7

“For God’s Sake, Comb Your Hair! You Look like a Vilde Chaye”

Jewish Lesbian Feminists Explore the Politics of Identity

Lesbian feminism emerged as a significant outgrowth of radical feminism by 1970. Lesbians were dissatisfied with their invisibility within radical feminism and with being considered “threats” to the liberal women’s movement and created a distinct politics, developing theories, publications, organizations, and coalitions to promote their agendas. They were interested not only in cultural and lifestyle changes but also in the broad transformation of social relations, patriarchal culture, and gender and sexual norms. Their innovations in theory and practice signaled new directions in the radical feminist movement and resulted in lasting changes.1

Just as feminism had become a portal into religious Judaism for previously unidentified Jewish feminists, lesbianism became another channel into a deepening Jewishness for women alienated from their Jewish identities and interested in exploring woman-woman relationships. For Jewish women, it was a particularly useful anchor, as Melanie Kaye/Kantrowitz explained: “As Jewish women, we are often blamed for our strength. When I became a lesbian and no longer had to care what men, Jewish or otherwise, thought of me, I came into my power. As a lesbian I learned fast and ecstatically that women liked me to be strong. I began to enjoy, build, and relax into my full self.”2 These identities developed over time, as lesbian feminist activists became aware of their Jewishness in the context of a lesbian feminist movement that, to their surprise, often harbored anti-Jewish feelings.

Jewish lesbian groups began to coalesce in the mid- and late 1970s. One of the first groups came together spontaneously at the Michigan Womyn’s Music Festival in 1976—“somebody just called a session and said, ‘let’s get together as Jewish lesbians.’” Grassroots groups also formed in Los Angeles, San Francisco, New York, Boston, and Chicago, as well as in such smaller cities as Madison, Wisconsin, and Ithaca, New York. In addition to Di Vilde Chayes (Yiddish: the wild beasts), the subject of this chapter, the movement included such colorfully named groups as Needless Worry, Nashim (Hebrew: women), Dyke Shabbas, the Balebustehs (Yiddish: the bossy women), and Di Yiddishe Shvestern (Yiddish: the Jewish sisters).3

Jewish lesbians shared many commonalities with nonlesbian Jewish feminists, although the struggle of Jewish lesbians to be accepted among straight Jewish communities involved particularly fierce struggles. Sometimes Jewish lesbian and straight women came into direct conflict, yet both were engaged in exploring the personal and political meanings of linked oppressions. “In proper Jewish tradition,” Evelyn Torton Beck explained in the introduction to her important 1982 book Nice Jewish Girls: A Lesbian Anthology, “we ask many questions. It is our way of coming to know. . . . How are we, as Jews, different from each other? . . . How have we internalized myths and stereotypes, particularly about Jewish women? What similarities do we share with lesbians from other ethnic groups?” The desire of Jewish lesbians to be “all of who we are” in a world that was homophobic and anti-Semitic was the common theme of the book.4

Di Vilde Chayes, formed by Beck and half a dozen other Jewish lesbians in 1982, provided a safe space within which members could discuss difficult topics regarding Jewish lesbian identity. Though it lasted less than two years, Di Vilde Chayes explicitly confronted anti-Semitism, within and outside the radical feminist movement. Its seven members, who were writers, editors, and publishers, lived in dispersed locations, so they could not gather regularly. Yet they became a support group for each other as they grappled with the interrelated issues of Jewish/lesbian identity and anti-Semitism. The chapter focuses on the Jewish stories of five collective members—Evelyn Torton Beck, Gloria Greenfield, Irena Klepfisz, Melanie Kaye/Kantrowitz, and Adrienne Rich—whose public writings during this period provide context for Di Vilde Chayes’ ideas. Bernice Mennis and Nancy Bereano were the other group members.5

Di Vilde Chayes was closely associated with Nice Jewish Girls, which contained contributions from all the collective members with the exception of Bereano. The anthology “grew out of the political ferment and activism of developing the Jewish lesbian feminist consciousness,” Beck recalled. At the time, Jews were silent about homosexuality; according to Beck, “the juxtaposition of Jew and lesbian was so unthinkable it seemed absurd.” When Beck’s mother’s tried to broach the idea of her lesbianism to her rabbi, he replied that it could not possibly be true. That is why the title of the anthology was so important, Beck believes. “We were Nice Jewish Girls AND lesbians, which of course made us NOT NICE.”6 “The entire anthology is an act of resistance,” Gloria Greenfield wrote in a cover blurb for the book.

Nice Jewish Girls benefited from the encouragement of the Jewish lesbian community, and in turn, it became a major impetus to creating and nurturing a Jewish lesbian consciousness within the lesbian feminist movement.7 The book sold ten thousand copies in less than a year and made an enormous impact on the women’s community. Moving beyond Ashkenazi and US boundaries, it included contributions from Rachel Wahba, a Sephardic/Arabic Jewish immigrant, and Savina Teubal, of Syrian descent, who grew up in Argentina, and from Marcia Freedman and Shelly Horwitz, Americans who had made aliyah to Israel.8

In Beck’s preface to the second edition (1989), she spoke of the lively discussions the book had generated. Several consciousness-raising lesbian groups were established in its wake, and a Jewish lesbian newsletter, Shehechiatnu (a feminized version of the Jewish blessing shehechianu), was put out in different cities following the book’s publication. Non-Jewish women also began to form groups to deal with their own anti-Semitism.9

Some Jewish lesbian feminists had already played notable roles in the lesbian and Jewish feminist movements. Photographer Joan Biren (or JEB), co-founder of the Furies, an early 1970s lesbian collective, published her early work documenting the lesbian movement in the group’s newspaper. Batya Bauman, co-founder of Lilith, wrote a piece in the magazine’s 1976 inaugural issue linking her lesbian, feminist, and Jewish identities.10

Autonomous groups of Jewish feminists, lesbian feminists, and Jewish lesbian feminists came to function within and alongside the general feminist movement. Paralleling the views of religious Jewish feminists, Melanie Kaye/Kantrowitz explained that the collective was a natural, authentic form for Jewish women because in Jewish life, “the community, not the individual, is the unit of solution.” “Judaism specifically incorporates time for each individual to make private prayer, allows for a huge range of debate and disagreement. But one is not truly Jewish alone: one is Jewish in community with others. Problems are conceived of in collective terms, and solutions likewise.”11

For the women of Di Vilde Chayes, the invisibility of Jewish women within the feminist movement was a consequence of the movement’s conscious universalism. In a piece for Womannews in 1981, Irena Klepfisz suggested another reason: low self-esteem led Jewish women to internalize anti-Semitism, contributing to their silence about their Jewish roots. Klepfisz remarked on the large proportion of Jewish women in the feminist movement and their fear in naming themselves as Jews. For these women, “the number of Jews active in the movement is not a source of pride, but rather a source of embarrassment, something to be played down, something to be minimized.”12

Klepfisz and other Di Vilde Chayes members saw the invisibility of Jewish women as lesbians and as feminists as a major factor in what they named as anti-Semitism. By linking homophobia and anti-Semitism and urging lesbian Jewish feminists to make themselves visible as Jews and as lesbians, the collective raised consciousness about the multiple forms of discrimination to which Jewish women were subject. Participation in the group emboldened them to create new platforms of expression and take public stances. Members began to speak about their Jewish beliefs and values. Such influential writings as those contained in Kaye/Kantrowitz and Klepfisz’s anthology The Tribe of Dina came out of their collaboration.13

For Jewish lesbians, becoming visible as Jews and becoming visible as lesbians were linked processes. “Jewish invisibility is a symptom of anti-Semitism as surely as lesbian invisibility is a symptom of homophobia,” Beck wrote in Nice Jewish Girls.14 The alternative—hiding in the closet—led to oppression. Yet Beck believed that it was much more fearful to declare herself a Jew in lesbian circles than a lesbian in the Jewish world. This was striking, because for Beck as for Klepfisz, child survivors of the Holocaust, Jewishness was a core identity. Such an inbred sense of Jewish selfhood was not the case for Kaye/Kantrowitz and Adrienne Rich, who grew up as assimilated Jews. Though identity struggles of Di Vilde Chayes members varied, for all, coming out as Jews within the feminist movement paralleled their claiming sexual identities. Understanding marginalization in one venue promoted greater understanding of other displacements.

But marginality had its limits. As Beck wrote in Nice Jewish Girls, “if you tried to claim both identities—publicly and politically—you were exceeding the limits of what was permitted to the marginal. You were in danger of being perceived as ridiculous—and threatening.”15 Acknowledging multiple oppressions multiplied the risks of embarrassment and vilification. “It is a radical act to be willing to identify publicly as a Jew and a lesbian,” Beck declared. Rich called it “dangerous.”16

Evelyn Torton Beck: “Making Ourselves Visible as Jews”

“I was born in 1933 in Vienna, Austria, the year Hitler came to power; his shadow shadowed me.” So Evelyn Torton Beck began the narrative of her life as a Jewish lesbian feminist at the NYU “Women’s Liberation and Jewish Identity” conference. The Holocaust framed Beck’s early life and memories. Her father, born in Poland, had served in the Austro-Hungarian army, but in 1938, in her presence, he was arrested by two SS men, taken from their home, and sent to Dachau and Buchenwald. Beck’s mother, born in Vienna, was proud of the fact that she had stayed in school until sixteen, longer than most girls of her social class. As an Austrian Jew, she felt a sense of social superiority to eastern European Jews, although she married one. So, in a sense, Beck related, “I come from an intermarriage among Jews.”17

Beck did not have a strong religious education, even though her father, whom she called a “benign patriarch,” believed in tradition. Although he was not Orthodox, he went to shul often and observed the holidays, although he did not make them meaningful to his children. Beck’s mother, who had little Jewish education, wanted desperately to believe, but the murder of her mother and other family members in the camps made that difficult, if not impossible. Having been raised in patriarchal, anti-Semitic Vienna at the turn of the twentieth century, she was as ambivalent about being a Jew as she was about being a woman. This heritage was passed down to Beck, who continued to battle against the tensions that these identities engendered, but they lessened or even resolved when she became involved in Jewish lesbian feminist activism.18

After Beck’s father was arrested and sent to the concentration camps, where he was tortured and made to do slave labor for a year, the family was evicted from its home and sent to live in one room in the ghetto. Beck was thrown out of kindergarten, called “dirty Jew,” and shunned by her playmates. Within a year, her father was inexplicably released, perhaps because of money the Gestapo collected daily from her mother, as it did from all relatives of the imprisoned who could afford it. Beck also thinks her mother may have used her as a kind of bait: “I was very pretty and did not look Jewish. I had green eyes, blond curls,” she remembered. “It felt as if she wanted me to smile and kind of flirt with the guards so that maybe they would release my father; and for all I know, it worked.”19

One day, miraculously, in 1939, her father reappeared. The family was able to get visas to Italy but had to leave Beck’s grandmother and other relatives behind. All perished at Auschwitz. The fact that Beck was saved, while her beloved grandmother died, became part of the burden that she brought with her when the family resettled in the United States after a distant relative agreed to take them in.

The family started over in Brooklyn. It was not fun being a “greenhorn,” Beck recalled, “wearing only hand-me-down clothes and sitting for hours in clinics, waiting to be served by hospitals that took in poor people.” Beck compensated by being an excellent student; she still has an essay she wrote in German titled “I Survived It All by Reading.” “I don’t know when I first got the idea that all that had happened to my family had anything to do with being Jewish,” she said. But she described what seemed likely to her: “The early injustices that I suffered through and observed had everything to do with the way I saw myself as a woman and as a Jew. These experiences . . . fueled my impulse to create a better world that has then formed my entire life, wherever I’ve been.”20

In the U.S., Beck’s father tried to make a traditional Jew out of her, sending her to afternoon Talmud Torah, but she hated the rabbis’ rigidity and quickly dropped out. She preferred the socialist-Yiddishist Shalem Aleichem Folkshule that she next attended, with its vision of a Jewish homeland in a world of peace and its woman teacher. She can still see herself at twelve or thirteen, collecting money for the Jewish National Fund on the subways—hiding in the back, but when train stopped, she would step into the middle and call out in the loudest voice she could muster, “Ladies and gentlemen . . . ,” and a plea for donations would follow.21

Shortly after arriving in Brooklyn, Beck joined the Socialist Zionist group Hashomer Hatzair, whose idealism had given her a sense of hope. The time there remains a pivotal experience in her life. Israel, not yet a state, was her utopia. “There was a real sense of purpose to what we were doing,” she recalled. “I loved Hashomer Hatzair with its vision of equality. We had strong women leaders; we shared our clothing, we shared our money, we also shared cigarettes.”22 And she loved dancing all night. Beck dreamed of making aliyah to Israel, but her father’s Zionism stopped at the thought of his daughter’s moving so far away. Later, she became active in a more moderate Zionist group. These early years of Jewish activism shaped her sense of purpose, even though for a time, Jewish identity was no longer central to her life.

Living at home, Beck went to Brooklyn College; she tried the Hillel Society but found the group too “bourgeois” for her Bohemian, prefeminist sensibilities, its Judaism lacking meaning. She quickly married, the expected path even for young rebels. “I was only able to get out of my parental home when I got married,” she said, “out of my house into my husband’s house.” Like her mother, she also “intermarried,” but to a red-diaper baby, the son of Jewish communists.23

Beck’s husband helped her find a scholarship to Yale, where, as a Brooklyn Jew, she felt very alien, but she completed her master’s degree. It was at Williams College, where her husband took a job because she had unexpectedly gotten pregnant, that she first encountered WASP anti-Semitism—the powers that be lodged the only other Jew on the faculty in their home. Her first child, a daughter, was born there. Living in that New England Protestant environment made her more self-conscious about being a Jew, but it was not a comfortable identity. When, after a year in New Orleans and a travel fellowship around Europe, Beck’s husband took a job at the University of Wisconsin, she returned to graduate school, doing her Ph.D. dissertation on the impact of Yiddish theater on the work of Franz Kafka.24 Clearly Jewish themes called to her.

After Beck had revived her study of Yiddish in her doctoral work, she was introduced to Isaac Bashevis Singer when he was a visiting professor at Wisconsin, and he soon asked her to become his translator. She agreed, not realizing that she was one of an army of women translators of his work. She later published the first feminist critique of his work, pointing to the many ways in which he used gender stereotypes to characterize and vilify women.25 Beck’s growing interest in Yiddish led her to take her first activist role in the academy, spearheading a petition to create a section on Yiddish language and literature within the prestigious Modern Language Association. The petition succeeded; the section was approved in 1975 and has continued to flourish. “I am the grandmother of Yiddish in the MLA,” Beck said with pride.26

Beck spent two years as a visiting professor at the University of Maryland after her book on Kafka was published, then went to the University of Wisconsin with a joint appointment in comparative literature and German. She became part of a team that developed the Women’s Studies Program, creating courses on the full spectrum of Jewish women’s lives as well as courses on lesbian culture and minority women.

Beck and her husband divorced in the early 1970s. Encouraged by feminism’s normalization of women’s love for women, she came out as a lesbian, an identity that she had feared was hers when she was an adolescent but that was so unthinkable in the context of her growing up that she decided she was not one.

Beck’s activism in lesbian feminist communities strengthened her Jewish identity, to which she returned incrementally through her research and teaching and as a result of the anti-Semitism she experienced in feminist movements. Her recovery of Jewish identity was deeply impacted by feminism, as the Judaism with which she had grown up left little room for women’s agency. When she had a son, for example, her father and husband fought about whether he should be circumcised. Beck was not part of that conversation: “it’s like I didn’t exist.”27 As a feminist, she understood why this incident so traumatized her and why she had to leave patriarchal Judaism behind.

In 1978, Beck attended her first official public gathering of Jewish lesbians as part of the Wisconsin regional meeting of the National Lesbian Feminist Organization. At the beginning, the groups had no agenda other than for the women to affirm that “they were not only lesbians but also Jewish.” But the assertion of lesbian identity had ripple effects. The “tearing away of a veil, that recognition that you are, in fact, really different,” connected these dual experiences of marginality. It is a “less radical outsidership to be a Jew,” Beck asserted, “but . . . you are in fact, really different, even in a subculture.”28

Beyond marginality, Beck suggested a more positive association between lesbianism and Jewish women’s identity, differentiating Jewish lesbian feminists from nonlesbian Jewish feminists. “What it means to affirm a lesbian identity is a kind of full and total acceptance of the female,” a reaffirmation of Jewish women’s experiences. Jewish culture fostered a “lesbian way of being-in-the-world” that encouraged Jewish women to be affectionate and physical with each other. There was a “whole female culture” in Jewish families and a much-appreciated tradition of female accomplishment in Jewish history linked to radical social change.29

Yet Beck recognized the danger inherent in making visible links between Jewishness and lesbianism. “As soon as you begin to say, ‘We are active in this movement and we are lesbians,’ straight feminists might fear a ‘Lesbian takeover.’” “Making ourselves visible as Jews” also posed a threat. “You don’t have much space between being invisible as Jews or being too visible as Jews”; the possibilities for stereotyping and exclusion were ever present. The lesbian feminist movement ought to have been a “place of refuge” for identified Jewish women, but Beck had not yet found a safe place there. Perhaps it was because lesbian Jewish women were more willing to be in touch with their oppressions that they seemed more sensitive to prejudice and anti-Semitism than other feminists were.30

Like several other members of Di Vilde Chayes, Beck experienced several fraught confrontations over anti-Semitism and racism at feminist conferences. In June 1983, the National Women’s Studies Association (NWSA), in order “to face troubling divisions within its own movement,” devoted a plenary session at its fifth annual conference at Ohio State University to the subject of “racism and anti-Semitism in the women’s movement.” In addition to Beck, the session included Arab philosopher Azizah al-Hibri; the black feminist writer, editor, and critic Barbara Smith; Carol Lee Sanchez of San Francisco State University; and Minnie Bruce Pratt, editor of Feminary. Many of the two thousand delegates at the conference attended the racism/anti-Semitism session—the most emotionally compelling and “potentially volatile” of its plenaries.31

Speaking as the only Jew on the panel, Beck admitted that she had never been “as terrified” as she had been at the prospect of speaking at NWSA “as a Jew.” “I could attribute it to my being an immigrant survivor who lived under Hitler,” she said, “but that would be wrong. I would bet that many or even most American Jews would feel equally afraid if they were in my place. This fear is never extinguished entirely, even in times of relative safety. My parallel: Jews live with a subliminal fear of encountering anti-Semitism the way women live with the fear of rape.” As a Jewishly identified Jew, she felt she could become a “lightning rod for the anti-Jewish feeling which often bubbles beneath a surface which denies its existence.” This was the way anti-Semitism operated, making Jews feel “that it is not OK to talk about anti-Semitism in and of itself, and it is also not OK to talk about it in the same breath as racism.”32

In the presentation, Beck described fifteen markers of anti-Semitism, ranging from “obvious forms” (bombing, beatings, graffiti, slurs, and stereotypes) to subtle ones (holding double standards, trivializing Jewish oppression, not respecting cultural differences, making Jews invisible). She included the problems of equating Jews with Israel and “making the term ‘Zionist’ mean only the worst kind of fanatic.” She observed feminists’ “verbal jujitsu” around the term, condemning NWSA for refusing to amend its constitution to oppose “anti-Semitism” unless it specifically referred to “Arabs and Jews.” Beck supported the recognition of anti-Arab prejudice, but as a separate form of racism. According to all dictionaries and common usage, Beck insisted, “anti-Semitism means prejudice and hatred against Jews. . . . If it takes the term ‘Jew-hating’ to make the NWSA take a clear position, so be it. As a Jew I will not feel safe here, and will not believe in the NWSA’s commitment to stop Jew-hating, if it does not do so.” NWSA did not alter the preamble as Beck had urged: it chose to define anti-Semitism in its constitution as an oppression directed “against both Arabs and Jews.”33

Anti-Semitism was not easy to discuss. In 1985, at a feminist studies conference in Milwaukee, where Beck gave a paper about the subject, hostile and demeaning remarks were repeatedly directed at “you Jews.” Yet the attack received barely any comment from “paralyzed” audience members, about one-third of whom may have been Jewish, and was absent in an account of the event in a feminist multicultural text.34 Beck described the difficulty of including Jewish themes in feminist discourse. “First, there is the fear of attack that produces a protective silence; second, is the fear of being perceived as too ‘demanding,’ ‘pushy,’ or ‘politically incorrect.’ Third, and possibly more than any other factor, the fear of being excluded keeps Jewish women silent. Speaking and writing about explicitly Jewish themes (or even including them substantially) raises the worry that the work will be perceived as marginal, and therefore not as widely read and discussed.”35 With Jews invisible and excluded, the “‘benign’ anti-Semitism of indifference and insensitivity” took over. Feminists categorized Jews with a radical “otherness” that was denied at the very moment it was created. “If Jews do not fit in,” Beck worried, “it is quite likely that other groups may not fit into the conceptual framework we have constructed.”36

Yet Beck maintained her optimism. “Across the U.S. and in many other parts of the world, Jewish lesbian-feminist communities were in the process of coming together; their very existence was exhilarating and inspired hope that by organizing around our differences, would come unity, and that our feminist projects, in all their complexity, would succeed.”37

Gloria Greenfield: “Standing Up in Defiance”

The idea for Nice Jewish Girls was born when Gloria Greenfield attended Beck’s workshop on Jewish lesbian feminists at the 1979 National Women’s Studies annual conference and passed Beck a note asking if she would like to put together an anthology around this topic. Three years prior, Greenfield, along with friends Pat McGloin and Marianne Rubenstein, founded Persephone Press in the attic of their Watertown, Massachusetts, home. Within a few years, the press was “making waves in the bookselling community,” according to one report, and had become “one of the leading specialized independent publishers in the nation.”38 Publishing fiction, poetry, and anthologies on feminist topics, the press created an innovative list that sold well at home and abroad. At the UN World Conference on Women in Copenhagen in 1980, Persephone was featured as the leading lesbian feminist publisher in the world, its list including important works by women of color and Jewish women.

Greenfield had been raised with a strong Jewish identity. Born in Coney Island in 1950 to Sol and Marilyn Greenfield, she was five when her family became eligible for a home loan available to World War II veterans. With her parents, paternal grandmother, and sister, Greenfield left their housing project in Greenpoint and moved into a home in a working-class neighborhood on the “wrong side of the tracks” in Bay Shore, Long Island.39 Before learning how to sew her own clothes in middle school, Greenfield often felt self-conscious, wearing the cast-off clothes that her mother had picked up at synagogue rummage sales. Neither of her parents had graduated from high school, but they instilled a strong work ethic in their two daughters. Her father worked two jobs, driving a cab during the day and working as an attendant at Pilgrim State Hospital at night. Her mother worked on assembly lines prior to becoming a custodian at Greenfield’s high school. When a roller rink was built in Bay Shore, Greenfield’s parents took on additional part-time jobs at the roller rink so that their daughters could take private roller-skating lessons. Greenfield mixed easily with the wealthier classmates at school and at the Reform synagogue, where she and her sister received financial assistance to attend religious school.

Just as growing up as the child of working-class Jews in the Long Island suburbs felt “weird,” Greenfield’s Jewish upbringing as the daughter of a self-identified, strongly Jewish-identified atheist father and observant mother seemed “schizophrenic.” Her mother lit Shabbat candles every Friday night, attended synagogue, changed the dishes at Passover, and followed the Jewish calendar. She had grown up on the Lower East Side and with her siblings had run a newsstand at the end of the Williamsburg Bridge on Delancey Street. Her father, who had grown up in New York’s densely populated Jewish neighborhood of Williamsburg, rebelled against his family’s religious observance. Nonetheless, Greenfield’s sense of class dissonance was accompanied by childhood feelings of religious belonging.

Greenfield’s father was an ardent Zionist who raised his youngest daughter with the belief that Israel was “essential” and central to Jewish identity. “If Israel is ever in trouble,” he told her, “you go there and you fight.” She was also told that anti-Semitism must be confronted wherever and whenever it appeared: “You don’t disappear into the woodwork; you stand up and fight when necessary. . . . My father taught me that to be a Jew meant that you held a responsibility for the Jewish people.” When another usher at the roller rink called her father a “dirty Jew” in front of Greenfield and her sister, her father responded by breaking his arm. “While that was the end of our roller-skating lessons,” said Greenfield, “it was a memorable demonstration on fighting back.” Later in middle school, when a classmate called Greenfield a “dirty kike” and pushed her into the lockers, Greenfield fought back. Although she and the girl both got suspended, her father was proud of her: there were no gender issues involved in defending herself as a Jew. Her role models were Jewish resistance fighters. “To be Jewish meant standing up in defiance. . . . I was proud to be Jewish.”40

Greenfield entered college at the State University of New York (SUNY) at Oswego in 1968, at the height of the student movement. At first, she was involved with New Left male activists in the antiwar movement and for an academic year was president of the campus Hillel chapter. But soon she developed a feminist consciousness, majoring in women’s studies and communications. She became a feminist activist, creating the radical feminist group Women for a New World, which ran a multipurpose women’s center. The group also started AWARE (the Alliance of Women Against Repression Education) at SUNY. AWARE held a statewide conference in Oswego in 1972, with Robin Morgan as the keynote speak. Morgan became Greenfield’s mentor, and the two were close for half a dozen years. Greenfield also performed in the radical feminist theater troupe We Are the Women Your Father Warned You About.

Most notorious of Greenfield’s feminist groups was the Red Rag Regime, an underground collective that went out on “payback” actions, visiting the homes of men accused of harassment or violence against women. Red Rag left its signature poster—a red woman’s fist against a purple background—along with soiled sanitary napkins or tampons, as a sign that the Regime would be watching them, as well as such other “gifts” as flattened auto tires and broken raw eggs. “The tactic . . . proves to be very effective in dealing with male politicos,” the collective wrote in a press release. “Since [the men] try to be politically hip, they tend to react defensively, apologetically, and cowardly. . . . Amazing what eggs, a nice symbol of women’s fertility, could do to change a boy’s mind.”41 The intention was not to hurt, said Greenfield, but to frighten and embarrass.

Greenfield married while she was in college, but she left the marriage after it became clear that her husband did not want children. Soon after, she made the transition from radical feminist to radical lesbian feminist. After graduating from SUNY Oswego, she moved to Boston to study the history of women at the Goddard-Cambridge Graduate Program in Social Change. Several other radical feminist collective members from Oswego relocated to Boston, and with Greenfield, they formed the Pomegranate Grove collective. When they discovered that Boston was less tolerant than Oswego about feminist graffiti, the collective redirected its energy toward productive outcomes. With other activists, Pomegranate Grove helped establish a women-only martial-arts school in Boston.

The Pomegranate Grove collective became engaged with the women’s spirituality movement, in which Robin Morgan played an important role. In a keynote address at a lesbian feminist conference in Los Angeles in 1973, Morgan helped to initiate the merging of feminist politics with women’s spirituality, identifying herself as a witch whose powers drew from the ancient art of Wicca.42 Morgan introduced Greenfield to Morgan McFarland, an Englishwoman who was building circles of Dianic healers throughout the U.S. Under McFarland’s tutelage, Greenfield trained as a Dianic priestess named Persephone, for whom the press is named.

The collective organized the first national conference on women’s spirituality, titled “Through the Looking Glass: A Gynergenetic Experience.” Held in Boston on April 24–26, 1976, the event attracted over fifteen hundred women. Dozens of feminist icons—including Mary Daly, Emily Culpepper, and Z. Budapest—led sessions on such subjects as Amazons and gynocracy, the “covenant of the goddess,” “starting covens, groups and circles,” spiritual music done in a coven (“moon jam”), and feminist theater and art. There were also discussion groups for feminist astrologers, palm readers, and tarotists.43 Persephone Press was launched at the conference, with the release of its first book, A Feminist Tarot, co-authored by Sally Gearhart and Susan Rennie.

After the conference, Pomegranate Grove reexamined its engagement in the women’s spirituality movement. It decided to focus instead on growing Persephone Press, with the goal of creating books that could serve as “organizing tools printed to promote consciousness-raising and social change.” Within half a dozen years, it had implemented its mission.44 Persephone served as an outlet for radical feminist voices at a crucial time in the movement and became one of the giants of feminist business. Most of its titles were in the forefront of lesbian feminist thought.

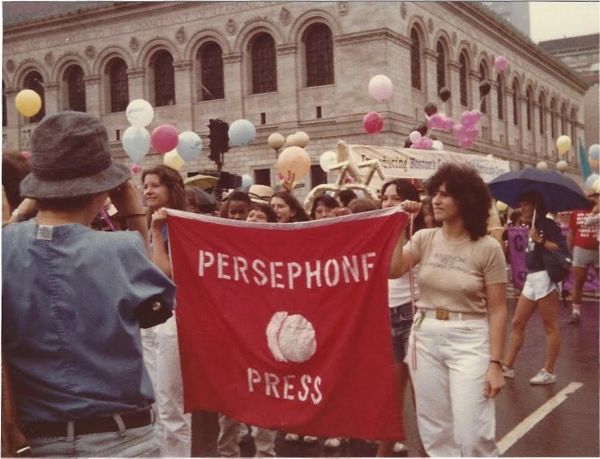

Figure 7.1. Pat McGloin and Gloria Greenfield, founders of Persephone Press, at Boston Pride March. Courtesy of Gloria Greenfield.

In Greenfield’s reflection on the eighteen months that she was involved with the women’s spirituality movement prior to starting Persephone, she explained, “I always identified myself during that period as being a Jewish woman,” but because she saw religion as the tool of patriarchy, she could not reconcile her feelings as a Jew with radical feminism. The press provided her the opportunity to engage authors who explored critical feminist issues, including race, religion, and ethnicity. “We were committed to publishing works by Jewish women and by women of color. . . . But we had a list of isms that we would not publish. We would not publish anything that was classist or racist or anti-Semitic.”45

Persephone Press developed an impressive booklist consisting of anthologies, fiction, and poetry.46 Its 1981 anthology This Bridge Called My Back: Writings by Radical Women of Color, edited by Cherríe Moraga and Gloria E. Anzaldúa, a groundbreaking collection of writings from Chicanas, black women, and Asian and Native Americans, challenged racism within radical feminism; it remains one of the most cited books of feminist theorizing. Nice Jewish Girls similarly used the anthology format to examine contested issues within feminism, exposing multiple viewpoints of grassroots activists, writers, and scholars. Like Bridge, it enjoyed a breakthrough success, becoming an organizing tool for Jewish lesbian feminists.

Greenfield had begun to feel that as Persephone Press grew, the pace of anti-Semitic incidents—some blatant, some subtle—involving authors had increased. On one occasion, a non-Jewish author reprimanded her for her love of Israel; other authors mentioned that they were concerned about her traveling to Europe for research on anti-Semitism, which they feared would take her attention away from antiracism work. She felt the sting of similar incidents.

In the summer of 1982, Greenfield decided to withdraw from Di Vilde Chayes, whose members included several Persephone authors. In a resignation letter, she explained that her decision had nothing to do with personal feelings about members. But she hoped that leaving Di Vilde Chayes would facilitate a healthier relationship between Di Vilde Chayes’ authors and herself as publisher.

Persephone Press closed within a year. One rift that contributed to its shutdown concerned a novel written by Jan Clausen, a white, non-Jewish lesbian feminist. Greenfield and McGloin were shocked at what they perceived to be anti-Semitic stereotypes in the manuscript that Clausen submitted, and they abruptly canceled her contract, a decision that angered several Persephone authors, among them several women of color. Although these authors vehemently defended Clausen, Greenfield and McGloin stood their ground.47

Financial exigencies also contributed to the press’s dissolution. Greenfield and McGloin were unable to come up with capital to print the spring 1983 list. The publishers were disappointed that authors and others in the feminist community did not rally to their support, and they felt that the sacrifices they had made to maintain the press no longer seemed worthwhile. After the press’s demise in May 1983, a few authors took back the rights to their respective books. Greenfield and McGloin placed some titles with other small presses, and Boston-based Beacon Press took over the remainder of Persephone’s list.48

Greenfield continued to speak out against anti-Semitism within the feminist movement. In July 1983, she guest edited a special issue of the feminist newsmagazine Sojourner about Jewish women. After receiving letters from Jewish women all over the country in response to her request for information about their experiences of anti-Semitism, she wrote an essay titled “The Tools of Guilt and Intimidation” for the issue. The article reported respondents’ belief that anti-Semitism was growing, as well as Greenfield’s sense that Jewish women had been complicit in silencing protests against it because of self-hate, scapegoating, or fears of confrontation.49 Jewish women did not want their reputations to suffer in the way that Greenfield’s had: she was being labeled as a “movement creep” for her outspokenness concerning anti-Jewish prejudice. “The pain kept repeating,” said Greenfield, “each time I hear of yet another Jewish woman having a nervous breakdown resulting from the movement’s response to her confronting anti-Semitism.” It was “behavior modification”: “If you don’t behave as a ‘good’ Jew (i.e., ‘good’ Jews are concerned with everyone else’s oppression at the expense of their own; ‘bad’ Jews act greedily with concern for their own oppression), then you won’t be admitted into the sorority. And your confrontation with anti-Semitism will be met with dismissing comments such as ‘oh, it’s just that loud-mouthed Jew’; or ‘here they go again, trying to dominate the issues’; or ‘she is just trying to cover up her own complicity with classism, racism, and imperialism by talking about anti-Semitism.’”50

The Sojourner issue and an address Greenfield gave on anti-Semitism in the women’s movement, in June 1983 at the San Francisco Lesbian and Gay Rally, marked her departure from radical feminism—what she called her own “goodbye to all that.” “I had decided that I needed to ‘go home,’” she explained in a statement to the Jewish Women’s Archive decades later. “I was making a conscious decision to change my primary identity from ‘Jewish radical feminist’ to ‘feminist Jew.’ I declared that for me, confronting sexism within the Jewish community would be more life-affirming and productive than continuing to fight anti-Semitism from inside of the women’s movement, which was supposed to be committed to the liberation and safeguarding of all women. It was clear to me that even though the radical feminist community claimed to have disengaged politically from the male Left, it did not purge itself of the Left’s virulent and historical anti-Semitism.”51

Greenfield never again identified with the feminist movement; being a Jew and a Zionist have remained her principal identities. She remarried in 1985; she and her husband are the parents of a daughter and two sons. After working as a senior manager in a Fortune 500 company for six years, she pursued graduate work in Jewish philosophy and since has served as a consultant to the Jewish community, a Jewish educator, an Israel advocate, and a documentary filmmaker. Her film credits include The Case for Israel: Democracy’s Outpost (2008), Unmasked Judeophobia (2011), and Body and Soul: The State of the Jewish Nation (2014). Her films have been translated into a dozen languages.

Greenfield said that she is a combatant in the wars against the hatred of Jews and the Jewish state, focusing her passion and determination on the defense of Israel and world Jewry: “I’ve always been a Zionist. And proud to be a Jew. . . . And for me being a Jew isn’t an opportunity to be one step away from being white.”52 Greenfield affirms that she is not evading her whiteness by claiming her Jewishness but adding to it, in effect answering those who deride Jewish feminists for complaining about anti-Semitism rather than focusing on racism per se. She makes no apologies for her stance, which she distinguishes from that of Jews and non-Jews who take what she considers an anti-Semitic, anti-Zionist position by criticizing Israel’s insistence on its right to defend its borders and its citizens.

Irena Klepfisz and Melanie Kaye/Kantrowitz: “Danger as the Shared Jewish Identity”

Evelyn Beck contacted Irena Klepfisz, and Gloria Greenfield reached out to Melanie Kaye/Kantrowitz, asking them to contribute to Nice Jewish Girls. The invitation to Klepfisz came because Beck knew her as a Holocaust survivor, but Klepfisz hesitated, acknowledging that her feelings as an American Jew were not “completely clear.” As a lesbian, moreover, she felt like an outsider; she considered the women’s movement homophobic, knowing many lesbians who were afraid to come out. She believed that the Jewish women’s movement was similarly unwelcoming, seeing publications such as Lilith as “mainstream” and unconcerned with lesbian issues. Her sense of herself as an American Jewish lesbian remained “tangled and interlocked.”53

Melanie Kaye/Kantrowitz, raised in Brooklyn where everyone was Jewish, also hesitated. Kaye/Kantrowitz had not thought much about her Jewish identity until she was well into her thirties. Her father had changed his family name, Kantrowitz, to Kaye, a few years before she was born (because “Kantrowitz was too long, too hard to say”), and she had grown up without a conscious connection to her heritage.54 By 1980, she began to identify herself as Jewish and reclaimed the family name—it was “like coming out.”55

Like Klepfisz, Kaye/Kantrowitz believed lesbian Jewish feminism contained elements of danger. While Klepfisz felt especially vulnerable as a lesbian in the women’s movement, Kaye/Kantrowitz emphasized her invisibility as a Jew in the non-Jewish communities in which she lived after college. Neither she nor Klepfisz identified with religious Jewish feminists. How could Jewish feminists identify religiously when Jewish patriarchal values subsumed Jewish ethics? Nor could she understand the glue that bound secular Jewish feminists together.

Though active in the feminist and lesbian movements, both Klepfisz and Kaye/Kantrowitz had silenced important parts of their composite identities, unable to bring the whole into alignment. “When you think about what it means to be Jewish,” Kaye/Kantrowitz acknowledged in a 1982 interview, “you think of persecution. The only possible escape dangled before you is to erase your being Jewish. If you could only not be who you are . . .” Klepfisz agreed: “It was very hard to deal with my self-hate as a white woman and say, ‘I’m proud to be a Jew.’ I couldn’t fit those two things together somehow.”56

The two women recognized that Beck’s anthology presented opportunities for them to claim fuller identities and to publicly declare themselves as Jewish lesbian feminists. Both decided to contribute to the anthology, and through this work and participation in the Di Vilde Chayes collective, each woman articulated Jewish lesbian experience and problematized anti-Semitism and internal oppression as issues for the lesbian feminist movement.

***

Irena Klepfisz was born in the Warsaw Ghetto in 1941. When she was two, her father, a resistance fighter, died in the Warsaw Ghetto Uprising. Klepfisz escaped with her mother to the Polish countryside, where they survived by concealing their Jewish identities; Klepfisz learned Polish in a convent where she was hidden. After the war, she and her mother lived briefly in Lodz, Poland, then emigrated to Sweden, moving to the United States in 1949, when Klepfisz was eight. Irena learned Swedish, but Polish remained the language of her family and community.

Klepfisz grew up in the Bronx, where she and her mother experienced great poverty in their first years as immigrants. As a child—the only surviving member of her father’s family—she felt “old with terror and the brutality, the haphazardness of survival.” For the survivors with whom she grew up, the Holocaust never ended: her mother stacked “shelves and shelves of food—just in case.” Klepfisz agonized over her visibility as a Jew: “over the fact that I lived in a Jewish neighborhood, . . . [that] at a moment’s notice I could be found, identified, rounded up.” Being Jewish was “dangerous, something to be hidden.” America became “a source of pain,” a place where Klepfisz was completely isolated, “different, the greenhorn, the survivor.”57

While the Holocaust remained present, Klepfisz felt robbed of a true sense of mourning because Americans “commercialized” it, “metaphored [it] out of reality,” rendering it devoid of meaning.58 There was no connection between the American Jewish world and the “yidishe shive” (Yiddish environment) of her background. “Though the students in my public school were probably 95 percent Jewish, not once . . . do I remember a single teacher—Jew or gentile—discuss a Jewish topic or issue, holiday, leader.”59

The erasure of Jewishness continued for Klepfisz at City College: “Nothing encouraged us to look to our homes and backgrounds for cultural resources worthy of preservation. The message was just the opposite: we were to erase all traces of who we were and where we came from.” Klepfisz and other students from the Bronx or Brooklyn had to take four required semesters of speech to divest them of their working-class Jewish accents. “What were we supposed to think after such lessons . . . ? Were we supposed to be proud?”60

Klepfisz chose to study American writers rather than the Jewish authors in whom she was interested, feeling it was safer, but she persuaded distinguished Yiddish linguist Max Weinrich, then teaching German at City College, to offer a Yiddish course to her and a few others. Yiddish literature, which she had been introduced to at her childhood shul, became a powerful influence, with its political vision. Yet American and English literature dominated her studies. In 1970, she received her Ph.D. in English from the University of Chicago, doing her dissertation on George Eliot. Her two worlds remained “mutually exclusive.”61

Feminism was also absent from Klepfisz’s academic life. She regretted never having had any women professors and recalled a pivotal moment when, after reading Kate Millet’s Sexual Politics in 1970, a married friend of hers became indignant, questioning why she “was the one washing the toilet.” But Klepfisz considered herself nonpolitical; the feminist activism of the Chicago Women’s Liberation Union did not touch her.62 As she became involved in the “non-Jewish environment” of lesbian feminism, the absorption of feminism into her politics transformed the socialism and yidishkayt of her youth. “Needless to say,” she wrote, “many of the feminists and lesbians I worked with were Jews; but our focus was never on Jewish issues.”63 In 1976, with Elly Bulkin, Jan Clausen, and Rima Shore, she founded the feminist-lesbian literary magazine Conditions, maintained and published by a lesbian collective.

The decision to write for Nice Jewish Girls became a milestone in the development of Klepfisz’s Jewish feminist identity: “History stepped in again. . . . The women’s movement began to take notice of Jewish issues.” Klepfisz led workshops on Jewish identity and on anti-Semitism, meeting many women who knew no Jewish history or culture. “Still, they yearned: How can I be Jewish? Is being Jewish more than just feeling Jewish? What should I study? Where should I go? Like me, many of them were not drawn to religion or ritual; they were looking for secular answers.”64

Klepfisz hoped to provide them. Although sensitive to the problem of lesbian invisibility, she recognized the necessity of bringing straight Jewish women and lesbian women together around issues of common concern, especially anti-Semitism. She acknowledged that straight women could feel disparaged and isolated at lesbian events and called on Di Vilde Chayes and other lesbians to remember their common Jewishness and create alliances among different kinds of Jewish women.65

Figure 7.2. Melanie Kaye/Kantrowitz and Irena Klepfisz at a Di Vilde Chayes gathering, 1982. Courtesy of Gloria Greenfield.

Klepfisz provided a strong voice raising consciousness on the issue of anti-Semitism. In her article “Anti-Semitism in the Lesbian/Feminist Movement,” which appeared in Womannews in 1981 as well as in the opening section of Nice Jewish Girls, she explained that anti-Semitism took more forms than “the overt, undeniably inexcusable painted swastika on a Jewish gravestone or a synagogue wall”; it was sometimes “elusive and difficult to pinpoint, for it is the anti-Semitism either of omission or one which trivializes the Jewish experience and Jewish oppression.”66 She felt it imperative to confront Jewish self-hatred as well as Gentile anti-Semitism. Having been told, “Jews are too pushy, too aggressive, . . . that they control everything,” Jewish lesbian feminists kept silent about their Jewishness, fearing to confront what threatened them. “How is such hesitancy possible among women who have passionately devoted themselves to fighting every form of oppression?” She was clear about naming the problem: “Any attempt to draw attention away from one’s Jewishness is an internalization of anti-Semitism.” Klepfisz called on Jewish and non-Jewish women to ask themselves hard questions in order to identify sources of “shame, conflict, doubt, and anti-Semitism” in themselves. “Like any other ideology of oppression,” anti-Semitism “must never be tolerated, must never be hushed up, must never be ignored. It must always be exposed and resisted.”67

Later in life, Klepfisz was able to combine the disparate worlds of her childhood, bringing together yidishkayt and American politics. In her poetry and translations of Yiddish authors, she encouraged the reclamation of secular Jewish culture. She is the author of several books of poetry and prose, including Keeper of Accounts, published by Persephone Press, as well as of A Few Words in the Mother Tongue: Poems Selected and New, 1971–1990 and Dreams of an Insomniac: Jewish Feminist Essays and Diatribes, and she has translated the works of Kadya Molodowsky and other women Yiddish poets.68 She also taught women’s studies at Barnard College, specializing in the history and literature of Jewish women.

***

While the Holocaust was the single most important event in Klepfisz’s identity, it did not play a large role in shaping Melanie Kaye/Kantrowitz, although she had relatives who perished in the concentration camps. The civil rights movement and the antiauthoritarian values of her parents were much more significant in motivating Kaye/Kantrowitz’s activism.

Kantrowitz was born in 1945 in the Flatbush section of Brooklyn, where “everyone,” or almost everyone, was Jewish. “Jewish was the air I breathed, . . . everything I took for granted.” But, she said, it was “nothing I articulated.”69 She did not flaunt her Jewishness. “Sometime around ninth grade,” she wrote in her essay for Beck’s anthology, “words like yenta shmatte bubbe began to embarrass me. . . . [They] marked, stripped, and revealed me. I came from people who talked like that,” including parents who had a “six-days-plus-two-nights-work-week” in “the store,” selling bras and girdles. “I came from them and would be stuck with their lives.” Being Jewish meant “being lower class”; getting an education “meant moving up in the world and no longer being Jewish.” She wanted to aim higher—“museums, foreign films, and an escape from Brooklyn.”70

Yet despite the lower-class accents and aspirations that characterized the Brooklyn Jews Kaye/Kantrowitz knew, she respected her parents’ values. While not political activists, both “had definite opinions about right and wrong,” which they passed on to her, such as “the Ten Commandments.” Her father joined the Young Communist League as a teenager during the Depression; though he did not consider himself political, he was definitely left leaning. Kaye/Kantrowitz’s mother, who circulated petitions against the Korean War and strongly opposed McCarthyism, was an even greater influence. As PTA president of Melanie’s junior high school, she fought to bring blacklisted performers to the annual PTA meeting. Kaye/Kantrowitz’s favorite story was how her mother stood up for her, when during a shelter drill in her kindergarten class, the young girl frightened her classmates by telling them that the drill was “not a game,” as the teacher said, but intended to protect them from bombs that “burned and killed” people. When the principal scolded her mother for discussing these facts with a girl so young, her mother insisted that she could not lie, defending her daughter as “class conscience and rebel.”71

Kaye/Kantrowitz appreciated her parents as models. “I have yet to find [them] wanting,” she said. “This was my Jewish upbringing as much as the candles we lit for Hanukah, or the seders.” Her family was not observant. To them, “breaking religious observance was progressive, the opposite of superstitious”: “When we ate on Yom Kippur, it never occurred to me that this was un-Jewish. I knew I was a Jew. I knew Hitler had been evil. I knew Negroes—we said then—had been slaves and that was evil too. I knew prejudice was wrong, stupid. I knew Jews believed in freedom and justice.”72 But she did not yet view her parents’ ethics, and her own rapidly forming ones, as Jewish.

In 1963, at age seventeen, Kaye/Kantrowitz went to work for the Harlem Education Project, tutoring African American students and participating in creating freedom schools and other actions to help the neighborhood. The experience was formative. She became “intensely focused on white racism, utterly unaware of racism against Jews, or of the possibility of Jewish danger (the Holocaust was eons ago, irrelevant).” It was years before she understood how her upbringing had “primed” her for this commitment.73 At the time, she felt that her “being Jewish had nothing to do with it.” “Being Jewish meant being white,” an identity that she thought she might escape through her naïve, “unexamined empathy with oppression.” In Harlem, as a teenager, she thought she could elude the world of her upbringing: “Flatbush, my parents’ clothing store, the world of working- and lower-middle-class Jews, a world I thought of as materialistic.” She was the kind of Jew, she said, “who didn’t feel afraid, ashamed, joyful, grieving, according to the fate and/or behavior of Jews. Who didn’t see Jews as ‘my people.’”74

After graduating from City College, Kaye/Kantrowitz left New York to do graduate work at the University of California at Berkeley, wanting to get away from her family, her people, “to be part of the radical politics developing on the West Coast.” Being a Jew at Berkeley had little resonance, although she was surprised that the Brooklyn-Jewish accent that once designated her as “lower class” now marked her “as one of those smart Jews from New York.” Involved in the antiwar and student movements, she was not moved by Jewish political issues and did not notice the 1967 Middle East war or identify with Israel. Like Eva in Tillie Olsen’s Tell Me a Riddle, Kaye/Kantrowitz marked “none” next to religion on a questionnaire she filled out at that time.75

Kaye/Kantrowitz also resisted identifying as a Jew within the feminist movement. At a feminist conference in Portland, Oregon, where she moved in 1972, a woman told her that she did not like Jews who were “loud and pushy and aggressive.” Stunned, Kaye/Kantrowitz revealed that she was Jewish. In 1975, at the National Conference on Socialist Feminism in Yellow Springs, Ohio, she avoided the opportunity to attend the Jewish caucus called by Susan Schechter and Maralee Gordon. “I couldn’t relate to it. I went to a workshop on economics instead.”76 Later she would understand what she did not see then: “that however I thought about or related to my identity and my history, I could no more walk free of these than I could be genderless.”77

For seven years in Portland, Kaye/Kantrowitz felt like an “alien” in a “wrong city, the wrong part of the world.” She rejected religious Jews and the Jewish women who met Friday nights to “schmooze.” Later she understood her hesitancy as the way “the mind resists threatening information.”78 But slowly she began to develop a Jewish consciousness, manifesting itself in an interest in Jewish immigrant history and the Holocaust.

Kaye/Kantrowitz moved to New Mexico for a teaching job in 1979; there her “close people” were “almost all lesbians, mostly not Jewish.” Her acceptance of Jewishness grew. “The more outside of a Jewish ambiance I was, the more conscious I became of Jewishness.” Recognizing how much she needed Jews, Kaye/Kantrowitz began to find Jewish women everywhere. “So Melanie, what’s with all the Jewish?” her father asked her in 1982, the year Nice Jewish Girls was published. By then, she was fully aware of her hunger for what she described as “home, kin, for my people,” and of growing anti-Semitism. Decades later would she understand that her previous “rebellion had been enacted simultaneously by thousands of young Jews; that it was in fact a collective Jewish rebellion, articulated in a classically Jewish fashion.”79

Like Klepfisz, Kaye/Kantrowitz continued to work on issues of anti-Semitism and racism, combining political activism with writing and teaching. In addition to The Tribe of Dina: A Jewish Women’s Anthology, which she co-edited with Klepfisz, her books include My Jewish Face & Other Stories; The Issue Is Power: Essays on Women, Jews, Violence, and Resistance; and The Colors of Jews: Racial Politics and Radical Diasporism. She taught urban studies at Queens College, where she directed the Worker Education Extension Center, and has worked with New Jewish Agenda and Jews for Racial and Economic Justice.

At the NYU “Women’s Liberation and Jewish Identity” conference, Kaye/Kantrowitz distinguished between “minimalist” Jews and “non-Jewish Jews,” aligning herself with the latter, whom she sees as “boundary crossers” and “rebels,” transcending a narrow, constricting Jewishness but belonging to Jewish tradition.80 She prefers the term “Diasporists” for people such as herself who recognize Jewish “identity as simultaneously rock, forged under centuries of pressure, and water, infinitely flexible.”81

Adrienne Rich: “Dear Schvesters”

Irena Klepfisz took the initiative in assembling a group of women interested in meeting to discuss topics of concern to Jewish lesbian feminists. Most had become visible to each other while working on articles for Nice Jewish Girls or other lesbian and feminist publications.82 Klepfisz suggested the group’s purpose in an early letter: to do “political work around anti-Semitism in the movement, and to focus and try to understand Jewish–Third world relations in the movement and outside.” After exploring the idea with Beck, Kaye/Kantrowitz, and Bernice Mennis, she contacted Gloria Greenfield, Adrienne Rich, and Nancy Bereano, who agreed to join the new group. They called themselves “Di Vilde Chayes,” a name that Beck’s mother called her when she looked unkempt or acted inappropriately for a girl, like a “wild beast.”83 In an interview at the time, Klepfisz and Kaye/Kantrowitz acknowledged that in books such as This Bridge Called My Back, “women of color laid the groundwork” for bringing cultural differences to the forefront of the feminist movement, inspiring Jewish women to explore such topics as anti-Semitism and internal oppression.84

Like the early women’s liberationists collectives and the newer groups organized by women of color, Di Vilde Chayes aimed to combine consciousness-raising with action. In an unpublished piece, members explained the feelings that led them to join together: “[to] understand what was going on inside ourselves and in the outside world; and based on that understanding, to act in that outside world. The group was a way out of our individual and isolated powerless howlings. . . . It was a way of taking our personal understandings and developing a political vision.”85

The women had been aware that issues involving Jewish identity and anti-Semitism had been missing from political analysis, but by themselves, they were isolated and afraid, choked by “the fear that had something to do with self-preservation, with not betraying one’s past or one’s family or one’s self.” Joining together empowered them, creating “joy at the awakening of one’s proud Jewish identity.” The group was a way to explore the women’s “individual Jewish histories”: “our incorporation of myths and stereotypes; a way of unraveling the often unconscious layers of harm and damage that prejudice and oppression create.”86

Di Vilde Chayes’ political vision was “informed by Jewishness in its very framework”: “our Jewishness as our feminism, becoming a way of viewing, a new lens through which to see ourselves and the world around us.” They hoped that the retrieval of Jewish heritage could spur collective action. Yet they recognized a negative commonality they shared with women’s liberationists. “With feminism, and now with Jewishness, the beginning of self-definition and assertion are often met with laughter and trivialization, criticism, and/or anger, as if in defining ourselves we are ruining a happy family, dividing a united front.”87 They expected consciousness-raising and political action as Jewish lesbian feminists to be difficult. To persist would require support from both Jewish and non-Jewish friends.

As Di Vilde Chayes began its meetings in February, Adrienne Rich outlined her goals for the group: “Dear Schvesters: Thinking about what a Jewish Lesbian group/cell/collective/study group/action group/network or combination of these, might be. . . . I want to be part . . . of a Jewish/lesbian/feminist group which can develop an analysis of anti-Semitism and Jewish identity for ourselves and for the feminist movement and which will also relentlessly keep this in with what we already understand of racism, class injustice woman-hating, homophobia.”88

Rich felt that she had a lot of work to do “simply to feel and understand” both her “existence and oppression as a Jew.” When Beck invited her to contribute to Nice Jewish Girls, she at first declined, but after thinking over the issues for a year, Rich wrote “Split at the Root” for the anthology.89 The essay spoke of the profound difficulties of focusing on different oppressions at the same time. “Sometimes I feel I have seen too long from too many disconnected angles,” Rich wrote memorably in the now-classic essay, “white, Jewish, anti-Semite, racist, anti-racist, once-married lesbian, middle-class, feminist, exmatriate Southerner, split at the root: that I will never bring them whole.”90

The daughter of an assimilated Jewish father and Gentile mother, both from the South, Rich grew up in a Christian world, shaped by external anti-Semitism, her father’s self-hatred, and his “Jewish pride.” She married a Harvard man who was from eastern European stock—the “wrong kind of Jew”—and she never felt Jewish pride as writer, wife, or mother.91 While the civil rights movement felt deeply personal to her, “in the world of Jewish assimilationist and liberal politics . . . things were far less clear. . . . Anti-Semitism went almost unmentioned. It was even possible to view anti-Semitism as a reactionary agenda, a concern of Commentary magazine, or later, the Jewish Defense League.” Although Judaism was “yet another strand of patriarchy,” she always added mentally, “if Jews had to wear yellow stars again, I too would wear one.”92

Rich’s sitting down to write about herself as a Jew seemed a “dangerous act” that filled her with “fear and shame.” Her essay had “no conclusions”: “I would have liked, in this essay, to bring together the meanings of anti-Semitism and racism as I have experienced them and as I believe they intersect in the world beyond my life. But I’m not able to do this yet. I feel the tension as I think, make notes: if you really look at one reality, the other will waver and disperse.”93

Di Vilde Chayes’ formation offered “another beginning,” analogous to the founding moments of radical feminism. “In some ways this feels to me like the early 1970s when we were rushing about searching for the lost, out-of-print, hard-to-come-by information we needed,” she wrote to her Di Vilde Chayes sisters, “the books gathering dust in libraries, the history we didn’t know. We exchange bibliographies, follow off leads in other bibliographies. We start trying to name what is happening. We make lists . . . of Jewish women fiction writers in America and are shocked at how few we find. We start . . . reversing stereotypes, claiming our strengths. At the same time, within the very movement where this is happening, we have to confront unexamined bigotry, old Leftist attitudes, etc.” Given the historical exigencies of the times and the coming together of Di Vilde Chayes, along with work done by other Nice Jewish Girls contributors, Rich felt that her own perspectives were “changing, opening out.” “I am glad that each of you exists,” she told the Schvesters.94

A few months after the founding of Di Vilde Chayes, Klepfisz and Kaye/Kantrowitz attended a Memorial Day Jewish Feminist Conference in San Francisco, representing the group. Drawing nearly one thousand women, including some two hundred non-Jews, the conference drew attention to Jewish issues within the feminist community. The large number of attendees allowed Jewish women to connect to their own identities while continuing to see themselves a part of a broader community. Reporting to Di Vilde Chayes, Klepfisz and Kaye/Kantrowitz described their “overwhelming feeling of joy” at being “out” as Jews at the event. “You did not have to worry about being ‘too’ Jewish, about feeding into Jewish stereotypes, about taking up too much space, too much time, too much energy by asking others to focus on your ‘selfish’ Jewish concerns. You did not have to worry about being ‘paranoid’ when describing anti-Semitic experiences and situations. About being ‘clannish’ for feeling glad and excited at connecting with other Jewish women.”95 Yet despite their euphoria, Klepfisz and Kaye/Kantrowitz observed with concern that when it came to the Israel issue, conference goers were deeply divided, with each side expressing “visceral antagonism” toward the other.96

Figure 7.3. Jewish lesbians at Women’s Pentagon Action, November 1981. Photo © 2017 JEB (Joan E. Biren).

“We Had Not Planned to Be a Group Focused Only on Israel”

The conflict among feminists over Israel was reflected in Di Vilde Chayes’ war of words with Women Against Imperialism (WAI), a San Francisco anti-imperialist group. In a pamphlet in the spring of 1982, WAI called on “Progressive Jewish women” to oppose “Zionist Israel . . . one of imperialism’s most important bastions of white supremacy.”97 A WAI letter to the women’s movement at about the same time declared that opposing Zionism was an inherent component of the fight against worldwide imperialism. “We as women do not confront some separate structure of oppression, but the same imperialist system whose bedrock is the oppression of colonized nations inside the US and around the world. If we want to participate in fundamentally changing this system, to be part of building a society where genocide, women’s oppression, anti-semitism and class exploitation can no longer exist, then we need to actively side with Palestinian, Black, Chicano-Mexicano, Puerto Rican, Native American and all national liberation struggles which are leading the fight to take this empire apart.”98 Troubled by the Jewish Feminist Conference that Klepfisz and Kaye/Kantrowitz attended in San Francisco, WAI asked, “What does it mean that a thousand Jewish women can gather and not condemn Zionism?” Not to break with Zionism meant “sacrificing our principles and allowing a racist politics to gain ground in our movement for women’s and lesbian liberation.”99

In a letter printed in off our backs in spring/summer 1982, Di Vilde Chayes rejected WAI’s charge that “Zionism is racism.” While it disapproved of the Israeli government’s occupation policies, Di Vilde Chayes wrote that none of its criticisms denied Israel’s right to exist. Rather, it asserted, “Zionism is one strategy against anti-Semitism and for Jewish survival.” Because anti-Zionism demanded the “dissolution of the State of Israel,” which it believed would require the destruction of Jews within Israel and the removal of a refuge for Jews suffering persecution elsewhere, Di Vilde Chayes argued that it would lead to an increase of anti-Semitism throughout the world. “Anti-Zionism is anti-Semitism.” To state that it is “not as serious as other oppressions is to imply that Jews have no right to complain until we are marched to the gas chamber.”100

Further disagreements came when Israel invaded southern Lebanon to destroy a Palestinian guerrilla force in early June, setting off the first Israel-Lebanon war. Following the attempted assassination of the Israeli ambassador in London, Israel attacked PLO targets in Lebanon and sent ground troops into Lebanon in a mission named “Operation Peace for the Galilee.” In an attempt to root out the militants, Christian Phalangists who were Israel’s Lebanese allies murdered between seven hundred and two thousand Palestinian and Lebanese civilians in the refugee camps of Sabra and Shatila, suspected of being PLO strongholds. The massacres received worldwide condemnation, including protests by millions of Israelis who demonstrated against the war and the Israeli generals believed to have enabled the killings.

Labeling the war a “genocide against the Arab peoples of Palestine and Lebanon,” WAI called on the women’s movement to join the condemnation of the war and further challenge Israel’s right to exist. In a letter printed in feminist outlets in the fall, Di Vilde Chayes called the Lebanon war a “terrible event” and criticized Israel’s bombing of civilian installations. But it rejected WAI’s characterizations of Israel as “the new Nazi state, and of the invasion as the worst thing any nation had ever done,” allegations that scapegoated Israel for the horrors in Lebanon and “for all crimes of imperialism.” Such protests falsely presented Israeli policy as monolithic, omitting the historical context of the war, and contributed to an intense climate of anti-Semitism. Di Vilde Chayes members insisted that they could not choose one part of their identity “at the expense of another as if they are . . . mutually exclusive,” as in the past they had been forced to choose between “lesbian and Jew, Jew and anti-racist, anti-racist and Zionist.” They claimed their “right as Zionists to condemn Israel aggression in Beirut,” and at the same time, they claimed their “right as Jews to confront and resist all forms of anti-Semitism which exploits criticism of current Israeli policy.”101

off our backs published pages of letters about the exchanges between Di Vilde Chayes and Women Against Imperialism. Some writers praised Di Vilde Chayes, condemning WAI’s statements as anti-Semitic and criticizing off our backs for printing them. Other correspondents, such as noted biologist Ruth Hubbard, denied Di Vilde Chayes’ claim that anti-Zionism was racism. Several feminists wrote to oppose the either/or choice that the groups offered. The controversy escalated.102

Irena Klepfisz noted that issues had “quickly . . . evolved, unraveled, and developed”; by the early 1980s, questions about Israel began to overwhelm other women’s movement concerns.103 In an unpublished account, Di Vilde Chayes acknowledged, “We had not planned to be a group focused only on Israel. We are Diaspora Jews whose lives center on this continent. But events forced our hand.”104 “I did not know how to switch my focus away from anti-Semitism, from the wounds of the Holocaust, from my work on strengthening Jewish identity,” Klepfisz admitted. “Israel has taken over my life.”105 Only later, on a trip to Israel that Klepfisz took with Kaye/Kantrowitz in 1984–1985 to find material for their anthology The Tribe of Dina, did Klepfisz find a more comfortable political space, convinced that it was possible to be “strongly Jewish identified, to believe in the necessity of the State of Israel, and to fight for Palestinian rights.”106 By 1984, Adrienne Rich had also become a strong supporter of Palestinian liberation, questioning Zionism. By that time, Gloria Greenfield had left radical feminism behind, despairing of its willingness to support Israel and confront anti-Semitism and anti-Zionism.

In Klepfisz’s view, “confusion and ignorance” about Israel influenced the decision to suspend Di Vilde Chayes. Some members believed that lacking the sophistication to deal with the complex Middle East situation, it would be better to become informed on their own. There were other considerations. Living in different areas made it difficult for members to meet, especially after Rich moved to the West Coast, while competing professional priorities grew more troublesome. Di Vilde Chayes disbanded in 1983.107 But the women’s explorations together had strengthened links to the Jewish aspects of their experience and bolstered their aspirations to claim a place for Jewish feminism in “multiracial feminist identity politics,” in Rich’s words.108

Jewish and Black Women Confront Racism and Anti-Semitism

Lesbian feminists played a significant role in opening dialogues between Jewish women and non-Jewish women as the intensification of identity politics strained longtime alliances. As the radical feminist coalition of the early movement fragmented, black and Jewish women, who had often found themselves working for the same causes, brought accusations of anti-Semitism and racism against each other. Yet they attempted to understand each other’s perspectives and experiences.

In 1983, Elly Bulkin invited Barbara Smith and Minnie Bruce Pratt, a black non-Jewish woman and a white non-Jewish woman who were also both lesbian feminists, to join her in engaging the topics of racism and anti-Semitism in print, an idea that had developed out of the rancorous plenary session on anti-Semitism and racism that took place at the 1983 NWSA conference that had so traumatized Evelyn Torton Beck. Bulkin, Smith, and Pratt’s collaboration resulted in the 1984 publication Yours in Struggle: Three Feminist Perspectives on Anti-Semitism and Racism.109 Sections of the book were excerpted in major feminist publications, and it received much attention within the movement.110

Minnie Bruce Pratt’s essay, the shortest in the volume, described the author’s childhood as a white southerner who did not understand the dynamics of white privilege and was totally ignorant of anti-Semitism.111 The major confrontation in the book was between Barbara Smith and Elly Bulkin. The women agreed that while the impact of prejudice and oppression had often made blacks and Jews “practical and ideological allies,” relationships between them had been increasingly marked by “contradictory and ambivalent feelings, both negative and positive, distrust simultaneously mixed with a desire for acceptance; and deep resentment and heavy expectations about the other group’s behavior.”112

Smith’s chapter, “Between a Rock and a Hard Place: Relationships between Black and Jewish Women,” acknowledged that addressing anti-Semitism set her up to look like a “woman of color overly concerned about ‘white’ issues.” She confessed that her experiences with Jewish women had been “terrorizing” and admitted that she was anti-Semitic, largely because she had been brought up to be suspicious of whites. But Smith charged that in Jewish women’s efforts to combat anti-Semitism, they had exercised racism toward black women. She urged black women to understand that they shared commonalities with Jewish women, included being oppressed by the white majority.113

Bulkin viewed her essay primarily as a “dialogue among Jewish women” rather than an attempt to persuade black women of her positions. It began with an account of her personal history: she was an Ashkenazi Jew, daughter of an immigrant father and New York–born mother, raised in the Bronx with an early exposure to the Jewish radical tradition. Drawn to antiracist work, Bulkin made no “analogous commitment to fighting Jewish oppression”; she associated her antiracist activism with her “lack of a strong Jewish identity.” By the late 1970s, she realized that she did not have to choose between political affinities but could work against anti-Semitism and racism simultaneously.114