6 The depreciation of metallic money

We all know that it is the melting pot only which keeps all currency in a wholesome state.

(Letter to Pascoe Grenfell, 19 January 1823; in Deleplace, Depoortère and Rieucau 2013: 4)

The starting point of the present chapter and of the next one is a consequence of the Money–Standard Equation analysed in Chapter 4 above: a monetary shock was transmitted indirectly to the prices of all commodities, through a change in the market price of the standard (gold bullion). Discussing in High Price the possibility “to carry the law against melting or exporting of coin into strict execution” (see below), Ricardo mentioned the case of:

[A] real depreciation of our currency, raising the prices of all other commodities in the same proportion as it increased that of gold bullion.

(High Price, III: 56)

This sentence may be interpreted in two ways. The usual one, inspired by the Quantity Theory of Money, is to consider that, when the currency was depreciated, the prices of all commodities increased directly “in the same proportion”, including “that of gold bullion”. In contrast I will contend that Ricardo maintained that depreciation increased the price of gold bullion and through this channel raised “the prices of all other commodities in the same proportion”. The first task is thus to study what happened when, whatever the monetary shock, the market price of gold bullion departed from the legal price of gold in coin, and how this difference was transmitted to the prices of all other commodities. This will be done below in Section 6.1 and Section 6.2 respectively. After having thus clarified how a change in the market price of the standard affected the prices of all other commodities via a change in the value of money, it will be possible to analyse which kind of monetary shock affected the market price of the standard itself.

A monetary shock was an excess or deficiency in the aggregate quantity of money, which became inconsistent with the conformity of money to the standard – that is, with the equality between the market price of bullion and the legal price of the metal in coin. In a letter to Francis Horner of 5 February 1810 Ricardo listed four causes that might explain a situation in which the former was above the latter:

It appears then to me, that no point can be more satisfactorily established, than that the excess of the market above the mint price of gold bullion, is, at present, wholly, and solely, owing to the too abundant quantity of paper circulation. There are in my opinion but three causes which can, at any time, produce an excess of price such as we are now speaking of.

First, The debasement of the coins, or rather of that coin which is the principal measure of value.

Secondly, A proportion in the relative value of gold to silver in the market, greater than in their relative value in the coins.

Thirdly, A superabundance of paper circulation. By superabundance I mean that quantity of paper money which could not by any means be kept in circulation if it were immediately exchangeable for specie on demand.

I might add here a fourth cause. The severity of the law against the exportation of gold coins, but from experience we know that this law is so easily evaded, that it is considered by all writers on political economy, as operating in a very small degree on the price of gold bullion.

(VI: 1‒2)

The fourth cause – the legal prohibition of melting and exporting the domestic coin – will be considered below in Section 6.1 because it affects the working of the market for bullion. Among the three main causes of “the excess of the market above the mint price of gold bullion”, the first two might look like historical curiosities, even at the time of Ricardo. Since the gold recoinage of 1774 (see Chapter 1 above), gold coins were considered as undebased. The recoinage of silver coins went back to 1695‒1699, and some Anti-Bullionists contended that their debasement was responsible for the monetary disorder; but Ricardo emphasised that the gold coin, not the silver one, was “the principal measure of value”. In other words, gold was the actual standard of money, in spite of the legal double standard at the time of the Bullion Report – so that debasement was then irrelevant (see Chapter 2 above). As for the effect of “the relative value of gold to silver in the market”, it could be neglected (except in international relations, foreign countries being on a silver or a double standard) because of the de facto gold standard and the disposition of the Act of 1774 making silver coins legal tender up to £25 only (they were taken by weight above this sum). The currency reform of 1816 would reinforce this historical tendency, by establishing a de jure gold standard and making silver coins a token money, although the return to a legal double standard was again debated in the context of the resumption of convertibility in 1819‒1823 (see Chapter 2 above).

Nevertheless, it is worthwhile to analyse Ricardo’s treatment of the depreciation of a metallic money before concentrating on the question of the excess issue of notes in the next chapter, for two reasons. First, as the first pages of Chapter XXVII of Principles make clear, Ricardo considered that the debasement of coins and the excess issue of notes had the same effect on the depreciation of money and that debased coins and notes issued in excess were both subject to “the principle of limitation of quantity” (I: 353). This will be shown in Section 6.3 below. Second, the discussion of the double standard led Ricardo to warn against the power of the Bank of England to change the value of the currency at will – a recurrent complaint by him. This will be the object of Section 6.4.

6.1 Convertibility and adjustment in the market for bullion

In a mixed monetary system like that ruling before 1797 and after 1821, gold coins – supposedly full-bodied (undebased) – circulated side by side with Bank of England notes convertible into coin (I leave aside notes issued by country banks which were convertible into Bank of England notes; see Chapter 1 above). Two kinds of convertibility had then to be considered.

There was first convertibility both ways between metallic money (the gold coin) and its standard (gold bullion). The market price of bullion fluctuated with supply and demand between two fixed limits because two symmetrical operations ensured the convertibility of bullion into coin and of coin into bullion, as Ricardo called them in his “Notes on Trotter” in 1810:

Who has asserted that gold is an unvarying standard of value? There is no unvarying standard in existence. Gold is however unvarying with regard to that money which is made of gold, and this proceeds from it being at all times convertible without expence into such money, and also from money being again convertible into gold bullion.

(III: 391)

One operation was legal and public: the minting of bullion into coins at a fixed legal price. Although no seignorage was charged by the Royal Mint, which had the monopoly of coining, there was a small cost (around 0.5 per cent) borne by this operation, because the metal had to be assayed and the mint delivered the coins only after some time (usually two months), during which interest had to be paid on the funds borrowed to purchase the metal in the market. The second operation was illegal and private: the melting of coins, which was prohibited because it facilitated the export of gold – an operation also illegal, unless it concerned foreign coins or “sworn-off” gold, that is, bullion whose owner swore that it had been imported before. Every observer testified that this legislation was easily evaded:

But these gentlemen do not dispute the fact of the convertibility of coin into bullion, in spite of the law to prevent it. Does it not follow, therefore, that the value of gold in coin, and the value of gold in bullion, would speedily approach a perfect equality?

(Reply to Bosanquet; III: 211)

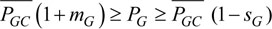

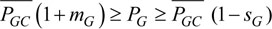

Recalling that the equality between the value of money (here gold in coin) and the value of its standard (gold bullion) was obtained when the market price of gold bullion was equal to the legal price of gold in coin (the condition of conformity established in Chapter 3 above), convertibility both ways between coin and bullion ensured that the market price of gold bullion was constrained between narrow limits around the legal price of gold in coin. The owner of an ounce of standard gold bullion had the choice between selling it in the market against coins at a price  and carrying it to the mint to obtain

and carrying it to the mint to obtain  in coins at a percentage cost sG equal to the rate of interest until the mint delivered the coins. This arbitrage permitted by the convertibility of bullion into coin determined a lower limit to the variation of

in coins at a percentage cost sG equal to the rate of interest until the mint delivered the coins. This arbitrage permitted by the convertibility of bullion into coin determined a lower limit to the variation of  equal to

equal to  if

if  fell below this limit, owners of bullion stopped offering it in the market and carried it to the mint; the reduction in the supply raised the price to

fell below this limit, owners of bullion stopped offering it in the market and carried it to the mint; the reduction in the supply raised the price to  The demander for gold bullion had the choice between buying it with coins in the market at

The demander for gold bullion had the choice between buying it with coins in the market at  and having his coins melted into bullion at a percentage cost

and having his coins melted into bullion at a percentage cost  This cost included that of the operation of the melting pot, the rate of interest until the bullion was delivered, and since melting was prohibited, the compensation for the risk of infringing the law, which depended on the severity of its enforcement. This arbitrage permitted by the convertibility of coin into bullion determined an upper limit to the variation of

This cost included that of the operation of the melting pot, the rate of interest until the bullion was delivered, and since melting was prohibited, the compensation for the risk of infringing the law, which depended on the severity of its enforcement. This arbitrage permitted by the convertibility of coin into bullion determined an upper limit to the variation of  , equal to

, equal to  if

if  rose above his limit, the owners of coins had them melted and offered the bullion in the market; the increased supply lowered the price to

rose above his limit, the owners of coins had them melted and offered the bullion in the market; the increased supply lowered the price to  Convertibility both ways between coin and bullion thus ensured that:

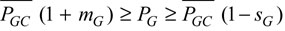

Convertibility both ways between coin and bullion thus ensured that:

|

(6.1) |

Inequalities (6.1) applied if circulating coins were full-bodied. If they were debased, an additional cost had to be borne when they were converted into bullion, reflecting the rate of debasement (see Section 6.3 below). This raised pro tanto the upper limit of variation of

The second convertibility was between the Bank of England note and the coin, and after 1821 as before 1797 it was only one-way. The Bank was compelled by law to deliver on demand and at no cost full-bodied coins against an equal quantity of its notes. But it was not compelled to issue notes against coins or bullion brought to it. When the Bank judged necessary to enlarge its reserve in coins, it purchased bullion at the market price and had it coined by the mint. In other words, notes could be converted at a fixed price into bullion, through exchanging them at no cost at the Bank against coins and melting the coins at the cost  Bullion could not be converted into notes at a fixed price but only into coins at the mint. Convertibility of the Bank of England note into coin consequently played no role for the lower limit of variation in the market price of gold bullion but only for its upper limit. And it did so also through the melting pot, into which coins obtained from the Bank against notes were poured.

Bullion could not be converted into notes at a fixed price but only into coins at the mint. Convertibility of the Bank of England note into coin consequently played no role for the lower limit of variation in the market price of gold bullion but only for its upper limit. And it did so also through the melting pot, into which coins obtained from the Bank against notes were poured.

Inequalities (6.1) consequently determined the range of variation of the market price of gold bullion provided coins were convertible into bullion through the melting pot and bullion was convertible into coin through the mint, whether the Bank of England note was itself convertible into coin or not. However, the level of the parameters involved  depended on the monetary regime, and hence also the variability of the market price of gold bullion at both ends of inequalities (6.1).

depended on the monetary regime, and hence also the variability of the market price of gold bullion at both ends of inequalities (6.1).

The effect of the melting pot on the upper limit of variation in the market price of bullion

As Ricardo put it in a letter to Grenfell of 19 January 1823 where he discussed the prospect of depreciation if the double standard were adopted in a system having resumed convertibility of the Bank of England note:

We all know that it is the melting pot only which keeps all currency in a wholesome state.

(Deleplace, Depoortère and Rieucau 2013: 4)

Were the note inconvertible, as was the case between 1797 and 1819, the melting pot would still play a role to convert notes issued in excess into bullion, as long as there were still coins in circulation purchased with notes with a view to melting them. An additional cost had to be borne to purchase the coins with depreciated notes from money-changers. The situation was the same as that of a pure metallic circulation when the coin was debased: the upper limit of variation of  was raised pro tanto.

was raised pro tanto.

When convertible notes circulated side by side with coins,  rated in notes could not differ from

rated in notes could not differ from  rated in coins, since notes might always be exchanged at par for undebased coins at the Bank. If an increase in the quantity of notes issued pushed

rated in coins, since notes might always be exchanged at par for undebased coins at the Bank. If an increase in the quantity of notes issued pushed  to

to  – notes were depreciated – the buyer of bullion could not insist on paying a lower price in coins, because the only alternative he had to obtain bullion was to have his coins melted at the same price

– notes were depreciated – the buyer of bullion could not insist on paying a lower price in coins, because the only alternative he had to obtain bullion was to have his coins melted at the same price  The market price of gold bullion was thus the same whether the transaction was paid for in convertible notes or in coins. Neglecting the costs of minting and of melting, one ounce of gold bullion consequently exchanged for one ounce of gold in coin or the quantity of convertible notes representing one ounce of gold in coin. In the case of an excess quantity of notes issued, the adjustment process did not eliminate the excess in totality because melting had a cost and it stopped when

The market price of gold bullion was thus the same whether the transaction was paid for in convertible notes or in coins. Neglecting the costs of minting and of melting, one ounce of gold bullion consequently exchanged for one ounce of gold in coin or the quantity of convertible notes representing one ounce of gold in coin. In the case of an excess quantity of notes issued, the adjustment process did not eliminate the excess in totality because melting had a cost and it stopped when  was equalised by arbitrage with

was equalised by arbitrage with  not with

not with  As mentioned by Ricardo in his letter to Horner of 5 February 1810 quoted at the beginning, the legal prohibition of melting and exporting the coin could thus be responsible for a depreciation of money.

As mentioned by Ricardo in his letter to Horner of 5 February 1810 quoted at the beginning, the legal prohibition of melting and exporting the coin could thus be responsible for a depreciation of money.

For the sake of argument, Ricardo sometimes assumed that the law was strictly enforced, so that the market price of gold bullion, paid for in coins, might be as high as twice the legal price of gold in coin:

Were it possible to carry the law against melting or exporting of coin into strict execution, at the same time that the exportation of bullion was freely allowed, no advantage could accrue from it, but great injury must arise to those who might have to pay, possibly, two ounces or more of coined gold for one of uncoined gold. This would be a real depreciation of our currency, raising the prices of all other commodities in the same proportion as it increased that of gold bullion. The owner of money would in this case suffer an injury equal to what a proprietor of corn would suffer, were a law to be passed prohibiting him from selling his corn for more than half its market value. The law against the exportation of the coin has this tendency, but it is so easily evaded, that gold in bullion has always been nearly of the same value as gold in coin.

(High Price, III: 56)

Were the law strictly enforced, it could possibly double the market price of gold bullion purchased with gold coins, because, bullion being freely exportable, those who would like to obtain it with a view to exportation would have to pay a high premium to compensate for the risk of fraud. This hypothetical case materially applied to inconvertible bank notes, which could be neither converted into bullion nor exported:

Now a paper circulation, not convertible into specie, differs in its effects in no respect from a metallic currency, with the law against exportation strictly executed.

(Reply to Bosanquet; III: 194)

Even with convertible notes, the legal prohibition of melting and exporting the coin opened a small margin of depreciation of money and this was the reason why Ricardo consistently advocated the repeal of this legislation. In his Ingot Plan, convertibility of notes into bullion completely eliminated  and prevented the market price of the standard from rising above its legal price (see Chapter 9 below).

and prevented the market price of the standard from rising above its legal price (see Chapter 9 below).

The effect of seignorage on the lower limit of variation in the market price of bullion

At the other end of inequalities (6.1), the existence of a minting cost sG opened a margin of appreciation of money, hence of a general fall in prices. Although Ricardo generally advocated the equality of the market price of the standard with its legal price – the condition of conformity mentioned in Chapter 3 above – he was in favour of such seignorage, provided it was small. As he wrote in Principles:

To a moderate seignorage on the coinage of money there cannot be much objection.

(I: 371)

Being examined by the Secret Committee on Resumption on 4 March 1819, he had first recommended the possibility to obtain immediately the gold coin against bullion at the mint (V: 380, 387), instead of the then delivery at two months’ notice which because of the loss of interest implied what “may strictly be called a small seignorage” (ibid: 402). In an unusual manner, he asked to be again examined on 19 March and, probably to be correctly understood, he delivered a written paper. He stood to his former answer “as far as regards our circulation” (ibid: 401), but he wanted “to amend” it by stressing an inconvenience linked to the absence of seignorage: “a great inducement offered to all exporters of gold, to exchange their bullion for coin previously to its exportation” (ibid), since the advantages of the coins (certified fineness, divisibility) would no longer be compensated by the cost of obtaining them. Ricardo’s proposal was the following:

If it be decided, that under all circumstances, a currency, partly made up of gold coin, is desirable, the most perfect footing on which it could be put, would be to charge a moderate seignorage on the gold coin, giving at the same time the privilege to the holder of bank notes, to demand of the bank, either gold coin or gold bullion at the mint price, as he should think best.

(ibid: 402)

This was the proposal made in Principles (see I: 372 and also V: 429, 431) However, even “moderate”, a seignorage on a coin “has also its inconveniences” (V: 402), as shown by (6.1): it opened a margin of fall in the market price of bullion – hence also in all other prices – when the Bank of England contracted its issues. Ricardo’s conclusion was straightforward:

I am still of opinion, that we should have all its advantages [of a seignorage], with the additional one of economy, by adopting the plan, which I had the honour of laying before the Committee when I was last before them.

(ibid: 403)

This was of course the Ingot Plan, in which the currency (bank notes exclusively) was to be obtained from the Bank against standard bullion at £3. 17s. 6d. per ounce, 0.5 per cent below the price at which it was legal tender – a difference sufficient to cover the cost of management of the currency while maintaining at a trifling level the margin of fall in the market price of bullion (see Chapter 9 below).

6.2 Price adjustment in the markets for other commodities than bullion

The effect of a change in the value of money on the competition of capitals

The question of price adjustment has already been evoked in Chapter 3 above, when I discussed the relation between the standard of money and the standard of value in Ricardo. We saw that around 1815 Ricardo became conscious that the understanding of commodity price required the coordination between two theories: a theory of value and distribution – which he started to envisage in his Essay on Profits, published in February 1815 – and a theory of money – the foundations of which he gave in Proposals for an Economical and Secure Currency, published in February 1816. This requirement was expressed in the letter to Malthus of 27 June 1815:

It appears to me that there are two causes which may cause a rise of prices, – one the depreciation of money, the other the difficulty of producing.

(VI: 233)

Six months later, Ricardo emphasised the difficulty of the task of writing what would become Principles, in the letter to Mill of 30 December 1815 discussed in Chapter 3:

I know I shall be soon stopped by the word price, and then I must apply to you for advice and assistance. Before my readers can understand the proof I mean to offer, they must understand the theory of currency and of price.

(VI: 348)

It should be recalled that the “two causes” of price mentioned in the letter to Malthus – which became in the letter to Mill the “two ways” the prices of commodities were affected – are not to be confused with the “two causes” of “relative value” (“the relative quantity of labour” and “the rate of profit”), mentioned by Ricardo in a well-known letter to McCulloch of 13 June 1820, which concerned the determination of the exchangeable value, that is, the second cause of price in the letter to Malthus (“the difficulty of producing”).1

The distinction between the respective effects on the price of any commodity of its exchangeable value and of the value of money was central for Ricardo’s analysis of the distribution of income, when this distinction was applied to the price of wage-goods. If the price of corn increased as a consequence of a fall in the value of money, the rate of profit remained undisturbed, since only money wages rose, not real wages. On the contrary, if the price of corn increased as a consequence of a rise in its exchangeable value, the rate of profit declined, real wages having increased.2 This was a central proposition of Principles:

It has been my endeavour carefully to distinguish between a low value of money, and a high value of corn, or any other commodity with which money may be compared. These have been generally considered as meaning the same thing; but it is evident, that when corn rises from five to ten shillings a bushel, it may be owing either to a fall in the value of money, or to a rise in the value of corn. Thus we have seen, that from the necessity of having recourse successively to land of a worse and worse quality, in order to feed an increasing population, corn must rise in relative value to other things. If therefore money continue permanently of the same value, corn will exchange for more of such money, that is to say, it will rise in price. The same rise in the price of corn will be produced by such improvement of machinery in manufactures, as shall enable us to manufacture commodities with peculiar advantages: for the influx of money will be the consequence; it will fall in value, and therefore exchange for less corn. But the effects resulting from a high price of corn when produced by the rise in the value of corn, and when caused by a fall in the value of money, are totally different. In both cases the money price of wages will rise, but if it be in consequence of the fall in the value of money, not only wages and corn, but all other commodities will rise. If the manufacturer has more to pay for wages, he will receive more for his manufactured goods, and the rate of profits will remain unaffected. But when the rise in the price of corn is the effect of the difficulty of production, profits will fall; for the manufacturer will be obliged to pay more wages, and will not be enabled to remunerate himself by raising the price of his manufactured commodity.

(Principles; I: 145‒6)3

The distinction between the two ways the price of any commodity could vary had an important consequence: a change in the “difficulty of producing” a commodity affected its price and only it, while a change in the value of money affected all prices:

This, I apprehend, is the correct account of all permanent variations in price, whether of corn or of any other commodity. A commodity can only permanently rise in price, either because a greater quantity of capital and labour must be employed to produce it, or because money has fallen in value; and, on the contrary, it can only fall in price, either because a less quantity of capital and labour may be employed to produce it, or because money has risen in value. A variation arising from the latter of these alternatives, an altered value of money, is common at once to all commodities; but a variation arising from the former cause, is confined to the particular commodity requiring more or less labour in its production.

(ibid: 417)

A change in the value of money not only affected all prices, but it did so in the same proportion:

If a country were not taxed, and money should fall in value, its abundance in every market would produce similar effects in each. If meat rose 20 per cent., bread, beer, shoes, labour, and every commodity, would also rise 20 per cent.; it is necessary they should do so, to secure to each trade the same rate of profits.

(ibid: 209)4

The role of what Ricardo called “the competition of capitals” in the fact that a change in the value of money induced an opposite and proportional change in all prices focused on the behaviour of the sellers in the fixation of prices, because it was on this side that capital moved from one employment to another. In a letter to Malthus of 9 October 1820, Ricardo criticised Say for contending that buyers “regulated the value of commodities”:

He [Say] certainly has not a correct notion of what is meant by value, when he contends that a commodity is valuable in proportion to its utility. This would be true if buyers only regulated the value of commodities; then indeed we might expect that all men would be willing to give a price for things in proportion to the estimation in which they held them, but the fact appears to me to be that the buyers have the least in the world to do in regulating price – it is all done by the competition of the sellers, and however the buyers might be really willing to give more for iron, than for gold, they could not, because the supply would be regulated by the cost of production, and therefore gold would inevitably be in the proportion which it now is to iron, altho’ it probably is by all mankind considered as the less useful metal.

(VIII: 276‒7)

From the market price of bullion to the market prices of commodities

Since gold bullion was the standard of money, the seller of any commodity i sold it for a quantity of pounds – the price Pi – equivalent to a certain quantity of gold bullion. The exchangeable value of commodity i in gold bullion was translated into its price Pi in pounds thanks to the legal definition of the pound as a quantity of gold. In circulation commodity i exchanged at price Pi for the required quantity of gold in full-bodied coins or in notes convertible into full-bodied coins. If circulating coins were debased or convertible notes were in excess, this was reflected in a market price of gold bullion above the legal price of gold in coin (the circulating medium was depreciated), and the sellers raised their prices by the amount of this spread. If the market price of gold bullion fell below the legal price of gold in coin (the circulating medium was appreciated) competition forced the sellers to lower their prices. The market for gold bullion thus triggered a change in prices generated by a change in the value of money, and, because of the competition of capitals for the general rate of profit, all sellers of commodities passed the change in the value of money on to their prices in the same proportion, leaving relative prices unaltered.

This price adjustment occurred whatever the circumstances leading to such change in the value of money. It also applied when the circulating medium was composed of inconvertible notes, and it is how it was described by Ricardo in the Bullion Essays:

The effect produced on prices by the depreciation has been most accurately defined [by the Bullion Committee], and amounts to the difference between the market and the mint price of gold. An ounce of gold coin cannot be of less value, the Committee say, than an ounce of gold bullion of the same standard; a purchaser of corn therefore is entitled to as much of that commodity for an ounce of gold coin, or 3l. 17s. 10½d., as can be obtained for an ounce of gold bullion. Now, as 4l.12s. of paper currency is of no more value than an ounce of gold bullion, prices are actually raised to the purchaser 18 per cent., in consequence of his purchase being made with paper instead of coin of its bullion value. Eighteen per cent. is, therefore, equal to the rise in the price of commodities, occasioned by the depreciation of paper. All above such rise may be either traced to the effects of taxation, to the increased scarcity of the commodity, or to any other cause which may appear satisfactory to those who take pleasure in such enquiries.

(Reply to Bosanquet; III: 239)

If the notes were not depreciated – that is, if the market price of an ounce of gold bullion paid for in notes were equal to the legal price of an ounce of gold in coin (£3. 17s. 10½d.) – a given quantity of corn having a relative value of an ounce of gold bullion would exchange for £3. 17s. 10½d. in notes. But the actual situation was such that notes were depreciated by 18 per cent, as testified by the fact that an ounce of gold bullion was paid for in notes at a price of £4. 12s. The relative value of the given quantity of corn in terms of gold bullion remained an ounce if it now exchanged for £4. 12s. in depreciated notes. The 18 per cent increase in the market price of gold bullion (as compared with a situation of no-depreciation) was thus translated into an 18 per cent increase in the market price of corn. The same applied to any other commodity – “Eighteen per cent. is, therefore, equal to the rise in the price of commodities, occasioned by the depreciation of paper” – so as to preserve the uniformity of the rate of profit on all portions of capital.

One should observe that this price increase occurred whether the commodity was paid for in notes or in undebased coins, because the whole money was depreciated: the coin partook in the depreciation of the note issued in excess. As explained by Ricardo:

If an addition be made to a currency consisting partly of gold and partly of paper, by an increase of paper currency the value of the whole currency would be diminished, or, in other words, the prices of commodities would rise, estimated either in gold coin or in paper currency. The same commodity would purchase, after the increase of paper, a greater number of ounces of gold coin, because it would exchange for a greater quantity of money.

(ibid: 210‒11)

After as before depreciation there was one price only for each commodity, whether the circulating medium used to pay for it was paper or metallic money. Since, according to (6.1), the upper limit of the market price of gold bullion, paid for in depreciated notes, was the legal price of gold in coin plus the melting cost, it was indifferent to the seller of gold to be paid £4. 12s. in notes, with which he could purchase an ounce of gold bullion in the market, or £4. 12s. in undebased coins, which he could melt at 18 per cent cost to obtain the same ounce of gold bullion.

A bullion-price channel of transmission of a monetary shock

The same adjustment of the market prices of commodities to changes in the market price of gold bullion was mentioned in the papers of 1819‒1823, as in the speech in Parliament of 12 June 1822 already quoted in Chapter 4 above, which considered what happened when, after the note had been depreciated (and prices had risen accordingly), the market price of gold bullion fell back to the unchanged level of the legal price of gold in coin:

If, for instance, the standard of the currency remained at the same fixed value, and the coin were depreciated by clipping, or the paper money by the increase of its quantity, five per cent, a fall to that amount and no more, would take place in the price of commodities, as affected by the value of money. If the metal gold (the standard) continued of the same precise value, and it was required to restore the currency thus depreciated five per cent, to par, it would be necessary only to raise its value five per cent, and no greater than that proportionate fall could take place in the price of commodities.

(V: 204)

It was the business of bullion traders to be at all times informed about the market price  of gold bullion – all the more so since in London it was fixed every Tuesday and Friday by the main houses in this trade, such as Mocatta and Goldsmid – and arbitrage with the legal price of gold in coin

of gold bullion – all the more so since in London it was fixed every Tuesday and Friday by the main houses in this trade, such as Mocatta and Goldsmid – and arbitrage with the legal price of gold in coin  was thus immediate. One may think that this deviation of

was thus immediate. One may think that this deviation of  from

from  had to continue for some time before the sellers of all other commodities understood that the currency for which they traded them was depreciated (or appreciated) and adjusted their prices accordingly. However, Ricardo maintained that this lag was not great. Being examined by the House of Lords Committee on Resumption on 26 March 1819, he answered to questions on this point as follows:

had to continue for some time before the sellers of all other commodities understood that the currency for which they traded them was depreciated (or appreciated) and adjusted their prices accordingly. However, Ricardo maintained that this lag was not great. Being examined by the House of Lords Committee on Resumption on 26 March 1819, he answered to questions on this point as follows:

Question: Do the prices of commodities conform to the fluctuations in the market price of gold, or does not a length of time elapse before such conformity takes place?

Answer: They do not immediately conform, but I do not think it very long before they do.

Question: If the prices of commodities have not already fallen to a level with the present market price of gold, is it certain there will not be a greater reduction in their prices than 4 per cent., on the market price of gold falling to the mint price?

Answer: I think the prices of commodities fall from a reduction of the paper circulation quite as soon as gold falls.

(V: 452)

Let me now sum up the question of price adjustments as it may be understood up to this point in Ricardo. In the market for gold bullion, convertibility both ways between this standard of money and metallic money (the coin) and convertibility one-way between paper money (the Bank of England note) and metallic money generated a specific adjustment of the market price to the legal price of gold in coin which constrained the former in a given margin around the latter (inequalities (6.1) above). In the markets for all other commodities, prices responded in the same proportion to any deviation of the market price of gold bullion from the legal price of gold in coin. Since, as will be analysed in Chapter 7 below, an excess or a deficiency in the note issue was the primary cause of such (respectively positive or negative) deviation, a monetary shock was transmitted to the prices of all commodities through a change in the market price of gold bullion: an excess in the note issue caused a proportional rise in all prices and a deficiency a proportional fall. This bullion-price channel of transmission of a monetary shock to the value of money hence to commodity prices contrasts other transmission channels attributed to Ricardo in modern literature, based on the real-balance effect or the rate of interest. This point will be discussed in Appendix 7 below.

Before analysing in the next chapter the adjustment to an excess note issue, I will consider the two other monetary shocks mentioned by Ricardo: the debasement of the coin and a change in the relative price of gold to silver in a double-standard system.

6.3 Debasement of the coin and depreciation of money

The effect of debasement on the market price of gold bullion

In Chapter 5 above I showed that a theory of a monetary system endowed with a standard, as it was developed by Ricardo from Proposals for an Economical and Secure Currency onwards, implied discarding the “analogy” (made by Ricardo in the Bullion Essays) between the discovery of a new gold mine and a discretionary increase in the note issue. Another analogy was more appropriate, between debased coins and Bank of England notes issued in excess. That both circumstances had the same effect was contended by Ricardo in his speech of 12 June 1822 quoted in Chapter 4 and again above in Section 6.2: “If, for instance, the standard of the currency remained at the same fixed value, and the coin were depreciated by clipping, or the paper money by the increase of its quantity, five per cent […]” (V: 204). Such analogy did not point to a circumstance affecting the standard of money – such as the discovery of a new gold mine – but to one affecting metallic money itself: its debasement.

The interpretation by Ricardo of the debasement of the coins in terms of depreciation of the currency was already to be found in the Bullion Essays:

The public has sustained, at different times, very serious loss from the depreciation of the circulating medium, arising from the unlawful practice of clipping the coins.

(High Price; III: 69)

The same statement was repeated in the mature monetary writings, as in a letter to McCulloch dated 2 October 1819: “The depreciation of the currency is inferred as a necessary consequence of a clipped coin” (VIII: 90). More details were given in the speech of 12 June 1822, where Ricardo criticised the opinion of one of his colleagues in Parliament:

Suppose the only currency in the country was a metallic one, and that, by clipping, it had lost 10 per cent of its weight; suppose, for instance, that the sovereign only retained 9-10ths of the metal which by law it should contain, and that, in consequence, gold bullion, in such a medium, should rise above its mint price, would not the money of the country be depreciated? He was quite sure the hon. alderman would admit the truth of this inference.

(V: 203)

One of the reasons of Ricardo’s constancy on this question is that it was disputed by nobody, as suggested by the end of the quotation. The causal relation between the debasement of the coins and a high market price of gold bullion was generally admitted at the time of Ricardo and had been established with great clarity by James Steuart more than forty years before in his Principles of Political Economy of 1767.5 It was precisely this relation which led some Anti-Bullionists to deny an excess issue of Bank of England notes any responsibility in the high price of bullion and to explain it by the debasement of the coins. As seen in Chapter 2 above, Ricardo opposed them not on the general effect of debasement on the market price of bullion but on its relevance in the circumstances of the time, the divergence being about “that coin which is the principal measure of value” (VI: 2) – the gold or the silver one – Ricardo arguing that it was the gold one and that it was not debased.

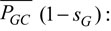

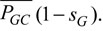

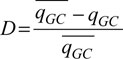

The relation between debasement and depreciation may be formalised as follows. Supposing gold is the standard, let  be the intrinsic weight of the standard coin “fresh from the mint” (undebased), that is, the quantity of gold (measured in ounces) legally contained in it, and

be the intrinsic weight of the standard coin “fresh from the mint” (undebased), that is, the quantity of gold (measured in ounces) legally contained in it, and  the quantity of gold contained in the average circulating coin of the same denomination, with

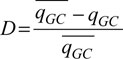

the quantity of gold contained in the average circulating coin of the same denomination, with  One may define the rate of debasement D as the percentage difference between the legal gold weight of the undebased coin and the actual average gold weight of the debased one:

One may define the rate of debasement D as the percentage difference between the legal gold weight of the undebased coin and the actual average gold weight of the debased one:

|

(6.2) |

Neglecting for the moment the coining and melting costs, let me suppose, as in the above quotation, that the average circulating coin is debased by D = 10 per cent, but the law is such that it passes indifferently with an undebased one. If the seller of an ounce of gold bullion is paid £3. 17s. 10½d. in such debased coins – that is, at a market price equal to the legal price of an ounce of gold in undebased coin – he really exchanges one ounce of gold bullion for 0.9 ounce of gold in coin. He may alternatively bring his bullion to the mint to have it coined in £3. 17s. 10½d. in undebased coins. The diminished supply of bullion in the market raises its price, until one ounce of gold bullion exchanges at this higher price for one ounce of gold in debased coins. This occurs when the market price of gold bullion is 10 per cent above the legal price of gold in coin. If this premium overtakes 10 per cent, the owner of debased coins, rather than buying bullion at that price, prefers to melt them to sell the bullion thus obtained. The increased supply of bullion in the market sinks its price, until the premium falls back to 10 per cent. Arbitrage thus sustains the market price of gold bullion above the legal price of gold in undebased coin, by a margin determined by the rate of debasement. In other words, £3. 17s. 10½d. in debased coin buy in the market 10 per cent less in gold bullion than it should according to the legal definition of the pound: measured in gold bullion, the debased currency is depreciated by 10 per cent and this depreciation continues as long as the average circulating coin remains debased by 10 per cent.

The relation between the rate of debasement and the rate of depreciation is as follows. By definition one ounce of gold contains  undebased coins, each one declared to be legal tender for £1, so that the legal price

undebased coins, each one declared to be legal tender for £1, so that the legal price  in pounds of one ounce of gold in undebased coins is given by:

in pounds of one ounce of gold in undebased coins is given by:

|

(6.3) |

In circulation, one ounce of gold contains  debased coins, each one being also legal tender for £1. The no-arbitrage condition in the market for gold bullion states that one ounce of gold bullion exchanges for one ounce of gold in debased coins, so that, with

debased coins, each one being also legal tender for £1. The no-arbitrage condition in the market for gold bullion states that one ounce of gold bullion exchanges for one ounce of gold in debased coins, so that, with  the market price in pounds of one ounce of gold bullion:

the market price in pounds of one ounce of gold bullion:

|

(6.4) |

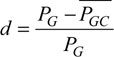

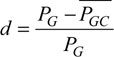

As seen in Chapter 4 above, the rate of depreciation d of money is equal to:

|

(4.2) |

Combining (6.2), (6.3), (6.4) and (4.2) gives:

|

(6.5) |

As stated by Ricardo in the above quotation, the higher the rate of debasement of the coin, the higher the rate of depreciation of money. It should be noticed that the level of depreciation of the currency entirely results from the no-arbitrage condition in the market for gold bullion. It does not depend on any relation between the quantity of money, its value, and the aggregate money price of all circulated commodities. This is consistent with the logic of the Money–Standard Equation analysed in Chapter 4 above, according to which the causal relation between the quantity of money and its value results – for a given value of the standard – from the causal relation between the quantity of money and the price of gold bullion.

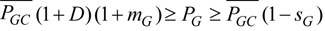

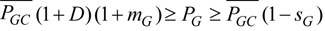

In practice convertibility of bullion into coin (minting) and of coin into bullion (melting) was costly: the delay to obtain the coin at the mint exposed the owner of bullion to a loss of interest; the legal prohibition of melting and exporting the coin exposed its owner to a melting cost that included the compensation paid to the intermediary for the risk of fraud. As seen in Section 6.1 above, the market price of gold bullion  could thus vary around the legal price

could thus vary around the legal price  of gold in undebased coin between narrow limits corresponding to

of gold in undebased coin between narrow limits corresponding to  the minting cost and

the minting cost and  the melting cost (both in percentage of the price):

the melting cost (both in percentage of the price):

|

(6.1) |

When the circulating coins were debased, the upper limit of the market price of gold bullion was augmented by the rate of debasement D:

|

(6.6) |

The rate of depreciation could now be greater than the rate of debasement, by a margin equal to the melting cost. When the circulation was composed of debased coins, they were all the more depreciated since their melting and exporting was legally prohibited.

Debasement and “the principle of limitation of quantity”

As noted earlier, there was no novelty in Ricardo’s statement of the causal relation between the debasement of the coins and a high price of gold bullion: such relation was currently recognised at the time. The singularity of Ricardo, however, is to be found in his interpretation of this relation as a particular case of application of “the principle of limitation of quantity” of money. This interpretation clearly shows up in Principles, in connection with the application of this principle to an excess issue of notes. According to Ricardo, when the circulation was composed of debased coins, the quantity of currency was also in excess. After having mentioned that an excess of paper money would generate an unfavourable exchange exactly proportional to that excess, he added:

To produce this effect it is not, however, necessary that paper money should be employed: any cause which retains in circulation a greater quantity of pounds than would have circulated, if commerce had been free, and the precious metals of a known weight and fineness had been used, either for money, or for the standard of money, would exactly produce the same effects. Suppose that by clipping the money, each pound did not contain the quantity of gold or silver which by law it should contain, a greater number of such pounds might be employed in the circulation, than if they were not clipped. If from each pound one tenth were taken away, 11 millions of such pounds might be used instead of 10; if two tenths were taken away, 12 millions might be employed; and if one half were taken away, 20 millions might not be found superfluous. If the latter sum were used instead of 10 millions, every commodity in England would be raised to double its former price, and the exchange would be 50 per cent. against England.

(Principles; I: 230‒1; my emphasis)

According to Ricardo, if debased coins were allowed to pass as undebased ones, this meant that the aggregate value in pounds borne by these coins was in excess as compared with what it would have been had the coins been undebased: a debasement of the coin was identical with an excess in the aggregate quantity of money. Consequently, diminishing the depreciation of the currency might be obtained by reducing the quantity of coins in circulation. The rationing of new (undebased) coins by the mint could not do, since, with a market price of bullion above the mint price, nobody brought bullion to the mint anyway. The reduction had to concern the debased coins, the circulation of which was in fact heterogeneous: some coins of old coinages were debased by wear and tear, as compared with more recent ones; some coins of a given coinage might have been clipped and weighed less than other coins of the same coinage. The State could then decide a partial recoinage, that is, to cry down the coins with a weight inferior to a certain limit: they stopped being legal tender and were received at the mint at their actual weight as bullion to be recoined. Rather than bringing them to the mint, their owners might prefer to melt them fraudulently and sell the bullion in the market at the higher price. The increase in the supply of bullion then made its market price fall. Thanks to the melting of the coins – although it was legally prohibited – the State had thus a tool to diminish the depreciation of the metallic currency. In equation (6.6), the reduction of the quantity of circulating coins by crying down the most debased ones amounted to diminish the average rate of debasement D and consequently the maximum rate of depreciation.

The parallelism between debased coins and notes issued in excess is explicitly made in Chapter XXVII of Principles, with the consequence that in both cases a limitation of the quantity of the currency may sustain its value:

While the State alone coins, there can be no limit to this charge of seignorage; for by limiting the quantity of coin, it can be raised to any conceivable value.

It is on this principle that paper money circulates: the whole charge for paper money may be considered as seignorage. Though it has no intrinsic value, yet, by limiting its quantity, its value in exchange is as great as an equal denomination of coin, or of bullion in that coin. On the same principle, too, namely, by a limitation of its quantity, a debased coin would circulate at the value it should bear, if it were of the legal weight and fineness, and not at the value of the quantity of metal which it actually contained. In the history of the British coinage, we find, accordingly, that the currency was never depreciated in the same proportion that it was debased; the reason of which was, that it never was increased in quantity, in proportion to its diminished intrinsic value.

(Principles; I: 353)

According to Ricardo, the limitation of the quantity of debased coins allowed to circulate (that is, as mentioned above, their partial recoinage) had historically maintained the actual depreciation of the metallic currency below its maximum rate equal to the sum of the debasement rate and of the melting cost. Nevertheless, even so contained, depreciation consequent upon debasement was harmful to a mixed monetary system of coins and convertible notes such as the one in England before 1797, for two reasons. First, as for the other causes of depreciation, an excess of the market price of gold bullion above the legal price of gold in coin made it possible to gain by arbitrage by melting the coins (although fraudulently) and exporting the bullion. Second, since the Bank of England was legally compelled to exchange its notes at par for undebased coins, it was not necessary for the arbitrager to gather in circulation the debased coins to be melted: he discounted bills for Bank notes, exchanged them at the gold window of the Bank for guineas “fresh from the mint”, had them melted, sold the bullion in the market and pocketed the difference. When the Bank had to purchase bullion at a high price in the market to have it coined at the mint and replenish its reserve, it bore the loss that was the counterpart of the arbitrager’s profit. The Bank then reacted by contracting its issues, with negative effects on the loan market and thus on economic activity in general. Both inconveniences – the export of bullion which dried up domestic circulation and the contraction of discounts by the Bank which disturbed the credit market – were also to be found when the depreciation of money was the outcome of an excess issue of notes and I will analyse them when discussing this question in the next chapter. When they were the consequences of debasement, the only permanent solution was its eradication through a general recoinage, with or without devaluation. There was, however, a more radical solution which was advocated by Ricardo as early as 1811, in the Appendix to the fourth edition of High Price: note convertibility into bullion rather than into specie, which amounted to eliminate the use of coins in circulation, and consequently their debasement. This solution will be studied in detail in Chapter 9 below.

6.4 The instability of the double standard

Ricardo constantly opposed the double standard from the Bullion Essays till his last writings. This opposition is to be found in High Price, in Chapter XXVII of Principles, and in an important letter of 19 January 1823 to Pascoe Grenfell recently discovered (see Appendix 6); it relied on two arguments. One was general and applied to any standard-based monetary system: the variability of the relative market price of gold in silver prevented a double standard from actually working and condemned the monetary system to the inconveniences of an alternating standard. The other argument was more specific to a monetary system in which part of the circulation was composed of Bank of England notes: the behaviour of the Bank could have the aggravating effect of triggering a fall in the value of money.

The variability of the relative market price of gold in silver and the alternating standard

In High Price Ricardo already opposed the double standard, on the ground of the unavoidable change in the effective standard that it would entail:

No permanent*6 measure of value can be said to exist in any nation while the circulating medium consists of two metals, because they are constantly subject to vary in value with respect to each other.

(High Price; III: 65)

It was so because the market ratio of the price of gold to that of silver was subject to changes, as for every commodity, whereas the relative value of gold and silver in the coins was legally fixed. Whenever the market ratio fell below the legal ratio, no one would bring silver to the mint to be coined, because it was more advantageous to sell it in the market for gold coins; gold became the “practical standard” (as it is labelled in the letter of 19 January 1823, in Deleplace, Depoortère and Rieucau 2013: 4). The opposite occurred when the market ratio rose above the legal ratio:

Not only would not gold be carried to the mint to be coined, but the illicit trader would melt the gold coin, and sell it as bullion for more than its nominal value in the silver coin. Thus then gold would disappear from circulation, and silver coin become the standard measure of value.

(High Price; III: 68)

Examined by a Lords committee on 24 March 1819, Ricardo produced figures, extracted from Mushet’s Tables, showing that in the 1770s and 1780s the market ratio had varied up to 15 per cent in the space of two or three years, and he concluded: “The greatest inconvenience would result in raising or lowering suddenly the value of the currency to so great an extent” (V: 427).

Therefore, although it was legally proclaimed, there could never be practically a double standard, except by chance when the market ratio happened to coincide with the legal ratio. One corollary was that, in such a monetary system, only one metal at a time could have a market price above its mint price. For example, if the market ratio was below the legal one, gold was the standard and consequently at or below its mint price, while silver was above it:

An excess in the market above the mint price of gold or silver bullion, may, whilst the coins of both metals are legal tender, and there is no prohibition against the coinage of either metal, be caused by a variation in the relative value of those metals; but an excess of the market above the mint price proceeding from this cause will be at once perceived by its affecting only the price of one of the metals. Thus gold would be at or below, while silver was above, its mint price, or silver at or below its mint price, whilst gold was above.

(High Price; III: 77)

According to Ricardo, this situation of a legal double standard working practically as an alternate single one operated until 1797.7 Although the relative value of gold in silver was such that gold was de facto the standard, an increase in this relative value could have promoted silver as the sole standard, and this possibility of change in the standard was enough for Ricardo to reject the legal double standard. One should observe that, according to him, silver could have become the standard, in spite of the fact that it was legal tender only up to £25. As explained in Principles:

[Before 1797] gold was in practice the real standard of currency. That it was so, is no where denied; but it has been contended, that it was made so by the law, which declared that silver should not be a legal tender for any debt exceeding 25l., unless by weight, according to the Mint standard. But this law did not prevent any debtor from paying his debt, however large its amount, in silver currency fresh from the Mint; that the debtor did not pay in this metal, was not a matter of chance, nor a matter of compulsion, but wholly the effect of choice; it did not suit him to take silver to the Mint, it did suit him to take gold thither.

(Principles; I: 368)

In fact, silver was not prevented by its restricted legal tender from being the standard because this restriction only applied to the debased coin; since the law authorized to pay any amount “by weight, according to the Mint standard”, that meant that full-bodied silver coins (“fresh from the Mint”) were full legal tender in the same way as were gold coins.8 Consequently, for silver becoming the standard, the important points were the legal possibility of paying by standard weight and the free access to the mint to obtain new silver coins, not the restricted legal tender of debased coins.

These two crucial provisions, which existed before 1797, disappeared in 1817. First “it was enacted that gold only should be a legal tender for any sum exceeding forty shillings” (ibid: 369), that is, silver was no longer legal tender above this sum, even by standard weight. Second, for contingent reasons (the market price of silver was then below the mint price of 5s. 2d., and the mint would have been flooded with silver bullion brought in for coinage), the royal proclamation implementing free access to the mint for silver was not issued (see Fetter 1965: 67). Both provisions reflected the secondary role devoted to silver in the monetary system: silver coins were de facto reduced to token currency.

After the resumption of Bank of England note convertibility into coin and at pre-war parity in 1821, this evolution was called into question by some influential persons – such as the financier Alexander Baring – who advocated a return to the double standard as a way to alleviate the deflation then experienced in England. But if the double standard was to be reintroduced, silver currency had to be again put on the same footing as the gold one. In the above-mentioned letter of 19 January 1823, Ricardo insisted on the fact that one could not avoid in that case granting again free access to the mint:

In the present state of the law the public cannot take silver to the mint to be coined, a very proper regulation while silver performs only the office of counters or tokens, but once make it the standard metal, & the mint must be open to the Bank, & the public.

(in Deleplace, Depoortère and Rieucau 2013: 4)

This reintroduction also implied the possibility of paying any sum in full-bodied silver coins to be enacted again (unrestricted legal tender). It seemed therefore that, if the legal double standard was to be reintroduced, the British monetary system would be put again in the state ruling before 1797, with the same inconveniences, namely the practical possibility of a change of standard in the course of time. According to Ricardo, however, the situation could be even worse, because of the issuing behaviour of the Bank of England.

The behaviour of the Bank of England and the prospective fall in the value of money

As mentioned in Chapter 2 above, the question of the double standard was raised in Parliament in 1819 during the debates on the resumption of convertibility of the Bank of England note. It was suggested to couple Ricardo’s proposal for convertibility into bullion with a double standard.9 Being examined on 24 March 1819 by a Lords’ committee, Ricardo was asked to give his opinion about the Bank of England having the choice of paying its notes either in gold bullion or in silver bullion, at a fixed ratio between them. He answered:

The greatest inconvenience would result from such a provision. I consider it a great improvement having established one of the metals as the standard for money. The Bank and all other debtors would naturally pay their debts in the metal which could at the time be most cheaply purchased, and at certain fixed periods the currency might be suddenly increased or lowered in value, in proportion to the variation in the relative value of the two metals from one of these periods to the other.

(V: 426)

Ricardo thus worried about the Bank having the power of changing the standard at will. The double-standard proposal resurfaced in 1821 when convertibility of the Bank of England note into coin and at pre-war parity was resumed, and Ricardo opposed it again publicly in a speech in Parliament on 19 March 1821:

The attempt to procure the best possible standard had been characterized by his hon. friend [Baring] as a piece of coxcombry to which he attached no value; but, in a question of finance, if we could get a better system than our neighbours, we were surely justified in adopting it. He [Ricardo] undoubtedly did wish for a better system, and it was for that reason that he wished to see one metal adopted as a standard of currency, and the system of two metals rejected.

(V: 95‒6)

When in 1823 the causes of the economic depression were again hotly debated, Ricardo deepened his argument against the double standard in a letter to Pascoe Grenfell (for more details, see Deleplace, Depoortère and Rieucau 2013). This time Ricardo worried about the Bank having the power of degrading the value of money at will, because of a recent new provision of the currency system: the seignorage on the silver coin.

After the Silver coinage Act adopted by Parliament in 1816 and proclaimed in 1817, the legal double-standard system, if again implemented, would not work in the same way as the pre-1797 one did. Indeed it would retain from the latter its general inconveniences but it would add a specific difficulty:

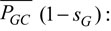

Since the new act for regulating the silver coinage, the execution of the plan will not be found so easy as the friends to it suppose. Formerly, when we had the two standards we were liable to the inconveniences of changing from one to the other, accordingly as one or the other of the metals became the cheapest medium whereby to discharge a debt, but whichever metal was for the time the practical standard that metal could not be under the mint price, whilst the other was always above it.– Now, however, with a seignorage on the silver currency, nothing is to prevent the price of silver from rising to 5/6 an ounce whilst it is the standard metal.

(in Deleplace, Depoortère and Rieucau 2013: 4)

As seen above, in the pre-1797 legal double-standard system (that is without seignorage), one metal only (whichever it was, gold or silver) could have a market price above its mint price: the one which was not the “practical standard” at the time. This had not more monetary consequence than for any ordinary commodity, since the currency was then attached to the other metal, which was at its mint price. With seignorage, one metal could have a market price above its mint price and remain the practical standard; therefore this rise did have a monetary consequence: a fall in the value of money. In the present circumstances that metal was silver, because since 1817 the silver coin bore a seignorage. There laid, according to Ricardo, the novelty of the new project of legal double-standard. The following question thus arises: Why did the existence of a seignorage on the silver coin – which Ricardo considered as a favourable provision in itself (see Section 6.1 above) – add a new inconvenience – no less than a 10 per cent fall in the value of the pound – to an already objectionable double-standard system? In other words, with a seignorage on the silver coin, why might the market price of silver rise up to 5s. 6d., signalling a fall of 10 per cent in the value of the pound, measured in this restored standard?

The answer is not straightforward. When Ricardo’s correspondent, Pascoe Grenfell, transmitted his letter to Lord Grenville, he wrote:

Ricardo seems to me to assume, that if that alteration [the double standard] takes place, the Mint price of Silver will be at the present current value of the Tokens – viz 66 – I take it for granted, however, that if we are to be implicated with this alteration, the Mint price – as standard will not exceed its old rate of 62.

(ibid: 22; Grenfell’s emphasis)

Obviously, Grenfell did not understand Ricardo’s argument: it is the market price of silver – not its mint price – which Ricardo assumed to rise up to 66 pence (5s. 6d.), that is, the appropriate measure of the current value of the pound – not its legal one – expressed in this standard. But why such a rise? It is interesting to notice that, in his speech of 8 February 1821 when he already opposed Baring’s double-standard proposal, Ricardo himself had mentioned 62 pence (5s. 2d.) as the market price of silver which would result from that proposal:

With respect to his hon. friend’s [Baring] recommendation of a double tender, it was obvious, that if that recommendation were adopted, the Bank [of England], although it seldom saw its own interest, would be likely to realise a considerable sum by the purchase of silver at its present reduced price of 4s. 11d. an ounce. But as this purchase would serve to raise silver to the Mint price of 5s. 2d. and comparatively to advance the price of gold, the consequence of which would be to drive gold out of the country, this was, among other reasons, an argument with him for resisting his hon. friend’s doctrine.

(V: 77‒8)

Two years later, in his letter to Grenfell of 19 January 1823, Ricardo mentioned 5s. 6d. – instead of 5s. 2d. – as the prospective market price of silver resulting from the introduction of a double standard. This new figure strengthened his argument against the proposal, since the corresponding fall in the value of the pound would be 10 per cent instead of 5 per cent. How can this change be explained? The answer was in the letter itself:

It is true that no one would carry silver to be coined when its price rose to 5/2, and therefore if the mint were the only channel by which additions could be made to the circulation the price of silver would probably seldom be above 5/2, (unless there were to be a great fall in the relative value of gold), but as these additions can be made by the Bank of England’s increasing the paper circulation, it is quite possible that if the new project be adopted the value of new money may fall in the proportion of 5/6 to 4/11½, or 10 pc.t.

(in Deleplace, Depoortère and Rieucau 2013: 4‒5)

Let me present the argument in detail. One should look at this question from the point of view of interest. As long as the market price of an ounce of standard silver bullion was below 5s. 2d. (the mint price), it was in the interest of its owner to bring it to the mint to have it coined, rather than to sell it in the market. But this stopped when a rising market price of silver reached the mint price. In a system of pure metallic circulation (“if the mint were the only channel by which additions could be made to the circulation”), this would put a check on any additional amount of silver coins, and consequently, according to Ricardo’s doctrine linking the value of the currency to its quantity, would prevent any further increase in the market price of silver: “the price of silver would probably seldom be above 5/2”. In this hypothetical case there was however a restriction: “(unless there were to be a great fall in the relative value of gold)”. It was the consequence of the general inconvenience of a double standard: a sharp decline in the relative value of gold in terms of silver would bring it below the ratio of their mint prices; silver would cease being a standard, gold alone playing that role, and, as seen above, the market price of silver could rise above its mint price. But silver being no longer a standard, this rise did not mean a depreciation of the currency: no such depreciation could therefore occur in a hypothetical pure metallic circulation.10

Now, what about the case of a mixed circulation of coins of both metals and of notes convertible in specie (“as these additions can be made by the Bank of England’s increasing the paper circulation”)? There the seignorage came into play: as long as the market price of an ounce of standard silver had not reached 5s. 6d. (the current legal value of the silver coin), the Bank of England could not lose in paying its notes in silver specie, as it was its interest to do so (like any debtor) whenever silver was the “practical standard”. As a consequence, the Bank could expand its issues (and would do it because issuing notes by discounting bills was its way of earning profit) until that expansion depreciated the currency and raised the market price of silver to 5s. 6d. And this would occur “whilst it [silver] is the standard metal” by which the value of the currency was reckoned. At a time when silver was rated 4s. 11½d. in the market,11 this rise in price up to 5s. 6d. implied a fall in the value of the currency by 10 per cent: “it is quite possible that if the new project be adopted the value of new money may fall in the proportion of 5/6 to 4/11½, or 10 pc.t”.

Could the market price of silver rise higher than 5s. 6d.? Nothing could prevent the Bank from increasing further its issues. But it would be at its own expense: above that level, it was the interest of any arbitrager to cash notes for silver coins at the Bank at 5s. 6d., to melt them down and to sell the bullion back to the Bank (obliged to buy it in order to replenish its cash reserves) at a higher market price. These losses would soon lead the Bank to reduce its issues, and that prevented the market price from rising above 5s. 6d.:

Till it rises above 5/6, it will not be advantageous to melt the coin, and we all know that it is the melting pot only which keeps all currency in a wholesome state.

(ibid: 4)

The argument contained in the letter of 19 January 1823 was complex (so complex that his correspondent Grenfell did not catch it). In his 1821 speech against Baring’s double-standard proposal, Ricardo had explained the rise in price up to 5s. 2d. by the arbitrage behaviour of the Bank of England: its purchases of silver for profit pushed the market price of that metal up to the mint price. Now in the letter Ricardo explained the rise in price up to 5s. 6d. by the issuing behaviour of the Bank of England: its increased note issue would push the market price of silver as standard up to the current legal price of silver in coin.

Such a pernicious influence of the Bank on the value of the currency, in relation to the existence of a seignorage on the silver coin, had already been mentioned by Ricardo when he had been examined on 19 March 1819 by the committee on the resumption of cash payments. The double standard was not then the question but the seignorage itself, and I mentioned earlier that Ricardo was favourable to it. He nevertheless observed that “a coin with a seignorage has also its inconveniences” (V: 402): it gave the opportunity to the Bank of England of changing the value of the currency,12 a recurrent complaint by him.13 In the letter to Grenfell Ricardo was more specific: the combination of a bad monetary system (the double-standard one), of a good provision (the seignorage on the silver coin), and of the power given to the Bank to increase at will the circulation, might lead to a fall in the value of the currency.

As seen above, Ricardo had frequently mentioned the variability in the value of money due to the double standard as a consequence of a change in the relative value of gold to silver in the market, not of the issuing behaviour of the Bank of England. He did publicly mention this behaviour as a source of instability in his defence of the seignorage on the silver coin, not his critique of the double standard per se. He also mentioned publicly that the double standard would lead to a rise in the market price of silver in relation to an arbitrage behaviour of the Bank of England, not its issuing one. Here, in an argument on the variability of the value of money, Ricardo linked the double standard, the seignorage on the silver coin, and the issuing behaviour of the Bank of England.

In 1823 Ricardo’s critique of the double standard in relation with the behaviour of the Bank of England had also political implications, as testified by the end of the letter to Grenfell:

The projected change [in favour of the double standard] is neither more nor less as Lord Grenville has justly stated it, but to do indirectly what Parliament, tho so much urged, has refused to do directly.

(in Deleplace, Depoortère and Rieucau 2013: 5)

What had Parliament “refused to do”? By imposing the return to the pre-1797 price of £3. 17s. 10½d. for an ounce of standard gold, Parliament had refused in 1819 to devaluate the sterling. If Ricardo’s forecast was right, the “projected change” would be nothing else but a disguised way of having the currency fall in value. For him, such a change was not the right answer to the problems of the time: as witnessed by his interventions in Parliament in 1822‒1823, he argued that the distress of the country had its origin neither in the existence of a gold standard nor in the level of the legal price of gold. As a consequence he could not accept an alleged remedy which would have been the reintroduction of a double standard and the falling value of the currency.

Ricardo’s discussion of the double standard is only one of the many examples of his recurrent critique of the Bank’s pernicious influence on the value of money. From the Bullion Essays in 1809‒1811 to the Plan for a National Bank in 1823, he regularly complained about “the facility with which the state has armed the Bank with so formidable a prerogative” (Proposals, IV: 69; Principles, I: 360). In the above-quoted letter to Horner of 5 February 1810 the third and main cause of depreciation of money was “A superabundance of paper circulation.” At that time Ricardo was concerned with the excess of inconvertible Bank of England notes. This did not mean that depreciation was impossible when notes were convertible; it was, however, constrained between narrow limits, while depreciation under inconvertibility had no limit. The regulation of the quantity of convertible notes by the standard is the object of the next chapter.

Appendix 6: A letter on the double standard of money

This letter was discovered in 2010 by Christophe Depoortère and myself amongst Lord Grenville’s papers deposited at the British Library. It was published for the first time in 2013 (for its description, historical context and analytical content, see Deleplace, Depoortère and Rieucau 2013). It had been written by Ricardo on 19 January 1823 to his friend and Member of Parliament Pascoe Grenfell (1761‒1838), at a time when there were rumours of restoring the double standard (gold and silver), legally abandoned since 1816. These rumours were mentioned by Ricardo in a subsequent letter to Hutches Trower of 30 January 1823:

There has been a talk, I believe nothing more, amongst ministers about restoring the two standards, but I am assured all thoughts of it are relinquished.

(IX: 270)