Hearst’s ad for the New York Journal touting the Yellow Kid, 1897.

Joseph Pulitzer did an excellent job of reshaping his legacy when he endowed the highbrow awards given each year in his name. During his career as a publisher, he worked at a far less lofty level. In 1883, Pulitzer took over the New York World and immediately set out to build its business by any means necessary. There wasn’t much photography in the paper yet—it was technologically almost impossible to turn a photo into a printing plate on deadline—but illustration was another matter and the World was soon filled with it. By 1893, it had become the biggest-circulation newspaper in New York City, and that May it introduced the industry’s first Sunday comics section. Pulitzer soon hired a young cartoonist named Richard Outcault, and on January 13, 1895, he published a cartoon featuring a bald-headed, gap-toothed, slum-dwelling boy wearing a dresslike nightshirt. His was an image familiar to any tenement denizen; the dress was a hand-me-down, and the shaved head was the standard treatment for lice. Over the next couple of years, as the Sunday supplement went from black-and-white to blazing color, his tunic turned a brilliant gold, and he got a nickname: the Yellow Kid.

In these same years, Pulitzer’s paper was locked in a circulation war with William Randolph Hearst’s New York Journal. At one point, Hearst hired Pulitzer’s entire editorial staff en masse. Pulitzer struck back by cutting his cover price in a bid for bargain-hunting readers. Hearst retaliated by scooping up Outcault and his Yellow Kid. And both papers—particularly the Journal—began making questionable quasi-journalistic moves, overselling trivial events with sensational headlines and sponsoring promotional stunts mainly to report them as news. After one such event, a cross-country bicycle trek paid for by Hearst and then covered by his papers, a writer at the New York Press named Ervin Wardman noted that the bicyclists wore yellow. He gave this practice of news-manufacturing a sneering name: “yellow journalism.”

Despite the thinnest connection between the two, the yellow jerseys and the Yellow Kid melded in the popular imagination, and most histories today link the character with the term yellow journalism. (Wardman did once refer to “yellow kid journalism,” suggesting that he also associated the two.) That is most likely true because the circulation war—in which Outcault’s cartoons figured prominently, at least at the beginning—continued for years thereafter. In 1898, Hearst’s papers all but created the Spanish-American War out of thin air. (It’s said Hearst told his illustrators, “You furnish the pictures, and I’ll furnish the war”; a lightly altered version of that moment appears in Citizen Kane.) By then, the Yellow Kid’s regular strip had been shelved, and the character was making cameo appearances in Outcault’s other work. There he lingered well into the twentieth century, fading out for good around 1910. Pulitzer eventually wearied of the downscale turn and put the World back on sounder journalistic footing, where it stayed until it was merged out of existence in 1931. The term yellow journalism, however, outlasted it all. Today it gets thrown around constantly, used by political figures to describe genuinely sleazy stories (see also TABLOID) as well as anything they dislike seeing aired or written.

Hearst’s ad for the New York Journal touting the Yellow Kid, 1897.

The Yiddish Art Theatre’s Maurice Schwartz backstage on opening night, October 1, 1945.

PHOTOGRAPH BY WEEGEE

In the last quarter of the nineteenth century, hundreds of thousands of Jews from Eastern and Central Europe began to flow into America through Ellis Island. A large percentage of them settled on the Lower East Side, especially in the tenements east of the Bowery. (West of the Bowery was populated mostly by Italians, and a young man of either tribe crossed the street at his own risk.) They came from all over—Germany and Russia, the Baltics and the Balkans—and although their national languages differed, most had their spoken Yiddish in common. This community was simultaneously clinging for dear life to its familiar traditions and looking to assimilate, and in very short order, it began to create its own pop culture. On August 12, 1882, inside Turn Hall, at 66–68 East 4th Street, a small troupe performed an operetta called The Witch in Yiddish, and an Old World–New World hybrid genre was born: the American Yiddish theater.

Within the next couple of years, a small cluster of Yiddish-language venues opened around the corner on the Bowery. They specialized in melodramas and operettas in a wide variety of styles. Some shows were dramatizations of contemporary news events; others were heavily fictionalized biblical or historical tales. Many more were stories of everyday immigrant life: family, striving, betrayal, separated lovers, multigenerational strife. By and large, these productions were popular entertainments, broad and sentimental rather than cerebral, although there were Yiddish-language productions of Shakespeare and other highbrow fare. With more immigration came more theaters and more success, and in 1900 the Yiddish theaters of the Lower East Side sold 2 million tickets.

They had, to an extent, also moved (slightly) uptown. Around 1900, Second Avenue below 14th Street began to supplant the Bowery as the center of Yiddish entertainment. While uptown, first in the Union Square theater district known as the Rialto and later around Times Square, was home to John and Ethel Barrymore and George M. Cohan, downtown on the Yiddish Rialto, Boris Thomashevsky, Jacob Adler, and Molly Picon had their names in lights. The big theaters on Second Avenue were large and opulent, similar to their equivalents on Broadway (see also BROADWAY; MUSICAL THEATER; TIMES SQUARE), and large Jewish communities in the Bronx and Brooklyn eventually got their own venues to match. By the 1920s, the Yiddish theater was an immense business in New York, not nearly as big as its English-language sibling but in the same league.

The first great era of immigration ended with restrictive new laws in 1924, and—mene, mene, tekel upharsin—the writing was on the wall. Assimilation was, of course, the proximate cause of the genre’s decline. The children and grandchildren of immigrants stopped speaking Yiddish, went to college, moved to the suburbs, and generally made their way into the mainstream. The Depression badly dinged all forms of live theater, as did radio, movies, and then television. And Gentile artists began to dip into the Yiddish-theater well, de-ethnicizing it for wide consumption. The song “Bei Mir Bist du Schön” became a huge radio hit—after the extremely goyish Andrews Sisters recorded it in English in 1937.

As the Yiddish-speaking world of Second Avenue faded, some performers took their acts to Jewish summer resorts in the Catskills. The Café Royal, the social center of the strip, closed in 1952. Picon, probably the biggest female star in the Yiddish theater, resettled on the radio and in films and had a big hit with Milk and Honey on Broadway in 1961. And the definitive tribute to the Yiddish theater came along in 1964, when Jerry Bock, Sheldon Harnick, Joseph Stein, and Jerome Robbins joined forces to adapt a principal text of Yiddish-speaking America—the stories of Sholem Aleichem—into the Broadway musical Fiddler on the Roof. (Robbins himself had been a child performer in the Yiddish theater; the show’s set designer, the great Boris Aronson, had started there as well.) Fiddler’s story of Anatevka was an elevated, somewhat more sophisticated rendering of the immigrant stories familiar to those audiences, and it spoke to the Americanized children of those Second Avenue theatergoers as few shows ever had.

Very little physical presence remains of the Yiddish Rialto. Probably the last of its major stars, Fyvush Finkel, had a late-in-life rebirth on the CBS drama Picket Fences and won an Emmy for it in 1994. The Yiddish Art Theatre’s home, on the corner of East 12th Street, is a mainstream movie theater now. The great film director Sidney Lumet, who had been a child actor with the company, died in 2011. In the 1990s, Abe Lebewohl, proprietor of the Second Avenue Deli, embedded in the sidewalk at Second Avenue and Tenth Street a Yiddish Theater Walk of Fame, a Jewish echo of the one on Hollywood Boulevard, with Finkel and Picon in place of Jack Nicholson and Faye Dunaway. Beginning in the 1990s, a new generation of young advocates, attempting to keep the flickering flame of their grandparents’ language alive, mounted small-scale stagings of some old Yiddish-theater productions, notably through a troupe called the National Yiddish Theatre Folksbiene. In 2018 the Folksbiene closed the assimilative loop with a staging of Fiddler on the Roof—translated into Yiddish.

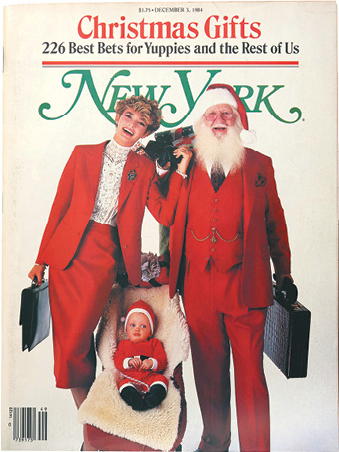

The baby-boom generation born after World War II, the first raised on a television diet, was generally far more aware of consumer culture and its sociological significance than its predecessors had been. Their parents might have been reliable Ford or Chevrolet buyers, but boomer kids would make much finer distinctions—between, say, a Chevy Camaro (not bad) and a Camaro SS (much cooler). Although many relatively affluent kids influenced by the 1960s counterculture flirted with anti-consumer attitudes, in young adulthood they too began to fall back into comfortable materialism. A frustration with the era’s economic malaise contributed to the rise of a dominant neoconservatism, its first defining peak coming with Ronald Reagan’s election in 1980. In New York City in particular, the Reagan-era recovery took place primarily in the finance industry, which tended to hire young, aggressive, educated people (including for the first time quite a few women), many of whom lived in Manhattan and drew solid junior-executive salaries. The other glamour industries—law, publishing, advertising—were similarly staffing up, in many cases giving employees solid expense accounts and even the occasional signing bonus. The upshot of all this was the accidental creation of a new archetype: the young urban professional, a.k.a. the yuppie.

The yuppie was not necessarily flat-out rich but lived well. (One subset of yuppiedom was the DINK, or “dual income, no kids,” household. DINKs were notable for their high levels of disposable income.) The distinguishing characteristic of the type was bourgeois taste justified on the grounds of craftsmanship, worthiness, and authenticity. Buying a Mercedes-Benz was good materialism because it was sturdy and smooth on the road and might last for decades; buying a Cadillac, less so, because it was too plush and had fake wood grain and might break down. The same went for fancy European plumbing fixtures and non-iceberg salad greens, Nakamichi stereo equipment and Prince carbon-fiber tennis racquets, Lacoste polo shirts and Michael Graves for Alessi teakettles. Not to mention a name-brand college education.

Yuppies could be found among book editors, ad executives, academics, and lawyers—especially lawyers. Every city in America had them (Michael and Hope Steadman, the quintessential yuppie couple from television’s thirtysomething, lived in the inner-ring suburbs of Philadelphia), but New York probably had more than any other because of its concentration of professional jobs.

Nobody liked to be called a yuppie; virtually no one accepted the label. And people hated yuppies. Hated them! Issues of class, issues of race, issues of privilege—yuppies by their mere presence evoked them all. A commonplace graffito in these years read DIE YUPPIE SCUM. You’d see it most often in neighborhoods like the East Village, which remained relatively inexpensive because it was too grungy for your average yuppie, a risky place to park a BMW. Yet even as the media reported on the yuppie phenomenon with cocked brow and jaundiced eye, they catered to yuppies, carrying Rolex ads and reviewing restaurants that used truffle oil, because that was where the spending lay. Jay McInerney and Bret Easton Ellis wrote novels disdaining yuppie culture and its signifiers, but both of them lived, and continue to live, a solid approximation of that life.

Needless to say: The yuppies won. New Yorkers live in Yuppietown now, a place where in quite a few neighborhoods, a Starbucks is easier to find than a hardware store. Even in the ostensibly anti-yuppie enclaves of artisanal enthusiasts (see also HIPSTER), much the same obsession with material culture and quality applies, albeit with different aesthetics and emphases. In fact, the yuppie has been superseded in the battle of privilege. Your typical mid-level book editor or ad copywriter or marketing associate can barely afford New York these days, and the competition for resources is between the solidly rich and the absolutely superrich. To sustain a genuinely comfortable New York lifestyle today requires quite a bit more than two average professional incomes. You have to compete with hedge-funders to get a nice apartment, and you probably can’t do that. The yuppie has been out-yupped.

1 Yuppie Signifiers That Have Stood the Test of Time

Chosen by New York design editor Wendy Goodman