One of the directors of the expedition, P.L.O. Guy, identified these buildings as stables dated to the time of Solomon. His interpretation was based on the biblical description of Solomonic building techniques in Jerusalem (1 Kings 7:12), on the specific reference to the building activity of Solomon at Megiddo in 1 Kings 9:15, and on the mention of Solomonic cities for chariots and horsemen in 1 Kings 9:19. Guy put it this way: “If we ask ourselves who, at Megiddo, shortly after the defeat of the Philistines by King David, built with the help of skilled foreign masons a city with many stables? I believe that we shall find our answer in the Bible . . . if one reads the history of Solomon, whether in Kings or in Chronicles, one is struck by the frequency with which chariots and horses crop up.”

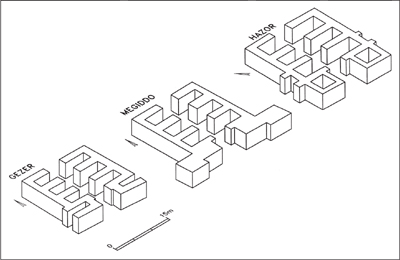

The apparent evidence of the grandeur of the Solomonic empire was significantly enhanced in the 1950s, with the excavations of Yigael Yadin at Hazor. Yadin and his team uncovered a large city gate dated to the Iron Age. It had a peculiar plan: there was a tower and three chambers on each side of the gateway—thus giving rise to the term “six-chambered” gate (Figure 18). Yadin was stunned. A similar gate—in both layout and size—was uncovered twenty years earlier by the Oriental Institute team at Megiddo! Perhaps this and not the stables was the telltale sign of Solomonic presence throughout the land.

So Yadin went to dig Gezer, the third city mentioned in 1 Kings 9:15 as being rebuilt by Solomon—not in the field but in the library. Gezer had been excavated at the beginning of the century by the British archaeologist R.A.S. Macalister. As Yadin paged through Macalister’s reports he was astounded. In a plan of a building that Macalister had identified as a “Maccabean castle” dated to the second century BCE, Yadin could easily identify the outline of one side of exactly the same type of gate structure that had been found at Megiddo and Hazor. Yadin did not hesitate any longer. He argued that a royal architect from Jerusalem drew a master plan for the Solomonic city gates and that this master plan was then dispatched to the provinces.

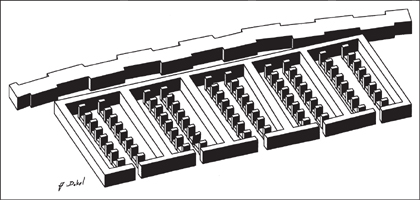

Figure 17: A set of pillared buildings at Megiddo, identified as stables.

Yadin summed it up this way: “There is no example in the history of archaeology where a passage helped so much in identifying and dating structures in several of the most important tells in the Holy Land as has I Kings 9:15 . . . Our decision to attribute that layer [at Hazor] to Solomon was based primarily on the 1 Kings passage, the stratigraphy, and the pottery. But when in addition we found in that stratum a six-chambered, two-towered gate connected to a casemate wall identical in plan and measurement with the gate at Megiddo, we felt sure we had successfully identified Solomon’s city.”

Yadin’s Solomonic discoveries were not over. In the early 1960s, he went to Megiddo with a small team of students to clarify the uniformity of the Solomonic gates, which at Gezer and Hazor were connected to a hollow casemate fortification but only at Megiddo linked to a solid wall. Yadin was sure that the Megiddo excavators had mistakenly attributed a solid wall to the gate, and that they missed an underlying casemate wall. Since the gate had been fully exposed by the University of Chicago team, Yadin chose to excavate east of the gate, where the American team had located an apparent set of stables that they attributed to Solomon.

Figure 18: Six-chambered gates at Megiddo, Hazor, and Gezer.

What he found revolutionized biblical archaeology for a generation. Under the stables Yadin found the remains of a beautiful palace measuring about six thousand square feet and constructed of large ashlar blocks (Figure 24). It was built on the northern edge of the mound, and was connected to a row of rooms that Yadin interpreted as the missing casemate wall that was attached to the six-chamber gate. A somewhat similar palace, also built of beautiful dressed blocks, had been uncovered by the Oriental Institute team on the southern side of the mound, and it also lay under the city of the stables. The architectural style of both buildings was closely parallel to a common and distinctive type of north Syrian palace of the Iron Age, known as the bit hilani, consisting of a monumental entrance and rows of small chambers surrounding an official reception room. This style would therefore have been appropriate for a resident official at Megiddo, perhaps the regional governor Baana, the son of Ahilud (1 Kings 4:12). Yadin’s student David Ussishkin soon clinched the connection of these buildings to Solomon by demonstrating that the biblical description of the palace that Solomon built in Jerusalem perfectly fits the Megiddo palaces.

The conclusion seemed unavoidable. The two palaces and the gate represented Solomonic Megiddo, while the stables actually belonged to a later city, built by King Ahab of the northern kingdom of Israel in the early ninth century BCE. This latter conclusion was an important cornerstone in Yadin’s theory, as a ninth century Assyrian inscription described the great chariot force of King Ahab of Israel.

For Yadin and many others, archaeology seemed to fit the Bible more closely than ever. The Bible described the territorial expansion of King David; indeed, late Canaanite and Philistine towns all over the country were destroyed by a terrible fire. The Bible describes the building activities of Solomon at Hazor, Megiddo, and Gezer; surely the similar gates revealed that the three cities were built together, on a unified plan. The Bible says that Solomon was an ally of Hiram, king of Tyre, and that he was a great builder; indeed, the magnificent Megiddo palaces show northern influence in their architecture, and they were the most beautiful edifices discovered in the Iron Age strata in Israel.

For some years, Solomon’s gates symbolized archaeology’s most impressive support for the Bible. Yet basic questions of historical logic eventually undermined their significance. Nowhere else in the region—from eastern Turkey in the north through western Syria to Transjordan in the south—was there any sign of similarly developed royal institutions or monumental building in the tenth century BCE. As we have seen, David and Solomon’s homeland of Judah was conspicuously undeveloped—and there is no evidence whatever of the wealth of a great empire flowing back to it. And there is an even more troubling chronological problem: the bit hilani palaces of Iron Age Syria—which were supposed to be the prototypes for the Solomonic palaces at Megiddo—appear for the first time in Syria in the early ninth century BCE, at least half a century after the time of Solomon. How would it have been possible for Solomon’s architects to adopt an architectural style that did not yet exist? Finally, there is the question of the contrast between Megiddo and Jerusalem: is it possible that a king who constructed fabulous ashlar palaces in a provincial city ruled from a small, remote, and underdeveloped village? As it turned out, we now know that the archaeological evidence for the vast extent of Davidic conquests and the grandeur of the Solomonic kingdom came as the result of badly mistaken dates.

Identification of the remains from the period of David and Solomon—and indeed from the reigns of the kings that followed for the next century—was based on two classes of evidence. The end of distinctive Philistine pottery (dated c. 1000 BCE) was closely linked to David’s conquests. And the construction of the monumental gates and palaces at Megiddo, Hazor, and Gezer were connected with the reign of Solomon. In the last few years, both supports have begun to crumble (see Appendix D for more details).

First, we can no longer be sure that the characteristic Philistine pottery styles did not continue well into the tenth century—long after the death of David—and would therefore be useless for dating (much less verifying) his supposed conquests. Second, renewed analysis of the architectural styles and pottery forms in the famous Solomonic levels at Megiddo, Gezer, and Hazor indicates that they actually date to the early ninth century BCE, decades after the death of Solomon!

A third class of evidence, the more precise laboratory techniques of carbon 14 dating, now seems to clinch the case. Until recently it was impossible to use radiocarbon dating for such relatively modern periods as the Iron Age because of its wide margin of probability, often extending over a century or more. But refinements of carbon 14 dating techniques have greatly reduced the margin of uncertainty. A number of samples from the major sites involved in the tenth century debate have been tested and seem to support the new chronology.

The site of Megiddo, in particular, has produced some stunning contradictions to the accepted interpretations. Fifteen wood samples were taken from large roof beams that had collapsed in the terrible fire and destruction attributed to David. Since some of the beams could have been used in earlier buildings, only the latest dates in the series can safely indicate when the structures were built. Indeed most of the samples fall well into the tenth century—long after the time of David. The palaces ascribed to Solomon, built two layers above this destruction, would have been much later.

These dates have been confirmed by tests of parallel strata at such prominent sites as Tel Dor on the Mediterranean coast and Tel Hadar on the shore of the Sea of Galilee. Sporadic readings from several other, less well known sites, such as Ein Hagit near Megiddo and Tel Kinneret on the northern coast of the Sea of Galilee, also support this dating. Finally, a series of samples from the destruction of a stratum at Tel Rehov near Bethshean, which is contemporary with Megiddo’s supposed Solomonic city, gave mid-ninth century dates—long after its reported destruction by Pharaoh Shishak in 926 BCE.

Essentially, archaeology misdated both “Davidic” and “Solomonic” remains by a full century. The finds dated to the time just before David in the late eleventh century belonged in the mid-tenth century and those dated to the time of Solomon belonged in the early ninth century BCE. The new dates place the appearance of monumental structures, fortifications, and other signs of full statehood precisely at the time of their first appearance in the rest of the Levant. They rectify the disparity in dates between the bit hilani palace structures in Megiddo and their parallels in Syria. And they allow us finally to understand why Jerusalem and Judah are so poor in finds in the tenth century. The reason is that Judah was still a remote and undeveloped region at that time.

There is hardly a reason to doubt the historicity of David and Solomon. Yet there are plenty of reasons to question the extent and splendor of their realm. If there was no big empire, if there were no monuments, if there was no magnificent capital, what was the nature of David’s realm?

The material culture of the highlands in the time of David remained simple. The land was overwhelmingly rural—with no trace of written documents, inscriptions, or even signs of the kind of widespread literacy that would be necessary for the functioning of a proper monarchy. From a demographic point of view, the area of the Israelite settlement was hardly homogeneous. It is hard to see any evidence of a unified culture or centrally administered state. The area from Jerusalem to the north was quite densely settled, while the area from Jerusalem to the south—the hub of the future kingdom of Judah—was still very sparsely settled. Jerusalem itself was, at best, no more than a typical highland village. We can say no more than that.

The population estimates for the later phases of the Israelite settlement period apply also to the tenth century BCE. They give an idea of the scale of historical possibilities. Out of a total of approximately forty-five thousand people living in the hill country, a full 90 percent would have inhabited the villages of the north. That would have left about five thousand people scattered among Jerusalem, Hebron, and about twenty small villages in Judah, with additional groups probably continuing as pastoralists. Such a small and isolated society like this would have been likely to cherish the memory of an extraordinary leader like David as his descendants continued to rule in Jerusalem over the next four hundred years. At first, in the tenth century, their rule extended over no empire, no palatial cities, no spectacular capital. Archeologically we can say no more about David and Solomon except that they existed—and that their legend endured.

Yet the fascination of the Deuteronomistic historian of the seventh century BCE with the memories of David and Solomon—and indeed the Judahites’ apparent continuing veneration of these characters—may be the best if not the only evidence for the existence of some sort of an early Israelite unified state. The fact that the Deuteronomist employs the united monarchy as a powerful tool of political propaganda suggests that in his time the episode of David and Solomon as rulers over a relatively large territory in the central highlands was still vivid and widely believed.

Of course, by the seventh century BCE conditions in Judah had changed almost beyond reckoning. Jerusalem was now a relatively large city, dominated by a Temple to the God of Israel that served as the single national shrine. The institutions of monarchy, a professional army, and administration had reached a level of sophistication that met and even exceeded the complexity of the royal institutions of the neighboring states. And once again we can see the landscapes and costumes of seventh century Judah as the setting for an unforgettable biblical tale, this time of a mythical golden age. The lavish visit of Solomon’s trading partner the queen of Sheba to Jerusalem (1 Kings 10:1–10) and the trade in rare commodities with distant markets such as the land of Ophir in the south (1 Kings 9:28; 10:11) no doubt reflect the participation of seventh century Judah in the lucrative Arabian trade. The same holds true for the description of the building of Tamar in the wilderness (1 Kings 9:18) and the trade expeditions to faraway lands setting out from Ezion-geber in the Gulf of Aqaba (1 Kings 9:26)—two sites that have been securely identified and that were not inhabited before late monarchic times. And David’s royal guard of Cherethites and Pelethites (2 Samuel 8:18), long assumed by scholars to have been Aegean in origin, should be understood on the background of the service of Greek mercenaries, the most advanced fighting force of the day, in the Egyptian and possibly Judahite armies of the seventh century.

In late monarchic times, an elaborate theology had been developed in Judah and Jerusalem to validate the connection between the heir of David and the destiny of the entire people of Israel. According to the Deuteronomistic History, the pious David was the first to stop the cycle of idolatry (by the people of Israel) and divine retribution (by YHWH). Thanks to his devotion, faithfulness, and righteousness, YHWH helped him to complete the unfinished job of Joshua—namely to conquer the rest of the promised land and establish a glorious empire over all the vast territories that had been promised to Abraham. These were theological hopes, not accurate historical portraits. They were a central element in a powerful seventh century vision of national renaissance that sought to bring scattered, war-weary people together, to prove to them that they had experienced a stirring history under the direct intervention of God. The glorious epic of the united monarchy was—like the stories of the patriarchs and the sagas of the Exodus and conquest—a brilliant composition that wove together ancient heroic tales and legends into a coherent and persuasive prophecy for the people of Israel in the seventh century BCE.

To the people of Judah at the time when the biblical epic was first crafted, a new David had come to the throne, intent on restoring the glory of his distant ancestors. This was Josiah, described as the most devoted of all Judahite kings. And Josiah was able to roll history back from his own days to the time of the legendary united monarchy. By cleansing Judah of the abomination of idolatry—first introduced into Jerusalem by Solomon with his harem of foreign wives (1 Kings 11:1–8)—Josiah could nullify the transgressions that led to the breakdown of the Davidic “empire.” What the Deuteronomistic historian wanted to say is simple and powerful: there is still a way to regain the glory of the past.

So Josiah embarked on establishing a united monarchy that would link Judah with the territories of the former northern kingdom through the royal institutions, military forces, and single-minded devotion to Jerusalem that are so central to the biblical narrative of David. As the monarch sitting on the throne of David in Jerusalem, Josiah was the only legitimate heir to the Davidic empire, that is, to the Davidic territories. He was about to “regain” the territories of the now destroyed northern kingdom, the kingdom that was born from the sins of Solomon. And the words of 1 Kings 4:25, that “Judah and Israel dwelt in safety from Dan even to Beer-sheba,” summarize those hopes of territorial expansion and quest for peaceful, prosperous times, similar to the mythical past, when a king ruled from Jerusalem over the territories of Judah and Israel combined.

As we have seen, the historical reality of the kingdom of David and Solomon was quite different from the tale. It was part of a great demographic transformation that would lead to the emergence of the kingdoms of Judah and Israel—in a dramatically different historical sequence than the one the Bible describes. So far we have examined the biblical version of Israel’s formative history written in the seventh century BCE, and we have provided glimpses at the archaeological reality that underlies it. Now it is time to tell a new story. In the chapters that follow, we will present the main outlines of the rise, fall, and rebirth of a very different Israel.