EVER SINCE THEIR EARLIEST DAYS, humans have been preoccupied with animals as the source of much of their food. But early people also held magico-religious beliefs about the beasts and birds, as revealed by the extraordinary cave paintings at different sites throughout Europe dating from the upper Palaeolithic period, 50,000-10,000 years ago. These depict an obsession with the chase and the reproduction of animals, a theme that links the killing to a desire to see the prey flourish and multiply and, inter alia, facilitate human survival — an early example of ecological thinking.

One of the most famous cave-painting sites is at Lascaux, set in a limestone hill in the Périgord landscape of France. Here, some 17,000 years ago, Cro-Magnon artists perfected their skills, drawing, scratching and colouring magnificent images of the larger animals — bulls, aurochs, reindeer, bison, horses, cows with the odd musk ox, ibex, lions, brown bear and a woolly rhinoceros — that appear to float in a kaleidoscopic, mystical way across the cave’s calcite walls. These caves were not used as dwelling places but as art galleries, where the paintings held some kind of ritual or magical significance, to be visited occasionally. Hidden amongst these, on a surface in the deepest recess of the cave, is an astonishing scene of a four-fingered man with a distinctive bird-like head, lying on the ground with a large erect penis while being charged down by a bison that has just been speared by the man, with entrails spilling from its belly (Fig. 5). Near the man is a bird, set on the top of a pole.

This is a rare image among the Lascaux paintings, as neither human nor bird figures are to be found elsewhere in the cave. The bird set on the pole may represent the external soul of the prostrate bird-man, suggesting a mythological connection between humans and birds concerning death and life thereafter.The sudden appearance and disappearance of birds must have baffled early people. There was always the possibility that the birds had some form of contact with higher spirits or gods — made plausible by their powers of flight, up and away into the skies above, later to descend after communicating with the deities.

The sudden appearance and disappearance of birds must have baffled early people. There was always the possibility that the birds had some form of contact with higher spirits or gods — made plausible by their powers of flight, up and away into the skies above, later to descend after communicating with the deities.

FIG 5. Lascaux cave painting depicting a prostrate man, having been charged down by a bison. Note the highly symbolic bird at the end of the pole. (Norbert Aujoult, National Centre of Prehistory, France)

Myths and legends concerning birds and other animals arose to explain the unexplainable in the natural world at a time when the understanding of nature and natural cycles was primordial. Wildfowl, because of their large size, powerfulness and migratory habits, feature disproportionately among the myths and legends concerning birds. Among these myths are two particularly intriguing stories, one about geese and the other concerning swans. Each is a tale that persisted for an exceptionally long time, and both of them had important social and conservation consequences.

The first is the bird-fish myth that was in vogue for over a thousand years in Europe and the Middle East, and whose roots may be even older. In its simplest form, shellfish turn into birds. The myth apparently started life as an oral tradition, and scholars then transmogrified it into literature, thus providing interesting insights into pre-scientific thought. The myth was repeatedly copied by many writers over the centuries. As Edward Armstrong wrote in his New Naturalist The Folklore of Birds,1 the frequent copying of the myth in many texts throws light on the credulity or mendacity of scholars, which is also well exposed in Edward Heron-Allen’s marvellous and scholarly book Barnacles in Nature and Myth.2

The first authoritative statement of the myth was by Giraldus Cambrensis, a Welshman whose real name was Gerald de Barri, who became chaplain to King Henry II in 1184. He had first visited Ireland in 1183, and was chosen to accompany one of the King’s sons, John, as a tutor on another Irish tour the following year. Based on his observations in Ireland he wrote his famous Topographia Hibernica, which was read — the form of publishing at that time — before the masters and scholars of Oxford in 1186. In the first section of the book, in Chapter XI, De bernacis ex abiete nascentibus earumque natura — barnacles that are born of the fir-tree and their nature — he wrote

There are many birds here that are called barnacles, which nature, acting against her own laws, produces in a wonderful way. They are like marsh geese, but smaller. At first they appear as excrescences on fir-logs carried down upon the waters. Then they hang by their beaks from what seems like sea-weed clinging to the log, while their bodies, to allow for their more unimpeded development, are enclosed in shells. And so in the course of time, having put on a stout covering of feathers, they either slip into the water, or take themselves in flight to the freedom of the air. They take their food and nourishment from the juice of wood and water during their mysterious and remarkable generation. I myself have seen many times and with my own eyes more than a thousand of these small bird-like creatures hanging from a single log upon the sea-shore. They were in their shells and already formed. No eggs are laid as is usual as a result of mating. No bird ever sits upon eggs to hatch and in no corner of the land will you see them breeding or building nests. Accordingly in some parts of Ireland bishops and religious men eat them without sin during a fasting time, regarding them as not being flesh, since they were not born of flesh.3

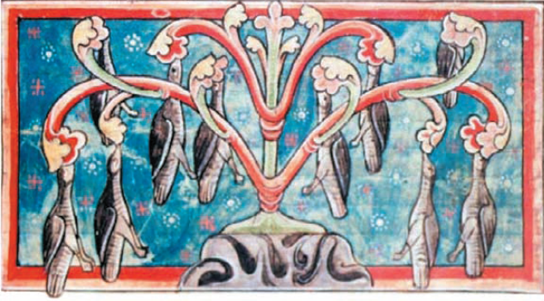

FIG 6. Tree geese. (British Library, Harley MS 4751 Folio 36r)

Edward Armstrong argues that the bird-fish myth can be traced back to about the tenth century, when references in an early Jewish Rabbinic text speak about black birds, ‘similar to the bird called the Diver’, developing from white jelly in the shape of an egg when it fell into the water from trees growing on the seashore. The location of the myth was most probably Ireland. When Allah wills it, the egg, which has changed into the form of a bird with its feet and bill attached to the wood, develops feathers and drops to the water. The birds then scuttle on the water surface, but they are never found alive, only dead, washed up on the shore. Geese are not mentioned in the account. The ‘black diving birds’ washed up dead on the shores of Ireland were most likely to have been little auks, which often occur in large numbers or ‘wrecks’, especially after severe winter storms. If barnacle geese were observed along the shoreline among flotsam and jetsam where dead little auks were also found, it would have been an easy leap of the imagination to assume that the little auks, like the shellfish, were the early stages of the geese.

As barnacle geese were found on floating timber (produced ex lignis abiegnis), it was assumed that they were generated from trees overhanging the sea — and thus they became ‘tree geese’. The illustration shown in Figure 6 dates from about 1230—40, and the text that accompanied it states that

Barnacle geese come from trees that grow over water. The trees produce birds that look like small geese; the young birds hang from their beaks from the trees. When the birds are mature enough, they fall from the trees; any that fall into the water float and are safe, but those that fall on land die.

Thus were explained the mysterious comings and goings of barnacle geese, which arrived on the west coasts of Scotland and Ireland each October, as if created spontaneously, and then suddenly disappeared at the end of winter in April. Anyone who has encountered goose barnacles, attached by their fleshy-looking stalks on floating or washed-up wood along the shoreline, would forgive the credulity of the early naturalists. With some imagination one can see how the grey-shelled, generally tulip-shaped goose barnacles, with protruding plumose appendages superficially resembling feathers, might have been the origin of the barnacle geese (Fig. 7).

FIG 7. Goose barnacle, Lepas spp. The feather-like appendages are cirri, used for sifting out and capturing the plankton on which the barnacle feeds. (Anthony Bannister/NHPA)

As the barnacle goose arose from a shellfish (the goose barnacle is a crustacean) it was classified as fish, not fowl, and thus could be eaten during Lent and on Fridays. Brant geese, not that dissimilar to barnacles and easily confused with the barnacle goose, were also eaten as ‘fish’. Giraldus Cambrensis, in a moralistic rant, condemned Irish Bishops and clergy for regarding geese as ‘fish’. His ire eventually reached Rome, and Pope Innocent III, as reported by Vincent of Beauvais, at the Fourth General Lateran Council in 1215 issued a Papal Bull that forbade the eating of barnacle geese during Lent and on Fridays.4 Perhaps some barnacle and brant geese derived some protection from this Bull, but even as late as 1914 in certain parts of Ireland — County Donegal and elsewhere in Ulster — barnacle geese were being killed and eaten during Lent, as they were still regarded as ‘more fish than fowl’.5

At the end of the sixteenth century, John Gerard, the great British herbalist, straying somewhat outside his brief, went further than most in propagating the bird-fish myth. In his Herbal (1597) the last entry in the book concerns the ‘Goose tree, Barnacle tree, or the tree bearing Geese’. He wrote that

FIG 8. The barnacle tree, from Gerard’s Herbal.

There are found in the North parts of Scotland and islands adjacent, called the Orkneys, certain trees whereon do grow certain shells of a white colour tending to russet, wherein are contained little living creatures: which shells in time of maturity do open, and out of them grow those little living things, which falling into the water do become fowles, which we call Barnakles; in the North of England, brent geese; and in Lancashire, tree geese: but the other that do fall upon the land perish and come to nothing.6

Spinning the myth further, and after declaring that ‘what our eyes have seen and our hands have touched’, he collected some shells found growing on the trunk of an old rotten tree on the shore between Dover and Romney. He took them to London and when he opened them he found ‘living things without form or shape and in others’… and ‘birds covered with soft down, the shell half open and the birds ready to fall out, which no doubt were the fowles called Barnakles’ ‘They spawn as it were in March and April; the geese are formed in May and June, and come to the fullness of feathers the month after.’ He ‘borrowed’ an illustration from Mathias de Lobel’s Stirpium Historia (1570) and added in geese, nestling within the shells, ready to tumble out (Fig. 8).

The outline of the bird-fish myth is probably known to most naturalists today. But the pervasiveness and longevity of the myth may not be so well appreciated, nor the fact that the barnacle goose and the brant goose received early protection and conservation status through the issuing of a Papal Bull of 1215.

Swans are spectacular wildfowl, large, conspicuously white and noisy. Moreover, the two wild species occurring as winter visitors to Britain and Ireland — whooper and Bewick’s — undertook mysterious migrations, not understood until very recently. The trumpeting calls of the wild swans, and the waxy-swishing sound of the mute swan’s wings while in flight overhead, added to the mystery of these birds and made them prime candidates for mythology — and that in turn led to their elevation to the status of special species that were not to be hunted or shot. It was believed that the souls of the dead were embodied in swans, and to kill a swan would bring bad luck to the hunter, even leading to death within the year. Nowhere is the association of the human soul and spirit with those of birds better exemplified than in the Irish legend of the Children of Lir.

The Children of Lir is one of the Three Sorrows or Pieties of Story-telling that form part of the Irish mythological cycle. They are founded on love, jealousy and murder and set in the mists of time of magic, when belief in druids and other supernatural phenomena was the culture. It was the time when the ancient tribes of Tuatha Dé Danaan occupied Ireland. The theme of the Children of Lir was jealousy. The mythical King Lir, lord of the sea, had been defeated by the Gaelic people. He and his wife Aoibh had four beautiful children, Fionnuala, Aodh (both of whom had gills and webbed feet), Fiachra and Conn. Their mother Aoibh died and Lir married her sister, Aoife, who possessed magical powers. Aoife at first loved her stepchildren, but because of Lir’s affection for them she became jealous and plotted their death. One day, on a visit to the new King Bodhbh, she flunked killing them but instead encouraged the children to swim in a lake that they were passing. Out came her magic wand and the children were turned into four beautiful swans (Figs 9 and 10), condemned to spend 300 years on Lough Derravaragh (Loch Dairbhreach), County Westmeath, 300 on the stormy sea of the Moyle between Ireland and Scotland (Sruth na Maoile), and 300 off the west coast of County Mayo (Iorras Domhnann), where they found a home on the island of Inishglora (Inis Gluaire). They spent much of their time on Loch na-nEan or Lake of the Birds, where they sang so sweetly that all the sea-fowl came to hear them, crowding onto the shore. Each day the swans set off from Inishglora to feed along the nearby coast and islands:

But the swans,

During the day would take their flight to seek

For food along the coasts, or wing their way

To Iniskea, where stands upon one leg

The lonely crane that never had a mate

But lives companionless, who never left.7

Their wicked stepmother had told them that the spell that had transformed them into swans would not be broken until they heard the bell of the new God (the conversion of Ireland to Christianity by St Patrick).

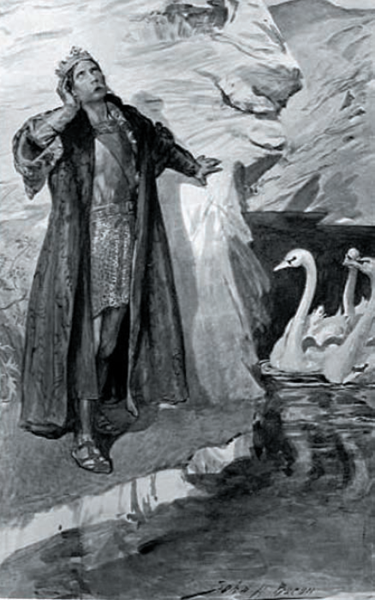

FIG 9. Children of Lir, by Maud Gonne.

From Ella Young, Celtic Wonder Tales (Dublin, 1910).

FIG 10. King Lir and the swans, by J. H. Bacon, ARA. From Charles Squire, Celtic Myths (London, 1912).

Whilst based on Inishglora they met St Mochaomhóg, a local ecclesiastic from the mainland who provided shelter for the swans in a small chapel that he had built, possibly the church at Cross Lough on the mainland opposite the island, and the swans attended his religious services. During the sixth century St Brendan the Navigator (d. 577) also established an ecclesiastical settlement on the island, consisting of a monastic cashel with a chapel, nunnery, monastery and other structures.

I know Inishglora well, having visited it many times. The monastic settlement remains, although in a dilapidated state, and there is indeed a small lake there that could have been the Lake of the Birds. Another candidate is Cross Lough on the mainland, which today is an important wildfowl wetland with many wintering whooper swans. On the island itself there are barnacle and greylag geese, but wild swans are unusual. However, I have seen whooper swans during spring migration in April flying low over the sea northwards, close to the island.

One day Lairgren, King of Connacht, arrived to gather up the swans and present them to his wife, who had heard that they sang beautifully and had expressed a wish to have them. As they were being loaded up into a cart the bell rang and a great mist descended, as it had done 900 years earlier when the children were transformed into swans. The mist then turned into the colours of the rainbow before being blown away. The swans had been magically transformed back into humans, but they were old and withered. Lairgren fled when he saw the human bodies, but Saint Mochaomhóg baptised the ageing children just before they died, and buried them on the island. The christening suggests some sort of Church approval of the myth.

The story of the Children of Lir is thought to have been based on a migratory legend known as ‘the Knight of the Swan’, which may have reached Ireland from Britain at the end of the Middle Ages,8 though Edward Armstrong is more specific, believing that it reached Ireland earlier, from the British Kingdom of Strathclyde in the eighth century. Whatever its origin, the belief that our souls reposed in wild swans was so strong that for many centuries wild swans were afforded special conservation status among hunters.

In the mid-1960s, just after the Irish Wildfowl Conservancy was established in Galway, Ireland, it was common for foreign shooters to visit Ireland, especially from Italy and France. On one occasion a car-boot-full of wild swans was found, shot by unknown perpetrators. The eminent Bill Finlay, Chairman of the IWC at the time and later Governor of the Bank of Ireland, stated that no Irishman could have been responsible because of their deep belief that human souls resided within swans. It was later discovered that it was indeed heathen hunters from the Continent who had done the massacre!

For centuries geese and swans have provided essential food (meat and eggs) for people living in the Arctic — the Inuit of Canada and Greenland, the Samoyedic people of western Siberia, and some Icelandic farmers. The easiest way to capture the birds was during the annual moult, when they shed their flight feathers and become flightless for a few weeks in late summer and early autumn. The moulting birds could then be rounded up and driven like sheep into holding pens with funnel entrances, constructed with stones or any other suitable materials that were available. The pens were placed on elevated sites on flat plains, where moulting birds misguidedly sought refuge.

Other pens were constructed on natural breakout points on the edges of lakes. Moulting geese seek immediate refuge in any lake or water body when disturbed by people, either on foot or on horseback. They could then be driven out of the often-shallow lake into the previously constructed pen, which would normally have a large-mouthed funnel opening to stream the geese into the catching pen. Once secure in the pens they were slaughtered in their thousands. Most of the geese were ‘cached’ — first plucked and cleaned, then placed in ‘pit fridges’ hacked out of the permafrost. The frozen geese thus provided a supply of food throughout the year. Some geese would be cut up into strips and air-dried or salted before storing. Thousands of Arctic-nesting geese were caught and killed this way each year. Whenever nests were found, eggs would also be taken. The mortality may have had a significant historical impact on the breeding populations, but today very few geese and swans are trapped for food.

Moulting geese and swans are still caught today on their Arctic breeding grounds, but almost solely for the purposes of scientific research, which involves marking the birds with large plastic leg-rings that can be read in the field when the birds are in their European or American wintering quarters. In addition, some are fitted with engraved neck-bands (Fig. 3), while others have lightweight satellite transmitters strapped onto them that allow satellite tracking. Visual monitoring of the birds carrying their engraved plastic rings or ‘licence plates’ over a period of years provides invaluable information about migration routes, longevity, mortality and the breeding performance of individual birds.

Shooting during the spring and autumn migration periods is today the main cause of mortality of Arctic breeding geese, followed by losses during migration. Much of the shooting occurs in Arctic areas, but significant numbers are shot, both legally and illegally, in Iceland during both spring and autumn. When the birds arrive in their wintering areas in Ireland and Britain they are subject to further shooting mortality, but on an increasingly controlled basis.

Moulting ducks and their flightless young were once caught in large numbers further south, particularly in northwest Europe and especially in the Netherlands and in Britain, by driving them into traps set on the margins of wetlands. The success of such trapping depended upon large wild breeding populations and extensive wetlands. When both declined as a result of drainage operations during the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries, duck trapping became an unprofitable activity, but an ingenious Dutch invention, the duck decoy, then came into its own. Duck decoys (from the Dutch eende-kooi, duck trap) were capable of catching considerable numbers of migrating and wintering birds during the autumn, winter and spring. Taking wildfowl in these decoys was one of the most sophisticated and effective ways of trapping and killing wildfowl.

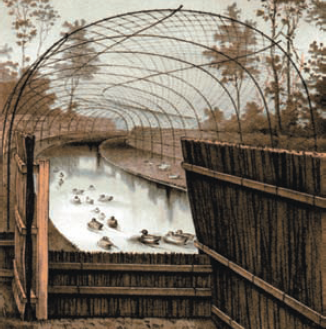

The basic duck decoy consisted of a pond or shallow lake of about one hectare, often set in woodland that provided a degree of security and cover for the visiting wildfowl. Radiating from the lake was a series of usually up to eight curved and covered tunnels, or pipes, up which the wildfowl were enticed until they reached the narrow tapering end, which terminated in a catching bag. The large number of pipes was necessary so that the decoy could operate in all different wind directions — wildfowl prefer to fly into the wind and often will move on the water surface facing into the wind. The netting- or wire-covered pipes could be up to 80 m long, 8 m wide at the entrance, with a height of 5 m above the water surface. Food was sometimes used to encourage the ducks into the mouth of a pipe. The sides of the pipes were blanked off, up to a height of about 2 m, or slightly higher than a person, with rush or reed screens that were set in such a way that they allowed the ducks to observe a specially trained dog that moved ahead of them. Ducks, like many other animals, have an innate mobbing behaviour and will follow and mob a predator. This alerts and secures the safety of the bird group by keeping a collective eye on the predator and making it harder for the predator to attack an individual in the group than if it were isolated. The dog — simulating a fox — ran ahead of the ducks, drawing them further and further up the pipe while the decoy man followed behind, initially keeping out of sight and then revealing himself to ‘push’ them on (Fig. 11). The ducks, when cut off from the pond by the decoy man, flew into the wind and up the pipe to be bagged at the end of the pipe. Successful decoying was a highly skilled art, requiring a special relationship between dog and decoy man. Call ducks, a type of miniature mallard with a distinctive call, were also used to decoy the wild birds into and up the pipes (see p. 32).

The Dutch, past masters in the art of trapping waterfowl, built hundreds of decoys during the sixteenth century. Many were highly profitable, often run by farmers in conjunction with other farming activities. But the English already had duck decoys in operation in the reign of King John (1199-1216). The earliest English decoy for which there are records was built at Waxham, Norfolk, in about 1620. By 1790 duck decoys were apparently supplying over 200,000 ducks for eating in London. However, many of the British — there were none in Scotland — and Irish decoys were non-commercial, existing to supply the ‘big house’ with an additional stream of fresh food. In 1886 Sir Ralph Payne-Gallwey was able to list some 200 British and Irish decoys in his magnificent Book of Duck Decoys (Fig. 12).9 Some 32 years later the number in use had declined to 19, according to the next major work on the subject.10 Running and maintenance expenses continued to spiral upwards, with declining numbers of ducks being caught. By 1936 only four British decoys remained open on a commercial basis.11 It was calculated then that a decoy needed to catch about 3,500 ducks per annum — mallard were the most frequently caught, followed by Eurasian wigeon and Eurasian teal — to remain economically viable, and the few remaining decoys could not produce those numbers. In their hey or duck days some Dutch decoys caught prodigious numbers — the decoy at Kampen, for example, caught more than 25,000 ducks in the year 1841. During the hundred years from 1809 over 650,000 were trapped and killed for eating at Kampen. During the late 1930s the annual catch from approximately 150 Dutch decoys was a million wildfowl. In contrast, some 11,500 wildfowl were caught per annum in the ten working British decoys between 1924 and 1935. Due to high maintenance and running costs most decoys have long since fallen into disuse, melting back into the landscape.

FIG 11. ‘Entrance to a decoy pipe with dog at work and wild fowl following him up the pipe.’ From Payne-Gallwey, The Book of Duck Decoys (Van Voorst, 1886).

FIG 12. ‘View of a decoy pipe as seen from the head shew place.’ From Payne-Gallwey, The Book of Duck Decoys (Van Voorst, 1886).

Some time before most duck decoys ceased commercial operations a pioneering Danish schoolmaster by the name of Christian Mortensen (also known as ‘Fugle-Mortensen’) was using decoys in Denmark to catch ducks for ringing, He was the first person to ring large numbers of birds. Working with the decoy on the island of Fanø he ringed large numbers of Eurasian teal and 320 northern pintail between 1908 and 1910. He was encouraged by the high rates of recovery, 20 per cent for northern pintail.

Today four British duck decoys remain open to the public, and they are certainly worth visiting. Borough Fen Decoy (1776), near Peakirk, Cambridgeshire, is the only remaining example of an old-style commercial decoy with eight pipes. Designated an Ancient Monument by the Department of the Environment in 1976, it has been managed under lease by the Wildfowl & Wetlands Trust since 1951 and it still operates to catch ducks for ringing. Over 41,000 ducks have been ringed there since 1947. Boarstall Decoy (existing before 1697), near Aylesbury, is owned by the National Trust and managed by the Berkshire, Buckinghamshire and Oxfordshire Wildlife Trust as a ringing demonstration station and museum. Today about 300 ducks, mostly Eurasian teal, are caught each winter. Abbotsbury Duck Decoy (built around 1655 — one of the oldest in Britain) is located within the Swannery at Abbotsbury in Dorset. Since 1976 it has caught over 1,400 duck for ringing, mostly Eurasian teal, with much smaller numbers of northern pintail. The Berkeley New Decoy was built in 1834 and renovated by the late Peter Scott when he established the Wildfowl Trust in 1946. It has four pipes, two at each end of the pool, and is set within the Wildfowl & Wetlands Trust grounds at Slimbridge. The decoy has caught over 27,000 duck, mostly mallard with some Eurasian teal, and a few northern shoveler and northern pintail.

Orielton Decoy (1868), near Pembroke, was the first British decoy employed for ringing ducks. Over 12,000 birds were ringed there between the decoy’s refurbishment in 1934 (at the instigation of Peter Scott) and when it ceased operations in 1960. The Wildfowl Trust formerly operated the Nacton Decoy (built 1830), Suffolk, from 1968 to 1982. During this period 15,631 birds were ringed, including large numbers of Eurasian wigeon, Eurasian teal and northern pintail. More than 50 per cent of all northern pintail ringed in Britain were caught at Nacton during its 14 years of operation. A few other decoys have been used for duck ringing, including Dersingham Decoy (built 1818 — now disused), Norfolk.

Payne-Gallwey, writing in The Fowler in Ireland (1882), could not understand why there were not more duck decoys in Ireland, especially as they were ‘a lucrative amusement’ in a country that was ‘so admirably adapted by nature where there is an abundance of wildfowl’. Only 22 Irish decoys were listed by Payne-Gallwey, all of which have now fallen into decay or totally disappeared.

The Fowler in Ireland listed only three decoys still in operation. The first was at Longueville, County Cork, originally constructed in 1750 with four pipes, later reduced to two, which were fed to attract the ducks. About 300 birds were caught annually, and the biggest catch was 730 — mostly mallard, Eurasian teal and Eurasian wigeon — during the winter 1845/46. The decoy ceased working when the estate was sold in the 1920s. It was the last decoy to operate in Ireland, and probably the longest in operation on a continuous basis, but with a break during World War I. The second was the decoy at Desart, County Kilkenny, which had been near to failure during the 1880s. The third was at Kellyville (now Kellavil), County Kildare, constructed around 1848 but not worked regularly until 1873. It had a total of nine pipes. Between 1,000 and 3,000 ducks — mostly Eurasian wigeon and Eurasian teal — were taken each year on this 5-hectare water. During 24 seasons from 1880 a total of 25,919 ducks were caught — nearly two-thirds Eurasian teal and one-third mallard, with Eurasian wigeon, northern shoveler and northern pintail making up most of the balance. When the estate was sold to the Irish Land Commission during the 1920s the decoy ceased. Following the fate of many another ‘big house’, Kellyville was demolished about 1950 and the lake drained.12

Abandoned decoys mentioned by Payne-Gallwey in The Fowler in Ireland and the Book of Duck Decoys were at Caledon, Co. Tyrone, where 200-400 wildfowl were taken each week; Coy Meadows, on the edge of Lough Beg, Co. Down; Eyre Court, Co. Galway, discontinued in 1860, which took similar numbers of wildfowl to Caledon; Clonfert, Co. Galway, discontinued from 1820; Markree Castle, Co. Sligo; Donerail Court, Co. Cork; Parteen, Co. Limerick; Mount Louise, Co. Monaghan; Mountainstown, Co. Meath; Lismullen, Co. Meath, discontinued about 1840; Lyons, Co. Kildare; Ballynakill, Co. Kildare; Kilcooley Abbey, Co. Tipperary; Anamoe, Co. Wicklow; Kellyville, Co. Kildare, discontinued in the 1920s; and long discontinued decoys at Glyde, Lisrenny, Beaulieu, Rathescar and Oriel, Co. Louth.

As soon as our ancestors had escaped from the hardships of a hunting and food-gathering culture and moved into an easier way of life as Neolithic farmers, they gathered animals around them and grew crops in nearby fields. The animals required a degree of domestication, a process that started some 10,000-12,000 years ago. While food production was the first priority, there were other benefits of the domestication process — production of hides, wool and other animal products, animals for protection and the management of farm stock, and the development of pets. The larger beasts such as sheep and goats were first favoured because of their obvious benefits (copious products in the form of meat, milk, wool, hides and fleeces), and they generally ate what people did not want. Dogs were among the earliest domesticated animals, bred to defend people and safeguard property and domestic animals. Most of our animal stock originated in the Middle East, with most domestication occurring in Asia. In contrast our crops arose generally from tropical America, China and southwest Asia.13

Wildfowl were lower down the scale of animal domestication priorities, but despite their smaller size they possessed many prized qualities — easy to manage, fast growers, tasty flesh, good egg production, abundant grease and oil (for lamps, preserving meat and ointment) as well as down feathers for bedding. They also provided quills for arrows and writing pens. Moreover, they were easy to subdue, required little or no maintenance and, like goats and sheep, did not compete for human food. Thus they converted unwanted vegetation into valuable protein, fat and feathers.

The general effects of domestication on wildfowl have been birds that mature more quickly, increased levels of polygamy, prolongation of the breeding season with production of more eggs, larger clutches, and larger bodies that in many cases are obese. Many domesticated breeds have lost the power of flight, and some have been developed for exhibition features such as crests and other feather patterns, body shapes, sizes and colouring. Some have knobs and wattles near their bills as well as dewlaps or gullets. Most of these structures are featherless, probably functioning as heat exchangers on the larger, heavier birds.

There are four wildfowl species that have lent themselves to successful domestication. Two are geese (the greylag Anser anser and the swan goose Anser cygnoides), and two are ducks (the mallard Anas platyrhynchos and the muscovy duck Cairina moschata). The Egyptian goose Alopochen aegyptiacus was once domesticated, in Egypt only, but ceased to be a farm animal when the Persians invaded the country in 525 BC.14 The mute swan and the greater Canada goose are often found in semi-domesticated situations.

The semi-domesticated mute swan was farmed for its meat and feathers. It was the cygnets, not the adults, that were eaten, as they were apparently much tastier than the adults. They were taken from their parents and kept in special enclosures, where they were fattened up on barley. They were then roasted for special occasions, such as at medieval feasts — often several hundred were consumed at such events.

The Canada goose was originally imported to Britain from North America for ornamental purposes, and to aggrandise country estates. They were valued for their visual impact rather than as a source of meat, eggs or feathers. However, as they multiplied and spread out over the wider countryside, they became the quarry of many wildfowlers.

Another species that is used for the benefit of humans, the common eider, is not exactly domesticated, but it is certainly farmed in a structured way for its down feathers. The effectiveness of down as insulation is legendary, but for incubating wildfowl in the Arctic and sub-Arctic it is an essential defence against the cold. The female plucks down from her own breast and uses it both to line the nest and to cover the eggs and retain the heat of the clutch while she is off feeding. The down also helps to retain the moisture of the eggs.

In Iceland, for more than a thousand years, eiders have been farmed for their down (Fig. 13). They nest in colonies, and the colony is protected by the farmer on whose land they happen to be. Flat stone ‘nesting boxes’ are provided, and the birds nest under the slabs, which offer some protection from the two most dangerous predators, the Arctic Fox and the introduced American mink. Sometimes small, brightly coloured flags are erected in the colony: these not only mark the location of the birds but may also give comfort to the eiders.

FIG 13. Collecting down from an eider nest. The normal clutch size of the eider is between four and six eggs but nests may contain as many as eight eggs, probably laid by two females. Duvets with eider down are superior to those filled with goose down because eider down interlocks with itself and does not move around, creating bare patches. Goose-down duvets have to be divided into compartments to prevent bare patches. (Bryan and Cherry Alexander/NHPA)

Common eiders often nest in gull colonies, deriving extra protection from the gulls — mammalian predators would seldom penetrate such tightly packed colonies. The flapping flags resemble the wings of the ever-active gulls, and perhaps reassure the eiders that they are ‘protected’, as well as fooling potential predators.

The farmer twice collects the down from the nests, first when the clutch is completed, whereupon the bird replaces the down immediately, and then again after the ducklings have left the nest. Some 350 Icelandic farms produce about 3,000 kg of down annually, which at 2001 prices was worth approximately ̗1.5 million, or ̗4,285 per farm.15

The greylag goose is one of the longest-domesticated birds, with a known history going back 5,000 years. Today almost all Irish and British farmyard geese are imports of foreign-bred varieties of the greylag, with a few from the swan goose. Our domestic greylag goose and all its varieties were bred from the eastern Anser a. rubrirostris rather than the western race Anser a. anser, as they have the eastern-race characteristics of a grey cast to the feathers and a pinkish bill and eye-ring.16

In the process of domestication greylag geese have become tame, accepting human company (aided by the imprinting process), are sexually mature earlier (also polygamous), produce more eggs (up to 300 per year, compared with a clutch of five to six eggs for wild birds), have became fatter and heavier (up to three times the weight of wild birds), often flightless, and certainly more sedentary. White plumage is a feature of domesticated geese, the whiteness probably genetically linked to the bird’s ability to put on weight faster than the normal grey-coloured form — it needs more food but converts it into meat faster. White forms do not start laying eggs as early as dark birds, and their breeding season is shorter. So breeders of domesticated geese (and indeed ducks, chickens and turkeys) have the choice of developing either birds that put on weight fast or birds that produce more eggs. To complicate matters further, the flavour of goose meat is affected by the speed of the bird’s growth. The grey varieties are slower-growing, but have the tastiest meat, and larger and fatter livers than the white varieties.

The British Waterfowl Association has produced standards for 16 different types of geese derived from the eastern greylag, and five from the swan goose.17 For the purposes of illustrating the range of domesticated geese, eight types bred from the eastern graylag,18 and two bred from the swan goose, are briefly described.

The Pilgrim is a small to medium-sized goose, weighing up to 8.2 kg (gander), sometimes called the West of England goose. Ganders are pure or creamy white with blue eyes; the goose is soft grey with a white head and neck, or grey speckled with white, with dark brown eyes. This is the only domestic breed of goose that is sexually dimorphic both as goslings and as adults. It originated in Britain but was first standardised in America. It is thought to have been taken by the Pilgrim Fathers to Massachusetts in the Mayflower in 1620, but was probably sourced in the Netherlands, where the pilgrims had fled from British persecution. The American Declaration of Independence was signed with a goose quill pen reputed to have come from a Pilgrim goose.19 The breed has become rare in Britain and scarce elsewhere in Europe.

The Roman is another smallish variety, 4.5-6.3 kg in weight, fitting well into the modern oven. It is the preferred goose for meat production under intensive conditions. Imported to Britain from Italy around 1903, it probably originated in Romania, though it is often believed to be a descendant of the white geese (kept in the Temple of Juno) that saved Rome from the Gauls in 390 BC when their cackling calls awakened the sleeping Roman garrison. In thanksgiving a golden goose was carried in procession to Rome each year while the local dogs were whipped for their silence. In North America there are crested forms known as the Crested goose.

The Buff is a heavier North American breed, greyish buff with the same pattern as the greylag but paler.Brecon Buffswere bred from pale-coloured greylags collected from Breconshire hill farms, and were recognised by the Poultry Club of Great Britain in 1934. They are the only domestic breed with pink feet, suggesting out-breeding with wild greylags or even pink-footed geese. This is one of the few breeds to have originated in Britain.

Embdengeese are enormous and glossy white, the ganders weighing 12.7-15.4 kg and the geese 10.9-12.7 kg. The American Embden is claimed to be the fastest-growing domestic bird, putting on 24 times its hatching weight (113 g) by the end of its fourth week, a faster weight increase than that shown by the domestic chicken. Popular and extensively reared for its meat, it originated in Prussia and was first brought to Britain early in the nineteenth century.

The Toulouse (Fig. 14) is another large goose, with large dewlaps and folds, kept both for its flesh and for egg production. It weighs 9.1-13.6 kg, and the adults are grey and brown. Originating in southwest France, it was first introduced into Britain about 1840, when it also travelled under the name of the Mediterranean or Marseilles goose. Their livers were formerly the source of pâté de foie gras in the Dordogne region, a task discharged today by the smaller palebrown Landes goose from Alsace.

FIG 14. Toulouse goose. From Ashton & Ashton, British Wildfowl Standards (Senecio Press, 1999).

Bantams are very small white geese, well sized for roasting in an ordinary-sized oven. The breed was first developed in the Netherlands before 1940 and later improved by further breeding in Britain.

The Sebastopol(Fig. 15) is one of the strangest of domestic geese. It is small, weighing 4.5-7.3 kg, and either white with bright blue eyes or buff with brown eyes, with orange bill and feet. Both sexes have long curling feathers on the back or wings, or all over the body, due to a genetic condition in which the feather shafts have split open and curled apart. Because of its weird, almost poodle-like appearance it is sometimes known as the Pantomimegoose. Developed for its long feathers, used in quilts and pillows, it originated in the Lower Danube and Black Sea region and is found in Hungary and the Balkans. It was imported into Britain as an ornamental goose after 1856.

FIG 15. Sebastopol goose. From Ashton & Ashton, British Wildfowl Standards (Senecio Press, 1999).

The Russiangoose is represented by several different breeds characterised by short necks, thick bills and aggressive behaviour. They were bred in Russia for fighting, especially in the goose pits of St Petersburg, where ganders were set upon each other until they beat their opponent to death or drew blood.20 Goose fighting was banned in the nineteenth century, and pure breeds such as the Tula(a cross between the European western greylags and eastern geese developed from the swan goose) and the Arsamashave since more or less disappeared.

The wild swan goose of Asia has given rise to two domestic breeds, the Chinese goose and the African goose. The domestication process started in China some 3,000 years ago and spread to India, Africa and Europe. Both forms are more tolerant of warm climates than the greylag — they are traditionally the farmyard geese of tropical countries. They are also present in Britain and Ireland, often crossed with greylag breeds to produce fertile hybrids. They will also cross with Branta geese, but the offspring are infertile. The domestic breeds are very different from the swan goose, with much elongated necks, and shorter and thicker bills with a large frontal lobe unknown in the wild form.

FIG 16. Chinese goose. From Ashton & Ashton, British Wildfowl Standards (Senecio Press, 1999).

The Chinese goose (Fig. 16) comes in two colour forms, brown/grey (with black head knob) and a less common white (with yellow head knob). Their necks are long, held almost vertically. They are prized for their meat and eggs (approximately 80 per year) and they make good watchdogs — they are the noisiest of all geese. They were first brought to Europe from China in the eighteenth century.

The African goose (Fig. 17) is much heavier (8.2-12.7 kg) with a large dewlap on the throat and a sagging abdomen, somewhat resembling the Toulouse goose. There are three colour forms — brown/grey, buff and white. Their origin is uncertain, but they arrived in Europe at least 200 years before the Chinese goose.21

FIG 17. African goose. From Ashton & Ashton, British Wildfowl Standards (Senecio Press, 1999).

Ducks have been domesticated for only about half as long as geese. The mallard was probably first domesticated by the Romans some 2,500 years ago, but it had been kept in captivity without full domestication for several centuries in Egypt, Greece, China and Southeast Asia. The mallard has given rise to more domesticated forms or mutant strains than any other duck or goose, with some 22 different breeds listed by the British Waterfowl Association. The drakes of all domestic ducks descended from the mallard have curly tails. There have been three lines of domestication — meat producers, egg layers and ornamental birds. Unlike our domesticated geese, many breeds have been ‘developed’ in Britain. Only a few examples of the better-known breeds of the three lines are mentioned below.

The Rouen (Fig. 18) is large and heavy (drakes up to 5.4 kg), developed in Normandy. The French Rouen resembles a larger and slightly lighter-coloured wild mallard but standing more erect. The English or dark Rouen has a more horizontal stance, with the females darker and redder. In common with other brown domesticated wildfowl they take much longer to mature for eating (about 5-6 months). The excellent flavour of its meat has made the Rouen one of the most prized and favoured ducks with chefs.

The Aylesburyis another large duck (drakes 4.5-5.4 kg), white, with a pink-white bill and bright orange feet. It was developed in Britain in the early eighteenth century. Most white ducks seen on farms are either Aylesburys or white Campbells — traditionally kept by the wife and kids for pin money. Described as ‘lazy eating machines that enjoy their pond’, they have a broad breast and are ideal for eating. It is increasingly uncommon to find pure stock, because of interbreeding with the Pekin duck (originally from China, imported to Britain around 1874), which is creamy white, but smaller, with an almost upright stance.

FIG 18. Rouen duck. From Ashton & Ashton, British Wildfowl Standards (Senecio Press, 1999).

The Khaki Campbell was first developed as a variety of the Campbell duck in Gloucestershire in 1901 by crossing an Indian Runner female, a wild mallard and a Rouen. The breed was formerly very popular as a farmyard duck, but is now less common. It is a great egg producer, some birds producing an egg a day for the entire year. There are also white Campbells, a sport from the khaki, but these lay fewer eggs (about 200 a year). Being white, it grows more quickly as a meat producer and its white flesh is popular.

FIG 19. Indian Runner duck. From Ashton & Ashton, British Wildfowl Standards (Senecio Press, 1999).

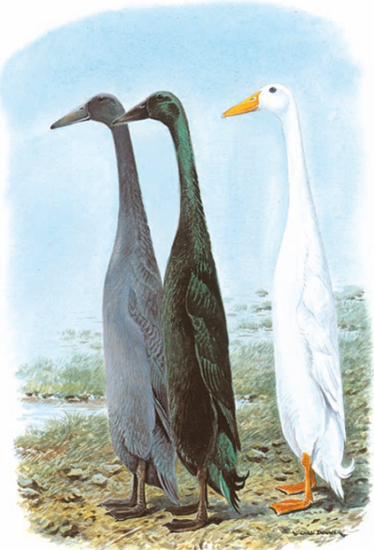

The Indian Runner (Fig. 19) has also been known as the Penguinduck, because of its very slim, almost upright, penguin-like stance. As the great French wildfowl expert Jean Delacour observed, its vertical posture is exaggerated to the point of ridicule. When standing bolt upright its length, from the tip of the bill to the tip of the middle toe, is 65-80 cm (drakes) and 60-70 cm (ducks). Selectively bred some 2,000 years ago in Asia — the Malayan archipelago, according to Charles Darwin — it was designed to forage for snails, insects and seeds in rice paddies, and it was daily walked in flocks to and from the fields, trained to follow coloured rags tied to poles. It was introduced to the Solway region, Scotland, from Indonesia around 1835. Its weird physique caught the eye of Charles Darwin, who pondered its origin. He concluded that its four curled central tail feathers showed that it was a mallard, selectively bred. Of all the ducks, only the mallard has these four feathers curled upwards.22 The Indian Runner is good for the table, although very slim, and a great egg layer, with some ducks laying upwards of 300 eggs a year. It comes in a variety of colours, including pure white, black, chocolate, blue, green, fawn, and fawn and white.

Call ducks are like miniature mallard, dwarf or bantam forms, and they come in many different plumages. It was originally called the coy or decoy duck, referring to its former use in duck decoys, where the wild duck were enticed to travel up the narrowing pipes by the high-pitched calls of call ducks placed close to the catching pens. Some call ducks have a plumage similar to mallard, while others are totally white or buff. They were probably imported from Asia, and were present in the Netherlands from the seventeenth century.

Muscovy duck

The final duck that succumbed to domestication was the muscovy duck, a perching species related to the mandarin. When the Spanish Conquistadors arrived in Peru and on the north coast of Colombia in the early sixteenth century they found muscovy ducks already domesticated by the native Americans. Muscovies also live in the Amazonian rainforests. The species was probably originally domesticated as a pet, but it also had value for eating the insects that abounded in houses. It was also eaten (the drakes reach up to 7 kg) and it was a good egg layer. They were brought back to Europe in the early 1550s and by 1670 had reached England,23 where, despite their tropical origin, they happily settled down in a colder climate The old drakes look ugly and unpleasant with large red facial warts (caruncles) and large wattles, together with a scruffy-looking plumage. After two or three generations of domestication they become heavier with even larger caruncles. They cross well with mallard, producing a sterile hybrid that grows fast and has good eating flesh. When crossed with a Rouen the result is a mule known as a mulard in France, where they are force-fed for their foie gras. Their breasts or magret (up to 400 g each) are also delicacies, smoked or dried.

There are many other varieties of domesticated geese and ducks in these islands, and there is a wide range of specialist organisations catering for these and other wildfowl interests. The principal organisations, listed below alphabetically, should be consulted for further information on the range of domesticated wildfowl:

British Call Duck Club (www.britishcallduckclub.org.uk)

British Waterfowl Association (www.waterfowl.org.uk)

Call Duck Association (UK) (www.callducks.net)

Domestic Waterfowl Club of Great Britain (www.domesticwaterfowl.co.uk)

Goose Club (www.gooseclub.org.uk)

Indian Runner Duck Association (www.runnerduck.net)

Poultry Club of Great Britain (www.poultryclub.org)

Scottish Waterfowl Club (www.scottishwaterfowlclub.co.uk)