Easter Parade on Fifth Avenue, ca. 1940.

PHOTOGRAPH BY RUTH SONDAK

As early as the fourth century A.D., St. Gregory of Nyssa noted that Easter Sunday inspired people to come out in their best clothes. Since then, there have been annual religious parades, mostly in Europe, to convey the rebirth that comes with spring, and in the 1870s, those walks were codified into a spring fashion ritual in New York. On April 14, 1879, the Times was able to report that good weather the previous day had “tempted those who had provided themselves with Spring attire to indulge in the luxury of taking part in the annual display,” adding that “Spring bonnets were worn by every lady promenader.” It became very much a fashion-driven event, so much so that milliners and dressmakers would attend to take notes and make sketches in order to knock off the styles. A Harlem parade soon followed, as did, eventually, Irving Berlin’s song “Easter Parade” (1933) and the musical of the same name (1948) starring Judy Garland and Fred Astaire. Today, the parade—held on Fifth Avenue in the 50s—has lost its link to contemporary fashion but remains a place for participants to show off their most outrageously ornate headwear.

Easter Parade on Fifth Avenue, ca. 1940.

PHOTOGRAPH BY RUTH SONDAK

No egg! No cream! But perhaps you knew that. The quintessential New York soda-fountain drink has many paternity claims, but all of them trace back to the early-twentieth-century Jewish community on the Lower East Side. The firmest origin story comes from Louis Auster, who owned a couple of local candy stores—the original was at Stanton and Lewis Streets—and said he started mixing up seltzer, syrup, and milk around 1900. By the time of his death in 1955, Auster was said to be selling 3,000 egg creams a day.

The Harvard sociologist Daniel Bell, a Lower East Side native, disputed this entire narrative in New York in 1971. He insisted that his own uncle Hymie, proprietor of a candy store on Second Avenue, had invented the drink around 1920, and that in his early version it was indeed enriched with—wait for it—eggs and cream. Eventually a rival candy-store owner, also named Hymie, had adulterated the recipe and undercut the original Hymie’s prices, driving him out of the egg-cream game. Maybe it’s true.

Although you can order vanilla or (yuck) strawberry variants of the egg cream, the canonical version is chocolate-flavored and made with Fox’s U-Bet syrup, which has been produced in Brooklyn since 1900. You put three ounces of milk in a tall glass, fill nearly to the top with cold seltzer, and stir with a long spoon. (It will fizz up.) Add a few squirts of U-Bet, and stir again.

The seltzer is correctly mixed in before the syrup rather than after, so the foamy head is white and bubbly rather than brown and sticky. (A lot of people get this wrong.) Refinements include extra-fizzy seltzer shot from a glass syphon bottle (see also SELTZER) and the seasonal kosher-for-Passover version of U-Bet made with cane sugar instead of corn syrup. True maniacs concoct their own chocolate syrup. Most important is that you drink it right away. An egg cream is delightful when fresh, flat and unpleasant fifteen minutes later.

Until 1967, it was believed that eggs Benedict—that exceedingly rich breakfast dish consisting of a poached egg, ham, hollandaise sauce, and an English muffin—was invented at either Delmonico’s or the Waldorf Hotel. In the latter case, a man by the name of Lemuel Benedict was credited with first ordering the dish in hopes of curing a killer hangover. But then came 1967, when the New York Times received a letter from one Edward P. Montgomery, who bemoaned the current “concoction of an overpoached egg on a few shreds of ham” being served at most American restaurants. He claimed his mother had gotten the recipe used by the dish’s true inventor, their family friend Commodore Elias Cornelius Benedict, a Wall Street banker. (A “real trick,” Montgomery says, is to assemble all the components “when they are à point.”) Whether Lemuel or Elias Cornelius first brought us this brunch staple may forever remain a mystery, but at the very least, this city drove one (or both) of these men to take breakfast to an entirely new level.

1 How to Make the Perfect Hollandaise

From Chef Jaime Young, Sunday in Brooklyn

“In my opinion, the most important step is your setup. It should be mixed over a double boiler. It’s important to keep the water at a light simmer. If the water boils, it could scramble the yolks, which you do not want. Make sure to whisk the yolks constantly and cook them to about 160 degrees Fahrenheit. The butter should be clarified and warm. Before emulsifying, it’s important to add some liquid to help suspend the fat and create the emulsion. I use a bit of hot sauce and lemon juice. When you begin to emulsify the butter into the egg-lemon mixture, steadily pour the butter at a slow pace, adding it in stages along with a few drops of water to help stabilize the emulsion. Once you’ve made the sauce, keep it in a warm place. If it gets too cold, it may separate.”

Thomas Edison’s great invention that made modern life possible was not the incandescent lightbulb itself. Rather, it was the business and infrastructure that fed those lights: the network of power plants, overhead wires, and construction and maintenance and billing people that all supported the use of electricity. The first functional bulb came out of Edison’s lab in 1879; the next year, the Edison Electric Illuminating Company was incorporated and given a franchise to light up New York. (Two other companies, Brush Electric Illuminating and United States Illuminating, made separate deals with the city to handle streetlights.) On September 4, 1882, direct current flowed from the dynamos in Edison’s new plant, the world’s first, at 257 Pearl Street. It served 82 customers with about 400 lights. Many other small companies quickly followed. In the late nineteenth century, most of these were bought and, after a dizzying series of mergers and deals, formed a couple of large syndicates. Eventually, the Consolidated Gas Company—which had been a major source of New Yorkers’ illumination and energy when gaslight ruled—entered the electricity business by gaining control of those syndicates, and in 1936 it changed its name to Consolidated Edison.

Between 2001 and 2003, electroclash, a short-lived but influential music movement that combined elements of techno and punk into retro, danceable beats, dominated New York club life. Centered in Williamsburg, where the artistic and bohemian scenes had moved as Manhattan became too expensive and noise averse, the scene had a vaudevillian, performance-art quality that put a high value on inventive, charismatic personas, humor, theatrical showmanship, and DIY style. (The 1982 cult film Liquid Sky was a common underlying reference.) It was perhaps the first electronic-music movement that was welcoming to women, and the scene was marked by an openly gay sensibility. Although it has European roots, electroclash was incubated in and indelibly identified with New York.

Peaches at Music Hall of Williamsburg, 2009.

PHOTOGRAPH BY HOLGER TALINSKI

In 1997, a Dutch producer named I-F released “Space Invaders Are Smoking Grass,” a track that hyper-fetishized ’80s New Wave music and made those retro beats feel new. It was followed the next year by the French group Miss Kittin & the Hacker’s two anthems, “1982” and “Frank Sinatra.” And by 2000, two prominent acts had emerged in New York that drew on these influences. One was Peaches, whose album The Teaches of Peaches was full of a filthy-mouthed, unapologetic sexualized feminism (its most famous track is titled “Fuck the Pain Away”). The other was a fluid group known as Fischerspooner, created by Casey Spooner and Warren Fischer, which at times could include as many as twenty members performing at Warholian rock-opera events mixing comedy, shock, meta-critique, sex appeal, and showbiz razzle-dazzle. They played galleries instead of music venues and quickly became darlings of the contemporary-art world, supported by gallerists Gavin Brown and Jeffrey Deitch and then–MoMA PS1 curator Klaus Biesenbach.

The producer and DJ Larry Tee, already well known for co-writing RuPaul’s unlikely 1993 hit “Supermodel (You Better Work),” popularized the movement’s portmanteau name. After seeing Peaches and Fischerspooner, he later said, he thought of electro, an ’80s term. But this new electro embodied many different elements, from the funk of the Detroit Grand Pubahs, to the politics of Chicks on Speed, to the sexuality of Peaches. “To me it felt like a clash of ideas and sounds.” In 2001, he put together the first electroclash music festival, bringing together all the new acts in one place, then started a record label, Mogul Electro. His own band, W.I.T. (short for “Whatever It Takes”), was fronted by a bombshell downtown “It” girl, Melissa Burns. Other prominent acts included A.R.E. Weapons, Felix Da Housecat, Avenue D, and ADULT.

Within a year, the scene had a clubhouse, LUXX, a dive bar on Grand Street in Williamsburg that could fit 200 people and was frequented by international celebrities and fashion stars. Among other groups that broke out there, Scissor Sisters, a band led by Jake Shears that went on to become one of the top-grossing electroclash acts, earned a Grammy nomination for its disco cover of Pink Floyd’s “Comfortably Numb.” The band’s self-titled debut album was the best-selling album of 2004 in the U.K.

By then, tastes back in Brooklyn had begun to shift toward emerging neo-punk bands like the Strokes. Still, Peaches and Felix da Housecat keep performing, Jake Shears starred in Kinky Boots on Broadway in 2018, and Casey Spooner has become an Instagram star. Much of the style, sound, and sassy posturing of the electroclash scene lingers in the mainstream, adopted by the likes of Lady Gaga.

2 The Essential Electroclash Playlist

Chosen by Fischerspooner’s Casey Spooner and Warren Fischer

Contemporary life in New York City depends on a few crucial bits of infrastructure, like cheap electrical power, the rail system, the Catskills aqueducts, and—less flashy but absolutely necessary—the elevator. Without it, you can’t raise buildings over six or seven stories, and Manhattan as we know it would not exist.

Setting aside its progenitors like rope-and-pulley haylofts, the first elevator shaft in New York can be dated to 1853, and, oddly enough, it substantially predates the invention of the device itself. When the iron-and-railroads magnate Peter Cooper endowed and planned the main academic building of Cooper Union, he foresaw that a mechanized lift lay in the near future. Even though no such machinery was available, his architect left a round shaft open between the floors of his new structure. Some years after the building was completed in 1859, his son, Edward Cooper, put together a steam-engine lift and added an elevator cab.

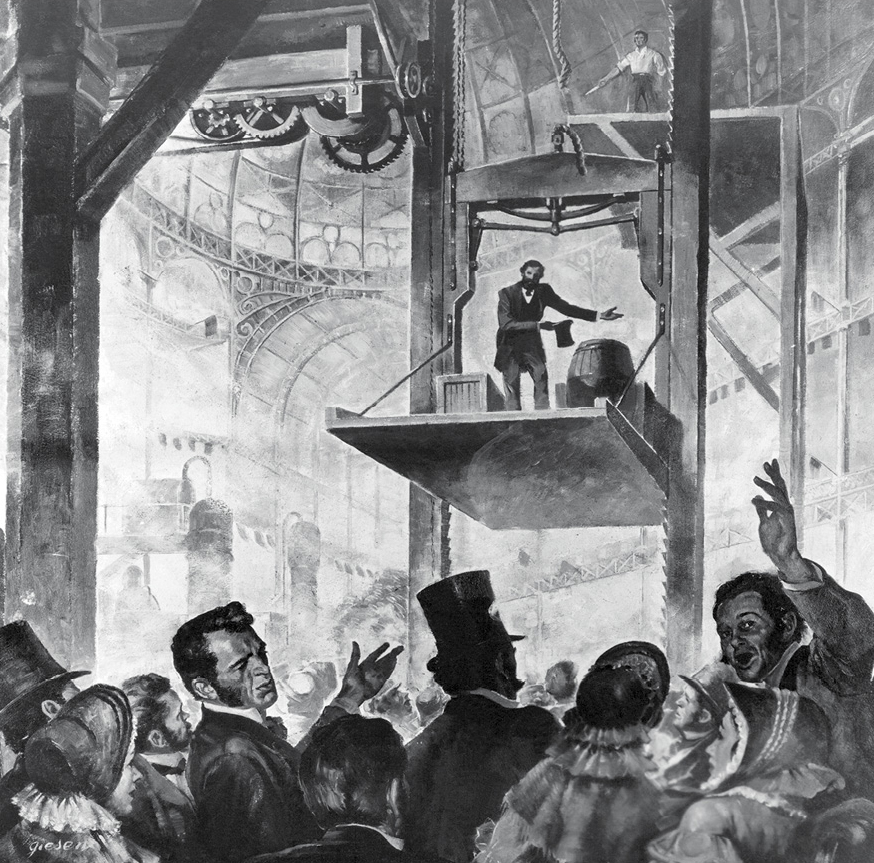

By that time, the breakthrough had been made. In 1852, Elisha Graves Otis, an inventor in Yonkers, had figured out a safety catch that would prevent an elevator cab from falling should its cables snap. In 1854, at New York’s Crystal Palace exhibition, he showed it off dramatically by standing on a demonstrator hoist and ordering the rope supporting it to be cut. After building several installations meant for freight, Otis added a passenger elevator to the E. V. Haughwout department store at the corner of Broadway and Broome Street in 1857, and the race to make ever taller buildings began to escalate.

Elisha Graves Otis demonstrates his first elevator at the Crystal Palace, 1853.

Those safety catches are nearly fail-safe, but on one terrifying occasion, they did indeed fail. On July 28, 1945, a B-25 bomber crashed into the seventy-ninth floor of the Empire State Building, setting it afire and killing fourteen people. The impact severed the cables of one elevator, which free-fell nearly eighty floors into the subbasement. Two women onboard were badly injured but survived: The buildup of air pressure beneath the elevator cab slowed its fall just enough to save them, and the quarter-mile or so of thick steel cable beneath it bunched up, unexpectedly creating a sort of springy cushion. The operator, Betty Lou Oliver, returned to the building and rode the elevator five months later.

The town of Saugus, Massachusetts, can claim the idea of the escalator, owing to a moving-stairway design by a resident named Nathan Ames in 1852, but he never actually built one. New York City gets the nod because of the work of Jesse W. Reno, whose “inclined elevator” idea was patented in 1892, then built and installed at Coney Island’s Old Iron Pier four years later. Passengers stepped onto T-shaped cleats, in a kind of standing version of a chairlift arrangement, and rode all of seven feet.

Subsequent refinements by Reno and inventors working with the Otis Elevator Company added stair treads and moving handrails. In fact, an Otis employee named Charles Seeberger coined the word Escalator (capitalized and trademarked at first). The oldest escalators still running in New York, and among the world’s last with wooden treads, are rumbling along on the upper floors of Macy’s 34th Street store, where they were installed between 1920 and 1930. Some of the longest in town are in the subways, including one that carries passengers 172 feet down to (or up from) the 34th Street–Hudson Yards subway station, opened in 2015.

This is possibly a unique selection, in that the inventor of the job was its definitive (and perhaps only) practitioner. Harry Houdini, born Erik Weisz in Hungary, moved to Milwaukee at the age of eight, came to New York young, and established a career on the vaudeville circuit, performing in partner acts first with his brother Theo and later with his wife, Bess. In the early 1900s, he was likely the biggest star in the world, a celebrity before radio, eclipsed only by rising names of the cinema like Charlie Chaplin and Buster Keaton. The word tricks was barely enough to describe what he did; whereas magicians performed card and coin and cigarette magic (which he could also do quite well), Houdini went for big-and-bigger-scale acts that at least seemed, and in some cases were, life-threatening. Getting out of handcuffs while underwater, sometimes suspended by his feet; allowing himself to be sealed in local bank vaults or jail cells while on tour in Middle America; twisting himself out of tight straitjackets; even being sealed in a coffin and lowered into a pool—it all contributed to a unique act that was athletically demanding and purely American in its death-defying nature. He would on occasion stay behind a curtain for ten minutes, twenty minutes, half an hour, ratcheting up the tension in the theater as the audience began to assume that he had been injured or worse. Audience members were known to cry out for his release. Then he would burst forth, to cheers and relief.

Houdini got rich doing it, making more than almost any other entertainer of his time, and ran his business out of a brownstone at 278 West 113th Street that was packed with paperwork, touring equipment, and books about all kinds of tricks, flimflams, and magical arts. His expertise turned him into a great debunker, and he relished unmasking scam-artist psychics and spiritualists. He toured up to the end of his life: While on the road in October 1926, his appendix burst (legend has it that a fan had unexpectedly socked him in the stomach, a trick he normally prepared for by tensing his abs), and he died on Halloween. His body was shipped back to New York in the glass-topped coffin he’d used for one of his escapes. He’s interred at Machpelah Cemetery in Glendale, Queens. Since then, Houdini’s admirers have conducted annual séances on Halloween, hoping to hear from him. So far, they haven’t.

His magnetism reportedly lay in live performance. There are films of Houdini at work, but they just don’t quite convey it. Periodically, one of today’s magicians—David Copperfield, say—reenacts one of the great Houdini escapes, say, from the Water Torture Cell, on television, but with the mediation of the TV camera and the unwillingness of today’s audience to wait half an hour for the tension to build, a lot of its power is gone. The original escape artist remains alive as a personal brand, his name instantly recognizable, instantly identified with escape.

The man who used a spoonful of chocolate to make the laxative go down was named Kiss. A year or so after he graduated from Columbia University’s pharmacy program in 1904, Max Kiss fell into a shipboard conversation with a doctor who mentioned Bayer’s new drug phenolphthalein, which relieved constipation. He spent the next year working up a formulation; mindful of children who resisted swallowing their repulsive spoonfuls of castor oil, he embedded the phenolphthalein in chocolate and introduced his product in 1906. The company he founded, Ex-Lax, was slyly named, and not solely because the words imply “excellent laxative.” It’s a play on a Latinate phrase Kiss picked up in Hungary that describes political deadlock: ex-lex is a condition under which the constitution is temporarily suspended and parliament is dissolved, during which everything stalls and no legislation can, uh, move.

By the mid-1920s, Kiss had opened a big Ex-Lax factory at 423 Atlantic Avenue in Brooklyn, and he remained chairman of the company until his death in 1967. Today, the brand is owned by the giant pharmaceutical company Novartis, the product no longer contains phenolphthalein (turns out that it’s carcinogenic), and the building, like so many industrial sites, has been converted to condominiums. It’s surely the only luxury apartment building with a wall of laxative memorabilia displayed in the lobby.

The first words of Jane Jacobs’s The Death and Life of Great American Cities, published in 1961 by Random House, are “This book is an attack.” She wasn’t kidding. In paragraphs of sturdy carpenter’s prose, Jacobs sawed up and dismantled virtually every prevailing thought in the world of urban planning. The era’s dominant idea called for “slum clearance,” the demolition of swaths of neighborhoods in favor of modern housing projects; Jacobs argued for keeping as much of the old as possible, intermingling it with the new. Those new towers were typically set back from the sidewalk, surrounded by lawns; Jacobs argued for the vitality of sidewalk frontage. Planners referred to “wasteful streets” and tried to eliminate them, forming superblocks; Jacobs argued for smaller blocks and more streets instead.

Most of all, she said, what made cities work was their untidy mix of functions. Planners of the day preferred to segregate retail from residences and offices, and Jacobs argued that doing so was a colossal mistake, one that was contributing to the rising crime rates in American cities. A street that was all offices would be dead by night, thus putting people at risk of being robbed. A street that housed only office workers would be silent by day, as in the suburbs, and not very interesting. In the ideal urban neighborhood—Jacobs cited the West Village, where she lived, as well as the North End in Boston and a number of others—parents with small children were out and about early, shopkeepers were active by day, office workers came home in the early evening, restaurants and bars stayed open into the night, and all of them, almost inadvertently, kept watch over the block. They were, in her pithy phrase, “eyes on the street”—the neighborhood’s “natural proprietors,” people who had a stake in its preservation and cared about it and who functioned as auxiliary security guards, maintaining order by their mere existence. This kind of social fabric, Jacobs argued, was almost impossible to build from scratch, which was why tearing down blocks of 80-year-old buildings and putting up slabs to replace them often created more despair and crime than before.

Jacobs’s book was indeed received as the attack she said it was, particularly because she and a few other Greenwich Villagers went up against Robert Moses, New York’s all-powerful planning czar, when he proposed a broad elevated highway (see also HIGHWAY, ELEVATED) across lower Manhattan, with a sunken access road cutting directly through Washington Square Park. Moses was aggrieved to have been challenged by, as he put it, “a bunch of mothers”; he grew even more so when they won, stalling his plans and preserving the area that later became known as Soho (see also LOFT LIVING).

A generation later, the Jacobean approach had come to be—and remains—a principal way of thinking about urban design. Yet it is often honored in a piecemeal, poorly understood way. Old low-rise neighborhoods are preserved and rehabbed (see also LANDMARKS LAW), but in the process they become expensive (see also GENTRIFICATION), which in turn means local hardware stores and bookstores and laundromats and other necessary businesses give way to boutiques that are not particularly useful except to visitors. Property developers put up towers that honor the street line, with storefronts along the sidewalk as they should be, but in doing so they give the whole block to one supersize retailer and sweep away the older, smaller frontage that might house a mixed set of businesses. When that happens, there are fewer eyes on the street—at least organically. Nowadays, building owners try to make up the difference with security desks and video cameras.