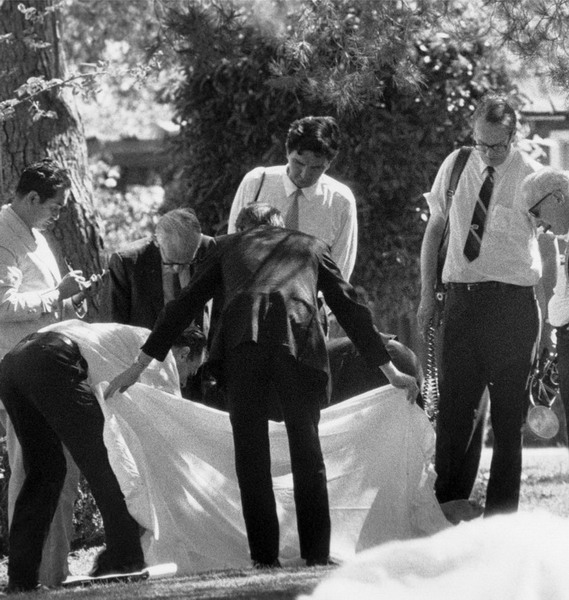

First to the scene: it is the coroner's job to make the preliminary appraisal as to the probable cause of death

The body of a murder victim, or of an individual who has died in suspicious circumstances, is a crime scene in itself. A pathologist is called in to carry out an autopsy to determine the time and cause of death from a number of vital clues which are described in detail in the following pages. But there is more to the pathologist's role than merely performing autopsies. With their anatomical expertise and experience, they can play an active part in an investigation determining whether a death is due to natural causes, the result of an accident or was intentional – whether it was suicide or homicide.

The coroner, or medical examiner, is often a police doctor or an official with medical knowledge who attends the crime scene to make a preliminary appraisal as to the likely cause of death. The coroner is responsible for issuing the death certificate and ensuring that the manner of the deceased's passing is properly recorded. If the cause of death is manslaughter, murder or suspicious in any way, it is the job of the coroner to call in a pathologist who will carry out a postmortem examination, or autopsy, to determine the exact cause of death (see here).

Pathologists only attend crime scenes when there has been a major incident they need to examine in person in order to understand the contributing factors to the particular injuries sustained by the victims. Coroners rarely become actively involved in an investigation, although in certain American states they may choose to do so if they are suitably qualified.

It is the coroner who will check for vital signs before pronouncing death by taking the pulse, listening for a heartbeat or seeing if blood is still circulating in the veins of the eyeball. Once this is done, there may be a need to strip the body of clues. For example, if there is ligature or bindings, these must be cut away without destroying the knots as the knot itself could be a signature of the killer or may provide a link to other crimes where victims were tied with the same knots or material.

When the coroner has finished the initial cursory examination and the photographer has recorded the position and location of the body, the scene of crime officer will cover the head, hands and feet of the corpse with clear polythene bags secured with tape. The body is then wrapped in a sheet, zipped into a body bag and taken to the morgue where it can be subjected to a thorough examination by a pathologist. Body bags are usually white, not black like those used in fictional TV series, as it is easier to see hairs and fibres against a white background.

If the amount of blood around the body is not consistent with the wound it is a sure sign that this is almost certainly not the primary crime scene and that there may be trace evidence in the suspect's vehicle if the corpse was transported from the primary scene to the present location. In this instance the coroner would have grounds for obtaining a search warrant for the suspect's home, place of business and vehicle in the expectation of securing vital physical trace evidence before it can be eradicated or contaminated.

DETERMINING TIME OF DEATH

Determining the time of death was once thought to be a vital element in a murder investigation, but it is very difficult to give an accurate estimate as body temperature and rigor mortis can be affected by several factors. The average corpse cools down by approximately one degree centigrade every hour but body mass, clothing and room temperature can affect this quite dramatically. A rectal thermometer reading is the most accurate method of recording core body temperature, but even this is prone to inaccuracy. Prescribed medication and narcotics can both affect circulation, which may lower body temperature, while the exertion involved in fending off an attacker or being pursued on foot for even a few minutes can bring on premature rigor mortis. Age is another factor. Elderly people and children often exhibit minimal signs of the tell-tale stiffening of the limbs, which can be broken by even the gentlest movement such as when a doctor might check for a pulse. Consequently, many coroners determine the time of death as being between the last time the person was seen alive and when their body was discovered.

Rigor mortis, a stiffening of the joints and muscles, usually sets in between 30 minutes and three hours after death, beginning with the eyelids and jaw. It affects the whole body in 6–12 hours, remains for a similar period unless it is disturbed and then dissipates over a similar period. Two days after death, bacteria in the lower abdomen will spread throughout the body to bring a green cast to the skin, except in those who are uncommonly dark-skinned. Within a week the skin turns pale white with heavily pronounced veins, giving the corpse a translucent marbled appearance.

First to the scene: it is the coroner's job to make the preliminary appraisal as to the probable cause of death

Within a week of death, the skin starts to turn white and the veins become particularly pronounced

Another clue to time of death is lividity, or ligor mortis, a pinkness of the skin created when the blood settles after the heart fails and circulation stops. Lividity usually takes six hours to take full effect, and occurs on the body where it would naturally occur if a body remains undisturbed. So if a body is found lying on its back with a strong pink hue over the torso, it suggests the deceased was turned or moved to their present location after death.

FURTHER CLUES

The condition of the eyes is another standard determinate as death brings a fall in pressure of the fluid inside the eyeballs, which causes them to soften. After this a thin cloudy film develops in under three hours if the eyes are open, but longer if they are closed.

The chemical consistency of the body also changes after death, giving forensic investigators another variable to add to the equation. The potassium level in the eye increases substantially after death, creating a clear jelly-like substance in the eye socket known as vitreous humour. Biochemical testing of this substance back at the laboratory can provide a fairly reliable estimate for the time of death.

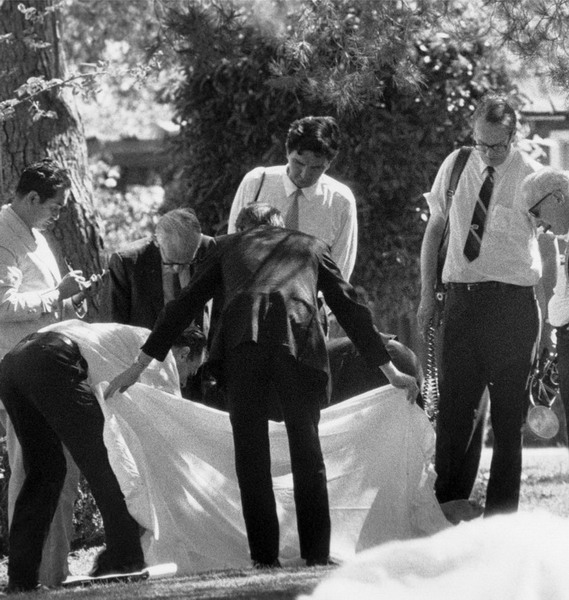

If a corpse has been left to decompose for several weeks there may be work for an entomologist, whose knowledge of bugs can narrow the time of death down to within a day or two as insect infestation follows a predictable pattern (see 'Betrayed by Bugs' below).

Another fair indicator is provided by the stomach contents, which are examined during the autopsy as digestion can help to narrow the time frame as well as revealing what, if anything, the deceased ate in the last 24 hours of their life. Food normally remains in the stomach for up to three hours before passing into the small intestine, a narrow twisting tube through which it can take up to five hours to travel. So, if the small intestine is empty, it suggests that the deceased had not eaten for approximately eight hours, and if it is partially empty then it is likely that the deceased ate more than six hours prior to their death.

Even so, the pathologist must make allowances for other factors which can affect the rate of digestion such as anxiety, illness, alcohol and drugs, which can be factored into the equation once tissue and body fluid samples have been analyzed by a toxicologist.

Sadist and sociopath Alton Coleman carried out a series of brutal rapes and armed robberies across five states during the 1980s with the arrogance of a man who knew that even if he was captured he was unlikely to be convicted. The reason for his unshakeable confidence was that Alton could always rely on his retarded girlfriend, Debra Brown, to provide him with the perfect alibi. So when he was arrested yet again in July 1984, this time for the murder of nine-year-old Vernita Wheat, FBI investigators knew that they would have to provide incontrovertible proof that he was at the scene of the crime and not, as he would claim, with Brown.

Alton's fingerprints were recovered from the door of a derelict building in which Vernita's body had been found, but Alton could argue that he had been there on an earlier occasion before the body had been dumped. The FBI knew that they needed to place him at the scene precisely on the day of her death. The girl's body was too badly decomposed to contain any of the perpetrator's DNA, but the insects and larvae which had infested the corpse might provide a precise date for her murder.

Forensic entomologist Bernard Greenberg collected bluebottle cocoons which had been found at the scene and monitored their gestation process in his laboratory, having first collated 70 weather reports for the region to ensure that he could re-create the exact conditions the insects would have in Illinois at that time of the year. Normally bluebottles take 33 days to gestate from egg to adult at 15°C (59°F), but in Illinois in June the average daytime temperature rises to 25°C (77°F) which would have speeded up the life-cycle.

When the grubs hatched a month after the body had been discovered Greenberg was able to calculate the date the eggs had been laid to the early morning of 31 May, two days after Vernita had been seen leaving her home with Alton. Alton was tried, convicted and sentenced to death, but in a bizarre twist he was extradited and executed in another state for a different, unrelated murder.

Forensic entomology: bugs can be very helpful in narrowing down the time of death

Most autopsy suites are functional, clinically sterile storage facilities which are usually situated in the basement of the local hospital with exposed pipes in the ceiling and a tiled floor for easy mopping up. There is a palpable chill in the air which is not entirely to do with the presence of death, but more to do with the need to maintain a temperature of 3°C (38°F) to slow down decomposition and arrest bacterial growth. But its most distinctive feature is the smell. It is one part preservative, two parts bleach and three parts putrescence. It can be strong enough to cause a medical student to pass out and is guaranteed to cling to your hair and clothes so that your family and friends will know where you've been.

If there are non-medical personnel present at an autopsy they will probably be grateful of the offer of a mask, but the coroner and his or her assistant will know that the odour can contain vital clues such as the faint scent of bitter almonds peculiar to strychnine poisoning and the sweet smell of ethanol, redolent of alcohol. The presence of liquor is particularly important to detect at an early stage of the investigation since, for example, intoxication is responsible for about 40 per cent of unnatural deaths in the US every year and it is not always detectable in the blood.

Most autopsy suites are functional and clinically sterile

The smell of preservative, cleaning fluid and decay becomes stifling when the air conditioning is turned off during the trace evidence collection stage, but it is vital that no hairs or fibres are lost in the cooling air stream.

If the pathologist finds any potentially significant objects on the body, such as a piece of cotton wool stuck to a sock, he or she might ask the attending police officers to radio their colleagues back at the crime scene to see if more of that material was in the vicinity when the body was found. If not, it may have been left behind by the perpetrator, or may have come from their vehicle if the body had been transported from the primary location. This is because forensic science is based on a scientific law known as Locard's Exchange Principle which, simply put, states that, when two objects come into contact, there is an exchange of material. It is often microscopic and can occur when a person is struck by a vehicle or when two people are involved in a physical altercation. All the criminalist has to do is identify what was brought to the scene by the perpetrator and what they took from the scene or the deceased which will tie them to the crime.

Autopsies are compulsory in cases of unnatural death (that is, accident, suicide and homicide) or where the death is suspicious and 'unattended', meaning those where no qualified medical professionals were present to confirm the cause of death. Not all follow the procedure described here. A coroner may decide that only a partial or selective examination is needed in certain cases where the fatal injury is clearly evident (such as a gunshot wound or when confirmation of a previously documented disease or disorder is needed). In a partial autopsy the pathologist will examine the wound, whereas in a selective examination they will study a specific internal organ such as the heart or brain. The average autopsy takes an hour or two, but in more complex cases they can take days.

The body identified: an autopsy is compulsory in cases of unnatural death or where the death is suspicious

THE FIRST STAGES

Before the examination can begin the body must be photographed and undressed, with each layer of clothing being recorded by the photographer. If there is any significant trace evidence on the clothes or the corpse, this will be collected and catalogued by an attending CSI. If there is suspicion of sexual assault, the pathologist might scan the clothes and the body with an ultraviolet Woods Light to detect semen, which will appear as a purple-white glow.

The photographer will take shots of the body from all angles, paying particular attention to tattoos (see here), distinguishing birthmarks, bruises, scars and wounds. He or she stays during the examination and records each significant stage on film. Each wound is measured and photographed against a grey forensic ruler which acts as a colour code to ensure that the photographs are developed with accurate natural colours as the colour of wounds and bruises is a reliable indicator of when the injury occurred.

A laboratory technician will then take swabs from the mouth, rectum and sexual organs as well as samples of hair for DNA analysis to aid identification if it is in question, but also to test for trace elements of drugs and poisons. Scrapings from under the fingernails might also be preserved if the deceased was a victim of an assault and then the hands are swabbed for gunpowder residue if appropriate and the deceased's fingerprints are taken, although this can be difficult if the body is in an advanced state of decomposition. Even in the recently deceased the veins in the hands protrude, making fingerprinting awkward. The top layer of skin may also be exhibiting slippage (slackening) and can peel away if not handled with care.

The body is then washed and replaced on the metallic dissection table which is perforated with drainage holes and has a surrounding ridge to retain body fluids. A second tier acts as a basin, catching all fluids which are continually rinsed away by a pump. A hanging scale at the foot of the table is used for weighing individual organs, after which they are placed on a small steel side table with a corkboard cutting block for dissection. Nearby there will be a selection of sample jars filled with formalin preservative and a range of formidable-looking dissecting tools which bear little resemblance to the small precision surgical implements used in the operating theatres on the upper floors.

The body bag and clothing are then packed, labelled and sent for further analysis.

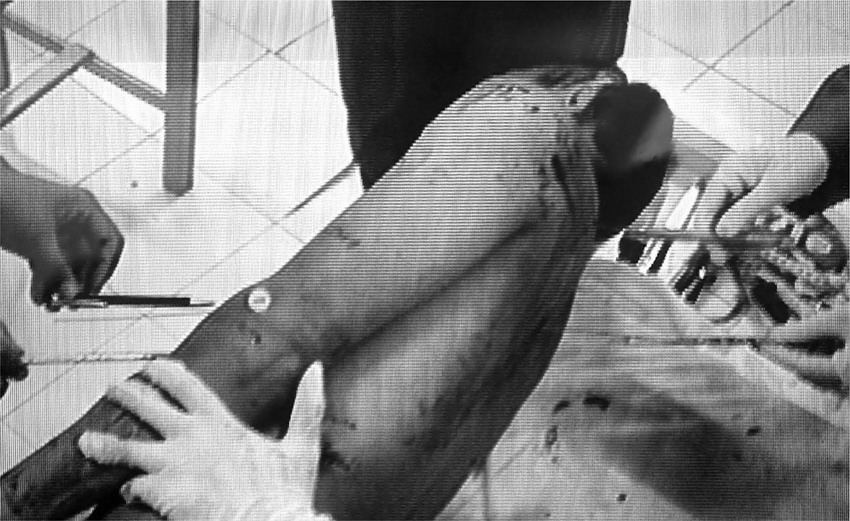

If there are knife or bullet wounds the pathologist will trace their trajectory with dowelling rods and record the results. He or she may also take X-rays of any wounds, because once the autopsy has been completed the body can be released for burial, although in very unusual cases it may be disinterred at a later date or subjected to a second autopsy if the first proves inconclusive, as in the case of the mysterious death of millionaire Robert Maxwell (see here).

The pathologist begins the internal examination by dissecting the torso from shoulder to shoulder and down to the abdomen with what is known as a 'Y' incision to expose the organs. Using bone cutters, he or she cuts through the ribs and removes the chest plate, followed by the heart, lungs, trachea and oesophagus. Samples of tissue and fluid from these organs are taken and stored in a refrigerator for later analysis. Next, the abdominal organs are removed and the stomach contents systematically examined. Again, samples are bottled, labelled and stored in the refrigerator for future analysis.

Forensic doctors examine the body of a slain bomb-maker in Indonesia

Exit wound: the direction of a bullet can be determined at the autopsy

Finally, an incision is made at the back of the head from ear to ear and the skin is peeled back, exposing the skull.

Using a stainless steel saw and cranium chisel, the skull is opened and the brain removed for weighing and for tissue samples to be taken.

ANALYZING THE WOUNDS

In cases of murder, manslaughter, suspected suicide or fatal accident, the primary crime scene is the body itself. Each wound, burn, bruise and abrasion can reveal how the deceased met their death, what weapon, if any, was used and ultimately, who was responsible.

A gun fired at extremely close range, for example, will leave a burn surrounding the wound suggesting suicide, a professional hit or a shooting with a very personal motive where the killer needed to come face to face with his victim. And unless the calibre of the bullet is extremely small, such as a .22, it will create an exit wound which will enable the pathologist and ballistics expert to trace the trajectory and so determine the location of the shooter which can be crucial if, for example, an innocent bystander is caught in the crossfire between police and criminals who are using similar weapons and the bullet cannot be recovered. Or, as in the case of the 1984 London Libyan Embassy siege, proof was needed that a fatal shot came from within the building and not, as was claimed, from the roof (see here).

In the case of a fatal stabbing it may be necessary to prove that the attack was malicious and not an accident as the defendant might claim. Sharp cuts on the hands of the deceased are likely to be defensive wounds as the victim attempted to fend off their attacker. An examination of the shape and depth of the wound can reveal if it was a frenzied attack, as well as the size and type of blade (sharp or serrated, single or double-edged).

A fatal beating with a blunt-edged weapon, fists or feet will leave characteristic bruises known as contusions where the blood vessels were ruptured by force. Although bruising continues to occur after death, the shape of the contusions can reveal the nature of the weapon, the direction from which the blows came and an approximate time when the injuries occurred as they change from red through purple, brown and green to yellow within a few days.

Some fatal injuries, such as a blow to the head with a fist and shaken baby syndrome, leave almost no external marks of any kind, but are usually detected during an internal examination when blood clots in the skull turn out to reveal a brain haemorrhage (internal bleeding) as the cause of death.

Murder by fatal injection is, fortunately, rare and very difficult to detect as the hypodermic needle will leave only a tiny hole which can easily be overlooked. But in such cases a trace of the poison or drug may be detected by the toxicologist's analysis of the blood sample.

As forensic tools and techniques becoming increasingly sophisticated it is easier to distinguish between a suspicious death and one brought about by natural causes. Before the development of histology (the scientific analysis of microscopic slivers of body tissue) circumstantial evidence was often sufficient to secure a conviction and send many innocent people to prison or their execution if it was suspected that they might have hastened the departure of a wealthy relative or rival.

But now high-magnification devices such as a microtome can shave off a thin sliver of tissue from the vital organ under examination after which it can be stained with chemicals disclosing any damage caused by disease which may not have manifested as physical symptoms.

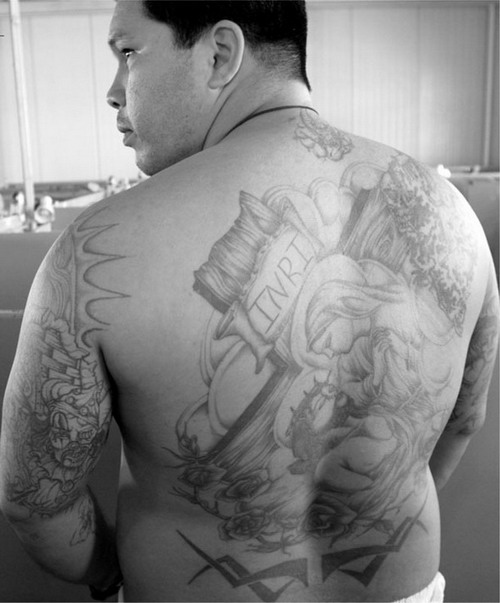

When a body is found without any form of ID, there are no grieving relatives or friends to claim the corpse and even the police have failed to find a match for the fingerprints on the national database, there is one clue which can put a name and a history to the deceased. A good pathologist or police officer can read a tattoo as readily as they can a bullet wound. Armed forces personnel have their own brand, often inscribed with their rank and service number, which makes an ID only a matter of a phone call. Prisoners carry theirs with equal pride – a cobweb design or a clock without hands denotes a seasoned ex-con, while many Hispanic prisoners will have had a Madonna de Guadalupe emblazoned on their back to deter rapists. Other 'inks' can be used to camouflage a history of heroin injections or to boast membership of a specific street gang, an Aryan supremacist group and many other brotherhoods and secret societies. Each street tattoo artist has their own distinctive style and signature which makes tracing the tattooist time-consuming but frequently worthwhile, but the toughest 'tats' to trace are those done inside prison by the con themselves or their cell mate which are made freehand with ink or cigarette ash or by a home-made machine using an empty pen, a guitar string and India ink.

A tattoo can be traced as easily as a bullet wound

A young man is found hanging by the neck from a noose in his apartment, a chair lying on its side on the floor beneath his body. But was it suicide, or has the scene been staged to cover up a homicide? In such cases it is impossible to be absolutely certain until an autopsy can reveal the true cause of death.

If the skin has a blue cast and the autopsy reveals distension of the lungs and burst blood vessels in the eyes then death is due to a lack of oxygen (hypoxia). But this does not indicate whether it was caused by manual strangulation or a rope. A rope will leave friction burns which only occur when the individual is alive at the moment of strangulation, but these could be caused by a ligature. Unless there is a V-shaped abrasion around the neck created by the rope during suspension of the body, the hanging could have been staged after death. If the deceased does not have friction burns around the neck then he or she must have been dead before the rope was put around their neck. A broken hyoid bone in the neck is almost always caused by manual strangulation, whereas a blue discoloration around the mouth and nose indicates smothering. If there are no rope marks on the neck, no bruising and the hyoid bone is intact, then the neck is likely to have been deliberately compressed, blocking blood flow from the vagus nerve to the heart which would result in heart failure.

Many a murderer has attempted to conceal their crime by setting fire to the scene and trusting that the flames will consume the evidence, but an experienced pathologist can uncover the true cause of death even from a charred corpse.

The classic clue to an accidental death by fire is the presence of soot in the lungs and carbon monoxide in the blood, which will turn it a cherry red colour. Soot is the result of smoke inhalation which leads to suffocation. Toxicology might also reveal cyanide in the blood which is created when synthetic materials such as ceiling tiles and certain types of paint react with flames.

If there is no soot in the lungs and no carbon monoxide in the blood the deceased is very likely to have died of burns which will have the characteristic inflamed edges created during the aborted healing process, known as a 'vital reaction' (proof that the person was alive when the injuries occurred). If none of these features is present and there is evidence of pre-burn bleeding then it suggests that the victim died of injuries prior to the fire (see 'The King's Cross Fire' here).

Drowning is a comparatively easier case to determine, although the corpse becomes bloated and subject to corruption after several days' immersion in water. But if the body is recovered within hours of drowning the characteristic signs should still be apparent during an autopsy. The lungs and stomach will be swollen and filled with water. There may also be blood in the stomach and airways indicating burst blood vessels as the deceased over-exerted themselves in their struggle to breathe. In cases of accidental drowning there may be indications of a heart attack brought on by shock or a vagal inhibition which can occur when water floods the back of the nose, or hypothermia caused by a fatal drop in the body's core temperature after immersion in cold water.

Even bath water and the water in chemically treated swimming pools will contain microscopic algae known as diatoms and, although seasonal fluctuations can reduce the concentration of diatoms, if those found in the ingested water do not match those in the water in which the body was found, death must have occurred elsewhere.

When police entered the home of Illinois businessman David Hendricks on 8 November 1983 they found a scene of sickening slaughter. Hendricks' wife Susan and their three children had been brutally slain with blows from a butcher's knife and an axe which the killer had had the presence of mind to clean before he left. The walls and ceiling were running with blood and the mattresses were caked in splatter and brain tissue. So when the distraught father pulled into his driveway later that night having returned from a business trip, police prevented him from entering the house to spare him the grisly sight. They also told him as little as possible about the horrific injuries his loved ones had suffered at the hands of their deranged attacker. It was therefore highly suspicious when very shortly afterwards Hendricks recovered sufficiently to talk to reporters and describe the scene in detail as if he had been there when the murders were committed.

Questioned again at length, Hendricks appeared to have an airtight alibi. He had left home at midnight on Friday 4 November and driven through the night to Wisconsin to have meetings with potential customers first thing the next morning. Over the weekend he made repeated calls to his family and neighbours after failing to get through to his wife on the phone. None of them had seen Susan or the children since the night he had left home, but they were all confident that his fears were unfounded. Apparently not satisfied with their reassurances, he called the police and asked them to check on his family to put his mind at rest. The phone company's record of the calls placed him across the state line, confirming his story. In addition, microscopic analysis of his clothes and his car failed to find any incriminating traces of blood. Of course he would have had time to clean himself up and discard any bloodstained clothing, but even to cynical homicide officers such a scenario seemed too unlikely to be worth considering seriously.

SUSPICIONS AROUSED

However, Hendricks' willingness to speculate with reporters on who might have been responsible for butchering his family aroused the interest of detectives whose first impressions had been that the scene had been staged. A deranged maniac would have ransacked the house in his rage, but the Hendricks' home did not betray signs of wanton destruction, nor even of a burglary that had gone tragically wrong.

But what reason would an apparently devoutly religious and successful businessman have for murdering his own family? Hendricks appeared to have neither the motive nor the temperament for committing such a horrific act.

But, as investigators discovered, it was his new-found success that had created the urge to kill. As the profits from Hendricks' orthopaedic equipment company grew he began to acquire a taste for good living, sharp clothes and the company of beautiful women. He became estranged from his wife whom he was forbidden from divorcing by the laws of his Christian fundamentalist faith and this inner conflict precipitated a mental breakdown which led him to butcher his family and then calmly walk away as if someone else had done it. However, suspecting that he had done it and proving it in a court of law were two different things.

The case hinged on the victims' time of death, because if it could be proven that they were killed before midnight then detectives could discard the deranged intruder theory and place David Hendricks at the scene of the crime. At the autopsy the pathologist examined the stomach contents of the three children which contained half-digested pizza which they had eaten between 6.30 and 7.30pm. One would expect that the meal would have passed into the lower intestine after two hours but the fact that it hadn't travelled that far meant that they had been killed before 9.30, when their father was still at home. The best the defence could do at the trial was to argue that the children had been playing energetically after their meal and that exercise is known for slowing the digestive process, but the experts concurred that this would delay digestion by only an hour.

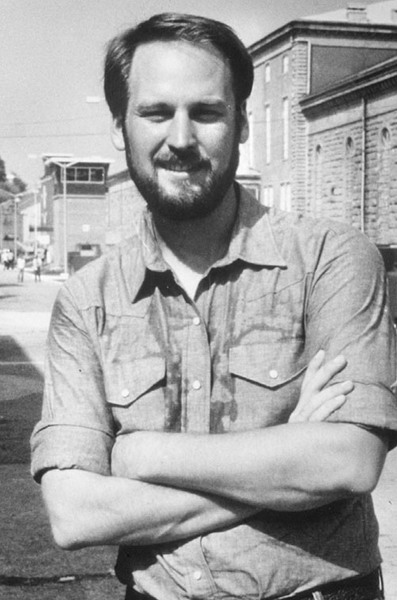

David Hendricks outside prison in 1990

Whatever sympathy the jury might have had for David Hendricks evaporated when they were presented with the image of a callous father who calmly fed his children then slaughtered them so that he could be free to pursue other women. It is an image Hendricks will have to live with every day for the full term of his life sentences, all four of them.

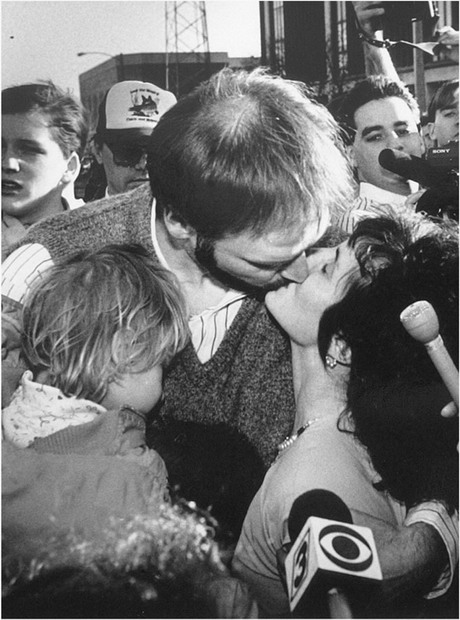

Hendricks gets a kiss from his second wife Pat

The thorough investigation into the mysterious death of billionaire publisher Robert Maxwell was a model of modern forensic procedure. It also demonstrated that in the digital age a pathologist is expected to be much more than an anatomist. He or she must also be a forensic medical investigator with the restlessly inquiring mind and the dogged patience of a trained detective.

When the lifeless body of Robert Maxwell was fished out of the waters off Tenerife on 5 November 1991, rumours were rife that the 68-year-old publishing tycoon had committed suicide to avoid the shame of bankruptcy.

Obituary writers were forced to rapidly revise their rags-to-riches stories when it became known that the Serious Fraud Office were looking into serious irregularities in the Mirror Group pension funds. It seemed that £426 million had disappeared, together with an additional £100 million from the Mirror Group accounts, just days before the fateful voyage.

The alleged theft was not a paper crime but a human tragedy, as many ordinary hard-working people had placed their life savings and their trust in 'Uncle Bob's' supposedly iron-clad savings fund. The revelation of irregularities on such a massive scale would have meant more than financial ruin for the larger-than-life empire builder. It would have brought more shame than he could have lived with.

When it became known that a £55 million loan from the Swiss Bank Corporation was due for repayment on the day he died and that failure to honour the debt would have brought in the receivers, all the signs pointed to suicide. Maxwell appeared to have taken the easy way out. Or had he? It certainly looked that way until a startling suggestion was made by the Maxwell family lawyer which was echoed by the publisher's own daughter, Christine. They claimed that financial irregularities had nothing to do with her father's death. As far as they were concerned, Maxwell had been murdered.

CONSPIRACY THEORIES BEGIN

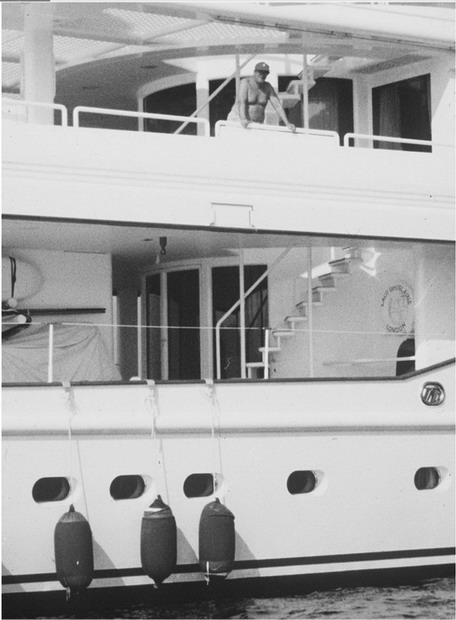

Ten days earlier Maxwell had been named as an unlikely Israeli secret agent in a controversial new book and now he had apparently been silenced to prevent his alleged involvement in illegal arms deals being made public. It seemed like a desperate attempt on behalf of the family to put up a smokescreen until several witnesses came forward to verify that Maxwell's 450 ton motor yacht, the Lady Ghislaine, had been shadowed for several days prior to his death by an unidentified vessel with no visible markings, name or flag. Furthermore, a swimmer had been seen in the water when the boats had been at anchor, which raised the possibility that Maxwell might have slipped quietly overboard to begin a new life while a lifeless look-a-like had taken his place in the water. Ridiculous though the suggestion seems, it was a fact that the initial Spanish autopsy had described the corpse as having an 'athletic build' whereas Maxwell was a grossly overweight 20 stone. Was it simply a mistranslation or had there been a substitution to save Maxwell and his Israeli spymasters embarrassment?

A former stewardess on the yacht had reported overhearing Maxwell planning to fake his own death and escape to South America just a few months earlier, but even if this was true it could have been an idle fantasy prompted by the likelihood of impending financial ruin. However, Christine Maxwell was deadly serious to the point of detailing how her father's murder had been effected. She claimed an air bubble had been injected into his bloodstream to induce an embolism which would have been diagnosed as death by natural causes – a favourite method of international hit men. When it became known that the Spanish pathologists had discovered a tiny perforation below one ear for which they could not account, the conspiracy theorists went into overdrive. The only chance of separating fact from fiction was to hold an autopsy for, as every criminalist knows, 'the evidence never lies'.

A preliminary autopsy had been carried out by the Spanish authorities which concluded that Maxwell had died of a heart attack before he hit the water, an assumption which the family vigorously disputed. It was evident that they were laying the groundwork to contest a £20 million insurance claim which would only pay out in the event of accidental death. Later it transpired that someone had anticipated the Spanish pathologist's findings. There was no evidence of a heart attack and no physical evidence to indicate that Maxwell had died of natural causes before falling into the sea. The Spanish pathologist reputedly asked the Maxwell family if he could bring in UK forensic experts to assist him, but on each occasion he was refused.

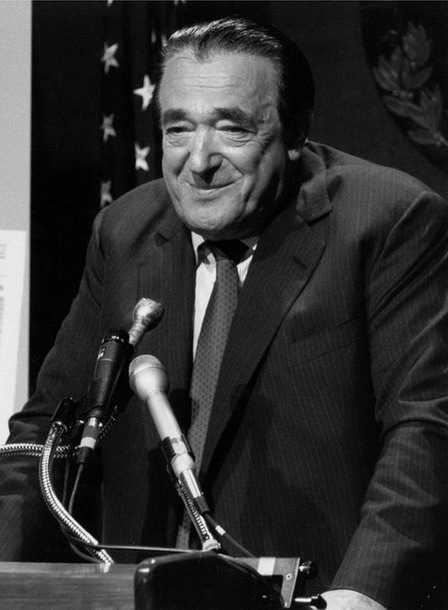

Had Robert Maxwell been planning to fake his own death?

Maxwell on his yacht, Lady Ghislaine

THE EXPERT PATHOLOGIST ARRIVES

In the event the insurance company organized their own autopsy and hired one of the world's leading forensic pathologists, Dr Iain West, and his wife Dr Vesna Djurovic to uncover the truth. But time was against them. According to Jewish law the deceased must be buried within a week and Maxwell was due for a full state funeral on the Mount of Olives in Jerusalem on Sunday 8 November. By the time the body had been flown to Israel and the autopsy team assembled it was already Saturday night.

Unfortunately both the body and the boat had been compromised as far as forensic evidence was concerned. The Lady Ghislaine had returned to sea the day after its owner's death without fingerprints, footprints or any trace evidence being secured. More crucially, the body had been contaminated by the overuse of neat embalming fluid and several organs were missing, although the Spanish judge had had the foresight to order tissue and toxicology tests as well as scrapings from underneath the fingernails to determine whether there had been evidence of a struggle. No such evidence was found.

They also had to contend with a number of false leads, such as the pool of dried blood inside the skull cavity, or vault, which is a classic sign of haemorrhage. But in this case it was explained by the fact that the Spanish pathologists had not drained the skull completely but had instead filled it with embalming fluid, leaving a residue of blood to dry at the back of the skull.

The first question the autopsy team had to settle was that of identity. The matter was settled swiftly and simply by comparing X-rays of the victim's jaw with his dental records. Britain's leading forensic odontologist, Mr Bernard Sims, identified several identical features including a uniquely shaped filling that proved conclusively that the body was that of Robert Maxwell.

THE SEQUENCE OF EVENTS

There was some dispute as to the time of death, which is a critical detail to resolve if there is a suspicion of foul play. At 4.55am on the morning of his death Maxwell had called the bridge to request that the air conditioning be turned down. That was the last anyone had heard from him. The alarm was eventually raised at 11am, when a call was put through that he didn't answer. The captain went down to investigate and discovered that the staterooms were locked from the outside, which was highly suspicious.

After a massive air and sea search Maxwell's naked body was spotted at 5.46pm, face upwards and with his limbs outstretched. This in itself was unusual. Suicides do not usually drown themselves while naked and when they do they are invariably found face down and in the foetal position. If a body is found naked it suggests that drowning was the result of an accident. It was known that Maxwell slept naked and was in the habit of relieving himself over the edge of the boat during the night at a point where only a thin wire prevented him from falling into the sea. But at that point there was only a 30cm (12in) gap between the wire and the motor launches, which was too narrow for a man of Maxwell's bulk to fall through – and if he had fallen at that point he would have been sucked under the boat and cut up by the propellers.

Also, the sea was calm that morning and the stabilizers were engaged, so there was no reason to suppose that a sudden swell had tipped him over the side. He couldn't have fallen overboard anywhere else because there were guardrails running the full length of the yacht from prow to stern. He would have to have deliberately climbed over them, or been manhandled over the side.

Moreover, the crew of the search and rescue aircraft had scoured the area where the body was later found and had seen nothing, although it was possible that the body had floated to the surface just before it was sighted. Maxwell's obesity meant that his body could not be expected to behave in a typical fashion – that is, sinking below the surface for several days before resurfacing in a bad state of decomposition.

THE MYSTERY DEEPENS

The characteristic sign of death by drowning is water in the lungs and stomach and in the case of a drowning at sea the inrush of salt water raises the chloride level in the blood on the left side of the heart. There was surprisingly little salt water in Maxwell's lungs. One explanation is that he died from heart failure when he hit the cold water which would have prevented him from taking in any more water.

The absence of rigor mortis gave the pathology team further cause for concern, raising the possibility that the body could have been dumped shortly before it was sighted. If Maxwell had entered the water shortly after his request to turn down the air conditioning, he would have been in the water for 12 hours and rigor mortis should have been evident as it sets in more quickly in water than on dry land, although the temperature of the water is a factor. But then it occurred to Dr West that rigor mortis might have been dissipated when the body was hauled out of the water by the helicopter as movement of the limbs is enough to break up the condition. There is also the possibility that the rigor mortis had simply passed over some time earlier.

A pathologist has to be particularly thorough in an important case such as this one, and Dr West insisted on sending a sample of Maxwell's bone marrow back to England for analysis together with a sample of sea water from the spot where the body was found. The purpose was to see if there was evidence of diatoms, a microscopic plankton which one would expect to find in the lungs of someone who had drowned. They were not found in Maxwell's body, but neither were they detected in the sea water. The mystery was explained by the fact that the diatom population is extremely low in that region at that time of the year. Other clues would have to be found.

There were various bruises and abrasions on the body, some of which were caused by the Spanish manhandling the body during its recovery from the sea, but there was a suspicious looking bruise on the forehead which could not be explained. Had Maxwell hit his head on the side of the boat during a fall or a suicide attempt, or had he been pushed over board and struck his head as he fell?

The evidence was inconclusive because a bruise sustained during a struggle in the cabin would be identical to one sustained post mortem during a tumble overboard. But there were no restraint marks which are a typical sign of a struggle.

Internal examination offered a likely clue. The team found up to 95 per cent blockages in some of the coronary arteries and this, combined with Maxwell's behaviour that morning, indicated heart problems, though not necessarily a full-blown coronary. He had complained of nausea and of feeling hot and cold. There were traces of vomit in his respiratory tract and in his lungs and traces of seasickness pills in his system.

It was beginning to look likely that he had lost his balance while retching over the side and then suffered a fatal heart attack from the shock of the fall and the coldness of the water. There was evidence of heart and lung disease in the tissue samples but it was not sufficiently advanced to be the primary cause of death. Moreover, if Maxwell had suffered a heart attack, he would have dropped on to the deck and not tipped over the side.

Then, as the dawn was approaching over Tel Aviv, the pathology team made a significant discovery. After rolling the body on to its front they cut and folded the skin back to reveal extensive haemorrhaging and torn muscle fibres on the left shoulder as well as on the lower left side of the spine which also exhibited extensive bruising. This, coupled with bruises found on the right shoulder, on the right side of the neck and behind the right ear, indicated that Maxwell must have been clinging on to something such as a guard rail after having fallen overboard and banged the back of his head on the side of the boat as he twisted round. But his excessive weight would have torn the muscle, causing him such sharp pain that he would have let go of the rail and plunged into the water.

In his report to the insurance company Dr West concluded that there was no evidence of murder and that suicide was the most likely scenario. To Dr West the muscle tear indicated that Maxwell had fallen overboard accidentally perhaps while contemplating suicide and had instinctively grasped at the rail but then lost his grip through pain. If he had been attacked by an intruder and murdered, he would most likely have been knocked unconscious as he fell and then he would probably have been thrown cleanly overboard.

The fact that Maxwell went over at a point where there was a protective rail made an accident highly unlikely and suggested that he must have intended to go overboard, so his death must be assumed to be a suicide. The insurance company kept their £20 million payout and no doubt considered Dr West's fee and his expenses money well spent.

The family gathers for Robert Maxwell's funeral