Chapter 35

Cyclic Nucleotide-Gated Ion Channels

Chapter Outline

I Summary

Cyclic nucleotide-gated (CNG) channels are directly activated by the binding of cGMP and/or cAMP, which are controlled by G-protein enzyme cascades. Their cousins, the hyperpolarization-activated, cyclic nucleotide-gated (HCN) channels, are voltage-gated, but their voltage sensitivity is regulated by the binding of cAMP. Both CNG and HCN channels are members of the superfamily of voltage-gated cation channels. CNG channels have established roles in sensory transduction, but they are also found in many non-sensory tissues. HCN channels are best known for their pacemaking role in the cardiac sinoatrial node. Both CNG and HCN channels are excitatory, since their opening allows Na+ and Ca2+ entry. In the brain, both CNG and HCN channels are implicated in synaptic plasticity and other excitation processes, in addition to their pacemaking role in rhythmic neurons. There continues to be fast-moving research on these channels in the areas of structure/function, physiological roles, modulation, gating, permeation and development of pharmacological tools.

II Introduction

Cyclic nucleotides have long been known as intracellular second messengers that regulate cell function by controlling the activity of protein kinases which, in turn, control many other cellular proteins. However, in 1985, Fesenko and his colleagues made a startling discovery that changed our view of the physiological role of cyclic nucleotides. These investigators found that the ion channel mediating the electrical response to light in retinal rod cells was directly opened by the binding of guanosine 3′,5′-cyclic monophosphate (cGMP); no phosphorylation reaction was required. Now the rod channel is considered to be a member of a special class of ion channels – the cyclic nucleotide-gated (CNG) channels, which are actually part of the superfamily of voltage-gated cation channels (reviewed in Yu et al., 2005). These channels are discussed in many recent reviews (Kaupp and Seifert, 2002; Barnstable et al., 2004; Broillet and Firestein, 2004; Bradley et al., 2005; Hofmann et al., 2005; Craven and Zagotta, 2006; Pifferi et al., 2006; Biel, 2009; Biel and Michalakis, 2009; Mazzolini et al., 2010; Cukkemane et al., 2011).

Since the discovery of CNG channels, a related class of ion channels has been found to underlie pacemaker currents (usually referred to as Ih or If) in the heart and brain (reviewed in Gauss and Seifert, 2000; Kaupp and Seifert, 2001; Craven and Zagotta, 2006; Biel, 2009; Wahl-Schott and Biel, 2009; DiFrancesco, 2010). These channels are called HCN channels, which stands for hyperpolarization-activated, cyclic nucleotide-regulated channels. Their structure is similar to that of CNG channels, but they are mainly gated by voltage, with their voltage activation regulated by the direct binding of cyclic nucleotides. This chapter will focus mainly on CNG channels, but will make comparisons with HCN channels as well. Finally, although cyclic nucleotide binding domains have been found in Eag-like (ether à-go-go) K+ channels and plant K+ channels, the functional role of cyclic nucleotide binding to these channels remains under investigation and these channels will not be discussed here.

Why would Nature directly gate or regulate ion channels with cyclic nucleotides? When a cyclic nucleotide regulates a kinase, it is also in effect regulating all the proteins controlled by that kinase and by substrates of the kinase. Regulating ion channels is similar in that, like kinases, ion channels have diverse physiological effects. For example, the opening of non-selective cation channels (such as those opened by cyclic nucleotides) depolarizes the cell membrane (via Na+ entry) and also allows the entry of Ca2+, another important second messenger. Membrane depolarization opens voltage-gated Ca2+ channels, further increasing the entry of Ca2+. Many cell functions are controlled by membrane potential and/or intracellular Ca2+, including nerve impulses, muscle contraction, gene transcription and the secretion of neurotransmitters and hormones. Finally, depolarization and intracellular Ca2+ open K+ channels, which repolarize the membrane and thereby contribute to the termination of the cellular response. Thus, there are numerous possibilities for control of cell function by cyclic nucleotide-gated, and cyclic nucleotide-regulated, ion channels. In addition, ion channel gating and permeation are much faster than phosphorylation reactions. Thus, changes in cyclic nucleotide levels could have fast effects mediated by ion channels, followed by slower, longer lasting effects mediated by protein kinases.

III Physiological Roles and Locations

Since their discovery in retinal rods, and their subsequent purification and cloning, CNG channels have been identified in many other types of cells. They have been implicated generally in sensory transduction, as they also have been found in retinal cones, olfactory cells, invertebrate photoreceptors and pineal gland cells (reviewed in Kaupp and Seifert, 2002). Furthermore, mRNA probes against the rod CNG channel have revealed its expression in cells of the heart, brain, muscle, liver, kidney and testis. In the brain, both CNG and HCN channels have been implicated in synaptic plasticity (reviewed in Barnstaple et al., 2004, Biel, 2009; Wahl-Schott and Biel, 2009). The CNG channels have been studied most thoroughly in vertebrate photoreceptors and olfactory cells and, therefore, the CNG channels from these cells are discussed in the most detail here.

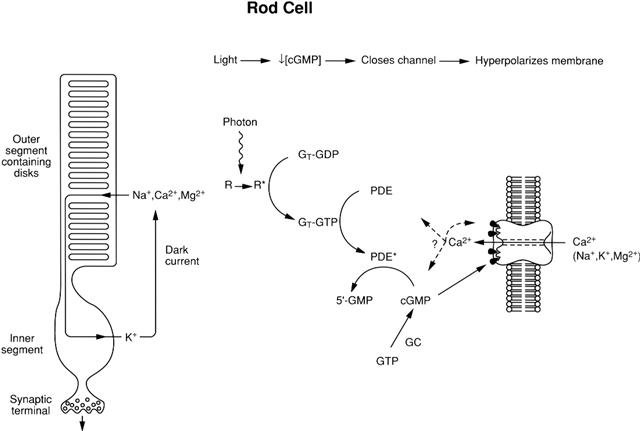

In rods and cones, CNG channels are key players in visual transduction (discussed in Chapter 38). It is these channels that conduct the so-called dark current and whose closure generates the hyperpolarizing response to light, which decreases the secretion of glutamate onto bipolar cells at the rod–bipolar synapse. The physiological second messenger in the photoreceptors is cGMP, which is at relatively high cytosolic concentration in the dark and decreases in the light after hydrolysis by a phosphodiesterase (PDE). Activation of PDE occurs when a photon is absorbed by a G-protein-coupled-receptor (a GPCR, which in this case is the photopigment rhodopsin), which then triggers a G-protein cascade. A similar system operates in cone visual transduction. An overview of the enzyme cascade controlling the level of cGMP is given in the next section, with more detail provided in Chapter 38.

Rods and cones are particularly well suited to patch-clamp studies of CNG channels, since the plasma membranes of their light-sensitive outer segments contain no other type of ion channel (although Na+:Ca2+,K+ exchange carriers are present; see Section V and Chapter 38). Furthermore, the rod outer segment plasma membrane has an extremely high density of CNG channels – hundreds per square micrometer – allowing as much as nanoamperes of current to be recorded from a single excised patch (with blocking divalent cations removed; see Section VB below). Such large currents are especially useful in studying pharmacological agents and modulators. In contrast, cone outer segments have relatively low channel densities, allowing the study of single-channel kinetics in patches containing only one channel. However, rods and cones actually have about the same total number of CNG channels because of the much larger plasma membrane area in cone outer segments (a consequence of the characteristic infolding of this membrane that forms “sacs” rather than the internal “disks” found in rods; see Chapter 38).

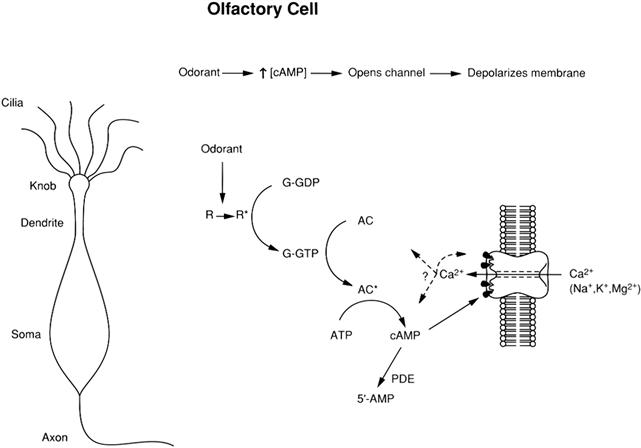

Olfactory receptor cells use CNG channels in sensing odorants (reviewed in Chapter 39). In this system, however, there are numerous odorant-activated GPCR types. Furthermore, adenosine 3′,5′-cyclic monophosphate (cAMP) is the physiological second messenger and the stimulus triggers cAMP production by adenylate cyclase, rather than its degradation by a PDE. Thus, in response to an odorant, the CNG channels open and the olfactory receptor cell depolarizes, increasing the probability of generation of an action potential. In addition, the Ca2+ that enters through the CNG channels activates Ca2+-activated Cl− channels, whose opening further depolarizes the cell (note that for these cells, unlike most other cells, the Cl− concentration is higher inside than outside the cell, which is why its flow through the channels depolarizes the cell).

Like rods and cones, the olfactory cell has its CNG channels concentrated in a specialized region: the olfactory cilia and ciliary knob. Although the channels have been studied in excised patches from olfactory cilia (Nakamura and Gold, 1987), such experiments are extremely difficult because of the small diameter of a cilium. Luckily, the knob is larger and some CNG channels are also located (at lower density) in the membrane of the soma. Furthermore, whole-cell patch-clamp methods have yielded considerable information on the olfactory CNG channels.

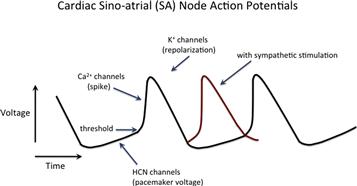

HCN channels were first studied in the sinoatrial (SA) node of the heart, where their opening produces the pacemaker current (Ih) that sets the heart rate by giving the initial slow depolarization at the beginning of the SA node action potential (Fig. 35.1; reviewed in DiFrancesco, 2010). Since the initial studies, HCN channels have been found in many other tissues as well, most notably in the brain, where they appear to play a role in synaptic plasticity, dendritic integration and maintenance of resting membrane potential (reviewed in Biel, 2009; Wahl-Schott and Biel, 2009). HCN channels also have been found to play a role in rhythmic activity in the central nervous system, especially in the thalamus (reviewed in Gauss and Seifert, 2000).

FIGURE 35.1 The role of HCN channels in the cardiac SA node action potential. The HCN channels are activated by hyperpolarization at the end of an action potential and their opening causes a slow depolarization that drives the membrane potential to threshold to trigger the next spike. Voltage-gated Ca2+ channels are responsible for the upstroke and voltage-gated K+ channels repolarize the membrane. The inward pacemaker current through HCN channels is called Ih or If and is carried mainly by Na+ under physiological conditions, despite the relatively high K+ selectivity of HCN channels. Red trace: sympathetic agonists (e.g. norepinephrine) speed the heart by increasing the concentration of cAMP, which makes the HCN channels open more quickly (increased slope of pacemaker depolarization) and at less negative voltages, so that the next spike occurs sooner.

IV Control by Cyclic Nucleotide Enzyme Cascades

Like cyclic nucleotide-regulated protein kinases, CNG and HCN channels are sensors of the local concentration of cyclic nucleotides. Stimulus-induced changes in cyclic nucleotide levels are mediated by GTP-binding proteins (G proteins). The stimulus-activated receptor interacts with a G protein, causing it to release GDP and bind GTP and to dissociate into two components: an α subunit and a βγ subunit complex. The α subunit of the G protein, now bound to GTP, stimulates either adenylate cyclase (in olfactory receptors and cardiac SA node cells) or a cGMP-specific phosphodiesterase (in rods and cones). For the photoreceptors, the stimulus that activates the receptor is a photon, whereas for olfactory cells, the stimulus is an odorant molecule that acts as a receptor ligand, and for the SA node cells, the typical stimulus is a sympathetic agonist (e.g. norepinephrine) acting on a β-adrenergic receptor. A cyclic nucleotide enzyme cascade is diagrammed in Fig. 35.2 for a rod photoreceptor and in Fig. 35.3 for an olfactory cell. The cascade in cones is similar to that in rods, except that all the membrane-associated players are located on the plasma membrane, since cones lack internal disks (see Chapter 38). For the cardiac SA node cells, the cascade resembles that of the olfactory cell, however, cAMP does not activate the HCN channel, but rather makes the channel’s activation by voltage occur sooner (i.e. at less negative voltages) and more quickly. This gives a speeding of the heart, since the SA node action potentials that set the timing of the heartbeat come more frequently. Activation of a muscarinic receptor by a parasympathetic agonist decreases [cAMP] and thereby slows the heart.

FIGURE 35.2 The cyclic nucleotide cascade controlling CNG channels in rods. R, R∗, rhodopsin in its inactive and active forms, respectively. GT, G protein (“Transducin”), bound to either GDP or GTP. PDE, PDE∗, phosphodiesterase in its inactive and active forms, respectively. GC, guanylate cyclase. Calcium ions entering through the CNG channels are thought to modulate the function of several players in the cascade, including the channels themselves. A similar cascade operates in cones.

FIGURE 35.3 The cyclic nucleotide cascade controlling CNG channels in olfactory cells. R, R∗, odorant receptor in its inactive and active (odorant-bound) forms, respectively. G, G protein, bound to either GDP or GTP. AC, AC∗, adenylate cyclase in its inactive and active forms, respectively. PDE, phosphodiesterase. Here, as in photoreceptors, entering Ca2+ appears to modulate the cascade, including the CNG channels. The Ca2+ that enters through the CNG channels also opens Ca2+-activated Cl− channels (not shown), which further depolarize the cell.

Cyclic nucleotide enzyme cascades are not fixed in their behavior. Instead, they are regulated by feedback systems, some of which involve CNG channels. For example, in rods, the Ca2+ that enters through CNG channels has been found to modulate the cGMP cascade. There is evidence that Ca2+ (in association with Ca2+ binding proteins) inhibits guanylate cyclase and inhibits the shutoff of rhodopsin (see Chapter 38). In olfactory receptors, Ca2+ appears to be involved in both excitation and adaptation (reviewed in Pifferi et al., 2006 and Chapter 39).

In addition to such feedback regulatory systems, there are the standard shutoff mechanisms employed in cyclic nucleotide cascades (e.g. see Chapter 38). These include phosphorylation of the receptor (e.g. the phosphorylation of rhodopsin, followed by its binding to arrestin), GTPase activity of the G protein (converting it back to the GDP-bound, inactive form), cessation of the stimulus and competing hydrolysis or synthesis of the cyclic nucleotide. There also are hints that the ability of the channels to respond to the cyclic nucleotide may be modulated (see Section VI).

V Functional Properties

VA Channel Gating

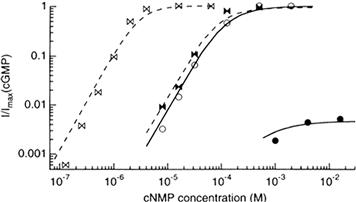

CNG channels are very sensitive detectors of the local concentration of cyclic nucleotides and they appear designed to work in the physiological concentration range of their respective agonists. Dose-response curves (e.g. Fig. 35.4) for activation of rod channels by cGMP give half-saturating concentrations (K1/2 values) ranging from about 5 to 100 μM, which is within the expected physiological concentration range. The rather wide range of values of K1/2 may reflect functional modulation of the channels by other factors (see Section VI).

FIGURE 35.4 Dose–response curves for activation of cloned rod (circles) and olfactory (bows) α-homomultimeric channels. Both CNG channels show a higher apparent affinity (lower K1/2) for cGMP (open symbols) than for cAMP (filled symbols), but for the rod channel cAMP appears to be a partial agonist, giving only a fraction of the current produced by a saturating concentration of cGMP. The smooth and dashed curves were calculated using a model in which the only difference between the results with cGMP and those with cAMP is that cGMP more effectively triggers the opening conformational change of the channels after it is bound. Currents were measured in response to voltage pulses of +100 mV from a holding potential of 0 mV and normalized to the current obtained in saturating cGMP (Imax). (Reproduced with permission from Gordon and Zagotta, 1995. Copyright 1995 Cell Press.)

The form of the dose–response curve is well-described by the Hill equation:

where r is the response to cGMP (e.g. the cGMP-activated component of the membrane current measured in a patch-clamp experiment), rmax is the maximum response (obtained with a saturating concentration of cGMP to activate all channels in the patch) and n is the Hill coefficient. Reported Hill coefficients have ranged between about 1.5 and 4, suggesting that several molecules of cGMP typically bind to each channel to open it. As discussed later, a channel seems to consist of four subunits, each with a cyclic nucleotide binding site (reviewed in Bradley et al., 2005; Craven and Zagotta, 2006; Biel, 2009). Because the dose–response curve for channel activation is so steep, small changes in the concentration of cAMP or cGMP produce very large changes in channel open probability. Furthermore, unlike most ligand-gated ion channels, CNG channels do not desensitize in the continued presence of agonist (reviewed in Mazzolini et al., 2010).

Activation of olfactory CNG channels is similar to that of rod and cone channels except for relative cyclic nucleotide sensitivities and efficacies. Rod and cone channels are much less sensitive to cAMP than to cGMP, with a K1/2 for activation by cAMP of about 1.5 mM. Native olfactory CNG channels are more sensitive to both cyclic nucleotides than are photoreceptor channels, but they are only two to five times more sensitive to cGMP than to cAMP, with most K1/2 values for activation by cGMP in the range of 1 to 5 μM (and a few as high as 20 μM; see Nakamura and Gold, 1987). Furthermore, cAMP acts as only a partial agonist for the rod channel: even at saturating concentrations, it gives only a fraction of the open probability obtained with saturating cGMP (see Fig. 35.4). However, both cAMP and cGMP are full agonists for the olfactory channel. This difference in agonist efficacy can be explained by assuming that cGMP is a more effective agonist than cAMP for both channels, and that after agonist binding, the olfactory channel opens more easily than does the rod channel (i.e. the olfactory channel’s opening conformational change is more energetically favored) (Gordon and Zagotta, 1995). Interestingly, HCN channels prefer cAMP to cGMP by about a factor of ten (reviewed in Craven and Zagotta, 2006).

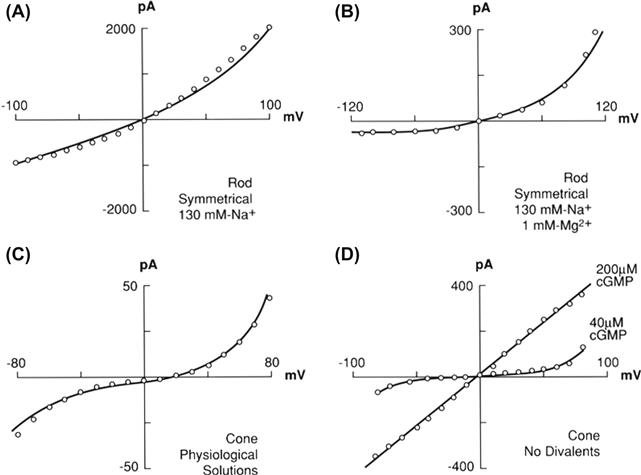

Although some voltage-activated channels (e.g. HCN and Eag-like K+ channels) are regulated by cyclic nucleotides, channels that are primarily activated by cyclic nucleotides (CNG channels) are only weakly voltage dependent, with no voltage-dependent inactivation. In current–voltage (I-V) relations from excised patches, the voltage dependence of CNG channel gating is most obvious at low cyclic nucleotide concentrations, where it introduces significant non-linearity (e.g. see Fig. 35.7D). High concentrations of cyclic nucleotides overcome the voltage dependence of gating, driving the channels (by mass action) toward high open probabilities at all voltages and linearizing the I-V curves. Note, however, that much of the CNG channel rectification seen in intact cells probably results from voltage-dependent channel block by Ca2+ and Mg2+, as discussed in Section VB below. The end result of both forms of non-linearity is that current is relatively independent of voltage in the physiological voltage range (for rods and cones, this would be about −40 to −80 mV). Thus, sensory CNG channels are able to transduce their stimulus faithfully in the face of changes in membrane potential that originate at either the transducing region or elsewhere in the cell, where there are many kinds of voltage-dependent ion channels.

FIGURE 35.5 Single-channel recordings of CNG channels in native rod outer segment membranes demonstrate such rapid gating kinetics that many open-shut transitions are poorly resolved. Channel openings give downward deflections; holding potential −148 mV. Left: cell attached patch from toad rod outer segment; the bottom trace was obtained in a saturating light and all others in darkness. To prevent channel block, the pipette was filled with a solution lacking Ca2+ and Mg2+. Right: the same patch after excision, with the intracellular surface bathed in either no cGMP (bottom trace) or 10 μM cGMP (all other traces); both pipette and bathing solutions lacked Ca2+ and Mg2+. (Reproduced with permission from Matthews and Watanabe, 1987.)

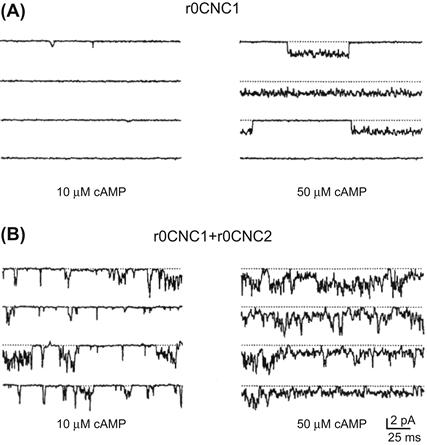

FIGURE 35.6 Increased cAMP sensitivity and flickery gating produced by co-expressing the second olfactory CNG channel subunit (r0CNC2; now called CNGA4) with the first (r0CNC1; now called CNGA2). When the first subunit is expressed alone (A) there are very few channel openings in 10 μM cAMP and the openings with 50 μM cAMP are much less flickery than those seen in (B), where both subunits are expressed in the same cell. Holding potential is −80 mV. (Reproduced with permission from Liman and Buck, 1994. Copyright 1994 Cell Press.)

FIGURE 35.7 Current-voltage relations for photoreceptor cyclic GMP-activated currents from multichannel, excised patches. (A) The rod CNG channel relation is almost linear with saturating [cGMP] and no divalent cations. Olfactory CNG channels demonstrate a similar relation (not shown). (B) The addition of millimolar Mg2+ to both sides of the membrane gives strong outward rectification. Similar outward rectification has been reported for olfactory CNG channels. (C) Cone CNG channels show both outward and inward rectification in the presences of physiological (millimolar) levels of Mg2+ and Ca2+. (D) The I-V relation for cone CNG channels is approximately linear with saturating [cGMP] and no divalent cations (top curve). Decreasing [cGMP] produces a non-linear I-V relation (bottom curve), because gating is slightly voltage dependent. Voltage-dependent gating of rod CNG channels also produces a very non-linear I-V relation [resembling that in (B)] in the absence of divalent cations, at low [cGMP]. (Redrawn with permission from Zimmerman and Baylor, 1992 (A) and (B); from Nature, Haynes and Yau, 1985, Copyright 1985 Macmillan Magazines Limited (C); and Picones and Korenbrot, 1992 (D) Reproduced from The Journal of General Physiology, 1992, 100, 647–673, by copyright permission of The Rockefeller University Press.)

Since CNG channels have voltage-sensing S4 segments, it is surprising that they have only very weak voltage sensitivity. It has been proposed that glutamate residues in the vicinity of S4 contribute negative charges that may neutralize the effects of the positively-charged arginine and lysine residues of S4 that are thought to confer voltage sensitivity to the channel (Wohlfart et al., 1992; Tang and Papazian, 1997). Perhaps even more surprising is the fact that HCN channels, which also have S4 regions, have a voltage dependence that is the opposite of that found in most other voltage-dependent channels – HCN channels are activated by hyperpolarization, rather than by depolarization. Like CNG channels, most HCN channels do not inactivate with voltage. The one known exception is the spHCN channel from sea urchin sperm, which inactivates in the absence of cAMP (reviewed in Kaupp and Seifert, 2002; Hofmann et al., 2005; Craven and Zagotta, 2006; Biel and Michalakis, 2009).

Single-channel studies demonstrate that CNG channels have particularly fast open-shut transitions in the native membrane. This flickery behavior is striking in the cell-attached and excised-patch recordings obtained from toad rods by Matthews and Watanabe (1987) (Fig. 35.5). However, when purified and reconstituted, or cloned and heterologously expressed, the channels were initially found to have much slower gating kinetics that are more typical of many other ion channels. Although Ca2+ and Mg2+ produce flicker block of these channels, the flickery gating behavior persists even in the absence of these ions. Furthermore, the transitions are too fast to reflect the binding and unbinding of cyclic nucleotides and they also apparently do not simply reflect block by protons. Accumulated evidence suggests that the flickery gating pattern of the native rod CNG channel results partly from the presence of a second channel subunit that was missing in the original reconstitution and expression studies, in which only one kind of subunit was identified (see Section VI below). This additional subunit also gives the channel its characteristic sensitivity to L-cis-diltiazem. Unlike the α subunit, the β subunit (also called subunit 2) does not produce cyclic nucleotide-activated currents when expressed alone.

For the olfactory channel, a second subunit (CNGA4, previously called r0CNC2) not only gives more flickery gating kinetics, but also increases the apparent affinity for cyclic nucleotides, giving more channel activity at low cyclic nucleotide concentrations (Fig. 35.6) (Bradley et al., 1994; Linman and Buck, 1994). Like the rod β subunit, this subunit also does not appear to produce cyclic nucleotide-activated currents when expressed alone. However, it is possible to obtain currents by treating the channel with nitric oxide (reviewed in Broillet and Firestein, 2004). With both rod and olfactory CNG channels, there still seem to be discrepancies between the behavior of the channels in vivo and in expression systems. Some of these differences may result from effects of channel modulators (see Section VI).

Although there remains disagreement over the detailed mechanism of activation (reviewed in Craven and Zagotta, 2006), it is clear that CNG channels can open with fewer than four ligands bound, but have highest open probabilities with all four sites occupied. Some studies suggest that a channel gate resides with the pore, at or near the selectivity filter (Karpen et al., 1993; Contreras et al., 2008). Certain mutations in this region switch the channel from ligand gated to voltage gated (Martinez-Francois et al., 2009). Innovative methods have been very useful in dissecting the molecular mechanism of gating. These include: covalent activation (reviewed in Kaupp and Seifert, 2002), polymer-linked cGMP dimers (reviewed in Brown et al., 2006), chimeras of different channel types (e.g. Gordon and Zagotta, 1995) and the use of modulatory substances, such as Ni2+, to discern subunit interactions (reviewed in Kaupp and Seifert, 2002).

The cyclic nucleotide binding domain (CNBD) in HCN channels is thought to function as an autoinhibitory domain, causing the channel to require relatively large negative voltages to activate (reviewed in Biel, 2009; Wahl-Schott and Biel, 2009). The binding of cAMP to the CNBD relieves that inhibition, allowing the channel to open at less negative voltages. The binding of cAMP also accelerates channel opening, leading to a steeper upstroke in the SA node action potential. Another function of cAMP in the SA node cells is activation of cAMP-dependent protein kinase, which phosphorylates voltage-dependent Ca2+ channels, facilitating their opening and further contributing to the increased frequency of SA node action potentials.

VB Permeation, Selectivity and Block

CNG channels are relatively non-selective cation channels with no significant anion permeability. Thus, reversal potentials for most CNG channels studied under normal ionic conditions are about +5 to +20 mV. The monovalent alkali cation permeability sequence for the rod channel has been reported to be Li+ ≥ Na+ ≥ K+ ≥ Rb+ ≥ Cs+ and Ca2+ and Mg2+ ions appear to be more permeant than the monovalent cations (reviewed in Kaupp and Seifert, 2002).

Cone and olfactory CNG channels also poorly discriminate among monovalent alkali cations, although their exact permeability sequences and ratios are not identical to those of the rod CNG channel. Strict comparisons are difficult because there is some variability in reported permeability ratios for each channel type. Relative permeabilities obtained may depend on whether the channels are studied in the intact cell, in excised patches, or in reconstitution or expression systems. The permeabilities may also depend on intracellular factors controlling functional modulation of the channels (see Section VI). In intact rods, the relative currents carried by monovalent and divalent cations have been found to depend on the concentration of cGMP (reviewed in Kaupp and Seifert, 2002). This finding, along with the dependence of subconductance states on cGMP (see below), suggests that the functional properties of CNG channels may change with the number of ligand molecules bound. If so, this may reflect a very interesting feature of these channels and one with tremendous potential for modifying physiological responses.

HCN channels differ from CNG channels in being significantly more selective for K+ over Na+ and having much lower Ca2+ permeability. Consistent with this high K+ selectivity, the pore of an HCN channel contains the amino acid sequence, GYG (glycine-tyrosine-glycine) that is the hallmark of K+-selective channels. Nevertheless, under physiological conditions (i.e. physiological concentration gradients and membrane potential), the main ion flowing through these channels is Na+. Thus, under normal conditions, the opening of HCN channels, like that of CNG channels, produces a membrane depolarization.

Under physiological conditions, the rod CNG channel is occupied by Ca2+ or Mg2+ most of the time and these ions prevent the passage of Na+ and K+, which pass through the pore much more rapidly. Thus, these divalent cations behave as “permeant blockers”. As a result of the very slow transport rate of the divalent cations, the mean single-channel conductance is extremely low – only about 0.1 pS in rods studied under physiological conditions. The channels can be blocked from either side but, under physiological conditions, they are mostly blocked by extracellular Ca2+ and Mg2+. To resolve single-channel currents, one must reduce the concentration of divalent cations to the micromolar range. In the absence of divalent cations, the single-channel conductance is as high as tens of picosiemens. The extremely low single-channel conductance in physiological solutions gives an excellent signal-to-noise ratio for photon detection by rods, since the random openings and closings of individual channels produce only very tiny fluctuations in the dark current. The absorption of a single photon elicits the closure of hundreds of channels, giving a smooth, stereotypical waveform. If all those channels had single-channel conductances in the range of tens of picosiemens, the rod cell would have to contend with the consequences of a huge influx of Na+ and Ca2+. Cones and olfactory cells would have a similar problem, since their transducing regions also contain many CNG channels.

In the absence of divalent cations, I-V relations for CNG channels (with saturating cyclic nucleotide concentrations) are linear or nearly so (Fig. 35.7A and D, upper curve). Divalent cations introduce extreme non-linearity in the I-V relations (Fig. 35.7B and C). When the rod channel is studied in the presence of physiological concentrations of divalent cations, its I-V relation is very outwardly rectified. Although some of this rectification is a consequence of the weak voltage dependence of channel gating described earlier, much of it results from channel block by Ca2+ and Mg2+. Thus, at negative membrane potentials in the physiological range (about −40 to −80 mV), external Ca2+ and Mg2+ are drawn into the pore, reducing Na+ entry and giving an approximately flat I-V relation over a wide range of voltage. This very low, voltage-independent conductance in the physiological voltage range allows light-triggered outer segment voltage changes to travel relatively unattenuated to the inner segment to regulate synaptic transmission and also prevents the outer segment photon-sensing mechanism from fluctuating with voltage.

I-V relations of the olfactory channel, with and without divalent cations, are essentially indistinguishable from those of the rod channel, but surprisingly, the I-V relation for the cone channel is rather different. Whereas cone I-V curves from excised patches are linear in the absence of divalent cations, they are almost S-shaped when divalents are present (see Fig. 35.7C). Although the functional significance of this difference between cone CNG channels and those in rod cells and olfactory receptors is not clear, structurally, it may reflect a different location of the dominant ion-binding site within the cone channel. At subsaturating concentrations of cyclic nucleotides (which are closer to the physiological concentrations), the cone channel I-V relation is much more flat in the physiological range of membrane potential even in the absence of divalent cations (see Fig. 35.7D, lower curve). Similarly, the rod channel I-V curve shows increasing outward rectification as the cGMP concentration is lowered (not shown).

Single-channel recordings of the rod CNG channel in the absence of divalent cations have revealed at least two conductance states: one of about 25 to 30 pS and the other with a conductance about one-third as large. However, it has been suggested that the channel has at least one more, and perhaps many more, conductance levels. Because of the extremely rapid gating kinetics of this channel, numerous open-closed transitions are no doubt unresolved in the single-channel records. Thus, it is difficult to determine the exact number of distinct conductance states. It is also not clear whether these states are characterized by truly different ion transport rates or merely by different (incompletely resolved) open times, giving the appearance of different conductance levels. In the absence of divalent cations, the olfactory and cone CNG channels demonstrate major single-channel conductances around 45 to 50 pS, also with apparent subconductance states. Some results suggest a switching of the rod CNG channel from low to high conductance states with increasing ligand occupancy (reviewed in Kaupp and Seifert, 2002). The single-channel conductance of HCN channels is currently unresolved because there is a wide range of reported values – from 1 to 30 picoseimens. This large variability probably reflects variation in recording methods and types of cellular preparations (reviewed in Wahl-Schott and Biel, 2009).

Many pharmacological agents have been tested on CNG and HCN channels. Since CNG channels have a strong affinity for Ca2+, various calcium channel blockers, such as verapamil and diltiazem, have been tested. Most block only weakly or not at all, but a few (e.g. L-cis-diltiazem and an amiloride analogue, 3′,4′-dichlorobenzamil) have been found to block effectively from the cytoplasmic surface of the membrane, with Ki values in the micromolar range. CNG channels also have been found to be blocked by a variety of other pharmacological agents (reviewed in Brown et al., 2006), but none have been found to bind with sufficient affinity and specificity. This also has been true for pharmacological agents against HCN channels, where the focus often has been K+ channel blockers.

VI Molecular Structure

Although CNG channels are ligand-gated channels, their molecular structures place them in the superfamily of voltage-gated cation channels, along with the HCN channels. The members of this family are characterized by a repeating structural motif, like that shown in Fig. 35.8, containing six putative membrane-spanning segments, located between the hydrophilic N- and C-terminal regions that project into the cytosol. Also characteristic of these channels is a putative pore region (P-region) and an S4 transmembrane segment that contains many basic residues and is thought to be a voltage-sensing region. Of course, the channel region that best distinguishes CNG and HCN channels from a typical voltage-gated cation channel is the C-terminal cyclic nucleotide binding domain (CNBD), which resembles that found in other cyclic nucleotide-regulated proteins (e.g. cGMP-dependent protein kinase). A region often referred to as the C-linker, that connects the CNBD with the last transmembrane segment (S6), has been proposed functionally to link the cyclic nucleotide binding event to the allosteric opening transition of the channel (reviewed in Craven and Zagotta, 2006).

FIGURE 35.8 A model for the general organization of a CNG or HCN channel subunit. The model is based on information from many studies. Like typical voltage-gated K+ channel subunits, CNG channels are characterized by intracellular N- and C-termini, six transmembrane segments (S1–S6) and a region called the P-loop that lies between S5 and S6 and forms the selectivity filter through which ions pass. Cyclic nucleotide monophosphates, like cAMP and cGMP, bind in the cyclic nucleotide binding domain (CNBD) of the intracellular C-terminus. The C-linker region is thought to connect cyclic nucleotide binding at the CNBD to the allosteric opening transition involving movement of S6.

When the first subunit of the bovine rod CNG channel was cloned, the channel was proposed to consist of multiple identical subunits, each with a cGMP-binding site located in the C-terminal region. It now seems clear that the rod channel is a tetramer consisting of α and β subunits (CNGA1 and CNGB1, respectively; reviewed in Hofmann et al., 2005) and that there is a variety of other subunits that can associate to form functional CNG channels. The following subunit types have been identified in vertebrates: CNGA1, CNGA2, CNGA3, CNGA4, CNGA5, CNGB1 and CNGB3. The most recent addition to the list is CNGA5, which so far has only been found in the brain and pituitary of the zebrafish (Tetreault et al., 2006; Kahn et al., 2010). Functional homomeric channels can be made from all α subunits except CNGA4, but not from any β subunits. The subunit stoichiometry that has been proposed for rod, cone and olfactory CNG channels is as follows: in rods, three CNGA1s and one CNGB1; in cones, two CNGA3s and two CNGB3s; and in olfactory receptor cells, two CNGA2s, one CNGA4 and one CNGB1b (an alternatively spliced variant of CNGB1) (reviewed in Zimmerman, 2002; Bradley et al., 2005). Subunit stoichiometry and order remain to be determined for CNG channels in other cell types.

The known vertebrate HCN subunit types are HCN1, HCN2, HCN3 and HCN4. Each type has been found to form functional homomeric channels. Although some combinations have been identified in specific tissues and species (e.g. the rabbit heart SA node contains heteromeric channels that consist of HCN1 and HCN4), the subunit stoichiometries and arrangements have not been determined in any preparation. Outside the vertebrate world, an interesting HCN channel from sea urchin sperm (spHCN) has unusual gating properties that have provided some recent insights into voltage-dependent activation of HCN channels (reviewed in Wahl-Schott and Biel, 2009).

In addition to having two types of subunits, the rod CNG channel is part of a larger molecular complex. The rod β subunit (CNGB1) contains a very long glutamic acid-rich peptide (GARP) near its N-terminus. This GARP region connects with structural molecules on the rod cell’s disk rims (see Chapter 38), giving it a potential role not only in channel function, but also in the structural stability and development of the rod cell and its internal disks. Free GARP molecules also have been found to inhibit the rod CNG channel (Michalakis et al., 2011). Furthermore, the rod CNG channel α subunits (CNGA1s) are tightly associated with Na+:Ca2+,K+ exchange carriers (see Chapter 38). The nature of the interactions of the rod CNG channel with these other molecules, and their functional consequences, are still under investigation.

There are currently no available crystal structures of an entire CNG or HCN channel. However, the CNBD has been crystallized for HCN2 and for a bacterial CNG channel, MloK1 (Zagotta et al., 2003; Schünke et al., 2011; reviewed in Craven and Zagotta, 2006). Although these structures have provided important information, numerous structural questions remain to be answered for both CNG and HCN channels, especially since crystal structures are static and since the CNBDs in those structures were disconnected from other channel regions. For example, despite extensive structure–function research, we still know only a few of the molecular details regarding interactions between subunits and between N- and C-terminal domains. In olfactory CNG channels, the latter interaction seems to be autoexcitatory and is disrupted by Ca2+-calmodulin, which strongly inhibits channel opening (reviewed in Trudeau and Zagotta, 2003). It is also not known why the rod CNG α subunit is post-translationally cleaved in vivo, so that before its insertion into the rod membrane its molecular weight is reduced from 78 kilodaltons to 63 kilodaltons, with the loss of the end of its N-terminal tail (reviewed in Kaupp and Seifert, 2002). It also is not known exactly what structural changes occur in converting the binding of cyclic nucleotide at the C-terminus to the opening of the channel, how the selectivity filter is involved in this, or how the action of channel modulators (see following) is structurally linked to changes in channel gating. Finally, the nature of the regulation of HCN channels by cyclic nucleotides remains a mystery: although all HCN subunits have CNBDs, cAMP has a large effect on HCN2 and HCN4, but very little effect on HCN1 and HCN3. Mutational studies suggest this difference may be explained by the presence or absence of some type of “silencing” region outside the CNBD (reviewed in Wahl-Schott and Biel, 2009).

VII Functional Modulation

New information suggests that CNG channels may be modulated in ways that are only beginning to be elucidated. As mentioned above, there are hints that the ionic selectivity of the rod CNG channel may vary with the amount of cyclic nucleotide bound. There is also now evidence that the cGMP sensitivity of the rod channel may be tuned up or down by phosphorylation and reduced by calmodulin in the presence of Ca2+ (reviewed in Kaupp and Seifert, 2002). It has not been determined whether other channel properties are also altered by these modulators. Protons modulate the rod CNG channel, increasing its open probability, while reducing its single-channel conductance (Gavazzo et al., 1997). Transition metal divalent cations, such as Ni2+, also modulate CNG channel gating (reviewed in Kaupp and Seifert, 2002); interestingly, 10 μM Ni2+ increases the open probability of the rod channel, but decreases the open probability of the olfactory channel. Higher concentrations of Ni2+ block the pores of both rod and olfactory channels. Finally, there is mounting evidence that, in rods, the CNG channel interacts with Na+:Ca2+,K+ exchange carriers (see Chapter 38). The detailed functional significance of this interaction remains to be determined but, at the very least, it would allow the Ca2+ that enters through the CNG channels to be expelled more rapidly than if this tight association did not exist. Functional modulation of the rod CNG channel may help explain the large variability in reported cGMP affinity and cooperativity and may play a role in some aspects of visual transduction.

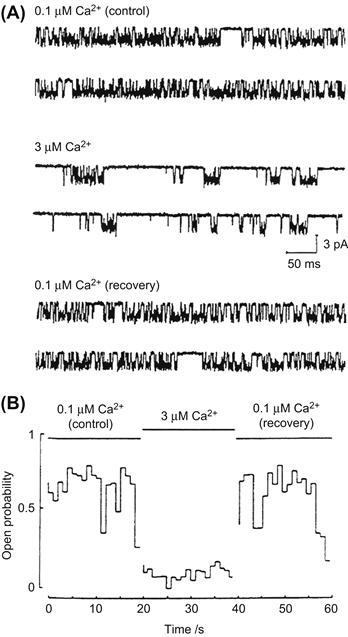

The gating of olfactory CNG channels has been found to be dramatically modulated by intracellular Ca2+. Fig. 35.9 (Zufall et al., 1991) shows single-channel recordings obtained from an excised patch of olfactory dendritic membrane. When the concentration of Ca2+ bathing the intracellular surface of the patch was increased from 0.1 to 3 μM, there was a striking increase in channel closed time, giving a decrease in open probability. This modulation also has been found to involve calmodulin and, possibly, an endogenous Ca2+ binding protein distinct from calmodulin (reviewed in Pifferi et al., 2006 and Chapter 39). Research on cloned olfactory CNG channels suggests this inhibition results from disruption of an autoexcitatory interaction between the channel’s N- and C-termini (reviewed in Trudeau and Zagotta, 2003).

FIGURE 35.9 Modulation of an olfactory CNG channel by Ca2+. Raising the Ca2+ concentration from 0.1 to 3 μM at the intracellular surface of an excised patch produced a reversible increase in channel closed time, resulting in a decrease in channel open probability. The cAMP concentration was 100 μM and the holding potential was −60 mV. Channel opening gives a downward deflection in current. (Reproduced with permission from Zufall et al., 1991.)

HCN channels have been found to be modulated by a variety of factors, including protons, phosphoinositides, phosphorylation enzymes and Cl−. These channels also appear to be regulated by interactions with a variety of proteins, including scaffolding proteins and other auxiliary proteins. Evidence suggests that such functional regulation of HCN occurs within elaborate intracellular molecular complexes (reviewed in Wahl-Schott and Biel, 2009).

BIBLIOGRAPHY

1. Barnstable CJ, Wei JY, Han MH. Modulation of synaptic function by cGMP and cGMP-gated cation channels. Neurochem Int. 2004;45:875–884.

2. Biel M. Cyclic nucleotide-regulated cation channels. J Biol Chem. 2009;284:9017–9021.

3. Biel M, Michalakis S. Cyclic nucleotide-gated channels. Handb Exp Pharmacol. 2009;191:111–136.

4. Bradley J, Li J, Davidson N, Lester HA, Zinn K. Heteromeric olfactory cyclic nucleotide-gated channels: α subunit that confers increased sensitivity to cAMP. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1994;91:8890–8894.

5. Bradley J, Reisert J, Frings S. Regulation of cyclic nucleotide-gated channels. Curr Opin Neurobiol. 2005;15:343–349.

6. Broillet M-C, Firestein S. Cyclic nucleotide-gated channels: multiple isoforms, multiple roles. Adv Mol Cell Biol. 2004;32:251–267.

7. Brown RL, Strassmaier T, Brady JD, Karpen JW. The pharmacology of cyclic nucleotide-gated channels: emerging from the darkness. Curr Pharm Des. 2006;12:3597–3613.

8. Contreras JE, Srikumar D, Holmgren M. Gating at the selectivity filter in cyclic nucleotide-gated channels. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2008;105:3310–3314.

9. Craven KB, Zagotta WN. CNG and HCN channels: two peas, one pod. Annu Rev Physiol. 2006;68:375–401.

10. Cukkemane A, Seifert R, Kaupp UB. Cooperative and uncooperative cyclic-nucleotide-gated ion channels. Trends Biochem Sci. 2011;36:55–64.

11. DiFrancesco D. The role of the funny current in pacemaker activity. Circ Res. 2010;106:434–446.

12. Fesenko EE, Kolesnikov SS, Lyubarsky AL. Induction by cyclic GMP of cationic conductance in plasma membrane of retinal rod outer segment. Nature. 1985;313:310–313.

13. Gauss R, Seifert R. Pacemaker oscillations in heart and brain: a key role for hyperpolarization-activated cation channels. Chronobiol Int. 2000;17:453–469.

14. Gavazzo P, Picco C, Menini A. Mechanisms of modulation by internal protons of cyclic nucleotide-gated channels cloned from sensory receptor cells. Proc Biol Sci. 1997;264:1157–1165.

15. Gordon SE, Zagotta WN. Localization of regions affecting an allosteric transition in cyclic nucleotide-activated channels. Neuron. 1995;14:857–864.

16. Haynes L, Yau K-W. Cyclic GMP-sensitive conductance in outer segment membrane of catfish cones. Nature. 1985;317:61–64.

17. Hofmann F, Biel M, Kaupp UB. International Union of Pharmacology LI Nomenclature and structure-function relationships of cyclic nucleotide-regulated channels. Pharm Rev. 2005;57:455–462.

18. Karpen JW, Brown RL, Stryer L, Baylor DA. Interactions between divalent cations and the gating machinery of cyclic GMP-activated channels in salamander retinal rods. J Gen Physiol. 1993;101:1–25.

19. Kaupp UB, Seifert R. Molecular diversity of pacemaker ion channels. Annu Rev Physiol. 2001;63:235–257.

20. Kaupp UB, Seifert R. Cyclic nucleotide-gated ion channels. Physiol Rev. 2002;82:769–824.

21. Khan S, Perry C, Tetreault ML, et al. A novel cyclic nucleotide-gated ion channel enriched in synaptic terminals of isotocin neurons in zebrafish brain and pituitary. Neuroscience. 2010;165:79–89.

22. Liman ER, Buck LB. A second subunit of the olfactory cyclic nucleotide-gated channel confers high sensitivity to cAMP. Neuron. 1994;13:611–621.

23. Martínez-François JR, Xu Y, Lu Z. Mutations reveal voltage gating of CNGA1 channels in saturating cGMP. J Gen Physiol. 2009;134:151–164.

24. Matthews G, Watanabe S-I. Properties of ion channels closed by light and opened by guanosine 3′5′-cyclic monophosphate in toad retinal rods. J Physiol. 1987;389:691–715.

25. Mazzolini M, Marchesi A, Giorgetti A, Torre V. Gating in CNGA1 channels. Pflügers Arch Eur J Physiol. 2010;459:547–555.

26. Michalakis S, Zong X, Becirovic E, et al. The glutamic acid-rich protein is a gating inhibitor of cyclic nucleotide-gated channels. J Neurosci. 2011;31:133–141.

27. Nakamura T, Gold GH. A cyclic nuceotide-gated conductance in olfactory receptor cilia. Nature. 1987;325:442–444.

28. Picones A, Korenbrot JI. Permeation and interaction of monovalent cations with the cGMP-gated channel of cone photoreceptors. J Gen Physiol. 1992;100:647–673.

29. Pifferi S, Boccaccio A, Menini A. Cyclic nucleotide-gated ion channels in sensory transducion. FEBS Lett. 2006;580:2853–2859.

30. Schünke S, Stoldt M, Novak K, Kaupp UB, Willbold D. Solution structure of the Mesorhizobium loti K1 channel cyclic nucleotide-binding domain in complex with cAMP. EMBO Rep. 2011;10:729–735.

31. Tang CY, Papazian DM. Transfer of voltage independence from a rat olfactory channel to the Drosophila ether-a-go-go K+ channel. J Gen Physiol. 1997;109:301–311.

32. Tetreault ML, Henry D, Horrigan DM, Matthews G, Zimmerman AL. Characterization of a novel cyclic nucleotide-gated channel from zebrafish brain. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2006;348:441–449.

33. Trudeau MC, Zagotta WN. Calcium/calmodulin modulation of olfactory and rod cyclic nucleotide-gated ion channels. J Biol Chem. 2003;278:18705–18708.

34. Wahl-Schott C, Biel M. HCN channels: structure, cellular regulation and physiological function. Cell Mol Life Sci. 2009;66:470–494.

35. Wohlfart P, Haase W, Molday RS, Cook NJ. Antibodies against synthetic peptides used to determine the topology and site of glycosylation of the cGMP-gated channel from bovine rod photoreceptors. J Biol Chem. 1992;267:644–648.

36. Yu FH, Yarov-Yarovoy V, Gutman GA, Catterall WA. Overview of molecular relationships in the voltage-gated ion channel superfamily. Pharmacol Rev. 2005;57:387–395.

37. Zagotta WN, Olivier NB, Black KD, Young EC, Olson R, Gouaux E. Structural basis for modulation and agonist specificity of HCN pacemaker channels. Nature. 2003;425:200–205.

38. Zimmerman AL. Two B or not two B? Questioning the rotational symmetry of tetrameric ion channels. Neuron. 2002;36:997–999.

39. Zimmerman AL, Baylor DA. Cation interactions within the cyclic GMP-activated channel of retinal rods from the tiger salamander. J Physiol. 1992;449:759–783.

40. Zufall F, Shepherd GM, Firestein S. Inhibition of the olfactory cyclic nucleotide gated ion channel by intracellular calcium. Proc R Soc London Ser B. 1991;246:225–230.