At the Stork Club, 1949.

PHOTOGRAPH BY STANLEY KUBRICK

Socializing, in the world known as Society, once occurred principally in the homes of wealthy people. (It helped to have your own ballroom.) In the 1920s, though, young Society men and women began to break with this tradition, going out to nightclubs and speakeasies where they could dance and drink and otherwise misbehave (see also NIGHTCLUB). A gossip columnist, Maury Paul of the New York Evening Journal, named this crowd “Café Society,” and soon enough the term was taken up everywhere. (His rival columnist Lucius Beebe referred to their world as “Chromium Mist,” which is perhaps more vivid but also sounds like a paint color.) In 1925, the young socialite Ellin Mackay scandalized her set with an insider’s account of Café Society, titled “Why We Go to Cabarets: A Post-Debutante Explains,” which was picked up by Harold Ross’s brand-new magazine The New Yorker, becoming its first newsstand hit and saving the flat-broke publication from closing.

The term became widespread in the 1930s and lent its name to one of the great Greenwich Village clubs of the era, and more broadly came to describe the scene at places like the Stork Club, El Morocco, and the ‘21’ Club. Although it eventually drifted into disuse, the social whirl it described has yet to end. In the 1950s, Igor Cassini, Paul’s gossip-page successor, coined the term jet set, which still gets an occasional airing even though jet travel is no longer elite.

1 How to Make a Stork Club Cocktail

According to The Stork Club Bar Book (1946), by Lucius Beebe, rediscovered by historian Philip Greene

Dash of lime juice

Juice of half an orange

Dash of triple sec

1 ½ oz. gin

Dash of Angostura bitters

At the Stork Club, 1949.

PHOTOGRAPH BY STANLEY KUBRICK

The capital of the United Kingdom is London. France’s is Paris. Surely the United States of America ought to be run from its most influential city? Indeed it was, briefly, at the beginning. As the Sixth Congress of the Confederation met in 1785 to continue the work of establishing a new country, its members did so in lower Manhattan at the no longer British City Hall on Wall Street. Several subsequent meetings there, held in parallel with the Constitutional Convention in Philadelphia, set down the U.S. form of government, and on April 30, 1789, George Washington took the oath of office on the second-floor balcony of that same building, which had been renovated to suit the legislature and renamed Federal Hall. The first U.S. Congress met there that day and later created the departments now called State, Defense, and Treasury. Debates and sessions continued in the building for a year, while President Washington lived a short walk away, over at Pearl and Cherry Streets (now Pearl and Dover).

But over the course of the Revolutionary War, the northern colonies in particular had accumulated millions of dollars in debt and pressured the new federal government to pay off the banks. The representatives of the southern states did not want to permit this; they also wanted a capital closer to home and disliked New York City’s cosmopolitanism and emphasis on commerce. Thomas Jefferson and James Madison of Virginia and Alexander Hamilton of New York worked out a compromise and persuaded their respective states to agree, and on July 10, 1790, Congress passed the Residence Act, transferring the capital temporarily to Philadelphia and then permanently to a swampy dump on the Potomac, soon to be called Washington.

2 How to Visit the Original Capital of the United States

Federal Hall, at 26 Wall Street in the Financial District, is open to visitors for solo or park-ranger-guided tours during the week. The George Washington Inaugural Gallery contains pieces of the original building, and the Bible on which Washington was sworn into office is occasionally on view.

First produced in large quantities by British foundries in the late eighteenth century, cast iron offered some key advantages over the brick and stone that builders had been using for thousands of years. Although brittle, it was very strong in compression, and because it could be poured into molds, it could be mass-produced to look like carved masonry without the need for skilled stonecutters. A few early buildings and bridges in England and Bermuda predate its use in New York, but far and away its most prominent and widespread employment began in the downtown neighborhood we now call Soho. There, in the late 1840s, a builder named James Bogardus began casting and selling building parts that could be assembled from a catalogue. His structures made excellent factories because the iron façades, being pound-for-pound stronger than brick, allowed for larger windows, which, in turn, permitted larger factory floors in the days before electric lighting. Some Bogardus buildings went a step further and were completely constructed from this new material. His and others’ catalogues supplied the parts for hundreds of structures, mostly in Manhattan, through the beginning of the twentieth century, when steel and concrete took over.

By the 1960s, these century-old buildings were mostly obsolete, as manufacturing moved to even larger factory floors with cheaper labor in the South and West and then overseas. Lower Manhattan’s cast-iron architecture was declared “worthless” in one study ordered by planning czar Robert Moses; his plan for the Lower Manhattan Expressway called for a large swath of Soho’s cast-iron buildings to be demolished. Meanwhile, many of their floors had been colonized by artists, who found their large windows and open spaces as appealing for art-making as they had been for manufacturing. The efforts of community activists, notably Jane Jacobs, led to not only the cancellation of the highway but the preservation of the Soho Cast Iron Historic District, which subsequently became an arts district and has since turned into one of the most expensive retail and residential neighborhoods in the U.S.

Four Bogardus buildings survive in New York City. The story of a lost fifth one, built for the Edgar H. Laing company in 1849, is unique. In the 1960s, the new Landmarks Preservation Commission (see also LANDMARKS LAW) agreed to allow its demolition with the proviso that its cast-iron parts be disassembled and stored toward a later reconstruction. But in 1974, three men were caught removing a large piece of it from a storage yard. It became clear that, over the preceding months, two-thirds of the façade had been taken and sold for scrap. (A few pieces were recovered from a Bronx junkyard, but most had presumably been melted down.) Beverly Moss Spatt, chair of the Landmarks Preservation Commission, announced the news by darting into the press room at City Hall and shouting, “Someone has stolen one of my buildings!”

3 Cast-Iron Gems Worth Stopping to Look At

From the New York Preservation Archive Project’s Anthony W. Robins

TRIBECA

TRIBECA

Cary Building, 105–107 Chambers St. and 89–91 Reade St. (1856–57): A fancy-goods firm ordered a cast-iron façade imitating stone for the Chambers Street front and, since cast iron was prefabricated, an identical façade for the Reade Street side.

SOHO

SOHO

E. V. Haughwout Building, 488–492 Broadway, at Broome St. (1857): J. P. Gaynor modeled his design on the Library of St. Mark in Venice.

LADIES’ MILE

LADIES’ MILE

B. Altman, 615–629 Sixth Ave., at 19th St. (1876–77): The oldest of the big department stores here is covered in detailed, geometric neo-Grec ornament.

WILLIAMSBURG

WILLIAMSBURG

183–195 Broadway, at Driggs Ave., Brooklyn (1882–83): Williamsburg has the city’s only sizable collection of cast-iron façades outside Manhattan. This one has enormous cast-iron calla lilies on the second story.

Soda in the nineteenth century was not typically a bright, fruity beverage. Often flavored with roots, barks, seeds, and various other pungent botanical ingredients, it was treated as a health tonic and sold at drugstore pharmacy counters. A few of those flavors and their manmade analogs are still in use, including kola nut (in, of course, Coca-Cola and Pepsi), sassafras bark (root beer), birch sap (birch beer), gentian root (Moxie), and celery seed, in the form of Dr. Brown’s Cel-Ray soda.

There was, it appears, an actual Dr. Henry E. Brown, a pharmacist who in 1867 invented a syrup of sugar and crushed celery seeds and mixed it with carbonated water to settle stomachs on the Lower East Side and in Williamsburg. Within a couple of years, a celery tonic bearing his name was being produced by the firm of Schoneberger & Noble on Water Street. The Cel-Ray name was trademarked in 1947 (along with a logo showing two crossed celery stalks), and “Jewish Champagne” was its nickname; it sold well in delicatessens, not least because it complements a fatty, meaty meal, like a pastrami sandwich. The word tonic left the label in the 1950s when the FDA began to object to its hint of medical efficacy.

As tastes changed and Jewish delis began to disappear in the 1970s and 1980s, Dr. Brown’s became more of a specialty item sold mostly in New York markets and scattered gourmet shops around the country. In 1982, the brand was sold to Canada Dry, which continues to bottle it. Part of an old Schoneberger & Noble plant in Williamsburg is now occupied by Brooklyn Brewery (see also “BROOKLYN”).

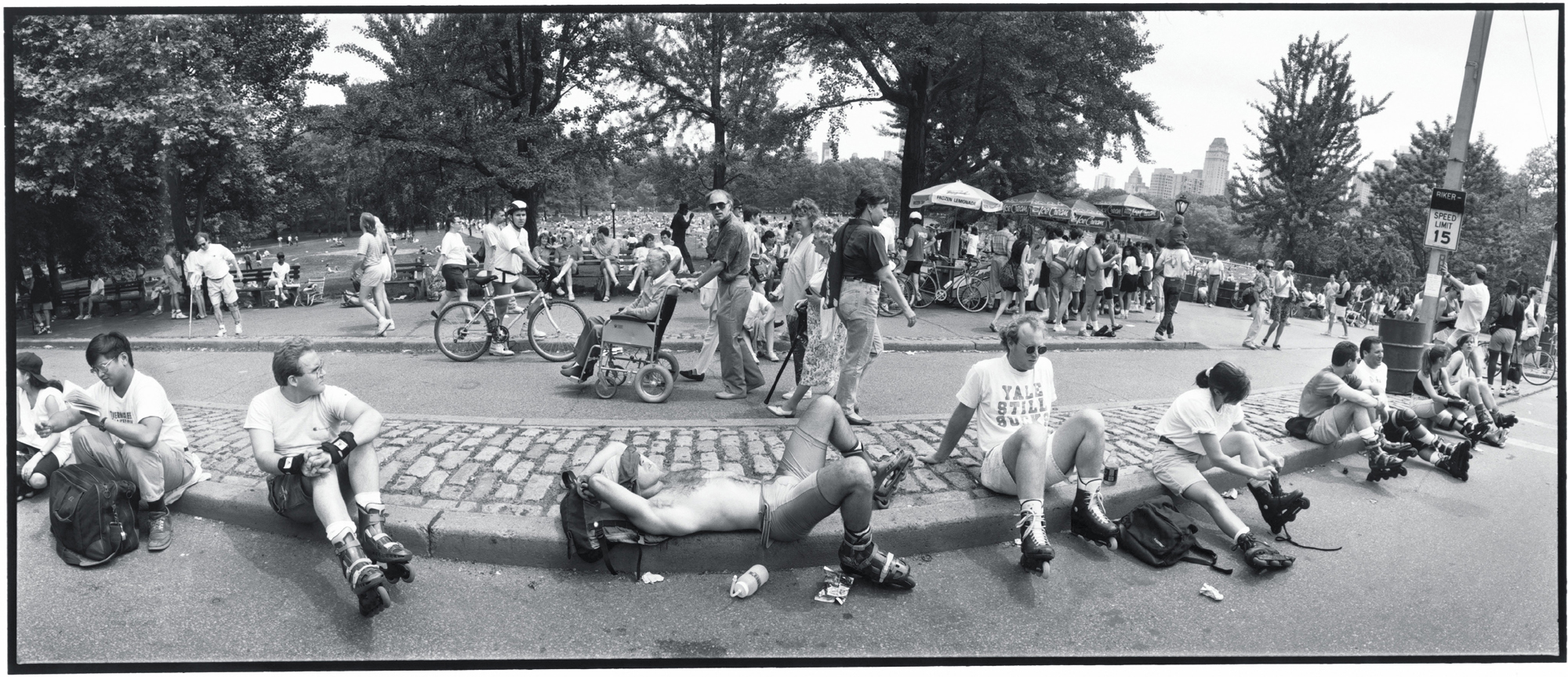

The 843 acres at the center of Manhattan look like a nature preserve with added footpaths and bridges. They are anything but. Every bit of what you see in Central Park, save for the outcrops of Manhattan schist bedrock, is an artful human construct, specified by the landscape architects Frederick Law Olmsted and Calvert Vaux or their successors. The streams were dug by hand before the bridges went over them, all but a few of those trees were placed and planted, and the meadows were graded and sited as thoroughly as a baseball infield might be. Low-lying areas were deliberately flooded into ponds and a reservoir.

A competition in 1857 led to Olmsted and Vaux’s hiring, and the first round of construction ended in 1858, when the park opened to visitors. But it was hardly finished. Trees had been planted as saplings, spaced according to their projected appearance in the far future, when they would coalesce into an arched grove or a deep thicket. A bridge or outbuilding might initially look slightly overscale and ornate when surrounded by nothing, but a generation later it would be enclosed by undergrowth and settled in. (Olmsted and Vaux both lived long enough to see the park largely mature.)

The genius of Central Park’s design takes multiple forms, and its eerily unnatural naturalism is only one. So is the incorporation, new for its time, of active recreation sites like play areas and ball fields. The transverse drives, set below ground level and thus barely disruptive to the parkgoer’s eye, are another—one that seems especially visionary given that they were specified a half-century before the automobile age. In fact, the distinction among drives, footpaths, and bridle paths (which still see a few horses, though not many) remains a significant hierarchy within the park, one that was reinforced in 2018, when—after years of argument, pushback, and lobbying—the shared pedestrian-and-traffic paths were closed to cars for good.

The myriad functions of Central Park on view, 1992.

PHOTOGRAPH BY BRUCE DAVIDSON

Which is not to say that the park has been preserved in amber as Olmsted and Vaux envisioned it. Over the years, it has seen heavy adaptation. A onetime reservoir has long since been filled in to form the Great Lawn. The Metropolitan Museum of Art has encroached. A little bandstand gazebo gave way to the larger Naumburg Bandshell. The highly ornamented building known as the Dairy fell apart and has been restored. The Ramble—from the beginning the most densely planted, seemingly wild portion of the park—became overgrown and tangled, and for a while gained a reputation as a place for sex. Much of the remainder of the park was for a couple of decades known as a dangerous place to be at night, not a place to take a nice walk after dinner but one where you’d be beaten and robbed, or worse. (The rape of a jogger in 1989 near 102nd Street cemented this reputation, and the erroneous conviction and imprisonment of five Black and Latino teenagers for the crime remains a blot on the city’s history.)

For much of its life, the park was undermaintained and drifted into disrepair; only since the 1980 creation of the Central Park Conservancy, a public-private partnership, has the money flowed in and the repairs and maintenance been brought back up to snuff. Today, the park is in far better shape than it has been for a century. It is also, according to officials, suffering from a new problem: overuse. Garbage cans fill up too quickly to be emptied, and lawns wear out under the pressure of too many feet. As in so many other aspects of New York life, many people have come to prefer spending time in Brooklyn—and thus find themselves in Prospect Park, the subsequent project of Olmsted and Vaux. There the designers applied the lessons they’d learned in Manhattan, and in the end they came to believe they’d done a better job the second time out.

Excuse me, are you Jewish? It’s a question posed on street corners to all non-blonds by adherents of the Chabad sect of Judaism, especially on certain Jewish holidays and in the Friday-afternoon hours before the sabbath. Most of those who are accosted mumble out a reply in the negative or keep walking. But if you say yes, you’ll be cheerfully guided in a little exploration of Jewish ritual: perhaps wrapping your arms in tefillin, waving a palm frond on the holiday of Sukkot, or lighting sabbath candles. For you, the experience may be a curiosity; for Chabad believers, it’s a dire obligation, handed down by a now-dead leader whom many adherents regard as the Messiah. Such obligations have motivated Chabad to become one of the most dynamic, proactive forces in Jewish history, taking off from a Brooklyn launching pad and arriving in the four corners of the earth.

Chabad did not originate in New York but came into flower here. The name is an acronym for three Hebrew words—chochmah (“wisdom”), binah (“understanding”), and da’at (“knowledge”)—though it is also known as Lubavitch, after the Russian town where the sect was once based. It’s a strand of the Hasidic movement, which began in eighteenth-century Eastern Europe and in which Jews were encouraged to develop an ecstatic, deeply personal relationship with the Divine. Chabad emerged in 1775 and has been directed by a succession of supreme spiritual leaders known as the rebbes. For well over a century and a half, Chabad was largely a European entity. Then came the Bolsheviks and the Nazis.

The person responsible for the group’s rise in the city was the sixth rebbe, Yosef Yitzchak Schneerson. He had faced tremendous persecution for his beliefs at the hands of the Soviets and sought refuge in Poland, only to find himself once again under threat after the German invasion of September 1939. The U.S. was still neutral in the war, and American Jewish leaders pressed for his rescue. In a truly bizarre turn of events, the German government agreed to send Nazi soldiers from Jewish backgrounds (yes, there were such people) to extract him. In March 1940, Schneerson arrived in Manhattan and permanently moved the center of Chabad life to this country. He saw a unique mission before him: to take the increasingly secular Jewish diaspora in America and make its people believe again.

Schneerson shifted his base of operations to 770 Eastern Parkway in Crown Heights, an area provocatively close to more liberal Jewish populations. (Chabad receives a great deal of criticism from some Jewish communities for its hard-line stances on Israeli security and the strict, traditional rules that govern its adherents, particularly regarding gender roles.) From Brooklyn, he began his program of sending out shlichim (roughly, “emissaries”) in 1950. Chabadniks believe it’s a commandment of the highest order to assist other Jews in being more Jewish, and the sixth rebbe sent out rabbis and their wives to act as spiritual guides for Jews worldwide. His successor and son-in-law, Menachem Mendel Schneerson, took over in 1951 and expanded the shlichim to an extent his predecessor could not have imagined. Chabad outposts now operate in one hundred countries and all fifty states.

Menachem Mendel became the greatest of all the rebbes (two decades after his death, he’s simply known as “the Rebbe” among his followers). After settling here, he almost never left Crown Heights, traveling only occasionally to visit his father-in-law’s grave in Queens. Instead, he held court with visitors ranging from New York mayors to Israeli prime ministers. His operation became a fund-raising dynamo, buoyed by celebrity endorsers like Bob Dylan and frequent Chabad telethon host Jon Voight, and he received commendations from every U.S. president from Nixon onward. Until his death in 1994, he was purported by some to have supernatural abilities and be the long-foretold Messiah. He did not name a successor.

The idea of dripping hot water through coffee grounds held in a paper filter originated with Amalie Liebscher (known by her middle name, Melitta) in Dresden, Germany, in 1908. It reached its aesthetic peak in 1939, when an extremely eccentric inventor in New York, Peter Schlumbohm, developed a borosilicate-glass brewer in the form of a carafe, its wasp waist wrapped in hardwood and a leather tie. It was a Bauhaus-esque product that was affordable and friendly, one that looked like a particularly sleek piece of lab equipment, thus inspiring its name: Chemex.

During the Second World War, when production of metal consumer goods was highly restricted, the glass construction gave Chemex a leg up. In 1942, it made the cover of a Museum of Modern Art publication devoted to superior wartime design and soon entered the museum’s permanent collection. Schlumbohm also created a handsome companion product to boil water called the Fahrenheitor Kettle. Most of his other products, which included the Fahrenheitor Minnehaha aerating pitcher, the Fahrenheitor Bottle Cooler, the Fahrenheitor Ice Vault, and the Cinderella trash bucket—all emanating from his workroom on Murray Street—are long gone.

Although it bobbed up regularly over the years, notably in Mary Tyler Moore’s sitcom kitchen, the Chemex, too, slowly faded from widespread use. Then, in the early 2000s, coffee enthusiasts began to fetishize the so-called pour-over, in which coffee is made, painstakingly, by slowly drizzling freshly boiled water through the grounds off the heat. As it happens, the Chemex brewing method is precisely that, and the pot’s looks jibe with the tech-gadget pour-over aesthetic. The surge in visibility and enthusiasm that the device has recently received may be because, as Schlumbohm put it in 1946, “with the Chemex, even a moron can make good coffee.” Now a family-run operation based in Massachusetts, Chemex continues to produce the kettle and the coffeepot, the latter in multiple sizes and variations, including a mouth-blown version for the uncompromising aesthete.

Fried chicken and biscuits: inescapably a southern thing. Stewed chicken in gravy poured over a waffle: a Pennsylvania Dutch thing. But deep-fried crispy chicken perched on a couple of waffles—well, entities all over the country have tried to claim it, but the most persuasive ones bind it to Harlem. Certainly it could be found there by the mid-1930s; a spirited Bunny Berigan tune called “Chicken and Waffles” was recorded in New York in 1935. Inarguably, the dish’s alpha and omega was Wells Supper Club, which opened on Seventh Avenue (now Adam Clayton Powell Jr. Boulevard) near 132nd Street in 1938. Elizabeth and Joseph Wells’s little restaurant served chicken and waffles from the get-go, and grew famous on it, eventually expanding from a few counter stools to a hopping 250 seats. The Wells was open very late, and as a result it caught the post-nightclub crowd—the dinner rush, dissolving into the early breakfast rush, came at 2 a.m. The dining room was integrated, too, often half Black and half white. By the 1950s, it was prominent enough that Frank Sinatra and Sammy Davis Jr. would show up for a bite after an evening out.

What makes chicken and waffles work as a combination? Some of its deliciousness derives from the texture: two different crispinesses, two similar but not identical batters. The maple syrup ties them together nicely (some diners add jam to the mix, too, or melted butter). It’s also, these days, something you have to seek out. Waffle House, the chain that’s everywhere in the Deep South, doesn’t do fried chicken; fast-food places like Popeyes and KFC don’t sell waffles; and Wells Supper Club is gone, closed in 1982. But you can find it on a good scattering of New York City restaurant menus or any day at the celebrated Los Angeles mini-chain Roscoe’s House of Chicken and Waffles. Barack Obama dropped by there, unscheduled, for a bite in 2011, and the presidential order—the menu’s No. 9—is now called Obama’s Special.

Although all museums are in a sense children’s museums, the world’s first devoted entirely to kids and their interests is the Brooklyn Children’s Museum, opened in 1899 on the grounds of Bedford Park (now Brower Park) in Crown Heights. Its exhibits, in its earliest days, included natural-history artifacts—shells, minerals, stuffed birds—that city children might not otherwise encounter, and over time came to include jigsaw puzzles and other hands-on items. That interactivity-and-play aspect has come to dominate the children’s-museum experience, especially at halls of science like the Exploratorium in San Francisco, opened in 1969, and its East Coast counterpart the New York Hall of Science, created for the 1964–65 World’s Fair. The Brooklyn Children’s Museum continues to operate in its now expanded building in Brower Park.

4 Five Museums Made for Kids

Children’s Museum of the Arts (103 Charlton St.) offers classes and studio activities including animation, sound design, and a “clay bar,” where kids can sculpt.

Children’s Museum of the Arts (103 Charlton St.) offers classes and studio activities including animation, sound design, and a “clay bar,” where kids can sculpt.

New York Hall of Science (47-01 111th St., Corona, Queens), which made its debut at the 1964 World’s Fair, helps children learn about space, explore animated worlds, or just play mini-golf outside.

New York Hall of Science (47-01 111th St., Corona, Queens), which made its debut at the 1964 World’s Fair, helps children learn about space, explore animated worlds, or just play mini-golf outside.

DiMenna Children’s History Museum (170 Central Park West) provides a full immersion into 350 years of New York and American history with live reenactments on weekends.

DiMenna Children’s History Museum (170 Central Park West) provides a full immersion into 350 years of New York and American history with live reenactments on weekends.

National Museum of Mathematics (11 E. 26th St.), also called MoMath, features interactive exhibits and a tessellation station.

National Museum of Mathematics (11 E. 26th St.), also called MoMath, features interactive exhibits and a tessellation station.

Children’s Museum of Manhattan (212 W. 83rd St.) is a 40,000-square-foot, five-story complex where kids can engage in imaginative play and art and water activities while exploring dozens of interactive installations.

Children’s Museum of Manhattan (212 W. 83rd St.) is a 40,000-square-foot, five-story complex where kids can engage in imaginative play and art and water activities while exploring dozens of interactive installations.

A surprising amount of early TV history dates to one crucial event: the 1939 World’s Fair in Queens, which early television entrepreneurs used as a platform to introduce the nascent technology to a wider public. (RCA introduced its first line of television sets there too.) W2XBS, the experimental broadcast station that would later be renamed NBC, began regular transmissions during the first week of the Fair that April, bringing about several important TV milestones: the first televised presidential speech (FDR, at the opening ceremony), the first televised jugglers, and, on May 3, 1939, the first televised Walt Disney cartoon, a short called “Donald’s Cousin Gus” (in which Gus Goose comes to visit and eats all of Donald’s food).

Recurring commercial TV shows for kids didn’t begin until several years later, when the DuMont network began airing Small Fry Club (originally titled Movies for Small Fry) on March 11, 1947. It featured stand-alone cartoons, puppet segments, and other short stories meant to entertain while promoting good behavior. In one early sketch, Small Fry’s narrator, “Big Brother” (played by Bob Emery), tells viewers to send postcards to a post-office box at Grand Central Station with details of any vacations they’d been on. The program lasted only four years but became one model for children’s programming, offering a combination of interactive appeals, variety-show-style short segments, and a mix of songs, puppets, cartoons, and live-action material. The similarly structured Howdy Doody Show premiered later in 1947 and became an enormous hit, making the format a standard for decades.

Big Bird, originated by Caroll Spinney.

PHOTOGRAPH BY VICTOR LLORENTE

That formula was upended in 1969 with the arrival of Sesame Street, which grew out of the newish educational-television movement that prioritized learning as well as entertainment. The show, created by Joan Ganz Cooney, was also intended to span divides of class and wealth; its setting was not a white-picket-fence scene out of Mark Twain but a sooty-looking city street with brownstone stoops, a small grocery store on the corner, and a grouch living in the beat-up trash can out front. In its early days, it fell short of achieving its goals of representation—among other things, the original Muppet characters were almost all male, and there was no Spanish-speaking presence, although both those problems were eventually addressed—but its performers were absolutely real, its instincts urban, and its songs reminiscent of street jump-rope chants. Parallel versions have included productions in Russian, Hebrew, and Pashto. If you measure by pop-culture stickiness after 50 years, Sesame Street is arguably the most far-reaching television series ever. Its worldwide audience today is said to be at least 156 million children. A plurality of TV-watching adults today grew up with Big Bird and Oscar or their international cousins.

When Reinhold Niebuhr came to New York in 1928, he considered himself a radical pacifist and socialist. But the rise of Hitler in the 1930s, while Niebuhr was teaching at Union Theological Seminary uptown, changed his mind. In a series of books, starting with Moral Man and Immoral Society in 1932, he began arguing that liberal Protestantism, which regarded history as an endless march of progress toward utopia, was dangerously naïve. It failed to account for the fallenness of human nature, for the evil that people are prone to commit. Christian moral duty, he wrote, sometimes demands military action.

Niebuhr wasn’t making a plug for American exceptionalism. Just as dangerous, he thought, was the notion of America acting as God’s envoy, trying to set history on the right course. In his 1952 masterpiece, The Irony of American History, he uses the word irony in the dramatic sense: the condition that applies when the audience understands more about what’s happening onstage than a character does. America, he suggested, is the character that doesn’t know where history is headed. It’s difficult for humans to accept that “the whole drama of history is enacted in a frame of meaning too large for human comprehension or management.”

All of this explains why U.S. politicians, both hawks and doves, love to cite him as an influence. He’s easy to invoke but hard to reckon with, and applying Christian realism to real life is harder still. “At best, Niebuhr’s counsel serves as the equivalent of a flashing traffic light at a busy intersection,” wrote the historian and former Army officer Andrew Bacevich. “Go, says the light, but proceed very, very carefully. As to the really crucial judgments—Go when? How fast? How far? In which direction?—well, you’re on your own.”

Twenty centuries ago, during the reign of Caesar Augustus, two young Brooklyn residents named Joseph and Mary made their way to a hotel in lower Manhattan, where they were denied a room for the night and instead lay down in a nearby parking garage…

All right, fine. New York City can claim a lot, but not the arrival of the Christian Messiah. But your idea, your image, your very concept of an American Christmas was utterly shaped by New York’s celebrations and creations. The Puritans, arriving in Massachusetts in 1620, had outlawed Christmas, disdaining its pagan winter-solstice roots. Elsewhere in the colonies and then the United States, it was banned to cut back on the carousing it encouraged—though not in New Netherland, where Dutch holiday gift-giving traditions persisted. In 1809, the widely read New York writer Washington Irving published his delightful if only half-true A History of New York, in which he spuriously claimed that the Dutch ship that carried the first scouting party to land in New Amsterdam carried before it the image of St. Nicholas. Ten years later, in another best seller, The Sketch Book of Geoffrey Crayon, Gent., he laid out images of Christmases past in England: “The old halls of castles and manor-houses resounded with the harp and the Christmas carol, and their ample boards groaned under the weight of hospitality. Even the poorest cottage welcomed the festive season with green decorations of bay and holly—the cheerful fire glanced its rays through the lattice, inviting the passenger to raise the latch, and join the gossip knot huddled round the hearth, beguiling the long evening with legendary jokes and oft-told Christmas tales.” Irving described Christmas Eve celebrations, candles, mistletoe, and gifts for children. Americans over the next couple of generations bought it all and gradually blew up a version of this imagined Britain to larger-than-life size.

In 1821, another New York writer, Arthur J. Stansbury, put St. Nick, who had heretofore traveled by horse and carriage, into a sleigh drawn by reindeer. Two years later, Clement Clarke Moore, living in a house on West 22nd Street, published the poem “A Visit from St. Nicholas.” Better known by its first words, “ ’Twas the night before Christmas,” it cemented the eight-tiny-reindeer-on-the-roof story forevermore. Santa’s physical appearance became codified during the Civil War, when the New York political cartoonist Thomas Nast began drawing him in Harper’s Weekly as a round figure with a big beard (and identifying him with the North rather than the South; the politicization of Christmas is apparently nothing new). Within a few years, Macy’s started dolling up its Yuletide displays (see also DEPARTMENT-STORE HOLIDAY WINDOW DISPLAY) and eventually created another kind of spectacle to kick off the shopping season (see also MACY’S THANKSGIVING DAY PARADE). The quintessential Christmas movie even name-checks a New York thoroughfare in its very title, Miracle on 34th Street. And where is the country’s collective public Christmas tree? Yes, there’s one on the White House lawn, but the crowds all gather at Rockefeller Center.

The lit candles traditionally decorating a Christmas tree were certainly a lovely thing to see—and also a spectacular fire hazard. In 1882, mere weeks after the Edison Electric Light Company began to send power to its downtown customers (see also ELECTRICAL GRID), an Edison executive named Edward H. Johnson tried something new. He wired 108 little handmade lightbulbs into strings and, hoping to get some attention for the new company, invited reporters to see them draped around a pine tree and across the ceiling in his home on West 12th Street. The tree was mounted on a little wooden box with a motor, so it spun. By 1894, the White House had Christmas lights on its tree, and by 1903, General Electric (descended from Edison’s company) was selling them in sets. Today, the U.S. imports half a billion dollars’ worth of Christmas-tree lights each year.

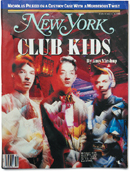

The term club kids precisely describes a subculture of nightclubgoers who came to prominence in the downtown New York scene of the late 1980s. Some were middle class, others affluent, but all were teenagers or in their early twenties who were fantastically, raucously stylish (or aspired to be). In the preceding few years, the disco scene had largely given way to more sedate venues populated by relatively conservative customers—but then came this new bunch of much younger people dressed in insane ensembles showing up at outré clubs like Tunnel in far-west Chelsea. They were relatively straight-edge when it came to drug use (at least at first). According to Michael Alig, who was among the earliest club kids, the new threat of AIDS meant “it was now all going out and looking very freaky so that nobody would have sex with you.”

The “club kids” moniker first appeared in the March 14, 1988, issue of New York, headlining a cover story about the scene by Amy Virshup. The kids subsequently gained national visibility on the daytime-talk-show circuit, most memorably in a 1993 episode of The Joan Rivers Show. Hosting, as she called them, “five simple people with a dream and a wardrobe from hell,” Rivers chatted with Alig, Amanda Lepore, James St. James, Ernie Glam, and the soon-to-be-legendary London-based performance artist and club manager Leigh Bowery, whose faux bosom Rivers envied. As she grilled them about trends and moneymaking and repeatedly called them “adorable,” her cheerful, supportive tone was infectious. “They’re not hurtin’ nobody” was the prevailing viewpoint from the crowd.

When New York asked Virshup to revisit her club-kid subjects thirty years later, Alig (who by then had served 17 years in prison for manslaughter in the death of another club kid, Andre “Angel” Melendez) asked her where she’d picked up that phrase. Said Alig, “We didn’t call ourselves that.” Virshup suggested she might have made it up, and Alig responded, “When it was on the cover, we were like, Oh my God, that’s what we are.”

Finding America’s Ur–club sandwich is a tall order, kind of like the towering dish itself. Two origin stories, both New York–based, compete for authenticity: One traces the sandwich to the club cars of trains departing the city at the turn of the century (perhaps its layers—bread, meat, bread, meat, bread—mimicked the two-decker passenger cars popular in Europe at the time); another claims the name is short for the “clubhouse sandwich,” which appeared around the same time in men’s social clubs. The earliest published recipes date to 1889. The New York Sun described the ingredients for the Union Club’s sandwich as heretofore “a mystery to the outside world” and promptly revealed all… three of them: two slices of wheat toast, ham, and either chicken or turkey, served warm. “It differs essentially from any other sandwich made in the town,” the paper told readers, calling it the go-to dish “of club men who like a good thing after the theater or just before their final nightcap.”

The Sun’s editors wouldn’t recognize today’s club, not so much because the modern version, served everywhere from Hong Kong to Barcelona, adds lettuce, tomato, and mayo and jabs a frilly toothpick into each stack, but more because it gained that middle slice, likely in the early 1900s. That extra piece chafed purists and was bemoaned over the years by such authorities as Town & Country food editor James Villas and James Beard himself. Beard warned in 1972 that it had “bastardized” the sandwich. “Whoever started that horror,” he wrote, “should be forced to eat three-deckers three times a day the rest of his life.” (Critics might retort that Beard’s preference goes by a different name: the chicken BLT.)

Three slices have become the club’s hallmark, at any rate. Enough that the term has been expanded to describe various multilayered inedible things as well: Jupiter’s moon Ganymede, which may contain several alternating layers of ice and water, is a “club-sandwich moon.” Meanwhile, club-sandwich generation refers to the unlucky adults who support their elderly parents, their grown-up children, and their grandkids, all at once.

In November 1900, the deans and presidents of fifteen elite American schools met at Columbia University to lay down a plan for standardized admissions tests. The group voted to call itself the College Entrance Examination Board, and their planned exam was quite different from today’s: a little bit of English-literature analysis; grammar in Latin, Greek, and French; and some (relatively primitive) physics, chemistry, zoology, botany, and mathematics. It did indeed screen students for college—or rather for the elite education of the era, a high-minded certification for a few thousand sons and daughters of the well-off.

During World War I, the United States began intelligence-testing Army recruits, and after the armistice, the College Board, working with a Princeton psychology professor named Carl Campbell Brigham, began to experiment along similar lines. The result, in 1926, was the creation of the Scholastic Aptitude Test, a standardized exam of vocabulary exercises, number puzzles, and analogies. As a measure of intelligence, the original SAT seems rudimentary, naïve, and just plain odd today, with questions like

Of the five things following, four are alike in a certain way. Which is the one not like these four?

(1) tar (2) snow (3) soot (4) ebony (5) coal

and

A tree always has

(1) leaves (2) fruit (3) buds (4) roots (5) a shadow

But even this improved on what had come before. James Bryant Conant, the president of Harvard University, championed the SAT as a democratizing admissions tool, a meritocratic counterbalance to the my-prep-school-headmaster-called-the-admissions-office method. And indeed, Harvard in Conant’s era achieved a (limited) new measure of openness.

By the 1960s, a more sophisticated and nuanced SAT had been adopted by virtually all American colleges, even as it became evident that it was full of inherent biases against nonwhite and nonaffluent students. Since then, the test has been reworked again and again, with major changes put in place every decade or so; the scoring system has been adjusted numerous times. The old name, “Scholastic Aptitude Test,” gave way to the less loaded “Scholastic Assessment Test” and then to the officially rootless initialism SAT. Some elite schools now treat the exam (and its competitor, the ACT) as optional, and many more consider it a modest part of their admissions decision. But will they still take notice of a kid who scores a perfect 1600? The answer is almost surely (a) yes.

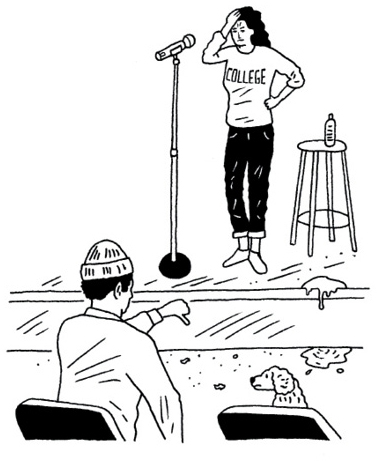

Stand-up comedy, a definitively American and particularly New York art form, took decades to assert that it deserved to be the centerpiece of a night of entertainment. To paraphrase one of its great practitioners: It got no respect. In its earliest days, stand-up was performed in burlesque and vaudeville theaters (see also BURLESQUE, AMERICAN STYLE; VAUDEVILLE) on mixed bills with singing and dancing. In the early 1950s, the action moved to (often mob-run) Vegas nightclubs or (often mob-run) Vegas-style nightclubs. Then the shift began, as the likes of Lenny Bruce, Mort Sahl, Jonathan Winters, Joan Rivers, and Shelley Berman began making stand-up more personal and cerebral, at jazz clubs, Beatnik bars, coffee shops, and small downtown theaters. By the 1960s, with Attorney General Robert Kennedy cracking down on the Mafia, it was clear comedians deserved a space of their own.

George Schultz, a failed comic with such a sense of talent that comedians called him “the Ear,” gave them the first one. In 1962, in Sheepshead Bay, Brooklyn, he opened Pips (named for his dog and his favorite Dickens character), a club that showcased up-and-coming singers and comedians. Despite its being inconvenient to Manhattan, Pips attracted enough attention over the years to host talent like Rivers, George Carlin, Andy Kaufman, and Billy Crystal, among many others. It launched the careers of Rodney Dangerfield and David Brenner. And despite the neighborhood’s rough edges (morning DJ “Goumba Johnny” Sialiano called it a place where “you could get heckled by the bartender”), the New York Times later labeled it “an Algonquin Round Table for a generation of comedians.”

In 1963, aspiring Broadway producer Budd Friedman opened the folk-music venue the Improvisation in Hell’s Kitchen, where he kept a redbrick wall behind the stage because he couldn’t afford to drywall, inadvertently creating the much-copied stand-up backdrop. Comedy’s increasing popularity made these two clubs into showcases exclusively for stand-up, ascribing new value to the form and changing it nearly overnight. No longer were audiences just looking for a nice evening out—they were expecting to laugh. Comedians had to be faster, funnier, and always writing new material. In 1975, Friedman opened a second Improv in Los Angeles, joining the already popular Comedy Store, owned by Mitzi Shore. On the West Coast, the rooms were bigger and filled with talent scouts (in part because Johnny Carson had moved The Tonight Show to Burbank). From then, the stereotypes of the New York and L.A. comedy scenes were set: New York is where you go to get good, and L.A. is where you go to get noticed. By the 1980s, however, the road was where stand-ups went to get paid, and Friedman opened Improvs all over the country, soon joined by Chuckle Huts and Ha-Has and a plethora of stupidly named clubs. The Comedy Boom was on, and it was promptly followed by a comedy bust, owing to an oversupply of venues undersupplied with real talent.

Partly out of a desire to move past the joke-after-joke demands of the clubs, and partly because most of those clubs had closed (Pips, after a long twilight, shuttered for good in the mid-aughts, and the New York Improv went bankrupt in 1992 and subsequently closed, although there are more than twenty locations in other cities), stand-ups in the 1990s began to look for whatever venues they could find to develop their craft, in the process creating what would become known as alternative comedy. By the early aughts, some of its practitioners (Eugene Mirman, Janeane Garofalo, Amy Poehler) had found permanent New York homes without all the trappings of a comedy club (no drink minimum, fewer hacks) in places like Luna Lounge on the Lower East Side, Rififi in the East Village, and the Upright Citizens Brigade Theatre in Chelsea. They created a second comedy boom, one that was somewhat more accepting of brainy, unconventional talent. More recently, the Comedy Cellar in Greenwich Village has established itself as the national standard-bearer, the comic’s hangout of choice. But a lot of stand-up is taking place in hybrid performance spaces, like Union Hall and Littlefield, venues within blocks of each other near the Gowanus Canal. On most nights today, the best comedy in America is once again happening in Brooklyn.

5 Tips for Becoming a Stand-up

From comedian Charlie Bardey

Focus on getting actually good, not on building your career. “Think about what you think is funny and how you can share that with other people.”

Focus on getting actually good, not on building your career. “Think about what you think is funny and how you can share that with other people.”

Find a job you can actually stand. “Like, be a museum educator or something.”

Find a job you can actually stand. “Like, be a museum educator or something.”

Make friends and champion their work. “A rising tide lifts all boats.”

Make friends and champion their work. “A rising tide lifts all boats.”

Develop a skill that’s not stand-up. “So when you don’t feel like stand-up is going well, you can still have a sense of self-worth.”

Develop a skill that’s not stand-up. “So when you don’t feel like stand-up is going well, you can still have a sense of self-worth.”

Prepare to be humbled. “You will spend $14 on a car to a show where you will bomb in the back room of an overpriced faux dive bar for three people, one of whom is your mom.”

Prepare to be humbled. “You will spend $14 on a car to a show where you will bomb in the back room of an overpriced faux dive bar for three people, one of whom is your mom.”

The American comic book was built on a foundation of iniquity. Its not-so-reputable parents, publications known as “nudies” and “smooshes,” were two genres of the so-called pulp magazines of the 1920s. Pulps got their name from their low-grade paper stock, and their contents were as degraded as the material they were printed on. Smooshes were primarily about sex and danger, whereas nudies depicted, as one might expect, women wearing just enough to keep the publisher out of jail. (Even if he did get a slap on the wrist, he could easily pay off someone at City Hall and escape.) Wasps in the established literary houses had no interest in publishing such things, but a smattering of Jews from immigrant families picked up what others wouldn’t touch.

Those publishers made comic books popular, but volumes of comic strips had been being compiled since at least the 1840s, and an 1897 book of the New York World’s “The Yellow Kid” strips (see also YELLOW JOURNALISM) seems, on its back cover, to have first used the term comic book. But these publications looked very little like a modern comic book. Only in 1929 was that kind of object produced, when publisher George T. Delacorte Jr. released The Funnies, an insert for tabloid newspapers that was filled with strips that hadn’t been picked up by the syndicates that ruled the industry.

It was a flop on the newsstands and canceled in the autumn of 1930. But all was not lost. Maxwell Charles Gaines, a necktie salesman and ex-teacher who was looking to score big in the depths of the Great Depression, linked up with a Connecticut publisher called the Eastern Color Printing Company and worked out a deal to repackage its hit newspaper strips in a new booklet called Funnies on Parade. It was released in 1933 as a coupon giveaway from Procter & Gamble and did well, leading to a follow-up called Famous Funnies, which can unreservedly be called a comic book, given that it was sold on its own and had a wraparound cover. A different publisher, Malcolm Wheeler-Nicholson, went even further a year later, when he put together National Allied Publications and, in 1935, released New Fun, the first comic book to feature new material.

When Harry Donenfeld, who’d established himself as a pornography publisher, got involved, the pulps started to soar. He was a Romanian Jewish immigrant from the Lower East Side who was allegedly so mobbed up that he’d helped Frank Costello smuggle liquor from Canada in boxes intended to hold paper. In the mid-1930s, New York’s mayor, Fiorello H. La Guardia, decided to crack down on vice, wrecking the business of nudies and smooshes. Jack Liebowitz, Donenfeld’s business manager, connected with Wheeler-Nicholson, and the men all went into business together. Store owners were always uptight about selling girlie rags, and Liebowitz and Donenfeld could sweeten deals if they threw in some clean fun for the kids.

They struck gold with a series of runaway hits. Other low-rent publishers got onboard, turning comics into a nationwide fad. The contents typically hewed close to the sci-fi, crime, and adventure stories in the era’s other youth magazines. But only when Donenfeld and Liebowitz kicked Wheeler-Nicholson out of National and one of their employees found an intriguing slush-pile submission did things really get going. The lead character in the story was the brainchild of two Jewish kids from Cleveland, Jerry Siegel and Joe Shuster, and he was called Superman. The hero made his debut in National’s Action Comics No. 1, whereupon the comic-book business finally took flight.

6 The City’s Best Comic-Book Stores

Chosen by comic-book artist Fred Van Lente

Desert Island Comics (540 Metropolitan Ave., Williamsburg) “Like an old ’60s head shop that would have sold R. Crumb’s Zap Comix.”

Desert Island Comics (540 Metropolitan Ave., Williamsburg) “Like an old ’60s head shop that would have sold R. Crumb’s Zap Comix.”

Bulletproof Comics (2178 Nostrand Ave., Flatbush) “Right around the corner from Brooklyn College, it has been around since the ’90s. The owner, Hank Kwon, has stayed successful by knowing his customers.”

Bulletproof Comics (2178 Nostrand Ave., Flatbush) “Right around the corner from Brooklyn College, it has been around since the ’90s. The owner, Hank Kwon, has stayed successful by knowing his customers.”

Midtown Comics Downtown (64 Fulton St.) “The best signings in the city. The staff is super-knowledgeable.”

Midtown Comics Downtown (64 Fulton St.) “The best signings in the city. The staff is super-knowledgeable.”

Mysterious Time Machine (418 Sixth Ave.) “Basically a basement room down concrete stairs, it’s filled with boxes upon boxes of old comics—but they have this week’s latest titles, too.”

Mysterious Time Machine (418 Sixth Ave.) “Basically a basement room down concrete stairs, it’s filled with boxes upon boxes of old comics—but they have this week’s latest titles, too.”

Forbidden Planet (832 Broadway, near 13th St.) “Probably the best overall comics store in the city—big, clean, and you’re not constantly tripping over other people.”

Forbidden Planet (832 Broadway, near 13th St.) “Probably the best overall comics store in the city—big, clean, and you’re not constantly tripping over other people.”

No New York invention has arguably saved more lives in the past 26 years than CompStat, the computer system introduced by the NYPD in 1994. It has helped drive down the city’s crime rates to historic lows and revolutionized policing around the world. Los Angeles, London, and Paris use a form of CompStat, while Baltimore has CitiStat, and New Orleans has BlightStat. Its basic practices lie in the massing and sorting of data to find spots where a lot of crime is taking place, allowing police to focus on those locations.

It all started in a much different city from today’s New York. Jack Maple was a 41-year-old former “cave cop,” a veteran of the then-separate Transit Police Department who had developed an off-duty taste for homburg hats, bow ties, spectator shoes, and the Oak Bar at the Plaza. While patrolling the decaying subway of the ’70s and early ’80s, Maple had assembled what he called “Charts of the Future,” paper maps into which he stuck color-coded pins to track crime. It sounds simple and fairly obvious, but no one in New York’s police departments had done it until Maple, who soon was locking up dozens of gang members and getting promoted to lieutenant. At night, he parked himself at his table at Elaine’s and watched closely as the owner, Elaine Kaufman, monitored every waiter and bar tab. Maple wrote four goals on a napkin: accurate, timely intelligence; rapid deployment; effective tactics; relentless follow-up and assessment (see also “BROKEN WINDOWS” POLICING). After Maple became the NYPD’s top anti-crime strategist under the incoming police commissioner Bill Bratton in 1993, those principles, called CompStat, began to be disseminated through weekly meetings at police headquarters. Within weeks, crime rates started to plunge, and they have never really stopped.

That’s the beloved, mostly true myth, anyway. Maple’s friends admit that “the Jackster,” who died in 2001, may have embellished a bit of the CompStat origin story. Bratton is quick to say that he was using wall charts to identify crime hot spots as a young sergeant in Boston in 1976. Later, hired as New York’s transit-police chief under Mayor David Dinkins, Bratton recognized a like-minded ally in Maple, and when Bratton returned to the city as police commissioner for new mayor Rudy Giuliani, Maple was one of his first hires. “Maple’s concepts met Bratton’s systems, and that’s what this is actually all about,” said John Miller, Bratton’s press spokesman in 1994 and today the NYPD’s deputy commissioner for intelligence and counterterrorism.

CompStat has plenty of detractors, who say it helped fuel the stop-and-frisk harassment of hundreds of thousands of Black and brown New Yorkers. There is also debate about just how much credit CompStat, and the NYPD, deserves for the crime decline. Cities including Houston and Phoenix saw similar drops and attribute them mostly to economic development and community policing. Others place some credit on private security, like business-improvement districts and anti-theft systems like LoJack. “Two decades of an expanding economy, and mass incarceration, have contributed the most to the crime drop,” said Rick Rosenfeld, a professor of criminology at the University of Missouri, St. Louis. “Smarter policing, informed by digitized crime data, has contributed in a number of places, including New York City. But we don’t know how much.” We do, however, know what happened. In 1991, the city had more than 2,000 murders for the second year in a row. In 2017, the total dipped under 300, the lowest it had been since 1951.

Virgin Warrior—Two Hearts, a 2006 conceptual piece that Marina Abramovic described as a reflection on “the power of female energy.”

PERFORMANCE BY MARINA ABRAMOVIC WITH JAN FABRE

By the late 1960s, something had to blow in the stupendously speeded-up molecule that was the New York art world. What came to be known as Conceptual Art was the Krakatoa super-eruption from which art is still feeling the aftereffects.

In the postwar years, the work fashioned by a group of straggling New York painters (see also ABSTRACT EXPRESSIONISM) had grown into the first American art movement with international repercussions, but it was soon eclipsed by Jasper Johns, Robert Rauschenberg, and the new mega art market that was burgeoning in the city; this was followed by Pop Art (see also POP ART), which almost instantly mutated into Minimalism. In the span of just 15 years, one world was born, died, was reborn, and then kept mutating. Conceptual Art was delineated in 1969 at the School of Visual Arts by one of its early proponents, the artist Joseph Kosuth, who wrote that “all art after [Marcel] Duchamp [the creator in 1913 of the first readymade, a bicycle wheel mounted on a stool] is conceptual in nature because art only exists conceptually”—meaning that art, while acknowledging the importance of all the styles that came before it, could now be reduced to what seemed to be its philosophical essence, its idea.

In New York, Vito Acconci masturbated under the floor of a gallery and called it art; Sol LeWitt wrote out instructions for other people to execute his drawings on walls, and collectors purchased the instructions; Mel Bochner measured art galleries; Hans Haacke documented the right-wing ties of museum board members; and William Wegman made comedic videos of himself and his Weimaraner, Man Ray. In California, Chris Burden had a friend shoot him in the arm with a .22 rifle, and Bruce Nauman videotaped himself doing funny walks in his studio. Marina Abramovic traded places with a prostitute for a night during the run of her show in Amsterdam, and Robert Smithson built the great earthwork called Spiral Jetty in the Great Salt Lake. Conceptual Art encompassed almost anything, including earth art, performance, video, dance, filmmaking, and simply speaking, all the while, and most important, using photography and text. This triggered a reconfiguration of more than a hundred years of photography, from a fine art judged like painting to a tool used by anyone who chose to, creating whole new criteria for art and giving rise to other New York artists like Cindy Sherman, Barbara Kruger, Jenny Holzer, Richard Prince, and Robert Gober.

By the 1970s, money had left the art world, and cities began to fall into disrepair. All over the world, artists started living together cheaply in clusters functioning almost like tribes, their hive minds working on thousands of shared and sharpened Post-Minimalist issues. For better and worse (worse being that only the artists and their cadres had any idea what certain work was about), art withdrew from the wider world of commerce. Criticism totally changed. New art theories blossomed everywhere and became part of social movements like Black Power, feminism, gay liberation, the antiwar protests, and scores of other radical thrusts at Establishment values around the world. This reshaped the art world as well as art itself. Art school was now the rule, rather than the exception; everyone knew the codes, meanings, and secret handshakes, what felt “real” and what felt like a past that had to be questioned or moved on from. The art world began to grow exponentially with the idea that anyone could be an artist. It was art liberation.

In 1968, Kathie Sarachild, an early member of a feminist group called New York Radical Women (see also RAPE, MODERN VIEW OF), wrote an essay titled “A Program for Feminist Consciousness Raising.” “In our groups,” it read, “let’s share our feelings and pool them. Let’s let ourselves go and see where our feelings lead us.” New York women soon began gathering in apartments to discuss, often for the first time in their lives, the circumstances of their gender—from their husbands’ unwillingness to wash the dishes or change diapers to stories about backroom abortions or the “myth of the vaginal orgasm” (as the title of Anne Koedt’s pioneering essay phrased it). These meetings were often a thrilling, heady experience. As the activist Chude Pamela Allen recalled to New York for a story on NYRW’s fiftieth anniversary, “Somebody was commenting about her boyfriend saying something to her, and everybody in the room went: ‘Oh my God. That’s exactly what mine says to me.’ ” Robin Morgan, another participant, remembered, “I admitted that on occasion in my marriage I had faked an orgasm. I was convinced that I was the only person in the world sick and perverse enough to have done this. Every woman in the room said, ‘Oh, you too?’ It was an amazing moment.”

By the mid-’70s, consciousness-raising had found its way into pop culture. In the 1975 social-satire horror film The Stepford Wives, Joanna and her friend Bobbie (newly resettled in the Connecticut suburbs, they confide that they were involved in “women’s lib” in the city) attempt to organize a consciousness-raising group for the women of Stepford after noticing their submissiveness. Turns out they’re more interested in sharing home-cleaning tips because they’ve been murdered and replaced with subservient fembots.

For some real-life practitioners, consciousness-raising, once seen as radical, began to feel more like a drawn-out group-therapy session, as the original idea that it would ignite widespread activism hadn’t panned out. By the 1980s, the practice as such had mostly withered. Nevertheless, it’s hard not to see all that sharing as a forebear of everything from the 44,000 Lean In Circles across the world to Me Too.

7 Classic Forms of Resisting Consciousness

Excerpted from Kathie Sarachild’s Outline for Consciousness-Raising (1970)

“OR, HOW TO AVOID FACING THE AWFUL TRUTH:

Anti-womanism

Glorification of the Oppressor

Excusing or Feeling Sorry for the Oppressor

Romantic Fantasies

‘An Adequate Personal Solution’

Self-cultivation, Rugged Individualism

Self-blame

Utra-militancy, etc.”

Richard Hofstadter’s landmark book The American Political Tradition, released in 1948, details how a number of presidents—including Jackson and Lincoln—seemed to improvise their political philosophy as they went along. Despite this, the historian argues that there’s a through line to their behavior: a bourgeois capitalist ethos, an attachment to private property and individualism.

Hofstadter, a Columbia professor, was responding to the left-wing historians who had dominated the field during his own education, particularly Charles Beard, who saw American history as the history of class conflict. Hofstadter was arguing the opposite: that deep down, everyone had always agreed, or at least everyone who wielded much power.

This concept resonated with other historians of his generation, and in books like The Genius of American Politics and The Liberal Tradition in America, they praised the consensus as a mark of America’s greatness. But for Hofstadter, the consensus was a cause for shame. “I hate capitalism and everything that goes with it,” he once told a friend.

Like children’s programming, commercial-television cookery originated during the first week of W2XBS broadcasting during the New York World’s Fair at the end of April 1939, with one fifteen-minute segment hosted by a man named Tex O’Rourke. Network internal records list it with the title “How to Roast a Suckling Pig.”

When regular TV broadcasting began in 1946, one of the first half-dozen series to make it into rotation was James Beard’s I Love to Eat, which debuted as part of a program called Radio City Matinee and was broken out into its own time slot later that year. As a live-broadcast cooking show, I Love to Eat (sponsored by Borden Dairy’s Elsie the Cow) presented some challenges. “Jim would perspire a great deal,” remembered producer E. Roger Muir several decades later. “We would be concerned about keeping him presentable. But at the end of the shows, the crew ate pretty good food.” Beard was only moderately successful, because he was not entirely comfortable on-camera and was slightly too early to the medium—in 1946, a lot of TVs were still in bars, and the audience there was mostly men who were not inclined to go home and immediately roast a chicken. A few years later, in 1962, Julia Child, who had become good friends with Beard, stepped behind a counter on a soundstage in Boston to tape her first show. She turned out to have the broadcasting secret sauce that Beard had lacked, and American food has never looked back.

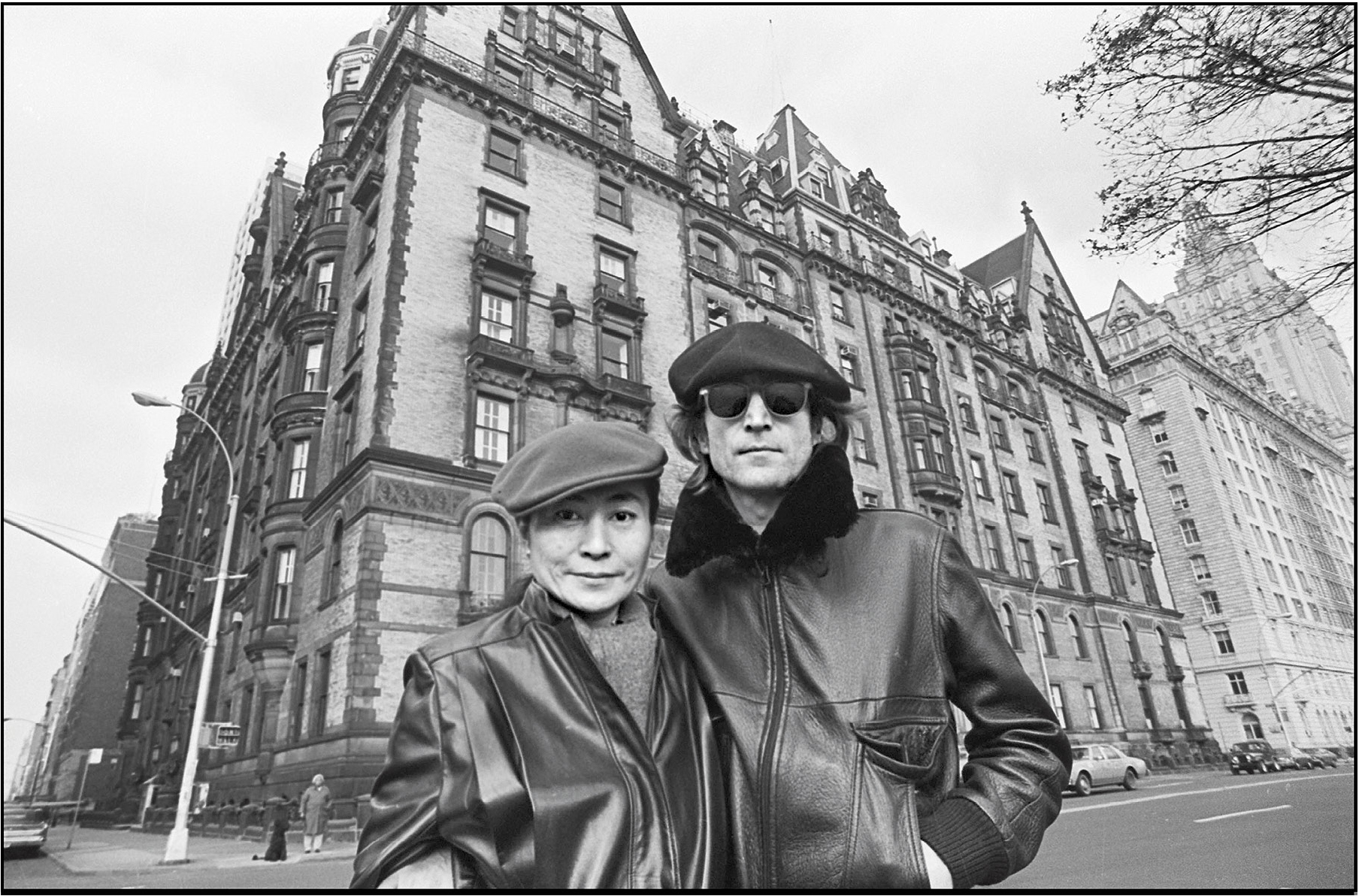

John Lennon and Yoko Ono, noted co-op apartment shareholders, at the Dakota in November 1980.

Co-ops, in which groups of people pool their resources to live communally and thus less expensively, seem to have originated in the U.K. As the financial structure for residents of an apartment building, however, the co-op is almost entirely identified with New York. (A few co-ops exist in Washington, D.C., and other cities, but nothing like the number here.) In a co-op, residents buy shares of ownership in a building rather than actual cubic footage. They designate a board to manage finances and maintenance and pay monthly fees to cover the costs of services, upgrades and repairs, and staff.

For decades, co-ops appealed to the rich and/or famous, because there was no deed for their purchase and therefore no public record of what they’d paid. (The law changed, making co-op purchases public, in 2004.) Most of all, co-ops allow exclusivity because potential residents are screened both financially and in person by members of the board before they are approved. Although it’s never been proven, elite co-ops were always known to reject people—and a few are still said to—on the basis of race and religion. After all, a buyer can be turned down for any reason, without explanation. An ugly necktie at the interview is reason enough, although most turndowns relate to money.

As for the first co-op, the architectural historian Christopher Gray has made a strong case for the Rembrandt, erected in 1881 at 152 West 57th Street next to the Carnegie Hall site. Although the Rembrandt’s corporation failed—the building went rental within its first twenty years—others followed, and the idea boomed again in the 1920s and crashed during the Depression.

A few buildings turned to co-op ownership in the postwar decades. The residents of the Dakota Apartments, arguably the most famous luxury apartment house in New York, adopted co-op ownership in 1961, shortly after the building was sold and the new owner hinted that he might tear it down. But the real momentum for the co-op movement began in the 1970s, under a unique set of circumstances. Oil prices (and thus operating costs) had risen, while regulated rents (set by the city) had not. Landlords wanted out, and residents wanted control over their homes. Tax laws also slightly favored the co-op. Between 1978 and 1988, more than 3,000 rental buildings converted to cooperative ownership. Today, that fervor has faded slightly, as most new buildings are constructed as condominiums instead. But co-ops remain, and will continue to be, a huge piece of the New York market, numbering about 380,000 apartments in 7,200 buildings.

Although French artists had been using Conté crayons for a century, credit for the schoolchild’s brightly colored wax drawing tool belongs to Crayola. Its founders, Joseph and Edwin Binney and C. Harold Smith, set up shop in New York City in 1880, building on the Binneys’ earlier business making black pigments upstate. At first, the company made slate drawing pencils; in 1903, responding to schools’ need for inexpensive wax crayons, it introduced the first pack of eight Crayola colors, manufacturing them in its plant in Pennsylvania. The big sixty-four-crayon box with built-in sharpener arrived in 1958. Since 1984, the company (now called Crayola LLC) has been a subsidiary of Hallmark Cards, and it still makes its crayons in Pennsylvania. Edwin Binney’s wife, Alice, is credited with the name, a portmanteau of craie (French for “chalk”) and oleaginous.

Soft, spreadable cheese of the general type known as Neufchâtel has been made on farms and in homes for centuries. The conversion of that locally variable product into a branded, commercially produced commodity can be attributed to two men: William Lawrence, who’d begun mass-producing a version with a higher fat content in Chester, New York, around 1877, and Alvah L. Reynolds, who in 1880 began selling it to retail grocers downstate in the city. That same year, Reynolds was also the one who began wrapping it in foil stamped with a name in blue ink: PHILADELPHIA, capitalizing on that city’s reputation for high-quality dairy products. (There are many other myths about the creation of the brand, some of which involve the dairy-producing town of Philadelphia, New York, but the world’s most authoritative cream-cheese scholar, a rabbi in Santa Monica named Jeffrey Marx, has pinned this down pretty definitively.) By the end of 1880, Reynolds was selling more than Lawrence could produce, and his company soon expanded. He sold the brand in 1903 to a firm that later merged with the already successful Kraft cheese company, a chain of ownership that leads, most likely, to your morning bagel’s shmear.

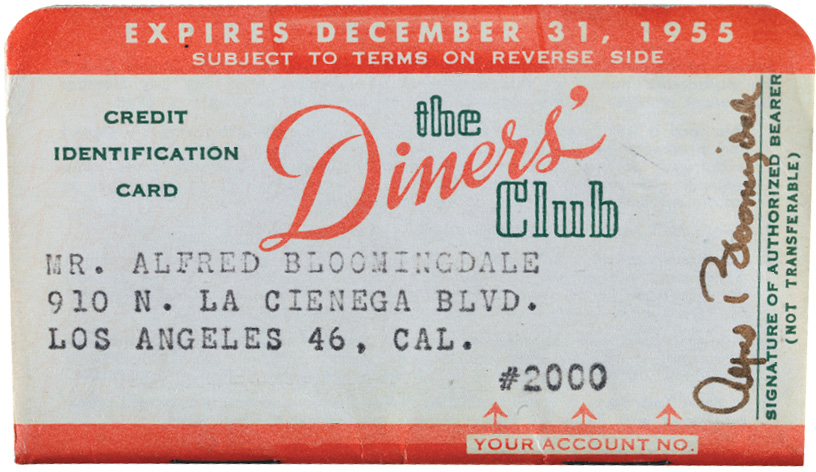

In the first half of the twentieth century, a variety of businesses, from department stores to oil companies, allowed consumers to charge purchases to their standing accounts. Over the decades, they added features to those programs that included minimum monthly payments and finance charges. In 1936, the growing airline industry created a credit system called the Universal Air Travel Plan, which was more or less a cross-industry charge account. Some of these systems depended on taking impressions from embossed metal address cards called Charga-Plates.

The real innovation came in 1949, when three men—Alfred Bloomingdale, Francis X. McNamara, and Ralph Schneider—were having lunch at Majors Cabin Grill, a restaurant at 33 West 33rd Street, next to the Empire State Building. McNamara ran a finance company called Hamilton Credit Corporation, which was on the verge of going broke because of its uncollected bills, and Schneider was his lawyer; Bloomingdale, a theater producer, was a member of the department-store family. Because McNamara’s company was in such precarious shape, the men began to discuss the ways businesses could extend credit, and over the course of the lunch they realized that restaurants could share a charge system, with a third party between business and consumer handling the operation. They called over Major Satz, the restaurant’s owner, and asked him what percentage he’d pay for such a system. “Seven percent,” he said, off the top of his head. McNamara and Schneider launched Diners Club shortly thereafter, with some initial funding from Bloomingdale, and in the early years they did indeed charge businesses 7 percent on each transaction. A year after that first lunch, McNamara went back to Majors and charged the very first meal on the first card, No. 1000.

After a brief, shaky start during which the founders had trouble finding a bank to back them, the company began to turn a profit in 1952 and within a few years went public and expanded from restaurants to hotels, retail stores, and other businesses. In 1958, it gained competition in a still-growing field from American Express, whose early cards were purple rather than today’s familiar green, and BankAmericard (now Visa). Diners Club, owned by Discover, is still around today, albeit as a relatively small part of the credit-card universe.

The co-founder’s own card.

Before its infamous role in the 2008 global financial crisis, the credit default swap (CDS) was conceived as a way to make banking less risky. In 1994, JPMorgan bankers in New York faced a problem: Their major client, Exxon, required a multibillion-dollar line of credit to prepare for a potential fine related to the Valdez oil spill. Because Exxon had excellent credit, the bank would make little money extending the line of credit and would be forced to tie up a lot of capital in reserves to back up such a large loan.

Eventually, a young JPMorgan banker named Blythe Masters and her colleagues came up with a solution: a swap, wherein the bank would make the loan but another financial institution (in this instance, the European Bank for Reconstruction and Development) would agree to bear the default risk. If Exxon failed to repay—a very unlikely circumstance—the EBRD would make JPMorgan whole for its loss. JPMorgan therefore did not need to hold extensive reserves to back the loan and could use its capital for more profitable business.

This was a novel application of an existing financial concept. Derivative contracts had long been used to simulate real-world financial events and hedge real-world financial risks. You could buy an interest-rate swap or an exchange-rate swap that would protect your business from exposure to unexpected changes in the financial environment. Now it was possible to buy a derivative that moved credit risk itself from one institution to another. And after JPMorgan created this bespoke product to help with its big loan to Exxon, it and other banks expanded and commoditized the concept, selling credit default swaps in a wide variety of contexts to many users beyond just banks.

It’s possible to see how these would make the system safer rather than less so. Banks are at risk when they have excessively concentrated exposure to specific clients, regions, or industries that can get into trouble. Products that help banks spread those risks more widely and offload risks that are excessive could, in theory, make the financial system more stable and resilient. But there were still problems. One was the rise of the so-called naked CDS, a credit default swap bought by speculators who didn’t actually have credit exposure to the entity whose credit was being insured. This created perverse incentives in bankruptcies; a CDS holder could actually stand to make money if the insured entity failed to pay its debts, which runs against usual principles that prohibit overinsurance. In other words, you don’t let people buy property insurance on other people’s houses, lest they be incentivized to burn them down.

Another problem is that while CDS shifts credit risk, it doesn’t make it go away and may even cause it to become less visible. This problem played a significant part in exacerbating the 2008 financial crisis. The major insurer American International Group had sold credit default swaps against $78 billion worth of collateralized debt obligations, effectively insuring its counterparties against the risk that there would be extensive defaults in various kinds of loans, especially residential and commercial mortgages. Then, when real-estate prices fell sharply, AIG’s ability to make all the payments it would owe to cover defaulted loans came into question. Ultimately, the federal government had to bail out AIG.

CDS does play a useful role in the financial system when applied appropriately, and bank regulators around the world have taken steps to preserve helpful uses of the CDS while cracking down on its abuses. U.S. banks are no longer allowed to speculate in a CDS with their depositors’ money, for example, and a CDS is increasingly required to be traded through public clearinghouses. Increased financial supervision of nonbank entities like AIG is supposed to protect against a variety of risks, including those related to CDS. But it remains uncertain whether these reforms will be effective in reducing our economic exposure to future financial crises.

Manifest Destiny, meet the real-estate bubble: In 1837, after years of offering low rates on Western lands taken from Native peoples, banks in New York raised interest and cut back on lending, prompting a bad recession. Between 1839 and 1843, over 40 percent of American banks tanked, unemployment hit double digits, and the economy took seven years to recover.

A partial solution to that volatility came from Lewis Tappan, a Manhattan wholesaler and a Calvinist who hated the idea of credit and preferred, as in the Bible, to deal in cash. Tappan did have a history in credit, though, using loans in the 1830s to navigate around a boycott of him and his brother by southern dry-goods dealers angered by the Tappans’ staunch abolitionism. After the crash, the brothers determined that if credit was necessary for America’s expansion, they might as well be the ones to try to sanitize it of its unpredictability. In the summer of 1841, Lewis founded the Mercantile Agency using their contacts in the abolitionist movement to estimate the personal character and credit information of potential debtors. Naturally, the reports weren’t all that accurate in the South, where the Tappans’ anti-slavery mission excluded them from business.

But by 1844, the agency had almost 300 clients and quickly expanded into Boston, Philadelphia, and Baltimore. It also had quite the list of alumni: Abraham Lincoln, Ulysses S. Grant, Grover Cleveland, and William McKinley all served as correspondents determining the likelihood a debtor would default. Having determined that the freedom of slaves was a worthier cause than the accuracy of credit reports, Tappan retired from the Mercantile Agency in 1849 to serve as treasurer for the American Missionary Association, which he’d co-founded in 1846, to establish churches for freed slaves and help finance what eventually became the system of historically Black colleges and universities. And the Mercantile Agency eventually became Dun & Bradstreet, a New Jersey–based analysis firm with almost $2 billion in assets.

New York isn’t exactly a stranger to food phenomena, but these days the line between fad and phenom is a much harder one to cross. That’s why it’s amazing that the cronut, a cross between a filled doughnut and a croissant invented by French-born pastry chef Dominique Ansel, has managed to maintain its iconic status. It made its debut at his Soho bakery on May 10, 2013, heralded by Hugh Merwin on New York’s Grub Street blog in a post headlined “Introducing the Cronut, a Doughnut-Croissant Hybrid That May Very Well Change Your Life.” Every day thereafter for several years, the so-called Frankenpastry—deep-fried and cream filled, with its specific method of manufacture a trade secret until the publication of Ansel’s 2015 cookbook The Secret Recipes—attracted lines of New Yorkers and tourists alike that snaked down Spring Street and around the basketball court on the corner. Though the day’s cronuts no longer sell out by 9 a.m. or appear on Craigslist at a 700 percent markup, Ansel has maintained their novelty by changing the flavors monthly. Other bakers have since tried their own repurposings of croissant dough, including a croissant-muffin hybrid called a cruffin. Cronut clones (clonuts?) can be found everywhere now, even at Dunkin’.

The cronut from Dominique Ansel Bakery.

8 The Best Time to Get a Cronut

From Dominique Ansel, baker

“We make several hundred Cronut pastries fresh each morning, and guests can purchase two per person in store. We recommend guests arrive in the morning (we open at 8 a.m. Monday through Saturday, and 9 a.m. on Sunday) as we typically sell out by late morning or early afternoon. Usually, if you visit in the morning close to the opening, you’ll be able to get them.

“There’s also an online preorder system so you don’t have to wait in line: Each Monday at 11 a.m., we release preorders at cronutpreorder.com for orders two weeks out. You can preorder up to twelve Cronut pastries per person.”

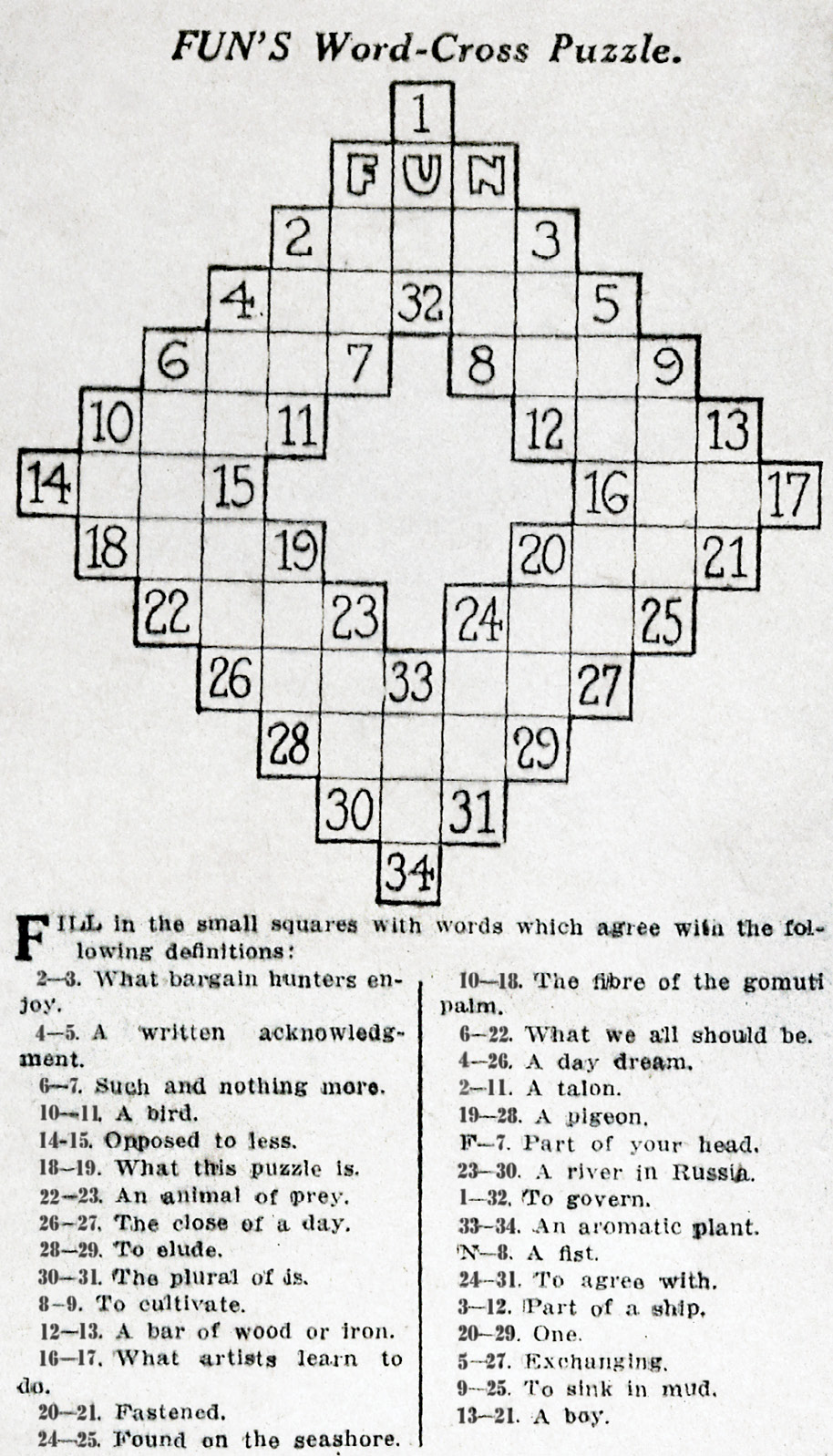

The big bang of across-and-down happened in the New York World, Joseph Pulitzer’s paper, on December 21, 1913 (a Sunday, of course). Arthur Wynne was the newspaperman who devised the grid you see here, with “FUN” at its apex. Over the next few years, puzzle solving became a bona fide fad among young people, right up there with flagpole sitting and goldfish swallowing. In 1924, to capitalize on the craze, Richard Simon and Max Lincoln Schuster launched their namesake publishing firm with the best-selling Cross Word Puzzle Book, which came with a pencil attached to the cover. (Still publishing that series, S&S is now up to Crossword Puzzle Book No. 257.) The New York Times got into the game in 1942, hiring Margaret Farrar—who had edited many of the S&S books—as its first puzzle editor. Her successor Will Shortz, only the fourth person to hold the job, also runs the world’s premier gathering of solvers, the annual American Crossword Puzzle Tournament.

The “Fun” supplement of the Sunday New York World on December 21, 1913, included the first crossword puzzle. (Solution on page 349.)