VIII. CATASTROPHE

VIII. CATASTROPHE

Harvard University’s Review of Economics and Statistics for 1937 could have been draped in black crepe:

The year 1937 opened with high industrial activity, sharply advancing commodity prices, and strong security markets, which gave superficial indication of prosperity and perhaps approaching boom; and it closed with the severe contraction of output, sharp reduction in prices, and acute weakness in security markets which frequently mark the initial stage of severe depression.… Full appraisal of the causes of the downturn, and its extraordinary severity, is difficult or impossible… But a basic and decisive weakness of the situation was that the entire recovery since 1933 had developed largely in circumstances which rendered it exceedingly vulnerable. A revival induced mainly by stimulating consumer purchasing power could generate no sustaining momentum.… At colossal cost, we have tested whether stimulated purchasing power can produce recovery; 1937 teaches that conditions had not been generated which could maintain prosperity when the reduction of stimulus—inevitable sooner or later—began.63

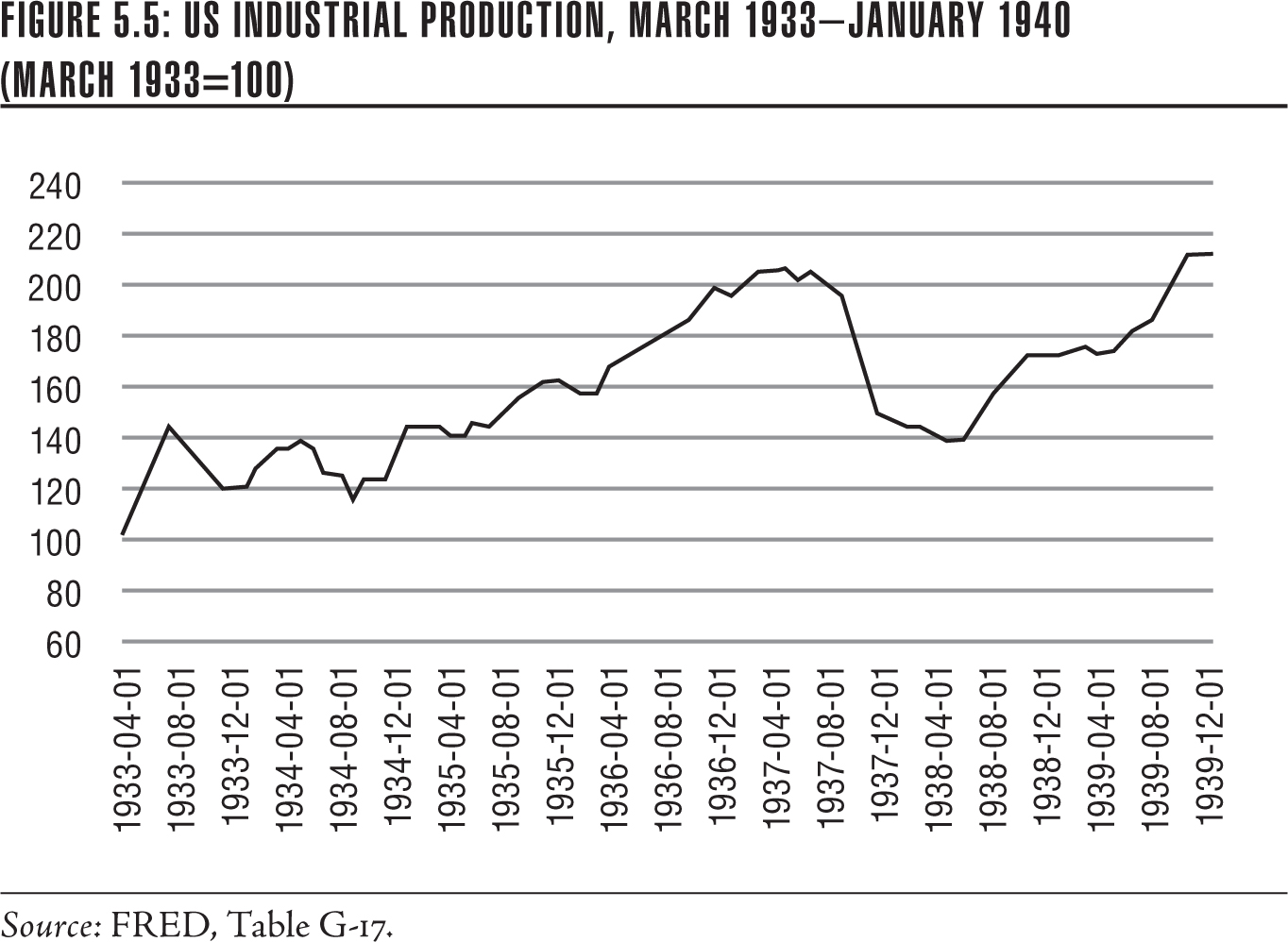

The downturn was extremely steep. Scholars differ as to whether it was the second or third worst in US history, after the Great Depression itself. It was about as sharp as the downturn in 1920–1921, and twice as steep as at the outset of the Depression. Between May 1937 and the trough in June 1938, industrial production fell by 32 percent, employment by 22 percent, and stock prices by 40 percent. The year-to-year drop in quarterly GDP, although less volatile than industrial production, was still a very steep 11.3 percent (see Figure 5.5). The psychological impact of the downturn was much the worse, since it was a complete surprise.64

The 1937 crash—no other word can describe it—was entirely self-inflicted. At heart, Roosevelt was a Dutch fiscal conservative and wasn’t comfortable with the prospect of long-term deficits. Roosevelt was genuinely worried about the rising levels of federal spending, and in his 1936 campaign, he made a special point of returning to balanced budgets. He was strongly reinforced by Morgenthau, the skittish Treasury secretary who, along with many enlightened businessmen, was nearly in a state of panic over runaway deficits. Wholesale prices had jumped in 1937, and to fiscal managers of the 1930s, who had seen the damage done by runaway inflations in Germany and France, alarm bells were sounding.

Roosevelt’s budget message to the Congress in April 1937 was framed around the necessity for frugality—“for eliminating or deferring all expenditures not absolutely necessary,” with no passes given to the “emergency” programs of the original New Deal measures. Few programs were slated for elimination, but sharp cuts were planned for virtually all. The underlying message was that the New Deal had won, the economy had been enjoying near-record growth, employment was rising, factories were starting to hum, and agricultural earnings were looking quite healthy. The 1937 budget (for the fiscal year ending on June 30, 1937) cut the deficit from 5.1 percent to 2.4 percent. The 1938 budget was actually balanced within a tenth of one percent. Then, mystifyingly, everything fell apart.65

Time magazine weighed in with a long leading article in September:

When brokers cleared their desks fortnight ago, hustled out of town for the Labor Day weekend, the market had been falling steadily for three weeks. Supposedly it had fully discounted both war in China and a sudden wave of pessimism over fall business prospects. But the day sun-browned brokers returned from their holiday, a first-class European crisis burst on the front page.… When the closing bell bonged that day 385 stocks had touched bottom for 1937, and all three Dow-Jones stock averages had reached new lows for the year.… European stockmarkets showed no similar apprehension. Markets in Paris and London declined but never approached a break.

For two days after the Tuesday break the market seemed ready for a healthy rebound. Then, without war-scare, labor trouble, Washington slams or serious business news, the market nose-dived again. In the widest break since Oct. 17, 1930, on a volume of 2,320,000 shares—some three times the average daily trading for the past few months—463 stocks set new lows. In the words of old Alexander Dana Noyes, financial editor of the New York Times, the ready rationalizers of the market’s behavior were “completely nonplussed.”

By numerous industrial indices August was the best eighth month of any year since 1929. The Department of Commerce estimated last week that the 1937 national income would reach $70,000,000,000—12% ahead of last year and highest since 1930.… [Yet] another wave of selling hit the Exchange, sending prices crashing for the third time in seven days. Declines from the day’s high to the day’s low were reminiscent of November 1929.

Wall Street came to the inevitable conclusion that it was all the fault of the New Deal.… Purpose of restriction on inside trading, like that of all the New Deal’s securities regulations, was to make the market safe for the true investor. Violent and unjustified fluctuations were to be ended. Wall Street last week was asking whether the result, ironically enough, was to make the fluctuations more violent and unjustified than ever.66

But there was much more going on, much of it deflationary. For one thing, the 1936 Congress, over Roosevelt’s veto, had authorized full payment of the veterans’ bonus in 1936. The total amount was $1.7 billion, of which $1.4 billion had been cashed. The 1937 fiscal year therefore started with a big drop in national spending. Roosevelt also pushed through a steep tax increase, almost doubling the bite on upper-income taxpayers that took effect in 1937. That came on top of the first year of Social Security tax collection—$1.6 billion extracted from employers and workers, with benefits not to be paid until 1942 (later moved ahead to 1940). Then the Federal Reserve Board decided to reduce the level of banks’ excess reserves, which, thanks to the gold inflows, had ballooned to about $2 billion worth. In principle, those reserves could support thirty times that amount of new lending, which monetary alarmists viewed as an inflationary landmine. From 1936 through 1938, the Fed doubled reserve requirements in three separate steps, which Friedman and Schwartz viewed as a significant monetary tightening.67

On top of that, Roosevelt imposed a new tax on net business earnings not distributed as dividends, with tax rates on a steep sliding scale based on the percentage of undistributed earnings. (The idea was that investors would invest dividends more intelligently than self-centered corporate executives.) Roosevelt had proposed it as a replacement for the corporate income tax, but Congress passed it as an additive tax, which he went along with. Then the National Labor Relations Act, better known as the Wagner Act, reinvigorated the union movement. There were a number of strikes in 1935 and 1936, and wages for industrial workers rose by about 10 percent. Neoclassical economists have also argued that Roosevelt’s court-packing drive, his criticisms of businessmen as “economic royalists,” his tax increases on the wealthy, created a “regime change” in Temin’s and Wigmore’s sense that was inimical to investment. Finally, the Federal Reserve and the Treasury agreed that to reduce the inflationary pressures, the Treasury would sterilize the still-strong gold inflows from Europe and Asia.*68

To the modern eye, it might amaze that the country’s policy makers were not aware of all those deflationary bombs. But it wasn’t entirely their fault. In the 1930s, a national economy was still a hazy and shifting entity, like a galactic gas cloud. Basic concepts like GNP hadn’t been invented yet. The Census Bureau had long tracked business activity, and Herbert Hoover, when he was secretary of commerce, began to publish monthly activity data, but no one pretended that it was comprehensive. It was only in the 1930s, in great part because of the shock of the Great Depression, that the economist Simon Kuznets and the National Bureau of Economic Research were engaged by the government to prepare a comprehensive set of national income accounts. By the mid-1940s, the completion of national product and expenditure accounts enabled the creation of complete GNP accounts.

Monetary theory had also been around for a century at least, but its importance wasn’t fully elucidated until the famous Friedman and Schwartz Monetary History, which was published in 1963. Many of the basic concepts of monetary policy had been noted by Keynes, Fisher, and others, but the greater part of the Friedman-Schwartz conceptual apparatus was a post-World War II development. Seemingly obvious facts, like the difference between real and nominal interest rates, were not yet part of the official 1930s conversation.69

Roosevelt’s initial reactions to the 1937 crash were reminiscent of Hoover’s in 1930. In October, he told his cabinet, “I have been around the country and know conditions are good. Everything will work out if we just sit tight and keep quiet.” That initial bravado quickly dissipated. Morgenthau, at the Treasury, noted that “The White House has the jitters,” which Morgenthau was certainly contributing to. A few days after the stock market slide, he wrote the president, “I have had to come to the conclusion that we are headed right into another depression.” A Fed advisory committee warned darkly of “another major depression.… Plants are closing down every day. Thousands and thousands of production workers are being laid off every day.… Such movements gather their own momentum and feed upon themselves.” In early 1938, when the economy was sliding at an alarming rate, Harold Ickes confided to his diary, “It looks to me as if all the courage has oozed out of the President. He has let things drift. There is no fight and no leadership.”70

The recession lasted for just about a year, from the summer of 1937 to the summer of 1938. What turned it around was a resumption of government stimulus. The most important action was ending the sterilization of gold. The sterilization had started in November 1936, and over its life it sequestered about $1.4 billion of gold. $300 million of that was released in September 1937, but for technical reasons, not as a conscious stimulus. Perversely, the sharp US downturn also slammed shut the foreign gold pipeline—traders had seen Roosevelt resort to a gold revaluation before and feared he might do so again. In April 1938, the Treasury desterilized the remaining gold, and spent it down, or “monetized” it, over the next year. Worryingly, the gold flow from Europe did not resume immediately—once burnt, twice shy, perhaps—but the Nazi move on Czech Sudetenland in the fall of 1938 panicked wealthy Europeans, and the gold flows picked up briskly. By this time, gold accounted for about 85 percent of the US monetary base.71

For his part, Roosevelt finally cast aside his pose as the prophet of balanced budgets. Hopkins, recovering from stomach cancer, sent him a note showing that unemployment had risen by 2.5 million since the previous summer. Marriner Eccles, the Federal Reserve chairman and perhaps the only committed Keynesian in the administration, had protested the budget balancing fervor from the start, and was a strong internal voice for more stimulus. The WPA and PWA had shelves of already-designed projects, and the RFC had plenty of bonding capacity in its financial arsenal. Congress shed its fear of spending and meekly pushed through $2 billion in direct spending, $1 billion in direct project lending, plus an additional $1.5 in RFC borrowing. The total stimulus, counting the newly desterilized gold, ran to nearly $6 billion. Assuming the spending was pumped into the economy over a period of eighteen months or so—Hopkins was master of getting money out fast—the stimulus effect would have been about 4 percent of GDP, which would make a difference. Add to that the resumption of large gold inflows from abroad and the strong growth pickup for the rest of the decade is fully accounted for. (That number also tracks with the stimulus bulge calculated by Eggertsson (see Figure 5.3).72

Modern research has also elucidated which of the alleged deflationary agents were important in inducing the downturn and which weren’t. The current consensus seems to be that the Social Security tax was of little significance. Tax proceeds were used to purchase government securities to be deposited in a trust fund. Holders of the government debt, in other words, received cash for their securities, which they could spend or reinvest as they chose. Recent experience, however, suggests that the consensus is wrong. Wealth and income were about as concentrated in the 1930s as they are now. Any process that funneled money from paychecks to buy bonds from wealthy people had to be contractionary. (The trust fund arrangement was dropped in 1940 and the system was put on a pay-as-you-go basis.)

The Fed’s focus on excess reserves, however, was probably of little consequence, despite the criticisms of Friedman and Schwartz. The level of excess balances was so large that the reserve increases did not restrict banks’ ability to lend. After the 1933 banking crisis, most banks maintained high levels of precautionary liquidity, and with interest rates so low, idle balances were not a drag on earnings. One or the other reserve districts, especially New York, experienced brief episodes of tightness, but they could be explained better by local policy decisions than by the Fed’s actions.*73

Another chip in the 1936 Roosevelt legislative package—the tax on net undistributed earnings—turned out to be a bad idea and was repealed after two years. The tax particularly weighed on smaller, entrepreneurial, technically advanced companies. Because they were small, they had to pay prohibitive fees of 25 percent and up to tap public markets, so it was economically efficient for them to use their earnings for research and development instead of returning them to shareholders. It is probably true that the tax increases on the very wealthy reduced their propensity to invest. Similarly, it is likely true that the worker strikes and wage increases were seen as elements of a “regime change” by businessmen, whose feelings of besiegement may have hastened the onset of the 1937 crash.

Businessmen must have quickly learned to swallow their anxieties, however, for the wage hikes and the regulatory initiatives were still in effect when very rapid growth resumed in mid-1938—even in the face of a new and very aggressive antimonopoly drive. The neoclassical economist Lee Ohanian argues that regime-change-type effects are evidenced by the “weak” 1933–1940 recovery. But that is a strained description, to say the least. From 1933 through 1940, a period that includes the 1937–1938 recession but ends just before the upsurge of wartime spending, the economy turned in a seven-year average real growth rate of 7.2 percent, the fastest peacetime growth in history. By way of comparison, it was much faster than the 5 percent annual growth rate in the eight years from 1921–1929, which includes the double-digit growth coming out of the 1920–1921 crash.74