A cookie is a block of ASCII text that a web server can pass into a user’s instance of Netscape Navigator (and many other web browsers). Once received, the web browser sends the cookie every time a new document is requested from the web server. Cookies are transmitted by the underlying HTTP protocol, which means that they can be sent with HTML files, images (GIFs, JPEGs, and PNGs), sounds, or any other data type.

Netscape introduced “cookies” with Navigator Version 2.0. The original purpose of cookies was to make it possible for a web server to track a client through multiple HTTP requests. This sort of tracking is needed for complex web-based applications that need to maintain state between web pages.

Typical applications for cookies include the following:

A catalog site might use a cookie to implement an electronic “shopping cart.”

A news site might use cookies so that subscribers see local news and weather.

A subscription-only site might use cookies to store subscription information, so that a username/password combination does not need to be presented each time the user visits the site.

The preliminary cookie specification can be found at http://www.netscape.com/newsref/std/cookie_spec.html . RFC 2965, dated October 2000, outlines a proposed codification of the cookie specification, but as of August 2001 this standard had still not been adopted by the IETF.

A web server sends a cookie to your browser by transmitting a Set-Cookie message in the header of an HTTP transaction, before the HTML document itself is actually sent. Cookies can also be set using JavaScript.

Here is a sample Set-Cookie header:

Set-Cookie: comics=broomhilda+foxtrot+garfield; path=/comics; domain=.comics.net; [secure]

The Set-Cookie header contains a series of name=value pairs that are encoded

according to the HTTP specification for encoding URLs. The previous

example contains a single name=value field that sets the name

comics to be the value "broomhilda foxtrot garfield." [104] There are some special values:

- expires=time

Specifies the time when the cookie will expire. If no expiration time is provided, then the cookie is not written to the computer’s hard disk, and it lasts only as long as the current session.

- domain=

Specifies which computers will be sent the cookie. Normally, cookies will only be sent back to the computer that first sent the cookie to the user. In this example, the cookie will be sent to any host in the http://www.comics.net domain. If the domain is left blank, the domain is assumed to be the same as the domain for the web server that provided the cookie.

- path=

Controls which of the references will trigger the sending of the cookie. If

pathis not specified, the cookie will be sent for all HTTP transmissions to the web site. If path=/directory, then the cookie will only be sent when the pages underneath /directory are referenced. In this example, the cookies will be sent to any URL that is underneath the /comics/ directory.- secure

If the word

secureis provided as part of the Set-Cookie header, then the cookie can only be transmitted via SSL. (Don’t depend on this facility to keep the contents of your cookies private, as they are still stored unencrypted on the hard disk.)

Once a browser has a cookie, that cookie is transmitted by the browser with every successive request to the remote web site. For example, if the previous cookie was loaded into a browser and the browser attempted to fetch the URL http://www.comics.net/index.html, the following HTTP headers could be sent to the remote site:

GET /index.html HTTP/1.0 Cookie: comics=broomhilda+foxtrot+garfield

Here is an actual HTTP header sent by the site www.hotbot.com at 8:10 a.m. on April 21, 2001:

HTTP/1.1 200 OK Server: Microsoft-IIS/5.0 Date: Sat, 21 Apr 2001 12:05:56 GMT Set-Cookie: lubid=01000008C73351C5086C3AE177A40000351200000000; expires=Mon, 18-Jan- 2038 08:00:00 GMT; domain=.lycos.com; path=/ Set-Cookie: p_uniqid=aD3QMJX/K93Z; expires=Fri, 21-Dec-2012 08:00:00 GMT; domain=; path=/ Connection: Keep-Alive Content-Length: 22592 Content-Type: text/html Set-Cookie: remotehost=secondary=chi%2Emegapath&top=net; expires=Mon, 21-May-2001 07: 00:00 GMT; path=/ Set-Cookie: HB%5FSESSION=BT=lowend&BA=false&VE=&PL=Unknown&MI=u&BR= Unknown&MA=0&BC=1; path=/ Cache-control: private

The HotBot site sends four cookies, shown in Table 8-1.

Table 8-1. Cookies sent by www.hotbot.com at 8:10 a.m. EST on April 21, 2001

Cookie # | Content | Domain | Expires | Path |

|---|---|---|---|---|

1 | lubid=01000008C73351C5086C3AE177A40000351200000000 | .lycos.com | 18-Jan-2038 08:00:00 GMT | / |

2 | p_uniqid=aD3QMJX/K93Z | 21-Dec-2012 08:00:00 GMT | / | |

3 | remotehost=secondary=chi%2Emegapath&top=net | 21-May-2001 07:00:00 | / | |

4 | HB%5FSESSION=BT=lowend&BA=false&VE=&PL=Unknown&MI=u&BR=Unknown&MA=0&BC=1 | / |

Cookie #1 assigns a user tracking identifier to the web browser. Many web sites use such cookies to determine the number of unique visitors that they recover every month. Notice that although this cookie was downloaded from the site www.hotbot.com, its domain is set to .lycos.com. This cookie is what is called a third-party cookie . HotBot is a business unit of Lycos; this cookie allows Lycos to identify which Lycos users are also HotBot users. This type of cross-site cookie is permitted by some browsers but prohibited by others.

Cookie #2 is another user tracking cookie, but this one is solely for the HotBot site.

The purposes of Cookie #3 and Cookie #4 cannot immediately be determined from inspection. We contacted Lycos, Hotbot’s owner, to find out the purpose of these cookies. We were pointed at FAQs about how to disable cookies, but after several months of trying, we were unable to discover their actual purpose.

Broadly speaking, there are two ways that a web site can implement cookies:

The web site can use the cookie to contain the user’s actual data.

The cookie can simply contain a number of codes that key into a database that resides at the web provider.

Examples of these two approaches are shown in Table 8-2.

Table 8-2. Schematic views of cookies that contain customer data versus those that merely point to a database

Purpose of cookie | Possible contents for an implementation that keeps data on the user’s computer | Possible contents for an implementation that keeps data on the provider’s computer |

|---|---|---|

Provide customized weather reports and local news for a web site. | ZIP=20568 | UID=aaeff33413 |

Implement a shopping cart | PROD1=32 QUAN1=1 PROD2=34 QUAN2=1 PROD3=842 QUAN3=2 | USER=342234 |

Provide sign-on to a web site | USER=gene PASS=gandalf | USER=gene |

Cookies were originally envisioned as a place on the client where web servers could store user preferences and personal information. This way, no personal information would need to be stored on the client. But as the cookies from the HotBot web site show, today one of the most popular uses of cookies is to give a permanent identification number to each user so that the number of “unique visitors” to a web site can be measured. These numbers can be very important when a company is attempting to sell advertising space on its web site.

Many advertisers themselves use cookies to build comprehensive profiles of web users. These cookies are served with banner advertisements. Each time a web user views a banner advertisement, the database server at the advertising company notes the content of the web site that the customer was viewing. This information is then combined to create a web profile. A typical profile might say how much a person is interested in sports or in consumer electronics, or how much he follows current events and the news. Web advertisers say that these profiles are “anonymous” because they do not contain names, addresses, or other kinds of personally-identifiable information. However, it is possible to unmask this anonymous data if the profiles are combined with other information, such as IP addresses or registration information provided at web sites.

Cookies allow advertisers to have a great deal of control over the advertisements that each user sees, regardless of the actual web site that a person is visiting. For example, using cookies, an advertiser can assure that each person will only see a particular Internet advertisement once (unless the advertiser pays for repeat exposure, of course). Cookies can be used to display a sequence of advertisements to a single user, even if they are jumping around among different pages on different web sites. Cookies allow users to be targeted by area of interest. Advertisers can further tailor advertisements to take into account the query terms that web surfers use.

All cookies are open to examination. Unfortunately, it can be very difficult to determine what cookies are used for by merely examining them, as the cookies in Table 8-1 demonstrate.

Cookies are kept in the web browser’s memory. If a cookie is persistent (that is, it has an expiration date), the cookie is also saved by the web browser on the computer’s hard drive.

Netscape Navigator and Internet Explorer store cookies in different way. Navigator stores cookies in a single file called cookies.txt , which can be found in the user’s preference directory. (On Unix systems, Navigator stores cookies in the ~/.netscape/cookies file.)

A sample Netscape cookies file is shown in Example 8-2.

Example 8-2. A sample Netscape cookies file

# Netscape HTTP Cookie File

# http://www.netscape.com/newsref/std/cookie_spec.html

# This is a generated file! Do not edit.

.techweb.com TRUE /wire/news FALSE 942169160 TechWeb 204.31.228.79.852255600 path=/

.hotwired.com TRUE / FALSE 946684799 p_uniqid yQ63oN3ALxO1a73pNB

.talk.com TRUE / FALSE 946684799 p_uniqid y46RXMoBwFwD16ZFTA

.packet.com TRUE / FALSE 946684799 p_uniqid y86ijMoA9MhsGhluvB

.boston.com TRUE / FALSE 946684799 INTERSE stl-mo8-10.ix.netcom.

com20748850376179639

.netscape.com TRUE / FALSE 1609372800 MOZILLA MOZ-ID=DFJAKGLKKJRPMNX[-]MOZ_VERS=1.

2[-]MOZ_FLAG=2[-]MOZ_TYPE=5[-]MOZ_CK=AJpz085+6OjN_Ao1[-]

.netscape.com TRUE / FALSE 1609372800 NS_IBD IBD_

SUBSCRIPTIONS=INC005|INC010|INC017|INC018|INC020|INC021|INC022|INC034|INC046

www.xmission.com FALSE / FALSE 946511999 RoxenUserID 0x7398

ad.doubleclick.net FALSE / FALSE 942191940 IAF 22348bb

.focalink.com TRUE / FALSE 946641600 SB_ID ads01.28425853273216764786

gtplacer.globaltrack.com FALSE / FALSE 942105660 gtzopyid 85317245

.netscape.com TRUE / FALSE 1585744496 REG_DATA C_DATE_REG=13:06:51.304128 01/

17/97[-]C_ATP=1[-]C_NUM=0[-]

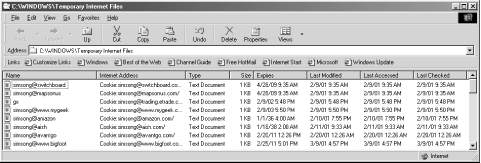

www.digicrime.com FALSE FALSE 942189160 DigiCrime virus=1Internet Explorer saves each cookie in an individual file. The files are stored in the directory referenced by the Registry name Cookies, in the key \HKEY_CURRENT_USER\Software\Microsoft\Windows\CurrentVersion\Explorer\User Shell Folders. This directory is C:\Windows\Cookies on Windows 95/98/ME systems configured for a single user, or in the directory C:\Windows\Profiles\username\Cookies on Windows 95/98/ME systems configured for multiple users (see Figure 8-3). A sample Internet Explorer Cookies file is shown in Example 8-3.

Users can modify the contents of their cookies. For this reason, a web site should always regard a cookie’s contents as potentially suspect. If the cookie is used to gain access to information that might be considered private, confidential, or sensitive, then measures should be built into the cookie so that a modified cookie will not be accepted by the web application.

Consider the following two hypothetical cookies. Both of these cookies belong to a hypothetical web site that allows a consumer to view stored transactions. The cookies give the consumer access by providing the consumer’s identification number to the web application server. The first cookie is not a secure cookie. The second cookie may be secure, as we will explain.

- Cookie #1

id=4531

- Cookie #2

id=34343339336

In the first cookie, the consumer’s identification number is simply “4531.” Presumably, these identification numbers are being assigned in a sequential order. If the consumer were to edit his or her cookie file and change the number from “4531” to another number, like “4533,” it is quite probable that the consumer would then have access to another consumer’s order information. Essentially, the first consumer can easily create counterfeit cookies!

A consumer visiting a web site that uses the second cookie can change his identification number as well. However, a consumer changing “34343339336” to another number is likely to be less successful than a consumer changing the number “4531.” This second web site almost certainly does not assign its identification numbers sequentially; there are not 34,343,339,336 Internet users (yet)! So a consumer making a change to this second cookie is unlikely to accidentally hit upon a valid identification number belonging to another consumer.

To create the most secure cookies, some web sites use digital signatures or cryptographic MAC codes. Such techniques make it exceedingly unlikely that a consumer will be able to create a counterfeit cookie, provided that the MAC actually covers all of the information in the cookie, rather than the data in the fields after they are decoded. More information on creating cookies that are really secure can be found in Chapter 16.

Tip

Some web sites are set up so that if you have a cookie, you are given unrestricted access to your account information. Other web sites are set up so that even if you have a cookie, you must still type a password to gain access to your confidential information. In general, web sites that require a password to be typed are more secure. This is because your cookie can easily end up on somebody else’s machine—for example, if you check your account information using a friend’s computer. If you are a web developer, you should never make the mistake of thinking that cookies are secure.

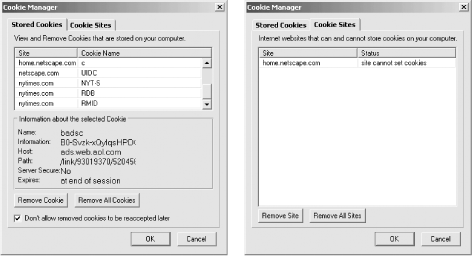

Both Netscape Navigator and Internet Explorer have options that will allow you to be notified when a cookie is received. Current versions of these programs allow you to accept all cookies, reject all cookies, or be prompted for each cookie whether you wish to accept it or not. Newer versions of these browsers allow you to control cookie acceptance on a site-by-site basis. Netscape 6.0 allows you to delete cookies on a case-by-case basis, as shown in Figure 8-4.

Unfortunately, neither browser will let you disable the sending of cookies that have already been accepted. To do that, you must toss your cookies.

There are additional techniques that you can use to block cookies. These techniques work with all browsers, whether they have cookie control or not.

Under Unix-based systems, users can delete the cookies file and replace it with a link to /dev/null. On Windows systems, the file can be replaced with a zero-length file with permissions set to prevent reading and writing. On a Macintosh you can replace the file with a locked, zero-length file or folder.

Alternatively, you can simply accept the cookies you wish and then make the cookies file read-only. This will prevent more cookies from being stored inside.

You can disable cookies entirely by patching the binary executable for your copy of Netscape Navigator or Internet Explorer. Search for the string

Set-Cookieand change it toSet-Fookie. It’s unlikely that anyone will be sending you any Fookies, so that should be sufficient.

Filter programs, such as AdSubtract, can also give users control over cookies. For further information, see Chapter 10.