Fasting is a scary thought to some people. Food is deemed important for all kinds of reasons other than raw hunger. What’s that line I keep seeing painted on restaurant walls and on websites: food is love? Fasting means no food, for hours on end (although at least half of the hours are spent asleep).

In the 2002 remake of the movie Swept Away, Madonna’s character talks about the virtues of fasting, and that line is supposed to make you hate fasting, because she’s promoting it, and her character is a snarling, narcissistic plutocrat. But fasting is virtuous, from a symbolic, religious, and ethical standpoint, and there’s even good scientific evidence that a modified form of this practice, called intermittent fasting, is quite healthy.

Note

People fast for lots of reasons: in solidarity with groups that are suffering persecution, for instance, such as the thousands of displaced people in the Darfur region of Africa (see http://fastdarfur.org). As for religion, in Judaism, for example, the Yom Kippur fast lasts 25 hours. During the Muslim Ramadan tradition, the fast takes place from dawn to dusk each day.

Here comes that human-evolution angle again—we seem to be naturally evolved for fasting. Humans and mammals in general respond metabolically very well to it (see the sidebars covering the science behind fasting). This adaptation may have evolved from our ancestors’ activity patterns. They had to constantly physically seek food, and must have periodically dealt with extreme swings in food availability (see the discussion in the sidebar An Interview with a Scientist on Fasting and Metabolism and this 2004 Journal of Applied Physiology article: http://jap.physiology.org/content/96/1/3.full).

It has become increasingly evident that we’re actually designed to periodically fast.

Intermittent fasting is a hot topic, particularly among weightlifters and resistance trainers.

An intermittent fast is a short-term fast (usually lasting a part of a day) that you include in your lifestyle throughout the week. It’s a part of the whole matrix viewed as your fitness routine, taking place alongside the various modes of exercise and rest periods that are dispersed throughout a training regimen.

Intermittent fasts are good for your metabolic health, increasing the burning of fats for energy, improving insulin sensitivity, lowering inflammation, and increasing growth hormone levels (while fasting). Its proponents even advocate undertaking an occasional training session while fasted.

Intermittent fasts represent a shift of traditional thinking among athletes and coaches. For decades, athletes have experimented with various overfeeding strategies for fueling exercise (such as carbo loading, uncommonly high protein intakes, and even heroic images of Rocky Balboa guzzling down a dozen eggs).

Note

From the “don’t try this at home” file: as Chapter 4 (on micronutrients) points out, excess consumption of raw egg whites can cause a severe vitamin B7 (biotin) deficiency, because of avidin, a protein in egg whites that binds with biotin and prevents its absorption.

There are no hard and fast rules on how to implement an intermittent fast, and later in this chapter we provide a few tips on getting started.

For the most part, during intermittent fasting, you only fast during one chunk of the day (such as when you’re sleeping plus a few hours), and you can even start out initiating an intermittent fast during just one or two days of the week.

Some people respond well to sticking with a specific intermittent fasting protocol that is part of a bigger fitness routine, usually with an experienced trainer/athlete behind it and with the help of books or a website. Some examples of these are:

The “Fast Five,” or 19/5, a setup that involves fasting for 19 hours every day, then eating whenever hungry for 5 hours: www.fast-5.com.

Leangains (www.leangains.com), a 16/8 setup with additional protocols for training and eating.

Alternate day fasts (ADFs) that involve fasting for a full 24 hours and eating an unrestricted (within reason...) amount of calories the following day. One variation of ADF is “Eat Stop Eat,” which was invented by Brad Polin, a sports trainer who wrote a book of the same name.

Note

Interestingly, the fasting benefits tend to accrue with ADF even if the total amount of calories consumed is no different than what people used to eat before they went the ADF route (e.g., no fasting, three meals a day). See the sidebar What the Studies Say About Fasting.

Most fitness geeks have plenty of leeway for determining the type of fasting that works best for them.

You probably want to give intermittent fasting a try. At the very least, it provides a default choice in the face of any confusion about whether what you are eating is counterproductive or not: “When in doubt, don’t eat.” Here’s how to get started:

Map out a day where you can go at least about 14 hours without solid food (water, tea, and black coffee are okay). This usually involves the period after you’ve finished dinner and then throughout the night. But you can use whatever setup is easiest to implement, given your life schedule. The actual time blocks depend on your personal work and sleep routine, of course.

The fast cannot usually involve any calories (unless you’re doing a partial fast); this would disrupt the fasting metabolism (in which your blood-sugar or glucose levels are maintained without the input of food—see the sidebar What Happens in Your Body During Fasting). Tea or coffee without cream or sugar is generally okay, but a purist might insist on no caffeine, which exerts a powerful effect on the central nervous system (thus, you could argue, changing the hormonal milieu for the fast). Most of us have to work or have responsibilities during most fasts, so a little coffee or green tea during the intermittent fast is a reasonable compromise and poses no harm.

Upon awakening, in the usual fasted evening scenario, you skip breakfast and, if so inclined, start the day only with a cup of joe or tea. As we mentioned, a lump of sugar and big splash of cream in the coffee will tend to send the food signal to the body, in part by raising insulin levels, so that’s generally considered a “cheat,” or you might consider this a partial or moderate fast.

Note

The USDA Nutrient Database does indicate that tea and even black coffee are not 100 percent calorie-free (two calories per eight ounces, in fact). An intermittent fasting purist may insist on only water or reliably calorie-free drinks during the fast, but we might be splitting hairs a bit too finely here. You’ll still be getting some of the metabolic benefits of fasting by restricting calories a lot.

The science also supports a fasted workout. Therefore, the next step would be to hit the gym hungry for your favorite high-intensity weight regimen. To many beginner and veteran athletes, this might seem counterintuitive, even scary, but it actually feels good and the athlete tends to adapt to lifting weights on just sleep, water, and coffee (in my case). What is the science? For one, a 2010 study in the Journal of Physiology took three groups of young men and fed them a high-fat, high-calorie diet for more than a month. They divided them into three groups: one group fasted and trained (four times a week cycling); another group trained on carbohydrate fuels, like a high-carb breakfast followed by energy drinks during exercise; and the third (control) group did nothing. The control group gained about seven pounds in six weeks, predictably. The carb-fed group gained about three pounds, but the athletes training in the fasted state didn’t gain any weight, even when they were pigging out around the training and fasting. Among the fasters, several biomarkers improved at a higher rate than in the carb group, including insulin sensitivity and the muscle adaptations for quickly turning over the increased fatty acids in the diet.7 For more intermittent fasting–related study results, see the sidebar What the Studies Say About Fasting.

You can also do endurance training in the fasted state (this was actually the training protocol for two of the fasting studies we cite in this chapter). This appears on the face of it, and from my experience as a former endurance athlete when I usually stuffed food like gels or bananas in my pocket, to be much harder to do when fasting than short-term high-intensity weight training. After 80 minutes of, say, hard riding, you could bonk, and there are good physiological reasons for that, such as because all the glycogen—your internal storage depot of starch in the muscles and liver—has been depleted by the fasting and exercise itself. It does depend on the intensity level of the exercise, and how well you have previously adapted to fasting. You could also save this kind of training for the nonfasting days, unless you’re very adapted to it.

Or, you don’t have to train; you’ll still enjoy some of the benefits of intermittent fasting.

When you’re taking part in regular intermittent fasts (essentially, every day), you have narrowed your window for eating. You might only eat in an 8-hour window during the day (fasting for 16 hours). There are good reasons why some of the prescriptive intermittent fasting regimes are based on this narrowing of the eating window. You take advantage of all the benefits of fasting (e.g., better blood-sugar control, more fat burning, higher glucagon and growth hormone), and you can eat based on hunger level whenever you want during the window.

Chances are, this eating in a narrower window means you only eat two meals a day, but they can be big meals that include supplements (like a whey protein shake) if you’re actually trying to put on muscle. Other people will simply eat fewer calories without breakfast and lose extra pounds. After fasting and exercising, you should break the fast within about an hour and eat. Eat quality protein, like branched-chain amino acids (BCAAs), now that you’ve started the muscle-building process by fasting and lifting weights. There is also evidence that fasting preferentially catabolizes (uses for energy) the BCAAs the body harvests from muscles,8 so it makes sense to restore them with quality whey protein (which contains BCAAs) or meat afterward.

The rest of your meal, which is likely to contain some carbohydrate (veggies, fruits, rice, potatoes, bread, etc.), will quickly replenish the liver glycogen, since the body preferentially refills that glucose-storage depot once it’s been depleted.

Eating in blocks and windows after a fast also prevents other kinds of bad habits, like the unnecessary night eating (because you ate during the day), or constant snack-eating, which we’re not designed for. Middle-of-the-night eating is notorious for generating unneeded body fat; if you stop eating at 7:30 PM and initiate even a minimal fast of 12 hours each night (eating again at 7:30 AM), watch for the probable difference it will make in cutting unnecessary fat and in how you feel.

Fasting might not be a good idea if you’re taking medication and/or struggling with a chronic medical issue, so make sure to consult a physician in these circumstances before you try intermittent fasting. Because of the difficulty of making wise choices while being saturated with unhealthy pop-culture images of celebrities whose bodies have been augmented by Photoshop, fasting may also not be a good idea for young men and women who might seek weight loss as a goal, as opposed to metabolic improvements.

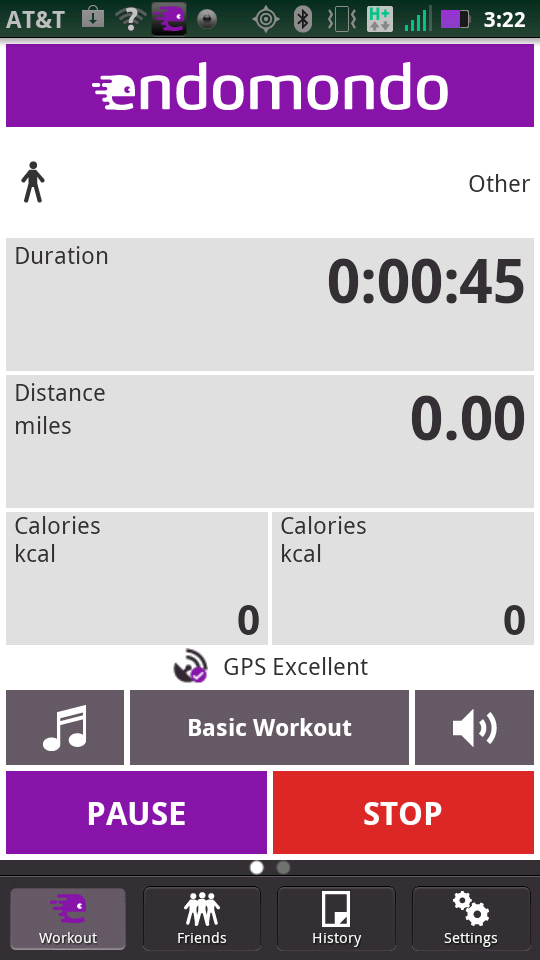

You can use any digital timer to show you how long you’ve fasted (or you could just look at your watch). For example, you can use the Endomondo app with an unspecified fitness category of “other,” as shown in Figure 6-1 (we talked about this app for measuring sports fitness training in Chapter 2).

An iPhone App named IF Timer is also available, but I haven’t used it yet (Apple user, alas, with Android smartphone). Check it out at http://itunes.apple.com/us/app/if-timer/id414565808?mt=8&ign-mpt=uo%3D4.

The Fitbit gives you a pretty good picture of how many calories you’ve burned during the fast (we also discuss this device—a pedometer with a website—in Chapter 2). I’m not too sure how useful that is, as “calories in, calories out” is probably a crude measure of what’s happening physiologically during a fast (and your weight will be affected by how well you’re hydrating during the fast, among other things).

At any rate, while I’m not privy to the algorithm the Fitbit software uses, the calorie calculation probably goes something like this: your basal metabolic rate (say, 70 calories per hour for me) x number of hours of fast + extra calories expended by activity (say 300 calories, during a 4.5-mile walk on the beach).

Note

Your basal metabolic rate (BMR) represents how many calories you expend to maintain internal physical systems in the absence of additional activity—say, if you laid on the couch all day.

So, given the latter equation and a 16-hour fast, the fast would have expended or “cost” about (16 x 70 + 300), or roughly 1,420 calories. This gives you an idea of how much you should be eating during the chow-down window, to replenish your body and even add lean mass (in that case, you probably should eat more than the fast expended).