Lamu

Lamu town has that quality of immediately standing out as you approach it from the water (and let’s face it – everything is better when approached from water). The shopfronts and mosques, faded under the relentless kiss of the salt wind, creep out from behind a forest of dhow masts. Then you take to the streets, or more accurately, the labyrinth: donkey-wide alleyways from which children grin; women whispering by in full-length bui-bui (black cover-all worn by some Islamic women outside the home); cats casually ruling the rooftops; blue smoke from meat grilling over open fires and the organic, biting scent of the cured wooden shutters on houses built of stone and coral. Many visitors call this town – the oldest living town in East Africa, a Unesco World Heritage site and arguably the most complete Swahili town in existence – the highlight of their trip to Kenya. Residents call it Kiwa Ndeo – The Vain Island – and, to be fair, there’s plenty for them to be vain about.

Lamu

1Top Sights

6Drinking & Nightlife

DON'T MISS

DHOW TRIPS

More than the bustle of markets or the call to prayer, the pitch of, ‘We take dhow trip, see mangroves, eat fish and coconut rice’, is the unyielding chorus Lamu’s voices offer up when you first arrive. That said, taking a dhow trip (and seeing the mangroves and eating fish and coconut rice) is almost obligatory and generally fun besides, although this depends to a large degree on your captain. There’s a real joy to kicking it on the boards under the sunny sky, with the mangroves drifting by in island time while snacking on spiced fish.

Trips include dhow racing excursions (learning how to tack and race these amazingly agile vessels is quite something), sunset sails, adventures to Kipungani and Manda, deep-reef fishing and even three-day trips south along the coast to Kilifi (from USD$100 per person).

Prices vary depending on where you want to go, who you go with and how long you go for. Bwana Dolphin (![]() %0726732746) is a recommended local captain. With bargaining you could pay around KSh2500 per person in a group of four or five people, on a half-day basis. Don’t hand over any money until the day of departure, except perhaps a small advance for food. On long trips, it’s best to organise your own drinks. A hat and sunscreen are essential.

%0726732746) is a recommended local captain. With bargaining you could pay around KSh2500 per person in a group of four or five people, on a half-day basis. Don’t hand over any money until the day of departure, except perhaps a small advance for food. On long trips, it’s best to organise your own drinks. A hat and sunscreen are essential.

1Sights

Lamu is one of those places where the real attraction is just the overall feel of the place and there actually aren’t all that many ‘sights’ to tick off.

Lamu MuseumMUSEUM

(

MAP

GOOGLE MAP

; Harambee Ave, Waterfront; adult/child KSh500/250; ![]() h8am-6pm)

h8am-6pm)

The best museum in town is housed in a grand Swahili warehouse on the waterfront. This is as good a gateway as you’ll get into Swahili culture and that of the archipelago in particular. Of note are the displays of traditional women’s dress – those who consider the head-to-toe bui-bui restrictive might be interested to see the shiraa, a tent-like garment (complete with wooden frame to be held over the head) that was once the respectable dress of local ladies. There are also exhibits dedicated to artefacts from Swahili ruins, the bric-a-brac of local tribes and the nautical heritage of the coast (including the mtepe, a traditional coir-sewn boat meant to resemble the Prophet Mohammed’s camel – hence the nickname, ‘camels of the sea’). Guides are available to show you around.

Lamu FortFORTRESS

( MAP GOOGLE MAP ; Main Sq)

This squat castle was built by the Sultan of Paté from 1810 and completed in 1823. From 1910 right up to 1984 it was used as a prison. It now houses the island’s library, which holds one of the best collections of Swahili poetry and Lamu reference work in Kenya. Entrance is free with a ticket to the Lamu Museum.

Lamu MarketMARKET

( MAP GOOGLE MAP ; opposite Lamu Fort)

Atmospheric and chaotic, this quintessential Lamu market is best visited early in the morning. Bargain for stinking fresh tuna and sailfish, wade through alleys teeming with stray cats, dogs and goats, and experience Lamu at its craziest. If you're sick of seafood, this is the place to find your five-a-day.

Swahili HouseMUSEUM

(

MAP

GOOGLE MAP

; adult/child KSh500/250; ![]() h8am-6pm)

h8am-6pm)

This preserved Swahili house, tucked away to the side of Yumbe House hotel, is beautiful, but the entry fee is very hard to justify, especially as half the hotels in Lamu are as well preserved as this small house.

German Post Office MuseumMUSEUM

(

MAP

GOOGLE MAP

; Kenyatta Rd; adult/child KSh500/250; ![]() h8am-6pm)

h8am-6pm)

In the late 1800s, before the British decided to nip German expansion into Tanganyika in the bud, the Germans regarded Lamu as an ideal base from which to exploit the interior. As part of their efforts, the German East Africa Company set up a post office, and the old building is now a museum exhibiting photographs and memorabilia from that fleeting period when Lamu had the chance of being spelt with an umlaut.

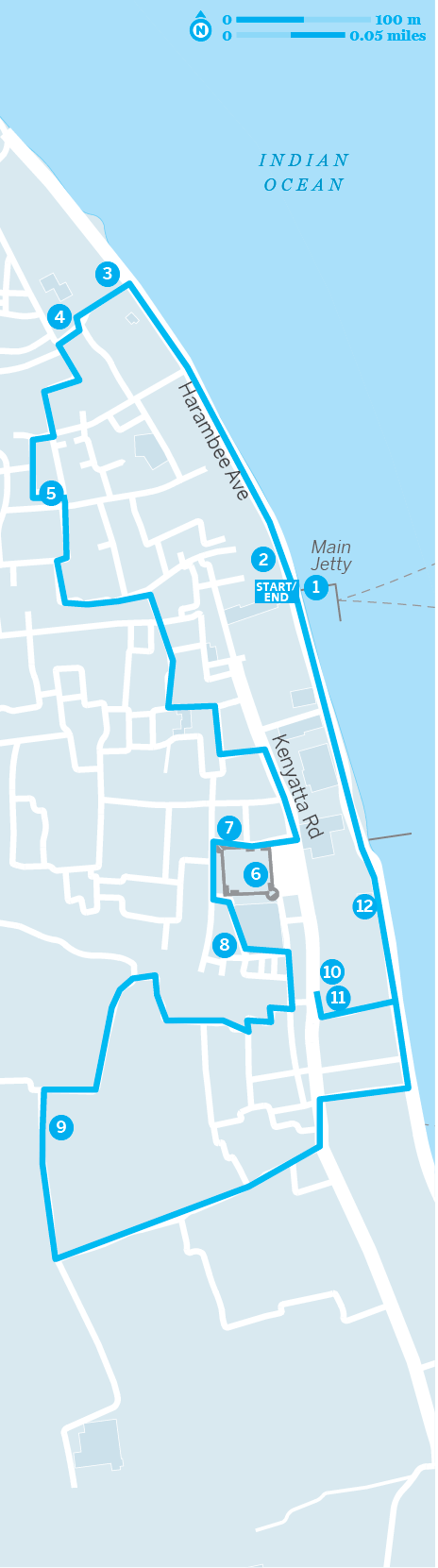

Lamu Walking Tour

Start Lamu main jetty

Finish Shiaithna-Asheri Mosque

Distance About 1km

Duration 45 minutes to one hour

The best, indeed only, way to see Lamu town is on foot. Few experiences compare with exploring the far back streets, where you can wander amid wafts of cardamom and carbolic and watch the town’s agile cats scaling the coral walls. There are so many wonderful Swahili houses that it’s pointless for us to recommend specific examples – keep your eyes open wherever you go, and don’t forget to look up.

Starting at the 1main jetty, head north past the 2Lamu Museum and along the waterfront until you reach the 3door-carving workshops.

From here head onto Kenyatta Rd, passing an original Swahili 4well, and into the alleys towards the 5Swahili House Museum. Once you’ve had your fill of domestic insights, take any route back towards the main street.

Once you’ve hit the main square and the 6fort, take a right to see the crumbled remains of the 14th-century 7Pwani Mosque, one of Lamu’s oldest buildings – an Arabic inscription is still visible on the wall. From here you can head round and browse the covered 8market, then negotiate your way towards the bright Saudi-funded 9Riyadha Mosque, the centre of Lamu’s religious scene.

Now you can take as long or as short a route as you like back to the waterfront. Stroll along the promenade, diverting for the aGerman Post Office Museum if you haven’t already seen it – the door is another amazing example of Swahili carving. If you’re feeling the pace, take a rest and shoot the breeze on the bbaraza ya wazee (‘old men’s bench’) outside the stucco minarets of the cShiaithna-Asheri Mosque.

Carrying on up Harambee Ave will bring you back to the main jetty.

zFestivals & Events

Maulid FestivalRELIGIOUS

(www.lamu.org/maulid-celebration.html)

The Maulid Festival celebrates the birth of the Prophet Mohammed. Its date shifts according to the Muslim calendar (December 2015). The festival has been celebrated on the island for over 100 years and much singing, dancing and general jollity takes place around this time. On the final day a procession heads down to the tomb of the man who started it all, Ali Habib Swaleh.

Lamu Cultural FestivalCULTURAL

Exact dates for this colourful carnival vary each year, but it often falls in November. Expect donkey and dhow races, Swahili poets and island dancing.

SAFETY ON LAMU

In September 2011 an English couple staying on the island of Kiwayu, north of Lamu, were attacked by Somali pirates/militants. One person died and one was kidnapped and taken to Somalia. It was widely thought that this was a one-off attack and that Lamu itself was not at risk. However, despite a massive beefing up of security, just over two weeks later another attack occurred. This time a French woman was kidnapped from her home on Manda Island and taken to Somalia (where she later died from a diabetic incident).

Following a series of armed attacks in Mombasa in mid-2014, the coastal town of Mpeketoni (25km from Lamu Town) was hit by what was at the time believed to be Al-Shabaab militants claiming revenge for the presence of Kenyan troops in Somalia and the killing of Muslims. Further analysis suggested that these attacks were likely perpetrated by Somali and Oromo residents in an attempt to deflect blame onto Al-Shabaab (using the group's flag as a guise) and claim the area as their ancestral home after Kenya's first President, Jomo Kenyatta settled ethnic Kikuyus on their land after independence.

Many countries advised against travel to Lamu in the wake of these attacks, resulting in void travel insurance policies and a drop in tourism that devastated local communities. A curfew was in place on Lamu at the time of research and we urge you to check the latest on the security situation before travelling. At the time of going to print there had been no further attacks and independent travellers were starting to return to these otherwise blessed isles.

4Sleeping

The alleyways of Lamu are absolutely rammed with places to stay and competition means that prices are often lower than in other parts of Kenya. There’s always scope for price negotiation, especially if you plan to stay for over a day or two. Touts will invariably try and accompany you to get commission; the best way to avoid this is to book at least one night in advance, so you know what you’ll be paying.

![]() oNew Bahati LodgeGUESTHOUSE

oNew Bahati LodgeGUESTHOUSE

(

MAP

GOOGLE MAP

; ![]() %0726732746; www.lamuguesthouse.com; d/tr KSh1400/2500)

%0726732746; www.lamuguesthouse.com; d/tr KSh1400/2500)

This newly renovated budget house occupies prime position in Lamu's old town and pulls in plenty of budget travellers. The rooms are clean, fresh and spacious, but you'll probably spend most of your time in the loungey chill-out areas. The master bedroom at the top of the house has the best ocean view.

![]() oBaitul Noor HouseBACKPACKERS

oBaitul Noor HouseBACKPACKERS

(

MAP

GOOGLE MAP

; ![]() %0725220271, 0723760296; www.lamubackpackers.com; dm/s/d KSh1000/1500/2500)

%0725220271, 0723760296; www.lamubackpackers.com; dm/s/d KSh1000/1500/2500)

From the Arabic for 'house of light', this 16th-century town house is the stylish new backpackers on the block. The dorms are lovely and eco-friendly, featuring seven-foot beds, homemade soaps and solar reading lamps. Don't miss the stylish roof terrace and the downstairs restaurant, which does lobster suppers for lemonade pockets. Helpful staff can arrange all manner of excursions.

Yumbe HouseBOUTIQUE HOTEL

(

MAP

GOOGLE MAP

; ![]() %0726732746; www.lamuguesthouse.com; s/d KSh2500/3200)

%0726732746; www.lamuguesthouse.com; s/d KSh2500/3200)

This beautiful 17th-century house is made from coral, which is reason enough to stay here. Add spacious rooms decorated with pleasant Swahili accents, verandahs that are open to the stars and the breeze, and a ridiculously romantic top-floor suite. Top value for your shilling.

![]() oSubira HouseGUESTHOUSE

oSubira HouseGUESTHOUSE

(

MAP

GOOGLE MAP

; ![]() %0726916686; www.subirahouse.com; r KSh5000-8000)

%0726916686; www.subirahouse.com; r KSh5000-8000)

This beautiful house features graceful arches and twin gardens with wells. The Swedish owners certainly know a thing or two about style, as did the Sultan of Zanzibar when he built the house 200 years ago. As well as seven stylish bedrooms, there are galleries in which to relax and serious eco-credentials. We rate the restaurant highly.

![]() oLamu HouseBOUTIQUE HOTEL

oLamu HouseBOUTIQUE HOTEL

(

GOOGLE MAP

; ![]() %0708073164, 0708279905; www.lamuhouse.com; Harambee Ave; r US$230-490)

%0708073164, 0708279905; www.lamuhouse.com; Harambee Ave; r US$230-490)

In a town where every building wants to top the preservation stakes, Lamu House stands out. It looks like an old Swahili villa, but it feels like a stylish boutique hotel, blending the pale, breezy romance of the Greek islands into an African palace, with predictably awesome results. The excellent Moonlight restaurant serves fine Swahili cuisine.

A free boat service to Manda Island leaves from here every morning at 8am.

5Eating

Lamu’s fruit juices, which almost every restaurant sells, are worth drawing attention to. They’re good. They’re really, really good.

Many of Lamu's cheap places to eat close until after sunset during Ramadan.

![]() oTehranKENYAN

oTehranKENYAN

( GOOGLE MAP ; Kenyatta Rd; mains from KSh100)

This very atmospheric but basic place doesn’t even have a sign, but it does serve dirt-cheap meals of fish, beans (the best is maharagwe ya chumvi – with coconut milk) and chapatis. It’s consistently packed with locals and is pretty much open all the time.

Bustani CaféCAFE

( MAP GOOGLE MAP ; meals KSh320-500)

This pretty garden cafe has tables set about a lily-bedecked pond. The small menu includes lots of healthy salads and various snack foods. It also contains a decent bookshop and an evening-only internet cafe (KSh240 per hour).

Olympic RestaurantAFRICAN

( MAP GOOGLE MAP ; Harambee Ave; mains KSh450-900)

The family that runs the Olympic makes you feel as if you’ve come home every time you enter, and their food, particularly the curries and biriyani, is excellent. There are few better ways to spend a Lamu night than with a cold mug of passionfruit juice and the noir-ish view of the docks you get here, at the ramshackle end of town.

![]() oMwana Arafa Restaurant GardensSEAFOOD

oMwana Arafa Restaurant GardensSEAFOOD

( MAP GOOGLE MAP ; Harambee Ave; meals KSh350-1200)

Everyone loves Mwana Arafa. It has the perfect combination of garden seating and views over the dhows bobbing about under the moonlight. With barbecued giant prawns, grilled calamari, lobster or a seafood platter, we guess you’ll be eating the fruits of the sea tonight.

6Drinking & Nightlife

As a Muslim town, Lamu has few options for drinkers and local sensibilities should be respected. Full moon parties sometimes take place in season over on Manda Island.

Petley’s InnBAR

( MAP GOOGLE MAP ; Harambee Ave)

Right in front of the main jetty, Petley's seems to be the local watering hole for just about everyone. Expect almost anything, from good fun and merriment to enough hassle to speed you through the doors.

7Shopping

If you're into unusual fabrics, you can pick up bags made from the recycled cotton of dhow sails, often decorated with iconic Lamu images. Textile fans will also enjoy shopping for material sourced from Oman and Somalia. Head north along Kenyatta Rd from the direction of the fort and you'll find a scattering of places selling such wares, as well as some high-quality silversmiths. Perhaps the most charismatic among them is a chap called Slim, whose silversmith shop – with the original name of Slim Silversmith – sells beautiful rings created from ancient cuttings of coloured tiles.

Baraka GalleryARTS & CRAFTS

( MAP GOOGLE MAP ; Kenyatta Rd)

For upmarket Africana, Baraka Gallery has a fine selection, but stratospheric prices.

Black & White GalleryARTS & CRAFTS

( MAP GOOGLE MAP )

Spanish-run art shop with some beautiful tribal-inspired crafts and paintings.

Lamu Museum ShopBOOKS

( MAP GOOGLE MAP ; Harambee Ave)

Specialists in Lamu and Swahili cultural books.

8Information

Dangers & Annoyances

At the time of research, some governments were advising against travel to Lamu and the wider region.

When times are normal the biggest real issue are the beach boys. They’ll come at you the minute you step off the boat, offering drugs, tours and hotel bookings (the last can be useful if you’re disoriented).

Lamu has long been popular for its relaxed, tolerant atmosphere, but it does have somewhat conservative views as to what is acceptable behaviour. In 1999, a gay couple who planned a public wedding here had to be evacuated under police custody. Whatever your sexuality, it’s best to keep public displays of affection to a minimum and respect local attitudes to modesty.

Female travellers should note that most Lamurians hold strong religious and cultural values, and may be deeply offended by revealing clothing. There have been some isolated incidents of rape, which locals say were sparked by tourists refusing to cover up. That may outrage some Western ears, but the fact remains that you risk getting into hot water if you walk around in small shorts and low-cut tops. There are miles of deserted beaches on which you can walk around butt naked if you choose, but we urge you to respect cultural norms in built-up areas.

Internet Access

Medical Services

King Fahd Lamu District HospitalHOSPITAL

(![]() %012-633075)

%012-633075)

This government-run hospital is rundown but has competent medical staff.

Langoni Nursing HomeMEDICAL

(

GOOGLE MAP

; ![]() %012-633349; Kenyatta Rd;

%012-633349; Kenyatta Rd; ![]() h24hr)

h24hr)

Don't be put off by the name; this clinic offers GP services.

Money

Kenya Commercial BankBANK

(

GOOGLE MAP

; ![]() %012-633327; Harambee Ave)

%012-633327; Harambee Ave)

The main bank on Lamu, with an ATM (Visa only).

Tourist Information

Tourist OfficeTOURIST INFORMATION

(

GOOGLE MAP

; ![]() %012-633132; lamu@tourism.go.ke; Harambee Ave;

%012-633132; lamu@tourism.go.ke; Harambee Ave; ![]() h9am-1pm & 2-4pm)

h9am-1pm & 2-4pm)

A commercial tour and accommodation agency that also provides tourist information.

8Getting There & Away

Air

The airport at Lamu is on Manda Island, and the ferry across the channel to Lamu costs KSh150.

AirkenyaAIRLINE

(

MAP

GOOGLE MAP

; ![]() %042-633445; www.airkenya.com; Baraka House, Kenyatta Rd)

%042-633445; www.airkenya.com; Baraka House, Kenyatta Rd)

Daily afternoon flights between Lamu and Wilson Airport in Nairobi (US$195).

Fly540AIRLINE

(![]() %042-632054; www.fly540.com)

%042-632054; www.fly540.com)

Flies twice daily to Malindi (around US$45) and Nairobi (around US$170).

Bus

There are booking offices for several bus companies on Kenyatta Rd on Lamu. The going rate for a trip to Mombasa (8-9 hours) is KSh800 to KSh900; most buses leave between 7am and 8am, so you’ll need to be at the jetty at 6.30am to catch the boat to the mainland. Book early and be on time. Buses deliberately leave on the dot in order to resell the seats of latecoming passengers further up the line. The most reliable companies are Simba (![]() %0707471110, 0707471111), Tahmeed (

%0707471110, 0707471111), Tahmeed (![]() %0724581015, 0724581004) and Tawakal (

%0724581015, 0724581004) and Tawakal (![]() %0705090122). Note that prices tend to increase by KSh100-200 during the high season.

%0705090122). Note that prices tend to increase by KSh100-200 during the high season.

At the time of research, armed guards were on every Lamu-bound bus from Mombasa. Matatus, as you'd imagine, have no such security assurances.

Coming from Mombasa to Lamu, buses will drop you at the mainland jetty at Mokowe. From there you can either catch the passenger ferry (KSh100, 30-40 mins) or a speedboat (KSh150, 10mins travel).

8Getting Around

Ferries between the airstrip on Manda Island and Lamu cost KSh150 and leave about half an hour before the flights leave (yes, in case you’re wondering, all the airline companies are aware of this and so that’s sufficient time).

Between Lamu village and Shela there are plenty of motorised dhows throughout the day until around sunset; these cost about KSh150 per person and leave when full.

There are also regular ferries between Lamu and Paté Island.

Islands Around Lamu

The Lamu archipelago has plenty to offer outside Lamu itself. The easiest to get to is Manda Island, just across the channel, where most visitors go on dhow trips for snorkelling and to visit the Takwa ruins. The tiny Manda Toto Island, on the other side of Manda, has perhaps the best reefs on the coast.

Further northeast, Paté Island was the main power centre in the region before Lamu came to prominence, but is rarely visited now, preserving an uncomplicated traditional lifestyle as much by necessity as by choice. A regular motor launch shuttles between the towns of Mtangawanda, Siyu, Faza and Kizingitini.