Once everywhere, now effectively extinct, the light-entertainment genre known as vaudeville—staged variety shows with popular song-and-dance numbers, comedy, and bits of drama, shot through with minstrelsy—has many roots. It is variously traced to France (the word attributed to the phrase voix de ville, “voice of the city,” or to the town of Vau de Vire in Normandy, known for its bawdy songs), London (where variety was the preferred term), Boston, and San Francisco. Its first permanent venue, though, is generally recorded as the “concert saloon” called the Bowery, which opened on the Bowery itself around 1848. Within a few years, similar performances had popped up at a variety of theaters, notably the Melodeon Concert Hall at 539 Broadway, from which performers took their shows on the road.

The form matured when a New York impresario named Tony Pastor got his hands on it. After a couple of decades in the business, he had the idea of turning this salty style into family entertainment, and in October 1881, he began performances at his Fourteenth Street Theatre (a thousand-seat venue that happened to be located inside Tammany Hall, the city’s center of Democratic political power), at which no alcohol was sold. Despite the ban, the house stayed full, and Pastor was briefly at the top of the vaudeville heap.

But it was a big, rollicking field, and he had a lot of competitors with thousands of seats of their own to fill. Over the next few years, the business began to be dominated by several chains known as “circuits”—companies that operated a theater in every midsize city and could therefore book tours efficiently. Their executives were almost celebrities themselves, akin to the studio heads of the next century. Edward Albee II (grandfather of the playwright) ran the Albee circuit; B. F. Keith, the Keith circuit; the West Coast’s Alexander Pantages, the Pantages circuit; Gustav Walter and later Martin Beck, the Orpheum circuit. They booked everything imaginable, including jugglers and ventriloquists. Reflecting the standards of the day, blackface performances were common, as were broad ethnic-immigrant stereotypes, from the drunken Irishman on down.

Harry Houdini’s escape act, signed to Orpheum, was a major draw (see also ESCAPE ARTIST). Lillian Russell, the actress and soprano, performed musical comedy, and W. C. Fields cultivated a world-class juggling act. An entire generation’s showbiz performers, from Ethel Merman to the Marx Brothers, learned their craft in the vaudeville houses. At their peak in the 1910s, the business involved 1,800 theaters around the country, and its biggest stars earned thousands of dollars a week. Vaudeville’s New York presence had begun to coalesce around Times Square after the turn of the century, and in 1913, shortly after the Keith and Albee circuits merged, Martin Beck opened the enormous Palace Theatre, which almost immediately became Keith-Albee’s crown jewel.

Then came a triple whammy. Silent film took a big bite out of the vaudeville business (even though short films were sometimes screened between the live acts); movies required no touring expenses and could run in any neighborhood at any time, and talkies, launched in 1927, were an even harder blow. Radio too was an existential threat, allowing people to hear pop songs and comedy without leaving their homes. And then came the Depression, when those cheap-to-consume entertainments were often the only option. Around the country, many circuit theaters converted to showing films, while movie studios offered big money to vaudeville stars to perform their acts before the cameras, exhausting their repertoires and effectively ending their touring careers. (To see a lot of the Marx Brothers’ vaudeville act, watch their first few films; in each one, a couple of set pieces are clearly repurposed from the stage.) The Radio Corporation of America (RCA) bought out the Keith-Albee and Orpheum circuits and became a movie studio, RKO Pictures, whose initials retain a ghostly trace of the old names. In 1932, the Palace’s live acts gave way to full-time cinema, marking the end of vaudeville as a major genre. The impresario Samuel Rothafel, known as Roxy, tried to give it a final boost by supersizing the venue, but that too flopped (see also RADIO CITY MUSIC HALL). Whatever was left of vaudeville after that was finished off by wartime austerity and then TV.

Which is not to say you couldn’t still see it: Because performers trained in vaudeville created many of the early radio and then television shows, their styles came to define the new formats. The comedy-variety hours that dominated TV in the 1950s, ’60s, and ’70s were basically vaudeville slates translated to the small screen, starring many middle-aged performers—Sammy Davis Jr., Judy Garland, Pearl Bailey, George Burns, Jack Benny—who’d lived out of a trunk on the circuit when young. When Garland performed nineteen weeks of comeback shows at the Palace Theatre in 1951, she wistfully sang, “So I hope you understand my wondrous thrill, / ’Cause vaudeville’s back at the Palace, and I’m on the bill!” And you can draw a pretty straight line from the Jewish-inflected wisecracker voices of the Marx Brothers and Milton Berle all the way up through, say, Seinfeld and Curb Your Enthusiasm.

In the 1750s, the British colony of New York—whose capital was then New York City—began granting white Europeans land in the rough triangular region to its northeast. But so did the colony of New Hampshire, disputing New York’s authority. Eventually, the British Privy Council had to adjudicate, and on July 20, 1764, New Hampshire’s claims were invalidated by a declaration from King George III, one that officially designated the area a part of New York. The New Hampshirite settlers didn’t like this and pursued challenges, but New York retained ownership.

After the Revolution began and the territory of not-yet-Vermont sent soldiers to the Continental Army, the question of whose land it was continued to simmer. Residents of the territory didn’t want any part of this internecine squabble and in 1777 declared full independence from both Britain and New York. The new nation called itself the Republic of Vermont and drafted its own constitution. Only in 1791, several years after the war’s end, did it give up on its self-governing dreams and join the new USA as the fourteenth state—after sending a big payment to New York to resolve any lingering land claims.

Since then, a couple of Vermonters have become president and a third has come very close, and, by coincidence, New York can lay claim to two of them. In 1881, Chester Alan Arthur, born in Vermont but a New York City resident for most of his adult life, won the vice-presidency and then, upon the death of President James A. Garfield, took the oath of office in his townhouse on lower Lexington Avenue. And in 2020, the democratic socialist Bernie Sanders—child of Brooklyn, onetime mayor of Burlington, and three-term senator from Vermont—came within shouting distance of the White House as well.

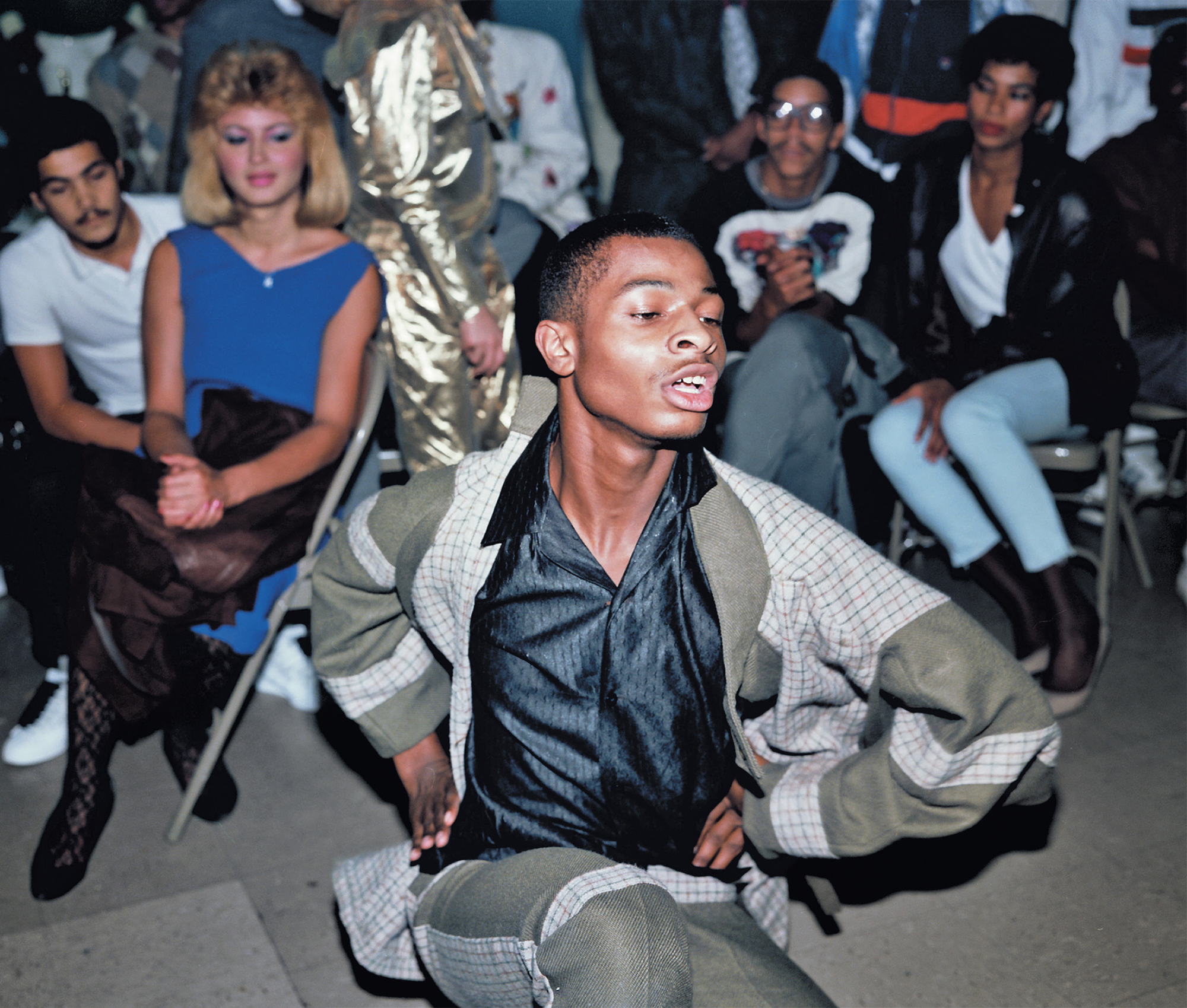

Channeling the glamorous hauteur of fashion models on the runway, the acrobatic competitive dancing known as voguing is the signature invention of the ballroom subculture that got its start in New York in the 1960s, when queer people of color, many of them transgender, created a parallel world to the one that usually excluded them. Its fierce theatricality and jargon were later adopted by white gay culture and eventually the pop mainstream.

Drag balls in Harlem (see also HARLEM) are documented as early as 1869, when the Hamilton Lodge hosted its first gay masquerade (see also GAY-RIGHTS MOVEMENT). By the 1920s, the poet Langston Hughes, after seeing a few white celebrities mix with a large gay, Black audience at one of them, could signal that Harlem was “in vogue,” but the drag scene continued to develop along racial lines. The 1968 documentary The Queen shows a confident Black contestant, Crystal LaBeija, who seems set to win a predominantly Caucasian midtown drag pageant until the judges, including the artists Andy Warhol and Larry Rivers, pass her over in favor of a young white upstart. LaBeija storms off, accusing the event of being rigged against people of color. In 1972 she and her close friend Lottie founded the first of New York’s “houses,” now the standard term for a team of drag performers, and held its inaugural ball at the Up the Downstairs Case club on West 115th Street in Harlem. Houses often function as surrogate families for people who have been rejected by their biological ones, some even attracting kids who are uninterested in drag.

Most competitions evolved to include categories of identities that contestants try to perfect: butch queen, “town and country,” and so on. They’re judged on “realness,” i.e., the performers’ ability to pass. The best-known convention, voguing, is (despite other roots) customarily credited to a performance by Paris Dupree in the early 1980s. According to the DJ David DePino, “At an after-hours [club] called Footsteps, on Second Avenue and 14th Street… Paris had a Vogue magazine in her bag, and while she was dancing she took it out, opened it up to a page where a model was posing, and then stopped in that pose on the beat. Then she turned to the next page and stopped in the new pose, again on the beat.” Another drag queen tried to one-up her with a different pose, but Paris returned the move. In 1981, at the first House of Dupree ball, voguing became a competitive category, the goal being to outshine your opponents—to put them in the shade, as participants began to say.

The 1990 documentary Paris Is Burning (titled after Dupree’s balls) revealed this scene to a wider world, as did Malcolm McLaren’s 1989 dance single “Deep in the Vogue” and Madonna’s 1990 hit “Vogue.” Proving that this tiny subculture has achieved maximum realness, RuPaul has since become a ubiquitous celebrity, House of LaBeija member Kia has been celebrated with a cover story in Artforum, and Billy Porter, starring in Ryan Murphy’s soapy ballroom drama Pose, won an Emmy award in 2019.

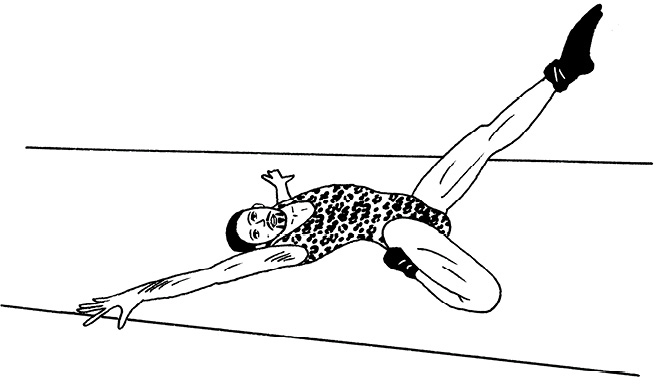

1 The Dip, Explained

From Pose star Jason Rodriguez

“If you know vogue, you know what a dip is. It’s a moment when a voguer hits a particular pose on the floor, gracefully and fearlessly finding the ground with their arms, with an arched back and an extended leg. A dip is the period to our sentence, a seal of our expression. A moment when the crowd extend their hands toward the voguer to embrace a moment in time that they’ve slayed the ballroom floor.”

Striking a pose in Brooklyn, 1986.

PHOTOGRAPH BY JENNIE LIVINGSTON