HOW THE SHALE REVOLUTION IS CHANGING EVERYTHING

The American Energy Revolution

As recently as the 1970s and early 1980s, major oil and gas companies and large independents dominated the domestic energy landscape. The “majors” or “Big Oil,” as they are called, subsequently abandoned the domestic basins in search of larger finds internationally.1 In their absence, individual oilmen in small and mid-sized U.S. companies launched an energy revolution that has changed the world in less than a decade.

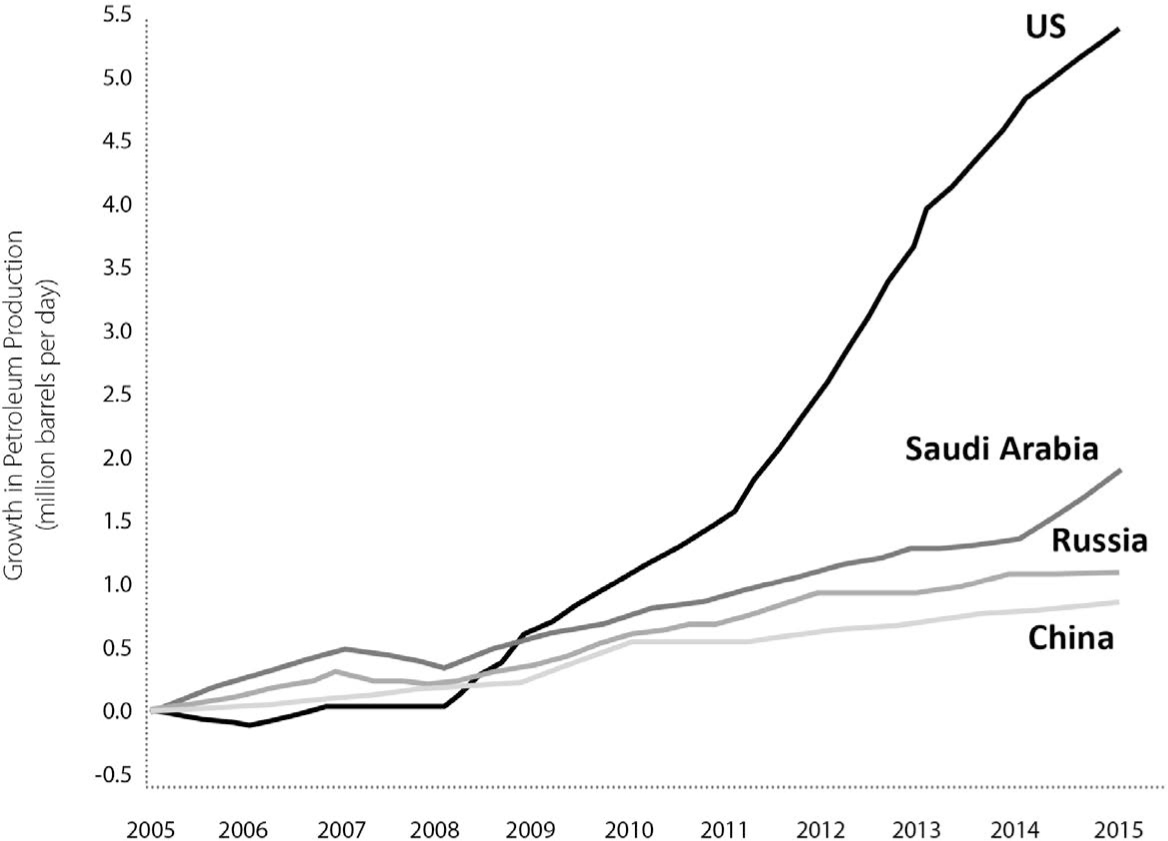

After decades of declining production and dependence on imports for almost 70 percent of its oil and natural gas, the United States surpassed Saudi Arabia and Russia to become the world’s number one energy producer (measured in barrels-of-oil equivalent) in 2013 and remains so today.2 Imports of petroleum to the United States decreased almost 60 percent from 2007 to 2013.3 Domestic oil production rose from five million barrels a day in 2007 to 8.6 million barrels a day in 2014—a 40 percent increase in seven years. In May 2015, production reached 9.6 million barrels a day even with a plunge in the price of crude oil. Russia and Saudi Arabia lead us in crude oil production by little more than a million barrels per day, a negligible amount. See Figure 2.1. The United States has also doubled its export of petroleum products to a hefty one billion barrels per year.4 This historic upsurge, achieved in less than a decade, owes almost nothing to federal energy policy (in fact federal energy policy has tried to slow down domestic oil production) or the majors, and few Americans are even aware that this colossal energy breakthrough has taken place.

Determined, creative, courageous men and women competing in a free market achieved what seven presidents promised but failed to achieve—making the United States the world’s energy superpower, no longer unavoidably dependent on oil imports from countries hostile to our fundamental values of individual liberty and economic freedom.

FIGURE 2.1

Growth in Output of Major Oil Producers

Source: U.S. Energy Information Administration

Strangely enough, the energy bonanza has coincided with the presidency of a man hell-bent on eliminating fossil fuels to avert alleged global warming. If Barack Obama has an energy policy, it is to “decarbonize” our economy and “lead the world” to a global agreement to “save the planet” by ditching the use of the hydrocarbon bounty of American energy. Our geopolitical foes in Russia, the Middle East, and South America derive most of their revenue from the sale of oil and natural gas. Yet after more than eighteen years without warming global temperatures, the president seeks to increase our dependence on these thuggish regimes and declares that global warming is a greater threat than ISIS.

The cause of the extraordinary rise in U.S. energy production has been the shale boom, an American technological revolution that has unlocked oceans of previously inaccessible oil and natural gas, combined with competitive markets, economic freedom, and property rights. A mix of innovative technologies developed by dogged engineers and adventurous investors has released vast volumes of oil and natural gas trapped in hard shale rock. Through hydraulic fracturing, horizontal drilling, seismic imaging, and deep-data geophysical analytics, U.S. producers cracked the shale energy code and are transforming the world’s energy markets.

The shale boom has enlarged the economic pie, offering prosperity to every American. It kept the Great Recession from becoming the Great Depression 2.0 and turned multitudes of small, rural mineral-rights owners into millionaires. Local, state, and federal government have seen revenues soar. Hundreds of related industries are expanding or opening new plants, creating good new jobs. Recent studies estimate that more than $100 billion has already been invested in new chemical, plastic, and fertilizer plants and related manufacturing in the United States.5

Low energy prices give American manufacturing plants a powerful advantage over foreign competitors that must cope with energy prices two to four times higher than in America. And low energy prices may have increased disposable income by an average of $1,200 per household in 2014.6

America’s energy endowment is even more impressive when you take coal into account. Called the Saudi Arabia of coal, the United States holds 481 billion tons of coal reserves—the largest in the world. The lower forty-eight states have enough coal to meet current demand for 520 years. Alaska has even larger reserves that have not yet been tapped.7

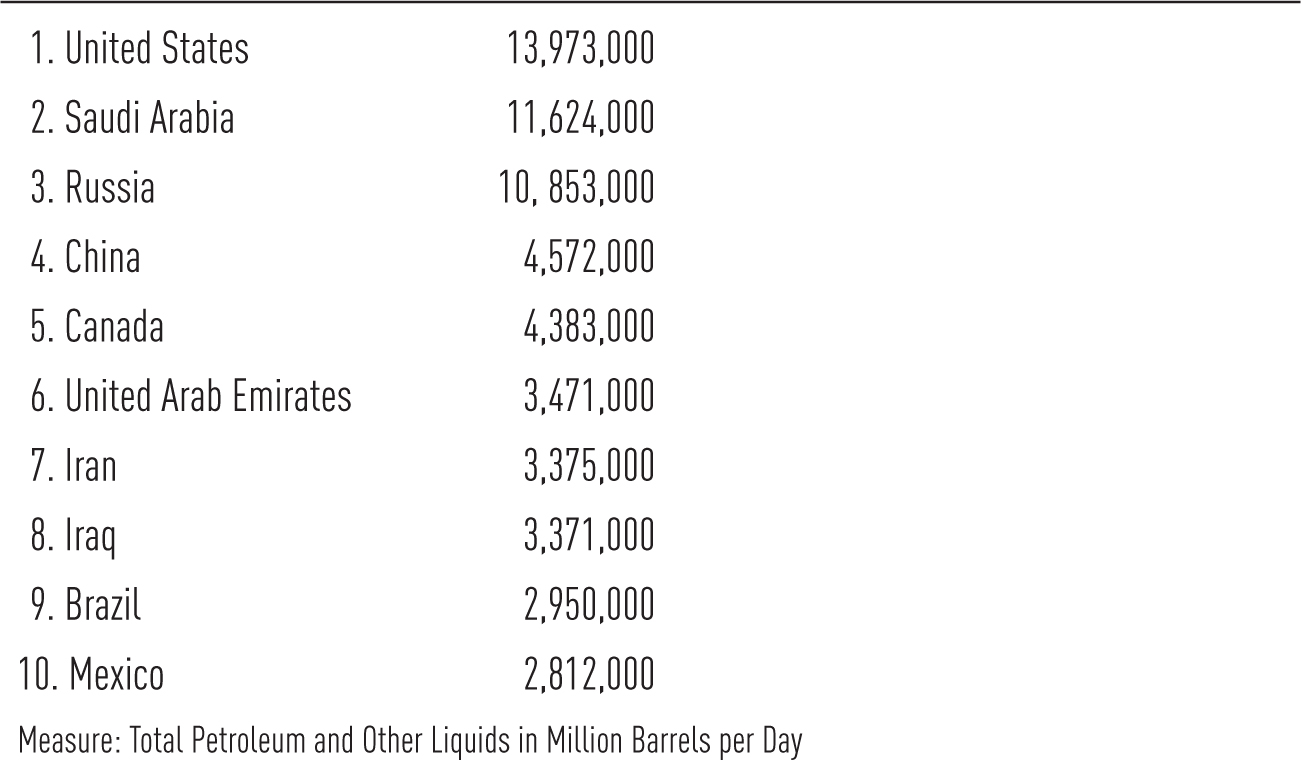

These natural resources are an incalculable blessing to America. Wise use and free trade of our abundant energy could eliminate our reliance on corrupt and dangerous countries for oil. Among the top ten energy-producing countries, only the United States and Canada are constitutionally committed to the dignity of the human person (see Figure 2.2). By contrast, several of the biggest oil producers use their revenue from oil sales to fund terrorism.

FIGURE 2.2

Ten Top Oil-Producing Countries in 2014

(EIA International Energy Statistics)

The Canadian journalist Ezra Levant has written provocatively about the ethical issues surrounding the development of Canada’s oil sands8—issues debated within Canada and across the world.9 The “real test of ethical oil,” he argues, is not “comparing oil sands to some impossible, ideal standard but comparing it to its real competitors.” American and Canadian oil is produced with far higher environmental sensitivity by countries that are “more peaceful, more democratic and more fair” than the other major oil-producing nations.

If the North American energy revolution had occurred thirty years earlier or if the federal government had not shackled domestic energy production, we might have avoided today’s protracted, fractious, and deadly entanglements with the Middle East. And the United States could, right now, be exporting oil, natural gas, and coal to our free-world allies held hostage to high-priced Russian energy. We know that ISIS terrorist networks are funded to the tune of $1 million a day through oil dollars.

In late 2015 Congress finally repealed the outdated ban on exporting domestically produced oil, promising a tremendous boost to the American energy industry. Congress created the export ban in 1973 when the Arab Oil Embargo drove gasoline prices sky high and created temporary scarcity at filling stations across the country. Since then we have gone from scarcity to glut. Multiple federal studies conclude domestic exports will not increase consumer prices and will likely have the opposite effect.10 Other studies find that this policy change alone will increase domestic oil and gas output by at least $100 billion a year.

The shale boom should renew our faith in free enterprise. This country’s thousands of small and mid-sized energy companies—the independent, successful, and peaceful army of the U.S. shale revolution—have proved that the American dream is still alive.

Before taking a closer look at the shale boom and the opportunities this energy bonanza creates for our country, consider the human faces of America’s colossal energy resurgence.

Economic Heroes of the Century: The American Energy Entrepreneurs

George Mitchell

Although many contributed to the shale boom, George Mitchell of Galveston, Texas, is widely regarded as the “Father of Fracking.” Born in 1919 to Greek immigrants (his father changed the family surname, Paraskevopoulus, to Mitchell), he and his family lived above their shoeshine parlor and laundry.

Mitchell worked his way through Texas A&M University and graduated first in his class in petroleum engineering. The classic independent Texas oilman, he won big, lost big, and then won big again, drilling perhaps ten thousand wells before selling Mitchell Energy to Devon Energy not long before his death at ninety-four in 2013.

As early as the 1950s, Mitchell was focused—his colleagues might say “fixated”—on the natural gas in the geological formation now known as the Barnett Shale, underneath the Dallas–Fort Worth region. He realized that his conventional drilling was extracting only a minute portion of the gas he sensed was trapped in hard rock. Mitchell vertically fracked the first well in the Barnett Shale in June 1982, but the output was slim and the drilling cost high. Convinced that vast reserves of natural gas were down there, he continued to frack a few wells every year with different techniques. Most people who knew him thought he was obsessed with an irresolvable, extremely expensive puzzle.

The technology of “fracking”—making small fissures in hard rock to allow the release of oil and natural gas—goes back seven decades. Floyd Farris of Stanolin Energy received a patent in 1948 for a technique he called “HydraFrac.” After years of expensive trial and error, Mitchell Energy cracked the Barnett Shale with a similar but yet decisively refined fracking technology in 1998. Instead of fracturing a well with heavy gelatinous fluids and loads of chemicals, Mitchell used lots of water under extremely high pressure and then used sand to prop open the fissures. Mitchell Energy had figured out how to release the natural gas held in shale rock, and the United States now sat atop a massive store of accessible energy.

In 2002, Devon Energy drilled its first horizontal well into the Barnett Shale, producing seven times more natural gas than conventional drilling techniques. In the early days of the boom, the effectiveness of the technology was a shock even to longtime insiders of the oil and gas business. Many oil men and their engineers shook their heads when they heard of Devon’s success. Shale rock, in contrast to softer, more porous sandstone, was so hard that it was thought to be impermeable. Reaching the oil and gas trapped in shale, a seasoned engineer noted, was “just as startling as saying that ice doesn’t freeze anymore.”11

By 2012 the majority of wells in the United States were horizontal, and production in the shale fields had increased dramatically. The early wells were extremely expensive, and even today many horizontal wells are considerably more expensive than traditional vertical wells. Yet nimble independent energy companies are rapidly cutting the cost of production while increasing the output.

Bud Brigham

“The Bakken boom in North Dakota more than doubled in size on September 7, 2008, the day the U.S. housing market crashed and a deep economic recession began.”12 That was the day Brigham Exploration, founded and run by Bud Brigham, began fracking in the Bakken shale fields of North Dakota. Brigham was the first to drill a much longer horizontal well bore, extending the lateral scope of a well from one to two miles. In principle, this should almost double the productivity of a single well.

In a daring move, Brigham then deployed a new tool, developed by the independent oil company EOG, called swell packers. This technology was enormously expensive—it required Brigham to take on considerable debt at a moment when Wall Street was crashing—but promised to double the length of prior wells and thus dramatically improve the economics in the play. The technologies Brigham applied would set a record for the number of sections of the well that could be fractured. He was gambling $8 million on the well, with considerable debt, at a moment when substantial portions of Wall Street were crashing. Brigham’s well was successful and dramatically amplified the amount of oil and natural gas extractable from a single well, eventually doubling the geographic extent of the Bakken field.

Harold Hamm

The founder and CEO of Continental Resources, the fourteenth-largest oil company in the country, Harold Hamm owns more oil and natural gas reserves in America than anyone else in the industry. The youngest of thirteen children and “the son of [Oklahoma] sharecroppers who never owned land,” he headed straight to the oil fields after high school.

Harold Hamm is credited with discovering the magnitude of the Bakken shale fields. One of the first players in the Bakken, as early as in 2002, he gathered up a substantial majority of the region’s prime oil leases. His application of various fracking technologies to many wells allowed innovation that increased productivity and cut costs.

Through several boom and bust cycles, Hamm made billions of dollars during the boom years 2006–2014, when oil prices were $80 to $100 a barrel. But even with oil below $50 a barrel, he is still making money. Everywhere he drills, Harold Hamm finds more oil.

Jim Henry

Another trailblazer in the improbable shale revolution is Jim Henry from Midland, Texas. Humble, gracious, and generous, he is revered throughout the upstream oil and gas business and within his community. He is also an extraordinarily savvy and dynamic oilman. A forty-five-year veteran of the oil business and owner of a succession of small, independent companies, Henry led the vigorous and sustained revival of the historically prolific but long moribund Permian Basin oil fields of west Texas.

Observing the increasing success of Mitchell’s fracking technologies with natural gas in the Barnett Shale region, several big oil companies experimented with these technologies in the Wolfcamp geological formation in the Permian in the late 1990s. Production there was difficult and the results were modest, and they departed by 2000. Henry was able to take over some of their oil leases, and he applied a version of Mitchell’s drilling techniques near the area where the bigger companies previously had drilled. In 2003, Henry’s Kaitlin 2801 well was successful. He then moved seventeen miles south and succeeded again. At that point he knew he had discovered a huge field where many more wells could be drilled, and he quietly gathered up oil leases on three hundred thousand acres in the Wolfcamp formation.

Since the first producing well in 1920, the Permian has produced 28.9 billion barrels of oil and eighteen trillion cubic feet of gas.13 Because of Henry’s breakthroughs, those numbers likely represent only a small portion of the oil and natural gas now recoverable in a field previously thought to have peaked in 1973.

Henry emphasizes that vertical fracking in the Permian recovered only about 3 percent of the oil “in place,” that is, remaining within the geological formation. Horizontal drilling increases recovery to about 7 percent of the oil in place. The Permian Basin may have doubled its oil output within the past several years, but 93 percent of the mother lode of oil in the Permian is still in the ground. Increased production merely awaits another of the drilling innovations that distinguish the shale revolution. Sustainable oil, anyone?

Henry himself was once persuaded by the “peak oil” theories of irreversible and near-term depletion of oil resources. But that theory “went out the window,” as he puts it, when George Mitchell’s hydraulic fracturing “did the impossible” and successfully drilled through apparently impermeable shale to release the oil and natural gas from the source rock itself.14 (See Sidebar on page 37, “The Shale Energy Transformation.”) Never say never, Henry learned. Through fracking, the energy output from the Permian Basin rose from 850,000 barrels per day in 2007 to over two million barrels per day in July 2015.15

The history of U.S. oil production is marked by booms and busts, but the increase in oil production from shale is unlike previous, temporary booms caused by favorable economics. The shale upsurge is a true revolution driven by new drilling technology, imaging, and data access on a scale and at a speed that are dizzying to insiders.

The revived Permian Basin accounts for two-thirds of all oil produced in Texas and more than 18 percent of total U.S. production. Output there continues to soar in spite of the plunge in oil prices and a steep drop in the number of drilling rigs in the fields. During a period of low oil prices, more output from fewer rigs indicates the increasing productivity and the declining cost of production in select wells.16

The shale revolution, Henry points out, was a far more collaborative project than were previous booms. Producers shared information and techniques that increased productivity and decreased drilling costs rather than rushing to get patents. Company owners, employees, geologists, engineers, drillers, and the many service companies essential to upstream oil and gas “feel that we are in this together,” says Henry, and there is enough potential growth for all participants in the industry to thrive.

Who would have predicted that the resurgence of domestic oil production—and especially the revitalization of the mighty Permian fields—would be the result of risky, complex innovations of small oil companies? Henry’s workforce peaked at around 120 at the height of his Wolfcamp activity, but most of the time his staff has not exceeded forty. Exxon-Mobil, by contrast, has 83,600 employees. There is nothing wrong with huge corporations operating on a global scale. Small companies, however, are often the source of innovation and motivation that are difficult to replicate on a giant scale. Jim Henry’s story shows what small businesses, economic freedom, property rights, financial incentive, and innovation can achieve. And the legal institutions and culture of the United States are unmatched in fostering this powerful and creative engine of economic growth.

The shale revolution was the work of small to medium-sized companies operating on private and state lands. The United States is fortunate not to have a nationally owned oil company, as do the members of the Organization of the Petroleum Exporting Countries. But production on federally owned land has remained anemic—not for lack of recoverable energy underground but because of regulatory interference.

The Shale Energy Transformation

The oil and gas extracted in the shale fields began as small aquatic organisms in an ancient inland sea covering the central region of North America from the Great Plains to what we now call Pennsylvania. And by an ancient inland sea, we mean ancient—formed sixty million years ago, during the Cretaceous Period. Historical geologists conclude that the sea was formed when a collision of the earth’s tectonic plates gave rise to the Rocky Mountains in the west and the Appalachians in the east. When the marine creatures living in the inland sea died, they settled to the seabed and over time formed layers of organic material. Rocks eventually covered this material. The pressure from the rocks generated heat for millions of years, transforming the organic sludge into hydrocarbons otherwise known as crude oil and natural gas. The shale of the shale revolution is what petroleum geologists call the “source rock” of oil and gas, a kind of cradle in which the hydrocarbons are generated and stored in rock.

Today’s refined fracking technologies speed up this natural geological process by millions of years. The minerals extracted in conventional vertically drilled wells are the hydrocarbons that eventually seeped from source rocks over millions of years and collected in pools. When vertically drilled, natural geological pressure helps move the contents of that reservoir to the surface. Geologists have known for decades that natural pressure may produce far less than 10 percent of the oil or natural gas in the particular geological formation that created the pool. The shale boom aims at the remaining 90 percent.

These men and many others did far more than Barack Obama or any politician or economist in Washington to bring about the 2009–2015 economic recovery. The $830 billion federal spending, borrowing, and subsidizing binge known as the American Recovery and Reinvestment Act of 2009 had nothing to do with it. The real economic stimulus has been the risk-taking oil and gas companies that launched and drove the shale revolution.

The New Energy Superpower

The shale revolution received a blow when oil prices began a plunge in June 2014. A year later half the drilling rigs had left the shale fields and over a hundred thousand jobs had disappeared. Yet the prodigious productivity—more than 9.5 million barrels a day in March 2016—and increasing global influence of U.S. oil survived.

The domestic shale industry has been a victim of its own success: producing so much oil that it glutted global markets just as China’s economy began to sag. When the surplus recedes, the price of oil is likely to stabilize now that the outdated ban on exports of crude oil has been lifted. Great Britain and Japan already have indicated an interest in importing oil from the United States. Meanwhile, critical masses of shale drillers are rapidly reducing the cost of production while increasing their output.

“OPEC’s Clout Hits New Low,” the Wall Street Journal reported in the summer of 2015.17 The cartel’s market share had declined from more than half of global production to roughly one-third of global production.18 The bulk of OPEC’s loss of market share is attributable to American shale oil, which accounts for 75 percent of the growth of the global supply of oil.19

For the first time in more than fifty years, the world oil market revolves around the United States rather than OPEC—a sixty-five-year-old cartel of state-owned oil companies, the majority of which are unstable and inimical to U.S. interests. Saudi Arabia, determined to reclaim its lost market share, has ceded to America its monopolistic role as the world’s only swing producer. Instead of reducing production in response to low prices, the Saudis are maintaining and probably increasing their production. The Saudis’ increasing domestic demand for energy is checking the amount of oil available for export. This is a major new dilemma for a country that derives roughly 90 percent of its revenue from the sale of crude oil. Unlike most of the world, the Saudis generate their electricity from oil. As the Wall Street Journal noted in July 2015, “in a country where subsidized crude oil still powers most homes and businesses, and where a gallon of gasoline costs less than a bottle of water, Saudi Arabia’s ravenous energy appetite is starting to strain the kingdom’s oil infrastructure and hamper its ability to throttle up exports.”20

If the United States, with its wide-open and decentralized oil industry, can act as the swing producer, the global oil market can function as a genuinely competitive market. Fortunately, the United States does not have a minister of oil setting production levels. Our domestic energy market consists of four thousand small and mid-size companies competing in a relatively free market. Could Adam Smith’s “invisible hand” now replace the autocratic bullies of OPEC?

The shale revolution is entering its second stage as producers consolidate, innovate to cut costs, and absorb the accumulated data from thousands of fracked wells over the last decade. Mark Mills, a physicist and venture capitalist in the information and communications technology world and fellow of the Manhattan Institute, persuasively argues that the next stage of the shale revolution, “Shale 2.0,” can double production and reduce costs by half, enabling the United States to continue and expand its international energy ascendency. The first stage of the shale revolution, Mills reminds us, “was not sparked by high oil prices. . . . [I]t began when prices were at today’s low levels—but by the invention of new technologies. Now, the skeptics’ forecasts are likely to be as flawed as their history.”21

The shale gale, as the energy guru Daniel Yergin calls the boom, has already achieved what not long ago was considered impossible. It was made possible not by government planning or “public investment” but by technological advances in the private sector, financial capital, and the entrepreneurial spirit, ingenuity, and grit of men like Harold Hamm, George Mitchell, Jim Henry, and Bud Brigham.

The implications of the shale revolution for international stability are enormous. Two million barrels per day of American oil would reduce the European Union’s dependence on Russian imports by half. U.S. natural gas exports are already reducing Vladimir Putin’s energy stranglehold over our NATO allies.

How Much U.S. Energy Are We Talking About?

The United States is blessed with vast and continually underestimated energy resources. America has more oil, coal, and natural gas than any other country in the world.

The official estimates of the U.S. Geological Survey (USGS) are notoriously low. In 2000, the USGS estimated that the Bakken shale field in North Dakota held between four and five billion barrels of shale oil. Harold Hamm concluded that oil deposits there were almost five times more than the government experts calculated. In 2012 he said, “We estimate that the entire field, fully developed in the Bakken is 24 billion barrels.”22 He was right, and this single oilfield doubled America’s proved reserves overnight.

The Bakken oil field is larger than the state of Delaware. In July 2014, North Dakota reached record production of one million barrels of oil per day. In 2007, North Dakota produced only two hundred thousand barrels per day. Not all states have shale fields, and some that do have prohibited hydraulic fracturing—most notoriously New York and California. Texas dominates the shale revolution, producing three times more oil than North Dakota, the second-highest producing state. Texas and North Dakota together provide nearly half of all crude oil in the United States.23

Those regions where shale resources are under development see the boom all around them. In addition to North Dakota and Texas, fracking is also underway in the Marcellus Shale and the Utica Shale in Ohio, Pennsylvania, and West Virginia, as well as the Haynesville and Fayetteville shale plays in Louisiana, Arkansas, and East Texas. Geologists may have long known that the oil and natural gas in shale rock were there, but they underestimated how much there was. This energy was never considered “technologically recoverable” because there was no known method to extract the energy at anywhere near affordable costs. Now we have those methods and they are getting cheaper to employ every year.

No country has been as efficient, innovative, or environmentally sensitive in the extraction of oil and gas as the United States, and no country has done it as profitably. Competition and reasonable regulation are part of the reason for our success, but there is another factor, distinctively American phenomenon. This is the only country in the world where mineral rights can be privately owned. In all other countries, the state owns the oil, natural gas, and other subsurface minerals. The incentive of private property rights in fungible resources propels the U.S. oil and gas business as nowhere else in the world. Nevertheless, federal policy is stifling our potential.

Ninety-six percent of the production in the shale revolution has occurred on private and state lands, over which the federal government has far less regulatory jurisdiction than on federally owned lands. President Obama occasionally takes credit for the shale boom when it serves his purpose, but under his administration production on federal lands—which hold plenty of shale resources—has declined substantially. In 2013, the Obama administration leased the fewest acres for oil and natural gas production on record.24 The federal government owns seven hundred million acres of our country’s land—almost 30 percent of the total land area of the United States.25 Only 5 percent of that seven hundred million acres is leased for oil and natural gas development.

Alaska has huge untapped mineral resources, but the federal ownership of almost 70 percent of the state’s land prevents their efficient development. Intrusive regulation, endlessly delayed permits, and outright bans on oil and gas development continue to limit production. Declining production from Alaska’s North Slope imperils the structural integrity of the Trans-Alaska pipeline, an engineering marvel that carries oil eight hundred miles from the remote North Slope to the port of Valdez, where it is shipped on tankers to refineries in California and other western states. Built at great cost in 1977, the pipeline was designed to move six hundred thousand barrels per day. Federal obstruction of new drilling has substantially reduced the volume of oil flowing through the pipeline, causing it to deteriorate. The loss of this strategic energy asset would be a disaster.

Oil and gas development on a minuscule portion of the remote Arctic National Wildlife Refuge (ANWR)—two thousand of the refuge’s nineteen million acres—has been blocked for decades. Yet, oil and gas production would occur on only 0.01 percent of the Refuge’s nineteen million acres!26 Original concerns about the effect of drilling on the caribou population are no longer valid. In 1968, there were six thousand Caribou in the ANWR. By 2009, the population approached sixty-seven thousand, and the animals were thriving amidst energy development in nearby areas.27 The USGS estimates that this tiny portion of ANWR contains over ten billion barrels of oil and could yield one million barrels per day,28 but President Obama is threatening to put ANWR permanently off limits to energy development.

And then there is the American mother lode of hydrocarbon resources found in three western states—oil shale. This resource is to be distinguished from shale oil. The distinction between oil shale and shale oil can be confusing, but oil shale derives from a solid known as kerogen. When heated, the kerogen produces petroleum-like liquids and natural gas. According to the USGS, the United States sits atop 2.6 trillion barrels of oil shale.29 Roughly half of this resource—four times the amount of Saudi Arabia’s proved oil reserves—is now technologically and economically recoverable. The United States is not running out of oil.

Offshore Resources

American taxpayers own the more than 1.7 billion acres of the submerged land of the Outer Continental Shelf (OCS) off our coasts.30 According to the Bureau of Ocean Energy Management, the OCS holds eighty-six billion barrels of oil and 420 trillion cubic feet of natural gas—all of that technically recoverable—but the federal government has leased only 2 percent of the OCS for energy development.31 Even as the nation was becoming increasingly dependent on imports of oil from countries hostile to U.S. interests, Congress enacted a prohibition on oil and gas development on most of the OCS in 1982, making the United States the only developed country in the world to prohibit oil and gas production off its coasts.

When the ban was finally lifted in the fall of 2008, President George W. Bush issued a plan for development of the OCS, which the Obama administration quickly rescinded in 2009. And in response to the 2010 oil spill from BP’s Deepwater Horizon well, the administration issued a six-month moratorium on both deep and much safer shallow offshore wells. During the ensuing “permitorium,” when the government obstructed the issuance of necessary permits, at least ten of the huge drilling rigs used in deep-water drilling moved to other parts of the globe.32

Greens vs. Growth

Since the early 1970s, policies driven by an entrenched environmental establishment have blocked or restricted development of domestic oil and natural gas. This effort has not reduced consumption of these fuels but has sent U.S. dollars to purchase oil from other countries—countries that oppose the foundational values of our nation. As many as 150 federal laws suppress the development of key domestic energy sources—oil, natural gas, coal, and uranium—enabling environmental activists to block projects planned for federal lands. One presidential signature can deprive Americans of critical natural resources. In 1996, for example, President Bill Clinton designated 1.7 million acres of land in Utah’s Grand Staircase Escalante as a national monument, putting the largest store of low-sulfur coal in the country off limits.33 This is the least polluting form of coal and in the highest demand.

Environmentalists allege that fracking contaminates community water supplies, putting residents at risk of cancer and other illnesses. The propaganda film Gaslands is famous for its depiction of a West Virginia homeowner igniting methane-laden tap water with a match. But that phenomenon has nothing to do with modern fracking. It is almost always due to naturally occurring methane migrating into shallow aquifers far above the areas that are fracked. After vigorous review by the federal and state governments, the Environmental Protection Agency reported that it knows of no incidents of water contamination directly caused by fracking anywhere in the country.34

Legitimate questions remain about the volume of water used in the fracking process, wastewater disposal, and the importance of recycling fracking water. The same industry, however, that created the technologies that made the shale revolution successful is rapidly developing technologies to minimize water use and to recycle waste water.

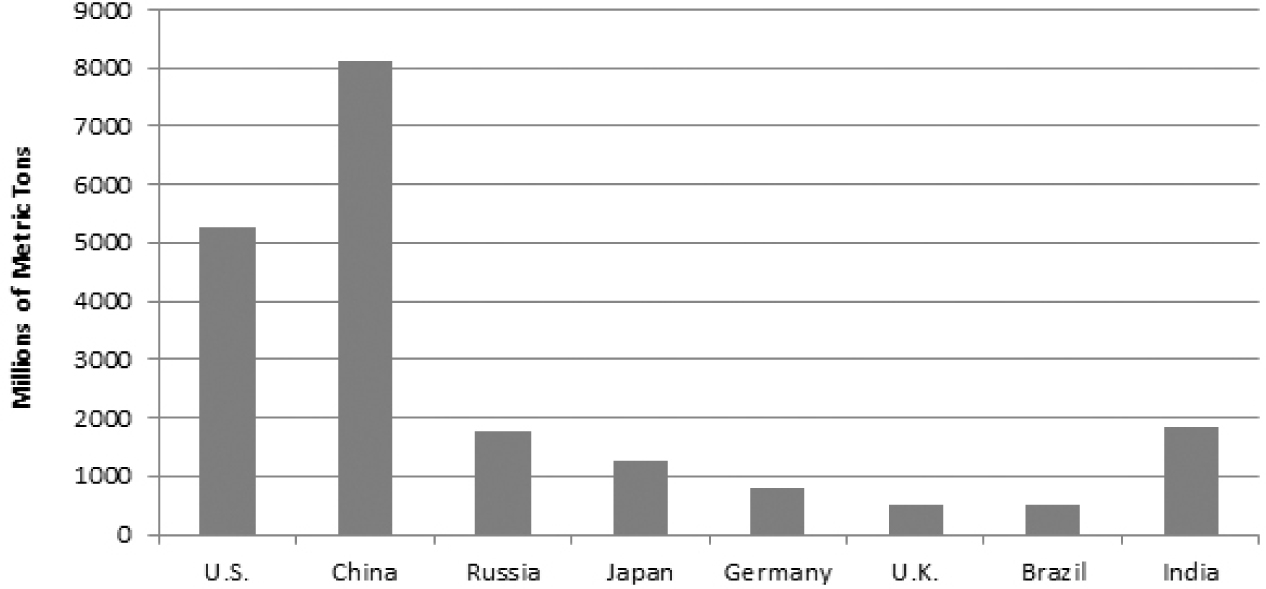

From an environmental point of view, the shale revolution has come at a promising time. Over the last four decades, American industries have dramatically reduced air and water pollution. The most important “criteria pollutants” listed in the federal Clean Air Act have declined by 60 to 70 percent. The accumulated technology, science, and practical know-how can make the shale boom the most environmentally sensitive engine of growth in our nation’s history. Increased use of natural gas now abundant from shale is already cutting greenhouse gas emissions. In fact, the U.S. has reduced its carbon emissions more than any other major country—thanks to shale gas. See Figure 2.3.

FIGURE 2.3

Change in CO2 Emissions by Country, 2006–2012

The shale revolution has also calmed fears of “peak oil.” Doomsday predictions about “using up” the food, water, energy, and other resources necessary for human survival are a regular feature of history. In the third century AD, for example, a dour Saint Cyprian wrote, “The world has grown old and does not remain in its former vigor. It bears witness to its own decline; the rainfall and the sun’s warmth are both diminishing; the metals are nearly exhausted; the husbandman is failing in the fields; the sailor on the seas. . . .”35 More recently, the Club of Rome issued its infamous Limits to Growth in 1972,36 a Chicken Little report as groundless as Cyprian’s lament.

History again and again reveals the human capacity to overcome temporary scarcity by finding new resources or substitutes. The shale revolution is the most recent and powerful example of this elasticity of natural resources. It is now clear that oil and natural gas are much more sustainable resources than we realized only a few decades ago. This is an achievement of the “ultimate natural resource”—the human mind—which will adjust, adapt, and create unless political powers suppress the freedom to innovate.

“Climate change” has supplanted “peak oil” as the anxiety du jour, and it poses the greatest regulatory threat yet to fossil fuel energy sources. With a president who declares the increasingly gauzy concept of climate change a greater threat to civilization than ISIS, the headwinds facing the shale revolution may be daunting.

What makes today’s popular doomsday predictions about climate change disturbing is the degree to which they have become institutionalized in the media, entertainment, academia, law, and the regulatory state. The notion of shrinking mankind’s “carbon footprint” has become a cultural norm. Yet our carbon footprint is the means by which we live longer, healthier, and freer lives than our ancestors did only a century ago. Show me someone who uses very little carbon, and I will show you someone who is likely very poor (or very, very rich). And on a closer look, high consumption of fossil fuels has allowed prosperous countries to shrink man’s physical footprint on the natural world. “Decarbonizing” is a delusional concept. Our bodies are built of carbon. It is the chemical basis of life on earth.

In his important book The Age of Global Warming,37 Rupert Darwall notes that policies intended to avoid the climatic dangers of fossil fuels lead to unintended results. The wind and solar farms required to supply power for large urban areas would destroy millions of acres of natural biodiversity. Imagine how many tens of thousands of acres would have to be paved over to provide electricity for Manhattan if it were all done with windmills. To power the entire nation with windmills would lead to the industrialization of the wilderness of America. How is that green?

Eliminating fertilizer made from natural gas would reduce the food supply—increasing the chronic hunger now suffered by five hundred million human beings. Germany’s rush to renewables has increased the use of coal-fired electric generation just to keep the electric grid from melting, and wood—the preindustrial dirty fuel—now accounts for roughly 50 percent of the European Union’s renewable portfolio.

The pedigree of today’s doomsday prophets goes back two centuries to the English cleric and economist Thomas Malthus, who speculated that the earth’s carrying capacity sets ironclad limits on the size of the human population. We will address Malthusian theories at greater length in subsequent chapters, but we observe here that Malthus and his disciples have—to date—always been wrong. Nevertheless, they have often done a lot of damage along the way.

Malthusian energy policies forecasting “peak oil” have regularly recurred since the middle of the nineteenth century when Edwin Drake drilled what history regards as the first commercial oil well. Only months before the shale revolution made itself felt, concern about peak oil and increasing oil imports produced the Energy Policy Act of 2007. Among other follies, that law imposed the Renewable Fuel Standard for corn ethanol and advanced biofuels, providing generous subsidies for ethanol makers. The ethanol mandate has achieved none of its objectives—reducing oil imports, displacing gasoline, improving air quality, and reducing carbon dioxide. The advanced biofuels that the law sought to promote are still non-existent in commercial quantity), though the EPA has fined refiners millions of dollars for their failure to blend gasoline with those nonexistent biofuels.

Two Energy Models and Two Economic Models: Solyndra v. Mitchell

Solyndra Model: Venture Socialism

• Hundreds of billions of dollars of taxpayer subsidy to “jump start” unprofitable renewable energy.

• Government picks winners and losers; subsidized winners undergo bankruptcy.

• Tax and regulate fossil fuels to create scarcity and increased price.

• Average cost per green job from stimulus subsidies: $10 million.

• Economic pie contracts—weak economic recovery from recession.

Mitchell Model: Private Capital in Competitive Free Markets

• Risk-taking entrepreneurs invest in innovative technology in competitive private market.

• Shale revolution creates thousands of new high-paying jobs within a few years.

• Continuous innovation reduces cost and increases output of production.

• The economic pie grows and everyone benefits.

What the ethanol mandate did accomplish was reduction of the global food supply in what is still the basic source of calories for much of the world population—grains. A year after the law was enacted, corn prices increased from $2 per bushel to $8. Food shortages occurred in many developing countries as the price of corn also increased the price of all food grains. In 2015, the ethanol mandate absorbed 40 percent of the U.S. corn crop. Multiple studies now conclude the production of ethanol is a net energy loss and increases genuine pollution and carbon dioxide. Ethanol policy is a prime example of counterproductive, outdated, and ethically offensive federal energy policy.

Green Energy: The Wrong Bet

There are so many reasons to be optimistic about the shale revolution, but the chief obstacle to this extraordinary energy opportunity remains the federal government. As Harold Hamm reminds us, the U.S. is on its way to becoming “energy dominant in the world” before the end of this decade. Private markets can chart the course; we don’t need grand federal plans.

We can’t take full advantage of America’s energy opportunity if we keep pouring tax dollars into inferior “green energy” sources like wind and solar. That’s the wrong bet. After decades of lavish subsidies and mandates, let the renewables industry find its own place in the competitive market of diverse fuels without any taxpayer subsidies.

Our national leadership needs to promote drilling in North America. We should not be hesitant or embarrassed to responsibly develop our energy bounty. Reducing the pollution once associated with oil, natural gas, and coal is one of the major public policy success stories of the second half of the twentieth century, but nobody talks about it. However disappointing to some who have pledged their careers to politicized climate science, carbon dioxide is not a genuine pollutant capable of harming human health. Fossil fuels—abundant, affordable, concentrated and versatile—are superior to other energy sources at this time.

The “green energy” lobby is on a never-ending quest for taxpayer handouts for an industry that supplies less than 3 percent of our nation’s energy needs. In the first eight months of 2015, wind produced 1.7 percent of all energy consumed and 4.3 percent of our electricity. Solar power produced 0.6 percent of all energy consumed.38

The shale industry, by contrast, does not need or seek government funds. (Oil and natural gas producers take advantage of tax deductions available to all businesses, but they don’t use taxpayer-funded subsidies.) The shale industry creates new value and thus enlarges the economic pie. Subsidizing renewable energy merely distributes a static or shrinking pie. All the government needs to do to encourage the great American oil and gas renaissance is to get out of the way. That’s a message that only the Saudis and the Iranians could hate. Unfortunately, getting out of the way doesn’t come naturally for politicians and federal regulators.

Paying Down the National Debt

One issue to consider in the debate over national energy policy is this: how much could the federal government raise in royalties, drilling fees, and income taxes if it allowed a drilling on federal lands? We have examined the latest geological inventories made by the U.S. Energy Information Administration, the USGS, and private think tanks like RAND to get a rough estimate of how much energy there is and what it is worth.

With the aid of Jack Coleman, a former Interior Department engery expert, we found that the untapped resources in states like Alaska, California, Colorado, Texas, and Utah and under the Outer Continental Shelf are so bountiful that the recoverable totals of oil with existing technology are more than 1.5 trillion barrels. And there is approximately three quadrillion cubic feet of natural gas. The value of this energy is at least $50 trillion, and at least fifty times annual U.S. consumption. This estimate is almost certainly low, because drilling technologies are improving so rapidly that Uncle Sam is continually raising the inventory of what is “technically recoverable.”

By allowing drilling on federal lands, the United States could increase output by nine hundred thousand barrels of oil per day for twenty years, which would increase production by 150 percent through 2037. There could be a corresponding 80 percent increase in natural gas output (0.9 Tcf/year increase for twenty years). If those figures seem implausible, consider that U.S. oil and gas output are already up about 75 percent since just 2007.

If President Obama’s successor allowed drilling on federal lands and pursued what the government calls a “high-production” strategy over the next twenty years, we estimate that royalties would bring in $1.1 trillion, with an added $0.15 trillion from natural gas. Another $1.25 trillion in direct federal income taxes would be collected on the oil and gas industry. Lease payments would raise approximately $210 billion, bringing total revenues over twenty years to just over $2.7 trillion.

The total passes $3 trillion when including federal income taxes on suppliers and other contractors involved in these production activities, plus federal income taxes on the million or more new, highly paid employees of the exploration and production companies, their suppliers and contractors. State income, property, severance, and other taxes could raise another trillion dollars or more for states and localities. That’s more revenue than just about any bipartisan deficit-reduction plan could ever deliver. In short, the oil and gas under our federal lands and waters is the fiscal equivalent to a cure for cancer.

Imagine how foolish it would have been if the Saudis had decided forty years ago not to drill for their oil. When President Obama absurdly argued after the 2015 Paris Climate Change Conference that we must keep these resources “in the ground,” did he remotely understand that he would deprive Americans of millions of high-paying jobs and the nation of $50 trillion of added output over the next two decades? This could be the greatest act of national economic self-mutilation in world history.

To be clear: we are not talking about drilling in Yosemite or Yellowstone, or as President Obama once jibed, on the National Mall next to the Washington Monument. Instead we are urging an all-out national commitment to drilling on non-environmentally-sensitive lands, from the Arctic to New Mexico and offshore.

This national energy strategy would secure America’s economic leadership for decades to come and would strengthen our national security by ensuring that the world is never again held hostage by OPEC or other unfriendly interests. It is the game-changer America has been waiting for. All that is required is the kind of visionary leadership that was shown by John F. Kennedy who told the American people we were going to the moon.

The shale revolution, which has unlocked vast new reserves of American energy, could be one of the most important developments in modern history. It offers more promise for prosperity and stability—not only in this country but around the world—than any economic or diplomatic plan that politicians and bureaucrats have yet dreamed up. And yet it’s the progressives in the Western world who are standing athwart history yelling “Stop!”