(what Ricardo called exchangeable values, relative values, or simply values) between commodities

(what Ricardo called exchangeable values, relative values, or simply values) between commodities  reads:

reads:3 Money and the invariable standard

In a sound state of the currency the value of gold may vary, but its price cannot.

(Evidence before the Commons’ Committee on Resumption, 4 March 1819; V: 392)

First it may be useful to give in Section 3.1 some definitions of the main notions used by Ricardo in his theory of money (additional ones will be introduced in subsequent chapters). They are deliberately borrowed from Principles or later papers. Two issues are raised in Sections 3.2 and 3.3 respectively: the relation between the value of money, the price of gold bullion, and the general price level, and the relation between the standard of money and the standard of value. Section 3.4 concludes on the contribution of Ricardo’s theory of value and distribution to his understanding of both relations, hence to his theory of money.

Commodities: exchangeable value, money price, absolute value

The commodities considered by Ricardo in Principles are exclusively those which are produced in competitive conditions:

In speaking then of commodities, of their exchangeable value, and of the laws which regulate their relative prices, we mean always such commodities only as can be increased in quantity by the exertion of human industry, and on the production of which competition operates without restraint.

(Principles; I: 12)

Ricardo distinguished between the value of such a commodity and its price (Principles, Chapter I). The value of a commodity is expressed in terms of another commodity; Ricardo indifferently used to designate it the terms “exchangeable value”, “relative value”, “proportional value”, or simply “value”. The price of a commodity is expressed in terms of money. It can thus change either because of a change on the side of the commodity – affecting its value – or of a change on the side of money – that is, a variation in the value of money:

In stating the principles which regulate exchangeable value and price, we should carefully distinguish between those variations which belong to the commodity itself, and those which are occasioned by a variation in the medium in which value is estimated, or price expressed.

(ibid: 48)

These two kinds of variations combine to affect the price of a commodity; in other words, the money price of a commodity is equal to the ratio of the value of the commodity to the value of money, as illustrated by the following quotation (in which the “real value” is understood by Ricardo as the quantity of labour supposed to determine the value of shoes as well as of gold-money):

The word price I think should be confined wholly to the value of commodities estimated in money, and money only. If so confined, a commodity may rise in real value without rising in price. If more labour should be required than before to work the mines, and to manufacture shoes, it is possible that shoes may continue unaltered in price, but both the shoes, and gold (or money) will have risen in value.

(Letter to Trower, 18 September 1818; VII: 297, Ricardo’s emphasis)

When all competitively produced commodities sell for money at their “natural price”, all portions of capital advanced in their production earn the same rate of profit. A synonym of natural price is “cost of production”, expressed in money and including the same rate of profit on all portions of capital: “In cost of production I always include profits at their current rate” (Notes on Malthus; II: 369). By “market price” of a commodity Ricardo meant the price as it results from the interplay of the supply of and the demand for the commodity (the same distinction occasionally applied to “natural value” – corresponding to the permanent state of the economy – and “market value” – reflecting temporary market forces). In the case of competitively produced commodities, the market price of a commodity may deviate from the natural price, but this creates differences in the rate of profit that generate movements of capital from one employment to the other. Consequently the rate of profit tends to equalise for all portions of capital (Principles, Chapter IV), and “cost of production [is] the pivot about which all market price moves” (Notes on Malthus; II: 25). Commodities that are monopolised – and to which Ricardo devoted interest insofar as they contrasted with competitively produced ones – have only a market price, since their quantity cannot be increased by the competition of other portions of capital than those applied to them:

Commodities which are monopolized, either by an individual, or by a company, vary according to the law which Lord Lauderdale has laid down: they fall in proportion as the sellers augment their quantity, and rise in proportion to the eagerness of the buyers to purchase them; their price has no necessary connexion with their natural value: but the prices of commodities, which are subject to competition, and whose quantity may be increased in any moderate degree, will ultimately depend, not on the state of demand and supply, but on the increased or diminished cost of their production.

(Principles; I: 385)

In contrast with the “nominal value” of a commodity (“either in coats, hats, money, or corn”, ibid: 50) – that is, its exchangeable value in any commodity or its money price – Ricardo called “absolute value” of a commodity its value in terms of an “invariable measure of value” or invariable “standard of value” (see below Section 3.3).

Money: measure of price, circulating medium, standard of money

The two aspects of money are mentioned in the summary heading, introduced for the second edition of 1819 and kept in the third, of Chapter I Section VII of Principles:

Different effects from the alteration in the value of money, the medium in which PRICE is always expressed, or from the alteration in the value of commodities which money purchases.

(ibid: 47; Ricardo’s emphasis)

As “the medium in which price is always expressed”, money is itself measured in a unit (in England the pound sterling, divided in 20 shillings of 12 pence each). In a system endowed with a metallic standard of money, this monetary unit is legally defined as a given weight of standard metal, gold or silver in bullion. This amounts to proclaiming that one unit of weight of the standard metal in coin is legal tender for a given amount of the monetary unit. In England, the unit of weight of standard gold and silver was the ounce, divided in 20 dwts. (pennyweights) of 24 grains each. After the de jure adoption of the gold standard in 1816, the pound sterling was legally defined as 5 dwts. 3.274 grains (or 123.274 grains) of standard gold 22/24 fine,1 making 3 pounds 17 shillings 10½ pence the legal price of an ounce of standard gold – the “mint price” already adopted since 1717 for the coining of gold.

As the medium of exchange (between “commodities which money purchases”), money appears in Ricardo under two names: “currency” and “circulating medium”. By currency he meant money being legal tender, that is, in the circumstances of the time, coin: even when in 1821 the Bank of England note was again made convertible into gold coin, it was not legal tender (it would only become so in 1833). By circulating medium Ricardo meant the currency plus the bank notes “representing” the currency, that is, the Bank of England note and the Country Banks notes (which were convertible into Bank of England notes). He did not include in the circulating medium the various instruments of credit, the use of which, however, affected the quantity of money required to circulate commodities (see Chapter 9 below).

The “value of money” in circulation is defined by Ricardo as its purchasing power in the market for all commodities taken together except the standard of money, to be distinguished from the purchasing power of money over the standard itself – the reciprocal of the market price of bullion (see Section 3.2 below). Accordingly, a fall (or a rise) in the value of money meant a proportional rise (respectively a fall) in all money prices except that of bullion, while a depreciation (or appreciation) of money was measured by a rise (respectively a fall) in the market price of bullion.

Two functions of the standard of money corresponded to the two aspects of money – measure of price and circulating medium. On the one hand, with gold bullion the standard of money, a given weight of gold defined the monetary unit (the pound sterling) and the unit of currency (from 1816 on, the coin called sovereign). On the other hand, convertibility of gold bullion into money and of money into gold bullion regulated the quantity of money (see below Chapter 7). Although he clearly made the distinction between the notions of standard of value and of standard of money, Ricardo assumed that gold bullion could be both (see below Section 3.3).

The condition of coherence of the price system

Let me express in modern parlance how the question of the integration of money in the theory of value is raised in Ricardo. In a market economy, the condition of coherence of any system of relative prices  (what Ricardo called exchangeable values, relative values, or simply values) between commodities

(what Ricardo called exchangeable values, relative values, or simply values) between commodities  reads:

reads:

(3.1) |

with Vij the relative price of i in terms of j.

Stating that a monetary economy is a market economy in which transactions operate through a means of exchange M amounts to replacing j in (3.1) by M. The condition of coherence of the price system becomes:

(3.2) |

Since  is the money price of i and VnM the reciprocal of the value of money in terms of commodity n, (3.2) makes sense of the above quotation from the letter to Trower of 18 September 1818: “shoes [i] may continue unaltered in price

is the money price of i and VnM the reciprocal of the value of money in terms of commodity n, (3.2) makes sense of the above quotation from the letter to Trower of 18 September 1818: “shoes [i] may continue unaltered in price  , but both shoes, and gold (or money [M]) will have risen in value [in terms of n, that is, respectively

, but both shoes, and gold (or money [M]) will have risen in value [in terms of n, that is, respectively  and

and

Calling  and

and  the (money) prices

the (money) prices  and

and  of respectively i and n in (3.2), one obtains another expression of the condition of coherence of the price system:

of respectively i and n in (3.2), one obtains another expression of the condition of coherence of the price system:

(3.3) |

In a monetary economy, the value of commodity i in terms of commodity n (the relative price of i in terms of n) is equal to the ratio of the (money) price of i to the (money) price of n.

In Ricardo’s approach, the theory of value determines the relative prices of commodities independently of money –  is “real” and money is neutral in respect to relative prices – while the theory of money determines the value of money. To integrate money in the theory of value is to determine the value of money in a way consistent with the theory of relative prices of commodities – that is, allowing the money prices

is “real” and money is neutral in respect to relative prices – while the theory of money determines the value of money. To integrate money in the theory of value is to determine the value of money in a way consistent with the theory of relative prices of commodities – that is, allowing the money prices  and

and  to fulfil the condition (3.3) of coherence of the price system. However, nothing in this condition specifies what money is, and how its value is determined. To do this one needs first clarifying what is meant by value of money in Ricardo, all the more so since there are some ambiguities on this point in modern literature.

to fulfil the condition (3.3) of coherence of the price system. However, nothing in this condition specifies what money is, and how its value is determined. To do this one needs first clarifying what is meant by value of money in Ricardo, all the more so since there are some ambiguities on this point in modern literature.

3.2 Value of money, price of gold bullion, and the general price level

The legal and the current value of money

By fixing a given weight of the standard metal (say, gold) as the legal definition of the monetary unit (say, the pound sterling), the State not only fixes the legal value of money in terms of gold. By declaring legal tender this weight in coin (say, the sovereign), it also fixes the legal purchasing power of the currency in terms of all other commodities, for given prices of them denominated in pounds. However, this is only the legal side of the story. It had been recognised for long that, in actual circulation, the current value of the currency could depart from its legal one. In the sixteenth century “voluntary values” of coins were distinguished from their “legal values”, meaning that a given coin would actually pass for a higher amount of the monetary unit than the one decreed by the State (see Boyer-Xambeu, Deleplace and Gillard 1994a). Although this practice had since disappeared, thanks mostly to the prohibition of foreign coins in circulation, the question of the actual current value of the currency remained, as shown by the debates raised in England by the debasement of the coin, in the 1690s for the silver one and in the 1770s for the gold one. The Bullion Controversy of 1809‒1811 also raised this issue, this time for the inconvertible Bank of England note. An aspect of these repeated debates was the question of how this current value of the currency should be ascertained. Steuart (1767) had established that the debasement of the coin by wear and tear or clipping led to a rise in the market price of the standard metal in bullion over and above its legal price in full-bodied coin (see Deleplace 2015d). The spread between these two prices was consequently an index of the difference between the legal and the current value of the currency.

This was not the only manifestation of a change in the value of the currency. In the market for all other commodities than bullion, money prices also experienced variations, and if they all changed in the same direction and the same proportion, this signalled an opposite change in the current value of money in terms of commodities. The question was thus: which expression of the current value of money was appropriate, its purchasing power in terms of bullion or in terms of all other commodities?

A related question was how much of the rise in the money prices of commodities in general was reflected in the rise in the money price of bullion. This was a distinct question. One thing is to ask whether the agreed fact of a rise in the money price of gold bullion above the legal price of gold in coin should be explained by a monetary cause – such as the debasement of the coin or the excess issue of notes – or by other independent causes – such as a deficit of the foreign balance. This was the main issue debated during the Bullion Controversy in 1809‒1811. Another thing is to ask whether the change in the money price of gold bullion accurately reflected the change in prices of other commodities. This would be the main issue debated around the resumption of convertibility in 1819‒1823, this time in the context of falling prices, and not of rising prices as in 1809‒1811. Ricardo contended in 1819‒1823 that the appreciation of the Bank of England note only accounted for half of the rise in the value of money, which itself accounted for only a small part of the fall in the money prices of some commodities, such as agricultural products. This suggests that the definition of the value of money in Ricardo is something to be clarified, all the more so since the literature provides conflicting views on this question.

The purchasing power of money over all commodities except gold or over gold alone

Ambiguities in modern literature

In spite of a shift of emphasis on the questions raised by Ricardo, his definition of the value of money remained the same from the Bullion Essays until the end. However, there are in the literature some ambiguities on this definition, which concern the relation between money prices of commodities in general – in modern terms the general price level – and the money price of the particular commodity acting as the standard of money, gold bullion. Some modern commentators of Ricardo contend that, in the absence of the concept of general price level, Ricardo used the money price of gold bullion as a proxy of it. The following examples illustrate this interpretation, without being exhaustive:

To some extent Ricardo and his contemporaries focused in their formal discussions on the price of bullion and the foreign exchanges rather than the general price level because, while they knew something was happening to prices, there existed no consensus regarding the method of index numbers whereby the behavior of groups of commodities might be evaluated; at best only intelligent guesses could be made regarding general prices.

(Hollander 1979: 416; Hollander’s emphasis)

[In High Price, Ricardo] concentrated on giving an exceptionally clear statement of the nature of the long run equilibrium relationship that rules between the quantity of paper money, the exchange rate and the price of specie (which, as Hollander (1979) persuasively argues, is to be understood in this context as standing as a proxy for what we would now term the general price level).

(Laidler 1987: 291)

Ricardo led the Bullionists with the argument that the Bank [of England] had overissued and that this was the cause of inflation or, to use the language of the day, the cause of ‘the depreciation of bank notes’. In the absence of any confidence in the then little-used tool of an index-number of prices, the first problem was to prove that British prices had risen relative to other trading countries. Ricardo’s test was the premium actually quoted on bullion.

(Blaug 1996: 128)

In contrast, other commentators rightly emphasise the existence of a conceptual distinction in Ricardo between the general price level and the price of gold bullion, but insist that Ricardo deliberately defined the value of money as its purchasing power over gold bullion, not over all commodities taken together. The following example illustrates this position:

Ricardo distinguished between variations in the value of money and variations in money prices, emphasising that the value of money was measured by the purchasing power of the currency over the commodity which acted as a standard, and not by its purchasing power over all commodities. Thus the depreciation of currency was proved by an increase in the price of the standard, rather than by an increase in money prices.

(Marcuzzo and Rosselli 1991: 41)2

Another example is to be found in Takenaga (2013), where the distinction between two definitions of the value of money is rooted in another distinction between the nature of money – gold as a commodity, which has a value in terms of all other commodities – and institutional forms of money representing gold (coin, convertible note, inconvertible note), the value of which is their purchasing power in terms of the “true” money, gold. According to Takenaga, as long as the value of gold as a commodity was supposed to vary little, the stability of the value of a given form of money in terms of gold – the reciprocal of the money price of gold bullion – was the same as the stability of the value of money in terms of commodities, and the former stood practically for the latter.

Ricardo’s definition

Whether the price of gold bullion is a proxy by default of the general price level or fits the analytical requirements of an adequate expression of the value of money, both interpretations thus consider that for Ricardo a fall in the value of money was not expressed by a rise in the general price level but by a rise in the sole money price of gold bullion. This apparently accords with the title of Ricardo’s celebrated pamphlet of 1810‒1811 – The High Price of Bullion, a Proof of the Depreciation of Bank Notes – but is contradicted by Ricardo’s repeated distinction, during the debates in Parliament in 1819‒1823, between a fall in the value of money and a depreciation of money, as in the following extract of a speech on 12 June 1822:

The great mistake committed on this subject was in confounding the words “depreciation” and “diminution in value.” With reference to the currency, he [Ricardo] had said, and he now repeated it, that the price of gold was the index of the depreciation of the currency, not the index of the value of the currency, and it was in this that he had been misunderstood.

(V: 203‒4)3

In a letter to Malthus of 16 December 1822 Ricardo was also clear:

Dr. Copplestone in his article in the Quarterly Review charges me with maintaining the absurd doctrine that the price of gold bullion is a sure test of the value of bullion and currency.

(IX: 249)

And in a speech of 7 May 1822 he emphasised that there could be depreciation while the value of money was actually rising (more on this below in Chapter 4):

It might so happen that a currency might be depreciated, when it had actually risen, as compared with commodities, because the standard might have risen in value in a still greater proportion.

(V: 166)

A further example of the equivalence between an increase in the value of money and a general fall in prices is to be found in a letter to Malthus of 28 September 1821, where Ricardo discussed the case of a country where corn is supposedly produced with half the labour required in all others, which consequently import the corn and pay it in money:

As part of their exports in return for corn must in the first instance be money – the general level of currency will be reduced and commodities generally will fall, not because they can be produced cheaper, but because they are measured by a more valuable money.

(IX: 81)

One should note that the expression “level of money” or “level of the currency” (used several times in the letter) does not mean here the general price level but the aggregate quantity of money, which decreases in the countries importing corn because the latter is paid in money. The consequence is “a more valuable money”, hence a general fall in prices (“commodities generally will fall”).4

Indeed, that the value of money had to be ascertained by the price of all commodities taken together was already stated in High Price, and it was repeated in Principles:

Commodities measure the value of money in the same manner as money measures the value of commodities.

(High Price; III: 104)

The advance in the value of money is the same thing as the decline in the price of commodities.

(Principles; I: 342)

To say that commodities are raised in price, is the same thing as to say that money is lowered in relative value; for it is by commodities that the relative value of gold is estimated.

(ibid: 105)

The latter extract is part of Ricardo’s discussion of the possibility – rejected by him – of a general rise in prices as a consequence of a rise in wages, and he here assumed that the value of money was equal to the value of gold bullion – a situation corresponding to an absence of depreciation or appreciation of the currency. It was then equivalent to say that “commodities are raised in price”, “money is lowered in relative value”, and “the relative value of gold” declined. A logical consequence ensued: not only the price of gold bullion was “not the index of the value of the currency” as stated above, but it should not be included among the prices of commodities in general constituting such index. The value of money was thus defined as its purchasing power over all commodities except the standard.

A further indication that this was Ricardo’s definition of the value of money is to be found in his repeated contention that the value of money ought to conform to the value of bullion – a condition which would not make sense if the value of money were defined as its purchasing power over bullion since it would always be equal to unity. This condition of conformity, which appeared in Proposals, played a central role in Ricardo’s mature theory of money.

The condition of conformity of money to the standard

This condition was one of the three characteristics of “a perfect currency” as they were mentioned in Proposals:

A currency may be considered as perfect, of which the standard is invariable, which always conforms to that standard, and in the use of which the utmost economy is practised.

(Proposals; IV: 55)

With gold or silver as the standard, the conformity of money to the standard meant for Ricardo that a given weight of the metal in money (whether coin or convertible note) was of equal value with the same weight of the metal in bullion, both values being in terms of all commodities except the standard. A corollary was that the market price of bullion should be equal to the legal price of the metal in coin (the mint price). If it was higher, money was less valuable than bullion:

While these metals [gold and silver] are the standard, the currency should conform in value to them, and, whenever it does not, and the market price of bullion is above the mint price, the currency is depreciated. This proposition is unanswered, and is unanswerable.

(ibid: 62‒3)

And symmetrically:

To say that money is more valuable than bullion or the standard, is to say that bullion is selling in the market under the mint price.

(ibid: 57)

That the inequality between the value of money and the value of the standard could be expressed by an inequality of opposite direction between the market price of gold bullion and the legal price of gold in coin was repeated by Ricardo when he was examined on 4 March 1819 by the Commons’ Secret Committee on the Expediency of the Bank resuming Cash Payments. Being asked “Do you consider the high price of gold to be a certain sign of the depreciation of bank notes?”, he answered:

I consider it to be a certain sign of the depreciation of bank notes, because I consider the standard of the currency to be bullion, and whether that bullion be more or less valuable, the paper ought to conform to that value, and would, under the system that we pursued previously to 1797.

(V: 373)

This correspondence between a comparison in value and a comparison in price to establish the conformity of money to the standard may be demonstrated by using the formalisation presented in Section 3.1 above.

Let me call R a composite commodity, each unit of it being constituted of all transacted commodities (except gold bullion) in the proportions in which they appear in transactions. In the condition (3.2) of coherence of the price system, replacing i by R and n by gold bullion G gives:

(3.4) |

In this equation,  is the reciprocal of

is the reciprocal of  the value of money defined as the purchasing power of a unit of money over all commodities except the standard (gold bullion),

the value of money defined as the purchasing power of a unit of money over all commodities except the standard (gold bullion),  is the reciprocal of

is the reciprocal of  , the value of gold bullion in terms of all other commodities, and

, the value of gold bullion in terms of all other commodities, and  is the value of gold bullion in terms of money, that is its money price. (3.4) may thus be turned into:

is the value of gold bullion in terms of money, that is its money price. (3.4) may thus be turned into:

(3.5) |

As mentioned above, (3.5) only expresses that the prices at which the composite commodity R and gold bullion G exchange for money are coherent with the (real) relative price  of gold bullion in terms of commodity R, as it is determined by the theory of value. However, nothing in (3.5) specifies what money is, apart from the fact that it is the medium of exchange. In order to build a monetary theory, one should now add that money is also “the medium in which price is always expressed”, as quoted above from Principles, that is, the unit of account legally fixed. As mentioned in Section 3.1 above, this unit of account (say, the pound) was defined through the legal proclamation of a fixed price of the standard (say, gold bullion) in the form of money (say, a given coin, such as the sovereign). Money is thus specified by its relation to the standard, that is, the legal price of the standard in money.5 Let me call

of gold bullion in terms of commodity R, as it is determined by the theory of value. However, nothing in (3.5) specifies what money is, apart from the fact that it is the medium of exchange. In order to build a monetary theory, one should now add that money is also “the medium in which price is always expressed”, as quoted above from Principles, that is, the unit of account legally fixed. As mentioned in Section 3.1 above, this unit of account (say, the pound) was defined through the legal proclamation of a fixed price of the standard (say, gold bullion) in the form of money (say, a given coin, such as the sovereign). Money is thus specified by its relation to the standard, that is, the legal price of the standard in money.5 Let me call  this legal price in pounds of an ounce of gold in coin. The legal value

this legal price in pounds of an ounce of gold in coin. The legal value  of money in terms of gold may thus be defined as:

of money in terms of gold may thus be defined as:

(3.6) |

In other words, gold bullion, which in Ricardo’s terms is in (3.4) the standard of value – in which all (real) relative prices are expressed – becomes in (3.6) the standard of money – in which the monetary unit is expressed.

Ricardo’s condition of conformity may consequently be interpreted as follows: money conforms to the standard when its value  as medium of exchange – that is, its circulating value in terms of all commodities except the standard – is consistent with its value

as medium of exchange – that is, its circulating value in terms of all commodities except the standard – is consistent with its value  as unit of account – that is, its legal value in terms of the standard. This condition is fulfilled when

as unit of account – that is, its legal value in terms of the standard. This condition is fulfilled when  in (3.5) is equal to

in (3.5) is equal to  Let me call

Let me call  the value of money in terms of R for which this equality applies. One obtains:

the value of money in terms of R for which this equality applies. One obtains:

(3.7) |

Replacing  by its definition in (3.6) gives:

by its definition in (3.6) gives:

(3.8) |

Equation (3.8) expresses the condition of conformity of money to the standard as an equality between the value of money in circulation and the value of the standard (both in terms of all commodities except the standard), given the legal price of the standard. As it is, (3.8) embodies the second condition for what Ricardo called “a perfect currency” in the above quotation from Proposals, but it is hardly useful to determine whether an actual currency conforms to the standard because it requires the knowledge of two magnitudes measured in terms of R.6 This difficulty, called later in the literature the index-number problem, was not addressed by Ricardo: the modern expression of the general price level – as a weighted average of the money prices of individual commodities – is not to be found in his writings (as shown below in Section 3.3, Ricardo’s search for an invariable standard answered to another question), although he used the expressions of “the general price of goods” (I: 169) or of “the mass of prices” (III: 299). And Ricardo had good reasons not to look for an index-number: he could leave this difficulty aside, because there was another expression of the condition of conformity. Since this condition is fulfilled when  in (3.5) is equal to

in (3.5) is equal to  – in other words when

– in other words when  – and since

– and since  is the market price

is the market price  of gold bullion, one obtains:

of gold bullion, one obtains:

(3.9) |

This was Ricardo’s first tour de force in his monetary theory: the condition of conformity of money to the standard was to be expressed as an equality between two observable magnitudes, the market price of gold bullion and the legal price of gold in coin. Ricardo’s concern with the stabilisation of the market price of gold bullion had thus nothing to do with the stabilisation of a proxy of the general price level: the market price of gold was to be stabilised at its legal level because this meant that money was actually conforming to its legal standard.

In what follows, I will assume that the reader is aware of the fact that the value of money and the value of the standard (gold bullion) are both defined in terms of all commodities except the standard, and I will simplify  and

and  into respectively

into respectively  . Substituting

. Substituting  for

for  as the market price of gold bullion and recalling that

as the market price of gold bullion and recalling that  is the legal price of gold in coin, the main relations analysed above read:

is the legal price of gold in coin, the main relations analysed above read:

Condition of coherence of the price system:

(3.5) |

Condition of conformity of money to the standard:

(3.8) |

that is,

(3.9) |

We will see in Chapter 7 below that, thanks to convertibility of bullion into money and of money into bullion (money being whether coin or note), arbitrage ensures the fulfilment of (3.9), taking into account the costs incurred by convertibility both ways. In such “sound state of the currency” money conformed to the standard. According to Ricardo, money was depreciated if  and appreciated if

and appreciated if  (see Chapter 4 below). This was equivalent respectively to

(see Chapter 4 below). This was equivalent respectively to

Although the modern expression of the general price level did not appear in Ricardo, the notion was present when he referred to causes having “a general effect on price”, in contrast with causes affecting some commodities only or all commodities in a non-homothetic way, and thus responsible for a change in relative prices:

A rise in wages, from an alteration in the value of money, produces a general effect on price, and for that reason it produces no real effect whatever on profits. On the contrary, a rise of wages, from the circumstance of the labourer being more liberally rewarded, or from a difficulty of procuring the necessaries on which wages are expended, does not, except in some instances, produce the effect of raising price, but has a great effect in lowering profits. In the one case, no greater proportion of the annual labour of the country is devoted to the support of the labourers; in the other case, a larger proportion is so devoted.

(Principles, I: 48‒9; my emphasis)

This distinction between the general effect on “the mass of prices” of a change in the value of money and a particular effect on some prices due to other causes was already made by Ricardo at the time of the Bullion Essays, as when he discussed Bentham’s explanation of “the causes influencing the rise in prices”:

This is true taking all commodities together, – but fashion or other causes may create an increased demand for one article and consequently the demand for some one or more of others must diminish. Will not this operate on prices? The author [Bentham] evidently means all commodities together or the mass of prices.

(III: 298‒9; my emphasis)

Two remarks should be made before going further. The first is that a distinction is to be made between the definition of the value of money – as may now be clear, in terms of all commodities taken together except the standard of money – and the choice of the standard of money – for which Ricardo rejected this “mass of commodities” (Proposals; IV: 59; see below Section 3.3). The second remark is that, for reasons analysed at length below, Ricardo always stressed that, except in a situation like the one observed in 1810 – characterised by the inconvertibility of the Bank of England note and the quasi-disappearance of gold coins in domestic circulation – a change in the market price of gold bullion was constrained between narrow limits and temporary (it was self-adjusting), although the value of gold bullion could vary significantly and permanently. This was summarised in a compact form during his evidence of 4 March 1819 as follows:

In a sound state of the currency the value of gold may vary, but its price cannot.

(V: 392)

This meant that the value of money could change with the value of gold bullion, while the market price of gold bullion – the reciprocal of the value of money in terms of gold bullion – remained stationary. This should be remembered when discussing changes in the value of money (see Chapter 4 below).

A non-monetary cause of rise in the general price level? The question of taxation

We may now go back to the above-mentioned use by some commentators of the conceptual distinction between the general price level and the price of gold bullion to define the value of money in reference to the latter rather than the former. A reason advanced for this use is to account for Ricardo’s contention that, indeed, an excess quantity of paper money did generate a rise in the money prices of all commodities, but this was not the only possible cause of such rise. This contention is obviously at odds with that of modern advocates of the Quantity Theory of Money for whom inflation may only be caused by money being in excess, and, as we will see, it plays an important role in Ricardo’s theory of money. However, it does not require rejecting the definition of the value of money by its purchasing power over all commodities except the standard of money.

At the time of the Bullion Essays, Ricardo already distinguished what in the rise of prices could be ascribed to the depreciation of paper money – which he explained by its excess quantity – and to other causes – of a non-monetary character:

Eighteen per cent. is, therefore, equal to the rise in the price of commodities, occasioned by the depreciation of paper. All above such rise may be either traced to the effects of taxation, to the increased scarcity of the commodity, or to any other cause which may appear satisfactory to those who take pleasure in such enquiries.

(Reply to Bosanquet; III: 239)

One should remark that Ricardo speaks here of depreciation – not of a fall in the value of money – and that it is unclear whether the other causes of “the rise in the price of commodities” apply to some commodities or to all: “the increased scarcity” is that of “the commodity” (in the singular) and taxation may be general or particular. At that time, Ricardo was not yet equipped with the appropriate tools to deal with this kind of problem. Things changed with Principles. On the one hand, the contention that aggregate demand was regulated by aggregate supply – labelled Say’s Law in the literature – excluded a general rise or fall in prices caused by, respectively, a deficiency or a glut of all commodities.7 On the other hand, Ricardo could now analyse “the effects of taxation”, thanks to a proper theory of value and distribution. It is necessary here to say a few words on this theory, since it will have consequences at various levels for the theory of money.

As is well-known, the titles of Section IV and V of Chapter I “On value” of Principles are explicit as to the “modification” of the law that determines the exchange value of commodities by the relative quantity of labour necessary to their production:

The principle that the quantity of labour bestowed on the production of commodities regulates their relative value, [is] considerably modified by the employment of machinery and other fixed and durable capital.

(Principles; I: 30)

The principle that value does not vary with the rise or fall of wages, [is] modified also by the unequal durability of capital, and by the unequal rapidity with which it is returned to its employer.

(ibid: 38)

As mentioned by Sraffa quoting a letter from Ricardo to McCulloch of 13 June 1820:

Ricardo had suggested that ‘all the exceptions to the general rule’ could be reduced to ‘one of time’: i.e. all those deriving from different proportions of fixed and circulating capitals, different durabilities of fixed capital, or differences in the ‘time it takes to market’ (or durability of circulating capital) could be reduced to terms of labour employed for a longer or a shorter time.

(Sraffa 1951a: xlv)

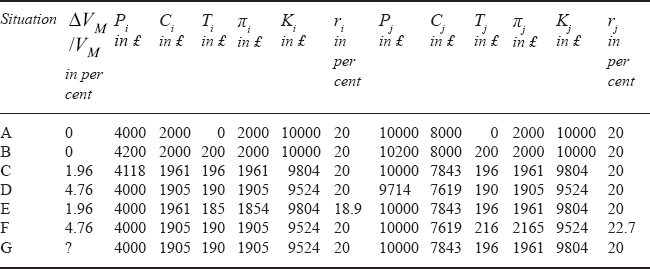

Before analysing the consequences of the taxation of profits, Ricardo summed-up this effect on relative prices created by the unequal length with which capital is advanced to produce commodities and bring them to market:

In a former part of this work, we discussed the effects of the division of capital into fixed and circulating, or rather into durable and perishable capital, on the prices of commodities. We shewed that two manufacturers might employ precisely the same amount of capital, and might derive from it precisely the same amount of profits, but that they would sell their commodities for very different sums of money, according as the capitals they employed were rapidly, or slowly, consumed and reproduced.

(Principles; I: 207)

It is not the place here to discuss the implications of such “modification” of the labour theory of value; there is an extended literature on this question. All we need is to emphasise the uncontroversial result that a change in the rate of profit or in the wage rate – these two distributive variables being inversely related – affects relative prices because of differences between commodities as to the durability of capital advanced in their production. This is enough to derive the effects of taxation, and consequently to inquire whether it can be another cause of change in the general price level, independent of the effect of a change in the value of money.

Leaving aside taxation levied on particular activities or commodities – which obviously alters relative prices – there are two kinds of taxation that may be levied at a uniform rate on all activities or commodities, and hence be eligible as cause of change in the general price level: taxes on incomes, and taxes on the production or on the sale of commodities. Taxes on profits and on wages (analysed respectively in Chapters XV and XVI of Principles) both affect the level of these distributive variables8 and trigger the above-mentioned “modification” of the law of value – namely a change in relative prices:9

A tax upon income, whilst money continued unaltered in value, would alter the relative prices and value of commodities. This would be true also, if the tax instead of being laid on the profits, were laid on the commodities themselves: provided they were taxed in proportion to the value of the capital employed on their production, they would rise equally, whatever might be their value, and therefore they would not preserve the same proportion as before.

(ibid: 208)10

Taxes on the production or on the sale of commodities (“a tax on the produce when obtained;” ibid: 156) are analysed in Chapter IX “Taxes on raw produce” and Chapter XVII “Taxes on other commodities than raw produce” of Principles. They amount to increasing the cost of production of commodities and as such affect all prices inasmuch as these commodities enter directly or indirectly in the production of all of them – in Sraffa’s terms these commodities are “basic products” (Sraffa 1960: 8) – but they alter the methods of production and consequently affect relative prices. In all cases, the theory of value and distribution developed in Principles leads to the conclusion that taxation, even at the same rate in all industries, generates a change in the relative prices of commodities:

Taxation can never be so equally applied, as to operate in the same proportion on the value of all commodities, and still to preserve them at the same relative value.

(Principles; I: 239)

Before concluding on this point, one may mention a curiosity concerning the relation between taxation and the value of money. Not only did Ricardo rightly contend that taxation altered relative prices, but he went as far as suggesting that, because of this effect, a change in the value of money also altered relative prices, in a country where profits were taxed. In Chapter XV “Taxes on profits” of Principles, Ricardo focused on “the understanding of a very important principle, which, I believe, has never been adverted to” (ibid: 208). This principle was that, in contrast with “a country where no taxation subsists”, “in a country where prices are artificially raised by taxation [of profits]” a change in the value of money “will not operate in the same proportion on the prices of all commodities” (ibid: 209). This “very important principle” – the discovery of which Ricardo attributed to himself – raises two questions, one analytical, the other historical. From an analytical point of view, the question is that of the effect of a change in the value of money on relative prices: in modern parlance, Ricardo unexpectedly contended that a taxation of the profits of capital turned the neutrality of money in respect to relative prices into non-neutrality. From a historical point of view, Ricardo suggested that this “very important principle” not only applied to a hypothetical case but might explain what materially happened when money was depreciated during the period of inconvertibility of the Bank of England note. However, the study of the numerical example used by Ricardo to establish this point does not validate the conclusion he drew from it. This may thus be considered as an aborted attempt at the non-neutrality of money in respect to relative prices (see Appendix 3).

I may now conclude on the question of the definition of the value of money. Ricardo’s analysis in Principles shows that taxation, which alters relative prices, cannot be considered as a cause of change in the general price level, defined as an equiproportional change in all money prices. It is not even possible to say that taxation generates a rise in all money prices, although in different proportions, since the prices of some commodities may actually fall, as a consequence of the effect produced by the difference between durabilities of capital in the production of these commodities and of the standard of money (see below Section 3.3). In other words, taxation does not call for a distinction between a change in the value of money and a change in the general price level in the opposite direction: they are one and the same thing, provided the price of the standard of money is excluded from the general price level. Now, does this conclusion contradict Ricardo’s contention that an excess quantity of paper money generates a rise in the money prices of all commodities, but that this is not the only possible cause of such rise? Not at all, provided we keep in mind the above-mentioned distinction, emphasised by Ricardo in his papers of 1819‒1823, between a depreciation of money and a fall in the value of money.

Depreciation, consequent upon the quantity of money being in excess, was indeed one cause of a fall in the value of money, defined as an equiproportional rise in money prices of all commodities except the standard of money. Symmetrically, an appreciation of money, consequent upon the quantity of money being deficient, was one cause of a rise in the value of money, defined as an equiproportional fall in money prices of all commodities except the standard of money. However, there was another possible cause of a change in the value of money so defined: not taxation – which altered relative prices – but a change in the value of the standard itself. Ricardo’s contention remains perfectly valid: not every rise in the general price level should be attributed to an excess of paper money; but there is only one other cause of such rise and it is a fall in the value of the standard, gold bullion. In both cases it is equivalent to say that the prices of all commodities (except the standard) rise in the same proportion and that the value of money falls by this proportion. But in one case (depreciation) the cause is an excess quantity of money while in the other the cause is real: a fall in the value of the commodity acting as the standard of money.

The notion of standard appears then central in Ricardo’s theory of money, and in Principles Ricardo developed a theory of value and distribution that allowed him to analyse its properties, as the next section will show.

3.3 The standard of money and the standard of value

It is widely recognised that the question of the invariable standard is an integral part of Ricardo’s theory of value and distribution. I will contend that it is also an integral part of his theory of money. On this question, the evolution of the former had indeed a disappointing effect on the latter: the more Ricardo dug into the invariable standard of value, the more the possibility of an invariable standard of money moved away. However, here also, the theory of value and distribution contained in Principles contributed to the clarification of the question of the value of money.

The word “standard” appears in Ricardo with two different meanings: standard of money (or of currency) and standard of value. The former pervades all monetary writings, from the Bullion Essays to Plan for a National Bank, while the latter emerged with Ricardo’s interest for the issue of value and distribution and was the object of the last manuscript interrupted by his death in 1823. The link between these two meanings is provided by the fact that money is the measure of price and by their having both something to do with the question of invariability. They are consequently often confused by Ricardo under the name of “gold”, although he carefully made the distinction between them. An indication of this distinction is to be found in Sraffa’s Index of Works (Vol. XI). The only specific entry for the word “standard” is “standard of currency”, which is half a column long (mainly overlapping with “standard of” in the entry “money”). However, in the entry “value”, two full columns are devoted to “measure or standard of”. This disproportion might reflect Sraffa’s own interest for this question, but it should be noted that, while the entry “standard of currency” contains references to writings of all periods, the longer sub-entry “Value: measure or standard of” has only two references prior to the publication of Principles.11

The invariable standard of value: “a mean between the extremes”

Invariable standard and absolute values

The search for an invariable standard of value was for Ricardo an integral part of his theory of value and distribution. As Sraffa put it, this search aimed at “finding the conditions which a commodity would have to satisfy in order to be invariable in value – and this came close to identifying the problem of a measure with that of the law of value” (Sraffa, 1951a: xli), since “the idea of an ‘invariable measure’ has for Ricardo its necessary complement in that of ‘absolute value’” (ibid: xlvi). This question is well-documented in the literature (see for example Sraffa 1951a; Kurz and Salvadori 2015a, and on the controversy between Malthus and Ricardo on the measure of value, Porta 1992a) and it is consequently not necessary here to deal with it in detail.

A special Section VI, entitled “On an invariable measure of value” was introduced in Chapter I “On value” of Principles for the third edition of 1821, and Ricardo’s last manuscript, interrupted by his death on 11 September 1823, was devoted to the analysis of this invariable standard of value; it was entitled “Absolute Value and Exchangeable Value”. The absolute value of a commodity was defined by Ricardo as its exchangeable value in terms of an invariable standard of value. The need for and at the same time the impossibility of such standard was explained by Ricardo in Principles as follows:

When commodities varied in relative value, it would be desirable to have the means of ascertaining which of them fell and which rose in real value, and this could be effected only by comparing them one after another with some invariable standard measure of value, which should itself be subject to none of the fluctuations to which other commodities are exposed. Of such a measure it is impossible to be possessed, because there is no commodity which is not itself exposed to the same variations as the things, the value of which is to be ascertained.

(Principles; I: 43‒4)

This contradiction between the necessity of having an invariable standard of value and the impossibility of finding one would again obsess Ricardo after Principles, as testified by the manuscript “Absolute Value and Exchangeable Value”:

It can not be too often repeated that nothing can be a measure of value which is not itself invariable.

(IV: 394; see also, ibid: 401)

It must then be confessed that there is no such thing in nature as a perfect measure of value.

(ibid: 404)

In the absence of a perfect standard of value, it would nevertheless be desirable if an agreement could be made on the least imperfect one:

What are we to do in this difficulty, are we to leave every one to chuse his own measure of value or should we agree to take some one commodity and provided it were always produced under the same circumstances constitute that as a general measure to which we should all refer that we may at least understand each other when we are talking of the rise or fall in the value of things.

(ibid: 371‒2)

The difficulty being stated, the question is how it shall be best overcome, and if we cannot have an absolutely uniform measure of value what would be the best approximation to it?

(ibid: 381)

As the first quotation makes clear, Ricardo started by raising this question of invariability in respect to time (“provided it were always produced under the same circumstances”), that is, “at distant periods”:

It is a great desideratum in Polit. Econ. to have a perfect measure of absolute value in order to be able to ascertain what relation commodities bear to each other at distant periods. Any thing having value is a good measure of the comparative value of all other commodities at the same time and place, but will be of no use in indicating the variations in their absolute value at distant times and in distant places.

(ibid: 396)

One should thus lean on the permanent causes that rendered commodities variable in value, so as to choose the commodity that was the least affected by them.12 As analysed in Chapter I of Principles there were two such causes: a change in the quantity of labour necessary for their production and a change in the distribution between wages and profits (which were inversely related). The second cause “modified” the effect of the first and, as mentioned above in Section 3.2, it operated because of the unequal durability of the capital advanced in the production of the various commodities. However, Ricardo observed that:

This cause of the variation of commodities is comparatively slight in its effects, [which] could not exceed 6 or 7 per cent.; for profits could not, probably, under any circumstances, admit of a greater general and permanent depression than to that amount.

(Principles; I: 36; see also “a minor variation”, ibid: 42)

Consequently, the constancy in the quantity of labour required in the production was the main criterion for the choice of the standard:

I have already remarked, that the effect on the relative prices of things, from a variation in profits, is comparatively slight; that by far the most important effects are produced by the varying quantities of labour required for production; and therefore, if we suppose this important cause of variation removed from the production of gold, we shall probably possess as near an approximation to a standard measure of value as can be theoretically conceived.

(ibid: 45)

As is well-known, this concession made by Ricardo on the effect of a change in wages on relative prices – an effect he emphatically rejected in the generality of cases – has given birth to the ironical label of a “93% Labour Theory of Value” (Stigler 1958). But it should be remarked that this argument of “slight effect”, however feeble it may look, does not play any role in Ricardo’s analysis of the criterions of choice of the standard. The previous quotation goes on as follows:

May not gold be considered as a commodity produced with such proportions of the two kinds of capital as approach nearest to the average quantity employed in the production of most commodities? May not these proportions be so nearly equally distant from the two extremes, the one where little fixed capital is used, the other where little labour is employed, as to form a just mean between them?

(Principles; I: 45‒6)

The argument here is no longer that we may neglect the effect of a change in distribution on relative prices because the observed small variations in the rate of profit made it “slight”, but that, whatever these variations, they would be of no consequence on the capacity of the standard to measure adequately the absolute values of commodities, provided it were “a just mean” between these commodities. The reason is that, although relative prices of commodities vary with distribution, as a consequence of the unequal durability of capital advanced in their production, this effect is eliminated for commodities produced with the same durability of capital. The second cause of variability of a standard thus disappears whenever this standard is used to measure the value of the commodities produced with the same durability of capital:

It would be a perfect measure of value for all things produced under the same circumstances precisely as itself, but for no others.

(ibid: 45; see also “Absolute Value”; IV: 386‒7)

This argument reflects a shift of emphasis in the question of the variability of the standard, from changes occurring “at distant periods” – that is, through time (in dynamics) – to variations in the levels of the distributive variables at a point in time (in comparative statics).

A shift of emphasis

To understand this shift, one needs to go back to Ricardo’s theory of the rate of profit. In An Essay on the Influence of a low Price of Corn on the Profits of Stock (generally referred to as the Essay on Profits), published in 1815, Ricardo suggested that the level of the rate of profit depended on the ratio of the quantity of corn produced in the economy to the quantity of corn consumed in this production. This “corn-ratio theory of profits”, as it was called by Sraffa (1951a: xlix), provided the cornerstone of the relationship between the rate of profit, wages, and the price of wage-goods, developed two years later in Principles. As Sraffa put it:

[I]t was now labour, instead of corn, that appeared on both sides of the account – in modern terms, both as input and output: as a result, the rate of profits was no longer determined by the ratio of corn produced to the corn used up in production, but, instead, by the ratio of the total labour of the country to the labour required to produce the necessaries for that labour.

(ibid: xxxii)

There was, however, a difficulty: the differences between commodities as to the durability of the capital advanced in their production made exchangeable values depend on the rate of profit, generating a circular reasoning: the distribution of the aggregate surplus, measured in value, affected the size of the surplus to be distributed. Hence there was a need for a measure of the value of commodities that would be invariable in respect to variations in distribution and would turn exchangeable values measured in a variable standard into absolute values measured in an invariable one. As Sraffa put it:

[T]hus the problem of value which interested Ricardo was how to find a measure of value which would be invariant to changes in the division of the product; for, if a rise or fall of wages by itself brought about a change in the magnitude of the social product, it would be hard to determine accurately the effect on profits. (This was, of course, the same problem as has been mentioned earlier in connection with Ricardo’s corn-ratio theory of profits.)

(ibid: xlviii‒xlix)

This use of the standard of value to analyse the relationship between wages and the rate of profit is summed-up in Principles for a particular case as follows:

If we had an invariable standard by which to measure the value of this produce, we should find that a less value had fallen to the class of labourers and landlords, and a greater to the class of capitalists, than had been given before.

(Principles; I: 49)

The selection of the appropriate standard for that use was thus subject to two criteria: (a) it should always require the same quantity of labour for its production – a correction being applied in case this quantity changed; and (b) the durability of the capital advanced in its production should be a “mean between the extremes” of the commodities composing the aggregate product to be distributed – this mean being supposed to be one year:

To me it appears most clear that we should chuse a measure produced by labour employed for a certain period, and which always supposes an advance of capital, because 1st. it is a perfect measure for all commodities produced under the same circumstances of time as the measure itself – 2dly. By far the greatest number of commodities which are the objects of exchange are produced by the union of capital and labour, that is to say of labour employed for a certain time. 3dly. That a commodity produced by labour employed for a year is a mean between the extremes of commodities produced on one side by labour and advances for much more than a year, and on the other by labour employed for a day only without any advances, and the mean will in most cases give a much less deviation from truth than if either of the extremes were used as a measure.

(“Absolute Value”; IV: 405)

There was a fourth characteristic that would make the chosen standard suitable: this “mean between the extremes” would be “a perfect measure” for wage-goods produced by agriculture – that is, most of the goods consumed by workers – supposing that they were also produced with capital advanced during one year. The quotation went on as follows:

Let us suppose money to be produced in precisely the same time as corn is produced, that would be the measure proposed by me, provided it always required the same uniform quantity of labour to produce it, and if it did not provided an allowance were made for the alteration in the value of the measure itself in consequence of its requiring more or less labour to obtain it. The circumstance of this measure being produced in the same length of time as corn and most other vegetable food which forms by far the most valuable article of daily consumption would decide me in giving it a preference.

(ibid: 405‒6)

This “preference” was consistent with Ricardo’s theory of the rate of profit as being inversely related to the prices of wage-goods. Since the chosen standard (here called “money” for reasons that will be explained below) is supposed to be produced with the same durability of capital as most of the wage-goods, it may be used to measure the changes in their prices independently of the rate of profit – hence the change in wages and the consequent change in the rate of profit itself.

In spite of these precisions contained in the manuscript “Absolute Value” as compared with Principles, Ricardo was disappointed by the outcome of his enquiry into that issue. His last letter of 5 September 1823 – the day, as Sraffa put it, when he “was struck with his fatal illness” – and addressed to James Mill ended as follows:

I have been thinking a good deal on this subject lately but without much improvement – I see the same difficulties as before and am more confirmed than ever that strictly speaking there is not in nature any correct measure of value nor can any ingenuity suggest one, for what constitutes a correct measure for some things is a reason why it cannot be a correct one for others.

(IX: 387)13

What was the reason of this disappointment? The writing of the manuscript “Absolute Value” having been interrupted by Ricardo’s death, one may only conjecture about it. One reason may be the intuitive consciousness of a difficulty that only became apparent with Sraffa’s development of Ricardo’s search for an invariable standard in his book Production of Commodities by Means of Commodities (1960). As is well-known, Sraffa’s standard commodity is a composite one, constructed on the basis of the given methods of production of actual “basic commodities” combined in adequate proportions. Kurz and Salvadori (2015a) observe that Ricardo “did not take the composite commodity ‘social product’, or, in his terms, the ‘mass of commodities’, as the standard of value”, because “in the context of a discussion of the impact of distribution on relative value, given the technical conditions of production, […] it does not meet with the criterion of technological invariability”, since many commodities composing the product experienced technological change (Kurz and Salvadori 2015a: 210). It may be added that, even if a single commodity were adopted as the invariable standard in respect to distribution because it was at one time “a mean between the extremes” computed on the basis of given techniques of production (durability of capital), it could hardly be used also to measure variations in the absolute values of the commodities through time, hence with heterogeneous changes in the techniques of production that implied a change in the “mean” itself.

Another reason – more relevant for the present book – of Ricardo’s disappointment may be suggested. It was the link between the standard of value and the standard of money.

The link with the standard of money

In Ricardo’s view, the standard of value was indeed an instrument in the hands of the “Political Economist” (“Absolute Value”; IV: 404) to make real changes in absolute values visible under the apparent changes in exchangeable values (see above “It is a great desideratum in Polit. Econ. to have a perfect measure of absolute value”, ibid: 396; and also: “in Political Economy we want something more”, ibid: 375). But, as developed below, it was also to be an instrument to dissipate another source of variability in prices than changes in conditions of production and distribution: changes in the value of money. To do that, the standard of value should also be the standard of money.

This is a direction to which Sraffa himself pointed in Production of Commodities, where Appendix D “References to the literature” reads as follows: “The conception of a standard measure of value as a medium between two extremes (§ 17 ff.) also belongs to Ricardo1 and […] the Standard commodity […] has been evolved from it” (Sraffa 1960: 94). Footnote 1 attached to “Ricardo” directs the reader to Sraffa’s own introduction to his edition of Principles, where he wrote: “In edition 3 [of Principles], therefore, the standard adopted was money ‘produced with such proportions of the two kinds of capital as approach nearest to the average quantity employed in the production of most commodities’” (Sraffa 1951a: xliv). This excerpt from Ricardo’s third edition of Principles (I: 45) was in fact attached to “gold considered as a commodity”, and not to money as Sraffa writes, but this matters little since Ricardo himself ended up his argument saying:

To facilitate, then, the object of this enquiry, although I fully allow that money made of gold is subject to most of the variations of other things, I shall suppose it to be invariable, and therefore all alterations in price to be occasioned by some alteration in the value of the commodity of which I may be speaking.

(Principles; I: 46; my emphasis)

Under the assumption that gold bullion was both the standard of value and the standard of money, “price and value would be synonymous” for any commodity (“Absolute Value”; IV: 373), a statement to be understood as follows. Calling s the commodity selected as the invariable standard of value, the absolute value Vi of commodity i is defined by:

(3.10) |

Gold bullion being the standard of money, gold has two prices, a price PG in the market for bullion and a legal price  when coined. As seen above in equation (3.9), for Ricardo the value of money conformed to the value of the standard when these two prices were equal

when coined. As seen above in equation (3.9), for Ricardo the value of money conformed to the value of the standard when these two prices were equal  . Replacing commodity n in (3.3) by gold bullion and assuming that this condition of conformity is fulfilled gives:

. Replacing commodity n in (3.3) by gold bullion and assuming that this condition of conformity is fulfilled gives:

(3.11) |

Gold bullion being also by assumption the invariable standard of value, the absolute value of any commodity i is, according to (3.10):

(3.12) |

Hence:

(3.13) |

Since  is the definition of the monetary unit (the pound) in terms of gold, the absolute value of any commodity – that is, its exchangeable value in terms of gold bullion – is equal to its gold-price: “price and value [are] synonymous”. The relation between the standard of value and the standard of money should now be analysed in detail.

is the definition of the monetary unit (the pound) in terms of gold, the absolute value of any commodity – that is, its exchangeable value in terms of gold bullion – is equal to its gold-price: “price and value [are] synonymous”. The relation between the standard of value and the standard of money should now be analysed in detail.

The notion of invariable measure of value first appeared in High Price, in a note on a paragraph where Ricardo criticised the double standard of money:

No permanent* measure of value can be said to exist in any nation while the circulating medium consists of two metals, because they are constantly subject to vary in value with respect to each other.

*Strictly speaking, there can be no permanent measure of value. A measure of value should itself be invariable; but this is not the case with either gold or silver, they being subject to fluctuations as well as other commodities. Experience has indeed taught us, that though the variations in the value of gold or silver may be considerable, on a comparison of distant periods, yet for short spaces of time their value is tolerably fixed. It is this property, among their other excellencies, which fits them better than any other commodity for the uses of money. Either gold or silver may therefore, in the point of view in which we are considering them, be called a measure of value.

(High Price; III: 65; Ricardo’s emphasis)

Ricardo then felt content with the value of gold or silver being “tolerably fixed” in the short run, although it might change a lot in the long run. This was enough in his perspective at the time, which was to show that the recent fall in the value of money was to be ascribed to an excess quantity of inconvertible notes issued, not to a fall in the value of the precious metals. This was not a sign of short-sightedness. Another factor might explain this neglect for the possible effect of a change in the value of the standard on the value of money: Ricardo considered that, because the Bank of England note was inconvertible and gold coins had disappeared from circulation, the value of money (whether the note or the coin) was then no longer regulated by a standard:

That gold is no longer in practice the standard by which our currency is regulated is a truth. It is the ground of the complaint of the [Bullion] Committee (and of all who have written on the same side) against the present system.

(Reply to Bosanquet; III: 255; see also V: 519: it was then “a currency regulated by no standard”)

In other words, what happened to the value of the standard of money was then beyond the point. What had to be explained was the rise in the money price of gold bullion, which should be carefully distinguished from its value. Ricardo considered that failing to recognise this distinction was the source of much “error”, particularly by Henry Thornton:

The error of this [Thornton’s] reasoning proceeds from not distinguishing between an increase in the value of gold, and an increase in its money price.

(High Price, III: 60)

The rise in the price of gold was to be related to the excess issue of inconvertible notes, and the question of the possibility of a change in the value of gold could be left aside:

In saying however that gold is at a high price, we are mistaken; it is not gold, it is paper which has changed its value.

(ibid: 80)

This is the reason why, in the Bullion Essays, there is not more than a handful of references to a change in the value of gold – the most notable being to what happens when a new productive gold mine is discovered (see below Chapter 5).

Things changed in 1815. First, with the end of the Napoleonic wars the historical perspective was now the resumption of the convertibility of the Bank of England note and the question was henceforth how to ensure a “secure currency”, even in the long run. Second, from an analytical point of view, Ricardo had since August 1813 (according to Sraffa, 1951d: 3) broadened his interest in political economy to the question of the rate of profit, which was the subject of the Essay on Profits, published in February 1815. This essay and the monetary pamphlet Proposals for an Economical and Secure Currency, published in February 1816, testify to the two lines of enquiry developed by Ricardo at the time and may be considered as blueprints of On the Principles of Political Economy, and Taxation, published in April 1817. It is not surprising that these two lines merged in Ricardo’s mind, as shown in the following letter of 30 December 1815, sent to James Mill who had invited him to put his thoughts on paper on what would later become Principles:

I know I shall be soon stopped by the word price, and then I must apply to you for advice and assistance. Before my readers can understand the proof I mean to offer, they must understand the theory of currency and of price. They must know that the prices of commodities are affected two ways one by the alteration in the relative value of money, which affects all commodities nearly at the same time, – the other by an alteration in the value of the particular commodity, and which affects the value of no other thing, excepting it enter into its composition. – This invariability of the value of the precious metals, but from particular causes relating to themselves only, such as supply and demand, is the sheet anchor on which all my propositions are built; for those who maintain that an alteration in the value of corn will alter the value of all other things, independently of its effects on the value of the raw material of which they are made, do in fact deny this doctrine of the cause of the variation in the value of gold and silver.

(VI: 348‒9)14

One should note that Ricardo evoked the difficulty raised by the word “price”, not the word “value”. The price of a commodity being measured in money – in contrast with its exchangeable value that was measured in any other commodity – a change in this price could as well reflect a change on the side of money – “the alteration of the relative value of money” – and on the side of the commodity – “an alteration in the value of the particular commodity”. The difficulty mentioned here was thus not that considered above of a circular determination of exchangeable values and the rate of profit, a difficulty that occurred on the side of commodities. It concerned the possibility of disentangling these “two ways” through which “the prices of commodities may be affected”. In order to isolate what was to be studied by the theory of value and distribution, Ricardo neutralised the operation of the monetary way by assuming the absence of any “alteration of the relative value of money”. This method, which was “the sheet anchor on which all my propositions are built”, would be subject to several emphatic warnings in all three successive editions of Principles, such as those quoted above (on pp. 108–9 and 86 respectively) from I: 46 and 48 and the following:

I have already in a former part of this work considered gold as endowed with this uniformity [of value], and in the following chapter I shall continue the supposition. In speaking therefore of varying price, the variation will be always considered as being in the commodity, and never in the medium in which it is estimated.

(Principles; I: 87)

The reader is desired to bear in mind, that for the purpose of making the subject more clear, I consider money to be invariable in value, and therefore every variation of price to be referable to an alteration in the value of the commodity.

(ibid: 110)

In contrast with what in modern theory is called the neutrality of money in respect to relative prices – namely that a change in the value of money in terms of commodities does not alter their relative prices – Ricardo discarded this question by making “the supposition” that there was no change in the value of money. And this he did (as quoted above from the letter to Mill of 30 December 1815) by assuming “this invariability of the value of the precious metals, but from particular causes relating to themselves only”.15 The invariability of the standard was consequently not only required to study the distribution of aggregate income or variations in the exchangeable values of commodities relatively to each other (as acknowledged by the modern literature), but also to allow interpreting a change in the money price of a commodity as reflecting the same change in the real value of that commodity – what Ricardo would call in his last manuscript its absolute value.