Chapter 36

Sensory Receptors and Mechanotransduction

Chapter Outline

IV. Information Transmission by Sensory Receptors

VI. Experimental Mechanoreceptor Preparations

VII. Steps in Mechanoreception

I Introduction

While most living cells can detect and respond to a variety of changes in their external physical and chemical environments, we usually reserve the term sensory receptor for those cells that transmit information about such changes to the animal’s nervous system. Even this classification must be qualified. For example, the heart and other hollow organs have localized, mainly autonomous, nervous systems that allow sensory receptors to produce very local functional changes. Moreover, some of the mechanisms that cells use to detect external events seem to be very similar as we move from unicellular animals to the complex sensory organs of humans. With these caveats in mind, this chapter is restricted to those cells (usually neurons) that transmit sensory information into one or more divisions of the central nervous system.

Several general principles can be applied to all sensory receptors. The concept of modality means that each sensory cell transmits information about only one type of environmental stimulus. Photoreceptors detect light but are insensitive to touch, while stretch receptors do not respond to odorant molecules. Within the modalities there are further specializations, so that cold temperature receptors do not respond to hot stimuli and sweet taste receptors do not respond to bitter substances. Each type of receptor seems to produce specific molecular machinery for detecting just one type of stimulus. An exception to this rule is provided by the cutaneous polymodal pain receptors (McGlone and Reilly, 2009) which respond to mechanical, thermal or chemical stimuli.

Neurons carrying information into the nervous system form labeled lines that signal specific modalities and specific locations. Artificially stimulating a sensory nerve by electrical or mechanical stimulation produces a sensation that reflects the modality and location of the sensory ending, not the artificial stimulus. Another general principle is that the intensity of the stimulus is encoded as the amplitude of the electrical signal passing along the sensory neuron. In most cases, this means the action potentials propagating along the sensory axon, with more action potentials per second representing a stronger stimulus. In some cases, the stimulus produces a decrease in ongoing neuronal activity. However, there are several situations where the primary sensory cell does not produce action potentials at all, but a graded change in membrane potential that is conducted decrementally along the cell. Graded potentials can usually be propagated for only very short distances (a few millimeters at most), so such cells are generally small. Well-known examples are the rods and cones of the retina and the hair cells of the inner ear.

II Sensory Transduction

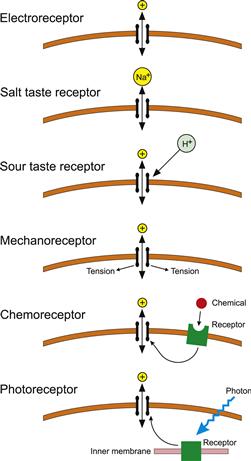

Sensory cells respond to an external stimulus by changing their membrane potential, although several processes may occur before and after this transduction step. This change in membrane potential is called a receptor potential and it is a graded potential, increasing and decreasing with the intensity of the stimulus. Non-sensory neurons are insensitive to external stimuli, such as mechanical stress, temperature or light, unless these reach such intensity as to threaten the cell’s normal function or integrity. Therefore, sensory receptors must have specializations to detect external stimuli (Fig. 36.1). Conceptually, the simplest receptors are the electroreceptors, which use an external electrical current to change their own membrane potential by direct current flow. Although the concept is simple, these cells are highly specialized to maximize their electrical sensitivity. Current flows through resting membranes by the passage of ions through ion channels that are open at rest. The salt taste receptors of the tongue and mouth also rely on direct ion flow through ion channels. In this case, the channels are selective for Na+ and can be blocked by amiloride, so that placing a small amount of amiloride in the mouth removes the ability to taste salt. Na+ diffuses through these channels to depolarize the taste cell membrane. An additional level of complexity is illustrated by sour taste receptors, where cation channels are believed to be closed by external hydrogen ions, reducing outward K+ current and depolarizing the cell. However, the sour taste receptor has not yet been identified.

FIGURE 36.1 Mechanisms of sensory transduction organized by level of complexity. In each case the cell has specialized ion channels that produce a receptor current. Modulation of the current is achieved by changing the electrochemical force for the permeant ion in the cases of electroreceptors and salt taste receptors. In other receptors, the external stimulus changes the channel open probability, either by acting directly on the channel protein or via a second messenger cascade. Chemoreceptors have receptor proteins in the cell membrane. In vertebrate rods, the light-sensitive pigments, rhodopsins are in the internal disk membranes, but cones and invertebrate photoreceptors have their photopigments in invaginated cell membranes.

The fundamental transduction step in mechanoreceptors is not well understood, but is assumed to involve mechanically activated ion channels. These channels are believed to be either directly gated by forces acting on the plasma membrane or by tethers that connect the channel to the cytoskeleton or extracellular matrix (Christensen and Corey, 2007). If either model is true, this is another case where the external stimulus acts directly to open or close an ion channel. Finally, there are cases where the external stimulus acts indirectly through intermediate membrane receptors. In many chemoreceptors, specialized receptor proteins in the outer cell membrane activate ion channels through a second messenger cascade when they bind an appropriate stimulus molecule. In the case of rod photoreceptors, light activates specialized light-sensitive pigments in internal cell membranes, producing a second messenger cascade that eventually closes ion channels in the external membrane. Some models of mechanotransduction also suggest that a conformational change in a distant force-sensing component is communicated to the mechanotransduction channel by a second messenger (Christensen and Corey, 2007). It is not known which types of sensory receptor mechanisms evolved first, but it is clear that several, if not all, of these processes have close parallels in other non-sensory tissues, such as the Na+ channels of epithelia, the mechanically activated channels of muscle and the second messenger cascades of synapses and secretory cells. It seems likely that the evolution of different sense modalities has taken advantage of pre-existing cellular mechanisms.

III Sensory Adaptation

Sensory receptors often have to deal with wide ranges of stimulus amplitudes. Therefore, they need high sensitivity to detect weak stimuli, plus the ability to reduce their sensitivity if the stimulus is strong. In some cases, the maximum sensitivity approaches the limits imposed by physics or chemistry. Human rod photoreceptors and some arthropod photoreceptors can detect single photons arriving in the eye, which is clearly the physical limit. The human ear can detect air movements of about 0.01 nm, close to the diameter of a hydrogen atom (Hudspeth, 2005). In such cases, the sensory cells must amplify the initial signal considerably, which at least partly explains the complex morphologies of human rod photoreceptors and the cochlea.

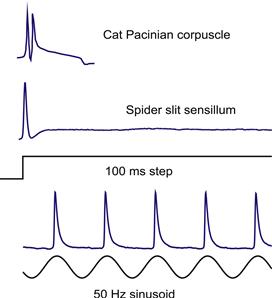

The reduction in sensitivity following an increase in stimulus is called adaptation. It may be seen as a decrease in receptor potential with time during a constant stimulus, or as an increase in the strength of stimulus required to produce a constant response. All sensory receptors adapt to some extent, but there is a wide range of adaptation speeds and amounts. At one extreme are receptors such as Pacinian corpuscles (Loewenstein and Mendelson, 1965) and spider slit sensilla (French et al., 2002), which fire only one or two action potentials with even a strong, continuous stimulus. At the other extreme are Ruffini endings (Malinovsky, 1996), which continue to fire steadily for long periods. The type of adaptation is always appropriate to the function of the receptor. Muscle and joint receptors that signal limb position would not be useful if they adapted to silence in a few seconds, because the sense of limb position, or proprioception, would vanish if one did not keep moving. On the other hand, photoreceptors must function under a wide range of light intensities and it is essential that they can adjust their sensitivity to the ambient light level. The rapid adaptation of Pacinian corpuscles makes them ideally suited for detecting vibration, since a rapidly changing stimulus will repeatedly excite the receptor, while a steady stimulus will produce little response.

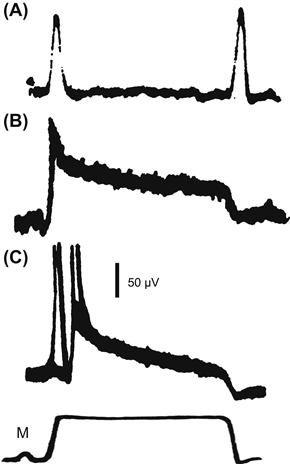

The mechanisms of adaptation vary widely and may occur at different stages of the process. Some involve components outside the sensory cell, such as the mechanical creep of the muscle in muscle spindles or the movements of screening pigments in insect eyes. Others may involve chemical signals within and between cells, as found in photoreceptors and olfactory receptors. Mechanical adaptation by the capsule of the Pacinian corpuscle is very well known from the pioneering work of Loewenstein and Mendelson (1965), who described the dramatic reduction in receptor potential adaptation that can be achieved by removing most of the capsule (Fig. 36.2). Unfortunately, many descriptions stop at this point, leaving the impression that mechanical adaptation dominates Pacinian corpuscle behavior, but Loewenstein and Mendelson showed that, even after decapsulation, the receptor will only fire one or two action potentials in response to a prolonged step stimulus (Fig. 36.2C). They described this as electrical adaptation and it now seems probable that many receptors use voltage- or calcium-activated ion channels in their membranes to produce electrical adaptation by raising the threshold for action potential production. This has been clearly established in several arthropod and vertebrate mechanoreceptors and is likely to occur in other types of receptors that use action potentials to encode the sensory signal (French and Torkkeli, 1994).

FIGURE 36.2 Adaptation in the mammalian Pacinian corpuscle occurs in two stages. (A) Stimulating a normal receptor with a mechanical step (M: bottom) causes rapidly adapting receptor potential responses at the start and end of the step. (B) Removing most of the lamellae surrounding the sensory ending (decapsulation) eliminates most of the adaptation to reveal a slowly adapting receptor potential. (C) Suprathreshold stimulation of a decapsulated receptor still produces only two action potentials, showing that there is rapid adaptation in the conversion of receptor potential to action potentials. (Redrawn from Loewenstein and Mendelson, 1965.)

IV Information Transmission by Sensory Receptors

Nervous systems and individual nerve cells deal with information. Cells with long axons transmit information over considerable distances and we assume that all nerve cells process information to some extent. Unfortunately, it is usually difficult to decide what the nature of the information is and how it is being processed, except in general terms. Sensory cells have been particularly important in trying to understand quantitatively how information is encoded and transmitted by nerve cells because it is usually easier to define the input signal of a receptor neuron than other nerve cells. For example, the intensity and wavelength of light entering a photoreceptor or the length of a muscle spindle receptor can be accurately controlled while the output of the receptor in terms of receptor or action potentials is recorded.

Quantitative investigations of information flowing through sensory neurons have been based on ideas developed by engineers for dealing with artificial communication systems, such as telephone or television signals. Widespread use of digital communications has made the concept of information transmission rate (usually in bits per second, or bps) familiar. If we know the nature of the information being transmitted, we can measure the actual rate of transmission, but even if nothing is known about the kind of information being transmitted, it is possible to calculate the theoretical maximum rate that could be achieved by an optimum encoding scheme. This is called the information capacity of the system and it is closely related to the inherent noise in the system. The basic idea is that inherent noise limits the amplitudes and bandwidths of the signals that can be received unambiguously and thus the amount of information that can be transmitted and received in a given time. Note that when a noisy neuron fires action potentials the noise appears primarily as variability or randomness in the timing of the action potentials.

If a system behaves linearly, its information capacity can be calculated from the signal-to-noise ratio. This approach has been used in most estimates of receptor cell information capacity. Although relatively few measurements have been made, it is clear that cells using action potentials to transmit information have lower information capacities than those that do not. Spiking mechanoreceptors in cricket cercal mechanoreceptors and spider slit sensilla had capacities of 300 bps and 200 bps respectively, compared to values of 1650 bps for fly photoreceptors and 2240 bps for the receptor potential in spider slit sensilla before encoding (Juusola and French, 1997). However, it was possible to transmit information at rates up to 500 bps for short periods using a defined encoding scheme in a cockroach mechanoreceptor (French and Torkkeli, 1998), so we must be cautious about these estimates until we understand the actual encoding schemes that neurons use.

These findings support the concept that nerve cells use action potentials to transmit information faithfully over long distances, but there is a significant cost in information capacity. This probably explains why some sensory systems have elaborate neural structures located peripherally, close to the primary sensory neurons. A familiar example is the vertebrate retina, with two layers of non-spiking cells and complex synaptic interactions before the spiking ganglion cells. This arrangement presumably allows important information processing to take place on the high capacity input from the photoreceptors before it is encoded into the lower capacity ganglion cell axons.

V Mechanoreceptors

VA Vertebrate Mechanoreceptors

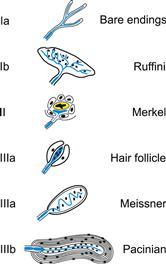

Vertebrate mechanoreceptors have such a wide variety of shapes and functions that classification is difficult. Many receptors bear the names of their original discoverers or re-discoverers, such as Meissner corpuscles and Ruffini endings. A variety of classification schemes have been used, based on features such as the morphology of the sensory ending and its associated tissues, rates of adaptation and location in the body. The hair cells of the vertebrate auditory and vestibular systems have been studied extensively (Hudspeth, 2005; Fettiplace, 2009), and are described in Chapter 37. Mammalian cutaneous mechanoreceptors have their sensory endings in the skin and their cell bodies in the dorsal root or trigeminal ganglion (Tsunozaki and Bautista, 2009). Figure 36.3 shows a classification of these mechanoreceptors according to the embryonic origin of the tissues associated with the sensory ending and the complexity of the sensory ending itself (Malinovsky, 1996). Type I receptors are associated with tissues of mesodermal origin (connective tissues and muscle) and include the Ruffini endings of the joints and skin, the Golgi tendon organs and the muscle spindles. Type II receptors are transitional between type I and type III and are associated with tissues of endodermal or ectodermal origin. They include the Merkel endings, where each sensory ending is closely apposed to a specialized Merkel cell that is derived from epidermal lineage. Type III receptors are clearly associated with tissues of ectodermal origin and comprise a wide range of receptors including the bulbous endings found in hair follicles, the Meissner corpuscles and the Pacinian corpuscles. This classification broadly accompanies a functional shift from slowly adapting receptors (such as Ruffini endings) in the type I group to rapidly adapting receptors in the type III groups (such as Pacinian corpuscles). Phylogenetically, type I and type II receptors are found in all classes of vertebrates from fish to primates, while type III receptors are unknown in fish, start to occur in amphibia and become increasingly common in higher vertebrates (Malinovsky, 1996).

FIGURE 36.3 Classification of vertebrate mechanoreceptors by embryonic origin of associated tissues and complexity of ending; showing major examples. Type I are associated with tissues of mesodermal origin, type II with endodermal or epidermal and type III with epidermal. Subtypes (Ia, Ib, etc.) indicate morphological complexity. (Redrawn from Malinovsky, 1996.)

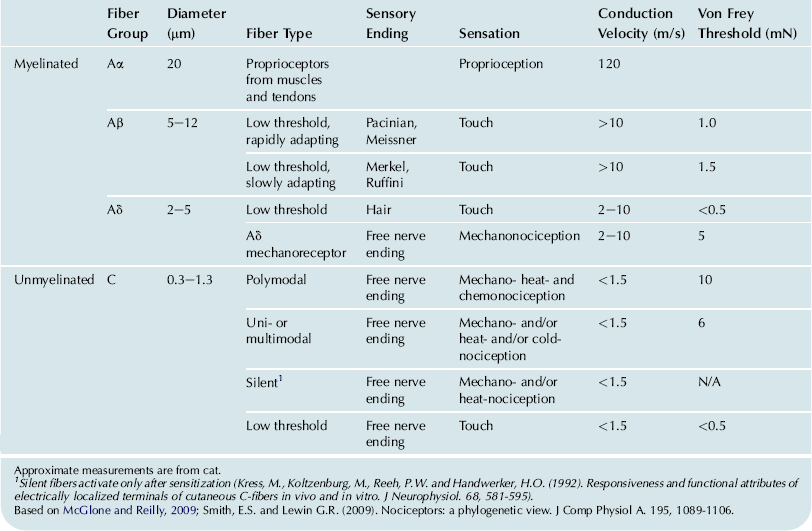

Vertebrate mechanoreceptors and nociceptors can also be classified based on myelination, conduction velocity of the afferent nerve fibers and whether they have low or high threshold as shown in Table 36.1 (Tsunozaki and Bautista, 2009). A further classification is based on the receptive field of the low threshold receptors; Meissner corpuscles and Merkel disks are located close to the skin surface and have small receptive fields while Pacinian corpuscles and Ruffini endings are located deeper in the dermis and have large receptive fields (McGlone and Reilly, 2009). Although most unmyelinated C-fibers originate from nociceptors that respond to one or more types of painful stimuli, one type of C-fiber is purely a touch receptor. These tactile C-fibers are only found in hairy skin and respond to slowly moving mechanical stimuli (McGlone and Reilly, 2009).

TABLE 36.1. Mammalian Cutaneous Sensory Fiber Types

VB Invertebrate Mechanoreceptors

Arthropods, especially insects, spiders and crustaceans, have provided important preparations for the investigation of mechanoreceptor function. Their receptors can be divided into two major groups, cuticular and multipolar, sometimes called type I and type II mechanoreceptors. Cuticular receptors, as the name implies, are generally associated with the arthropod cuticle and have their cell bodies in the periphery, close to the sensory ending. This arrangement is very different than most vertebrate and other invertebrate mechanoreceptors, which have their cell bodies in the central nervous system, distant from the sensory ending, and it allows recordings to be made close to the site of mechanotransduction. In addition, many arthropod receptor cells are relatively large, allowing penetration by microelectrodes, which is impossible in most vertebrate receptors.

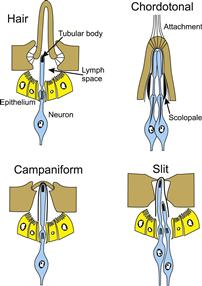

There are three major groups of cuticular receptors (Fig. 36.4). Hair-like receptors are found all over the outer surfaces of most arthropods in a variety of shapes and sizes from long, thin hairs to short pegs. The hair is supported by flexible cuticle within a socket and moves relative to the skin. In insects, a single mechanoreceptor neuron is closely apposed to the base and its sensory ending contains microtubules that end in a dense tubular body. It is assumed that movement of the hair compresses the ending, with the tubular body perhaps adding a rigid structure that the compression can work against. Crustacean and spider hairs are similar, but with two to four mechanosensory neurons in each hair. All arthropod hair types can contain other sensory neurons in addition to the mechanoreceptors, such as chemoreceptors in taste hairs. Campaniform (bell-shaped) sensilla are found in insects, where they detect stress in the cuticle. The stress leads to compression of a dendritic tip containing a tubular body by squeezing the bell as it is pushed downwards. Arachnids have analogous stress-detecting receptors called slit sensilla, where the neurons are located in cuticular slits. Chordotonal receptors are generally found further beneath the integument, although they can be connected to the integument by attachment structures. They serve a variety of functions, including hearing and joint movement detection. They generally lack tubular bodies but have dense scolopale structures surrounding the dendrite and can have multiple mechanosensory neurons.

FIGURE 36.4 Four common types of ciliated arthropod cuticular mechanoreceptors. Hair receptors of various shapes are prevalent in many arthropods. Chordotonal receptors are found in insects and crustaceans, campaniform sensilla in insects and slit sensilla in arachnids. Sensory dendrites are usually surrounded by a dense sheath and often contain tubular bodies formed from microtubules embedded in electron-dense material. Epithelial layers connected by tight junctions form a lymph space surrounding the dendrite. Chordotonal sensilla feature dense scolopale rods surrounding sensory dendrites and may have an attachment to another structure, such as a joint.

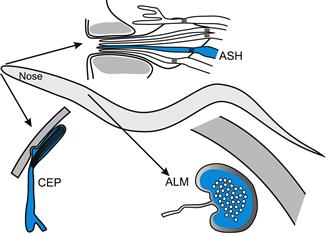

The nematode Caenorhabditis elegans also provides important models of mechanotransduction (Fig. 36.5). Its mechanoreceptors can be divided into three groups based on the specialization of their cytoskeleton. The first group has ciliated sensory endings, some of which abut to the cuticle while others, such as the polymodal sensory neuron in the nose, are located in channels that are open to external environment. Mechanoreceptors in the second group, including the gentle touch receptor neurons, are not ciliated but have large diameter microtubules in their sensory processes that are surrounded by an extracellular matrix, the mantle. The third group, including the harsh touch receptor, do not have specialized cytoskeleton. As the morphological differences suggest, research involving genetic manipulations combined with patch-clamp recordings have shown that several different mechanisms are involved in C. elegans mechanotransduction (O’Hagan et al., 2005; Chalfie, 2009; Kang et al., 2010).

FIGURE 36.5 Mechanoreceptors of the nematode C. elegans. Ciliated amphid (ASH) and cephalic (CEP) sensory neurons are found in the nose of the animal; ASH neurons are with a group of chemosensory neurons in the labial region and CEP neurons are closely apposed to cuticle. Gentle touch of the body is detected by anterior lateral microtubule (ALM) neurons, which contain many microtubules and are surrounded by extracellular matrix. (Based on Chalfie, 2009.)

VC Muscle Mechanoreceptors

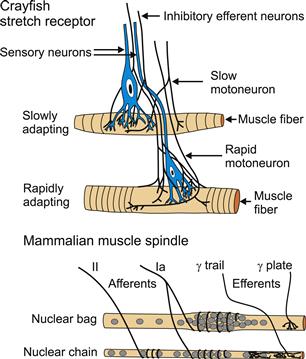

One of the best-known arthropod mechanoreceptors is the crayfish stretch receptor, which has interesting similarities to vertebrate muscle spindles (Fig. 36.6). These receptors are found on many muscles in crustaceans and are multipolar or type II arthropod mechanoreceptors. The large cell bodies are located in the periphery and the sensory endings consist of finely divided dendrites that cover part of the muscle surface. Unlike muscle spindles, crayfish stretch receptors are located on the main, force-producing muscle, and so are directly excited by passive stretch of the muscle or activation of motoneurons. This opens stretch activated ion channels that are permeable to Na+, K+ and Ca2+. Crayfish stretch receptors also receive presynaptic γ-aminobutyric acid (GABA) -ergic innervation to the sensory neuron directly, as well as the muscle (Rydqvist et al., 2007).

FIGURE 36.6 Invertebrate and vertebrate muscle mechanoreceptors. Crustacean stretch receptors are multipolar mechanoreceptors with many fine dendrites embedded in muscle fibers. There are two types of sensory neurons with different adaptation properties. Efferent GABAergic inhibitory neurons synapse onto the sensory neurons as well as the muscle fibers. (Partly based onRydqvist et al., 2007 .) Mammalian muscle spindles are modified muscle cells located within the main muscle and contain two types of fibers (nuclear bag and nuclear chain) with their own efferent innervation via two types of γ-motoneurons (γ-plate and γ-trail) that are activated separately from the main muscle fibers. There are also two types of sensory endings (Ia and II) with different adaptation characteristics. A whole muscle may contain hundreds of the much smaller muscle spindles.

Vertebrate muscle spindles are prominent and numerous mechanoreceptors that detect muscle stretch and are believed to be crucially involved in the control of muscle activation. However, they also make a major contribution to the senses of body position and movement (proprioception and kinesthesia) because appropriate artificial stimulation of muscle spindles gives sensations that the limbs are moving or in incorrect positions. Mammalian muscle spindles are small, modified muscle fibers located between the main, force-producing muscle fibers. Two types of sensory endings contact the spindle fibers and detect their length using mechanically activated cation channels. Spindle fibers are innervated by separate γ-motoneurons that allow the central nervous system to adjust their length, and hence the sensitivity of the receptors.

Closely associated with muscle spindles are the Golgi tendon organs. Located at the insertion of muscle fibers into the skeletal muscle tendons, these receptors use mechanically activated cation channels to detect muscle tension, rather than length, and contribute to reflex control of muscle activity.

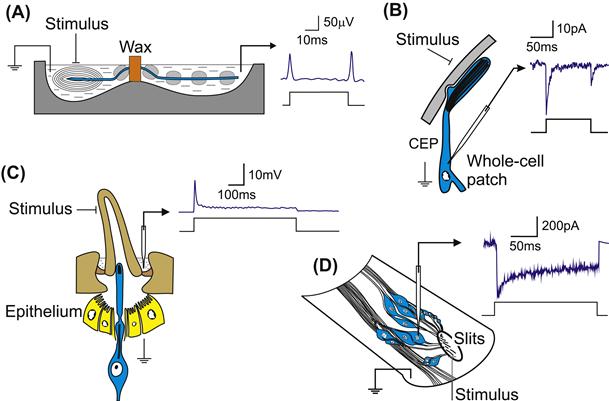

VI Experimental Mechanoreceptor Preparations

The complicated structures of many mechanoreceptor preparations make it challenging to record the receptor potential or receptor current, particularly while providing mechanical stimulation. Depending on the accessibility of the sensory neurons, various methods have been used (Fig. 36.7). Decremental conduction relies on insulating the sensory axon from the extracellular fluid as close as possible to the sensory ending, usually with a non-conducting substance, such as paraffin wax, petroleum jelly or sucrose solution, before leading it to a separate conducting solution. As the receptor is stimulated, some of the receptor current flows decrementally along the axon but cannot follow its normal path to the extracellular solution because of the insulation. It can only return through the second bath, where it is measured. This method has been used to observe the receptor potential in Pacinian corpuscles, muscle spindles and insect cuticular receptors. It allows a relatively stable preparation, because the receptor is not very disturbed and fine positioning is not needed after the initial setup. However, only a relatively small fraction of the total receptor current can usually be observed and the decremental conduction causes a selective loss of high-frequency signals through the membrane capacitance to ground, so that the observed receptor potential is attenuated and filtered. It is generally difficult to estimate accurately the amplitude and waveform of the original receptor potential.

FIGURE 36.7 Examples of four methods that have been used to observe the receptor current and potential in mechanoreceptors. (A) Decremental conduction measures the current flowing along the sensory axon from a Pacinian corpuscle by insulating the axon as close as possible to the receptor. This prevents receptor current from reaching ground, except via the measuring bath. (B) Whole-cell patch-clamp of a CEP mechanosensory neuron beneath the nose cuticle of C. elegans while stimulating the external cuticle. (C) Transepithelial measurement of an arthropod hair receptor by sampling the voltage as close as possible to the lymph space surrounding the sensory ending and relying on the high resistance of the epithelium. (D) Intracellular recording from a neuron in the spider slit sensillum during mechanical stimulation of the slits from below. (Redrawn in part from French et al., 2002; Kang et al., 2010.)

Arthropod cuticular receptors have the sensory neurons so close to the surface that it is possible to observe part of the current flowing through the neuron from the exterior. For a hair receptor, a small pool of conducting solution can be placed in the hair socket and an electrode of some sort (glass, wire, wick) measures the potential in the pool. These transepithelial measurements rely on the high-resistance epithelium that surrounds cuticular receptor neurons (see below) and the relatively low resistance of the thin, flexible socket. A similar technique is used for cuticular chemoreceptors, where it is common to cut the hair and place the tip of an electrode over the cut end to obtain even better electrical contact. This is more difficult for mechanoreceptors, where the hair must be moved to stimulate transduction. However, this method has been successfully used to record mechanotransduction currents in Drosophila bristle hairs, an experimental preparation that also allowed electrophysiological testing of mechanoreceptive mutant flies (Walker et al., 2000). Transepithelial measurements allow a relatively stable recording situation, but the high-resistance access pathway attenuates the signal and emphasizes high frequencies, which can pass more easily through the cuticle. Here again, it is difficult to estimate the original receptor potential amplitude and time course with accuracy.

Intracellular recording close to the site of sensory transduction is clearly desirable if it can be accomplished. However, it requires stable penetration of a small neuron while the sensory ending is moved nearby and has only been successfully achieved in a few preparations. Even more useful is voltage-clamp of the sensory receptor membrane, since this allows the voltage across the ion channels to be controlled while the current flowing through them is recorded. Crustacean stretch receptors are relatively easy to penetrate, even with two microelectrodes, and have been used for pioneering studies of the mechanotransduction and other currents that contribute to the electrical properties of the neurons during sensory transduction (Rydqvist et al., 2007). However, the transduction currents probably originate in very fine endings embedded in the muscle (see Fig. 36.7) so that accurate voltage-clamp of this current is difficult. Voltage-clamp of arthropod cuticular receptors was first performed in the cockroach tactile spine (Torkkeli and French, 1994). A more successful cuticular preparation is that of spider slit sensilla, where it is possible to clamp the receptor potential close to the sensory ending while stimulating the slits (French et al., 2002).

Whole-cell patch-clamp recordings of C. elegans touch receptor neurons during mechanical stimulation have recently become possible (see Figs. 36.5 and 36.7) providing preparations where receptor currents and potentials can be studied in an animal model that also allows genetic screening (O’Hagan et al., 2005; Kang et al., 2010). Patch-clamp recordings from rat dissociated dorsal root ganglion neurons that detect touch and pain are also possible (Hu and Lewin, 2006; McCarter and Levine, 2006). However, dissociated neurons in culture lack the components that normally connect the physical stimulus to the membrane of the sensory neurons (Hu and Lewin, 2006).

VII Steps in Mechanoreception

Mechanoreception can be viewed as a three-stage process comprising coupling, transduction and encoding (Loewenstein and Mendelson, 1965). The stimulus is first mechanically coupled from its origin to the membrane of the sensory cell where it is transduced into a receptor potential and, in cells with long sensory axons, this is encoded into action potentials that propagate to the central nervous system.

VIIA Coupling

Living cells are not normally exposed to the outside surface of an animal, so most, if not all, external mechanoreceptors have some kind of tissue between them and the source of the mechanical input. In some cases, these surrounding tissues are elaborate and obviously designed to modify the input signal by affecting its amplitude and possibly its dynamic properties. Internal mechanoreceptors also have a variety of surrounding tissues with presumably similar functions. The morphology of these structures varies so strongly between different mechanoreceptors that it is widely used for classification, as described above (see Figs. 36.3 and 36.4). The Pacinian corpuscle is probably the most illustrated vertebrate mechanoreceptor, with its complex lamellar structure, but it represents only one extreme of a wide range of vertebrate mechanoreceptor endings. Invertebrate mechanoreceptors also display many morphological forms, including the well-known hair receptors that cover the outside surfaces of insects and spiders and the stretch receptors of crayfish and lobsters. Although we generally assume that these elaborate extracellular structures modify the spatial and temporal sensitivities of the receptors, there is relatively little quantitative information about these functions.

In many cases, the external structures attenuate the stimulus, so that the displacement of the receptor cell membrane is much smaller than the original movement. For example, hairs on the human skin can be moved by several millimeters, but the resulting movements of the follicle receptors are only a few micrometers. Estimates of this attenuation have been made in some cases. For the Pacinian corpuscle, it has been suggested that the pressure reaching the inner capsule is attenuated by about two orders of magnitude (100) compared to the pressure on the outer lamellae (Bell et al., 1994), but this force may already be greatly reduced compared to the initial stimulus at the skin. An attenuation of about 100 was also reported for insect hairs, based on the morphology of the sensory structure and the location of the moving elements (French, 1992). Estimates of attenuation during coupling also allow us to estimate the threshold, or minimum amplitude of movement at the cell membrane that leads to sensation. For Pacinian corpuscles, movements of 1–10 nm at the capsule are probably adequate to produce action potentials at the optimum vibration frequency of about 250 Hz and sinusoidal movements of about 0.3 nm can stimulate auditory hair cells (Hudspeth, 2005). For insect cuticular hair receptors, threshold estimates of 4 nm and 3 nm were obtained for bee and cockroach (French, 1992). Estimates of the mechanical force required at the surface of the animal for transduction vary more, from about 25 μN in spider slit sensilla to more than 10 mN in mammalian glabrous skin (Goodman and Schwarz, 2003), which probably reflects the wide range of coupling structures involved.

The few attempts that have been made to quantify the mechanical effects of coupling over a range of input movements indicate that it can have significant temporal effects and be substantially non-linear. The mechanical properties of crayfish stretch receptors have been studied thoroughly (Rydqvist et al., 2007) and require non-linear springs plus at least one dashpot (or Voigt element) to account for the passive properties of the receptor without any muscular activity. No mechanical description is available that includes active contraction. Muscle spindles also have strongly time-dependent mechanical properties, with probably more complex dynamic behavior during γ-motoneuron activation. The viscoelastic properties of Pacinian corpuscles are assumed to be responsible for most of the time dependence of the receptor current, but have not yet been quantified.

VIIB Transduction

Transduction in mechanoreceptors probably involves mechanically activated ion channels in the receptor cell membrane (see Chapter 27 and recent reviews by Christensen and Corey, 2007; Chalfie, 2009; Árnadóttir and Chalfie, 2010; Lumpkin et al., 2010). Identification of these channels has only been made in a small number of mechanosensory neurons. The mechanotransduction channels in C. elegans gentle touch receptor neurons belong to the DEG/ENaC/ASIC (degenerin/epithelial sodium/acid sensitive ion channel) family (O’Hagan et al., 2005), while the pore-forming subunit in the ciliated touch receptors in C. elegans nose belong to the transient receptor potential (TRP) family (Kang et al., 2010). This TRP-4 protein is a member of the TRPN (or NompC) subfamily, and the NompC protein is also needed for mechanotransduction in Drosophila bristle hairs (Walker et al., 2000). Several members of the TRP and DEG/ENaC/ASIC families are expressed in mammalian mechanoreceptors, but it is not known if any of them are directly or indirectly involved in mechanotransduction (Tsunozaki and Bautista, 2009; Árnadóttir and Chalfie, 2010; Lumpkin et al., 2010).

The complex structures of the mechanoreceptor cells and the small numbers of mechanotransduction channels per cell mean that we do not yet have definitive single-channel recordings in intact, normally functioning mechanoreceptors. Single mechanically activated ion channels have been seen in crayfish stretch receptor neurons (French, 1992) and in tissue-cultured moth antennal mechanoreceptor neurons (Torkkeli and French, 1999), but these channels were not located on the fine sensory endings where transduction is thought to occur. The crayfish channels had maximum conductance to K+ (≈70 pS) but were also permeable to other cations. The moth channels were also permeable to K+ with a conductance of ≈40 pS, but their selectivity has not yet been established. Single channel conductance is better characterized in auditory and vestibular hair cells, with a range of at least 100–300 pS and wide cation permeability (Fettiplace, 2009; also see Chapter 37).

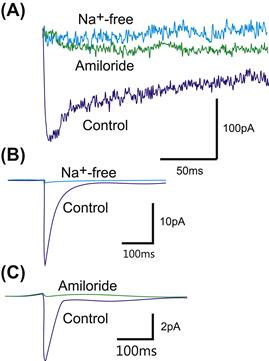

Although single-channel data are sparse, we have significant information about some transduction channels, including ionic selectivity, ionic conductance, blocking chemicals and the numbers of transduction channels in each receptor cell (Fig. 36.8). In Pacinian corpuscles, muscle spindles, crayfish stretch receptors, spider slit sensilla and C. elegans gentle touch receptors, mechanotransduction current is carried by Na+ ions. However, a variety of other cations can pass through most of these channels. (French, 1992; Bell et al., 1994; French et al., 2002; O’Hagan et al., 2005; Rydqvist et al., 2007). The mechanotransduction channels in C. elegans ciliated mechanoreceptor neurons (Kang et al., 2010) and in cultured rat dorsal root ganglion neurons (McCarter and Levine, 2006) are non-selective cation channels. In mouse dorsal root ganglion cells, the selectivity varied in different cell types so that slowly adapting current was non-selective to cations, while the rapidly adapting current was Na+ selective (Hu and Lewin, 2006).

FIGURE 36.8 Sodium selectivity and block of receptor current by amiloride in two mechanoreceptors. (A) Step movements of a spider slit sensillum activate an inward current that is reduced to zero by replacing the Na+ with impermeable choline or by adding 1 mM amiloride to the bath. (B and C) Sodium removal or application of 200 μM amiloride reduce the receptor current in whole-cell recordings from C. elegans PLM neurons. (Redrawn from French et al., 2002 and O’Hagan et al., 2005.)

In several of these cells, the sensory ending is surrounded by an elevated Na+ concentration and Na+ entry during transduction causes a graded depolarization that leads to action potentials if the stimulus is strong enough. In vertebrate auditory and vestibular hair cells, the mechanotransduction channels are preferably permeant to divalent cations, such as Ca2+ and Mg2+. However, in the inner ear, the hair bundles are bathed in endolymph that has high K+ concentration and the transduction current is mainly carried by K+ with a minor contribution from Ca2+ (Fettiplace, 2009). Similarly, in insect cuticular mechanoreceptors, the sensory ending is surrounded by lymph that is rich in K+ and has a positive electrical potential relative to the normal hemolymph (French, 1992). The cases where K+ is used to carry the receptor current generally rely on separating two regions of the sensory neurons by embedding them in an epithelial layer with tight junctions so that a K+ concentration gradient, usually combined with an electrical gradient, can drive K+ through the cell, depolarizing the membrane; similar arrangements exist for some of the Na-dependent systems. Cells with non-selective mechanotransduction channels may also receive a significant Ca2+ flux during transduction, because the inward Ca2+ electrochemical gradient is usually high.

Like many other ion channels, mechanotransduction channels can be blocked or closed by several chemicals. Gadolinium blocks mechanically-activated currents in several preparations including the crayfish stretch receptor (Rydqvist et al., 2007), the spider slit sensilla (French et al., 2002), cultured mouse dorsal root ganglion neurons (Hu and Lewin, 2006) and cochlear hair cells (Fettiplace, 2009). Sensitivity to gadolinium is sometimes used as an indicator that mechanically-activated channels are involved in a physiological process, but Gd3+ also blocks many Ca2+ channels, as well as some ligand- and voltage-gated cation channels. Amiloride is a well-known blocker of epithelial Na+ channels and it blocks mechanotransduction current in the C. elegans gentle touch receptor neurons that are members of this family (O’Hagan et al., 2005) and in the spider slit sensilla (French et al., 2002) (see Fig. 36.8). The mechanotransduction current in ciliated touch receptor neurons in C. elegans nose are insensitive to amiloride, indicating that the TRP-4 channels are not sensitive to this blocker (Kang et al., 2010). Mechanically-activated currents in the cultured mouse dorsal root ganglion neurons (Hu and Lewin, 2006) and crayfish stretch receptors (Rydqvist et al., 2007) are also insensitive to amiloride, but it is not known which gene family these channels belong to. Interestingly, the mechanotransduction current in vertebrate cochlear hair cells is blocked by amiloride, even though there is no evidence that this channel is a member of the ENaC family (Fettiplace, 2009). Some local anesthetics have also been used to block the receptor current in the crayfish stretch receptor (Rydqvist et al., 2007) and certain antibiotics as well as La3+, ruthenium red, FM1-45 and Ca2+ are known to block transduction in auditory hair cells (Fettiplace, 2009).

The acid sensitive ion channel (ASIC) family has been associated with some mechanosensitive neurons and several members of the DEG/ENaC channel family are known to be opened by low pH (Árnadóttir and Chalfie, 2010). Mechanical sensitivity was enhanced by low pH in spider slit sensilla (French et al., 2002) although there was no evidence of direct acid activation.

Whole cell mechanotransduction currents have been recorded in some cells and noise, or fluctuation, analysis has been used to estimate single-channel conductance and the numbers of channels per cell in several cases. Noise analysis relies upon the idea that receptor channels opening and closing create variance in the mean receptor current, because all known channels regulate their average conductance by switching rapidly between open and closed states. Therefore, the variance is minimal when all receptor channels are either fully open or fully closed and maximal when the mean open probability is 0.5. Assuming that the noise variance is due to the summation of currents flowing through many independent, identical channels that are randomly opening and closing, it is possible to quantify the relationships between the membrane potential, total cell membrane current variance, total current, number of channels, single-channel conductance and mean channel open probability. In a few cases, noise analysis measurements in non-receptor systems have been confirmed by single-channel experiments. Noise analysis measurements are challenging because of the inherent difficulty of making good recordings of membrane currents in mechanoreceptor cells. However, the cases where they have been made have produced rather consistent results. In statocyst cells of the snail Hermissenda, noise analysis gave values of 5 pS for the single-channel conductance and 40 channels per cell (French, 1992). In vertebrate hair cells, the corresponding values were 12 pS and 280 channels per cell (Hudspeth, 2005) and in spider slit sensilla neurons, 7.5 pS and 300 channels per cell (French et al., 2002). In C. elegans gentle touch receptor neurons, the single channel conductance was 25 pS and the number of channels per cell was estimated to be 14 to 25 (O’Hagan et al., 2005) while the ciliated touch receptor neurons had 21 channels per cell with a conductance of 16 pS per channel (Kang et al., 2010). These single-channel conductances are all at the low end of the range of known mechanically-activated ion channels and significantly lower than the single-channel measurements described above. The total membrane conductances due to mechanotransduction channels observed during these measurements agree with several estimates made in other mechanosensory neurons, and would provide enough current to depolarize the neurons to produce action potentials. Therefore, it seems likely that the number of channels in each cell is limited to a few hundred at most, raising difficulties for electrophysiological, molecular and histological attempts at localization or characterization.

Another interesting property of mechanotransduction channels is their temperature sensitivity. This has been measured in at least six invertebrate and vertebrate preparations with activation energy values in the range of 12–22 kcal/mol (≈50–100 kJ/mol) (French et al., 2002). These energy values are similar to those required to break chemical bonds and significantly more than the energy barriers associated with ionic diffusion or conductance through ion channels. Little is known about the activation energy of mechanically-activated ion channels, but it seems likely that some crucial stage in the link between membrane tension and ion channel opening leads to this relatively high energetic barrier.

VIIC Encoding

Most mechanoreceptors use action potentials to transmit information to the central nervous system. The action potentials are produced by conventional combinations of voltage-dependent Na+ and K+ channels. Accurate characterization of these currents and other currents involved in the control of membrane excitability relies on voltage-clamp recordings, which have only been possible in a few cases. Tetrodotoxin-sensitive Na+ channels are clearly responsible for the action potential upswing in Pacinian corpuscles (Loewenstein and Mendelson, 1965), lobster and crayfish stretch receptors (French, 1992; Rydqvist et al., 2007), the cockroach tactile spine (Torkkeli and French, 1994) and spider slit sensilla (French et al., 2002). The distribution of these channels in the cell membrane determines where the receptor potential is converted to action potentials. Voltage-gated Na+ channels are present and the action potentials initiated at the first node of Ranvier under the lamellae of the Pacinian corpuscle (Pawson and Bolanowski, 2002). In the slowly adapting crayfish stretch receptor, the channels are located on the axon and the cell body but, in the rapidly adapting receptor, the channels are restricted to the axon itself (Rydqvist et al., 2007). In spider slit sensilla, Na+ channels are more evenly distributed, with a significant concentration on the sensory dendrite and the soma, with action potentials initiated in the dendrite (French et al., 2002). An additional slow component of Na+ inactivation was needed to model the firing behavior of lobster stretch receptors and is probably present in the slowly adapting crayfish stretch receptor (Rydqvist et al., 2007) and the cockroach tactile spine (French and Torkkeli, 1994).C. elegans neurons do not have voltage-gated Na+ channels, but transmit signals as graded or plateau potentials that are believed to be carried by Ca2+ (Lockery and Goodman, 2009).

Delayed-rectifier K+ currents seem to be responsible for action potential repolarization in all of the mechanoreceptors studied, but other types of K+ currents are found in different receptors. Transient K+ currents resembling the A-type current have been described in the slowly adapting cockroach tactile spine (Torkkeli and French, 1994) but not in spider slit sensilla that adapt significantly faster (French et al., 2002). The slowly adapting crayfish stretch receptor neuron has two components of delayed rectifier K+ current and an A-current (Rydqvist et al., 2007). Ca2+-activated K+ currents were found in the cockroach tactile spine (Torkkeli and French, 1995) and vertebrate auditory hair cells (Hudspeth, 2005). An inwardly rectifying K+ current is present in the slowly adapting lobster stretch receptor (French, 1992) but has not been described in other mechanoreceptors.

Ca2+ currents are present in vertebrate auditory neurons and negative feedback from depolarization-induced Ca2+ entry to hyperpolarization via Ca2+-activated K+ current has been suggested to cause frequency tuning (Hudspeth, 2005). Ca2+ currents are also present in spider slit sensilla (French et al., 2002) and increased intracellular Ca2+ modulates both the receptor current and firing rate (Höger et al., 2010). Electrogenic Na+ pumping is well established in crayfish stretch receptors and contributes to adaptation of action potential discharge by repolarizing the cell after Na+ entry. There is also evidence for its contribution to adaptation in the cockroach tactile spine neuron (French, 1992).

The terms rapid adaptation and slow adaptation are qualitative and have been used to describe a wide range of time dependence. However, some mechanoreceptors adapt so rapidly that only one or a few action potentials are produced in response to a step stimulus (Fig. 36.9) and so can truly be called “rapidly adapting”. Rapid adaptation generally infers a cessation of activity soon after the start of a constant stimulus, but many rapidly adapting mechanoreceptors can fire action potentials as long as the stimulus is moving, which makes them excellent vibration detectors (Fig. 36.9). It has been known for many years that the encoding stage of the Pacinian corpuscle limits its response to one or two action potentials (Loewenstein and Mendelson, 1965), although the ionic basis for the effect is not known. In the cockroach tactile spine, removal of the rapidly deactivating K+ A-current increased the overall rate of firing, but the receptor continued to adapt, while removal of the Ca2+-activated K+ current removed most of the adaptation (Torkkeli and French, 1994, 1995). However, blockade of these currents does not affect the shape of individual action potentials because their rapid repolarization is due to the delayed-rectifier current. Rapid adaptation in spider VS-3 neurons seems to be partially due to the slow recovery of voltage activated Na+ channels from their normal rapid inactivation (French et al., 2002).

FIGURE 36.9 Rapid adaptation in vertebrate and invertebrate mechanoreceptors. A Pacinian corpuscle and a spider slit sensillum neuron each fire one or two action potentials in response to a step deformation and are then silent. But such receptors usually respond strongly to oscillating stimuli, making them good vibration detectors. Lower traces show a slit sensillum neuron firing 50 action potentials per second with sinusoidal mechanical stimulation. (Partly redrawn from French and Torkkeli, 1994.)

Following the encoding stage, action potentials propagate into the central nervous system along nerve axons. In vertebrates, the cell bodies of the neurons are located in the dorsal root ganglia of the spinal cord and the axons enter via the dorsal roots. Cell bodies of the cranial mechanoreceptor nerves are located in the trigeminal ganglion. The major transmitter at the first central synapse is probably the excitatory amino acid glutamate. Arthropod mechanoreceptors have their cell bodies in the periphery and send axons into the central nervous system via nerve roots of the segmental ganglia, which are sometimes fused into larger structures. Conduction velocities are typically 1–5 m/s. The dominant transmitter for arthropod mechanoreceptors is acetylcholine (Burrows, 1996), although several spider mechanosensory neurons also contain histamine (Fabian et al., 2002). Relevant information about crustacean muscle, including the unique innervation, is given in the Appendix to Chapter 47.

VIII Efferent Control of Mechanoreceptors

All mechanoreceptors receive inhibitory efferent innervation close to the output synapses of their centrally located axon terminals. Other well-known examples of efferent control are the gamma innervation of muscle spindles (see Fig. 36.6) and presynaptic inhibition of peripheral mechanoreceptors and pain receptors (Rudomin, 2009). Presynaptic inhibition of mechanosensory neurons is remarkably similar in all vertebrate and invertebrate species studied so far (Burrows, 1996; Torkkeli and Panek, 2002; Rudomin, 2009). In addition to the GABAergic inhibitory control of axon terminals, most mechanosensory neurons are also regulated by other chemical agents. In many cases, the sensory endings and cell bodies also receive synaptic input from efferent neurons or accessory cells. Transmitter receptors are found in the somata of vertebrate dorsal root ganglion neurons (Robertson, 1989) and in the nerve fibers inside the Pacinian corpuscles (Pawson et al., 2009).

Merkel cells form synaptic contacts with mechanosensory afferents and, although Merkel cells have recently been shown to be necessary for the light touch responses, it is still not clear whether these cells are mainly modulatory or the actual sites of mechanotransduction (Lumpkin et al., 2010). Keratinocytes of the skin epidermis are also believed to perform signaling roles to mechanosensory endings (Tsunozaki and Bautista, 2009; Lumpkin et al., 2010). Modulation of vertebrate cutaneous mechanoreceptors and pain receptors by circulating factors has also been recognized for a long time. For example, sympathetic efferents have modulatory effects on muscle spindles, Pacinian corpuscles, several types of low-threshold skin mechanoreceptors and pain receptors, and these neurons express adrenergic receptors (Birder and Perl, 1999). Rohon–Beard neurons, which are developmentally early amphibian and fish touch receptors, have serotonergic efferent innervation and 5-HT is believed to alter their sensitivity to mechanical stimuli by inhibiting both low- and high-voltage-activated Ca2+ currents (Sun and Dale, 1997).

Arthropod mechanosensory neurons are modulated by biogenic amines, especially octopamine, the invertebrate analog of norepinephrine (Burrows, 1996). The dorsal unpaired median neurons of locust, which secrete octopamine, have terminals in the periphery, closely associated with the dendrites of mechanoreceptors that are modulated by octopamine. Similarly, octopamine-containing efferent neurons innervate spider mechanosensory afferents, which have octopamine receptors and are modulated by octopamine (Torkkeli et al., 2011). Although octopaminergic modulation in arthropods is probably the most thoroughly studied neuromodulatory system, there are no clear conclusions about the mechanisms involved. Octopamine may increase or decrease spiking frequency, even in the same mechanosensory neuron and it may act by increasing intracellular Ca2+ or cAMP concentration or both (Torkkeli et al., 2011).

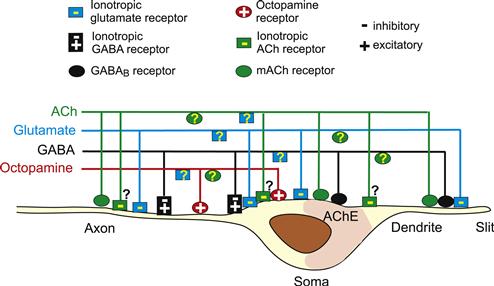

The most conclusive evidence that peripheral regions of mechanoreceptors receive efferent innervation comes from immunocytochemical findings in arachnid and crustacean mechanoreceptors (see Figs. 36.6 and 36.10). Both types of receptors have dense efferent innervation, forming several types of synapses on all parts of the sensory neurons, including their somata and dendrites (Fabian-Fine et al., 2002). Spider cuticular mechanoreceptors have at least four different types of synaptic structures on the efferent terminals. In addition to octopamine, the efferent neurons contain GABA, glutamate and acetylcholine and all of these agents modulate the excitability of mechanosensory neurons, which have a variety of receptors to these transmitters (Widmer et al., 2006; Pfeiffer et al., 2009; Torkkeli et al., 2011). It is clear that the central nervous systems can control the sensitivity of mechanosensory neurons, although the full extent of this control is not yet completely understood.

FIGURE 36.10 A schematic diagram showing the transmitter receptors on spider mechanosensory neurons and the efferent fibers innervating these neurons. At least three GABAergic, one glutamatergic and one octopaminergic efferent fiber have been identified by immunocytochemistry. In addition, choline acetyltransferase (ChAT) activity was present in one efferent fiber. Ionotropic inhibitory glutamate receptors (IGlu) are located in all parts of the sensory neurons. Excitatory G-protein coupled octopamine receptors are only found in the axons and proximal parts of the somata. Ionotropic inhibitory-excitatory GABA receptors are probably also only present in the axons and somata. In contrast, the metabotropic GABAB receptors were found only at the distal parts of the soma and the dendrites. Ionotropic inhibitory ACh receptors are only present in the very rapidly adapting subgroup of VS-3 neurons (type A), but their distribution in these cells has not been determined, therefore these receptors are indicated with question marks. Muscarinic ACh receptors (mAChR) are present on all parts of the sensory neurons. AChE activity was present only in the type A VS-3 neuron and concentrated on the distal parts of the somata. IGlu and mACh receptors are also found on some of the efferent neurons, but these have not been identified and therefore the receptors are indicated by question marks. (Fabian-Fine et al., 2002; Widmer et al., 2006; Pfeiffer et al., 2009; Torkkeli et al., 2011).

IX Conclusions

The large variety of morphological forms of mechanoreceptors indicates that the external components surrounding the sensitive endings play important roles in controlling the receptor behavior. Most of this control is assumed to involve coupling of initial movement into deformation of the membrane containing mechanically-activated channels. However, the mechanism involved has not been thoroughly decoded in any receptor and there may be other schemes involved, such as chemical modulation of excitability. Characterization of mechanically-activated channels is proceeding, but it is important to realize that no single-channel recordings have yet been unequivocally linked to mechanotransduction in any mechanosensory neuron. Therefore, it may yet emerge that an unknown family, or several different families, of channel proteins is responsible for this function in true mechanoreceptors. The encoding of action potentials from receptor current and the general control of receptor excitability involves voltage- and Ca2+-activated ion channels, similar to those in other excitable cells, and complete models of encoding in some receptors are now available. Adaptation and general dynamic properties of mechanoreception involve both the coupling and encoding stages of the process. There may also be significant dynamic behavior of mechanotransduction channels, but this will not become clear until the channels themselves are better known. Efferent control of transduction and adaptation in mechanoreceptors is common but only well described in a small number of preparations.

Mechanoreception is a widespread and crucially important process for many physiological functions. Recent developments in electrophysiological techniques and new experimental preparations have provided important information about each stage of mechanoreception from initial deformation to action potential production, but much remains to be learned. In particular, the lack of vertebrate preparations that would allow voltage-clamp of receptor currents at the intact sensory ending or detailed examination of action potential encoding is a major problem. When the molecules responsible for mechanotransduction are known, it should be possible to discover how they are linked to other cellular components to confer mechanical sensitivity and from there to complete models of mechanoreception in intact sensory cells.

BIBLIOGRAPHY

1. Árnadóttir J, Chalfie M. Eukaryotic mechanosensitive channels. Annu Rev Biophys. 2010;39:111–137.

2. Bell J, Bolanowski S, Holmes MH. The structure and function of Pacinian corpuscles: a review. Prog Neurobiol. 1994;42:79–128.

3. Birder LA, Perl ER. Expression of α2-adrenergic receptors in rat primary afferent neurones after peripheral nerve injury or inflammation. J Physiol. 1999;515:533–542.

4. Burrows M. The Neurobiology of an Insect Brain. Oxford: Oxford University Press; 1996.

5. Chalfie M. Neurosensory mechanotransduction. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2009;10:44–52.

6. Christensen AP, Corey DP. TRP channels in mechanosensation: direct or indirect activation?. Nat Rev Neurosci. 2007;8:510–521.

7. Fabian-Fine R, Seyfarth E-A, Meinertzhagen IA. Peripheral synaptic contacts at mechanoreceptors in arachnids and crustaceans: morphological and immunocytochemical characteristics. Microsc Res Tech. 2002;58:283–298.

8. Fettiplace R. Defining features of the hair cell mechanoelectrical transducer channel. Pflügers Arch. 2009;458:1115–1123.

9. French AS. Mechanotransduction. Annu Rev Physiol. 1992;54:135–152.

10. French AS, Torkkeli PH. Information transmission at 500 bits/s by action potentials in a mechanosensory neuron of the cockroach. Neurosci Lett. 1998;243:113–116.

11. French AS, Torkkeli PH. The basis of rapid adaptation in mechanoreceptors. News Physiol Sci. 1994;9:158–161.

12. French AS, Torkkeli PH, Seyfarth E-A. From stress and strain to spikes: mechanotransduction in spider slit sensilla. J Comp Physiol A. 2002;188:739–752.

13. Goodman MB, Schwarz EM. Transducing touch in Caenorhabditis elegans. Annu Rev Physiol. 2003;65:429–452.

14. Hu J, Lewin GR. Mechanosensitive currents in the neurites of cultured mouse sensory neurones. J Physiol. 2006;577:815–828.

15. Hudspeth AJ. How the ear’s works work: mechanoelectrical transduction and amplification by hair cells. C R Biol. 2005;328:155–162.

16. Höger U, Torkkeli PH, French AS. Feedback modulation of transduction by calcium in a spider mechanoreceptor. Eur J Neurosci. 2010;32:1473–1479.

17. Juusola M, French AS. The efficiency of sensory information coding by mechanoreceptor neurons. Neuron. 1997;18:959–968.

18. Kang L, Gao J, Schafer WR, Xie Z, Xu XZ. C. elegans TRP family protein TRP-4 is a pore-forming subunit of a native mechanotransduction channel. Neuron. 2010;67:381–391.

19. Lockery SR, Goodman MB. The quest for action potentials in C. elegans neurons hits a plateau. Nat Neurosci. 2009;12:377–378.

20. Loewenstein WR, Mendelson M. Components of receptor adaptation in a Pacinian corpuscle. J Physiol. 1965;177:377–397.

21. Lumpkin EA, Marshall KL, Nelson AM. The cell biology of touch. J Cell Biol. 2010;191:237–248.

22. Malinovsky L. Sensory nerve formations in the skin and their classification. Microsc Res Tech. 1996;34:283–301.

23. McCarter GC, Levine JD. Ionic basis of a mechanotransduction current in adult rat dorsal root ganglion neurons. Mol Pain. 2006;2:28–40.

24. McGlone F, Reilly D. The cutaneous sensory system. Neurosci Biobehav Rev. 2009;34:148–159.

25. O’Hagan R, Chalfie M, Goodman MB. The MEC-4 DEG/ENaC channel of Caenorhabditis elegans touch receptor neurons transduces mechanical signals. Nat Neurosci. 2005;8:43–50.

26. Pawson L, Bolanowski SJ. Voltage-gated sodium channels are present on both the neural and capsular structures of Pacinian corpuscles. Somatosens Mot Res. 2002;19:231–237.

27. Pawson L, Prestia LT, Mahoney GK, Guclu B, Cox PJ, Pack AK. GABAergic/glutamatergic-glial/neuronal interaction contributes to rapid adaptation in Pacinian corpuscles. J Neurosci. 2009;29:2695–2705.

28. Pfeiffer K, Panek I, Höger U, French AS, Torkkeli PH. Random stimulation of spider mechanosensory neurons reveals long-lasting excitation by GABA and muscimol. J Neurophysiol. 2009;101:54–66.

29. Robertson B. Characteristics of GABA-activated chloride channels in mammalian dorsal root ganglion neurones. J Physiol. 1989;411:285–300.

30. Rudomin P. In search of lost presynaptic inhibition. Exp Brain Res. 2009;196:139–151.

31. Rydqvist B, Lin JH, Sand P, Swerup C. Mechanotransduction and the crayfish stretch receptor. Physiol Behav. 2007;92:21–28.

32. Sun QQ, Dale N. Serotonergic inhibition of the T-type and high voltage-activated Ca2+ currents in the primary sensory neurons of Xenopus larvae. J Neurosci. 1997;17:6639–6649.

33. Torkkeli PH, French AS. Characterization of a transient outward current in a rapidly adapting insect mechanoreceptor neuron. Pflügers Arch. 1994;429:72–78.

34. Torkkeli PH, French AS. Slowly inactivating outward currents in a cuticular mechanoreceptor neuron of the cockroach (Periplaneta americana). J Neurophysiol. 1995;74:1200–1211.

35. Torkkeli PH, French AS. Primary culture of antennal mechanoreceptor neurons of Manduca sexta. Cell Tissue Res. 1999;297:301–309.

36. Torkkeli PH, Panek I. Neuromodulation of arthropod mechanosensory neurons. Microsc Res Tech. 2002;58:299–311.

37. Torkkeli PH, Panek I, Meisner S. Ca2+/calmodulin dependent protein kinase II mediates octopamine-induced increase in sensitivity in spider VS-3 mechanosensory neurons. Eur J Neurosci., (in press) 2011.

38. Tsunozaki M, Bautista DM. Mammalian somatosensory mechanotransduction. Curr Opin Neurobiol. 2009;19:362–369.

39. Walker RG, Willingham AT, Zuker CS. A Drosophila mechanosensory transduction channel. Science. 2000;287:2229–2234.

40. Widmer A, Panek I, Höger U, Meisner S, French AS, Torkkeli PH. Acetylcholine receptors in spider peripheral mechanosensilla. J Comp Physiol A. 2006;192:85–95.