As his aides readied financial sanction orders, Roosevelt needed a further political justification for cutting off oil from Japan, even partially. Oil was a unique commodity. It was, of course, the lifeblood of Japanese naval and air forces, and it was vital to segments of the Japanese economy. Japan could only obtain it in adequate quantities from the United States, and if cut off, its reserve in storage tanks would not last very long. Unlike the strategic resources that the United States conserved for rearmament and its Allies, or that were vital to its own economy, there was no domestic shortage of oil or refined products. Nevertheless, to help justify an embargo the president offered a false rationale promoted by his petroleum coordinator for national defense, Harold L. Ickes, that Japanese buying caused a shortage in the United States. In fact, Japanese buying did not at any time pinch American oil users, but the facts were complex. There was both a predicted shortage on the Atlantic Coast and a glut of oil on the Pacific Coast. Roosevelt linked the two circumstances in his policy even though neither coast could solve the other’s imbalance.

In the spring of 1941, California, the only producing state capable of exporting petroleum to Japan, which had limited tanker capacity, pumped 15 percent of U.S. crude production (about the same percentage as today). It drew largely from three regions close to the Pacific Ocean: the San Joaquin Valley, the Coastal District near Santa Barbara, and the Los Angeles basin. The state’s huge reserves had been widely developed by drilling, including most of the world’s wells deeper than thirteen thousand feet. Its theoretical lifting capacity of 3,755,000 barrels per day was almost as large as the actual production of the entire United States. A more realistic measure of its potential, however, was its refining capacity of 810,700 barrels per day, 18 percent of U.S. processing capacity. Pipelines gathered and delivered crude from the oil fields to nearby refineries or to tanker piers for shipment to refineries clustered around Los Angeles. Due to lack of demand, however, a proration committee established during the Depression restricted refinery runs to 613,000 barrels per day. Thus California was home to half the excess refining capacity of the United States. Thirty small plants were idle.

American leaders well knew that California was awash in surplus oil. Despite demand from factories, railroads, and workers as defense orders rose and as avgas refining expanded, supplies were so ample that inventories increased during the first half of 1941. Prices were low: crude averaged ninety-seven cents per barrel in 1941, 17 percent below the price in Texas and 12 percent below California’s own anemic pricing during a 1935–37 economic slump. Although the industry claimed to be losing money, the proration committee further curtailed crude liftings. In May, J. K. Galbraith of the Office of Price Administration rolled back a price increase. No rationale of shortage or defense needs compelled a reduction of exports to Japan from California.

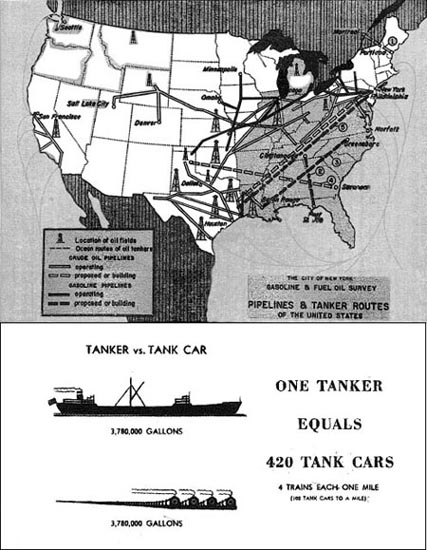

The California oil industry served the Pacific Rim almost exclusively. Refined fuels moved through pipelines as far north as San Francisco (fig. 1). A fleet of about fifty tankers carried products to Washington, Oregon, Vancouver, Alaska, and Hawaii. Until 1941 three tankers had hauled gasoline equivalent to oil production of fifteen to twenty thousand barrels per day, 3 percent of California’s output of all products, to U.S. Atlantic ports via the Panama Canal. A similar volume of products to other Atlantic ports virtually ceased after foreign tankers abandoned Pacific routes. Exports to the Philippines and the Asian continent were minor because the region was more efficiently served from the East Indies. Japan was California’s number one foreign customer, a buyer of fifty-five thousand barrels per day of liquids in the spring of 1941, or 9 percent of the state’s petroleum products. Japan benefited from the arrangement. California’s light crudes yielded high fractions of gasoline and fuel oil. Its heavy crudes yielded residual oil for ships (a major reason the U.S. Fleet relocated from the Atlantic to southern California in 1919). California offered low prices and the shortest haul from any Western Hemisphere producing region, which maximized Japanese tanker capacity and minimized shipping costs. A final advantage, which Japanese diplomats and strategists appeared not to notice, was that California’s oil could not practicably be diverted to Lend-Lease aid for Great Britain.

FIGURE 1 U.S. Oil Pipelines and Tanker vs. Tank Car Capacities, 1941

Congress, Senate, Special Committee to Investigate Gasoline, Hearings, 497, chart 1.

In May 1941 distribution bottlenecks began to hamper the marketing of California’s oil. The U.S. government requisitioned a few Pacific tankers for Atlantic service to Britain and, in June, four or five more to carry Lend-Lease fuels to Vladivostok for the Soviet war against Germany. The chairman of California-Texas Oil Company (later Caltex) calculated that 38 percent of the West Coast tanker fleet was called up for Lend-Lease versus only 18 percent of the Atlantic fleet; there was confusion over numbers, but a significant number were conscripted. Because deliveries along the West Coast were further constrained by lack of railroad tank cars, Washington ordered companies to pool transport and terminal operations. Lack of transportation perversely increased the surpluses in port storage tanks that could be exported to Japan.1

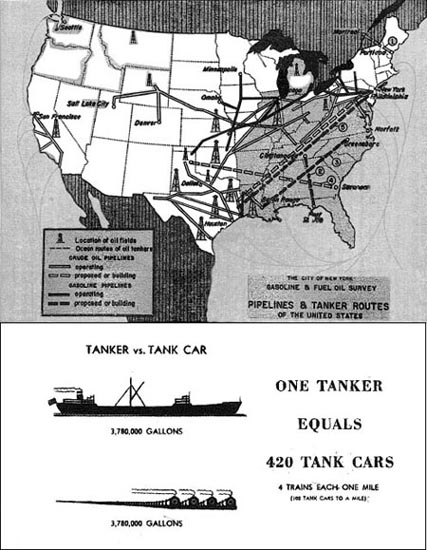

On the Atlantic Coast fuel demand was strong, but California was then totally isolated from that market. No pipeline extended east of Bakersfield, seventy miles inland from the Pacific Coast. No tankers could be spared for the long haul through the Panama Canal. Railroad tank car movement was economically inconceivable, even had the cars been available. For comparison, a car shuttling between Texas and New York could deliver twelve barrels per day on a twenty-day round trip costing $2.37 freight per barrel, an extreme burden on liquids worth $1.00 to $3.00 per barrel versus tanker rates of 56 cents. Rail rates for a six-thousand-mile round trip between California and New York, had they existed, would have been ruinously prohibitive and absurdly inefficient. Truck haulage was unthinkable.

The Northeast, the densely populated, high-income states from New England to Maryland, accounted for half the country’s oil consumption. Some 96 percent of it arrived by tanker, of which 60 percent was refined fuels and 40 percent crude for refineries around Philadelphia and New York. (The southern Atlantic states from Virginia to Mississippi were served by river barges, small inshore tankers, and rail; the industrial Midwest relied on inland waterways and rail.) A fleet of about 250 U.S. seagoing tankers delivered 1.1 million barrels per day from Texas and Louisiana to the Northeast. (Only U.S.-registered vessels with U.S. crews were permitted to carry between U.S. ports.) Tanker capacity was usually so ample that many ships laid up seasonally. Another two hundred thousand daily barrels arrived in the Northeast aboard tankers from Venezuela and Caribbean refineries. The last 4 percent arrived in the western fringes of the northeastern states from midcontinent Kansas-Oklahoma oil fields via river and lake barges or by rail from a small pipeline that ended in Indiana.2

In 1941 Great Britain’s oil situation was growing desperate. The sterling area (Britain and its colonies and dominions except Canada) was desperately short of dollars to buy Western Hemisphere fuels. The United Kingdom had liquidated most of its gold and had commandeered for sale the U.S. securities owned by British investors. Early in the war it had received oil from British-controlled companies in Iraq and Iran that accepted inconvertible pounds sterling, until Italy’s declaration of war in June 1940 closed the Mediterranean route. The alternative ninety-day round trip around the Cape of Good Hope sharply reduced tanker efficiency and was vulnerable to U-boat attacks. East Indies oil, although available at least in part for sterling, was even more distant and in any case was committed to Australia, India, other British domains in Asia, and, since late 1940, Japan (20 percent).

The Lend-Lease Act signed by FDR on 11 March 1941 solved Britain’s dollar problem for the rest of the war. The act authorized shipments of oil without compensation. The British government asked to borrow U.S. tankers to help replenish stocks that had fallen dangerously low despite civilian rationing. German U-boats had been sinking ships faster than the yards could replace them, while delays inherent in convoying imposed a 20 to 30 percent penalty on shipping efficiency. Reckoning 378 tankers needed for the UK, in April 1941 Prime Minister Winston Churchill appealed to the United States, which was “willing, and able, to respond.” Sir Arthur Salter, joint parliamentary secretary to the Ministry of Shipping, came to Washington to confer with Harry Hopkins, FDR’s confidant and director of Lend-Lease. Britain must borrow 75 tankers during the remainder of 1941, he said, assigned at the rate of 20 per month, even if there were no further net ship losses. In June he upped the request to 91 ships. Under the Neutrality Act, U.S. ships could not sail into the war zone, however, and the administration rejected the subterfuge of reflagging them. Negotiations resulted in the famous “shuttle.” U.S. tankers would haul oil and refined products from the Gulf Coast to New York, and sometimes to Baltimore and Philadelphia, for transfer to tankers owned or leased by Britain, cutting its transatlantic haul distance by half and, not incidentally, saving money.3

On 2 May 1941 Roosevelt called on U.S. ship owners and oil companies to release twenty-five tankers for Lend-Lease, twenty of which were from the Texas–East Coast route. Shortly thereafter he raised the call to fifty vessels, about half a million deadweight tons (DWT) of shipping.4 (An average tanker displaced 10,000 DWT, that is, capacity for cargo, fuel, and stores expressed in long tons of 2,240 pounds. One DWT volumetrically ranged from six barrels of heavy oils or crude to eight barrels of gasoline. The approximate average of seven barrels per ton equated to 10,000 tons of fuels per one “tanker equivalent” vessel).5 On 27 May the president’s proclamation of an unlimited national emergency politically reinforced the call (chapter 14).

Roosevelt established the office of petroleum coordinator for national defense headed by Secretary of the Interior Harold L. Ickes, a prickly and opinionated man who called himself the Old Curmudgeon. He was given to angry outbursts, even against Roosevelt, and often threatened resignation. A lawyer steeped in Chicago politics, Ickes had organized progressive Republicans in 1932 to vote for Roosevelt, who rewarded him with the cabinet post, saying, “I liked the cut of his jib.” Ickes, who championed the civil rights of American Indians, minorities, and the oppressed Jews of Germany, joined other cabinet hard-liners in antipathy to aggression. He advocated aid to China in 1938 and an oil embargo of Japan in 1940. Ickes had genuine credentials in energy policy, including management of petroleum reserves on federal lands and of hydroelectric projects, but none in foreign policy. Nevertheless, he searched opportunistically for a role in economic warfare. As petroleum coordinator he gathered data on supply and demand, consulted with the industry, and advised defense agencies how to coordinate actions and fix problems. He recruited as his coequal deputy coordinator, Ralph K. Davies, a vice president of Standard Oil Company of California who had impressed him during a failed push to conserve oil in California. The assignment emboldened Ickes to press vigorously for an oil embargo of Japan, ostensibly to conserve U.S. resources.6

The first shuttle tanker sailed on 21 May 1941. Ship transfers were gradual at first. The U.S. Maritime Commission reported that on 30 June, 243 tankers were still on the Gulf–East Coast service, versus 244 a year earlier.7 But Ickes and Davies calculated that the expected diversion of 20 percent of the Atlantic tanker fleet would inevitably cause shortages on the East Coast. They reckoned that the brunt of the shortage would occur in gasoline, the largest volume product yet the one most easily sacrificed because “pleasure driving” was thought to be widespread (although no studies backed the presumption). Assuming no reduction of fuel oil for factories, trains, and home heating, they predicted an imminent shortage of 33 percent of gasoline supply on the East Coast.8

As to the Pacific, since late 1939 Ickes had warned FDR that oil conservation would some day be necessary in California and that public sentiment there was adverse to supplying Japan. On 8 June 1941 he wrote in his diary, “I went into action about Japan.” He demanded from General Maxwell the roster of Japanese licenses approved by the ECA and insisted that no new ones be issued until he received it, apparently unaware of the recent stalling actions by the export controllers. He singled out a cargo of lubricating oil loading in Philadelphia for Japan as a test case for restrictions. Davies sent a telegram to all shippers to cease exporting, without approval, oil products from the Atlantic Coast except to Western Hemisphere countries, Britain, and British forces in Egypt. The State Department bridled that oil export was a matter of extreme importance to its foreign policy. FDR sided with Hull. In a “peremptory and ungracious” letter he warned the Old Curmudgeon to desist. Ickes grumbled that loading-point control was his prerogative as domestic oil czar and that Japan could load up on the Gulf or West Coasts, where no shortages loomed. After he threatened to resign, he won his point. Shipments to Japan from the East Coast ended. Shipments from California, however, continued without hindrance. The president specifically declined to revoke a Japanese license for 5.3 million gallons (about 650,000 barrels) of gasoline in drums. Ickes, growling that Americans should not deprive themselves “to appease Japan,” was delighted when Dean Acheson applauded his agitations.9

By the middle of July 1941 forty-three U.S. tankers were shuttling oil on behalf of Britain, yet industry executives expected no gasoline shortage on the East Coast. Crude oil and refining capacities were ample for all needs; transportation was the only bottleneck. Throughout the spring and summer they publicized their views in the authoritative Oil and Gas Journal, as early as 15 May listing compensating efficiencies their firms could implement. Gulf Coast refineries, for example, were installing pumps to double loading flow to eight thousand barrels per hour, which cut idle tanker time by fifteen hours and round-trip time by 5 percent. On 10 July the journal listed possible actions that could make up for as many as one hundred “standard tanker equivalents.”

Forty-nine ships by increasing voyage capacities:

•Twelve ships by deep loading to natural safety lines rather than an overly conservative international treaty line. On 10 July Congress authorized it.

•Eleven ships by eliminating hauls to the East Coast from the Caribbean and California, cross-hauls, and multiple-destination voyages.

•Eighteen ships by commandeering neutral and Axis tankers sheltering in Western Hemisphere ports. (The industry was poorly informed. A later investigation found that of twenty-two such vessels, ten were damaged and nine neutrals were already carrying Mexican oil to the United States.)

•Eight ships by advancing the shuttles of Venezuelan oil to Halifax, Nova Scotia, instead of New York, shortening the British haul and releasing borrowed U.S. tankers. (This proved unacceptable because under the Neutrality Act Canada was a belligerent.)

Up to forty ships by substituting other transportation:

•Nine ships by increasing throughput of small pipelines from midcontinent to inland cities of the Northeast.

•Four to six ships by increasing barge movement and substituting barges for tankers on rivers, lakes, and canals.

•Twenty-five ships by railroad tank car movement. (Highway tank trucks were unsuitable for long hauls.)10 The Railroad Association, then lobbying against allocation of steel for long distance pipelines, claimed to know of 20,000 idle cars. Petroleum experts were dubious because some cars were in seasonal reserve or in disrepair, and locomotive and platform bottlenecks were common. A later survey by Ickes’ OPC turned up only 5,192 idle cars.

The industry’s wish list of substitutes for about one hundred tanker equivalents was overly optimistic, but compensating for fifty seemed feasible in the short run. In the longer term sixty new civilian tankers were scheduled for completion in 1941–42, the Navy had ordered another seventy-seven. Oil companies hoped to construct, at their own expense, pipelines from Texas to the East Coast (sixty-five tanker equivalents) and local distribution pipelines in the Northeast (fifteen tankers). Conservation offered further solutions. The American Automobile Association later estimated a possible 20 percent gasoline savings by carburetor adjustments, avoidance of jackrabbit starts, and lower speed limits. Morgenthau suggested taxing both cars and gasoline. The Oil Burner Institute said furnace tune-ups could save 20 to 30 percent of heating oil.11 In spite of the industry’s confidence, and the complaints of eastern congressmen and businesses about possible rationing, Ickes and Davies kept up a drumbeat of warnings. On 24 July 1941, two days before the freeze of Japanese assets, Ickes publicly demanded an immediate one-third reduction of gasoline use in sixteen eastern states as a “patriotic duty.”12

In the run-up to the dollar freeze order of 26 July 1941, other domestic rationales for denying oil to Japan had been debated in the administration. On 22 July Maxwell M. Hamilton, chief of the State Department’s Division of Far Eastern Affairs, suggested “proceeding with some finesse” in any press statement about oil by blaming it on “the defense needs of the United States.” But Roosevelt understood the regional oil economics and that there was plenty for defense. He paid no attention to Hamilton then or when Welles repeated the suggestion after the freeze.13 On 24 July, the same day as Ickes’s outburst, he personally told Nomura that public opinion strongly favored an oil embargo, that he had thus far persuaded the public against it in order to maintain peaceable relations. But due to Japan’s aggressions “he had now lost the basis of this argument” and hinted at an embargo. He instructed Admiral Stark, the chief of naval operations who was going to lunch with the Japanese ambassador, to tell Nomura “that it is rather difficult to make our people understand why we cut oil and gas at home and then let Japan have all she wants.” The president added, “Of course, we understand this, because Japan carries the oil in her own bottoms—and our shortage in the East is due not to lack of oil and gas at the refineries, but to our inability to transport it from the oil fields to points where needed.”14 Roosevelt was soon to ignore publicly his own astute observation.

That day, when FDR summoned the cabinet for the decision to freeze Japanese assets, he took the extraordinary step of telling the American public that there was an odious link between the predicted East Coast gasoline shortage and oil sales to Japan. While addressing a volunteer group for civil defense headed by Mayor Fiorello LaGuardia of New York—the city bearing the largest volume of risk for rationing of gasoline—FDR told the press,

You have been reading that the Secretary of the Interior, as Oil Administrator, is faced with the problem of not having enough gasoline to go around in the east coast, and how he is asking everybody to curtail their consumption of gasoline. All right. Now, I am—I might be called an American citizen living in Hyde Park, N.Y. And I say, “That’s a funny thing. Why am I asked to curtail my consumption of gasoline when I read in the papers that thousands of tons of gasoline are going out from Los Angeles—west coast—to Japan; and we are helping Japan in what looks like an act of aggression.”15

Roosevelt’s linking of Atlantic and Pacific supplies was a brazen political canard to guide public opinion and perhaps soothe Japanese anger. There was no conceivable possibility of satisfying East Coast needs with West Coast oil. Nevertheless, in the weeks following 26 July, as a relentless oil embargo by means of the dollar freeze descended on Japan, Ickes continued to insist, against the advice of government and private experts, against all remedies offered by the industry, against the findings of a senatorial investigating committee, and even against evidence that Britain did not need U.S. tankers, that an East Coast gasoline crisis was inevitable. The specious rationale of a shortage continued almost to the eve of Pearl Harbor: the United States could not spare California oil for Japan because it was scarce in New York (appendix 1).