How Energy Is Remaking the U.S. Economy

To understand fully how the shale revolution has remade the American economy over the past decade, consider the unlikely transformation of North Dakota, once one of the slowest growing states, with brutally cold winters and an economy dominated by wheat farms and ranches. Consider in particular the town of Williston.

Sitting atop the Bakken shale, Williston gives you an idea of what the mid-nineteenth-century Gold Rush must have been like. The oil rush of 2007–2014 made North Dakotans rich in a hurry. One retired farmer boasted to us that, thanks to the oil rigs churning on his property, he suddenly has a net worth of more than $30 million. North Dakota now has more millionaires per capita than any other state.

Williston was once a town of about three thousand wheat farmers. It is many times that size today, but no one knows exactly how many people live there. Hundreds of workers slept in their trucks, and hotel rooms went for as high as $500 a night. The town put up temporary encampments, and new homes were popping up as fast as they can be built. At the height of the boom, the local McDonald’s was offering workers up to $18 an hour plus a “signing bonus” of as much as $500; the minimum wage was irrelevant here.

The oil wells of Williston seem to be bottomless. In 1995, the U.S. Geological Survey estimated there were one hundred fifty million “technically recoverable barrels of oil” in the Bakken shale. By 2013, geologists were estimating twenty-four billion barrels. Current technology allows for the extraction of only about 6 percent of the oil trapped one to two miles beneath the earth’s surface, so as the technology advances, recoverable oil could eventually exceed five hundred billion barrels. That’s more than Saudi Arabia has. North Dakota has surpassed California and Alaska in oil production for the first time and now ranks second behind Texas.

The Census Bureau reports that North Dakota led the nation in the rate of job and income growth from 2007 to 2011. At the height of the boom, 2008–2013, the state’s unemployment rate fell below 3 percent, though even that astonishingly low official figure was misleadingly high in a state that had ten thousand more jobs than skilled workers to fill them.

The North Dakota miracle is the result of technology and know-how and entrepreneurship, not just abundant natural resources. No one has been more surprised by the shale revolution than the federal government, which under Presidents George W. Bush and Barack Obama lavished more than $75 billion on wind, solar, ethanol, and other “clean energy” initiatives.

With the fall in oil prices from three figures to below $50 in the fall of 2015, the boom in North Dakota has shifted into a lower gear, and new drilling has slowed to a crawl for now. But with the development of more effective technologies, we are only at the beginning stages of the shale revolution.

Texas vs. California: A Tale of Two States

Before we discuss the national implications of the oil and gas boom, it’s instructive to look at two states with diverging economic fortunes over the past decade.

For years, Texas and California, America’s two most populous states, have been competing against each other as alternative models of growth. One state has embraced the shale revolution, while the other has spurned it in favor of green energy. The Golden State had long been one of America’s big three oil producing states, along with Texas and Alaska. Its replacement by North Dakota isn’t a matter of geological luck but of good and bad policy choices. California has plenty of oil and natural gas.

Though few outside the energy business have noticed, Texas nearly tripled its oil output from 2005–2014. Even with the surge in output from North Dakota’s Bakken region, Texas produces as much oil as the four next-largest-producing states combined. Barry Smitherman, a former chairman of the Texas Railroad Commission (which, despite the name, regulates the energy industry), predicts that “total production could triple by the early 2020s” from the nine and a half million barrels produced per day in 2015.1

The two richest oil regions of the United States are in Texas: the Permian Basin (including the Wolfcamp formation) and the Eagle Ford shale formation in South Texas, where production was up 50 percent from 2012 to 2015. The Midland-Odessa urban area in the Permian, surrounded by millions of acres of remote and arid rangeland, is one of America’s fastest-growing metropolitan areas.

Nearly four hundred thousand Texans are employed by the oil and gas industry (almost ten times more than in California), and the average salary in the industry has gone as high as $100,000 a year. The industry in Texas generates about $80 billion a year in economic activity, exceeding the annual output of all goods and services in thirteen individual states.

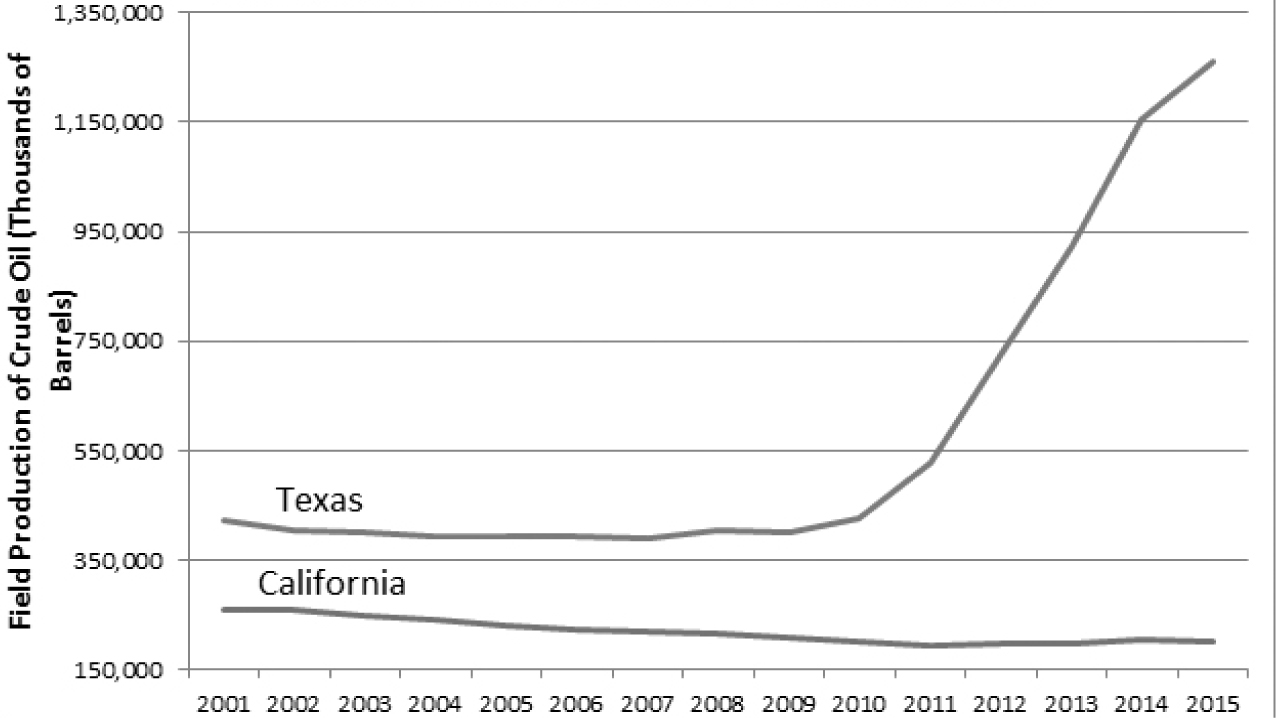

Now look at California, where oil output was down 21 percent between 2001 and 2012, according to the U.S. Energy Department, even as the price of oil remained at or near $100 a barrel. See Figure 3.1. That’s not because California is running out of oil. To the contrary, California has huge reserves offshore and even more in the Monterey shale, which stretches two hundred miles south and southeast from San Francisco. The Department of Energy estimates that the Monterey shale contains about fifteen billion barrels of oil—more than the estimated technically recoverable supply in the Bakken.

Why the Reddest State Is Covered with Wind Turbines

Even in Texas, the capital of oil and gas, the federal subsidy for wind power has led to the installation of more than twelve thousand MW of wind generation but the state has not directly subsidized this green energy. Local governments, however, have given tax abatements for renewable installations. Indirectly, the state has socialized the cost of constructing over thirty-six hundred miles of new transmission lines to connect the wind farms in the remote far western regions of the state to the urban areas in central Texas.2 These lines extend as far as seven hundred miles from the source of wind-generated electricity to the urban end-user. The $7-billion cost of building what are called, ironically enough, the Competitive Renewable Energy Zone lines, will be imposed on retail consumers of electricity.

The Texas legislature did establish a mandatory Renewable Portfolio Standard in 1999 that obliges utilities to use a minimum amount of renewable generation. Compliance with the standards can be satisfied by purchase of “renewable energy credits.” The initial goals were staggered and quite modest, with a final target of two thousand megawatts of installed renewable capacity by 2009. This proved to be a piece of cake. Texas hit twelve thousand megawatts by 2010 thanks to a generous federal subsidy. The increasingly lavish federal subsidies for construction of new renewable facilities, favorable wind conditions, wide-open spaces, and guaranteed transmission led to rapid installation of wind farms.

Unfortunately, much of California’s oil lies under federal land. The Sierra Club and the Center for Biological Diversity sued to stop Occidental Petroleum from fracking in the Monterey shale, and in 2013 a federal judge blocked fracking in California and ordered an environmental review of the drilling process that Texas, North Dakota, and other states have safely regulated for years. “We’re very excited. We’re thrilled,” exclaimed Rita Dalessio of the Sierra Club in response to the ruling. “I’m sure the champagne is flowing in San Francisco.” No doubt. Meanwhile, the oil is flowing in Texas.

FIGURE 3.1

Crude Oil Production: California vs. Texas

Even if the oil is on private land, California can make it politically difficult to get to it. Getting approval for an oil rig can take months in California. In Texas, the average is four days. In short, Texas embraces the oil industry because almost everyone benefits from it, while Californians, brainwashed into believing that oil and gas are “dirty fuels,” are embarrassed by it. Which is odd, since who drives more than Californians?

California has also passed cap-and-trade legislation that adds substantially to the costs of conventional energy production and refining. The politicians in Sacramento and their Silicon Valley financiers have made multibillion-dollar, and mostly wrong, bets on biofuels and other green energy. In his article “The California Green Debauch,” George Gilder laments, “Sadly, the bulk of the new venture proposals harbor a ‘green’ angle that turns them from potential economic assets into government dependencies that ultimately deplete U.S. employment and tax revenue.”3

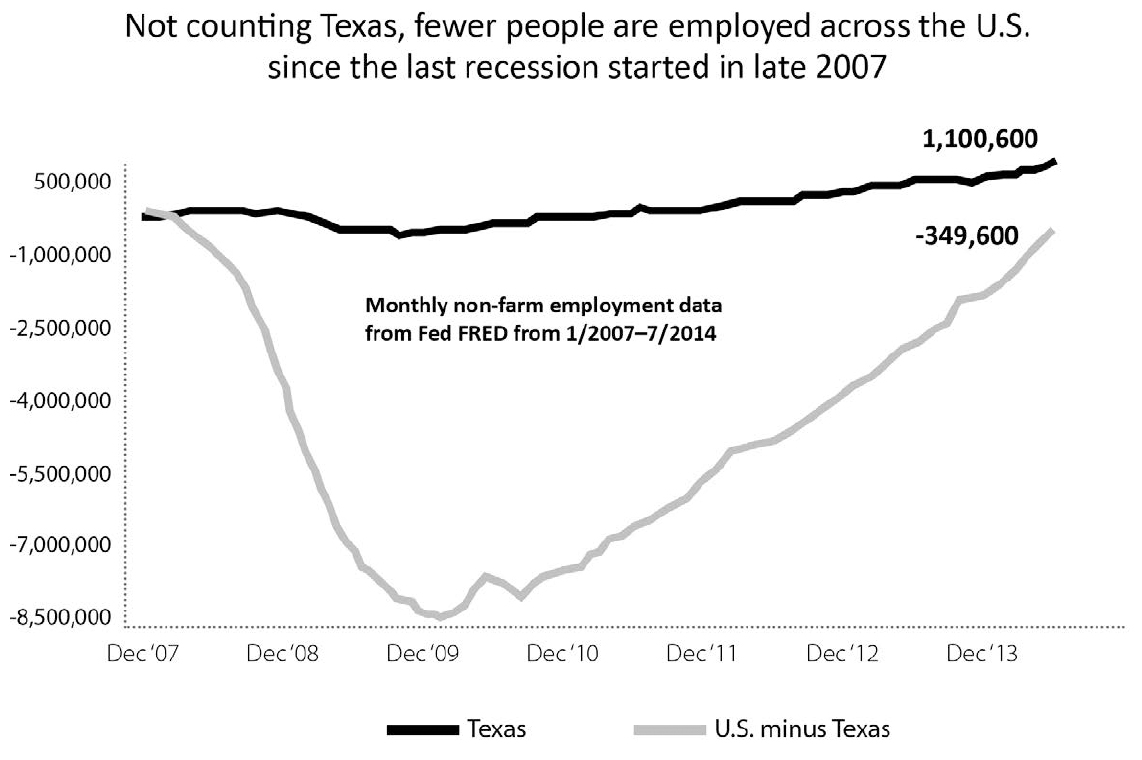

Texas’s open attitude toward the energy industry explains why the Lone Star State led the nation in job creation from 2007 to 2013. See Figure 3.2. In fact, Texas created more jobs than the rest of the nation combined on net over those years. The energy boom created thousands of jobs directly related to drilling but also in hundreds of service industries, such as transportation, high technology, and construction. Ancillary industries—processing oil and natural gas and the manufacture of petrochemical products, for example—also contributed to the explosion of jobs. The Census Bureau reports that from 2004–2014, net in-migration to Texas was 1.23 million people, while California suffered a net out-migration of 1.39 million people.

FIGURE 3.2

Carrying the Load in the Lone Star State

Source: Bureau of Labor Statistics

The Texas treasury benefits from oil production. In 2012, oil and gas production generated $12 billion in state taxes—a painless source of revenue that helps Texas avoid a state income tax. Californians, on the other hand, face a top marginal income tax and capital gains tax rate of 13.3 percent.

The only reason California lags so embarrassingly far behind Texas is that it chooses to. California’s problem is not a lack of resources. The Monterey shale alone is thought to contain about $2-billion-worth of oil and natural gas. But the politicians—at the behest of their green-energy allies—have decided to wall off the state from developing its fossil fuels. Prohibitive environmental regulations, a misguided cap-and-trade law, costly renewable energy mandates, and forty years of prohibitions on almost all offshore drilling amount to a “Keep Out” sign for the energy industry. So the oil remains locked in the ground as one million Californians look for work, as its schools and roads deteriorate, and as it keeps raising taxes to balance the budget. What a tragedy.

Imagine how fast the U.S. economy would grow if California were more like Texas. Imagine how fast the U.S. economy would grow if all states were more like Texas. Shale oil and gas aren’t the whole story of the state’s success. Texas has many policy advantages over its sister states, including no income tax. But if the rest of the United States had grown as Texas did from 2007 to 2013, America would have had an additional ten million people working in 2014.

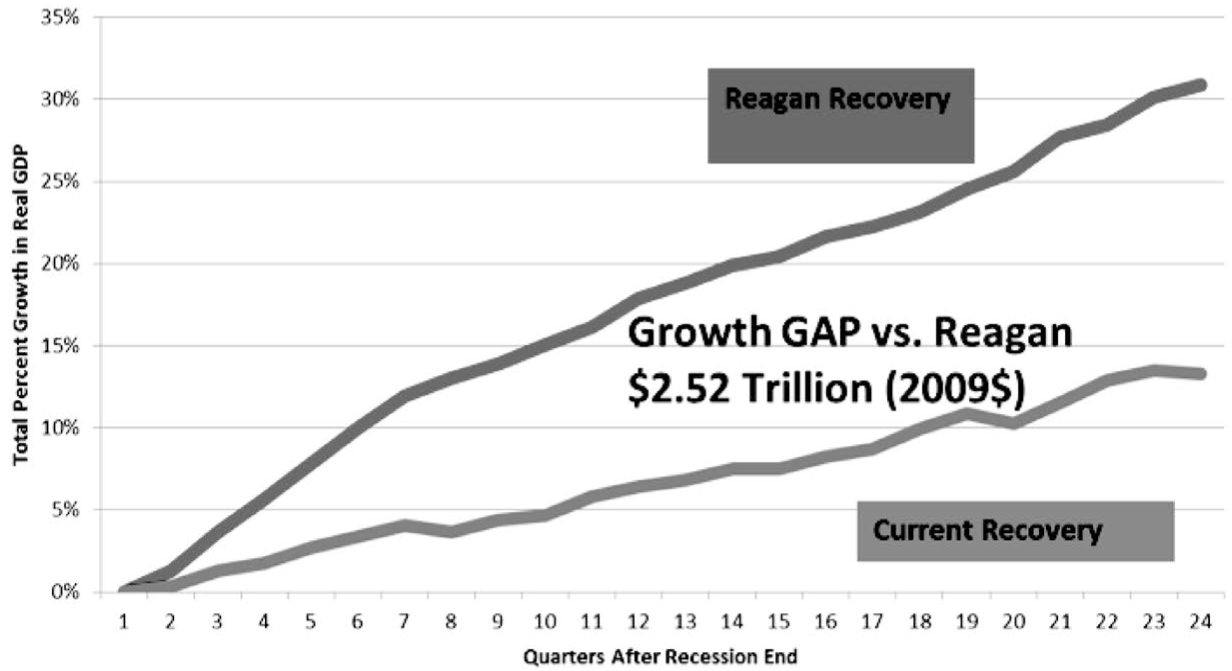

The National Energy Opportunity

Now let’s look at the national economic picture. The economic recovery in the United States from 2009 to 2015 has been the slowest since the Great Depression. Figure 3.3 shows how meager it has been. Our economy has fallen about $1 trillion below the trend of growth from a normal recovery and $2.9 trillion behind the pace of the Reagan-era expansion. Job growth has been about six million behind pace. The income of the average middle-class family fell by $500 from the beginning of the recovery through 2014. No wonder almost half of Americans surveyed in 2014 believed that the nation was still mired in a recession.

FIGURE 3.3

Recovery’s Growth Gap vs. Reagan’s Recovery

Source: Bureau of Economic Analysis

The economy’s weakness wasn’t for want of governmental effort. Under Presidents George W. Bush and Barack Obama, we had trillion-dollar bank and housing bailouts, $830 billion in “stimulus” spending, minimum wage hikes, cash for clunkers, $3.5 trillion of new money created by the Federal Reserve Bank, Obamacare, and tax increases on the rich. But nothing Obama or the Fed or Congress did pulled us out of recession. (Some of those measures probably hurt the economy.) What ended the recession was the shale revolution.

This burst in output has changed the economic landscape in important ways that most Americans still don’t fully appreciate. In fact, plenty of high-powered economists undervalue the dynamic role energy plays in our economy. You can’t calculate the economic value of energy using only the government data for the so-called energy sector, for those data measure only the upstream production activity, excluding the horde of service businesses directly connected to oil, natural gas, and coal and the many petrochemical industries that use petroleum and natural gas to make thousands of products. Traditional assessments of the energy sector exclude its role throughout the entire economy. From the healthcare industry to the digital universe, energy is as important to the U.S. economy as the nervous system is to the human body. The growth in the world global economy over the last century has tracked the increased consumption of fossil fuels.

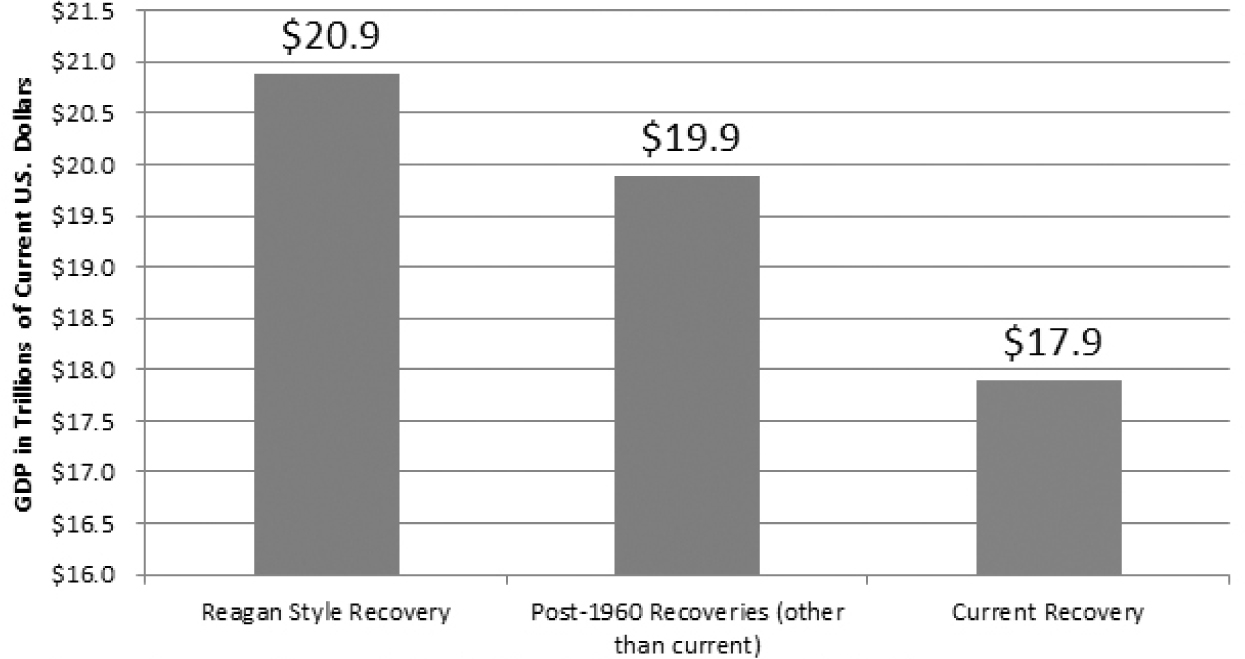

FIGURE 3.4

$3 Trillion Growth Deficit

Source: Bureau of Economic Analysis (using Federal Reservedeflator)

Fracking for Jobs

As weak as the recovery from the Great Recession of 2008–2009 has been, there would have been none at all without the oil and gas industry. It created more than a hundred thousand jobs from the beginning of 2008 through the end of 2013, while the overall job market shrank by 970,000.

In 2011 alone, oil and natural gas producers and suppliers added $1.2 trillion to GDP—7.5 percent of the total. They directly contributed over $470 billion to the U.S. economy in spending, wages, and dividends—more than half the amount of the 2009 federal stimulus package. Of this spending, $266 billion was for developing new energy projects, improving existing ones, and enhancing refining and related processing operations.4

The Manhattan Institute’s Mark Mills finds that “about 10 million Americans are employed directly and indirectly in a broad range of businesses associated with hydrocarbons.” Prior to the shale revolution, the number of energy jobs in America had been falling for thirty years, but that industry is once again one of the major employers in the nation.5

Made in America

The collateral job growth and community redevelopment from the shale revolution have been phenomenal. In Youngstown, Ohio, steel plants have been rebuilt. Fracking has revitalized Wheeling, West Virginia, a city left for dead when the steel mills, coal mines, and factories closed. Farmers in Pennsylvania and North Dakota have gotten rich leasing their land for drilling. Pittsburgh, the capital of Marcellus shale natural gas production, is back as an oil and steel town.

Outside the Rust Belt, the petrochemical industry is enjoying massive new investment thanks to cheap natural gas. Price Waterhouse Cooper reports that $125 billion in new capital has been poured into 197 new plants.6 The petrochemical industrial complex in the region around Houston, already the largest in the world, is dramatically expanding. The low price of natural gas has put ten thousand people to work constructing a giant new Exxon Mobil ethylene plant that will add four thousand jobs to the local economy. Terminals on the Texas Gulf coast built not long ago to handle imports of natural gas are now being reconfigured to serve as export terminals, though the Obama administration is holding up the export of liquefied natural gas with meaningless bureaucratic delays.

American manufacturing has made a comeback in recent years, and low energy prices attributable to fracking have been a major springboard for this recovery. The United States now has lower electricity prices than any of its major industrial competitors except Korea (see Figure 3.5). American industries pay one-half to one-fifth of what industries in the European Union pay for power, and electric rates for American households are a third of those for German households.

FIGURE 3.5

Electricity Industrial Prices per kWh, 2013

Source: United Kingdom, Department of Energy & Climate Change, International industrial energy prices in the IEA (QEP 5.3.1). Adjusted to USD using exchange rates from the report.

In 2014, the organization Energy in Depth documented the effect of cheap oil on American manufacturing, citing more than one hundred major manufacturing facilities with $80 billion in capital investment and five hundred thousand jobs. In a series of reports tracking new capital investments in the chemical industry since 2011, the American Chemical Council points to $125 billion invested in increased production capacity that was made possible by cheap and abundant natural gas extracted from shale.7 These investments will create over five hundred thousand permanent jobs and generate billions of dollars of new tax revenue for local, state, and federal government.

Abundant natural gas has revived the competitiveness of U.S. manufacturing that was long lost to foreign countries with far lower production costs. And the energy output of U.S. shale fields has not only brought jobs back home, but our low-cost shale energy is attracting investment from foreign companies. “Roughly half of the announced investments [in the American Chemical Council report] are from firms based outside the U.S. Our country is poised to capture market share from the rest of the world, and no other country has as bright an outlook when it comes to natural gas.”8

Europe’s Green Energy Flop

Now for the flip side of the story. One of the most dimwitted energy strategies of modern times is the Euro zone’s infatuation with green energy. What Europeans have discovered in their well-meaning crusade to save the planet from climate change is that “go green” means go expensive or go infeasible or go in reverse. Europe’s green blunder has sent its electric power costs soaring relative to the United States’.

Nowhere is the damage more visible than in Germany, which in 2005 passed the most aggressive renewable energy law in the world. The short-term goal was 30 to 50 percent reliance on renewables, with an eventual goal of 80 percent over the next several decades. The process of force-feeding industry and households green energy has increased utility costs and in some cases crippled manufacturing production. In 2013, a Deutsche Welle headline read “High Energy Costs Drive German Firms to U.S.” For example, in 2014 nearly one hundred German chemical companies announced plans to invest in the United States. Everybody in Germany—including the renewables industry—has lost. And to add insult to injury, Germany’s energy transformation has increased emissions of carbon dioxide. From 2009 to 2013, Germany’s emissions of carbon dioxide rose by more than 9 percent, while U.S. emissions rose only 1.3 percent.9

In many cases, especially Germany, that difference is the result of the costly rush to renewable sources of electric generation. Germany drained $32 billion from its economy spent on renewable subsidies in 2014, and its former minister of energy and the environment Peter Altmaier predicts that renewable subsidies will reach one trillion euros by 2030.10 The loss of capital assets in conventional energy infrastructure, moreover, will cost another trillion.

Subsidizing uneconomical renewable-derived electric power inevitably leads to subsidizing lots of other things: the energy-intensive industries dependent on high-priced green electricity, the conventional generators that cannot profitably compete with heavily-subsidized renewables, and the low- and fixed-income consumers who can’t afford soaring electric rates. Consider the contrast with the energy transition from renewable fuels (wind and wood) to fossil fuels that distinguishes the Industrial Revolution. In England, the price of coal and of the products whose manufacture depended on coal declined and productivity rose. The cost of consumer products fell, and the average wage increased. In time, a growing and enduring middle class emerged for the first time in history. Yet the green energy policies now in vogue, gambling on uneconomical, diluted, and unreliable renewable energy sources, would force a return to pre-industrial energy scarcity that had trapped most of mankind in poverty before the Industrial Revolution.

The Wall Street Journal charitably calls the German renewable energy push a “gamble” that doesn’t appear to ever have a chance of paying off. “Many companies, economists, and even Germany’s neighbors worry that the enormous cost to replace a currently working system will undermine the country’s industrial base and weigh on the entire European economy. Average electricity prices for companies spiked across the European Union, soaring by 54 percent in Germany, for instance, over the five years from 2009 to 2013 because of costs passed along as part of government renewable energy mandates.”

Five years ago, many of the European nations expected the rest of the world to follow their lead and spurn fossil fuels, says Daniel Yergin, an international energy expert. That hasn’t happened, and it isn’t likely to. Companies cannot compete when they pay two or three times more for power than their rivals do. We will look at Europe’s green blunder in more detail in a later chapter.

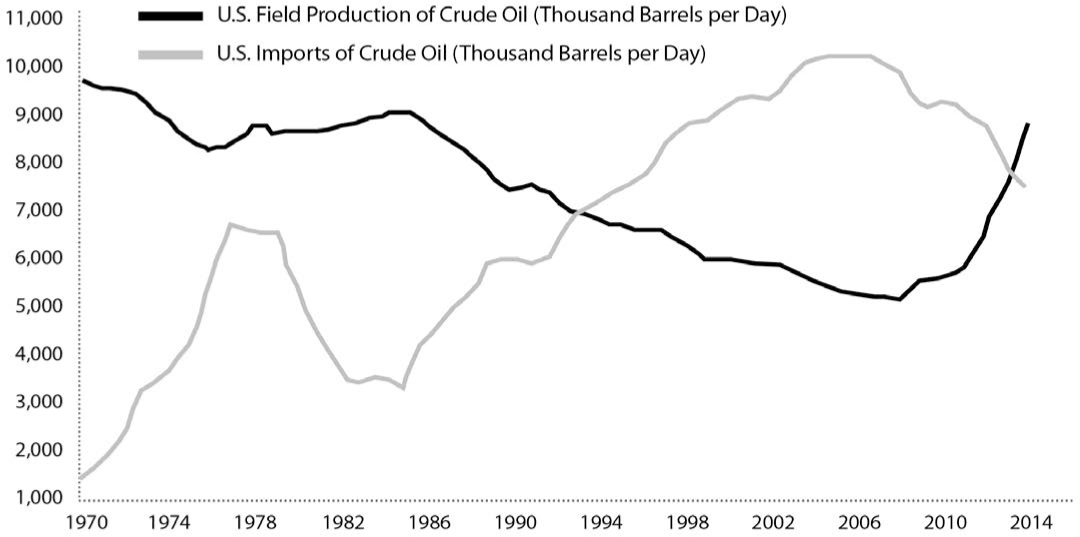

FIGURE 3.6

Imports Fall as U.S. Production Rises

Source: U.S. Energy Information Administration (EIA)

How the Malthusians Got It Wrong

The shale revolution took even the most prescient energy experts by surprise. Many economic forecasters expected oil and natural gas prices to double or triple in the years to come, and those predictions were the rationale for massive subsidies for renewable energy. President Obama betrayed his own inability to see what’s coming in a statement from 2010: “Oil is a finite resource. We consume more than 20 percent of the world’s oil, but have less than 2 percent of the world’s oil reserves. And that’s part of the reason oil companies are drilling a mile beneath the surface of the ocean—because we’re running out of places to drill on land and in shallow water.”11 The next year, as the shale revolution roared on, Obama declared that oil and gas were “yesterday’s energy sources.”

A sustainable energy abundance is no longer in question. We now know that energy resources that were thought to be running out will be plentiful for several hundred more years. Figure 3.6 shows how domestic production has soared while imports have declined, putting America on the verge of being energy independent for the first time in nearly half a century. And because the United States is so far ahead of the other oil-producing nations in energy technologies, before the end of the decade, we can move from being energy dependent to energy dominant. It is now realistic to think about wiping out our balance-of-trade deficit.

Now for a Real Stimulus: Low Gas Prices

No one was more surprised by the swift decline in oil prices in 2014 and 2015 than President Obama. As a candidate, he had announced that his policies like cap and trade taxes would “necessarily raise gas prices.” In 2009, his secretary of energy said the administration’s renewable energy policies would be a success if U.S. gasoline prices reached a European level—that would be around $10 per gallon. And during his 2012 reelection campaign, he derided those who insisted that drilling could alleviate the high cost of energy. “[A]nyone who tells you we can drill our way out of this problem doesn’t know what they’re talking about—or isn’t telling you the truth.”12

Then between June 2014 and April 2016, the price of oil fell from $105 a barrel to below $40 a barrel. The average price of a gallon of gasoline fell to around $2. Those oil and gas prices translated to a $200-billion savings for American consumers and businesses. That’s $200 billion a year we don’t have to send to Saudi Arabia, Kuwait, and other foreign nations. Now that’s an economic stimulus par excellence.

We don’t know if oil will remain in the $30–50-a-barrel range. But it is clear that low energy prices are a gigantic economic windfall for consumers. A fall in energy prices is a massive tax cut for the world’s consumers. The rule of thumb is that a one-cent reduction in the price of gas at the pump saves consumers $1 billion a year. The typical household in America spends about $5,000 a year on energy. Cutting these costs by 30 percent produces a windfall of nearly $1,500 for each family. Because low-income families spend more than twice the percentage of their budget on energy than high-income families do, falling prices for energy help the poor the most. That is the payoff from fracking and shale oil.

Are Lower Oil Prices a Saudi Plot?

We hear over and over that low oil and gas prices are actually a curse because they will drive American producers out of business and then the price will shoot up again. That’s happened before. And it is true that Saudi Arabia began deluging the world with oil in 2014. This surge in supply drives the world oil price relentlessly lower. They may be strategically driving marginal wells out of business with the low prices. The Saudis are still the lowest-cost producers, so they can withstand lower prices and still make money. And indeed, oil exploration and permitting in the United States have been cut by well over half as the prices have tumbled. Nevertheless, productivity per rig increased by 400 percent from 2008 to 2014—by 40 percent alone in 2014.13 Many wells have been drilled but await the hydraulic fracturing to extract the oil and gas, the most expensive portion of the process. And the turnaround time for completion of the wells is short.

Is the Saudi strategy working? In the short term, it has shut down many operations in the United States, but it is obvious that the most efficient wells are producing. In June 2015, one year after the plunge in oil prices, half of the drilling rigs had left the shale fields, and more than one hundred thousand jobs had disappeared. But rig counts, although widely cited by the media as the indicator for production volumes, can be misleading. This is especially the case with hydraulically fractured wells. There is a great difference in the cost of drilling, fracking, and output among these wells. “Shale technology,” Mark Mills points out, “allows astonishingly fast increases in production and at volumes that can move global markets; furthermore, U.S. capital markets are inherently flexible, fast, and have plenty of capacity to fuel shale expansion almost overnight if prices and profits creep back up.”14

The U.S. Energy Information Administration reported a production level in the United States of more than 9 million barrels a day in March 2016 and projects that the average production of the entire year will remain around 9.5 million barrels per day. That is a colossal figure and not far behind Saudi Arabia’s near-record of 10.3 million barrels in May 2015. Even when prices fell by 50 to 70 percent in the course of a year, U.S. oil production rose by 1.2 million barrels per day in 2014—the largest increase in one hundred years. Lower prices have not derailed the shale industry. It appears that the most cost-efficient and productive wells are still in operation and even setting records. Rapidly improved drilling techniques that lower costs and increase oil output have been the hallmark of the shale boom, and both trends are likely to accelerate.

The Arabs detected the emerging shale boom early on and understood its potential to make energy cheaper for decades to come. In 2011, the head of Saudi Arabia’s nationally owned oil company, Aramco, predicted a shift of the global axis of energy from OPEC to North America. This shift was well underway in 2015 as Aramco ceded to the United States the role of the world’s swing producer. Instead of reducing production in a time of over-supply—the economically logical response—the Saudis are maintaining production. If the U.S. shale industry can weather the glut, keep reducing its costs, and increase its output, the advantage is for the United States, which is well suited to be the swing producer, ramping up or ramping down in swift response to demand. With a massive inventory of oil in storage and as many as five thousand wells drilled but not yet fracked, U.S. producers inadvertently developed a rapidly deployable spare capacity—previously the Saudis’ exclusive advantage. What an amazing shift in global geopolitics such a development would portend!

The plunge in oil prices in 2014–2015 was good for consumers, but if prices continue to drop, could we bankrupt our domestic industry? Many wells can still make money at prices well below $50 a barrel. The speed with which drillers have reduced costs while they increased output should give the pessimists a pause. Those who worry about low oil prices need to read Henry Hazlitt’s classic Economics in One Lesson. Would it be a bad thing if OPEC and energy companies started giving their oil away for free?

In a free enterprise system, as productivity rises and technology improves over time, resources become more abundant, not less. Meanwhile, prices of those things fall. Food is the classic example. Fewer farmers today grow more food for more people than ever before, and at lower prices to consumers. This process makes us all richer. It is true that lower prices are not good for energy producers. For Texas, Oklahoma, and North Dakota, the nearly 60 percent fall in prices is bad news. But for everyone else, it is a glorious financial windfall—an early Christmas gift from heaven. Since energy is a component of everything we produce and consume, lower oil prices make everything cheaper—from candy bars to MRIs to computers to airline tickets.

Lower oil prices cripple our adversaries. Fracking has helped break the back of OPEC, now a powerless cartel, defund ISIS and other terrorist networks, and restrain Russia’s territorial ambitions. What’s the problem with that? Investors may lament the decline of energy stocks, but almost every industry other than upstream oil and gas production benefits from lower energy prices.

Our Energy Potential

Life and politics are often rich with irony. One of the richest is that Barack Obama, a president who wants “to end the era of fossil fuels,” has in his two terms in office presided over the biggest explosion in oil and gas production in history. This surge in production happened in spite of Washington, not because of it. Mr. Obama tries to take credit for the jobs and GDP growth from fracking even as his EPA, State Department, and Interior Department try to tear it all down.

The United States is now the world’s richest nation in energy in part because of our vast resources but just as importantly because of our technological prowess. What is most exciting about the potential for expanded growth of this industry is that no government subsidies are needed. And though some at the Department of Energy take credit for inventing fracking, this was all private-sector driven. Al Gore did not invent the Internet. And DOE did not invent fracking or horizontal drilling. They are simply trying to stop it.