One of DDB’s breakthrough ads for Volkswagen, 1960.

The thing about a parade is, if you’re not in the front row at the curb, you can’t see the marchers. Unless, of course, they are oversize and elevated high above the street. That was the breakthrough idea, in 1928, of Tony Sarg, a designer and illustrator widely known for his puppeteering. Macy’s had inaugurated its Thanksgiving Day parade four years earlier, intending it to kick off the holiday shopping season. At the start, its signature displays were caged zoo animals, which brought with them all sorts of problems (they scared small children, for one). Sarg’s idea was to replace them with enormous balloons filled with helium, the extremely lightweight gas that had fairly recently started to be produced in quantity. They were controlled, like upside-down marionettes, by operators holding ropes. At first, they represented generic characters, elephants and birds and such; five characters from the Katzenjammer Kids newspaper comic strip and then Felix the Cat, a couple of years later, were the earliest branded balloons. (Mickey Mouse joined in 1934.) After the parade, they were released and allowed to float away and could be returned to Macy’s for a reward once they returned to earth. Starting in 1931, Newark’s main department store, Bamberger’s—which Macy’s owned—launched a Thanksgiving Day parade with balloons of its own. That lasted until 1957.

Nearly a century later, Bamberger’s is gone, but Macy’s endures and the balloons have become an even bigger part of the show. There are roughly twenty of them each year, their presence paid for out of the promotion budgets of animation companies and brand strategists, their backstories narrated on NBC by the punny Al Roker and crew. They have not always been benign: In 1997, when high winds pulled several balloons off course, the Cat in the Hat snagged and knocked over a lamppost, injuring four spectators, one almost fatally. In 2019, when the day was once again windy, the balloons were nearly grounded, but the parade marched on—as does the bizarre habit, in surprisingly widespread use among New Yorkers (listen for it), of calling the event “the Macy’s Day parade.”

Toward the end of the nineteenth century and into the twentieth, advertising moved from being a local, straightforward endeavor to a business that was professionalized, wily, and increasingly informed by the emerging science of human psychology. Early megacorporations (General Motors, Coca-Cola, Standard Oil) needed to sell products and establish their brands, so they engaged outside help—the newish innovation known as the advertising agency. Those early firms were initially scattered around the country, but eventually most of the business coalesced in Chicago and New York. The pioneering J. Walter Thompson agency, the first to have its own creative department and later the first to conduct market-research surveys, got its start in 1878, operating from the old New York Times building on Park Row. A few years later, the George Batten Company, progenitor of BBDO, opened on the same block.

With the rise of mass communications—first magazines, then radio and television—and their concentration in New York, the ad business flourished in the city and soon began to migrate uptown, and particularly to Madison Avenue. In 1917, J. Walter Thompson moved to 244 Madison, becoming one of the first agencies with an address on the avenue; Young & Rubicam followed a few years later. By 1930, one-quarter of the American Association of Advertising Agencies’ members were based on Madison Avenue, and the eponym began to come into wide use.

The Great Depression and the Second World War were inherently tough on the ad business, based as it is on spending, especially disposable-income spending. After the war, however, that changed in a hurry as American consumerism took off. Advertising fed the beast, and the field itself was invigorated during this period, now known as the creative revolution. Whereas earlier advertising had tended to sell a product itself rather than the lifestyle that goes with it (and it was rarely funny), as the world got more dense with branding messages, ad-makers needed new tools to cut through the noise. The breakthrough talent was Bill Bernbach, a principal in the firm Doyle Dane Bernbach. (It existed in contradistinction to its rival, David Ogilvy’s agency, which was founded on the principle that hard data should do the bulk of an ad’s work.) In 1949, DDB’s ads for its first client, Orbach’s department store, created a minor sensation by using an image of a man leaving the store carrying a cardboard cutout of his newly dressed-up wife under the tagline “Liberal Trade-in.” (Creative, perhaps; sexist, unquestionably.)

One of DDB’s breakthrough ads for Volkswagen, 1960.

The real turning point, though, came with ads for DDB’s most famous client: Volkswagen. The Beetle was an ugly-duckling car from a nation that, only a few years earlier, had been the mortal enemy of civilization. (Adolf Hitler himself had specified the design of a durable little “people’s car” that could be built and run inexpensively.) Starting in the late 1950s, DDB’s Bob Gage, Helmut Krone, and Julian Koenig created almost from scratch an entirely new image for the Volkswagen: that it was a car for thinking consumers, that its unchanging profile was a not a bug (so to speak) but a feature because it didn’t go out of date, that its value lay in its durability and practicality. The ads themselves were clever and spare, with lots of white space and simple black-and-white photographs; the most famous one showed a Beetle over the single boldface word Lemon. Never in a million years would General Motors have allowed that word, describing an unreliable junker, near a Chevrolet ad. (A bit of copy underneath explained that VW in the photo had come off the assembly line with a blemish on the glove compartment and thus could not be sold, emphasizing the company’s quality-control operation.) DDB rolled the dice and created an icon. Increasingly, the image of the sellout ad man, bound to his drab client’s wishes, his gray flannel suit, and his two cocktails on the 5:05 back to Larchmont, was giving way to a more flamboyant figure.

This kind of lively thinking turned DDB into the “hot shop” of its time, and its approach began to proliferate. Over the next couple of decades, one of the agency’s alumni, the flamboyant and high-profile art director George Lois, created taglines like “When You Got It—Flaunt It” (for Braniff International airlines) and “I Want My MTV.” Pepsi-Cola tried to differentiate itself as a youthful alternative to Coca-Cola (“For those who think young”), and Coke eventually countered with the legendary “I’d Like to Teach the World to Sing” television spot. Mary Wells Lawrence, of Wells Rich Greene, created “I can’t believe I ate the whole thing” and “Plop plop fizz fizz” for Alka-Seltzer. TBWA’s Absolut Vodka campaign took a nearly tasteless product sold in a nondescript bottle and turned it into a totem of upscale life, while Apple Computer’s 1984-inspired ads with Chiat\Day successfully pitted a small start-up against giant IBM. But although DDB was based at 350 Madison, the term Madison Avenue was beginning to reflect the past rather than the future. More and more agencies were almost perversely taking offices elsewhere as if to duck the cliché. In the 1970s, they started looking eastward to Lexington (where J. Walter Thompson had long since resettled) and Third Avenues.

Advertising’s creative revolution never exactly ended. Like many successful rebellions, it simply ceased to be revolutionary as it took over the mainstream. The outlaw quality of the 1960s ad business couldn’t be sustained forever; agencies can do this kind of outré work only when the client accepts it on faith, fearlessly, and today, most clients are more controlling and not so inclined to just say yes. Doyle Dane Bernbach (now DDB Worldwide) has been rolled up into a conglomerate with the self-parodying name Omnicom, one of the last few big agencies with an actual Madison Avenue address. (After 87 years, Young & Rubicam moved across town to Columbus Circle in 2013.) And anyway, the entire ad business has had to contend with a wild new change with the rise of the internet: Actual data that show whether ads are seen, who’s seeing them, and whether they pay any attention at all. The biggest ad agency in the world is, pretty much, Google.

The story of the industry’s golden age is now mostly encapsulated in the shorthand “Mad men,” referring to Matthew Weiner’s TV series set at a fictional agency quite a bit like Bill Bernbach’s. Many of the old real-life Mad men disdain it: They say Don Draper’s pitches aren’t nearly as good as the real thing and there wasn’t as much drinking and sex in the agencies of their time. Image supersedes reality once again.

Sidney Rosenthal, a tinkerer-inventor working in Richmond Hill, Queens, is responsible for those squiggles on your office whiteboard. In 1952, he figured out how to feed a wide felt wick from a glass vial of ink. (Earlier patents for felt-tip pens exist, one dating to 1910, but they were not effectively commercialized.) Rosenthal called his handiwork a Magic Marker, and his company, Speedry Chemical Products, soon had a hit on its hands, among warehouse workers, artists, kids, and anyone who wanted to write on anything besides paper. By 1958, a competitor, Carter, had introduced its similar Marks-a-Lot line, provoking some legal tussles between the two; in 1966, Rosenthal sold Speedry, and the company itself was renamed Magic Marker Corporation. Today the trademark is owned by Binney & Smith, the Crayola people (see also CRAYON).

In 1910, Elizabeth Arden, a Canadian expat born Florence Nightingale Graham, opened her first salon on Fifth Avenue, its door painted red “so everyone would know where to find us.” From her menu of treatments that promised self-improvement, her well-to-do guests could choose to be pummeled and rolled, creamed and steamed, rouged and coiffed. By the end of its second decade in business, the Red Door housed a Department of Exercise, through which women could engage in a low-impact regimen of stretching and rhythmic movements, and after Arden moved up the street to a new location, the salon included a full gymnasium. Patrons may have walked in looking drab, but they walked out reborn a few hours later. However transitory, the change instilled hope and newfound confidence—and the idea of the makeover was born. The concept and catchy name gained significant attention when Mademoiselle magazine published a feature on this metamorphosis in 1936.

A nurse named Barbara Phillips read the story, in which the New York makeup artist Eddie Senz took readers through the techniques he performed on actresses, encouraging readers to follow along. Phillips had her own ideas, and wrote to Mademoiselle (saying “I am as homely as a hedgehog”) with the suggestion of performing these changes on a noncelebrity, namely herself. In the November 1936 issue, she was featured as the magazine’s first-ever makeover. They removed her glasses, capped her teeth, covered her hair with a wig, and put her in a ball gown. This second feature was an even bigger smash than the first, so much so that it was covered in Time, and the gown she wore was duplicated and marketed nationally as “the Cinderella Dress.”

Senz got a recurring column out of that feature, showing his “befores” and “afters” with their various shortcomings ameliorated, and the Mademoiselle Makeover became a contest, for which women would send photographs of themselves looking as unattractive as possible in order to be chosen. By the ’60s, the magazine’s team of editors and experts would travel the country, making over teachers, nurses, and students, eventually including the series as part of its annual “College” issue. Glamour soon followed with its monthly “Please Make Me Over” page, as did Allure in 1991, when editor Linda Wells wisely hired makeup artist Kevyn Aucoin, known for his transformative prowess. In the late ’90s, Jane magazine included a regular “Makeunder” page, turning the concept on its head with the belief that too much was, in fact, just that, neutralizing the makeup, and subduing the big hair.

The makeover continues, of course, to be offered in full-service salons, in magazines, on reality TV, and on YouTube and other websites, in which women creatively make over themselves. The promise of a “new you,” and all the implications associated with a haircut and a professional makeup application, is a dream that doesn’t appear to be dying anytime soon.

1 A Beauty Editor’s Favorite Facials in New York

Chosen by Kathleen Hou, the Cut’s beauty director

FOR A BEGINNER FACIAL

FOR A BEGINNER FACIAL

Heyday: “It’s not supremely fancy, and the rooms are divided by curtains. But the aestheticians still do good extractions, and you’ll leave with a soft glow.”

FOR A MEDIUM FACIAL

FOR A MEDIUM FACIAL

Rescue Spa: “If you’ve ever wondered about the mysterious ‘Jesus in a Bottle’ (Biologique Recherche’s Lotion P50), they sell all seven types here and can tell you how to use it. And the tea is Mariage Frères.”

FOR A LUXURY FACIAL

FOR A LUXURY FACIAL

Joanna Vargas or Georgia Louise: “They are the busiest facialists in town the week before the Met Gala.”

Take two parts rye or bourbon (purists would use the former), one of sweet vermouth, and a dash of bitters; add ice, stir till the drink is chilled and slightly diluted, strain into a glass, drop in a cherry, and then down the hatch. The booze historian Philip Greene argues persuasively that the Manhattan was the first modern cocktail—that is, one not derived from a punch, neither too sweet nor too straight up, and possessing both balance and flavor complexity. Endless arguments have been fought over the precise site and date of its creation, but the case best borne out by historical sources says it was invented by a bartender at the Manhattan Club, at 96 Fifth Avenue, near 15th Street, in the 1870s. The first known references appear in newspapers from 1882. (A widely repeated and probably spurious story holds that the drink was invented for a banquet given by a socialite named Jennie Jerome—a.k.a. Lady Randolph Churchill, Winston Churchill’s mother.) The Manhattan is now a staple of craft-cocktail menus, made with a high-quality rye and garnished with a premium Luxardo preserved cherry.

Until the twentieth century, women who were pregnant dressed however they could, making or ordering loose-fitting shifts and wraps and staying out of public view when possible. In 1904, a Lithuanian immigrant, Lena Himmelstein Bryant, began selling belly-accommodating clothing out of her shop at 1489 Fifth Avenue, near 120th Street. A misspelling on her application for a business loan turned Lena into Lane (simultaneously making her name more Gentile-sounding), and Lane Bryant was thereafter the name of her business. Her unique product line spread via word of mouth, aided by ads bearing the legend “The Kind of Garment You Never See in a Department Store.” By 1910, Lane Bryant was operating just off Fifth Avenue in the Garment District (see also SEVENTH AVENUE), at 19 West 38th Street.

Bryant’s firm eventually moved beyond maternity wear into another formerly invisible market: clothes for women described today as plus-size and back then as “stout.” That turned out to be another lucrative move, which gradually superseded the maternity-clothing lines. By 1917, Lane Bryant was a million-dollar business; by 1923, $5 million. Today, it’s a chain of 700 stores and the biggest plus-size retailer in the world.

New York City started—or so goes the legend—as a con game. In 1626, a Dutchman from Utrecht named Peter Minuit stood on a rock and bought Manhattan Island for goods worth 60 guilders, or $24. The cash went to the chief of the Canarsie tribe, whose principal residence was on Long Island; Manhattan then was mostly Weckquaesgeek territory. The Dutch thought they’d snookered the Indians out of their land, and the Canarsies accepted payment for use of an island to which they didn’t really have a claim. In short, New York City is the product of a business exchange in which each side thought it had hoodwinked the other. This explains a lot.

America is, at its root, a violent and debaucherous country. The westward push of Europeans and the displacement of indigenous people were often brutal, predicated on rape and murder. By the 1630s, the pirate and privateer Abraham Blauvelt had established New Amsterdam as his base of operations. A quarter of the city’s buildings were taverns, breweries, or other sources of alcohol, and, this being a seaport with transient sailor populations, prostitution was everywhere. The author Russell Shorto describes a casual encounter between a trio of armed farmers and a local sentry that escalated (after one of the former insulted the latter with the command “Lick my ass”) and ended in a stabbing and a court date. “Clearly,” he wrote, “the New Netherland settlers were quite unlike their fellow pioneers to the north, the pious English Pilgrims and the Puritans… governed by godly morality.” New Amsterdam’s records are filled with accounts of sexual transgression and public intoxication.

This didn’t change after the English came in and the city started to grow uptown, although the bad behavior did begin to coalesce, somewhat, into certain districts. The most notorious, developing in the early nineteenth century, was known as the Five Points. It began alongside a nice little lake called the Collect Pond, sitting next to an intersection of five city streets that gave the area its name. The pond had attracted industry and become foul with sewage, and in 1811 it was filled in and eliminated. Soon the fill began to sink and the pond’s stink reemerged, whereupon the surrounding neighborhood lost its respectable residents, becoming the worst slum in New York. Its denizens, jammed in tightly, were principally Irish immigrants, with some African-American former slaves among them as well. Street gangs and machine politicians—you can see Martin Scorsese’s depiction of them in Gangs of New York—took over for decades. In one visit, you could place bets, buy sex, get conned in a faro game, and be rolled for your money after it was all over.

The city eventually condemned Five Points, erasing it from the map—it now lies more or less under the courthouses at Foley Square—but that was hardly the end of the behaviors that categorized it. As the Irish immigrant population that constituted a lot of poor New York began to assimilate and leave its enclave neighborhoods, other street gangs, often also based in ethnic allegiances, stepped up in their place. (On the Lower East Side, broadly speaking, the Bowery divided them: Italians to the west, Jews to the east. Comparable divisions took hold uptown and in Brooklyn.) The loose gangs of the nineteenth century gave way to somewhat more structured ones in the twentieth—first the Italian Black Hand and eventually the Five Families of the Mafia (see also MOB, THE) and the killing-for-hire operation known as Murder, Incorporated, cemented in pop culture by the rum-running operations of Prohibition.

The rise of organized crime didn’t necessarily make the neighborhoods where it operated more dangerous than they already were. There were killings, and there was a certain level of run-of-the-mill street crime present because the population was mostly poor. But if you were an ordinary resident of the Lower East Side and you played by the local rules, staying on your turf and avoiding conflict—or if you were a shopkeeper and paid protection money, either to the racketeers or a crooked cop—you were perhaps as safe as anyone. The gangsters, in fact, functioned as a shadow police force. Even in the Depression, then again during wartime, crime rates in New York were as low as they’d been since measuring began.

That stasis began to crack in the 1950s, when headlines about “juvenile delinquency” began to appear. The triple forces of job loss to other states, emigration to the suburbs, and general shifts in family structure, accelerated by the rise of hard drug use, began to have a noticeable impact. Unlike the gangsterism of the 1930s, which could in a perverse way be romanticized—gun molls, honor killings, Guys and Dolls craps games and tough-guy patois—this wave included old people’s being clubbed for their grocery money, and there was nothing remotely charming about that. “We confront an urban wilderness more formidable and resistant and in some ways more frightening than the wilderness faced by the pilgrims or the pioneers,” Robert Kennedy said in 1966. As the city’s population thinned out, the murder rate rose, and rose again. In 1950, there were 294 murders in the five boroughs. In 1960, there were 482. In 1970, the total reached 1,117. In 1980, it hit 1,814.

By then, many people felt the city was in free fall. Middle-class swaths of the Bronx, Brooklyn, and the Lower East Side were depleted, leaving buildings unrentable, abandoned by their owners to avoid property taxes, and left to burn or rot. The families remaining in those areas were the poorest poor, often Black and Hispanic, people who had to get by with whatever everyone else had left behind. Drugs saturated the neighborhoods, putting a generation of young people at high risk. Their relationships with police (mostly white and decreasingly local) were sometimes helpful but more often toxic. “The South Bronx” became widespread shorthand for an urban place where you could, in the popular imagination, get shot just for stepping out of your door, a new Wild West that marked the end of civilization. Movies were made about it, one of which (set in a police precinct) was called Fort Apache, the Bronx. The perception of total urban collapse was both driven by racism and a little overblown but also dispiritingly accurate. The citywide blackout in 1977 led to patches of looting and the perception of much more. During the 1977 World Series, Howard Cosell saw a plume of smoke near Yankee Stadium and announced, “There it is, ladies and gentlemen, the Bronx is burning” to a national audience. The image stuck.

Life for middle-class urbanites was better but still not great. Mugging—a street robbery, by threat of force or with a knife or gun—became the quintessential shared New York experience. Even in well-off, pleasant neighborhoods, people avoided walking at night, and Central Park was considered a risky place after dusk. Women walking on midtown sidewalks in broad daylight knew to wear their purses slung across the body rather than on one shoulder, lest they be grabbed. Men avoided keeping a wallet in a back pants pocket. If you dozed on the subway, you might awaken to a razor-sliced hole in your coat and your money gone. Chain snatchings, in which someone would grab your necklace, snap it, and run, were rampant. When the MetroCard was introduced to replace the transit token in 1993, many people’s first reaction was “It’s dangerous to take out a wallet in the subway.” An abandoned, ruined automobile was a commonplace sight on a Manhattan street, and a graveyard of stripped stolen-car carcasses formed on the bank of the East River near the Brooklyn Bridge. In 1990, the murder count peaked at 2,245 people.

And then something changed. Already, aggressive federal prosecution under new racketeering regulations had begun to break the grip of the mob on various businesses, and its influence was waning. But some combination of a newfound job base in the dramatic growth of financial services, increasing wealth, more effective crime-fighting techniques, and other cultural shifts (see also “BROKEN WINDOWS” POLICING) caused the numbers to turn. Between 1990 and 2010, the murder tally fell from 2,245 to 534, a 76 percent drop. Comparable changes took place in every other violent-crime category: robbery, burglary, rape, assault. Most other American cities saw their numbers decrease over the same period, but nowhere else was it nearly as dramatic. And incredibly, that was not the end. By 2018, it had nearly been halved again, to 289. The place whose very identity was “only the toughest survive” had become the safest big city in America.

Which did not mean disorder was gone, of course. The new ironed-smooth New York began to curl up and crinkle at the edges as you went out into the boroughs. The South Bronx was better than before, yes, but it was still a hard place to live. The city’s de facto segregation between Black and white did not get much better. And that divide, one of class as well as race, became broader rather than narrower; public schools and parks in affluent neighborhoods got financial buttressing from their well-off users, who could supplement their budgets and volunteer help, whereas those in poorer neighborhoods were left behind, unrenovated and decaying. Perhaps this was a stage on the road to fixing New York’s ills, but more likely it reflected the intractability of the growing rich-and-poor gap. One might also say that it proves New York to be not entirely domesticable, no matter how many brownstones that had fallen into ruin are re-renovated into luxury single-family homes. Quite a few young people—those who weren’t here in the 1970s—speak fondly of the bad years, wishing they could spend time there, when apartments were cheaper and the city (as they perceive it) felt more “authentic” and “dangerous.” A striking number of old-timers agree with them.

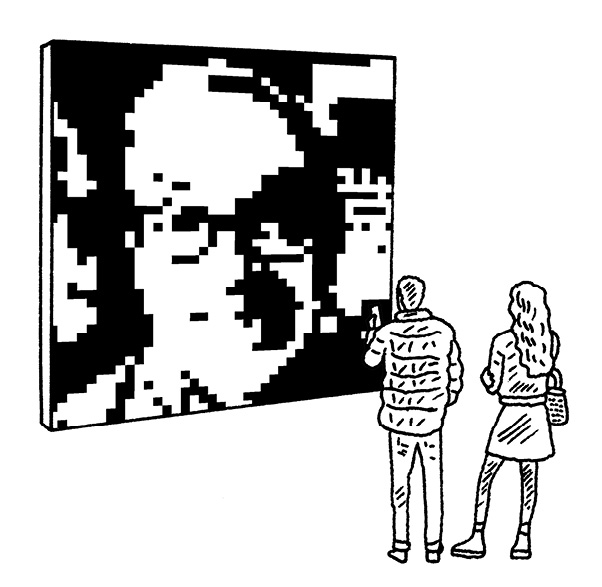

With its massive concentration of wealth, New York City has provided fertile ground for the rise of the supersize art dealer—known to art-worlders by just one name (Larry, David, Marian) and for turning their mom-and-pop shops into globe-spanning operations. And though many top dealers have raced to open multiple locations worldwide, even those who didn’t start in New York soon moved to Gotham or set up an outpost here.

This development began after World War II, when New Yorkers such as Leo Castelli and Betty Parsons moved from their predecessors’ modus operandi of dealing mainly in individual artworks to exclusively representing a stable of artists so the dealer’s investment could bear fruit for both. This was not without precedent: French dealer Paul Durand-Ruel, who worked with the Impressionists, put artists on stipends and aimed to represent them exclusively. (He also opened a gallery in New York after the Civil War, exploiting postwar industrial wealth and the new concept of art as an investment asset.)

The king of the megadealers may be the self-made Larry Gagosian, who opened his first gallery in West Hollywood in 1978 and landed in a former truck dock in Chelsea, then an ungentrified warehouse neighborhood, in 1985. Gagosian also blazed a trail by taking a more mercenary approach. He was among the first to make a killing in the hypercharged 1980s market by showing rising artists like David Salle and Jean-Michel Basquiat and facilitating multimillion-dollar deals on brand-name modern and contemporary artists between the world’s wealthiest collectors.

Castelli was Gagosian’s mentor and introduced him to deep-pocketed clients including Condé Nast owner S. I. Newhouse. He early on cultivated major collectors like the entertainment magnate David Geffen, the cosmetics heirs Ronald and Leonard Lauder, and the newsprint millionaire Peter Brant, enabling him to pull off exhibitions of works from major private collections and museums both. In the ’90s, he lured the notoriously perfectionist (and pricey) artist Jeff Koons to work with him by finding backing for his sculptural series “Celebration,” kicking off a long-standing relationship. Today Gagosian has eighteen galleries, five in Manhattan. In 2016, The Wall Street Journal estimated his annual revenue at $1 billion.

Gagosian’s rarefied competitors include the Pace gallery, which migrated to 57th Street from Boston in 1963 and now has ten locations and about $900 million in annual revenue, and David Zwirner, who opened his seventh location in 2020 (four are in Manhattan, where he got his start in Soho in 1993) and whose annual revenue in 2017 was estimated at a half-billion dollars. Some of the most renowned dealers operate from fewer venues but have the allegiance of artists who dominate both the market and critical discourse. Painter Gerhard Richter, among the best-selling artists alive, has remained for years with Marian Goodman, who set up shop in her native New York in 1977 and also represents major figures like Maurizio Cattelan and the filmmaker-artist Steve McQueen. As her peers set up outposts all over the globe, Goodman was content to operate solely from midtown until 1995, when she expanded to Paris (and to London in 2014). But not everything about the rise of these New York giants is beneficial. Small and midsize galleries—including some in New York pummeled by the rising costs of real estate and those anywhere who lose their best sellers to the megadealers—have gone to work for the titans or thrown in the towel entirely, robbing the market of a key element in the art world’s ecosystem. Their departure from the business often leaves non-superstar, modestly successful artists, particularly those who are no longer young, with nowhere to show.

2 Walk the Giant Chelsea Galleries

From New York art critic Jerry Saltz

“Larry Gagosian has one massive space anchoring 24th Street and another on 21st Street. Pace Gallery built an entire building on 25th Street and is always open for business. (The Who played opening night!) Hauser & Wirth has dozens of locations, including a gigantic warehouselike building on 22nd Street. And nearby on 19th and 20th Streets is the ever-expanding gallery empire of David Zwirner. Visits to any of these will reward viewers with jaw-dropping amounts of wide-open space and works of famous artists, often including Picasso, Monet, Jeff Koons, Chuck Close, Jean-Michel Basquiat, and Julian Schnabel.

“Also don’t skip Matthew Marks’s three galleries; maybe you’ll see work by geniuses like Jasper Johns or Robert Gober. At Sikkema-Jenkins & Co., be on the lookout for the electrifying work of MacArthur-winning artist Kara Walker. For photography, never miss 303 Gallery, where the art form was rediscovered in the 1990s, and Metro Pictures Gallery, where the world-famous master of disguise Cindy Sherman has shown since the early 1980s. Finish the day with a walk along the High Line directly above and be treated to the greatest curated outdoor program in the United States, if not the world.”

Larry Gagosian, the mega-est megadealer of them all.

PHOTOGRAPH BY CHRISTOPHER STURMAN

On the earliest sound recordings, before the technology was electrified, a singing voice would emerge like a howl from inside a locked closet—muffled, desperate, and indistinct. The process favored the loudest blasts, so orchestras sounded like they consisted exclusively of trombones. The problem was that in an acoustic recording system, as sound waves hit a diaphragm attached to a conical horn, causing a stylus to cut grooves into a wax cylinder, the vibrations degraded at every step. What started out as a strong yet subtle signal wound up a scratchy mess.

That changed in 1916 thanks to Edward C. Wente, an engineer who worked for Western Electric at 463 West Street. (That building, a West Village hothouse of inventiveness, became Bell Laboratories in 1925 and was converted to an artists’ subsidized-housing complex in 1970 [see also WESTBETH ARTISTS COMMUNITY].) Wente came up with the condenser microphone, in which sound waves activate a lightweight metal membrane that flutters next to a metal plate. As the space between the two surfaces varies, the amount of stored electrical charge they carry—called capacitance—rises and falls. When that tiny electrical variation is amplified, even a quiet murmur can be preserved and transmitted without losing its lifelike quality. Speech sounds like speech, music like actual music.

The condenser mic was refined and developed for commercial use in the mid-1920s, and it revolutionized daily life on several fronts. The telephone, Wente’s original focus, became a household and office object now that the people on either end of the line could conduct conversations instead of shouting matches. The microphone’s acoustic precision also turned music into a mass medium with live performances broadcast on the radio and recorded ones distributed on disc. Wente complemented his microphone with two more inventions: the ribbon-light valve, which married sound to film, and a moving-coil speaker that made it possible to fill a large room with loud but accurate sound. Link these components—mic, valve, and speaker—together into one apparatus, and what you get is talkies. Without Wente on West Street, Emma Stone might still be miming oohs and aahs, à la Louise Brooks.

Minimalist music was born in California but grew up in New York. Its bright drones and polychrome pulsations saturated the culture of downtown Manhattan so completely that it’s impossible to imagine Soho in the ’70s without them.

Two composers can lay claim to having launched the movement: La Monte Young, whose 1958 string trio stretched out sustained notes so long that time seemed to go on vacation, and Terry Riley, who in 1964 combined endless repetition, slow buildup, improvisation, and unchanging harmony into the landmark piece In C. But minimalism acquired a distinctively New York accent in 1965, when Manhattan-born Steve Reich composed It’s Gonna Rain for magnetic tape, based on the twin concepts of looping and phasing. Reich recorded a street preacher’s sermon, made identical loops of one brief passage, and played them on different tape machines, which in those days unavoidably ran at slightly different speeds. As the loops slipped out of alignment, the musical snippet of speech acquired a weird, unpredictable quaver.

As these early experiments added up, it became clear that composers had developed new principles for assembling music’s basic ingredients; instead of story, contrast, passion, variety, climax, and conclusion, minimalists offered a cool, continuous unfurling. This demanded fresh ways of hearing. The experience, Reich wrote, was like “placing your feet in the sand by the ocean’s edge and watching, feeling, and listening to the waves gradually bury them.”

Reich’s main rival for the role of movement leader was his friend Philip Glass, a fellow cabdriver and downtown denizen. Realizing that the musical Establishment had no place for them in the 1960s, both men formed and trained ensembles that specialized in their styles. But the two veered in different directions. Reich sought structural purity and expressive clarity in works like Clapping Music and Drumming. Glass wrote Music in Twelve Parts, wrapping surfaces full of color, lushness, and sonic variety around a basic frame. When he composed the score for the nonnarrative opera Einstein on the Beach in 1975, he harnessed the language of artless simplicity to grand, complex spectacle.

Set off against the academic complexity of “uptown” music, minimalism first created its own counterculture, with concerts in Soho lofts and art galleries, then developed an international reach, infiltrated the Carnegie Hall and Lincoln Center Establishment, and spread to pop music, film, and car commercials. A lot of the music of the past 50 years depends on those long, long tones over a constant plunk-plunk-plunk-plunk. And the movement’s own story, much like one of Glass’s early works, goes on and on, mutating from an avant-garde into a stockpile of clichés and influencing post-minimalist generations. One strand led to the Velvet Underground, David Bowie, and Japanese techno, another to the busy, historically ambitious operas of John Adams, a third to the film scores of Hans Zimmer. Minimalism became maximized.

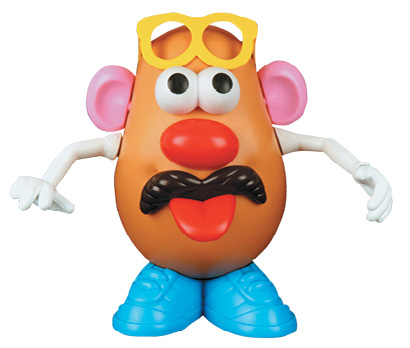

George Lerner, a Brooklyn toy inventor, was the man who put a face on a spud. His original Mr. Potato Head, drawn up in prototype in 1949, was not much like today’s. It called for an actual potato, and its plastic eyes, lips, ears, and tobacco pipe bore sharp spikes so they could be jabbed into place. The eyebrows and hair were made of felt and were intended to be pinned on. The face, at least by today’s toy standards, could be a little bit demonic looking.

There were reportedly misgivings in the immediate postwar years about the waste of food this product potentially entailed, but in 1951, a modestly sized Rhode Island toy company, Hassenfeld Brothers, bought the design and the next year began advertising the Mr. Potato Head Funny-Face Kit on TV in the world’s first toy commercial. (The slogan on the box: “Any Fruit or Vegetable Makes a Funny Face Man.”) In 1953 he was joined by a spouse, Mrs. Potato Head. A son, Spud, and a daughter, Yam, followed. The instructions on the British version of Mr. Potato Head suggested that, if pressed, one could also use a beetroot.

In 1964 Mr. Potato Head went all-plastic, shedding his dependence on an authentic tuber. (This was possibly a relief to the thousands of parents who had discovered rotting vegetables in their children’s bedrooms.) In this new form, he and the missus were successful enough that Hassenfeld introduced a whole line of their produce-aisle friends. Cooky the Cucumber, Pete the Pepper, Oscar the Orange, and Katie the Carrot each had slightly different, slightly disturbing facial features. So did various potato-complementing associates: Frenchy Fry, Mr. Ketchup Head and Mr. Mustard Head, Willy Burger, Frankie Frank. There was even a custom-branded Dunkie Donut-Head.

Over the years, Mr. Potato Head has seen his proportions change and his various accessories get larger to conform to government safety regulations, lost his pipe and become a spokespotato for smoking cessation at the behest of the U.S. surgeon general, and had a major role in the Toy Story movies. Lerner—who drew a royalty on every Mr. Potato Head sold—started his own toy company with a partner, Julius Ellman, and their firm, Lernell, is still in business, operated by Ellman’s sons under the name Giapetta’s Workshop. Hassenfeld Brothers also did okay. Its name was condensed to Hasbro (see also SCRABBLE), and it’s one of the largest toy-makers in the world.

One tends to think of the mob or the mafia as a catchall term for crime organizations, but the actual Mafia—founded in 1282 in Sicily—is merely one large group among many. The Camorra held power in Naples, the vorovskoi mir (“thieves’ world”) in Soviet Russia. Crooks in virtually every country have banded together for the sake of greater lawbreaking efficiency, often first as street gangs and then in more complex structures, especially in the past century or so. Given New York’s position as a nexus of immigrant cultures, it’s no surprise that a lot of those groups made their American landfall here. The Mafia itself got its first toehold in America in 1881, when a group of seven gangsters fled Sicily after one of them, Giuseppe Esposito, had murdered more than a dozen prominent local men. (Esposito, who settled in New York and then New Orleans, was eventually caught and sent back to Italy for trial.)

Around 1900, in New York’s Lower East Side and a few other ethnic enclaves—where loosely affiliated street gangs had already conducted their business for generations (see also MAYHEM)—a particular network of Italian immigrant criminals known as the Black Hand began to shake down local residents and merchants. It was more or less a protection racket (one whose methods you can see fictionalized in The Godfather Part II, where the white-suited character named Fanucci demands that Vito Corleone “wet my beak”). To combat the Black Hand, the New York City Police Department set up a task force led by Lieutenant Joseph Petrosino—who, on an evidence-gathering trip to Sicily in 1909, was murdered for his efforts. You can still see his name on Petrosino Square, at Kenmare and Lafayette Streets.

The shakeout between the Camorra and the Mafia in New York began in 1915, after the murder of Giosue Gallucci and his son led to an exchange of hits that left 23 members of both groups dead. By its end, the former (which was ever so slightly less brutal and thus at a competitive disadvantage) was basically defunct and was absorbed by the Mafia, which was then perfectly placed to take advantage of Prohibition, enacted in 1919. It was an ideal set of circumstances in which to form a shadow economy by providing a black-market product that people really wanted at a premium price without taxation. The old neighborhood gangs began to divide the turf and create territories, hastened by an intramural Mafia battle for control known as the Castellammarese War. A concurrent shakeout in Chicago led to the primacy of Al Capone’s gang.

By the 1930s, most American cities had a crime organization in charge of rum running, gambling, and various other mobbed-up businesses. New York, being much larger, spread that work among the Bonanno, Lucchese, Gambino, Profaci (a.k.a. Colombo), and Genovese organizations, the so-called Five Families, also known as the Commission. Charles “Lucky” Luciano, who established the Commission and ran the Genovese gang, oversaw its links with the enforcement organization known as Murder, Incorporated, the widely publicized contract-killing arm of the mob. This was not a Sicilian Mafia organization per se; it was mostly a Jewish group, headed by Louis “Lepke” Buchalter. (It was also affiliated with the hired killer Dutch Schultz until he threatened to go rogue in 1935 and the Commission had him shot dead.) Within various other New York communities, different organized-crime groups held power of their own: the tongs of Chinatown, for example.

Mayoral reform efforts—notably by Fiorello La Guardia—and state and federal prosecution were, at first, only modestly effective against all of this, for a variety of reasons. Even after Prohibition came to an end in 1933, there were plenty of businesses, including prostitution and gambling, in which the mob was providing services people wanted one way or another. Loan sharks, for better or worse, were there for those who couldn’t borrow from a bank. Your average New York precinct house was also pretty corrupt—street cops were often on the take, and local businesses were sometimes faced with a choice of paying off the police or the gangsters for protection. Sometimes the mobsters seemed like a more attractive bet. Mob influence also infiltrated the Democratic political machine and a variety of otherwise legal New York industries: trucking, the produce and fish markets, concrete production, commercial garbage collection, the nightclub business. Many gay bars were mob controlled, in part because the gangsters could keep the cops away for a price, in part because the gangsters could extort the owners and clientele under threat of public exposure. It’s been said that each New Yorker once paid a small daily fee to the mob, hidden in the slightly elevated price of every retail purchase or restaurant meal.

But the government pushed back and won in some instances: Murder, Inc., was broken up after one of Buchalter’s deputies, Abe “Kid Twist” Reles, turned state’s witness. (Reles, after he’d incriminated several underbosses and was preparing to talk about bigger fish, died from an ostensibly accidental fall out a window.) In the late 1950s, the links between the Democratic Tammany Hall machine finally gave out, and Albert Anastasia—who held power over the dockworkers union—was killed on the orders of the Gambino family, consolidating its power over the aging heads of the Five Families. Robert Kennedy, as attorney general in his brother’s administration, stepped up prosecution efforts as well. In one curious turn, Joe Gallo, a boss in the Profaci family, advocated for opening up the ranks to African-Americans in order to broaden the talent pool and the family’s reach (leading to Nicholas Gage’s book The Mafia Is Not an Equal Opportunity Employer). Gallo’s colleagues did not agree, and he was shot to death during a lunch at Umbertos Clam House in Little Italy in 1972.

The real change, though, came with the passage of the Racketeer Influenced and Corrupt Organizations laws in 1970. Known as RICO, they gave government lawyers broader power to prosecute groups as well as individuals and take their assets. Over the next decade, as the turf wars continued among the Five Families, the U.S. Attorneys’ offices began to take larger and larger bites out of the mob. In the Southern District of New York, the most prominent prosecutor, Rudolph Giuliani, built his future career on a record of indicting and (mostly) convicting the heads of these families. John Gotti, the Gambino chief who was the last superpower in the New York Mafia, received a life sentence in 1992. Vincent “the Chin” Gigante, the Genovese-family boss known for ordering a hit on Gotti—and for ambling around Greenwich Village in his bathrobe—was convicted in 1997 and died in prison. Generational change helped weaken it further: The children and grandchildren of powerful mobsters often went to college, abandoning what was effectively the family firm in favor of straight businesses, leaving nobody to run them. They moved to the suburbs, too, where they couldn’t keep an eye on one another quite as easily.

The Italian mob still exists in New York, albeit in vastly shrunken form, confined mostly to drug trafficking, loan sharking, and a few other fields. It now coexists with the New York arm of its Russian equivalent, which operates in similar realms and is also known for complex money-laundering operations. Today the actual presence of organized crime in the city is overshadowed by its perceived presence, owing to its popular fictionalized versions. The Godfather, Mario Puzo’s 1969 novel, and Francis Ford Coppola’s trilogy of films adapted from it introduced its culture and lingo (consigliere, capo) to outsiders, leaning on a vision of the Mafia’s brutal glamour and deep sense of family ties. So did Martin Scorsese’s film GoodFellas, so did David Chase’s award-winning TV show The Sopranos, and so did about a thousand other books and films and songs. After The Godfather’s release, more than a few mobsters were said to have remodeled their behavior and even their accents on those of the fictional Corleones.

3 Three Famous Rub-Out Joints Where You Can Still Eat

Da Gennaro (former home of Umbertos Clam House)(129 Mulberry St.)

Da Gennaro (former home of Umbertos Clam House)(129 Mulberry St.)

At the original location of Umbertos—which has since moved twice, and is now across the street—the Profaci family hitman known as “Crazy Joe” Gallo was shot to death at his own birthday party in April 1972. The restaurant had just opened, and one local told the Times, “Just goes to show, you shouldn’t try new places.”

Sparks Steak House (210 E. 46th St.)

Sparks Steak House (210 E. 46th St.)

On December 16, 1985, Constantino Paul Castellano, boss of the Gambino crime family, came for lunch and was gunned down in a coup.

Rao’s (455 E. 114th St.)

Rao’s (455 E. 114th St.)

Albert Circelli and Louis Barone of the Lucchese family were dining here on December 29, 2003, when Circelli started heckling a young Broadway star’s impromptu performance. Barone demanded that Circelli stop, and when he refused, Barone shot him dead.

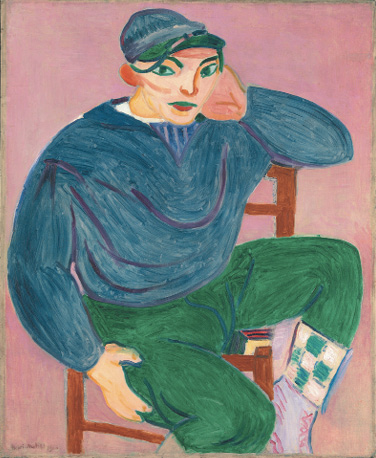

The Armory Show opened in New York on February 17, 1913. By the time it closed, less than a month later, nearly 90,000 people, by far the largest audience that had ever attended an exhibition of contemporary art in this country, had come to the 69th Regiment Armory on Lexington Avenue at 25th Street to see it; the last day drew over 10,000 visitors in the wake of enormous waves of publicity. Former president Theodore Roosevelt attended. When the show traveled to Chicago, the attendance was estimated at 188,000. American art can be divided into Before and After the Armory Show: Before it, art was being made in the U.S. but not with the same drive, ambition, confidence, and world-changing vision. After it, the advancements of European artists mixed with the already impressive work of a handful of Americans pushed art in this country into a completely new existence.

Originally dubbed the “International Exhibition of Modern Art,” the show included around 1,200 works by more than 300 artists and was organized entirely by a group of young American painters and sculptors. Two-thirds of the pieces were by Americans, but the Americans weren’t the ones who produced this genesis moment. This was the first in-the-flesh, in-depth look at the art of Picasso, Braque, Picabia, Cézanne, Kandinsky, Kirchner, Courbet, Daumier, Degas, Derain, Gauguin, van Gogh, Léger, Manet, Monet, Munch, Pissarro, Redon, Renoir, Seurat, Toulouse-Lautrec, Archipenko, Bonnard, Brancusi, Duchamp, Matisse, and many others. How significant was the show? Salon impresario Mabel Dodge wrote to Gertrude Stein that it was “the most important public event… since the signing of the Declaration of Independence.” She predicted it would cause “a riot and a revolution and things will never be the same afterwards.” One New York critic wrote that “American artists did not so much visit the exhibition as live at it.” Albert Barnes, Henry Frick, and the Met bought work from it, and the founding of MoMA and the Whitney stems directly from those 26 earthshaking days.

Artists may have been thunderstruck, but nonartists exploded an atom bomb of anger. The New York Times headlined a story “Cubism and Futurism Are Making Insanity Pay.” (There were no Futurists on hand, however; they were invited, but their leader, Filippo Marinetti, wouldn’t allow his artists to mingle with Cubists.) The participants were lambasted as “paranoiacs,” “degenerates,” and “dangerous.” The show was like “visiting a lunatic asylum”; it was filled with the “chatter of anarchistic monkeys.” The art was “epileptic.” Matisse came in for especially harsh criticism. (More, even, than Duchamp’s sensation-causing Nude Descending a Staircase, No. 2.) Conservative American painter William Merritt Chase clucked that Matisse was a charlatan, and when the show reached Chicago, provincial art students tried him in absentia for “artistic murder, pictorial arson… criminal misuse of line.” They burned copies of his paintings and tried to burn him in effigy but were thwarted by local authorities. Critics opined that Matisse’s “poisonous” works were “the most hideous monstrosities ever perpetrated.” And what of the president? He barked that the art was “repellent from every standpoint” and concluded that there was “no reason why people should not call themselves Cubists, or Octagonists, or Parallelopipedonists, or Knights of the Isosceles Triangle… one term is as fatuous as another.”

Most art historians today say American artists in 1913 were yokels and the Armory Show marked the arrival of European sophistication on our shores. Although the U.S. was behind the curve, Americans did know change was afoot. Between 1907 and 1913, more than 60 exhibitions of “modern art” were held in New York. Alfred Stieglitz had opened a tiny gallery at 291 Fifth Avenue in 1905 that had almost as big an effect as the Armory Show, championing Americans like Georgia O’Keeffe, John Marin, Paul Strand, and Marsden Hartley. Stieglitz also showed Europeans like Picasso, Matisse, Brancusi, and even Duchamp’s world-changing urinal turned on its side, Fountain. By 1913, Americans were—apart from the academicians—keen on the European vanguard. Numerous Americans had studied, worked, or exhibited in Europe, including many women. (Almost 20 percent of the Americans in the Armory Show were female—a better ratio than we often see today.) One thing the Armory Show revealed was that a number of “modern” American artists—realists like William Glackens, Robert Henri, and George Bellows, with their vernacular street scenes and pictures of prostitutes and boxers—were in a different universe than their European counterparts. Indeed, all but a few of the American artists trying to be “modern” were desperately trying to do it without Cubism, Fauvism, or Futurism.

But the Armory Show was a blast of fresh air for those American artists who had already gleaned what counted as “modern art” since the 1870s. Marin’s mad, quasi-Cubistic watercolor of New York’s St. Paul’s Chapel was in the show; ditto Oscar Bluemner’s flat planes depicting the Hackensack River. Edward Hopper’s paintings, which aren’t exactly “modern,” already show signs of the implacable isolation that would later make his paintings quake. Maurice Prendergast’s street scenes had completely digested Impressionism. More than this, many of the other American artists included in the Armory Show—among them Hartley, Mary Cassatt, Agnes Pelton, Stuart Davis, Elie Nadelman, Charles Sheeler, and Joseph Stella—felt as if they were now part of something much bigger than a little local New York struggle. They were citizens of a new international avant-garde.

4 Works From the Armory Show You Can See at the Metropolitan Museum of Art

1.

2.

3.

4.

5.

What makes a dance “modern”? The same thing that makes a painting modern—a de-emphasis on narrative and representation and a turning toward the material of the work itself. In the case of dance, the material is movement, shape, gesture, emotion, and the body itself. Modern dance is also defined as a historical movement, primarily developed from the 1920s through the 1960s. It’s an Expressionist, muscular style that rejects the refinement of Western classical dance, being energized by the twisting torso (rather than the drifting arms) and focusing its movements on the floor rather than the air, where, in ballet, a dancer is meant to float.

First came the prophet: Isadora Duncan. In 1896, Duncan traveled to New York from San Francisco to perform with Augustin Daly’s theatrical company. She had already begun developing her new, instinctive method of dancing—a primal, expressive movement she claimed was “the art which has been lost for two thousand years.” She rejected almost everything about ballet: its emphasis on formal steps, its corsets and its shoes. But she became frustrated with Daly’s melodramas and started presenting her dance concerts in high-society New York living rooms, trying to find aristocratic patrons. And while Duncan later fled to Europe, where her iconoclastic work was more fully embraced, she returned to America in 1914 for a seminal season at the New York Century Theatre—where she spent nearly her entire savings on $2,000 worth of heavy-scented lilies for decorations. In both her bohemian life and her ecstatic art, Duncan wore free-flowing unstructured garments; her hair was down, her feet were bare. She insisted that in dance, movement should be organic, that every gesture should dictate the next. And so her own movements dictated the future: 120 years later, all modern dance is infused with her spirit.

While Duncan tied her work to classical Greece—many of her gestures were imitations of images from vase paintings—the other protomodern master choreographers, Ruth St. Denis and Ted Shawn, looked further east (St. Denis based many of her dances on “Oriental” and Indian movement) and to Americana. Together they formed Denishawn Dance in Los Angeles and, through their wildly successful Denishawn School of Dancing and Related Arts, trained the woman who would come to define modern dance: Martha Graham. In 1923, disappointed with commercial tendencies among the Denishawn company, Graham struck out on her own and, in 1926, founded the Martha Graham Center of Contemporary Dance on New York’s Upper East Side. Soon she and her dancers began performing her often harsh modernist works (stark sets, simple costumes) throughout New York, transforming dance in the same way lightning transforms dry grass.

Like Duncan, Graham took inspiration from classical Greece—her Errand Into the Maze, for example, was loosely based on ideas about the Minotaur. And like the Denishawn team, she took inspiration from Americana, working with composer Aaron Copland and designer Isamu Noguchi for another of her masterpieces, Appalachian Spring. Dancing well into her 70s, she eventually crossed over into the mainstream and was named Time magazine’s Dancer of the Century in 1998, becoming known in circles that would normally never care about experimental dance. More important, over the course of 181 choreographic works, Graham refined her technique of contraction and release, developing a vivid, percussive, energetic method that would “increase the emotional activity of the dancer’s body.” Even in her most lyrical pieces, effort was at the marrow of Graham’s project; every dance was meant to be a “graph of the heart.”

The lineage of American modern dance largely descended from Graham and her fellow ex-Denishawner, Doris Humphrey. In 1928, Humphrey moved to New York, where she developed her own modern-dance technique rooted in fall and recovery, or the “arc between two deaths,” as she described it. With the exception of the great Alvin Ailey (who was trained by Lester Horton and founded his own company in New York in 1958), the major figures of the third modern-dance wave were often connected to one of the two women: José Limón started as Humphrey’s student and eventually employed her as artistic director in his own company; Paul Taylor danced for Graham for several seasons in the mid-’50s while choreographing for his own troupe. Taylor’s minimalist work veered eventually into postmodernism, playing with silence and obstruction—his 1975 Esplanade explores the poetry of everyday movements like walking. Another Graham dancer, Merce Cunningham, would stride even further from her dramatizing elements, moving fully into the avant-garde and embracing elements of chance and, later, computer-assisted choreography. When you watch the dispassionate, silvery movement of the Cunningham company, nothing could seem more divorced from the Expressionistic work of the high moderns. Still, you can see glimmers here and there. It’s in the twist of a torso, the flash of a bare foot.

In the 1970s, Lewis Ranieri, a mailroom employee who’d graduated to the trading floor at Salomon Brothers, began “securitizing” mortgages that weren’t eligible for grouping under the loan companies Fannie Mae or Freddie Mac—i.e., consolidating them and selling them to investors as securities in a new secondary market. In the ’80s, Ranieri normalized these securities by going to Congress to allow pension funds and banks to invest. The congressional okay opened them up to huge swaths of the market: By 1986, the private-label mortgage-backed security was worth $150 billion. “Mortgages are math,” said Ranieri, and to do the homework, he hired Ph.D.’s to determine the most efficient methods of selling them. These became collateralized mortgage obligations, or CMOs—high-yield, low-risk collections of mortgages layered into “tranches” of risk designed to protect the more stable bonds in the group. In 1987, Wall Street’s Drexel Burnham Lambert, the lion of the junk-bond market, invented the similar collateralized debt obligation, or CDO.

It took almost 30 years, but these three concepts would merge in the housing boom of the mid-2000s. This bubble was built on mortgage-backed securities and CDOs with unstable mortgages, offering high returns and artificially low risk thanks to the rating agencies. When housing prices peaked in 2006, homeowners could not refinance, adjustable-rate mortgages caused higher monthly payments, and delinquencies ballooned. Then the mortgage-backed securities went down, banks were stuck with billions in collapsed CDOs, and the recession hit. “I will never, ever, ever, ever live out that scar that I carry for what happened with something I created,” Ranieri told The Wall Street Journal in 2018. “It did so much damage to so many people.”

Pictures began to move, commercially speaking, at Thomas Edison’s laboratory in West Orange, New Jersey, in the 1880s and early 1890s. One of the first public demonstrations was held on May 9, 1893, at the Brooklyn Institute of Arts and Sciences—today’s Brooklyn Museum—where audience members lined up, peered into the little window of a machine, and watched a few moments of a blacksmith at work. (The Brooklyn Eagle reported the next day that the experience could “excite wonderment.”) The next year, the first “kinetoscope parlor,” with coin-op versions of those machines, opened at 1155 Broadway, essentially creating the original moviegoing experience.

In 1894 and 1895, a few of Edison’s ex-employees and competitors made short films in Brooklyn and Manhattan, and on April 23, 1896, Edison demonstrated his Vitascope system (which he hadn’t invented himself but had recently acquired) at Koster & Bial’s Music Hall, located on the block of 34th Street where Macy’s is today. He screened dancers, crashing surf, and a short boxing comedy and soon established a studio on West 28th Street. Edison was, very soon, joined by a lot of people who really wanted to direct. By 1905, movie production had become a proper industry, and most of it happened in New York. American Mutoscope, later known as Biograph, was headquartered first near Union Square and then in the Bronx; it launched the career of the great director D. W. Griffith. Adolph Zukor’s Famous Players Film Company operated out of a converted armory on West 26th Street (which, incredibly, is still a television studio; Rachael Ray’s cooking show is shot there). Carl Laemmle started the Independent Moving Pictures Company, headquartered in New York and shooting across the river in Fort Lee, New Jersey.

In the earliest days, the films they made were reenactments of famous historical events, but after a few years, they began to shift to fictional stories—miniature plays, a few minutes long. Many of those were shot in studios and are universal in setting rather than specific to city life. Most have also been lost, and those that survive are often of historical interest but not so lively as cinema. One little exception is a 1901 Edison production called What Happened on Twenty-Third Street, New York City, shot near the brand-new Flatiron Building and showing wind from a subway vent kicking up a young woman’s skirts, uncannily like Marilyn Monroe’s a half-century later in The Seven Year Itch. Another short film documents a trip uptown on the subway, shot from the front car. It’s from 1905, when the IRT was a year old, and you can watch it on YouTube.

The ’10s and ’20s allowed the movies to grow up somewhat. The “two-reeler,” running twenty minutes or so, became a dominant form of comedy, and hundreds of these films were produced in New York. Famous Players merged with another studio, Lasky, and eventually took the name of its distributor, Paramount. Independent Moving Pictures also merged with several firms, becoming Universal Pictures. But the end of New York’s status as the movie capital was coming into view. Early film was best shot in bright sunlight—the emulsion was not as light-sensitive as it became later—and New York had a long, gray winter. Also, Edison’s royalty collectors were extremely strict, and in the days before cross-country communication, it would be easier to dodge them at a distance. By 1920 or so, the industry was shifting its business to Southern California, which had endless sunny days and a wide variety of locations (desert, beach, mountains) in which to shoot. The arrival of talkies in 1927 more or less killed the New York location shoot because crowds and traffic noises made hash out of the audio tracks. For the next twenty years, New York as a presence in the movies was almost completely re-created elsewhere. The noir gangsters, the screwball-comedy heiresses, and the Park Avenue antics of Nick and Nora Charles in The Thin Man—all existed principally on the back lots of Los Angeles.

Until 1947, that is, when Jules Dassin and his producer Mark Hellinger made the daring decision to return to New York and shoot their film The Naked City in its streets. Some short sequences for other movies had been shot here, notably for The Lost Weekend a couple of years earlier, but Dassin would shoot most of his outdoors in New York and in real city apartments, culminating in a chase sequence on the walkways of the Williamsburg Bridge. (To avoid drawing large disruptive crowds, they often concealed their cameras and microphones with makeshift structures and inside trucks.) The location shoot added a vast amount of verisimilitude and atmosphere to the film.

Yet, a few great moments aside (like 1957’s Sweet Smell of Success, partly shot in and around Times Square), New York as a real backdrop did not quite come roaring back until after 1966. That was when Mayor John Lindsay, having learned that the city’s tortuous permit process was causing filmmakers to stay away, created a single agency, now called the Mayor’s Office of Film, Theater & Broadcasting, to cut the red tape. An immediate increase in the number of local productions followed.

As it happens, this could not have come at a better time for cinema, because the social dynamics of New York in the 1970s and 1980s turned out to be solid gold for filmmakers. Over the next fifteen years, the big movies shot here—and they were unmistakably, indelibly made here, not in California—established both the tragedy of broken-down New York and its cracked-mirror beauty, and along the way they set a new standard for filmmaking grit. Consider this extremely incomplete, entirely compelling list: Mean Streets, Rosemary’s Baby, The French Connection, Midnight Cowboy, Panic in Needle Park, Taxi Driver, Serpico, Shaft, Dog Day Afternoon, Annie Hall, The Taking of Pelham One Two Three, The Warriors, and, at the tail end of this era, Do the Right Thing. Martin Scorsese, in particular, became the bard of this befouled city; Woody Allen, his emotional polar opposite, portrayed New York as a charming, magnetic place rather than a dark one.

As the city recovered and grew wealthier in the 1990s (and after Miramax set up shop here, bringing a powerhouse independent company to the birthplace of the industry), the somewhat warmer cinematic view of New York began to supersede the grittier one; When Harry Met Sally…, Crossing Delancey, Metropolitan, and even, perhaps, Home Alone 2: Lost in New York were harbingers. At a distance from the mainstream, portrayals of the city in films like Spike Jonze’s claustrophobic Being John Malkovich, released in 1999, could get weird and often surreal. But in the twenty-first- century multiplex, the upper-middle-class, aspirational New York more familiar from sitcoms and novels reigned over all, as in the angsty couplings of Noah Baumbach’s films and the fashion-magazine intrigue of The Devil Wears Prada. Though not in every movie: Jennifer Lopez’s stripper character in Hustlers is shaking down those callow investment bankers for as much as she can get.

5 The Essential New York Movies

Chosen by the editors of Vulture.com

When Theodore Roosevelt coined the term muckraker in a 1906 speech, he didn’t mean it as a compliment. “The man with the muck rake”—an image he borrowed from the English writer John Bunyan—was, to his thinking, a journalist operating down in the mud, one obsessed with the worst aspects of society. Of course, the muckrakers themselves saw it differently. The term soon became shorthand for a lefty activist-journalist of the Progressive Era who was crusading against inequity or corruption. Ida Tarbell (on the business practices of Standard Oil), Jacob Riis (on slum conditions), Lincoln Steffens (on civic corruption), and Upton Sinclair (on unsafe food practices, among other subjects) epitomized the genre, and all spent their peak career years living and working in New York City. Two magazines, also headquartered here, were arguably the central publishers of the early muckrakers’ work: McClure’s, where Steffens and Tarbell often wrote, and Collier’s, whose 1905 publication of one of Sinclair’s exposés, “Is Chicago Meat Clean?” led to the passage of the landmark Federal Meat Inspection Act the following year.

Although neither magazine survives—McClure’s went bankrupt, became a women’s magazine, and folded in 1929, and Collier’s closed, after a long twilight, in 1957—the muckraking tradition outlasted them. At The Village Voice (see also ALT-WEEKLY), for example, Wayne Barrett was a perpetual irritant to the administration of Mayor Rudolph Giuliani and dove deeply into the practices of the Trump Organization (see also TRUMPISM). WikiLeaks and the Intercept are arguably digital-age descendants of the muckrakers. And the investigative unit at the New York Times now does it all day, every day.

Surely they’re… English? Nope. Those are crumpets. But in 1874, an Englishman in New York named Samuel Bath Thomas started baking a crumpet variant from a yeast batter. The resultant baked good was a little more breadlike and fluffy than its British sibling. His Chelsea bakery, briefly on Ninth Avenue and then at 337 West 20th Street, very quickly reached its capacity and eventually grew into a national brand. (Today Thomas’ is owned by the Bimbo Bakeries conglomerate.) In 2006, renovations to the 20th Street structure revealed a brick oven still extant underneath the backyard. The building, now a co-op (see also COOPERATIVE APARTMENT BUILDING), has been renamed the Muffin House.

If you want to be finicky, you could trace musical theater back to the ancient world, when, in the fifth century BCE, it emerged from chanting and verse. We had chorus lines before we had shows to put them in. But when we think of musical theater now, we think of Broadway’s much-tinkered-with recipe of a cohesive play, or “book,” interspersed with songs (which often advance the story) and expressed with razzle-dazzle. There are musicals like Evita, Falsettos, and Cats that are “sung-through” like operas, and musicals like Jersey Boys and Mamma Mia! whose songs barely graze the plot. The balance of dancing, dialogue, and song changes in every combination, and even now people can disagree on whether a show is a “play with music” or a “musical.” But you can always tell where the line is, and those lines were all drawn in New York.

The modern American book musical evolved in the nineteenth century out of revues, Gilbert-and-Sullivan-style operettas, and plays sprinkled with hit songs. The Black Crook, a huge hit in New York in 1866, usually gets credit for being the form’s first “true” example, and its origin story is classic: Two impresarios booked a Parisian ballet company into the huge Academy of Music, but the Academy burned down; meanwhile, a melodrama had booked another large local venue, so the ballet impresarios and the melodrama’s playwright joined forces and called it a show. The spectacle-filled result packed the 3,200-seat Niblo’s Garden (at Broadway and Prince Street) for 474 performances and was revived and toured for decades to a totally unprecedented degree, proving that in New York, even a huge property fire is opportunity knocking. That same year, Black Domino/Between You, Me and the Post was the first show to call itself a “musical comedy,” and in 1860, The Seven Sisters had innovated with scene changes, a book, songs, and special effects. But The Black Crook had all the basics: a unifying book, some purpose-written songs, and the actors themselves (rather than a cameo troupe) performing the musical numbers. Its original tunes, like “You Naughty, Naughty Men,” hint at the reason for its runaway business. The ballet dancers did not wear a lot.

By the early twentieth century, the block of West 28th Street between Fifth and Sixth Avenues (see also TIN PAN ALLEY) was churning out hits by the likes of Irving Berlin, which then found their way into theatricals, and offering work to future icons like Victor Herbert and George Gershwin. The super-producer Florenz Ziegfeld soon dominated the scene with his star-making Follies, while now-vanished forms like minstrel shows, acted by both Black and white performers, and vaudeville variety acts swept the nation. The ne plus ultra of song-and-dance men, George M. Cohan, soon brought vaudeville to the “legitimate” stage, creating beloved musical comedies that sat at the core of America’s sense of itself: He was a “Yankee Doodle Dandy.” He sang “You’re a Grand Old Flag.” He crooned “Give My Regards to Broadway,” turning the street into a metonym for patriotic pride. George and Ira Gershwin, Richard Rodgers and Lorenz Hart, Cole Porter—all were writing dazzling lyrics full of surprise and vivid comedy. Shows and their songs became more tightly integrated, and the Broadway signature became sparkle and craft.

Chita Rivera and Liane Plane in the original Broadway production of West Side Story, 1957.

PHOTOGRAPH BY HANK WALKER

Then came the hammer blow: 1927’s Show Boat. During the interwar years, lyricist-librettist-producer Oscar Hammerstein II had wondered if there was a way to reclaim some of the majesty of grand opera while still remaining “sufficiently human to be entertaining.” The composer Jerome Kern wanted to stage Edna Ferber’s sweeping novel about people working on a riverboat, and his and Hammerstein’s vivid adaptation brought a seriousness of intent to the musical—here was opera, vernacular entertainment, and popular musical comedy, all joined into one. According to historian Larry Stempel, “There simply was no cultural frame of reference at the time adequate to describe the piece.” Our theatrical history divides into before Show Boat and after: The musical had finally made its claim as art.

But the Depression followed, sending writers and performers west to Hollywood and pausing the advancement of the form. Not until a decade and a half later did another Hammerstein show raise the American book musical to international preeminence. Rodgers and Hammerstein’s 1943 Oklahoma! was thematically akin to Show Boat in the way it used folk idiom, rather gravely framed the American story, and focused on landscape as an encompassing metaphor for the democratic project. But Oklahoma! was also a definitive formal step forward. Its speech segued gracefully into song to signal heightened emotion, move the story along, and explicate characters, rather than being an interruption or ornament. Music and drama were finally blended, as was the mix of high and low art the musical had long promised. Oklahoma! was both a wildfire commercial success and a critical one. As the globe moved into a long period of American influence, theater carried at least one part of the message out—and the musical’s hundred-year invention was complete.

The corresponding golden age leaned heavily on the Rodgers and Hammerstein canon—South Pacific, Carousel, The King and I, The Sound of Music—and many of their shows were turned into films. The mid-century love for movie musicals gilds them even now: Cinema is why we have such live-wire contact to the greats like Guys and Dolls (1950), My Fair Lady (1956), West Side Story, and The Music Man (both 1957). Bearing such cultural weight, musicals became a site to negotiate changing ideas of American values. They got sweet for kids (Annie) and groovy with rock and roll (Hair) while elevating Stephen Sondheim, who is still the fiercest, least sentimental intellect ever to grapple with the musical. In 1970, he and director Harold Prince joined forces for Company and stormed through the rest of the decade with one groundbreaking show after another—all excitingly modern, psychologically precise, and anti-nostalgic, the acid that eats through layers of paint to show the form beneath. And anti-sentiment must obviously call into being its antithesis, the Foreign Big Emotion Musical, which would include Les Misérables and everything by Andrew Lloyd Webber.

When you look at the American musical today, you’re looking into a refracting mirror showing images of ages past: jukebox musicals (bombastic entertainment marathons much like nineteenth-century shows that exploited popular hit songs), Disney movies made into stage versions, golden-age revivals, new investigations in the realist mode (Next to Normal, Dear Evan Hansen), and Hammersteinian attempts to get a handle on the country itself (the immense hit Hamilton). And although musical theater is principally a Broadway product these days, it still starts downtown: The Public Theater, which developed and launched Hair, A Chorus Line, Hamilton, and Bloody Bloody Andrew Jackson, and New York Theatre Workshop, which originated Rent and Hadestown, sit very close to where the old Niblo’s Garden once stood.

6 Where to See a Broadway Star Dining Postshow

From New York theater critic Helen Shaw

Joe Allen Restaurant (326 W. 46th St.): “It’s been there since 1965, plenty of time to gather posters for its wall of flops. Visit to meditate on your show’s imminent death.”

Joe Allen Restaurant (326 W. 46th St.): “It’s been there since 1965, plenty of time to gather posters for its wall of flops. Visit to meditate on your show’s imminent death.”

Sardi’s (234 W. 44th St.): “Since theater is always vanishing, stage folks love a place with tradition; Sardi’s has been here since 1927.”

Sardi’s (234 W. 44th St.): “Since theater is always vanishing, stage folks love a place with tradition; Sardi’s has been here since 1927.”

The Lambs Club (132 W. 44th St.): “Eavesdrop on producers toasting their success or drowning their sorrows.”

The Lambs Club (132 W. 44th St.): “Eavesdrop on producers toasting their success or drowning their sorrows.”

Café Un Deux Trois (123 W. 44th St.): “Big and boisterous; the right place to eat giant slabs of country pâté and hoover up skinny French fries, while actors from the Belasco next door come to complain about how all the theaters east of Broadway do worse business.”

Café Un Deux Trois (123 W. 44th St.): “Big and boisterous; the right place to eat giant slabs of country pâté and hoover up skinny French fries, while actors from the Belasco next door come to complain about how all the theaters east of Broadway do worse business.”

West Bank Cafe (407 W. 42nd St.): “I can’t go in there without falling over Jonathan Groff.”

West Bank Cafe (407 W. 42nd St.): “I can’t go in there without falling over Jonathan Groff.”