The drastic shriveling of income from raw silk in the 1930s prodded Japanese businesses and government to explore possibilities of earning dollars by exporting other products to the United States (and to other dollar countries, although their markets were relatively inconsequential). In the 1930s Japan launched a drive to sell processed and manufactured goods wherever it could.1 Raw silk historically had enjoyed a privileged status in U.S. markets. It was the raw material of a major industry that employed hundreds of thousands and provided articles of high-end consumer satisfaction that did not compete seriously with American cotton and rayon textiles (and not at all after the collapse of broad silk in the 1930s). Thus it encountered no restrictive tariffs or quotas. Conversely, most other products Japan attempted to sell in the United States attracted the hostility of U.S. industrial competitors. They lobbied Congress to legislate protective tariff rates and the independent Tariff Commission that recommended higher duties whenever Japan appeared to score gains by dumping below cost. Their trade associations demanded negotiations of import quotas with Japanese firms that were fearful of even higher tariffs if they did not acquiesce. Although such barriers were not erected as a matter of U.S. policy to punish Japan’s aggressions in Asia, an unintended result was to encourage Japanese expansionists who pressed for economic advantage by military conquests.

During the Depression the world fragmented into narrow trade and finance blocs. Germany and the Soviet Union negotiated bilateral deals with smaller neighbors in Eastern Europe, in effect bartering. The British Empire withdrew into semi-isolation under the Ottawa agreements of 1932, which enforced preferential trade access among members of the sterling area. Other industrial countries raised tariffs exorbitantly. The U.S. Smoot-Hawley Tariff Act (known by the names of Republican sponsors Sen. Reed Smoot of Utah and Rep. Willis C. Hawley of Oregon and signed by President Herbert Hoover in 1930) imposed historically high duties on imports of almost every product grown or made in the United States. Although U.S. tariff policy did not overtly discriminate among nations, that is, identical products incurred the same duty regardless of country of origin, the complex rates of Smoot-Hawley in fact discriminated ferociously against processed and manufactured articles made uniquely by Japan.

As noted previously, until the autumn of 1939 most markets outside the yen bloc were equally desirable to Japan because foreign currencies earned in trade were convertible each to the other. Upon the outbreak of war on 3 September 1939, however, Great Britain erected a fence of controls around the “fortified sterling area.” Japanese firms selling to customary markets in India, Australia, New Zealand, Malaya, and British Africa thereafter received payment in “blocked sterling” in London bank accounts. Without special permission, they or fellow Japanese firms could spend the money only within the sterling bloc, which, being at war, had few strategic commodities to offer after supplying Britain’s needs. The colonial governors of the Dutch East Indies and French Indochina, isolated from their mother countries, also imposed exchange controls. Only the United States freely sold metals, machine tools, and large volumes of crude and refined petroleum. With other currencies inconvertible, exporting to the United States became an acute challenge for Japan, just as nylon began to pinch off its prime source of dollars. If Japan could not sell manufactures to Americans it would have to liquidate its monetary gold or do without strategic imports.

Japan normally exported to the United States about $50 million per year of nonsilk goods, worth only 40 to 50 percent of its raw silk sales to America. The array of such articles was extraordinarily diverse. The U.S. Tariff Commission calculated that in 1940 Japan sold to the United States 138 different products (as defined in tariff schedules) worth at least $50,000 each, another 85 worth between $25,000 and $50,000, and many others of lesser value. Only about a dozen products, however, amounted to $1 million or more per year.2 Most Japanese offerings clung to market toeholds, hemmed in by tariffs and quotas or in some cases by inferior quality. Japan was unable to sell to America its rayon textiles or the mass-produced footwear, bicycles, and other consumer wares it marketed throughout East Asia. Industrial machinery and chemical firms could not compete for U.S. orders. Japanese businesses, instead, exported more readily marketable low-value specialty wares, hoping not to arouse the ire of U.S. competitors and provoke a backlash of antidumping actions and quotas. They probed for niches of two varieties: semiluxury items of good quality in which Japan had advantages of low-cost labor, management skills, or local materials, and consumer specialties so cheap that U.S. producers could not or would not match their prices. Japan’s campaign to diversify dollar earnings failed, however, primarily because of deliberate U.S. barriers.

In the 1930s Japan pinned its hopes for earning dollars on its largest export industry, cotton textiles. Since Meiji times spinning and weaving mills around Osaka had supplied Japanese home demand. With modern textile machinery from abroad, and later designed in Japan, their durable, low-priced fabrics and diligent salesmanship won markets in the underdeveloped world, displacing the output of the British Lancashire district. Japanese workers, mostly young and female, tended fewer spindles or looms and lagged behind in productivity, but they earned one-tenth of Western wages and benefits. Mill labor comprised only 20 to 25 percent of fabric cost, however, whereas imported raw cotton made up 50 to 60 percent. (The remainder included freight, supplies, and capital.) Japan grew no cotton, and the yen bloc grew too little to export. Japanese mills purchased American raw cotton, desirable for its longer staples (fibers), which provided strength, for about half their needs. For the rest they blended cheap short-staple cotton from India.

By the late 1920s the textile industry employed nearly three million, 40 percent of all Japanese manufacturing workers. A slump had forced small firms to rationalize into efficient giant syndicates that bought raw cotton in quantity when bargains appeared and mastered the technology of blending all grades. Hedging on the New York Cotton Exchange afforded protection against volatile price and currency fluctuations, and crucial for Japan, the exchange’s low-cash-margin hedge contracts did not tie up scarce dollars. In the 1930s Japan surged to second largest world producer of cotton textiles, behind the United States. Half its production was sold abroad, the other half retained for the domestic market. In December 1931 exporters got a lift from a yen devaluation. In 1933 Japan surpassed Britain as the largest cotton textile exporter. By 1935, however, the devaluation boost had played out while U.S. raw cotton prices rising from Depression lows squeezed profits. Japanese industrialists turned their eyes to the billion-dollar U.S. fabric market.3

Americans consumed an enormous quantity of cotton goods, some nine billion square yards in the late 1930s (seventy yards per person), 98 percent of it woven domestically. Because of heavy-handed lobbying in Washington, mills were sheltered by tariffs and other import protections. The Smoot-Hawley Tariff Act extended an already complicated array of duties. In general, the finer the weave, the higher the duty; only a few elegant European and English fabrics surmounted the tariff wall. The duties on medium-grade cloth, Japan’s specialty, were 38 to 42 percent. Because half the duty was, in effect, imposed on foreign raw cotton, the burden on value added in Japan was twice as high, about 80 percent.4

During the early New Deal era the National Industrial Recovery Act (NIRA) restricted domestic textile competition in hopes of raising both factory wages and the ruinously low prices received by cotton farmers. It levied a processing tax on U.S. factory output but not on imported textiles. Powerful Japanese trading companies, including Mitsui and Mitsubishi, spotted an opportunity. In late 1934 they began massive shipments of broad cotton cloth, thirty to fifty count (threads per inch) bleached pure white, into the New York textile market. The fabrics, woven of finer yarns, were 15 percent lighter than American goods, excellent for inexpensive women’s nightgowns, children’s and women’s underwear, and handkerchiefs, items not subject to rough wear and tear. Using forty-four- and fifty-two-inch-wide Japanese bolts, the factories cut nightgowns across the width with less wastage than when they cut thirty-six-inch U.S. cloth lengthwise. Typical Japanese fabrics entering at 5.7 cents per square yard including duty emerged as nightgowns sold for 25 to 39 cents in bargain basements and five-and-dime stores. Heavier 10-cents-per-yard U.S. goods wound up in nightgowns costing 49 to 79 cents and sold in upscale stores. The Japanese also sold lightweight “print cloth” fabrics dyed in light hues and ready for printing of patterns. Cotton textile exports to the United States, previously a minuscule one million square yards, jumped in 1934 to seven million and in 1935 to thirty-six million square yards, the latter barely half of 1 percent of the U.S. cotton fabric market but 12.6 percent of the grades in which it competed.

U.S. mill operators howled in protest. They made common cause with activists advocating boycotts because of Japanese treatment of the Chinese. They drowned out the voices of farmers’ advocates who well understood that Japan bought 32 percent of U.S. raw cotton exports in the mid-1930s, in fact, 16 percent of the entire U.S. crop, especially from south Texas and other impoverished regions far from the weaving mills of the Carolinas. The political uproar dampened any impulse the administration might have had to negotiate with Japan the sort of treaty authorized by the Reciprocal Trade Act of 1934. Such treaties empowered the president to cut tariff rates on a country’s products by up to half, and to extend the cuts to other countries under the “most favored nation” doctrine. (Only a few such treaties were negotiated before World War II, none with Japan or with countries from which treaties could have benefited Japan.) A “scientific” study by the U.S. Tariff Commission determined that Japanese costs of the popular textile grades were below those of domestic mills and recommended tariff increases of 10 to 14 percentage points. Roosevelt so ordered in 1936.

The action did not slow Japan’s market invasion. By vigorous salesmanship and processing low-cost cotton purchased earlier, and despite tougher competition after the Supreme Court killed the NIRA and the processing tax, Japanese exports to America doubled in 1936 to 77 million square yards. Ultimately the textile onslaught was curbed by a “gentlemen’s agreement” crafted by a consortium of U.S. mill operators with government blessing. Claudius T. Murchison, president of the Cotton Textile Institute and a former senior officer in the Commerce Department, led a five-man team across the Pacific to negotiate with the Japanese textile cartel. The parties agreed to a quota allowing doubled imports of 155 million yards in 1937 but a reduced quota of 100 million in 1938, which was subsequently extended into 1939 and 1940. Acquiescence of the Osaka exporters was no doubt due to the generous concession—a measly thirty-six-million-yard quota had been rumored—and to anticipation that Tokyo would soon restrict textile production in order to shift labor, machinery, and foreign exchange to war needs.5

Accepting quotas on basic cloth but hungry for hard currency, Japan turned to higher value labor-intensive goods, hoping to wring more than the 4 cents per square yard (before duty) it received from processing imported raw cotton into standard cloth. Japanese velveteen, a shoddy imitation velvet suitable only for bedroom slippers, picture frames, and jewelry box linings because its pile shed when rubbed, sold for 15 cents per yard. Japan supplied 40 percent of the U.S. demand and 100 percent of the very lowest quality velveteen. For upscale customers Japan sold up to $1 million a year of decorative table-top wares at 45 cents per yard or more: damask table cloths, napkins, place mats, and “Japanese blue print” table runners. Demand firmed when the war halted British competition. Cotton fishing nets were another labor-intensive Japanese specialty. On the other hand, Japan made no headway in 50 percent–dutied knitted gloves and socks or in hemmed sheets and towels. “Hit or miss” rag floor rugs were worth eight or nine cents a square yard but, hammered by a 75 percent tariff, brought in less than half a million dollars per year. At the extreme downscale end, Japan exported penny-a-yard bundles of torn-up kimonos and underwear, used as wiping rags for machines and locomotives. The volume, an astonishing thirty million pounds in 1937, was twice the weight of all new textiles exported to America. For reasons unknown, shipments ended in1940.

What did Japan gain from its cotton textile push into the United States? Not much. Bleach and print cloth sales worth $3 million in 1935 provoked tariff and quota retaliation. Under the gentlemen’s agreement Japan sold $11 million worth in 1937, even though cloth prices dropped one cent per yard during the U.S. recession. Thereafter it shipped no more than 64 percent of its lowered quota. From 1938 to1941 Japan’s share of bleached and print cloth demand stalled at 5 percent of the market, earning $6 million annually. Higher-value specialties rarely exceeded half a million dollars each. Textile sales campaigns in other dollar countries met with little success outside Argentina and Chile. Canada, tied to British imperial preference, remained loyal to Lancashire. In the tropical American republics and in the Caribbean and the Philippines the United States held a relationship edge in exporting textiles because it bought their coffee, sugar, and bananas and Japan did not. Given that raw cotton constituted 50 to 60 percent of the cost of plain cloth (but much less for specialties) and that Japan necessarily bought American raw cotton for strength, the two-way cotton trade resulted in a net deficit in dollars.

After the outbreak of war with China, Tokyo converted textile labor and factories to war uses. It restricted raw cotton imports to the quantities needed to weave fabrics for export under the so-called link system, soon rendered more stringent by limiting raw cotton intake to cloth sold strictly for hard currency. Japanese consumers, accustomed to a plentiful fifty square yards of cotton textiles per capita, had to make do with shabby rayon staple cloth. Cotton fabric exports continued to earn some nondollar hard currencies, but Japan spent more U.S. dollars for raw cotton than it earned from link trade. The futility was painfully evident in 1940. Japan sold $8 million of cotton textiles to the United States but spent $30 million for American raw cotton. Although far below the pre–China war purchases of $90 to $100 million (due to link restrictions, and switching to more Indian cotton, and to some Brazilian payable in dollars), the total dollar outlay far exceeded textile sales to the dollar area. The proud cotton textile industry, bellwether of Japan’s surge into world industrial prominence, had become a burden the nation could ill afford.6

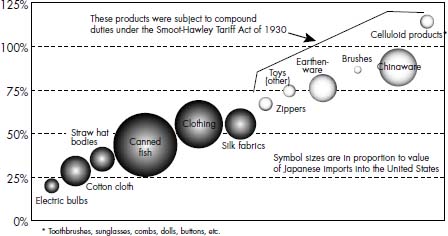

The decaying fortunes of silk and cotton energized Japanese business and government to promote other dollar-earning exports, with mixed but usually disappointing results. Raw silk and all textiles (including minor yardages of rayon and wool) together comprised 75 percent of sales to the United States. The other 25 percent consisted of a variety of wares worth $40 million per year on average, a useful sum exceeding half the value of empire gold production as well as a beacon of hope for diversification and commercial survival. The products, though individually small earners, required almost no foreign raw materials and gave employment to hundreds of thousands of Japanese. Modest successes attended sales of a few traditional articles upgraded by modern processing and the exploitation of niche markets for premium seafood, plant extracts, ceramic tablewares, and hat-making materials that did not compete directly with American producers. Tariffs of 20 to 50 percent were relatively benign for that era. By 1940 such products had gained or at least maintained U.S. markets, and the outlooks were promising. On the other hand, Japan fared poorly in expanding exports to America of small industrial components like zippers and miniature electric light bulbs because of terrible quality and of extremely cheap plastic novelties for adults and children that could not surmount punitive duties of 100 percent and higher. By 1940 these once-promising exports had shriveled nearly to zero.

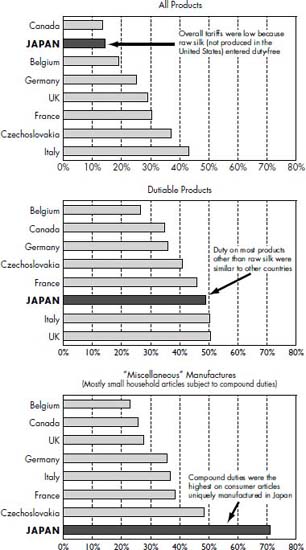

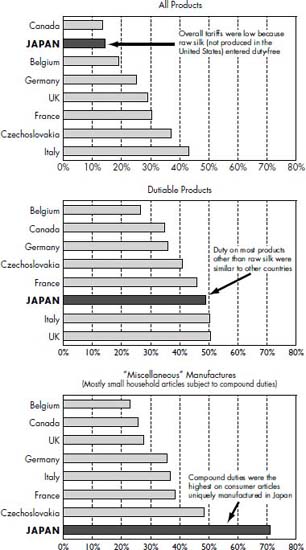

At first glance U.S. tariff schedules did not appear to discriminate (chart 4). In 1935 Japanese products were subject to an average of 14.3 percent duty, compared with 30 percent average on products of the seven most important European industrial countries, because raw silk entered duty-free. Japan’s average burden on dutiable articles (that is, everything except raw silk) at 49 percent was not much worse than the 44 percent average on dutiable European articles and slightly less than on those from Britain, the largest supplier of manufactures to the United States. Japan was hugely disadvantaged, however, by duties levied on “Miscellaneous products,” one of the ten broad product categories in U.S. tariff schedules, mostly small consumer and household novelties. The average charge of 71 percent against Japan was far higher than against European and British miscellaneous products that paid an average of 43 percent. Only Switzerland’s highly engineered, high-priced goods were close, at 65 percent duty (chart 5).7

CHART 4 U.S. Tariff Rates on Imports from Eight Industrial Countries, 1935 (ad Valorem Equivalent, Percentage of Value)

Tariff Commission, Computed Duties and Equivalent ad Valorem Rates.

CHART 5 U.S. Tariff Rates on Selected Japanese Imports, 1935

Tariff Commission, Computed Duties and Equivalent ad Valorem Rates.

Japan was the principal supplier to the United States of native plant and forest products worth, in total, $10 to $12 million per year. Green tea had once been Japan’s largest export, but it had fallen victim to changes in consumer preference. In the 1870s and 1880s tea shipments of around $5 million per year had constituted 15 to 25 percent of Japan’s meager exports, increasingly sold to the United States, where green tea (and later delicate oolong from Formosa) was popular. Both governments enacted purity laws to prevent the adulteration that plagued Chinese green tea. In the 1890s, however, the hearty black tea of India and Ceylon (from the same plant but fermented by a different process) won over English and European consumers. Americans remained loyal to the delicate Japanese brew, perhaps because they drank coffee prodigiously and relished a milder cup of tea at supper, green tea having one-fourth the caffeine of coffee and half that of black tea. After the turn of the century two lifestyle changes persuaded Americans to drink black tea: tea bags for convenience and iced tea for hot weather. Subtle green tea was too delicate for either purpose. Sales plummeted. In the 1920s Japanese advertising promoting Vitamin C in green tea came to naught. By 1940 Japan’s remaining $3 million in tea sales, mostly for oriental restaurants, constituted a mere 2 percent of its exports to the United States.8

Japanese plant extracts for U.S. industry also faced adverse conditions in the 1930s. Menthol, a peppermint aromatic used for medicines and flavored cigarettes such as Kool brand, struggled against competition from synthetic oil of citronella made from a tropical grass. Agar-agar, a gelatin extracted from Japanese seaweed for jellies and medicines, could be replaced by synthetic gelatins. Natural camphor from Formosa had been largely displaced in plastics manufacture by synthetic camphor (see below). Exports of pyrethrum flowers, the dried heads of a chrysanthemum species used in insecticides for U.S. tobacco and other crops, had been worth $2 million per year but slipped to $0.4 million by 1940 in futile competition against a more potent variety from Kenya, and synthetic poisons for household spray guns. Japan also eked out tiny sales of creosote, a coal oil for preserving wood, through freight advantages to the West Coast, and of lily bulbs and farm-bred mink pelts.9

Japan’s brightest prospect appeared to lie in high-value marine products. The Japanese fishery, the world’s largest, employed 1.4 million workers full and part time, mostly aboard three hundred thousand small boats in coastal and empire waters. They harvested four million tons worth $200 million per year, primarily sardines and other small fry for food, cooking oil, and fertilizer. Large motor vessels netted the most valuable 5 percent of the catch favored by Americans, from distant waters of Siberia, the North Pacific, and even the North Atlantic. Fishing consumed only a little foreign exchange for fuel oil, hemp for nets, and tin-plated steel canning sheet. When Tokyo rationed fuel oil after 1937, it treated the deep-sea fishery more liberally than inshore fishing. By the end of the 1930s, as U.S. incomes rose and seafood prices firmed when foreign competition disappeared due to war, Japan delivered $8 to $9 million in ocean products to the United States, second in dollar trade earnings only to silk.

Americans had grown fond of king crabs from northern waters, and Japan provided 80 percent of the U.S. supply. Japanese fishermen trapped, deshelled, cooked, and canned the crabs aboard factory vessels, or at shore stations in Russian Kamchatka, for sale mostly to America. King crab was a pricey delicacy at 36 cents per pound wholesale, so the 15 percent duty was no impediment, nor was tin plate at 3.5 cents per pound once Japan became self-sufficient after 1936. The tariff served no protective purpose because American crabbers caught different-tasting blue and Dungeness crabs, packed in unsealed tins too perishable for inland sales. Japanese appeals failed to reduce the tariff (which was, oddly, increased to 22.5 percent in September 1941 after all trade had ceased). Nevertheless, crabmeat sales to America doubled in the 1930s to more than ten million pounds, yielding Japan nearly $4 million per year in 1939 and 1940. Further growth was likely as the U.S. economy strengthened and Russian competition vanished.

U.S. consumers took a liking to canned tuna fish in the 1920s. Demand grew fivefold from 1923 to 1940. In 1932 Japan’s deep-sea fishery began delivering to the United States. By the end of the decade it supplied 60 to 75 percent of the light-meat albacore, which constituted the most lucrative 10 percent of the U.S. tuna market. Albacore canned in cottonseed oil, at 16 to19 cents per pound wholesale, was a semiluxury preferred by upscale consumers. Lower-income Americans and the Japanese themselves ate dark bluefin tuna. During the Depression complaints by U.S. fishermen led to a tariff of 45 percent. Japanese attempts to negotiate a “voluntary” quota in lieu of the tariff failed. The always-erratic tuna catch yielded Japan about $1.5 million per year, including 20 percent sold as inexpensive fresh and frozen tuna, but with demand rising the canned tuna market looked favorable for growth.

Japan delivered other premium seafood to America. At Boston, Japanese vessels landed frozen Atlantic swordfish, a contra-seasonal delicacy subjected to a duty increase in 1936. On the Pacific Coast scallops and other shellfish, and in Hawaii canned salmon, entered duty-free. Canned clams, however, encountered a lawsuit in 1934 that led to a very high duty on its trivial $130,000 of sales, which soured relations with Japan because duties against Canadian clams were reduced. Japan also supplied $1 million of decidedly nonpremium, 2-cents-per-pound scrap and meal from fish processing plants, sold by the ton to poultry farms and fertilizer mixing plants.

In the vitamin-conscious United States oils pressed from fish livers provided vitamins D and A for humans and animals. Imports were welcomed duty-free because American fishermen could not meet the demand. Until war interrupted cod liver oil from Norway Japan had been a negligible source. Although synthetic substitutes for human nutrition seemed economically viable, livers harvested by Japanese vessels, primarily from tuna, yielded oils suitable for poultry. In 1940 prices tripled to 33 cents per pound. Imports from Japan jumped from almost nil to more than $2 million, about one-third of the vitamins fed to poultry. The future looked bright.10

In 1939 adult Americans didn’t venture outdoors bareheaded in the summer. U.S. factories turned out $44 million in summer hats for men and women. In Japan thirty thousand workers toiled constructing hat bodies, two-thirds sold to U.S. plants for finishing and trimming. Japan earned $2 million per year with no outlay for imported materials. It supplied “pedaline,” strips of tinted cellophane braided around hemp string, for forming hats, and “toyo” hat bodies of twisted rice paper coated with celluloid plastic for so-called harvest hats. The tariffs of 36 to 45 percent were taxes on low-income Americans because neither product could be made in the United States due to labor cost, lack of natural materials, and Japan’s advantage in celluloid. (Japan did not export felt bodies for winter hats because of a 110 percent duty and lack of local wool.) Women’s hat demand seemed positive as a bareheaded fad reversed, and men’s demand, too, as flat “boaters” gave way to dapper “Panama” hats.11

Japanese failures in selling manufactures to the United States were not always due to tariffs and quotas. Poor quality relegated some products to toehold niches in the cheapest items, sold for a few pennies apiece. Metal slide fasteners, or zippers, came into widespread use in the 1930s. In 1934, after a key patent expired, dozens of Japanese firms began exporting to America. Their low-wage advantage overcame a 45 percent duty and even a 66 percent rate imposed in 1936 when U.S. firms claimed dumping, although Japan had garnered only 5 percent of the market. Japan sold metal-toothed zippers at two cents per unit. Other patents barred it from locking-type zippers worth ten cents. But the greatest problem was poor quality—a jammed zipper ruined an entire sweater or suitcase. In the late 1930s Japanese exporters sold less than five hundred thousand dollars’ worth of zippers per year, only 3 percent by value of a rapidly growing market.12

Japan made headway, after some patent expirations, exporting miniature electric light bulbs to America, for cheap flashlights, toys, and Christmas tree decorations, at a fraction the price of U.S.-made bulbs. For the big market in automobile instrument bulbs, Japanese quality was too unreliable, a reason the Tariff Commission declined to raise a 20 percent duty as demanded by American factories. Japan maintained exports, including some large bulbs, at around $1 million. Its market share of miniatures in 1938 of 21 percent by volume was only 3 percent by value.13

Japanese workshops could surmount “ordinary” U.S. tariffs but several of their most promising lines failed to penetrate markets because of extravagant and unusual Smoot-Hawley tariffs. A longstanding principle of American tariff policy, intended to protect factory workers and investors, decreed that tariff rates should rise with degree of manufacture. Basic commodities not produced in America faced zero to moderate duties. Finished articles for the consumer faced the highest rates, typically 50 percent or so. Historically, the United States had levied two kinds of tariffs. Ad valorem duties were set at a fixed percentage of invoiced price. Their burden was countercyclical, diminishing when prices fell in depressions and rising with prices in prosperous times. Specific duties, usually applied to simple commodities, were levied as a fixed number of cents per pound, bale, gallon, or square yard. In depressions their effective rates rose as a percent of value as prices declined, and fell in good times. Specific duties punished foreign sellers when they were most vulnerable. They were especially punitive when applied to cheap, multipiece manufactures, leading to astonishingly high rates on small articles of uniquely Japanese origin. An unwritten U.S. tradition of capping duties at 90 percent, on the sensible notion that an industry unable to cope at twice foreign costs did not deserve protection, succumbed in the Great Depression.

Until 1930 Japanese consumer novelties encountered only ad valorem barriers. Rates were high but some could be surmounted because of low labor costs and in some cases Japanese materials or skills. The Smoot-Hawley Act, however, selectively imposed compound duties, a heavy-handed combination of ad valorem and specific rates. Congress voted very few compound duties, and those almost exclusively on items imported entirely from Japan. A Japanese product, say, a painted porcelain knick-knack landed at four cents, might pay 50 percent ad valorem and two cents per unit specific duty, a combined 100 percent tariff. In the Depression some duties rose far above 100 percent, sometimes to several hundred percent. Among the approximately twenty-one thousand rates that Congress legislated item by item under Smoot-Hawley, a search for manufactured consumer articles amounting to at least fifty thousand dollars’ worth of imports from all countries in 1931 that incurred effective duties of 100 percent or more turned up only a few classes of pottery, celluloid goods, buttons, and the like, uniquely Japanese, with tariff burdens of 110 to 164 percent. (A rare non-Japanese category was men’s silk opera hats from Europe at 121 percent. Even the wealthy suffered.) It is hard to fathom such malicious discrimination against Japan. Smoot-Hawley was fashioned during the summer of 1929, before the Depression, and signed in June 1930 before Japan’s aggression in Manchuria angered Americans. Japan was America’s second largest supplier of goods (after Canada) and third largest international customer (after Canada and Britain). Its raw cotton purchasing was a godsend to poor sharecroppers, white and black alike. Cheap Japanese wares did not compete against American labor. In a few cases Japanese workshops managed to cope by shifting upscale to middle class customers. For the most part, however, their wares for low-income consumers and children simply fell away by 1940.14

Japanese workmen and women crafted excellent china and porcelain tablewares from local clays in the Nagoya area, including the famous brands Noritake and Amari. Their elaborately hand-decorated pieces were unlike anything else available at affordable prices. (French Limoges and English bone china, made in part from calcined animal bones, sold for ten times the Japanese price.) Japanese porcelain was slender, translucent, and decorated with geometric and floral patterns that charmed customers. America’s large pottery industry mass produced only thick, heavy earthenware or stoneware dishes, sold glazed but undecorated for home tables and as semiglazed “white-ware” for hotels and restaurants. During the 1920s exports to America earned Japan $4 million per year. About half the sales were fancies and miniatures—delicate tea sets, condiment dishes, salt and pepper shakers, vases, and figurines such as the Cinderella slipper glazed in gold and sky blue that adorned my childhood shelf. Nevertheless, one or two U.S. firms lobbied so vociferously that Congress added to the 70 percent ad valorem rate (in effect since 1922) a compound duty on decorated pottery of ten cents per dozen pieces. The burden was extraordinary. Tea sets landed at ten to fifteen cents per dozen pieces incurred duties of 140 to 170 percent. The importing firm Morimura Brothers voiced the disappointment of families wanting something finer than stoneware and explained U.S. noncompetitiveness as being due to high labor cost. Its appeal was futile.

Japanese producers survived by shifting to larger items suited to U.S. lifestyles, for example, ninety-six-piece dinner services for twelve (twice the pieces in American stoneware sets), including large plates, covered meat platters, and coffee cups and saucers. A specific duty of 10 cents per dozen was more bearable on sets worth 50 to 60 cents per dozen than on table notions and bric-a-brac. The strategy held the duty to a barely tolerable 90 percent. Japan clung to an export business of $3 million annually through 1940, 30 percent of the U.S. tableware market. Glass tablewares, novelties, and lenses added half a million dollars.15

The saddest articles of Japanese failure were celluloid novelties. Although Japan never earned many dollars from them, the plight of this diverse industry vividly demonstrated the hopelessness of salvaging dollar earnings to offset silk’s decline. In the 1920s Japan had risen to world leadership in pyroxylin, the first commercial plastic, commonly known as celluloid. The basic raw material, nitrocellulose “gun cotton,” was produced by treating raw cotton with nitric and other acids. An addition of refined camphor, a “plasticizer” oil of the terpene family, reduced it to a gelatinous mass easily rolled at steam temperature into sheets—for example, clear cellophane or photography film—or precipitated as crystals for hot molding into intricate shapes of any color. Japan gained an early advantage from distilling the plasticizer from the branches of a laurel tree called Japan camphor that grew almost exclusively in Formosa. In 1899, four years after seizing Formosa from China, a Japanese government monopoly took control of camphor exports.

Production of celluloid articles blossomed in the United States, Europe, and Japan. The “artificial ivory” was fashioned into piano keys, billiard balls, cutlery handles, cigarette holders, combs, hairbrushes, dolls, and toys. But Japan’s advantage faded when German chemists learned to distill synthetic camphor from wood turpentine. The United States kept duties low because it did not manufacture synthetic camphor until 1934, when demand for automobile safety glass enticed the Du Pont company into its production behind a higher protective tariff. (Safety glass consisted of a tough celluloid membrane laminated between two sheets of glass that prevented flying shards in an accident. Synthetic camphor was preferred because the celluloid did not discolor.) Nevertheless, Japan supplied about 40 percent of U.S. camphor demand until the late 1930s, especially to Kodak for photo and movie film, but earning only $1 million per year, a fraction of the earlier peak.16

In small workshops and in homes Japanese workers mass produced hundreds of household articles molded of colored celluloid and assembled and decorated, extraordinarily cheap items sold to children and low-income families through low-priced chain stores. The five-and-dimes, pioneered by Frank W. Woolworth in the nineteenth century and popular in rural and urban America, were ideal outlets because they shopped the world for bargains and bought opportunistically in great quantities. In 1929 U.S. imports of Japanese celluloid goods reached $2.5 million despite a 60 percent ad valorem tariff. The outlook was strong until the Smoot-Hawley Act imposed punitive compound duties. Secretary of State Henry Stimson sent to the Senate, without comment, pitiable appeals by Japanese exporters, joined by Woolworth, to no avail.17 Three product lines illustrate the devastation of Japanese hopes.

Celluloid toothbrushes, molded in vivid colors and inset with Chinese hog bristles, were a Japanese specialty, as were toothbrush handles for brush completion in U.S. factories. Prospects were good as awareness of oral hygiene flourished in the 1920s. A Japanese toothbrush landed at 2.5 cents plus 60 percent ad valorem duty had provided a generous profit margin to five-and-dime chains retailing at 10 cents. The 1930 act imposed a specific duty of 2 cents a brush plus 50 percent ad valorem, effectively 125 percent. The cost rose beyond Woolworth’s ability to sell for 10 cents, a price point it never broke as a matter of policy. (Not until the eve of World War II did it sell articles for 25 cents.) In 1934 the Tariff Commission investigated competition from imports but mercifully recommended no further increases. Nevertheless Depression-era compound duties that rose as high as 129 to 142 percent squeezed Japan out of the market. Peak sales of ten million units earning Japan barely $300,000 dwindled by 1940 to two million units. The 10-cent child’s toothbrush disappeared, leaving the field to domestic 25-cent brushes sold in drugstores. Similarly thwarted by duties, Japanese hair brushes and combs also dwindled to insignificance.18

Another item demonstrating Japanese nimbleness in catching a fad, to no avail, was sun goggles, as sunglasses were known. Reacting to suave images from Hollywood, demand took off. In 1933 twenty-one U.S. firms produced thirteen million pair. The following year production rose 57 percent despite high costs mandated by the NIRA code. The profitability amazed the Tariff Commission. A pair with glass lenses worth 13 cents wholesale (only 20 percent of the cost being labor) sold for well over 25 cents retail. Japanese firms spotted a low-end opportunity. In 1933 they began exporting goggles stamped out of black celluloid sheet and sporting wire ear pieces. Landed at 3.5 cents plus 70 percent ad valorem (and no specific duty because they had been unknown in 1930), they were wildly popular in Woolworth’s at 10 cents retail. In the spring season of 1934 Japan delivered 1.1 million pair to capture 10 percent of the market by number, although far less by value. The Tariff Commission, in accordance with NIRA objectives, recommended a “voluntary” restraint of 2.1 million pair under threat of higher duty, but the order soon expired with the NIRA itself. Pressure for restraint remained, however. Imports peaked at about 6 million pair in 1937, earning Japan a meager $300,000. Thereafter taste migrated upscale to designer glasses made in small lots, an arena in which Japan was uncompetitive. By 1940 Japan exported almost no sun goggles to Americans.19

The tariff on celluloid toys was most brutal of all. Japanese workshops made very small toys for very small children: rattles, pinwheels, and tiny dolls a few inches long with movable arms and legs. Woolworth’s also sold miniature 1-cent celluloid knick-knacks for Christmas stockings and candy box prizes. (The flammability of cellulose apparently did not trouble parents in those days.) In 1929 Japan exported $2.3 million of plastic toys to America. Then Smoot-Hawley slapped a 1-cent-per-piece levy on top of 60 percent ad valorem. The formula devastated multipiece sets—soldiers for boys and doll families for girls. U.S. factories making larger and better 87-cent celluloid dolls had no intention of competing in “the small stuff.” U.S. importers pleading to Congress at hearings displayed toys bearing 200 percent duty, as well as trinkets and Christmas decorations at 600 to 800 percent, presumed to be the highest duty in American history. A few senators expressed shock at penalizing the poorest toddlers but refused to act. Japanese celluloid toy sales withered away to almost nil. In the 1930s some Japanese firms upgraded to higher-priced rubber and metal toys dutiable at “only” 70 percent but drew lawsuits against their shameless imitations of U.S. packaging and logos. The drive failed. Toy sales to America of $1.7 million in 1935 dwindled to $0.9 million in 1940.20