In the spring of 1941 Gen. Russell L. Maxwell’s vulnerability project overstretched the mission of his agency. The Export Control Administration, as its founding purpose, was charged with conservation by limiting exports of materials the president deemed vital for national defense. Most of the designated commodities were in short supply in the United States, or threatened to be, especially after passage of the Lend-Lease bill. The vulnerability teams, by recommending embargoes of Japan specifically, moved a step toward setting foreign policy. They traveled even further in that direction by urging termination of exports to Japan of commodities that were abundantly available, such as phosphates, oil, and some other minerals and chemicals. Ultimately, seeking to burst the bonds of their assignment, they investigated the products the United States imported from Japan, recommending embargoes of most. To cut off the United States from a source of useful products was a far cry from conserving for national defense. To the contrary, it would impose burdens by cramping production of some industries or depriving U.S. consumers of products they desired. The rationale for such a move was harsh: to directly injure Japan by denying it dollars to spend in the United States or other dollar countries, for strategic or other materials, and, in the extreme, to disrupt the Japanese economy and distress the Japanese people. The vulnerability analysts were indulging in the culture of opportunism blooming in Washington as bureaucracies sought to seize control of and direct economic foreign policy against Japan.

The foremost imported commodity under study was raw silk, which comprised two-thirds of the value of Japan’s exports to the United States and virtually 100 percent of the U.S. supply. Sales amounted to $107 million in 1939 and $105 million in 1940, 95 percent of it destined for women’s hosiery. Raw silk, in fact, comprised 25 percent of all Japanese exports outside the yen bloc, but the benefit to Japan was far greater. Most other exports contained foreign raw materials, whereas silk was entirely of domestic origin. Raw silk yielded about 57 percent of all U.S. dollars Japan earned from exporting to North and South America at a time when dollars were essential to purchase war materials. The great bilateral silk trade had survived many a shock over seven decades, but a year before the vulnerability project it encountered an appalling, and ultimately catastrophic, shock on “Nylon Day.”

The fifteenth of May 1939 was Nylon Day at the New York Worlds Fair, a day of lavish promotion of a new kind of full-fashioned hosiery. The stockings were an instant hit. Women across the country thronged the counters of department stores to buy stockings of gossamer nylon, sheerer than the finest Japanese silks, that clung smoothly to their legs in unblemished beauty. E. I. du Pont de Nemours and Company, whose motto was “Better things for better living through chemistry,” had recruited Dr. Wallace Hume Carothers from Harvard University to research the creation of a perfect artificial silk. In 1934 he triumphed by creating a long-chain polymer from coal, air, and water, the first true synthetic fiber, not derived from wood or vegetation. Du Pont called it nylon. The extruded yarns were strong, light, stretchy, and absolutely uniform. Test-knit stockings fulfilled the company’s fondest hopes. It erected a plant in Seaford, Delaware, that, in December 1939 began to produce four million pounds annually, reserving nearly all the output for hosiery mills. In 1940 nylon took 7 percent of the hosiery market, and its share was growing rapidly as Du Pont lowered yarn prices.1

For the ECA vulnerability project, Ruth E. K. Peterson—the reigning expert of the U.S. Tariff Commission, the only one-person “team,” and perhaps the only woman in the project—reported on the outlook for hosiery on 15 April 1941. Du Pont was doubling the capacity of its Seaford nylon plant to eight million pounds and building another plant for hosiery, except 10 or 15 percent for nylon bristles to replace Chinese hog bristles in paint brushes and for other uses. Peterson stated:

Another Du Pont nylon plant is under construction at Martinsville, Va., which is to have a capacity of 8 million pounds . . . to be in full production in the spring of 1942. The hosiery industry probably consumes about nine-tenths of the total nylon yarn production, and can manufacture approximately 20 pairs of hose from each pound of nylon [vs. 12 from a pound of raw silk due in part to wastage in throwing]. On this basis [Du Pont] . . . would provide within the year sufficient nylon to manufacture between 140 and 150 million pairs, equivalent to about 30% of the total output. . . . Should the industry consume 85% of the 16 million pounds of nylon which are expected to be available in 1942 it would be able to make 272 million pairs of nylon hose or 54% of the present annual rate of production of full-fashioned hosiery. If it is true, as many consumers claim, that nylon hose outlasts silk, then any given output of nylon would actually displace more than the corresponding number of pairs of silk hose.

Raw silk stocks on hand in the United States were only one and a half months’ worth of normal demand. Peterson shrugged off the immediate unemployment of 133,000 U.S. workers that would result from an embargo of raw silk because stocking mills would switch to other fibers. Only the 18,000 engaged in throwing silk were in jeopardy because nylon and rayon did not require throwing.2

Peterson’s assumption that Japanese silk would retain nearly half the future hosiery market was challenged by Wirth Ferger, an analyst of the Far Eastern Committee of the ECA, on 27 April 1941. He accepted Du Pont’s claim that nylons lasted up to twice as long as silks if properly washed, and that customers would accept other fibers in feet and welts. Nylon stockings, he calculated, would capture 100 percent of the full-fashioned hosiery market by the end of 1942. Silk stockings would disappear, and there would be no other outlet for Japanese raw silk.

Peterson had refrained from recommending sanctions against Japanese silk, unlike most of her colleagues on vulnerability teams. The outspoken Ferger advocated step-by-step actions to hinder Japan’s war effort: promoting and subsidizing nylon, tariffs and licensing restrictions on raw silk, and finally a funds freeze and total embargo. “Through the indirect effect of curtailing her supply of exchange available in this country for purchase of supplies she needs,” he said, Japan would feel a “real pinch disrupting her internal economy,” even though silk workers could migrate to other jobs. U.S. export controls would be “the first and primary measure” in “a general offensive plan.” Interestingly, Ferger assumed a program lasting two years during a period of general emergency, a rare explicit assumption of duration that was scarcely mentioned by other analysts’ studies in the spring of 1941 and not at all in July, when the financial freeze was imposed.3

In September 1941, after the freeze of trade, Ruth Peterson came to the same conclusion about the market. Women demanded sheers and ultra sheers (four to five thread and two to three thread, respectively) for 89 percent of their purchases of full-fashioned hosiery but accepted other fibers for feet and welts. Even though considering nylon’s run resistance unproven, she forecast a shortage of high-quality hosiery in 1942 if raw silk were embargoed. Women would then have no choice but to wear bulky, unsightly rayon and cotton stockings, six-thread or more, if production of such yarns were stepped up, otherwise heavy sport hose or ankle sox. She expressed no sympathy for women’s loss of a treasured fashion accessory.4

U.S analysts also delved into Army and Navy needs of silk parachutes—the cry of aviators bailing out was “Hit the silk!”—and for flares and pyrotechnical signals. A man-carrying ’chute required 11.7 pounds for canopy and shrouds. Given Roosevelt’s goal of fifty thousand airplanes and assuming an average four parachutes each, the 2.34 million pound requirement of raw silk was a mere four weeks of imports from Japan. The ECA estimated parachute demand at only 1 to 2 million pounds of raw silk, which easily could be supplied by commandeering industry stocks, said to be 11 million pounds, or by using nylon, a promising substitute.5

The analysts were more concerned about Asian waste silk, the short fibers from broken cocoons and filature clippings, that U.S. plants drew and spun into low-strength filling yarns. Demand for spun silk velvet clothing had flowered in the 1920s, but by 1939 only 1.1 million pounds were woven into pile fabrics. But very coarse spun silk, 425 to 620 deniers, was needed for cartridge cloth, igniter cloth, and laces for large-caliber naval and coast defense artillery. It burned quickly, leaving no smoldering residue in the gun breech. There were no substitutes. (Cotton and other fibers sufficed for field artillery.) U.S. hosiery mill waste and old silk clothing were unsuitable due to hard twisting of yarn, while chopped-up raw silk lacked the necessary bulk and cost ten times as much. Silk waste imports of 2.5 million pounds in 1940, enough for 2.8 million square yards of naval cartridge cloth and costing about $1 million, came from China via Japanese merchants. (Japan was thought to be conserving its waste silk for its navy.) During World War I, 28.5 million pounds of cartridge cloth had been produced, even though most of the battle fleet was idle, but the U.S. military now held only a 6 million pound reserve of waste silk. Ruth Peterson urged accumulation of 3 million pounds of waste for stockpile. Wirth Ferger clamored to import 8 million pounds. Eventually commercial inventories sufficed for the artillery problem.6

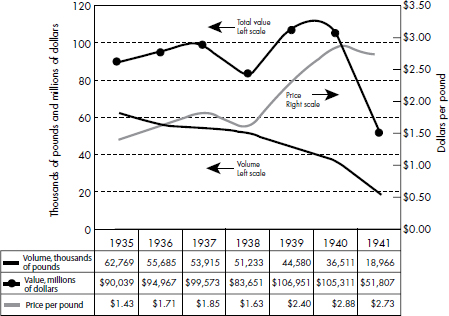

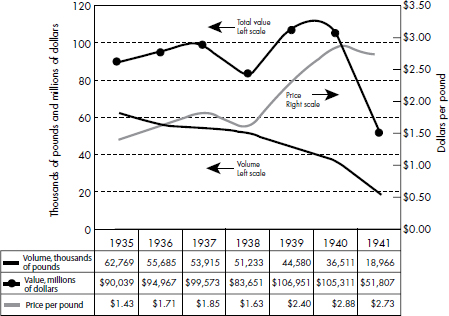

During the four years from the start of war in China to the U.S. financial freeze, Japan earned $394 million from silk exports (chart 15), nearly all for U.S. women’s stockings. It was a source of dollars second only to gold sales of $711 million, which came largely from Bank of Japan reserves. Each year dollars from silk exports were almost twice the value of new gold production (chapter 6). The impending demise of the once-lucrative silk trade may have contributed to a sense of isolation felt by Japanese leaders even before the financial freeze that shut it down, although documentation is not available.

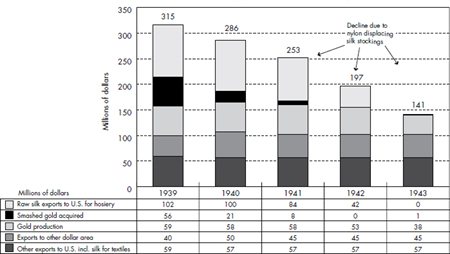

Did nylon contribute to Japan’s choice for war? If it had accepted U.S. demands to withdraw from conquered territories in exchange for reopened trade, could Japan have earned enough dollars to buy materials it needed, especially to support its army and navy? Japan’s trade deficit with the dollar area, partly offset by newly mined gold available to sell to the U.S. Treasury, had averaged $120 million per year before 1941. In 1941 Japan had at most around $250 million of gold and dollar reserves, enough, along with future gold production, to cover two years of dollar trade shortfalls.7 But if nylon entirely displaced $100 million in annual revenue from raw silk, the dollar deficit would expand, reducing the financial cushion to one year (chart 16). Cabinet records in Tokyo do not mention silk, yet the looming trade disaster could not have encouraged any leaders who preferred survival by renewal of trade rather than by war. In any case, during World War II Japan virtually shut down sericulture and uprooted the mulberry trees, permanently sealing the fate of its once-great silk industry.8

Several vulnerability teams investigated some of the articles that made up the rest of U.S. imports from Japan, none large in value. They sensibly recommended against embargoes for a small number of commodities the United States needed while proposing to embargo many nonessential items for the purpose of denying bits of dollar exchange to Japan:

•Fish. The members of a vulnerability committee on fisheries cavalierly dismissed sea foods from Japan as unimportant to the United States. The embargo they recommended “would not work the slightest hard-ship” on U.S. consumers because domestic and Canadian fleets could fill the gap if and when prices rose while Japan would suffer “serious economic injury.” Sensibly recognizing the importance of fish livers for health and nutrition, and the lack of alternatives, they proposed no embargo of Japanese sources (and ignored the seed oysters essential for U.S. shellfish farming).9

CHART 15 U.S. Imports of Raw Silk from Japan, 1935–1941

Department of Commerce, Foreign Commerce and Navigation of the United States, 1936–42.

•Hat materials. A committee reasonably opposed an embargo of hat materials unless the United States launched “all-out economic warfare” on Japan. No substitutes could be had, perhaps for years until production started in the Bahamas or South America or synthetics were developed. An embargo would needlessly injure workers and firms in both countries.10

•Ceramics. A committee opined that the “loss of the United States market alone might seriously disrupt the Japanese pottery industry and would result in an appreciable loss of foreign exchange.” Although halting imports would deny a popular product to the American middle class, dishes were not essential, they declared, recommending an embargo in conjunction with the Allies.11

CHART 16 Japan: Sources of Dollars, Actual, 1939–1940, and Projected, 1941–1943

For 1939 and 1940: Exports to U.S. and silk uses: Department of Commerce, Foreign Commerce and Navigation of the United States and Census of Manufactures (various goods). Exports to other dollar area: Japan Statistical Association, Historical Statistics of Japan, converted to dollars. For 1941 to 1943: Raw silk exports for hosiery calculated by author from AEC, “Preliminary, Summary Report on Silk.” Other exports assumed same as 1940–41. All years, gold production, actual: SCAP, Gold and Silver in Japan. Smashed gold, actual: Survey of the Gold Fund Special Account, c. August 1945, OASIA.

•Miscellaneous wares. A vulnerability committee glanced at dozens of Japanese “miscellaneous products.” The knick-knackery of Japanese toys, beads, shells, buttons, brushes, umbrellas, lacquerware, combs, and the like netted $1 to $2 million for Japan. The committee concluded sensibly, “[It] is too heterogeneous a grouping to make economic warfare feasible.”12

In April 1941 the U.S. vulnerability committees, having recommended an embargo of the $105 million of raw silk imports, considered other Japanese imports, worth $52 million in 1940. In many instances the United States was the main or only market. A few advocated embargoing of $9 million of products they condescendingly called “luxuries” Americans could do without: crabmeat, tuna fish, and chinaware (but for some reason not pearls and mink pelts) to deny Japan bits of foreign exchange, to cause minor disruptions of its economy, and implicitly to hinder the war in China. It was irrelevant to the experts that women and children especially would be deprived of popular goods unavailable elsewhere. Others committees showed common sense in advising against embargoes of $18 million of essential imports: silk waste for artillery, drying oils and paintbrush bristles, and fish livers for health, which were in short supply; irreplaceable hat materials that would hurt U.S. manufacturers; a myriad of inexpensive household articles and playthings deemed too insignificant to study. Nor were cotton textiles to be embargoed, probably because of political sensitivity of U.S. farmers and ginners who normally sold Japan raw cotton four or five times the value of cotton textiles entering from Japan. Other Japanese products ranging from tea and canned fruits to bamboo wares, silk fabrics, light bulbs, and zippers were simply not important enough to study. Most committees paid little attention to the impacts of embargoes on U.S. employment or on the Japanese economy other than its dollar earnings.

Before 26 July 1941 U.S. trade warfare against Japan consisted of curtailing exports of strategic commodities needed for U.S. defense in accordance with the licensing act of July 1940. There was no legal mechanism to halt imports, except a potential executive order to freeze Japanese assets under authority of the 1917 Trading with the Enemy Act. The commodity analysts recruited from various civilian agencies by the Export Control Administration had reached opportunistically far beyond that agency’s authority in urging embargoes of imports from Japan.