"The United States will conquer Mexico," philosopher Ralph Waldo Emerson predicted at the outbreak of war in May 1846, "but it will be as the man swallows the arsenic, which brings him down in turn. Mexico will poison us."1 Emerson correctly predicted that America's first major foreign war would have disastrous consequences, but he was wrong about what they would be. The assumptions of Anglo-Saxon superiority he shared with his countrymen caused him to fear that absorption of Mexico's alien people would sully the purity of America's population and the strength of its institutions. In fact, it was the cancer of slavery within U.S. society that, when linked with disposition of the territory taken from Mexico, poisoned the body politic, provoking the irrepressible crisis that eventually sundered the Union.

Indeed, throughout the 1840s and 1850s, slavery and expansion marched hand in hand. Certain of the superiority of their institutions and greatness of their nation, a bumptious people continued to push out against the weak restraints that bound them. Through negotiation and conquest, they more than doubled the nation's territory by 1848. By the time of the Mexican-American War, however, the future of the South's "peculiar institution" had provoked passionate controversy. Even before the war, slavery had become for southerners the driving force behind expansionism and for abolitionists the reason to oppose acquisition of new territory. The conquest of vast new lands in the war with Mexico brought to the fore the pressing question of whether new slave states would be created, the issue that would tear the Union apart. Fears of the further extension of slavery and absorption of alien races, in turn, stymied southern efforts in the 1850s to acquire additional territory in the Caribbean and Central America. In foreign policy, as in domestic affairs, slavery dominated the politics of the antebellum era.

The mid-nineteenth century marked a transitional stage between the post-Napoleonic international system and the disequilibrium leading to World War I. The European great powers sustained a general peace interrupted only by limited, regional wars. England solidified its position as hegemonic power. The Royal Navy controlled the seas; by 1860, Britain produced 20 percent of the world's manufactures and dominated global finance. The industrial revolution generated drastic economic changes that would produce profound political and social dislocations. Revolutions in France and Central Europe in 1848 shook the established order momentarily and threatened general war. The two nations that prevented war at this point, Britain and Russia, fought with each other in 1854. The Crimean War, in turn, stirred "revisionist" ambitions across Europe and heightened British isolationism, helping to initiate in the 1850s a period of mounting instability. While avoiding a major war, the European powers used the "firepower gap" created by new technology to further encroach on the non-Western world. The opening of China and Japan to Western influence, in particular, had enormous long-range implications for world politics.2

America's global position changed significantly. The United States took steps toward becoming a Pacific power, asserting its interests in Hawaii, participating in the quasi-colonial system the European powers imposed on China, and taking the lead in opening Japan. Its relations with Europe were more important and more complex. Economically, the United States was an integral part of the Atlantic trading community. Politically, it remained a distant and apparently disinterested observer of European internal politics and external maneuvering. Americans took European interest in the Western Hemisphere most seriously. Still nominally committed to containing U.S. expansion, Britain and France dabbled in Texas and California. The British quietly expanded in Central America. In fact, the powers were preoccupied with internal problems and continental rivalries, and European ambitions in the Western Hemisphere were receding. Nevertheless, U.S. politicians used the European threat to generate support for expansion. Increasingly paranoid slaveholders saw the sinister force of abolitionism behind the appearance of every British gunboat and the machinations of every British diplomat.

The 1840s and 1850s brought headlong growth for the United States. As a result of a continued high birth rate and the massive immigration of Germans and Irish Catholics, the population nearly doubled again, reaching 31.5 million by 1860. Eight new states were admitted, bringing the total to thirty-three. Described with wonderment by foreign visitors as a "people in motion," Americans began spilling out into Texas and Oregon even before the region between the Mississippi River and Rocky Mountains was settled. Technology helped bind this vast territory together. By 1840, the United States had twice as much railroad track as all of Europe. Soon, there was talk of a transcontinental railroad. The invention of the telegraph and the rise of the penny press provided means to disseminate more information faster to a larger reading public, making it possible, in the words of publisher James Gordon Bennett, "to blend into one homogeneous mass . . . the whole population of the Republic." The antebellum era was the age of U.S. maritime greatness. Sleek clipper ships still ruled the seas, but in 1840 steamboat service was initiated to England, cutting the trip to ten days and quickening the pace of diplomacy.3

The economy grew exponentially after the Panic of 1837. Freed from dependence on Britain through development of a home market, America was no longer a colonial economy. In agriculture, cotton was still king, but western farmers with the aid of new technology launched a second agricultural revolution, challenging Russia as the world's leading producer of food. Mining and manufacturing became vital segments of an increasingly diversified economy. The United States was self-sufficient in most areas, but exports could make the difference between prosperity and recession; U.S. exports, mostly cotton, swelled from an average of $70 million during 1815–20 to $249 million in the decade before the Civil War.4

American approaches to the world appeared contradictory. On the one hand, technology was shrinking the globe. The United States was becoming part of the broader world community. Major metropolitan newspapers assigned correspondents to London and Paris. The government dispatched expeditions to explore Antarctica and the Pacific, the interior of Africa and South America, and the exotic Middle East. Curious readers devoured their reports. On their own initiative, merchants and missionaries in growing numbers went forth to spread the gospel of Americanism. Each group looked beyond its immediate objectives to the larger goal of uplifting other peoples. "One should not forget," New York Tribune London correspondent Karl Marx wrote, "that America is the youngest and most vigorous exponent of Western Civilization."5

Americans observed the outside world with great fascination. They longed "to see distant lands," observed writer James Fenimore Cooper, to view the "peculiarities of nations" and the differences "between strangers and ourselves."6 Some promoted development in other countries. The father of artist James McNeill Whistler oversaw the building of a railroad between Moscow and St. Petersburg. Growing numbers traveled abroad, many to Europe. These tourists carried their patriotism with them and found in the perceived inferiority of other nations confirmation of their own greatness. Those dissatisfied with America should tour the Old World, a Tennessean wrote, and they would "return home with national ideas, national love and national fidelity."7

On the other hand, U.S. policymakers and diplomats, once an experienced and cosmopolitan lot, were increasingly parochial, sometimes amateurish—and often proud of it. The presidential domination of foreign policy institutionalized by Jackson persisted under Polk. Of the chief executives who served in these years, only James Buchanan had diplomatic experience. Reflecting an emerging world role, the secretary of state had a staff of forty-three people by the 1850s; twenty-seven diplomats and eighty-eight consuls were posted abroad. Reforms limited consular appointments to U.S. citizens and restricted their ability to engage in private business.8 The diplomatic corps was composed more and more of politicians and merchants. Some served with distinction; others made Anthony Butler look good.

Americans wore their republicanism on their sleeves and even enshrined it in protocol. Polk displayed "American arrogance" toward diplomats who addressed him in a language other than English and dismissed as "ridiculous" the repeated ceremonial visits of the Russian minister to announce such trivia as the marriage of the tsar's son.9 Secretary of State William Marcy's "dress circular" of 1853 went well beyond Jackson's republicanism by requiring diplomats to appear in court in plain black evening clothes, the "simple dress of an American citizen." Parisians scornfully dubbed the U.S. minister "the Black Crow." Americans applauded. The person who represented his nation abroad should "look like an American, talk like an American, and be an American example," the New York Post proclaimed.10 New World ways some times rubbed off on Old World diplomats. Russian Eduard Stoeckl married an American and during his time in Washington served in a fire company where, in his words, he "run wid de lantern."11

The catchphrase "Manifest Destiny" summed up the expansionist thrust of the pre–Civil War era. Coined in 1845 by the Democratic Party journalist John L. O'Sullivan to justify annexation of Texas, Oregon, and California, the phrase meant, simply defined, that God had willed the expansion of the United States to the Pacific Ocean—or beyond. The concept expressed the exuberant nationalism and brash arrogance of the era. Divine sanction, in the eyes of many Americans, gave them a superior claim to any rival and lent an air of inevitability to their expansion. Manifest Destiny pulled together into a potent ideology notions dating to the origins of the republic with implications extending beyond the continent: that the American people and their institutions were uniquely virtuous, thus imposing on them a God-given mission to remake the world in their own image.12

Many Americans have accepted the rhetoric of Manifest Destiny at face value, seeing their nation's continental expansion as inevitable and altruistic, a result of the irresistible force generated by a virtuous people. Once viewed as a great national movement, an expression of American optimism and idealism, and the driving force behind expansion in the 1840s, Manifest Destiny's meaning and significance have been considerably qualified in recent years.13

For some Americans, no doubt, the rhetoric expressed idealistic sentiments. The acquisition of new lands and the admission of new peoples to the Union extended the blessings of liberty. Territorial expansion provided a haven for those fleeing oppression in other lands. Some Americans even believed that their nation had an obligation to uplift and regenerate "backward" peoples like Mexicans.

More often than not, Manifest Destiny covered and attempted to legitimate selfish motives. Southerners sought new land to perpetuate an economic and social system based on cotton and slavery and new slave states to preserve their power in Congress. People from all sections interested in the export trade coveted the magnificent ports of the Oregon country and California as jumping-off points to capture the rich commerce of East Asia. Restless, land-hungry westerners sought territory for its own sake. Some Americans argued that if the United States did not take Texas and California, the British and French would. At least, they might try to sustain independent republics that could threaten the security of the United States.

Manifest Destiny was also heavily tinged with racism. At the time of the Revolution and for years after, some Americans had sincerely believed that they could teach other peoples to share in the blessings of republicanism. The nation's remarkable success increasingly turned optimism into arrogance, however, and repeated clashes with Indians and Mexicans created a need to justify the exploitation of weaker people. "Scientific" theories of superior and inferior races thus emerged in the nineteenth century to rationalize U.S. expansion. Inferior races did not use the land properly and impeded progress, it was argued. They must give way before superior races, some, like African Americans, doomed to perpetual subservience, others, like Indians, to assimilation or extinction.14

Manifest Destiny was a sectional rather than national phenomenon, its support strongest in the Northeast and Northwest and weakest in the South, which supported only the annexation of Texas. It was also highly partisan. A second American party system emerged in the 1840s with the rise of two distinct political entities, roughly equal in strength, that set the agenda for national politics and took well-defined positions on major issues. The lineal descendants of Jefferson's Republicans, the Democrats rallied around the policies of the charismatic hero Andrew Jackson. The Whigs, a direct offshoot of the National Republicans along with some disaffected Democrats, formed in opposition to what its followers saw as the dangerous consolidation of executive power by "King Andrew I." Henry Clay was the leading national figure.15

The two parties differed sharply on the crucial issue of expansion. Looking backward to an idyllic agricultural society, the Democrats, like Jefferson, fervently believed that preservation of traditional republican values depended on commercial and territorial expansion. The Panic of 1837 and a growing surplus in agricultural production aroused their anxieties. Deeply alarmed by the rise of industrialization, urbanization, and class conflict in the Northeast, the very evils Jefferson had warned about, they saw expansion as a solution to the problems of modernization. The availability of new land in the West and acquisition of new markets for farm products would preserve the essentially agricultural economy upon which republicanism depended. An expanding frontier would protect Americans against poverty, concentration of population, exhaustion of the land, and the wage slavery of industrial capitalism. A sprawling national domain would preserve liberty rather than threaten it. Fortuitously, new technology like the railroad and telegraph that annihilated distance would permit administration of a vast empire. Expansion was fundamental to the American character, the Democrats insisted. The very process of the westward movement produced those special qualities that made Americans exceptional.16

More cautious and conservative, Whigs harbored deep fears of uncontrolled expansion. Change must be orderly, they insisted; the existing Union must be consolidated before the nation acquired more territory. The more rapidly and extensively the Union grew, the more difficult it would be to govern and the more it would be imperiled. The East might be left desolate and depopulated and sectional tensions increased. Whigs welcomed industrialism. In contrast to the Democrats, who promoted an activist role for government in external matters, they believed government's major task was to promote economic growth and disperse prosperity and capital in a way that would avert internal conflict, improve the lot of the individual, and enrich society. Government should promote the interests of the entire nation to ensure harmony and balance, ease sectional and class tensions, and promote peace. Like the Democrats, the Whigs talked of extending freedom, but their approach was passive rather than active. "The eyes of the world are upon us," Edward Everett asserted, "and our example will probably be decisive of the cause of human liberty."17

The increasingly inflammatory debate over slavery heightened conflict over expansion. As early as the 1830s, abolitionists began to attack slaveholder domination of the political system, creating one of the first pressure groups to influence U.S. foreign policy. The still volatile issue of Haiti became their cause célèbre. Abolitionists such as Lydia Maria Child and their frequent supporter John Quincy Adams condemned those who opposed recognition of the black republic because a "colored ambassador would be so disagreeable to our prejudice." They pleaded for recognition as a matter of principle and for trade. They pushed for opening of the British market for corn and wheat to spur prosperity in the Northwest, breaking the stranglehold of the "slavocracy" on the national government. Urging the United States to join Britain in an international effort to police the slave trade and abolish slavery, they passionately opposed the acquisition of new slave states.18

Increasingly paranoid slaveholders, on the other side, warned that a vast abolitionist conspiracy threatened their peculiar institution and indeed the nation. Haiti also had huge symbolic importance for them, the bloodshed, political chaos, and economic distress there portending the inevitable results of emancipation elsewhere. They saw abolitionism as an international movement centered in London whose philanthropic pretensions covered sinister imperialist designs. By abolishing slavery, the British could undercut southern production of staples, destroy the U.S. economy, and dominate world commerce and manufacturing. They denounced British high-handedness in policing the slave trade. They mongered among themselves morbid rumors of nefarious British plots to foment revolution among slaves in Cuba, incite Mexicans and Indians against the United States, and invade the South with armies of free blacks. They conjured graphic images of entire white populations being murdered except for the young and beautiful women reserved for "African lust." They condemned the federal government for not defending their rights from "foreign wrongs." They spoke openly of taking up the burden of defending slavery and even of secession. They ardently promoted the addition of new slave states. Pandering to the racial fears of northern Democrats, they suggested that extension of slavery into areas like Texas would draw the black population southward, even into Central America, ending the institution by natural processes and sparing the northern states and Upper South concentrations of free blacks.19

American expansionism in the 1840s was neither providential nor innocent. It resulted from design, rather than destiny, a carefully calculated effort by purposeful Democratic leaders to attain specific objectives that served mainly U.S. interests. The rhetoric of Manifest Destiny was nationalistic, idealistic, and self-confident, but it covered deep and sometimes morbid fears for America's security against internal decay and external danger. Expansionism showed scant regard for the "inferior" peoples who stood in the way. When combined with the volatile issue of slavery, it fueled increasingly bitter sectional and partisan conflict.20

Manifest Destiny had limits, most notably along the northern border with British Canada. Anglophobia and respect for Britain coexisted uneasily during the antebellum years. Americans still viewed the former mother country as the major threat to their security and prosperity and resented its refusal to pay them proper respect. At election time, U.S. politicians habitually twisted the lion's tail to whip up popular support. Upper-class Americans, on the other hand, admired British accomplishments and institutions. Responsible citizens understood the importance of economic ties between the two nations. A healthy respect for British power and a growing sense of Anglo-Saxon unity and common purpose—their "peculiar and sacred relations to the cause of civilization and freedom," O'Sullivan called it—produced very different attitudes and approaches toward Britain and Mexico. Americans continued to regard Canada as a base from which Britain could strike the United States, but they increasingly doubted it would be used. They also came to accept the presence of their northern neighbor and evinced a willingness to live in peace with it. Even the zealot O'Sullivan conceded that Manifest Destiny stopped at the Canadian border. He viewed Canadians as possible junior partners in the process of Manifest Destiny but did not press for annexation when the opportunity presented itself, envisioning a peaceful evolution toward a possible merger at some unspecified future time.21

Rebellions in Canada in 1837–38 raised the threat of a third Anglo-American war, but they evoked from most Americans a generally restrained response. At the outset, to be sure, some saw the Canadian uprisings, along with events in Texas, as part of the onward march of republicanism. Along the border, some Americans offered the rebels sanctuary and support. Incidents such as the burning of the American ship Caroline by Canadian soldiers on U.S. territory in December 1837 inflamed tensions. As it became clear that the rebellions were something less than republican in origin and intent, tempers cooled. Borderland communities where legal and illegal trade flourished feared the potential costs of war. President Martin Van Buren declared U.S. neutrality and after the Caroline incident dispatched War of 1812 hero Gen. Winfield Scott to enforce it. Traveling the border country by sled in frigid temperatures, often alone, Scott zealously executed his orders, expressing outrage at the destruction of the Caroline and promising to defend U.S. territory from British attack but warning his countrymen against provocative actions. On one occasion, he admonished hotheads that "except it be over my body, you shall not pass this line." Another time, as a preemptive measure, he bought out from under rebel supporters a ship he suspected was to be used for hostile activities. Scott's intervention helped ease tensions along the border. In terms of Manifest Destiny, Americans continued to believe that Canadians would opt for republicanism, but they respected the principle of self-determination rather than seeking to impose their views by force.22

Conflict over the long-disputed boundary between Maine and New Brunswick also produced Anglo-American hostility—and restraint. Local interests on both sides posed insuperable obstacles to settlement. For years, Maine had frustrated federal efforts to negotiate. Washington did nothing when the state government or its citizens defied federal law or international agreements. When Canadian lumberjacks cut timber in the disputed Aroostook River valley in late 1838, tempers flared, sparking threats of war. The tireless and peripatetic Scott hastened to Maine to reassure its citizens and encourage local officials to compromise. As with the Canadian rebellions, cooler heads prevailed. The so-called Aroostook War amounted to little more than a barroom brawl, the major casualties bloody noses and broken arms. But territorial dispute continued to threaten the peace.23

Conflict over the slave trade added a more volatile dimension to Anglo-American tension. In the 1830s, Britain launched an all-out crusade against that brutal and nefarious traffic in human beings. The United States outlawed the international slave trade in 1808 but, because of southern resistance, did little to stop it. Alone among nations, it refused to participate in multilateral efforts. Slave traders thus used the U.S. flag to cover their activities. The War of 1812 still fresh in their minds and highly sensitive to affronts to their honor, Americans South and North loudly protested when British ships began stopping and searching vessels flying the Stars and Stripes. An incident in November 1841 raised a simmering dispute to the level of crisis. Led by a cook named Madison Washington, slaves aboard the Creole en route from Virginia to New Orleans mutinied, took over the ship, killed a slave trader, and sailed to the Bahamas. Under pressure from the local population, British authorities released all 135 of the slaves because they landed on free territory. Furious with British interference with the domestic slave trade and more than ever convinced of a sinister plot to destroy slavery in the United States, southerners demanded restoration of their property and reparations. But the United States had no extradition treaty with Britain and could do nothing to back its citizens' claims.24

The Webster-Ashburton Treaty of 1842 solved several burning issues and confirmed the limits of Manifest Destiny. By this time, both sides sought to ease tensions. An avowed Anglophile, Secretary of State Daniel Webster viewed commerce with England as essential to U.S. prosperity. The new British government of Sir Robert Peel was friendly toward the United States and sought respite from tension to pursue domestic reform and address more urgent European problems. By sending a special mission to the United States, Peel struck a responsive chord among insecure Americans—"an unusual piece of condescension" for "haughty" England, New Yorker Philip Hone conceded.25 The appointment of Alexander Baring, Lord Ashburton, to carry out the mission confirmed London's good intentions. Head of one of the world's leading banking houses, Ashburton was married to an American, owned land in Maine, and had extensive investments in the United States. He believed that good relations were essential to the "moral improvement and the progressive civilization of the world." Ashburton steeled himself for the rigors of life in the "colonies" by bringing with him three secretaries, five servants, and three horses and a carriage. He and Webster entertained lavishly. Old friends, they agreed to dispense with the usual conventions of diplomacy and work informally. Webster even invited representatives of Maine and Massachusetts to join the discussions, causing Ashburton to marvel how "this Mass of ungovernable and unmanageable anarchy" functioned as well as it did.26

The novice diplomats used unconventional methods to resolve major differences. On the most difficult issue, the Maine–New Brunswick boundary, they worked out a compromise that satisfied hotheads on neither side and then used devious means to sell it. Each conveniently employed different maps to prove to skeptical constituents their side had got the better of the deal—or at least avoided losing more. Webster had more difficulty negotiating with Maine than with his British counterpart. He used $12,000 from a secret presidential slush fund to propagandize his fellow New Englanders to accept the treaty. This knot untied, the two men with relative ease set a boundary between Lake Superior and the Lake of the Woods. They defused the still-sensitive Caroline issue and agreed on an extradition treaty to help deal with matters like the Creole. Resolution of differences on the slave trade was most difficult. Eventually, the treaty provided for a joint squadron, but the United States, predictably, did not uphold the arrangement. The Webster-Ashburton Treaty testified to Anglo-American good sense when that quality seemed in short supply. It confirmed U.S. acceptance of the sharing of North America with British Canadians. It resolved numerous problems that might have provoked war and set the two nations on a course toward eventual rapprochement. The

threat of war eased in the Northeast, the United States could turn its attention to the Pacific Northwest and the Southwest.27

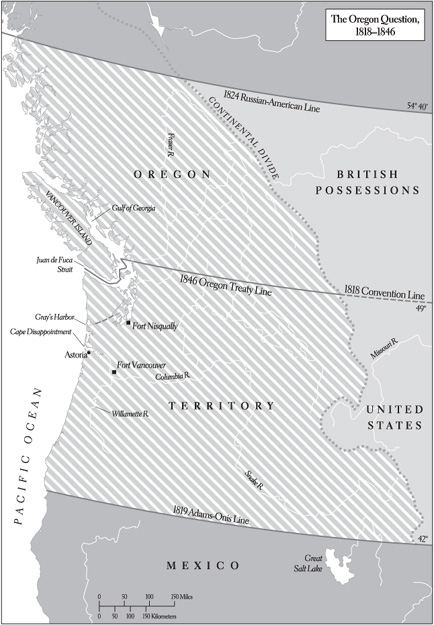

Oregon was a major exception to the budding Anglo-American accord. The joint occupation had outlived its usefulness by the mid-1840s. The Pacific Northwest became the focal point of a dangerous conflict sparked largely by bungling diplomacy and exacerbated by domestic politics in both countries and especially by the intrusion of national honor. The Oregon crisis brought out old suspicions and hatreds, nearly provoking an unnecessary and costly war.

In the 1840s, a long-dormant conflict in the Pacific Northwest sprang to life. British interests remained essentially commercial and quickened with the opening of China through the 1842 Treaty of Nanking. The ports of Oregon and Mexican California were perfectly situated for exploiting the commerce of East Asia, and merchants and sea captains pressed the government to take possession. Americans too saw links with the fabled commerce of the Orient, but their major interest in Oregon had shifted to settlement. Missionaries first went there to proselytize the Indians but established the permanent settlements that provided the basis for U.S. occupation. Driven from their homes by the depression of 1837 and enticed west by tales of lush farm lands, thousands of restless Americans followed in making the rugged, costly, and hazardous two-thousand-mile, six-month trek from St. Louis across the Oregon Trail. The return of the Great United States Exploring Expedition in June 1842 after an eighty-seven-thousand-mile voyage around the world stirred the American imagination and drew special attention to Oregon, "a storehouse of wealth in its forests, furs and fisheries," a veritable Eden on the Pacific.28 Oregon "fever" became an epidemic. By 1845, some five thousand Americans lived in the region and established a government to which even the once mighty Hudson's Bay Company paid taxes. They talked of admission to the Union, a direct challenge to the 1827 agreement with Britain. The "same causes which impelled our population . . . to the valley of the Mississippi, will impel them onward with accumulating force . . . into the valley of the Columbia," Secretary of State John C. Calhoun informed the British minister in 1844. The "whole region . . . is destined to be peopled by us."29

Along with Texas, Oregon became a volatile issue in the hotly contested presidential campaign of 1844. Western expansionists advanced outrageous claims all the way to 54° 40', the line negotiated with Russia in 1824 but far beyond the point ever contested with Britain. The bombastic Senator Thomas Hart Benton of Missouri even threatened war, proclaiming that "30–40,000 rifles are our best negotiators." Expansionist Democrats tried to link Texas with Oregon, trading southern votes for Oregon with western votes for Texas. The Democratic platform thus affirmed a "clear and unquestionable" claim to all of Oregon. The dark horse candidate, ardent expansionist James K. Polk of Tennessee, campaigned on the dubious slogan of the "re-annexation of Texas" and "reoccupation of Oregon."30

A crisis erupted within months after Polk took office. The forty-nine-year-old Tennessean was short, thin, and somewhat drab in appearance with a sad look, deep piercing eyes, and a sour disposition. Vain and driven, he set lofty expansionist goals for his administration, and by pledging not to seek reelection he placed self-imposed limits on his ability to achieve them. He was introverted, humorless, and a workaholic. His shrewdness and ability to size up friends and rivals had served him well in the rough-and-tumble of backcountry politics, and he had an especially keen eye for detail. But he could be cold and aloof. Parochial and highly nationalistic, he was impatient with the niceties of diplomacy and lacked understanding of and sensitivity to other nations and peoples.31

Polk's initial efforts to strike a deal provoked a crisis. Despite his menacing rhetoric, he realized that the United States had never claimed beyond the 49th parallel. Thus while continuing publicly to claim all of Oregon, he professed himself bound by the acts of his predecessors. He privately offered a "generous" settlement at the 49th parallel with free ports on the southern tip of Vancouver Island. An experienced and skillful diplomat, British minister Richard Pakenham might have overlooked Polk's posturing, but he too let nationalist pride interfere with diplomacy. Infuriated by Polk's pretensions of generosity, he refused to refer the proposal to London. The Foreign Office subsequently disapproved Pakenham's action, but the damage was done. Stung by the rejection of proposals he believed generous, Polk was probably relieved that Pakenham had taken him off the hook. He defiantly withdrew the "compromise," rejected British proposals for arbitration, reasserted claims to all of Oregon, and asked Congress to abrogate the joint occupation provision of the 1827 treaty. The "only way to treat John Bull is to look him straight in the eye," the tough-talking Tennessean later informed a delegation of congressmen.32

Polk's ill-conceived effort to stare down the world's greatest power nearly backfired. In the United States, at least momentarily, the breakdown of diplomacy left the field to the hotheads. "54-40 or fight," they shouted, and O'Sullivan coined the phrase that marked an era, proclaiming that the U.S. title to Oregon was "by the right of our manifest destiny to overspread and to possess the whole of the continent which Providence has given us for the development of the great experiment of Liberty." Conveniently forgetting his earlier willingness to compromise, Massachusetts congressman John Quincy Adams now found sanction in the Book of Genesis for possession of all of Oregon.33

Its future imperiled by domestic disputes over trade policy, the Peel government wanted to settle the Oregon issue, but not at the price of national honor. American pretensions aroused fury in London. Foreign Minister Lord Aberdeen retorted in Polk's own phrase that British rights to Oregon were "clear and unquestionable." Peel proclaimed that "we are resolved—and we are prepared—to maintain them."34 Responding directly to Adams, the Times of London sneered that a "democracy intoxicated with what it mistakes for religion is the most formidable apparition which can startle the world."35 Hotheads pressed for war. The army and navy prepared for action. Some zealots welcomed war with the United States as a heaven-sent opportunity to eliminate slavery. Whigs stood poised to exploit any sign of Tory weakness. In early 1846, the government emphasized that its patience was wearing thin. Revelation of plans to send as many as thirty warships to Canada underscored the warning.

The two nations steadied themselves in mid-1846 just as they teetered on the brink of war. Polk perceived that his bluster had angered rather than intimidated the British and that more of the same might lead to war. Congressional debates in early 1846 made clear that despite the political bombast a war for all of Oregon would not have broad support. Also on the verge of war with Mexico, the United States was not prepared to fight one enemy, much less two. Polk thus set out to ease the crisis he had helped to provoke by putting forth terms he might have offered earlier. Shortly after Congress passed the resolution giving notice of abrogation of the 1827 treaty, he quietly informed London of his willingness to compromise. Reports from Oregon that American settlers were firmly entrenched and that Britain should cut its losses reinforced Peel's eagerness for a settlement. London thus responded with terms nearly identical to those earlier outlined by the United States. Ever cautious, Polk took the extraordinary step of securing Senate approval before proceeding. Already at war with Mexico, the United States approved the treaty as drafted in London, a mere nine days passing between its delivery to the State Department and ratification. "Now we can thrash Mexico into decency at our leisure," the New York Herald exclaimed.36

The Oregon settlement accorded reasonably well with the specific interests of each signatory. It extended the boundary along the 49th parallel from the Rockies to the coast, leaving Vancouver Island in British hands and Juan de Fuca Strait open to both countries. Against Polk's wishes, it also permitted the Hudson's Bay Company to navigate the Columbia River. The United States had no settlements north of the 49th parallel and had never claimed that area before the 1840s. Despite the sometimes heated rhetoric, few Americans thought all of Oregon worth a war. Britain had long sought a boundary at the Columbia River, but the fur trade in the disputed area was virtually exhausted. Possession of Vancouver Island and access to Juan de Fuca Strait adequately met its maritime needs.

In each nation, other crises put a premium on settlement. The war with Mexico and Britain's refusal to interfere there made peace both urgent and expedient for the United States. Strained relations with France, problems in Ireland, and an impending political crisis at home made a settlement with the United States desirable, if not absolutely essential, for the British. Both sides recognized the importance of commercial ties and a common culture and heritage. In the United States, respect for British power and a reluctance on racial grounds to fight with Anglo-Saxon brethren made war unthinkable. Most important, both sides realized the foolishness of war. Often praised for his diplomacy, Polk deserves credit mainly for the good sense to extricate the nation from a crisis he had helped provoke.37

The Oregon treaty freed the United States to turn its attention southward. It also provided the much-coveted outlet on the Pacific as well as clear title to a rich expanse of territory including all of the future states of Washington, Oregon, Idaho, and parts of Montana and Wyoming. Along with the Webster-Ashburton Treaty, it eased a conflict that had been a fact of life since the Revolution. Americans generally agreed that their "Manifest Destiny" did not include Canada. Having contained U.S. expansion in the North, Britain increasingly learned to live with the upstart republic.

Conflict would continue, but only during the American Civil War would it assume dangerous proportions. Increasingly, the two nations would find that more united than divided them. Despite the rhetoric of Manifest Destiny, the United States and Britain had reached an agreement on the sharing of North America.38

"No instance of aggrandizement or lust for territory has stained our annals," O'Sullivan boasted in 1844, expressing one of the nation's most cherished and durable myths.39 Dubious when it was written, O'Sullivan's affirmation soon proved completely wrong. The Mexican-American conflict of 1846–48 was in large part a war of lust and aggrandizement. The United States had long coveted Texas. In the 1840s, California and New Mexico also became objects of its desire. With characteristic single-mindedness, Polk set his sights on all of them. He employed the same bullying approach used with the British, this time without backing off, provoking a war that would have momentous consequences for both nations.

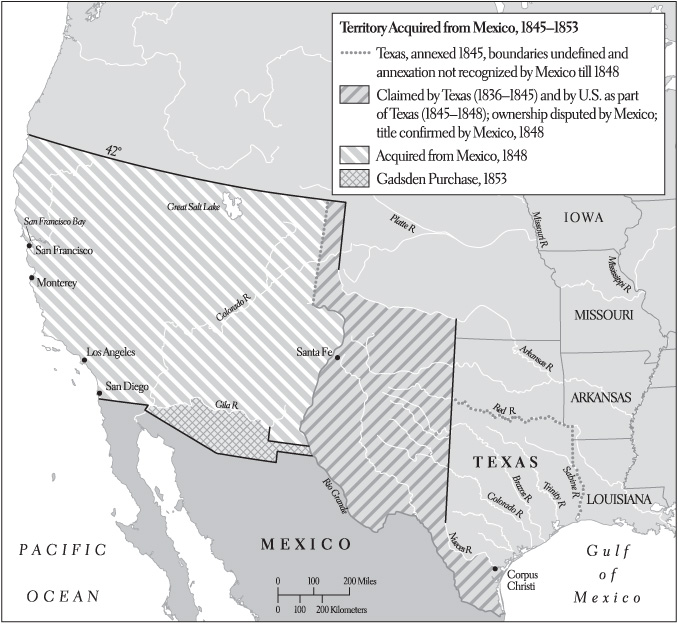

The United States government did not orchestrate a clever conspiracy to steal Texas, as Mexicans charged, but the result was the same. Lured to the "New El Dorado" by the promise of cheap cotton land, thirty-five thousand Americans with five thousand slaves had spilled into Texas by 1835. Alarmed by an immigration it once welcomed, the newly independent government of Mexico sought to impose its authority over the newcomers and abolish slavery. To defend their rights—and slaves—the Texans took up arms. After a crushing defeat at the Alamo, the subject of much patriotic folklore, they won a decisive victory at San Jacinto in April 1836.

An independent Texas presented enticing opportunities and vexing problems. Americans had taken a keen interest in the revolution. Despite nominal neutrality—and in marked contrast to the strict enforcement of neutrality laws along the Canadian border—they assisted the rebels with money, arms, and volunteers. Many Americans and Texans assumed that the "sister republic" would join the United States. From the outset, however, Texas got entangled with the explosive issue of slavery. Politicians handled it gingerly. Jackson refused to recognize the new nation until his successor, Van Buren, was safely elected. Eager for reelection, Van Buren warily turned aside Texas proposals for annexation.

By 1844, Texas had become the focal point of rumors, plots and counterplots, diplomatic intrigue, and bitter political conflict. Many Texans favored annexation, others preferred independence, some straddled the fence. Although unwilling to risk war with the United States, Britain and France sought an independent Texas and urged Mexico to recognize the new nation to keep it out of U.S. hands. Alarmist southerners fed each other's fears with lurid tales of sinister British schemes to abolish slavery in Texas, incite a slave revolt in Cuba, and strike a "fatal blow" against slavery in the United States, provoking a race war "of the most deadly and desolating character." In the eyes of some southerners, Britain's real aim was to throw an "Iron Chain" around the United States to gain "command of the commerce, navigation and manufactures of the world" and to reduce its former colonies to economic "vassalage."40

For Americans of all political persuasions, the Union's future depended on the absorption of Texas. Whigs protested that annexation would violate principles Americans had long believed in and might provoke war with Mexico.41 Abolitionists warned of a slaveholders' conspiracy to retain control of the government and perpetuate the evils of human bondage.42 On the annexation of Texas "hinges the very existence of our Southern Institutions," South Carolinian James Gadsden warned Calhoun, "and if we of the South now prove recreant, we will or must [be] content to be Heawers of wood and Drawers of Water for our Northern Brethren."43

In 1844, with an independent Texas a distinct possibility, the Virginian and slaveholder John Tyler, who had become president in 1841 on the death of William Henry Harrison, took up the challenge Jackson and Van Buren had skirted. A staunch Jeffersonian, Tyler is often dismissed as an advocate of states' rights who sought to acquire Texas mainly to protect the institution of slavery. In fact, he was a strong nationalist who pushed a broad agenda of commercial and territorial expansion in hopes of uniting the nation, fulfilling its God-given destiny, and gaining reelection.44 Seeking to win over the Democrats or rally a party of his own, he pressed vigorously for annexation of Texas. A treaty might have passed the Senate in 1844 had not Calhoun stiffened the opposition by publicly defending slavery. Once the 1844 election was over, lame duck Tyler again proposed admission. Instead of a treaty of annexation, which would have required a two-thirds vote in the Senate, he sought a joint resolution for admission as a state, requiring only a simple majority, on the questionable constitutional grounds that new states could be admitted by act of Congress. The resolution passed after heated debate and drawn-out maneuvering, winning in the Senate by a mere two votes. Texas agreed to the proposals, initiating the process of annexation.45

Mexico considered annexation an act of war. Born in 1821, the nation had great expectations because of its size and wealth in natural resources but had suffered economic devastation during its war of independence. The flight of capital abroad in its early years reduced it to bankruptcy. It was also afflicted by profound class, religious, and political divisions. The central government exercised at best nominal authority over the vast outer provinces. Political instability was a way of life. Rival Masonic lodges contended for power, ironic in a predominantly Catholic country. Coup followed coup, sixteen presidents serving between 1837 and 1851. The "volcanic genius" Antonio Lopez de Santa Anna embodied the chaos of Mexican political life. Brilliant but erratic, skilled at mobilizing the population but bored with the details of governance, he served eleven times as president. A master conspirator, he switched sides with alacrity and was said even to intrigue against himself. Noted for his flamboyance, he buried with full military honors the leg he had lost in battle. When he was later repudiated, his enemies dug up the leg and ceremoniously dragged it through the streets.46

Too proud to surrender Texas but too weak and divided to regain it by force, Mexicans justifiably (and correctly) feared that acquiescence in annexation could initiate a domino effect that would cost them additional territory. In their view, the United States had encouraged its citizens to infiltrate Texas, incited and supported their revolution, and then moved to absorb the renegade state. They denounced U.S. actions as "the most scandalous violation of the law of nations," the "most direct spoliation, which has been seen for ages."47 When the annexation resolution passed Congress, Mexico severed diplomatic relations.

A dispute over the Texas boundary exacerbated Mexican-American conflict. Under Spanish and Mexican rule, the province had never extended south of the Nueces River; Texas had never established its authority or even a settlement beyond that point. On the basis of nothing more than an act of its own congress and the fact that Mexican forces withdrew south of the Rio Grande after San Jacinto, Texas had claimed territory to the Rio Grande. Despite the dubious claim and the uncertain value of the barren land, Polk firmly supported the Texans. He ordered Gen. Zachary Taylor to the area to deter a possible Mexican attack and subsequently instructed him to take a position as close to the Rio Grande as "prudence will dictate."48

Polk also set out to acquire California. Only six thousand Mexicans lived there. Mexico had stationed in its northernmost province an army of fewer than six hundred men to control a huge territory. In October 1842, acting on rumors of war with Mexico, Cmdre. Thomas ap Catesby Jones sailed into Monterey, captured the local authorities, and raised the U.S. flag. When he learned there was no war, he lowered the flag, held a banquet of apology for his captives, and sailed away.49 Americans were increasingly drawn to California. Sea captains and explorers spoke with wonderment of the lush farmland and salubrious climate of this land of unlimited bounty and "perpetual spring," "one of the finest countries in the world," in the words of consul Thomas Larkin. The "safe and capacious harbors which dot her western shore," an Alabama congressman added, "invite to their bosoms the rich commerce of the East."50 American emigration to California grew steadily, raising the possibility of a replay of the Texas game. Signs of British interest increased the allure of California and the sense of urgency in Washington. Polk early committed himself to its acquisition, alerted Americans in the area to the possibility of war, and ordered his agents to discourage foreign acquisition.

Polk also wielded a "diplomatic club" against Mexico in the millions of dollars in claims held by U.S. citizens against its people and government. Many of the claims were inflated, some were patently unjust, and most derived from profiteering at Mexico's expense. They were based on the new international "law" imposed by the leading capitalist powers that secured for their citizens the same property rights in other countries they had at home.51 A commission had scaled the claims back to $2.5 million. Mexico made a few payments before a bankrupt treasury forced suspension in 1843. Americans charged Mexico with bad faith. Mexico denounced the claims as a "tribute" it was "obliged to pay in recognition of U.S. strength."52

Polk's approach to Mexico was dictated by the overtly racist attitudes he shared with most of his countrymen. Certain of Anglo-Saxon superiority, Americans scorned Mexicans as a mixed breed, even below free blacks and Indians, "an imbecile, pusillanimous race of men . . . unfit to control the destinies of that beautiful country," a "rascally perfidious race," a "band of pirates and robbers."53 Indeed, they found no difficulty justifying as part of God's will the taking of fertile land from an "idle, thriftless people." They assumed that Mexico could be bullied into submission or, if foolish enough to fight, easily defeated. "Let its bark be treated with contempt, and its little bite, if it should attempt it, [be] quickly brushed aside with a single stroke of the paw," O'Sullivan exclaimed.54 Some Americans even assumed that Mexicans would welcome them as liberators from their own depraved government.

Given the intractability of the issues and the attitudes on both sides, a settlement would have been difficult under any circumstances, but Polk's heavy-handed diplomacy ensured war. There is no evidence to confirm charges that he plotted to provoke Mexico into firing the first shot.55 He seems rather to have hoped that by bribery and intimidation he could get what he wanted without war and to have expected that if war did come, it would be short, easy, and inexpensive. His sense of urgency heightened in the fall of 1845 by new and exaggerated reports of British designs on California, he tightened the noose. In December 1845, he revived the Monroe Doctrine, warning Britain and France against trying to block U.S. expansion. He deployed naval units off the Mexican port of Veracruz and ordered Taylor to the Rio Grande. He sent agents to Santa Fe to bribe provincial authorities of the New Mexico territory and persuade its residents of the benefits of U.S. rule. He dispatched secret orders to the navy's Pacific squadron and Larkin that should war break out or Britain move overtly to take California they should occupy the major ports and encourage the local population to revolt. He may also have secretly ordered the adventurer—and notorious troublemaker—John Charles Frémont to go to California. In any event, Frémont in the spring of 1846 turned abruptly south from an expedition in Oregon and began fomenting revolution in California.56

Having encircled Mexico with U.S. military power and begun to chip away at its outlying provinces, Polk set out to force a deal. Mistakenly concluding that Mexico had agreed to receive an envoy, he sent Louisianan John Slidell to Mexico City. The president's instructions make clear the sort of "negotiations" he sought. Slidell was to restore good relations with Mexico while demanding that it surrender on the Rio Grande boundary and relinquish California, no mean task. The United States would pay Mexico $30 million and absorb the claims of its citizens.

The predictable failure of Slidell's mission led directly to war. Mexico had agreed only to receive a commissioner to discuss resumption of diplomatic relations. Slidell's mere presence destabilized an already shaky government. When he moved on to the capital, violating the explicit instructions of Mexican officials, his mission was doomed.57 After Mexico refused to receive him, he advised Polk that the United States should not deal further with them until it had "given them a good drubbing."58 Polk concurred. After learning of Slidell's return, he began drafting a war message. In the meantime, Taylor took a provocative position just north of the Rio Grande, his artillery trained on the town of Matamoros. Before the war message could be completed, Washington learned that Mexican troops had attacked one of Taylor's patrols. American blood had been shed on American soil, Polk exclaimed with exaggeration. The administration quickly secured its declaration of war.

The Mexican-American War resulted from U.S. impatience and aggressiveness and Mexican weakness. Polk and many of his countrymen were determined to have Texas to the Rio Grande and all of California on their own terms. They might have waited for the apples to fall from the tree, to borrow John Quincy Adams's Cuban metaphor, but patience was not among their virtues. Polk appears not to have set out to provoke Mexico into what could be used as a war of conquest. Rather, contemptuous of his presumably inferior adversaries, he assumed he could bully them into giving him what he wanted. Mexico's weakness and internal divisions encouraged his aggressiveness. A stronger or more united Mexico might have deterred the United States or acquiesced in the annexation of Texas to avoid war, as the British minister and former Mexican foreign minister Lucas Alaman urged. By this time, however, Yankeephobia was rampant. Mexicans deeply resented the theft of Texas and obvious U.S. designs on California. They viewed the United States as the "Russian threat" of the New World. Incensed by the racist views of their northern neighbors, they feared cultural extinction. Newspapers warned that if the North Americans were not stopped in Texas, Protestantism would be imposed on the Mexican people and they would be "sold as beasts."59 Fear, anger, and pride made it impossible to acquiesce in U.S. aggression. Mexico chose war over surrender.

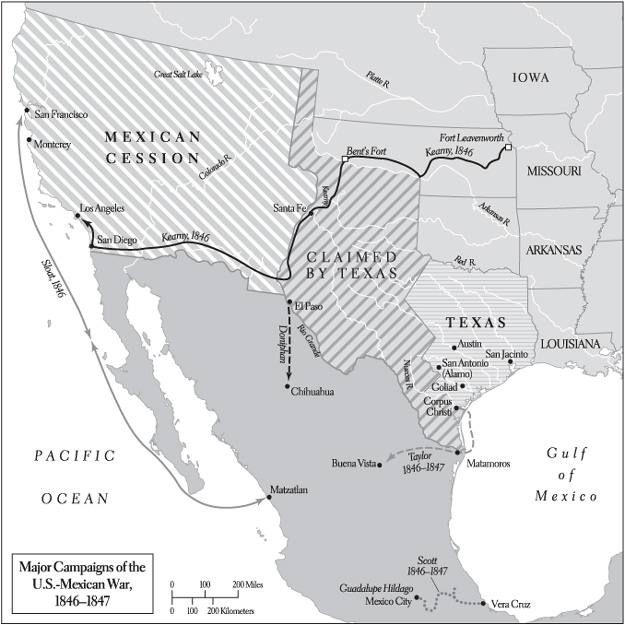

Polk's strategy for fighting Mexico reflected the racist assumptions that got him into war. Certain that an inferior people would be no match for Americans, he envisioned a war of three to four months. The United States would secure control of Mexico's northern provinces and use them to force acceptance of the Rio Grande boundary and cession of California and New Mexico.

In a strictly military sense, Polk's estimate proved on the mark. Using artillery with devastating effect, Taylor drove Mexican attackers back across the Rio Grande. Over the next ten months, he defeated larger armies at Monterrey and Buena Vista, fueling popular excitement, making himself a national hero, and gaining control of much of northern Mexico. In the meantime, Cmdre. Robert Stockton and Frémont backed the so-called Bear Flag Revolt of Americans around Sacramento and proclaimed California part of the United States. Colonel Stephen Kearney's forces took New Mexico without resistance. To facilitate negotiations, Polk permitted the exiled Santa Anna to go back to Mexico where, in return, he was to arrange a settlement.

War is never as simple as its planners envision, however, and despite smashing military successes, Polk could not impose peace. Mexico turned out to be an "ugly enemy," in Daniel Webster's words. "She will not fight—& will not treat."60 Despite crushing defeats, the Mexicans refused to negotiate on U.S. terms. They mounted a costly and frustrating guerrilla war against the invaders, "hardly . . . a legitimate system of warfare," Americans snarled, additional evidence (if any was needed) of Mexican debasement.61 Santa Anna did Polk's deviousness one better, using the United States to get home and then mobilizing fierce opposition to the invaders. "The United States may triumph," a Mexican newspaper proclaimed defiantly, "but its prize, like that of the vulture, will lie in a lake of blood."62

The United States by mid-1847 faced the grim prospect of a long and costly war. Annoyed that Taylor had not moved more decisively and alarmed that the general's martial exploits could make him a formidable political rival, the fiercely partisan Polk shifted his strategy southward, designing a combined army-navy assault against Veracruz, the strongest fortress in the Western Hemisphere, to be led by Gen. Winfield Scott and followed by an overland advance on Mexico City. Demonstrating the emerging professionalism of U.S. forces, Scott in March 1847 launched the first large-scale amphibious operation in the nation's history. After a siege of several weeks, he took Veracruz. In April, he defeated the ubiquitous Santa Anna at Cerro Gordo and began a slow, bloody advance to Mexico City. In August, five miles from the city, he agreed to an armistice.

Even this smashing success did not end the conflict. Fearing Scott as a potential political rival, Polk denied him the role of peacemaker, dispatching a minor figure, State Department clerk Nicholas Trist, to negotiate with Mexico. Shortly after his arrival, Trist fell into a childish and nasty spat with Scott that left the two refusing to speak to each other. The untimely feud may have botched an opportunity to end the war. More important, despite the imminent threat to their capital, the Mexicans stubbornly held out, insisting that the United States give up all occupied territory, accept the Nueces boundary, and pay the costs of the war. Santa Anna used the armistice to strengthen the defenses of the capital. With the breakdown of negotiations, Polk angrily recalled Trist, terminated the armistice, and ordered Scott to march on Mexico City.

The Mexican-American War was the nation's first major military intervention abroad and its first experience with occupying another country. Americans brought to this venture the ethos of the age, clearly defined notions of their own superiority, and the conviction that they were "pioneers of civilization," as contemporary historian William H. Prescott put it, bringing to a benighted people the blessings of republicanism. Given

the crushing impediment of racism they also brought with them, and the difficulties of living in a different climate and sometimes hostile environment, U.S. forces comported themselves reasonably well. There were atrocities, to be sure, and the Polk administration imposed a heavy burden on a defeated people by forcing them to pay taxes to finance the occupation. As a matter of military expediency, however, and to behave as they felt citizens of a republic should, the Americans tried to conciliate the population in most areas they moved through. Little was done to impose republicanism, and the impact of U.S. intervention on Mexico appears to have been slight. The areas occupied were briefly Americanized and some elements of American culture survived in Mexico, but the mixing of peoples was at best superficial and the gap between them remained wide. Ironically, the impact of intervention may have been greater on the occupiers, manifesting itself in such things as men's fashions and hairstyles and the incorporation of Spanish words and phrases into the language and as U.S. place names. The experience of fighting in a foreign land exposed Americans to a foreign culture, challenging their parochialism and contributing to the growth of national self-awareness.63

The war bitterly divided the United States. Citizens responded to its outbreak with an enthusiasm that bordered on hysteria. The prospect of fighting in an exotic foreign land appealed to their romantic spirit and sense of adventure. War provided a diversion from the mounting sectional conflict and served as an antidote for the materialism of the age. In the eyes of some, it was a test for the republican experiment, a way to bring the nation back to its first principles. "Ho, for the Halls of the Montezumas" was the battle cry, and the call for volunteers produced such a response that thousands had to be turned away. This was the first U.S. war to rest on a popular base. Stirring reports of battles provided to avid readers through the penny press by correspondents on the scene stimulated great popular excitement.64

Like most U.S. wars, this conflict also provoked opposition. Religious leaders, intellectuals, and some politicians denounced it as "illegal, unrighteous, and damnable" and accused Polk of violating "every principle of international law and moral justice."65 Abolitionists claimed that this "piratical war" was being waged "solely for the detestable and horrible purpose of extending and perpetuating American slavery."66 Whigs sought to exploit "Mr. Polk's War." The young congressman Abraham Lincoln introduced his famous "spot resolution," demanding to know precisely where Polk believed American blood had been shed on American soil. Senator Tom Corwin of Ohio declared that if he were a Mexican he would greet the invaders "with bloody hands" and welcome them to "hospitable graves." Polk's own Democratic Party was increasingly divided, the followers of both Calhoun and Van Buren opposing him. The opposition to the Mexican War was not as crippling as that during the War of 1812. Anti-war forces were weakened by the extremism of people such as Corwin and by their own ambivalence. Many who fervently opposed the war saw no choice but to support U.S. troops in the field. Opponents of the war also recognized that the nation as a whole supported the war. Remembering the fate of the Federalists, Whigs in Congress tempered their opposition. In any event, they lacked the votes to block administration measures. Until after the Whigs won control of the House of Representataives in the 1846 elections, they could do little more than protest and make life difficult for Polk.67

Pinched economically from the growing cost of the war and frustrated that an unbroken string of military successes had not produced peace, Americans by 1848 grew impatient. Divisions in both parties sharpened. When the Wilmot Proviso, banning slavery in any territory acquired from Mexico, was introduced in Congress in August 1846, it brought that explosive issue to the surface. Outraged by Mexico's continued defiance and excited by tales of vast mineral wealth, "All Mexico" Democrats pushed for annexation of the entire country. At the other extreme, critics urged Polk's impeachment "as an indemnity to the American people for the loss of 15,000 lives . . . in Mexico."68

A peace settlement emerged almost by accident. After two weeks of heavy fighting, Scott's army forced the surrender of the heavily defended capital. "I believe if we were to plant our batteries in Hell the damned Yankees would take them from us," a stunned Santa Anna remarked after the fall of the supposedly impregnable fortress of Chapultepec.69 Fearing a drawn-out war, Trist ignored Polk's orders to come home. Acting without authority, he negotiated a treaty that met the president's original demands. Mexico recognized the Rio Grande boundary and ceded upper California and New Mexico. The United States was to pay $15 million plus U.S. claims against Mexico.

Outraged by Trist's disobedience, Polk would have liked to take more territory to punish Mexico for its insolence. Ironically, the very racism that drove the United States into Mexico limited its conquests. "We can no more amalgamate with her people than with negroes," the former president's nephew and namesake Andrew Jackson Donelson observed. "The Spanish blood will not mix well with the Yankee," Prescott added.70 Concern about the absorption of an alien population and the prospect of peace took the steam out of the All Mexico movement. Facing sharpening divisions at home, Polk felt compelled to accept the treaty negotiated by that "impudent and unqualified scoundrel." Some Whigs opposed it because it gave the United States too much territory, others because the price was too high. In the final analysis, peace seemed preferable to more bloodshed. The treaty passed the Senate on March 10, 1848, by a bipartisan vote of 36 to 14. The Treaty of Guadalupe Hidalgo, in Philip Hone's apt phrase, was "negotiated by an unauthorized agent, with an unacknowledged government, submitted by an accidental president to a dissatisfied Senate."71

For Trist, the diplomat who had taken peace into his own hands, the reward was abuse from a vindictive boss. He was fired from his State Department post and not paid for his service until some twenty-five years later, shortly before his death.

For Mexico, the war was a devastating blow to the optimism that had marked its birth, perhaps the supreme tragedy in its history. When Santa Anna was shown maps of his country making clear for the first time the enormity of its losses, he wept openly. Mexico plunged deeper into debt. With half its territory gone, war raging in Yucatán, agrarian revolts sweeping the heartland, and Indian unrest in the north, the nation seemed near falling apart. Military defeat brought despair to leadership groups. Liberals questioned Mexico's capacity for nationhood. Conservatives concluded that republicanism was tantamount to anarchy and that they should look to Europe for models, even to monarchy. It was the "most unjust war in history," Alaman lamented, "provoked by the ambition not of an absolute monarchy but of a republic that claims to be at the forefront of nineteenth century civilization."72

For the United States, the war brought a vast bounty, adding 529,000 square miles to the national domain, coveted outlets on the Pacific, and the unanticipated boon of California gold. If Texas is added, the booty totals about 1.2 million square miles, one-third of the nation's present territory. All of this for thirteen thousand dead, an estimated $97 million in war costs, and the $15 million paid Mexico. North Americans saw the war as a great event in their own and indeed in world history. Success against Mexico demonstrated, Polk insisted, the "capacity of republican governments to prosecute successfully a just and necessary foreign war with all the vigor usually attributed to more arbitrary forms of government."73 For a people still unsure of their bold experiment, the war confirmed their faith in republicanism and seemed to earn them new respect abroad. Some Americans even saw the European revolutions of 1848 as extensions

of the great test between monarchy and republicanism that began on the battlefields of Mexico. "The whole civilized world resounds with American opinions and American principles," declared Speaker of the House of Representatives Robert Winthrop in a victory oration on July 4, 1848.74

The celebration of victory obscured only momentarily the war's darker consequences. It aroused among Latin Americans growing fear of what was already commonly labeled the "colossus of the North." Most important, acquisition of the vast new territory opened a veritable Pandora's box of troubles at home. From the Wilmot Proviso to Fort Sumter, the explosive issue of extending slavery into the territories dominated the political landscape, setting off a bitter and ultimately irreconcilable conflict. Polk's victory thus came at a huge price, setting the nation on the road to civil war.75

Rising with each word to new heights of exuberance, Secretary of State Daniel Webster proclaimed in 1851 that it was America's destiny to "command the oceans, both oceans, all the oceans."76 Some of the same forces that drove the United States across the continent in the 1840s propelled it into the Pacific and East Asia. Trade, of course, was a major factor. The Panic of 1837 and growing concern with surplus agricultural productivity heightened the importance of finding new markets. Whigs like Webster saw commercial expansion as essential to domestic well-being and international stability. Democrats viewed it as essential to sustain the agricultural production that would safeguard the nation from the threats of manufacturing, economic distress, and monopoly. The lure of East Asian trade played a crucial role in the quest for Oregon and California; their acquisition, in turn, quickened interest in the Pacific and East Asia. "By our recent acquisitions in the Pacific," Secretary of the Treasury Robert Walker proclaimed in 1848, "Asia has suddenly become our neighbor, with a placid intervening ocean inviting our steamships upon the trade of a commerce greater than all of Europe combined."77 It was no accident that in the 1840s the United States began to formulate a clear-cut policy for the Pacific region.

The Pacific Ocean was a focal point of international rivalry in the mid-nineteenth century, the United States an active participant. American merchants entered the China trade before 1800. From the first years of the century, sea captains and traders sailed up and down the west coast of the American continents and far out into the Pacific. Americans dominated the whaling industry, pursuing their lucrative prey from the Arctic Ocean to Antarctica and California to the Tasman Sea. Americans were the first to set foot on Antarctica. During its dramatic four-year voyage around the world, the Great United States Exploring Expedition, commanded by Capt. Charles Wilkes, charted the islands, harbors, and coast lines of the Pacific. The U.S. Navy assumed a constabulary role, supporting enterprising Americans in far-flung areas. United States citizens on their own initiative carved out interests and pushed the government to defend them.78

This was especially true in Hawaii, where Americans predominated by midcentury. Missionaries and merchants began flocking there as early as 1820 and by the 1840s played a major role in the life of the islands. United States trade far surpassed that of the nearest rival, Great Britain. New England Congregationalist missionaries established schools and printing presses and enjoyed unusually large conversion rates. As in other areas, Western disease ravaged the indigenous population and Western culture assaulted local customs. But the missionaries also helped Hawaii manage the jolt of Westernization without entirely giving in. Americans assisted Hawaiian rulers in adapting Western forms of governance and in protecting their sovereignty. On the advice of missionary William Richards, King Kamehameha II mounted a diplomatic offensive in the 1840s to spare his people from falling under European domination, pushing Hawaii toward the U.S. orbit.79

A result was the so-called Tyler Doctrine of 1842, the end of official indifference toward Hawaii. Protestant missionaries had also persuaded the Hawaiians to discriminate against French Catholics. When the French government threatened to retaliate, a nervous and opportunistic Kamehameha sought from the United States, Britain, and France a tripartite guarantee of Hawaiian independence. To get action from Washington, Richards even hinted at Hawaii's willingness to accept a British protectorate. Webster and the "Pacific-minded" Tyler perceived Hawaii's importance as the "Malta of the Pacific," a vital link in the "great chain" connecting the United States with East Asia. Unwilling to take on risky commitments, they rejected a tripartite guarantee and refused even to recognize Hawaii's sovereignty. The Tyler Doctrine did, however, claim special U.S. interests in Hawaii based on proximity and trade. It made clear that if other powers threatened Hawaii's independence the United States would be justified in "making a decided remonstrance." Seeking to protect U.S. interests at minimum cost, the doctrine claimed Hawaii as a U.S. sphere of influence and firmly supported its independence, establishing a policy that would last until annexation.80

As secretary of state under Millard Fillmore, Webster in 1851 went a step further. Under the Tyler Doctrine, U.S. interests expanded significantly. Hawaii resembled a "Pacific New England" in culture and institutions.81 The development of oceangoing steam navigation increased its importance as a possible coaling station. Again threatened by French gunboat diplomacy, Kamehameha II in 1851 signed a secret document transferring sovereignty to the United States in the event of war. Webster and Fillmore steered clear of annexation and warned missionaries against provoking conflict with France. At the same time, in a strongly worded message of July 14, 1851, the secretary of state asserted that the United States would accept no infringement on Hawaiian sovereignty and would use force if necessary. Webster's willingness to go this far reflected the increased importance of Hawaii due to the acquisition of Oregon and California and rising U.S. interest in East Asia. His threats infuriated the French, but extracted from them a clear statement respecting Hawaiian sovereignty.82

The United States' concern for Hawaii was tied to the opening of China. Until the 1840s, East Asia remained largely closed to the West because of policies rigorously enforced by both China and Japan. China's isolationist policy reflected a set of highly ethnocentric ideas that viewed the Celestial Kingdom as the center of the universe and other peoples as "barbarians." The notion of equal relations among sovereign states had no place in this scheme of things. Ties with other nations were permitted only on a "tributary" basis. Foreign representatives had to pay tribute to the emperor through various rituals including the elaborate series of prostrations known as the ko-tow. In the 1790s, China began to permit limited trade—to make available to the barbarians necessities such as tea and rhubarb, its officials said—but it was restricted in volume and tightly regulated by Chinese merchants. Japanese exclusion was less ideological but more rigid. Viewing outsiders and especially missionaries as threats to internal stability, they kept out all but a handful of Dutch traders, who operated only on an island in Nagasaki harbor. Indeed, the Japanese so feared contamination that they prohibited their own people from going abroad and forbade those who did so from returning.83

By the 1840s, the European powers had far outstripped the isolated Asians in economic and military power. Eager for expanded trade and outlets for missionary activity, they challenged Chinese and Japanese restrictions. In the United States, producers of cotton and tobacco fancied huge profits from access to China's millions. Some Americans even envisioned their country as an entrepôt for a global trade in which European goods would be imported, transshipped across the continent, and then sent from San Francisco to East Asian ports by steamship.

The missionary impulse reinforced commercial drives. The 1840s was a period of intense religious ferment in the United States, and numerous Protestant sects stepped up evangelizing activities around the world. China and Japan, which seemed particularly decadent and barbaric, offered perhaps the greatest challenge. The Chinese empire was "so vast, so populous, and so idolatrous," one missionary exclaimed, "that it cannot be mentioned by Christians without exciting statements of the deepest concern." The handful of American missionaries already in China questioned its rulers right to make "a large part of the earth's surface . . . impassable." They also emphasized China's weakness and pressed for its opening—by force if necessary.84

Britain took the lead. To redress a balance of trade chronically favoring China, Western merchants, Americans included, had taken to the illegal and profitable sale of opium. Chinese officials objected on economic grounds and also because of the baneful effects on their people. When they attempted to stop the trade, the British responded with force and used their trouncing of China in the so-called Opium War as leverage to pry it open. The Treaty of Nanking (1842), imposed on China by the British, marked the end of Chinese exclusion, putting into effect a system of blatantly discriminatory unequal treaties that reversed China's traditional way of dealing with other nations. The Chinese opened five ports to trade with Britain, eliminated some of the more obnoxious regulations imposed on British merchants, and opened their tariff to negotiation. They also ceded Hong Kong and agreed to a practice called extraterritoriality by which British citizens in China were tried under their own law rather than Chinese.

Through what came to be known as hitchhiking imperialism, the United States took advantage of British gains. Shortly after the Treaty of Nanking, Tyler sent Massachusetts merchant Caleb Cushing to negotiate with China. The two nations approached each other across a yawning geographical and cultural chasm. Contemptuous of Chinese pretensions of superiority, the administration instructed its delegation to take with them a globe (if one could be found) so that "the celestials may see that they are not the Central Kingdom." Cushing was to use religion as an excuse not to perform the ko-tow.85 Chinese viewed the United States as "the most remote and least civilized" of Western nations—an "isolated place outside the pale." Their chief negotiator instructed the emperor to use a "simple and direct style" so his meaning would be clear. Hoping to play the barbarians against each other, the Chinese were willing to deal. In the Treaty of Wang-hsia (1844), they granted the United States the same commercial concessions as Britain. Most important, they agreed to a most-favored-nation clause that would automatically concede to the United States terms given any other nation.86

During the 1850s, the West made further inroads, implementing an increasingly exploitative form of quasi-colonialism. Capitalizing on China's prolonged and bloody civil war—the so-called Taiping Rebellion lasted fifteen years and took as many as forty million lives—and rewarding its intransigence and insults with high-handedness, the Europeans negotiated at gunpoint treaties that opened additional ports, permitted navigation into the interior, forced toleration of missionaries, legalized the opium trade, and, by fixing a maximum tariff of 5 percent, deprived China of control over its own economy.

Americans then and later fancied themselves different from the Europeans in dealing with China, and to some extent they were. Until the end of the century, at least, the United States remained a minor player. Trade with China increased significantly but remained only a small portion of China's commerce with the West. American missionaries were few in number and small in impact. "Our preaching is listened to by a few, laughed at by many, and disregarded by most," one missionary lamented.87 Americans generally refrained from the use of force. Some, like minister John Ward, sent to ratify the 1858 treaties of Tientsin, observed Chinese conventions; Ward even rode in a mule cart traditionally deserved for tributaries, earning the contempt of his European counterparts and praise from his countrymen for Yankee practicality.88

The differences were more of form than substance. The United States sometimes participated in gunboat diplomacy and regularly used the most-favored-nation clause to secure concessions extorted by the Europeans at cannon's mouth. Like the Europeans, Americans generally looked down on the Chinese—one diplomat described a "china-man" as "surely the most grotesque animal."89 Some Chinese perceived a subtle difference and tried to exploit it, but in general they made little distinction. "The English barbarians' craftiness is manifold, their proud tyranny is uncontrollable," one Chinese official observed. "Americans do nothing but follow in their direction."90