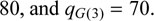

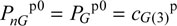

Natural price of one ounce of gold bullion, in pesos;

Natural price of one ounce of gold bullion, in pesos;5 The adjustment to a change in the value of the standard

No country that used the precious metals as a standard, were exempted from variations in the prices of commodities, occasioned by a variation in the value of their standard.

(Speech in the House of Commons, 12 June 1822; V: 204)

In Chapter 4 above I already discussed the “analogy” made by Ricardo in the Bullion Essays between an increase in the quantity of money caused by the discovery of a new gold mine and one caused by an additional discretionary issue of inconvertible notes. I contended that the adoption in Principles of a theory of the value of commodities based on their cost of production with the portion of capital that pays no rent allowed Ricardo to understand that, in a monetary system regulated by a standard, it is not by its quantity that the standard affected permanently the value of money (as he believed in the Bullion Essays) but by its cost of production. However, Ricardo maintained that, as in the case of an excess issue of bank notes, the discovery of a new mine caused a fall in the value of money through an increased quantity of money:

If by the discovery of a new mine, by the abuses of banking, or by any other cause, the quantity of money be greatly increased, its ultimate effect is to raise the prices of commodities in proportion to the increased quantity of money.

(Principles; I: 298)

In the case of notes, an excess issue of them (consequent upon “abuses of banking”) caused a general rise in money prices because it induced a depreciation of money, that is, a market price of gold bullion paid for in notes above the legal price of gold in coin. The question should thus be raised: Did the discovery of a new gold mine also cause an excess quantity of money and thereby its depreciation? I will contend that while in 1810 Ricardo remained rather ambiguous about an interpretation of the effect of a newly discovered gold mine in terms of depreciation of money, his later insistence on the distinction between a depreciation of money caused by its excess quantity and a fall in the value of money caused by a fall in the value of gold bullion implied that the effect of the discovery of a new gold mine belonged to the latter case, not to the former. Paradoxically, this became clear when, during the debates in 1819‒1823 around the resumption of convertibility, Ricardo discussed another aspect of the behaviour of the Bank of England than its note issuing: the faulty management of its gold reserve that caused an increase in the value of bullion and thereby in the value of money. This effect was symmetrical, not about the depreciation of the currency caused by an excess issue of notes, but about the fall in the value of money caused by a fall in the value of bullion after the discovery of a new gold mine.

In the Bullion Essays Ricardo contended that the discovery of a new mine more productive than at least some of those previously worked led to a permanent fall in the value of gold-money:

If a mine of gold were discovered in either of these countries, the currency of that country would be lowered in value in consequence of the increased quantity of the precious metals brought into circulation.

(High Price; III: 54)

Here, the effect of the discovery of a new gold mine on the value of money was ascribed to an increase in the quantity of gold produced, which generated an increase in the quantity of coins (“in consequence of the increased quantity of the precious metals brought into circulation”). There was one step then to consider this quantity of money as being in excess, and one step more to conclude that money was not only “lowered in value” but in fact depreciated. Did Ricardo make these steps? As shown below, there is some ambiguity in his writings of that period. However, after he adopted a few years later a theory of value based on the concept of difficulty of production, this ambiguity disappeared: the discovery of a new mine did lower the value of money and hence raised the money prices of commodities, but the channel of transmission was not an excess quantity and a depreciation of money. A reduction in the cost of production of gold – consequent upon the discovery of a new highly productive mine or the introduction of a new cost-reducing technique – was henceforth translated into a fall in the value of money through a fall in the value of bullion in terms of all other commodities, and not through a depreciation of money caused by an excess quantity (Section 5.1). This explanation of the effect of a newly discovered gold mine on the value of money was permitted by the extension of Ricardo’s theory of rent from land to mines (Section 5.2). There was, however, a specificity of gold bullion in respect to corn, which affected the adjustment process of the natural price to the discovery of a new gold mine (Section 5.3). This adjustment may be analysed in two steps: in the gold-producing country (Section 5.4) and in the gold-importing country where bullion was coined (Section 5.5). A symmetrical case was the adjustment to an increased demand for gold bullion, as that implemented by the Bank of England in the perspective of the resumption of the convertibility of its note into coin (Section 5.6). Both cases illustrate the relevance of the Money–Standard Equation (Section 5.7).

5.1 From an ambiguity in the Bullion Essays to a clarification in Principles

Criticising Bentham on the cause of the general rise in prices

At the time of the Bullion Essays, Ricardo sometimes interpreted the discovery of a new gold mine as causing a depreciation of money. This was implied in Reply to Bosanquet by the “analogy” between the discovery of a new gold mine and the additional discretionary issuing of inconvertible notes, and illustrated by his manuscript comments on the minutes of evidence before the Bullion Committee in 1810. On someone being asked about “an excessive currency, though not forced”, and answering “I do not conceive the thing possible”, Ricardo commented:

This seems to be the source of all the errors of these practical men. A paper currency cannot be excessive, according to them, if no one is obliged to take it against his will. They must be of opinion that a given quantity of currency can be employed by a given quantity of commerce and payments, and no more, – not reflecting that by depreciating its value the same commerce will employ an additional quantity. Did not the discovery of the American mines depreciate the value of money, and has not the consequences been an increased use of it. By constantly depreciating its value there is no quantity of money which the same state of commerce may not absorb.

(III: 362)

And contradicting a Director of the Bank of England:

The bank during the suspension of Cash payments, with its present excessive issues produces the same effect as the discovery of a new mine of gold which should materially depreciate the value of money.

(ibid: 376‒7)

Speaking of the relative redundancy of money in two countries, Ricardo wrote in a letter to Malthus of 18 June 1811:

This relative redundancy may be produced as well by a diminution of goods as by an actual increase of money, (or which is the same thing by an increased economy in the use of it) in one country; or by an increased quantity of goods, or by a diminished amount of money in another. In either of these cases a redundancy of money is produced as effectually as if the mines had become more productive.

(VI: 26)

Elsewhere at the same time, however, Ricardo seemed to discard such interpretation in terms of depreciation, as in his manuscript “Notes on Bentham’s ‘Sur les prix’”, written at the very end of 1810 (for the history of these notes on Bentham’s manuscript “Sur les prix” and a comparison between the two writings see Deleplace and Sigot 2012). Although Ricardo acknowledged that an increase in the quantity of coins and an increase in the quantity of notes would both cause a general rise in prices, he noticed a difference between the two cases:

The argument in this chapter [by Bentham] is that an increase of paper money has the same effects in increasing prices as an increase in metallic money. This is no doubt true, but we should recollect that paper money cannot be increased without causing a depreciation of such money as compared with the precious metals.

(III: 269)

The depreciation of the notes being “as compared with the precious metals”, it was reflected in a rise of the market price of bullion paid for in notes. An increase in the quantity of notes thus caused a rise in all prices of commodities paid for in notes, including that of gold bullion. In contrast, an increase in the quantity of coins, although it also raised the prices of all other commodities paid for in coins, did not raise the price of gold bullion (provided the coins were full-bodied) since an ounce of gold bullion always exchanged for an ounce of gold in coin (see Chapter 6 below). This excerpt shows that, at the time of the Bullion Essays, Ricardo already made a distinction between a general rise in prices (including that of bullion), caused by a depreciation of money, and a general rise in prices (excluding that of bullion), caused by a fall in the value of gold. This distinction was, however, obscured by the fact that, at that time, Ricardo understood this fall in the value of gold as being caused by an increase in its quantity produced, so that, as in the case of notes, the rise in price of all other commodities was explained by an increase in quantity – of gold as of notes. This explanation allowed Ricardo to express his agreement with Bentham on the general rise in price of commodities having been caused by an increase in the quantity of money, and his disagreement with him on the kind of money that was responsible for that rise. On Bentham saying: “The value of money is at present [in 1801] only half of what it was forty years ago: in forty years it will only be half of what it is at present”1 Ricardo commented with a phrase preceding the previous excerpt:

As I attribute the fall in the value of money during the last 40 years to the increase of the metals from which money is made, I cannot anticipate a similar fall in the next 40 years unless we should discover new and abundant mines of the precious metals.

(ibid)

By “increase of the metals” Ricardo meant an increase in the quantity produced of them. He had in view the long-term phenomenon (“40 years”) of “the fall in the value of money”, which he explained by the discovery of “new and abundant mines” that had increased the quantity produced of precious metals, hence reduced their value in terms of all other commodities. It was this fall in the value of gold which had provoked a fall in the value of money made of gold, and consequently a general rise in prices. On the contrary, Bentham attributed this rise to an overissue of notes. For Ricardo, such overissue did explain the depreciation of money – also responsible for a general rise in prices – although not at the period considered by Bentham (the 40 years before 1801) but more recently, after the suspension of convertibility in 1797 had produced its effects.

This critique addressed by Ricardo to Bentham anticipated the distinction made by him later (see Chapter 4 above) between a general increase in prices due to a fall in the value of gold in terms of all other commodities, and one due to a depreciation of money, measured by a rise in the price of gold in terms of money (that is, a fall in the value of money in terms of gold). The discovery of gold mines provoked a general rise in prices through the first channel and exclusively through it. The overissue of paper provoked a general rise in prices through the second channel and exclusively through it. However, when, in the above quotation from Principles, Ricardo mentioned “the discovery of a new mine” and “the abuses of banking”, he stressed that in both cases the prices of commodities were raised while the quantity of money increased, but he abstracted from the difference between coins and notes as to the transmission channel associated with an increase in the quantity of money. This point should, however, be clarified.

When in Reply to Bosanquet Ricardo made his “analogy” between an increased quantity of money caused by the discovery of a new gold mine “on the own premises” of the Bank of England and one caused by an additional discretionary issue of inconvertible notes, he supposed that gold was immediately coined by the Bank of England itself:

Now supposing the gold mine to be actually the property of the Bank, even to be situated on their own premises, and that they procured the gold which it produced to be coined into guineas, and in lieu of issuing their notes when they discounted bills or lent money to Government that they issued nothing but guineas; could there be any other limit to their issues but the want of the further productiveness in their mine? In what would the circumstances differ if the mine were the property of the king, of a company of merchants, or of a single individual? In that case Mr. Bosanquet admits that the value of money would fall, and I suppose he would also admit that it would fall in exact proportion to its increase.

(Reply to Bosanquet; III: 216‒17)

If the Bank of England itself issued coins, there would indeed be no difference with its issuing of notes: the exogenous increase in the quantity of gold bullion would immediately mean an increase in the quantity of money, as when the Bank of England discretionarily issued an additional quantity of notes. But would it be so “if the mine were the property of the king, of a company of merchants, or of a single individual”? It would for the king, who enjoyed the privilege of issuing coins. But it would not in the case “of a company of merchants, or of a single individual”, who needed to carry the gold bullion to the mint to have it coined. And so was it actually for that particular “company of merchants” called the Bank of England. However, all these private owners of the gold bullion produced by a new mine had also the possibility of selling it in the market against existing coins or notes, rather than carry it to the mint to get new coins. As already noted in Chapter 3 above, Ricardo was well aware that gold bullion could only be converted into money if its market price was below the legal price of gold in coin, which was the same as saying that the value of money was above the value of bullion. As he would write five years later in Proposals:

It is the rise in the value of money above the value of bullion which is always, in a sound state of the currency, the cause of its increase in quantity; for it is at these times that either an opening is made for the issue of more paper money, which is always attended with profit to the issuers; or that a profit is made by carrying bullion to the mint to be coined. To say that money is more valuable than bullion or the standard, is to say that bullion is selling in the market under the mint price.

(Proposals; IV: 56‒7)

Two inferences might be drawn from this necessary condition for an increased quantity of money to follow on an increased quantity of bullion. First, any interpretation of such situation in terms of depreciation caused by money being in excess should be discarded, in contrast with what happened in the case of an additional discretionary issuing of notes. The increase in the quantity of money after the discovery of a new gold mine was the consequence of a fall in the market price of bullion below the legal price of gold in coin; the increase in the quantity of money discretionarily decided by an issuing bank was the cause of a rise in the market price of bullion above the legal price of gold in coin. We will see that, “in a sound state of the currency”, the final outcome of the adjustment was in both cases the return of the market price of gold bullion to the level of the legal price of gold in coin, but in the case of the mine it was from below (through coining) while in the case of the bank it was from above (through melting).

The second inference is that, to explain how the quantity of money increased after the discovery of a new gold mine, one should understand what happened to the market price of gold bullion. Why did Ricardo in his “analogy” make the simplifying assumption that the Bank of England itself issued coins, thus bypassing the adjustment in the bullion market? One may suggest two reasons, one on the side of money the other on the side of gold bullion as commodity.

On the side of money, the “analogy” was at the time of the Bullion Essays explicitly made by Ricardo with the discretionary issuing of inconvertible bank notes. Ricardo considered that, in a situation where Bank of England notes had been made inconvertible and gold and silver coins had disappeared from circulation, money was no longer regulated by the standard:

That gold is no longer in practice the standard by which our currency is regulated is a truth. It is the ground of the complaint of the [Bullion] Committee (and of all who have written on the same side) against the present system.

(Reply to Bosanquet; III: 255)

In his writings of 1819‒1823 Ricardo would again emphasise this absence of regulation of the note issue by the standard during the period of inconvertibility:

It is also forgotten, that from 1797 to 1819 we had no standard whatever, by which to regulate the quantity or value of our money. Its quantity and its value depended entirely on the Bank of England, the directors of which establishment, however desirous they might have been to act with fairness and justice to the public, avowed that they were guided in their issues by principles which, it is no longer disputed, exposed the country to the greatest embarrassment. Accordingly, we find that the currency varied in value considerably during the period of 22 years, when there was no other rule for regulating its quantity and value but the will of the Bank.

(Protection to Agriculture; IV: 222‒3)

The value of money not being regulated by the standard meant that it was detached from the value of the latter. What happened to the market price of bullion only indicated by how much money departed from a situation in which it would be so regulated: this price was only “a proof of the depreciation of bank notes”. When in 1816 Ricardo developed in Proposals the plan of note convertibility into bullion outlined in 1811 in the Appendix to the fourth edition of High Price, he explicitly considered “a sound state of the currency”, that is, “the reverting from a currency regulated by no standard, to one regulated by a fixed one” as he would say in the “Draft on Peel” of 1821 (V: 519). Abstracting from the bullion market was thus no longer possible since its working was at the heart of this regulation, hence a central piece of the theory of money.

On the side of gold bullion as commodity, in the Bullion Essays its market price reflected its scarcity, like that of any commodity (see Chapter 4 above). The increased quantity of bullion produced after the discovery of a new mine was the only element to be taken into account in the adjustment of the quantity and the value of money, whether the owner of the new mine carried himself its production to the mint or sold it in the market, thus depressing the price of bullion so that its buyers carried it to the mint. Things changed when in Principles Ricardo adopted the view according to which “it is not quantity that regulates price, but facility or difficulty of production” (Letter to Maria Edgeworth of 13 December 1822; IX: 239). A corollary was that the market price of any competitively produced commodity varied temporarily with the quantity supplied but was ultimately regulated by the natural price, determined by the cost of production. Of course the increased quantity of bullion consequent upon the discovery of a new mine immediately depressed its market price, but since it was produced in competitive conditions one should inquire about what happened to its natural price before drawing a conclusion on the permanent change in the value of money. The adjustment in the market for gold bullion had henceforth to be made explicit: the simplifying assumption that the owner of the new mine bypassed the market was no longer acceptable – and neither was the “analogy”. The production of gold bullion was now to be compared with the production of corn, not with the issuing of inconvertible bank notes. A preliminary step was to extend the theory of rent from land to mines.

5.2 The extension of the theory of rent from land to mines

As with every commodity produced with capital in competitive conditions, gold had a natural price allowing any portion of capital advanced in its production to earn the same general rate of profit as in any other employment. Being produced in mines of different qualities, its natural price was determined by the cost of production with that portion of capital which was the least productive and paid no rent. According to Ricardo, the theory of differential rent applied to mines: after having exposed it for land in Chapter II of Principles “On rent”, Ricardo extended it in Chapter III “On the rent of mines”:

Mines, as well as land, generally pay a rent to their owner; and this rent, as well as the rent of land, is the effect, and never the cause of the high value of their produce.

If there were abundance of equally fertile mines, which any one might appropriate, they could yield no rent; the value of their produce would depend on the quantity of labour necessary to extract the metal from the mine and bring it to market.

But there are mines of various qualities, affording very different results, with equal quantities of labour. The metal produced from the poorest mine that is worked, must at least have an exchangeable value, not only sufficient to procure all the clothes, food, and other necessaries consumed by those employed in working it, and bringing the produce to market, but also to afford the common and ordinary profits to him who advances the stock necessary to carry on the undertaking. The return for capital from the poorest mine paying no rent, would regulate the rent of all the other more productive mines. This mine is supposed to yield the usual profits of stock. All that the other mines produce more than this, will necessarily be paid to the owners for rent. Since this principle is precisely the same as that which we have already laid down respecting land, it will not be necessary further to enlarge on it.

(Principles; I: 85)

As for land, the theory of rent applied to mines raises two distinct questions: first the effects of a change in the demand for the commodity produced in the mines; second, the effects of a change in the supply of that commodity, whether it be a consequence of the discovery of new mines or of the introduction of new production techniques. It seems that Ricardo himself and the subsequent Ricardian theory of the rent of land have mostly concentrated on the effect of changes on the side of demand, as part of a dynamic analysis of the interrelations between the determination of prices, the distribution of income, and the accumulation of capital. The cultivation of new lands and the introduction of new techniques are indeed considered, but as a response to a change in demand, not as an independent change on the supply side.2 In contrast, since the analysis of the relation between the quantity and the value of money was approached by Ricardo from the point of view of an exogenous change in the quantity of money issued, he concentrated his attention on changes occurring on the supply side. Typically, Ricardo considered the effects of the discovery of a new mine, which illustrated the analytical case of an exogenous increase in the quantity of gold-money issued and the historical fact of the large inflow of precious metals in Europe having followed the conquest of America.

It should be emphasised that, as for the analysis of the rent on land, Ricardo’s reasoning was in terms of portions of capital rather than in terms of mines or pieces of land. Capital is what should earn the general rate of profit in the natural state, and portions of capital are added or withdrawn according to whether more or less than the general rate of profit may be earned, no matter a new mine (piece of land) be opened (cultivated) or an old one be closed down (left fallow).3 This point was stressed by Ricardo in Principles as an answer to Say and Malthus who contended, as a matter of fact, that every land paid a rent. In Chapter XXXII “Mr. Malthus’s opinions on rent”, Ricardo wrote:

It is not necessary to state, on every occasion, but it must be always understood, that the same results will follow, as far as regards the price of raw produce and the rise of rents, whether an additional capital of a given amount, be employed on new land, for which no rent is paid, or on land already in cultivation, if the produce obtained from both be precisely the same in quantity. See p. 72. M. Say, in his notes to the French translation of this work, had endeavoured to shew that there is not at any time land in cultivation which does not pay a rent, and having satisfied himself on this point, he concludes that he has overturned all the conclusions which result from that doctrine. […] But before M. Say can establish the correctness of this inference [on the effect of taxes on corn] he must also shew that there is not any capital employed on the land for which no rent is paid (see the beginning of this note, and pages 67 and 74 of the present work); now this he has not attempted to do. In no part of his notes has he refuted, or even noticed that important doctrine.

(ibid: 412‒13)4

On p. 72 of Principles to which Ricardo referred, a numerical example ends with: “In this case, as well as in the other, the capital last employed pays no rent.” Leaving aside questions of facts, it might seem that Ricardo’s assumption according to which the least productive land or mine pays no rent contradicts his repeated insistence that individuals are driven by interest alone: why would the owner of a land or a mine agree to lease it if it does not afford any rent? The other references made by Ricardo to pages of his Chapter II “On rent” suggest that reasoning in terms of portions of capital allowed answering this logical objection, as it did to Malthus’s and Say’s factual objection. The reference to p. 67 in the above quotation is to the definition of rent, based on the distinction between “that portion of the produce of the earth, which is paid to the landlord for the use of the original and indestructible powers of the soil”, and what is paid “for the improved farm”. Only the former is properly rent, “in the strict sense to which I am desirous of confining it”, while the latter is in the nature of profit, even if it is like rent paid to the landlord (since it is not the farmer but the landlord who in the past advanced the capital responsible for the improvement of the land for which the lease is contracted). When a portion of capital is added to an existing land, it yields an additional profit – as every previous portion of capital that improved the land in the past – but no rent is paid since there is no change in “the original and indestructible powers of the soil”. Rent consequently did not enter the determination of the cost of production with the last portion of capital, and this was of the utmost importance for Ricardo’s theory of distribution:

By getting rid of rent, which we may do on the corn produced with the capital last employed, and on all commodities produced by labour in manufactures, the distribution between capitalist and labourer becomes a much more simple consideration.

(Letter to McCulloch, 13 June 1820; VIII: 194)

Reasoning in terms of last portion of capital invested and not in terms of last land cultivated was justified by Ricardo as follows, in a speech on Agricultural Distress Report in the House of Commons on 7 May 1822:

It was not that cultivators were always driven by the increase of population to lands of inferior quality, but that from the additional demand for grain, they might be driven to employ on land previously cultivated a second portion of capital, which did not produce as much as the first. On a still farther demand a third portion might be employed, which did not produce so much as the second: it was manifestly by the return on the last portion of capital applied, that the cost of production was determined.

(V: 167)

Keeping then in mind that Ricardo’s proper reasoning was in terms of portion of capital and not in terms of land or of mine, I will nevertheless use these expressions indifferently as Ricardo often did himself:

My argument respecting rent, profit and taxes, is founded on a supposition that there is land in every country which pays no rent, or that there is capital employed on land before in cultivation for which no rent is paid. You answer the first position, but you take no notice of the second. The admission of either will answer my purpose.

(Letter to Say, 11 January 1820; VIII: 149‒50)

The extension of the theory of rent from land to mines now raises the question of the comparison between Ricardo’s treatment of corn and that of gold bullion.

5.3 The specificity of gold bullion in respect to corn

The adjustment to a new land growing corn with a higher productivity

The situation created by the discovery of a new gold mine may be compared with that of a new technique of production of corn which allows a land previously lying fallow to become cultivated with a higher productivity than at least the land of the lowest quality already cultivated (“If a large tract of rich land were added to the Island [England]”, letter to Malthus, 21 April 1815, VI: 220; one may think of a new technique of draining a marsh, making it useful for cultivation with a high yield). In such a case, the increase in the total production of corn sinks its market price below the natural price determined by the cost of production on the previously cultivated land of the lowest quality, and the capital advanced on this land is withdrawn and transferred to another employment. This has two consequences: first, the production of corn is lowered by the amount produced previously on the land abandoned; second, the natural price declines because it is now determined by the cost of production on a land more productive than before. Capital goes on being withdrawn until the market price and the natural price of corn equalise, that is, until every portion of capital advanced on the still cultivated lands (including the one where the new technique has been applied) earns the general rate of profit. On the land which is henceforth of the lowest quality, no rent is paid, and differential rents are paid to the proprietors of the lands of better qualities, according to their respective productivity. In the final situation, the total quantity of corn produced is the same as in the initial situation, the quantity produced by the newly cultivated land having substituted for that produced by the abandoned ones. The total quantity of corn in the final situation is again equal to the natural demand, and it is produced at a lower natural price than in the initial situation.

This adjustment process has an important effect, which is the reverse of the well-known increase in natural wages consequent upon the new cultivation of less productive lands. Here, since the natural price of corn declines when less productive lands are abandoned, natural wages are lowered and the natural rate of profit increases accordingly. Answering a question by Malthus on this point, Ricardo quoted literally his friend’s supposition of his view of the subject:

You have correctly anticipated my answer: ‘Capital will’ I think ‘be withdrawn from the land, till the last capital yields the profit obtained (by the fall of wages) in manufactures, on the supposition of the price of such manufactures remaining stationary’.

(Letter from Ricardo to Malthus, 9 November 1819; VIII: 130; the quotation is from a letter from Malthus to Ricardo, 14 October 1819; ibid: 108)

This “supposition” was, however, contradicted by the effect of a change in distribution on relative prices (see Chapter 3 above) and, as shown in Sraffa (1960), the ranking of the lands was also altered by this change in distribution, creating a major difficulty for the theory of rent.

In Principles, Ricardo gave two examples of such an adjustment process “in consequence of permanent abundance” of corn (Principles; I: 268). In Chapter II “On rent”, an improvement in cultivation techniques does not lead to the withdrawal of the whole capital advanced on the least productive land but only to the transfer of the least productive portion of capital advanced on that land. In the initial situation, four “successive portions of capital” (ibid: 81) yield respectively 100, 90, 80, and 70 quarters of corn, so that the whole rent is equal to 60 quarters out of a total production of 340. After an improvement in cultivation applied equally to each portion of capital, these respective yields become 125, 115, 105, and 95, so that total production on the land mounts to 440 quarters:

But with such an increase of produce, without an increase in demand, there could be no motive for employing so much capital on the land; one portion would be withdrawn, and consequently the last portion of capital would yield 105 instead of 95, and rent would fall to 30, […] the demand being only for 340 quarters.

(ibid: 81‒2)

The increased production of corn consequent upon the improvement in cultivation faces an unchanged demand for the reproduction of the population,5 so that the market price falls below the natural price determined by the least productive portion of capital which becomes unprofitable (at the general rate of profit) and is withdrawn from the production of corn. The total production on the land is brought back approximately to its initial level (345 quarters instead of 340), in line with the unchanged natural demand for corn.

In Chapter XIX “On sudden changes in the channels of trade”, Ricardo considered “a revulsion of trade” (ibid: 265) such as a war which interrupts the importation of corn. The diminution of the quantity supplied, while the demand remains unaltered, pushes the market price of corn upwards, so that the cultivation of less fertile lands becomes profitable. The balance between the supply and the demand is then re-established, although at a higher natural price than before the war. When the war terminates and importation of corn resumes, the opposite movement occurs: the excess quantity of corn available sinks its market price, and the less fertile lands cannot be profitably cultivated any longer:

In examining the question of rent, we found, that with every increase in the supply of corn, capital would be withdrawn from the poorer land; and land of a better description, which would then pay no rent, would become the standard by which the natural price of corn would be regulated. At 4l. per quarter, land of inferior quality, which may be designated by No. 6, might be cultivated; at 3l. 10s. No. 5; at 3l. No. 4, and so on. If corn, in consequence of permanent abundance, fell to 3l. 10s., the capital employed in No. 6 would cease to be employed; for it was only when corn was at 4l. that it could obtain the general profits, even without paying rent: it would, therefore, be withdrawn to manufacture those commodities with which all the corn grown on No. 6 would be purchased and imported.

(ibid: 268)

In this example, the fall in the market price of corn, due to its “permanent abundance”, makes capital advanced on land No. 6 unprofitable (at the general rate of profit) so that it is withdrawn from the production of corn and transferred to an employment in manufactures. The total quantity of corn supplied is again equal to the unchanged natural demand, since the production of the land abandoned is replaced by imported corn produced at a cost consistent with the diminished market price. This foreign corn is itself purchased by the export of the commodities now produced by the capital transferred from the abandoned land.

In both examples, when corn becomes permanently abundant for an exogenous reason (an improvement in cultivation, the resumption of importation at the end of a war), the adjustment process occurs solely on the side of the quantity supplied, not on the side of demand, because there is a natural demand which must be satisfied, neither less nor more:

If the natural price of bread should fall 50 per cent. from some great discovery in the science of agriculture, the demand would not greatly increase, for no man would desire more than would satisfy his wants, and as the demand would not increase, neither would the supply; for a commodity is not supplied merely because it can be produced, but because there is a demand for it. Here, then, we have a case where the supply and demand have scarcely varied, or if they have increased, they have increased in the same proportion; and yet the price of bread will have fallen 50 per cent. at a time, too, when the value of money had continued invariable.

(ibid: 385)6

When it is in excess, the quantity of corn produced is adjusted to the natural demand through the successive withdrawal of the less productive portions of capital (on the same land or on different lands), until the balance between supply and demand is re-established through the equalisation of the market price with the natural price. It should be observed that in both examples, the withdrawal of capital is just enough to ensure this equalisation and thus to bring the supply of corn in line with the natural demand. Although there are discontinuities in production – “successive portions of capital” provide successive yields – its reduction through the withdrawal of one or more of these portions does not overshoot the excess, so that the market price never becomes higher than the natural price. Two reasons may explain this assumption. First, the successive withdrawal of portions of capital is nothing else as the reverse of their previous successive application to the production of corn when it was in short supply; if this process had been implemented smoothly7 – as Ricardo himself assumes by stating that the increase in production may not necessarily require the cultivation of new lands but only the inflow of new portions of capital applied to the same lands – its reverse may follow the same route. Second, corn is produced in competitive conditions, and if for any reason the production of corn were cut by more than what is required to match the natural demand, the market price would rise above the natural price, and abnormal profits would induce an inflow of capital into the production of corn until they disappear. This adjustment is the one which occurs when, because of a domestic increase in population or a higher foreign demand, an increase in the demand for corn raises its market price above its natural price.8

Two differences between gold bullion and corn

In Chapter XIII of Principles “Taxes on gold”, Ricardo emphasises two differences between corn and gold bullion, one on the supply side the other on the demand side. They both affect the adjustment process triggered by an increase in the quantity of the commodity produced.

On the supply side, the speed at which the market price adjusts is greater for corn than for gold, due to a difference in durability:

The agreement of the market and natural prices of all commodities depends at all times on the facility with which the supply can be increased or diminished. In the case of gold, houses, and labour, as well as many other things, this effect cannot, under some circumstances, be speedily produced. But it is different with those commodities which are consumed and reproduced from year to year, such as hats, shoes, corn, and cloth; they may be reduced, if necessary, and the interval cannot be long before the supply is contracted in proportion to the increased charge of producing them.

(ibid: 196)

The difference in durability manifests itself in a high or low ratio of the flow of new production to the existing stock. In the case of corn, the annual production is totally consumed in the period as wage-good or seeds, and no stock is carried from one period to the other. In the case of “gold, houses, and labour”, the stock is large in comparison with annual production, so that a change in the latter affects only slowly the market price (on the importance of the durability of gold in Ricardo’s theory of the value of money, see Takenaga 2013). This is particularly the case with gold used as money:

The metal gold, like all other commodities, has its value in the market ultimately regulated by the comparative facility or difficulty of producing it; and although from its durable nature, and from the difficulty of reducing its quantity, it does not readily bend to variations in its market value, yet that difficulty is much increased from the circumstance of its being used as money. If the quantity of gold in the market for the purpose of commerce only, were 10,000 ounces, and the consumption in our manufactures were 2000 ounces annually, it might be raised one fourth, or 25 per cent. in its value, in one year, by withholding the annual supply; but if in consequence of its being used as money, the quantity employed were 100,000 ounces, it would not be raised one fourth in value in less than ten years.

(Principles; I: 193‒4)9

Nevertheless, in the numerical example which illustrates the effects of taxes on gold, Ricardo supposes that the market price of gold-money increases in the same proportion as its quantity produced decreases (see Appendix 5 below); this amounts to neglecting the difference in durability between corn and gold bullion and considering only the initial and the final situations. As will be seen below, this does not mean, as Ricardo is often blamed for in the literature, that he gives no indication about the forces at work during the adjustment process. This simply means that this difference in durability, while affecting the speed of adjustment, does not affect its modus operandi.

On the demand side, the difference between gold and corn is that, in contrast with necessaries which must be consumed if the population is to be reproduced, there is no natural quantity of money made of gold:

The demand for money is not for a definite quantity, as is the demand for clothes, or for food. The demand for money is regulated entirely by its value and its value by its quantity. If gold were of double the value, half the quantity would perform the same functions in circulation, and if it were of half the value, double the quantity would be required. If the market value of corn be increased one tenth by taxation, or by difficulty of production, it is doubtful whether any effect whatever would be produced on the quantity consumed, because every man’s want is for a definite quantity, and, therefore, if he has the means of purchasing, he will continue to consume as before: but for money, the demand is exactly proportioned to its value. No man could consume twice the quantity of corn, which is usually necessary for his support, but every man purchasing and selling only the same quantity of goods, may be obliged to employ twice, thrice, or any number of times the same quantity of money.

(ibid: 193)

The aggregate value of the commodities to be circulated being given, any quantity of money will do.10 A small quantity of money performs the same circulating office as a large one: the commodities “would be circulated with a less quantity, because a more valuable money” (ibid: 196). Already in his “Notes on Bentham’s ‘Sur les prix’” in 1810, Ricardo had observed that the specificity of the demand for gold used as money prevented a gold-importing country from being benefited by an improvement in its production abroad, in contrast with any other commodity:

If in a foreign country new means of improving the production of commodities be discovered it will be attended with real advantage to all countries which consume that commodity. – If the article were french cambrics for example England would import the quantity of cambrics she required at a less sacrifice of the produce of her own industry: – but when gold and silver are the commodities that become cheap in consequence of improved means of working the mine or the discovery of new mines no such advantage will accrue to England because the quantity of money she requires is not a fixed quantity but depends altogether on its value.

(III: 305‒6)

One may now examine the consequences of the specificity of gold bullion for the adjustment process triggered by the discovery of a new mine. For the time being I will leave aside the question of whether gold bullion is produced in the country that transforms it into money or in a foreign country before it is imported and coined. This amounts to considering that the adjustment is triggered by an increase in the supply of gold bullion that lowers its market price, whether this increased supply is consequent upon the discovery of a new mine or upon importation. The justification for this assumption is that, contrary to what is usually said of the price of internationally traded commodities being determined in Ricardo by supply and demand, the price of imported goods is regulated by their cost of production in the exporting country. This was repeated by Ricardo in Principles and elsewhere:11

All that I contend for is, that it is the natural price of commodities in the exporting country, which ultimately regulates the prices at which they shall be sold, if they are not the objects of monopoly in the importing country.

(Principles; I: 375)

The difference between domestically produced and imported bullion is thus here only in the intervention of the exchange rate (see below Section 5.5). However, we will see in the conclusive section of Chapter 7 that the specificity of the market for bullion in the country where it is the standard of money logically implies that it should be produced abroad. This is what happened in the circumstances of the time: gold was produced outside England in competitive conditions. It was then exported as bullion (no matter whether in the form of merchandise or of coins taken by weight) to England, where it was coined at the mint, with the monopoly power of issuing coins belonging to the State. When a new mine was discovered, more productive than some or all previous ones, the adjustment process thus operated successively in the gold-producing country and in the gold-importing one.

5.4 The adjustment in the gold-producing country: a new “distribution of capital”

A fall in the value of gold bullion

As mentioned above, in the case of the discovery of a new mine, a fall in the value of money occurred because of a fall in the value of gold bullion in terms of all other commodities, not of a depreciation of money in terms of gold bullion. The question is now: how did this transmission channel work? The answer required a condition that Ricardo had not yet mastered at the time of the Bullion Essays: the appropriate link between the discovery of a new mine and the fall in the value of gold bullion in terms of all other commodities. In 1810, Ricardo understood this link through the scarcity principle: the discovery of a new mine increased the total quantity of gold bullion produced and an increased supply lowered its value. This led to an adjustment described in the sequel of the quotation from High Price given above:

If a mine of gold were discovered in either of these countries, the currency of that country would be lowered in value in consequence of the increased quantity of the precious metals brought into circulation, and would therefore no longer be of the same value as that of other countries. Gold and silver, whether in coin or in bullion, obeying the law which regulates all other commodities, would immediately become articles of exportation; they would leave the country where they were cheap, for those countries where they were dear, and would continue to do so, as long as the mine should prove productive, and till the proportion existing between capital and money in each country before the discovery of the mine, were again established, and gold and silver restored every where to one value.

(High Price; III: 54)

Here Ricardo explained that the immediate consequence of the discovery of a new mine would be a fall in the value of gold in the producing country, lowering it below its value in the other countries and leading to its exportation. The final outcome was to be a new equalisation of this value across all countries, presumably at a lower level than the initial one, because of the increased quantity of bullion. But Ricardo would soon feel dissatisfied by this scarcity approach to the value of commodities. As he would write to Mill on 30 December 1815: “I know I shall be soon stopped by the word price” (VI: 348). On 5 October 1816 he would confess to Malthus: “I have been very much impeded by the question of price and value, my former ideas on those points not being correct” (VII: 71).12 This difficulty was to be overcome with the theory of value contained in Principles, which determined the relative value of competitively produced commodities by their cost of production with the portion of capital that pays no rent.

In contrast with corn for which, as seen above, Ricardo explained how the adjustment operated, he did not do the same for gold bullion and contented himself with observing that the discovery of a new rich mine or an improvement in the technique of production caused a fall in the value of gold bullion:

By the discovery of America and the rich mines in which it abounds, a very great effect was produced on the natural price of the precious metals. This effect is by many supposed not yet to have terminated. It is probable, however, that all the effects on the value of the metals, resulting from the discovery of America, have long ceased; and if any fall has of late years taken place in their value, it is to be attributed to improvements in the mode of working the mines.

(Principles; I: 86)

The discovery of a new mine of a better quality than all or some of the mines previously worked increased the quantity produced of bullion, so that its market price fell below its natural price. What happened to the value of gold bullion thus depended on the adjustment process triggered by this gap.

The closure of existing mines as a consequence of the discovery of a new one

To capture how Ricardo understood the adjustment to the new value of gold bullion, one may consider his treatment of another issue that raised the same question of the market price of gold being lower than its natural price because of an exogenous change on the supply side, although another kind of change: the imposition of a tax levied on the production of gold, the effects of which were analysed in Chapter XIII “Taxes on gold” of Principles. When each existing mine was taxed a uniform quantity of gold, the cost of production in each mine increased – and so did the natural price of bullion, determined in the least productive one – while the market price remained the same. The market price of bullion being below the natural price, some mines were forced to close down because the capital invested in them no longer earned the general rate of profit. The same situation occurs in the case of the discovery of a new mine, although for different reasons: the market price of gold falls below the natural price, and here also this gap forces some mines to close down. One can thus transpose Ricardo’s argument about the adjustment process triggered by such a gap from the effect of taxes on gold to the effect of the discovery of a new mine (for a detailed analysis of Ricardo’s argument on the effects of taxes on gold, see Appendix 5 below).

Such transposition leads to the following adjustment. In the initial situation, the market price of gold bullion produced in competitive conditions by mines differing in the quantity produced with the same capital is equal to the natural price, determined by the cost of production with the least productive portion of capital that pays no rent. Suppose now that a new mine is discovered, which is at least more productive than the least productive one previously worked. Since that discovery increases the total quantity of gold bullion brought to market, the new market price falls below the initial natural level. Consequently the portion of capital that initially determined this level no longer earns the general rate of profit and is withdrawn, with two consequences: the cost of production with the least productive portion of capital (the initial next-to-last one) decreases, and the quantity of gold brought to market diminishes, making its market price rise. This process goes on until the rising market price and the falling natural price of gold bullion equalise again at a level that is necessarily lower than the one before the discovery of the new mine. In other words, the value of gold bullion in terms of all other commodities falls because of this discovery.

On the supply side, this adjustment is the same as that for corn, since both commodities are produced in competitive conditions, so that the driving force in the adjustment is the equalisation of the rate of profit earned on each portion of capital invested in the production of bullion at the general rate of profit. The difference is on the demand side: while in the final position the total quantity of corn produced is the same as the initial one – equal to the natural quantity required to reproduce the population – there is no such constraint for gold. The demand for bullion to be transformed into money is not for a definite total quantity but, with a given aggregate value of the commodities to be circulated, for an aggregate value. To any fall in the value of gold bullion consequent upon the discovery of a new mine corresponds a proportionate increase in the total quantity demanded because, as quoted above, “for money, the demand is exactly proportioned to its value” (ibid: 193). When gold bullion is imported to be coined as money, the quantity demanded also adjusts to its value (see below Section 5.6):

While money is the general medium of exchange, the demand for it is never a matter of choice, but always of necessity: you must take it in exchange for your goods, and, therefore, there are no limits to the quantity which may be forced on you by foreign trade, if it fall in value; and no reduction to which you must not submit, if it rise.

(ibid: 194‒5)

The adjustment described by Ricardo after the imposition of taxes on gold is also instructive about how a new “distribution of capital” (ibid: 198) among the mines and between the production of gold and other employments of capital is implemented. Since after the discovery of a new mine the market price of gold bullion falls in the first place, it may only increase later to agree with the natural price if the total quantity of gold brought to market is reduced. Ricardo’s reasoning is that this reduction is obtained by the closure of one or more of the previously existing mines. This assumption is consistent with an analysis of production in which, when the market price of gold is equal to the natural price, portions of capital advanced in mines of different qualities earn the same general rate of profit, the one advanced in the mine of the lowest quality paying no rent. When the market price falls, this particular portion of capital ceases to be profitable (at the general rate of profit) and is withdrawn from that mine, which closes down. The only mines remaining in operation are those where the capital advanced may still earn the general rate of profit, by cutting part – or all, in the case of the mine becoming of the lowest quality in the final situation – of the rent it paid previously.

Ricardo’s description of the adjustment process is such that the reduction of the quantity of gold produced occurs successively, one mine closing down after the other in the order given by the comparative cost of production, until the portions of capital advanced in the remaining mines earn the general rate of profit. Because gold is not a wage-good, a change in its natural price does not modify the level of the general rate of profit. The ranking of the mines by their physical productivity is thus exempt from the effect of a change in the distribution of income (in contrast with corn-producing lands), and the order in which they should close down successively is hence unaffected by the adjustment consequent upon the discovery of a new mine.13

Moreover, assuming that the total quantity of gold produced is not reduced because each mine lowers its production but because some mines completely close down while others keep their initial level of production implies that no assumption about constant returns is necessary: each mine eligible to go on being worked produces the same quantity of gold with the same capital as before, hence at the same cost. As is well known, the question of whether it is necessary to assume constant returns is a sensitive one in classical economics. According to Piero Sraffa:

[T]his standpoint, which is that of the old classical economists from Adam Smith to Ricardo, [is such] that no question arises as to the variation or constancy of returns. The investigation is concerned exclusively with such properties of an economic system as do not depend on changes in the scale of production or in the proportion of ‘factors’.

(Sraffa, 1960: v)

The adjustment process thus conforms to this “classical standpoint”. It may now be formalised as follows.

A formalisation of the adjustment

Let me call:

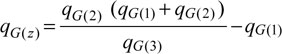

Natural price of one ounce of gold bullion, in pesos;

Natural price of one ounce of gold bullion, in pesos;

Market price of one ounce of gold bullion, in pesos;

Market price of one ounce of gold bullion, in pesos;

Cost of production (in pesos) of one ounce of gold bullion in mine h, including profit at the general rate, with

Cost of production (in pesos) of one ounce of gold bullion in mine h, including profit at the general rate, with  ranked according to their decreasing productivity;

ranked according to their decreasing productivity;

Quantity of gold bullion produced by capital advanced in mine h, in ounces.

Quantity of gold bullion produced by capital advanced in mine h, in ounces.

Supposing that the same amount of capital is advanced in each mine where it produces a different quantity of gold bullion, the cost of production of one ounce of gold in mine h is given by:

(5.1) |

The initial natural situation 0 is such that, with all k mines being worked, the market price of gold bullion is equal to its natural price, determined by the cost of production in mine k:

(5.2) |

Since the totality of gold produced is sold at its natural price, the demand  expressed in money price, is given by:

expressed in money price, is given by:

(5.3) |

Let me now suppose that a new mine z is discovered, the productivity of which is higher than that of at least mine k: with a capital equal to the one advanced in each of the previous mines, it produces  To simplify, I will also assume that the productivity of mine z is higher than that of any mine previously worked, so that

To simplify, I will also assume that the productivity of mine z is higher than that of any mine previously worked, so that  14 Equations (5.2) and (5.3) state that, in the initial natural situation, the total quantity of gold produced by the existing mines allowed its market price being just equal to the cost of production in mine k, and that made this mine profitable (at the general rate of profit). Now, with an unchanged effective demand for gold bullion, expressed in money – as implied by the specificity of gold bullion noted above – the addition of

14 Equations (5.2) and (5.3) state that, in the initial natural situation, the total quantity of gold produced by the existing mines allowed its market price being just equal to the cost of production in mine k, and that made this mine profitable (at the general rate of profit). Now, with an unchanged effective demand for gold bullion, expressed in money – as implied by the specificity of gold bullion noted above – the addition of  sinks the market price below its initial level. Calling

sinks the market price below its initial level. Calling  this new market price, equal to the ratio of

this new market price, equal to the ratio of  to the new quantity of bullion, one gets:

to the new quantity of bullion, one gets:

(5.4) |

The capital invested in mine k having ceased to be profitable (at the general rate of profit), it is withdrawn. Depending on the level of  and so on, other portions of capital may also become unprofitable at this market price

and so on, other portions of capital may also become unprofitable at this market price  and become eligible to be withdrawn. However, the closure of mine k makes the total production of gold decrease, and its market price consequently rise, so that a given portion of capital may be unprofitable before mine k closes down and become again profitable after its closure. The actual path of adjustment thus depends on the assumption made on the conditions under which the portions of capital are withdrawn. Ricardo’s assumption is that the withdrawal occurs successively, one portion after the other, that is, after the total production of gold has adjusted to the withdrawal of the last portion.15

and become eligible to be withdrawn. However, the closure of mine k makes the total production of gold decrease, and its market price consequently rise, so that a given portion of capital may be unprofitable before mine k closes down and become again profitable after its closure. The actual path of adjustment thus depends on the assumption made on the conditions under which the portions of capital are withdrawn. Ricardo’s assumption is that the withdrawal occurs successively, one portion after the other, that is, after the total production of gold has adjusted to the withdrawal of the last portion.15

The final new natural position is such that, with b of the previous mines closing down  the new final market price

the new final market price  is equal to the new natural price

is equal to the new natural price  equal to the cost of production in mine

equal to the cost of production in mine  It is thus given by:

It is thus given by:

(5.5) |

As in the initial situation (equation (5.2)), the condition of the existence of a new permanent natural position is the equality of the market price and the natural price of gold bullion, the latter being determined by the least productive portion of capital that pays no rent:

(5.6) |

Competition ensures that the market price of gold bullion equalises with the natural price, and each portion of capital advanced in its production except the least productive one pays a differential rent, after as before the discovery of the new mine.

Combining (5.1), (5.5), and (5.6), the condition of the existence of a new permanent natural position reads:

(5.7) |

Since by construction the productivity of the least productive mine in the new permanent natural position is higher than that in the initial situation  condition (5.7) means that the total production of gold bullion is now permanently greater than before the discovery of the new mine, that is, the production of the newly discovered mine is greater than the combined previous production of the abandoned mines. Condition (5.7) is necessarily fulfilled because the demand for gold bullion (expressed in money) has remained unchanged. Since the new natural price (determined in mine

condition (5.7) means that the total production of gold bullion is now permanently greater than before the discovery of the new mine, that is, the production of the newly discovered mine is greater than the combined previous production of the abandoned mines. Condition (5.7) is necessarily fulfilled because the demand for gold bullion (expressed in money) has remained unchanged. Since the new natural price (determined in mine  ) is lower than the initial one (determined in mine k which has been abandoned), the total quantity produced at the new natural price and facing this unchanged money demand is necessarily higher. As emphasised in the above comparison between corn and gold, this greater quantity will be absorbed in the circulation of the gold-importing country at a lower value to circulate the unchanged aggregate value of commodities. Before examining how this occurs, it may be useful to illustrate the consequences of the discovery of a new mine with a numerical example derived from that used by Ricardo when he analysed the effect of taxes on gold.

) is lower than the initial one (determined in mine k which has been abandoned), the total quantity produced at the new natural price and facing this unchanged money demand is necessarily higher. As emphasised in the above comparison between corn and gold, this greater quantity will be absorbed in the circulation of the gold-importing country at a lower value to circulate the unchanged aggregate value of commodities. Before examining how this occurs, it may be useful to illustrate the consequences of the discovery of a new mine with a numerical example derived from that used by Ricardo when he analysed the effect of taxes on gold.

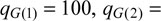

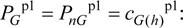

Let me assume an initial situation in which three mines 1, 2, 3 are worked  , where the same capital invested in each produces respectively

, where the same capital invested in each produces respectively

A new mine z is then discovered, which by assumption produces

A new mine z is then discovered, which by assumption produces  The question is asked of the conditions under which a new permanent natural position may exist such that, with mine 3 being closed, mines 1 and 2 plus mine z produce together a quantity of gold which sells at a market price equal to the new natural price, equal to the cost of production in mine 2. This new natural position exists if the quantity produced by the newly discovered mine z is such that, in application of equation (5.7):

The question is asked of the conditions under which a new permanent natural position may exist such that, with mine 3 being closed, mines 1 and 2 plus mine z produce together a quantity of gold which sells at a market price equal to the new natural price, equal to the cost of production in mine 2. This new natural position exists if the quantity produced by the newly discovered mine z is such that, in application of equation (5.7):

The quantity of gold being measured in ounces, suppose that

In the initial natural position, the total production of gold is 250, and

In the initial natural position, the total production of gold is 250, and  in pesos, the cost of production of one ounce of gold in the least productive mine (including a profit at the general rate). The demand for gold, expressed in price, is consequently equal to 250

in pesos, the cost of production of one ounce of gold in the least productive mine (including a profit at the general rate). The demand for gold, expressed in price, is consequently equal to 250  and the cost of production in the two other mines is (70/80)

and the cost of production in the two other mines is (70/80)  in mine 2 and (70/100)

in mine 2 and (70/100)  in mine 1. A new mine z is then discovered, which, with the same capital as that advanced in each of the previous mines, produces

in mine 1. A new mine z is then discovered, which, with the same capital as that advanced in each of the previous mines, produces  hence at a cost of production of (70/105.7)

hence at a cost of production of (70/105.7)  Tables 5.1 and 5.2 sum up the natural positions before and after the discovery of the new mine.

Tables 5.1 and 5.2 sum up the natural positions before and after the discovery of the new mine.

After the discovery of mine z, the four mines produce together 355.7 ounces, and the market price of gold falls consequently to  Capital invested in mine 3 at a cost

Capital invested in mine 3 at a cost  ceases to be profitable and is withdrawn. One observes that capital invested in mine 2 is also unprofitable at this level of the market price, since it produces at a cost equal to

ceases to be profitable and is withdrawn. One observes that capital invested in mine 2 is also unprofitable at this level of the market price, since it produces at a cost equal to  higher than the market price 0.7

higher than the market price 0.7  However, assuming the successive withdrawal rule, mine 2 remains worked if, after the closure of mine 3, capital invested in it is still profitable. After the closure of mine 3, the total production falls to 285.7 and the market price rises again at

However, assuming the successive withdrawal rule, mine 2 remains worked if, after the closure of mine 3, capital invested in it is still profitable. After the closure of mine 3, the total production falls to 285.7 and the market price rises again at  equal to the cost of production in mine 2, which consequently sets the new level of the natural price of gold. By comparison with the initial natural position, the total production of gold has increased from 250 to 285.7 ounces and the natural price has fallen from

equal to the cost of production in mine 2, which consequently sets the new level of the natural price of gold. By comparison with the initial natural position, the total production of gold has increased from 250 to 285.7 ounces and the natural price has fallen from

Table 5.1 Natural position before the discovery of a new gold mine

|

Mine 1 |

Mine 2 |

Mine 3 |

Together |

Production of gold (in ounces) |

100 |

80 |

70 |

250 |

Cost of production per ounce (in pesos) |

|

|

|

|

Market and natural price per ounce (in pesos) |

|

Table 5.2 Natural position after the discovery of a new gold mine

Mine 1 |

Mine 2 |

Mine z |

Together |

|

Production |

100 |

80 |

105.7 |

285.7 |

Cost |

|

|

|

|

Price |

|

5.5 The adjustment in the gold-importing country: minting

From the foreign mine to importation

Importing goods produced abroad is an activity in which, as in any other, capital invested requires the natural rate of profit. This means that it may only be implemented permanently if the commodity imported is sold at a market price equal to its cost, including a rate of profit at the general level. In the gold-producing country, this condition is fulfilled if bullion sells at a natural price equal to the cost of production with the portion of capital that pays no rent. In the gold-importing country, the condition is that bullion sells at a natural price equal to the cost of importing it, including the rate of profit at the natural level in this country.

Let me call:

Natural price of an ounce of bullion in the gold-producing country, in pesos;

Natural price of an ounce of bullion in the gold-producing country, in pesos;

Market price of an ounce of bullion in the gold-producing country, in pesos;

Market price of an ounce of bullion in the gold-producing country, in pesos;

Natural price of an ounce of bullion in the gold-importing country, in pounds;

Natural price of an ounce of bullion in the gold-importing country, in pounds;

Market price of an ounce of bullion in the gold-importing country, in pounds;

Market price of an ounce of bullion in the gold-importing country, in pounds;

Legal price of an ounce of gold in coin in the gold-importing country, in pounds;

Legal price of an ounce of gold in coin in the gold-importing country, in pounds;

e: exchange rate of £1 against pesos;

r: Natural rate of profit in the gold-importing country during the time capital is invested in the importation and sale of bullion, in percentage;

parametric cost of transfer of bullion from the gold-producing to the gold-importing country, in percentage.

parametric cost of transfer of bullion from the gold-producing to the gold-importing country, in percentage.

The condition for gold bullion to be imported in England is that the cost of its purchase in Spanish America and of its transfer to England (including the natural rate of profit in England) should be inferior or equal to the price at which it is sold in the London market:

(5.8) |

As seen above, in the gold-producing country the natural position (in which every portion of capital earns the natural rate of profit in this country) is characterised by the equality between the natural price and the market price of gold bullion:

(5.2) |

Similarly, the existence of a natural position in the gold-importing country is characterised by such equality:

(5.9) |

To simplify, let me suppose that the only currency circulating in the gold-importing country is composed of full-bodied gold coins minted without seignorage and being legal tender for  per ounce of gold in coin.16 The condition of conformity of money to the standard (gold bullion) has been defined in Chapter 3 above as:

per ounce of gold in coin.16 The condition of conformity of money to the standard (gold bullion) has been defined in Chapter 3 above as:

(3.9) |

“In a sound state of the currency” condition (5.9) may thus be rewritten as:

(5.10) |

Let me suppose that, before the discovery of a new mine in Spanish America, condition (5.10) is not fulfilled, so that gold bullion is not imported in England. This means that, given the natural price of bullion in Spanish America, the monetary conditions and/or the cost of transfer to England do not allow bullion to be profitably exported to this country (while it may be to others). The natural situation in time 0 is thus such that:

(5.11) |

The question is now: do things change after a new highly productive gold mine has been discovered in time 1? As indicated above, the increase in the total production of bullion sinks its market price  and I will assume that at this level the cost of imported bullion falls below its price in the London market, so that importation begins:

and I will assume that at this level the cost of imported bullion falls below its price in the London market, so that importation begins:

(5.12) |

However, this importation will only become permanent if, after the adjustment has been completed in Spanish America (through the closure of some mines) and in England (as a consequence of the import), it is consistent with the new natural position in both countries. As noted above, since gold bullion is not directly or indirectly a wage-good, the natural rate of profit r in England is not affected. The import in England has only two effects: in the gold market the price  is lowered, and in the foreign exchange market the demand for pesos against pounds by the importers to finance their purchases of bullion or by the exporters to return the proceeds of their sales lowers the exchange rate e of the pound in pesos. This double adjustment is all the more active since with inequality (5.12) capital invested in the importation of gold earns extra profits and additional capital is diverted to it from other employments. This adjustment at both ends stops when (5.9) applies to the new natural price in Spanish America, given by (5.6) above:

is lowered, and in the foreign exchange market the demand for pesos against pounds by the importers to finance their purchases of bullion or by the exporters to return the proceeds of their sales lowers the exchange rate e of the pound in pesos. This double adjustment is all the more active since with inequality (5.12) capital invested in the importation of gold earns extra profits and additional capital is diverted to it from other employments. This adjustment at both ends stops when (5.9) applies to the new natural price in Spanish America, given by (5.6) above:

(5.13) |

In this new natural position, gold bullion is permanently imported in England from Spanish America, as would any foreign commodity experiencing a reduction in its cost of production after the introduction of a new technique. Equation (5.13) simply applies Ricardo’s already mentioned contention that the price of a commodity in an importing country is regulated by its natural price in the exporting country.

However, gold was not any commodity.

Being the standard of money in England, gold was there the only commodity which besides its market price in bullion had also a legal price in coin. In contrast with any other commodity, equation (5.13) generated by the international adjustment is not the end of the story, as long as the resulting market price  is below the legal price

is below the legal price  Another arbitrage then exists for the owners of imported bullion, between the market and the mint: finding that it is profitable to have it coined, they carry it to the mint, and the reduction of the supply in the bullion market raises its price until it equalises with

Another arbitrage then exists for the owners of imported bullion, between the market and the mint: finding that it is profitable to have it coined, they carry it to the mint, and the reduction of the supply in the bullion market raises its price until it equalises with  and accordingly fulfils the condition of conformity (3.9). Practically, both arbitrages occurred simultaneously, the importers of bullion having the choice of selling it in the market or to the mint. The outcome of the complete adjustment was that the whole quantity of bullion imported nourished an increased quantity of money, because coining only stopped when the difference between

and accordingly fulfils the condition of conformity (3.9). Practically, both arbitrages occurred simultaneously, the importers of bullion having the choice of selling it in the market or to the mint. The outcome of the complete adjustment was that the whole quantity of bullion imported nourished an increased quantity of money, because coining only stopped when the difference between  and

and  was eliminated.

was eliminated.