level. Given, as well, that illiteracy is virtually non-existent in these countries, then the general standard of education delivery is considerably higher than the remedial level that still seems to be the main focus of educational services in the Anglophone prisons; hardly surprising, given that around 50 per cent of their inmates are functionally illiterate. Certainly, there are opportunities for prisoners to study at tertiary level in these countries as well (in their ‘free time’, we were told) and small numbers are able to make use of these opportunities, but lack of internet access must make this immeasurably more difficult and frustrating than in the outside world. At the same time, the Nordic prison libraries seemed particularly well stocked and equipped, with numerous foreign language volumes to accommodate their non-nationals, something to which the Anglophone prison systems seem barely to have given any thought at all.

As regards payment for work, the overwhelming majority of prisoners in the Anglophone societies earn only a few pounds or dollars per week. The exceptions are the small number of inmates allowed out of prison to work. In New Zealand and New South Wales, combined, there were around 300 such prisoners in 2010. They are paid something like the national minimum wage, for which deductions for ‘rent’, board and so on are made. Only in the small number of English open prisons does it appear that there is any systematic attempt to have prisoners working beyond the prison itself. But then, given the realities of the job market, and the underskilled and undereducated backgrounds of most prisoners, it was not surprising to hear that ‘lots of these [prisoners] were working in charity shops’, again being paid nothing more than the minimum wage. While they were, at least, out of prison during the day, there was no sense of any kind of career structure being developed for them. In Finland, however, those working in open prisons are paid ‘real wages’ for their labour, out of which they pay taxes and ‘rent’, give money to their family and to their victims, and save for their release. In other words, they are being given the opportunity to participate in the standards and expectation of ‘normal life’, rather than allow their time to be ordered by the separate standards and values of the prison. Indeed, some Swedish inmates were allowed to continue in the employment they had before their prison sentence. At Asptuna open prison near Stockholm, there is a car park for inmates (as there also is at Kirkham open prison in England, it needs to be acknowledged), since some of them commute to work in the city. If they are going to return late, they telephone ahead, and a meal is left out for them on their return. More generally, the allowances for prisoners in closed institutions in the Nordic countries are likely to be several times higher than in the Anglophone, with incidental extras: televisions that are provided free, for example, rather than rented or provided by families, as in the latter.

We also found that work opportunities were increasingly difficult to come by, both for security and economic reasons in the Anglophone countries. In New Zealand, for example, since the mid-1990s, the rule has been that all prison labour must make a profit in order to be justifiable. This brought an end to the cottage industry handicrafts that had previously occupied many inmates during the day, as they made toys, furniture and so on for hospitals and children’s homes. The reality in 2010, particularly for those serving short sentences or in low risk categories, was that they were left almost completely to their own devices. In addition, overcrowding pressures inevitably mean that what programmes and work activities there are may be interrupted, as inmates are moved from one institution to another, in the unending task of managing bedspace.

Of course, we have provided very general pictures here, and in each cluster we acknowledge that we are likely to find exceptions to them. As regards the Nordic prisons, we thus need to be aware that, notwithstanding the vastly superior material conditions of confinement in the institutions, bullying and intimidation still occur. One in eight inmates at Helsinki prison requested to be placed in isolation at some stage of their sentence (Annual Report of the Finnish Prison and Probation Services, 2004). There is an inmate culture in the Nordic prisons, just as there is in the Anglophone countries. Indeed, some of the distinguishing features of these prisons have been turned into local currency by the inmates: the family visits entitlement is something that can be traded or fought over, like cigarettes and phone cards. In Norway, the physical comforts in one open prison for women are remarkable, but this will not ease the distress of those who are mothers of infants. Norwegian prison rules do not allow women sentenced to prison to be accompanied by babies or minors. In addition, conditions for remand prisoners (around one quarter of the prison populations of Norway and Sweden) are considerably more restrictive. Some remandees may even be held in solitary confinement until the time of their trial (for years, in extreme cases). Both Norway and Sweden have been criticized by the European Committee against Torture and Inhumane Treatment for these practices. In Sweden, security has been significantly tightened across all closed prisons in the aftermath of sensational escapes in 2004: the escapees were repeat violent offenders who murdered two police officers during the course of these incidents; guns had also been smuggled into the prison beforehand, with the involvement of organized crime groups, and helicopters were used to facilitate the getaways. In their aftermath, no-fly zones have been in force in the airspace above the maximum institutions in this country, and it now seems that specialist security staff in the prisons are gaining higher status than those performing the traditional ‘personal officer’ role (Lindberg, Nylander and Bruhn, 2011). At the same time, the new Swedish prison officer uniform – dark blue with crowns on the shoulders – seems designed to reaffirm both the authority and trustworthiness of these officers, after the 2004 escapes.

As regards the Anglophone countries, we need to recognize that, in New Zealand, cultural awareness and sensitivity seems particularly high, and also features strongly in the training of new prison officer recruits. There is also an emphasis on programmes based on Maori culture and ceremony, for Maori inmates who now make up half of that country ’s prison population (although there is far less emphasis, it seems, in providing them with more mundane opportunities to simply live harmoniously with others). In New South Wales, one is particularly struck by the high level of resourcing for mental health and addiction problems. The Compulsory Drug Treatment Correctional Centre at Parklea was described to us as being ‘more like a forensic hospital than a prison. Drugs are treated as a health rather than a crime issue.’ In this institution, ‘prisoners can be taken out shopping. Lock up is at 7.00 pm or 9.00 pm and they eat in a dining room.’ In New Zealand, the Kia Marmara sex offender unit, at a prison near Christchurch, has won international acclaim for its highly successful rehabilitative programmes, and is run very much along the lines of a therapeutic community. Other points to note in the Anglophone countries include the provision of high calibre mother and baby units; special projects that include ‘Pups in Prison’ (that is, the training and domesticating of guide dogs for the blind); fathers in prison making DVDs of themselves reading books for their children; foreign nationals using DVD messaging to keep in contact with their families; the Wild Life Protection Centre in New South Wales, which employs 12 inmates; and a prisoners’ art exhibition in Auckland in 2010. We were also struck by attempts in England and New South Wales (although not New Zealand) to humanize visiting arrangements, within the prevailing security conditions, by providing play areas for children and a cafe, or at least facilities for food and drinks, in the vicinity.

Such developments point to significant attempts by the Anglophone prison authorities to move forward from their histories of squalor, riots, repression, violence from both sides, intimidation and the strikes by prison officers that featured from the 1970s to the 1990s (see, for example, Carrabine, 2004; Sim, 2009). Public sector restructuring in England and New Zealand, and more generous resourcing in New South Wales, has given momentum to this, as has the injection of private prisons (in conjunction with a series of critical official reports, including those from the independent Inspectorate of Prisons, in England, and from the Human Rights Commission and Office of the Ombudsman, in New Zealand). However, it was apparent that, in New South Wales, where there has been much less public sector restructuring, long running tensions and conflicts between state government and prison management, on the one hand, and the prison officers’ union, on the other, remain. Both sides are antagonistic towards, and suspicious of, each other. We are still likely to find significant remnants of a militaristic, repressive, prison officer culture. Prison management regularly complain of, and investigate, overtime and sick leave abuse by the officers; meanwhile, officers are suspicious of management’s plans for privatization, and complain of cost-saving understaffing.

More generally, institutional arrangements that are the exception, rather than the rule, should not obscure the major structural differences in the respective organization and administration of penal institutions between the two clusters. Essentially, in the Nordic countries, even in the high security units and institutions, prisoners do not become degraded non-citizens with their rights stripped away from them: instead, they retain all their citizens’ rights, including the right to vote in elections, education, health services, drug treatment, the rights to work and enjoy holiday entitlements, and so on. This means, for example, that, in Norway and Sweden, education and healthcare services are provided through the respective government departments, rather than Corrections or Justice. As we have seen, while they remain prisoners, they are less likely to be excluded from the rest of society, and shut out of any involvement with it, than in the Anglophone countries. One particularly clear illustration of this occurred in Norway, in the run up to the 2009 general election. A law and order debate was televised from a prison, with the panel featuring the Justice Minister, his Opposition counterpart, and a maximum security prisoner. The debate was reported in The Guardian (10 September 2009: 11), as follows: ‘In Norway, Prisoners Take Part in TV Debates’. The article continued, ‘The primetime show, one of the top debate shows during the election campaign, has caused no outrage in Norway, as it probably would in the UK. There were no headlines expressing shock that inmates could voice their opinions in public debate. Nor was there condemnation of NRK, the Norwegian public broadcaster, for hosting a political debate inside a prison.’ Overall, the Nordic prison authorities are committed to the normalization of prison life – making conditions within the prisons compatible with those of the outside world, as far as this is possible. The Norwegian Ministry of Justice and Police White Paper (2008), Punishment that Works, reaffirms that ‘the normality principle is one of the five pillars on which the activity of Norwegian criminal care works’. In Finland, prisoners’ rights are guaranteed in the constitution, under the provisions of the 2002 Prisons Act. The values and goals of the Finnish prison service remain offender-oriented, rather than replete with references to public safety and victims’ rights, and include ‘safeguarding basic rights and human rights’ (Annual Report of the Finnish Prison and Probation Services, 2004: 5).

In the Anglophone jurisdictions, there is a great deal of emphasis on key performance indicators [KPIs] in the annual prison reports. But there is little regard, in these charts and scores, for the effects of the lockdowns, enforced cell sharing, disruptions caused by prisoner transfers, difficulties in visiting arrangements and so on, that are more clear markers of the realities of prison life in these countries. No amount of KPIs can alter the fact that the 16 hour routine lockdown in many of the Anglophone prisons is going to significantly undermine whatever quality of life there is in these institutions. The Nordic prison systems also have their KPIs, but these do not seem to have been allowed to subvert the ethics and morals of prison life in these countries. The purpose of imprisonment, we were told by one Norwegian prison manager, is ‘to train offenders how to be ordinary citizens’. Again, in these countries, one is struck by the high levels of trust that seem to exist between prison staff and inmates, and the high levels of self-regulation and norm enforcement: without such attributes, it would simply be impossible for prisons in this region to function as they do. In the Anglophone prisons, however, security has come to assume overwhelming priority (as it is also becoming in the Swedish closed prisons, it must be recognized). Inevitably, in such a risk-averse climate, trust is either undermined or harder to establish. The remarks made to us by a senior officer in a low security establishment in New South Wales exemplify this: ‘Don’t ever trust a prisoner. Don’t ever get close to them.’

At the same time, there not only seem to be much stronger divisions between prisoners and the rest of society in the Anglophone countries, but these also seem to be widening. This is hardly the fault of the prison services in these jurisdictions. Rather, it is a reflection of the level of the (more general) public and political debates about punishment and prisons, in these countries, that then circumscribe prison policy. Even when prison managers are able to point to positive achievements – as with horticultural and farming initiatives in New Zealand in 2010 – these are likely to be challenged or undermined by complaints that productive prison labour, because of its minimal wages, undermines the free market and has to be stopped. Indeed, in these societies, prisoners are reminded of the differences between themselves and free citizens at every level of their existence. They thus have no voting rights.9 They have no holidays, other than statutory holidays, when they are likely to be locked in their cells for longer than usual. A Radio New Zealand news bulletin, on 25 December 2011, informed listeners that women inmates at one prison would be receiving ‘no Christmas services, nor were they being allowed any visitors for security reasons. Priority was given to allowing the guards a day off.’ And there is still not the same degree of independent provision of health and education services as in the Nordic countries. Indeed, in New Zealand, these services continue to be provided exclusively by the Department of Corrections. This has particularly important implications in relation to which government department has responsibility for mentally ill prisoners, with regular conflicts between Corrections and the Department of Health, both wishing to absolve themselves of responsibility for this very problematic group. In England, while the National Health Service is now the provider of mental health services in prisons, demand far outstrips supply, meaning that, for many such prisoners, there will be minimal assistance. We were variously told, while visiting the English prisons, that ‘80 per cent of prisoners have mental health problems and there are no facilities here’, and that ‘90 per cent of prisoners have some form of mental health issue’. While the Nordic countries, themselves, have undergone significant deinstitutionalization programmes from the late 1960s, this does not seem to have resulted in the kind of migration of the mentally ill to the prison that has become characteristic of the Anglophone countries (Markström, 2003). At the same time, the Anglophone prisons face challenges that, in many ways, are the unforeseen products of ill thought-out, hasty, government policy. For example, the increasing numbers of prisoners serving indefinite sentences know that their only hope of release is to enrol in ‘programmes’, only to find that there are never enough places for them on the programmes. In these respects, and notwithstanding the commitment to ‘decency’ in England, it is as if the prison experience, for many inmates, has become ‘tighter and deeper’, as one commentator told us; a much more ‘intensive experience’, in the words of another. Prisoners have to ‘actively show compliance’, however illogical this might seem when the prison regimes cannot provide them with the wherewithal that the courts and parole board have stipulated they need to demonstrate before they can be considered for release.

Furthermore, prisoners in the Anglophone countries still seem subject to arbitrary and petty rules and procedures that not only affect their daily quality of life but continue to differentiate them from the rest of society. One New Zealand prisoner was, in 2010, thus refused permission to read The Naked Ape, by the famous anthropologist Desmond Morris (1967), on the grounds that it contravened the rule that prisoners were not allowed access to pornography. The response of the government in England to European Court of Human Rights (ECHR) rulings is usually to delay, ignore or water down their findings, or to finally accept the decision with bad grace, as if it was symptomatic of baffling EU idiosyncrasy. When, in 2011, after a 2004 ruling by the ECHR, the British government conceded that some prisoners were to be given the vote, Prime Minister David Cameron declared himself to be feeling ‘physically sick’ at this news (Daily Mail, 13 April 2011: 2). In other words, there is still an insistence that, not only must those in prison be shut away from the rest of society, but, at the same time, their exclusion, their worthlessness, their shamefulness, their ‘difference’ must be continually reinforced and emphasized, both to the prisoners themselves, and to the rest of society. Furthermore, we are still likely to find extraordinary levels of squalor and degradation in some Anglophone prisons. The Chief Inspector of Prisons in England maintains that ‘you look at the conditions some people are in and what’s happening to them and the lack of care they are getting and you think “This is just a disgrace ” ’ (The Independent, 6 November 2010: 3).

Overall, just as the variations in imprisonment rates point to substantive (rather than artefactual) differences in punishment, so the contrasts that run right through the respective prison systems of these societies also point to their very different ways of thinking about punishment.

Let us thus return to our initial question – the sociological (rather than any normative) imperative that drives this book – what is it about these types of societies that can account for their different ways of thinking about punishment? It is clear that these differences bear little relation to the levels of crime in these societies. If we bracket off inherent difficulties in making such judgements for all kinds of counting, recording and definitional reasons (as with imprisonment rates) then, as Figure 1.4 illustrates, we find that, from 1950 onwards – the point at which police records begin to be compiled with some consistency across these societies, with the exception of New South Wales10– there is a high level of symmetry between recorded crime levels.

Crime increased in all these societies for much of this period; from the 1990s it has stabilized or has begun to decline in all of them. However, as was noted in the Introduction, the pattern of imprisonment over the same period shows symmetry within the clusters, but not between them. As Figure 1.5 illustrates, while imprisonment rates have remained relatively stable in Sweden and Norway, and that for Finland has come down to the same kind of level, the imprisonment rates of the Anglophone societies have, for most of this time, been set on an upward spiral, one that has been accelerating from the 1990s, with the result that the gulf between the imprisonment rates of the two clusters of societies has become considerably wider.

That there is no direct fit between these prison rates and crime rates should come as no surprise. As David Garland (1990: 44) observed, punishment is not merely a ‘utilitarian instrument’, the use of which is determined by the quantities of crime being committed in a given society. Instead, it can also be understood as ‘an expressive form of moral action … a means of conveying a moral message, and of indicating the strength of feeling which lies behind it’. In these respects, it is as if punishment in the Anglophone societies, certainly from the 1990s, has come to carry an excessive, overladen baggage of signs and symbols that are unrelated to the crime rate. Instead, excesses of this kind – both in terms of the extravagant quantities of, and the quality of, punishment to be imposed – perform the function of giving messages of reassurance to anxious and insecure communities: inflammatory speeches are thus made by politicians about the need for more use of imprisonment through longer sentences and curtailment of early release mechanisms; and there are avowals that prisons will no longer resemble ‘holiday camps’, as with the Minister’s comments about the shipping container cells. Such excesses have been characterized by Garland (2005: 814) as being ‘a deliberate flouting of the norms of modern and civilized penology, a self conscious choice’. In addition, Ian Loader (2010: 350) suggests that penal excess is associated with ‘hyperactivity’; that is, ‘the satisfaction of immediate desires by recourse to speed, urgency, indulgence, decisiveness, here and now gratification’. Each exceptional case is treated as the norm, and the laws are rewritten time and again to adjust the entire prison and penal system to the issues raised by the one incident, as if each of these has the potential to make further breaches in the dam of social cohesion that can then only be repaired by recourse to such immediate but continuing repairs. In England, for example, between 1997 and 2008, 53 new Acts were introduced that dealt with crime and punishment: there had been only 42 crime-related Acts in the preceding century. As this has happened, the penal system has been relaid, patched over and rebranded, time and again, with increasingly complex and indigestible ideas and strategies. Thus, the Home Office (2002: 81) White Paper, Justice for All, set out its latest plans for an overhaul of the penal system that involved ‘a series of new and innovative sentences; anew suspended sentence called Custody Minus; reform of short custodial sentences through the introduction of Custody Plus; a new Intermittent Custody scheme that denies liberty through a custodial sentence served intermittently, for example, at the weekend, but allows the offender to continue working and maintain family ties; and a new special sentence for dangerous sexual or violent offenders’.

| Figure 1.4 | Crime rates, 1950–2010 (all six societies). |

Sources: England and Wales: Home Office (2012a, 2012b). Norway: Falck, von Hofer and Storgaard (2003); Statistics Norway (2012b). Sweden: Falck, von Hofer and Storgaard (2003); Swedish National Council for Crime Prevention (2012). Finland: Falck, von Hofer and Storgaard (2003); Statistics Finland (2012b). New Zealand: New Zealand Yearbook (various); New Zealand Police (2012). New South Wales: NSW Bureau of Crime Statistics and Research (1990, 2012).

| Figure 1.5 | Imprisonment rates, 1950–2010 (all six societies). |

Sources: New Zealand: New Zealand Yearbook (various); Department of Justice (1981); Ministry of Justice (1991, 2008). England and Wales: Home Office (2003). Sweden: Falck, von Hofer and Storgaard (2003). Norway: Statistics Norway (2012a). New South Wales: Official Yearbook of New South Wales (various); Australian Bureau of Statistics (1982, 2000). Finland: Falck, von Hofer and Storgaard (2003); Statistics Finland (2012a). All countries: World Prison Brief (2010).

These excesses have largely been avoided in the Nordic countries. Law-making usually involves lengthy deliberation in these societies, allowing all the evidence to be digested before arriving at a consensual, rather than polarizing, conclusion. As Jareborg (1995: 99) explained in relation to Sweden, ‘a legislative committee typically works for a number of years. All this serves to make the process as rational as possible. The issue is “cooled down” and political difficulties are normally solved within the committee whose members continually consult important persons in their respective political parties.’ Similarly, Lappi-Seppälä (2007: 69–70) refers to the revision of the Finnish penal code that commenced in 1972. After four years, ‘the Committee … laid down its principal paper. Again, after four years of preparation a specific Task-Force for criminal law reform was established … practically all key figures stayed active from the start to the closing of the project (1980–1999) and some remained in the work from their initial start in 1972 till the last official sub-reform in 1999’. At the same time, the use of punishment has been more ‘modest’ in this region. That is, it has been used with ‘restraint, parsimony and dignity’ (Loader, 2010: 351). The low rates of imprisonment are a reflection of these characteristics, as is the emphasis on de-stigmatizing the prison experience. Certainly, in recent years, there have been criticisms of this approach to punishment from within these societies, particularly from right-wing populist parties. However, it remains that there has been little by way of departure from existing expectations in the political mainstream. As a consequence, while punishment in the Anglophone societies has come to be characterized by its excesses, punishment in the Nordic societies represents an exception to this trend.

Why is it, though, that punishment performs such different moral actions and conveys different messages in these clusters of societies? In his review of Emile Durkheim’s contribution to penal theory, Garland (1990:75) writes that ‘the bonds holding people together and regulating their conduct are always moral bonds, ties of shared sentiment and morality – [but] where moral community is often absent or fragmented … the role of control and policing is much greater’. By the same token, ‘the more authoritative, stable and legitimate the political-moral order, the less need there is for terroristic or force-displaying uses of punishment’. On this basis, the Anglophone levels and intensity of punishment point to the inability of these states to maintain cohesion and social stability from other sources. Excessive levels of punishment become necessary to perform this role, hence the way in which law and order issues have come to feature so prominently in public and political discourse in these societies (Reiner, 2007). But this, of necessity, also means that cohesion and stability can only be achieved by excluding significant sections of the population – the rest of the community is united around their exclusion and feels the better for it (Durkheim, 1893/1933). While these excesses have come to play an increasingly central role in the governance of the Anglophone societies (Simon, 2007), it is their absence that is striking in the Nordic. Where, then, instead of ‘censure, condemnation and reprobation’, these signs and symbols convey more muted messages of forbearance, tolerance and restoration, this is indicative of the way in which these states are able to provide social cohesion without needing to attain this through excessive uses of punishment. Indeed, more inclusionary social mechanisms are likely to bind these communities together: ‘a strong and legitimately established moral order requires only token sanctions to restore itself and deal with violators’ (Garland, 1990: 60). Under these circumstances, there is no need for punishment to perform the role it has come to assume in the Anglophone countries.

How is it, then, that these societies have taken on these respective inclusionary and exclusionary characteristics? Various explanations for these differences have been put forward in recent years and have featured:

• The welfare state. Drawing on the work of Esping-Andersen (1990), Cavadino and Dignan (2006: 155) argue that there is a strong correlation between penal development and levels of investment in the welfare state. In the ‘social democratic model of welfare’ in the Nordic countries ‘[its] ideology, with its emphasis on equality and social solidarity and caring for those at the bottom of society, is likely to see the criminal as a victim of adverse social conditions’, thereby making possible low rates of imprisonment and relatively humane prison conditions. In contrast, in the Anglophone countries, with the much more restricted welfare arrangements of the ‘liberal’ model, ‘crime is seen as entirely the responsibility of the offending individual. The social soil is fertile ground for a harsh “law and order ideology”’ (ibid.: 24), with attendant consequences for high imprisonment rates and degrading prison conditions.

• Political economy. Lacey (2008) argues that the Nordic countries are characterized by co-ordinated market economies, in contrast to the liberal market economies of the Anglophone countries. The extensive welfare programmes of the former need funding that can only be provided from full employment and the taxation this generates, again necessitating low levels of imprisonment to avoid labour wastage. In contrast, the Anglophone societies are able to tolerate higher levels of imprisonment, since welfare benefits are much lower and do not need the taxation generated by full employment to sustain them. Instead, high levels of imprisonment in these societies become affordable ways of managing surplus labour.

• Political culture. Nordic politics are marked much more by consensus. With few exceptions, since 1945, parties of both the Left and Right have been committed to maintaining the broad parameters of the Nordic welfare state (Green, 2008; Lacey, 2008). In this region, the social democratic weltanschauung has been the dominant political force. In contrast, politics in the Anglophone countries are more conflictual, with a tradition of majoritarian Conservative governments.

• The mass media. As Green (2008) also demonstrates, there are important differences in the structure and content of the mass media in these societies. These are then reflected in the frameworks of knowledge that they construct, and through which crime and punishment issues are understood. Generally speaking, the Nordic media tend to play much more of a public information/ educational role than the Anglophone, which is driven more by sensationalism and scandal, of which crime and punishment have provided a regular supply.

Such scholarship tells us a good deal about some of the structural and cultural differences between these clusters, but also leaves important issues unresolved. For example, as regards the welfare state argument, this does not explain why the differences in welfare arrangements occurred in these clusters. Nor, in Cavadino and Dignan (2007), is there any significant account of how the supposed linkage between welfare and punishment actually takes place: only a correlation is established.11 As regards the political economy explanation, the relatively humane conditions in Nordic prisons would seem more problematic than in the above accounts: why, for example, should there be comparatively little social distance in this region between those in prison – most of whom contribute very little to the economic well-being of their country – and those outside? As regards the different approaches taken by the media and the political strength of social democracy in the Nordic region versus that of Conservatism in the Anglophone societies, what is it that has brought about these particular social characteristics?

Matters such as these reflect the way in which contemporary differences in punishment between the different types of modern society are likely to have lengthy historical roots (Whitman, 2003; Lacey, 2006). Indeed, the argument in this book is that the explanation for the current penal differences between the Anglophone and Nordic societies begins in the early nineteenth century, rather than the early twenty-first. Before then, penal affairs were conducted in much the same way in both clusters: they took the form of brutal, spectacular, public executions, and appalling, degrading, prison conditions (see Howard, 1792; Clarke, 1819; Hovde, 1943). Thereafter, however, different ways of seeing and understanding the world, different tolerances, different norms and conventions, different cultures – ‘all those conceptions and values, categories and distinctions, frameworks of ideas and systems of belief which human beings use to construe their world and render it orderly and meaningful’ (Garland 1990: 195) – began to emerge. Egalitarianism and moderation became two of the central features of Nordic culture, and helped to promote high levels of social inclusion. In contrast, there was more emphasis on individual advancement and division in the Anglophone, which led to higher levels of social exclusion. At various times along their subsequent routes of development, these values have been moderated and checked, distorted and enhanced, more concentrated in some individual societies within each cluster, less so in others. Overall, though, they have continued to provide different ways in which it has been possible to think about the world – and different ways in which it has been possible to think about punishment in each cluster. At the same time, rather than the discontinuities and abrupt departures from established modes of thinking that have become such a strong feature of the sociology of punishment in the aftermath of Foucault’s (1977) Discipline and Punish, it is the subsequent continuity in penal thought in the respective clusters of societies – even though, of course, the strategies in which this has been put into effect over this two-hundred-year period have been the subject of considerable change – that provides the analytical framework for this book.

How, then, did these long-term values emerge? As is explained in Chapter 2 (The Production of Cultural Differences), these were brought about by means of a constellation of social forces that began to take effect in the early nineteenth century. Their subsequent effects on the production of these value systems are traced through to the mid-twentieth century, using sources that include official commentaries, reports and enquiries, as well as memoirs, travelogues, literary works and diaries, in the manner that Norbert Elias (1939/1979), the most important scholar on the relationship between the historical development of Western culture and state formation, pursued in his magnum opus. As is explained in Chapter 3 (Two Models of Welfare State), these value systems then intersected with these societies’ respective models of welfare state, as they came to fruition in the mid-twentieth century. The purpose of this chapter is not to explain why the welfare state came into existence but, instead, how the two welfare models then institutionalized and gave a materiality to these ways of thinking about the world. In effect, the Nordic model helped to increase solidarity between citizens, and led to high levels of trust between individual citizens and between individuals and the state (Rothstein and Uslaner, 2005). In contrast, although the Anglophone model of welfare provided undoubted, often transformative, benefits, it was nonetheless constrained by its own limitations in bringing about a greater egalitarianism and cohesion. Thereafter, while the Nordic value systems have remained largely in place, notwithstanding the post- 1970s restructuring that has taken place right across modern society, those of the Anglophone have become exaggerated and extended, as the restraints that the liberal welfare state had previously been able to place on them have been largely pushed away.

In the last three chapters of the book, we show how these value systems have then provided different frameworks for thinking about punishment. As is shown in Chapter 4 (The Introduction of Modern Penal Arrangements), these came to light, first, with the much earlier demise of the death penalty in peacetime12 in the Nordic societies (for most intents and purposes, by the 1870s). The need for such a dramatic and highly symbolic spectacle of punishment as a way of affirming ruling class power was greatly reduced in these relatively egalitarian, cohesive and homogeneous countries. Characteristics such as these are less likely to favour physically destructive sanctions – as if the values that all members of these societies share are not going to be put at risk by a single act of crime, and do not need to be reinforced and upheld by dramatic penalties. In contrast, in the more stratified, divided and exclusionary Anglophone countries, the death penalty continued to carry great symbolic power: it was thought of as a necessary means of ensuring social order and stability, leading to its retention until the 1960s. Second, these differences in thinking about punishment came to light in the way that the modern prison began to perform different moral functions in these societies. During the late nineteenth century, it became a place of terror in the Anglophone societies, and was deliberately advertized as such. As a consequence, prisoners came to be seen as an altogether different species of human being – a species that attracted intense curiosity by virtue of their separation and incarceration in such a fearful place, but one that was simultaneously shunned, excluded, and set apart. In the Nordic countries, however, where Lutheran pastors had a more significant role in prison administration than the Anglophone chaplains, there was considerably more emphasis on education and the performance of productive, rather than afflictive, labour. In such ways, much shorter social distances between prison inmates and the rest of the community began to be established, making their difference seem less pronounced, and their eventual reintegration less problematic.

Chapter 5 (Two Welfare Sanctions) shows how the development of the Nordic ‘social democratic welfare sanction’, from the end of the nineteenth century to the 1960s, had the effect of simultaneously weaving a more extensive web of regulation around these societies while lessening the intensity and severity of punishment and exclusion. In the Anglophone countries, the ‘liberal welfare sanction’, over the same period, initially helped to temper the previous emphasis on penal exclusion and introduced a range of restraints on the extent and intensity of punishment. This brought a convergence in prison rates between these clusters by the mid-twentieth-century. This proved to be only temporary, however. As the post-1945 commitment to the liberal welfare state began to weaken in the 1950s and 1960s, so, too, did its ability to build the more extensive solidarity and cohesion of the Nordic societies. Instead, as inequalities and divisions became more pronounced, what inclusionary capabilities the liberal welfare sanction possessed became more limited. As a consequence, the differences in punishment between these clusters of societies widened: Anglophone prison populations began to increase and outstrip the Nordic countries during the 1960s and, while the prison conditions of the latter began to be advertized to the world as shining examples of Western humanity, those in the former became known for their overcrowded, deteriorating, conditions.

In Chapter 6 (Punishment in the Age of Anxiety), we show how, from the 1970s, the cultural values and welfare arrangements of the Nordic countries have, to a large extent, continued to insulate them from much of the Anglophone penal excesses that are to be found in response to the extensive social and economic restructuring of this period. In the ensuing ‘age of anxiety’, the penal differences between these societies have further widened and have become more extensive. These developments reflect the increasing importance of the role played by punishment in bringing about social cohesion and solidarity in the Anglophone countries. In contrast, the Nordic countries continue to rely on more inclusionary social measures for these purposes, and have no need for such penal excesses.