Pressure on price leads many businesses into discounting. It is this practice which has the greatest negative impact on the profits achieved by the vast majority of business. Getting a grip on discounts could be critical to your own future success.

The key is that if your business gives discounts then this chapter could well be the most important in the whole book. Before getting into some of the reasons or remedies for this massive problem, it will be helpful to understand the financial dynamics.

Although it may well be impossible to eradicate discounting from your business, simply scoring the cost accurately, training your people to understand the implications, and putting in place basic disciplines to control it, will have a profound impact on your bottom line.

In this chapter you will learn:

- Who is affected by poor discounting practices.

- The financial dynamics of discounting.

- The impact of a small change in discounts.

- Discounting prices to win customers is a myth.

- Top four reasons why people discount.

- How to limit discounts.

Who is affected by poor discounting practices

Most businesses now operate in an environment where discounts are expected – even demanded – by customers, but some are more affected than others.

If you run a traditional business-to-business (B2B) operation then you will almost certainly discount your prices to some customers, at some time, and on some products. Many of you will have institutionalized discounting practices across all customers, all products and at all times.

You may be a retail business dealing with the end consumer and many of these businesses don’t have such a great problem. When we walk into a major retail store, such as a DIY warehouse, we see marked prices and mostly accept them as non-negotiable. Rarely do people get to the till and ask the cashier to knock a bit off. Certainly pubs, restaurants and such businesses rarely get challenges on their prices. It is simply a take-it-or-leave-it approach. But haggling even in these businesses is becoming more common, and especially in independent retailers where the customer feels that there may be some flexibility as prices have not been fixed by ‘head office’.

The financial dynamics of discounting

CASE STUDY

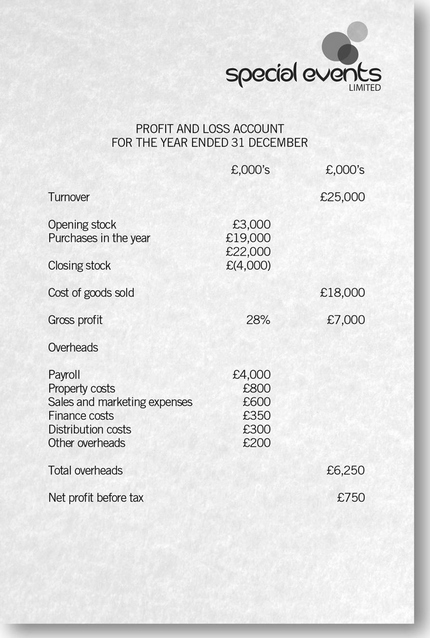

Special Events Limited (SE Limited) was a long-established large business, selling and hiring out specialist equipment to a mix of businesses and end consumers. Their turnover was £25m a year. Times had been getting tough in this very capital-intensive business, and they were not generating sufficient profit to continue investing in their future.

So, like many businesses they started a two-pronged attack through: a) marketing to win new business; and b) initiating a cost-cutting programme.

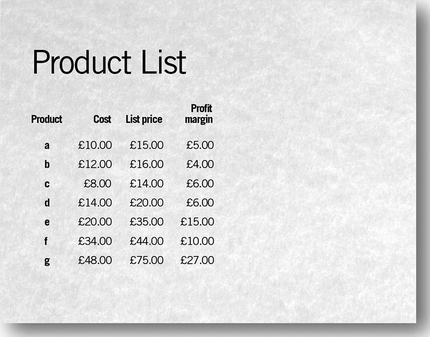

Broadly their numbers looked like Figure 10.1 on the following page.

The owner asked for external help with a cost-cutting programme, which of course always begins with examining the biggest costs.

Spending £18m on products to sell leaves some room for negotiation with suppliers, even with a good in-house buying team. Payroll is tougher, as cuts are hard to implement, and have an immediate cost of redundancy and negative impact on morale. Operating costs could be reduced by shopping around or cutting back, but on areas like sales and marketing this conflicts with the other objective of driving up sales. Many businesses can shave perhaps 10 per cent off their costs with a little effort, putting contracts out to tender, or gently haggling with existing suppliers.

Sadly, business owners and managers often miss one cost altogether, and it is a big one – one which most people don’t control. For SE Limited that could have been worth more than £5m a year.

A discount is the difference between the price that you hoped to get and the amount you actually achieve after you have been haggled down by arguments about how much they are spending with you and with the veiled threat to go elsewhere.

In SE Limited, they were able to accurately calculate the average discount given on all products for all customers at 21 per cent. This was no surprise to the CEO, and in fact he thought it might actually be even higher. But he still wasn’t quite sure how this debate related to a review of costs.

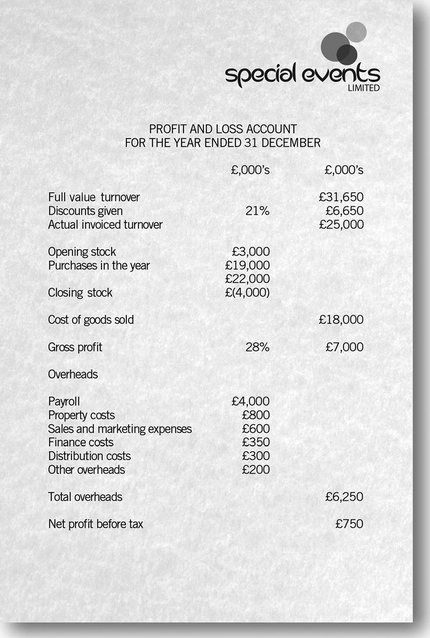

The impact of discounting can be illustrated by producing a new profit and loss account with some extra numbers:

FIGURE 10.2

If the turnover figure reported in the accounts was £25m – after an average 21 per cent discount – then the turnover before the discount would have been £31.65m and that meant discounts given away added up to £6.65m. Sadly, in almost all businesses, the money lost by uncontrolled discounting is not reported in the financial statement and nor in management accounts. The starting point for every sales transaction is the amount actually charged.

It may not be possible to wipe out this cost, in much the same way as it would be impossible to reduce payroll to zero. However, in the case of SE Limited, it is the second biggest cost after the cost of the goods bought for resale and way above the hard-to-reduce payroll bill.

The impact of a small change in discounts

Consider the impact of reducing this business cost by a small amount. If we aim to reduce the overall cost of the discounts given by say 5 per cent, this would in effect be a reduction of 1.05 per cent in the overall discount rate (5 per cent of 21 is 1.05), reducing it from 21 per cent to an overall average of 19.95 per cent.

First, what would this look like from the customer’s side of the deal?

- A customer who previously bought a £220 switching control box only paid £173.80 after 21 per cent discount; ie £46.20 profit was given away.

- If the business reduced the discount to the new 19.95 per cent level, the price paid would become £176.11, and the discount would reduce to £43.89.

- The customer therefore only pays an extra £2.31 above the old price of £173.80, equivalent to an overall price increase of just 1.3 per cent.

Now, would you expect any customers to walk away from something that is just £2.31–1.3 per cent – more expensive? Or based on a conversation that says, Sure we can give you a discount, it’s 19.95 per cent (rather than 21 per cent) off list price, if that’s OK? It is unlikely that this change would even be noticed by the majority of customers.

From the business’s side, what would be the impact if they cut back on discounts from the average of 21 per cent to 19.95 per cent (a 5 per cent drop) by being a little bit more sophisticated in their sales pitch, or just a little more disciplined in the way discounts are offered? What would it mean to the business overall?

- Getting the discount bill of £6,650,000 down by 5 per cent would release a staggering £332,500, which would filter down to net profit (as all other costs are unchanged).

- Profit was just £750,000, so this increases profits from £750,000 to £1,083,500 – a 44.3 per cent increase!

- In fact every 1 per cent drop in discounts is a £66,500 saving, equivalent to a price increase of 0.27 per cent (27p on a £100 item) but increases profits by 8.9 per cent.

This is easily achievable, and indeed the impact can be very much more. The effect on businesses is seeing their gross profit margins increase dramatically through simply managing discounts more actively.

You may be thinking that these numbers are simply irrelevant to your scale of business. Whatever the size of your operation, you will almost certainly find that discounts represents one of your top three business costs, up there with the cost of whatever you buy to sell and the payroll. Whatever the amount of money you give away, clearly some attention to it will help you reduce that cost. Every £1 you shave off discounts is £1 straight to your bottom line profit.

The critical starting point is to quantify it. This follows the maxim:

Discounting can be looked at from a slightly different perspective, which reinforces its importance.

Discounting prices to win customers is a myth

Many business people, and in particular those working on the frontline of sales, would argue that they need to give discounts or they will lose customers, or that they couldn’t win that new customer without the ability to discount the price. I would argue that better selling skills is the right answer, but let’s assume they are right. The question is of course, are they giving away more money in the value of discounts offered than they are getting back in increased profits from extra sales to existing customers, or in sales won from new customers?

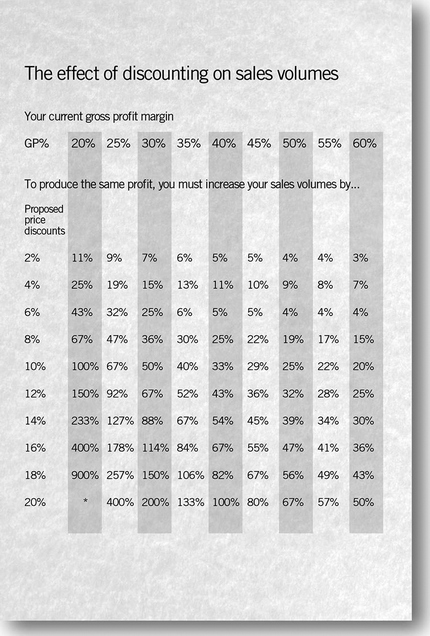

Figure 10.3 shows across the top various gross profit margins from 20 per cent to 60 per cent. Down the column on the left are proposed price discounts from 2 per cent to 20 per cent that could be used to try and increase sales. The results in the middle are the extra volume of sales that a business needs to achieve in order to replace the profit lost by dropping the price. Now this may be applied to your business as a whole, at whatever your average profit margin is, or you could do the exercise on a product-by-product basis. The calculations are exactly the same.

Simply find the column with the correct gross profit margin for your business or the product under review, and then look at the line across that represents the discount you are considering giving to boost the volume of sales.

For example:

The sales manager of a business that sells digital photo frames says: I want to drop our prices by 10 per cent so that I can increase our sales. The business currently buys the frames for £70, sells them for £100, and is therefore making a £30 or 30 per cent gross profit margin. They sell 1,000 frames a year at £100 each so have turnover of £100k, costs of £70k, and £30k or 30 per cent gross margin.

If they cut their prices by 10 per cent, and sell the next 1,000 for only £90 then the turnover reduces to £90k. However, the purchase cost of these 1,000 items remains the same at £70k and the gross profit therefore drops to only £20k. Unless volumes do increase they have just lost £10k.

At the new £90 selling price they now make only £20 profit after the £70 costs. So to recover the lost £10k of profit they need to sell 500 more units, just to get back to where they were.

If your margin was only 20 per cent and you discounted by 10 per cent to drum up new sales, then you would need to double your volumes to get back to where you started. The stark reality is that if you are discounting prices in the belief that it will stimulate additional volumes of business that more than make up for the lower profit margins, then quite simply you can’t.

There are only two valid reasons for discounting. First, where you are using it as a marketing tool to present the price in an attractive way, and have set your initial prices to be able to do this. (Re-read the section in Chapter 8 exploding the myth ‘A 50 per cent off sale is a 50 per cent off sale’.) Second, when your prices are wrong and need to be adjusted to the real market value. Before you use this reason you need to have done some serious market research to get your facts straight.

So why does everyone discount?

The top four reasons people discount

1 Because everyone else does it

Discounting in the business-to-business marketplace is following that of the retail marketplace. We have all become conditioned to the fact that when we walk into a supermarket or an electrical retailer, we will be greeted by signs offering:

- buy one, get one free;

- sale – 20 per cent off marked items;

- 50 per cent off selected end-of-season goods;

- spend over £50 and get an extra 10 per cent off these items.

There are many different permutations of these examples, but they all essentially offer a discount to customers. What that has done is to condition us to believe that there is opportunity to knock the price down a bit where we have been given a full or list price only.

Whatever the offer in the shop, we accept completely the new stated price. If the sign says that the price was £100, and is now £80 we accept this as being non-negotiable. However, if we were told by a business supplier that the price was £100, and we have discounted it to £80 many customers would still ask for a further discount. What this demonstrates is that the act of asking for discount is not actually a desire to try and get the Value Scales to balance because we genuinely value the item at less than the supplier has asked for.

It is not a real concern with the actual price, but just an automatically conditioned response to the price offered. When changes are made to teach frontline people how to politely say No when asked for a discount, the most common response from their customers has been Oh well, worth a try!

Inevitably, decades of price-driven marketing has meant that discounting has become a business way of life, and failure to offer one is seen like an attempt to overcharge or rip off the customer. Obviously if everyone does it, it is going to be hard for you in your business to stand alone and refuse to offer discounts. What we need to do is find a more subtle way of managing the problem. There are a good number of techniques later in the chapter.

One company really took the point, publishing a Discount Policy as part of its terms of trade. This notice was included with every quote and added to the footers of company emails.

DISCOUNT POLICY

As a company we work very hard to ensure that we can provide our customers with the highest quality goods, exceptional customer service, and at real value for money.

Our prices have all been determined after great consideration, at a level to enable us to achieve these things, and to make a fair profit.

Further discounts on our prices could only be achieved at the expense of reducing the quality of our products, or our standards of service, neither of which we are prepared to do.

So please do not ask for a discount, as the prices we offer are already the very best we can do.

They actually found they won business through this absolutely transparent pricing model, and certainly made a lot more profit by removing the random, uncontrolled discounting practices of their past.

2 Because they think it will increase sales volumes

We have commented already about the fallacy of this argument. Figure 10.3 showed for various gross profit margins, the additional business that is needed to replace the profit lost by a number of different price reductions.

The possibility of volume increases being sufficient to replace the profit given away is almost always nil.

It is important to explain, however, that seeking to increase volumes by dropping prices is a reason why many businesses do discount. This is as a result of not understanding the financial dynamics that are so visible in the earlier grids. They aren’t using carefully calculated figures, or basing decisions on detailed analysis of customer reaction. They just see all the big retailers running regular price offers, and think that these huge businesses must have done their homework and determined that discounting prices will generate extra sales and extra profits. What they fail to understand is that the retailers’ motivation to discount is for completely different reasons.

Look at a retailer selling a typical women’s jacket. They placed 1,000 units in the local outlet, selling at £49. At a cost of £29.40, they make 40 per cent (or £19.60) gross profit on each one. They sell 800 jackets at this price, over the first three months.

They are then faced with 200 items left to sell, and the new season’s lines coming in very soon. So they reduce the price by 20 per cent to £39. They now only make £9.60 on each item, roughly half the profit they did at the original price. This would not be an economic profit level on the whole 1,000 items of stock, but having already made a good profit on the 800 they sold, their motivation has now changed to one of clearing the shelves at the best deal they can, and not of generating overall profit.

Sales and profit results:

800 units × £19.60 profit margin = £15,680 profit.

So even if they throw away the remaining 200 items, they are still ahead:

200 units × £29.40 cost = £5,880 loss.

Profit on first 800 units |

£15,680 |

Loss on 200 thrown away |

£(5,880) |

Overall profit on all 1,000 units |

£9,800 |

If they can clear the last 200 units at their cost of £29.40, then the overall profit jumps back to £15,680. Anything above cost, then they are more than happy with the overall result. In fact, many big clothing retailers give end-of-line clothes to charities, or offer them at very low prices to staff. Some even destroy end-of-season stock to avoid undermining their original price position by being seen as a discounter.

You may think that this principle applies only to seasonal goods such as clothes, or perishable goods such as food, but it applies to anything the supplier wants to shift, whether that is to clear the shelves to make way for new stock, or just aid cashflow by getting rid of stock clogging up the warehouse.

The key point that needs to be understood is that the motivation of these big retail businesses is to clear the shelves, clear slow-moving items or to get rid of stock that will go out of date and be thrown away. They are not discounting their prices as a strategy to improve sales volumes.

Ouch!

These retailers have identified that their customers fall into a number of segments. Some are the early movers to whom they can sell the bulk of products at the highest prices. Then they will drop the price a little to sweep up the people that wanted the item but who weren’t prepared to pay full price; ie the price wary customers, and they then get rid of what’s left at little or no profit (but clear the shelves and avoid disposal costs) to the bargain hunters, or those whose decision is based on limited cash resources rather than any concern with the value for money.

What these retailers all know is that discounting prices does not simply generate increased sales, but it does moves the product value down to the next level of customer.

3 They made up the original price to make room for a discount

This issue is covered in depth in Chapter 8, so if you skipped that chapter go back and read it now.

There is nothing wrong with this approach. Manipulating prices to make consumers think that they are getting a great deal to capitalize on their natural desire to get a bargain is OK, providing you follow the legal rules. We would all like to think we had got something worth £1,000 for only £500, but the truth is that these are not real discounts.

The big downside of these practices is that it is conditioning consumers to believe that the profit margins businesses make are huge, based on the discounts they seem able to give. An ordinary local business that hasn’t artificially inflated the price to start with must therefore overcome the customer’s ignorance with better selling skills, or follow their example by inflating prices first. What you cannot do is give these high discounts unless they were built into your original price structure.

An accountant related this true story at a conference recently. A particularly difficult client was always arguing for a discount on the fees, to which the accountant had always steadfastly refused. Eventually he had enough and said:

Dave, every year we have this same argument about discounts. So this year I have added on £800 to my normal prices, and as a result I can afford to give you a 10 per cent discount which is equal to £800. Is that OK?

The client was delighted that the accountant had finally caved in, despite the complete transparency that it had been added on first. The point was that it was never dissatisfaction with the value of the fees, just a desire to feel he had had a good deal.

4 Salespeople rush for a quick sale

Earlier chapters examined all of the elements that form part of the whole package of why a customer chooses to buy. Price is only one of the issues that need to be explained and explored with potential customers.

The trouble is that most of the people that businesses employ to sell are simply not appropriately trained to do that role. Once again, a whole other book could look at selling skills, but having looked at many businesses it is fair to say that on the whole salespeople have received far less training and personal development support than that role deserves and needs. The skills of your salespeople become ever more critical to your success if you are to overcome the Discounting culture.

Let’s consider what a good salesperson should do; it will help us to see why there are so few. They should, for example:

√ Prepare for the sales pitch with research into the potential customer, such as who are the decision-makers, what their business needs are, etc.

√ Structure the call/sales pitch to ensure they get across the key points they want, and to uncover the needs/concerns of the customer.

√ Take appropriate support material such as demonstration items, sales literature, brochures, etc.

√ Be able to identify body language to know how to read a customer’s reactions.

√ Know when to go for the close. Too early or too late may miss the sale.

√ Be ready. A great salesperson can adapt to any situation and is ready to sell at the drop of a hat. They can hear a buying signal like a pin dropping, and have business cards in the pocket of their pyjamas!

When these great salespeople sell, they will explore with a customer their needs, listen very carefully to all the customer’s issues, and then explain how the features of the product or service they are selling will benefit the customer. They will cover issues such as when the item is needed, where it fits within the customer’s business, when it must be delivered, acceptable quality tolerances, colours, sizes, quantities, and find out who else is a potential supplier. Price is of course one element that needs to be addressed, along with payment terms and any possible volume discount.

In simple terms a key cause of discounts in business is the poor skills of the frontline salespeople to sell properly, leaving price as the only bit left to work with. If you employ salespeople, or are one yourself, just think through the last time they went on a sales training course, read a book on body language, etc.

There is often resistance to the idea of controlling the ability of salespeople to give discounts. Many argue that it is like asking them to work with one hand tied behind their backs. It is crucial therefore to get these people to understand the issue with some blunt examples of the impact of giving them free rein to drop prices.

This case study is about a small plumbing business with a turnover of £100k pa working for business customers and struggling with discounts.

Like many business owners Mr T was often in a position of having to give a discount to win the business (or at least he thought he had to). He was giving away almost £25k a year in discounts to be left with the £100k of turnover he actually billed. An external adviser convinced him to change his invoicing practices. In the past he would have agreed a sale of £125 and then a discount of £25 creating a net invoice of £100. This is the dialogue he tried:

I am sorry I can no longer give you a simple discount of 20 per cent, but I must invoice the £125 in full. However, as a valued customer I am still happy to do you a special deal, but I now have a ‘cash back’ policy if you pay promptly. I will give you £25 cash back so that you still in effect pay only £100. Sorry, but it’s a new system my accountant has put in place.

Let me be clear that there is no intention to avoid VAT, etc, but just to change the customer’s and the business’s appreciation of the transaction, although we did insist that the rebate was actually done in cash.

So what changes?

- First, the customer previously felt that the item was only worth £100. Whatever the headline price, in his mind the discount was his right, and the real value was only ever £100. By separating the £25 and saying it is because he is a valued customer rather than it being seen as a price correction, the likelihood is that they will now appreciate the full value at £125 and the bonus of a £25 discount.

- If the customer ever needs to go back and look up the invoice to check what they paid, the odds are they will only find the £125 invoice and not the £25 credit note that accompanies the cash back element. They may therefore accept £125 on a future purchase without seeing it as a price hike, as they will see the £25 cash back as more of a one-off transaction.

- Most people like to get a surprise or something for nothing, and the impact of the cash back is to make the customer smile with the apparent extra. The key is that happier customers are more loyal, spend more, and recommend you.

- The plumber only gives the rebate and credit note at the point that the full invoice is settled. If there is a dispute of any kind, he can chase for the full debt. This helps to underline the payment-terms element of the sale. That is, why should someone that has taken 90 days to pay still get a discounted price?

- The selling business also now views the discount in a different way. When parting with real money, there is a clearer assessment of those customers who actually deserve it rather than those who demand it. When you actually give cash to some of your customers you will make much harsher judgements of who you are happy to give it to!

Let’s be clear though: initially the plumber still only received the same £100 for the job. However, over time, this practice hardens his attitude towards who gets a discount and how much, and makes the customer far more appreciative of the amounts given. In many businesses this leads to significant reductions in the overall discounts given. Perhaps most importantly it enables the business to know how much discount they are giving away!

The logic of these points is simple common sense, although the practicalities of such an arrangement might bother you. It makes absolutely no difference to the turnover (£100 invoice, or £125 invoice with a £25 cash back), but it does affect both parties’ appreciation of the deal.

Look back for a moment at the SE Limited case study and relate this issue to their business.

If they were to invoice at full value, and then offer a cash rebate, this would be an average of 21 per cent of the normal price. To do this they would need to have cash (real money, £10 notes, £1 coins, etc) totalling £6,650,000 over the course of a year; or £25,000 each working day. Clearly, this is impractical. They would need to employ a guard, there would need to be strict access controls and managing authorized access would become necessary.

Now the Ouch!

Yet when you look at most businesses that simply give discounts by knocking it off of the full price, you find almost always that anyone can give any level of discount, to any customer and for any reason and usually at the simple press of a button!

If a business didn’t use cash back but allowed computer-generated discounts, then there is no lock on that door! The message to the sales force is help yourself!

Even in Mr T’s business, the average discount of 20 per cent equates to £25,000, so this is his second biggest cost and if actually delivered in cash rebates it would still merit a big padlock on his office door!

Most businesses have far stricter controls on the £100 they keep in the petty cash tin than they do on tens of thousands, hundreds of thousands and even millions that they allow people to give away through uncontrolled discounts.

Ouch!

There is one final point on discounts that is covered in greater detail in Chapter 14 Getting Financial Clarity, but is important to mention here. Fine Worldwide Goods Limited undertook a project to improve its profitability. One of the first steps was to produce a spreadsheet of every single product, showing cost, list price and hence the expected profit margin.

The list had almost 5,000 lines of stock and looked like this:

FIGURE 10.4

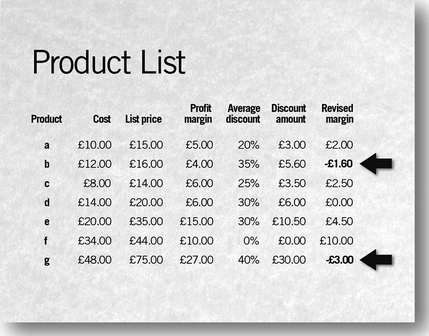

They then added a few more columns to show the average discount that had been given on those products to the various customers that bought them over the previous year. The list then looked like this:

FIGURE 10.5

Notice the lines where the business was giving an average discount that was higher than the profit margin – meaning that these items were being sold at a gross loss.

How did this happen?

Many of their larger customers were given blanket discount rates of 30 per cent, based on the high total sales with that customer. Overall, these customers bought loads of items, most of which had 50 per cent or 60 per cent margins, and an average of 30 per cent discount seemed OK in view of the sheer volume they bought. However, some of the products they bought only had profit margins of 20 per cent or even 10 per cent. So although they may have been a profitable account overall, they were generating a profit on some products but losses on others.

This wasn’t spotted because no one asked the right questions. You may think that this is a rare situation, but it happens in most businesses with a range of products or services.

Thousands of businesses ‘accidentally’ give customers more discount than the profit they make on certain individual products or services.

Ouch!

It is important to address the issue that discounting is a valid tool in the salesperson’s armoury.

In a perfect world a business would be able to charge a unique price to each individual customer based on all of the factors affecting them; ie their assessment of the value of the item, their ability to pay and perhaps the urgency to them. There may be 100 unique factors affecting each customer’s perception of their side of the Value Scales.

If I can charge customer A a maximum of £100 for a product, but customer B is happy to pay £150 for the same item, then I want to charge them each their respective maximum.

What stops us from doing that is a variety of factors including the complexity of having different prices for different customers, and perhaps our own moral judgement of fairness. We also fear being found out by customer B and having no apparent justification for the differential.

In many businesses we get around these issues by charging the same headline price to all customers but giving varying discount levels to achieve the same thing. There is nothing wrong with this at all. This is as close as most businesses can get to the profit-maximizing approach of charging each customer a unique price.

The problem with this situation is all the points covered above. That is, there is no structure to the process, no control over individuals giving the discounts and no scoring of the amounts to understand what this costs the business each year, on each product line or for each customer.

So don’t feel you have to abandon discounting as a tool to flex price properly for your different customers. It is a valid tool but it needs very careful management, and must be designed into your overall pricing strategy.

Businesses need to get much greater control over the issue. That means better systems and procedures, tighter rules and regulations, and discipline for the frontline people who actually give this money away. It is just too easy in most businesses to give discounts, and the pain associated with the press of a computer button or the stroke of a pen on the invoice simply doesn’t equate to the actual amount of pain that should be felt from the drop in profit that follows the drop in price. If we can get the people on the frontline of a business to agree with the simple logic of the need to control discounts when they are real cash amounts, as in the case study of Mr T the plumber, then it is very hard for them to ignore this logic when it is only a number on a page or computer screen.

Minimizing discounts is a critical area of pricing strategy.

You must quantify the discounts that you give away, and have good rules or systems to control them.

Changing the way you use discounts as a tool to flex price for different customers is a valid pricing strategy, providing it is properly controlled and understood by all salespeople and any others involved in the process.

1 Quantify the amount of discounts that you are currently giving. Get the finance team to determine the full list price value of all that you sell and compare this with the turnover that you actually achieve. Set up a system that scores this in as much detail as possible; ie certainly in total, but perhaps by salesperson, by branch, by product line, by customer, etc, if this is possible with your accounting software.

2 Set time-bound targets on how much you want this reduced by (globally or by the same subcategories as in 1) and equate this to the impact on profits of successfully achieving it; ie a drop in discounts of 5 per cent might be an increase in profits of 50 per cent.

3 Develop discount rules for your business. For example:

– Discount levels for various team members, such as counter staff only authorized to give discounts up to 10 per cent without manager approval, managers can go to 20 per cent without director’s approval, etc.

– Discounts not available where a customer account is outside of terms. That is, pay on time or pay more.

– Discounts must never be more than the profit margin being made.

– Discounts only with a minimum spend of say £100 or £1,000.

4 Once these rules have been approved by the CEO or finance team, have the pricing team design a roll-out plan so that the rules are communicated to the sales force, and in turn they communicate it to the customers.

5 Undertake discount-strategy training with all frontline people. Every one of those people must be able to explain the discount vs volume chart, and the other discounting issues covered. To demonstrate the magnitude of the discounting topic to your business, consider getting an average month’s discount in real hard cash and putting it on the table during training.

6 Make someone responsible for this cost, a Discount Controller. Get them to identify who gives the most away, what are the most common reasons for giving that discount, are some customers getting too much? Make it their job to manage the cost down. In most businesses someone newly recruited at a cost of £30k a year could easily pay for themselves by tackling the issue properly.

7 Involve your HR people and link salespeople’s performance-incentive pay to the gross margin achieved (after discounts) so they are driven to hold their nerve and limit the discounts they give.