Chapter One

‘We must away ere break of day’

IN ‘AN UNEXPECTED Party’, the first chapter of The Hobbit, the respectable well-to-do Mr Bilbo Baggins finds himself entertaining a whole troop of vagrants who turn up for afternoon tea unexpectedly. The previous day he had made the mistake of inviting one of them, an old family friend, little suspecting that he would bring twelve of his companions with him, many of whom arrive early, in dribs and drabs, in ones or twos, demanding food and drink. And their talk scares him. It is all about ‘mines and gold and troubles with the goblins, and the depredations of dragons’; and soon the plans are being made, for they ‘must away ere break of day’. Night falls and eventually the outlandish visitors – they are in fact dwarves – are put up in the spare bedrooms and on chairs and sofas. Ironically the hobbit oversleeps (his long lie-in is a running joke, for he often oversleeps), and his guests are gone. But they have left a formal note of thanks in which they set their meeting for 11am at the Green Dragon Inn, Bywater. Bilbo barely makes the appointment in time. Against his better judgement he has agreed to join the expedition, and to leave his comfortable situation far behind him.

Childhood memories and the setting of The Hobbit

The respectable village that forms the setting of The Hobbit goes way back to Tolkien’s childhood. For the first few years of his life after the family returned from South Africa, Tolkien lived in what was then part of Worcestershire, in the small country hamlet of Sarehole, at 5 Gracewell, the end house in a row of brick cottages, near what was at the time the village of Moseley, in other words close to, but far enough away from, the teeming industrial city of Birmingham. According to his biographer Humphrey Carpenter, Ronald Tolkien was ‘just at the age when his imagination was opening out’ on his arrival at Sarehole with his mother Mabel and his younger brother Hilary in 1896. In an interview given seventy years later in 1966, Tolkien was to describe his country home in this period as a ‘kind of paradise’, and with good reason. Robert Blackham’s The Roots of Tolkien’s Middle-earth provides in loving detail a nostalgic photo-gallery of this area of Warwickshire/Worcestershire and Birmingham at the time when the Tolkiens lived there.5 The period photographs conjure up this lost era: the architecture of the cottages, the water-mill, the old sand-and-gravel pit, the trees, the countryside and the people. A picture in the Tolkien Family Album of the main thoroughfare to Moseley village shows an unmetalled road, a hedgerow and field to the left, a fenced wheat-field to the right; in the distance the half-timbered houses of Gracewell peep through the trees.6

If one examines a colour painting The Hill: Hobbiton-across-the-Water that Tolkien made in 1937–8 for the first American edition of The Hobbit, the analogues and similarities immediately become apparent.7 The picture shows the Water (i.e. the name of the river), with the wooden bridge and the yellow road winding up to the Hill, into which the house Bag End has been built. On the left as a traveller crosses the bridge is a white-painted wooden signpost (marked WEST in one direction and HILL in the other), the sort of signpost that is still to be found in outlying English country districts, although most are now manufactured in painted steel. On the right-hand side of the bridge is the Mill, a three-storey building resembling a church tower and nave done in large yellow ashlar-stones and with a red-tiled roof. Behind the Mill is another road going from left to right lined on the riverside by a redbrick wall, presumably intended to keep people from straying down to the dangerous waterwheel and the mill-race. The dwelling house on the other side of the road is a large building, complete with a white-washed outhouse and a water-butt to collect rainwater from the roof. The garden is wooden-fenced on one side, with a hen hutch in the middle of the lawn and a worked plot for vegetables and cut flowers.

From the bridge the main road winds up through farmland to the Hill; it is a wide but unmarked yellow track, the same colour as the ploughed earth of many of the cultivated fields. On the left a wooden fence protects an orchard and a large prosperous-looking walled farmhouse with main house and outbuildings in the form of a quadrangle. Behind it are the stooks of the August hayfield, a green pasture bounded by a hedge; further back up the hillside are the round doors of some hobbit dwellings, the roundness of the doors being the only ‘alien’ feature in view, while in front of each house there is an unfenced strip of land for pasture and/or crops, a medieval or even Anglo-Saxon effect. Hobbits live in a world that resembles an idyllic version of England in about the year 1890; an ahistorical English countryside – one that never underwent the notorious enclosures of the early 1800s that so taxed rural workers and was captured in, say, the writings of the poet John Clare. It is an ordered, ‘respectable’ society with a municipal organisation (signposts), and some basic industrial production (baked tiles), but otherwise basically a pre-industrial modern world. In brief it is anachronistic, a vestige of rural England.

Tolkien uses the favourite trick of English language nomenclature: turning a concrete noun into a name simply by capitalising its initial letter. So in The Hobbit Bilbo lives on the Hill, and at the beginning of his journey he walks down the track past the great Mill to the river, the Water, then travels up the road alongside the Water to meet the dwarves at the Green Dragon Inn, at the village of Bywater (The Hobbit, chapter 2). At first as they travel they pass though ‘respectable’ hobbit country, with good roads and places to stay, and an occasional ‘dwarf or a farmer ambling by on business’. When Bilbo moves out of his familiar home country, however, the toponymy becomes unfamiliar and imprecise, all part of an otherwise unrecorded region of the Lone-lands (again capitalised as a name) in which no one lives, there are no inns and the roads are poor (The Hobbit, chapter 2). A respite is granted at Rivendell (chapter 3), with its sounds of running water rising from rock, the scent of trees, and ‘a light on the valley side across the water’ – here the phrase ‘the water’ could very easily have been capitalised to turn it into a place-name, though Tolkien resists the temptation. On their journey back, they at last return to ‘the country where Bilbo had been born and bred, where the shapes of the land and the trees were as well known to him as his hands and his toes’; eventually he sees ‘his own Hill’ in the distance, and ‘they crossed the bridge and passed the mill by the river and came right back to Bilbo’s own door’ (‘The Last Stage’, The Hobbit, chapter 19).

Sarehole was a threatened idyll, and it lasted only four years, for in 1900 the family moved to Birmingham. And Sarehole itself was anyway far too close to the city. In 1911 it was annexed to Warwickshire (it had originally been part of Worcestershire), and in the present day it has become part of the Hall Green suburb of Birmingham, in what is now, after the county reorganisation of 1974, the West Midlands. For Tolkien, however, Worcestershire was to remain the notional heartland. It was from the small town of Evesham in this county that his mother’s family the Suffields, had originated, and Tolkien felt closely the pull of family tradition and rooted-ness, even if most of the Suffields now lived in Birmingham. Throughout their childhood, the two boys had close contact with their relatives, particularly with their mother’s side of the family.

One character in particular is John Suffield (1833–1930), the Tolkien brothers’ sprightly maternal grandfather, who had managed his own prosperous drapery business in Birmingham until it had gone bankrupt; he then worked as a travelling salesman, and lived a highly active life to a ripe old age. He was a skilled draughtsman and calligrapher (his ancestors had been engravers), able to write the entire Lord’s Prayer in fine copperplate script on an area of paper the size of a sixpenny coin. Both his daughter Mabel and grandson Ronald inherited this calligraphic trait. His portrait in the Family Album (p. 14) shows an old man in a buttoned coat, with a long white beard, sharp nose and bright eyes. In John Suffield there is something of the Old Took, the adventurous patriarch referred to in the opening pages of The Hobbit, and ancestor of both Bilbo (on his mother’s side) and Frodo, a family legend among the adventurous Tooks, though the respectable Bagginses look on his exploits with suspicion. As Carpenter points up the similarities, there is on the one hand Bilbo Baggins, son of ‘the famous Belladonna Took, one of the three remarkable daughters of the Old Took, head of the hobbits who lived across The Water’ (The Hobbit, chapter 1), and on the other hand John Ronald Reuel Tolkien, ‘son of the enterprising Mabel Suffield, herself one of the three remarkable daughters of old John Suffield’.8

As for the name Bag End, this Tolkien owed to a house on an estate farmed by his enterprising aunt Jane Neave, his mother’s sister. Jane Suffield, a trained teacher, was one of the first women to study science,9 receiving her degree from Mason College (later the University of Birmingham). She was close to her sister Mabel and acted as a go-between passing messages from Mabel to Arthur Tolkien before her father John Suffield gave his permission for the marriage. Married in the early 1900s to Edwin Neave, Jane had the misfortune to be widowed in 1909, but she was able to recover her life, and her career followed various turns. In 1911 she was among several of the family, including Ronald Tolkien, who undertook an adventurous mountaineering holiday in the Swiss Alps organised by the Brookes-Smith family (see chapter 9). From 1912 to 1914 Jane Neave appears to have lived in Aberdeen working in a college, and it seems likely that Tolkien visited her there. By 1914 she was active as a market gardener with her nephew Hilary Tolkien, and based at Phoenix Farm at the village of Gedling near Nottingham. In the 1920s she lived on a farm that sported the unprepossessing name of ‘Bag End’, located at Dormston near Inkberrow in Worcestershire. It is here of course that Tolkien must have found the name for the Baggins property in his fiction. Like her nephew Hilary, who also became a fruit farmer, Jane ended up living back in the home territory of Evesham and its environs: staying in a caravan on Hilary’s land and then later moving to Wales to live with her cousin Frank Suffield. Ronald visited her on many occasions, particularly in his school and university years. He wrote his poem about the sea while visiting her at Aberdeen in 1912 (see chapter 8) and his important poem on Eärendel was composed at Phoenix Farm in 1914 (see chapter 13). In later life Jane Neave was instrumental in persuading her nephew to publish his poetry anthology The Adventures of Tom Bombadil; these poems appeared in 1962, shortly before her death in her ninety-second year. Evidently Jane was a sort of literary mentor or encourager to her nephew Ronald.10

It is fair to say that Tolkien re-created his late Victorian childhood paradise when he invented Bag End and Hobbiton. After he had published The Lord of the Rings (LOTR), he found it disconcerting that readers and reviewers assumed that Bilbo’s home in Hobbiton was somehow an analogue of the residential suburb in north Oxford in which he and his family then lived, a region of large Victorian houses built in the nineteenth century to accommodate Oxford dons and their families. In reaction to such opinions, Tolkien wrote in 1955 to his publisher Allen & Unwin that Hobbiton is essentially a Warwickshire village from the time of Queen Victoria’s Diamond Jubilee, nothing at all like the ‘characterless straggle’ of north Oxford, ‘which has not even a postal existence’.11 The latter fact (about postal existence) remains true to this very day, and although perceptions may well have changed as to the depressing character of north Oxford, the old medieval city two miles down the road is what captures the attention of the present-day visitor. It is indeed significant that Tolkien compared his then surroundings unfavourably with those of his early childhood.

Comic novels

When Tolkien became a story-teller for his own children, he turned first of all to humorous tales, especially animal fables: stories that had an animal as protagonist, or tales that featured talking animals among the main characters. These include The Father Christmas Letters, with one main character called Karhu or Polar Bear; Roverandom, the adventures of a dog; the early oral version of Farmer Giles of Ham, which also has the dog Garm as one of its main characters; The Adventures of Tom Bombadil, a story which, to judge by the poem of 1934, contained an episode with talking badgers. Against this background of animal stories told to children, we have The Hobbit, which, in terms of the way novels usually begin by setting a scene or getting the action moving, actually starts twice. The first page begins, rather like an animal story, with a creature in a hole, and then, a few paragraphs later, the story kick-starts again, this time rather more conventionally for a novel, with Gandalf ’s unexpected visit – indeed, the title of the first chapter is ‘An Unexpected Party’. The double-barrelled opening offers a number of interesting comparisons with stories that Tolkien had been reading at the time, either for his own pleasure or for the enjoyment of his children.

The first opening is the famous one already cited, found now in dictionaries of quotations, about the hole in the ground. There is a balance to the rhythm and phrasing of these two opening sentences, which certainly accounts for their appeal. There is also a rhetoric of expectation and contradiction. The hobbit may live in a hole but it is not a nasty, dirty wet one nor a dry, bare, sandy one but a hobbit hole, ‘and that means comfort’: the assertion helps to keep the attention of reader and, given the oral origins of this story, of listener. The choice of colloquial phrases suggests an audience of children accustomed to the language of story-telling: the fact, as the narrator goes on to declare, that the hole has a ‘perfectly round’ door with a ‘shiny yellow brass’ doorknob or that the entrance hall has ‘lots and lots of pegs’ for hats and coats because ‘the hobbit was fond of visitors’, the expressions here italicised being found more often in speech than in formal writing.

Since Tolkien certainly knew and admired Kenneth Grahame’s writings, a likely inspiration for the opening scene of The Hobbit is the first paragraph of Kenneth Grahame’s The Wind in the Willows:

The Mole had been working very hard all morning, spring-cleaning his little home. First with brooms, then with dusters; then on ladders and steps and chairs, with a brush and a pail of whitewash […] Spring was moving in the air above and in the earth below and around him, penetrating even his dark and lowly little house with its spirit of divine discontent and longing. It was small wonder, then, that he suddenly flung down his brush on the floor, said ‘Bother!’ and ‘O blow!’ and also ‘hang spring-cleaning!’ and bolted out of the house without even waiting to put on his coat.12

The industrious mole keeping a tidy burrow that resembles a late Victorian or Edwardian gentleman’s bachelor dwelling: all of this is highly reminiscent of the houseproud Mr Bilbo Baggins. And the mole’s exit in a hurry is not unlike Bilbo’s precipitous departure from Bag End without any money, or even a pocket handkerchief, ‘as fast as his furry feet could carry him’ down the Hill, past the Mill and along the river to Bywater. In both stories, there is the same tension between on the one side the settled home life and on the other the pull of adventure.

But Grahame’s animals are treated in part realistically. At the same time as being an anthropomorphised animal, the Mole is also really a mole, with certain characteristics – such as his scrabbling and scratching to dig his way up to the surface at the arrival of spring – that remind the reader of what moles really are like. Similarly, at first sight, the hobbit with his furry feet has been wrongly equated with a rabbit, not only by uncomprehending literary critics but even by characters in the story itself, such as the eagle who carries Bilbo to the Carrock, or one of the trolls, who wonders for a moment whether he has caught a rabbit when he apprehends Bilbo attempting to pick his pocket in the ‘Roast Mutton’ chapter of The Hobbit. In short, even though hobbits belong to the human genus, they nevertheless share some affinities with characters in animal stories and fables.

Fig. 1c No adventures

The word hobbit itself appears to be Tolkien’s invention.13 It is possible but unlikely that he saw the word in a nineteenth-century folklore treatise known as the Denham Tracts. This text gives a long list of natural and supernatural creatures; the relevant part gives the following pot pourri: ‘boggleboes, bogies, redmen, portunes, grants, hobbits, hobgoblins’.14 These diverse beings do not have much in common, except the element hob-in hobbit and hobgoblin. The Oxford English Dictionary (OED) distinguishes two basic meanings for hob. The first is a generic name for ‘a rustic or clown’, in which hob comes from Hob, a by-name for Rob, just as Hodge and Hick derive from Roger and Richard. It is to be expected of course that the first name Hob occurs in the Shire in LOTR (e.g. Hob Hayward the gatekeeper in book VI, chapter 8, ‘The Scouring of the Shire’). The second sense listed in the OED is ‘Robin Goodfellow or Puck; a hobgoblin, sprite, elf’, and the first citation for the history of the word is from the medieval Townley plays of about the year 1500; in its Middle English spelling it reads ‘Whi, who is that hob ouer the wall? We! who was that that piped so small?’ A hob is a mischievous sprite-like creature with pan-pipes, rather like Tinfang Warble in The Book of Lost Tales, or perhaps Tom Bombadil in LOTR; such beings will be discussed further below (chapters 5, 6, 16). The hob of folklore is not exactly a hobbit, but perhaps the germ of an idea was planted here in Tolkien’s mind.

At first sight rather surprisingly, Tolkien admitted a possible influence on The Hobbit from the contemporary American novelist Sinclair Lewis’s similarly leporine-sounding Babbitt, which was published in 1922 and sold well throughout the 1920s and beyond. As also happened later with the word hobbit, the word babbitt entered the language: both words are listed for instance in the Concise Oxford Dictionary. And as literary historian James M. Hutchisson shows, the word was used widely and creatively: Sinclair Lewis himself wrote in August 1921 of how he was ‘Babbitting away furiously’; the British sociologist C.E.M. Joad published a study of American society in 1926 entitled The Babbitt Warren; and the American writer H.L. Mencken popularised the term ‘Babbittry’.15 Tolkien himself echoed this in his use of the word ‘hobbitry’ when discussing critically, in his letters, whether the sections of LOTR focussing on hobbits and the Shire were unduly long and distracting from the main narrative of the War of the Ring.

Any surprise one might feel at Tolkien’s interest in Babbitt is legitimate, for the plot of the story was surely alien to his concerns. George F. Babbitt is a businessman living in the medium-sized American city of Zenith, where, as the ironically worded first sentence declares, ‘The towers of Zenith aspired above the morning mist: austere towers of steel and cement and limestone’.16 Nothing could seem more different to Tolkien’s opening scene. The surprise I think lies in the nature of the novel Babbitt, the epitome of the American ‘great realist novel’, intended as a satire on the conventionality of Midwestern urban society. The realist technique based on close sociological research is heavily laid on, with numerous personal and social details such as waking, washing and dressing in the opening sequence of the story. This is the kind of literature one might expect a former member of the TCBS – Tolkien’s rather purist literary set from his school days in Birmingham – to dislike and avoid. The TCBS, or ‘Tea Club, Barrovian Society’, was a kind of literary club, a circle of like-minded school friends, who met through the committee of the school library and organised illicit tea-parties inside the school library and at the tea shop in Barrow’s stores (hence the name Barrovian Society), where they read and discussed their literary work together.17 In some ways the TCBS prefigures the much more famous Inklings literary circle of which Tolkien was a key member while he was a professor of English philology at Oxford University.

Two folk-tale elements in Sinclair Lewis’s novel are used ironically in the initial setting of the scene, and they perhaps caught Tolkien’s attention. First, there is the mention of ‘giants’ in the description of the factory whistles heard across the city:

The whistles rolled out in greeting a chorus cheerful as the April dawn; the song of labor in a city built – it seemed – for giants.

The protagonist – who is pointedly called ‘unromantic’ – is an anti-hero, and Sinclair Lewis is at pains to emphasise that there is ‘nothing of the giant in the aspect of the man who was beginning to awaken on the sleeping-porch of a Dutch Colonial house in […] Floral Heights’. This novel is evidently a satire, a far cry from the preoccupation with the Anglo-Saxon eald enta geweorc (the ancient work of giants) in Tolkien’s writing. Second, there is the mention of a ‘fairy child’, but only in the context of a recurrent dream that comes to Babbitt every morning as he wakens to the rattle and bang of the morning milk-truck and the slam of the basement door:

He seemed prosperous, extremely married and unromantic; and altogether unromantic appeared this sleeping-porch, which looked on one sizable elm, two respectable grass-plots, a cement driveway, and a corrugated iron garage.Yet Babbitt was again dreaming of the fairy child, a dream more romantic than scarlet pagodas by a silver sea.

For years the fairy child had come to him. Where others saw but Georgie Babbitt, she discerned gallant youth. She waited for him, in the darkness beyond mysterious groves. When at last he could slip away from the crowded house he darted to her. His wife, his clamouring friends, sought to follow, but he escaped, the girl fleet beside him, and they crouched together on a shadowy hillside. She was so slim, so white, so eager!

There is of course very little that is reminiscent of Tolkien here, except perhaps the notion of escape, repeated a number of times on this page and the next, for essentially escape is the theme of Sinclair Lewis’s novel, a conventional man’s failed attempt to escape the trammels of his confined existence – the escape leads him from domesticity to an affair and from safe conservatism to a brief flirtation with radical socialism.

For Tolkien – as he terms it in his contemporary On Fairy-stories lecture – escape is one of the features of the fairy-story alongside recovery and consolation. And by escape he seems to mean a kind of protest against the mechanical and mechanistic straitjacket that modern society has imposed on itself in the name of progress. Here then is an instance of thematic affinities between Tolkien and a modern realist writer, despite the fact that their whole method and outlook are so very different. But even on the question of style some points of contact do exist, for both Tolkien and Sinclair Lewis are clearly comic writers. The following ironic passage on Bilbo Baggins’s conventionality brings this out well; if Baggins were changed to Babbitt and ‘The Hill’ to ‘Floral Heights’ the extract would fit quite well into Sinclair Lewis’s novel:

The Bagginses have lived in the neighbourhood of The Hill for time out of mind, and people considered them very respectable, not only because most of them were rich, but because they never had any adventures or did anything unexpected: you could tell what a Baggins would say on any question without the bother of asking him. This is a story of how a Baggins had an adventure, and found himself doing and saying things altogether unexpected.

In a very different social world, Babbitt also has his adventure, and the novel tells of his journey there and back again. By the end of the novel, Babbitt has at least acquired greater self-awareness, and he is unexpectedly liberal towards his son’s aspirations to make his own way in the world rather than follow family tradition and expectations. The sense of being larger and wiser after many experiences surely lies behind Bilbo’s loss of ‘reputation’ in the community after his return from abroad.

A similar theme runs through a children’s novel that the Tolkien household knew well and admired, E.A. Wyke-Smith’s The Marvellous Land of Snergs, with its main character Gorbo, ‘the gem of dunderheads’, who nevertheless ably helps his companions to survive their adventures.18 The consultant mining engineer Edward Augustus Wyke-Smith had begun composing fiction by telling stories to his grandchildren; he published his Marvellous Land of Snergs with copious illustrations by George Morrow in 1927. Tolkien was aware of it as a model for his own illustrated Hobbit, and he later described it to W.H. Auden as an unconscious source-book, which his children enjoyed hearing just as much as his own story about the hobbit.19 There are numerous similarities in the two plots and in certain minor themes and motifs: the Snergs are equivalent to the complacent hobbits since they are fond of feasting and rather set in their ways, while the escaped children Joe and Sylvia seem to have the resourcefulness of Tolkien’s dwarves, even down to their ability to mimic bird-calls.20 In some scenes, for example in the Forest Land, Wyke-Smith’s descriptive style recalls that of Tolkien:

In parts where the trees were not very thick the grass was all dappled with spots of sun, and sometimes there were great shafts of light through the trees to make a guide for them, for all they had to do so far was to go as fast as they could in the direction of the sun. (p. 29)

But it was getting dark; the sky was now hidden by a roof of matted leaves, and on all sides and above them the thick smooth branches twisted and crossed and locked together. (p. 50)

There is the same attention to the perils of the wild and the need for Gorbo, the foolish Snerg, to devise ways of evading the dangers; fortunately for Joe and Sylvia, he slowly becomes less gullible and less eager to please, more suspicious and more resourceful, and he rescues them from the supposedly friendly Golithos the ogre:

It will probably occur to the thoughtful reader at this point that a change had come over the character of Gorbo. A sense of responsibility, mingled with self-reproach, had brought forth qualities hitherto unsuspected… . (p. 84)

Above all it is the change in the Snerg’s character as the tale progresses that demonstrates the debt that Tolkien owed to this now little-known children’s story.

Finally, a similar pattern of departure and return informs the plot of a very popular children’s story, or set of stories, by the writer Hugh Lofting. The Hobbit-like plot of Hugh Lofting’s Doctor Dolittle (published in 1922) is summarised by its lengthy subtitle Being the History of his peculiar life at home, and astonishing adventures in foreign parts. It begins as follows:

Once upon a time, many years ago – when our grandfathers were little children – there was a doctor; and his name was Dolittle – John Dolittle, M.D. ‘M.D.’ means that he was a proper doctor and knew a whole lot.

He lived in a little town called Puddleby-on-the-Marsh.21

Puddleby is respectable, like Floral Heights or the Hill, and its citizens do not take kindly to eccentrics, such as a doctor who keeps animals in the drawing room that also serves as a waiting room for his patients; the comically eccentric Dolittle drives first his housekeeper away and then all his patients. According to John Rateliff, Lofting based his fictional town on his own native Berkshire, and imagined a setting in early Victorian England, rather like Tolkien’s locating of Hobbiton in the England of the Golden Jubilee.22 As to the place-name Puddleby, the element on-the-Marsh recalls the real place Morton-on-the-Marsh, whereas the -by suffix is Danish, and would belong better in the Danelaw of the east Midlands or Yorkshire. Apart from the obvious play on the idea of wet ground, there may be a further linguistic joke in the Puddle element, since various Dorsetshire villages with the place-name element Piddle were renamed Puddle in the nineteenth century on the occasion of Queen Victoria’s visit, just in case their unrespectable names proved offensive to her royal ears.

Unlike Tolkien in The Hobbit, Lofting eschews verbal description of setting or place. Instead, however, he illustrates the story with line drawings at regular intervals, and it is here that some further similarities can be discerned in the figures of Dolittle and Baggins. An illustration on p. 17 of the first edition ‘And she never came to see him any more’ pictures the moment when a patient walks out of Dolittle’s parlour, because of a hedgehog on the sofa, never to return. The small squat figure of Dolittle with his round paunch, top hat and dress coat is very hobbit-like; he is seen in profile on the left looking down the long sitting room at the retreating figure of the lady. A proud ancestral portrait on the wall adds to the effect, as do the low-slung chairs, and general air of respectability gone awry. It is tempting to speculate that Tolkien recalled the composition of the picture when he described the hobbit’s dwelling and drew his own illustration of The Hall at Bag End, Residence of B. Baggins Esquire – with its image of Bilbo in profile, the round coffee table and low chair, the fire-place and oak panelling and portraits – which appears in classic editions of The Hobbit.

Lofting has a plain simple style, peppered with didactic interpolations such as the above explanation of the initials M.D. The narrative moves at a great pace as the bumbling doctor first loses all his clients, then learns the language of the animals through the Helper figure of his pet parrot, and finally goes on a medical mission to rescue sick monkeys in Africa. He returns with a kind of treasure, a rare beast known as the pushmi-pullyu, with which he earns a great fortune at the circus, before retiring to his sleepy town once more:

And one fine day, when the hollyhocks were in full bloom, he came back to Puddleby a rich man, to live in the little house with the big garden. (p. 182)

Clearly this is another case of a story of there-and-back-again, and the emphasis on the language of animals that is associated with Dolittle is surely another influence on Tolkien, to which further reference will be made below.

‘By some curious chance one morning long ago in the quiet of the world’

The second beginning to The Hobbit actually reworks the opening formula, reintroduces the protagonist looking out of his doorway after breakfast, and at last sets the narrative in motion. In some ways this is a typical folk-tale start with its temporal adverbial ‘one morning long ago’, although the clause ‘when there was less noise and more green’ perhaps recalls the opening of Lofting’s Doctor Dolittle. But unlike ‘In a hole in the ground there lived a hobbit’, this is at the same time a more novelistic beginning: it sets the scene in a subordinate clause ‘when … Bilbo Baggins was standing at his door’ – which tells us in detail what the protagonist was doing – and then reveals the punchline in the delayed main clause ‘Gandalf came by’.

In jauntily familiar language with the exclamation ‘Gandalf!’ and with direct address to the child reader ‘if you had only heard…’, and colloquial vocabulary such as the verb sprouted up in ‘adventures sprouted up all over the place wherever he went’, Tolkien goes on to set a tone, constantly reminding his readers that this is a tale with an adult teller and a distinctive wit, speaking to an audience of listening children. The first conversation between Bilbo and Gandalf, a witty exchange on the pragmatic meaning of the social greeting ‘good morning’, is worthy of Lewis Carroll in Alice through the Looking Glass, and that children’s novel was certainly one of the ingredients that also went into the mix. The dialogue between Bilbo and his visitor follows on from the description of Gandalf with its many adjectives of size, quality and colour: ‘little old man’, ‘tall pointed blue hat’, ‘long grey cloak’.23 Interestingly this description echoes another, written by Tolkien broadly in the same period, concerning a ‘bad old man’, with a ‘ragged old coat’, ‘old pipe’, ‘old green hat’. It comes in fact from the story Roverandom, in which another wizard of more suspect nature than Gandalf comes prowling up the garden path and sets an adventure in motion.

Roverandom

Like the author Hugh Lofting, who wrote letters home to his children from the front during the First World War, and like Kenneth Grahame telling his stories of the adventurous Toad to his young son Alistair, then rewriting them later as The Wind in the Willows, Tolkien began his Roverandom – and a few years later also The Hobbit – as a tale told to his children. The plot of Roverandom is picaresque: the dog Rover, later renamed Roverandom, is lost on the beach and has various magical adventures on the moon and under the sea before he returns to his family. The occasion for telling the story was the need to console his sons for the loss of a toy dog, and to keep them calm during a storm. In August 1925, Tolkien and his wife Edith were celebrating his appointment as Rawlinson and Bosworth Professor of Anglo-Saxon at Oxford University; up to this point he had been a Reader at Leeds University since 1920 and a Professor since 1924. As his duties at Oxford did not begin until October, they left Leeds for a holiday at Filey on the Yorkshire coast with their three children John, aged nearly eight, Michael, nearly five, and Christopher, aged one (their daughter Priscilla was born in 1929). It was a typical seaside holiday, and they stayed in a cottage on the cliffs overlooking the sea.

On the night of Saturday 5 September 1927, however, there was a great storm on the coast: ‘the water heaved and shook and bent people’s houses and spoilt their repose for miles and miles around’;24 the abnormally high tide caused a lot of damage and Michael’s toy dog, which he had left on the beach, was now irretrievably lost. Two years later, on a holiday at Lyme Regis in Dorset (which he had visited as a boy), Tolkien seems to have retold the story and then written it up; he also drew three pictures related to it: House Where ‘Rover’ Began his Adventure as a Toy, a picture similar in many respects to his painting of Bag End in The Hobbit, and with an inscription to his son Michael; The White Dragon Pursues Roverandom & the Moondog inscribed to his son John, with some affinities to pictures of Smaug flying round the Lonely Mountain; and The Gardens of the Merking’s Palace, a unique and rather rich and exotic underwater seascape. He also at the same time painted some impressive illustrations to his ongoing mythology, including Halls of Manwë on the Mountains of the World above Faerie and Taur-na-Fúin, the tangled pine forest where Beleg first met Flindling the fugitive.25 A similar picture was used without the two elves as an illustration of Mirkwood in the first impression of The Hobbit, in 1937 (in chapter 8, ‘Flies and Spiders’).26

The published version of Roverandom retains the colloquial style and tone, beginning with the conventional ‘once upon a time there was a little dog, and his name was Rover’. Even more so than The Hobbit, there are frequent comments addressed to the young reader, such as ‘he would have known better’, that evaluate the events or, in this particular passage, anticipate what is about to take place:

He was very small, and very young, or he would have known better; and he was very happy playing in the garden in the sunshine with a yellow ball, or he would never have done what he did.27

In fact, the child reader has to persevere and even turn the page – to discover what it was that Rover actually did: namely to bite a patch out of the visiting wizard’s trousers, whereupon as punishment he is turned into a tiny toy dog, and later tidied away and put on sale as a second-hand toy in a shop window.

The plot progresses quickly, in sudden leaps and bounds, and there is a sense almost of the surreal, that anything can happen in this mingling of the mundane and the marvellous. For this kind of story (and the same could be asserted of his Father Christmas Letters) Tolkien borrows freely and happily from all sorts of sources and texts, including mythology (Celtic, Nordic and his own) and various classics of children’s literature. There is a freedom and playfulness in all the borrowing, despite the bizarre plot.

For example, Rover reaches the moon in his first adventure through the agency of another wizard, the sand-sorcerer, a strange obstreperous creature who sticks his ugly head out of the sand and castigates the dog for barking and disturbing his sleep (p. 13). The sand-sorcerer then declares his name to be Psamathos Psamathides, the head of all the Psamathists, and as he utters these names he pronounces every letter, including the plosive ‘p’, sending a cloud of sand through his nose that half-buries Rover the dog. Without scruples, Tolkien lifts the figure of Psamathos almost unchanged straight out of Edith Nesbit’s Five Children and It.28 Here the sand-fairy has eyes on stalks, bat-like ears, a spider’s tubby body covered in fur and monkey’s feet, and is scornful and angry at the ignorance of the five children who discover it:

‘You don’t know?’ it said. ‘Well, I knew the world had changed – but – well, really – do you mean to tell me seriously you don’t know a Psammead when you see one?’

‘A Sammyadd? That’s Greek to me.’

‘So it is to everyone,’ said the creature sharply. ‘Well, in plain English, then, a Sand-fairy. Don’t you know a Sand-Fairy when you see one?’

It looked so grieved and hurt that Jane hastened to say, ‘Of course I see you are, now. It’s quite plain now one comes to look at you.’

‘You came to look at me several sentences ago,’ it said crossly, beginning to curl up again in the sand.

Nesbit playfully presents a linguistically oriented creature who thinks in terms of sentences as units of time, and she makes language puns on the phrase ‘that’s Greek to me’ and the fact that the etymology of psammead is Greek psammos plus the suffix -ad, as in dryad; incidentally she also indicates the pronunciation of Psammead as ‘Sammyadd’ in Anthea’s bemused reply.29 In his borrowing of the figure, Tolkien the philologist takes the word derivation yet further with his suffixes -ides (son of) and -ist (expert), and he plays on the well-known prescription in the first edition of the OED that words beginning with ps-should be pronounced by academics with a clear ‘p’ consonant.30 Where Nesbit’s Psammead pronounces a modern and colloquial ‘s’, Tolkien’s Psamathos uses an old-fashioned, if not pedantic, ‘ps’. Of course there are no grotesques of this kind in The Hobbit, with the exception of Gollum, and even he, it turns out in the sequel, is a kind of degenerate hobbit.31

What, surprisingly, Roverandom and The Hobbit have in common is the same mythology and cosmology, for both are set in the world of Tolkien’s Book of Lost Tales and The Silmarillion, which he had begun in 1916–17, with an admixture of Norse or medieval lore and legend as an added extra. For example, the eccentric figure of the Man in the Moon in Roverandom has some affinities with the aged elf who stows away aboard the vessel of the Moon in Lost Tales, and also with the figure of fun in the poem ‘The Man in the Moon Came Down Too Soon’, which Tolkien published in A Northern Venture in 1923 and then again in The Adventures of Tom Bombadil in 1962.

When Roverandom rides to the moon on the back of the seagull Mew they fly over the edge of the flat world and there is a moment of cosmic vertigo for the little dog, and also for the involved reader, as they see the waterfalls cascading over the edge of the earth and down into the darkness of the abyss below. This is the cosmology of The Silmarillion, and arguably also of many medieval maps, which portray the world as a disc surrounded by the circle of the Great Ocean (although some scholars in medieval times were aware of the Antipodes and knew that the earth was a globe). At the end of Roverandom, the giant sea-serpent that encircles the earth in Norse myth makes a brief and dangerous if also comic appearance. The myths sit a little uneasily with a story set in a modern world, but the playful spirit of this surreal wonder-tale or children’s adventure mostly absorbs them quite easily.

The Norse element in The Hobbit

In earlier drafts of The Hobbit the connection with the modern world was more explicit: there was mention of the Gobi Desert, the Hindu Kush and Shetland ponies. The Norse influences remain many and various, but, unlike Roverandom, the world in which The Hobbit is set is a northern world situated in the past, where Norse elements fit much more easily. A well-known case of borrowing is the names of the dwarves who make up the expedition and who gather so unexpectedly at Bilbo’s house in the first chapter of the story. These come straight from the Voluspa in the Norse anthology of myth and poetry known as the Elder Edda.32 A similar list is to be seen in the Gylfaginning in the Prose Edda by the thirteenth-century Icelandic writer Snorri Sturluson, who writes, in Faulkes’s translation:

Thus it says in Voluspa:

Then went all the powers to their judgement seats, most holy gods, and deliberated upon this, that a troop of dwarfs should be created from bloody surf and from Blain’s bones. There man-forms many were made, dwarfs in the earth as Durin said.

And the names of these dwarfs, says the prophetess, are these:

Nyi, Nidri, Nordri, Sudri, Austri, Vestri, Akthiolf, Dvalin, Nar, Nain, Niping, Dain, Bifur, Bafur, Bombor, Nori, Ori, Onar, Oin, Modvitnir, Vig and Gandalf, Vindalf, Thorin, Fili, Kili, Fundin, Vali, Thror, Throin, Thekk, Lit, Vitr, Nyr, Nyrad, Rekk, Radsvinn.33

It will be apparent that Tolkien selected from this list a set of names for his dwarves in The Hobbit, incidentally changing the standard English plural dwarfs to dwarves for linguistic-aesthetic reasons.

Tolkien even tried to match dwarf name to character, as well as allowing his dwarves to travel in groups of related names. The first to knock at Bilbo’s door for the ‘Unexpected Party’ of chapter 1 are Dwalin and his older brother Balin of the white beard; then the two young dwarves Fili and Kili, also brothers; then Dori, Nori, Ori; then Oin and Gloin; while Bifur, Bofur and Bombur appear last of all along with Thorin, the important dwarf. The arrival at the trolls’ camp in chapter 2 is carried out in the same order of appearance; it is clear that Tolkien relishes the repetition and the roll-call of the names, and he expects his audience to enjoy the ritual too. Naturally, any brothers or other relatives have names that rhyme on their vowels or alliterate on their initial consonants. An added twist is that most of the names also have meanings: thus in Snorri’s Edda the name Nyi is New Moon, and Nordri, Sudri, Austri and Vestri in Snorri’s list signify north, south, east and west respectively. Tolkien perhaps chose names appropriate to character or looks: so Dvalin means Dawdler, Fili and Kili are Trunky and Creeky, while Bifur, Bofur and Bombur are translated by Ursula Dronke as the alliteratively connected names Trembler, Trumbler (a blend, perhaps, of ‘trembler’ and ‘tumbler’) and Tubby.34 Thorin of course is Darer, which certainly fits his rather risky venture. In Norse myth the dwarfs are children of the earth, and Tolkien followed suit: one of the dwarves in the story of Túrin is Mîm the fatherless, which indicates a similar origin (see chapter 4 for further discussion). However, Tolkien seems to change his conception of the dwarves over time, making them more personable, more human, and by the time he wrote The Hobbit they appear to be an amalgam of Norse myth and German fairy tale. In Sneewittchen (Snowwhite), for example, the dwarfs are miners who go out to work each day ‘hacking and digging out precious metal’ and return to their little house, in which ‘everything was tiny, but more dainty and neat than you can imagine’.35 The same kind of domesticity is seen in The Hobbit in the visiting dwarves’ demands for afternoon tea: some call for tea with seed-cake (if Bilbo has any), some demand ale, some porter (a dark beer popular in Victorian England), one requires coffee (an anachronism, of course, like the tea), while Gandalf and Thorin take a little red wine.

It is fair to say that the penchant in Roverandom for bizarre figures and surreal events is not transferred to the slightly later Hobbit, which is much more grounded in the coherent world of Tolkien’s mythology, with this added mix of Norse mythology and the Grimms’ Household Tales. And despite the word-play on hobbit–babbitt–rabbit that was discussed above, the protagonist of The Hobbit belongs to a race of people and is most definitely not a talking animal like the dog in Roverandom or in Farmer Giles of Ham.

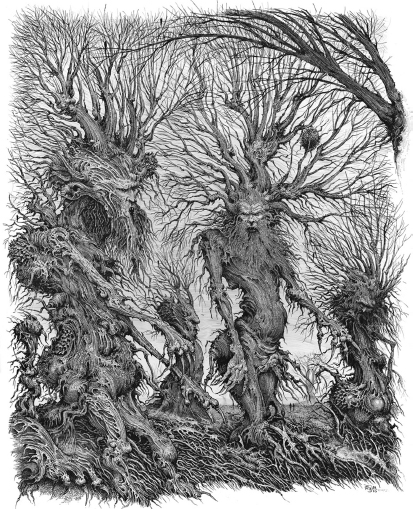

Fig. 1d Ents