The international economic fate of Japan had dangled by a silken thread for eighty years. Since its emergence as a trading nation in the 1860s, Japan had derived most of its earnings of dollars from the export of raw silk for fashionable women’s clothing. The prosperous trade had been an engine of Japanese growth and power. At its peak in 1929, sericulture afforded a livelihood to 2.2 million Japanese farm households. Raw silk exports, nearly all to the United States, enriched the nation’s coffers by $363 million that year. Imports of raw silk, nearly all from Japan, constituted America’s largest import by value and supplied the material for a great manufacturing industry. But Japan’s silk road to the United States had been pitted by dilemmas of low quality, high price, substitution, and shocks of fashion that exposed it to ruin time and again. With diligence and innovation in both countries, however, the silk trades weathered the threats and prospered. The Great Depression diminished but did not destroy the primacy of silk as a source of dollars. At the end of the 1930s, however, the business that was Japan’s dominant source of dollars faced an irrevocable collapse within a few years.1

A word about dollars. Before 1939 it mattered little where, outside the yen bloc, Japan exported its goods because the major currencies were convertible into dollars in foreign exchange markets (unlike the yen, an inconvertible currency that only Japan’s colonies and the occupied areas of China could use to buy Japanese goods). Until then, the British, French, and Dutch colonies of Asia and the Pacific, all of them large markets for Japanese manufactures, might pay in sterling, francs, or guilders, and China in silver, but Japan’s receipts were changeable into U.S. dollars, the currency it coveted for procuring metals, oil, and other strategic raw materials from the neutral United States. The outbreak of war in Europe forced the belligerent countries to impose exchange controls. Japanese exporters to them and their colonies were paid with blocked currencies, barred from conversion into dollars and spendable only for the products of the walled-in currency blocs, which had few of the strategic commodities Japan needed.

This had not been true in earlier days. Before 1914, in the heyday of the gold standard, Japan’s trade pattern was triangular. Surplus earnings from trade with the United States were spent in Europe, especially Britain, for steel, capital equipment, and warships, products in which the United States was not yet a principal competitor. In the interwar years, trade with the United States was more balanced, dominated by the two-way movements of raw silk and raw cotton, while foreign exchange markets continued to function adequately even though the international gold standard expired in the early 1930s. When the world crisis erupted in 1939 and free convertibility of major nondollar currencies came to an end, exporting to the United States (and to a small degree to other dollar-bloc territories—Canada, South America, and the Philippines) became crucial for financing Japan’s aggressive empire-building policy.

Newly emerging economies usually depend on exports of unique commodities, but none was so vulnerable to whims of the marketplace as Japanese raw silk. In the nineteenth century the Meiji oligarchy’s wish to shape a modern nation required exporting to pay for machinery and armaments. Inviting overseas investors into Japan was anathema for fear of foreign dominance or even colonization. But what commodities could Japan offer in return? It manufactured nothing of international value. The islands lacked minerals. Land and climate were unsuited for commercial plantations; the 15 percent of land that was arable yielded barely enough grains to feed the people. Yet Japanese farm families were hard working and dexterous at crafts. By harnessing their energy to raise specialty crops, nonperishable goods of high value that could be shipped across oceans, Japan paid its way in the world.

Raw silk was by far the most important Japanese export. Farmers raised silkworm cocoons throughout old Japan but especially in impoverished Nagano province, north of Tokyo. They planted mulberry trees on hillsides and field borders, clipped the tender green leaves, and scattered them onto bamboo trays to feed Bombyx mori L., the silkworm moth. A mature worm extruded a filament half a mile long to wrap itself into a cocoon the size and shape of an unshelled peanut. Haru Reischauer, wife of a later U.S. ambassador, wrote, “No one who has heard the sound will ever forget the low, all-night roar created by the munching of thousands of voracious silkworms in a Japanese mountain farmhouse.”2 When the insects finished spinning, the farmers heated the cocoons to kill the worms and sold the dried cocoons to filature plants, which unwound and twisted the strands into skeins of raw silk.

As the Japanese entered world trade they planted more and more land in fast-growing mulberry trees. Meiji authorities encouraged scientific sericulture. They recruited former samurai as commercial managers. From 1890, when good statistics were first available, to 1929, mulberry acreage rose 157 percent to 1.5 million acres, covering a remarkable 10 percent of the arable land. Chemical nitrogen fertilizer supplanted the manures of plants, animals, and humans. Summer and fall cocoon raising supplemented the spring crop. Government agencies and trade associations built sanitary cocoon warehouses, bred improved worms to spin more and better silk, and ruthlessly destroyed diseased worms. Cocoon productivity per acre of mulberry rose 271 percent in the four decades up to 1929. In the countryside hundreds of filature plants housed young women in dormitories, toiling to earn for their families and, as legend has it, for marriage dowries. At work they dropped cocoons into basins of hot water to loosen the natural sericin glue and unwound three, six, or more cocoons simultaneously, twisting the strands onto reels to form the multifilament yarn known as raw silk. Their skills improved with training. Soon reels powered by water wheels and engines replaced hand-turned reels. By 1929 a cocoon yielded 40 percent more silk than one of 1890.

Exports of raw silk commenced in the 1860s to France and Italy, where a worm disease had ravaged sericulture until Dr. Louis Pasteur found a cure. Haulers lugged skeins of raw silk down mountain trails to Yokohama. There, merchant companies inspected and packed them into “picul” bales of 132.3 pounds. Steamers freighted the bales to San Francisco, Seattle, or Vancouver, where speedy, super-clean trains highballed them to importing firms in New York, the warehousing and financing hub near the textile mills of Paterson, New Jersey, “the Lyons of America.” Exports surged from 6 million pounds in 1900 to 70 million in 1929. In the 1890s the United States surpassed France as the leading customer. At the turn of the century Japan surpassed China as the world’s dominant supplier. In the 1920s Japan supplied two-thirds of world commercial output. It had successfully monetized its first-class work force and second-class land into a foreign exchange generator that underwrote its destiny of fukoku kyōhei, “rich country, strong military.”

Japan’s success was due to an equally phenomenal growth of silk textile manufacturing in the United States, where wealthy and middle-class women hankered for stylish clothing. Before World War I the nation purchased 80 percent of Japan’s silk exports, during the war 90 percent, and in the late 1920s 95 percent. Raw silk was never subjected to tariffs because sericulture failed in the United States for lack of peasant labor. Instead, U.S. manufacturers developed unique machinery and marketing systems adaptable to capricious fashion fads. “Throwing” mills cleaned and twisted raw silk into fine yarn and dyed it. (Hollow silk filaments absorb colors thirstily.) Silk thread, stronger than steel wire of similar diameter, was prized for stitching clothing and boots. In the 1870s Swiss entrepreneurs established fabric weaving mills in New Jersey and Pennsylvania, where French weavers trained workers. Laying warp (lengthwise) threads on looms was an expensive hand-labor chore, whereas the filling (crosswise) threads were inserted by machine, so the mills wove “narrow goods” (ribbons) less than eighteen inches wide. Women ornamented their hair and hats with silk ribbons, their gowns with passémenterie fringes and tassels, and wore the wider ribbons as scarves and sashes. But only talented seamstresses could craft whole garments of narrow silk. In the 1880s improved looms began to weave bolts of “broad silk.” Shielded by tariffs, broad silk manufacture grew exponentially. In 1899, 76 percent of U.S. yardage was broad. The takeoff arrived at a crucial moment for Japan, which in the 1880s had practically exhausted its monetary reserve, primarily of silver. Without the broad silk boom in the United States it is unlikely that Japan could have purchased the British warships that sank the Chinese and Russian navies in the next two decades.

Women’s clothing always accounted for about 90 percent of U.S. demand. (Men wore silk neckties and suit linings, rarely silk shirts and socks.) Raw silk cost five times more than wool and twenty times more than raw cotton. Silk was more difficult to weave, and productivity was lower because of frequent breaks in naturally irregular silk yarn. Nevertheless, bolts of broad silk thirty and thirty-six inches wide, piece-dyed or printed, enabled ordinary seamstresses and home sewers to cut and stitch entire garments. The mills wove taffeta, a simple over-and-under pattern suited to mass production. Satin, an easy weave with a shiny finish from reflected light, ranked second. Ribbed fabrics rounded out the line. Velvets were consumed for furniture and drapes and some gowns. By 1920 only “fancies,” comprising 3 percent of consumption, were imported from Europe. Japanese silk “tissues,” as the term was translated, did not sell well in America due to poor quality and tariffs of 45 to 60 percent, except minor yardages of habutae, a low-grade homespun for lining suits and dresses.

Broad silk marketing grew into a huge business. Department stores, another American innovation, stocked rainbows of broad silks. A ready-made clothing industry blossomed into mass production. Garment factories at first produced standardized shirtwaists (blouses) of a few sizes and colors. Jewish immigrants in New York City opened “cutting up” shops to manufacture dresses, suits, and coats using electric cutting and sewing machinery. Improved broad silks forty-eight to fifty-four inches wide were ample enough to cut the body of a dress from one panel. Inexpensive ready-to-wear garments transformed Japanese silk into an article “for the masses, not the classes.”

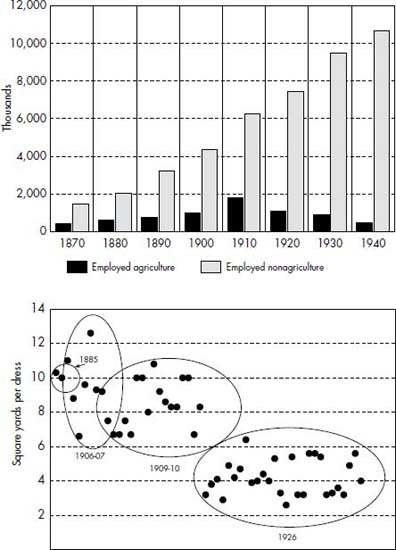

The silk boom rode the ups and downs of women’s fashions (chart 1). The creations of Paris couturiers illustrated in U.S. women’s magazines dictated elegance. In the 1880s stylish women wore floor-sweeping skirts of ten or fifteen yards circumference at the hem over corsets and layers of petticoats, covered with overskirts swagged like theater curtains, their outfits cut from ten square yards of fabric. Skirts billowed behind into fishtail trains or swooped over bustles jutting a foot or two to the rear. Cultural historians have debated the meaning of such extreme modes. Some claim that fashion emphasizes erogenous zones in cycles so that exaggeration of buttocks was merely a shift from a focus on breasts and waists in earlier decades. An average woman, however, owned one “grandmother” gown of silk taffeta, stiffly weighted by black metallic dye and frequently restyled, that rustled as she walked. In the 1890s straight-draping skirts of the “Gibson Girl” years “really used the material” in creases and folds that cascaded to the floor. In 1907 French designer Paul Poiret introduced supple messalines and other silks gaudily colored by brilliant aniline dyes from Germany. The hobble skirt and lampshade silhouettes of 1910–14 were also long and full, and two-piece outfits, suits, and sportswear of silk came into vogue.

During the prosperity of World War I American women demanded ever more silk for all occasions. Japan enjoyed a market bonanza in spite of the loss of French markets, shipping shortages, and labor and coal bottlenecks at U.S. weaving mills. Costly financing of raw silk shipments by British banks or by rapacious New York commission houses eased when the Federal Reserve system coaxed U.S. banks into low-cost “bankers acceptance” financing secured by silk bales as collateral. A fashion design industry took root in New York, promoting black and white fabrics until an American aniline industry sprang up to replace German dyes. American women appreciated the wartime fashions, skimpier to save fabric, for their informality and comfort.

CHART 1 U.S. Women Employed, 1870–1940, and Samples of Dresses in Sewing Pattern Books by Square Yards of Fabric Required

Department of Commerce, U.S. Women Employed, Historical Statistics of the United States on CD-ROM, Part D. Yardage from a random sampling of fifty-six patterns in The Deliniator: A Journal of Fashion, Culture and Fine Art (London, Butterick), Designer and the Woman’s Magazine (New York: Designer Publications), and American Modiste, various dates.

Price instability was a perennial risk for operations in both countries. Raw silk prices were quoted for a benchmark grade, with other grades at fixed premiums or discounts. Demand and wartime inflation drove raw silk far above its normal price of three to four dollars per pound to eight dollars in 1919 and a spectacular peak of seventeen dollars in January 1920. U.S. traders blamed the giddy prices on the Yokohama Silk Bourse, supposedly a hedge market but in fact a casino for Japanese speculators with inside information; U.S. firms were amateurs, lacking knowledge of the cocoon crop or whether filatures were hoarding or dumping, until bales came “into sight” at Yokohama. In the postwar recession of 1921 raw silk prices crashed to prewar levels, bankrupting many overstocked U.S. firms. Prices stabilized at six to seven dollars per pound except for a spike after the Tokyo earthquake of 1923. A gradual decline set in after 1925. Nevertheless, silk operations in both countries enjoyed a decade of prosperity, helped by a legitimate New York Silk Exchange established in 1928 for price hedging. The silk wealth was instrumental in financing Japan’s industrialization and building a national reserve of gold.

Despite general prosperity, silk faced dangerous challenges. In a fashion revolution, women of the Roaring Twenties abandoned traditional shoe-length skirts for short frocks, most famously the “little black dress” of designer Coco Chanel. Hemlines rose to the knee in 1923, dipped briefly, then soared from 1926 to 1929. Flappers of the Jazz Age flaunted skirts inches above their rouged knees. Dresses were scanty above and below the waist and worn over light slips. A fashionable lady wore a mere two square yards of fabric versus six or eight worn by her mother and ten by her grandmother. The Zeitgeist theory of fashion holds that the skimpy outfits reflected the liberation of women, sexually and politically. A more common theory says simply that fashions move in cycles, with exaggeration in one direction soon followed by an extreme in another.

Briefer styles might have punctured Japan’s silk boom but for revolutions in American lifestyle. Urban incomes rose and married women entered the workforce en masse. In the 1920s, twice as many women worked outside the home as in 1900. Women drove cars, patronized sporting events, speakeasies, and tea dances, and they bought outfits for active lifestyles. Ready-to-wear clothing, scarcely an industry before 1900, soared to 163 million dresses in 1929, four units per adult woman, worth $810 million wholesale. Manufacturers also cut $642 million of suits, coats, and undergarments. Of course, only a fraction of the garments were of silk or silk blended with other fibers. (The United States imported almost no clothing because of high tariffs, and aside from a minor vogue for kimonos as beach coverups, Japanese designs were unpopular.)

Both countries’ silk industries had to cope with quality problems. Raw silk was naturally flawed: tangles, off color, cocoon debris, and, most distressingly, bad “running quality” due to random thicknesses of yarns. Silkworm extrusions are 30 percent thicker in the middle than at the ends. Filature girls could not consistently blend away the variations as they reeled several strands together. Machinery stoppages during throwing and weaving to knot the broken ends together exacerbated the problem. Dressmakers knew how to disguise imperfections in heavy taffeta, but when unskilled factory hands sewed sheer goods, streaks and bumps showed up in the garments. Mill owners demanded that the Japanese adopt scientific quality testing. Japanese merchants insisted that the trained eye of the inspector in Yokohama could best sort raw skeins into dozens of grades, from elegant Crack Double Extra down to shabby Number One, which yielded, respectively, one visible flaw per linear foot of fabric versus one flaw per inch. (Lowest grade Number Two silk went to the Japanese domestic market.) U.S. mills also lobbied for branding by the filatures. Japanese exporters labeled their bales with exotic “chops” (logos) such as “Peach,” “Five Girls,” and “Lobster,” but in reality they continued to blend silk from dozens of filatures of varying quality. Negotiating teams sailed back and forth across the Pacific to no avail. A partial solution emerged when U.S. throwsters adopted a French technique of twisting silk thread seventy-five turns to the inch into coiled, springy yarns for weaving crêpe Georgette and crêpe de Chine. Crêpe fabrics were comfortably stretchy with a pebbled appearance that hid flaws. In the 1920s crêpes came to dominate stylish ready-made clothing. Japan welcomed the 5 to 12 percent of extra silk in hard-twisted yarn.

Japanese silk weathered the fashion challenges because women bought silk outfits for all occasions, more than offsetting scantier yardage per garment. Raw silk swelled into America’s largest commodity import by value, feeding one of its largest manufacturing industries. In the peak years of the 1920s raw silk bales (95 percent to America) comprised 38 percent of Japan’s global exports and an even larger 45 percent of net “domestic exports,” defined as exports minus foreign materials contained in them. Including silk textiles and filature waste, silk in all forms comprised a stunning 54 percent of Japan’s domestic exports to the world. The U.S. silk craze contributed hugely to financing earthquake reconstruction as well as the electrification and industrialization of Japan.

Broad silk, however, faced another and more ominous threat: competition from rayon. Artificial silk—“art silk,” as it was labeled until the Federal Trade Commission put a stop to it—had been a perennial quest of chemists. Since the 1890s low-quality rayon had been manufactured from wood pulp. When dissolved in a chemical slurry and squirted through nozzles, it hardened into strands resembling silkworm extrusions. Rayon yarn was uniform, shiny, and took dyes well. Although it lacked the strength and resilience of silk, it could be blended with stronger fibers. In the 1920s viscose rayon, a superior variety, came into production in Great Britain and soon in all industrial countries. (Japan itself became a major rayon producer in the 1930s.) Flawless rayon textiles could be woven on high-volume cotton looms. The price of rayon, once higher than silk, fell steadily, to $1.50 per pound versus $6 for thrown silk. Rayon gained niches at first in inexpensive underthings and casual garments, but it was intrusion into elegant outerwear that alarmed silk men. By the end of the decade U.S. rayon production was 50 percent greater by weight than raw silk imports. Nevertheless, U.S. silk consumption held its own as prosperity rolled on, soaring to a peak of eighty-seven million pounds in 1929, 70 percent above the early 1920s.

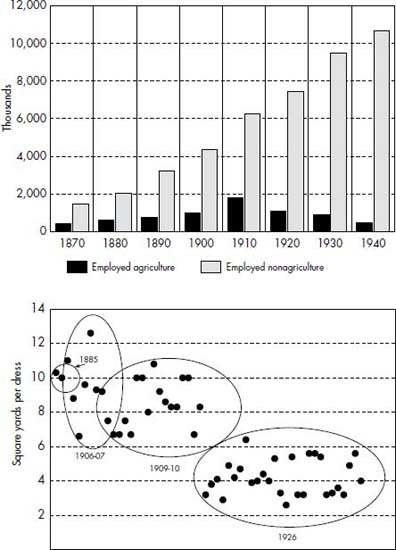

The world Depression that struck the United States in late 1929 (and Japan in 1927) destroyed the broad silk industry. U.S. incomes shrank drastically. Demand for luxury clothing plunged. Women shifted down market to rayon or cotton garments, or did without. The collapse was devastating for Japan. U.S. broad silk production shriveled from 47 million pounds in 1929 to 6 million in 1939, while rayon fabrics surged from 29 to 335 million pounds (chart 2). Silk clothing, the glory of fashionable women throughout history, virtually disappeared from store racks. Rarely has a large industry imploded so suddenly and completely. Japanese raw silk collapsed to $1.27 per pound in 1934, hovered around $1.50 to $2.00 the next few years, and inched above $3.00 only in 1939–41. One and a half million Japanese households still tried to support themselves, at least in part, by sericulture, but destitution and malnutrition stalked rural Japan, fertile breeding ground for fanatical nationalists recruiting boys for the army.

One last miracle, however, rescued Japanese sericulture for a final decade: the full-fashioned silk stocking. Modes that hid female legs throughout history owed more to ugly stockings than to prudery. Only stockings of a knitted fabric, sheer and stretchy, flattered the leg. (In knitting mills, yarns are looped around one another rather than criss-crossed as in weaving.) But machine-knitted stockings around the turn of the century were straight, ill-fitting tubes, and rayon hosiery, baggy at the knee and glossy, was relegated to children’s wear and bargain counters. Only the rich could afford hand-sewn silk hosiery. “Silk stocking district” became a metaphor for wealth. Most women preferred long skirts and high-buttoned shoes.

CHART 2 U.S. Production, Broad Silk vs. Silk Hosiery, 1919–1939

Broad all-silk fabric, million pounds

Broad all-silk fabric, million pounds

Full-fashion hosiery, dozen pair (millions)

Full-fashion hosiery, dozen pair (millions)

Department of Commerce, Census of Manufactures (for silk and related goods), 1919–39.

Silk yarn was ideal for knitting stockings. It could stretch 20 percent and “kick back” to original length immediately. The vogue for short skirts coincided with the development of knitting machinery adapted to fine yarns for mass production of long silk stockings that clung snugly to legs and feet yet yielded at knees and ankles. Factory workers knitted the boot (leg) on a legger machine as a trapezoid of fabric, narrowing from wide thigh to slender ankle. Skilled workers machine-stitched the boot panel into a tapered knee-high cylinder about twenty inches long and joined it to the foot, which was knitted on a footer machine of cotton for durability. Customers preferred sheer stockings, dyed in flesh tones with trade names like nude, peach, and suntan, to complement peek-a-boo and slit skirts and knee-high hemlines. A dark seam sewn up the back of the leg was considered alluring; men glanced admiringly as women leaned over to straighten them. Women wore pumps with vampish high heels or sandals. Flappers rolled stockings down to the knee to show a flash of thigh. Some fashion theorists claimed that legs had become the “pathway” to previously taboo erogenous zones.

By the end of the 1920s, forty-two-gauge machines knitted four- and five-thread semitransparent “chiffon” stockings twenty-four inches long.3 Opaques of eight to fourteen threads were sold as “service weights” to elderly ladies and female manual workers. Knitting speed increased, from forty courses per minute to seventy. Strong firms such as Berkshire, Cannon, Gotham, Holeproof, and Hollywood built mills in Pennsylvania, where coal miners’ wives and daughters toiled cheaply, and later in the rural South. Hosiery factories multiplied from 92 in 1919 to 263, knitting branded, advertised stockings. The business was a far cry from the undercapitalized, unintegrated silk textile and garment industries. Full-fashioned hosiery output rose from 76 million pair in 1919, the first year reported by the U.S. Census of Manufactures, to 360 million in 1929, equivalent to 8.7 pair per adult woman. Hosiery mills consumed about 30 percent of raw silk imports versus 10 to 15 percent a decade earlier. Silk hosiery provided Japan a welcome $80 million per year of extra dollar inflows.

The depressed 1930s were surprisingly good years for silk stockings. Demand rose while other luxury markets slumped. Hollywood glamorized movie stars’ silken legs. Although hemlines dropped below midcalf in 1931 (another example of Zeitgeist?), they rose again to the knee after economic recovery began in 1934. The hosiery industry struggled to overcome raw silk irregularities that caused unsightly flaws. Japanese exporting firms culled the best raw grades to meet standards imposed by the New York Silk Exchange, and throwsters improved their techniques, but the two most nagging problems were finally solved by knitting innovations. Irregular yarn thickness showed up as dark circular rings in the boot. In 1934 machines that drew alternately from three spools of yarn dissipated the ring to invisibility. In 1937 an all-in-one machine knitted hosiery entirely of silk, eliminating the ugly lower seam where foot and boot joined and lowering costs by knitting twenty-four stockings simultaneously. Since women no longer had to inspect for flaws at the hosiery counter, stockings were packaged in sealed cellophane bags. But the fragility problem remained. Sheer stockings tore or snagged into unsightly “ladder” runs. There were reweaving shops, but usually a snagged stocking was ruined forever. Some stores sold three to a box to provide a spare. Mills improved durability by knitting springy crêpe-twisted yarns, which also lent a fashionably dull finish. Elasticized welts (upper thigh portions) and longer stockings that rose close to the girdle’s connector tabs reduced strains on the fabric. Manufacturers offered thigh-highs, twenty-eight to thirty-three inches long with proportionally tapered boots. Nevertheless, sheer hosiery was and remains fragile.

American women of the 1930s came to regard sheer hosiery as a necessity. Retail prices fell to a range of 79 cents to $1.35 per pair, due largely to low wages and, especially, productivity gains rather than to cheaper Japanese silk because a pair contained only 15 to 20 cents of raw silk. Hosiery counters contributed to 10 percent of department store sales at lush 30 percent profit margins. Chain stores and drug stores sold bargain stockings. Working girls skipped lunches to afford them. Wives of the unemployed peddled hosiery door to door. By 1939, two- to four-thread ultrasheers held 80 percent of the market. Women bought an average of eleven pairs of silk stockings in 1939, their most frequently purchased item of apparel. Retail hosiery prices in the Depression were equivalent to about $10 in year-2000 dollars, adjusted for price inflation, or $25 adjusted for wage levels, far more expensive than excellent $5 nylon-spandex pantyhose of the twenty-first century.

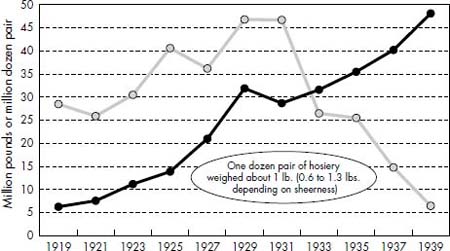

In spite of the vogue for silk stockings, Japanese sericulture suffered severely in the early and mid-1930s. Raw silk exports declined 30 percent by weight from peak 1920s years, and 75 percent in dollar value. U.S. imports slumped from $427 million in 1929 to a low of $72 million in 1934, then stagnated at just under $100 million for the next five years as rayon destroyed the broad fabric market (chart 3). U.S. hosiery mill takings dropped briefly in the Depression then recovered to thirty-three million pounds of raw silk in 1936 and thirty-eight million in 1939. By 1939 American hosiery, nearly all of it women’s full-fashioned, accounted for 81 percent of U.S. silk consumption—90 percent in 1941—and 60 percent of total world silk consumption. In July 1937 a Japanese commission sought to steady the markets under a Raw Silk Price Stabilization Law.4 In 1939 the market turned more favorable for Japan. The U.S. economy improved, hemlines rose—skirts were the shortest since 1929 (Zeitgeist again?)—and hosiery demand surged. As mills fearful of war disruptions stockpiled raw silk, Japanese exports rose to $128 million. In the fourth quarter of 1939, as war broke out in Europe, raw silk tipped up to $4.00 per pound in early 1940 before settling back to around $3.00, still the highest price in a decade. The Japanese government Silk Commission felt confident enough in July to buy buffer stocks to ensure a floor price of $2.55 per pound.5 During the price boomlet Tokyo even encouraged firms to buy from filatures in occupied Shanghai and Canton for local currency and reexport for dollars, but in September 1940 it halted the practice.6 Despite losing its minor market in Europe, the Japanese silk trade had apparently weathered the war crisis.

CHART 3 U.S. Imports from Japan, Raw Silk vs. Other, 1935–1941

Department of Commerce, Foreign Commerce and Navigation of the United States, 1936–42.

The recovery, however, petered out. U.S. hosiery mill takings in 1940 dropped to 28 million pounds, the lowest since 1934. Two-thirds of the drop was due to switching to cotton and rayon for feet and welts, a reaction to the higher price of silk. Shipping shortages diverted deliveries from the Panama–New York route to the more expensive rail haul from West Coast ports. Japanese raw silk exports sagged to $104 million. As the price retreated, the Tokyo government bought 15.7 million pounds at the Japanese ports to support the market, a failed experiment it ended in January 1941.7 But the slump was just a twitch compared to the market disaster that loomed ahead. The fifteenth of May 1939 was Nylon Day at the New York Worlds Fair. It was a day of disaster for Japan.