Analyzing objects through a cultural property framework draws our attention to the constitutive role of culture – to how “identity is asserted and difference claimed through expressive activities that deploy meaningful forms” (Coombe 1998: 23). It also elucidates the very complex processes through which objects are mobilized to make meaning – how they are used to constitute and produce new forms of knowledge. Theories regarding the intangibility of culture (Brown 2003; Appiah 2006) and anthropological analyses of the “new kinds of entitlement and processes of claim making” (Geismar 2013: 3) that emerge in relation to local formulations of ownership have become increasingly useful in attempts to track how objects – and, indeed intangible objects, such as oral histories and folklore – are invested with particular kinds of value. They also aid in untangling the diverse ways in which a language of rights can be deployed to make claims to and over particular forms of shared cultural knowledge. By considering the relationships between particular cultural objects, regimes of value, and definitions of ownership, many anthropological discussions of cultural property examine how the law is activated, subverted, and creatively deployed in order to make or prohibit rights claims over objects and the forms of knowledge embedded within them. In many cases where cultural property becomes the subject of heated debate, the law becomes an important arena in which power and hegemony can be both exerted and resisted. As Rosemary Coombe describes, the “law provides [the] means and forms for legitimating and contesting dominant meanings and the social hierarchies that they support” (1998: 29). In these contexts, the law is a domain in which claims are asserted, validated, or denied, thereby becoming an important “mediator for identifying and interpreting” (Aragon & Leach 2006: 623) particular forms of indigenous or local knowledge (see also Anderson 2005; Merry 1998).

How, then, might we approach objects and forms of knowledge that are not controlled, regulated, or overlooked by the law? In the absence of legal frameworks capable of mediating, identifying, or interpreting particular forms of knowledge, how can we make sense of claims that are made through objects – both tangible and intangible – and that seek to constitute particular forms of cultural value? Can a cultural property framework prove useful when analyzing objects and testimonies that do not reside in museums and national collections or that do not neatly fit into the category of cultural heritage? This chapter – and the photographs that accompany it – will examine an unruly corpus of objects, data, and testimonies that are central to the assertion of claims to new, alternative forms of historical, cultural knowledge in contemporary Spain. These objects and testimonies are unearthed – both literally and metaphorically – in mass grave exhumation projects that seek not only to recuperate the remains of those who fell victim to twentieth-century fascism, but also to change dominant historical narratives about the Spanish Civil War (1936–1939) and the ensuing Franco dictatorship (1939–1975). The human remains, personal objects, and archival documents exhumed and the testimonies collected in these endeavors are mobilized to create new forms of knowledge about the recent past. However, this evidence exists at the margins of Spanish law. Unlike other crime investigations, exhumations are not overseen by legal procedure. Only in some limited cases are the objects and human remains collected in these events treated as archaeological patrimony.1 The testimonies gathered in these endeavors, in contrast, are never treated as bearing a patrimonial value. However, they are invested with multiple forms of social and historical value, and they are mobilized to produce and constitute new forms of shared cultural knowledge. It is, in fact, their position outside the law that makes them potent objects through which different collectivities make claims to the recent past. By considering how these claims are made, this chapter will outline provocative new ways to think about cultural property and its relationship to the law.

***

Initiated in 2000, the Spanish Historical Memory Movement is a grassroots, civil society-led initiative that advocates for the rescue and recovery of individual and collective narratives regarding political violence exerted during the Spanish Civil War and the fascist dictatorship that followed it. Since its inception, this Movement, although heterogeneous in form,2 has consistently turned to forensic science as a tool for unearthing and making public the material traces of Spain’s violent past.3 Combating the lasting effects of a post-dictatorship Amnesty Law – which prohibits defining Franco’s victims as victims of crime – and the persistence of public discourses that hail collective forgetting as a mode of social and political modernization (Aguilar 2002; Labanyi 2002; Resina 2000), the Movement emphasizes recuperation – the retrieval of genetic, documentary, and narrative evidence – as a strategy for recasting individual loss and social marginalization as part of a larger phenomenon of state-sponsored, systematic violence (Espinosa et al. 2004). In this context, mass grave exhumation projects, specifically, initiatives that focus on the location, exhumation, and identification of individuals who fell victim to Spanish fascism, form part of a complex constellation of emerging social practices, whereby individuals and collectivities produce and mobilize new forms of knowledge about the recent past. In seeking to widen, amplify, and call into question dominant historical narratives that exclude the voices of victims and their surviving kin, the Movement produces new forms of historical knowledge that are grounded in shared, culturally produced ideas about the “facticity” and “objective” truth-telling capacities of scientific practice (Daston 1994; Daston & Galison 2007; Fleck 1979; Latour & Woolgar 1979).

Following the death of dictator Francisco Franco in 1975, Spain entered a democratic transition that focused on the promotion of political and social consensus. In this process, forms of collective remembrance were replaced by cultural forgetting. With the ratification of Spain’s Amnesty Law in 1977, amnesia was judicially institutionalized (Aguilar 2002). For the kin of those who fell victim to Francoist violence, this legal framework, paired with dominant discourses regarding the need to move forward by never looking back, reinforced the idea that kin-based narratives regarding intimate experiences with political repression were not apt for public circulation. For many, this meant that complex histories of forced disappearance, social and economic marginalization, and everyday forms of violence not only would be unrecognized by the Spanish state, but also would fail to be woven into dominant historical accounts of the war and its aftermath. The turn to forensic science battles cultural amnesia and legal amnesty through its ability to resurface evidence that helps undo the traditions of historical silence and erasure imposed by the dictatorship and the Spanish Transition. In the absence of courts of law equipped to deal with the genetic, osteological, and documentary evidence unearthed and made public in mass grave exhumation projects, forensic practice invests human remains, DNA samples, archival documents, and family photographs – objects that simultaneously resurface in these events – with scientific value. In their interactions with this new corpus of “hard” evidence and scientifically validated material, forensic experts, victims’ kin, memory activists, and local researchers make new claims regarding the events of the past. These claims, however, do not fit neatly into a discourse of rights that is legible to national law. These scientifically grounded acts of recuperation and retrieval occur at the unruly boundaries of legal procedure – a space in which the “objects of evidence” (Engelke 2009) regarding a particular collective history can be collected, but not submitted to or managed by courts of law.

The processes of recuperation and retrieval implicit in exhumation projects require the coming together of multiple forms of knowledge. Techno-scientific expertise is deployed in order to make sense of the human remains contained within mass graves. Forensic methods, carefully deployed by team members, make it possible to individualize skeletons, to estimate the age, sex, and stature of each victim, and to collect other forms of evidence – personal objects, bullet casings, and body placement – that can illuminate how and by what means victims were killed. However, this techno-scientific expertise can only be activated when paired with other forms of local knowledge.4 Testimonies given by victims’ kin are crucial in attempts to locate mass graves. Individual memories and community hearsay provide important data regarding how political repression was exerted and experienced in these local contexts. Kin-based knowledge – despite its fragmented form – helps reconstruct the events leading up to particular acts of violence. It also sheds light on the everyday, political lives of victims. When woven together, these bits and pieces of local, kin-based knowledge allow forensic experts to make connections between the osteological, genetic evidence that they exhume and a more complex historical narrative that describes not only the crime being investigated, but also the events surrounding these acts of disappearance. Similarly, archival documents extracted from state and municipal archives, as well as photographs and personal letters culled from the homes of victims’ kin, help further elucidate violent events and the social and political contexts in which they were embedded.

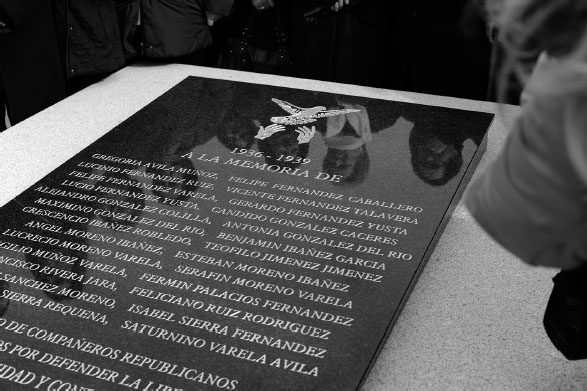

Mass grave exhumations in Spain are “para”-forensic events (see Holmes & Marcus 2005). Evidence is collected “as if” it was to be submitted to courts of law. It is, however, this “as if” status that is mobilized to make claims to historical knowledge that is embedded in the objects and narratives that are recuperated and produced in these endeavors. Standing outside the purview of the law, forensic and narrative evidence is transformed into forensic reports, doctoral dissertations, history texts, and documentary films. Photographs of unearthed mass graves – mounds of skeletons framed and put on view – are sequenced in public exhibitions, newspaper articles, and art books. They are plastered onto posters held high during memory marches. Memorials are erected. Dossiers lined with documentation and forensic analyses are compiled. Some of them are submitted to NGOs and international human rights organizations. Others are carefully guarded in the homes of victims’ kin and the archives at research centers. Through these forms of production and mobilization, historical “truth” is questioned, re-fashioned, and re-constituted. New narratives rooted in the “objectivity” of scientific practice are invested with forms of historical, political, and social value. Although this knowledge remains illegible to the law – unrecognized by the state and not incorporated into educational curricula – it is from this outsider position that members of the Historical Memory Movement make powerful claims to amplify and deepen the official record, to recognize and validate all that has been silenced and made to disappear.

***

The objects, narratives, and knowledge recuperated and produced in Spanish mass grave exhumation projects are not legally defined as “cultural property.” In fact, their very existence and circulation – their constitution and amplification – are products of attempts to recover and value events and experiences that have been silenced, left out, and unrecognized by dominant historical narratives, the very narratives that are produced in national museum collections and circulated in school textbooks and educational curricula. It is from this position outside the law – in the limbo between national patrimony, scientific object, and judicial evidence – that these cultural forms are deployed to make claims to a more nuanced historical record. Deploying a language of human rights that resonates transnationally but falls flat locally, forensic experts, memory activists, and victims’ kin – among others – seek to present new forms of knowledge to the Spanish public in an attempt to undo a culture of amnesty and amnesia that threatens to make these objects and the knowledge embedded in them irrelevant. If we take seriously Coombe’s suggestion that “The imaginative making of meaning is the quintessential human act, and culture is both its practice and its products” (1998: 44), Spanish mass grave exhumations and the creation and circulation of knowledge that are part and parcel of these endeavors are most certainly cultural forms. In fact, it is their exclusion from legal procedure and official state forms of recognition and their entanglement with scientific practice that make them powerful tools for expressing new forms of entitlement and creating novel, effective forms of historical claim making. If law is able “to generate signs and forms – signifying forms – through which difference is constituted and given meaning” (Ibid.: 29), exclusion from legal procedure creates new subject positions from which difference can also be wielded to make powerful claims over objects and the knowledge they represent.

In one of several essays on local knowledge, Clifford Geertz describes at length the relationship between fact and law. In his analysis, he identifies the “skeletonization of the fact” as a social process that defines the “[narrowing of] moral issues to a point where determinant rules can be employed to decide them” (1983: 170). For Geertz, legal process is the site where this reduction occurs. In Spain and in the context of the Historical Memory Movement, it is science that helps skeletonize facts. It is through the discovery and presentation of evidence – objects that are themselves skeletonized in very literal forms – that new moral categories and imperatives are developed. How these categories and imperatives are made to mean in cultural terms coincides with similar processes of social action through which recovered objects and testimonies are animated in order to constitute new, valid forms of historical knowledge. They also coincide with the assertion of a language of rites that claims these cultural objects as a collective form of patrimony that must be re-inserted into mainstream historical narratives and re-claimed, indeed recognized, by the Spanish state. Although Geertz is concerned with how the legal representation of facts is deployed to create particular shared social norms, his discussion of law as “a distinctive manner of imagining the real” (Ibid.: 173) is a thought-provoking way to approach areas of social life that exist at the margins of legal procedure. In the process of asserting claims to new forms of historical knowledge, the Historical Memory Movement imagines new possibilities regarding what can and should be recognized. In this way, the objects, testimonies, and forms of knowledge exhumed in these endeavors are heavy with cultural meaning. Perhaps more importantly, they also provide new modes of cultural-making that challenge long-term structures of silence and forgetting.

Images of recuperation: photographs of the Spanish historical memory movement

Source: Lee Douglas

Source: Lee Douglas

Source: Lee Douglas

Source: Lee Douglas

Source: Lee Douglas

Source: Lee Douglas

Source: Lee Douglas

Source: Lee Douglas

Source: Lee Douglas

Figure 21.12 A memorial located on the hill in Monte de Estépar where four mass graves were located.

Source: Lee Douglas

Source: Lee Douglas

Acknowledgements

I would like to thank Juan Montero Gutiérrez for his insightful comments regarding exhumations and patrimony in contemporary Spain. The visual essay that accompanies this text includes photographs taken in a variety of contexts and places. With that in mind, I am indebted to Ricardo Moreno and Felisa Herrero from Oropesa de Toledo, who shared their experiences and photographs with me. My fieldwork in Oropesa would not have been possible without Ricardo’s incredible expertise and guidance. I would also like to extend my gratitude to members of the technical-scientific team that conducted the Monte de Estépar exhumation in July of 2014, the second site where many of these images were taken. In particular, I would like to thank the project directors Francisco Etxeberria Gabilondo (Aranzadi Sciences Society), Juan Montero Gutiérrez (Provincial Coordinating Committee for the Recovery of Historical Memory – Burgos), Ignacio Fernández de Mata (University of Burgos), as well as the incredibly talented student volunteers who made this work possible. Both Lourdes Herrasti and Jimi Jiménez from the Aranzadi Sciences Society provided guidance regarding the publication of the images taken during this exhumation. Finally, I would like to extend my sincerest thanks to Haidy Geismar and Jane Anderson for the invitation to contribute this chapter and its accompanying images to this volume.

Notes

1 On September 23, 2011, the Official State Gazette, also known as the BOE, made public the “Protocol for Carrying out Exhumations of Victims of the Spanish Civil War and the Dictatorship,” which outlined a detailed methodology to be followed in all mass grave exhumation projects (see Etxeberria 2011). The Protocol was elaborated in compliance with the Spanish Historical Memory Law passed in 2007. It suggests that all archaeological interventions completed as part of mass grave exhumation projects should follow the precautions outlined in Law 16/1985 that oversees the treatment of archaeological patrimony. A select group of Autonomous Communities, including Aragón and later Asturias and Castille-La Mancha, have developed local historical memory protocols that take into account the archaeological treatment of objects that may have patrimonial significance. The case of Aragón is unique in that this Autonomous Community has passed legislation that situates mass grave exhumations under the administrative tutelage of the General Office of Cultural Patrimony (Montero 2010: 73). However, as noted by archaeologist Juan Montero Gutiérrez (2010), there is a vast difference between national and regional protocols and the creation of laws that define these initiatives as part of a larger national project to recuperate national patrimony (see also González Ruibal 2007, 2009). Mass grave exhumation projects, like many historical memory practices in Spain, face a legal void that makes it difficult to define how the objects recuperated in these endeavors should be treated.

2 It is important to note that the Spanish Historical Memory Movement, also known as the Movement to Recover Historical Memory is complex and heterogeneous. Local, regional, and national iterations of historical memory struggles – and the political claims and tensions between different groups of memory activists working at these different levels – mean that the Movement cannot be described in simple, homogeneous, or national terms (Ferrándiz 2014). However, as noted, the Movement has been consistent in its uptake of forensic science as a tool in the struggle to make new claims to alternative historical narratives. In this chapter, I will refer to this phenomenon in general terms in order to address how the objects and narratives recuperated in these investigations might be framed as a kind of cultural property and what implications this might have in terms of widening discussions about how different forms of knowledge and culture are re-claimed in post-violence contexts where the crimes of the past are not legally or judicially recognized.

3 In September 2000, Emilio Silva, a journalist and the grandson of a desaparecido (or disappeared person) advocated for the exhumation of a mass grave located on the outskirts of Priaranza del Bierzo in León. Local hearsay and family narratives inherited by Silva confirmed that in October 1936 several men had been rounded up, extra-judicially killed, and dumped into a ditch at the edge of town. Members and volunteers of the Association for the Recovery of Historical Memory worked side-by-side with members of the Aranzadi Forensic Team, uncovering and recuperating the bodies of 12 men. The remains included those belonging to Silva’s paternal grandfather. Although community exhumations of mass graves had been common in the late 1970s and early 1980s in Spain, this was the first time that the remains of victims of fascist repression were exhumed and identified through the application of scientific methods and the use of genetic DNA testing (Silva & Macías 2003).

4 For an ethnographic description of the relationship between techno-scientific expertise and kin-based knowledge, see “Mass Graves Gone Missing: Producing Knowledge in a World of Absence” (Douglas 2014).

Bibliography

Aguilar, Paloma. 2002. Memory and Amnesia: The Role of the Spanish Civil War in the Transition to Democracy. New York: Bergen Books.

Anderson, Jane. 2005. “The Making of Indigenous Knowledge in Intellectual Property Law in Australia.” International Journal of Cultural Property, 12(3): 345–371.

Appiah, Anthony Kwame. 2006. Cosmopolitanism: Ethics in a World of Strangers. New York: W. W. Norton.

Aragon, Lorraine V. and James Leach. 2008. “Arts and Owners: Intellectual Property Law and the Politics of Scale in Indonesian Arts.” American Ethnologist, 35(4): 607–631.

Brown, Michael F. 2003. Who Owns Native Culture? Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

Coombe, Rosemary. 1998. The Cultural Life of Intellectual Properties: Authorship, Appropriate, and the Law. Durham, NC: Duke University Press.

Daston, Lorraine. 1994. “Marvelous Facts & Miraculous Evidence in Early Modern Europe.” In Questions of Evidence: Proof, Practice, & Persuasion Across the Disciplines. H. J. Harootunian, J. Chandler, and A. Davidson, eds. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

Daston, Lorraine and Peter Galison. 2007. Objectivity. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press.

Douglas, Lee. 2014. “Mass Graves Gone Missing: The Production of Knowledge in a World of Absence.” Culture & History, 3(2): e022.

Engelke, Matthew. 2009. “The Objects of Evidence.” In The Objects of Evidence: Anthropological Approaches to the Production of Knowledge. M. Engelke, ed. Oxford: Blackwell Publishing.

Espinosa Maestre, Francisco, Julián Casanova, Conxita Mir and Francisco Moreno Gómez. 2004. Morir, Matar, Sobrevivir: La Violencia en la Dictadura de Franco. Madrid: Editorial Critica.

Etxeberria Gabilondo, Francisco. 2011. “Exhumaciones Contemporáneas en España. Las Fosas Communes de la Guerra Civil.” Boletín Galego de Medicina Legal y Forense, 18(1): 13–28.

Ferrándiz, Francisco. 2014. El Pasado Bajo Tierra. Exhumaciones Contemporáneas de la Guerra Civil. Madrid: Anthropos.

Fleck, Ludwik. 1979. Genesis and Development of a Scientific Fact. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

Geertz, Clifford. 1983. “Local Knowledge: Fact & Law in Comparative Perspective.” In Local Knowledge: Further Essays in Interpretative Anthropology. New York: Basic Books.

Geismar, Haidy. 2013. Treasured Possessions: Indigenous Interventions into Cultural and Intellectual Property. Durham, NC: Duke University Press.

González Ruibal, Alfonso. 2007. “Making Things Public: Archaeologies of the Spanish Civil War.” Public Archaeology 6(4): 203–226.

González Ruibal, Alfonso. 2009. “Arqueología y Memoria Histórica.” Patrimonio Cultural de España 1: 103–122.

Holmes, Douglas & George Marcus. 2005. “Cultures of Expertise and the Management of Globalization: Toward the Refunctioning of Ethnography.” In Global Assemblages: Technology, Politics, & Ethics as Anthropological Problems. Ong Aiwha & Stephen Collier, eds. Oxford: Blackwell

Labanyi, Jo. 2002. “Engaging with Ghosts; or, Theorizing Culture in Modern Spain.” In Constructing Identity in 20th-Century Spain. Jo Labanyi, ed. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Latour, B. & S. Woolgar. 1979. Laboratory Life. The Construction of Scientific Facts. Beverly Hills: Sage Publications.

Merry, Sally. 1998. “Legal Pluralism.” Law & Society Review 22(5): 869–901.

Montero Gutiérrez, Juan. 2011. “Exhumando el Legado Material de la Represión Franquista. De la Percepción Social a la Encrucijada Jurídica y Patrimonial.” In Recorriendo la Memoria/Touring Memory. Jaime Almanza Sánchez, ed. Oxford: Archeopress.

Resina, José Ramón. 2000. “Introduction.” In Disremembering the Dictatorship: The Politics of Memory in the Spanish Transition to Democracy. José Ramón Resina, ed. Amsterdam: Rodopi.

Silva, Emilio and Santiago Macías. 2003. Las Fosas de Franco. Madrid: Temas de Hoy.