CHAPTER 1

Parties–the roots of suspicion

The idea of party

The structure and role of parties depend not only on the type of political system or constitutional factors. The design of these organizations is also contingent on historical peculiarities and culture, including competing notions and ideas about the most appropriate manner in which to organize political action. A range of functionalist, organizational, and sociological typologies are possible, as Gunther & Diamond (2001) point out; typologies that, one might add, often neglect the relationship between ideology and party formation. The same authors also warn against the use of ‘excessively deductive’ models and ‘reductionist argumentation’ (2001: 6) when approaching the problem. (Duverger’s classic distinction between ‘cadre parties’ and ‘mass parties’ is presented as a case in point, since social class –i.e. the circumstance that cadre parties were often linked to the middle and upper strata of society, and mass parties to the working class–was reduced by Duverger to a purely organizational factor; ibid.) Indeed, any assessment of real-world parties confirms the immense difficulties involved in defining precisely what a ‘political party’ is, particularly in a nineteenth-century context.

In our case there was a striking contrast between the liberals and, most notably, the social democrats, both of whom originated as oppositional movements and as radical, anti-establishment alternatives. Eventually, though, only the social democrats clearly opted for a centralized, mass party solution for coping with the grass-roots level, whereas liberal parties during the same period fit better (but far from always) with Gunther & Diamond’s description (2001) of elite parties (see also Daalder 2001). True, originally liberal parties were often local and elitist both in composition and, in particular, leadership, but this was not always the case and conditions tended to change across time. Indeed, the notion of ‘elitist’ is often misleading if their membership structure by the end of the century is considered, not least in regard to Sweden (chapter 2).

The main argument of this book is that liberal parties made frequent use of non-party organizations in order to mobilize support (see later in this chapter). By this I refer to organization using a wide range of intermediate, voluntary organizations typical to nineteenth-century civil society. This strategy resembled the rationale of mass parties more than the pattern characteristic of elite parties, except for one important difference. Liberal support organizations were ‘proxies’ rather than ‘secondary organizations’ proper, since they were not normally affiliated with the party organization in any formal sense. They often emerged before the actual formation of parties themselves, and they operated as independent bodies with agendas and goals that were usually ‘non-political’. In certain respects, though, their interests would, from time to time, converge with those of the liberals. In part as a consequence of this organizational structure, liberal parties also lacked another feature typical of mass parties; more specifically, highly formalized and centralized bureaucratic structures. Arguably, this pattern holds for both Sweden and Germany during the period. Gradually more inclusive rules for political participation, or variations in external pressure, viz. the often noted circumstance that the German social democrats faced harsher conditions than their Swedish comrades, in particular under Bismarck’s Anti-Socialist Laws, 1878–90, does not provide sufficient explanation for the difference between liberal and socialist political association.1

For the above reasons, then, the principal functions performed by parties and not typologies are a more suitable point of departure for studying liberal organizational behaviour. These functions include (1) nomination of candidates, and (2) electoral mobilization, presumably by force of (3) interest aggregation and (4) issue structuring, on the basis of which a party might eventually (5) form and sustain a government (Gunther & Diamond 2001). Usually these functions are grounded, albeit however loosely, in some kind of ideological concern or political programme, such as in the case of liberal and socialist parties. As result, parties also serve the purpose of (6) societal representation and (7) social integration (Gunther & Diamond 2001). Not all of these criteria are necessarily always met by every party, and least not during the formative phases of party systems. In addition, political practice and emerging modes of organization did differ between different regions, as I have pointed out. For instance, Offerman’s analysis (1988) of the left-liberal movements in Cologne and Berlin in the 1860s reveals an interesting variation between the cities with respect to the attitudes towards mass organization as well as parliamentarianism as a principle.

Bearing this in mind, not only electoral mobilization but particularly functions such as societal representation and integration become extremely important from the point of view of democratization. It may not always be self-evident to the individuals themselves, but by nominating candidates for office and by mobilizing voters with the aim of forming a government, parties ‘enable citizens to participate effectively in the political process and, if successful in that task, to feel that they have a vested interest in its perpetuation’ (Gunther & Diamond 2001: 8). Parties thereby become a mediating arena in which the democratic system has the opportunity to consolidate itself and, among the array of competing practices typical to modernizing political systems, become instituted as ‘the only game in town’, to follow Linz & Stepan (1996: 5). Still, the demise of the Weimar Republic and the subsequent path taken by Germany illustrates how difficult the long-term outcomes of this process are to predict (cf. Suval 1985).

Although parties were eventually accepted in democratizing societies, accepting is not necessarily the same as embracing them. The political party was more often met with suspicion until well into the twentieth century. Criticism of the ‘political morale’ of parties was voiced regardless of national setting and ideological orientation. It could, as in my introductory example from the Swedish 1911 general election emanate from a formerly conservative minister of justice, concerned by the lack of ‘fair play’ in the political game.2 It could also be voiced by local liberals, such as Emil Rylander from northern Värmland, when running, somewhat hesitantly, for a seat in the 1917 election; in his case concern was raised in regard to the tension between personal conviction and practical necessity implied by formal affiliation to the party.3 And it could, indeed, be articulated with respect to the growing bureaucracy and alledged democratic deficit of organized socialism, as in Robert Michels’ famous (1911) account of the German Social Democratic Party (‘Sozialdemokratische Partei Deutschlands’, SPD).

Examples such as these are in no sense unique in the history of democracy, since a political system in transition and its key actors may, at least theoretically, choose between any number of organizational strategies to manage mass politics. The mere variety of functions performed by parties suggests that the formation of ‘typical’ mass parties was but one of several hypothetical solutions. Obviously, too, the problem of party system formation involves the issue of gradual change and adjustment versus institutional incentives. Importantly, however, whatever the merits of ‘sequentialist’ and ‘non-sequentialist’ arguments alike, they do not wholly explain the transition from traditional, community based forms of association and elite parties, and the channelling of social action into new types of organizations, such as the modern political party. For example, the coming together of a fully-fledged, clearly left-right orientated, mass party system was closely related to the franchise in Sweden. In Germany the reform of the election laws in the late 1860s did not achieve the same effects on a systemic level. A different analytical approach is therefore called for.

Ultimately, the problem of how the modern political party emerged is one of social cooperation, and a problem which involved ideological considerations from those involved, as well as practical, organizational tasks. To begin with, it is easy to demonstrate a long tradition of philosophical arguments raised against the very idea of party; arguments the pros and cons of which filtered down into the political ideologies of conservatives, liberals, and socialists alike around Europe. A few examples will suffice in order to illustrate my point. David Hume, for instance, the great Enlightenment advocate of voluntary cooperation, voiced considerable suspicion towards political parties in his famous essays. According to Hume’s view, parties–or ‘factions’, as he knew them–‘subvert government, render laws impotent, and beget the fiercest animosities among men of the same nation, who ought to give assistance and protection to each other’ (Hume 1904 [1741–42]: 55).4

Similar arguments, although framed by different historical considerations to those of Hume, were, as indicated, also widespread in nineteenth-century Sweden and Germany. For one thing, the very meaning of ‘party’ as well as the implications of ‘membership’ remained uncertain. Partisanship and factionalism were abhorred, although the latter often arose precisely because of the lack of organizational stability and transparency. In relation to the German states, it has been noted how early liberals–in this particular case Hamburg liberals in the late 1840s–held a sceptical view of party and the formal organization of political interests. Following Breuilly, parties were considered ‘sectional’ and ‘divisive’ (Breuilly 1994: 223). Likewise, fear of factional strife, real or imagined, was to haunt the Schleswig-Holstein liberals, too, from the very first all-German elections in 1871 onwards.5

Considerations such as these necessitate, as a first step of my analysis, a focus on arguments on the idea of party from a historical, ideological, and institutional (particularly constitutional) perspective. Doing so involves dissecting the contradictory but nevertheless close relationship that has, historically speaking, existed between the idea of party and the problem of social cooperation, including the rise of new modes of civic association from the Enlightenment onwards. One relevant topic of debate from that perspective was, of course, Adam Ferguson’s 1767 essay on ‘civil society’: could political parties actually be considered a part of civil society in the new, post-1789 political landscape? Or did parties belong to another realm?

Clearly, for instance, notions such as ‘civil society’ and ‘party’ implied one kind of political rationality in British usage, but evoked another frame of mind in regard to voluntary association and, importantly, citizenship in the Swedish or German context. For instance, as Jürgen Kocka (2005: 36) has pointed out, the positive connotations of ‘civil society’ lasted longer in Britain and France compared with the German states, where the ‘semantic change from “Zivilgesellschaft” or “Bürgergesellschaft” to “Bürgerliche Gesellschaft”’ implied a ‘basic devaluation of the concept’, following Hegel’s and Marx’ inclusion of the market in it.6 Consequently, establishing a fundamental difference between organizations in a historical perspective in terms of ‘civil’, or ‘civic association’, and ‘political association’ respectively is a notoriously difficult and most likely impossible task. I will use the terms ‘civic’ and ‘political association’ and consider them, in principle, as subsets of ‘civil society’ when voluntary association is referred to more commonly in the following, but it is possible to address the problem in more detail only in connection to specific cases.7 Although sharing certain philosophical and ideological traits rooted in a more common, European intellectual tradition, Sweden and Germany illustrate ample variation in the manner of how the ‘idea of party’ was eventually managed. Clarifying the logic of this problem also includes providing the historical background and rationale of my comparison of Värmland and Schleswig-Holstein. This comparison constitutes the link between my concern for political modernization and the second step of my inquiry, viz. patterns of liberal organizational practice and behaviour at the regional level.

Interestingly, it would seem that it was liberals, rather than conservatives or socialists, who had most difficulties in adapting to the idea of party. At this point we confront something of a paradox. The evolution of political parties was an integral part of democratization, although parties were simultaneously met with suspicion. Yet, even if attitudes among nineteenth-century liberals capture this ambiguity very nicely, it should also be noted that among the major ideological camps of the time, liberals were also among the earliest to attempt nationwide organization and national election campaigns. This was the case in Sweden, where radical liberals in Stockholm–in vain it should be added–rallied for all-out mobilization as early (relatively speaking) as the 1869 general elections (Esaiasson 1990:70–71). Also in Germany organizational issues emerged as a main problem among the liberals when the 1848–49 Frankfurt Parliament assembled. Later on, the liberal leadership in both countries did not, despite the resistance put up against the idea of centralized parties, lack strong proponents of formal organization along strict lines. These included (in Sweden) Karl Staaff,8 prime minister in 1905 and 1911–14, and (in Germany) parliamentarians in the 1870s such as Max von Forckenbeck or Franz Schenk von Stauffenberg, to mention only a few (Sheehan 1978: 128–29).

These circumstances capture something of the essence of the controversies surrounding ‘the idea of party’. For instance, as late as the early 1930s, and following a decade of severe factionalizing among the Swedish liberals over whether or not to support the prohibition of alcohol, local representatives in Värmland still spoke in favour of creating as loosely a knit organizational framework as possible, when the prospect of a reunited party eventually opened up.9 Although it may have been wise to favour a cautious strategy, given the delicate task of reuniting a party split right down to the core, opinions such as these were also due to the historical underpinnings of liberalism. Somewhat oversimplified, early conservatives could lean back on the corporatist traditions of pre-revolutionary Europe. And although conservative elite parties later proved that they were not alien to the idea of indirect action via various proxy organizations if the situation called for it, they lacked the ideological arguments for institutionalizing this as a standard. As for the socialists, they were, by force of Marxist ideology, in a sense naturally ‘predestined’, or inclined to move, eventually, towards collective agency on a massscale. (At least that would seem to be the case with reformist, social democratic parties. Most notably, the manner in which the Russian Bolsheviks decided to organize did, of course, represent a different solution, also in part because of doctrine.) The options facing nineteenth-century liberalism were equally complicated. Liberalism in the nineteenth century was certainly complex in nature and outlook, and reveals great variation once we start to compare countries. Nevertheless, on a general level, the ‘creed of individualism’ inherent in liberalism (Smith 1988: 20) is, together with its Enlightenment extensions, most likely one of the main reasons why liberal parties in many countries share a tradition of weak organization.

By way of conclusion I will concentrate on two tasks in the remainder of this chapter. Firstly, in searching for an explanation for liberal organizational behaviour it is, for reasons already indicated, necessary to embark upon a more elaborate discussion of the theoretical relationship between the ‘idea of party’ as a problem of social cooperation and the ideological tenets of liberalism. Secondly, I will outline my research design in more detail, most notably with respect to my comparative approach to organizational practice, and the choice of Värmland and Schleswig-Holstein as regions suitable for comparison.

The rest of this book is divided into four main chapters. Chapter 2 provides an analysis of contemporary ideas on the nature and use of political parties in a historical, ideological, and institutional context. The issue of citizenship became of critical importance from that perspective. My focus will be Sweden/Värmland and Germany/ Schleswig-Holstein during the period following the French Revolution. Regional specificities vis à vis the respective national frameworks will be dealt with. In this chapter I will also posit early examples of organizational behaviour in relation to the formation of modern liberalism. I will forward the hypothesis that mobilization of public support and voters, i.e. high levels of liberal voting turnout during the 1860–1920 period (tasks which loosely organized factions and elite parties were, indeed, ill-fit to manage), was contingent on political association by means of proxy. At the same time, though, the risk of faction among the liberals also increased, since this kind of organizational structure made it more difficult, for instance, to execute issue structuring and interest aggregation in a coherent manner. A case in point is the close relationship between Swedish liberalism and organized temperance, the latter movement providing important, organizational support to the liberals. Yet, as previously noted, the rise of teetotalism and controversies about prohibition also resulted in factional strife and, finally, contributed to the split of the party. Based on ideas of citizenship that originated in the civil society discourse of post-1789 Europe, the strategy of mobilizing by means of proxy was therefore flawed, since it made the organizational behaviour path dependent in a manner which hampered the formation of tightly-knit mass party structures. As the ‘social issues’ represented by bourgeois civil society became more and more politicized, and as the competition over mass support with other political movements, such as most notably the social democrats, grew fiercer, liberal parties became marginalized.

In chapters 3 and 4, I will analyse how the tension between ideology and mass politics was managed when liberals actually went ahead with the task of political association in Värmland and Schleswig-Holstein. Particular attention will be paid to electioneering in the two regions, for analytical as well as practical reasons. The nomination of candidates and electoral mobilization are among the two most important tasks for political organizations competing for office, and early liberal factions and parties were mostly quite inactive during the periods between general elections. Also, it is during election campaigns that we perhaps are most easily able to approach the important issue of how parties managed ‘societal representation’ and ‘social integration’, viz. a critical aspect of grass-roots democratization. This feature, therefore, also brings forward the problem of liberal ideology in relation to socioeconomic and cultural factors in the local environment.

Some further clarification, though, is still required. As I pointed out in the introduction, organizational efficacy presumably has effects on electoral mobilization. Firstly, however, the outcomes of elections may also produce effects on organization. Secondly, rather than juxtaposing ‘ideology’ and ‘organization’ in search of explanations for this relationship, these two factors should be considered together in the life of real-world parties. The analysis in chapter 3 and 4 will address organizational behaviour in three related dimensions (cf. Panebianco 1988: 239–61, in particular 243–47). More specifically these dimensions include a focus on various (1) external challenges (including, most notably, electoral defeat) which, in turn, may provoke changes in the (2) internal conditions of parties, including the rise of competing factions and, eventually, changes in the composition of leadership. Such changes may result (3) in adjustments in organizational structure, such as mergers of factions or attempts to centralize organization.

In the same way as the functions identified by Gunther & Diamond (2001) are applicable to the study of party organization at regional as well as state level, so the above-mentioned dimensions apply to the former level as well, particularly with respect to the initial stages of party systems formation. Again: one important feature of party systems formation in nineteenth- and early twentieth-century Europe was precisely the integration of regional political interests on the national level (Lipset & Rokkan 1967). Organization of centralized parties and concerted aggregation of interests were–in both Sweden and Germany–to a great extent a matter of competition between regionally entrenched factions, each one with their specific social base, make-up, and outlook. Also, changes in local leadership and, in effect, organizational structure, had implications for electoral mobilization strategies on the regional level even within the framework of centrally adopted structures. This was indeed the case in Schleswig-Holstein, where highly autonomous party structures became typical for the region after 1871 (chapters 2 and 4). Importantly, too, all of these dimensions involved discussions that ranged beyond those of purely organizational problems. In fact they involved and were sometimes ultimately embedded in ideological conflict, reflecting the historical and socioeconomic peculiarities of the region. Competition between various factions over programme issues therefore illustrates the complex relationship between ideology and organization. Not only a smart organization but also ideology as filtered by organizational structures does, indeed, help bring voters to the ballot box.

In chapter 3, the framework of my narrative will be the development of Swedish liberalism from the introduction of a modern, bicameral parliament in 1866 up to the introduction of universal suffrage in 1921. An epilogue necessary to include in this case, though, is a concluding assessment of the liberal movement given its split on the issue of prohibition in 1922–23, and the reappearance of a unified party in 1934. In chapter 4, I will likewise follow liberalism in Schleswig-Holstein, from the incorporation of the region as a province of royal Prussia in 1867, via the formation of a unified Germany, and up to the 1912 elections. Analogous to the Swedish case, certain concluding remarks which extend beyond the First World War are necessary. These include the introduction and demise of the Weimar Republic, and the sharp turn of the regional electorate in favour of, first, right-wing parties and, later, the Nazis. Chapter 5, finally, is a comparative assessment of my two regions. Here I will relate my hypothesis on liberal organizational strategies to the paths taken by Swedish and German liberalism in a longer perspective.

Political association as social cooperation

It was in late eighteenth-century America that the world’s first modern party system began to evolve. Consequently, it is also to that context we owe one of the first, more complex considerations as to the nature of parties. It is a well-known fact that the founding fathers of the Republic, men like Benjamin Franklin, Alexander Hamilton, and Thomas Jefferson, were hesitant about the matter of parties. Parties were ultimately something negative, but–alas–also a necessary evil in public life (Goodman 1967; Aldrich 1995). Somewhat less negative views were put into print a few decades later (1835–40), by Alexis de Tocqueville, in his reflections on American society and politics. Tocqueville identified a close and mutual relationship between civic and political association, although at the same time he also separated them, somehow making them both part of civil society and yet not: ‘Civil associations … facilitate political association; but, on the other hand, political association singularly strengthens and improves associations for civil purposes’ (Tocqueville 2003 [1840]: 12; see also Putnam 2000). Whereas Tocqueville did warn against ‘unstrained liberty of political association’ (2003 [1840]: 16) because of the perils of self-interest, his views on the topic were still less emphatically put than those of David Hume a century earlier.

There were perfectly good reasons for this difference. The US political system was far more inclusive than was the case in either Britain or any other European state at the time of Hume. ‘Politics’ for Hume primarily involved matters of state (cf. Viroli 1992). By force of tradition politics were at the same time overtly elitist, corrupted by self-interest, and not a concern of voluntary association. In contrast, Americans faced the practical problems and needs involved in political association and coordination of mass politics earlier, and in a different manner to Europe. Considering this difference in historical background, Schattschneider’s dictum (1942: 1), that ‘democracy is unthinkable save in terms of parties’, or Aldrich’s paraphrase (1995: 3) that ‘democracy is unworkable save in terms of parties’, are not surprising from an American point of view. In Europe, however, the relationship between democratization and parties turned out to be more confusing. Put simply, the ‘sequence’ by which mass politics, party systems, and democratic institutions fell into place differed and was, in important respects, reversed compared to the US. At this point, though, the problem also becomes more complicated to assess.

Contemporary liberals in Sweden and Germany liked to stress that the defining quality of the movement which they were spearheading was that is was–more than anything else–an ‘ideological community’, or ‘Bewegung’, brought about by individuals, rather than a strictly formalized organization. It is this property of liberalism that comes to the fore if, for example, we consider early, urban middle-class radicalism in Sweden. The very same feature is also present in the German context, if we try to gauge the importance contemporary liberals attached to the large but diverse middle class, or the ‘Mittelstand’, including the role of the ‘Bildungsbürgertum’ as a steward of the Enlightenment notion of a modern, public sphere (Langewiesche 2000 [1988]; Gross 2004). Although these ideas proved to be unrealistic, not least in regard to the possibilities of managing interest aggregation, social representation, and integration, they became a lasting legacy of liberal thinking. Examples of this are, firstly, Rönblom’s work (1929) in part scholarly account, in part political statement on the Swedish Liberal Party around 1900: in his view the party was a broad coalition of ideas and, precisely because of this, a party with far-reaching extensions that brought social classes together rather than pitting them against each other (1929: 96–97). The other example is the German national liberal Eduard Lasker’s description in 1876 of his movement as a ‘great political community’, filled with ‘a variety of opinions’, but still characterized by ‘great unity’ (quoted in Sheehan 1978: 128).

Such a broader understanding of liberalism is at the same time not without merit from an analytical point of view. Ambiguous as liberalism certainly was, this still was a trait typical to all great ideologies of the nineteenth century. Liberalism, socialism, and conservatism alike must be considered as a set of tentatively formulated responses to the no less amorphous problem of modernity itself, just as much as mere divided opinions on the concrete, day-to-day issues of government. The major issues at stake involved nothing less than transforming more widely dispersed ideas and beliefs on the nature of man and society into doctrines that could be used for moulding the social and cultural fabric of modern life. This kind of sociological perspective on liberalism has also been applied to more recent analyses of German liberalism (Gross 2004: 22–23). Yet, all this does not of course imply that nineteenth-century liberalism lacked distinguishable features. In the search for defining elements, it could be argued that precisely the problem of self-interest and–in crucial respects yet another Enlightenment legacy–that of individualism, economic and political, formed the core of emerging liberalism.

On the one hand, all of the critical issues of liberalism, such as the call for ‘freedom for economic enterprise’, for ‘constitutional reform’, for ‘enlargement and the protection of civil liberties’, as well as its anti-clericalism, were ultimately related to the ‘creed of individualism’ (Smith 1988: 17–20). This celebration of individual achievement and action was congruent with the kind of small-scale, local level civic association that became typical to both Swedish and German liberalism during the first decades of the nineteenth century. At the same time, though, the visceral relationship between liberal ideology and community, and the difficulties involved in coordinating what were only loosely integrated organizational networks, simultaneously guaranteed that any of the above-mentioned issues became subject to a range of different and competing interpretations whenever ideas were put to the test in real life. This feature, too, is vividly illustrated by liberalism, and not least in Germany during the ‘Vormärz’. In short, it became characteristic of many nineteenth-century liberals that one and the same person could take different, and occasionally ‘illiberal’ or outright conservative positions on related issues, thus acting in a manner signalling a lack of any coherent ideological conviction at all. In the words of Galston (2003 [1989]: 123), liberal individualism emerged from a ‘divided’ conception of the self, in the sense that ‘individuality is not only shaped but also threatened by the community’. Then, again, the exact nature and limits of community were also unclear. Liberalism could signal one set of more or less specific attitudes in urban, industrial environments, and yet another in rural regions, with a different economic and social make-up, such as Värmland, or Schleswig-Holstein (chapters 3–4). Therefore, if the tension between competing ideas, and between ideas and ‘political necessity’, or ‘realpolitik’, explains a lot of these contradictions, the nature of the conflict would always differ depending on the actual situation and context.

Individualism and the call for liberty would automatically seem to imply a certain, sometimes considerable, amount of criticism and mistrust regarding the state and its power, but this was not always the case, neither in Sweden nor in Germany. For instance, once the notion of economic individualism had made inroads in Swedish parliamentary debate, liberal attitudes towards state intervention in certain sectors of the economy proved surprisingly pragmatic in the long run. A fitting illustration of the latter is how the issue of railway construction was managed in the 1850s, i.e. a large, costly, and strategically important project in which state-ownership proved necessary (Oredsson 1969; Ohlsson 1994). Another example pertains to political individualism and state–citizen relations in Germany. In this case we should consider the alliance struck between the right-wing liberals (from 1867 formalized as the National Liberal Party), and the Prussian state during the second half of the 1860s. Following the failed 1848 reform movement and, later, the outcome of the Prusso-Austrian war in 1866, the Prussian liberals were driven closer to Bismarck’s programme of creating a unified Germany by ‘revolution from above’. As Sheehan put it, ‘Bismarck, the man whom they had vilified as a hopeless reactionary, suddenly emerged as one of Europe’s most creative statesmen’ (Sheehan 1978: 123). Whereas this turn for all practical purposes meant that the idea of building a nation-state solely on the basis of grass-roots activism finally had to be abandoned, it was nevertheless accepted and even embraced by many liberals, including in Schleswig-Holstein, where autonomist sentiments otherwise remained strong (chapter 2).10

The issue of nationhood at the same time points to an obvious difference between Swedish and German liberalism; a difference which was to produce effects on both ideology and political practice in the latter case. Put simply, unlike the case in Sweden, liberals in the German states faced a situation in which they were forced to manage somehow both the ‘classic’ liberal dilemmas of civic liberty and constitutional reform as well as the overwhelming problem of how to create a unified nation. Failing to accomplish this task by mobilization from below, and with the middle classes in the vanguard of the only viable option left to many liberals was alignment with the state and the traditional Prussian elite. Also, another typical trait of German liberalism was the nature of anti-clericalism and anti-Catholicism, something which in effect opened the way for yet another area of close cooperation with the emerging state apparatus of the Second Empire (Gross 2004). Tensions such as these signalled a degradation of democratic conceptions of citizenship. Indeed, this is reflected in the remark made by the famous liberal constitutional lawyer Hugo Preuss, during the First World War that the German people had led their history in a ‘serene state of political innocence’ (Preuss 1916: 7–8).11

Such apparent differences notwithstanding, however, one feature which Swedish and German liberalism undoubtedly had in common was the problem of self-interest and individualism, whether economic or political, in relation to certain formalized expressions of community, i.e. party. Indeed, ‘individualism’, ‘community’ or, to mention yet another critical concept, ‘freedom’, are abstract categories. In that sense there were no simple solutions to resolve the tension between individualism and collective agency, whether in the shape of the ‘state’, the ‘nation’, or–as in our case–in the guise of political parties. Managing individualism in relation to society, to be sure, is a major concern of all major political ideologies. The problem of liberalism, at least from an organizational point of view, was that individualistic beliefs formed the core element, ideologically speaking, of the movement in addition to being a social issue potentially subject to political management.

What, then, constitutes a plausible theoretical point of departure for analyzing liberal organizational behaviour? To begin with, we must scrutinize the relationship between the two types of association identified by Tocqueville, namely political association and civic association. As I have suggested, it is in the manner of how these problems were approached in contemporary society that we find clues to both the ideological as well as the practical dimension of the ‘idea of party’. In essence I argue that political association, including parties, is subject to the same basic logic and faces the same basic challenges as most other types of social cooperation. Yet, as indicated, Tocqueville and many other thinkers of the time drew a not always clear but nevertheless distinguishable line of demarcation between voluntary social cooperation, including civic association, and political association. Somehow these expressions of human endeavour seemed to represent distinct modes of agency. Let us again consider David Hume.

From one point of view, the emergence of political parties embodied one of the many possible solutions to Hume’s problem of social cooperation. Viewed from a slightly different perspective, however, it was precisely the tension between (political) interests, or self-interest, and cooperation that made the picture complicated. Hume was very specific about the limits of self-interest:

When every individual person labours a-part, and only for himself, his force is too small to execute any considerable work; his labour being employ’d in supplying all his different necessities, he never attains a perfection in any particular art; and as his force and success are not at all times equal, the least failure in either of these particulars must be attended with inevitable ruin and misery. Society provides a remedy for these three inconveniences: by the partition of employment, our ability encreases: and by mutual succour we are less expos’d to fortune and accidents. ’Tis by this additional force, ability, and security, that society becomes advantageous (Hume 1960 [1739–40]: 485).

It is easy to see how formal organization in terms of party, according to this view, promotes the kind of collective ‘force’ and ‘ability’ that facilitate, for instance, interest aggregation and electoral mobilization. Importantly, too, Hume also identified a close relationship between, on the one hand, social practice and, on the other hand, laws, rules, and customs or, in one word, institutions (Hume 1960 [1739–40]: 492). Only under the protection of the rule of law would social cooperation thrive.

Underpinning the notion of social cooperation was the assumption that it provided a remedy for the ills of excessive self-interest; as was Ferguson’s notion of a civil society (Kettler 1977). Yet, considering that political parties in Europe traditionally emerged on the basis of competition between various parliamentary factions, and were often closely associated with the ambitions of established regional elites and individual wielders of power, it was hardly surprising that Hume and his contemporaries held the idea of party in low esteem. This is reflected in Aldrich’s statement that political parties were ultimately the creation of ‘the politicians, the ambitious office seeker and officeholder’. Thus party became a means of obtaining a multitude of goals, ranging simply from the ‘desire to have a long and successful career in political office’, to the ambition of achieving various policy ends (Aldrich 1995: 4). All differences between the US and Europe set aside, this pattern illustrates what seems to have been a more or less general rule by the turn of the nineteenth century. Two factors, however, changed the working conditions of politics and simultaneously spelled the demise of traditional elite parties. One circumstance was the emergence of modern political ideologies and critical reflection on the concept of citizenship, following the French Revolution, whereas the other factor was the gradual rise of mass politics.

In brief, the first circumstance provided political parties with incentive and motives beyond those of mere self-interest, while the other provided the necessary external pressure needed to provoke experiments with new modes of organizational behaviour. Hence, the future would have seemed secure for the establishment of the political party as an appropriate solution to the social and political problems posed by a new era. A critical factor both from the point of view of principle as well as organization, however, was ideology. To begin with, voluntary cooperation as understood by Hume and, indeed, in more recent times most notably by Ostrom (1990), rests on what could best be labelled economic calculations of the likely net profit to be gained from cooperation. This is the essence of the prisoner’s dilemma game and other game theory models: if, among other things, mechanisms securing commitment, monitoring, and accountability, are properly institutionalised (Ostrom 1990: 185–86), we arrive at the kind of conditions where social cooperation based on mutual trust becomes possible, and where the individual actor is provided with the ‘additional force, ability, and security’ needed for prosperity (Hume 1960 [1739–40]: 485).

Mechanisms to harness excessive self-interest, then, are possible –even among citizens within the framework of a political party. Obviously such arrangements, or rules of the game, may be a direct property of organizational structures, analogous to Panebianco’s model of parties (1988). But if we take ‘trust’ to be the operative word, there are also other ways of restraining self-interest. Let us only consider the role played by parties in terms of societal representation and social integration. Representation and integration do not only require proper organization and leadership; they also imply shared beliefs and convictions. Ideology, therefore, may under certain conditions serve as a strong incentive for the creation of mutual trust and social cooperation (but it may, of course, also function as a source of conflict).

Therefore, whereas I do concur with Aldrich that elites and ambitious politicians (i.e. to some extent self-interest) had a lot to do with the creation of political parties, ideology must also be made part of the picture. Similarly, it is possible to argue that commitment to political ideologies–liberalism, socialism, conservatism, etc.–is, at least in part, about calculating possible future dividends in a way roughly similar to game theory. Yet, precisely at this point two contingencies also become obvious. First of all I would argue that notions such as, for instance, ‘civil liberty’ or a ‘communist society’ represent rather less tangible objectives compared to the future profits made possible by solving irrigation problems or forming fishing cooperatives, as in the cases presented by Ostrom (1990). Political ideologies, and not least liberalism and socialism in the nineteenth century, were to a great extent about commitment to different, however vaguely defined, visions of society, as much as more immediate, material considerations of the kind envisaged by Hume, or Ostrom. Secondly, the task faced by nineteenth-century liberals of creating new forms of political association on the basis of commitment to an ideology, would also have had to include finding theoretical arguments in favour of practical solutions to organization. This, as I will demonstrate in the following chapters, proved to be difficult, considering the emphasis put on the role of the individual and enlightened citizen, rather than on collective agency.

Arguably, the problem of inventing proper organizational mechanisms for the restraining of self-interest gradually became more difficult to manage, once the first steps towards universal suffrage had been taken, and the problems of mass politics became increasingly apparent. As I have stressed, voluntary association, political association included, is not only about commitment to a common good, but also about building trust. Organizations do not, as a rule, work, or in any event operate only poorly, if those involved do not trust the organization as such, or one another. Apart from the ideological dimension, this issue also involves what could be termed a problem of scale, analogous to what Dolšak & Ostrom (2003: 23) point out is the case with so-called common-pool resources of high complexity. Put simply: size matters, and social trust is normally more easily generated in relatively small, homogeneous, and locally contingent environments, involving limited numbers of individual agents (e.g. Ostrom 1990: 189; other examples are presented in Åberg & Sandberg 2003: 121, 127). Although ‘anomalies exist’ in the pattern, one successful case mentioned by Ostrom included only 100 members, whereas other types of association presented included multi-layered, agricultural federations based on local units ranging in size from 20 to 75 members (1990: 188–189, quote at 188).

Certain implications follow from this, if we take stock of liberal organizational strategies from a historical perspective. If we hold face-to-face interaction to be instrumental in the formation of trust, it is easy to see how the idea of social cooperation–based on the union of small numbers of dedicated citizens, and (before universal suffrage) would-be citizens–can fit with the liberal celebration of the individual and of individual achievement. This is particularly true if we look more closely at the evolution of liberal movements during the first half of the nineteenth century (chapter 2). However, small-scale forms of association are not necessarily easy, or perhaps at all possible, to transform into political association on a mass basis–the kind of scenario which emerged by the end of the nineteenth century. Later I will demonstrate how contemporary liberals had few, if any, organizational antecedents that could be used as blueprints for organizing mass parties. Rather, the blueprints for electoral mobilization and election campaigning were drawn on the basis of other prototypes, resulting in a mixed and loosely integrated organizational structure.

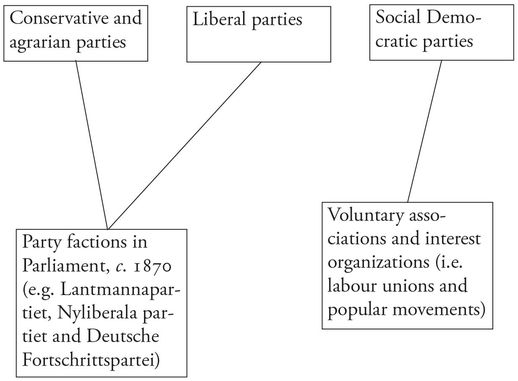

Figure 1. The party systems in Sweden and Germany: their main roots according to Duverger.

The only type of parties hitherto known in Sweden and Germany in the late nineteenth century were those entrenched in the interests of traditional elites and intra-parliamentary factions, i.e. elite parties. The basic difference between the two modes of political association which I have outlined was formalized by Maurice Duverger (1967 [1954]) in his classification of party lineages (although he spoke of them in terms of cadre parties and mass parties). Thus, Duverger made a distinction between parties that had intra-parliamentarian origins, and those parties that had evolved from various extra-parliamentarian interest groups. According to this model, such parties would include, for instance, the Swedish ‘Lantmannapartiet’ (which appeared in 1867 and mainly represented agrarian interests) in the former category, but also the short-lived liberal faction ‘Nyliberalerna’ (1868–71), or the left-liberal ‘Deutsche Fortschrittspartei’ (German Progressive Party) established in 1861. Most notably the Swedish and German Social Democratic parties, however, belonged in the latter group (Figure 1).

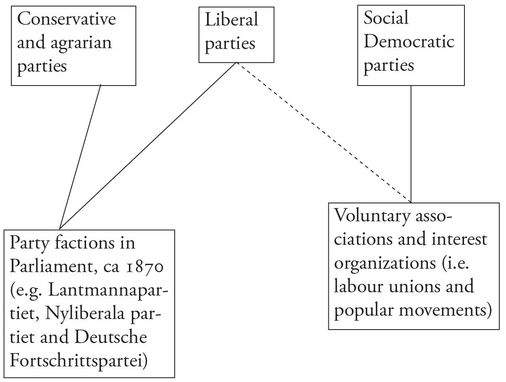

The lineages inspired by Duverger’s model, though, were at no point in time as clear-cut as Figure 1 indicates. Rather, in Sweden as well as in Germany and, indeed, most other countries, it is a well-known fact that early liberalism also owed a lot to the, albeit poorly coordinated, activities of relatively small local and regional level educational and temperance societies, workers’ associations, welfare organizations and similar types of associations (see, for instance, Jansson 1985; Bernstein 1986; Breuilly 1994; Hurd 2000; Langewiesche 2000 [1988]; Gross 2004). Later on the Swedish popular movements (in particular nonconformist religious movements and organized teetotalism, such as the International Order of Good Templars and, in particular, the Blue Ribbon, (‘Blå bandet’) 12 became important arenas for the liberals; this in line with my hypothesis of political association by proxy (see also Back 1967; Lundkvist 1977). Also, the press played an extremely important role in promoting and spreading liberal ideas to a wider audience, in Värmland most notably Karlstads-tidningen, and particularly so under the editorship of Mauritz Hellberg from 1890 onwards (chapter 3). Liberalism in the German states, and in Prussia and its provinces, shared the same dual quality of originating both on the basis of intra-parliamentarian factions and from the activities of local-level organizations, including various ‘Bürgervereine’ (chapter 4). And, as in Sweden, newspapers such as the Kieler Zeitung represented one of the most powerful tools for disseminating ideas and mobilizing voters (although, in contrast to Sweden, the press–viz. the socialist and left-liberal press–was under close surveillance by the official authorities).13 Thus, properly modified, the branching of party lineages should rather resemble Figure 2, if we consider liberal parties.

Although the extent and nature of linkages between the first generations of voluntary and civic associations and, in the case of Sweden, the popular movements have been a topic of dispute (most recently Abelius 2007), it is at the same time obvious that in particular the former kind of organizations were ideologically close to early liberal ideas of the individual as an enlightened citizen and active participant in the civil society. These associations represented social cooperation stemming from close, face-to-face interaction. Indeed, the historian, philosopher, poet and composer Erik Gustaf Geijer, born and bred in Värmland, argued that the rise of associations represented nothing less than the spirit of a new era in social life (Geijer 1845: 35–36); however, on other occasions he was also careful to stress that the family, historically speaking, represented the oldest and most fundamental type of social organization (Geijer 1844: 4). It is certainly difficult to imagine a kind of association any more small-scale than the latter. Geijer was perhaps not a ‘typical’ liberal of his time (but, on the other hand, so were very few liberals, due to the diverse make-up of their ideological convictions; on Geijer specifically, see Petterson 1992: 246–58), yet his basic views on the foundations of social cooperation were not in any sense unique among liberals during the first half of the nineteenth century. At the same time, however, the social and political development during the crucial years of the 1840s–not least in Germany–made it abundantly clear that any attempt to transform society according to the liberal creed would also have to rest firmly on mass support and mass organization.

Figure 2. The party systems in Sweden and Germany revisited.

The geographical setting–Värmland and Schleswig-Holstein

It is hard to find two regions that are as different as Värmland and Schleswig-Holstein, both from a historical point of view and with respect to their institutional setting. Värmland, to begin with, is located in western central Sweden, and borders the neighbouring country of Norway. It is a border region, but not in the sense of a contested, multi-ethnic border region that has been shifted between states throughout history. Excepting that the proximity to Norway was of some importance to the political climate in Värmland (Norway modernized more rapidly than Sweden in certain respects; see chapter 2), the geographic variable was of no direct importance to political association. This was certainly not the case with Schleswig-Holstein. Unlike Värmland, this mixed German–Danish region does, indeed, carry the tradition of being contested. In brief, it was the ancient political and diplomatic peculiarities of the region that induced Lord Palmerston to make his famous remark on the difficulty of how to decide the legal status of Schleswig-Holstein.14 These circumstances filtered back into organized political life long after the region had been incorporated as a Prussian province in 1867 on the North German Confederation. Matters of national identity, then, complicated political life. For instance, the Danish minority entered the parliamentary elections with their own candidates, much in the same manner as the Poles in the eastern borderlands of Prussia organized separately in the parliamentary (Reichstag) elections (Suval 1985).

Patriotism and the issue of nationhood, to be sure, provided the outer perimeter of liberalism in both Sweden and Germany, but whereas modern nationalism in Sweden developed within clearly defined borders, and was based upon ethnic and linguistic homogeneity, the German nation-state was still little more than an idea around 1850. At the same time the break-up from Denmark, and the relationship with Berlin and Prussia, posed a problem of some concern in Schleswig-Holstein. In particular the prominent role played by the military in Prussian society, and the implementation of three-year conscription, were met with criticism. Yet, to many prominent leaders in the region, including the left-liberal professor Albert Hänel in Kiel, the future of Schleswig-Holstein and Prussia was, for better or worse, fused. In addition, the liberal parties in the region–national liberals and left-liberals alike–should also be considered as more right-wing compared to their national counterparts (Schultz Hansen 2003: 459–60; Ibs 2006: 138, 144, 146).

Notwithstanding contrasts such as those indicated, Värmland and Schleswig-Holstein do appear similar in one key dimension: the relative strength of the liberal movement in these two rural regions during the latter part of the nineteenth century and the beginning of the twentieth century. Let us first return to Sweden and the 1911 general election. On the national level the social democrats more than doubled their number of seats in parliament, primarily at the expense of the conservatives. the liberals, at the same time, defended their previous results from the 1908 elections. In Värmland, however, they fared better than this (although Värmland was not an extreme case of liberal voting in the same manner as, most notably, the northern province of Västerbotten).15 Whereas the liberal turnout on a national level was 40.2 per cent in 1911, it reached 46.1 per cent in the Värmland constituencies (Table 1). Since the social democrats simultaneously gained votes, it was the conservatives who lost support in this case, too.

Table 1. Liberal votes in the 1911 and 1921 general elections: national and regional level results (per cent of votes cast).

| Election year | 1911 | 1921 |

|---|---|---|

| Värmland | 46.1 | 29.5 |

| National average | 40.2 | 18.7 |

Source: SOS. Allmänna val. Riksdagsmannavalen 1911 and 1921.

Although the period from 1911 to 1921, and the introduction of universal suffrage, marked a period of expansion for the social democrats and a gradual decline for the liberals, the latter were successful in defending their position on the regional level. As late as the 1921 elections, 29.5 per cent of the votes cast in Värmland were in favour of the liberals, compared to a national average of 18.7 per cent (Table 1). Despite the region turning more and more ‘red’, i.e. social democratic, Värmland remained relatively speaking more ‘liberal’ in contrast to many other parts of the country. This was the case even after the split of the Liberal Party in 1923 and, as a result, the general weakening of Swedish liberalism as a political movement (chapter 3). Liberals on the local and regional level were somehow, relatively speaking, skilful in sustaining their electoral basis and, indirectly, successful at integrating and representing large social strata in society during a critical period of political modernization.

A similar pattern is typical in the case of Schleswig-Holstein, although the German liberals, while organizing earlier compared to in Sweden, were also divided into more parties, which occasionally merged and cooperated. For example, in the 1884 general elections, the Schleswig-Holstein liberals (national liberals and left-liberal factions together) received a total of 62.1 per cent of the votes in the region compared to a 36.9 per cent national average (Table 2; in particular the left-liberals fared well, in contrast to the national level results). In the 1890–1912 period, during which the Social Democratic Party gradually consolidated itself as the largest political party in Germany, liberalism still managed to hold its ground in the region, despite split-ups and setbacks (Ibs 2006: 152–53). In the 1912 elections the liberal parties in Schleswig-Holstein received a total of 43.2 per cent of all votes, compared to a national average of 25.9 per cent (Table 2). After the First World War and the introduction of the Weimar Republic, however, the situation shifted, only more rapidly and in a different direction compared to Värmland.

Table 2. Liberal votes in the 1884 and1912 general elections: national and regional level results (per cent of votes cast).

| Election year | 1884 | 1912 |

|---|---|---|

| Schleswig-Holstein | 62.1 | 43.2 |

| National average | 36.9 | 25.9 |

Sources: Sheehan, 1978, Table 14.5, 214; Beiträge zur historischen Statistik Schleswig-Holsteins, 1967, Table V 1 b, 73; Sozialgeschichtliche Arbeitsbuch, II, 1978, Table 9 b, 177–78. Note: national level data for 1884, as reproduced by Sheehan, includes votes cast for the National Liberals (Nationalliberale Partei), the Freisinnige Partei, and the Volkspartei (the latter two were both left-liberal parties). For Schleswig-Holstein the data includes the National Liberals and factions under the joint-label ‘Deutschfreisinnige partei’. The data for 1912–national and regional levels–includes votes cast for the National Liberals, and the ‘Fortschrittliche Volkspartei’ (left-liberals).

In the 1919 elections to the new, national assembly the liberals received 27.2 per cent of the votes, but in subsequent elections the situation polarized between the socialist and communist left and the extreme right. With this the liberals rapidly lost support (Tilton 1975; Wulf 2003). In fact, many among those who had traditionally voted liberal eventually turned to the Nazis in the early 1930s. According to Tilton, this was due to the 1920s agricultural crisis and the inability of the Republic to provide relief to the farmers, but also ‘the lack of organization’ among the liberals forms part of his explanation (Tilton 1975: 29–33, 135–37, quote at 137). Indeed, in the July 1932 elections, the Nazi votes cast in Schleswig-Holstein reached 52.7 per cent,16 an ill-boding result. Political modernization therefore ended with diametrically opposed results if we compare Värmland and Schleswig-Holstein in a longer perspective. In that sense these two regions epitomize the outcome of political modernization on the national level with respect to the development in Sweden and Germany during the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries.

At the same time it should be stressed that neither Värmland nor Schleswig-Holstein were ‘typical’ host regions of liberal movements. Liberal regions in the sense that, for instance, Max Weber would have argued, according to his principle of ideal types, would preferably be urbanized and heavily industrialized in the manner typical to the Rhineland, or, in Britain, major industrial centres, such as Manchester. Indeed, considering Germany, Suval (1985) identified a pattern according to which liberal parties were strongest in modernized and, more precisely, ‘Protestant, industrialized areas’, whereas their strength declined ‘with the strength of urbanization’ (Suval 1985: 121). Judging from electoral behaviour, these were similar environments, he argues, to those of ‘American progressivism’, or ‘voting habits in the mid-Victorian English industrial towns’ (ibid.). Persuasive as this conclusion sounds, it is not, however, entirely free of pitfalls. This is because–similarly to the ‘Sonderweg hypothesis’, or sequentialism–it rests on the assumption that there, indeed, exists a historical standard, or a ‘normal’ path of political organization, association, and modernization. The emergence of liberalism, as of all political ideologies and political movements, was more complicated.

As I have pointed out, Sweden as a whole urbanized at a later stage, and at a slower pace, than countries such as Britain and Germany. This created a different framework for political movements. Even so, Värmland was by most standards more rural compared to several parts of the country. Geographically speaking a large region (19,979 km2), it was not densely populated. There were only 260,000 inhabitants in 1910, which made it a small region in comparison to most German counterparts, including Schleswig-Holstein (15,658 km2), which at the same time mustered a population of about 1.6 million (equivalent to almost a third of the entire population of Sweden at that time).17 Towns were few and small, and the only real city in the province was the regional capital of Karlstad. In 1910 roughly a quarter of all people in Sweden lived in cities and towns, but only about one-tenth of the population in Värmland.18 Consequently, the liberal electorate, too, was overwhelmingly rural. In the 1921 general elections, 86.6 per cent of all liberal votes were cast in rural constituencies (compared to an average of 76.3 per cent for the country as a whole).19

Economic, demographic, and social conditions differed if we compare the western, eastern, and northern parts of Värmland, yet some general features should be stressed. The province had a strong tradition of mining and iron processing, industries which–similarly to what had become typical to Swedish industrialization –were located in the countryside, rather than in urbanized areas. This sector, however, was in serious decline by the second half of the nineteenth century. Presumably as an effect of economic crisis, Värmland was also tapped of human resources by mass emigration to North America after 1860.20 And by the end of the First World War there were still only 65 industrial workers per 1,000 inhabitants in the province, compared to a national average of 69.21 Small-scale family farming formed the core of the regional economy and, particularly so in northern Värmland, with forestry as an ancillary industry: In 1890, six out of seven rural constituencies in the province were dominated by small farmers (Carlsson 1953: 19–20). This situation remained stable well into the twentieth century. By 1945 between 50.8 and 88.6 per cent of the population in the northern districts of the province were still employed in agriculture (Nilsson 1950: 162).

At the same time, political radicalism in the shape, above all, of liberalism started to make strong inroads in the region during the last decades of the nineteenth century. This mixture of decline and modernization, and the social and cultural tensions involved, was noted, inter alia, by the Church. In 1899, Claes Herman Rundgren, bishop of the diocese, remarked that much that had once been good in the province had now faded away.22 The Church represented, among other things, traditional value systems, established dogma, and respect for religious and secular authority, but the erosion of the established social order was blamed not only on secularization and political radicalism. The advance of nonconformist religious movements and other popular movements also played an important role in these processes.

Obvious, but nevertheless important to point out, a main reason why liberalism and the Church were at loggerheads with each other related precisely to the issue of individualism; because since life and, indirectly, individuality ultimately was of God’s making, there was a fundamental difference in perspective on existential issues between the Church and liberalism that reached all the way back to the Enlightenment. We should also note the emphasis Rundgren put on the ‘good of tradition’. He thereby struck a particular chord concerning the nature of historical change to which we will return. Declining or not, remarks such as Rundgren’s and others (chapters 2–3) indicate a region looking backwards into history as well as forward to the future.

Liberalism in Schleswig-Holstein similarly originated from the basis of a rural social structure in the mid-nineteenth century. Traditionally, the region was divided into three parts–the west, characterized by independent and relatively well-to-do farmers (in particular Dithmarschen, Eiderstedt, and North Friesia); mid-Schleswig-Holstein, with its small and middle-sized farming; and the east, with a mixture of well-to-to farmers and, above all, large manors (‘Güter’). At the time of the incorporation with Prussia in 1867, circa 70.0 per cent of the working population was employed in agriculture (Ibs 2006: 129–30). Industrialization and urbanization transformed the region during the following decades, thus creating a new class of industrial workers in cities and towns such as Kiel, Flensburg, Neumünster, Altona, and Wandsbek, the latter two on the outskirts of Hamburg. Nevertheless, Schleswig-Holstein still in 1907 belonged to a cluster of north-western German regions which ranked below the national average in terms of industrial employment.23 Roughly one-third of the working population of the region was employed in agriculture, forestry, and fishing in 1907, although conditions varied significantly between overwhelmingly agrarian districts such as Hadersleben, Tondern, or Segeberg, and industrial enclaves such as Altona.24 Similarly to Värmland, finally, Schleswig-Holstein also experienced emigration during the latter part of the nineteenth century; in part for political reasons (following the incorporation with Prussia), and in part because of economic pressure (Lorenzen-Schmidt 2003; see also Grant 2005).25

In terms of urbanization, 39.5 per cent of the population in Schleswig-Holstein lived in cities by 1890, but this was still less compared to the more heavily industrialized regions in central and western Germany. For instance, in Saxony 45.6 per cent of the population was urban by the same time,26 and by 1910 a majority of people in Schleswig-Holstein, viz. 53.4 per cent, still lived in communities with 5,000 inhabitants or less.27 In these rural areas, in districts such as Segeberg, liberalism, although contested, stood strong. As late as the 1912 elections, the mandates in seven out of the ten constituencies in Schleswig-Holstein were still held by liberal deputies, all of them left-liberal (Schultz Hansen 2003: 464). Generally speaking, the division between areas of different geographic and economic make-up was more obvious compared to Värmland, and it became more marked as time passed. However, following Tilton (1975: 135), ‘one could still speak of Schleswig-Holstein as an Agrarland without serious inaccuracy’, considering the situation by the early 1930s. Similarly to Värmland, the pattern therefore reveals both modernization and, if not decline, so in any event lingering traditionalism. This basic similarity between Värmland and Schleswig-Holstein–i.e. a relatively speaking strong liberal tradition in a predominantly rural and traditional setting–constitutes the point of departure for my comparison of the two regions. Political modernization, however, was also a process that unfolded against a background of profound changes in the respective national arenas. First of all we should therefore approach the ‘idea of party’ and how this problem was considered in the Swedish and German historical contexts.