‘In no single theatre are we strong enough.’ So lamented Field Marshal Sir Henry Wilson, the austere, thin-faced Ulsterman who, as Chief of the Imperial General Staff in May 1920, held the ultimate responsibility for the strategic defence of the British Empire. The list of danger zones he identified was a long one. Ireland in the grip of civil war; Germany unbowed and resentful; Turkey determined to recover lost ground; Egypt seething in the aftermath of failed revolution; Palestine, its future in British hands uncertain; Iraq reeling from northern and southern rebellions; Persia, wavering between British and Soviet influence; India wracked by food riots and nationalist ferment; even the home waters of the British Isles less defensible than they once were.1 Yet surely Britain, the old imperial lion, had just won a war with the help of its loyal overseas subjects.

Along with France, the other imperial giant, the British were only now dividing the war’s colonial spoils in the Middle East and Africa. Why, then, was Wilson’s imperial forecast so gloomy?

The basic reason was simple. Neither at this point, nor in the decades that followed, did British (or, as we shall see, French) political and military decision-makers match the pace of colonial change or predict its course. This was not some sort of collective lapse of judgement. Few on the eve of war in 1914 could have foreseen the scale of colonial problems immediately after it. Admittedly, some challenges were unsurprising. Rebellion in Ireland had been stewing for decades. Yet its eruption, first into an Anglo-Irish confrontation, then into civil war sent shock waves throughout the British Isles and the wider Empire. Wartime French governments also predicted—indeed exaggerated—the potential for wartime dissent in their turbulent North African territories, especially after Ottoman Turkey, a largely Muslim country, entered the war against the Allies in October 1914.2 But disorders in other places—British-ruled Ceylon or the federation of French West Africa for instance—were unforeseen. Like their European overseers, colonial societies were rocked by the war’s insatiable appetite for new blood.

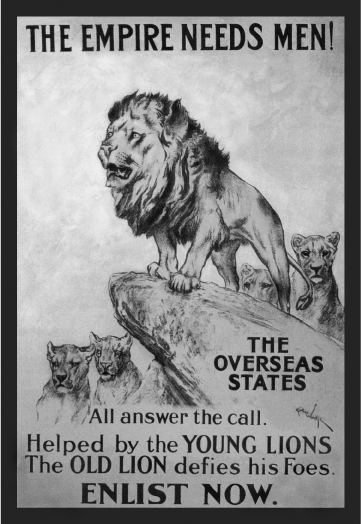

Figure 1. ‘The Empire Needs Men!’ The metaphor of imperial family—and British seniority—deployed in First World War recruitment.

Anti-conscription protests, expressions of desperation more than organized revolts, spread through French North and West Africa between 1915 and 1917. The call-up system assigned quotas to local notables or chiefs, whose job it became to ensure that sufficient draftees appeared before regimental recruiters. The cycle would then repeat itself a few months later. These recurrent call-ups disrupted agricultural production and sapped people’s respect for their customary rulers. Recruiters’ methods seemed arbitrary. Often they were brutal too. Families confronted painful choices over which young family members could be spared.3 Here the fight or flight dilemma took human form. Thousands of young Africans both in this World War and the next escaped ‘paying the blood tax’ by fleeing across colonial frontiers from French into British territory, or vice versa.4 Politicians and generals who had expected that mobilization of colonial resources and, more particularly, manpower would help win the war were compelled, briefly, to pause.5 The social destabilization caused by colonial conscription was not confined to French Africa. Even the most ardent enthusiasts for the employment of Indian, Canadian, Algerian, or West African troops on the Western Front did not expect that these men would die in their tens of thousands over four years of trench warfare. By 1917 imperial governors throughout both empires expressed mounting unease over the destabilization caused by such losses.6

Still more unanticipated were the extraneous pressures that Europe’s imperial masters would face after 1918, ironically, as direct costs of victory. Few predicted that two of the most dangerous challengers to British and French imperial power would be Japan and Italy. Both were erstwhile allies of’14–’18 dissatisfied with their limited share of the spoils.7 Fewer still foretold the coming reorientation in American diplomacy, economics, and outlook. Veteran politicians and seasoned diplomats in London and Paris indulged the attachment of the US President Woodrow Wilson to open diplomacy, international conflict regulation, and ethnic self-determination as ways to prevent future war in Europe.8 But none of them welcomed the extension of ‘Wilsonian’ ideas to the non-European world.9

As the new Mandate frontiers shown in Map 3 were imposed between the Arab territories formerly ruled by the Turks, favoured clients were selected among local elites to help consolidate the presence of the new imperial masters from Britain and France. In the process, older, more malleable conceptions of civic identity among the populations of former Ottoman provinces from Syria, through Palestine to Iraq, were supplanted by harsher, inflexible assertions of communal difference. Ethnic identities became reified and increasingly politicized, used as a marker of inclusion or exclusion by hardliners on all sides of the Middle East’s new ethno-politics. In Syria, for example, identifying oneself as Sunni, Druze, Alawite, or Christian acquired a stronger political significance.10 The notion that, by the early 1920s, social identities would become ossified into fixed categories might have seemed outlandish to the subjects of erstwhile Ottoman dependencies only years before. So, too, for British and French imperial administrators the idea that an international regulatory authority—the League of Nations—might set limits to planned territorial acquisitions and monitor their standards of colonial governance would have appeared ludicrous a decade earlier.11

Map 3. Middle East Mandates.

Perhaps even more important, the full implications of British and French emergence from the war as financial dependents of the United States were barely understood after the conflict, let alone before it. Fateful post-war decisions were made in London and Paris that pegged sterling and the franc at high tradable values tied to a new ‘gold standard’. The resultant inflated value of each currency created huge financial problems, not just domestically but imperially too.12 As always, questions of money and empire remained interlocked. Few colonies were unaffected by the fortunes of the British and French economies. The ups and downs of metropolitan currencies, export industries, and employment markets reverberated through colonial territories in the decade between the end of World War I and the Wall Street Crash in October 1929. The depression then brought these connections into even starker relief.13

As Robert Boyce puts it, the inter-war period’s most remarkable feature was the simultaneous disintegration of the international political system and the international economic system.14 The consequences of this double-edged collapse would become clearer once the depression of 1929–35 brought its two constituent elements crashing together in the rise of economic nationalism, fascist militarism, and a new arms race with a terrifying impetus of its own.15 Refracted within colonial territories, the ‘deglobalizing’ of international trade after 1930 was felt in calamitous falls in commodity prices, real-terms inflation, and declining purchasing power.16 Hard lives got harder still. For colonial subjects the depression was primarily experienced in terms of the affordability of food. In pockets of colonial Africa and much of southern Asia poverty diets deteriorated into chronic malnourishment.17

The intersection between colonial food costs, deteriorating public health, and social disorder was evident before the depression of course. There were food riots in southern India in 1918.18 In Dakar, in Senegal, French West Africa’s federal capital, bubonic plague, the second outbreak in five years, killed over 700 in 1919. The spread of infection was facilitated by problems associated with chronic poverty, especially overcrowding and poor hygiene.19 Well into the inter-war period particular lethal epidemics retained their association with specific colonial regions—cholera in India, sleeping sickness in the Congo Basin, yellow fever in Indochina. Politically, the most salient feature of the crisis of empire in the decade prior to the 1929 crash was the emergence of organized opposition movements, often the forerunners of the nationalist groups against which British and French colonial security forces would struggle for years to come. In 1919 Britain’s service chiefs, thrown off balance by the developing civil war in Ireland, fretted that the empire’s expanded frontiers could not be held.20 Post-war demobilization made matters worse. Colonial ex-servicemen, especially the hundreds of thousands from the Indian subcontinent, seemed a volatile constituency sure to be targeted by anti-British agitators inside and outside the empire.21 During 1918 and 1919 former soldiers were central to economic protests and ugly race riots from Liverpool to Kingston, Jamaica, making a mockery of presumed imperial unity in Britain’s victorious Empire.22

The allied coalition had often enunciated contradictory war aims. But their central message was that ethnic self-determination offered the best route to the long-term stabilization of states and the relations between them.23 This was a message enthusiastically taken up by politicians, public intellectuals, and other elite actors in the colonial world. Sa’d Zaghlul, spokesman of Egyptian nationalism, Shakib Arslan, a Druze parliamentarian from Syria, India’s Bal Gangadhar Tilak, and a boyish Nguyen Ai Quoc (later to adopt the nomme de guerre Ho Chi Minh) all petitioned the peacemakers in Paris for limited reforms that would concede greater equality to the elite social groups they represented.24 Without exception, their claims were rejected. Independent ‘nation-states’ were not set to arise from the ashes of former colonies; the League of Nations was not about to protect the rights—national or individual—of colonial peoples.25 British public pressure for it to do so, articulated through the League of Nations Union, was yet to register.26 In several dependencies, not least British India, the disappointments of the so-called ‘Wilsonian moment’ were keenly felt.27 This is a reference to President Woodrow Wilson, whose pressure for fundamental changes in the way international relations were conducted had, briefly, promised some redistribution of wealth and power in colonial territories. In practice, the ‘moment’ in question proved fleeting. But the nationalist genie was out of the bottle.28

Egypt’s administrative elite of effendiyya, Palestinian share-croppers, Saigon’s silk-farmers, and Caribbean cane-cutters: all clashed with colonial security forces, turning workplace protests into acts of rebellion. Those driven to protest by poverty, discrimination, or both, found common cause with local politicians, often from more elite backgrounds, who demanded basic rights and, ultimately, nationhood for their communities.29 Uprisings, repression, and the devastating impact of severe economic crisis made large parts of the British and French Empires from Jamaica to Indochina virtually ungovernable by 1939.30 In these locales, the advent of another world war did not catalyse pressure for withdrawal; it merely contained pre-existing opposition for a few more years. So this chapter’s core argument is simple. Understanding the end of empire should not begin with the consequences of the Second World War but with the colonial crises that prefigured it. Fight or flight was a reality decades before 1945.

Colonial representatives hopeful that the Great War might usher in fundamental changes in the way the British and French empires were run were quickly disillusioned, something that seems sadly predictable in hindsight. Particularly so when one considers the way territorial redistribution of former Ottoman territories in the Middle East was handled by the two victorious imperial powers. The acquisitive instincts of British and French post-war governments were nowhere more apparent than in their squabbling over the carcass of the Ottoman Empire. In a diary entry in October 1918 the Cabinet Secretary Maurice Hankey recorded the improvisation and mistrust in inter-allied discussions about the choicest morsels of territory. On the 3rd he noted the fury in the War Cabinet after it emerged that the Foreign Secretary A.J. Balfour had promised the French that the horse-trading embodied in the 1916 Sykes-Picot agreement would stand. France would ‘get’ an enlarged Syria, probably including the oil-bearing region of Iraqi Mosul. The Prime Minister Lloyd George would have none of it. He was determined to revoke the Sykes-Picot accords in order to secure an enlarged Palestine for Britain and the incorporation of the Mosul vilayet into a British-ruled Mesopotamia (Iraq). He even devised ‘a subtle dodge’ to invite the United States to govern Palestine and Syria. This, he thought, might scare the French into conceding a British-run Palestine in order to safeguard France’s toehold in the Levant.31

With such convoluted scheming it was hardly surprising that in the unsettled Middle Eastern political climate after 1918 differing British and French calculations about the wisdom of supporting the Hashemite dynasty poisoned relations between the two imperial powers.32 The Hashemite King Feisal established an independent, populist regime in Syria in late 1918, and figured among those that lobbied the Versailles peacemakers a year later.33 It was to no avail. After a brief military showdown outside Damascus Feisal’s Syrian government was evicted by the French military administration that took charge of the country as a League of Nations ‘mandate’ territory in July 1920.34 Britain, by contrast, stuck with monarchical figureheads, identifying loyalist communities that might serve them. Feisal seized the opportunity to relocate to Iraq. His brother Abdullah was installed as Emir of another British mandate—Transjordan.35 As these arrangements suggest, Britain emerged with vastly increased Middle Eastern assets and commitments, next to which French acquisition of mandates over Syria and its splinter state, Lebanon, seemed almost modest.36 Thus a paradox: the destabilization of the British and the French empires between 1914 and 1923 did not preclude their expansion. Both reached their largest physical extent in the early 1920s.

Home-grown opposition to empire struggled to make itself felt in inter-war Britain. The anti-imperialist sympathies of liberal critics, missionary groups, members of the Fabian Colonial Bureau, or rank-and-file supporters of the Labour party and the TUC were narrowly circumscribed. For one thing, it was widely presumed that political reforms and material improvements to colonial life were best accomplished with British sponsorship, an assumption reinforced by the Colonial Office rhetoric of ‘trusteeship’, which recast imperial rule as being guided as much by ethical concerns as by profit or strategic advantage. For another thing, tough economic conditions at home sapped enthusiasm for any imperial spending or loosening of trade privileges liable to affect British prosperity or working-class pockets adversely.37 Imperial loyalty remained an unspoken certainty among British Ministers of every political stripe between the wars, but the extent of ministerial enthusiasm for, and interest in, empire varied sharply. For the Colonial Secretary Leo Amery, child of the Raj and perhaps Britain’s most fervently imperialist parliamentarian, his colleagues in Stanley Baldwin’s second Conservative government were a shocking disappointment.38 Reflecting on the past twelve months on New Year’s Eve 1928, he confided his thoughts to his diary: ‘I have felt myself very much estranged from most of my colleagues in the Cabinet. I cannot help feeling that they understand nothing about the Empire, and some of them are acquiring a definitely anti-Dominion complex.’39

As Amery discerned, an inter-war crisis of empire was real enough, its aftershocks linked to a wider global crisis triggered by the war’s messy aftermath.40 Europe’s two imperial giants were bloated with colonial territory but perilously short of the ready money and powerful allies needed to digest it. Britain’s imperial ‘world system’, as explained by John Darwin, required certain pre-conditions, first to facilitate its expansion in the nineteenth century, next to sustain it through the early twentieth, and, finally, to permit its recovery after the upheavals of the Second World War. Among these was a relatively passive East Asia. It is arguable whether this was ever achievable. It was certainly absent from the mid-1920s onwards. Closer to home, a balance of European continental forces proved equally unattainable until the Cold War imposed an artificial but enduring stasis on European boundaries after 1945. Elsewhere, the benevolent strength of North American partners—Canada and, above all, the United States—offered more constant assurance. Some French and British leaders—French premier Georges Clemenceau at the start of the inter-war period, Britain’s Neville Chamberlain at the end of it—treated America disdainfully.41 But US goodwill ebbed and flowed within a narrow tidal range, and helped keep British imperial power afloat most of the time. US anti-imperialism should not be overplayed. A cherished myth of America’s history after 1776, it was belied by the facts. America remained a prominent Southeast Asian imperialist between the wars and a commercial rival for colonial markets elsewhere.42 The Suez crisis of 1956 proved that Washington’s whip-hand packed a killer punch, but anti-imperial US interventionism remained the exception and not the rule.

Unfriendly towards the western empires after the 1917 Revolution, Soviet Russia was also more quiescent towards capitalist imperialism than British and French doomsayers imagined.43 During and after the Russian Civil War the more empire-minded of Britain’s strategic planners identified Cold War-style Soviet threats to Britain’s presence in Asia. The Conservative Foreign Secretary, and former Indian Viceroy, Lord Curzon took these anxieties furthest, but he was never alone.44 In December 1924 the General Staff warned of Soviet pressure on a northern Asian tier of British imperial interests that traced an arc from the Shanghai international settlement through India’s North-West frontier and Afghanistan to northern Iran and Kurdish Iraq.45 It must have seemed oddly familiar to politicians and soldiers who built their careers in the age of Victorian high imperialism. But there was a new aspect. Fear of Communism introduced an ideological edge to the old Great Game of vying for imperial supremacy in central and eastern Asia. No longer a straightforward competition for clients, markets, and territory, the Game was now dominated by intangible, transnational factors. The spectre of Tsarist bayonets was replaced by the spread of new ideologies and hostile propaganda that were harder to monitor and deter.46 Among the strategic planners accustomed to this kind of global geo-politics, the Russian menace to colonial rule was no longer simply conceived in terms of military incursion but of Comintern-sponsored internal sedition as well.47 Fears of a subversive anti-colonial ‘enemy within’ encouraged the creation of additional secret service and special branch agencies throughout the empire.48 But for other grand strategists in government, British imperial defence policy retained its Oceanic flavour. Summarizing the problems of protecting the British Empire in June 1926, the chiefs of staff framed the problem in global maritime terms:

Scattered over the globe in every continent and sea, peopled by races of every colour and in widely differing stages of civilisation, the component parts of the Empire have this much in common from the point of view of defence, that, with occasional and insignificant exceptions they are able to maintain order with their own resources supplemented in some cases by Imperial garrisons maintained for strategical reasons. But for any larger emergency requiring mutual support or co-operation they are dependent on the sea communications which unite them. If these communications are closed they become liable to defeat in detail. Moreover, the Mother Country, the central arsenal and reserve for the whole Empire, is dependent for the essentials of life on the maintenance of a network of sea communications extending not only to the territories of the Empire, but to every part of the world. The maintenance of these sea communications, therefore, is the first principle of our system of Imperial Defence.49

Imprinted with the Admiralty’s dominance of Britain’s inter-war military establishment, here were the essentials of ‘empire-mindedness’, ‘blue water imperialism’, defence of free trade, and the enduring myths of British plucky ‘Island race’ history rolled into one.50

To talk in similar terms of a French ‘world system’ would be misleading. France attached prime significance to European affairs—and dangers—not to global ones. Contrasting interests in oil provide some indication of this. France, like Britain, devoted unprecedented attention to securing oil supplies during the 1920s. New interests were acquired in Iraq, Poland, and Romania, and oil exploration continued in its colonies of Algeria and Madagascar. Unlike Britain, however, French oil needs were comparatively small. French industry consumed 1.2 million tons in 1923 next to Britain’s five million. The disparity was largely explained by the larger size of Britain’s oil-fired merchant navy. With fewer oceanic commitments, French governments also opted for tighter regulation of the domestic oil market to maintain stocks and dampen fluctuations in fuel prices in preference to massive investment in overseas drilling.51 The motor of French imperialism was not oil-driven.

Nor was it propelled by settlers. With no equivalents of Britain’s Dominions, there were not enough French-born whites living in the empire to challenge the fixation on continental matters. As if to underline the point, one of the largest francophone migrant diasporas—the French Canadians of Quebec—were governed as part of a British Dominion, not a French one. Substantially self-governing, the Dominions’ dominant Anglo-identities were shaped by nineteenth-century migration and complex networks of familial, cultural, and economic ties.52 Canada, Australia, New Zealand, and, more problematically, South Africa and the Rhodesias were major political actors in their own right, as much making the British world system as being made by it.53 On paper at least, from 1926 Canada, Australia, New Zealand, and South Africa enjoyed ‘equal status’ with Britain as associates in an emerging Commonwealth. In practice, it was years before these new arrangements were fully enacted. The scale of white settlement in these societies makes it difficult to see them as early models of a successful Anglophone ‘flight’ strategy, of a gradual and more or less amicable loosening of British imperial control.54 Fiercely proud of their nation-building achievements, the white Dominions remained, to varying degrees, culturally deferential and economically and strategically tied to Britain until the 1950s. Although formally self-governing, the Dominions’ enduring sense of Britishness signified not just a positive cultural choice but some degree of imperial attachment as well.55

France, of course, had its white enclaves overseas, from the Caribbean territories to the settler-dominated cities of North-West Africa. The administrative buildings and residential apartments of Tunis, Algiers, Oran, and—fastest growing of them all—Casablanca, put one more in mind of Marseilles than Marrakech.56 But even Algeria, ‘made French’ to the extent that it was constitutionally subsumed into a metropolitan super-structure of regional départements and Interior Ministry oversight, remained stubbornly foreign, exotic, and, on occasion, hostile. Fictional writing by French Algerian settlers, which attracted a wide readership in inter-war France, played on these traits. Algeria’s settlers—or colons—were still looked upon, and considered themselves to be, a race apart, a rugged, hybridized community accustomed to adversity and contemptuous of the woolly idealism of metropolitan imperialists.57

With no large, self-governing territories to accommodate, the French Empire’s rulers were, by inclination, centralizers aspiring to greater colonial uniformity. To achieve this, they were keener than their British counterparts to export metropolitan ideas, practices, and cultural norms to dependent societies.58 Overseas territories were, for them, integral to a French ‘empire nation-state’. Built on republican ideals and dedicated to the closer integration between motherland and empire, this was more a politico-cultural project than an economic reality sustained by domestic financial investment and multi-continental white settlement. A world system it was not, but a vehicle for the promotion of an idealized brand of ‘Frenchness’ it certainly was.

French colonial administration was elevated to the status of a doctrine because of its cultural emphasis on changing the beliefs, habits, and associational life of subject peoples. The principal weapon in the colonial armoury was the French language, command of which was an obvious marker of an individual’s successful ‘assimilation’ to French standards of probity and politics. Potentially all-embracing, this doctrine of ‘assimilationism’ in fact remained highly exclusive.59 Advanced education, which required money, connections, or both, was one route to citizenship—the official imprimatur of Frenchness. Accidents of birth, especially a French-born father, were another.60 For the majority who secured it after 1918, citizenship came as a reward for sacrifice: either a professional career in the military or active service in the Great War. Assimilation, then, came with undeclared economic requirements, a heavy gender bias, and a pronounced martial flavour. All three were at odds with the egalitarian rhetoric used to justify it.61

We would thus be ill-advised to think of French colonialism as qualitatively unique insofar as its declared cultural objective of integrating—or assimilating—dependent societies with France remained substantially unfulfilled. Equally, we should resist the temptation to be dismissive. To its many supporters at home and, indeed, in the colonies, the French empire differed from its British equivalent because its raison d’être was the betterment of dependent peoples. The lives of colonial citizens, an elite minority, were bound to be enhanced thanks to their complete immersion in French values. Meanwhile, the mass of colonial subjects, despite being confined to a lesser status, would still profit from seeing and hearing French administration, language, and cultural practices performed around them. France’s imperial training grounds were the classroom, the magistrate’s office, the midwifery clinic, and the colonial army recruitment centre. The African, Asian, and Afro-Caribbean peoples who passed through these places as schoolchildren, as property owners, as mothers, or as soldiers were stepping up the rungs of the assimilation ladder to the lofty heights of citizenship of the Republic.62 In the two sub-Saharan federations that spanned West and Equatorial Africa as well as in the other great French imperial federation, Indochina, colonial rule was of sufficiently long standing to have produced thousands of young men (numbers of women were significantly smaller) who had reached the top of the ladder. Those who climbed up through military service could reasonably expect post-war civilian employment, perhaps as policemen, or postal employees. But the smaller numbers that had undergone French secondary or even higher education craved access to more sought-after positions: in the professions, in local or even national government. Most would be disappointed.63

The consequent alienation of these évolués (literally, ‘the [culturally] evolved’) in francophone black Africa and French Vietnam was critical to the emergence of two distinct strands of opposition to colonialism. The first was primarily cultural, a reassertion of the vitality of indigenous arts, linguistic forms, and associational life denigrated by French colonial educators and administrators. The second was more conventionally political: the rejection of assimilationist rhetoric as an elaborate sham and a turn towards integral anti-colonial nationalism. The former strand was exemplified by the negritude movement, which emerged among a select group of black African and Antillean students, writers, and political activists in inter-war Paris. Theirs was a predominantly literary, humanistic opposition, often militant in tone but never violent in practice. Writers like the Martiniquan poet Aimé Césaire stressed the distinctiveness and intrinsic value of African cultures and the specificity of black historical experience of European enslavement and persecution. Yet they also acknowledged the utility of a continued relationship with France.64 The greater radicalism of the latter strand was personified by Ho Chi Minh. Along with several co-founders of the Indochinese Communist Party (ICP) between 1918 and 1930 he made the journey from Paris-based student évolué dressed in suit and tie to Marxist outlaw in peasant attire.65 Proponents of socialist modernization, these first-generation Vietnamese Communists lambasted colonialism’s stultifying effects. Colonial citizens were condemned to be subordinate, ersatz copies of the real thing. And French administrators absolved themselves of responsibility for the poor majority of their colonial subjects by claiming that social inequalities were endemic and unchangeable.66

Ho and his colleagues had touched a nerve. Advocates of assimilation confronted two dilemmas between the wars. One was that its limited achievements became harder to conceal. The other was that the policy was no longer in vogue among bureaucrats or politicians. During and immediately after the First World War administrators in the French colonial federations proclaimed their conversion from assimilationist ideals to a more pragmatic and less disruptive style of governance, dubbed associationism.67 Closer to British ideas of indirect rule in its selective accommodation with local customs and cultures, associationism was less republican and radical than politically and socially conservative. In a complete role reversal, during the inter-war years official colonial rhetoric venerated traditional hierarchy, customary law, and the authenticity of peasant life.68 Where assimilationism sought to re-engineer colonial societies, associationism preserved them as if in a museum. One of its more obvious by-products was to marginalize the évolués whose acquisition of French citizenship had been a key justification for ‘assimilation’.69 Traditional authority figures—Ivorian chiefs, Senegalese sufi brotherhoods, Vietnamese mandarins and village headmen, once derided as obstacles to the spread of republican civic virtues, were reinvented as guarantors of social stability and authentic representatives of local opinion.

French colonial ‘fights’ over the next thirty years typically began with efforts by évolué groups to challenge the consequent rigidities of associationism. The techniques of these early opponents varied, although the issues at stake still centred on political rights—admission to citizenship, access to administrative posts, and a wider colonial franchise. Some évolués, like the leaders of Vietnam’s early Communists, despaired of compromise and began organizing labour protests, army mutinies, and peasant rebellion.70 But most chose other, peaceful routes of protest. A common tactic was to highlight the enduring cultural dynamism of colonized societies despite the stifling impact of French cultural dominance which silenced eloquent voices, denied economic opportunity, and withheld basic rights.71 The negritude movement, in particular, disparaged combat, preferring to engage in cultural warfare. Their core argument was simple. The colonial turn towards associationism was a lie. Far from respecting local culture, association presumed that African societies were inferior and inert. The doctrine encouraged venality among the privileged and demanded obedience from the rest.72

Supporters of associationism were undaunted. Their air of confidence mirrored the changes taking place in the training of the inter-war generation of colonial service appointees. A quiet revolution was occurring in the colonial academy. For almost four centuries between France’s early colonial acquisitions in the sixteenth century and the consolidation of the ‘second’ French colonial empire with nineteenth-century conquests in Africa and Indochina, imperial bureaucracy was an adjunct to the administration of the French Navy (or ‘Marine’). Notoriously hostile to republicanism, navy bureaucrats, often of aristocratic or haut bourgeois background, were staunch conservatives in colonial affairs.73 The idea of a specialist colonial service was long resisted and a discrete Ministry of Colonies was only established in March 1894. For decades afterwards, this Ministry, often identified by its Paris location in the rue Oudinot, remained a backwater. On occasion, powerful Ministers, such as Théophile Delcassé (in the mid 1890s), Georges Leygues (1906 to 1909), and Marius Moutet (1936–38) injected vigour to the rue Oudinot. In general terms, though, the Ministry administered rather than governed.

For much of the early twentieth century, policy-making remained the preserve of a loose coalition of empire interest groups, misleadingly labelled the ‘colonial party’. Headed by senior parliamentarians such as Eugène Étienne (before 1914) and Albert Sarraut (after 1918), the colonial party accommodated provincial chambers of commerce, Paris bankers, geographical societies, missionary groups, and senior civil servants. Some were animated by republican conviction, a few by religion; some by specialist academic interest, others by the strategic potential of imperial territories. Most of the bureaucrats and businessmen involved were modernizers. Most of the missionaries, servants of God’s Empire, not of France’s, were the opposite, equating ‘modernity’ with secularism and decadence.74 Yet somehow they all advanced imperial interests. Commerce was especially well represented. Provincial businesses, traders, and shippers with ties to particular colonial markets lobbied for their pet causes. Port cities had much to gain. Built on the Atlantic slave trade, Bordeaux still traded heavily with black Africa. Merchants in Marseilles favoured links with the Maghreb and Middle East. Silk magnates in Lyons relied on assured, cheap supplies from Lebanon and Vietnam much as the Lancashire textile industry depended on Indian cotton.75

High finance was less prominent within the colonial party, except in the lucrative field of French colonial banking, which expanded rapidly after the First World War. Other French speculators looked beyond colonial frontiers for better returns on capital invested abroad. Tsarist Russia was much favoured before 1914; the new states of Eastern Europe more so after the holders of Russian stock lost their shirts in October 1917. Some imperial projects did attract Paris money. The transport sector was a favoured recipient; so was southern Vietnam’s rubber industry.76 Rubber profits made Cochin-China the highest earning French colony per franc invested by the hugely influential Bank of Indochina in the 1920s.77 Railway projects such as an arterial Vietnamese line and inter-city networks in North Africa were the subject of major inter-war loan issues.78 So, too, were colonial air routes and their accompanying infrastructure, which often came with the promise of additional state subsidy. But the Paris Bourse was no City of London when it came to less glossy, day-to-day matters of empire investment and trade.79

With so many rival interests to accommodate, the colonial party could be cacophonous. It was, though, a supremely successful lobby group because its leading members understood the Third Republic’s institutional dynamics. The colonial party set the course of long-term imperial expansion because its members could mobilize Paris bureaucracy, the Catholic orders, employers’ groups, the major banks and, above all, the National Assembly to advance empire interests.80 Rue Oudinot personnel and the short-lived coalition governments that were the Third Republic’s trademark bent to its wishes.

Colonial party supporters were interested in results. They were less concerned with colonial doctrine. Nor were imperialist attachments identifiable with any particular political party of the late Third Republic. All professed loyalty to the Empire; even the Communists, who talked of colonial ‘nations in formation’ under French guidance. But none were sufficiently enthused by it to put imperial claims at the heart of their manifestos.81 Inter-war associationism emerged instead from the confluence of three factors. First was the professionalization of the colonial service. Second was the growing popularity of the social sciences within French academia. And third was the belief shared by bureaucrats and social scientists that ethnography was a uniquely colonial discipline with scientific precepts that would enable officials, not just to administer dependent peoples but to understand them.82

Those individuals who personified all three elements were best placed to put the new thinking into practice. Leading ethnographers boasted extensive colonial experience. Perhaps the most influential, Maurice Delafosse, was a former director of political affairs in the federal government of French West Africa. Another West Africa veteran, Henri Labouret, made ethnography integral to the curriculum of the École Coloniale, the college for trainee empire administrators on the avenue de l’Observatoire in Paris. Delafosse and Labouret persuaded other long-serving officials in French Africa that ethnology and its close cousin social anthropology were bedrocks of successful colonial government.83 Their chief disciple was Georges Hardy, appointed to head the École Coloniale in 1926.84 Hardy’s innovation was to marry these ‘colonial sciences’ with practical courses of instruction—a programme of associationist ideas translatable into administrative practice. Officials trained in Hardy’s methods venerated ethnographic ‘fieldwork’ as a prerequisite for sound policy choices. It was not that simple. Ethnography came loaded with presumptions and prejudices in regard to colonized societies and their limited ability to cope with economic modernization. Industrial diversification, urbanization, and the spread of waged labour were thus interpreted as socially destabilizing, even morally wrong. Puritanical, ascetic Islam was dangerous and ‘un-African’; heterodox Sufism more malleable and tolerant.85 Party politics and European-style jury trial, both predicated on adversarial argument, were, according to Hardy’s graduates, too much for African minds to handle.86 Needs and wants were better articulated through traditional means—customary law (although officials remained hazy about what this was), chiefly courts, and village elders.87 Scientific colonialism, in other words, revealed as much about its practitioners’ beliefs as about those of their colonial subjects.

The number of anthropologists roaming colonial Africa was much smaller than the ranks of agronomists, medical specialists, and engineers that filled the colonial administrations after the Second World War. But the anthropologists were perhaps more influential in determining the actions of governments.88 Specialist officials pointed to ethnographic findings about ‘tribal custom’, local ‘folklore’, and ‘authentic tradition’ to justify colonial tutelage as a work of social conservation.89 No matter that the sheen of academic objectivity legitimized policies that typecast Africans in particular ways, consigning them to a pre-modern status in which industrialization, advanced education, and gender equality became foreign-borne ills to be avoided.90 Others see baser motives in this ‘politics of retraditionalization’.91 Stripped of assimilation’s cultural baggage about remaking colonial societies in the French image, associationism was a turn towards low-cost, high-extraction administration.92 At its heart was the ‘bargain of collaboration’ with local elites—the chiefs, mandarins, and village elders who made the system work. The bargain preserved their titles and limited legal and tax-raising powers. They upheld rural order and furnished the authorities with revenue, labour, and military recruits in return.

It also stored up problems in the longer term. Just as the gap between what assimilation claimed and what it delivered frustrated évolués’ groups, so the bargains with favoured conservative elites that made association work in practice stirred resentment among those who got nothing from the deal. The fault with both doctrines lay in their underlying selectivity more than the ways they were enacted. Imperial rule was neither dictatorial nor hegemonic; there was scope for contestation from the lowest levels of administrative interaction between officials and local peoples to the higher reaches of colonial policy-making. This basic truth applied in the British as in the French empire. Europeans set the tone for administrative, legal, commercial, and religious practice, but colonial bureaucrats, magistrates, traders, and missionaries were rarely able to impose their will without fear of contradiction. French African and Indochinese territories were governed with a more pronounced military presence than neighbouring British dependencies, but the same collaborative propositions applied.93 Cooperation between imperial representatives, local elites, and other indigenous auxiliaries were everywhere to be found.94 Stripped of its rhetorical justifications and doctrinal labels, empire was a system of endless reciprocal arrangements in which insiders, of all ethnicities and creeds, accrued substantial rewards at the expense of the excluded.

The system’s long-term dangers were just as severe in the British Empire as they were in the French. Literacy opened doors to alternate political futures: the thoughts of Gandhi, Marcus Garvey, or Marx as well as new strains of pan-Islamist or pan-Africanist thought. In British-ruled Sudan, for instance, nationalist opposition coalesced among the educated young officials trained as staffers for regional government after the First World War. By 1919 Cairo was a pole of attraction for anti-Western opinion throughout the Arab world. Alarmed by this development, the British administration in Khartoum embarked on a policy of ‘Sudanization’. National dress became de rigueur. Arabic-speaking, Muslim Sudanese of high social rank displaced Egyptians and Lebanese within the effendiyya class that performed most clerical tasks from tax collection to property registration.95 By selecting future Sudanese administrators at Khartoum’s elite Gordon College along lines of language, ethnicity, religion, class, and gender, College staff reinforced the social structures of the pre-colonial period. It was these educated northerners who first articulated clear ideas of the Sudanese nation as a unitary whole with Khartoum as its capital, and colonial provinces plus the vast southern hinterland as its subordinate parts. In the words of Heather Sharkey, these young northern Sudanese became ‘imperialism’s most intimate enemies, making colonial rule a reality while hoping to see it undone’.96 Educated southerners, the product of Christian missionary schools, were, by contrast, frozen out of what would be an Arab-dominated and Arabic-speaking post-colonial state.

Sudan presents the clearest inter-war example of a short-term administrative expedient with unforeseen long-term consequences. In other places colonial violence played a bigger part in determining future political developments. The First World War peace settlements came less than a generation after the concentration camps of Spanish Cuba and the South African War or, more infamously still, General Lothar von Trotha’s campaign of extermination against the Herero and Nama of German South West Africa. And there were few indications that the ultra-violence of ‘pacification’—in Rudyard Kipling’s formulation, the ‘savage wars of peace’—was a thing of the past. During the First World War colonial uprisings in the British Empire (Ireland, Ceylon, Egypt, Waziristan, Iraq) and in the French (Algeria, Niger, Indochina, Morocco) were ruthlessly put down, often by troops acclimatized to exceptionally brutal methods and high casualty rates by their own wartime experiences.97

So it was in the three principal inter-war uprisings in the French Empire: in Morocco and Syria during 1925, and in rural northern Vietnam between 1930 and 1932. Morocco’s Rif War originated in a post-war challenge by Berber clan groups against Spanish and French occupation of the country’s northern margins.98 Fighting between Spanish colonial forces and the foremost Riffian tribal confederations began in 1920. From 12 April 1925, what had been a Spanish-Riffian war became a predominantly French-Riffian one. Three harkas of Riffian forces, together close to 5,000 strong, traversed the boundary separating the Spanish and French Moroccan protectorates. Scores of French garrison blockhouses were overrun within days.99 This was not improvised rebellion but, in Marshal Philippe Pétain’s words, a war fought against ‘the most powerful and best armed enemy we have ever encountered in colonial operations’.100

The French Premier Paul Painlevé told his fellow Senators on 2 July 1925 that the French in Morocco were victims of an unprovoked attack, poor reward for the benefits of modernization and political stability conferred elsewhere by protectorate government.101 He overlooked a critical decision taken by Louis-Hubert Lyautey’s French Moroccan administration a year earlier. French military advance into the Ouergha River Valley, centre of the Rif’s wheat production, threatened to close off food and water supplies to the area’s dominant clans.102 The unprovoked ‘invasion’ of French territory was, in fact, a reoccupation of essential Riffian farmland recently seized by the Protectorate authorities.103 With so much at stake, fighting intensified over the summer. By mid October French official casualty figures recorded 2,176 soldiers killed and 8,297 wounded. Many were North and West African colonial troops. These were the heaviest French military losses since the Armistice and the Rif War would remain the largest engagement by French colonial forces between the wars. With the campaign draining the French Treasury of almost a billion francs, Painlevé’s ministers wanted the war won quickly. Lyautey’s despairing efforts to salvage some measure of collaboration with the Riffians came to nothing.104 Pétain replaced him in Rabat, bringing two additional army corps and the promise of quick victory. A metropolitan army General relatively unfamiliar with imperial soldiering, Pétain began his autumn offensive in late September. Almost 160,000 French troops took part, advancing along the northern Rif frontier.105 That autumn Pétain’s forces brought the tactics of the Western Front—artillery barrages, mustard gas, and infantry assaults—to bear against Riffian clansmen and women.106 The resultant defeat and exile of Mohammed Ben Abdel Krim el-Khattabi was less of a turning point than the means chosen to achieve it. Misleadingly described by Painlevé’s government as a ‘police operation’, the Rif War pointed the way towards the fight strategies adopted by successive French administrations over coming decades to crush anti-colonial opposition.

It was only weeks before the invocation of new leadership, the injection of extra resources, and unrestrained use of overwhelming firepower in Morocco was repeated in French Syria. There, too, the escalatory dynamics of asymmetric colonial repression were equally apparent.107 By December 1925, what had started as a local rebellion among the Druze population of southern Syria against an overbearing French military governor had triggered urban uprisings in Syria’s three largest provincial towns: Homs, Hama, and Aleppo.108 Violence in the countryside was more arbitrary. French irregular forces, substantially composed of Circassian and Kurdish units, destroyed villages and executed men suspected of assisting the rebels. Reprisal killings and the display of corpses in acts of intimidation became commonplace.109

The capital, Damascus, also experienced the full ferocity of pacification after Druze insurgents infiltrated the city’s southern districts. In August 1925 barbed wire and checkpoints went up around the city. These were intended both to keep rebel forces out and to assist security force dragnets against supporters of prominent Damascene families linked to a newly-established nationalist group, the Syrian People’s Party.110 Mass arrests disrupted the Party’s networks but failed to contain the trickle of rebel fighters into the capital. In the pre-dawn hours of 18 October around forty Druze fighters led by Hasan al-Kharrat entered the city’s Shaghur quarter. A police station was set ablaze; troops caught unawares in local brothels were killed. A larger Druze column, joined by scores of Damascene sympathizers, joined the rampage later in the day. The high commissioner’s converted city residence, the ‘Azm Palace, was comprehensively looted. Although tanks and roving columns worked their way towards the rebel force, uncertainty persisted about its size. That evening, General Maurice Gamelin, who would lead the army into the battle for France in 1940, ordered the shelling of the city’s most rebellious districts. Aircraft joined the assault. Civilians, including large numbers of European residents, fled in terror or hid in basements. Certain that rebels were hiding among the tenements but unwilling to send troops in to conduct house-by-house searches, Gamelin stepped up the pressure. The next morning, artillery fired high explosive shells across a wide arc that included the city centre.111 Whole swathes of the capital were in ruins by the time city dignitaries negotiated a ceasefire. The Damascus municipality counted 1,416 dead, among them 336 women and children.112

Such indiscriminate shelling was shocking proof that the minimum force maxims identified with Lyautey’s former Moroccan administration were discredited. France’s premier imperial general returned to France to end his career in a largely honorific role, notably as titular organizer of the enormous Paris Colonial Exhibition that opened in Vincennes in May 1931.

Figure 2. Peace restored? Marshal Lyautey hosts the visit of the Duke and Duchess of York to the Paris Colonial Exhibition in Vincennes. (The Duke is on the Duchess’s right.)

Lyautey’s military successors were never open to compromise. Faced with a powerful incursion, Gamelin in Syria, like Pétain in Morocco, chose devastating force, an option as recklessly inappropriate in the densely-populated inner suburbs of Damascus as it was in the Riffian highlands. Theirs was a policy of annihilation. By the time the much reinforced Levant army moved in to crush the remaining pockets of Syrian resistance in the Jabal Druze and elsewhere in August 1926, the revolt’s original causes were overshadowed by the violence deployed to stamp it out.113 Misguided French efforts to modernize the rural economy and restructure provincial administration contrary to the wishes of local notables might have been remedied.114 Instead, over 100,000 were left homeless, the agricultural economy thrown into recession, and any prospect of dialogue with emergent Syrian nationalism destroyed.115 Perhaps most significantly, the ‘Great Revolt’ passed into popular memory as a heroic lost cause, providing a banner around which otherwise disparate Syrian nationalists could rally in defiance of the French Mandate for the next twenty years.

Nor was there any sign of security force restraint in Indochina, witness to some of the colonial world’s most staggering political violence throughout a tempestuous century of French rule. The causes, costs, and consequences of these clashes have generated an impressive literature.116 Connections have also been made between the flashpoints of inter-war dissent in French-ruled Vietnam during the early 1930s and the outbreak of the Indochina War in 1946. An army mutiny at Yen Bay, a garrison 160 kilometres northwest of Hanoi, and a more sustained peasant uprising between May 1930 and September 1931 in the central Vietnamese provinces of Nghe-An and Ha-Tinh, known retrospectively as the Nghe-Tinh soviet movement, have each been read as indicators of a militant nationalism partly inspired by Vietnamese cultural renovation, partly by Communist ideology.117 The local severity of the Depression also played its part. Communist leader Ho Chi Minh and Phan Bội Châu, founder of the Duy Tân Hôi (Vietnam Reformation Society) and his country’s leading nationalist exile, were each natives of Nghe-An.118 Poverty nourished Nghe-An’s radical tradition. Poor and densely populated, the provincial capital, Vinh, and its outlying farming districts were acutely susceptible to adverse changes in the region’s agricultural market. A combination of low-yield land, drought conditions, and repeated harvest failure caused widespread peasant malnutrition.119 But these economic factors were ignored by the colonial administration, which treated dissent almost as an environmental condition, something intrinsic to Vietnam and its people, rather than a phenomenon generated by the political economy of colonialism.120 Depicting Vietnam as inherently lawless absolved the authorities of responsibility for social unrest and it normalized the resort to harsh repression within a society allegedly accustomed to the language of violence: legal distinctions between the killing of civilians and the eradication of insurgents collapsed.121

Guided by local militiamen, Foreign Legion units led the crackdown after Yen Bay.122 Their prime targets were the supporters of two main groups: Vietnam’s nationalist party, the Viêt Nam Quôc Dân Dang (VNQDD) and its new rival, the Indochinese Communist Party (ICP). In practice, army violence was arbitrary and judicial retribution severe. On 17 June 1930 thirteen VNQDD members, including party leader Nguyen Thai Hoc, were escorted to Yen Bay for execution by guillotine.123 The event was concealed from public view to minimize the risk of creating martyrs to the nationalist cause.124 But the French Communist Party newspaper, L’Humanité, broke ranks. It reproduced the statements made by the condemned and graphically recounted their struggling as Foreign Legionnaires forced the men onto the chopping block. Literally decapitated, the VNQDD declined as a political force, leaving the way open for Communist resurgence in the later 1930s. The executed VNQDD leaders did not figure within official casualty figures for the nine-month period, February to October 1930, which listed 345 rebels killed, 124 wounded, and 429 arrested. Government forces, by contrast, came away unscathed.125

On 10 April 1930, several weeks after the original mutiny at Yen Bay, the Chamber of Deputies finally debated the situation in Indochina. Socialist Deputy Marius Moutet dominated the proceedings. A Lyons lawyer and a committed pacifist, Moutet was an eloquent critic of judicial abuses in the empire. Outside Parliament he used his position within the League for the Rights of Man (La Ligue des Droits de l’Homme, LDH), the most influential human rights lobby in France, and its associated committee for the defence of political prisoners, to condemn French actions in northern Vietnam.126 Moutet’s preoccupation with colonial affairs was unusual among LDH members, whose journal described colonial subjects in pejorative, sometimes racist terms.127 Queasy about colonial oppression, the League still defended republican imperialism as a force for good.128

So Moutet’s was rather a lone voice. He railed against the mockery of French justice as the colonial authorities imposed control, pointing out that a specially-convened criminal commission in Tonkin (Vietnam’s northernmost territory) passed fifty-two death sentences on Yen Bay mutineers. Another special criminal court in Saigon handed down an additional thirty-four death sentences in under twenty-four hours.129 Only the poet Louis Aragon, a founder of the surrealist movement and an organizer of the militantly anti-colonial ‘Red Front’, was as vociferous in denouncing this fight strategy run wild.130 For all their efforts, few beyond the margins of the extreme left and Paris Bohemia seemed to be listening.

Step forward five years to Fascist Italy’s invasion of Haile Selassie’s Ethiopia in late 1935. It was then that sixteen members of the Académie Française, France’s most prestigious academic body, issued an ‘Intellectuals’ manifesto for the defence of the West’. The signatories were all authoritarian right-wingers. Among them were Charles Maurras, father-figure of the ultra-rightist ‘Leagues’ like the Croix de feu (Cross of fire), whose members took to the streets in their thousands during in the 1930s, and Robert Brasillach, a future collaborationist executed for treason in 1945. Their 1935 manifesto was an unabashed defence of European colonial domination. It mocked ‘a false legal universalism which sets the superior and the inferior, the civilized person and the barbarian, on the same equal footing’. The ‘Intellectuals’ manifesto’ provoked outrage from French liberals, Moutet and his LDH colleagues among them. But the fact remained that less than five years before the Second World War the ‘right’ of European nations to rule ‘lesser’ societies remained dogmatically self-evident to other prominent French commentators.131

To a degree, British inter-war techniques of repression mirrored those of France. General Reginald Dyer’s decision to order imperial troops to fire on hundreds of civilian protesters at Amritsar on 13 April 1919 confirms that extreme state violence was by no means confined to French colonies.132 General Dyer conceived his task in Amritsar as a military operation against a hostile population in ‘enemy territory’.133 It was a view that won him considerable support in Britain, where his defenders maintained that his unscrupulousness stamped out an incipient revolt.134 A decade later in Burma a rural uprising, the Saya San rebellion, which was embraced by members of Burma’s proto-nationalist movement during 1930–31, was suppressed with the same ruthless, exemplary violence as used against the Yen Bay mutineers in northern Vietnam.135 Elsewhere, sources of British colonial dissent were rather different. Palestine stood out in this regard. Its disputes were written in Britain’s conflicting wartime promises to Arab and Jewish leaders. Never during the mandate’s sorry twenty-eight year history did Palestine’s British rulers reconcile their contradictory commitments to a Jewish national home and protection of Palestinians’ rights as charges of the League of Nations. By 1937, sub-dividing Palestine between Arabs and Jews, something dismissed by British politicians of all stripes in the 1920s as an admission of imperial failure, had acquired the dismal respectability of the last resort solution. Partition became policy, its planned outlines evident in Map 4. Perhaps because Britain’s Palestine problems were self-inflicted, its administrators excelled other British colonial bureaucrats in expressing their frustration.136 Jerusalem High Commissioner Sir Ronald Storrs was among those exasperated by the challenges of communal impartiality: ‘Two hours of Arab grievances drive me into the synagogue, while after an intensive course of Zionist propaganda, I am prepared to embrace Islam.’137

Map 4. The British Mandate in Palestine.

Storrs’ cynicism is easily explained. Neither he nor his successors could dampen Palestine’s inter-communal friction. Indeed, the combination of early 1930s depression conditions, rising Jewish immigration from Europe, and intensified competition over land, property, and religious observance made it worse. Sickening outbursts of internecine violence proliferated.138 From the early 1920s to the late 1930s riots along communal frontlines in Jaffa, Hebron, Nablus, and, above all, Jerusalem, culminated in orgies of killing.139 Fearful about accusations of partiality and betrayal of trust, successive British Cabinets turned to the final expedient for a cornered government: a decorous Royal Commission to conduct a judicial investigation and offer advice on lessons learnt.140 One such commission of inquiry into the worst of these clashes, the Wailing Wall riots of August 1929, recorded 133 Jews and 116 Arabs killed with a further 572 seriously injured.141 The Mandate’s security forces, reliant on local paramilitaries and targeted by rebel groups from both communities, became caught up in the cycle of killings and counter-killings. Increasingly brutal, Palestine’s police and the British army garrison were a hated occupation force by the time full-scale Arab revolt erupted in early 1936.142

Even a temporary ceasefire in October 1936 only highlighted the limits to British influence. Negotiated in part to facilitate Palestine’s all-important citrus harvest, in part to offset demands for martial law, the ceasefire underscored the ability of the Palestinian Arab leadership to orchestrate the violence. As General Sir John Dill, recently dispatched to suppress the revolt, commented, ‘I regard the most disturbing side of the situation as being the demonstration of power which the Arab Higher Committee has given in calling off the rebellion so completely and so quickly—by a word.’143 The cycle of killings and retribution would resume in 1937. British security forces began manipulating the law to justify a savage policy of counter-terror against Palestinian civilians.144 This time it was the British public that did not seem to care.

Liberal leftists throughout Europe were drawn to the against-the-odds bravery of the anti-fascist international brigades in the Spanish Civil War. Left-leaning anti-colonial nationalists like Algeria’s People’s Party (Parti du Peuple Algérien) or the Indian National Congress also professed their opposition to fascism while stressing the double standards of European Socialists who did little about colonial oppression. In February 1938 Jawaharlal Nehru, for one, criticized the ‘curious and comforting delusion’ among Labour leaders who presumed that resisting fascism could be accomplished without freeing India.145 According to this logic, the Labour leadership brushed the moral equivalence between anti-fascism and anti-colonialism under the carpet. Certainly, no British politicians looked favourably on the Palestinian peasant insurgents who resisted Mandate rule in precisely the same three-year period of 1936 to 1939 that witnessed the death of Republican Spain.146 This elision of memory is typified by the figure of Shaykh ‘Izz al-Dîn al-Qassâm, a Syrian-born Haifa imam and insurgent organizer who became the hero of the Palestinian Revolt after he was shot dead by police in November 1935. His tomb in the village graveyard of Balad al-Shaykh has since been repeatedly vandalized, a reminder that the village’s 5,000 Palestinian inhabitants fled their homes in the first wave of Jewish Haganah attacks during the 1948 Arab-Israeli war in April 1948. Balad al-Shaykh is now subsumed within an Israeli township, its name, like its original residents, long since replaced.147

Figure 3. Minimum force? The Palestine Police, actually a paramilitary force, take to the streets during January 1936 riots in Jaffa.

As for the rebellion that Qassâm helped inspire, its failure is usually ascribed to factionalism among rebel bands faced with superior British and Jewish paramilitary firepower and intelligence-gathering capability.148 There is some truth in this depiction. During the opening months of the rebellion in 1936–37 insurgent bands typically coalesced at village level, without wider ‘national’ coordination or command.149 There was a logic to this, however. Rooted in their local community, insurgents were better placed to recruit supporters, to maintain their supplies, to hide when necessary and, most important, to establish alternate structures of local administration. Far from being the ‘criminals’ or ‘outlaws’ depicted in British propaganda or subsequent Zionist accounts, Palestinian rebel groups adhered to a strict moral economy in which careful target selection, the protection of loyalist villagers, and the redistribution of land to those who served the rebel cause was integral to their capacity to operate at all. Ultimately, however, rebel efforts to sustain the rhythm of revolt were undone by brutal British military tactics of aerial bombing, collective punishments, destruction of Palestinian property, and systematic torture of detainees. Destroying a farmstead, cutting down citrus and olive orchards, or pouring oil over a family’s winter store of cereals and pulses were acts of violence as ruthlessly effective as beating prisoners to extract information.150

The Palestine Revolt drove Neville Chamberlain’s government to adopt that most bastardized of flight strategies: partition as the prelude to withdrawal. Improvised and unpopular, especially within the Jewish community, the 1939 partition plan bore the seeds of renewed post-war conflict.151 In the event, the Government’s May 1939 White Paper subdividing the Mandate into Jewish and Arab mini-states was overtaken by the war. But the essence of British thinking was clear enough. Palestine was a net liability.152

Sustaining British political influence elsewhere in the inter-war Middle East proved only marginally less troublesome. Collusion with monarchical elites, cajoling of their nationalist opponents, and outwardly generous concessions—mock independence for Egypt in 1922, a similar arrangement with Iraq in 1932, and a Suez defence treaty in 1936—were expedient but fundamentally duplicitous. In one of its first acts in office, Ramsay MacDonald’s second Labour government confirmed in September 1929 that Iraq should pass from Colonial Office to Foreign Office control. The signal would go out home and abroad that Britain recognized Iraqi statehood, while imperial interests could be upheld through partnership.153 These political tactics amounted to what we might usefully think of as ‘pre-flight’: the backstairs dealing that, for the most part, conserved British strategic and economic interest through negotiation backed by the threat of force, rather than its actual use. Take, for example, the royal succession crisis of 1936, not in Britain, but in Egypt. There, the death of King Fuad in April cleared a path for Wafdist leader Mustafa al-Nahas to advance nationalist interests at the expense of the monarchy’s conservative supporters and their British backers. In the event, High Commissioner Sir Miles Lampson’s badgering of Wafdist politicians and his choosing to support Fuad’s sixteen-year-old successor, King Farouk, kept negotiations for the Anglo-Egyptian treaty (signed in August) on track. The fiction of peaceful co-existence with Wafdist nationalism survived.154

Lampson pursued the same tactics as his predecessor, Sir Percy Loraine. Both preserved the appearance of cooperation with Britain’s long-standing allies among Egypt’s royalist elite while bargaining with their natural opponents in the Wafd. The resultant treaty was a compromise, subject to later renegotiation at what probably seemed a distant and not particularly significant date: 1956. One thing that the 1930s negotiators on both sides did realize was that each would try to strengthen their position at the other’s expense in the intervening twenty years. This was implicit in the 1936 treaty bargain that the two High Commissioners helped to strike. Britain might have secured a more advantageous deal with previous Egyptian governments, but, in signing a treaty with Wafdist support, it co-opted the group otherwise bound to oppose it.155 This was British imperial diplomacy inter-war style. In place of the gunboats of old, more subtle pressure was applied. As if to make the point, the young Farouk, who had been studying at the Woolwich Military Academy, travelled home to Egypt aboard an ordinary passenger liner, P&O’s Viceroy of India—but with the cruiser HMS Ajax providing a Mediterranean escort.156

The image of benign, restrained intervention was equally cultivated in other British territories where client rulers remained in place. A March 1931 letter written by a deputy of Sir Cecil Clementi, Governor of Malaya, while his boss was back in London conveyed the unflappable calm so beloved by British colonial officials. It began dismissively by telling Clementi that there was no news ‘of sufficient interest to bother you with’ while on leave. Of Malaya’s component states, Johore had been ‘jogging along quietly except for a little Communist trouble in the Muar District’, while Trengganu was ‘financially on the rocks’. Yet, these were mere asides. The sole newsworthy item was that in Brunei ‘the Sultan’s mother has been making rather a nuisance of herself’.157

Before the Japanese invasion in 1941 colonial Malaya had some claim to be genuinely multicultural. The growth of English educational curricula and elite, but ethnically-mixed schools informed their Malay, Chinese, and Indian pupils with a shared sense of Britishness. Beyond the school gate, increasing consumerism also made for fluid identities yet to crystallize into the sharper communal divides associated with Malaya during the post-war Emergency. By 1931 Singapore’s population had risen to over half a million, making it Southeast Asia’s largest and most cosmopolitan city. There, as on the neighbouring Malayan Peninsula, nationalist sentiment was weak; overseas ties of ethnicity, commerce, and culture commensurately strong.158

The picture in another multi-ethnic British colony—Kenya—could hardly have been more different. In October 1936, the Conservative colonial secretary William Ormsby-Gore wrote to Air Chief Marshal Sir Robert Brooke-Popham to offer him the Kenya governorship. With Italy’s bloody takeover of Ethiopia still unfolding, it seemed vital to have a dependable appointee in Nairobi’s Government House. The job was a tough one. At least four of Kenya’s previous governors had departed prematurely, usually after clashing with the colony’s implacable settlers. Ever since the Colonial Office ‘Devonshire Declaration’ of 1923 (pejoratively labelled the ‘Devonshire fudge’) affirmed that Kenya was ‘primarily’ African and unsuited for white ‘self-rule’, the colony’s settlers viewed Westminster edicts with poisonous disdain.159 There was more to this than the resentment of the pioneer for the interfering bureaucrat. The Great War destabilized minds as well as empires, communities and families. As Patricia Lorcin, a sharp analyst of women settlers’ writing, notes, the’14–’18 War undermined the rock-solid belief in the excellence of European civilization and the advantages of social modernity. And it broke many of the ties between settler societies and their home governments. Elspeth Huxley, writing in 1935, almost a generation after the armistice, captured the point in her otherwise laudatory biography of Lord Delamere, the champion of white settlement in Kenya: ‘Behind the almost fanatical manner in which many African questions are approached today lurks the feeling that we who so obviously and tragically fail to manage our own affairs in Europe should not meddle in Africa.’160

Ormsby-Gore admitted that Kenya was acutely divided between ‘the very vocal British settlers, mostly of the ex-officer and public school class, a large Indian middle class of traders, artisans and some lawyers, and three million African natives of the most heterogeneous types in any colony in Africa’. Yet it remained, ‘a country people fall in love with and acquire an emotional rather than a strictly rational attitude toward—a paradise of big game with superb scenery, but bristling with “problems” and controversies, many of them arising from the fact that at 6,000 feet above sea level on the Equator everyone wants to run before they can walk in an atmosphere which doesn’t permit of quite such strenuous exercise.’ The colony, he thought, ‘wants somebody who is a good mixer, has plenty of self-reliance, and a sense of humour quite as much as an energetic administrator … I know it well enough to know that it is a “man’s” job.’161 Suitably flattered, Brooke-Popham was in Nairobi six months later. His ‘self-reliance’ was soon tested, neither by the Kikuyu nor by his unwelcome Italian neighbours, but by settler opposition to any whisper of reform.162 The irony was that land policy, taxation, and social spending served settler requirements. Official reluctance—or inability—to tackle these structural problems before the war stored up African resentments that would emerge with more strength and political coherence after it.

The notion of an ‘inter-war period’ makes sense for the two imperial powers. In France and Britain the war just ended and the next to come combined proud accomplishments with dreadful memories, proximate threats with reluctance to countenance another conflagration. Europe’s conflicts weighed less heavily than other factors in the lives of colonial peoples. Economics was perhaps paramount. Structural poverty in some places, in others, the alternation between boom and bust as raw material prices rose and fell affected levels of political engagement and dissent to a greater extent than the cultural resentments precipitated by specific colonial policies. To sustain political control in their inter-war empires France and Britain followed similar colonial paths of low-level coercion, occasional, ruthless repression, and concessions to local elites identified as empire loyalists. Yet their differing trajectories of fight or flight, admittedly more apparent after the Second World War than before it, were nonetheless evident in their contrasting ideas about the purposes served by empire and the ways in which these ideas informed their colonial actions.163 How would the impending war change things for rulers and ruled?