Macy’s was not yet in Herald Square in 1874. It was still a dry-goods store in its original location at Sixth Avenue and 14th Street, although it already had as its logo the red five-pointed star (based on a tattoo that R. H. Macy himself had on his arm) it uses to this day. There, a December tradition began behind the large plate-glass windows (themselves a relatively recent technological innovation) that would continue to attract shoppers and spectators for decades to come. Some nameless marketing person put up a display of porcelain dolls re-creating scenes from Harriet Beecher Stowe’s best-selling novel Uncle Tom’s Cabin. This preceded the era of mass-media advertising, and an arresting window display really was enough to draw shoppers and enhance sales. A gimmick was born.

North of Macy’s along Sixth Avenue, a chic mercantile district was beginning to take shape. Eventually known as “Ladies’ Mile,” it was convenient to lower Fifth Avenue’s mansions and later to the elevated train. Its department stores—Siegel-Cooper, Arnold Constable, Stern Brothers, Lord & Taylor, B. Altman—were enormous. By 1883, the tableaux in those windows as well as Macy’s started to move, first using steam and spring power, and then electric motors. When Lord & Taylor moved up to Fifth Avenue early in the new century, its display-window platforms were on hydraulic lifts so they could be staged in the basement and then raised into place. In the middle of the twentieth century, virtually every American city’s downtown had a department store with such window displays, and a couple of generations brought their children, nostalgically, to see them.

They still do, although most of those downtowns have lost their local department stores as the paired forces of suburbanization and specialty retail (and, after those, Amazon) have hurt the business. New York, being large and still heavy on pedestrian life, has resisted those trends somewhat, but it too has thinned out, gradually losing Best & Company, B. Altman, Bonwit Teller, Stern’s, Ohrbach’s, Abraham & Straus, and Gimbels as the twentieth century drew to a close. A second wave, in the late 2010s, took down Barneys and Lord & Taylor. The family December outing now has four long-running destinations: Saks Fifth Avenue, Bloomingdale’s, Bergdorf Goodman, and, of course, Macy’s.

Every chemical element on the periodic table—that is, each of the 94 irreducible natural substances that make up the universe, plus about twenty-four that have been coaxed briefly into existence in laboratories—has variant forms. They’re called isotopes, and they differ by the number of uncharged particles, called neutrons, in their atomic nuclei. Some isotopes are unstable and emit radiation as they decay into other materials; others last more or less indefinitely.

There were only a couple of known isotopes by the 1920s, barely two decades after the era of nuclear physics began. In 1929, Harold Urey, a chemist at Columbia University, remarked to a Berkeley chemist, who had been involved with the discovery of two oxygen isotopes, that the only more important discovery in the field would be a hydrogen isotope. He continued to think about that, and, in July 1931, published a paper in the Physical Review that suggested a method involving mass spectroscopy that would determine whether such a substance existed. A few months later, he had it cold, and he published his study in April 1932, naming the substance “deuterium” for its neutron-proton nucleus, double the weight of the more common hydrogen one. (It’s informally called “heavy hydrogen.”) Two years later, he received the Nobel Prize in chemistry.

Why does this matter? Broadly, Urey’s research increased our knowledge of the structure of the atom, leading to many other discoveries (including tritium, a third hydrogen isotope, isolated at Cambridge University shortly thereafter). More specifically, deuterium is useful in medicine as a tracer that allows scans to follow reactions. But its future is more intriguing: One of the great hopes of humanity rests on the workability of fusion power, the alternative method of nuclear-energy generation that produces little to no radioactive waste. Unlike conventional fission reactors, which are fueled with rare and hard-to-handle enriched uranium, fusion reactors can run on hydrogen isotopes. Deuterium is relatively abundant in the oceans. It is possible to envision a green future in which it, fused with tritium, powers the planet.

Today’s expansive and complex online advertising ecosystem (with the big exception of Facebook) runs on ad exchanges, meaning that all of the web’s ad inventory is basically stored in one bucket, and any advertiser, big or small, can bid on a spot on your browser’s display. That innovation was the brainchild of a little New York company called Right Media, founded by a former employee of the early internet-advertising firm DoubleClick (and a onetime personal trainer) named Mike Walrath. Right Media’s ad exchange was the business model that enabled the growth of the web, allowing any nascent website to sell an ad slot.

As the exchanges evolved, one less desirable consequence was the insatiable appetite for customers’ personal data, which advertisers use to help decide how much to bid for any given set of eyeballs. “The buyer decides, in a computer process, ‘I know who Mike Smith is. I got a cookie on his machine,’ ” said Michael Smith, then the senior vice-president of revenue, platforms, and operations at Hearst Magazines Digital Media. “I know he travels every other week. I have this Singapore Airlines ad. I think his attention is probably worth about two-tenths of a cent right now; that’s what I’m going to bid.’ The exchange permits them to make that decision literally in the instant that the user is waiting for the page to load.” A process that typically involves thousands of companies, including ad servers, data brokers, publishers, and advertisers, takes less than a tenth of a second.

This algorithmic system, the enormous heir to Right Media and DoubleClick, is called programmatic advertising, and it accounted for two-thirds of the global digital display advertising spend by 2019, according to the marketing agency Zenith. At the same time, the explosion in programmatic has triggered a backlash, as the unintended (or unheeded) consequences of a marketplace run by robots become clear. In 2017, YouTube faced a string of scandals as advertisers discovered their ads were running on violent and racist videos, and Procter & Gamble cut over $140 million in digital advertising due to concerns about fake impressions and “brand safety.”

Major publishers are rediscovering the virtues of doing deals with a human touch, while Europe’s General Data Protection Regulation, which heavily restricts user-data collection, is forcing the data-driven ad-tech industry to consolidate. Right Media did not survive. Yahoo bought it and in 2015 finally pulled the plug on the exchange. But the company’s DNA lives on in the New York tech scene—and in the ad that appears next to virtually everything you read online, and in your general loss of privacy in the digital era.

NOTE: Rising from underground New York clubs like the Loft in the early 1970s, where the crowds were racially mixed and largely gay, disco music deployed heavy bass lines, repetitive synths, string sections, and spiky guitars to spread a particular brand of sophisticated hedonism across America. But before the Latin-inflected partner dances of Saturday Night Fever (set in Bay Ridge, Brooklyn), before the midtown celebrity mecca Studio 54, and before the Village People’s campiness hit the heartland, Gloria Gaynor was already on the verge of stardom. In 1974, her cover of the Jackson 5 song “Never Can Say Goodbye” from her debut album reached No. 1 on Billboard’s first-ever dance-disco chart, and her biggest hit, “I Will Survive,” is an unbeatable dance-floor staple to this day. Here, she reflects on the scene during disco’s early days.

When I started doing “Never Can Say Goodbye,” Barry White was really the only person doing disco music. That type of music wasn’t really coming to the fore yet, but discothèques were happening. It was an economic problem: There was a recession, and people didn’t want to go to regular clubs and spend the cover charge. Clubs that used to do cabaret shows were taking out their seating and putting in dance floors. Barry White and I decided we were going to supply places like that with music that was specifically for dancing.

Play Street was the first disco club I performed in. There was the Garage, and Xenon. There’s another place I’m trying to remember—I loved it because from the dressing room on the second floor, you came down a set of winding stairs out of a cloud of smoke and right onto the stage.

My first time performing at Studio 54, I didn’t know they had a catwalk. When I got onto the stage, it was really long and narrow. The only real space to move was on the catwalk. I absolutely loved it. I’m kind of a daredevil. I felt like the queen of disco that night. I did always love dancing. I remember when I was a kid, my mother used to say, “You can’t wash the dishes, you can’t scrub the floor, but you can dance.” Later, I loved watching modern-dance performers, like Gregory Hines.

But more than anything else, disco was about the music itself. It was so upbeat, and it gave people much-needed relief from life itself—from the pressures and concerns of the day. It gave you an opportunity to shake it all off. I always tried to choose songs that were lyrically upbeat so that people walked away with a sense of freedom and release. That’s why disco music, as I’ve often said, is the only type of music ever to bring together people from every nationality, creed, color, and age group.

Later, disco got a reputation for being not that serious. But I think people who heard the music didn’t even realize what it was doing for them. I wish I could tell the people who tried to perpetuate that idea to relax and enjoy it. Why not just chill?

1 Five Rare and Fantastic Disco Records

Chosen by Jeff Ogiba and Michael Polnasek of Black Gold Records

Marta Acuna, “Dance, Dance, Dance” (12-inch single, 1977): “This ethereal cult dance classic was notoriously dismissed by its producer, Patrick Adams. Record collectors passionately disagree.”

Marta Acuna, “Dance, Dance, Dance” (12-inch single, 1977): “This ethereal cult dance classic was notoriously dismissed by its producer, Patrick Adams. Record collectors passionately disagree.”

Donna McGhee, Make It Last Forever (LP, 1978): “The soulful Brooklynite began her career as a gospel singer before creating this treasure. ‘Make It Last Forever’ earnestly whispers McGhee’s sexual innocence as the New York City disco scene was peaking.”

Donna McGhee, Make It Last Forever (LP, 1978): “The soulful Brooklynite began her career as a gospel singer before creating this treasure. ‘Make It Last Forever’ earnestly whispers McGhee’s sexual innocence as the New York City disco scene was peaking.”

Ramsey & Co., “Love Call” (single, 1979): “Mainor Ramsey formed Ramsey & Co. with the purpose of playing some fun local New York gigs, but in the process, he recorded what would become an impossibly rare party great.”

Ramsey & Co., “Love Call” (single, 1979): “Mainor Ramsey formed Ramsey & Co. with the purpose of playing some fun local New York gigs, but in the process, he recorded what would become an impossibly rare party great.”

Loose Joints, “Is It All Over My Face” (12-inch single, 1980): “Recorded by the New York experimental producer Arthur Russell, it hits the beats-per-minute sweet spot of 120, perfect for mixing as it played, which helped it stay on heavy rotation at Manhattan discos like the Loft and the Paradise Garage.”

Loose Joints, “Is It All Over My Face” (12-inch single, 1980): “Recorded by the New York experimental producer Arthur Russell, it hits the beats-per-minute sweet spot of 120, perfect for mixing as it played, which helped it stay on heavy rotation at Manhattan discos like the Loft and the Paradise Garage.”

Jackie Stoudemire, “Invisible Wind” (12-inch single, 1981): “Highly sought after. It still moves most who have the fortune to hear it. A whimsical disco-boogie crossover with angelic female vocals, dreamy strings, and a groovy break.”

Jackie Stoudemire, “Invisible Wind” (12-inch single, 1981): “Highly sought after. It still moves most who have the fortune to hear it. A whimsical disco-boogie crossover with angelic female vocals, dreamy strings, and a groovy break.”

Liquid Liquid, Optimo (12-inch EP, 1983): “As the disco fad was dimming, Liquid Liquid released this EP, which includes the famously sampled track ‘Cavern.’ An uncredited use sent the band’s label, 99 Records, into a lengthy court battle that would bankrupt and dissolve them.”

Liquid Liquid, Optimo (12-inch EP, 1983): “As the disco fad was dimming, Liquid Liquid released this EP, which includes the famously sampled track ‘Cavern.’ An uncredited use sent the band’s label, 99 Records, into a lengthy court battle that would bankrupt and dissolve them.”

As affluent New Yorkers began buying homes in the suburbs after World War II, a recently returned Navy veteran named Eugene Ferkauf realized they were also furnishing those homes at a furious clip. In a walk-up on East 46th Street in 1948, he opened E. J. Korvette, selling discounted luggage, electronics, and appliances at extremely small margins that, in volume, turned out to be a great business. (There is a pervasive and entertaining and entirely incorrect legend that the store’s name was a condensation of “Eight Jewish Korean-War Veterans,” referring to the company’s founding partners. In fact, as Ferkauf repeatedly explained, the E was for Eugene, the J was for his deputy Joe Swillenberg, and the last name was a reference to his Navy service aboard a type of ship known as a corvette.) The success of the first store quickly led Ferkauf to expand it to a small chain with five locations in Manhattan staffed with a bunch of his buddies from Brooklyn’s Tilden High School.

In 1953, Ferkauf opened a much larger store in Carle Place, Long Island. It was the first of the retailers we now call big-box stores, with piles of consumer goods that beat every traditional competitor on price. In 1962, Korvette’s was doing $400 million in annual business with profits well over 20 percent. By 1966, the company had more than 100 stores, and Ferkauf sold his share for $20 million. Korvette’s remained a retail powerhouse into the 1970s, after which competition from the likes of Kmart plus some poor management decisions drove it out of business. Its DNA remains intact, however, in at least one immense descendant: In 1960, the Arkansas retailer Sam Walton came to New York and took a good close look at the Korvette’s operation, incorporating what he saw into the management of his own nascent company, Wal-Mart.

By a widespread metric, the price of a slice of thin-crust non-artisanal New York pizza roughly keeps pace with the single-ride subway fare (see also PIZZA). As of 2018, the latter was $2.75, and the former was about the same—at most places. In 2008, however, when the fare was two bucks, a slice joint called 2 Bros. Pizza opened on St. Marks Place offering a slice for $1. The response inspired the owners to make the price permanent, and very soon a competitor, 99¢ Fresh Pizza, arose.

There are now more than a dozen such places scattered throughout Manhattan. A lengthy price war between the 2 Bros. outpost on 38th Street and the neighboring Pizza King, in which prices briefly dipped to 75 cents, proved unsustainable. Price aside, the defining characteristics of dollar pizza are that it is okay but not great, the amenities at the restaurants (if you can call them that) are zilch, and for broke folks and drunk students, it’s the best thing going.

2 Grub Street’s Favorite Pizza Slice in New York

Joe’s Pizza (7 Carmine St.): This workaday Greenwich Village shop is the consummate New York slice parlor, first and foremost for its uncanny, unparalleled consistency. This can be attributed to high turnover. Slices fly off the counter, and new pizzas are constantly being baked, guaranteeing freshness. That brings up another essential fact: Joe’s is always busy, but it’s never a pain to get in and get out. The ideal slice joint shouldn’t be a major commitment. Cooked so it’s a few shades shy of burned, the thin crust provides that slightly yeasty tang, bends easily, and has a pudgy, puffy, nicely browned end. The cheese blisters, with occasional golden freckles, and the sauce has the brightness of fresh tomatoes. The sauce and cheese are laid out evenly and in just the right amount so you’re getting the ideal ratio with every bite. It is precisely what your younger self thought all New York slices were like.

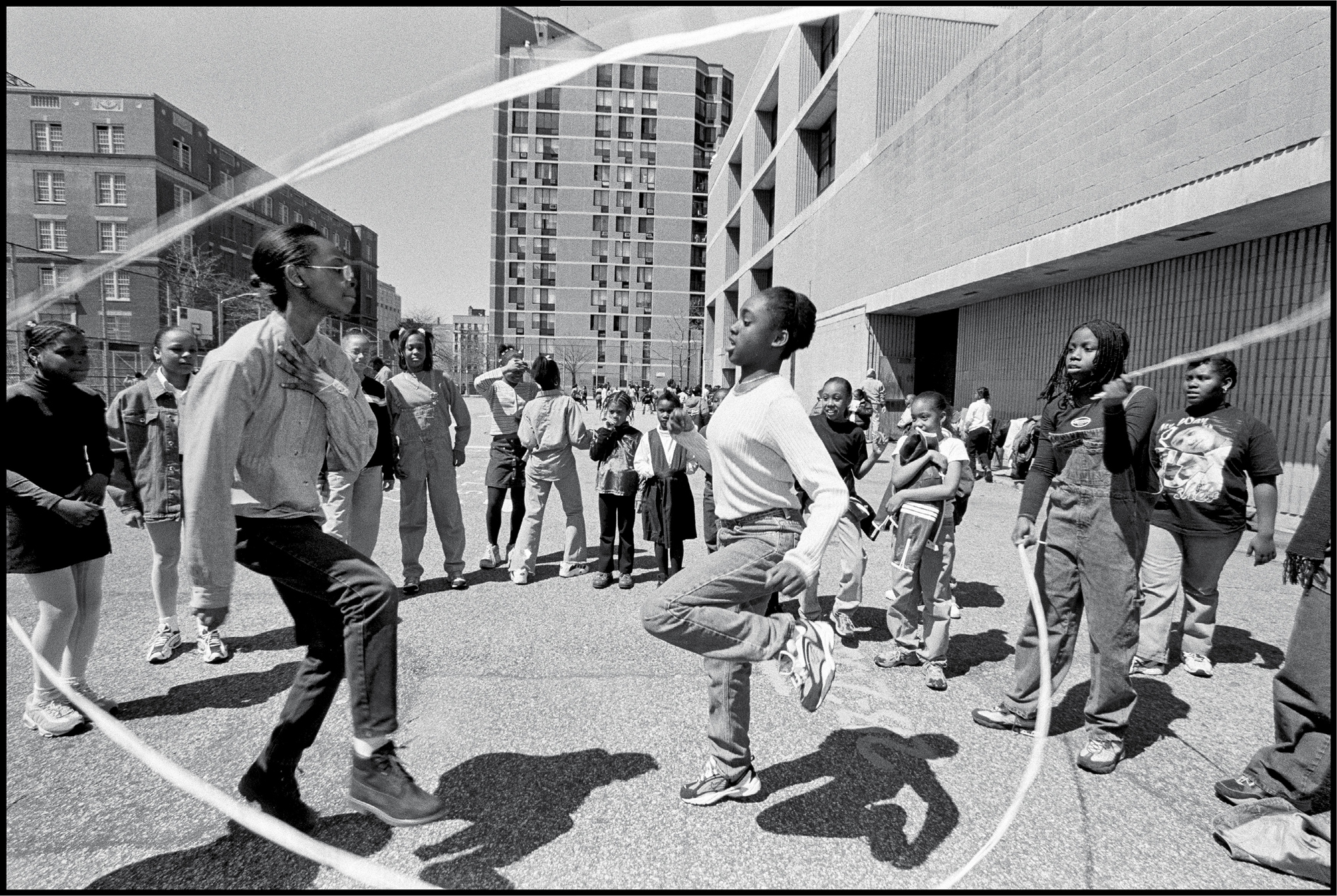

Most histories of double Dutch—the dual-jump-rope style that requires extremely fast footwork and straddles the line between sport and dance—say the game indeed came from Holland, landing in New Amsterdam in the seventeenth century. Its popularity waxed and waned over the next 300 years, as jumping rope, first an activity primarily for boys, shifted to girls. By the early 1970s, double Dutch had nearly gone extinct, along with potsy (a.k.a. hopscotch), ring-a-levio (a hybrid of tag and hide-and-seek), and various other New York street games that faded away under the dual pressures of car traffic and television (see also SKULLY; STICKBALL).

That was when two New York cops, David Walker and Ulysses Williams, had the idea of reinvigorating double Dutch as a community-building youth-outreach gesture. They pulled in some funding through the efforts of radio personality Vy Higginsen, and on Valentine’s Day 1974, 600 mostly African-American middle-schoolers participated in the world’s first double-Dutch tournament. Starting in 1978, a championship team known as the Fantastic Four out of Corlears Junior High School on the Lower East Side became (and remain) cultural ambassadors for the sport, drawing sponsorships and making TV and press appearances.

Today, a pair of leagues founded by Walker (the American Double Dutch League and the National Double Dutch League) and an international group administer championships, some of which have been held on the Lincoln Center plaza and at the Apollo Theater. Although the sport’s home base—and arguably its heart and soul—remains in New York, competitive teams have sprouted up all over the world, notably in France and Japan.

3 How to Step Into a Spinning Double-Dutch Rope

From the Fantastic Four’s Robin Watterson

“The secret to getting in the rope is as soon as that rope goes up above your head, you step in. Whichever foot is close to the rope, that’s the foot you step in on. Say the rope is on your left side, your left foot would be back, your right foot would be forward, like you’re about to run a relay. When the rope in front of you goes up, you step in on that left foot and start jogging, or you can jump with both feet together up and down, in a steady one-two rhythm. Some people are afraid to go in because they’re afraid of the rope. Like, Oh my God, I’m going to get hit. I mean, the ropes may hit you, but I tell a lot of people, they’re not going to kill you.”

Double Dutch in East Harlem, 1998.

PHOTOGRAPH BY BRUCE DAVIDSON

Deep-fried sweetened dough is ancient and cross-cultural, but the history of the doughnut itself has repeatedly circled through New York City. Washington Irving (see also KNICKERBOCKER) claimed that it arrived in America through New Amsterdam, when it was known as the olykoek, or “oil cake.” (The hole came later, reportedly introduced by a mother-and-son pair of cooks in New England.) As a mass-produced, widely available treat, its roots lie in Harlem with Adolph Levitt, a Russian immigrant who in 1920 came up with a machine that formed rings of dough and dropped them into hot fat. He ran it behind a window in his uptown bakery, and crowds gathered to watch it do its thing. By 1931, he’d opened another branch in Times Square. He soon expanded the business into a national chain called Mayflower Coffee Shops, selling not just doughnuts but diner food. It lasted until the 1970s, by which time its competitors, notably Dunkin’ Donuts and Krispy Kreme, had blanketed the country with their little round carb bombs. In the twenty-first century, a small and delicious artisanal-doughnut movement took root in New York, led by the Lower East Side’s Doughnut Plant, which offered intense flavors such as matcha green tea and tres leches. Subsequently, the baker Dominique Ansel introduced a wildly successful addition to the genre, made of multilayered flaky dough via a proprietary secret method (see also CRONUT).

Taking the measure of the stock market with one easy-to-grasp number was the brainstorm of Charles Dow and Edward Jones, who founded their namesake publishing company in 1882 and began to issue a report called the “Customers Afternoon Letter” (which later evolved into The Wall Street Journal). One year into its publication, Dow worked up a running tally of railroad and industrial stocks into a single figure, updated hourly, and called it the Dow Jones Railroad Index. Valuable as it was, it did not reflect the broader stock market, so he decided to do a similar gauge of solely industrial companies’ stock prices. He first issued it on May 26, 1896, and it opened at 40.94. It incorporated the prices of twelve companies’ shares, many of which—U.S. Rubber; National Lead; Tennessee Coal, Iron, and Railroad—reflected the priorities and products of their time.

How the index became shorthand for “the stock market’s performance today” was surely driven by the primacy of Dow Jones and The Wall Street Journal in the financial-news business, especially during the stock boom of the 1920s. At its peak in September 1929, the Dow stood at 381.17. By July 1932, in the deepest trough of the Depression, it was at about 41.

The average was computed hourly by hand into the 1960s, as paper tape with printed prices poured from the stock ticker. Dow Jones legend has it that Arthur “Pop” Harris, the man charged with its computation, constantly suffered from paper cuts. By then, the index had been expanded to 30 companies, and its makeup continues to adapt with the industrial landscape.

In 2012, Dow Jones sold off the business to a joint venture led by Standard & Poor’s, which today administers many such indices. The Dow Jones Industrial Average, explains S&P chief commercial officer Jamie Farmer, is “a bit of an anomaly” among them today because its computation requires no elaborate computer modeling. It’s a pretty simple weighted average, one that could in theory still be calculated with pencil and paper. (That simplicity is maintained in order to ensure consistency across more than a century of data.) What has changed is the economic composition of the lineup, making the term industrial a bit misleading. Today, for every flat-out manufacturer or resource extractor on the roster (Caterpillar, 3M, ExxonMobil), there’s a company like Goldman Sachs or Disney that exists well outside traditional heavy industry. In 2018, the last of the Index’s original twelve companies, General Electric, was removed and replaced with Walgreens.

What uptown means depends on who you are. If you’re Lin-Manuel Miranda, it means Washington Heights. If you were Duke Ellington, it meant Harlem. If you were movin’ on up from Queens like George Jefferson, it meant East 85th Street, where the swells live. If you were a CBGB punk in 1977, it meant “anything above 14th Street, and the hell with all of it—I’m not going.”

Downtown, though, is clear: the dense core of any city, where business is transacted by day and (in the past generation, though not much before that) culture and restaurants and bars come to the fore at night. It’s “down” because Manhattan is a long, skinny island, with office towers and loft spaces at the bottom and brownstones and apartment buildings to the north. There’s no “down” to downtown Detroit or Moscow or Tokyo, unless you want to argue that it’s at a low elevation by the water’s edge. But c’mon—it’s downtown because you take the subway down to Canal Street or Wall Street or Fulton Street.

In the latter part of the twentieth century, downtown took on a secondary meaning: the parts of the city—Greenwich Village, Soho, Tribeca, the East Village, the Lower East Side—where creativity was allowed to flourish, where things were cooler. Broadway theater was played under a proscenium arch and perhaps had a spangly kickline; downtown theater was done on the cheap, in a little black box, and was weird and arty. Uptown restaurants had white tablecloths and prime cuts; downtown restaurants had unlisted numbers and menus full of offal or specialties from one particular region of China or molecular-gastronomy bizarreness. This uptown-downtown distinction has, today, begun to blur to the point of unrecognizableness, as the ostensibly artier districts downtown are today hardly younger and no less bourgeois or cheaper than uptown ones. Most of the genuine cool down there has been priced out and has resettled across the river. (See also “BROOKLYN.”)

“Letters patent being granted under the Great Seal of the United States of America unto Thomas L. Jennings, Tailor, 64 Nassau Street, New York”—thus ran a line in the New York Post of March 27, 1821. This was most likely the first U.S. patent issued to an African-American (the first few years of the country’s patent documentation is thin), and it was for a system of “Dry Scouring Clothes, and Woollen Fabrics in general, so that they keep their original shape, and have the polish and appearance of new.” We’d call it “dry cleaning” today, and Jennings’s advertisement says the technique “also removes stains from cloth.” Jennings was a free man, but his wife, born in slavery, was an indentured servant; he made enough money off his invention to buy her freedom. Their daughter Elizabeth Jennings Graham came to prominence as a very early civil-rights activist. In 1854, she was put off a streetcar by the conductor because of her race, and she sued and won, beginning the integration of the city’s mass transit system and prefiguring the Montgomery bus boycott of a century later.